Abstract

Dolutegravir (DTG), a potent integrase inhibitor, is part of a recommended initial regimen for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Prior reports demonstrated that the clearance of DTG was higher in current smokers than nonsmokers, but the mechanism remains unclear. Using a metabolomic approach, M4 (an aldehyde) was identified as a novel metabolite of DTG. In addition, the formation of M4 was found to be mediated by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1 and 1B1, the enzymes that can be highly induced by cigarette smoking. CYP1A1 and 1B1 were also identified as the major enzymes contributing to the formation of M1 (an N- dealkylated metabolite of DTG) and M5 (an aldehyde). Furthermore, the production of M1 and M4 was significantly increased in the lung of mice treated with 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, an inducer of CYP1A1 and 1B1. In summary, the current study uncovered the CYP1A1 and 1B1-mediated metabolic pathways of DTG. These data suggest that persons with HIV infection receiving DTG should be cautious to cigarettes, and drugs, or exposure to environmental chemicals that induce CYP1A1 and 1B1.

Keywords: Dolutegravir HIV, Metabolism, CYP1A1, CYP1B1

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Dolutegravir (DTG) is an integrase inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). DTG chelates the divalent metal cations in the integrase catalytic site of HIV virus through the three coplanar oxygen atoms in the structure, thereby blocking viral replication [1]. DTG has been considered a new generation HIV integrase inhibitor with a better resistance profile compared to the first generation integrase inhibitors [2,3]. DTG possesses prolonged binding to the integrase-DNA complex, and thus has a higher genetic barrier to resistance [4]. Based on its lower risk of resistance acquisition, DTG, together with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, is a recommended regimen for persons infected with HIV [5,6].

The clinical pharmacokinetics of DTG is favorable in healthy volunteers, with rapid absorption, low clearance and relative long oral terminal half-life [7]. In a mass balance study of DTG, the predominant circulating component identified in plasma was DTG, and 31.6% and 64.0% of the administrated dose was recovered in urine and feces, respectively [8]. The most abundant metabolites of DTG were the ether glucuronide followed by a benzylic hydroxylated metabolite and its hydrolytic product [9]. UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 and cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 are the two key enzymes contributing to the ether glucuronidation and benzylic oxidation of DTG, respectively [10].

The effects of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on DTG pharmacokinetics have been examined in a population pharmacokinetic analysis using combined data from three clinical trials in persons with HIV infection, including smokers. It was found that the clearance of DTG was higher in current smokers than non-smokers [11]. However, the exact mechanism for this difference is unclear. The induction of metabolic enzymes responsible for DTG metabolism by cigarette smoking may be the reason for this pharmacokinetic difference. Cigarette smoking has been found to induce CYPs, including CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2B6 and 2E1 [12–14], but its influence on CYP3A4 is minor [15] The current study re-profiled pathways of DTG using a metabolomic approach. The enzymes that contribute to DTG metabolism were profiled using recombinant human CYPs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents.

DTG, methoxyamine (NH2OMe), isoniazid (INH), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), corn oil and semicarbazide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 2,4- difluorobenzaldehyde was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). β- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and 2,3’,4,5’- tetramethoxystilbene (TMS) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Tewksbury, MA) and Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI), respectively. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemical (Toronto, Ontario). Human liver microsomes (HLM) and the recombinant human CYPs (EasyCYP Bactosomes) were purchased from XenoTech (Lenexa, KS). All solvents for ultra-performance liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOFMS) analysis were of the highest grade commercially available.

2.2. Metabolism of DTG in HLM.

Incubations were carried out in 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), containing HLM (1.0 mg/mL), 30 μM DTG and 1.0 mM NADPH in a final volume of 100 μL. In addition, co-incubation with the trapping agent 2.5 mM NH2OMe or semicarbazide was performed. The groups in the absence of NADPH, DTG, or NH2OMe were used as controls. The reactions were continued at 37 °C for 1 hour with gentle shaking. The reactions were terminated by adding 100 pl methanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v). The mixture was vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. Five pl of the supernatant was injected into the UPLC- QTOFMS system for metabolite analysis. All incubations were performed in triplicate.

2.3. Metabolism of DTG by recombinant human CYPs.

Incubations were conducted in 1 × PBS (pH 7.4), containing 5 or 30 μM DTG, 2.5 mM NH2OMe, 15 pmol of each recombinant CYP (control, CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C18, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4 and 3A5), and 1 mM NADPH in a final volume of 200 μL. For the kinetic study, different concentrations of DTG (0, 5, 15, 30, 100, 200, and 300 μM) were incubated with CYP1A1, 1B1 or 3A4 in a 200 μL system. For the trapping studies using INH, incubations were performed in 1 × PBS (pH 7.4), containing 30 μM DTG, 100 μM INH, 15 pmol of the recombinant CYP (control, CYP1A1, 1B1, and 3A4), and 1 mM NADPH in a final volume of 200 μL.

Another group of incubations of 100 μM INH with different concentrations of 2,4- difluorobenzaldehyde (0, 1, 10, and 100 nM) were carried out directly in 1 × PBS (pH 7.4) with a final volume of 200 μL. In addition, co-incubations of the inhibitor TMS A at 10 μM and 500 nM with CYP1A1 and 1B1, respectively, were performed to confirm the roles of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in DTG metabolism. All incubations were carried out at 37 °C for 1 hour, and the reactions were terminated with 200 μL of methanol. The mixture was then vortexed and dried, and further reconstituted in 100 μL of water/acetonitrile/methanol (1:2:2, v/v/v). The suspension was vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min.A 10 μL of the supernatant was injected into the UPLC-QTOFMS system for metabolite analysis. The Km values for CYP1A1 and 1B1 were calculated using Graphpad Prism 6.

2.4. DTG metabolism in lung S9 from mice treated with TCDD.

Following Harrigan’s protocol [16], C57BL/6 mice (male, 7–8 weeks old) were treated with TCDD (5 μg/kg, 2% DMSO in corn oil, i.p.) or vehicle (n = 4). Forty- eight hours later, all mice were sacrificed and lung samples were harvested. Lung tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. One hundred mg of lung tissue was homogenized in 500 μL of 1 × PBS at 0 °C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 9,000 g for 25 min at 4 °C and the resulting supernatant was designated as lung S9 fraction. The total protein concentration of the S9 fraction was determined by bovine serum albumin standard (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) calibration curves.

Incubations were conducted in 1 × PBS (pH 7.4), containing 30 μM DTG, 2.5 mM NH2OMe, 2 mg/mL lung S9, and 1 mM NADPH in a final volume of 200 μL. The incubations were continued at 37 °C for 1 hour, and terminated with 200 pl of methanol. The resulting mixture was vortexed and dried, and reconstituted in 100 μL of water/acetonitrile/methanol (1:2:2, v/v/v). The suspension was vortexed and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. A 10 μL of the supernatant was injected into the UPLC-QTOFMS system for metabolite analysis.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) for Analysis of Cyb1a1 and 1b1.

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 40 mg of frozen lung tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and subjected to reverse transcription with random hexamer primers and M-MLV RT (Invitrogen). qPCR using SYBR green PCR master mix was performed with the ABI7500 System. All data was normalized against the cyclophilin control.

2.6. UPLC-QTOFMS analysis.

Chromatographic separation of metabolites was performed on an Acquity UPLC BEH 18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μM; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water, and the mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The elution gradient was set as follows: 0.0–1.0 min, 2% B; 1.0–9.0 min, 2–95% B; 9.0–13.5 min, 95% B; 13.5–13.6 min, 95–2% B; 13.6–15 min, 2% B. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.5 mL/min and the column temperature was maintained at 50 °C. The QTOFMS system was operated in a positive high-resolution mode with electrospray ionization [17]. To maximize the class discrimination, partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was conducted using SIMCA-P software (Version 13, Umetrics, Kinnelon, NJ). DTG metabolites were identified by the corresponding S-plot based on accurate mass measurement (mass errors less than 10 ppm) and MS/MS fragmental analysis.

2.7. Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means or means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with two-tailed Student’s t-test and a p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of M1, M2, and M3.

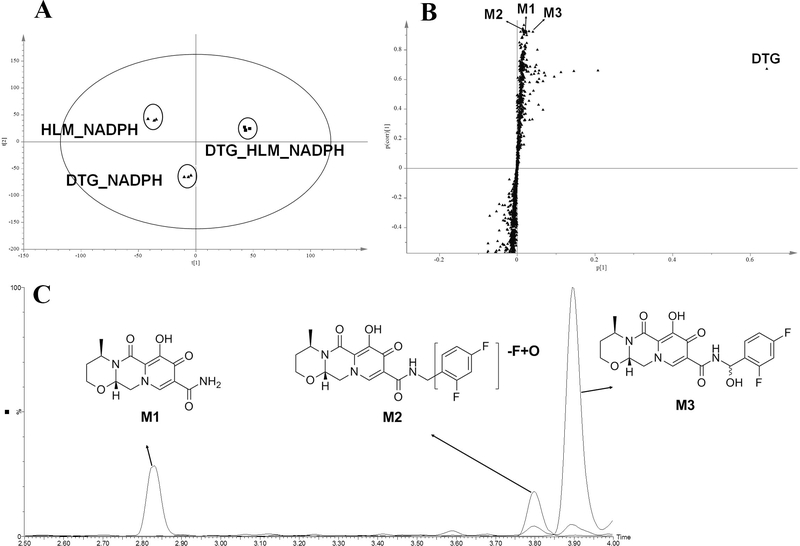

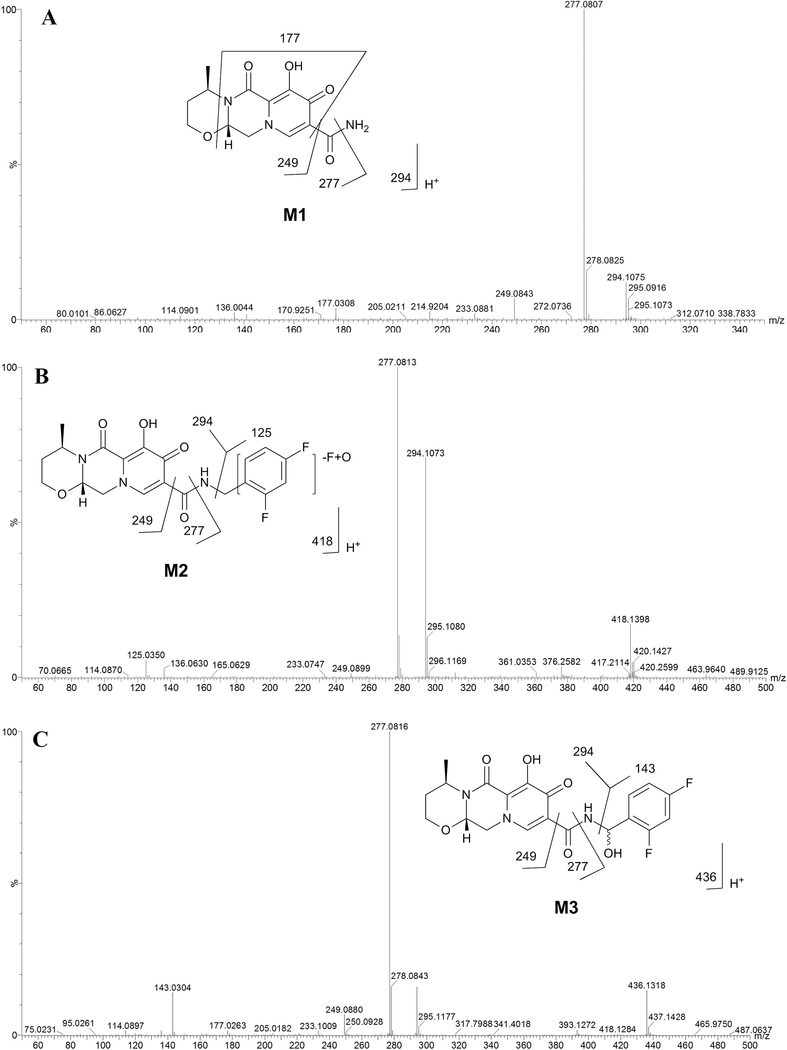

Three groups of DTG incubations were well separated to the corresponding clusters by PLS-DA analysis (Fig. 1A). The top ranking ions labeled in the upper-right quadrant of the S-plot were identified as DTG and its metabolites M1, M2 and M3 (Fig. 1B). These three metabolites were only detected in the incubation group with HLM and NADPH, suggesting they are produced in CYP-dependent pathways. The chromatograms of M1, M2 and M3 are shown in Fig. 1C. M1 has a protonated molecular ion [M+H] at m/z = 294.1075 Da, which indicates the loss of the 2,4- diflurobenzyl moiety. MS/MS fragmental ions of M1 at m/z = 277, 249, and 177 confirmed the A-dealkylated structure (Fig. 2 A). Based on the protonated molecular ion [M+H] at m/z = 418.1398 Da, M2 was identified as an oxidative defluorination metabolite. The primary MS/MS fragmental ions of M2 were found at m/z 294, 277 and 125 (Fig. 2B. The ion at m/z 125 in M2 indicated the loss of a fluorine atom and addition of an oxygen atom. The accurate molecular weight revealed M3 was an oxidized DTG metabolite. The major MS/MS fragmental ions of M3 were found at m/z 294, 277 and 143 (Fig. 2C). The MS/MS fragmental ion at m/z 143 in M3 suggested the oxidation occurred at the phenyl part of DTG ( Fig. 2C). Both M2 and M3 have the fragmental ion at m/z 294, the same mass as M1 (Fig 2). Therefore, when we extracted the chromatogram of M1 at m/z 294, all peaks at m/z 294 showed up, which came to be the small peaks within M2 and M3 (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Metabolomic screening of DTG metabolites in human liver microsomes (HLM).

Three groups of DTG incubations were conducted: HLM_NADPH, DTG_NADPH, and DTG_HLM_NADPH. All incubation samples were analyzed by UPLC-QTOFMS. (A) Separation of incubation samples in a PLS-DA score plot. (B ) A loading S-plot generated by the PLS-DA analysis. The top ranking ions were identified as DTG metabolites (M1, M2 and M3). (C) Chromatograms and structures of M1, M2 and M3.

Fig. 2. Identification of M1-M3.

These metabolites were identified by UPLC- QTOFMS in the incubation of DTG with HLM. (A) MS/MS spectrum of M1. (B) MS/MS spectrum of M2. (C) MS/MS spectrum of M3. The structures of M1-M3 with fragmental patterns are inlaid in the spectra.

3.2. Identification of M4.

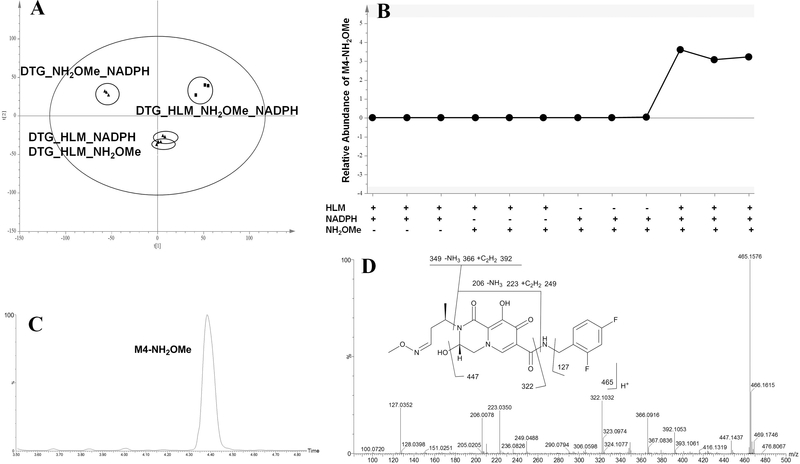

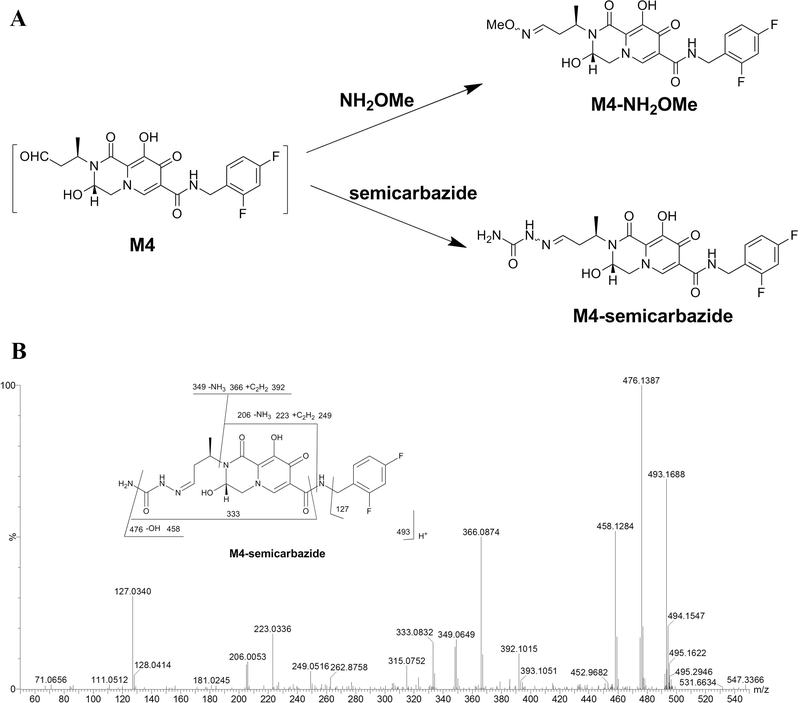

To recapture possible production of aldehyde, NH2OMe was used as a trapping agent [18]. Four groups of incubation were well-separated in the PLS-DA score plot (Fig. 3 A). The trend plot showed that M4-NH2OMe was present only in the DTG_HLM_NH2OMe_NADPH group (an incubation system containing DTG, HLM, NH2OMe, and NADPH), suggesting its production is CYP-dependent (Fig. 3B). M4-NH2OM le was eluted at 4.40 min (Fig. 3C) with the major MS/MS fragmental ions at m/z 447, 392, 366, 322, 249, 223, 206 and 127 (Fig. 3D). The fragmental ions at m/z 127 and 322 demonstrated that the 2,4-difluorophenyl group was intact, and the oxime structure appeared at the left region in DTG. Fragmental ions at m/z 392 and 249, typically peaks formed by McLafferty rearrangement of the oxime moiety, indicated that the oxidation occurred at the adjacent position of the oxygen atom rather than the nitrogen atom in DTG’s oxazine ring. To further confirm M4 as an aldehyde, semicarbazide [19] was used as another trapping agent. As expected, the corresponding oxime was detected (Fig. 4 A), and the MS/MS fragmental pattern of M4-semicarbazide is similar to that of M4-NH2OMe (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3. Metabolomic screening of DTG metabolites in HLM using NH2OMe as a trapping regent.

Four groups of DTG incubations were conducted: DTG_NH2OMe_NADPH, DTG_HLM_NADPH, DTG_HLM_NH2OMe, and DTG_HLM_NH2OMe_NADPH. All incubation samples were analyzed by UPLC- QTOFMS. (A) Separation of incubation samples in a PLS-DA score plot. (B) A trend plot of M4-NH2OMe generated by the PLS-DA analysis. (C) Chromatogram of M4- NH2OMe. (D) MS/MS spectrum and structure of M4-NH2OMe.

Fig. 4. Identification of M4 by UPLC-QTOFMS.

(A) The scheme for the formation of oximes M4-NH2OMe and M4-semicarbazide from aldehyde M4 using NH2OMe and semicarbazide as trapping agents, respectively. The aldehyde group reacted with the amine group to form an imine product. (B) MS/MS spectrum of M4-semicarbazide. The structure of M4-semicarbazide with fragmental patterns is inlaid in the spectrum.

3.3. Role of CYPs in the formation of M1, M2 and M3.

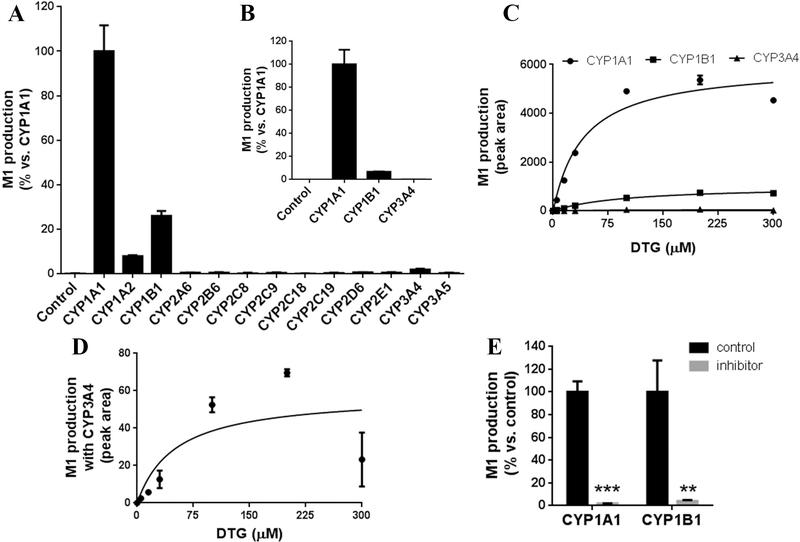

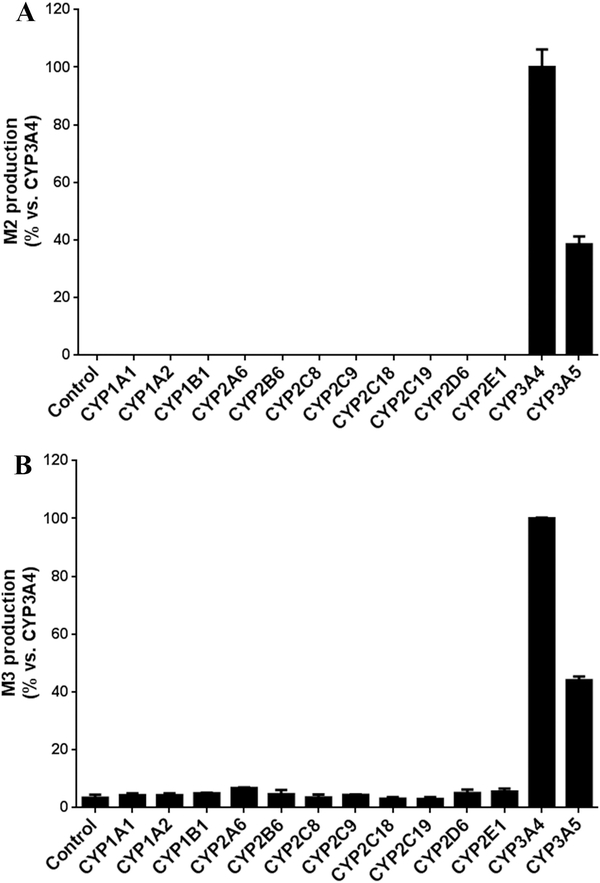

CYP3A4 has been found to be important in M1 formation [10]. However, the current study found that CYP1A1 and 1B1 are more efficient than CYP3A4 in M1 production in the incubation of DTG at 30 μM (Fig. 5A-C). DTG itself is a weak CYP3A4 inhibitor [10]. To avoid potential inhibition of CYP3A4, incubations with a lower concentration of DTG (5 μM) were conducted, and the results were similar to that of DTG at 30 μM (Fig. 5B). The roles of CYP1A1, 1B1 and 3A4 in M1 formation were further investigated by profiling the enzymatic kinetics of M1 production with DTG concentration up to 300 μM (Fig. 5C). The Km values of CYP1A1 and 1B1 for M1 formation were 41.4 μM and 97.1 μM, respectively. M1 formation was decreased in the incubation with CYP3A4 and DTG at 300 μM, due to CYP3A4 inhibition by DTG ( Fig. 5D). Furthermore, co-incubation of DTG with TMS, a CYP1A1 and 1B1 inhibitor [20], significantly decreased M1 production (Fig. 5E), which confirmed the roles of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in M1 production. Nevertheless, CYP3A4 and 3A5 were the major enzymes contributing to the formation of M2 and M3 in DTG metabolism(Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Role of CYPs in Ml formation.

(A, B) Ml production in the incubations of DTG at 30 μM (A) and 5 μM (B) with recombinant CYPs, respectively. The relative abundance of M1 from the incubation with CYP1A1 was set as 100%. (C) Enzymatic kinetic plots of CYP1A1, 1B1 and 3A4 for M1 formation. The concentrations of DTG were 0, 5, 15, 30, 100, 200, and 300 μM. (D) The enlarged CYP3A4 kinetic plot for M1 production. (E) Effect of TMS on M1 formation in the incubations with CYP1A1 and 1B1. TMS was used as an inhibitor of CYP1A1 and 1B1. The relative abundance of M1 in control group was set as 100%. The enzymatic kinetic study was conducted in duplicate and other incubations were conducted in triplicate. All data are expressed as means ± S.D. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs control.

Fig. 6. Role of CYPs in formation of M2(A) and M3 (B).

The incubations were conducted with DTG (30 μM) and recombinant CYPs. The relative abundance of M2 and M3 from the incubation with CYP3A4 was set as 100%. All the data are expressed as means ± S.D. (n = 3).

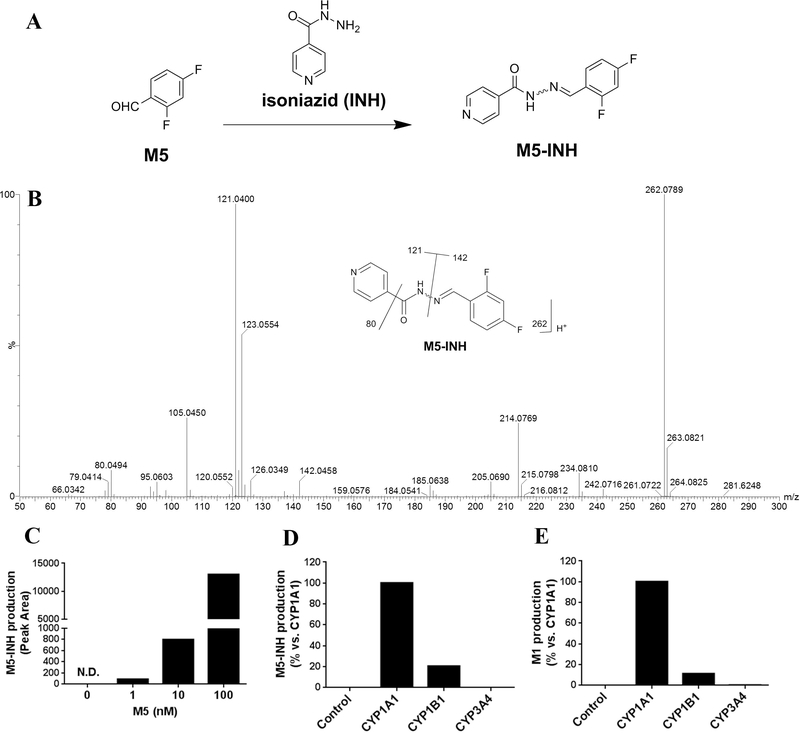

3.4. Identification of M5.

Theoretically, besides M1, another hydrolytic product of M3 should be 2,4- difluorobenzaldehyde (M5). However, M5 was not identified when NH2OMe was used as a trapping regent. Direct incubation of NH2OMe with M5 standard was performed, but no oxime was detected, which may be related to the weak reaction activity of NH2OMe with M5 or low detection sensitivity of the M5-NH2OMe oxime INH contains a hydrazine group that has a high reactivity with aldehyde products [21]. Through incubation of INH with M5 standard, M5-INH adduct was identified (Fig. 7A). The MS/MS fragmental ions of M5-INH were at m/z 214, 142, 121, 105 and 80 (Fig. 7B). The ions at 142 and 121 indicated the 2,4-difluorophenyl ring and isonicotinamide moiety, respectively. The detection limit of M5 by trapping with INH could be as low as 1 nM (Fig. 7C). Based on the roles of CYPs in M1 formation (Fig. 5), the key CYPs responsible for M5 production should be CYP1A1 and 1B1. Indeed, M5-INH could be detected in the incubation of DTG with CYP1A1 and 1B1 (Fig. 7D), and the abundance of M5-INH was consistent with M1 production (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7. Identification of M5 by UPLC-QTOFMS.

(A) The scheme for the formation of oxime M5-INH from aldehyde M5 using the trapping agent INH. The hydrazine group of INH can react with the aldehyde group of M5. (B) MS/MS spectrum of M5-INH. (C) The relative abundance of M5-INH in the incubation of INH (100 μM) with different concentration of M5 (0, 1, 10, and 100 nM). N.D., not detected. (D, E) Comparison of the productions of M5-INH (D) and M1 (E) in the incubations of DTG with control, CYP1A1, 1B1 and 3A4. The relative abundance from the incubation with CYP1A1 was set as 100%. All the data are expressed as means (n = 2).

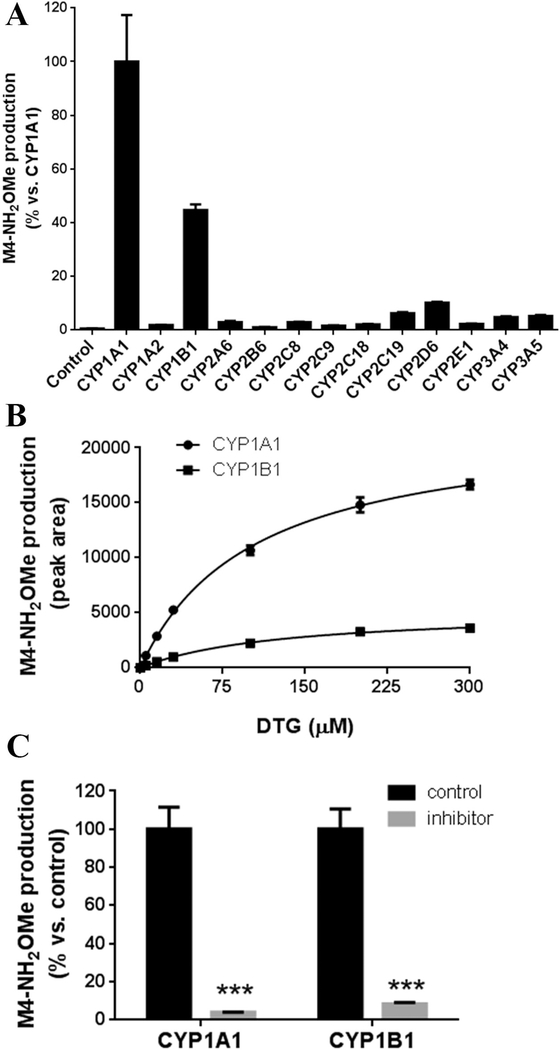

3.5. Roles of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in M4 formation.

The major CYPs contributing to M4 formation were found to be CYP1A1 and 1B1 (Fig. 8A ). The enzymatic kinetics of M4 formation was investigated in the incubations of DTG with CYP1A1 and 1B1. The estimated Km values of CYP1A1 and 1B1 for M4 formation were 103.5 μM and 127.5 μM, respectively (Fig. 8B). The kinetics of M4 formation in CYP3A4 was similar to M1 ( Fig. 5C|C and 5D), which showed a minor role in M4 production and a decline at 300 μM of DTG (data not shown). Furthermore, the roles of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in M4 formation were confirmed using TMS, which significantly inhibited M4 production ( Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8. Role of CYPs in M4 formation.

(A) M4-NH2OMe production in the A incubations of DTG (30 μM) with individual CYP (15 pmol) in the presence of NADPH (1 mM) and NH2OMe (2.5 mM). The relative abundance of M4-NH2OMe from CYP1A1 was set as 100%. (B) Enzymatic kinetics plots of CYP1A1 and 1B1 for M4-NH2OMe formation. (C) Effect of TMS on M4-NH2OMe formation. The relative abundance of M4-NH2OMe in control group was set as 100%. The enzymatic kinetic study was conducted in duplicate and other incubations were conducted in triplicate. All data are expressed as means ± S.D.. ***p < 0.001 vs control.

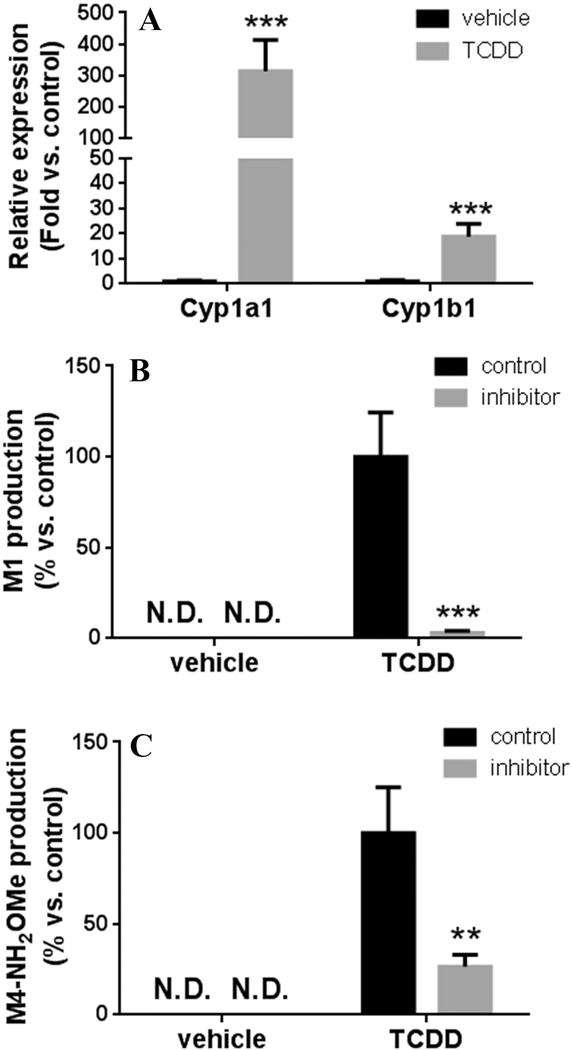

3.6. Induction of CYP1A1 and 1B1 boosts the formation of M1 and M4.

TCDD is a strong inducer of CYP1A1 and 1B1 [22,23]. As expected, pretreatment of mice with TCDD significantly increased the expression of Cyp1a1 and 1b1 in mouse lung (Fig. 9A). Compared to the vehicle group, the productions of M1 an d M4 were significantly increased in the lungs of mice treated with TCDD ( Fig. 9b and 9C). The increased productions of DTG metabolites were consistent with the upregulation of Cyp1a1 and 1b1 in the TCDD group. In addition, TMS significantly suppressed the formation of M1 and M4 in the lung, which further confirmed the roles of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in M1 and M4 production (Fig. 9B and 9C).

Fig. 9. Effects of CYP1A1 and 1B1 induction on the production of M1 and M4.

All data are expressed as means ± S.D. (n = 4). (A) Cyp1a1 and 1b1 expression in the lung of mice treated with vehicle or TCDD. mRNAs of Cyplal and lbl were analyzed by qPCR. The expression of Cyp1a1 or 1b1 in vehicle group was set as 1. ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle group. (B, C) The formation of M1 (B) and M4-NH2OMe (C) in the incubation of DTG with lung S9 of mice treated with vehicle or TCDD, and the inhibitory effects of TMS on these two metabolic pathways. M1 and M4-NH2OMe were determined by UPLC-QTOFMS. The relative abundance of M1 and M4- NH2OMe in control group was set as 100%. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs control.

4. Discussion

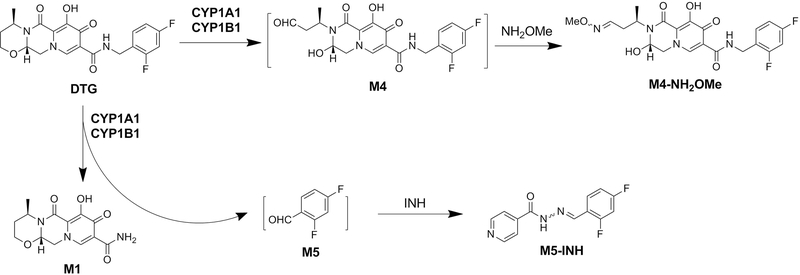

Using a metabolomics approach, the current study uncovered the CYP1A1 and 1B1- mediated metabolic pathways of DTG (M1 and M4) (Fig. 10). The current study also found that CYP1A1 and 1B1-mediated metabolism of DTG can produce two aldehydes (M4 and M5) (Fig. 10). In addition, CYP1A1 and 1B1 are found to be more efficient than CYP3A4 in M1 and M4 production.

Fig. 10. Roles of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in DTG metabolism.

CYP1A1 and 1B1 contribute to two metabolic pathways of DTG to produce M1, M4 and M5. Both M4 and M5 are aldehydes that can be trapped by NH2OMe and INH, respectively.

Both CYP1A1 and 1B1 are extrahepatic CYPs [24]. CYP1A1 is primarily found in the respiratory system, while CYP1B1 is more widely expressed in extrahepatic tissues [25,26]. CYP1A1 and 1B1 are involved in the metabolism of multiple procarcinogens including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from tobacco and environmental exposure [12] On the other hand, PAHs can induce the expression of CYP1A1 and 1B1 through an aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-dependent mechanism [27l Indeed, the expressions of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in the lung are significantly upregulated in smokers compared to non-smokers [28]. Besides CYP1s, cigarette smoking also induces CYP2B6 and CYP2E1 [14,29], but neither CYP2B6 nor CYP2E1 is involved in DTG metabolism (Figs. 5, 6, and 8). Although nicotine, a dominant alkaloid in cigarette, is reported to be an activator of pregnane X receptor that upregulates CYP3A4 expression [30]), the pharmacokinetic parameters of midazolam, a classical CYP3A4 probe drug, are not significantly different between smokers and non-smokers [15j. These data suggest that cigarette smoking could alter DTG metabolism by inducing CYP1A1 and 1B1, but not other CYPs.

TCDD is a potent AhR ligand that can strongly induce the expression of CYP1A1 and 1B1 [27]. The current study found that CYP1A1 and 1B1-dependent production of DTG metabolites (M1 and M4) were dramatically increased in the lungs of mice treated with TCDD. Interestingly, DTG is highly distributed in the lung after DTG treatment [9]. The high pulmonary exposure to DTG together with the highly induced CYP1A1 and 1B1 in the lung of smokers will increase DTG metabolism, and therefore increase the clearance of DTG. Additionally, brain reservoirs is an obstacle for HIV cure [31] in part due to the poor local concentrations of anti-HIV drugs in the brain. Because CYP1A1 and 1B1 are expressed in the brain [32], cerebral DTG concentration would be decreased by CYP1 induction and thereby negatively influences therapeutic outcomes.

Although DTG displayed a favorable safety profile in clinical trials, discontinuation rates of DTG was higher than expected in real-life settings [33,34]. The major reported adverse event of DTG is neurotoxicity [35], and the underlying mechanism is unclear. Both M4 and M5 are aldehyde metabolites of DTG and they are produced by CYP1A1 and 1B1 (Fig. 10). Aldehyde, a hard electrophile, can covalently bind with hard nucleophiles, such as lysine residues in proteins, which can cause protein dysfunction and potentially lead to toxicity [36]. Considering the expression of CYP1A1 and 1B1 in the brain [32], further investigation is warranted to examine the potential contribution of CYP1A1 and 1B1-mediated production of aldehydes to DTG neurotoxicity.

In summary, the current study identified two CYP1A1 and 1B1-mediated pathways in DTG metabolism (M1 and M4) (Fig. 10). Induction of CYP1A1 and 1B1 can significantly accelerate the metabolic pathways of M1 and M4. These data suggest that persons with HIV receiving DTG should be cautious to cigarette smoking, drugs, and environmental chemicals that activate AhR and induce CYP1A1 and 1B1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK090305) and the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (AI131983).

Abbreviations

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DTG

dolutegravir

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HLM

human liver microsomes INH, isoniazid

- NADPH

β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NH2OMe

methoxyamine

- PLS-DA

partial leastsquares-discriminant analysis

- PAH

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- TMS

2,3’,4,5’-tetramethoxystilbene

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

- UPLC-QTOFMS

ultra-performance liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Hare S, Smith SJ, Metifiot M, Jaxa-Chamiec A, Pommier Y, Hughes SH, Cherepanov P, Structural and functional analyses of the second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572), Mol. Pharmacol 80(4) (2011) 565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kobayashi M Yoshinaga T Seki T Wakasa-Morimoto C Brown KW Ferris R Foster SA Hazen RJ Miki S Suyama- Kagitani A Kawauchi-Miki S Taishi T Kawasuji T Johns BA Underwood MR Garvey EP Sato A Fujiwara T In Vitro antiretroviral properties of S/GSK1349572, a next-generation HIV integrase inhibitor Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 2 2011. 813–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Eron JJ, Clotet B, Durant J, Katlama C, Kumar P, Lazzarin A, Poizot- Martin I, Richmond G, Soriano V, Ait-Khaled M, Fujiwara T, Huang J, Min S, Vavro C, Yeo J, Group VS, Safety and efficacy of dolutegravir in treatment- experienced subjects with raltegravir-resistant HIV type 1 infection: 24-week results of the VIKING Study, J. Infect. Dis 207(5) (2013) 740–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hightower KE, Wang R, Deanda F, Johns BA, Weaver K, Shen Y, Tomberlin GH, Carter HL 3rd, Broderick T, Sigethy S, Seki T, Kobayashi M, Underwood MR, Dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572) exhibits significantly slower dissociation than raltegravir and elvitegravir from wild-type and integrase inhibitor-resistant HIV- 1 integrase-DNA complexes, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 55(10) (2011) 4552–4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kaplan R, Wood R, Resistance to first-line ART and a role for dolutegravir, The Lancet HIV 5 (2017) e112–e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Phillips AN, Cambiano V, Nakagawa F, Revill P, Jordan MR, Hallett TB, Doherty M, De Luca A, Lundgren JD, Mhangara M, Apollo T, Mellors J, Nichols B, Parikh U, Pillay D, Rinke de Wit T, Sigaloff K, Havlir D, Kuritzkes DR, Pozniak A, van de Vijver D, Vitoria M, Wainberg MA, Raizes E, Bertagnolio S, Phillips AN, Cambiano V, Nakagawa F, Revill P, Jordan MR, Hallett TB, Doherty M, De Luca A, Lundgren JD, Mhangara M, Apollo T, Mellors J, Nichols B, Parikh U, Pillay D, Rinke de Wit T, Sigaloff K, Havlir D, Kuritzkes DR, Pozniak A, van de Vijver D, Vitoria M, Wainberg MA, Raizes E, Bertagnolio S, Cost-effectiveness of public-health policy options in the presence of pretreatment NNRTI drug resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: a modelling study, The Lancet HIV 5 (2017) e146–e154.r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Min S, Song I, Borland J, Chen S, Lou Y, Fujiwara T, Piscitelli SC, Pharmacokinetics and safety of S/GSK1349572, a next-generation HIV integrase inhibitor, in healthy volunteers, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54(1) (2010) 254–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Castellino S, Moss L, Wagner D, Borland J, Song I, Chen S, Lou Y, Min SS, Goljer I, Culp A, Piscitelli SC, Savina PM, Metabolism, excretion, and mass balance of the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor dolutegravir in humans, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 57(8) (2013) 3536–3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Moss L, Wagner D, Kanaoka E, Olson K, Yueh YL, Bowers GD, The comparative disposition and metabolism of dolutegravir, a potent HIV-1 integrase inhibitor, in mice, rats, and monkeys, Xenobiotica 45(1) (2015) 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Reese MJ, Savina PM, Generaux GT, Tracey H, Humphreys JE, Kanaoka E, Webster LO, Harmon KA, Clarke JD, Polli JW, In vitro investigations into the roles of drug transporters and metabolizing enzymes in the disposition and drug interactions of dolutegravir, a HIV integrase inhibitor, Drug Metab. Dispos 41(2) (2013) 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang J, Hayes S, Sadler BM, Minto I, Brandt J, Piscitelli S, Min S, Song IH, Population pharmacokinetics of dolutegravir in HIV-infected treatment-naïve patients, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 80(3) (2015) 502–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zevin S, Benowitz NL, Drug interactions with tobacco smoking. An update, Clin. Pharmacokinet 36(6) (1999) 425–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Port JL, Yamaguchi K, Du B, De Lorenzo M, Chang M, Heerdt PM, Kopelovich L, Marcus CB, Altorki NK, Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ, Tobacco smoke induces CYP1B1 in the aerodigestive tract, Carcinogenesis 25(11) (2004) 2275–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Washio I, Maeda M, Sugiura C, Shiga R, Yoshida M, Nonen S, Fujio Y, Azuma J, Cigarette smoke extract induces CYP2B6 through constitutive androstane receptor in hepatocytes, Drug Metab. Dispos 39(1) (2011) 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].van der Bol JM, Mathijssen RH, Loos WJ, Friberg LE, van Schaik RH, de Jonge MJ, PLanting AS, Verweij J, Sparreboom A, de Jong FA, Cigarette smoking and irinotecan treatment: pharmacokinetic interaction and effects on neutropenia, J. Clin. Oncol 25(19) (2007) 2719–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Harrigan JA, McGarrigle BP, Sutter TR, Olson JR, Tissue specific induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1 and 1B1 in rat liver and lung following in vitro (tissue slice) and in vivo exposure to benzo(a)pyrene, Toxicol. in vitro 20(4) (2006) 426–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu K, Zhu J, Huang Y, Li C, Lu J, Sachar M, Li S, Ma X, Metabolism of KO143, an ABCG2 inhibitor, Drug Metab. Pharmacok 32(4) (2017) 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu X, Lu Y, Guan X, Dong B, Chavan H, Wang J, Zhang Y, Krishnamurthy P, Li F, Metabolomics reveals the formation of aldehydes and iminium in gefitinib metabolism, Biochem. Pharmacol 97(1) (2015) 111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li F, Lu J, Ma X, CPY3A4-mediated lopinavir bioactivation and its inhibition by ritonavir Drug Metab. Dispos 40(1) (2012) 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim S, Ko H, Park JE, Jung S, Lee SK, Chun Y-J, Design, synthesis, and discovery of novel trans-stilbene analogues as potent and selective human cytochrome P450 1B1 inhibitors, J. Med. Chem 45(1) (2002) 160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li F, Wang P, Liu K, Tarrago MG, Lu J, Chini EN, Ma X, A high dose of isoniazid disturbs endobiotic homeostasis in mouse liver, Drug Metab. Dispos 44(11) (2016)1742–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Diliberto JJ, Akubue PI, Luebke RW, Birnbaum LS, dose-response relationships of tissue distribution and induction of Cyp1A1 and Cyp1A2 enzymatic activities following acute exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice, Toxicol. Appl. Pharm 130(2) (1995) 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Walker NJ, Portier CJ, Lax SF, Crofts FG, Li Y, Lucier GW, Sutter TR, Characterization of the dose-response of CYP1B1, CYP1A1, and CYP1A2 in the liver of female sprague-dawley rats following chronic exposure to 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, Toxicol. Appl. Pharm 154(3) (1999) 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ding X, Kaminsky LS, Human extrahepatic cytochromes P450: function in xenobiotic metabolism and tissue-selective chemical toxicity in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 43 (2003) 149–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shimada T, Hayes CL, Yamazaki H, Amin S, Hecht SS, Guengerich FP, Sutter TR, Activation of chemically diverse procarcinogens by human cytochrome P-450 1B1, Cancer Res. 56(13) (1996) 2979–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hukkanen J, Pelkonen O, Hakkola J, Raunio H, Expression and regulation of xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in human lung, Crit. Rev. Toxicol 32(5) (2002) 391–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Whitlock JP Jr., Genetic and molecular aspects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p- dioxin action, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 30 (1990) 251–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim JH, Sherman ME, Curriero FC, Guengerich FP, Strickland PT, Sutter TR, Expression of cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1 in human lung from smokers, non-smokers, and ex-smokers, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 199(3) (2004) 210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Villard PH, Herber R, Seree EM, Attolini L, Magdalou J, Lacarelle B, Effect of cigarette smoke on UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity and cytochrome P450 content in liver, lung and kidney microsomes in mice, Pharmacol. Toxicol 82(2) (1998) 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lamba V, Yasuda K, Lamba JK, Assem M, Davila J, Strom S, Schuetz EG, PXR (NR1I2): splice variants in human tissues, including brain, and identification of neurosteroids and nicotine as PXR activators, Toxicol. Appl. Pharm 199(3) (2004) 251–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Marban C Forouzanfar F Ait-Ammar A Fahmi F El Mekdad H Daouad F Rohr O Schwartz C Targeting the brain reservoirs: toward an HIV cure Front. Immunol 7 2016. 397–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Miksys SL Tyndale RF Drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450s in the brain J. Psychiatry. Neurosci 27 6 2002. 406–415 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hoffmann C Welz T Sabranski M Kolb M Wolf E Stellbrink HJ Wyen C Higher rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events leading to dolutegravir discontinuation in women and older patients HIV Med. 18 1 2017. 56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].de Boer MG van den Berk GE van Holten N Oryszcyn JE Dorama W Moha DA Brinkman K Intolerance of dolutegravir- containing combination antiretroviral therapy regimens in real-life clinical practice AIDS 30 18 2016. 2831–2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Elzi L Erb S Furrer H Cavassini M Calmy A Vernazza P Guenthard H Bernasconi E Battegay M Adverse events of raltegravir and dolutegravir AIDS 31 13 2017. 1853–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].LoPachin RM Gavin T Molecular mechanisms of aldehyde ^ toxicity: a chemical perspective Chem. Res. Toxicol 27 7 2014. 1081–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]