Abstract

Introduction:

The lack of policy, practice and research action on physical activity and features of the physical (built and natural) environments in rural, remote and northern settings is a significant threat to population health equity in Canada. This paper presents a synthesis of current evidence on the promotion of physical activity in non-urban settings, outcomes from a national priority-setting meeting, and a preliminary call to action to support the implementation and success of population-level initiatives targeting physical activity in non-urban settings.

Methods:

We conducted a “synopses of syntheses” scoping review to explore current evidence on physical activity promotion in rural, remote, northern and natural settings. Next, we facilitated a collaborative priority-setting conference with 28 Canadian experts from policy, research and practice arenas to develop a set of priorities on physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities. These priorities informed the development of a preliminary Canadian call to action.

Results:

We identified a limited number of reviews that focused on physical activity and the built environment in rural, remote and northern communities. At the prioritysetting conference, participants representing rural, remote and northern settings identified top priorities for policy, practice and research action to begin to address the gaps and issues noted in the literature. These priorities include self-identifying priorities at the community level; compiling experiences; establishing consistency in research definitions and methods; and developing mentorship opportunities.

Conclusion:

Coordinated action across policy, practice and research domains will be essential to the success of the recommendations presented in this call to action.

Keywords: rural health, remote health, health policy, environment design, physical activity, health equity

Highlights

Physical activity promotion must reflect the realities and context of rural and remote communities.

Research literature on physical activity promotion in rural and remote communities does not yet provide adequate direction to communities or public health agencies.

In November 2015, experts gathered to review existing evidence and to develop priorities to enhance physical activity promotion in rural, remote and northern settings in Canada.

Priorities were summarized in a Canadian call to action that provides preliminary direction to support equitable action on rural and remote physical activity promotion across Canada, including the need for more culturally relevant, Indigenous-led research.

Introduction

Regular physical activity is an important determinant of health. Increased physical activity decreases the risk of several chronic diseases and improves overall well-being.1 Yet, nearly 80% of Canadian adults do not complete the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each week.2 It is widely accepted that an individual’s physical activity is influenced by various determinants, including the physical, built and natural environments (see Box 1 for definitions). Policies and changes in environmental infrastructure can play a meaningful role in creating supportive settings to increase population-level physical activity.3

BOX 1 Key definitions

The terms “physical environment,” “built environment” and “natural environment” are variously defined in the literature and are often component parts of a single definition. For clarity in conducting this review, we used the following definitions:

Physical environment:

the perceived characteristics of the physical setting in which individuals spend their time. This may include aspects of urban design, traffic density and speed, distance to and design of venues for physical activity, e.g. recreation facilities, weather and air quality, and crime and safety.4

Built environment:

features of the environment that are influenced by human design. This definition generally includes three main components: transportation systems; land development patterns; and the design and arrangement of buildings and other structures.5

Natural environment:

the aspects of the natural world largely untouched by humans. Natural environments can be viewed as a continuum between wild nature and areas under some human influence, such as public parks or cultivated fields.6

There appears to be significant support among decision makers, politicians, bureaucrats, members of the media and policy advocates in Canada as well as the general public for population-level interventions that promote physical activity by targeting the built and physical environment. For example, a 2016 survey conducted by members of our team found that 95.3% of policy influencers support improving opportunities for physical activity through neighbourhood revitalization programs.7 Furthermore, 87.7% of policy influencers and 92.8% of the general public support implementing transportation policies designed to promote bicycling.

Despite general support for policies and built environment interventions to promote physical activity, significant evidence, policy and practice gaps exist in non-urban settings. Evidence on the promotion of physical activity at the environmental level has focused on urban settings, with little attention paid to settings outside of cities and metropolitan areas.8 This is problematic as populations outside of urban areas have fewer resources or poorer accessibility to existing resources than their urban counterparts, which contributes to increased prevalence of adverse health outcomes in rural populations.8‑10

Non-urban settings also experience inequities in the promotion of physical activity from both a practice and policy perspective. Communities with a population of less than 10 000 experience more barriers to accessing physical activity than larger communities with populations of 250 000 or greater.11 Not surprising, a higher proportion of parents in rural, remote and northern regions report poor accessibility as a barrier to their children’s physical activity compared to the Canadian average. 11 Local governments in rural, remote and northern regions may also have other challenges to do with infrastructure, such as limited revenue and financial capacity, short construction seasons and high cost of living.12 This makes it difficult to provide community programming and create environments that support physical activity. In short, the State of Rural Canada 2015 reports, “We have been neglecting rural Canada … Fundamentally, we have forgotten how to re-invest in rural and small town places….”13, p. i

Having a better understanding of the nuanced contexts of non-urban settings has the potential to improve health equity and contribute to more effective policies and environmental interventions that promote physical activity across settings. With this in mind, we conducted a synthesis of the review-level literature on the promotion of physical activity in nonurban settings from the perspective of the built environment. We then held a conference with invited experts to develop a set of priorities for practice, policy implementation and research to support physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities. Taken together, this process resulted in the collaborative development of a Canadian call to action, which is presented in this paper.

Methods

Part 1: Evidence synthesis

To understand what is currently known about the promotion of physical activity in non-urban settings from the perspective of physical, built and natural environments, we conducted a scoping review and synthesis of the literature at the review level. This “synopses of syntheses” is an approach recommended by the National Collaborating Centre on Methods and Tools (NCCMT) for assessing the state of evidence on public health interventions,14 with searches of the highest quality sources conducted. Our intent was to scope and summarize the evidence on a specific topic area, using the findings of systematic reviews— reviews of reviews—as our starting point.

Data collection

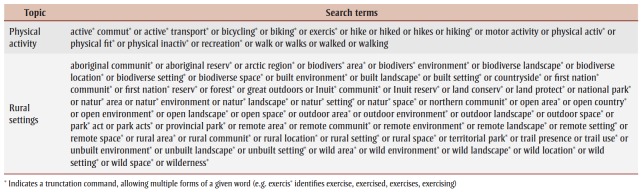

The synthesis involved retrieving review articles from four major databases (Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete and SPORTDiscus) and four grey literature sources (Active Living Research, Bridging the Gap/Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, Children and Nature Network and Ohio Leave No Child Inside Collaboratives). We also reviewed references cited in key articles and retrieved via Google Scholar and additional reviews identified by the research team. To facilitate inclusivity, a broad range of terms related to physical activity and the physical, built and natural environments in non-urban settings was used in different combinations, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Literature search strategy.

Inclusion criteria were reviews, including narrative reviews and summary papers, published after 2000, in English or French; articles on research, strategies and/or interventions related to physical activity in the context of the physical, built and natural environments; and findings and/ or implications relevant to non-urban settings, including rural, remote, northern and natural settings.

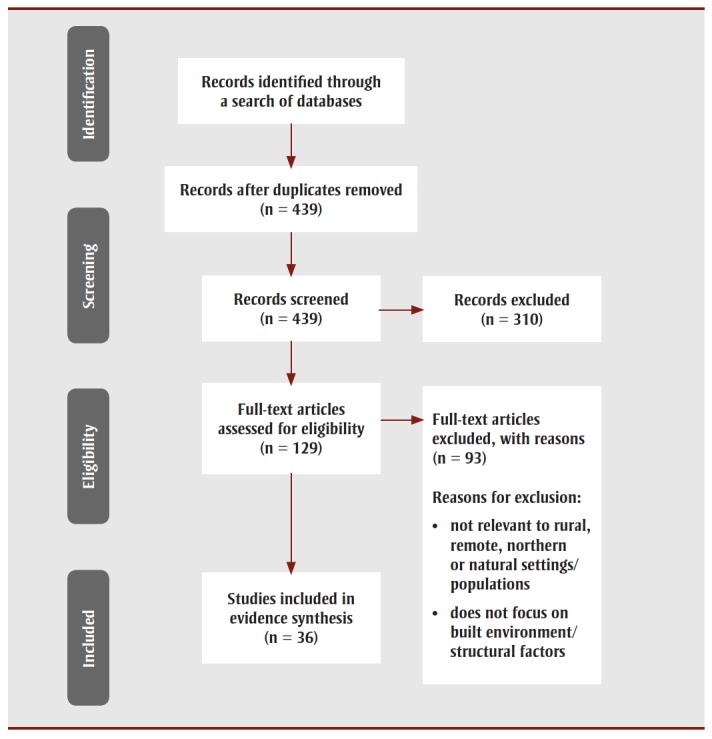

The articles were initially screened by title and abstract review to eliminate irrelevant articles. We then conducted a full review and relevance assessment, followed by data extraction. Figure 1 presents a modified (i.e. for scoping reviews) PRISMA flow diagram of records collected during the screening process.

Figure 1. Modified PRISMA Flow Diagram (for scoping review).

The search resulted in a total of 36 review articles that explored the promotion of physical activity in non-urban settings from the perspective of physical, built and natural environments. Of these, 13 focused explicitly on rural (n = 4), remote, northern or on reserve (n = 5) and natural (n = 4) settings. The remaining 24 review articles discussed findings and/or implications applicable to rural settings, even though this setting was not the primary focus of our review. Because of the limited number of directly relevant review articles retrieved in the literature search, we did not use data quality as an inclusion criterion.

Data analysis

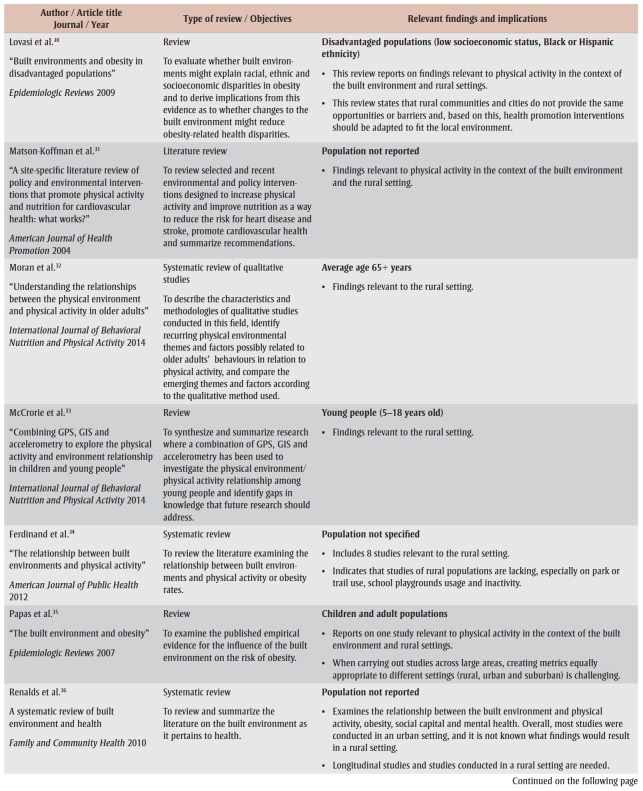

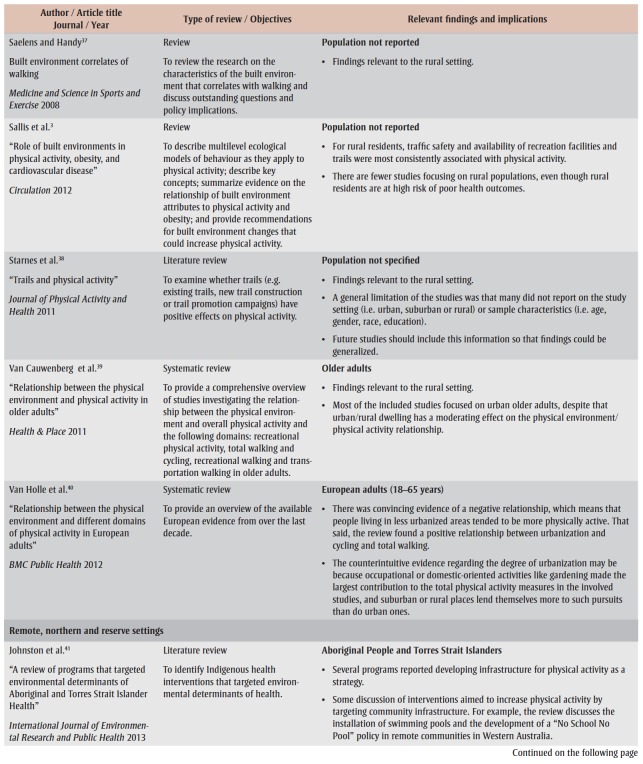

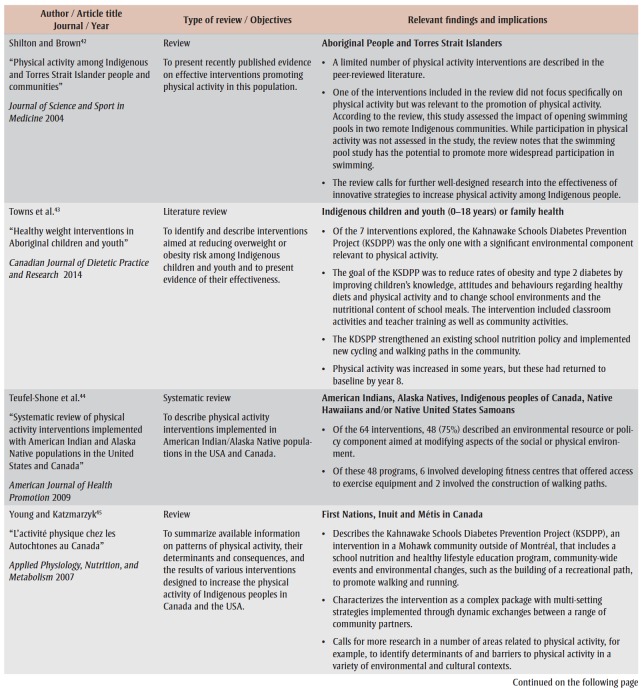

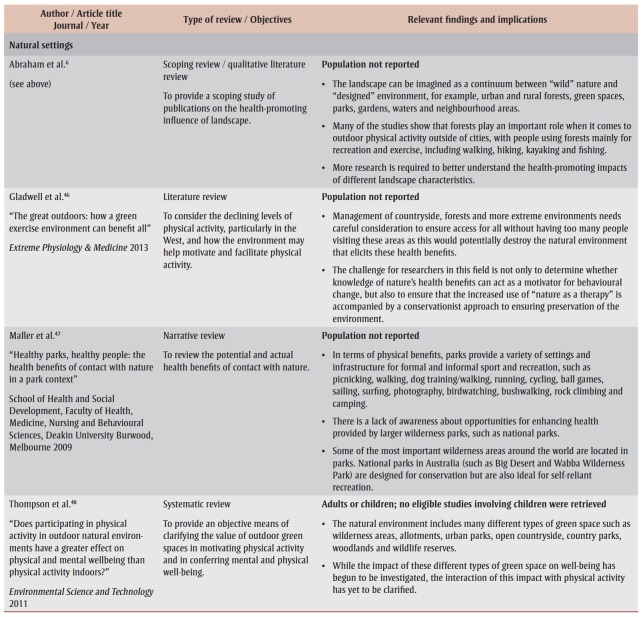

The data extraction and analysis process involved first charting the data and then collating, summarizing and reporting results, based on Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework.15 A summary of included review articles is presented in Table 2. Information from the review articles was themed according to setting type (rural; remote, northern or on reserve; and natural). Sub-themes within each setting type were identified in an emergent and iterative manner to comprehensively summarize results from the literature. To minimize any potential bias, two reviewers separately extracted and analyzed the data. Team meetings with the two principal investigators and the reviewers were held to discuss the analyses and to resolve any inconsistencies between reviewers.

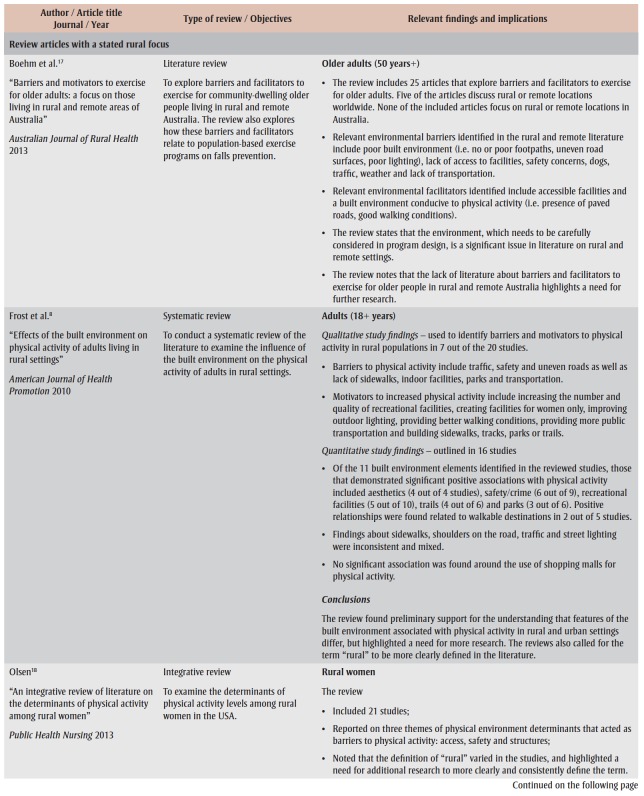

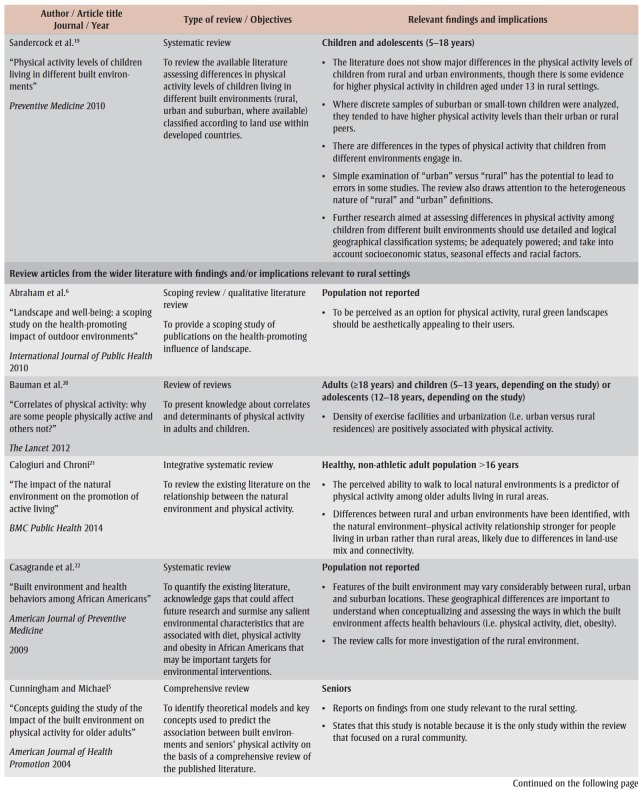

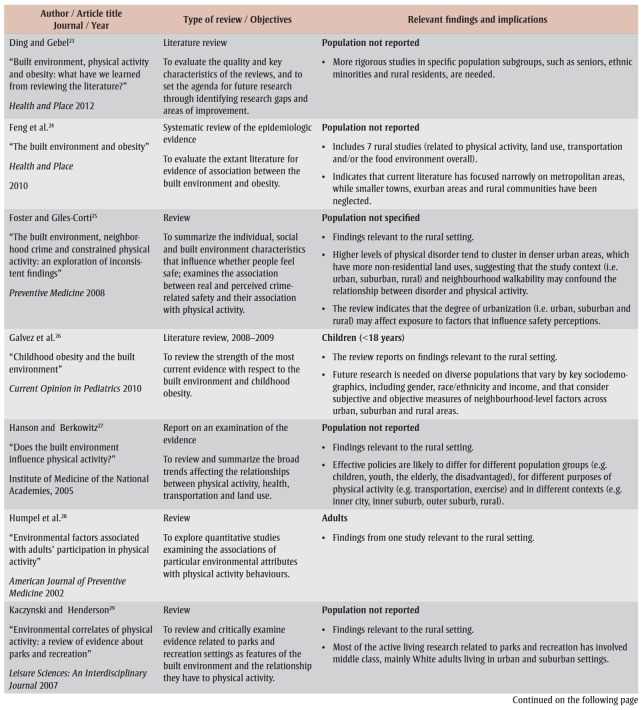

Table 2. Summary of included review articles.

Of the 36 review articles included in the synthesis, only four specifically focused on rural settings (see Table 2). So, as a secondary focus of our review, we assessed the 24 broader review articles that discussed findings and/or implications applicable to rural settings. We also identified five review articles that focused on Indigenous health and included findings pertinent to remote, northern and/or reserve settings. (Reserves are commonly situated in non-urban settings and experience obstacles related to lack of access to health resources and community infrastructure.16) Lastly, we identified four review articles that contained findings related to natural settings outside of urban areas (i.e. wilderness areas and natural parks). Those natural settings described as being situated within rural areas were included in the rural settings category.

Part 2: Priority-setting conference

To build on the findings of the review and develop a set of priorities for practice and policy action in Canada, and to set a course for applied research on physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities to support that practice and policy action, we held a one-day prioritysetting conference on physical activity in rural and remote/northern settings with 28 invited experts. These experts represented the spectrum of rural and/or remote/northern physical activity promotion- related research, policy and practice from across Canada. (Note: based on strong recommendations from the relevant experts, the remote and northern categories from the literature were combined for the conference.) Participants included an Indigenous elder as well as practitioners and senior decision-makers from the North and from across Canada; representatives from municipal and provincial public health agencies and municipal planning agencies; university or institutebased researchers; and experts from sport and recreation, community and medicine. The experts were identified through a search of the scientific and grey literature (e.g. policy documents and guidelines) on the topic and based on the recommendations of the Policy Advisory Group of the Policy Opportunity Windows – Engaging Research Uptake in Practice (POWER UP!) CLASP initiative, a panel of international experts on policy related to obesity and chronic disease prevention.

The scoping review results were provided to the participants in advance of the meeting so that they could review the evidence synthesis analysis and findings; critically reflect on how that body of literature could inform enhanced action on physical activity in rural, remote and northern Canadian communities; and identify what was missing from the evidence synthesis. An overview of the findings was presented to the participants on the day of the conference.

While the evidence synthesis broadly explored rural, remote, northern and natural settings, the priority-setting conference narrowed that focus to specifically address rural and remote/northern settings based on recommendations from invited participants, recognizing that natural settings would be addressed as part of both.

This study was approved by the Health Panel of the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta.

Data collection

The priority-setting conference used a collaborative three-phased process that encouraged participants to generate priorities for action based on the available evidence and their own policy or practicebased experiences. Detailed notes were taken throughout the process. In the morning, presentations delivered by five experts focused on current research evidence and practice or policy-based experiences in rural and northern/remote settings, including one presentation that summarized findings from the evidence synthesis, and to unravel the nuanced, contextual nature of the issue of physical activity in rural and remote/northern settings. Two small group discussions organized by setting (rural and remote/ northern) then took place simultaneously. In these discussions, the experts identified key priorities for the setting based on their own experiential knowledge and understanding of the research evidence, while also considering the information shared in the presentations and in the dynamic group discussions.

Data analysis

The analysis of priority-setting findings was collaborative. The participants reconvened as a large group to share their small-group priorities and to identify remaining issues. Then, working in new small groups, the experts selected their top three to five priorities for research, policy and practice. This provided them with another opportunity to share their perspective and expertise. To close the conference, the small groups came together to rank and finalize a set of priorities.

We then used this list of priorities alongside the evidence synthesis and consideration of relevant policy and practice documents to compile an initial Canadian call to action on the promotion of physical activity in rural, remote, and northern settings.

Results

Literature review

Rural settings

Review articles with a stated rural focus

We identified four review articles that focused explicitly on rural (or remote) settings8,17- 19 and that investigated the effects of the built environment on physical activity,8 determinants of physical activity,18 barriers and motivators to physical activity8,17 and differences in physical activity in rural, urban and suburban built environments.19 Demographic groups reported included children and adolescents,19 women,18 adults8 and older adults.17 Studies took place primarily in the United States of America (USA), as well as in Canada and Australia. One review incorporated studies from Cyprus, Iceland, Italy, Norway and Sweden.19

Defining rural

None of the four review articles provided explicit criteria on how they defined “rural.” For example, Frost et al. 8 reviewed studies that identified the population as “rural,” whereas Olsen et al.18 used a varied definition, noting that one study limited the sample to communities of fewer than 1000 persons with no towns within a certain radius, while another included towns with up to 49 999 residents.

Barriers and motivators

Three out of the four rural-focused review articles discussed findings related to environmental motivators and/or barriers in rural settings. Examples of identified barriers included lack of sidewalks,8,18 poor lighting/lack of streetlights,17,18 safety concerns (i.e. crime, presence of hunters),8,17,18 the weather,17,18 dogs or wild animals17,18and lack of physical access to facilities, transportation8,17,18 and parks.8 For example, Boehm et al.17 found that social and environmental barriers to exercise for older people—such as a poor built environment, presence of dogs and bad weather—were more common in rural and remote community settings. While additional research is necessary, the review articles suggest there is a need for (1) policy to address barriers to physical activity in terms of the built environment (i.e. transportation, safety), particularly in specific populations (e.g. rural women); (2) for environmental design to consider environmental motivators and barriers; and (3) for practitioners to explore strategies to overcome these barriers.8,17

Associations between physical activity and the built environment

In their review of 20 studies, Frost et al.8 identified 11 elements of rural built environments associated with physical activity levels in adults: sidewalks, street lighting, private and public recreational facilities, parks, malls, aesthetics, crime/safety, traffic, walking destinations, trails and access to the environment. To varying degrees, these studies explored the following elements: aesthetics (4/4 studies); perceptions of safety/crime levels (6/9); and presence of recreational facilities (5/10), trails (4/6) and parks (3/6). All these elements were found to be associated with physical activity levels.8 Frost et al. then compared findings from rural settings with those from 18 urban studies, and found that physical activity was positively associated with aesthetics in both settings, but that safety/crime levels, traffic and trails were better predictors of physical activity in rural settings.8 This evidence suggests that built environment features associated with adult physical activity may differ between rural and urban settings.

Differences in physical activity between rural, urban and suburban built environments

Of the four rural-focused review articles we included in our synthesis, Sandercock et al.19 had an explicit objective to compare differences in the physical activity levels of children living in urban and nonurban settings. Only 6 of the 18 studies Sandercock et al. reviewed explored physical activity beyond the rural/urban dichotomy and included suburban and/or small-town settings and/or populations. They found that physical activity levels of children in urban and, in some cases, rural settings were lower than those of children in suburban/small-town settings, a result (the authors suggest) of suburban and small towns sharing a mix of rural and urban characteristics. Suburban settings were also found to have fewer low socioeconomic households and ethnic minority residents, two characteristics negatively associated with physical activity in adults.19 Sandercock et al. recommended that future studies consider socioeconomic status, racial factors and seasonal effects relative to physical activity within different built environments.

Review articles from the wider physical activity literature, with relevant findings and/or implications for rural settings

It was a challenge to draw definitive conclusions from the diverse evidence base. Taken together, these 24 review articles reiterated the importance of understanding how geographical differences can influence relationships between the built environment and health-related behaviours, and recommended setting sensitive environmental interventions.

Remote, northern and reserve settings

We identified five review articles on Indigenous health that included findings relevant to remote, northern and/or reserve settings (we did not find any review articles relevant to remote or northern settings that did emphasize Indigenous health). Four of these review articles discussed interventions to promote physical activity, either alone, or as an aspect of obesity or set of health outcomes. The fifth review article discussed physical activity correlates and patterns among Indigenous peoples in Canada and the USA, and provided an overview of intervention studies.45 Studies included in the review articles took place in Australia,41,42the USA43-45 and Canada.43-45

Environmental interventions to promote physical activity in Indigenous communities

The five review articles on Indigenous health discussed different interventions aimed at promoting physical activity that included an environmental component. For example, of the seven interventions aimed at promoting healthy weights among Indigenous children and youth that Towns et al.43 identified, only two were multicomponent interventions involving an environmental or policy change. In contrast, Johnston et al.41 and Shilton and Brown42 reported on the building of swimming pools in two remote Indigenous communities in Western Australia, where the goal was to increase school attendance and improve primary health outcomes. The review articles suggested that interventions like these demonstrate the value of implementing comprehensive strategies to meet a range of community needs in resource-limited remote communities.

Teufel-Shone et al. 44 found that the majority of physical activity interventions in remote regions in Canada and the USA (72%) took place on reservations, reserves or pueblo. About 75% of the 64 interventions described an environmental resource or policy component aimed at modifying aspects of the social or physical environment. Effective interventions had an impact at various levels, including on risk behaviours and on health and fitness. Key factors for success included support from local leadership and the incorporation of cultural traditions into public health practice.

The review articles highlighted the need for more culturally relevant research that focuses on the histories of rural and remote Indigenous communities across a greater variety of geographical and cultural contexts.43-45 For example, the review articles revealed that barriers and opportunities for physical activity in Indigenous communities are not homogenous and that findings from one geographical region (e.g. country, province or community) or population (e.g. elders or children) may not readily apply to other regions or populations.

Natural settings

Four review articles that explore physical activity in natural settings (e.g. natural parks and wilderness areas) were identified. These review articles focused on a range of topics, including health benefits of contact with nature;47 landscape as a resource for well-being;6 physiological benefits of exercise in a green environment; 46 and effects of participation in physical activity in natural environments versus indoor settings.48 These review articles suggest there is a lack of awareness of the role that natural environments play in promoting physical activity and enhancing health,47 particularly when these settings are considered as a feature of rural, remote or northern communities. Yet, there is also growing evidence for the importance of connecting with nature for people’s health. For example, natural landscapes were found to have a greater restorative effect on mental fatigue and be better able to improve the ability to concentrate than urban areas.6 At the same time, there is concern about the sustainability of natural settings and the environmental impact of increased human presence,46 which suggests there is a need for intervention design for communities in natural areas.

Overall, across all non-urban settings, continued and enhanced efforts are required to synthesize and translate available evidence to inform the work of Canadian practitioners and policy makers. Furthermore, there is a need for additional primary research that uses scientifically robust methods to address current research gaps and limitations on this topic.

Priority-setting conference outcomes

The conference resulted in the identification of key priority areas for action and applied research to promote physical activity in rural and remote/northern communities. The key priorities represent the immediate and longer-term evidence needs and priorities of practitioners and academics working in these distinct settings.

Rural settings

Community self-identification of priorities and needs through collaborative processes with researchers.

Involve rural communities in identifying research and policy priorities that promote physical activity in these settings to ensure that outcomes are meaningful and actionable for researchers, practitioners and policy makers.

Increase funding opportunities that create spaces for collaboration between community members, practitioners, researchers and policy makers.

Take inventory (of what is already happening) and develop a database of best practices to support moving knowledge to action.

Develop a national virtual infrastructure to house best practices from across Canada.

Work with communities, researchers, practitioners and policy makers to identify gaps and promising practices.

Simultaneously understand, act and continually move forward on what is already known about promoting physical activity in rural settings despite the limited, if emerging, evidence base.

Capture context in rural settings through qualitative and descriptive research.

Promote the use of focused qualitative and descriptively rich research to develop policies and programs that are relevant to the specific contexts of communities, given the heterogeneous nature of rural communities.

Use qualitative and descriptive research to unravel the specific nuances of different rural contexts. These findings can subsequently be compared and contrasted across different settings to help address some of the extant challenges in defining “rural” in Canada.

Remote/northern settings

Look at physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities through a holistic lens (e.g. as an integral part of daily life).

Assist practitioners and policy makers in identifying a broader range of opportunities to showcase the value of physical activity.

Integrate physical activity with other community initiatives (e.g. when promoting mental wellness).

Develop culturally appropriate programs, for example, focusing on the connection between land and food; the role of physical activity in healing, resilience and well-being; and the pre-eminent focus on wellness as a starting place would be a way of promoting Indigenous leadership for culturally-relevant physical activity opportunities.

Create more opportunities for leadership, mentorship and resource development.

Support community members, including youth, who are promoting physical activity in their communities to enhance long-term sustainability.

Identify a broader pool of community members—youth, community ambassadors and recreation leaders, among others—to support physical activity initiatives.

Identify existing training opportunities that support physical activity (e.g. the Certificate in Aboriginal Sport and Recreation* at the University of Alberta trains people within their own communities to develop expertise).

Carefully consider how capacity building is defined; who decides what capacity is needed; who the trainers are; and who needs support.

Compile experiences in a database

Develop and share an inventory of the different programs, activities and policies across Canada that promote physical activity in remote/northern settings.

Incorporate local knowledge and community voice to ensure that culturally relevant activities are captured as part of documentation and sharing processes.

Ensure resources are readily available and shared in a variety of ways (different languages, formats, e.g. video as well as text) to enhance reach to multiple cultural and geographical contexts.

https://www.ualberta.ca/kinesiology-sport-recreation/programs/undergraduate-programs/certificates/certificate-in-aboriginal-sport-and-recreation.

Discussion

Expert participants at the priority-setting conference saw the need to move beyond the limited guidance currently available through extant research on physical activity in rural and remote settings to make meaningful, equitable and timely progress on physical activity promotion in those settings. In addition to careful consideration and discussion of the evidence, the experts drew on their rich and deep experience of working in these settings as practitioners, decision makers and researchers. Thus, while building from the evidence synthesis, the call to action described above reports on expert recommendations that recognize the nuance, variation, process and contextual issues that transcend the evidence currently available in the literature.

While the evidence synthesis and prioritysetting process revealed similar issues and priorities in rural, remote and northern settings, the experts drew on their knowledge of the issues to clarify and expound on the implications for physical activity research and practice in these settings. Future research must address the problematic lack of clarity, transparency and consistency in how the term “rural” is defined and conceptualized.8,18,19 The lack of definition and conceptualization may limit the usefulness of the evidence and thus have a detrimental impact on the applicability of the findings for other rural settings.8,17 This lack of transparency and consistency compromised the utility of the findings from the review articles and led conference participants to deliberate on why it is complicated to define “rural.” For example, noting that rural areas can vary greatly, Statistics Canada defines rural areas as “small towns, villages and other populated places with less than 1000 population according to the current census” and can include “agricultural lands” and “remote and wilderness areas.”49 Currently, Statistics Canada’s definition has not been uniformly adopted by provincial/ territorial health authorities or other governmental or organizational bodies concerned with rural or remote settings as other definitions may better align with particular service mandates or jurisdictional authority. While “rural” is a heterogeneous construct, further complications to the notion of a single definition are the similarities in the experience of rurality, despite wide differences in populationbased or geographic characteristics often assigned to definitions of rural. A clear, consistent and transparent definition of “rural” would facilitate effective knowledge sharing across settings. The experts participating recommended the use of rigorous qualitative and mixed-method approaches as a starting point to unravelling this complexity.

The review articles noted the lack of peerreviewed articles focusing on interventions targeting broader environmental levels for remote and northern settings.41,43While setting priorities, experts echoed this concern and called for more resources dedicated to systematically promoting physical activity in these settings. Participants acknowledged the wealth of existing practice and policy under way (that is not adequately represented in current academic literature) and emphasized the need to increase investment in long-term sustainable funding and develop innovative funding models to reinvest in promoting physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities (i.e. which is also emphasized in the ParticipACTION Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth50,51); and document and share success stories and best practices in a more systematic way, including a focus on grey literature.

Experts described how this investment is particularly important in Indigenous rural or remote/northern communities to address the inequity of resources that promote physical activity52 and to systematically measure and reveal how those resource inequities are related to poor health and social outcomes. Further, efforts to document the wide range of sources of evidence related to physical activity in rural and remote settings should be governed by rigorous, transparent and culturally appropriate criteria, including Indigenous research methods that are led by the communities themselves.

Expert participants from both rural and remote/northern settings groups identified similar best processes when bridging research, practice and policy gaps, suggesting that local community members, practitioners and decision-makers be actively involved in identifying issues and developing and implementing solutions. While this was not a theme identified in the evidence synthesis, it is reflected in both the State of Rural Canada 2015 report13 and the 2016 Pathways to Policy report,53 confirming the experts’ rich process recommendations. Participants also raised the notion of community capacity to support physical activity in rural and remote/northern settings—an idea that echoes ParticipACTION’s 2016 report card.50 For example, they cited leadership development with youth and other community leaders in remote/northern communities as a key process to support long-term sustainability.

Expert participants carefully acknowledged the unique differences between rural and remote/northern settings. For example, experts from remote/northern settings emphasized the holistic nature of promoting physical activity, noting that action should reflect community culture and be integrated with core community priorities and Indigenous leadership. Experts stressed the importance of taking a strengths-based perspective and focusing on moving-to-the-land and on-theland programs that involve traditional activities (e.g. hunting, snowshoeing) which embody physical activity and built environment concepts in ways that are relevant to the community. Priority-setting participants proposed focusing on resiliency- based programs (e.g. a return to connecting culture, the land and medicine) as one approach for moving forward.

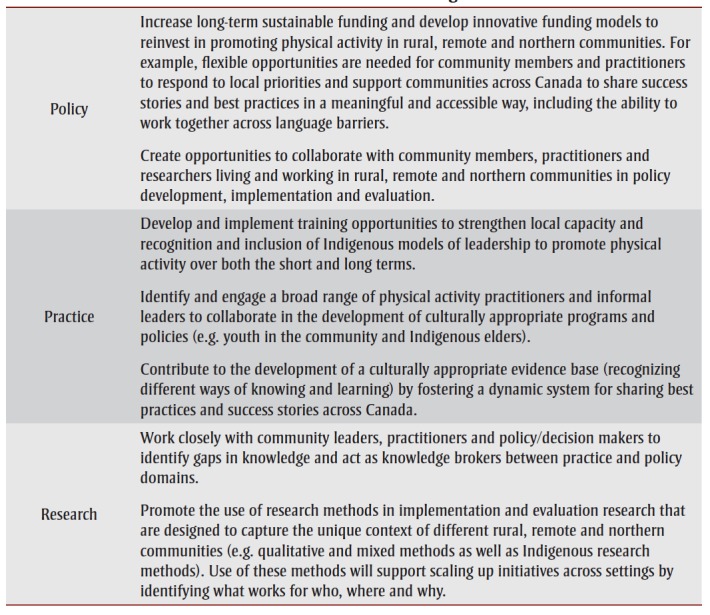

Call to action

We present the following Canadian call to action, which outlines a focused direction to support the implementation and success of population-level and environmental initiatives targeting physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities (Table 3). This call to action emerged from the priority-setting meeting, which was informed by both the evidence synthesis and the experts’ critical reflection—one that is based on their current policy and practice expertise. This call to action, which is intentionally coordinated across policy, practice and research domains, also reflects recommendations from the National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health52 to promote cultural relevancy and anti-oppressive practices as they relate to communication, knowledge generation and leadership.

Table 3. Canadian call to action on the promotion of physical activity in rural, remote and northern settings.

|

To support timely knowledge translation with practitioners and policy makers, an earlier version of the evidence synthesis and the outcomes of the priority-setting conference were posted on the public website of the Alberta Policy Coalition for Chronic Disease Prevention, a partner in a funded project on policy interventions to address obesity and chronic diseases.

Strengths and limitations

There are potential limitations to this analysis. First, categorizing review articles by type of setting proved to be challenging because the terms used—“rural and remote,” “rural” and “reserve”—were often conflated in the literature, despite having different operational meanings. Similarly, Canadian priority-setting participants used the terms “remote” and “northern” synonymously in their deliberations, yet these terms are used differently in the international literature dealing with rural and remote health. Second, the review process did not account for data quality as an inclusion criterion [i.e. to offset the limited number of review articles available; as well, while 13 directly related to non-urban settings (rural, remote, northern and natural), 24 were not directly related to these settings but mentioned rural or remote communities in their recommendations]. Thus, some included review articles may be of poor quality. Third, as this synthesis reported on evidence explicitly outlined within the review articles, relevant information reported at the study level might not have been captured.

The strength of this initiative lies in its integrated knowledge translation approach: we deliberately brought scholarly evidence together with experiential evidence from practice and policy to shed light on this critical health equity issue. Synthesis findings were contextualized and enhanced by experts’ knowledge to support future research and action on physical activity in non-urban settings. We recognize and are currently acting on the need to continue to engage stakeholders with additional perspectives to be part of future discussions and strategic planning on facilitating physical activity in rural, remote and northern settings.

To this end, we will be hosting a follow-up priority-setting conference to make headway on this new Canadian call to action. The meeting will convene a wider group of researchers, practitioners and policy makers working in the area of physical activity in rural, remote and northern settings to critically analyze this call to action; highlight examples of current practices and new gaps for each type of setting addressed in the call to action; and form working groups to begin addressing the specific actions noted in the call.

The need for anti-oppressive practices in the development and sharing of knowledge for the benefit of non-urban population groups, particularly Indigenous groups, will also be addressed at this meeting. Specifically, we will seek leadership and guidance from Indigenous community leaders (or members), local practitioners and experts in developing and hosting the event so as to not reproduce Canada’s colonial legacy.

Conclusion

Access to supportive settings for physical activity is critical for promoting health and well-being. The lack of policy, practice and research action on physical activity and features of the physical, built and natural environments in rural, remote and northern settings is a significant threat to population health equity in Canada. To begin to address this challenge, we brought together experts from the research, policy and practice domains to develop a Canadian call to action based on a synthesis of evidence reviews that focused on physical activity promotion in rural, remote or northern communities. The call to action outlines a focused direction to support the implementation and success of population-level and environmental initiatives targeting physical activity in rural, remote and northern communities. Coordinated action across policy, practice and research domains will be essential to the success of these recommendations.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Health Canada through the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer’s (CPAC) Coalitions Linking Action & Science for Prevention (CLASP) initiative. The authors respectfully acknowledge the Association pour la Santé Publique du Québec for their valuable insights and help with the priority-setting meeting. We also thank the anonymous peer reviewers and editors who provided careful feedback to help us strengthen the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors except KK participated in the priority setting meeting. CN led the design and analysis of the review of reviews, chaired the priority setting meeting, drafted recommendations, and contributed to drafting and finalizing the manuscript; KA conducted the review of reviews, drafted recommendations, and contributed to drafting and finalizing the manuscript; KR contributed to drafting the recommendations and finalizing the manuscript; KK drafted the manuscript; and SB, WC, TG, JG, and JM presented evidence at priority setting meeting and contributed to drafting and finalizing the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- The Toronto charter for physical activity: a global call for action. J Phys Act Health. 2010 doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Health Measures Survey: Directly measured physical activity of Canadians, 2012 and 2013. Statistics Canada. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/150218/dq150218c-eng.pdf? [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Floyd MF, Rodriguez DA, Saelens BE, et al. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.969022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Lawson CT, et al. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham GO, Michael YL, et al. Concepts guiding the study of the impact of the built environment on physical activity for older adults: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot. 2004 doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.6.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham A, Sommerhalder K, Abel T, et al. Landscape and well-being: a scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int J Public Health. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2016 Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Survey. Policy Opportunity Windows Enhancing Research Uptake in Practice [POWER UP!], Coalition Linking Action and Science for Prevention [CLASP] 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Frost SS, Goins RT, Hunter RH, et al, et al. Effects of the built environment on physical activity of adults living in rural settings. Am J Health Promot. 2010 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.08040532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Kirkner GJ, Mayo K, Matthews CE, Durstine JL, Hebert JR, et al. Urban, rural, and regional variations in physical activity. J Rural Health. 2005 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER, et al. The impor¬tance of place of residence: exami¬ning health in rural and nonrural areas. Am J Public Health. 2004 doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2010-2011 Physical Activity Monitor. Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. :Barriers to children’s participation in physical activity Ottawa [ON]: Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute–2014 [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.cflri.ca/sites/default/files/node/1334/files/CFLRI%20PAM%202010-2011%20Bulletin%2014%20EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cities and communities: partners in Canada’s future Ottawa, Canada: Federation of Canadian Municipalities; 2015 [cited 2017 Nov 17] Federation of Canadian Municipalities. Available from: https://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/FCM/Cities_and_Communities_Partners_in_Canada_Future_EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Markey S, Breen S, Lauzon A, Gibson R, Ryser L, Mealy R, et al. State of rural Canada 2015. Markey S, Breen S, Lauzon A, Gibson R, Ryser L, Mealy R, editors. Available from: http://sorc.crrf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/SORC2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-informed public health: What is Evidence- Informed Public Health. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Available from: http://www.nccmt.ca/professional-development/eiph. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L, et al. Scoping stu¬dies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Reading C, Wien F, et al. Health inequali¬ties and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. Reading C, Wien F. Available from: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-HealthInequalities-Reading-Wien-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm J, Franklin RC, Newitt R, McFarlane K, Grant T, Kurkowski B, et al. Barriers and motivators to exercise for older adults: a focus on those living in rural and remote areas of Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ajr.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JM, et al. An integrative review of literature on the determinants of phy¬sical activity among rural women. Public Health Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1111/phn.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock G, Angus C, Barton J, et al. Physical activity levels of children living in different built environments. Prev Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW, et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogiuri G, Chroni S, et al. The impact of the natural environment on the pro¬motion of active living: an integrative systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014:873–2014 [cited 2017 Nov 17]. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Whitt-Glover MC, Lancaster KJ, Odoms-Young AM, Gary TL, et al. Built environment and health behaviors among African Americans: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Gebel K, et al. Built environment, physical activity, and obesity: what have we learned from reviewing the literature. Health Place. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS, et al. The built environ¬ment and obesity: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Giles-Corti B, et al. The built envi¬ronment, neighborhood crime and constrained physical activity: an exploration of inconsistent findings. Prev Med. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez MP, Pearl M, Yen IH, et al. Childhood obesity and the built environment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010 doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328336eb6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson S, Berkowitz B, et al. Does the built environment influence physical acti¬vity. Hanson S, Berkowitz B. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E, et al. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical acti¬vity: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski AT, Henderson KA, et al. Environmental correlates of physical activity: a review of evidence about parks and recreation. Leisure Sci. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM, et al. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged popula¬tions. Epidemiol Rev. 2009:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Neiner JA, Greaney ML, et al. A site-specific literature review of policy and envi¬ronmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for car¬diovascular health: what works. Am J Health Promot. 2005 doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M, Cauwenberg J, Linnewiel R, Cerin E, Deforche B, Plaut P, et al. Understanding the rela¬tionships between the physical envi¬ronment and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review of qualita¬tive studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014:79–20. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrorie PR, Fenton C, Ellaway A, et al. Combining GPS, GIS, and accelero¬metry to explore the physical activity and environment relationship in children and young people – a review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014:93–20. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand A, Sen B, Rahurkar S, Engler S, Menachemi N, et al. The rela¬tionship between built environments and physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC, et al. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007:129–43. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renalds A, Smith TH, Hale PJ, et al. A sys¬tematic review of built environment and health. Fam Community Health. 2010 doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181c4e2e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Handy SL, et al. Built environ¬ment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starnes HA, Troped PJ, Klenosky DB, Doehring AM, et al. Trails and physical activity: a review. J Phys Act Health. 2011 doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.8.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauwenberg J, Bourdeaudhuij I, Meester F, et al, et al. Relationship between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Health Place. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holle V, Deforche B, Cauwenberg J, et al, et al. Relationship between the physical environment and different domains of physical activity in European adults: a syste¬matic review. BMC Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, Doyle J, Morgan B, et al, et al. A review of programs that targeted environmental determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.3390/ijerph10083518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilton TR, Brown WJ, et al. Physical acti¬vity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communi¬ties. J Sci Med Sport. 2004 doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towns C, Cooke M, Rysdale L, Wilk P, et al. Healthy weights interventions in Aboriginal children and youth: a review of the literature. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2014 doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2014-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel-Shone NI, Fitzgerald C, Shone L, Gamber M, et al. Systematic review of physical activity interven¬tions implemented with American Indian and Alaska Native populations in the United States and Canada. Am J Health Promot. 2009 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07053151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young TK, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. L’activité physique chez les Autochtones au Canada. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007 doi: 10.1139/H07-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell VF, Brown DK, Wood C, Sandercock GR, Barton JL, et al. The great outdoors: how a green exercise envi¬ronment can benefit all. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013 doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller C, Townsend M, Brown P, Leger L, et al. Healthy parks, healthy people: the health benefits of contact with nature in a park context. George Wright Forum. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH, et al. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical acti¬vity indoors. Environ Sci Technol. 2011 doi: 10.1021/es102947t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dictionary, Census of Population, 2016. Statistics Canada. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/dict/geo042-eng.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Are Canadian kids too tired to move. ParticipACTION. Available from: https://www.participaction.com/sites/default/files/downloads/2016%20ParticipACTION%20Report%20Card%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Are we driving our kids to unhealthy habits. Active Healthy Kids Canada. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110606009. Available from: http://dvqdas9jty7g6.cloudfront.net/reportcard2013/Active-Healthy-Kids-2013-Report-Card_en.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S, et al. Review of core competencies for public health: An Aboriginal public health perspective. Hunt S. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Available from: https://content.cancerview.ca/download/cv/prevention_and_screening/prevention/clasp/documents/pathwaystopolicypdf. [Google Scholar]