ABSTRACT

Lens epithelial cells are bound to the lens extracellular matrix capsule, of which laminin is a major component. After cataract surgery, surviving lens epithelial cells are exposed to increased levels of fibronectin, and so we addressed whether fibronectin influences lens cell fate, using DCDML cells as a serum-free primary lens epithelial cell culture system. We found that culturing DCDMLs with plasma-derived fibronectin upregulated canonical TGFβ signaling relative to cells plated on laminin. Fibronectin-exposed cultures also showed increased TGFβ signaling-dependent differentiation into the two cell types responsible for posterior capsule opacification after cataract surgery, namely myofibroblasts and lens fiber cells. Increased TGFβ activity could be identified in the conditioned medium recovered from cells grown on fibronectin. Other experiments showed that plating DCDMLs on fibronectin overcomes the need for BMP in fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-induced lens fiber cell differentiation, a requirement that is restored when endogenous TGFβ signaling is inhibited. These results demonstrate how the TGFβ–fibronectin axis can profoundly affect lens cell fate. This axis represents a novel target for prevention of late-onset posterior capsule opacification, a common but currently intractable complication of cataract surgery.

KEY WORDS: Lens, TGFβ, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Fibrosis, Cataract

Highlighted Article: Wounding-related changes in the extracellular matrix induce abnormal TGFβ activation and differentiation of lens epithelial cells that could contribute to vision loss after cataract surgery.

INTRODUCTION

The lens consists of a monolayer of epithelial cells on its anterior face and the crystallin-rich lens fiber cells, both encased in the acellular lens capsule. After early embryogenesis, all subsequent growth of the lens results from differentiation of epithelial cells into so-called secondary fiber cells at the lens equator (Cvekl and Ashery-Padan, 2014). Formation of fibers in the normal lens is regulated by fibroblast growth factor (FGF), the levels of which are higher in the vitreous humor at the rear of the eye than in the anterior-facing aqueous humor (McAvoy and Chamberlain, 1989; Robinson, 2006; Zhao et al., 2008).

Growth factors also regulate lens cell fate in pathological conditions, notably posterior capsule opacification (PCO), the most common vision-disrupting complication of cataract surgery (Awasthi et al., 2009; Findl et al., 2010). PCO is caused by residual lens cells that remain in the lens capsule after cataract removal undergoing one of two cell fates. Some lens cells become fibrotic myofibroblasts, whereas others ectopically differentiate into immature (e.g. still nucleated) lens fiber cells, forming Elschnig pearls. When either abnormal cell type accumulates at the rear of the lens capsule, they interfere with transmission of light to the retina (Apple et al., 1992, 2000, 2011; Wormstone et al., 2009; Vasavada and Praveen, 2014).

It is known that TGFβ signaling is increased during cataract surgery, presumably as part of the wound-healing response (Sponer et al., 2005; Saika et al., 2002). It has long been proposed, and experimentally supported in primary culture systems, that TGFβ signaling contributes to myofibroblast differentiation in PCO, as it does in many fibrotic conditions in other organs (Meacock et al., 2000; Wormstone et al., 2002, 2006, 2009; Saika, 2004; de Iongh et al., 2005; Vasavada and Praveen, 2014; Nibourg et al., 2015; Boswell et al., 2017). We have recently shown that TGFβ induces some epithelial cells in primary embryonic chick lens cultures (DCDMLs) to differentiate into myofibroblasts, and other cells in the same wells to form immature lens fiber cells. The latter process is distinct from induction of fiber differentiation by FGF in that it does not require BMP signaling and is only partially reduced by fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibition (Boswell et al., 2017).

The lens capsule has been referred to as the thickest basement membrane in the body (Sueiras et al., 2015). Although many extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins have been identified in the lens capsule, two are of particular significance for lens cell fate: laminin, an abundant component of the normal lens capsule, and fibronectin (FN). There are two major structurally and functionally distinct classes of FN (To and Midwood, 2011). Plasma fibronectin (plasma FN) is produced by the liver, and is present in human plasma at a concentration of ∼300–400 µg/ml and in the plasma-derived aqueous humor at ∼64 ng/ml (Vesaluoma et al., 1998). Cellular fibronectin (cFN) is synthesized by many cell types and can be incorporated into insoluble fibrils in the ECM that play an essential role in tissue fibrosis induced by wounding and other insults (To and Midwood, 2011). Although cFN may initiate assembly of extracellular FN into fibrils, plasma FN is well-known to be able to be functionally incorporated into such matrices (Hayman and Ruoslahti, 1979; Oh et al., 1981; Peters et al., 1990; Mao and Schwarzbauer, 2005; Moretti et al., 2007).

Immunolocalization of FN in the normal adult vertebrate lens has generally been reported to be concentrated at the outer surface of the anterior lens capsule (Kohno et al., 1987; Duncan et al., 2000; Wederell and de Iongh, 2006). This distribution has been attributed to adsorption of plasma-derived FN in the aqueous humor onto the capsular surface and an inability of FN to pass through the intact capsule. In the context of cataract surgery, there are two sources of FN. The first is from plasma and arises from the fact that the operation both causes a transient breach of the blood–ocular barrier and creates a hole in the anterior of the lens capsule that gives plasma components direct access to residual lens epithelial cells within the remaining lens capsule (Shah and Spalton, 1994; Laurell et al., 1998). The second source is cFN produced and secreted by the lens cells themselves, and possibly also by giant cells (Saika et al., 1993). Although transcripts for cFN are detectable in normal lens epithelial cells from several species (Wolf et al., 2013; Chauss et al., 2014; Hoang et al., 2014), expression is strongly increased after surgical interventions (Medvedovic et al., 2006; Mamuya et al., 2014), including cataract surgery in humans (Saika et al., 1998a). This increase is thought to be linked to a rise in TGFβ signaling in response to wounding (Wormstone et al., 2009). Treatment of cultured lens cells with active, exogenous TGFβ dramatically increases the expression of cFN in several lens cell systems (Mansfield et al., 2004; Dawes et al., 2007; Boswell et al., 2017), including human lens capsular bags (Wormstone et al., 2002).

In some non-lenticular cell types, it has been shown that ECM can markedly affect growth factor signaling and its outcomes (e.g. Edderkaoui et al., 2007; Veevers-Lowe et al., 2011). We report here that physiologically relevant changes in ECM can profoundly affect lens cell fate in the absence or presence of exogenous TGFβ. These findings have therapeutic implications for the surgical treatment of cataracts, especially for the clinically important issue of delayed-onset PCO.

RESULTS

Plating lens epithelial cells on plasma-derived fibronectin upregulates canonical TGFβ signaling

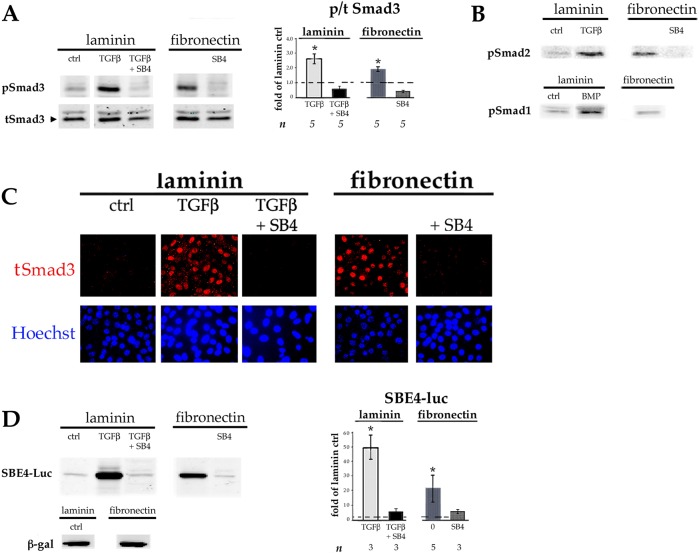

Primary monolayer cultures of embryonic chick lens epithelial cells (DCDMLs) are plated at subconfluent density on what is referred to as day 0 of culture in a serum-free minimal medium (M199/BOTS). Unless stated otherwise, medium is changed, and drugs added or cells transfected, on the following day (day 1), with medium changes every two days thereafter (Musil, 2012). We began this investigation by plating DCDMLs either on 33 µg/ml laminin (our standard preparation), or on bovine plasma-derived fibronectin (pdFN) at a concentration (12.5 µg/ml) that is ∼1/30 of that reported in plasma in order to conservatively approximate the levels of pdFN to which lens cells are transiently exposed when the blood–ocular barrier is disrupted during cataract surgery (Johnston et al., 1999). Lens epithelial cells adhered to, and grew on, laminin- or pdFN-coated plates equally well. Western blot analysis using antibodies against total or phosphorylated Smad3 (pSmad3) showed a 1.9±0.23-fold increase (mean±s.e.m.; n=5; P=0.001) in the activation of this key transducer of canonical TGFβ signaling in DCDMLs plated on pdFN, relative to laminin-plated cells when assessed on day 3 of culture. This increase was only modestly less than that obtained when cells plated on laminin were cultured in the continuous presence of 4 ng/ml of exogenous active TGFβ1 (Fig. 1A). Culturing pdFN-plated DCDMLs in the presence of SB431542, a highly selective small molecule inhibitor of the TGFβ-specific ALK5 receptor (Inman et al., 2002) (TGFβR1 hereafter) strongly reduced phosphorylation of Smad3, causally linking Smad3 activation to TGFβ signaling (Fig. 1A). Plating on pdFN also increased the levels of activated Smad2. These findings were specific to TGFβ signaling in that plating on pdFN did not induce activation of BMP-responsive Smad1 (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Lens epithelial cells plated on FN have higher levels of canonical TGFβ signaling than cells plated on laminin. DCDMLs were plated on day 0 of culture in tissue culture wells coated with either laminin or pdFN. On day 1 of culture, the culture medium was replaced with fresh M199/BOTS with or without 4 ng/ml TGFβ1, the TGFβR1 inhibitor SB431542 (SB4), or TGFβ1 plus SB431542 as indicated. Cells were analyzed on day 3 of culture. (A,B) Whole-cell lysates were prepared and probed with antibodies specific for total Smad3 (tSmad3) or the phosphorylated (activated) forms of Smad3, Smad2 or Smad1 (pSmad1, pSmad2 or pSmad3) as indicated. (C) Cells were fixed and immunostained for total Smad3 and nuclei counterstained with Hoechst 33258. (D) DCDMLs were transfected with plasmids encoding either the SBE4–luciferase (SBE4–Luc) reporter construct or β-galactosidase (β-gal) on day 1 of culture prior to cell lysis on day 3. Expression of pSmad3 (A) and luciferase (D) as assessed using western blot analysis was normalized to β-actin in the same sample, and plotted as fold-change of expression versus control (ctrl; defined as DCDMLs plated on laminin and cultured in unsupplemented M199/BOTS). *P≤0.02; other data sets not significantly different from ctrl. B and C are representative of ≥3 experiments.

Canonical TGFβ/Smad-mediated gene expression requires Smad2 or Smad3 to accumulate in the nucleus where they act as transcriptional cofactors (Massaous and Hata, 1997). We found markedly higher levels of Smad3 localized to the nucleus in DCDMLs plated on pdFN compared to on laminin on day 3. As expected, nuclear localization of Smad3 was abolished when cells were treated with SB431542 (Fig. 1C).

To directly assess the effect of pdFN on TGFβ-mediated gene expression, we transiently transfected DCDMLs with SBE4–luciferase, a well-established reporter of canonical Smad3-dependent transcription (Jonk et al., 1998; Piek et al., 2001; Boswell et al., 2017). When normalized to endogenous β-actin, we observed much higher levels of luciferase in pdFN-plated DCDMLs than in laminin-plated cells on day 3 (20.9±9.6 fold-change; n=5; P=0.01). This increase was abolished on treatment with SB431542 (n=3) (Fig. 1D). Upregulation of Smad3 signaling was also observed on day 1 after plating on pdFN (Fig. S1).

Fibronectin stimulates myofibroblast differentiation of lens epithelial cells

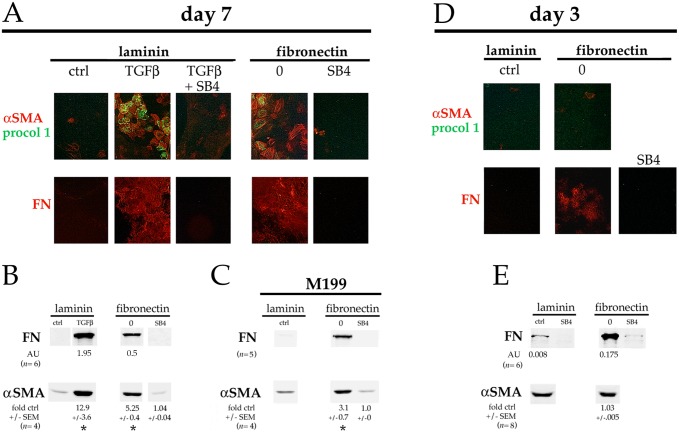

Adding 0.4–4 ng/ml exogenous (preactivated) TGFβ to subconfluent DCDMLs plated on laminin induces expression of established markers of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and/or epithelial–myofibroblast transition (EMyT) after a >3-day treatment (Boswell et al., 2010, 2017). Compared to cells plated on laminin at the same density, cells cultured on pdFN in the absence of exogenous TGFβ consistently showed a marked increase in staining on day 7 for procollagen 1 (also known as COL1A1), cFN, and α smooth muscle actin (αSMA); the latter in stress fibers characteristic of myofibroblast differentiation (Sandbo and Dulin, 2011) (Fig. 2A; n=4). Upregulation of αSMA and of FN in pdFN-plated cells was confirmed using quantitative western blotting (Fig. 2B). Expression of EMT and EMyT markers in pdFN-plated cells was blocked by the TGFβR1 inhibitor SB431542 (Fig. 2A,B). The fact that immunoreactive FN was undetectable when pdFN-plated cells were cultured with SB431542 confirmed that the anti-chicken FN monoclonal antibody employed in these experiments does not recognize the exogenous bovine pdFN upon which the cells were plated. As expected from its fibrillar staining pattern (Fig. 2A), ∼95% of the cFN produced by DCDMLs plated on pdFN was insoluble in sodium deoxycholate, a commonly used means to assess assembly of FN into a mature ECM (Wolanska and Morgan, 2015; Sechler et al., 1996) (Fig. S2). Enhanced expression of myofibroblast markers in pdFN-plated cells was also observed when DCDMLs were cultured in unsupplemented M199 instead of in our standard M199/BOTS medium, demonstrating that these findings were not dependent on a component of BOTS (2.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 25 µg/ml ovotransferrin, and 30 nM selenium) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Plating on FN induces expression of fibrotic markers. DCDMLs plated on either laminin or pdFN on day 0 were cultured from day 1 to day 7 (A–C) or from day 1 to day 3 (D,E) with or without 4 ng/ml TGFβ1 and/or SB431542 (SB4). (A,D) Cultures were immunostained for the mesenchymal proteins procollagen 1 (procol 1) and fibronectin (FN), or the myofibroblast marker α smooth muscle actin (αSMA). Near-confluent regions of cultures are shown. All markers assessed in a minimum of three independent experiments with similar results. (B,C,E) Cells were assayed for expression of FN or αSMA using quantitative western blot. Cells in C were cultured in M199 medium without BOTS supplementation. In E, the amount of cell lysate analyzed was tripled, and western blots probed for FN and αSMA were scanned at increased intensity. Data for αSMA (normalized to β-actin in the same samples) was quantitated as fold-change versus the values obtained with cells plated on laminin and cultured without TGFβ or SB4 (ctrl) in the same experiment. *P≤0.009; all other data sets not significantly different from ctrl. Where expression was high enough to be reproducibly quantitated, FN levels were expressed as arbitrary units (AU) obtained using infrared imaging, normalized to the value obtained in the same sample for β-actin.

By tripling the amount of cell lysate used for western blot analysis, we could detect very low levels of FN in laminin-plated DCDMLs cultured in the absence, but not in the presence, of SB431542 (Fig. 2E). By day 3, markedly higher levels of FN were recovered from cultures plated on pdFN as assessed using either western blot (Fig. 2E) or immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2D). This is at least two days before the appearance of appreciable numbers of myofibroblasts as defined by upregulation of αSMA.

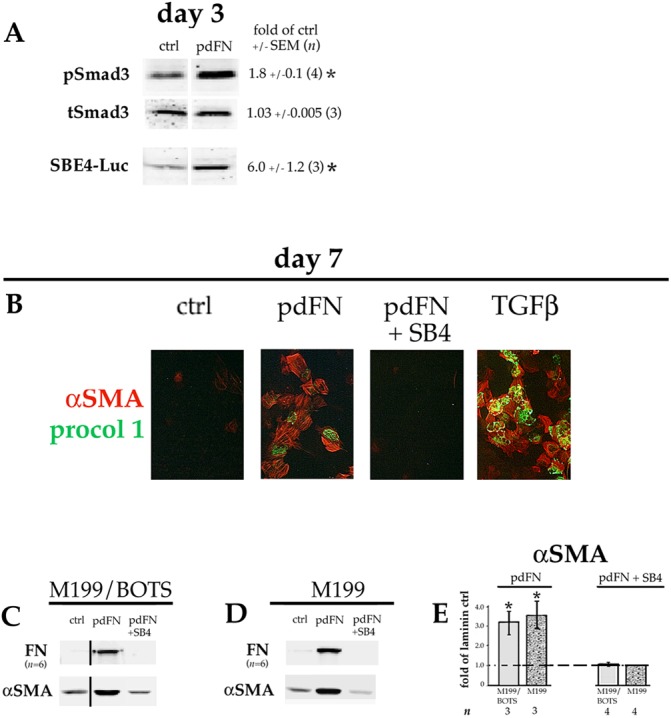

To more closely mimic post-cataract surgery conditions, DCDMLs plated on laminin on day 0 of culture were incubated in medium supplemented with 12.5 µg/ml pdFN starting on day 1. Cells exposed to pdFN in this manner showed increased levels of TGFβ signaling on day 3 as indicated by elevated levels of pSmad3 and SBE4–luciferase expression (Fig. 3A), albeit to a lesser extent than when cells were plated on pdFN (see Fig. 1). On day 7, EMyT was also markedly upregulated as assessed using both immunocytochemistry of αSMA and procollagen 1 (Fig. 3B), and western blotting of αSMA and FN (Fig. 3C). Qualitatively similar results were obtained when pdFN was added to unsupplemented M199 medium instead of to M199/BOTS (Fig. 3D). Under all conditions, upregulation of markers of EMT and/or EMyT was blocked through co-culture of cells with SB431542 (Fig. 3B–D).

Fig. 3.

Adding pdFN to the culture medium induces TGFβ signaling and EMyT in lens cells. DCDMLs were plated on laminin on day 0 and cultured from day 1 in M199/BOTS (A–C) or M199 (D) medium with or without (ctrl) 12.5 µg/ml pdFN, or with pdFN and SB431542 (pdFN+SB4) as indicated. (A) Cultures were analyzed on day 3 for pSmad3, total Smad3 (tSmad3), or SBE4–luciferase (SBE4–Luc) expression as in Fig. 1. (B) Cells were fixed on day 7 prior to immunostaining for αSMA and procollagen 1 as in Fig. 2. The (negative) control image from Fig. 2A was repeated in Fig. 3B because these data were from the same experiment. (C,D) Cells were assayed on day 7 for expression of fibronectin (FN) or α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) using western blot as in Fig. 2. All data shown are from the same blot at the same exposure. (E) Data for αSMA (normalized to β-actin in the same samples) in C,D was quantitated as fold-change versus the values obtained with cells plated on laminin and cultured without TGFβ or SB4 (ctrl) in the same experiment. *P≤0.02; all other data sets, not significantly different from control (P>0.2).

Fibronectin also stimulates lens fiber cell differentiation

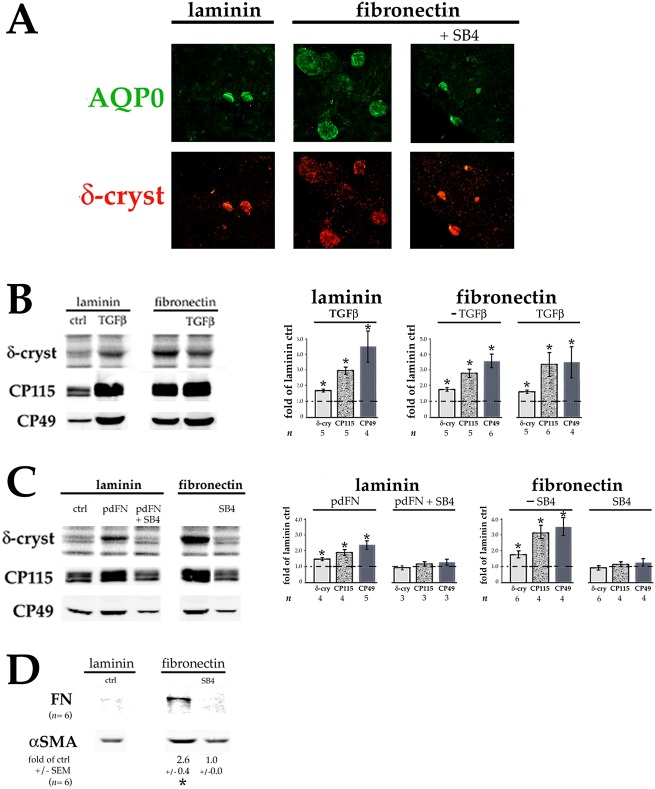

We noticed that on day 7 in more confluent regions of the cultures, cells plated on pdFN versus on laminin often had larger and/or more numerous lentoids, clusters of enlarged, fiber-like cells that resemble Elschnig pearls in PCO. To better study this phenomenon, we plated cells at 0.9×105 instead of 0.45×105 cells per 96-well plate well, a density at which they were ∼40% confluent. Immunocytochemistry confirmed that on day 7, lentoids in pdFN-plated cultures stained strongly for aquaporin-0 (AQP0), a protein specific to developing and mature lens fiber cells, as well as for the fiber-differentiation marker δ-crystallin (ASL1) (Fig. 4A). Culture of pdFN-plated cells in the presence of SB431542 reduced lentoid size and staining of aquaporin-0 and δ-crystallin to the level observed in untreated laminin-plated cells.

Fig. 4.

FN also induces lens fiber cell differentiation. DCDMLs were plated on laminin or pdFN at 0.9×105 cells/96 plate well on day 0 and cultured from day 1 in M199/BOTS (A,B,D) or M199 (C) medium with or without 4 ng/ml TGFβ1, 12.5 µg/ml pdFN, and/or SB431542 (SB4) as indicated. (A) On day 7 of culture, cells were fixed and double-immunostained for proteins specific to, or highly enriched in, differentiating lens fiber cells (aquaporin-0, AQP0; and δ-crystallin, respectively). Representative of ≥4 experiments. (B,C) On day 7 of culture, cells were assayed for synthesis of the fiber cell differentiation markers δ-crystallin (by [35S]-methionine labeling), CP115, and CP49 (by quantitative western blotting). The extent to which the treatment increased marker expression was calculated as fold-change versus the values obtained with cells plated on laminin and cultured with no additions (ctrl) in the same experiment. *P≤0.018; all other data sets, not significantly different than control (P>0.2). (D) Cells were assayed on day 7 for expression of the fibrotic markers FN and αSMA using quantitative western blot as in Fig. 2. *P=0.001.

Quantitation of δ-crystallin, and lens fiber-specific proteins CP115 (filensin, also known as BFSP1) and CP49 (phakinin, also known as BFSP2), confirmed an increase in expression in pdFN-plated cells on day 7, comparable to that obtained through culturing cells plated on laminin with 4 ng/ml TGFβ (Fig. 4B). Adding TGFβ to pdFN-plated cells only minimally further increased fiber cell marker expression, suggesting that near maximal levels of induction had already been achieved. Upregulation of fiber cell markers in pdFN-plated cells did not require the presence of BOTS supplement in the culture medium, and was enhanced in laminin-plated cells by addition of pdFN to the medium. SB431542 blocked this upregulation, demonstrating a dependence on TGFβ signaling (Fig. 4C). Time-course studies showed that levels of CP115 and CP49 are sharply increased relative to β-actin between day 3 and day 7 of culture in pdFN-plated cells (Fig. S3). Notably, expression of αSMA and FN on day 7 was also enhanced in cells plated on pdFN at 0.9×105 cells/well, albeit not to the same level as in more sparsely plated cells (Fig. 4D).

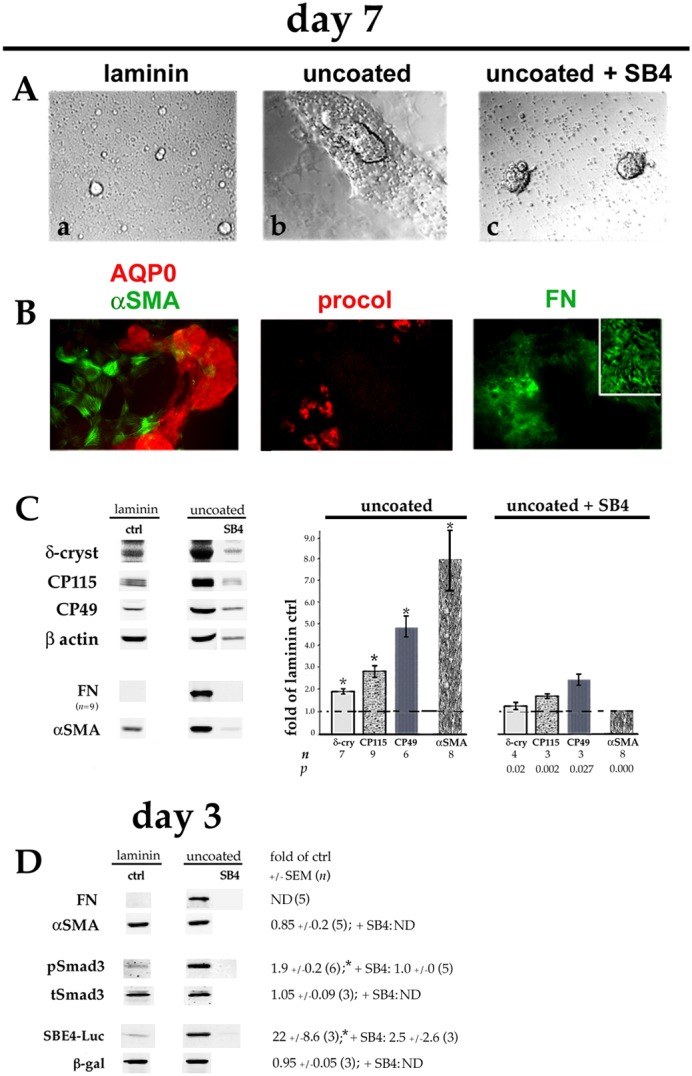

Plating lens epithelial cells on uncoated tissue culture plastic upregulates both myofibroblast and lens fiber cell differentiation

Next, we asked whether events observed after plating cells on pdFN could be achieved without adding either exogenous TGFβ or fibronectin. DCDMLs plated on uncoated tissue culture (TC) plastic take on the appearance of cells plated on laminin cultured in the presence of 4 ng/ml exogenous TGFβ, with massive phase-bright lentoids surrounded by very flat, non-cuboidal cells (Fig. 5A). Immunocytochemistry on day 7 confirmed that the lentoid structures expressed high levels of the lens fiber-cell protein aquaporin-0 and were adjacent to αSMA-, procollagen 1- and FN-positive myofibroblasts (Fig. 5B). Relative to cells plated on laminin at the same density (1.2×105 cells/well on 96-well plates), DCDMLs on uncoated TC plastic showed a large increase in expression of both fiber-cell (CP115, CP49, δ-crystallin) and EMT/EMyT (FN and αSMA) markers on day 7 (Fig. 5C). Upregulation of FN, but not of αSMA, was readily apparent on day 3 (Fig. 5D). This was associated with increased TGFβ signaling as assessed using pSmad3 immunoblotting and SBE4–luciferase expression (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Plating DCDMLs on uncoated tissue culture plastic upregulates EMyT, fiber cell differentiation and TGFβ signaling. DCDMLs were plated in uncoated tissue culture wells (or, as a control, in laminin-coated wells) at 1.2×105 cells/96 plate well on day 0. Cells were cultured from day 1 in M199/BOTS with or without SB431542 (SB4) as indicated. (A) Phase-contrast images of cultures on day 7; (a,b) show near-confluent regions, whereas (c) shows two balls of tightly packed cells surrounded by phase-bright cell blebs. (B) Cultures plated on uncoated plastic were immunostained for aquaporin-0 (AQP0) and the fibrotic markers αSMA, procollagen 1 (procol), and FN. Near-confluent regions of cultures are shown; inset is a high-magnification view of NaOH-insoluble FN extracellular fibrils. All markers assessed in a minimum of three independent experiments with similar results. (C) Cells were assayed on day 7 for expression of fiber cell and EMT/EMyT markers as in Fig. 4. Note that the lower number of adherent cells in cultures plated on uncoated TC plastic and treated with SB431542 resulted in lower levels of β-actin per sample. (D) Cultures were analyzed on day 3 for FN and αSMA, or for pSmad3, total Smad3 (tSmad3) and SBE4–luciferase (SBE4–Luc) expression using quantitative western blot as in Fig. 1. *P≤0.001 compared to untreated cells plated on laminin (ctrl); all other data sets not significantly different from control (P>0.2) unless indicated otherwise. ND, not determined.

Addition of SB431542 on day 1 to DCDMLs cultured on uncoated TC plastic strongly inhibited the expression of FN, αSMA, pSmad3 and SBE4–luciferase, and partially reduced the levels of lens fiber cell markers (Fig. 5C,D). Because fiber cell formation is promoted by cell–cell adhesion in a presumably TGFβ-independent manner (Okada et al., 1971; Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000), the incomplete block of fiber differentiation may be due to the very high level of cell–cell contact under these conditions (Fig. 5A, panel c), which is likely a result of reduced cell–substratum adhesion.

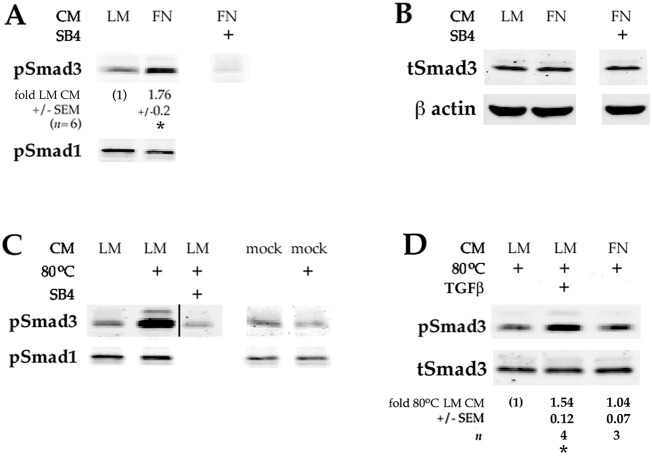

Effect of cell substrate on activation of endogenous TGFβ

One mechanism by which plating DCDMLs on FN could phenocopy the effects of adding exogenous TGFβ to laminin-plated cells would be by increasing the level of active TGFβ in the culture medium. To examine this possibility, we collected conditioned medium (CM) from DCDMLs plated on either laminin or pdFN for 48 h, and then used it to incubate for 1.5 h recipient lens cells plated on laminin. CM from cells plated on pdFN consistently showed a ∼1.8-fold greater ability to enhance Smad3 activation (pSmad3 levels) than CM from laminin-plated cells (Fig. 6A). In contrast, BMP signaling was not increased, as indicated by the level of pSmad1. As expected, upregulation of pSmad3 was blocked through pretreatment of recipient cells with SB431542.

Fig. 6.

Plating lens cells on pdFN increases their ability to activate endogenous TGFβ. Conditioned medium donor cells were plated on laminin (LM) or plasma-derived fibronectin (FN) on day 0. Medium was replaced with fresh M199/BOTS on day 1, and the conditioned medium (CM) collected on day 3. The CM was then added to recipient DCDMLs plated on laminin and incubated for 1.5 h prior to lysis of recipient cells and western blot analysis of active (phosphorylated) Smad3 and Smad1 (pSmad3/1), or total Smad3 (tSmad3). Where indicated (80°C), CM was heated to 80°C for 6 min to thermally activate endogenous latent TGFβ prior to addition to recipient cells. In some cases, recipient cells were pretreated with SB431542 for 1 h prior to addition of CM. (A) CM from pdFN-plated cells has a ∼1.8-fold greater ability to enhance activation of Smad3 than CM from laminin-plated cells. *P<0.000 compared to unheated CM from laminin-plated cells. (B) Total Smad3 levels did not change during the course of the experiment. (C) Heat treatment of CM from laminin-plated cells increased the level of pSmad3 in recipient cells by 3.88-fold (±0.7; n=4; P=0.004). Mock CM was generated using a 48 h incubation of M199/BOTS in pdFN-coated wells without cells. pSmad1 levels did not change during the course of the experiment. All data shown are from the same blot at the same exposure. (D) Heated CM was diluted tenfold with fresh M199/BOTS before addition to recipient cells. This ensured that the pSmad3 signal was not saturated and reflected the level of TGFβ signaling, as demonstrated by the 1.54-fold increase (±0.12; n=4; P=0.003) in pSmad3 levels when 4 ng/ml (active) TGFβ was added to heated CM. The difference between the Smad3-activating activity of heated CM from donor cells plated on laminin or pdFN was not significant (P=0.465). Total Smad3 levels did not change during the course of the experiment.

Native TGFβ is secreted in a latent form that must be activated to be able to signal through TGFβ receptors (ten Dijke and Arthur, 2007). Activation of secreted latent TGFβ can be experimentally achieved through heating cell-conditioned medium for 5–10 min at 80°C (Brown et al., 1990; Santiago-Josefat et al., 2004) (Fig. 6C). We collected CM from cells plated on laminin or pdFN. The total (i.e. detectable after heat treatment) Smad3-phosphorylating activity of both CM was similar (Fig. 6D). The increase in pSmad3-inducing activity in unheated medium from pdFN-plated cells (Fig. 6A) therefore appears to be due to an increase in the efficiency with which TGFβ was activated in these cells. CM from cells plated on uncoated TC plastic yielded results similar to those obtained with CM from pdFN-plated DCDMLs in the same experiment (Fig. S4).

TGFβ-activating integrins in DCDMLs

In mouse fibroblasts, activation of latent TGFβ requires matrix-bound FN, α5β1 integrin and αVβ6 integrin (Fontana et al., 2005). Other αV-containing, reportedly FN-binding, integrins have also been shown to participate in TGFβ activation in various cell types (Margadant and Sonnenberg, 2010; Horiguchi et al., 2012). As already noted, adhesion of DCDMLs to wells coated with pdFN is comparable with adhesion to laminin. Plating DCDMLs on pdFN increases autophosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) at Y397 within 45 min relative to cells in suspension or plated on poly-D-lysine (Fig. 7A). Both observations are indicative of basal expression of functional FN-binding integrins (Guan and Shalloway, 1992). Suitable activity-blocking antibodies specific to α5β1 or αV integrins are not available in chick, a recognized limitation of the avian system (Endo et al., 2013). We therefore tested for TGFβ-activating integrins in DCDMLs through: 1) examining the presence of α5 integrin on the cell surface and 2) assessing the effect of an αV integrin-selective peptide.

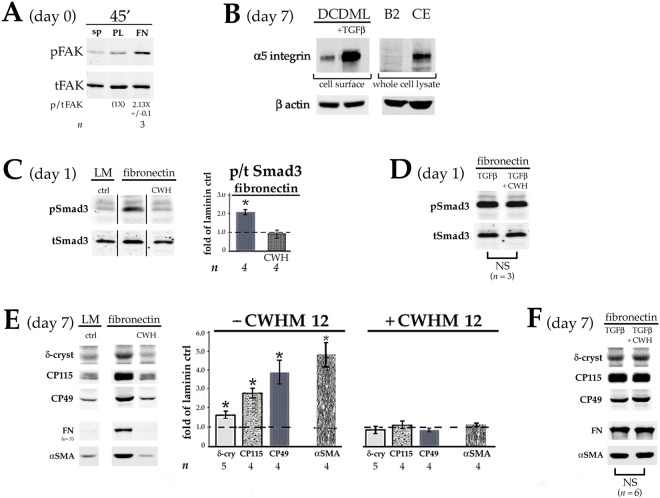

Fig. 7.

FN-binding, TGFβ-activating integrins in DCDMLs. (A) Freshly prepared lens epithelial cells were left in suspension (sp), or plated on tissue culture wells coated with either poly-D-lysine (PL) or pdFN (FN). After 45 min, cells were lysed and analyzed using quantitative western blot for total FAK (tFAK) and, in the same sample, FAK autophosphorylated at Y397 (pFAK). (B) DCDMLs plated on either laminin or pdFN were cultured with or without TGFβ. On day 7, the cultures were subjected to cell-surface biotinylation at 4°C and assessed for α5 integrin on the plasma membrane using western blot. Fold-increase in cell-surface α5 integrin (normalized to β-actin in the corresponding whole cell lysate) in TGFβ-treated cells was 6.75×±0.2 (n=3; P=0.001). Equal amounts of total cell lysate from α5 integrin-deficient CHO-B2 cells (B2) (Wu et al., 1993) and α5 integrin-rich HH stage 17 chick embryos (CE) (Muschler and Horowitz, 1991) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. (C) DCDMLs were plated on day 0 on either laminin (LM) or pdFN. After 4 h, the medium was replaced with fresh M199/BOTS with or without 100 µM CWHM12 peptide (CWH). Whole-cell lysates prepared 24 h after plating were analyzed using western blot for pSmad3 or total Smad3 (tSmad3). *P=0.004; other data set, not significantly different from control (P>0.43). All data shown are from the same blot at the same exposure. (D) As in C, except DCDMLs were additionally cultured with TGFβ in the presence or absence of CWHM12. NS, data sets not significantly different from each other (P=0.34). (E) DCDMLs were plated on laminin- or pdFN-coated wells at either 0.9×105 (δ-crystallin, CP49, CP115) or 0.5×105 (αSMA, FN) cells/well on 96-well plates on day 0. Cells were cultured from day 1 with or without 100 µM CWHM12 peptide as indicated. Cultures were assayed on day 7 for expression of fiber cell and EMT/EMyT markers as in Fig. 5. *P≤0.005; all other data sets, not significantly different from control (P>0.09). (F) As in E, except DCDMLs were additionally cultured with TGFβ in the presence or absence of CWHM12. NS, data sets not significantly different from each other (P=0.125).

In human and rodent cells, expression of the major FN receptor α5β1 integrin is low in the absence of TGFβ but is strongly upregulated in its presence (Wederell and de Iongh, 2006; Dawes et al., 2007). Strong focal adhesion immunostaining of α5 integrin in DCDMLs is also only detectable after treatment with TGFβ (Boswell et al., 2017). To assess whether lower levels of α5β1 integrin are present on the plasma membrane even without addition of TGFβ, we used the more sensitive technique of cell-surface biotinylation. As expected (Boswell et al., 2017), a strong α5β1 integrin band was observed on analysis of TGFβ-treated DCDMLs. A fainter, but distinct and specific band was also detected in cells cultured without added TGFβ (Fig. 7B).

CWHM12 is an RGD peptidomimetic antagonist selective for αV integrins, with no activity against RGD-binding (and FN-binding) αIIbβ3 integrin (Henderson et al., 2013). CWHM12 has been used to block αV-dependent processes both in vivo and in vitro, including activation of latent TGFβ (Henderson et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2017). Whereas DCDMLs plated on pdFN showed ∼2-fold higher levels of Smad3 activation on day 1 relative to cells plated on laminin, addition of CWHM12 to pdFN-plated cells abolished this increase (Fig. 7C). Importantly, CWHM12 did not reduce pSmad3 levels in cells coincubated with exogenous (active) TGFβ, indicating that the peptide acted by blocking conversion of endogenous latent TGFβ to an active form (Fig. 7D).

Plating DCDMLs on pdFN increases TGFβ signaling >4 days before upregulation of EMyT and fiber cell differentiation. If activation of endogenous TGFβ is required for differentiation of cells plated on pdFN, then CWHM12 would be expected to block both myofibroblast and lens fiber cell formation in DCDMLs. This was the result obtained (Fig. 7E). As for Smad3 activation (Fig. 7C), both myofibroblast and lens fiber differentiation were rescued when cells were co-cultured with CWHM12 in the presence of exogenous TGFβ (Fig. 7F). Taken together, these experiments support the contention that activation of TGFβ signaling (and subsequent lens cell differentiation) in pdFN-plated DCDMLs is mediated by integrins (see Discussion).

Plating lens cells on fibronectin overcomes the requirement for BMP in FGF-induced fiber cell differentiation

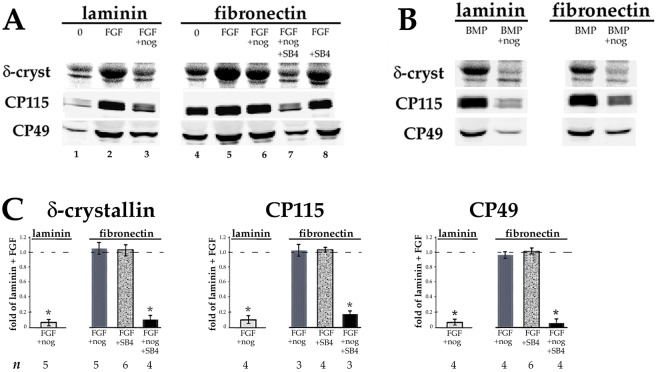

In normal lens development, fiber differentiation requires FGF, not TGFβ (Beebe et al., 2004; Robinson, 2006; Zhao et al., 2008). We have shown that upregulation of fiber differentiation by FGF in DCDMLs grown on laminin is dependent on signaling through endogenously produced BMP such that blocking the latter with the BMP2/4/7-specific inhibitor noggin prevents FGF from upregulating fiber formation when assessed on day 7 (Boswell et al., 2008) (Fig. 8A; compare lanes 2 and 3). Addition of exogenous BMP4 to DCDMLs also stimulates fiber marker expression in a manner blocked by noggin (Fig. 8B) and independent of FGF signaling. We found that cells plated on pdFN upregulated fiber cell marker expression on day 7 when treated with either FGF2 (Fig. 8A, lane 5) or BMP4 (Fig. 8B). As in laminin-plated cells, noggin abolished the effect of BMP4 (Fig. 8B). Noggin did not, however, block fiber differentiation in pdFN-plated cells in response to FGF (Fig. 8A, compare lanes 5 and 6), in marked contrast to cells plated on laminin (Fig. 8A, lanes 2 and 3).

Fig. 8.

Plating DCDMLs on FN renders FGF-induced fiber cell differentiation insensitive to noggin, and sensitivity is restored when TGFβ signaling is inhibited. DCDMLs were plated on laminin or pdFN on day 0 and cultured from day 1 to day 7 in M199/BOTS with no additions (0), 10 ng/ml FGF2 (A), or 10 ng/ml BMP4 (B), in the presence or absence of the BMP2/4/7 blocker noggin or SB431542 as indicated. Cells were assayed for synthesis of fiber cell differentiation markers as in Fig. 4. (C) The extent to which the treatments in A reduced fiber marker expression was calculated as fold-change versus the values obtained from cells plated on laminin and cultured with FGF in the same experiment. *P≤0.001; all other data sets, P>0.08. Not shown: When plated on either laminin or pdFN, noggin blocked fiber marker expression in response to BMP4 by ≥95% (n=3).

We next asked whether the higher levels of TGFβ signaling in cells plated on pdFN versus on laminin could account for this difference in behavior. pdFN-plated cells cultured with SB431542 continued to upregulate fiber cell marker expression in response to FGF (Fig. 8A, lane 8), to the level observed in cells plated on laminin (Fig. 8A, lane 2). The presence of SB431542 did, however, prevent upregulation of fiber differentiation markers in DCDMLs cultured with FGF plus noggin (Fig. 8A, lane 7). We conclude that enhanced TGFβ signaling in pdFN-plated cells confers the ability to upregulate fiber formation in response to FGF even in the absence of BMP signaling (results quantitated in Fig. 8C).

DISCUSSION

We have used a well-documented purified primary lens epithelial cell system to study the effect of ECM on growth factor-dependent cell fate. Specifically, we show that changing the substrate from one characteristic of the healthy lens (laminin) to one in which fibronectin is upregulated by cataract surgery-induced ocular wounding markedly affects lens cell differentiation in either the absence or presence of exogenous growth factors.

How does plating on fibronectin or on uncoated tissue culture plastic upregulate TGFβ signaling?

Lens epithelial cells from multiple species constitutively express TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3, as well as low levels of FN and several FN-binding integrins, including α5β1 and the αV subunit and many of its heterodimerization partners (Wolf et al., 2013; Chauss et al., 2014; Hoang et al., 2014). We propose that exposing DCDMLs to plasma-derived FN (consisting mostly of plasma FN, but also some cFN) (To and Midwood, 2011) allows the exogenous FN to become incorporated into insoluble, mechanically resistant extracellular fibrils (Dallas et al., 2005). It has long been appreciated that such fibrils contain cFN but can also incorporate plasma FN, the latter of which can account for up to 50% of their total protein content in vivo (Oh et al., 1981; Peters et al., 1990; Moretti et al., 2007). One mechanism consistent with our results is that this FN, in conjunction with FN-binding α5β1 integrin and one or more CWHM12-sensitive αV integrins, acts to induce conformation changes in the TGFβ–LTBP complex that result in growth factor activation (Fontana et al., 2005; Annes et al., 2004; Margadant and Sonnenberg, 2010). Alternatively or in addition, increased formation of FN fibrils could elevate the amount of latent TGFβ tethered into the ECM (Dallas et al., 2005), creating a depot of growth factor from which it could be activated by integrin-dependent and/or integrin-independent processes (Wipff and Hinz, 2008). Engagement of mature TGFβ with TGFβ receptors then leads to an upregulation in expression of FN, αV integrin, α5 integrin and TGFβ, all reported transcriptional targets of TGFβ in lens cells (Dawes et al., 2007). This in turn results in further activation of TGFβ. Such a feed-forward loop has been proposed in other cell types (Fontana et al., 2005; Margadant and Sonnenberg, 2010) and could serve to amplify and/or prolong TGFβ signaling. This process may be abetted by increased expression (Wang et al., 1999) and/or activation (Galliher and Schiemann, 2006) of TGFβ receptors by FN-binding integrins. The important role of FN in activation of TGFβ has been supported by the results of both in vitro (Fontana et al., 2005) and in vivo (Muro et al., 2008) studies in non-lens systems.

Unlike immortalized lens cell lines, primary lens cells are able to adhere and spread on uncoated TC plastic (or glass) in the absence of serum. Such behavior of primary cells has been attributed to the rapid extracellular deposition of cFN (Grinnell and Feld, 1979). We were able to detect cFN in extracellular fibrils within 48 h of plating DCDMLs on uncoated TC plastic (not shown), 3 days prior to appreciable upregulation of expression of procollagen 1 and αSMA. We propose that cFN endogenously synthesized by DCDMLs plated on uncoated plastic promotes activation of TGFβ in a manner analogous to plating cells on pdFN. This process may be aided by the ability of FN deposited on uncoated TC plastic to undergo a conformational change in the RGD region that mediates the binding of FN to TGFβ-activating integrins (García et al., 1999; Miller and Boettiger, 2003).

The most direct evidence that plating lens cells on FN or on uncoated TC plastic increases the level of biologically active TGFβ is the finding that conditioned medium from cells plated this way elevates the level of pSmad3 in recipient cells when compared to recipient cells treated with conditioned medium from cells plated on laminin. At least initially, this increase is likely to be the result of enhanced activation of latent TGFβ given that plating on pdFN or on uncoated TC plastic increases the ratio of active to total (i.e. latent+active) pools of TGFβ recoverable from the medium within 48 h (day 1–day 3; Fig. 6).

Taliana et al. (2006) developed a model for PCO in which cells in central epithelial explants prepared from rat lens migrated off the lens capsule onto TC plastic coated with either laminin or pdFN. They reported that cells that migrated onto pdFN had a more fibroblastic cell morphology and increased levels of pSmad2 and/or Smad3 in the nucleus when compared to cells migrated onto laminin. The relationship between these events and TGFβ signaling was not established; indeed, the authors concluded from negative results with a TGFβ-neutralizing antibody of proven potency that this effect was independent of TGFβ. In our system, it is clear that exposure to FN results in higher levels of active TGFβ in the culture medium and that increased EMyT in FN-exposed cells requires TGFβR1 activity. The current study is also the first to show that FN can promote lens fiber cell differentiation. The latter is especially significant given that formation of abnormal lens fiber cells has been described as the main cause of clinically important (e.g. vision-impairing) PCO (Apple et al., 2000; Findl et al., 2010).

Implications for PCO

In the past ∼20 years, the incidence of development of PCO within 1–2 years of cataract surgery has greatly declined, due in large part to the use of intraocular lenses (IOLs) with square edges that physically block the movement of lens cells to the posterior capsule. It has, however, become increasingly apparent that in many cases, this barrier is overcome ≥2 years after surgery. Such delayed-onset PCO has been estimated to affect 20–40% of cataract patients and is a significant burden to healthcare systems worldwide (Dewey, 2006; Awasthi et al., 2009). Determining the mechanistic basis for this condition and developing strategies to prevent it are major unmet goals. Saika and coworkers reported the presence of lens cells positive for nuclear Smad3 and/or Smad4 (Saika et al., 2002) or for TGFβ (Saika et al., 2000) in the capsular bags of patients for 8–9 years after cataract surgery. How TGFβ signaling can persist for so long after the operation-induced wound has healed has been a mystery. The aforementioned study showed nuclear Smad3-positive cells in areas of the lens capsule with elevated levels of extracellular matrix deposition (Saika et al., 2002). Although the composition of this matrix was not examined, others have reported lens cells in post-operative capsular bags embedded in FN, likely produced at least in part by the lens cells themselves in response to wounding (Linnola et al., 2000). cFN has been found associated with the lens capsule (Saika et al., 2000) and with explanted human IOLs (Saika et al., 1998b) 7–8 years after cataract surgery. We propose that this FN acts to upregulate activation of TGFβ, analogous to how FN enhances TGFβ activation and signaling in DCDMLs. The resulting increase in expression of TGFβ target genes (including FN, FN-binding integrins and TGFβ) leads to enhanced extracellular deposition of FN and other TGFβ-induced ECM components (e.g. collagen I) involved in tissue fibrosis. Consequently, more TGFβ becomes activated. Such feed-forward loops have been proposed to contribute to chronic fibrotic conditions throughout the body (Kim et al., 2017) and have previously been proposed for fibrotic PCO (Danysh and Duncan, 2009; Walker and Menko, 2009). Because FN also upregulates lens fiber cell differentiation in DCDMLs (Fig. 5), this process might also contribute to the formation of Elschnig pearls several years after cataract surgery. Interestingly, peptides capable of blocking FN matrix assembly in vivo have been described and used to prevent excessive ECM deposition in arteries (Chiang et al., 2009). Based on our findings, we predict that such an intervention might also be effective against late-onset PCO.

Duncan and coworkers (Mamuya et al., 2014) have used a mouse model system for lens wounding in which the fiber cell mass is physically removed via a hole made in the anterior of the lens capsule. Within 48 h after this procedure, TGFβ signaling is elevated in the remaining lens epithelial cells, some of which appear to have undergone EMyT. In wild-type mice, these events persist for the longest time examined (5 days). Lens-specific deletion of the FN-binding, TGFβ-activating αV integrin blocked both TGFβ signaling and myofibroblast formation after fiber cell removal, demonstrating its essential role in fibrosis. In a preliminary report (Shihan et al., 2017), the same authors reported that conditional deletion of cFN from lens epithelial cells had no effect on normal lens development. Although TGFβ signaling and myofibroblast differentiation were increased 48 h after fiber cell removal in such conditional knockout FN animals, neither was elevated on postoperative day 5. These results are consistent with our proposed model that production of FN by lens cells is required for persistent TGFβ signaling and its downstream consequences.

Effect of FN on FGF-induced fiber cell differentiation

Our findings also indicate that FN-induced elevation of TGFβ signaling can affect how cells respond to FGF, the major inducer of lens fiber formation during normal lens development. In laminin-plated cells (in which endogenous TGFβ signaling is low), FGFR activity is dependent on BMP signaling, whereas in pdFN-plated cells, TGFβ signaling may be sufficient for FGFR activity. Based on our previous studies (Boswell et al., 2008), one possible explanation for these findings is that TGFβ, like BMP, can act on FGFR activity (Shirakihara et al., 2011). It is also possible that TGFβ signaling can bypass the need for BMP signaling downstream of FGFRs. Facilitation of FGFR signaling by TGFβ has been reported in cranial suture development (Opperman et al., 2006).

What could the clinical significance of this phenomenon be? There is ongoing interest in treating cataracts not with implantation of an IOL, but through regeneration of lens fiber cells after removal of the affected fiber cell mass (Call et al., 2004; Gwon, 2006; Lin et al., 2016). One notable difference between lens regeneration and normal lens development is the abundance of FN in the former process arising from both disruption of the blood–ocular barrier and a wounding-induced increase in cFN synthesis (cFN appears to be the major ECM component rapidly upregulated in lens epithelial cells after fiber cell removal in mice; Medvedovic et al., 2006). Exposure to FN could alter the signaling mechanisms by which FGF promotes fiber mass regeneration, analogous to how plating cells on pdFN changes the role of BMP signaling in FGF-induced fiber differentiation in DCDMLs. As a consequence, blocking BMP signaling (to, for example, inhibit ocular angiogenesis; Dai et al., 2004; Vogt et al., 2006) could reduce fiber differentiation during normal lens development, but not hinder FGF-dependent lens fiber cell regeneration. If so, then such mechanistic difference in growth factor signaling between normal and post-wounding fiber differentiation should be taken into account when designing therapies to promote lens fiber regeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant human TGFβ1, bovine FGF2, mouse noggin/Fc chimera, and human BMP4 were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Mouse laminin (23017015) and bovine plasma fibronectin (33010-018) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All experiments in which plasma fibronectin was added to tissue culture medium were conducted with lot 1437337. Anti-phospho-Smad1 (ser463/465; 9511) and Anti-phospho-Smad2 (ser465/467; 3108) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Other commercial antibodies used in this study: anti-luciferase (G7451; Promega, Madison, WI, USA); anti-β-galactosidase, (Z3781; Promega), anti-phospho-Smad3 (ser423/425; ab51451; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); anti-total Smad3 (ab84177; Abcam); anti-α smooth muscle actin, clone 1A4 from Dako (Carpinteria, CA, USA); anti-β-actin (clone C4; MilliporeSigma, Darmstadt, Germany); anti-pFAK (Y397; ABT135; MilliporeSigma), and anti-total FAK (clone 77/FAK; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA, USA). The following antibodies were from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa: anti-chick fibronectin B3/D6 (from Dr Doug Fambrough, Johns Hopkins University, USA), anti-chick procollagen 1 SP1.D8 (from Dr Heinz Furthmayr, Stanford University, USA), and the anti-chick α5 integrin antibodies A21F7 and D71E2 (from Dr Alan Horwitz, University of Virginia, USA). A21F7 and D71E2 yielded comparable results. Rabbit anti-mouse CP49/phakinin polyclonal serum (899 or 900) for western blots and affinity-purified C1 for immunocytochemistry were generous gifts of Dr Paul FitzGerald, University of California, Davis, USA, as was the rabbit anti-CP115/filensin antiserum (76). Rabbit anti-chicken aquaporin-0/MP28 antibodies were from Dr Ross Johnson, University of Minnesota, USA. Sheep anti-δ-crystallin antibody was produced in the laboratory of Dr Joram Piatigorsky (NIH) and was a gracious gift of Dr Steve Bassnett (Washington University School of Medicine, USA). All antibodies were used at a dilution of ∼1:500 or 1:1000, except for β-actin (1:15,000) and δ-crystallin (1:3000). SB431542 was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), and CWHM12 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). Poly-D-lysine (P-7886) was from Sigma-Aldrich, as were all other reagents.

Cell culture and treatments

To coat wells with laminin or fibronectin, 96-well tissue culture plate wells were first incubated overnight in 100 μl/well of 0.5 mg/ml poly-D-lysine in 0.15 M boric acid buffer, pH 8.4. Wells were rinsed three times with tissue culture grade dH2O prior to addition of either 33 µg/ml mouse laminin or 12.5 µg/ml bovine plasma fibronectin. Wells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h, after which they were rinsed 3× with Earle's Balanced Salt Solution. Uncoated tissue culture wells were only rinsed in Earle's Balanced Salt Solution. All wells were maintained in M199 medium until cell plating.

Cultures were prepared from embryonic day (E)10 chick lenses on day 0 of culture as previously described in Le and Musil (1998). During this process, cells exterior to the lens capsule are removed and mature lens fiber cells die, leaving a preparation of purified lens epithelial cells. Cells were cultured in the absence of serum in M199 medium plus BOTS (2.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 25 µg/ml ovotransferrin, 30 nM selenium), penicillin G, and streptomycin (M199/BOTS), with or without additives at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were fed every 2 days with fresh medium. We refer to these cultures as dissociated cell-derived monolayers (DCDMLs) to distinguish them from related, but functionally distinct, systems such as central epithelial explants and immortalized lens-derived cell lines (Musil, 2012; Wormstone and Eldred, 2016). Where indicated, DCDMLs were incubated starting day 1 of culture with (final concentration) 3 µM SB431542 or 100 µM CWHM12 for 1 h at 37°C prior to addition of growth factors. Noggin was used at 0.5 µg/ml.

Plasmids and transient transfection of lens cells

One day after plating, DCDML cultures were transfected in M199 medium without BOTS or antibiotics using Lipofectamine 2000 (GibcoBRL) following the manufacturer's suggested protocol. Control experiments confirmed that the efficiency of transient transfection of DCDMLs is consistently ∼70% (Boswell et al., 2009). The SBE4–luciferase (SBE4–Luc) reporter construct (Zawel et al., 1998) was Addgene plasmid 16495 (deposited by Dr Bert Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University, USA).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

DCDMLs grown on glass coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine followed by either laminin or fibronectin were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS and processed as previously described (Le and Musil, 1998, 2001), with the exception of cells incubated at 25°C with 0.1 N NaOH for 10 min prior to fixation to reveal NaOH-insoluble extracellular FN fibrils (Grinnell and Feld, 1979). Immunofluorescence images were captured using a Leica DM LD photomicrography system and Scion Image 1.60 software. Cell plated in uncoated tissue culture plastic wells were fixed and processed for microscopy within the well and imaged using an inverted stage microscope.

[35S]methionine metabolic labeling

DCDML cultures were labeled at 37°C with [35S]methionine for 4 h in methionine- and serum-free Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) (GibcoBRL) and solubilized as previously described (Le and Musil, 1998, 2001). [35S]methionine incorporation into total cellular protein and into δ-crystallin was quantitated after SDS-PAGE using a PhosphorImager (Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX) and Quantity One software.

Cell surface biotinylation

DCDMLs were biotinylated at 4°C with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin. After the reaction was quenched and the cells lysed in SDS, biotinylated proteins were precipitated with streptavidin-agarose and analyzed using western blot (VanSlyke and Musil, 2005).

Immunoblot analysis

Cultures were solubilized directly into SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled. Equal volumes of total cell lysate were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, and the blots probed with primary antibodies. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using secondary antibodies conjugated to either IRDye800 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Limerick, PA, USA) or Alexa Fluor 680 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and directly quantified using the LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey infrared imaging system (Lincoln, NE, USA) and associated software.

Assessment of active TGFβ in conditioned medium

DCDMLs were plated on either laminin-coated, pdFN-coated or uncoated TC plastic. On day 1, the cells were fed with fresh M199/BOTS medium. Conditioned medium was collected on day 3 and centrifuged for 5 min at 725 g to sediment potentially contaminating cells without causing their lysis. Conditioned medium was added to recipient DCDMLs plated on laminin and the cells incubated for 1.5 h. The recipient cells were then lysed and analyzed for total Smad3 and pSmad3 using western blotting. Latent TGFβ was activated through the heating of conditioned medium for 6 min at 80°C, followed with cooling to room temperature and immediate addition to recipient cells (Brown et al., 1990; Santiago-Josefat et al., 2004); unactivated medium was incubated for 6 min at 37°C.

Quantitation

For all western blots, the level of each protein was normalized to the level of β-actin in the same sample. For pSmad3, SBE4–Luc and fiber cell markers (δ-crystallin; CP49 and CP115), the extent to which plating on either pdFN or uncoated TC plastic increased expression was calculated as fold-change over values obtained with cells plated on laminin and cultured in unsupplemented M199/BOTS (defined as control conditions; ctrl) in the same experiment. Levels of αSMA were relatively consistent under control conditions when cells were plated at low density, allowing αSMA to be quantitated in the same manner. Data are graphed as the means±s.e.m. obtained in the number of experiments indicated in the figure. Data were analyzed for significance using the two-tailed paired Student's t-test. Because the amount of FN in control cultures was very close to the limit of detection, it was not possible to meaningfully calculate the fold increase in FN expression induced by pdFN or plating on uncoated TC plastic. The level of reproducibly quantifiable FN was expressed as arbitrary units (AU) obtained using the LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey infrared imaging system software, normalized to the value obtained in the same sample for β-actin. These values are given only when two samples in the same experiment can be quantitatively compared (i.e. when two or more samples have an AU value of ≫0.00; e.g. Fig. 2B,E). Unless otherwise indicated, all experiments were performed a minimum of three times and data from typical experiments presented.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.S.M.; Methodology: J.K.V., L.S.M.; Validation: L.S.M.; Formal analysis: J.K.V., L.S.M.; Investigation: J.K.V., B.A.B., L.S.M.; Writing - original draft: L.S.M.; Writing - review & editing: J.K.V., L.S.M.; Visualization: L.S.M.; Supervision: L.S.M.; Project administration: L.S.M.; Funding acquisition: L.S.M.

Funding

L.S.M., J.K.V., and B.A.B. were supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health [grants R01EY022113 and R01EY028558], and a grant from the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon [grant 1611]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.217240.supplemental

References

- Annes J. P., Chen Y., Munger J. S. and Rifkin D. B. (2004). Integrin alphaVbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta requires the latent TGF-beta binding protein-1. J. Cell Biol. 165, 723-734. 10.1083/jcb.200312172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple D. J., Solomon K. D., Tetz M. R., Assia E. I., Holland E. Y., Legler U. F. C., Tsai J. C., Castaneda V. E., Hoggatt J. P. and Kostick A. M. P. (1992). Posterior capsule opacification. Surv. Ophthalmol. 37, 73-116. 10.1016/0039-6257(92)90073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple D. J., Ram J., Foster A. and Peng Q. (2000). Elimination of cataract blindness: a global perspective entering the new millenium. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, S1-S196. 10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00186-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple D. J., Escobar-Gomez M., Zaugg B., Kleinmann G. and Borkenstein A. F. (2011). Modern cataract surgery: unfinished business and unanswered questions. Surv. Ophthalmol. 56, S3-S53. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi N., Guo S. and Wagner B. J. (2009). Posterior capsular opacification: a problem reduced but not yet eradicated. Arch. Ophthalmol. 127, 555-562. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe D., Garcia C., Wang X., Rajagopal R., Feldmeier M., Kim J.-Y., Chytil A., Moses H., Ashery-Padan R. and Rauchman M. (2004). Contributions by members of the TGFbeta superfamily to lens development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 845-856. 10.1387/ijdb.041869db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell B. A., Overbeek P. A. and Musil L. S. (2008). Essential role of BMPs in FGF-induced secondary lens fiber differentiation. Dev. Biol. 324, 202-212. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell B. A., Le A.-C. N. and Musil L. S. (2009). Upregulation and maintenance of gap junctional communication in lens cells. Exp. Eye Res. 88, 919-927. 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell B. A., VanSlyke J. K. and Musil L. S. (2010). Regulation of lens gap junctions by Transforming Growth Factor beta. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21, 1686-1697. 10.1091/mbc.e10-01-0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell B. A., Korol A., West-Mays J. A. and Musil L. S. (2017). Dual function of TGFβ in lens epithelial cell fate: implications for secondary cataract. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 907-921. 10.1091/mbc.e16-12-0865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. D., Wakefield L. M., Levinson A. D. and Sporn M. B. (1990). Physicochemical activation of recombinant latent transforming growth factor-beta's 1, 2, and 3. Growth Factors 3, 35-43. 10.3109/08977199009037500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call M. K., Grogg M. W., Del Rio-Tsonis K. and Tsonis P. A. (2004). Lens regeneration in mice: implications in cataracts. Exp. Eye Res. 78, 297-299. 10.1016/j.exer.2003.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauss D., Basu S., Rajakaruna S., Ma Z., Gau V., Anastas S., Brennan L. A., Hejtmancik J. F., Menko A. S. and Kantorow M. (2014). Differentiation state-specific mitochondrial dynamic regulatory networks are revealed by global transcriptional analysis of the developing chicken lens. G3 4, 1515-1527. 10.1534/g3.114.012120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang H.-Y., Korshunov V. A., Serour A., Shi F. and Sottile J. (2009). Fibronectin is an important regulator of flow-induced vascular remodeling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 1074-1079. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvekl A. and Ashery-Padan R. (2014). The cellular and molecular mechanisms of vertebrate lens development. Development 141, 4432-4447. 10.1242/dev.107953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J., Kitagawa Y., Zhang J., Yao Z., Mizokami A., Cheng S., Nör J., McCauley L. K., Taichman R. S. and Keller E. T. (2004). Vascular endothelial growth factor contributes to the prostate cancer-induced osteoblast differentiation mediated by bone morphogenetic protein. Cancer Res. 64, 994-999. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas S. L., Sivakumar P., Jones C. J. P., Chen Q., Peters D. M., Mosher D. F., Humphries M. J. and Kielty C. M. (2005). Fibronectin regulates latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF beta) by controlling matrix assembly of latent TGF beta-binding protein-1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18871-18880. 10.1074/jbc.M410762200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danysh B. P. and Duncan M. K. (2009). The lens capsule. Exp. Eye Res. 88, 151-164. 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes L. J., Elliott R. M., Reddan J. R., Wormstone Y. M. and Wormstone I. M. (2007). Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of human lens epithelial cells: TGFbeta regulated gene expression. Mol. Vis. 13, 1181-1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Iongh R. U., Wederell E., Lovicu F. J. and McAvoy J. W. (2005). Transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the lens: a model for cataract formation. Cells Tissues Organs. 179, 43-55. 10.1159/000084508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey S. (2006). Posterior capsule opacification. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 17, 45-53. 10.1097/01.icu.0000193074.24746.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan M. K., Kozmik Z., Cveklova K., Piatigorsky J. and Cvekl A. (2000). Overexpression of PAX6(5a) in lens fiber cells results in cataract and upregulation of (alpha)5(beta)1 integrin expression. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3173-3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edderkaoui M., Hong P., Lee J. K., Pandol S. J. and Gukovskaya A. S. (2007). Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor mediates the prosurvival effect of fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26646-26655. 10.1074/jbc.M702836200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y., Ishiwata-Endo H. and Yamada K. M. (2013). Cloning and characterization of chicken α5 integrin: endogenous and experimental expression in early chicken embryos. Matrix Biol. 32, 381-386. 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Cornwell M. C., Veneziale R. W., Grunwald G. B. and Menko A. S. (2000). N-cadherin function is required for differentiation-dependent cytoskeletal reorganization in lens cells in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 256, 237-247. 10.1006/excr.2000.4819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findl O., Buehl W., Bauer P. and Sycha T. (2010). Interventions for preventing posterior capsule opacification. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 17, CD003738 10.1002/14651858.CD003738.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L., Chen Y., Prijatelj P., Sakai T., Fässler R., Sakai L. Y. and Rifkin D. B. (2005). Fibronectin is required for integrin alphavbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta complexes containing LTBP-1. FASEB J. 19, 1798-1808. 10.1096/fj.05-4134com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliher A. J. and Schiemann W. P. (2006). Beta3 integrin and Src facilitate transforming growth factor-beta mediated induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 8, R42 10.1186/bcr1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A. J., Vega M. D. and Boettiger D. (1999). Modulation of cell proliferation and differentiation through substrate-dependent changes in fibronectin conformation. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 785-798. 10.1091/mbc.10.3.785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F. and Feld M. K. (1979). Initial adhesion of human fibroblasts in serum-free medium: possible role of secreted fibronectin. Cell 17, 117-129. 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90300-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J.-L. and Shalloway D. (1992). Regulation of focal adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase by both cellular adhesion and oncogenic transformation. Nature 358, 690-692. 10.1038/358690a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwon A. (2006). Lens regeneration in mammals: a review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 51, 51-62. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman E. G. and Ruoslahti E. (1979). Distribution of fetal bovine serum fibronectin and endogenous rat cell fibronectin in extracellular matrix. J. Cell Biol. 83, 255-259. 10.1083/jcb.83.1.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson N. C., Arnold T. D., Katamura Y., Giacomini M. M., Rodriguez J. D., McCarty J. H., Pellicoro A., Raschperger E., Betsholtz C., Ruminski P. G. et al. (2013). Targeting of αv integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nat. Med. 19, 1617-1624. 10.1038/nm.3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T. V., Kumar P. K., Sutharzan S., Tsonis P. A., Liang C. and Robinson M. L. (2014). Comparative transcriptome analysis of epithelial and fiber cells in newborn mouse lenses with RNA sequencing. Mol. Vis. 20, 1491-1517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi M., Ota M. and Rifkin D. B. (2012). Matrix control of transforming growth factor-β function. J. Biochem. 152, 321-329. 10.1093/jb/mvs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman G. J., Nicolas F. J., Callahan J. F., Harling J. D., Gaster L. M., Reith A. D., Laping N. J. and Hill C. S. (2002). SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily type I activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol. Pharmacol. 62, 65-74. 10.1124/mol.62.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R. L., Spalton D. J., Hussain A. and Marshall J. (1999). In vitro protein adsorption to 2 intraocular lens materials. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 25, 1109-1115. 10.1016/S0886-3350(99)00137-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonk L. J. C., Itoh S., Heldin C.-H., ten Dijke P. and Kruijer W. (1998). Identification and functional characterization of a Smad binding element (SBE) in the JunB promoter that acts as a transforming growth factor-beta, activin, and bone morphogenetic protein-inducible enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2736, 21145-21152. 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. K., Sheppard D. and Chapman H. A. (2017). TGF-β1 signaling and tissue fibrosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10, a022293 10.1101/cshperspect.a022293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T., Sorgente N., Ishibashi T., Goodnight R. and Ryan S. J. (1987). Immunofluorescent studies of fibronectin and laminin in the human eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 28, 506-514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell C.-G., Zetterström C., Philipson B. and Syrén-Nordqvist S. (1998). Randomized study of the blood-aqueous barrier reaction after phacoemulsification and extracapsular cataract extraction. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 76, 573-578. 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le A.-C. N. and Musil L. S. (1998). Normal differentiation of cultured lens cells after inhibition of gap junction-mediated intercellular communication. Dev. Biol. 204, 80-96. 10.1006/dbio.1998.9030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le A.-C. N. and Musil L. S. (2001). FGF signaling in chick lens development. Dev. Biol. 233, 394-411. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Ouyang H., Zhu J., Huang S., Liu Z., Chen S., Cao G., Li G., Signer R. A. J., Xu Y. et al. (2016). Lens regeneration using endogenous stem cells with gain of visual function. Nature 531, 323-328. 10.1038/nature17181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnola R. J., Werner L., Pandey S. K., Escobar-Gomez M., Znoiko S. L. and Apple D. J. (2000). Adhesion of fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin, and collagen type IV to intraocular lens materials in pseudophakic human autopsy eyes. Part 2: explanted intraocular lenses. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 26, 1807-1818. 10.1016/S0886-3350(00)00747-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamuya F. A., Wang Y., Roop V. H., Scheiblin D. A., Zajac J. C. and Duncan M. K. (2014). The roles of αV integrins in lens EMT and posterior capsular opacification. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 18, 656-670. 10.1111/jcmm.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield K. J., Cerra A. and Chamberlain C. G. (2004). FGF-2 counteracts loss of TGFbeta affected cells from rat lens explants: implications for PCO (after cataract). Mol. Vis. 10, 521-532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y. and Schwarzbauer J. E. (2005). Stimulatory effects of a three-dimensional microenvironment on cell-mediated fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 118, 4427-4436. 10.1242/jcs.02566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margadant C. and Sonnenberg A. (2010). Integrin-TGF-beta crosstalk in fibrosis, cancer and wound healing. EMBO Rep. 11, 97-105. 10.1038/embor.2009.276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaous J. and Hata A. (1997). TGF-beta signalling through the Smad pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 7, 187-192. 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01036-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy J. W. and Chamberlain C. G. (1989). Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) induces different responses in lens epithelial cells depending on its concentration. Development 107, 221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacock W. R., Spalton D. J. and Stanford M. R. (2000). Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of posterior capsule opacification. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 84, 332-336. 10.1136/bjo.84.3.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedovic M., Tomlinson C. R., Call M. K., Grogg M. and Tsonis P. A. (2006). Gene expression and discovery during lens regeneration in mouse: regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition and lens differentiation. Mol. Vis. 12, 422-440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T. and Boettiger D. (2003). Control of intracellular signaling by modulation of fibronectin conformation at the cell- materials interface. Langmuir 19, 1723-1729. 10.1021/la0261500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti F. A., Chauhan A. K., Iaconcig A., Porro F., Baralle F. E. and Muro A. F. (2007). A major fraction of fibronectin present in the extracellular matrix of tissues is plasma-derived. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28057-28062. 10.1074/jbc.M611315200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro A. F., Moretti F. A., Moore B. B., Yan M., Atrasz R. G., Wilke C. A., Flaherty K. R., Martinez F. J., Tsui J. L., Sheppard D. et al. (2008). An essential role for fibronectin extra type III domain A in pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177, 638-645. 10.1164/rccm.200708-1291OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray I. R., Gonzalez Z. N., Baily J., Dobie R., Wallace R. J., Mackinnon A. C., Smith J. R., Greenhalgh S. N., Thompson A. I., Conroy K. P. et al. (2017). αv integrins on mesenchymal cells regulate skeletal and cardiac muscle fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 8, 1118 10.1038/s41467-017-01097-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschler J. L. and Horwitz A. F. (1991). Down-regulation of the chicken alpha 5 beta 1 integrin fibronectin receptor during development. Development. 113, 327- 337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil L. S. (2012). Primary cultures of embryonic chick lens cells as a model system to study lens gap junctions and fiber cell differentiation. J. Membr. Biol. 245, 357-368. 10.1007/s00232-012-9458-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibourg L. M., Gelens E., Kuijer R., Hooymans J. M. M., van Kooten T. G. and Koopmans S. A. (2015). Prevention of posterior capsular opacification. Exp. Eye Res. 136, 100-115. 10.1016/j.exer.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Pierschbacher M. and Ruoslahti E. (1981). Deposition of plasma fibronectin in tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3218-3221. 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T. S., Eguchi G. and Takeichi M. (1971). The expression of differentiation by chicken lens epithelium in in vitro cell culture. Dev. Growth Differ. 13, 323-336. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1971.00323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman L. A., Fernandez C. R., So S. and Rawlins J. T. (2006). Erk1/2 signaling is required for Tgf-beta 2-induced suture closure. Dev. Dyn. 235, 1292-1299. 10.1002/dvdy.20656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. M., Portz L. M., Fullenwider J. and Mosher D. F. (1990). Co-assembly of plasma and cellular fibronectins into fibrils in human fibroblast cultures. J. Cell Biol. 111, 249-256. 10.1083/jcb.111.1.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek E., Ju W. J., Heyer J., Escalante-Alcalde D., Stewart C. L., Weinstein M., Deng C., Kucherlapati R., Böttinger E. P. and Roberts A. B. (2001). Functional characterization of transforming growth factor beta signaling in Smad2-and Smad3-deficient fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19945-19953. 10.1074/jbc.M102382200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. L. (2006). An essential role for FGF receptor signaling in lens development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 726-740. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S. (2004). Relationship between posterior capsule opacification and intraocular lens biocompatibility. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 23, 283-305. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S., Kobata S., Yamanaka O., Yamanaka A., Okubo K., Oka T., Hosomi M., Kano Y., Ohmi S., Uenoyama S., et al. (1993). Cellular fibronectin on intraocular lenses explanted from patients. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 231, 718-721. 10.1007/BF00919287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S., Kawashima Y., Miyamoto T., Okada Y., Tanaka S.-I., Ohmi S., Minamide A., Yamanaka O., Ohnishi Y., Ooshima A. et al. (1998a). Immunolocalization of prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunits, alpha-smooth muscle actin, and extracellular matrix components in human lens capsules with lens implants. Exp. Eye Res. 66, 283-294. 10.1006/exer.1997.0434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S., Miyamoto T., Yamanaka A., Kawashima Y., Okada Y., Tanaka S.-I., Yamanaka O., Ohmi S., Ohnishi Y. and Ooshima A. (1998b). Immunohistochemical evaluation of cellular deposits on posterior chamber intraocular lenses. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 236, 758-765. 10.1007/s004170050155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S., Miyamoto T., Kawashima Y., Okada Y., Yamanaka O., Ohnishi Y. and Ooshima A. (2000). Immunolocalization of TGF-beta1, -beta2, and -beta3, and TGF-beta receptors in human lens capsules with lens implants. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 238, 283-293. 10.1007/s004170050354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S., Miyamoto T., Ishida I., Shirai K., Ohnishi Y., Ooshima A. and McAvoy J. W. (2002). TGFbeta-Smad signalling in postoperative human lens epithelial cells. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 86, 1428-1433. 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandbo N. and Dulin N. (2011). Actin cytoskeleton in myofibroblast differentiation: ultrastructure defining form and driving function. Transl. Res. 158, 181-196. 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Josefat B., Mulero-Navarro S., Dallas S. L. and Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2004). Overexpression of latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein 1 (LTBP-1) in dioxin receptor-null mouse embryo fibroblasts. J. Cell Sci. 117, 849-859. 10.1242/jcs.00932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechler J. L., Takada Y. and Schwarzbauer J. E. (1996). Altered rate of fibronectin matrix assembly by deletion of the first type III repeats. J. Cell Biol. 134, 573-583. 10.1083/jcb.134.2.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. M. and Spalton D. J. (1994). Changes in anterior chamber flare and cells following cataract surgery. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 78, 91-94. 10.1136/bjo.78.2.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihan M., Pathania M., Wang Y. and Duncan M. (2017). Regulation of TGF-β bioavailability in lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58, 3786. [Google Scholar]

- Shirakihara T., Horiguchi K., Miyazawa K., Ehata S., Shibata T., Morita I., Miyazono K. and Saitoh M. (2011). TGF-β regulates isoform switching of FGF receptors and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. EMBO J. 30, 783-795. 10.1038/emboj.2010.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponer U., Pieh S., Soleiman A. and Skorpik C. (2005). Upregulation of alphavbeta6 integrin, a potent TGF-beta1 activator, and posterior capsule opacification. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 31, 595-606. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueiras V. M., Moy V. T. and Ziebarth N. M. (2015). Lens capsule structure assessed with atomic force microscopy. Mol. Vis. 21, 316-323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliana L., Evans M. D., Ang S. and McAvoy J. W. (2006). Vitronectin is present in epithelial cells of the intact lens and promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition in lens epithelial explants. Mol. Vis. 12, 1233-1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P. and Arthur H. M. (2007). Extracellular control of TGFbeta signalling in vascular development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 857-869. 10.1038/nrm2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To W. S. and Midwood K. S. (2011). Plasma and cellular fibronectin: distinct and independent functions during tissue repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 4, 21 10.1186/1755-1536-4-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanSlyke J. K. and Musil L. S. (2005). Cytosolic stress reduces degradation of connexin43 internalized from the cell surface and enhances gap junction formation and function. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5247-5257. 10.1091/mbc.e05-05-0415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasavada A. R. and Praveen M. R. (2014). Posterior capsule opacification after phacoemulsification: annual review. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 3, 235-240. 10.1097/APO.0000000000000080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veevers-Lowe J., Ball S. G., Shuttleworth A. and Kielty C. M. (2011). Mesenchymal stem cell migration is regulated by fibronectin through α5β1-integrin-mediated activation of PDGFR-β and potentiation of growth factor signals. J. Cell Sci. 124, 1288-1300. 10.1242/jcs.076935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]