Abstract

Introduction:

Pregnancy and the birth of a child present particular challenges for adults with personal histories of childhood abuse or neglect. However, few prenatal interventions address the specific needs of this population. This research aims to determine a list of actions that should be achieved during group interventions designed for expectant parents who experienced childhood trauma.

Methods:

Fifteen stakeholders representing nine different Quebec health care and community organizations that work with families and/or trauma survivors participated in a Delphi process in two rounds. In round 1, three project leaders identified, from clinical and empirical literature, a set of 36 actions relevant for expectant parents who experienced childhood trauma. Using an anonymized online survey, stakeholders coded how important they considered each action and whether they were already conducting similar interventions in their clinical setting. Stakeholders subsequently participated in a one-day in-person meeting during which they discussed the pertinence of each action, proposed new ones and refined them. This was followed by a second anonymized online survey (round 2). A consensus was reached among the stakeholders regarding a final list of 22 actions.

Results:

Two central clusters of actions emerged from the consultation process: actions aiming to support mentalization about self and parenthood, and actions aiming to support mentalization of trauma.

Conclusion:

The Delphi process helped to identify what should be the core of a prenatal intervention targeting adults who experienced childhood trauma, from the viewpoint of professionals who will ultimately deliver such a program.

Keywords: adult survivors of child adverse events, child maltreatment, parenting, intervention, mentalization, Delphi process

Highlights

Childhood abuse or neglect have long-term impacts that persist throughout adulthood and negatively affect the transition to parenthood.

Few interventions are designed for the numerous adults with histories of childhood abuse and neglect who are expecting.

Such interventions are of great importance for public health because they could promote the physical and mental health of adults with personal histories of childhood trauma, promote the psychosocial development of their child, and interrupt intergenerational cycles of abuse.

Stakeholders targeted to offer such a program consider that its primary focus should be to support mentalization of self and parenthood and mentalization of trauma.

Introduction

Pregnancy and the year following childbirth is a critical transitional period—a time of risk and opportunities. The level of adaptation that pregnancy and the birth of a child requires makes this one of the most critical periods for a woman’s mental health.1 Such an important life transition is a challenge even for adults with no apparent biological, psychological, marital or socioeconomic vulnerabilities. The challenge associated with pregnancy or birth may be even more intense for adults who experienced adverse life events, such as childhood abuse or neglect.

There is extensive evidence confirming that childhood abuse and neglect have mental2,3 and physical health4,5 consequences that persist into adulthood. Disorders in adults associated with childhood trauma include major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder, obesity, arthritis, high blood pressure, migraine headaches, cancer and strokes. Pregnancy and the birth of a child may trigger or intensify these latent or apparent disorders.6

Pregnant women with personal histories of childhood trauma are at increased risk of significant challenges, pain and distress. They are also at increased risk of having limited access to personal and social protective factors. Expecting a child may resurrect unresolved attachment trauma;7 such non-mentalized trauma (i.e. trauma that are denied, reported incoherently or for which the victim takes the blame) have been associated with negative feelings towards the baby and motherhood, and difficulties in intimate relationships.8 Women who experienced childhood trauma report common complaints of pregnancy significantly more often 9 and are more likely to have a highrisk pregnancy.10,11 In addition, they are more at risk of intimate partner violence than pregnant women who have not experienced childhood trauma.12,13 They are also at greater risk of trauma-related symptoms, such as dissociation and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,14 as well as symptoms not specific to trauma, such as anxiety and depression.15,16

The strategies often used to regulate intense negative emotions in adults with a history of trauma (e.g. dissociation, avoidance, psychoactive medication, alcohol or drug use/abuse) may actually interfere with parenting or affect the fetus and eventually the child. Women who experienced maltreatment in childhood are more inclined to be isolated during pregnancy17and in the years following childbirth,18 and to report low satisfaction with the social support they receive.19

Although the literature on expectant fathers who experienced childhood trauma is scant, we can assume they have similar challenges given that 10% of men in the general population experience significant psychological distress after the birth of a child.20 Moreover, childhood maltreatment is associated with important long-term consequences in men as well as women.21

Risk trajectories associated with early experiences of abuse and neglect may be transmitted from one generation to the next. For instance, early in their development, the majority of children born to a mother with a personal history of abuse or neglect develop insecure attachment strategies (82% vs 38% of the general population) and as many as 44% (vs 15% of the general population) display disorganized/ disoriented attachment.22 Disorganized attachment is a significant precursor of social, intellectual, cognitive, affective and behavioural difficulties.23,24 Children of mothers with personal histories of trauma are also at greater risk of presenting with developmental problems such as biological anomalies in the physiological regulation of stress25-27, neurodevelopmental disorders10 and emotional and behavioural problems.18,28-30 In addition, empirical evidence supports the notion of intergenerational cycles of childhood maltreatment.31-33

Given the high prevalence (32%) of reported child maltreatment in Canada,21 a significant number of expectant parents have a personal history of abuse or neglect. Considering (1) the multiple challenges expectant parents encounter during the transition to parenthood; (2) the empirical evidence for the intergenerational transmission of risk following childhood trauma; and (3) the fact that intervening soon after birth may already be late as some intergenerational impacts of parental trauma can be identified immediately after birth25, there is a definite need for prenatal interventions specifically designed for this population. Such interventions should aim to promote the physical and mental health of expectant parents who experienced childhood trauma; promote the psychosocial development of their child; and interrupt intergenerational cycles of abuse and neglect.

Different programs are offered worldwide to support parents considered at “highrisk”: the Nurse–Family Partnership,34 Circle of Security,35 Early Start36 or Minding the Baby.37 The program with the strongest evidence for preventing childhood maltreatment is the Nurse–Family Partnership.38 All of these programs generally include home visitations and mainly target adults who have difficulties responding to infant needs or who present general risk factors (e.g. adolescent motherhood, poverty, drug use). However, they are not specifically designed to address the particular challenges associated with the experience of childhood trauma or do not evaluate their effects in parents with histories of abuse or neglect.39

Conceptualizing specific interventions for this population may be important, as the way adults with histories of abuse or neglect view their experiences plays a distinctive role in their adaptation to parenthood and in the attachment relationship they develop with their child.8,22 A recent literature review confirmed that there are currently very few perinatal interventions for parents with histories of trauma and that no intervention was evaluated with fathers.39 Many of the programs listed above are designed to intervene primarily during the postnatal period. Only two programs specifically designed for adults with histories of trauma are delivered primarily during pregnancy: Survivor Moms Companion, a self-help manual,40 and the Perinatal Child–Parent Psychotherapy,41 which involves one-on-one psychotherapy. Prenatal interventions are required for different reasons. First, parents are psychologically and physically more available during this period than after the birth of the child. It has been suggested that pregnancy invariably activates internalized attachment representations,42 making pregnancy an ideal time for clinical approaches that aim to rework internalized object relationships.43 From a practical stance, parents may be unavailable to participate in interventions after the child’s birth, when obligations and responsibilities are numerous. Overall, perinatal interventions for parents who experienced interpersonal traumas in childhood were safe and acceptable to parents, but further research is required.

Sensitive parenting may require that someone has previously been sensitive to the parent’s own history and psychological conflicts. Based on this reasoning, prenatal interventions offer the opportunity to sensitively accompany the person in the development of their identity as a parent, while the focus of postnatal interventions can be placed on the child and the parent–child relationship. As well, intervening in the postnatal period, however early, may be considered more therapeutic than preventive as intergenerational impacts of childhood maltreatment are observed immediately after the child’s birth25 and important problems in the mother–child attachment relationship may already be in place at the time of consultation.22 Prenatal interventions would complement existing postnatal programs in preventing the emergence of difficulties in the parent– child relationship and may help interrupt the intergenerational transmission of risk associated with childhood maltreatment.

Considering the lack of prenatal interventions for adults with personal histories of childhood maltreatment, the aim of the present study was to consult health care providers and community organizations about the actions that should be taken during a prenatal group intervention designed to help expectant parents who experienced childhood trauma.

Methods

Delphi consensus development method

The Delphi consensus development method was used to identify important actions that should be accomplished during a prenatal group intervention for expectant parents who experienced childhood abuse or neglect. The Delphi method is widely used by health care professionals to determine sets of priorities in relation to health practice and research,44,45 and it has been previously used to establish guidelines on how to support people with personal histories of trauma.46

The goal of the Delphi method is to reach a consensus among a panel of experts on a specific domain. Consensus is reached using a series of questionnaires that experts complete in two or more rounds. After each round, the results are summarized and the experts are invited to discuss their responses. A revised questionnaire is then presented and the participants are encouraged to re-evaluate their earlier answers in light of the discussions. This process eventually leads to a decrease in the variance in experts’ ratings of priorities in a domain and the achievement of a consensus about a certain number of priorities.

Supporting the transition to and engagement in parenthood (STEP)

STEP is a clinical research program carried out at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières and funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The aim is to design, deliver and evaluate an innovative group accompaniment program for expectant parents who experienced interpersonal trauma in childhood. Ultimately, the aim of the program is to (1) promote the physical and mental health of adults with histories of childhood trauma who are transitioning to parenthood; (2) promote the psychosocial development of the program participants’ children; and (3) interrupt intergenerational cycles of abuse.

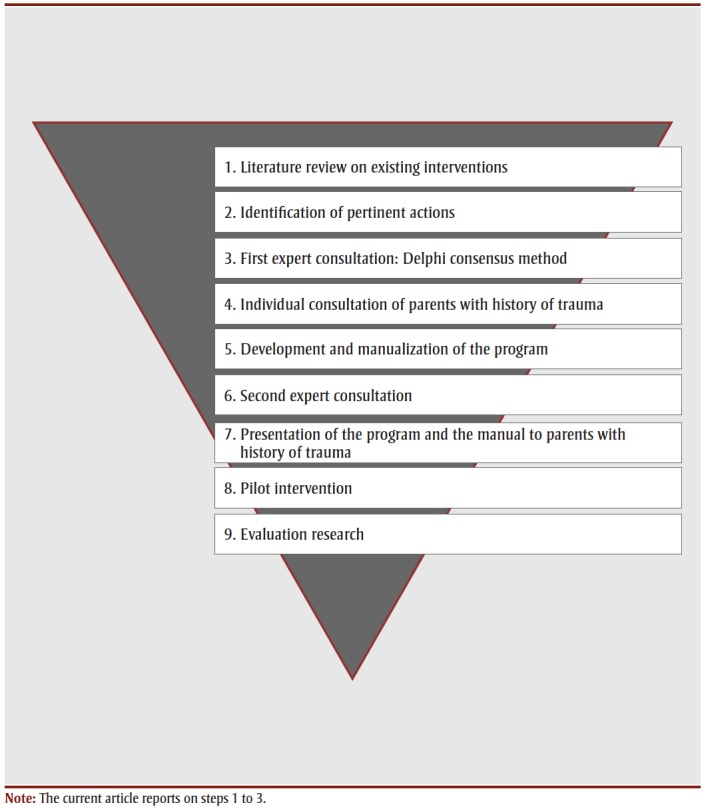

The present study reports on the first steps of the program’s development (see Figure 1). The program is designed for adults with histories of abuse or neglect who either do or do not present with or currently experience psychosocial difficulties. The program aims to complement existing interventions and services for expectant parents and promote participation of parents with histories of childhood trauma in such services.

Figure 1. Framework of the development and evaluation of the STEP accompaniment program.

Participants

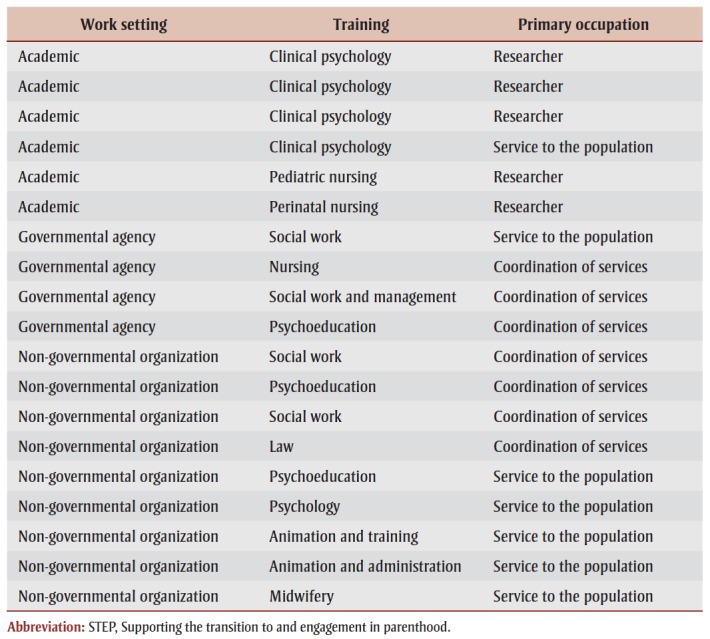

The research was initiated by three project leaders who are clinical psychologists and researchers in the fields of mental health, child development and parenting. The research also involved 18 partners from 10 independent organizations that offer services to expectant parents, families and/or other adults who experienced childhood trauma. Three of these 18 stakeholders identified themselves as more or less qualified to complete the Delphi consensus development process, but one had to withdraw to take maternity leave. Fifteen professionals from nine organizations participated in the first round of consultations, 15 in the in-person discussions and 14 in the final round of consultations. All participants were francophone and worked in Quebec. Stakeholders were selected by the project leaders for their expertise in childhood trauma; childhood sexual abuse; parental neglect; intimate partner violence; pregnancy, childbirth and delivery; parenting in the context of vulnerabilities; parent– child relationships; fatherhood; prevention of child abuse and neglect; child protection; Indigenous communities; individual psychotherapy with survivors of trauma; group intervention; health care management; community services; health care; and program evaluation. Table 1 provides more information on the participants.

Table 1. Participants in the STEP program development Delphi consensus.

|

Procedure

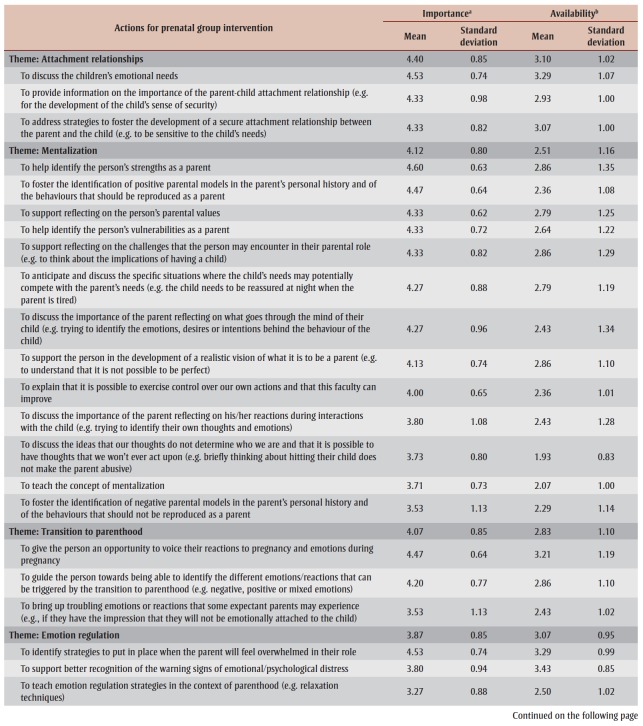

After reviewing clinical and empirical literature on parenting interventions and interventions with parents and victims of trauma, the three project leaders first identified a preliminary list of actions to accomplish during a prenatal group intervention with adults with personal histories of childhood trauma. The selected actions had to be particularly pertinent to adults with histories of interpersonal trauma, and sufficiently appropriate and safe to be conducted during pregnancy. Following the team discussions, the project leaders identified six core themes that they determined to be important for expectant parents who are trauma survivors: attachment; mentalization (the ability to think of behaviours in terms of underlying mental states such as emotions, motivations or beliefs); transition to parenthood; emotion regulation; trauma; and social support. A starting list of 36 potential actions covering these core themes was proposed. The preliminary list of actions is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Preliminary list of actions for prenatal group intervention prior to Delphi consensus development.

The participants in the consultation process were first requested to rate in terms of importance the proposed actions using an anonymized online survey. A five-point Likert scale was used (1 = not important; 2 = somewhat important; 3 = important; 4 = very important; 5 = essential). Participants were also asked to propose additional actions and to identify the extent to which each action was being accomplished in their clinical setting using a five-point Likert scale (1 = different from existing services; 2 = slightly different from existing services; 3 = I don’t know if such an action is offered in my clinical setting; 4 = similar to existing services; 5 = identical to existing services).

This first round of the consultation process was followed by a one-day in-person meeting during which the results of the first round were presented and each action was discussed. Participants were invited to comment on their responses, to discuss the feasibility of these interventions and to identify the extent to which they replicate services already available to expectant parents in the participants’ own clinical practices. The discussions were recorded and used to refine the actions and to prepare a final list. One week after the meeting, participants received the revised list through a second online survey and were requested to code for a second time the importance they attributed to each action.

Ethical approval for the study was given by the Comité d’éthique de la recherche avec des êtres humains de l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (CER15-226-10.04) and the Comité d’éthique de la recherche du Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de la Mauricie-et-du- Centre-du-Québec (CER2016-016-00).

Results

Round 1 (online survey)

A total of 15 stakeholders completed the first round of consultations. The results are presented in Table 2. Overall, each dimension was considered important. Top-ranked themes for discussion included attachment relationships, followed by social support, mentalization, trauma, transition to parenthood and emotional regulation. All actions obtained an average score of over 3, indicating their importance in the context of working with expectant parents who experienced trauma in childhood. While the themes of attachment relationships and social support were rated by the experts as the most important, they were also more likely to be offered in existing services compared with those actions that aim to help people process the trauma and improve mentalization, which appear more innovative.

In-person meeting

Fifteen participants attended the one-day discussion meeting. The relevance, feasibility and implementation of each action were discussed to refine them. Overall, the group agreed on some general considerations. One of those considerations was that all actions that implied a passive role in participants (teaching, informing, etc.) had to be redefined in order to involve participants actively in the intervention and to make sure that the professionals delivering the program do not present themselves as experts with solutions that have to be implemented by the parents. In other words, rather than providing information or teaching skills, the intervention should aim to support participants’ sense

of competence and personal agency. Another consideration was that the actions should not try to identify deficiencies, but rather should be formulated as opportunities for self-development for all expectant parents. In other words, the program should be presented as an “accompaniment program” rather than as an “intervention.” The group also agreed that the program should listen to and address participants’ needs before discussing the children’s needs—the focus should first be on the “developing parents” and later on the “developing children.” Stimulating sensitive parenting cannot be accomplished without being sensitive to parents’ personal history, reality and internal conflicts. In addition, the actions had to be gender-specific rather than gender-neutral, and thus be delivered differently to men and women.

Overall, the group recommended that the program be designed in a way that helps participants gain awareness of their personal strengths and weaknesses; to think, in a compassionate fashion, about how their past experiences influence how they perceive themselves as person and a parent today; and to be sensitive to issues relevant to the experiences of expectant mothers and fathers. As a result, mentalization was reconsidered from being a specific dimension to address with future participants to being the core framework of the intervention. The six themes were thus regrouped in two broader categories: (1) actions with the aim of stimulating participants’ mentalization about themselves and their experience of parenthood; and (2) actions with the aim of stimulating participants’ mentalization about their adverse life experiences.

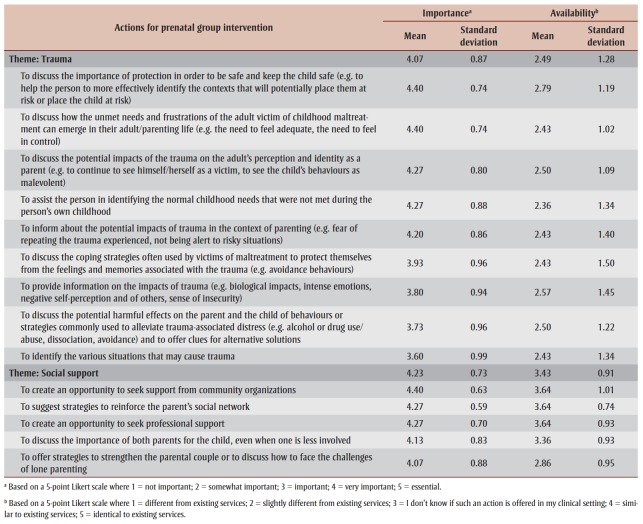

Round 2 (online survey)

Actions were refined by the project leaders and a final list of 22 (15 actions on mentalizing self and parenthood and 7 on mentalizing trauma) was sent to the stakeholders in an online survey. Fourteen participants completed this final round anonymously. The results, ranked in order of importance, are presented in Table 3. Overall, all actions were considered important.

Table 3. Final list of actions for prenatal group intervention after Delphi consensus development.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to consult with health care providers and community organizations about the actions that should be accomplished by prenatal group programs designed to help adults with personal histories of childhood trauma.

The research led to three main observations. First, we identified very few prenatal interventions specifically designed for expectant women and men who have personal histories of abuse or neglect, despite the long-term and intergenerational consequences associated with these adverse childhood experiences.39 Second, our results confirm that health care providers and community organizations consider such an intervention important and a valuable addition to the services they already offer to victims of abuse or expectant parents. Third, the mentalization framework should be considered when developing such a program, with actions aimed at supporting participants’ mentalization of their experience of parenthood and mentalization of their adverse childhood experiences.

A focus on mentalization is in accordance with recent clinical and empirical literature. Mentalization-based interventions integrate psychodynamic, cognitive and neurodevelopmental theories.47,48Mentalization-based approaches typically aim to reinforce participants’ ability to think of their behaviours and those of others (for instance, their baby) in terms of mental states. While empirical evidence confirms the efficacy of such interventions among adults with severe psychological difficulties49 and among parents of young children,50 the interventions have never been specifically adapted for expectant parents with personal histories of childhood trauma. Enhancing mentalization could play a major protective role in parents who experienced childhood trauma: mentalization abilities in pregnant women with personal histories of childhood abuse correlate with their engagement in parenthood and with the quality of their couple relationship during pregnancy8 and predict the quality of the attachment relationship they develop with their baby.22 However, enhancing mentalization in parents for whom the normal development of this ability was disturbed by adverse life circumstances is complex and calls for specific adaptations.51

This study adds to the literature on the provision of an empirically and clinically grounded framework for the development of a prenatal accompaniment program aimed at expectant parents who experienced childhood abuse or neglect. The actions identified by the stakeholders during this Delphi process differ from what currently exists in terms of prenatal psychosocial interventions in Quebec. The principal aim of many of the programs offered to the general population is to provide information on pregnancy, child development and child care. These programs, which are mainly informed by social learning theories, focus on enhancing knowledge, skills and confidence in parents through role models, practical exercises and feedback.52 Several prenatal programs have been designed for at-risk parents, and many have been shown to lead to significant improvement in parental functioning and to positive outcomes for children.39,52-54

However, to the best of our knowledge, few interventions specifically address the unique needs of parents with personal histories of trauma or use a theory of trauma as conceptual framework. Even parenting interventions aimed at preventing childhood maltreatment and trauma are rarely informed by trauma theories.55 In other words, these programs do not consider the challenges that face people who grow up in environments where their needs or vulnerabilities were neither considered nor respected in becoming parents and participating in psychosocial interventions.

Public and community services for parents and children represent an institutional space within which several approaches or perspectives coexist. Some of these are contradictory in the actions they offer to families. The implementation of a new service model for expectant parents with histories of trauma must consider this institutional complexity.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the priorities presented here reflect the perspective of stakeholders in health care and from community organizations and may not reflect the position of adults who will ultimately benefit from such psychosocial programs. Our team is investigating the points of view and specific needs in terms of prenatal interventions of adults with personal histories of childhood trauma. Second, the panel of professionals recruited for this research reflects the diverse range of services offered to victims of abuse or neglect or expectant parents in the region where the study was conducted. A panel recruited elsewhere may have identified other priorities. Third, despite that having 15 professionals involved in this process is a considerable success, the number of participants is relatively small.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this paper articulates the first set of priorities for a clinical program aimed at supporting expectant parents with personal histories of childhood trauma. This set of priorities will represent the framework for STEP, a prenatal group program currently under development that, once evaluated and implemented, will be offered to women and men who experienced childhood abuse and neglect. This program may contribute to promoting the physical and mental health of adults with personal histories of childhood trauma who are transitioning to parenthood; promoting the psychosocial development of their children; and interrupting intergenerational cycles of abuse.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada contributed financially to this research.

The authors want to thank all stakeholders who participated in this research, as well Christine Drouin-Maziade (project leader), Sylvie Moisan (research coordinator), Aurélie Baker-Lacharité (Masters student) and Vanessa Bergeron (PhD student) for their help in organizing this activity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest

Authors’ contributions and statement

NB contributed to the design and conceptualization of the study; to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; and to drafting the paper. RL contributed to the design and conceptualization of the

study; to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; and to revising the paper. CL contributed to the design and conceptualization of the study; to the acquisition of the data; and to revising the paper.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Guedeney A, Tereno S, Tyano S, Keren M, Herramn H, Cox J, et al. Transition to parenthood. Guedeney A, Tereno S. :171–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil CA, Viding E, Fearon P, Glaser D, McCrory EJ, et al. Disentangling the mental health impact of childhood abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2017:106–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, et al. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: a case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically dis¬tinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard V, Hamby S, Grych J, et al. Health effects of adverse childhood events: identifying promising protective fac¬tors at the intersection of mental and physical well-being. Child Abuse Negl. 2017:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, et al, et al. Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Rep. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot N, Ensink K, Maziade C, Giraudeau C, et al. Les défis de la parentalité pour les victimes de mauvais traite¬ments au cours de leur enfance. Berthelot N, Ensink K, Drouin- Maziade C. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Raphael-Leff J, Tyano S, Keren M, Herrman H, Cox J, et al. Mothers’ and fathers’ orientations: patterns of pregnancy, parenting and the bonding process. Raphael-Leff J. :9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ensink K, Berthelot N, Bernazzani O, Normandin L, Fonagy P, et al. Another step closer to measuring the ghosts in the nursery: preliminary validation of the Trauma Reflective Functioning Scale. Front Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasse M, Schei B, Vangen S, ian P, et al. Childhood abuse and common complaints in pregnancy. Birth. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Lyall K, Rich-Edwards JW, Ascherio A, Weisskopf MG, et al. Association of maternal exposure to childhood abuse with elevated risk for autism in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yampolsky L, Lev-Wiesel R, Ben-Zion IZ, et al. Child sexual abuse: is it a risk fac¬tor for pregnancy. J Adv Nurs. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huth-Bocks AC, Krause K, Dunn S, Gallagher E, Scott S, et al. Relational trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms among pregnant women. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1521/pdps.2013.41.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DB, Uscher-Pines L, Staples SR, Grisso JA, et al. Childhood violence and behavioral effects among urban pregnant women. Childhood violence and behavioral effects among urban pregnant women. J Womens Health [Larchmt] 2010 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I, et al. Prevalence, trauma history, and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Rodgers CS, Lebeck MM, et al. Associations between maternal child¬hood maltreatment and psychopatho¬logy and aggression during pregnancy and postpartum. Child Abuse Negl. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Sperlich M, Low LK, et al. Mental health, demographic, and risk beha¬vior profiles of pregnant survivors of childhood and adult abuse. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA, et al. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Dev. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Singer LT, Minnes S, Kim H, Short E, et al. Mediating links between maternal childhood trauma and preadolescent behavioral adjustment. J Interpers Violence. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0886260512455868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, et al. Predicting the child-rea¬ring practices of mothers sexually abused in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 2001 doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giallo R, D’Esposito F, Cooklin A, et al, et al. Psychosocial risk factors asso¬ciated with fathers’ mental health in the postnatal period: results from a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J, Assoc J, et al. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2014 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot N, Ensink K, Bernazzani O, Normandin L, Luyten P, Fonagy P, Health J, et al. Intergenerational transmission of attachment in abused and neglected mothers: the role of trauma-specific reflective functioning. Infant Ment Health J. 2015 doi: 10.1002/imhj.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Alpern L, Repacholi B, et al. Disorganized infant attachment clas¬sification and maternal psychosocial problems as predictors of hostile-aggressive behavior in the preschool classroom. Child Dev. 1993 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Goldwyn R, et al. Annotation: attachment disorganisation and psy¬chopathology: new findings in attach¬ment research and their potential implications for developmental psy¬chopathology in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002 doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, et al, et al. Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: implications for fetal brain development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand SR, Brennan PA, Newport DJ, Smith AK, Weiss T, Stowe ZN, et al. The impact of maternal childhood abuse on maternal and infant HPA axis function in the postpartum period. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Smith A, Kamkwalala A, et al, et al. Physiological markers of anxiety are increased in children of abused mothers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhre MC, Dyb GA, Wentzel-Larsen T, gaard JB, Thoresen S, et al. Maternal childhood abuse predicts externali¬zing behaviour in toddlers: A pros¬pective cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1403494813510983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant DT, Barker ED, Waters CS, Pawlby S, Pariante CM, et al. Intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and psychopathology: the role of antenatal depression. Psychol Med. 2013 doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S, Dunn J, O’Connor TG, et al. Maternal childhood abuse and offs¬pring adjustment over time. Dev Psychopathol. 2007 doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertem IO, Leventhal JM, Dobbs S, et al. Intergenerational continuity of child physical abuse: how good is the evi¬dence. Lancet. 2000 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Kotake C, Fauth R, Easterbrooks MA, et al. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: do maltreatment type, perpe¬trator, and substantiation status mat¬ter. chiabu. 2017:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Lee RD, Merrick MT, et al. Safe, stable, nurturing relationships as a moderator of intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Health J, et al. The nurse-family partnership: an evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Ment Health J. 2006 doi: 10.1002/imhj.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin B, et al. The Circle of Security inter¬vention: enhancing attachment in early parent-child relationships. Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin B. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Grant H, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, et al. Randomized trial of the Early Start program of home visita¬tion: parent and family outcomes. Pediatrics. 2006 doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Mayes LC, Fonagy P, Allen JG, et al. Minding the Baby®: A mentalization-based parenting program. Sadler LS, Slade A, Mayes LC. :271–88. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN, et al. Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impair¬ment. Lancet. 2009 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson LA, Beck K, Busuulwa P, et al, et al. Perinatal interventions for mothers and fathers who are survi¬vors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2018:9–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe H, Sperlich M, Cameron H, Seng J, et al. A quasi-experimental outco¬mes analysis of a psychoeducation intervention for pregnant women with abuse-related posttraumatic stress. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan AJ, Bucio GO, Rivera LM, Lieberman AF, et al. Making sense of the past creates space for the baby: Perinatal Child-Parent Psychotherapy for Pregnant Women with Childhood Trauma. Zero Three. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Cohen LJ, Sadler LS, Miller M, Zeanah CH, Edition ed, et al. The psychology and psychopatho¬logy of pregnancy: reorganization and transformation. Handbook of infant mental health. :22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Biring GS, Dwyer TF, Huntington DC, Valenstein AF, et al. A study of the psycho¬logical processes in pregnancy and the earliest mother-child relationship. Psychoanal Study Child. 1961 [Google Scholar]

- Fekri O, Leeb K, Gurevich Y, et al. Systematic approach to evaluating and confirming the utility of a suite of national health system performance [HSP] indicators in Canada: a modi¬fied Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen LJ, O’Connor M, Calder S, Tai V, Cartwright J, Beilby JM, et al. The health professionals’ perspectives of support needs of adult head and neck cancer survivors and their families: a Delphi study. Support Care Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3647-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, et al. Development of mental health first aid guidelines on how a member of the public can support a person affec¬ted by a traumatic event: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JG, et al. Mentalizing as a conceptual bridge from psychodynamic to cogni¬tive-behavioral therapies. European Psychotherapy. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Allen JG, Fonagy P, Bateman A, et al. Mentalizing in clinical practice. Allen JG, Fonagy P, Bateman A. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentali¬zation-based treatment versus struc¬tured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, et al, Health J, et al. Minding the Baby: enhancing reflec¬tiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdis¬ciplinary home visiting program. Infant Ment Health J. 2013 doi: 10.1002/imhj.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacharite C, Lafantaisie V, et al. Le rôle de la fonction réflexive dans l’interven¬tion auprès de parents en contexte de négligence envers l’enfant. Rev Que Psychol. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J, Nelson G, et al. Programs for the promotion of family wellness and the prevention of child maltreatment: a meta-analytic review. Child Abuse Negl. 2000 doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman HJ, Olds DL, Cole RE, et al, et al. Enduring effects of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses on children: follow-up of a randomized trial among children at age 12 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010 doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Kitzman HJ, Cole RE, et al, et al. Enduring effects of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses on maternal life course and government spending: follow-up of a randomized trial among children at age 12 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010 doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, et al. Preventing child abuse and neglect with parent training: evidence and opportunities. Future Child. 2009 doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]