Abstract

Background

An improved understanding of how gender differences and the natural aging process are associated with differences in clinical improvement in outcome metric scores and ROM measurements after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) may help physicians establish more accurate patient expectations for reducing postoperative pain and improving function.

Questions/purposes

(1) Is gender associated with differences in rTSA outcome scores like the Simple Shoulder Test (SST), the UCLA Shoulder score, the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Shoulder score, the Constant Shoulder score, and the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) and ROM? (2) Is age associated with differences in rTSA outcome scores and ROM? (3) What factors are associated with the combined interaction effect between age and gender? (4) At what time point during recovery does most clinical improvement occur, and when is full improvement reached?

Methods

We quantified and analyzed the outcomes of 660 patients (424 women and 236 men; average age, 72 ± 8 years; range, 43-95 years) with cuff tear arthropathy or osteoarthritis and rotator cuff tear who were treated with rTSA by 13 shoulder surgeons from a longitudinally maintained international database using a linear mixed effects statistical model to evaluate the relationship between clinical improvements and gender and patient age. We used five outcome scoring metrics and four ROM assessments to evaluate clinical outcome differences.

Results

When controlling for age, men had better SST scores (mean difference [MD] = 1.41 points [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.07–1.75], p < 0.001), UCLA scores (MD = 1.76 [95% CI, 1.05–2.47], p < 0.001), Constant scores (MD = 6.70 [95% CI, 4.80–8.59], p < 0.001), ASES scores (MD = 7.58 [95% CI, 5.27-9.89], p < 0.001), SPADI scores (MD = -12.78 [95% CI, -16.28 to -9.28], p < 0.001), abduction (MD = 5.79° [95% CI, 2.74-8.84], p < 0.001), forward flexion (MD = 7.68° [95% CI, 4.15-11.20], p < 0.001), and passive external rotation (MD = 2.81° [95% CI, 0.81-4.8], p = 0.006). When controlling for gender, each 1-year increase in age was associated with an improved ASES score by 0.19 points (95% CI, 0.04–0.34, p = 0.011) and an improved SPADI score by -0.29 points (95% CI, -0.46 to 0.07, p = 0.020). However, each 1-year increase in age was associated with a mean decrease in active abduction by 0.26° (95% CI, -0.46 to 0.07, p = 0.007) and a mean decrease of forward flexion by 0.39° (95% CI, -0.61 to 0.16, p = 0.001). A combined interaction effect between age and gender was found only with active external rotation: in men, younger age was associated with less active external rotation and older age was associated with more active external rotation (β0 [intercept] = 11.029, β1 [slope for age variable] = 0.281, p = 0.009). Conversely, women achieved no difference in active external rotation after rTSA, regardless of age at the time of surgery (β0 [intercept] = 34.135, β1 [slope for age variable] = -0.069, p = 0.009). Finally, 80% of patients achieved full clinical improvement as defined by a plateau in their outcome metric score and 70% of patients achieved full clinical improvement as defined by a plateau in their ROM measurements by 12 months followup regardless of gender or patient age at the time of surgery with most improvement occurring in the first 6 months after rTSA.

Conclusions

Gender and patient age at the time of surgery were associated with some differences in rTSA outcomes. Men had better outcome scores than did women, and older patients had better outcome scores but smaller improvements in function than did younger patients. These results demonstrate rTSA outcomes differ for men and women and for different patient ages at the time of surgery, knowledge of these differences, and also the timing of improvement plateaus in outcome metric scores and ROM measurements can both improve the effectiveness of patient counseling and better establish accurate patient expectations after rTSA.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Prior research has identified associations between gender and patient age at the time of surgery with results of many orthopaedic procedures, including anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, osteoarthritis, shoulder instability, and hip fracture surgery [4, 6, 8, 18]. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) has been performed in the United States since its 510k clearance in November 2003 and was initially indicated for rotator cuff tear arthropathy in the elderly patient [2, 3, 7, 9, 12, 13, 15-17]. Gender and age differences have previously been shown to be associated with different patient expectations for anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (aTSA), but no such study has evaluated any association of gender and age differences with rTSA [4, 6].

The use of rTSA has increased at a greater rate than other shoulder arthroplasty procedures, and the mean age of patients undergoing this procedure also has decreased [11]. Even with rTSA use increasing across multiple age groups, little information exists regarding if gender and patient age at the time of surgery are associated with differences in the rate and magnitude of clinical improvement after rTSA. An improved understanding of how gender differences and the natural aging process are associated with the rates and magnitude of clinical improvement in outcome metric scores and ROM measurements after rTSA may help physicians establish more accurate patient expectations for postoperative pain reduction and functional improvement and may lead to greater patient satisfaction with the results of surgery.

Therefore, we asked: (1) Is gender associated with differences in rTSA outcome scores such as the Simple Shoulder Test (SST), the UCLA Shoulder score, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Shoulder score, Constant Shoulder score, and the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) and ROM? (2) Is age associated with differences in rTSA outcome scores and ROM? (3) What factors are associated with a combined interaction effect between age and gender? (4) At what time point during recovery does most clinical improvement occur, and when is full improvement reached? To answer these questions, we used a linear mixed effects statistical model to evaluate five different outcome scoring metrics and four ROM assessments in 660 patients undergoing rTSA for cuff tear arthropathy or rTSA for osteoarthritis with rotator cuff tear.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective, comparative study focused on patients who were followed in a longitudinally maintained multicenter registry between March 2007 and March 2014. The study group consisted of 1569 patients who underwent rTSA performed by one of 13 fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeons using a single platform shoulder system (Equinoxe; Exactech, Inc, Gainesville, FL, USA). Institutional review board approval was obtained. Inclusion criteria for this study were either cuff tear arthropathy or osteoarthritis with rotator cuff tear; revisions and rTSA performed for any other diagnoses were excluded; application of these criteria reduced the number of eligible patients undergoing rTSA to 1419. Seven hundred eighty of these 1419 patients were eligible for at least 2-year followup at the time of this analysis, and of those, 660 (85%) were available for review. The remaining patients were lost to followup. Mean age was 72 ± 8 years (range, 43–95 years). The earliest recorded followup visit was 2 weeks and the longest recorded followup was 96 months. Mean followup at the latest visit was 37 ± 16 months. In all, 424 of 660 of participants (64%) were women.

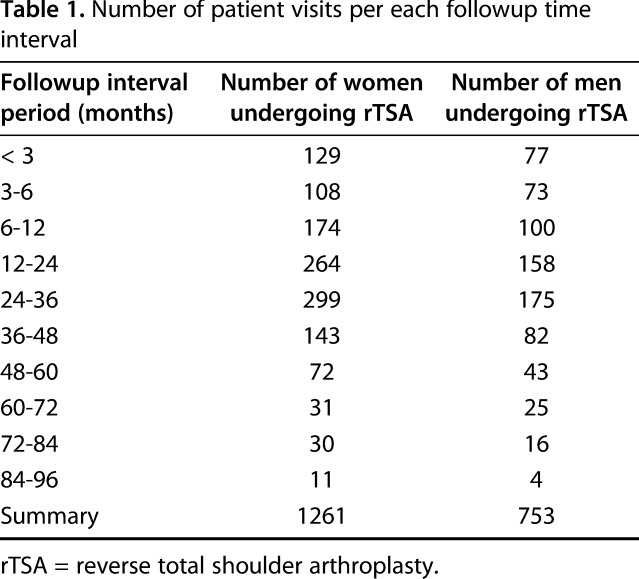

We collected patient data preoperatively and then at regular intervals until latest followup. Followup visits were typically at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and annually thereafter. However, each patient did not have every time point visit, in which case evaluation took place at the next possible time. To be included in this study, each patient must have had a preoperative evaluation and at least two followup visits. These criteria permitted a more direct comparison of results achieved for each gender and age group over time. A total of 2014 followup reports were analyzed (1261 women, 753 men) with variable report numbers per visit interval (Table 1). We used five clinical metrics to quantify outcomes, which were calculated within the database without any separate chart review: the SST, the UCLA Shoulder score, the ASES Shoulder score, the Constant Shoulder score, and the SPADI. Additionally, active abduction, active forward flexion as well as active and passive external rotation with the arm at the side were also measured. These ROM measurements were made using a goniometer with the patient in a standing position to standardize recording across study sites. Measurements were made by the surgeon, research coordinator, or physical therapist.

Table 1.

Number of patient visits per each followup time interval

The design of the study included clinical metrics and ROM measurements taken at multiple time points for each patient by each surgeon. As a result of this data structure, there are three hierarchically nested units of analysis. At the first level are multiple measurements over time for clinical outcome metrics and ROM measurements. These measurements are nested within patients, which is the second level. Finally, the patients are nested within each surgeon, which is the third level. We analyze this multilevel data structure to not violate the independence assumption that is required to correctly infer statistically significant differences between age and gender. Multiple measurements for the same patient at preoperative and postoperative visits cannot be considered independent observations; thus, each patient's clinical metric scores and ROM measurements are interdependent. Additionally, each orthopaedic surgeon has interdependent clinical metric scores and ROM measurements associated with their particular set of patients that they evaluate preoperatively and at each postoperative visit.

To investigate the clinical metric scores and ROM measurements using this three-level data structure, we have constructed a particular type of linear statistical model. This linear model essentially has two parts: variation that is systematic (ie, that which can be explained by explanatory variables) and variation that we cannot control for using the explanatory variables (ie, the error term). The linear mixed model that we used in this study incorporates additional error terms (called random intercepts) into the statistical model to account for effects seen at the second level (ie, the patient effect) and the third level (ie, the surgeon effect). The two random intercepts essentially provide structure to the overall error term. In the linear mixed model for this study, the random intercepts characterize the variation that is the result of differences in individual patient measurements along with differences among patients for each surgeon. By incorporating these two random intercepts for patient- and surgeon-level effects into our statistical model, we are able to interpret and generalize the results of our model to the larger population of patients undergoing rTSA. To investigate the influence of age and gender on postoperative clinical metric scores and ROM measurements, a continuous age variable and a binary gender variable were added to the linear mixed model as fixed effects/explanatory variables.

The statistical software used for the linear mixed effects analysis was R and the lme4 package [1, 10]. The difference between each postoperative followup visit and the corresponding preoperative value was quantified and defined as improvement. Clinical improvement for each outcome scoring metric and ROM measurement was reviewed for all patients by followup duration and analyzed using two-sample t-tests to compare preoperative and latest postoperative results for gender. The p values for the t-tests between genders for mean preoperative, postoperative, and pre- to postoperative improvement at latest followup were adjusted for Type 1 error rates to control for false discovery rates using the Holm-Bonferroni method [5]. Full improvement was defined as the time duration after surgery in which the cohort stopped improving relative to their preoperative measure for each outcome metric and each ROM measurement.

Results

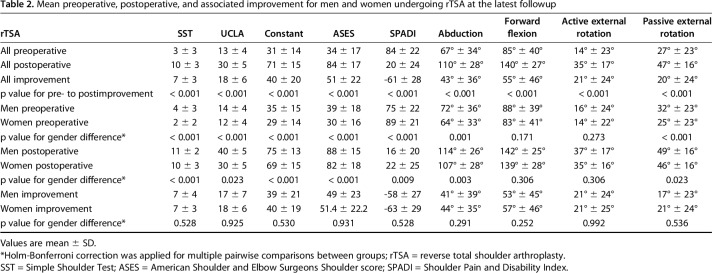

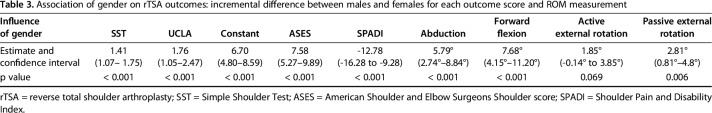

At latest followup, patients were improved after rTSA according to each outcome metric and ROM measurement (Table 2). Before surgery, female patients undergoing rTSA were worse than male patients undergoing rTSA based on five of five scoring metrics and two of four ROM measurements (Table 2). At latest followup, female patients undergoing rTSA were worse than male patients undergoing rTSA based on five of five scoring metrics and two of four ROM measurements (Table 2). However, no difference was noted between men and women in pre- to postclinical improvement for any scoring metric or any ROM measurement (Table 2). When controlling for age (Table 3), men had better SST scores (mean difference [MD] = 1.41 points [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.07–1.75], p < 0.001), UCLA scores (MD = 1.76 [95% CI, 1.05–2.47], p < 0.001), Constant scores (MD = 6.70 [95% CI, 4.80–8.59], p < 0.001), ASES scores (MD = 7.58 [95% CI, 5.27-9.89], p < 0.001), SPADI scores (MD = -12.78 [95% CI, -16.28 to -9.28], p < 0.001), abduction (MD = 5.79° [95% CI, 2.74-8.84], p < 0.001), forward flexion (MD = 7.68° [95% CI, 4.15-11.20], p < 0.001), and passive external rotation (MD = 2.81° [95% CI, 0.81-4.8], p = 0.006). However, there was no difference in active external rotation (1.85° [95% CI, -0.14 to 3.85], p = 0.069).

Table 2.

Mean preoperative, postoperative, and associated improvement for men and women undergoing rTSA at the latest followup

Table 3.

Association of gender on rTSA outcomes: incremental difference between males and females for each outcome score and ROM measurement

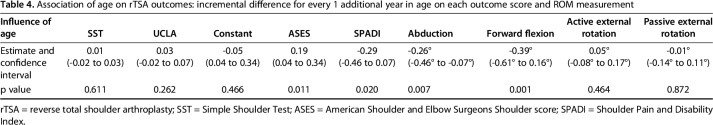

We controlled for gender (Table 4) and found that each 1-year increase in age was associated with an improved ASES score by 0.19 points (95% CI, 0.04–0.34; p = 0.011) and an improved SPADI score by -0.29 points (95% CI, -0.46 to 0.07; p = 0.020). Because a smaller SPADI score and a larger ASES score both correspond to better outcomes, older patients were associated with better outcomes according to both ASES and SPADI as compared with younger patients. Conversely, each 1-year increase in age was associated with an average decrease in active abduction of 0.26° (95% CI, -0.46 to -0.07; p = 0.007) and forward flexion of 0.39° (95% CI, -0.61 to 0.16; p = 0.001); thus, younger patients were associated with more motion according to both active abduction and forward flexion as compared with older patients.

Table 4.

Association of age on rTSA outcomes: incremental difference for every 1 additional year in age on each outcome score and ROM measurement

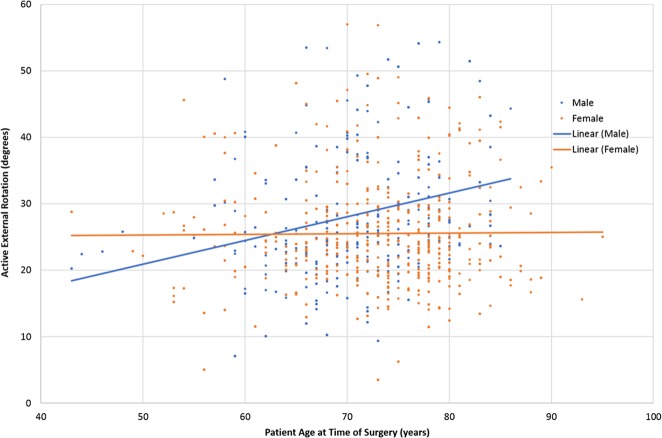

Interestingly, a combined interaction effect between age and gender was found only with active external rotation (p = 0.009), although active external rotation is not independently associated with age or gender. Younger age in men was associated with less active external rotation, whereas older age was associated with more active external rotation (β0 [intercept] = 11.029, β1 [slope for age variable] = 0.281, p = 0.009; Fig. 1). Conversely, women achieved no difference in active external rotation after rTSA, regardless of age at the time of surgery (β0 [intercept] = 34.135, β1 [slope for age variable] = -0.069, p = 0.009).

Fig. 1.

Average clinical improvement in active external rotation changes with patient age differently between male and female patients undergoing rTSA.

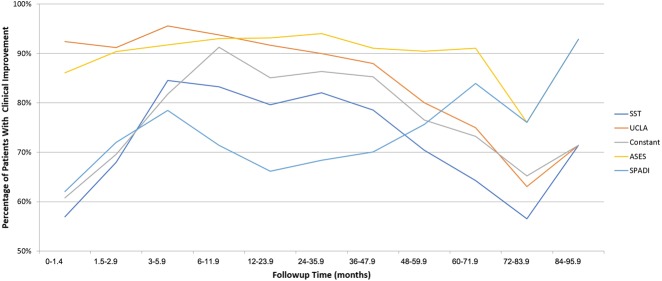

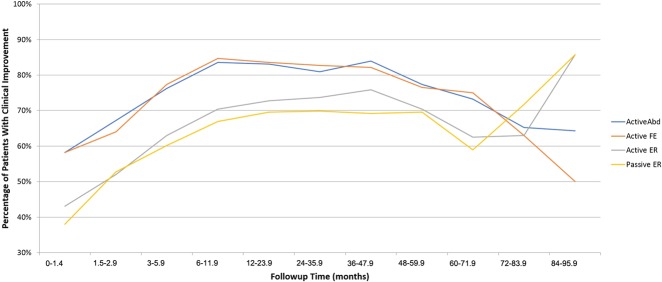

Regarding the rate of clinical improvement, full improvement in outcome scores was reached between 6 and 12 months after rTSA, as determined by a plateau in which 80% of patients experienced pre- to postoperative improvement for each of the five outcome scoring metrics (Fig. 2). Additionally, full improvement in ROM was reached between 6 and 12 months after rTSA, as determined by a plateau in which two-thirds of patients experienced pre- to postoperative improvement for each of the four ROM measurements (Fig. 3), respectively. For both the clinical metrics (Fig. 2) and the ROM measurements (Fig. 3), most improvement occurred within the first 6 months. Regarding the rate of improvement for the clinical metric scores, more than two-thirds of patients achieved clinical improvement for each outcome scoring metric by 6 months followup with some differences between metrics (Fig. 2). The UCLA and ASES scoring metrics were more consistent over the followup duration, whereas the SST, Constant, and SPADI were more variable and changed more with followup duration. Regarding the rate of improvement for the ROM measurements, more than two-thirds of patients achieved clinical improvement for each ROM measurement by 12 months followup. However, the percentage of patients with clinical improvement in active abduction and active forward flexion was generally greater than the percentage of patients with clinical improvement in both active and passive external rotation, regardless of followup duration.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of patients undergoing rTSA experiencing clinical improvement, as quantified by five outcome scoring metrics, varies with followup time, where the majority of improvement occurs in the first 12 months after surgery.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients undergoing rTSA experiencing clinical improvement, as quantified by four ROM measurements, varies with followup time, where the majority of improvement occurs in the first 12 months after surgery. Abd = abduction; FE = forward flexion; ER = external rotation.

Discussion

Differences in gender and age at the time of surgery have been previously documented for many orthopaedic procedures and have been previously demonstrated to be associated with differences in outcomes and also patient exceptions of clinical improvement [4, 6, 8, 18]. However, no study has previously evaluated any association of gender and age at the time of surgery with outcomes after rTSA. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate relationships between gender and age at the time of surgery with multiple different patient-reported and functional outcomes after rTSA, because this understanding may help physicians establish more reasonable patient expectations. The use of a linear mixed effects statistical model evaluating the outcome metric scores and active ROM measurements from 660 patients with 2 years minimum followup demonstrates that gender differences are associated with changes in clinical outcomes after rTSA. Specifically, men were associated with better outcome scores than women for all five metrics and greater ROM for all measurements except active external rotation. Additionally, age at the time of surgery was associated with differences in clinical outcome scores after rTSA, but to a lesser degree than gender, in which each 1-year increase in age was associated with improvement in ASES and SPADI metric scores but a decrease in ROM as measured by active abduction and active forward flexion. Additionally, a combined interaction effect was noted between age and gender for active external rotation, in which younger men were associated with less active external rotation and older men were associated with more active external rotation; no such difference was observed in active external rotation for women, regardless of age at the time of surgery.

This study has several limitations. One limitation is the number of data points acquired at the later time points (Table 1): 1083 of 2014 (54%) of the clinical reports occurred in the first 2 years of followup and 1897 of 2014 (94%) occurred in the first 5 years of followup. Future work should analyze additional patients with longer term followup to confirm these results related to the reliability of clinical improvement achieved with rTSA. However, it should be noted that the use of the linear mixed effects model largely mitigates this limitation because this statistical method analyzes changes in clinical metrics and ROM measurements across time and is flexible regarding repeated measures. Specifically, the linear mixed effects model does not require the same number of followup visits for each patient, permitting time to be analyzed as a continuous measure rather than at fixed points. Another potential limitation is the involvement of 13 surgeons contributing to the registry, which introduces variability into the physical ROM assessment; we attempted to control for this limitation by standardizing patient position and using a goniometer. In some situations, the implanting surgeons evaluated and scored their own patients; as such, there is a potential for bias in the outcome metrics and ROM measurements at each followup visit. Another limitation of this study is the inclusion criteria used for rTSA, which was performed for patients with cuff tear arthropathy or osteoarthritis with rotator cuff tear. Revisions and rTSA performed for other diagnoses, including rheumatoid arthritis and proximal humeral fractures, were excluded from our analysis. Although the indications used in our study are the most common for rTSA, it should be noted that our findings related to the rate and magnitude of clinical improvement after rTSA and also the effect of age and gender on clinical improvement may not be applicable to other indications for rTSA. One final limitation is the differing techniques used with this single rTSA prosthesis as it relates to repair (or no repair) of the subscapularis. We made no attempt to split the rTSA cohort based on subscapularis repair or any other surgical technique or surgical/patient factor (eg, rotator cuff status, body mass index, cemented versus press-fit, implants sizes, complications, etc). In addition to these subcohort analyses, future work should also incorporate use of a quality-of-life health survey to assess baseline health status and improvement.

Although the linear mixed effects model demonstrated better outcomes for men, it should be noted that these differences are in some instances less than the minimally clinical important difference (MCID) associated with each of the analyzed clinical outcome metrics for rTSA. Simovitch et al. [14] recently analyzed the MCID associated with different clinical metrics for rTSA and reported they were 10.3 ± 3.3 for the ASES, -0.3 ± 2.8 for the Constant, 7.0 ± 0.8 for the UCLA, 1.4 ± 0.5 for the SST, and 20.0 ± 3.9 for the SPADI metric, respectively. Thus, the gender effect exceeded the MCID for only the Constant and SST scoring metrics. The linear mixed effects model also demonstrated ROM differences for both gender and age, and at least for gender, these differences were all greater than the MCID for each ROM with rTSA. Simovitch et al. [14] reported the MCID associated with different ROM measurements for rTSA to be -1.9° ± 4.9° for active abduction, -2.9° ± 5.5° for active forward flexion, and -5.3° ± 3.1° for active external rotation. Thus, the gender effect exceeded the MCID for all three of these active ROM measurements with rTSA.

Older age was associated with improved ASES and SPADI scores but was also associated with lower abduction and forward flexion. We compared the 1-year incremental influence of age identified by the linear mixed effects model for each outcome metric and ROM measurement relative to the aforementioned MCID thresholds reported by Simovitch et al. [14]. We found the 1-year incremental age effect to be a small (approximately 1.5%) proportion of the MCID for the ASES and SPADI scores but a larger proportion (approximately 13.5%) of the MCID for active abduction and forward flexion. Based on this relative difference, we conclude that rTSA appears to reliably provide clinical improvement as quantified by these clinical outcome metrics for a wide range of ages at the time of surgery with greater age being associated with less function.

We determined that younger men were associated with less active external rotation, older men had more active external rotation, and there was no difference in active external rotation for women, regardless of age at the time of surgery. The reasons for this finding are unclear, but it is likely related to a different cause/severity of posterior rotator cuff injury in younger men relative to women and older men. Active external rotation is unpredictable after rTSA [2, 3, 11, 13-15]. By 12 months after rTSA, pre- to postoperative improvements in active external rotation were achieved by more than two-thirds of patients. However, the variability in magnitude of clinical improvement was substantial with an average of 21° ± 24° for all patients at latest followup with no difference in active external rotation between men and women. The use of the linear mixed effects statistical model identified a previously unreported combined interaction effect between age and gender for active external rotation. Future work should identify whether younger men receiving rTSA experience more severe traumatic injuries or extensive posterior rotator cuff deficiencies compared with other patient demographic cohorts receiving rTSA.

Men and women both experienced a plateau in clinical improvement for each of the five outcome metric scores and for each of the four active ROM measurements between 6 and 12 months after rTSA. Additionally, we observed that most of the improvement in outcome metric scores and ROM occurred in the first 6 months. Few clinical studies have described the effect of gender or age on outcomes after rTSA, and we identified no studies that evaluated any association between gender or age and the rate of clinical improvement after rTSA. For aTSA, Jawa et al. [6] reported no difference in clinical outcomes based on gender, but they stated that gender played a role in patient expectations and the reasons for pursuing surgery. Men valued return to sport, whereas women prioritized their ability to return to managing their daily activities and chores. As a result, gender differences in expectations after surgery may affect functional outcomes differently. More unmet expectations may lead to decreased functional outcomes, whereas more expectations satisfied may lead to better functional outcomes. Henn et al. [4] reported gender differences regarding gender-based preoperative expectations with women wanting an “improved ability to drive” and “maintenance of psychological well-being.” Levy et al. [8] reported on the rate of improvement differences between patients undergoing aTSA and those undergoing rTSA at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and at 2 years and demonstrated that patients undergoing rTSA at 3 months experienced 85% of the pain relief that they would experience by 2-year followup. Additionally, they reported that at 6 months, patients undergoing rTSA experienced 72% to 91% of the functional improvement that they would experience by 2-year followup. Finally, Levy et al. [8] noted several false plateaus for patients undergoing rTSA before 2 years followup and stated that improvement in some outcomes may occur after 2 years, which was the endpoint of their analysis. Our study analyzed patients up to 96 months and we observed full improvement by 12 months followup with some variations in plateaus depending on the clinical metric or ROM measurement being evaluated with the majority of improvement occurring in the first 6 months.

This large-scale clinical study of 660 patients demonstrates that both men and women of a wide range of ages at the time of surgery reliably experience clinical improvement after rTSA. Gender and age at the time of surgery were associated with some differences in rTSA outcomes as quantified by multiple scoring metrics and ROM measurements. When controlling for age, men were associated with better outcomes according to all five metrics and more motion according to three of four ROM measurements as compared with women. When controlling for gender, older patients had better outcomes, according to the ASES and SPADI, whereas younger patients had more motion, according to both active abduction and forward flexion. Finally, a combined interaction effect between age and gender was observed for active external rotation, in which younger men achieved less active external rotation and older men were associated with more active external rotation. These results demonstrate rTSA outcomes differ for men and women and for different patient ages at the time of surgery, knowledge of these differences, and also the timing of improvement plateaus in outcome metric scores and ROM measurements can both improve the effectiveness of patient counseling and better establish accurate patient expectations after rTSA. Future work is required to address the limitations of this study and to better quantify the relationships between age and gender after rTSA.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank each of the clinical coordinators and physical/occupational therapists at each site who helped to collect these patient outcome measures and also rehabilitate the patients in this study.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (RWS, EVC, RJF) certify that they are current consultants for Exactech Inc (Gainesville, FL, USA). One or more of the authors (P-HF, TW, JDZ) have received royalties of greater than USD 1 million on the product discussed in this study during the study period (March 2007 to March 2014). One or more of the authors (CB, CR) are employees of Exactech Inc.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Exactech Inc, Gainesville, FL, USA; University of Florida, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Gainesville, FL, USA; and NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: The Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:527–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, Saleem A, Mighell M, Vasey M. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1697–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henn RF, 3rd, Ghomrawi H, Rutledge JR, Mazumdar M, Mancuso CA, Marx RG. Preoperative patient expectations of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:2110–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jawa A, Dasti U, Brown A, Grannatt K, Miller S. Gender differences in expectations and outcomes for total shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang JJ, Toor AS, Shi LL, Koh JL. Analysis of perioperative complications in patients after total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1852–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy JC, Everding NG, Gil CC, Jr, Stephens S, Giveans MR. Speed of recovery after shoulder arthroplasty: a comparison of reverse and anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1872–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1297–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.RCore Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed November 11, 2017.

- 11.Routman HD, Flurin PH, Wright TW, Zuckerman JD, Hamilton MA, Roche CP. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty prosthesis design classification system. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013).2015;73(Suppl 1):S5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CD, Guyver P, Bunker TD. Indications for reverse shoulder replacement: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stechel A, Fuhrmann U, Irlenbusch L, Rott O, Irlenbusch U. Reversed shoulder arthroplasty in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:367–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simovitch R, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman J, Roche C. Quantifying success after total shoulder arthroplasty: the minimal clinically important difference. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017. Nov 18. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O'Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1476–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1476–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf JM, Cannada L, Van Heest AE, O'Connor MI, Ladd AL. Male and female differences in musculoskeletal disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]