Abstract

Background:

Using scientific results to inform policy that improves health and well-being of vulnerable community members is essential to community-based participatory research (CBPR)

Objectives:

We describe “policy briefs,” a mechanism developed to apply the results of CBPR projects with migrant and seasonal farmworkers to policy changes.

Lessons Learned:

Policy briefs are two-page summaries of published research that address a single policy issue using language and graphics to make the science accessible to diverse audiences. Policy brief topics are selected by community advocates, based on collaborative research, and address a specific policy or regulation. Development is an iterative process of discussion with community representatives. Briefs have been used to provide information to advocates, state and national policy makers, and the public.

Conclusions:

Disseminating CBPR results to address policy is needed. Collaborating with community partners to produce policy briefs ensures that information about concerns and struggles reflects their priorities.

Keywords: Policy, dissemination, implementation, vulnerable communities, community Education

Background

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach that uses science to improve the health and well-being of individuals who live in the communities in which the science is conducted, as well as to improve the health and well-being of those living in similar communities. Using a CBPR approach, investigators work with community members to present scientific results in a format that community members can use, as in the development of health education and intervention materials.1 A CBPR approach supports presenting information through the policy process to compel changes that address the health and well-being of community members.2

A CBPR approach seeks to tailor research to the needs of vulnerable communities in addressing health exposures and health inequities.3 As such, research using a CBPR approach should address the health hazards and needs of the communities in which it is conducted. The results of this research should provide community members with tools that they can use to protect and improve their health, and that inform public health policy.4–5

Using the scientific results of CBPR conducted with farmworker communities to address policy is especially important. Like the members of other vulnerable populations, farmworkers often have limited formal education, low incomes, and inadequate access to health care.6–7 In addition, farmworkers are largely Latino immigrants (most from Mexico) who have limited English language skills and often do not have legal documents to work in the United States, making them hesitant to address inequities in policy and regulation publicly.8 Migrant farmworkers with H-2A visas, although working with legal documents, are also hesitant to address policy and regulatory problems for fear of retribution from their employers.9–11 Finally, farmworker vulnerability is amplified due to many exceptions to occupational health and safety regulations that apply only to agriculture (referred to as “agricultural exceptionalism”).12

We have discussed using the science developed through CBPR projects to work with farmworker communities through health education.1 These efforts have included mass communication with farmworkers using posters, flyers and radio spots;13 broad occupational health education based on safety videos and photonovelas;14–15 and targeted programs using lay health educators.16–19 Our efforts to apply the results of CBPR projects to public policy are also extensive, but not well documented. In this paper we describe “policy briefs,” one mechanism which has been used by farmworker advocates in addressing policy and regulatory change. Our discussion expands on the work of others on why and how to develop research summaries in support of policy advocacy.20

Lessons Learned

Policy Briefs

CBPR, like all science, must be based on the highest standards. Those wanting to use the scientific findings of CBPR to change public policy and regulations are often confronted by powerful interests who profit from the status quo. These powerful interests, which include corporations that manufacture agricultural chemicals and machinery, as well as large commodity producer and processor associations, use their resources to dispute CBPR scientific results in an effort to maintain their dominant position. Therefore, the publication of CBPR scientific results in the peer-reviewed literature is an important component in the political process for affecting changes. Public agency and legislative staff often rely on the peer-reviewed literature. Presentations based on peer-reviewed articles can have greater weight than those based on the experiences of community members.

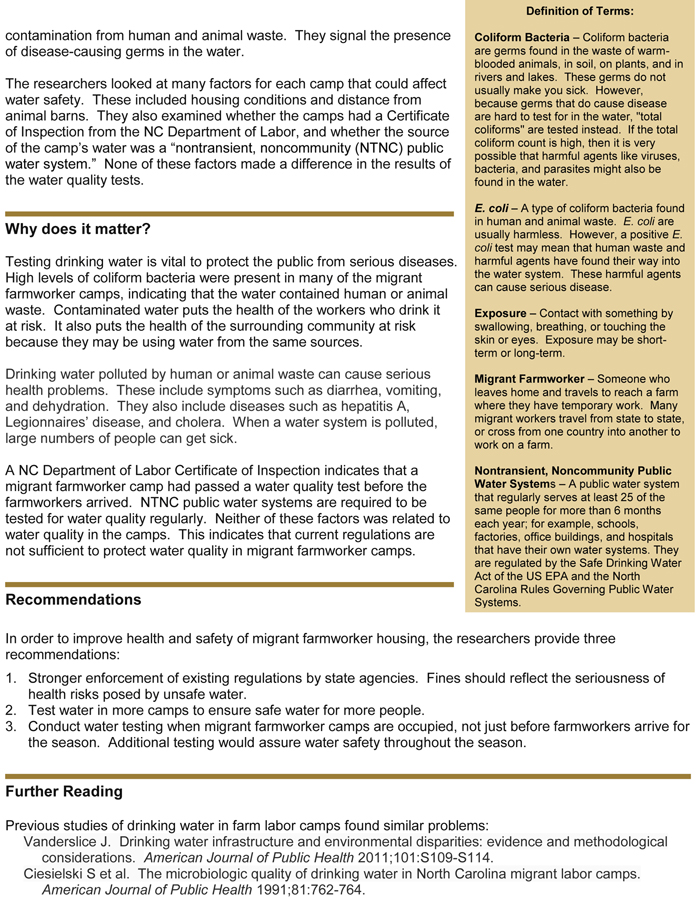

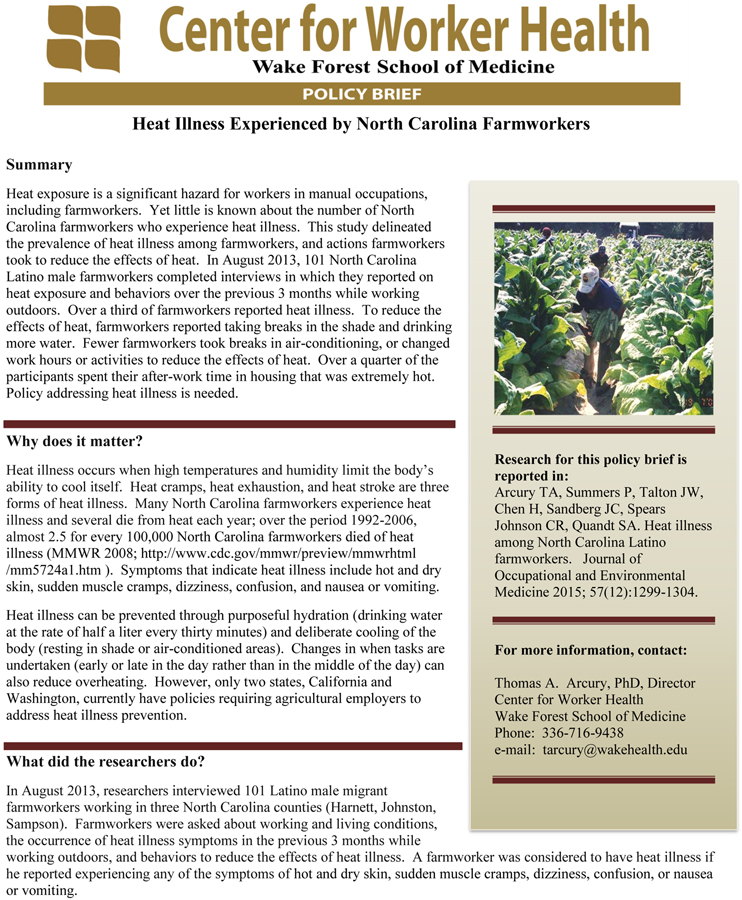

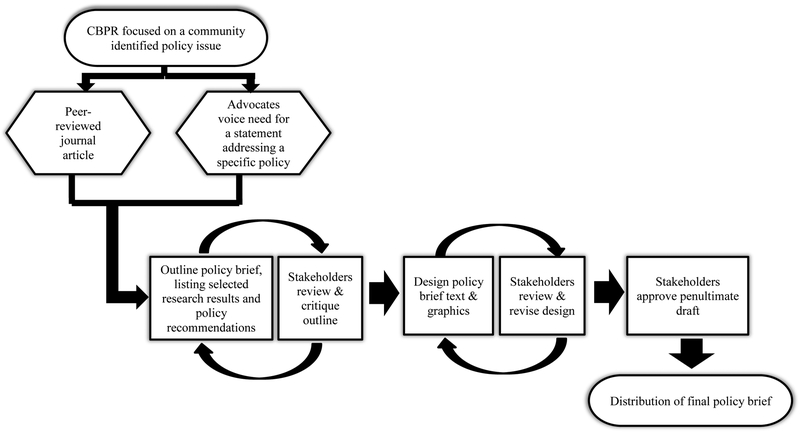

Providing a summary of results from peer-reviewed papers in a format that is easily accessible to community advocates, and to policy makers (often elected officials with limited content area knowledge, training, or time), can facilitate policy discussion and change. Our approach to summarizing results for consumption by community members and policy makers is the “policy brief.” A policy brief is a two page (front and back of a single sheet) document that uses graphics and text to summarize the key results of a scientific paper, and link those results to specific policy recommendations. Policy briefs provide some background information on the issue being addressed and a short description of the research methods. They also provide the citation to the full-work on which the brief is based.

We have developed 13 policy briefs since 2010 based on the results of research with the North Carolina farmworker community (Table 1; Figures 1 and 2). These briefs address current issues that are of considerable concern to farmworkers, service providers, and advocates, and for which policy changes could improve the health of farmworkers and their families: pesticide exposure, occupational nicotine exposure, housing, child labor, and access to health care.

Table 1:

Policy briefs developed for addressing policy affecting migrant and seasonal farmworkers.

| Topic | Regulation or Policy Addressed | Policy Brief Title and Source |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Exposures | US EPA Worker Protection Standard Hazard Communications Standard OSHA Field Sanitation Standard Occupational Safety and Health Act NC Occupational Safety and Health Act Hazard Communications Standard OSHA Field Sanitation Standard |

Biomarkers of Farmworker Pesticide Exposure in North Carolina36–37 Meeting the Requirements for Occupational Safety and Sanitation for Migrant Farmworkers in North Carolina39 Cotinine Levels for North Carolina Farmworkers40 Heat Illness Experienced by North Carolina Farmworkers41 |

| Housing | Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act OSHA Temporary Labor Camp Standards US EPA Worker Protection Standard NC Migrant Housing Act | Housing Conditions in Temporary Labor Camps for Migrant Farmworkers in North Carolina42 Migrant Farmworker Housing Violations in North Carolina43 Drinking Water Quality in NC Migrant Farmworker Camps44 Quality of Kitchen Facilities in NC Migrant Farmworker Camps45 Residential Pesticide Exposure in North Carolina Migrant Farmworker Camps46 |

| Hired Youth Farmworkers | Child Labor Requirements in Agricultural Occupations Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act Occupational Safety and Health Act NC Occupational Safety and Health Act Hazard Communications Standard OSHA Field Sanitation Standard | Safety and Injury Characteristics of Youth Farmworkers Working in North Carolina Agriculture47 Hired Youth Farmworkers in North Carolina: Work Safety Climate and Safety22 |

| Health Services | Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | Providing Information About the Affordable Care Act to Latino Immigrants Alcohol Consumption and Potential for Dependence among North Carolina Farmworkers48 |

All policy briefs are available http://www.wakehealth.edu/Center-for-Worker-Health/Policy-Briefs.htm

Figure 1:

Policy brief, Drinking Water Quality in NC Migrant Farmworker Camps.

Figure 2:

Policy brief, Heat Illness Experienced by North Carolina Farmworkers.

Developing a Policy Brief

Topics selected for policy briefs must meet three criteria. First, the topic must be identified as important to farmworker health by community representatives or advocates. Second, it must be based on research that has been conducted collaboratively with community representatives or advocates. Our CBPR partnership with farmworker organizations in North Carolina has allowed us to develop collaborative research that addresses their concerns. We have developed large research projects that respond directly to the concerns of clinicians who provide care for farmworkers (i.e., NIOSH and NIH funded projects on green tobacco sickness and farmworker skin disease) and of service providers (i.e., NIH funded projects on farmworker housing). When data on specific policy issues raised by community partners are not available, as in the case of child labor issues and the Affordable Care Act, we have expanded existing research programs to collect these data. All of these projects have included community organization and clinic staff as co-investigators.

Finally, the policy brief must address a clear policy or regulation. Policy briefs have addressed pesticide exposure for farmworkers, an issue with which the US Environmental Protection Agency has been involved over the past decade in developing revised safety standards, the Worker Protection Standard (http://www.epa.gov/pesticide-worker-safety/revisions-worker-protection-standard); housing regulations for migrant farmworkers, the focus of a national discussion concerning housing quality and enforcement of federal and state standards;21 and child labor, for which current regulations allow exceptions to child labor laws that apply only to agriculture and allow children as young as 10 years old to work for hire in one of the nation’s most hazardous industries.22–26 Other policy briefs have addressed specific health services concerns, including farmworker access to insurance through the Affordable Care Act, and alcohol consumption and dependence. Generally, the authors of the published papers, along with community representatives and advocates (often those collaborating in the CBPR), have expertise in the policy issue being addressed; if needed, individuals with the additional expertise would be contacted.

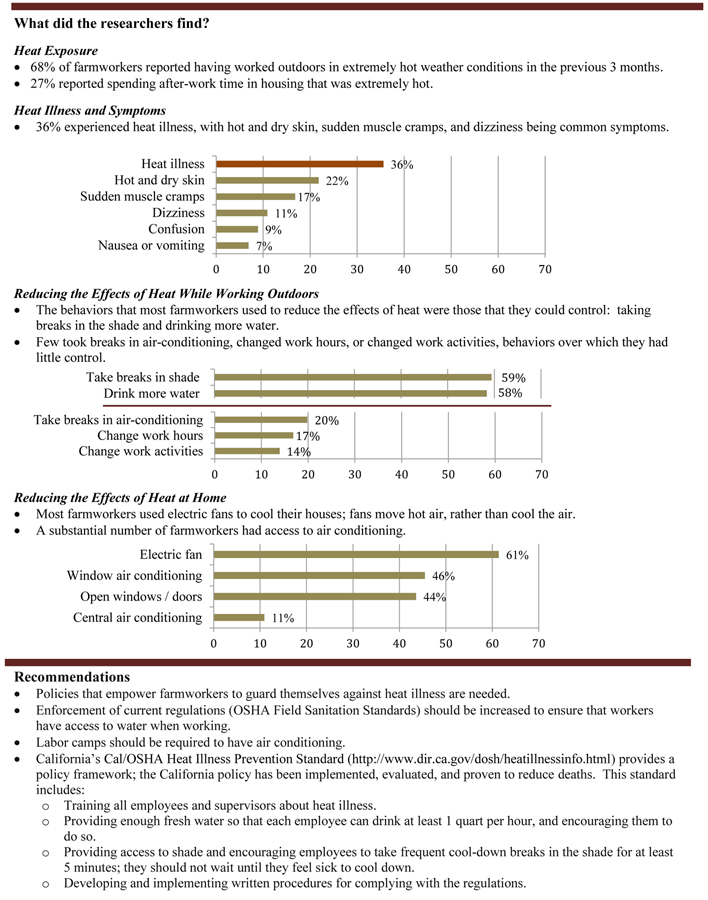

Policy brief development is a component of CBPR.2 Community participation is key for the iterative design process to ensure that language and policy recommendations are appropriate for the intended audience (Figure 3). The development process begins with CBPR focused on a community identified policy issue. Research results are presented in a peer-reviewed journal article. Advocates identify germane issues and prioritize messages. An outline of the brief, listing research results and policy recommendations is developed, reviewed, and revised by community and academic partners. When consensus is reached on content, work begins on design, including text and graphics. Outlines and draft design are reviewed by individuals and presented at project meetings for broader discussion. Drafts must go through several iterations in which content and presentation are refined. This process can take several months to allow all stakeholders, including multiple advocates, community partners and scientists, to critique each new version of a policy brief. Individual stakeholders read and comment on the different drafts. Due to the time it takes for a policy brief to be developed, the process is often begun when a research paper is submitted for review; the review and revision process of a scientific paper often takes longer than the design of the policy brief.

Figure 3:

Flow Chart, Designing a Policy Brief.

The steps for developing a policy brief begin with summarizing research results and outlining policy recommendations supported by the research results. Text and graphics to present the results are drafted. A draft brief is then presented to different stakeholders (community members, advocates, services providers, researchers) for comment and critique, and the draft is refined until consensus is reached. Drafts are presented to groups of stakeholders for review. Advocates and community groups are important partners in the design process, ensuring that pertinent information is prominent, and accessible to non-specialists. We use a graphic design artist, when possible. Engaging multiple stakeholders in drafting policy briefs provides feedback and perspectives from other vantage points. Encouraging stakeholders in the design of policy briefs increases their impact in a wider audience.

The content of policy briefs is designed for focused and concise communication, using simple and consistent language to address a single topic. Content generally includes a summary of the brief, a short description of the policy issue being addressed (“Why does it matter?”), a photo related to the topic, an explanation of how data were collected (“What did the researchers do?”), and definitions for technical terms. Research results (“What did the researchers find?”) are presented clearly, often using graphics to supplement text. Graphics include simple charts, including pie charts and bar graphs. More complex findings are presented as text bullets. Specific policy recommendations are presented. The citation for the peer-reviewed paper(s) on which the policy brief is based is included. Contact information is provided. When appropriate, and space allows, references for further reading are included.

Using Policy Briefs

Farmworker advocates have used the policy briefs to address diverse audiences. They are used to educate other farmworker advocates and outreach workers, such as Student Action with Farmworker staff and interns. The policy briefs provide a summary of key points from published articles which advocates and community organization staff may not have the time or background to read. They are used to inform policy makers and regulators. Policy briefs have been used by advocates to provide facts in letters to government officials, or an entire brief may be included with a letter. For example, North Carolina Farmworker Advocacy Network members have used policy briefs to document specific issues, such as child labor practices and farmworker pesticide exposure, in letters to the North Carolina Commissioner of Labor. Policy briefs have also been used in letters to the US Environmental Protection Agency Administrator in reference to changes in the Worker Protection Standard (pesticide safety). Advocates also use the policy briefs when consulting with legislators and enforcement officials; rather than give them a policy brief, the advocates base their oral presentations on the brief. Policy briefs are used to inform the general public about farmworker issues. They are included in blogs and provide the basis for public presentations.

Policy briefs often address long-standing issues; in these instances, the release of a policy brief may be delayed to correspond to the start of a policy initiative. In all but one instance, policy briefs have been released only after the journal article on which they are based have been accepted for publication. For a recent policy brief addressing a timely issue, recruiting Latinos for coverage under the Affordable Care Act, the brief was developed quickly to be used during the ACA enrollment period, before a manuscript was written and submitted. A paper using these data has been written, but it addresses issues separate from those reported in the policy brief.

Advocates have seldom used the policy briefs to provide information directly to farmworkers because direct community education is developed for this purpose by our CBPR partners. These partners employ the research results described in the policy briefs to develop specific procedures for farmworkers to use to improve occupational safety and family health. This community education often speaks directly to farmworkers, for example through radio announcements and lay health educator programs, and the educational materials are shared with farmworker organizations to use in their programs.

We have not conducted evaluations to determine the efficacy of the policy briefs. However, that advocates and community organization leaders request that we continue to develop them indicates they are filling a need.

Conclusion

Dissemination of results from CBPR beyond the scientific literature continues to be a concern.27–29 Discussions of how best to return results to individual participants and to their larger communities have been presented.30–31 Several case studies of how CBPR has included campaigns to change specific policies are available.32–35 Those engaged in CBPR programs have seldom discussed how to craft tools that can be used for ongoing policy discussions.20 Policy briefs provide quick access to current research findings for policy makers, as well as for advocates, service providers, community members, and other stakeholders. Using uncomplicated language helps a wider range of audiences engage with the findings. Employing simple graphics allows the “numbers to talk.” Policy briefs documenting the hazards migrant farmworkers endure have been a vehicle for advocacy. Collaborating with community partners to produce policy briefs ensures that information about concerns and struggles reflects their priorities. Further discussion of how CBPR results should and can be used to affect policy change is needed.

Finally, the policy brief development and review process has additional dividends for the CBPR process. It strengthens the relationship between scientists and advocates, and those conversations and relationships can lead to research in areas of top priority to advocates and the larger community.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant R01 ES08739).

Contributor Information

Thomas A. Arcury, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Program in Community Engagement, Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Center for Worker Health, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Melinda F. Wiggins, Student Action with Farmworkers

Carol Brooke, Workers’ Rights Project, North Carolina Justice Center.

Anna Jensen, North Carolina Farmworkers Project.

Phillip Summers, Program in Community Engagement, Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Center for Worker Health, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dana C. Mora, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Center for Worker Health, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Sara A. Quandt, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Division of Public Health Sciences, Program in Community Engagement, Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Center for Worker Health, Wake Forest School of Medicine

References

- 1.Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Alcohol consumption and risk for dependence among male Latino migrant farmworkers compared to Latino nonfarmworkers in North Carolina In: Leong F, Eggerth D, Chang D, Flynn M, Ford K, Martinez R, editors. Occupational health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities: formulating research needs and directions. Washington, DC: APA Press;2016. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Community-based participatory research and occupational health disparities: pesticide exposure among immigrant farmworkers In: Leong F, Eggerth D, Chang D, Flynn M, Ford K, Martinez R, editors. Occupational health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities: formulating research needs and directions. Washington, DC: APA Press;2016. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen PG, Diaz N, Lucas G, Rosenthal MS. Dissemination of results in community-based participatory research. Am J Prev Med. 2010; 39: 372–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100(Suppl 1): S40–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll DJ, Samardick R, Gabbard SB, Hernandez T. Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2001–2002: A demographic and employment profile of United States farm workers. Washington (DC): US Department of Labor, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy, Office of Programmatic Policy; 2005. Research Report No. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Delivery of health services to migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28:345–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan K, Economos J, Salerno MM. Farmworkers make their voices heard in the call for stronger protections from pesticides. New Solut. 2015;25(3):362–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arcury TA, Summers P, Talton JW, Nguyen HT, Chen H, Quandt SA. Job characteristics and work safety climate among North Carolina farmworkers with H-2A visas. J Agromedicine. 2015a;20(1):64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer M Close to slavery: guestworker programs in the United States. Montgomery, AL: Southern Poverty Law Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman E 2011. No way to treat a guest: why the H-2A Agricultural Visa Program fails U.S. andforeign workers. Washington, DC: Farmworker Justice; Available from: http://www.farmworkerjustice.org/sites/default/files/documents/7.2.a.6%20No%20Way%20To%20Treat%20A%20Guest%20H-2A%20Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiggins M Farm labor and the struggle for justice in the Eastern United States fields In: Arcury TA, Quandt SA, editors. Latino farmworkers in the eastern United States: health, safety, and justice. New York: Springer;2009. p. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane CM Jr, Vallejos QM, Marín AJ, Quandt SA, Grzywacz JG, Galván L, et al. Pesticide safety radio public service announcements. Winston-Salem, NC: Center for Worker Health, Wake Forest University School of Medicine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Lane CM Jr., Marin T, Rao P. El terror invisible: pesticide safety for North Carolina [Spanish language pesticide safety education video.] Winston-Salem, NC: Wake Forest University School of Medicine; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Aprenda sobre la enfermedad del tabaco verde: la experiencia de Juan – una fotonovela / Learning about Green Tobacco Sickness: Juan’s Experience. – a photonovel. Winston-Salem, NC: Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Austin CK, Cabrera LF. Preventing occupational exposure to pesticides: using participatory research with Latino farmworkers to develop an intervention. J Immigr Health. 2001a;3(2):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Pell AI I. Something for everyone? A community and academic partnership to address farmworker pesticide exposure in North Carolina. Environ Health Perspect. 2001b;109(Suppl 3):435–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quandt SA, Grzywacz JG, Talton JW, Trejo G, Tapia J, D’Agostino RB Jr, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a lay health promoter-led community-based participatory pesticide safety intervention with farmworker families. Health Promot Pract. 2013a;14:425–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arcury TA, Marín A, Snively BM, Hernández-Pelletier M, Quandt SA. Reducing farmworker residential pesticide exposure: evaluation of a lay health advisor intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(3):447–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izumi BT, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Reyes AG, Martin J, Lichtenstein RL, et al. The one-pager: a practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(2):141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss Joyner A, George L, Hall ML, Jacobs IJ, Kissam ED, Latin S, et al. Federal farmworker housing standards and regulations, their promise and limitations, and implications for farmworker health. New Solut. 2015;25(3):334–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arcury TA, Rodriguez G, Kearney GD, Arcury JT, Quandt SA. Safety and injury characteristics of youth farmworkers in North Carolina: a pilot study. J Agromedicine. 2014b;19(4):354–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kearney GD, Rodriguez G, Arcury JT, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Work safety climate, safety behaviors, and occupational injuries of youth farmworkers in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(7):1336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Human Rights Watch. Fingers to the bone: United States failure to protect child farmworkers. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2000. [Accessed 2016 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/frmwrkr/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Human Rights Watch. Tobacco’s hidden children: hazardous child labor in United States tobacco farming. Human Rights Watch; 2014. [Accessed 2016 Feb 1]. Available from: http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/us0514_UploadNew.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety. 2014 Fact Sheet: Childhood Agricultural Injuries in the U.S 2013. [Accessed 2016 Feb 1]. Available from: http://www3.marshfieldclinic.org/proxy/MCRF-Centers-NFMC-NCCRAHS2014_Child_Ag_Injury_FactSheet1.pdf

- 27.Chen PG, Diaz N, Lucas G, Rosenthal MS. Dissemination of results in community-based participatory research. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haynes EN, Elam S, Burns R, Spencer A, Yancey E, Kuhnell P, et al. Community Engagement and Data Disclosure in Environmental Health Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(2):A24–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burke JG, Hess S, Hoffmann K, Guizzetti L, Loy E, Gielen A, et al. Translating community-based participatory research principles into practice. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2013;7(2):115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brody JG, Dunagan SC, Morello-Frosch R, Brown P, Patton S, Rudel RA. Reporting individual results for biomonitoring and environmental exposures: lessons learned from environmental communication case studies. Environ Health. 2014;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morello-Frosch R, Varshavsky J, Liboiron M, Brown P, Brody JG. Communicating results in post-Belmont era biomonitoring studies: lessons from genetics and neuroimaging research. Environ Res. 2015;136:363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vásquez VB, Minkler M, Shepard P. Promoting environmental health policy through community based participatory research: a case study from Harlem, New York. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):101–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vásquez VB, Lanza D, Hennessey-Lavery S, Facente S, Halpin HA, Minkler M. Addressing food security through public policy action in a community-based participatory research partnership. Health Promot Pract. 2007;8(4):342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen DM, Minkler M, Vásquez VB, Baden AC. Community-based participatory research as a tool for policy change: a case study of the Southern California Environmental Justice Collaborative. Rev Policy Res. 2006;23(2):339–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen DM, Minkler M, Vásquez VB, Kegler MC, Malcoe LH, Whitecrow S. Using community-based participatory research to shape policy and prevent lead exposure among Native American children. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(3):249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Chen H, Vallejos QM, Galván L, Whalley LE, et al. Variation across the agricultural season in organophosphorus pesticide urinary metabolite levels for Latino farmworkers in eastern North Carolina: project design and descriptive results. Am J Ind Med. 2009b;52(7):539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Isom S, Vallejos QM, Galvan L, Whalley LE, et al. Seasonal variation in the measurement of urinary pesticide metabolites among Latino farmworkers in eastern North Carolina. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2009c;15(4):339–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Talton JW, Chen H, Vallejos QM, Galván L, et al. Repeated pesticide exposure among North Carolina migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(8):802–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whalley LE, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, Vallejos QM, Walkup M, Chen H, et al. Migrant farmworker field and camp safety and sanitation in Eastern North Carolina. J Agromedicine. 2009;14(4):421–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arcury TA, Laurienti PJ, Talton JW, Chen H, Howard TD, Summers P, et al. Urinary cotinine levels among Latino tobacco farmworkers in North Carolina compared to Latinos not employed in agriculture. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016a;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arcury TA, Summers P, Talton JW, Chen H, Sandberg JC, Spears Johnson CR, et al. Heat illness among North Carolina Latino farmworkers. J Occup Environ Med. 2015b;57(12):1299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallejos QM, Quandt SA, Grzywacz JG, Isom S, Chen H, Galván L, et al. Migrant farmworkers’ housing conditions across an agricultural season in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(7):533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arcury TA, Weir M, Chen H, Summers P, Pelletier LE, Galván L, et al. Migrant farmworker housing regulation violations in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 52012;5:191–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bischoff W, Weir M, Summers P, Chen H, Quandt SA, Liebman AK, et al. The quality of drinking water in North Carolina farmworker camps. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quandt SA, Summers P, Bischoff WE, Chen H, Wiggins MF, Spears CR, et al. Cooking and eating facilities in migrant farmworker housing in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2013b;103:e78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arcury TA, Lu C, Chen H, Quandt SA. Pesticides present in migrant farmworker housing in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 2014a;57(3):312–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arcury TA, Rodriguez G, Kearney GD, Arcury JT, Quandt SA. Safety and injury characteristics of youth farmworkers in North Carolina: a pilot study. J Agromedicine. 2014;19(4):354–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arcury TA, Talton JW, Summers P, Chen H, Laurienti PJ, Quandt SA. Alcohol consumption and risk for dependence among male Latino migrant farmworkers compared to Latino nonfarmworkers in North Carolina. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016b;40(2):377–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]