Abstract

Previously, we identified early developmental exposure to growth hormone (GH) as the requisite organizer responsible for programming the masculinization of the hepatic cytochromes P450 (CYP)-dependent drug metabolizing enzymes (Das, et al. 2014, 2017). In spite of the generally held dogma that mammalian feminization requires no hormonal imprinting, numerous reports that the sex-dependent regulation and expression of hepatic CYPs in females are permanent and irreversible would suggest otherwise. Consequently, we selectively blocked GH secretion in a cohort of newborn female rats, some of whom received concurrent GH replacement or GH releasing factor. As adults, the feminine circulating GH profile was restored in the treated animals. Two categories of CYPs were measured. The principal and basically female specific CYP2C12 and CYP2C7; both completely and solely dependent on the adult feminine continuous GH profile for expression, and the female predominant CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 whose expression is maximum in the absence of plasma GH, suppressed by the feminine GH profile but more so by the masculine episodic GH profile. Our findings indicate that early developmental exposure to GH imprints the inchoate CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 in the differentiating liver to be solely dependent on the feminine GH profile for expression in the adult female. In contrast, adult expression of CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 in the female rat appears to require no GH imprinting.

Keywords: cytochromes P450, development, feminization, growth hormone, imprinting, sexual dimorphism

1. Introduction

Sexual dimorphisms of some dozen or more hormone- and drug metabolizing constituent cytochromes P450 (CYPs) observed in rats, humans and other species examined (Shapiro, et al. 1995) is defined by two characteristics. 1) Following puberty, males and females express different CYP profiles. In some cases, the isoforms may be sex exclusive as is the case of CYP2C11 and CYP3A2 expressed only in males, or CYP2C12, only expressed in female rats (Shapiro et al. 1995; Waxman & Holloway 2009). More commonly, isoforms are sex predominant: e.g., women express greater levels of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 (Thangavel, et al. 2011, 2013) while in the case of mice, males express greater levels of CYP2D9 (Davey, et al. 1999; Waxman & Holloway 2009). 2) The sexual dimorphisms in CYP expression are determined by sex differences in the circulating growth hormone (GH) profiles in adulthood. More specifically, it is not the amount of circulating GH per se, but rather, the sexually dimorphic ultradian rhythms in plasma GH that regulate sex-dependent isoforms of CYP. Although there are some variations between species, in general, the adult male GH profile is referred to as “episodic” and is characterized by several daily bursts of hormone separated by lengthy undetectable or barely detectable GH concentrations. In contrast, the adult female GH profile is considered “continuous,” as there are far more secretory bursts, often at lower amplitudes, of the hormone separated by briefer interpulse periods, often containing measurable levels of GH (Shapiro et al. 1995). Consequently, the male CYP archetype is a result of the masculine episodic GH profile, whereas the phenotypic female pattern of CYP expression is dependent on the feminine continuous GH profile (Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Agrawal & Shapiro 2000).

Most, if not all, sexual dimorphisms are a result of developmental hormonal imprinting. Hormonal imprinting refers to a biological process in which the target tissue becomes responsive to the hormone. During the initial exposure, the hormone irreversibly reprograms the development of the affected tissue so as to permanently alter some functional aspect normally responsive to the hormone and often establishing a sexual dimorphism (Csaba 2008). Moreover, the tissue is programmable for only a brief developmental period, after which time the tissue becomes permanently unresponsive to imprinting (Goldman 1970, Feder 1981, Shapiro 1985). Imprinting alone, however, is generally insufficient to ensure the expression of the programmed function. Accordingly, expression of the affected function requires both imprinting and activation, the latter being a reversible process, but required to express the imprinted function. For example, perinatal testosterone or one of its metabolites is required to permanently ‘wire’ or imprint the male brain to exclusively express masculine sexual behavior. However, the brain has to be stimulated or activated in adulthood by the same hormone to elicit the imprinted male sexual behavior. Both imprinting and activation are required for normal masculine sexual behavior (Shapiro et al. 1980, Feder 1981).

We previously reported that adult male rats and men cannot be induced (regardless of GH treatment) to express the normal female profile of CYPs (Pampori & Shapiro 1999; Thangavel, et al. 2004; Dhir, et al. 2006; Thangavel & Shapiro 2008) nor can adult female rats or women be induced to fully express the masculine CYP profile (Pampori, et al. 2001; Dhir et al. 2006; Thangavel, et al. 2006; Thangavel & Shapiro 2007). The response to each of the dozen or so sex- dependent rat CYP isoforms to GH regulation has been described (Thangavel & Shapiro 2008; Das, et al. 2013; Banerjee, et al. 2015). If CYP enzymes were not imprinted, then irrespective of sex, the same adult treatment should produce the same CYP expression levels in males and females. As this is not the case, we had concluded that the sex differences in adult expression profiles of CYPs are permanent and irreversible, a condition demonstrating imprinting. Because an adult tissue/function is apt to be responsive to the same hormone by which it was imprinted (Csaba 2008), we proposed, for the first time, that like androgens, perinatal GH is a developmental organizer required for the normal expression of adult CYP-dependent drug metabolism. In fact, we recently reported that adult expression of the principal male-specific CYP2C11 isoform in the rat is completely dependent on imprinting by developmental GH. In the absence of the perinatal hormone, CYP2C11 [comprising >50% of the total hepatic CYP content (Morgan, et al. 1985)] is permanently and irreversibly unresponsive to the inductive effects of the masculine episodic GH profile (Shapiro, et al. 1993; Das et al. 2014, 2017).

But what then of the female? The feminine hepatic CYP archetype, dependent on the continuous feminine GH profile, is very different from that expressed by the male. However, like the male, once established, the CYP profile in females is permanent and cannot be induced to the normal masculine CYP profile. Accordingly then, like the male isoforms, the female isoforms appear to be irreversibly imprinted. In the case of the more widely examined sexual dimorphisms of the reproductive system, testosterone or its metabolites masculinize the reproductive structures as well as the brain (Goldman 1970, Feder 1981, Shapiro 1985). The absence of androgens in the developing female allows for the expression of the so-called “default” feminine program. In contrast, however, both perinatal male and female rats, humans as well as other mammalian species (Cornblath, et al. 1965; Laron, et al. 1966; Oliver, et al. 1982; Kacsoh, et al. 1989) secrete higher than adult-like levels of GH suggesting a developmental role for the hormone in both sexes. In the present study, we examine, likely for the first time, a possible role for neonatal GH in irreversibly predetermining adult expression of the typical CYP isoforms found in females.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal experimentation

Rats [Crl:CD (SD) BR] were housed in the University of Pennsylvania Laboratory Animal Resources facility under the supervision of certified laboratory animal medicine veterinarians and were treated according to a research protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University. Housing conditions, as well breeding and treatment protocols, were reported previously (Shapiro, et al. 1989; Pampori, et al. 1991a). Basically, neonatal female rat pups were injected, sc, with either of 2 of 5 possible treatments. 1) Monosodium glutamate (MSG), 4mg/g b wt on alternate days, starting within 24 h of birth for a total of 5 injections. 2) An equivalent amount of the MSG NaCl diluent. 3) Recombinant rat GH (2IU/mg), 20μg/100g b wt, twice/d for the first 12 days of life. 4) An equivalent amount of the GH bicarbonate diluent. 5) Recombinant human growth hormone releasing factor (GRF, 1–29), 2μg/100g b wt, twice/d for the first 12 days of life. Accordingly, control pups received treatments 2 and 4; MSG pups received treatments 1 and 4; GH pups received treatments 2 and 3; MSG + GH pups received treatments 1 and 3; GRF pups received treatments 2 and 5; and MSG + GRF pups received treatments 1 and 5. (Control pups were not treated with the GRF PBS diluent, since like the MSG and GH diluents, it produced no observable effect [our unreported observation].) GH and GRF were purchased from Dr. A. F. Parlow, National Hormone and Peptide Program, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA. Body weights and Lee indices (Lee 1928) were determined as previously reported (Shapiro et al. 1989; Pampori et al. 1991a).

2.2. Growth hormone determinations

Plasma GH concentrations were determined by a sensitive sandwich ELISA method as described previously (Das et al. 2013). Procedures for collecting unstressed postnatal plasma as well as adult serial blood sampling for GH determinations have been reported (Pampori, et al. 1991b; Banerjee et al. 2015).

2.3. Hormonal conditions

To replicate the circulating feminine continuous GH profile, adult (~30 weeks of age) female rats neonatally treated with MSG, MSG + GH, or MSG + GRF were implanted, intraperitoneally, with osmotic pumps (Alza, Palo Alto, CA) designed to deliver 1μl/h of sufficient levels of rat GH to produce an expected secretory rate of 15μg GH / kg b wt / h for 6 days (Pampori & Shapiro 1996). All remaining rats were similarly implanted with rat GH vehicle-containing osmotic pumps. At the end of 6 days when the rats were necropsied, the pumps were removed, and the measured residual amounts of GH were used to calculate an actual delivery rate of rat GH of 16.5 ± 0.3 μg / kg b wt / h (mean ± sd), an appropriate level to produce a physiologic-like circulating female GH profile (Pampori & Shapiro 1996, 1999).

2.4. RNA isolation

Total RNA from liver tissue was isolated using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) purified with the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit and treated with DNase I in order to remove any trace of genomic DNA using RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations and purity were determined by u.v. spectrophotometry (A260/280>1.8 and A260/240>1.7) and integrity was verified by the intensities of 28S and 18S rRNA bands on a denaturing agarose gel visualized on a FluorChem IS-8800 Imager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

2.5. Quantitative RT-PCR

Cyp2C12, Cyp2C6, Cyp2E1, Cyp2C11, and Cyp2C7 gene expressions were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using SYBR green on an Applied Biosystem 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). RNA isolation, concentration, and purity determination were performed as mentioned earlier. cDNA synthesis was completed using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Life Technologies) as per instructions with appropriate no- RT (-RT) and non-template controls. PCR primers for Cyp2C12 and Cyp2C11 (Ahluwalia et al. 2004), Cyp2C7 (Choi et al. 2011), Cyp2C6 (Banerjee, et al. 2013), Cyp2E1 (Matsunami, et al. 2011) and β-actin (Das et al. 2013) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA). Gene expression was determined using β-actin as the housekeeping gene on an Applied Biosystem step-one plus q-PCR instrument as per the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Life Technologies).

2.6. Western blotting

Whole cell lysate protein (Pollenz, et al. 1998; Garcia, et al. 2001) were assayed for individual CYP isoforms by western blotting (Pampori, et al. 1995). Briefly, 50μg of protein were electrophoresed on 0.75mm-thick SDS-polyacrylamide (10–12%) gels and electro blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were probed with monoclonal anti-rat CYP2C12 (a gift from Dr. Marika Ronnholm, Huddinge University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden), anti-rat CYP2C7 (a gift from Dr. An Huang, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY), monoclonal anti-rat CYP2C6 and albumin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), anti-rat CYP2E1 (a gift from Dr. F. Peter Guengerich, Vanderbilt University, School of Medicine, Nashville, TN), and monoclonal anti-rat CYP2C11 (Detroit R&D, Inc., Franklin, MI) and detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp, Piscataway, NJ). Signals were normalized to a control sample repeatedly run on all blots and/or to the expression of β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MD). The protein signals were scanned and the densitometric units were obtained as integrated density values quantitated using a FluorChem IS-8800 Image (Alpha Innotech) software supplied with the gel documentation system.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The ultradian patterns in plasma GH concentrations were analyzed with the aid of the Cluster analysis computer program (Veldhuis & Johnson 1986), as we have reported previously (Agrawal, et al. 1995; Dhir & Shapiro 2003). All data, including that obtained from the Cluster analysis program, were subjected to ANOVA and differences were determined using t statistics and the Bonferroni procedure for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Immediate and long-term suppression of GH secretion by neonatal MSG

In agreement with previous studies (Oliver et al. 1982; Kacsoh et al. 1989) as well as our own report (Banerjee et al. 2015), plasma GH levels in the control group were maximum the first few postpartum days of life, thereafter declining ~55% by 5 days of age and by ~85% from 11 through 15 days of age (Fig. 1). GH levels of the MSG-treated neonates at 2 days of age, which was often less than 24h after the first MSG injection, were normal. Thereafter, plasma GH concentrations declined 85 to 95% (postnatal day 5 through 11 days of age), to undetectable (15 days of age). In spite of the administration of exogenous GH during the first 12 days of life, plasma levels of the hormone in otherwise untreated pups were generally the same as controls. This seemingly unexpected finding could be explained by the presence of a functional hypothalamic-pituitary GH feedback loop in which the administered GH suppressed secretion of endogenous hormone (Oliver et al. 1982; Wehrenberg 1986). Concomitant administration of MSG and GH resulted in a general doubling of plasma GH concentrations as compared to controls. With the exception of 5 days of age, administration of GRF to otherwise untreated neonates, resulted in GH levels generally similar to that observed in controls and GH-alone treated neonates for the same possible reasons discussed above for the GH-alone treatment. In agreement with earlier reports that hypothalamic GRF normally stimulates GH synthesis and secretion in newborn rats (Cella, et al. 1985; Wehrenberg 1986), we found that neonatal administration of GRF to GH devoid MSG-treated pups resulted in normal-like plasma concentrations of GH for about the first week of life. Thereafter, and in agreement with identically treated male newborns (unreported observation), pituitary GH secretion was poorly responsive to GRF stimulation due to a possible MSG-induced progressive pituitary resistance to the hypothalamic hormone (Dhir, et al. 2002). With the discontinuance of exogenous hormone (i.e., GH or GRF) replacement after 12 days of age, plasma GH levels were understandably undetectable in all the MSG-treated (i.e., MSG alone, MSG + GH and MSG + GRF) pups.

Figure 1.

Plasma GH of female rat pups treated solely or with a combination of MSG, GH, GRF or diluents. Commencing on the day of birth (D. 1), female neonates were injected, s.c., with either MSG, GH, MSG + GH, GRF, MSG + GRF or diluents (CONTROL) for a treatment period and at a dose described under Materials and Methods. Results are presented as the mean ± SD of at least 6 pups/group. * P < 0.01 vs CONTROL; † P < 0.01 vs. MSG treatment alone.

Adult plasma GH profiles are presented as schematic representations of the actual circulating profiles (Fig. 2). The control rats secreted the typical adult feminine profile (Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Banerjee et al. 2013) characterized by frequent low amplitude pulses (compared to males) resulting in peaks of ~100 ng/ml, followed by short-lived ~25 min troughs that were always measurable and averaged ~20 ng/ml. Whereas the GH alone treatment had no effect on the amplitudes of the plasma GH pulses, the baseline (trough height) was about twice the concentration of the control profile (P<0.01). Neonatal GRF alone had the opposite effect of GH alone on the adult circulating GH profile. The baseline concentrations of the feminine GH profile in the GRF treated rats were similar to controls, whereas the pulse amplitudes were reduced by ~30% (P<0.01). In contrast to controls and the hormone alone treatments, none of the adult neonatally MSG-treated rats (i.e., MSG alone, MSG + GH and MSG + GRF) had any measurable plasma GH (>0.125 ng/ml) during the 7 continuous hours of serial sampling.

Figure 2.

Circulating GH levels obtained from individual, undisturbed catheterized adult (~30 weeks of age) female rats neontally treated with either MSG, GH, MSG + GH, GRF, MSG + GRF or diluents (CONTROL) for 8 continuous hours at 15 minute intervals. Similar results were obtained from 4 to 5 additional animals in each treatment group. See Materials and Methods for details of neonatal treatments.

3.2. Neonatal GH, but not GRF, mitigates MSG-induced adult obesity

Neonatal exposure to GH alone or GRF alone had no effect on body weights when determined at 11 and 35 weeks of age (Fig. 3, top). In contrast, female pups treated with MSG alone or MSG + GRF weighed significantly more than controls at the same age. However, the body weights of MSG treated pups concomitantly administered GH were normal (11 weeks of age) or statistically intermediate of that of controls and MSG-alone treated rats (35 weeks of age). The elevated body weights of the affected females were most likely due to an abnormal deposition of fat as reflected by their Lee indices.

Figure 3.

Neonatal GH effects on maturational body weight gains (top) and Lee indices (bottom). Results are presented as the means ± SD of at least 15 rats/group. See Materials and Methods for details of neonatal treatments. Body weights: *P < 0.01 vs. CONTROL; † P < 0.01 vs. MSG treatment alone. Lee Indices: see Results for statistical significances.

The Lee index is a measure of obesity; the higher the value, the greater the obesity. At all ages measured (7–35 weeks of age), the Lee index of the neonatally MSG-treated rats was significantly (P<0.01) greater than age-matched controls (Fig. 3, bottom); this is not likely a result of overeating (Olney 1969), but rather a consequence of thermoregulation of a lower than normal body temperature and a general lethargy (Tokuyama & Himms-Hagen 1986) preventing normal (musculoskeletal) body weight gain. The Lee indices of the GH-alone and GRF-alone treated rats were no different from controls. In spite of the absence of any detectable plasma GH, adult rats neonatally exposed to both MSG and GH had Lee indices that were intermediate (P<0.01) between controls and MSG alone, suggesting that the hormone imprints the ‘obesity set point’ attenuating the effects of both neonatal and adult GH depletion observed in MSG-alone- treated rats. The ineffectiveness of neonatal GRF to prevent the MSG-induced obesity may be due to the fact that the hypothalamic hormone increased plasma GH concentrations for fewer days than required to imprint “obesity centers” in the brain (Fig. 1).

3.3. Renaturalization of the circulating feminine GH profile in adult female rats neonatally administered MSG

Although rarely reported, we believe it is always valuable to determine the plasma GH profiles resulting from the administration of the hormone. Consequently, in order to restore the feminine GH profile, those adult rats that had no detectable level of circulating GH due to neonatal treatments (Fig. 2), MSG-alone, MSG + GH and MSG + GRF, were implanted with rat GH-containing osmotic pumps and the resulting profiles are schematically presented in Fig. 4. In vivo administration of GH produced feminine-like plasma profiles characterized by frequent pulses separated by short-lived trough concentrations that were always measurable. There were, however, some differences in the GH profiles between the various groups. Not surprisingly, the continuous release of the same concentration of GH by the osmotic pumps produced more uniform profiles with lower pulse amplitudes and a higher interpulse baseline than observed in controls. The mean (x̄ ± sd) plasma concentration (ng/ml) of GH for the 7h collection period was 46.4 ± 34.9 for controls, 46.7 ± 8.5 for MSG + GH and 42.2 ± 7.2 for MSG + GRF rats.

Figure 4.

Plasma levels of circulating GH in adult (~30 weeks of age) female rats neonatally treated with MSG, MSG + GH, MSG + GRF or diluents (CONTROL) implanted with either rat GH or diluent containing osmotic mini pumps. Plasma levels of circulating GH were obtained from individual, undisturbed catheterized adult females for 7 continuous hours at 15 min intervals. Peritoneally implanted osmotic mini pumps were set to continuously deliver 15 μg of rat GH/kg bd wt / hr or just GH diluent in CONTROL rats. Similar results were obtained from 3 to 4 additional animals in each treatment group. See Materials and Methods for all treatment details. (Note different scales on the y-axes.)

Although the MSG-alone treated rats received the same GH treatment, the mean concentration of the hormone (22.9 ± 6.5) was half the amount observed in the other treatment groups. Regardless of the variations in the resulting circulating GH profiles, these same profiles replicated in hypophysectomized (HYPOX) female rats were fully capable of restoring normal-like levels of female-dependent CYP2C12, CYP2C7, CYP2A1, and CYP2C6 (Pampori & Shapiro 1996, 1999). Apparently, the sole “signal” in the feminine GH profile required for full expression of female dependent CYPs is a minimal, continuous (uninterrupted) presence of the hormone in the circulation. There are no pulse requirements and the mean concentration of as little of 3 to 6% of physiologic are capable of inducing substantial levels of the isoforms (Pampori & Shapiro 1996, 1999).

3.4. Endogenous developmental GH imprints dependence of CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 expression on the feminine GH profile

CYP2C12 (Fig. 5, top) and CYP2C7 (Fig 5, bottom) are the two isoforms most dependent on the continuous feminine GH profile for their expression. In the absence of the feminine GH profile (i.e., HYPOX), CYP2C12 is completely undetectable and CYP2C7 expression is reduced to barely detectable levels (Waxman & Chang 1995; Pampori & Shapiro 1996, 1999; Thangavel & Shapiro 2008). In spite of these earlier findings using HYPOX rats in otherwise untreated females (i.e., no neonatal treatments), females neonatally exposed to MSG (i.e., MSG-alone MSG + GH and MSG + GRF) expressed considerable concentrations of the two isoforms (Fig. 5); this occurring in the absence of any detectable circulating levels of GH (Fig. 2). Females concurrently treated as neonates with either GH or GRF along with MSG expressed about twice the concentrations of CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 as rats treated with MSG-alone, or about 70% of control levels. Adult restoration of the feminine circulating GH profile (Fig. 4) increased hepatic CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 (mRNA and protein) concentrations to normal, control-like levels in adults, neonatally treated with MSG-alone. Renaturalization of the feminine GH profile to adults, neonatally exposed to both MSG and GH or GRF had no further inductive effects on the already high levels of CYP2C12 and CYP2C7.

Figure 5.

Neonatal GH effects on adult hepatic expression of female specific CYP2C12 (top) and female-predominant CYP2C7 (bottom). Hepatic CYP isoform levels (mRNA and protein) were determined in adult female rats neonatally treated solely or with a combination of vehicles (e.g. CONTROL), MSG, GH or GRF (upper case labels on x-axis). Half of the animals in groups neonatally exposed to MSG (i.e., MSG, MSG + GH and MSG + GRF) were implanted with rat GH releasing osmotic mini pumps to restore the continuous feminine GH profile (Fig. 4). All other animals received GH-vehicle releasing osmotic mini pumps (lower case labels on x-axis). Results are presented as a percentage of mRNA or protein in CONTROL rats arbitrarily designated as 100%. Values are means ± SD of at least 6 rats / data point. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. CONTROL; † P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 compares adult vehicle treatment of neonatal MSG + GH and MSG + GRF with vehicle treated MSG alone; ##P < 0.01 compares adult GH treatment with vehicle treatment of rats exposed to the same neonatal treatment. See Materials and Methods for all treatment details.

3.5. Adult CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 expression is independent of neonatal GH imprinting

Although titulary female-predominant isoforms, the sex differences in CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 are minimal compared to CYP2C12 and CYP2C7. Moreover, unlike CYP2C12 and CYP2C7, GH suppresses (the male profile more so than the female profile) CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 expression so that HYPOX maximizes expression of the isoforms eliminating any sex differences (Waxman, et al. 1989; Waxman, et al. 1990; Westin, et al. 1990; Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Agrawal & Shapiro 2000).

Adult rats neonatally treated with MSG (i.e., MSG-alone, MSG + GH or MSG + GRF) and subsequently implanted with vehicle-containing mini pumps, expressed mRNA and protein levels of CYP2C6 that were either no different (mRNA) or somewhat higher (protein) than controls (Fig. 6, top). Restoration of the continuous feminine GH profile to these GH-devoid rats, reduced CYP2C6 concentrations, particularly at the protein level, in all groups. The findings suggest, in agreement with earlier reports using HYPOX rats (Westin et al. 1990; Pampori & Shapiro 1996) that the feminine GH profile has a small suppressive effect on CYP2C6 expression in female rats which is independent of developmental GH imprinting. The significantly lower adult expression levels of CYP2C6 in the rats neonatally treated with GH- alone may be explained by the reported (Pampori & Shapiro 1996) suppressive effect of elevated trough concentrations of GH in the resulting circulating feminine profile (Fig. 2).

Figure 6.

Neonatal GH effects on adult hepatic expression of female-predominant CYP2C6 (top) and CYP2E1 (bottom). Hepatic CYP isoform levels (mRNA and protein) were determined in adult female rats neonatally treated solely or with a combination of vehicles (e.g. CONTROL), MSG, GH or GRF (upper case labels on x-axis). Half of the animals in groups neonatally exposed to MSG (i.e., MSG, MSG + GH and MSG + GRF) were implanted with rat GH releasing osmotic mini pumps to restore the continuous feminine GH profile (Fig. 4). All other animals received GH-vehicle releasing mini pumps (lower case labels on x-axis). Results are present as a percentage of mRNA or protein in CONTROL rats arbitrarily designated as 100%. Values are means ± SD of at least 6 rats / data point. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. CONTROL; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 compares adult GH treatment with vehicle treatment of rats exposed to the same neonatal treatment. See Materials and Methods for all treatment details.

The same neonatal treatments produced similar effects on CYP2E1 expression as CYP2C6, although the actual changes in magnitude were greater in the former. Rats neonatally treated with MSG (i.e., MSG-alone, MSG + GH or MSG + GRF) and implanted as adults with vehicle-containing mini pumps expressed CYP2E1 (mRNA and proteins) at concentrations considerably above controls (Fig. 6, bottom). Restoration of the feminine circulating GH profile to these GH-depleted rats, reduced CYP2E1 concentrations to sub-control levels. Similar to findings observed in HYPOX rats (Waxman et al. 1989; Waxman et al. 1990), it would appear that the feminine GH profile normally suppresses CYP2E1 expression in adult female rats, a function that does not require neonatal GH imprinting. CYP2E1 expression levels in the adult females, neonatally administered GH-alone were significantly lower than controls, as was CYP2C6, and for possible similar reasons.

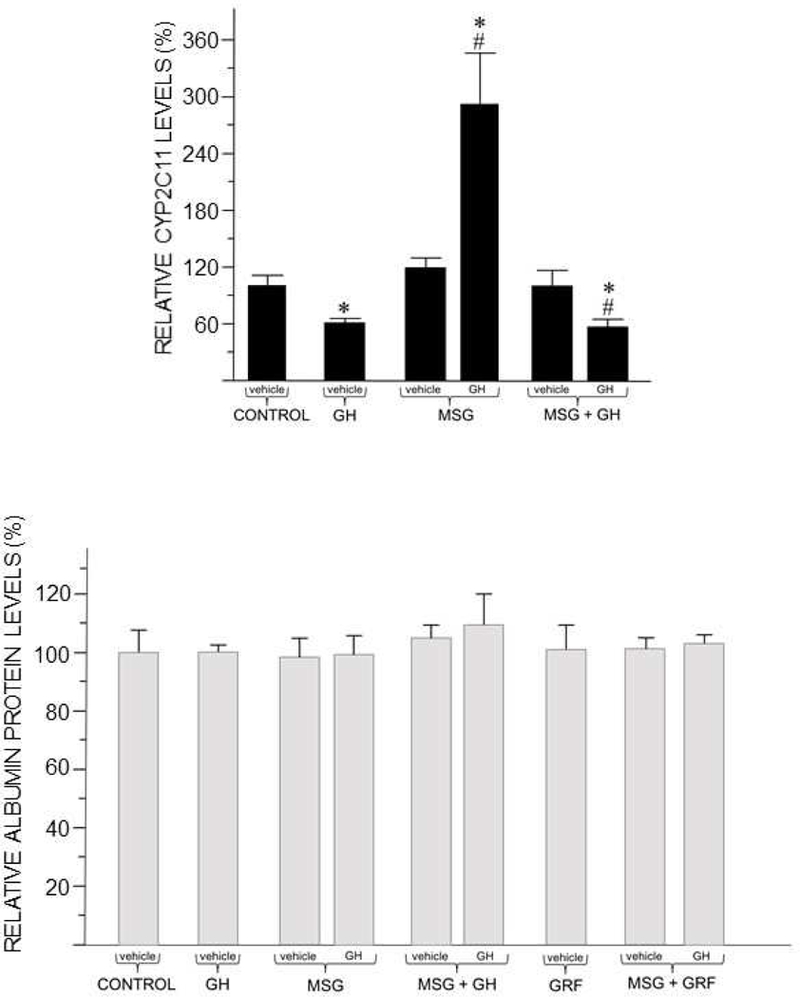

3.6. Neonatal GH irreversibly suppresses male-specific CYP2C11 expression in adult females without disrupting albumin expression

CYP2C11 is the predominant male-specific CYP isoform that is typically undetectable in intact female rats (Waxman & Chang 1995; Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Agrawal & Shapiro 2000). Although we were unable to consistently measure CYP2C11protein in the female livers, the use of qRT-PCR allowed us to measure, albeit at very low levels, CYP2C11 mRNA (Fig. 7, top). Adults neonatally treated with MSG (MSG-alone or MSG + GH), implanted with vehicle-releasing osmotic mini pumps expressed the same nominal concentrations of CYP2C11 mRNA as controls. However, when the feminine circulating GH profile was restored, only the neonatally MSG-alone treated rats (i.e., not imprinted by GH) responded with a 3-fold increase in transcript levels of the isoform. In contrast, the renaturalized feminine GH profile in adults neonatally administered MSG + GH significantly suppressed CYP2C11 mRNA expression to below control levels. In this regard, CYP2C11 induction in otherwise GH imprinted HYPOX or intact adult female rats is completely unresponsive to the naturally secreted (intact) or restored (in HYPOX) feminine GH profile (Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Pampori et al. 2001; Thangavel et al. 2006). Since the presence of neonatal GH (intact or MSG + GH rats) permanently blocks induction of CYP2C11 by the feminine GH profile, it would appear that developmental GH imprints the female liver to be permanently refactory to GH induction of male-specific CYP2C11.

Figure 7.

Neonatal GH effects on adult hepatic expression of male-specific CYP2C11 (top) and sex-independent albumin (bottom). Hepatic mRNA levels of CYP2C11 and protein levels of albumin were determined in adult female rats neonatally treated with various regimens of vehicles (e.g. CONTROL), MSG, GH or GRF (upper case labels on x-axis). Half of the animals in groups neonatally exposed to MSG were implanted with rat GH releasing osmotic mini pumps to restore the continuous feminine GH profile (Fig. 4). All other animals received GH-vehicle releasing mini pumps (lower case labels on x-axis). Results are presented as a percentage of mRNA or protein in CONTROL rats artbitrarily designated as 100%. Values are means ± SD of at least 6 rats / data point. *P < 0.01 vs. CONTROL; #P < 0.01 compares adult GH treatment with vehicle treatment of rats exposed to the same neonatal treatment. See Materials and Methods for all treatment details. (CYP2C11 mRNA was not determined in GRF-alone and MSG + GRF treated rats.)

Our finding that adult expression levels of hepatic albumin, normally both sex and GH- independent (Sharma, et al. 2012), were unaffected by neonatal MSG and/or GH, and/or GRF indicates the selective effects of the neonatal treatments on adult CYP expression (Fig. 7, bottom).

4. Discussion

The normal adult female rat expresses maximal concentrations of female-predominant CYP2C7 and female-specific CYP2C12, the latter comprising >40% of the female liver’s total concentration of CYPs. In fact, of the half-dozen or so female-dependent CYP isoforms expressed in the female rat liver, only CYP2C7 and CYP2C12 are solely dependent on the continuous feminine GH profile. Following adult HYPOX, CYP2C12 becomes undetectable; CYP2C7 is reduced to trace levels, whereas remaining female-dependent isoforms (e.g., CYP2C6, CYP2E1) are in contrast to CYP2C7 and CYP2C12, elevated to various degrees. Renaturalization of the feminine continuous GH profile, but never the masculine profile, to HYPOX female rats restores CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 to fully intact levels, whereas other female- dependent CYPs are now reduced to intact levels (Waxman et al. 1989; Waxman et al. 1990; Pampori & Shapiro 1996, 1999).

Even though neonatal GH ablation (MSG-alone) produces a permanent elimination of the hormone from the circulation as seen following HYPOX (Das et al. 2014), we report here, in agreement with our earlier findings (Waxman et al. 1990; Agrawal & Shapiro 1997) that CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 expression are not abolished by neonatal GH depletion. In fact, in contrast to the profound loss of the two isoforms in adult HYPOX females, the CYPs are expressed in MSG-alone treated rats at ≥40% of normal levels; this is in spite of no detectable circulating GH as in HYPOX. Furthermore, the depletion of neonatal GH had no effect on the ability of the restored feminine GH profile to subsequently induce normal (100%) expression levels of CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 in adulthood. Lastly, adult restoration of the feminine GH profile to neonatally GH-depleted (MSG-alone) females resulted in a 3-fold increase in male- specific CYP2C11 mRNA, a response that is completely refractory in the normal neonatally GH exposed females (Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Thangavel et al. 2006). Consequently, the imprinting role of the neonatal GH on adult CYP expression in the female appears to be profoundly different from that observed in the male rat.

The ability of the adult male to express the principle male-specific CYP2C11 isoform is unequivocally dependent on neonatal GH imprinting. As untreated adults, the MSG treated male pups secrete no GH, and consequently, express no CYP2C11. In dramatic contrast to the adult HYPOX male, adult restoration of the masculine GH profile to neonatal MSG treated male rats is totally ineffective in activating the signal transduction pathway required for CYP2C11 expression, i.e., the activation, nuclear translocation and binding of STAT5b to the CYP2C11 promoter [as a possible result of MSG induced hypermethylation of the upstream GH-activated regulatory elements of the CYP2C11 gene (Das et al. 2014)], and thus, resulting in the permanent and irreversible repression of the isoform in the affected males (Shapiro et al. 1993; Das et al. 2017).

It should not be construed, however, that neonatal GH does not have an imprinting role in establishing the feminine pattern of CYP expression. Rather, under normal conditions (i.e., control females), neonatal GH appears to imprint the liver so that in adulthood, the expression of the major female isoforms, CYP2C12 and CYP2C7, are now solely dependent upon the continuous feminine GH profile. The complete absence of circulating GH (i.e., HYPOX) or exposure to the masculine episodic GH profile are ineffective in inducing CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 expression in normal females (Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Thangavel et al. 2006). In contrast, blocking neonatal GH imprinting by depleting the hormone with MSG, allows for a less rigid or promiscuous response characterized by GH independent and likely episodic GH induced CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 expression, while still allowing normal CYP responsiveness to the feminine GH profile (Fig. 5). Moreover, restoration of the feminine GH profile is capable of inducing male-specific CYP2C11 in the neonatal GH-depleted adult females; never observed in normal GH imprinted females (Pampori & Shapiro 1999; Pampori et al. 2001; Thangavel et al. 2006).

We have examined the imprinting effects of early developmental exposure to GH on the adult expression of two very different categories of female-dependent CYP isoforms. CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 are the principal female isoforms; the former is undetectable in males, while the latter is expressed at concentrations at least 3 to 5 times greater in females than males. Moreover, it is the continuous feminine GH profile that is solely requisite for maintaining the elevated levels of the two isoforms in females (Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Agrawal & Shapiro 2000; Pampori et al. 2001). In contrast, whereas CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 are expressed at statistically higher levels in females, the sex differences are minimal with females expressing ~20%, and no more than 70% greater concentrations of the isoforms than males. HYPOX causes an increase in hepatic CYP2E1 and CYP2C6 in both sexes, more so in males, erasing the sex differences, which is then completely restored by administration of the sex-dependent plasma GH profiles (Waxman et al. 1989; Pampori & Shapiro 1996; Agrawal & Shapiro 2000). Basically then, the sexual dimorphic expression (i.e., female predominance) of CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 is a consequence of their different sex dependent GH profiles. Whereas both hormone profiles are suppressive, the masculine episodic profile is more so, explaining the resulting maximum and equal expression levels in HYPOX rats of both sexes.

Our present CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 findings are in agreement with previous reports using HYPOX rats. Like HYPOX, adult females chemically void of plasma GH (i.e., MSG alone, MSG + GH and MSG + GRF; all implanted with diluent-releasing osmotic pumps) expressed the greatest above control levels of CYP2C6 and CYP2E1. Restoration of the feminine continuous GH profile suppressed expression levels of both isoforms to control-like concentrations. Consequently, our results suggest that CYP2C6 and CYP2E1 require no GH imprinting for either normal expression or GH regulation.

Since there have been no reported sex differences in plasma GH levels of neonatal rats (Oliver et al. 1982; Kacsoh et al. 1989) or for that matter, humans (Cornblath et al. 1965; Laron et al. 1966), it seemed reasonable to study GH imprinting in females by following the same hormonal regimen we had used in male rats (Das et al. 2017). [In this regard, plasma concentrations of GH in the neonatal control female pups (Fig. 1) were comparable to that reported in age matched normal males (Das et al. 2017).] Notwithstanding, simultaneous administration of GH to males prevented MSG-induced demasculinization of CYP2C11 expression, body weight gain and obesity indices (Das et al. 2017), whereas the same neonatal treatment to female pups proved ineffective. That is, instead of preventing GH-independent expression of CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 resulting from the MSG-alone treatment, concurrent neonatal administration of GH or GRH along with MSG appeared to have enhanced the magnitude of adult GH-independent CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 expression that exhibited no further induction following restoration of the feminine GH profile.

The ineffectiveness of concomitant GH treatment to prevent the MSG induced developmental defects cannot be explained by a direct action of MSG on the differentiating liver (Kaufhold, et al. 2002) or the involvement of hormones other than GH (Das et al. 2014). Instead, we found that while the male and female pups received the same GH treatment, the resulting plasma GH concentrations were very different. Simultaneous administration of GH to MSG treated male pups generally restored circulating GH concentrations to normal control-like levels (Das et al. 2017). In contrast, the same GH regimen (as well as initial GRF treatment) given to female pups resulted in circulating GH concentrations twice as great as controls for the entire treatment period. Moreover, plasma GH levels were determined in blood samples collected about 12 h after each hormone injection (immediately preceding the next injection), suggesting that circulating GH levels may have been even higher following the injection. The resulting pharmacologic concentrations of circulating GH in the female neonates may have permanently damaged developing mechanisms establishing GH regulation of adult obesity, body weight and CYP expression. Like all hormone action, less than or more than physiologic concentrations can result in pathologies. Hormonal imprinting appears to be no exception. As observed here and reported earlier (Das et al. 2017), abnormally elevating GH level by administering the hormone to normal neonates produces imprinting defects characteristic of GH deficiency.

Our understanding of mammalian sexual differentiation has been derived from the hundreds of studies examining sexual organogenesis. That is, masculinization is an “active” function in which testosterone or its metabolites imprint the indifferent reproductive anlagen in genetic males to develop into male reproductive structures. On the other hand, feminization is a “passive” event requiring no hormonal imprinting in which the indifferent reproductive anlagen in the genetic female intrinsically organize into female reproductive structures. In fact, androgen administration to genetic females can masculinize the perinatal female, irreversibly disrupting feminization (Goldman 1970, Feder 1981, Shapiro 1985). In contrast, our present findings, considered with previous reports (Das et al. 2014, 2017) examining the imprinting role of developmental GH indicates that the same hormone can either masculinize or feminize the hepatic drug metabolizing enzyme system. We propose that the specificity of the GH imprinted sexual response resides within the substrate to be imprinted. That is, exposure of the genetic male liver to developmental GH imprints a selective responsiveness of the inchoate CYPs to the adult masculine episodic GH profile, whereas developmental exposure of the genetic female liver to the same hormone imprints the differentiating CYPs to respond to the adult feminine continuous GH profile (Fig. 8). In addition, as cited in the Introduction, GH imprinting in both males and females imposes a strict sexual dimorphism characterized by a permanent refractoriness to the GH profile of the opposite sex and those CYP isoforms they induce.

Figure 8.

Perinatal GH imprinting of sex-dependent differences in adult hepatic CYP isoforms. In half of the newborns, pituitary GH secretion is blocked by MSG administration. The remaining pups are untreated (i.e., MSG-vehicle) allowing GH imprinting of the developing liver (depicted as darker and surrounded by rays). Expression of the principle CYP isoforms, female- specific CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 as well as male-specific CYP2C11 are solely regulated by the adult sex-dependent GH profiles, and consequently are only expressed during adulthood. Accordingly, these hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes are first measured in adult rats, and for experimental purposes, devoid of pituitary GH secretion by either hypophysectomy of the GH- imprinted rats or by the permanent inhibition of somatotroph section by the perinatally administered MSG. Whereas the GH-imprinted females are incapable of expressing CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 in the absence of adult GH, considerable GH-dependent expression levels of these isoforms are observed in neonatally MSG-treated adult females. Expression of hepatic CYP2C11 in adult males, either GH-imprinted, or not, is totally suppressed in the absence of adult GH secretion. Restoration of the circulating sex-dependent GH profiles discloses an inherent sexual dimorphism. Renaturalization of the feminine continuous GH profile restores normal-like (100%) expression levels of CYP2C12 and CYP2C7 to all females; GH imprinted and imprint-blocked. In contrast, replacement of the masculine episodic GH profile restores normal-like (100%) levels of CYP2C11 to the GH imprinted males, but is completely ineffective inducing the enzyme in males not imprinted by GH. The results demonstrate that the ability of the adult male to express the principle male-specific CYP2C11 isoform is totally dependent on perinatal GH imprinting without which the isoform is permanently incapable of being expressed. In the case of the female, perinatal GH imprints the developing liver so that in adulthood, the expression of the major female isoforms, CYP2C12 and CYP2C7, are now solely dependent upon the continuous feminine GH profile. In the absence of GH imprinting, the female- dependent isoforms are unrestrictively inducible by the feminine as well as masculine GH profile and even in the absence of GH. Thus, perinatal GH imprinting assures that the expression of female CYPs are solely dependent on the feminine continuous GH profile, while expression of the male isoform is dependent on the masculine episodic GH profile.

As there is a myriad of metabolic functions in humans, including growth rates and lean body mass (e.g., note our Lee index findings); cardiovascular, bone, adipose and muscle physiology; protein, carbohydrate, lipid and electrolyte metabolism as well as insulin like growth factor −1 activity all regulated, at least in part, by GH, and like CYP expression, exhibit irreversible sexual dimorphisms (Thangavel & Shapiro 2007), it may be that these adult functions also require perinatal GH imprinting and could be vulnerable in both sexes to pediatric drug therapy known to inadvertently disrupt GH secretion.

Highlights.

Sexually dimorphic CYPs are only expressed in adulthood, but “set” (imprinted) perinatally.

As in the male, developmental growth hormone (GH) is responsible for this imprinting in female rats.

• Major CYPs in imprinted females now become solely dependent on the feminine GH profile.

Without GH imprinting, expression of the female CYPs are permanently GH- independent.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HD-061285) and the Chutzpah Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- GH

growth hormone

- GRF

growth hormone releasing factor

- HYPOX

hypophysectomy

- MSG

monosodium glutamate

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agrawal AK, Pampori NA & Shapiro BH 1995. Neonatal phenobarbital-induced defects in age- and sex-specific growth hormone profiles regulating monooxygenases. American Journal of Physiology 268 E439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AK & Shapiro BH 1997. Gender, age and dose effects of neonatally administered aspartate on the sexually dimorphic plasma growth hormone profiles regulating expression of the rat sex-dependent hepatic CYP isoforms. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 25 1249–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AK & Shapiro BH 2000. Differential expression of gender-dependent hepatic isoforms of cytochrome P-450 by pulse signals in the circulating masculine episodic growth hormone profile of the rat. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 292 228–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia A, Clodfelter KH &Waxman DJ 2004. Sexual dimorphism of rat liver gene expression: regulatory role of growth hormone revealed by deoxyribonucleic acid microarray analysis. Molecular Endocrinology 18 747–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Das RK, Giffear KA & Shapiro BH 2015. Permanent uncoupling of male-specific CYP2C11 transcription/translation by perinatal glutamate. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 284 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Das RK & Shapiro BH 2013. Growth hormone-independent suppression of growth hormone-dependent female isoforms of cytochrome P450 by the somatostatin analog octreotide. European Journal of Pharmacology 715 256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella SG, Locatelli V, de Gennaro V, Puggioni R, Pintor C & Muller EE 1985. Human pancreatic growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone stimulates GH synthesis and release in infant rats. An in vivo study. Endocrinology 116 574–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Fischer L, Yang K, Chung H & Jeong H 2011. Isoform-specific regulation of cytochrome P450 expression and activity by estradiol in female rats. Biochemical Pharmacology 81 777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblath M, Parker ML, Reisner SH, Forbes AE & Daughaday WH 1965. Secretion and metabolism of growth hormone in premature and full-term infants. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 25 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaba G 2008. Hormonal imprinting: phylogeny, ontogeny, diseases and possible role in present- day human evolution. Cell Biochemistry and Function 26 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das RK, Banerjee S & Shapiro BH 2013. Noncanonical suppression of GH-dependent isoforms of cytochrome P450 by the somatostatin analog octreotide. Journal of Endocrinology 216 87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das RK, Banerjee S & Shapiro BH 2014. Irreversible perinatal imprinting of adult expression of the principal sex-dependent drug-metabolizing enzyme CYP2C11. The FASEB Journal 28 4111–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das RK, Banerjee S & Shapiro BH 2017. Growth hormone: a newly identified developmental organizer. Journal of Endocrinology 232 377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey HW, Park SH, Grattan DR, McLachlan MJ & Waxman DJ 1999. STAT5b-deficient mice are growth hormone pulse-resistant. Role of STAT5b in sex-specific liver p450 expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 35331–35336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir RN, Dworakowski W & Shapiro BH 2002. Middle-age alterations in the sexually dimorphic plasma growth hormone profiles: involvement of growth hormone-releasing factor and effects on cytochrome p450 expression. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 30 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir RN, Dworakowski W, Thangavel C & Shapiro BH 2006. Sexually dimorphic regulation of hepatic isoforms of human cytochrome p450 by growth hormone. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 316 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir RN & Shapiro BH 2003. Interpulse growth hormone secretion in the episodic plasma profile causes the sex reversal of cytochrome P450s in senescent male rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 15224–15228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir RN, Thangavel C & Shapiro BH 2007. Attenuated expression of episodic growth hormone- induced CYP2C11 in female rats associated with suboptimal activation of the Jak2/Stat5B and other modulating signaling pathways. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 35 2102–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder HH 1981. Perinatal hormones and their role in the development of sexually dimorphic behaviors. In Adler N (ed.), Neuroendocrinology of Reproduction, Plenum Press, New York, pp. 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MC, Thangavel C & Shapiro BH 2001. Epidermal growth factor regulation of female- dependent CYP2A1 and CYP2C12 in primary rat hepatocyte culture. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 29 111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AS 1970. Animal models of inborn errors of steroidogenesis and steroid action; In Mammalian reproduction, eds. Gibian and Plotz, pp. 389–436. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kacsoh B, Terry LC, Meyers JS, Crowley WR & Grosvenor CE 1989. Maternal modulation of growth hormone secretion in the neonatal rat. I. Involvement of milk factors. Endocrinology 125 1326–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufhold A, Nigam PK, Dhir RN & Shapiro BH 2002. Prevention of latently expressed CYP2C11, CYP3A2, and growth hormone defects in neonatally monosodium glutamate-treated male rats by the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dizocilpine maleate. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 302 490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laron Z, Mannheimer S, Pertzelan A & Nitzan M 1966. Serum growth hormone concentration in full term infants. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences 2 770–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MO 1928. Determination of the surface area of the white rat with its application to the expression of metabolic results. American Journal of Physiology 89 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami T, Sato Y, Ariga S, Sato T, Shimomura T, Kashimura H, Hasegawa Y & Yukawa M 2011. Regulation of synthesis and oxidation of fatty acids by adiponectin receptors (AdipoR1/R2) and insulin receptor substrate isoforms (IRS-1/−2) of the liver in a nonalcoholic steatohepatitis animal model. Metabolism 60 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan ET, MacGeoch C & Gustafsson JA 1985. Hormonal and developmental regulation of expression of the hepatic microsomal steroid 16 alpha-hydroxylase cytochrome P-450 apoprotein in the rat. Journal of Biological Chemistry 260 11895–11898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C, Giraud P, Lissitzky JC, Cote J, Boudouresque F, Gillioz P & Conte-Devolx B 1982. Influence of endogenous somatostatin on growth hormone and thyrotropin secretion in neonatal rats. Endocrinology 110 1018–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW 1969. Brain lesions, obesity, and other disturbances in mice treated with monosodium glutamate. Science 164 719–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori NA, Agrawal AK & Shapiro BH 1991. b Renaturalizing the sexually dimorphic profiles of circulating growth hormone in hypophysectomized rats. Acta endocrinologica 124 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori NA, Agrawal AK & Shapiro BH 2001. Infusion of gender-dependent plasma growth hormone profiles into intact rats: effects of subcutaneous, intraperitoneal, and intravenous routes of rat and human growth hormone on endogenous circulating growth hormone profiles and expression of sexually dimorphic hepatic CYP isoforms. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 29 8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori NA, Agrawal AK, Waxman DJ & Shapiro BH 1991. a Differential effects of neonatally administered glutamate on the ultradian pattern of circulating growth hormone regulating expression of sex-dependent forms of cytochrome P450. Biochemical Pharmacology 41 1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori NA, Pampori MK & Shapiro BH 1995. Dilution of the chemiluminescence reagents reduces the background noise on western blots. Biotechniques 18 588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori NA & Shapiro BH 1996. Feminization of hepatic cytochrome P450s by nominal levels of growth hormone in the feminine plasma profile. Molecular Pharmacology 50 1148–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori NA & Shapiro BH 1999. Gender differences in the responsiveness of the sex-dependent isoforms of hepatic P450 to the feminine plasma growth hormone profile. Endocrinology 140 1245–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollenz RS, Santostefano MJ, Klett E, Richardson VM, Necela B & Birnbaum LS 1998. Female Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to a single oral dose of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin exhibit sustained depletion of aryl hydrocarbon receptor protein in liver, spleen, thymus, and lung. Toxicological Sciences 42 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BH 1985. A paradox in development: masculinization of the brain without androgen receptors. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research 171 151–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BH, Agrawal AK & Pampori NA 1995. Gender differences in drug metabolism regulated by growth hormone. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 27 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro B, Levine D & Adler N 1980. The testicular feminized rat: a naturally occurring model of androgen independent brain masculinization. Science 209 418–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BH, MacLeod JN, Pampori NA, Morrissey JJ, Lapenson DP & Waxman DJ 1989. Signalling elements in the ultradian rhythm of circulating growth hormone regulating expression of sex-dependent forms of hepatic cytochrome P450. Endocrinology 125 2935–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BH, Pampori NA, Ram PA & Waxman DJ 1993. Irreversible suppression of growth hormone-dependent cytochrome P450 2C11 in adult rats neonatally treated with monosodium glutamate. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 265 979–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MR, Dworakowski W & Shapiro BH 2012. Intrasplenic transplantation of isolated adult rat hepatocytes: sex-reversal and/or suppression of the major constituent isoforms of cytochrome P450. Toxicologic Pathology 40 83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel C, Boopathi E & Shapiro BH 2011. Intrinsic sexually dimorphic expression of the principal human CYP3A4 correlated with suboptimal activation of GH/glucocorticoid-dependent transcriptional pathways in men. Endocrinology 152 4813–4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel C, Boopathi E & Shapiro BH 2013. Inherent sex-dependent regulation of human hepatic CYP3A5. British Journal of Pharmacology 168 988–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel C, Dworakowski W & Shapiro BH 2006. Inducibility of male-specific isoforms of cytochrome p450 by sex-dependent growth hormone profiles in hepatocyte cultures from male but not female rats. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 34 410–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel C, Garcia MC & Shapiro BH 2004. Intrinsic sex differences determine expression of growth hormone-regulated female cytochrome P450s. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 220 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel C & Shapiro BH 2007. A molecular basis for the sexually dimorphic response to growth hormone. Endocrinology 148 2894–2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel C & Shapiro BH 2008. Inherent sexually dimorphic expression of hepatic CYP2C12 correlated with repressed activation of growth hormone-regulated signal transduction in male rats. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 36 1884–1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyama K & Himms-Hagen J 1986. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, torpor, and obesity of glutamate-treated mice. American Journal of Physiology 251 E407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD & Johnson ML 1986. Cluster analysis: a simple, versatile, and robust algorithm for endocrine pulse detection. American Journal of Physiology 250 E486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman DJ & Chang TKH 2005 Hormonal regulation of liver cytochrome P450 enzymes. Cytochrome P450 Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry (edited by Ortiz de Montellano PR.). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2005, p. 347–376. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman DJ & Holloway MG 2009. Sex differences in the expression of hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes. Molecular Pharmacology 76 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman DJ, Morrissey JJ & LeBlanc GA 1989. Female-predominant rat hepatic P-450 forms j (IIE1) and 3 (IIA1) are under hormonal regulatory controls distinct from those of the sex-specific P-450 forms. Endocrinology 124 2954–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman DJ, Morrissey JJ, MacLeod JN & Shapiro BH 1990. Depletion of serum growth hormone in adult female rats by neonatal monosodium glutamate treatment without loss of female-specific hepatic enzymes P450 2d (IIC12) and steroid 5 alpha-reductase. Endocrinology 126 712–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrenberg WB 1986. The role of growth hormone-releasing factor and somatostatin on somatic growth in rats. Endocrinology 118 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westin S, Strom A, Gustafsson JA & Zaphiropoulos PG 1990. Growth hormone regulation of the cytochrome P-450IIC subfamily in the rat: inductive, repressive, and transcriptional effects on P- 450f (IIC7) and P-450PB1 (IIC6) gene expression. Molecular Pharmacology 38 192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]