A better understanding of clinician and patient characteristics that are associated with referral for palliative care in a real‐world context may help to overcome barriers to timely palliative care access. This article reports patterns of outpatient palliative care referral among thoracic medical oncologists and identifies oncologist characteristics associated with greater referral.

Keywords: Ambulatory care; Health knowledge, attitudes, practice; Health services research; Neoplasms; Palliative care; Referral and consultation

Abstract

Background.

There is significant variation in access to palliative care. We examined the pattern of outpatient palliative care referral among thoracic medical oncologists and identified oncologist characteristics associated with greater referral.

Materials and Methods.

We retrieved data on all patients who died of advanced thoracic malignancies at our institution between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2012. Using median as a cutoff, we defined two groups (high‐referring and low‐referring oncologists) based on their frequency of referral. We examined various oncologist‐ and patient‐related characteristics associated with outpatient referral.

Results.

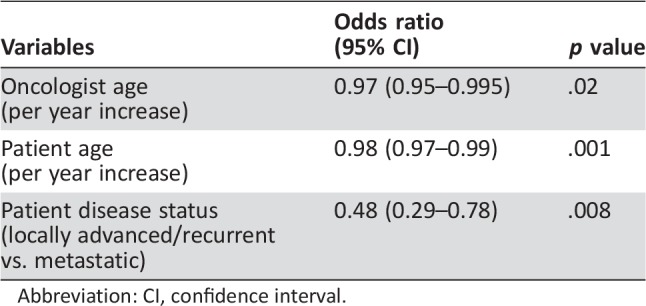

Of 1,642 decedents, 444 (27%) had an outpatient palliative care referral. The median proportion of referral among 26 thoracic oncologists was 30% (range 9%–45%; median proportion of high‐referring 37% vs. low‐referring 24% when divided into two groups at median). High‐referring oncologists were significantly younger (age 45 vs. 56) than low‐referring oncologists; they were also significantly more likely to refer patients earlier (median interval between oncology consultation and palliative care consultation 90 days vs. 170 days) and to refer those without metastatic disease (7% vs. 2%). In multivariable mixed‐effect logistic regression, younger oncologists (odds ratio [OR] = 0.97 per year increase, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.95–0.995), younger patients (OR = 0.98 per year increase, 95% CI 0.97–0.99), and nonmetastatic disease status (OR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.29–0.78) were significantly associated with outpatient palliative care referral.

Conclusion.

The pattern of referral to outpatient palliative care varied widely among thoracic oncologists. Younger oncologists were not only referring a higher proportion of patients, but also referring patients earlier in the disease trajectory.

Implications for Practice.

This retrospective cohort study found that younger thoracic medical oncologists were significantly more likely to refer patients to outpatient palliative care and to do so earlier in the disease trajectory compared with older oncologists, even after adjusting for other known predictors such as patient demographics. The findings highlight the role of education to standardize palliative care access and imply that outpatient palliative care referral is likely to continue to increase with a shifting oncology workforce.

Introduction

Patients with advanced thoracic malignancies typically have a high symptom burden and poor prognosis [1], [2]. Multiple studies have shown that timely palliative care referral can result in improved outcomes for these patients, such as symptom intensity, quality of life, satisfaction, care planning, and even survival [3], [4], [5], [6]. Among the different branches of palliative care services, outpatient clinics are essential to facilitate timely access [7] and are associated with better outcomes than inpatient palliative care [8]. Despite the large body of evidence to support timely palliative care, a sizable proportion of patients with advanced thoracic malignancies still do not receive palliative care before death. Among patients referred to palliative care, the timing of referral also varied widely [9], [10].

The barriers for timely palliative care referral can be classified as patient‐related, oncologist‐related, and system‐related factors. Because oncologists are the frontline providers for cancer patients, they play a particularly important role as gatekeepers for timely palliative care access. To date, a majority of palliative care referrals are initiated based on oncology teams’ clinical judgement instead of automatic referrals based on standardized criteria [11], [12]. Several qualitative and quantitative studies have examined how the attitudes and beliefs of oncologists toward palliative care could affect their willingness to refer patients [13], [14], [15], [16]; however, there is a paucity of literature on which oncologist characteristics and patient characteristics are associated with the actual volume of outpatient palliative care referral [9]. A better understanding of which clinician and patient characteristics are associated with the volume of palliative care referral in the real‐world context may help to overcome the barriers to timely palliative care access. In this study, we examined the pattern of referral in the thoracic medical oncology setting and identified oncologist characteristics associated with outpatient palliative care referral, while adjusting for patient‐related factors. We hypothesize that certain oncologist‐related characteristics may be associated with the variation in referral. We focused on thoracic medical oncology because of the high mortality and morbidities associated with advanced thoracic malignancies and the strong body of evidence to support timely palliative care referral for these patients [4], [5].

Materials and Methods

Eligibility Criteria

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) reviewed and approved this retrospective study. Because a prospective observational study may introduce bias in the pattern of referral, we elected to use a retrospective design involving consecutive patients. Because the main study outcome was whether patients had a palliative care referral, we only included decedents to determine if they received a referral anytime along the entire disease trajectory. Outpatient instead of inpatient palliative care referral was chosen as the primary outcome because this is the only setting to facilitate timely referral [11]. Although limiting generalizability, this single‐center design allowed us to control for inter‐institutional differences in palliative care services and to maximize the accuracy of data collection in regard to oncologist‐related and patient‐related variables and outcomes.

Consecutive cancer decedents were included in this study if they were age 18 or older; had a diagnosis of advanced thoracic malignancy, defined as locally advanced, metastatic, or recurrent lung cancer or mesothelioma; had a postal address within Harris county and the seven‐county Houston metropolitan area (Brazoria, Chambers, Fort Bend, Galveston, Liberty, Montgomery, and Waller); were seen at MDACC for consultation between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2012; and had last contact with MDACC as an inpatient or outpatient ≤3 months before death. These criteria were designed to identify patients who were followed by our institution throughout their entire disease trajectory.

Data Collection

For all included patients, we collected key demographic data at the time of their consultation with an attending thoracic medical oncologist, such as age, sex, race, and cancer diagnosis and stage from the electronic medical record. We also identified the date of thoracic medical oncology consultation, date of palliative care referral, and date of death. These were used to determine the interval from oncology consultation to palliative care referral, time from palliative care referral to death, and time from oncology consultation to death. We also collected attending oncologist‐related characteristics based on publicly available information from the Texas Medical Board, including age, sex, and year of medical school graduation.

We determined if each patient had an outpatient palliative care referral at MDACC, which allowed us to compute the key independent variable for this study—the proportion of patients who were referred to outpatient palliative care by each thoracic medical oncologist.

Statistical Analysis

For analysis purposes, we classified the oncologists into two groups—high‐referring oncologists and low‐referring oncologists—using the median frequency of outpatient palliative care referral as a cutoff.

The baseline patient demographics were summarized using standard descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, median, range, interquartile range (IQR), frequency, and percentages. We calculated median and 95% confidence intervals for time from palliative care consult to death and time from oncology consult to death.

We also examined the association between frequency of referral (high vs. low) and oncologist characteristics using the Mann‐Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. We conducted a mixed‐effect logistic regression analysis to evaluate potential factors for frequency of referral incorporating both oncologist‐related variables and patient‐related variables. We fitted a two‐level hierarchical model (level 1: patient level, level 2: oncologist level) with a random intercept for oncologists, which allows variations at the level of the oncologist. We considered the following variables to build the model: oncologist's age and sex and patient's age, sex, race, cancer diagnosis, and stage. Backward selection was used to determine the final model. Because oncologist's years of experience was closely associated with oncologist's age, only age was entered into the model.

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis. A p value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

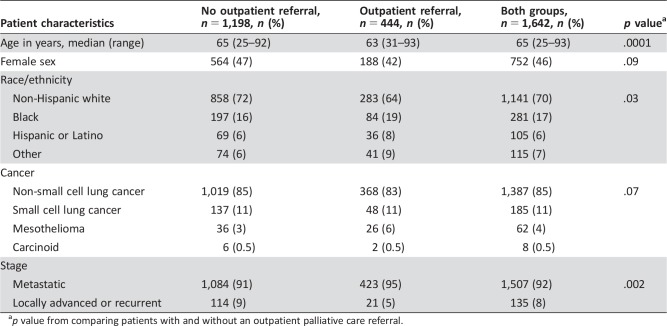

In total, 1,642 patients met study eligibility and were included in this study. They were seen by 26 thoracic medical oncologists. The average age was 65 (range 25–93), and 752 (46%) were female (Table 1). A majority of the patients were diagnosed with non‐small cell lung cancer (n = 1,387, 85%) and had metastatic disease (n = 1,507, 92%).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients referred to outpatient palliative care (n = 1,642).

p value from comparing patients with and without an outpatient palliative care referral.

Pattern of Palliative Care Referral

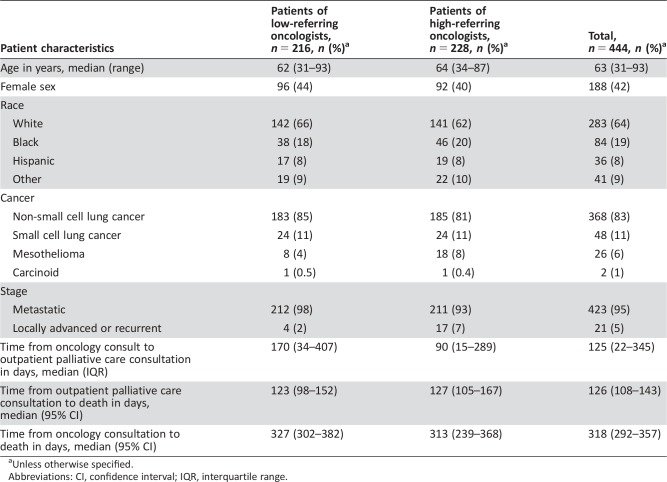

In this cohort, 444 (27%) had an outpatient palliative care referral, 485 (29%) had an inpatient palliative care referral, and 713 (44%) had no referral before death. Among patients with an outpatient referral, the median interval from thoracic oncology consultation to palliative care consultation was 125 days (IQR 22, 345 days; Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of patient referral to outpatient palliative care by oncologist type.

Unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range.

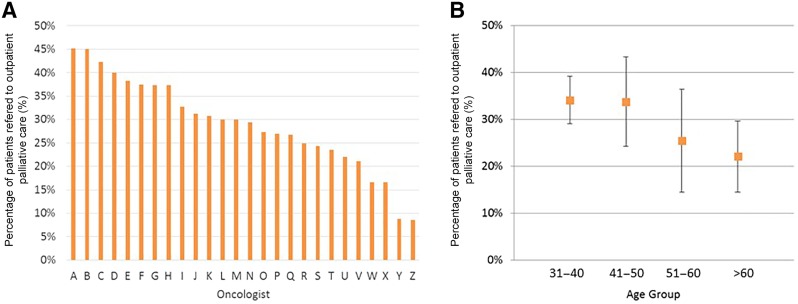

The proportion of patients with outpatient palliative care referral varied widely among oncologists, ranging from 9% to 45% (Fig. 1A). The median proportion of referral was 30% (IQR 24%, 38%). Specifically, the median outpatient palliative care referral rate for the 13 high‐referring oncologists and 13 low‐referring oncologists was 37% (IQR 31%, 40%) and 24% (IQR 17%, 27%), respectively.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients referred to outpatient palliative care. (A): The percentage of patients referred to palliative care by each oncologist. (B): Younger oncologists were more likely to refer a higher percentage of patients to outpatient palliative care. The mean percentages of referrals were plotted along with standard deviations.

Factors Associated with High‐Referring Oncologists

Table 2 shows that high‐referring oncologists were generally more likely to refer patients earlier in the disease trajectory, with a shorter interval from oncology consultation to palliative care consultation (90 days vs. 170 days) despite similar overall disease trajectories. Patients of high‐referring oncologists were also more likely to have nonmetastatic advanced disease (7% vs. 2%; Table 2).

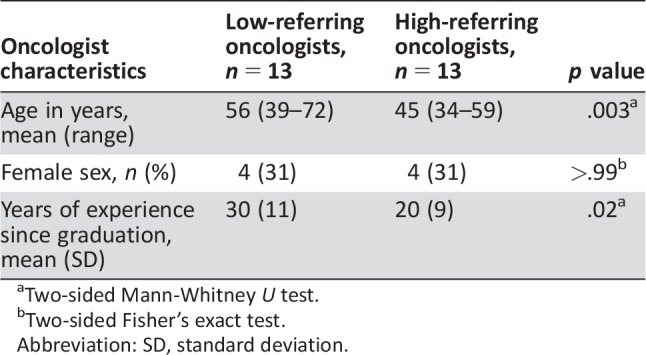

High‐referring oncologists were more likely to be younger (age 45 vs. 56, p = .003) and had fewer years of experience since graduation (mean 20 years vs. 30 years, p = .005; Table 3). Figure 1B illustrates the gradient relationship between increasing oncologist age and decreasing outpatient palliative care referral.

Table 3. Oncologist characteristics associated with referral to palliative care.

Two‐sided Mann‐Whitney U test.

Two‐sided Fisher's exact test.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Patient Factors Associated with Referral to Outpatient Palliative Care

Table 1 shows that patients who were younger (age 63 vs. 65, p = .0001), non‐white race (36% vs. 28%, p = .025), and those with metastatic disease (95% vs. 91%, p = .002) were more likely to be referred to outpatient palliative care.

Multivariable Analysis

In a mixed‐effect logistic regression model adjusting for both oncologist and patient characteristics, higher oncologist age, higher patient age, and nonmetastatic disease status were significantly associated with lower frequency of outpatient palliative care (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariable mixed‐effect logistic regression model examining oncologist characteristics associated with referral to outpatient palliative care.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In this cohort of patients with advanced thoracic malignancy, we found that only approximately one in three patients had a referral to outpatient palliative care before death. There was wide variation in the pattern of referral among oncologists. Oncologists who referred a higher proportion of their patients were also more likely to refer patients earlier in the disease trajectory and to be younger. Indeed, oncologist age was independently associated with higher rates of outpatient palliative care referral after adjusting for established patient‐related variables. Our preliminary findings highlight the role that oncologists have in facilitating timely palliative care access and potential strategies to improve referral through clinician education and standardized care pathways.

Existing literature has mostly focused on the timing of palliative care referral and its predictors, and few studies have examined another important marker of palliative care access—the volume of referral. This study specifically examined outpatient instead of inpatient referral because palliative care clinics represent the key to timely access and facilitate longitudinal care [11], [17], [18]. Furthermore, the published studies on this topic were mostly qualitative in nature and examined attitudes and beliefs toward palliative care and perceived barriers for referral instead of actual referral patterns [13], [14], [15]. This study provides a unique examination of a sizable dataset of quantitative data on the volume and timing of referral. At the same time, the single‐center nature of this study allowed us to control for the availability of palliative care service and other system‐related constraints that may also impact referral. Because of the size of our comprehensive cancer center, we were able to include a relatively large cohort of patients and thoracic medical oncologists.

We identified a wide variation in the frequency of outpatient palliative care referral. Of note, even the highest‐referring oncologists referred less than 50% of their patients with advanced thoracic malignancies before death. This may be partly explained by the following: (a) some patients had low care needs that were already addressed by the oncology team; (b) some patients had severe symptoms requiring admission shortly after diagnosis and were referred to inpatient palliative care instead. Nevertheless, a sizable proportion of patients may have missed the opportunity to be referred. Contemporary clinical trials clearly demonstrated that timely involvement of palliative care in conjunction with oncology can improve quality of life compared with oncology team alone [19]. Thus, there appears to be more room for improvement. Because palliative care does not have the infrastructure to see all patients with advanced cancer [20], implementation of standardized criteria to identify patients who would be most likely to benefit from a palliative care intervention coupled with automatic referral may improve the consistency of the referral process. A recent Delphi study involving 60 international experts achieved a high level of consensus for 11 major criteria to trigger outpatient palliative care referral [21]. Further empirical testing is needed. Other approaches to improve palliative care access and standardize care include health policy reform (e.g., incentives), quality improvement initiatives, and medical education.

One of the most important findings of this study is that younger oncologists were more likely to refer patients to palliative care. Our findings are consistent with recent literature suggesting that patients of younger physicians may have better outcomes [22]. We hypothesize that younger oncologists were (a) more familiar with the concept of early palliative care compared with their more senior colleagues, (b) more prepared to adopt new advances based on the literature, and (c) more willing to adhere to clinical practice guidelines. A recent survey found that medical oncology fellows at our institution who all had a 1‐month palliative care rotation had a higher level of awareness of the role of palliative care than fellows who did not have a rotation [23]. This rotation offers an enriched opportunity for oncology trainees to gain a better understanding of the role of palliative care and to build a professional relationship with the palliative care team. However, only approximately 25% of cancer centers in the U.S. have a mandatory palliative care rotation for oncology fellows, suggesting room for improvement [10], [24]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network also published multiple clinical practice guidelines to promote early palliative care [25], [26], [27], which may be more readily adopted by younger oncologists.

Schenker et al. conducted a qualitative study of 74 medical oncologists to assess clinician factors that affect outpatient palliative care referral [13]. They reported three main barriers, including the misconception that palliative care is not compatible with cancer treatments, lack of knowledge about palliative care services available locally, and the belief that oncologists have the primary responsibility to provide palliative care. Importantly, all these barriers could potentially be addressed by education. As more oncology fellows who received palliative care training embark on their careers, we expect that outpatient palliative care referral is likely to continue to increase. Encouragingly, oncologists were not only more likely to refer a greater proportion of their patients but also to do so earlier in the disease trajectory (even after controlling for outpatient referral only). Other strategies such as the use of the name “Supportive Care” to reduce stigma associated with palliative care may also facilitate greater frequency and earlier referrals [15], [28], [29].

At the patient level, being younger, non‐white race, and having a diagnosis of metastatic cancer (instead of locally advanced disease) were associated with higher rates of outpatient palliative care referral. Previous studies have consistently found that younger individuals were more likely to be referred, likely because of increased distress and care needs [9], [30]. Because many of the randomized trials examining palliative care enrolled only patients with metastatic disease, it also makes sense why these patients were more likely to be referred. A majority of studies examining racial disparities in palliative care access have focused on hospice referral, and no studies have specifically examined ethnicity/race as a predictor of outpatient palliative care referral. Importantly, a majority of patients seen at our center were white. Further studies are needed to validate our findings.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a single‐center study to control for institution‐ or health system‐related factors that may influence referral. However, the unique characteristics of patients and oncologists at our comprehensive cancer center may not be generalizable to other settings, which could significantly impact the external validity of our findings. Further research in other centers is necessary to confirm our findings. Second, we were only able to include a relatively small cohort of medical oncologists. We also assumed that patients were randomly assigned to oncologists; however, if patients with greater supportive care needs were selectively being seen by junior oncologists, this could impact the interpretation of our findings. Third, the retrospective design limited our ability to systematically collect many other variables that may also impact referral, such as performance status, patient's preferences, and attitudes and beliefs. Our group and others have previously examined these factors utilizing survey or qualitative research methodologies [13], [15], [31], [32]. Moreover, we did not retrieve the reasons for referral because they were often vaguely and incompletely stated and would be better captured in a prospective design. Fourth, by including only patients with advanced cancer who died, this study may be biased toward patients with more aggressive disease and may affect the referral pattern. However, given that this study included consecutive decedents over 5 years and that a majority of patients with advanced cancer die of their disease, we expect the impact to be minimal. Fifth, we only included data from 2007 to 2012 when the pattern of referral for outpatient palliative care is rapidly evolving. Sixth, we did not retrieve the reasons for referral because they were often vaguely and incompletely stated and would be better captured in a prospective design. Finally, we conducted multiple statistical analyses with a limited sample size. The predictors of outpatient referral should thus be considered hypothesis generating.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the wide variation in outpatient palliative care referral among thoracic medical oncologists. Education programs, clinical practice guidelines, and standardized automatic referral may help to standardize palliative care referral [11]. Encouragingly, younger oncologists were associated with greater volume and earlier timing of referral in this exploratory study. As the oncology workforce continues to evolve, more patients will likely gain access to outpatient palliative care.

Acknowledgments

D.H. and E.B. are supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants (1R01CA214960‐01A1, R21NR016736). D.H. is also supported by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research (MRSG‐14‐1418‐01‐CCE) and the Andrew Sabin Family Fellowship Award. M.P. and D.L. are supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016672).

Author Contributions

Conception/design: David Hui, Kelly Kilgore, Minjeong Park, Diane Liu, Frank Fossella, Eduardo Bruera

Provision of study material or patients: David Hui, Kelly Kilgore, Yu Jung Kim, Ji Chan Park, Frank Fossella

Collection and/or assembly of data: David Hui, Kelly Kilgore, Yu Jung Kim, Ji Chan Park

Data analysis and interpretation: David Hui, Minjeong Park, Diane Liu, Eduardo Bruera

Manuscript writing: David Hui

Final approval of manuscript: David Hui, Kelly Kilgore, Minjeong Park, Diane Liu, Yu Jung Kim, Ji Chan Park, Frank Fossella, Eduardo Bruera

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Tishelman C, Petersson LM, Degner LF et al. Symptom prevalence, intensity, and distress in patients with inoperable lung cancer in relation to time of death. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5381–5389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA et al. Phase II study: Integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2377–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakitas M, Stevens M, Ahles T et al. Project ENABLE: A palliative care demonstration project for advanced cancer patients in three settings. J Palliat Med 2004;7:363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Temel JS, Greer JA, El‐Jawahri A et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;35:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalal S, Bruera S, Hui D et al. Use of palliative care services in a tertiary cancer center. The Oncologist 2016;21:110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end‐of‐life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014;120:1743–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist 2012;17:1574–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA 2010;303:1054–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:159–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hui D, Mori M, Meng YC et al. Automatic referral to standardize palliative care access: An international Delphi survey. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schenker Y, Crowley‐Matoka M, Dohan D et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract 2013;10:e37–e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N et al. Referral practices of oncologists to specialized palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4380–4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hui D, Park M, Liu D et al. Attitudes and beliefs toward supportive and palliative care referral among hematologic and solid tumor oncology specialists. The Oncologist 2015;20:1326–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hay CM, Lefkowits C, Crowley‐Matoka M et al. Gynecologic oncologist views influencing referral to outpatient specialty palliative care. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2017;27:588–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hannon B, Swami N, Pope A et al. Early palliative care and its role in oncology: A qualitative study. The Oncologist 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schenker Y, Arnold R. Toward palliative care for all patients with advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1459–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hui D, Masanori M, Watanabe S et al. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e552–e559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsugawa Y, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM et al. Physician age and outcomes in elderly patients in hospital in the US: Observational study. BMJ; 2017;357:j1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong A, Reddy A, Williams JL et al. ReCAP: Attitudes, beliefs, and awareness of graduate medical education trainees regarding palliative care at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:149–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM et al. Hematology/oncology fellows' training in palliative care: Results of a national survey. Cancer 2011;117:4304–4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3052–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL et al. Supportive versus palliative care: What's in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009;115:2013–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist 2011;16:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burt J, Raine R. The effect of age on referral to and use of specialist palliative care services in adult cancer patients: A systematic review. Age Ageing 2006;35:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hui D, Cerana MA, Park M et al. Impact of oncologists' attitudes toward end‐of‐life care on patients' access to palliative care. The Oncologist 2016;21:1149–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith CB, Nelson JE, Berman AR et al. Lung cancer physicians' referral practices for palliative care consultation. Ann Oncol 2012;23:382–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]