Abstract

A 64-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for purpuric rash, joint pain, and a fever. He had earlier undergone a follow-up examination for interstitial lung disease. At the current visit, the diagnosis was immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, based on skin and renal biopsy findings. He developed sudden breathlessness and hemoptysis. Chest computed tomography revealed ground glass opacity in the right lower lung fields, suggesting pulmonary hemorrhaging associated with IgA vasculitis. Despite steroid and cyclophosphamide therapy, and plasma exchange, he died 52 days after admission. Early aggressive therapies may be recommended for old patients with IgA vasculitis who have an additional comorbidities.

Keywords: IgA vasculitis, pulmonary hemorrhaging

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis is an immune complex vasculitis affecting the small vessels. The chief clinical manifestations of IgA vasculitis include cutaneous purpura, arthralgia, enteritis, and glomerulonephritis (1). Pulmonary hemorrhaging is a rare complication of IgA vasculitis but is associated with high mortality and morbidity (2). The appropriate management of IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging remains controversial.

We herein report a case of IgA vasculitis complicated with pulmonary hemorrhaging that turned fatal despite the administration of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents and plasma exchange.

Case Report

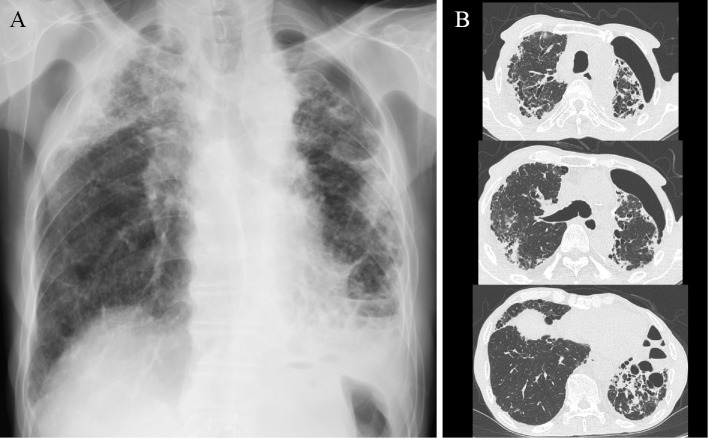

A 64-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for purpuric rash over his legs, joint pain, and a fever. He had undergone a follow-up examination earlier for interstitial lung disease along with surgery for left pneumothorax at our hospital. He had previously been engaged in sheet metal working and had never been in contact with birds or used down quilts. At the current admission, his temperature was 38.4℃ with extensive nonpalpable purpura over the legs (Fig. 1). He had clubbed fingers and a flattened chest. Coarse and fine crackles were heard in the bilateral lung fields on auscultation. Laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7.0×103/μL; hemoglobin level 11.5 g/dL; prothrombin time ratio 72.8%; fibrinogen-fibrin degradation products level 197.5 μg/mL; D-dimer 93.5 μg/mL; percentage factor XIII activity of 67.5%; serum urea level 17 mg/dL; creatinine level 0.86 mg/dL; C-reactive protein level 9.16 mg/dL; serum IgG 2,030 mg/dL; IgA 807 mg/dL; procalcitonin level 0.169 ng/mL; and β-D glucan level 6.0 pg/mL. Aspergillus antigen was positive, but aspergillus antibody was negative. Proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and myeloperoxidase-specific ANCA were negative. A urinalysis showed the absence of protein, 13.1 red blood cells per high-power field (HPF), and 1.1 WBCs per HPF. Chest radiography showed bilateral infiltrative shadows in the upper and middle lung fields and left lung collapse (Fig. 2A). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed reticular and infiltrative shadows in bilateral peripheral lung fields and collapse of the left lung (Fig. 2B). Significant pleural thickening with subpleural fibrosis was observed in the bilateral upper lung fields when compared to the lower lung fields.

Figure 1.

Purpuric rash seen on both legs.

Figure 2.

(A) Chest radiography on admission showed bilateral infiltrative shadows in the upper and middle lung fields and left lung collapse. (B) Chest computed tomography revealed reticular and infiltrative shadows in bilateral peripheral lung fields and left lung collapse. Pleural thickening with subpleural fibrosis was shown in the bilateral upper lung fields compared to lower lung fields.

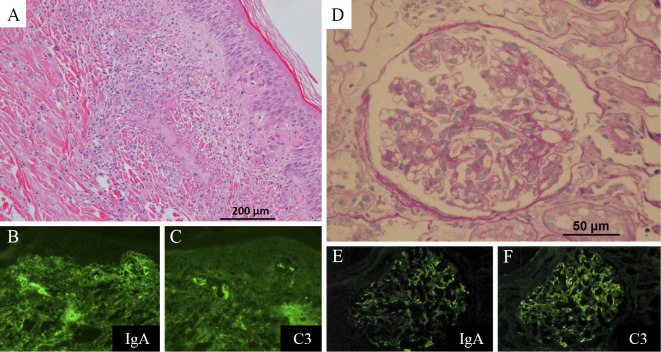

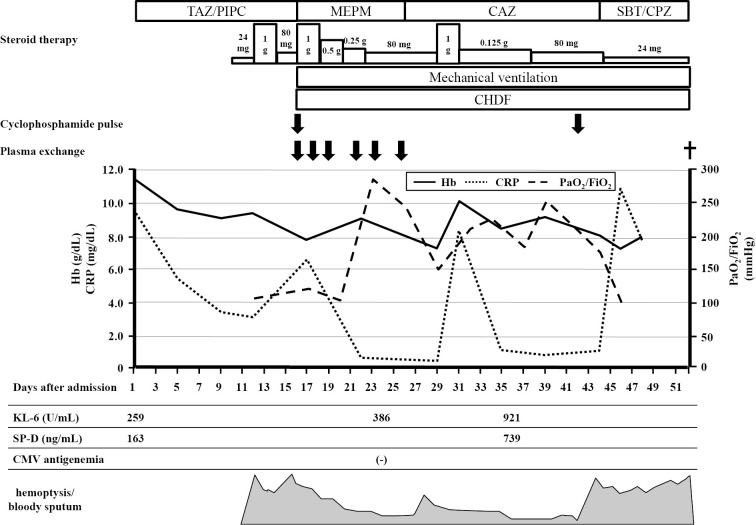

On suspicion of IgA vasculitis, skin and renal biopsies were performed. The skin biopsy specimen revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the small vessels throughout the dermis, with IgA and C3 deposition (Fig. 3A-C). The renal biopsy specimen showed evidence of endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis with IgA and C3 deposition (Fig. 3D-F). A diagnosis of IgA vasculitis was made. On day 10 of admission, he was administered 30 mg prednisolone per day, due to an increase in the serum creatinine level and occult blood in the urine. On day 12 of admission, he developed sudden breathlessness and hemoptysis. Chest CT revealed ground glass opacity in the right lower lung fields (Fig. 4). Sputum cultures were negative. Bronchoalveolar lavage was not performed because the patient's consent could not be obtained. However, the findings were consistent with pulmonary hemorrhaging associated with IgA vasculitis. He was administered pulse methylprednisolone at a dose of 1,000 mg/day for 3 days, which was then reduced to 80 mg/day. However, he developed hemoptysis once again, along with anuria. Artificial respiration and continuous renal replacement therapy were initiated, and plasma exchange and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy were administered. However, hemoptysis recurred again, and his respiratory condition deteriorated. The patient ultimately died 52 days after admission. The clinical course after admission is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 3.

(A) Histopathological findings of the skin specimen showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the small vessels throughout the dermis (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining). (B), (C) An immunofluorescence study showing perivascular deposits of immunoglobulin A (IgA) and C3. (D) A renal biopsy specimen showed endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis (PAS stain). (E), (F) An immunofluorescence study indicated mesangial IgA and C3 deposition.

Figure 4.

Chest computed tomography revealed ground glass opacity in the right lower lung fields on day 12 of admission.

Figure 5.

The clinical course after admission in the present case. Each dose of steroid therapy had equal amounts of methylprednisolone. TAZ/PIPC: Tazobactam/Piperacillin, MEPM: Meropenem, CAZ: Ceftazidime, SBT/CPZ: Sulbactam/Cefoperazone, CHDF: continuous hemodiafiltration, Hb: hemoglobin, CRP: C-reactive protein, PaO2/FiO2: partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/Fraction of inspired oxygen, SP-D: surfactant protein D, CMV: cytomegalovirus

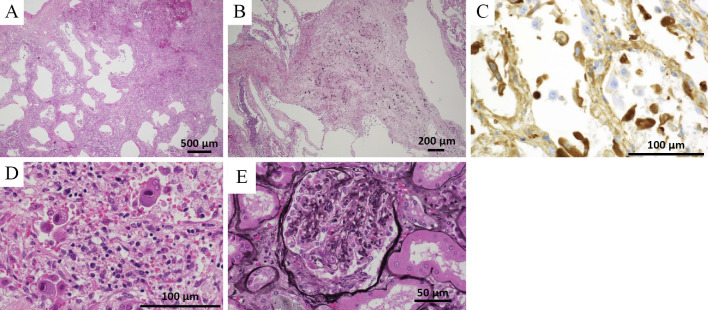

A postmortem macroscopic examination showed diffuse edema and alveolar hemorrhaging in both lungs. A microscopic examination showed erythrocyte extravasation and leukocyte infiltration in the interstitium of lung (Fig. 6A). Fibrous thickening and pneumoconiosis nodules were observed around the bronchioles of the bilateral upper lung lobes, suggesting pneumoconiosis (Fig. 6B). There were no findings suggesting bacterial or fungal infections. In addition, an immunohistochemical examination showed that IgA was positive in the alveolar walls (Fig. 6C). Cytomegalic inclusion bodies (owl's eye) were also seen in the lungs (Fig. 6D), kidneys and liver tissues, whereas cytomegalovirus antigenemia was not detected at 24 days after admission. There were crescent bodies in several glomeruli that had not been detected earlier (Fig. 6E). We concluded that the patient had died of pulmonary hemorrhaging associated with IgA vasculitis and cytomegalovirus infection.

Figure 6.

(A) The histopathological findings of the postmortem specimen showed erythrocyte extravasation and leukocyte infiltration in the interstitium of the lung (Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining). Leukocytoclastic vasculitis was not seen. (B) Fibrous thickening and pneumoconiosis nodules were seen around the bronchioles of the bilateral upper lungs (H&E staining). (C) An immunohistochemical examination showed that IgA was positive in the alveolar walls. (D) Cytomegalic inclusion bodies (owl’s eye) were also seen in the lung specimen (H&E staining). (E) There were crescent bodies in several glomeruli that had not been seen antemortem (PAM stain).

Discussion

IgA vasculitis is a vasculitis of small vessels, characterized by a purpuric rash, arthritis and abdominal pain. It is predominantly a disease of children aged 4-7 years (1). However, it can also appear in adults. The prognosis is generally good; nevertheless, complications can occur (1). The major complication of IgA vasculitis is renal involvement (1), while pulmonary hemorrhaging is a rare complication but is associated with high mortality and morbidity (2). It was reported that the incidence of pulmonary hemorrhaging due to IgA vasculitis is 1.6-5.0% (2-4). The present case was diagnosed as IgA vasculitis, based on the skin and renal biopsy findings. In addition, we concluded that the pulmonary hemorrhaging was associated with IgA vasculitis because the postmortem microscopic examination of the lungs by an immunohistochemical analysis revealed IgA in the alveolar walls, although leukocytoclastic vasculitis was not seen. A previous report mentioned that leukocytoclastic vasculitis on a lung biopsy might not be observed in all patients of IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging (2). In addition, an immunohistochemical examination showed that IgA was positive in 50% of IgA vasculitis patients with pulmonary hemorrhaging (2). Steroid and cyclophosphamide therapy might have altered the pathological findings.

There is no standard treatment for IgA vasculitis. Audemard-Verger et al. presented a treatment algorithm for the management of IgA vasculitis, based on the involvement of certain organs, such as the skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract and kidneys (1). This algorithm recommends steroids or/and immunosuppressive drugs for severe cases. However, it was reported that corticosteroids are ineffective for purpura of the skin, and no consensus has yet been reached regarding treatment for cases of renal involvement to prevent end-stage renal disease (1). Rajagopala et al. reported that most patients of IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging (22/36 patients) were receiving oral steroids for systemic vasculitis before the onset of pulmonary hemorrhaging, indicating that steroids alone are ineffective (2). Our patient also developed hemoptysis, despite steroid therapy. In addition, the efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine, cyclosporine A, cyclophosphamide and rituximab, is not well established because of the small sample size in studies that evaluated the efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs for IgA vasculitis (1,5,6). Our patient was also administered steroids and cyclophosphamide, but his respiratory condition did not improve. Augusto et al. reported that the combination of plasma exchange and corticoid therapy in severe forms of IgA vasculitis was associated with a fast improvement and good long-term outcome (7). We therefore also performed plasma exchange (six sessions in total) for our patient. However, there was no improvement in his respiratory condition, and he died 52 days after admission.

Old patients with IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging and existing comorbidities might have a high risk of mortality. Mortality was seen in 13 (28.9%) of the 45 cases of IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging reported thus far (including the present case) (Table 1, 2) (2-4,8-40). There were more patients with old age and an existing comorbidity in the non-survivor group than in the survivor group. Our patient was also old and had pneumoconiosis. There have been no reports of interstitial lung disease complicated IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging. In addition, we were unable to establish whether or not there was a causal relationship between IgA vasculitis and pneumoconiosis from the postmortem microscopic findings, but the comorbidity might have had an impact on his survival. A previous report of IgA vasculitis showed that symptomatic therapies are often administered as an initial treatment because the disease course is usually benign (1). However, it may be recommended for old IgA vasculitis patients with comorbidities to undergo early aggressive therapies. It was reported that the early administration of prednisone was useful in preventing the development of nephropathy in IgA vasculitis patients who had not yet developed signs of nephropathy (41).

Table 1.

Summary of Survivor Patients of IgA Vasculitis with Pulmonary Hemorrhage.

| Reference No. | Age | Sex | Comorbidity | Steroid | Immunosuppressive agents | Plasma exchange | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | 55 | M | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| (3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| (3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| (3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| (4) | 20 | M | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (4) | 76 | F | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (8) | 10 | F | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (9) | 17 | M | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (10) | 53 | F | (+) (DM) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (11) | 14 | F | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (11) | 4.5 | F | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (11) | 16 | M | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (12) | 14 | F | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (13) | 29 | M | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (14) | 14 | F | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (15) | 15 | M | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (16) | 12 | M | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (17) | 7 | M | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (18) | 6 | M | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (19) | 9 | F | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (20) | 45 | M | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (21) | 78 | F | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (22) | 6 | M | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (23) | 54 | M | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (24) | 33 | F | (+) (Kabuki synd.) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (25) | 72 | M | (+) (DM, HT, COPD) | (+) | (+) | (+) | ||||||

| (26) | 33 | M | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | ||||||

| (27) | 18 | M | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (28) | 10 | F | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (29) | 2.2 | M | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (30) | 11 | F | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) |

M: Male, F: Female, NA: not available, DM: diabetes mellitus, HT: hypertension, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 2.

Summary of Non-survivor Patients of IgA Vasculitis with Pulmonary Hemorrhage.

| Reference No. | Age | Sex | Comorbidity | Steroid | Immunosuppressive agents | Plasma exchange | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (11) | 15 | M | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (16) | 0.4 | F | NA | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (31) | 45 | F | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (32) | 8 | M | NA | (+) | (-) | (+) | ||||||

| (33) | 57 | M | NA | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (34) | 78 | M | NA | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (35) | 77 | M | (+) (Alcoholic liver injury, AP) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (36) | 13 | M | (+) (acute rheumatic fever) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (37) | 69 | M | (+) (renal insufficiency) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (38) | 74 | M | (+) (cerebral infarction, MPA) | (+) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| (39) | 73 | F | (+) (DM, Af, HT) | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| (40) | 8 | F | NA | (+) | (+) | (-) | ||||||

| Present case | 64 | M | ILD | (+) | (+) | (+) |

M: Male, F: Female, NA: not available, AP: angina pectoris, MPA: microscopic polyangiitis, DM: diabetes mellitus, Af: atrial fibrillation, HT: hypertension, ILD: interstitial lung disease

In the present case, a postmortem microscopic examination revealed a cytomegalovirus infection. This might have also affected the induction of hemoptysis, deterioration of the respiratory condition and the patient's death. Cytomegalovirus infection is reportedly one of the causes of diffuse alveolar hemorrhaging in immunocompromised patients (42). Therefore, when patients with IgA vasculitis undergo immunosuppressive therapies, the possibility of complication with cytomegalovirus infection should be considered.

In conclusion, this was a rare case of IgA vasculitis associated with pulmonary hemorrhaging. Additional research is necessary to develop a treatment algorithm for IgA vasculitis with pulmonary hemorrhaging.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Audemard-Verger A, Pillebout E, Guillevin L, Thervet E, Terrier B. IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Shönlein purpura) in adults: Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Autoimmun Rev 14: 579-585, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajagopala S, Shobha V, Devaraj U, D'Souza G, Garg I. Pulmonary hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: case report and systematic review of the English literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 42: 391-400, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cream JJ, Gumpel JM, Peachey RD. Schönlein-Henoch purpura in the adult. A study of 77 adults with anaphylactoid or Schönlein-Henoch purpura. Q J Med 39: 461-484, 1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadrous HF, Yu AC, Specks U, Ryu JH. Pulmonary involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Mayo Clin Proc 79: 1151-1157, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Autio-Harmainen H, et al. Cyclosporine A vs. methylprednisolone for Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: a randomized trial. Pediatr Nephrol 26: 2159-2166, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillebout E, Alberti C, Guillevin L, Ouslimani A, Thervet E; CESAR study group. . Addition of cyclophosphamide to steroids provides no benefit compared with steroids alone in treating adult patients with severe Henoch Schönlein Purpura. Kidney Int 78: 495-502, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augusto JF, Sayegh J, Delapierre L, et al. Addition of plasma exchange to glucocorticosteroids for the treatment of severe Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 663-669, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leatherman JW, Sibley RK, Davies SF. Diffuse intrapulmonary hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis unrelated to anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody. Am J Med 72: 401-410, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payton CD, Allison ME, Boulton-Jones JM. Henoch Schonlein purpura presenting with pulmonary haemorrhage. Scott Med J 32: 26-27, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shichiri M, Tsutsumi K, Yamamoto I, Ida T, Iwamoto H. Diffuse intrapulmonary hemorrhage and renal failure in adult Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am J Nephrol 7: 140-142, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson JC, Kelly KJ, Pan CG, Wortmann DW. Pulmonary disease with hemorrhage in Henoch-Schöenlein purpura. Pediatrics 89: 1177-1181, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright WK, Krous HF, Griswold WR, et al. Pulmonary vasculitis with hemorrhage in anaphylactoid purpura. Pediatr Pulmonol 17: 269-271, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallat BS, Teitel AD. Apurpuric henoch-schönlein vasculitis. J Clin Rheumatol 1: 347-349, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reznik VM, Griswold WR, Lemire JM, Mendoza SA. Pulmonary hemorrhage in children with glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol 9: 83-86, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter ER, Guevara JP, Moffitt DR. Pulmonary hemorrhage in an adolescent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. West J Med 164: 171-173, 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paller AS, Kelly K, Sethi R. Pulmonary hemorrhage: an often fatal complication of Henoch-Schoenlein purpura. Pediatr Dermatol 14: 299-302, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vats KR, Vats A, Kim Y, Dassenko D, Sinaiko AR. Henoch-Schönlein purpura and pulmonary hemorrhage: a report and literature review. Pediatr Nephrol 13: 530-534, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Besbas N, Duzova A, Topaloglu R, et al. Pulmonary haemorrhage in a 6-year-old boy with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Clin Rheumatol 20: 293-296, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Harbi NN. Henoch-Schönlein nephritis complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage but treated successfully. Pediatr Nephrol 17: 762-764, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teixeira A, Genereau T, Sutton L, Herson S, Cherin P. Implication of occult alveolar hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Clin Rheumatol 8: 287-288, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiryaki O, Buyukhatipoglu H, Karakok M, Usalan C. Successful treatment of a rare complication of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in advanced age: pulmonary hemorrhage. Intern Med 46: 905-907, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsubayashi R, Matsubayashi T, Fujita N, Yokota T, Ohro Y, Enoki H. Pulmonary hemorrhage associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a child. Clin Rheumatol 27: 803-805, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toussaint ND, Desmond M, Hill PA. A patient with Henoch-Schönlein purpura and intra-alveolar haemorrhage. NDT Plus 1: 167-170, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oto J, Mano A, Nakataki E, et al. An adult patient with Kabuki syndrome presenting with Henoch-Schönlein purpura complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage. J Anesth 22: 460-463, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goel SS, Langford CA. A 72-year-old man with a purpuric rash. Cleve Clin J Med 76: 353-360, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito Y, Arita M, Kumagai S, et al. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in IgA vasculitis with an atypical presentation. Intern Med 57: 81-84, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngobia A, Alsaied T, Unaka NI. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with hemoptysis: is it pneumonia or something else? Hosp Pediatr 4: 316-320, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James CA, Gonzalez I, Khandhar P, Freij BJ. Severe mitral regurgitation in a child with Henoch-Schönlein purpura and pulmonary hemorrhage. Glob Pediatr Health 4: 1-4, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aeschlimann FA, Yeung RSM, Laxer RM, et al. A toddler presenting with pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Nephrol Dial 7: 73-80, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren X, Zhang W, Dang W, et al. A case of anaphylactoid purpura nephritis accompanied by pulmonary hemorrhage and review of the literature. Exp Ther Med 5: 1385-1388, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacome AF. Pulmonary hemorrhage and death complicating anaphylactoid purpura. South Med J 60: 1003-1004, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss VF, Naidu S. Fatal pulmonary hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Cutis 23: 687-688, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kathuria S, Cheifec G. Fatal pulmonary Henöch-Schonlein syndrome. Chest 82: 654-656, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markus HS, Clark JV. Pulmonary haemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Thorax 44: 525-526, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yokose T, Aida J, Ito Y, Ogura M, Nakagawa S, Nagai T. A case of pulmonary hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura accompanied by polyarteritis nodosa in an elderly man. Respiration 60: 307-310, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalyoncu M, Cakir M, Erduran E, Okten A. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a case with atypical presentation. Rheumatol Int 26: 669-671, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Usui K, Ochiai T, Muto R, et al. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage as a fatal complication of Schönlein-Henoch purpura. J Dermatol 34: 705-708, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagasaka T, Miyamoto J, Ishibashi M, Chen KR. MPO-ANCA- and IgA-positive systemic vasculitis: a possibly overlapping syndrome of microscopic polyangiitis and Henoch-Schoenlein purpura. J Cutan Pathol 36: 871-877, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pourcelet A, Georgery M, Vandergheynst F, Hougardy JM, De Breucker S. An exceptional cause of hemoptysis in the elderly patient: IgA vasculitis. Acta Clin Belg 28: 1-2, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marandian MH, Ezzati M, Behvad A, Moazzami P, Rakhchan M. Pulmonary involvement in Schonlein-Henoch's purpura. Arch Fr Pediatr 39: 255-257, 1982(in French, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mollica F, Li Volti S, Garozzo R, Russo G. Effectiveness of early prednisone treatment in preventing the development of nephropathy in anaphylactoid purpura. Eur J Pediatr 151: 140-144, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Ranke FM, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, Marchiori E. Infectious diseases causing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in immunocompetent patients: a state-of-the-art review. Lung 191: 9-18, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]