Abstract

Ribonucleoprotein complexes, which contain mRNAs and their regulator proteins, carry out post-transcriptional control of gene expression. The function of many RNA-binding proteins depends on their association with cofactors. Here, we use a genomic approach to identify transcripts associated with DLC-1, a protein previously identified as a cofactor of two unrelated RNA-binding proteins that act in the C. elegans germline. Among the 2732 potential DLC-1 targets, most are germline mRNAs associated with oogenesis. Removal of DLC-1 affects expression of its targets expressed in the oocytes, meg-1 and meg-3. We propose that DLC-1 acts as a cofactor for multiple ribonucleoprotein complexes, including the ones regulating gene expression during oogenesis.

Keywords: germline, RNA-binding protein, LC8, oogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Post-transcriptional mRNA regulation is crucial for gene expression control [1]. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs1) carry out this regulation by forming complexes with messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and each RBP associates with multiple mRNA species. The mRNAs associated with a specific RBP are thought to be coordinately regulated to govern a specific biological function and form a “post-transcriptional RNA operon” [2–4]. The development of the Caenorhabditis elegans germline is a prime example of a process extensively regulated at the post-transcriptional level [5]. C. elegans germ cells follow a defined developmental pathway aimed at the production of gametes [6]. Stem cell proliferation and self-renewal takes place at the distal region of the gonad supported by activation of GLP-1/Notch signaling [7]. At the post-transcriptional level, stem and progenitor cell proliferation is supported by PUF-domain RBPs FBF-1, FBF-2, and PUF-8 [8–11]. As germ cells exit the proliferative zone, they enter meiosis. This switch from proliferation to differentiation is mediated by the activities of diverse post-transcriptional regulators including a KH/STAR domain RBP GLD-1 and cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD-2 [12–14].

After completion of the pachytene stage of meiosis, the germ cells undergo sex-specific differentiation to produce mature gametes. Formation of oocytes in the hermaphrodite germline depends on the activity of GLD-2 in complex with the RRM-motif RBP RNP-8 [15,16] and the translational repressor TRIM-NHL RNA-binding protein LIN-41[17–19]. During differentiation, the oocytes accumulate a number of proteins required for embryogenesis. One such protein family is a set of MEG intrinsically disordered proteins regulating RNA/protein condensate formation in embryos [20–22]. Finally, oocyte maturation requires the activity of redundant TIS11 zinc-finger RBPs OMA-1 and OMA-2 [23]. High-throughput approaches have characterized the targets of many RNA regulators mentioned above including FBF-1 and FBF-2 [24], PUF-8 [25], GLD-1 [26,27], RNP-8 and GLD-2 [16], LIN-41 [19], and OMA-1 [28].

One widespread mechanism regulating the activity of RNA-binding proteins is their association with co-regulators or cofactors. Previous research in our lab found that the activities of two C. elegans germline RBPs, FBF-2 and GLD-1, are promoted by association with a small protein, DLC-1 ([29]; Ellenbecker et al., unpublished). DLC-1 is an LC8-family protein that was originally identified as a component of the dynein motor complex [30,31]. Recent studies suggested that in addition to the dynein motor complex, LC8 proteins contribute to a large number of protein complexes, and function as general cofactors facilitating numerous cellular functions [32]. Supporting this model, we found that the cooperation between DLC-1 and both FBF-2 and GLD-1 is independent of the dynein motor activity. FBF-2 and GLD-1 are dissimilar proteins with opposing biological functions. The fact that DLC-1 cooperates with both, as well as the widespread expression of DLC-1, led us to hypothesize that DLC-1 may facilitate the function of additional RNA-binding proteins.

Here, we performed immunoprecipitation followed by RNA sequencing to determine the transcripts found in association with DLC-1. We found a large number of functionally diverse transcripts associated with DLC-1, supporting broad input by DLC-1 in post-transcriptional regulation. Although DLC-1 might bind RNA directly [33,34], we expect that the majority of transcripts were recovered through indirect association of DLC-1 with RNA-binding proteins. A large number of DLC-1-associated transcripts contribute to oogenesis, a process disrupted in dlc-1 mutants. We report that two oocyte genes, meg-1 and meg-3, depend on DLC-1 for regulation of their expression in the germline and maturing oocytes, which suggests that DLC-1 contributes to regulation of gene expression at this developmental stage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nematode Strains and Culture

C. elegans strains (Table 1) were cultured as per standard protocols [35] at 20°C or 24°C (if expressing GFP-tagged genes). The 3xFLAG::dlc-1(mntSi13); dlc-1(tm3153) rescued strain UMT290 was generated by first crossing UMT281 with him-8(tm611) and then with dlc-1(tm3153)/qC1 III. The UMT376 strain expressing both 3xFLAG::DLC-1 and OMA-1::GFP was generated by crossing UMT281 and TX189.

Table 1.

Nematode strains used in this study

| Genotype | Description | Strain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgene | |||

| mntSi13[pME4.1] II; unc-119(ed3)III | dlc-1 prom::3xFLAG::dlc-1::dlc-1 3’UTR | UMT281 | [29] |

| unc-119(ed3) III; teIs1 | oma-1 prom::oma-1::GFP | TX189 | [57] |

| mntSi13[pME4.1] II; unc-119(ed3) III; teIs1 [pRL475] | dlc-1 prom::3xFLAG::dlc-1::dlc-1 3’UTR; oma-1 prom::oma-1::GFP | UMT376 | This study |

| Mutant strains + Transgene | |||

| mntSi13 [pME4.1] II; dlc-1(tm3153)III | dlc-1 prom::3xFLAG::dlc-1::dlc-1 3’UTR | UMT290 | This study |

| Mutant strains | |||

| meg-1(tn1722) | GFP::3xFLAG::MEG-1 | DG4213 | [19] |

| meg-3(ax3054) | MEG-3::meGFP | JH3503 | [58] |

| meg-3(ax3051); meg-4(ax2080) | MEG-3::OLLAS; MEG-4::3xFLAG | JH3374 | [58] |

| dlc-1(tm3153)/qC1 III | UMT222 | [29] | |

RNA Interference Assays

RNAi was performed by feeding synchronized L1 larvae with HT115(DE3) E. coli transformed with the relevant plasmids for 3 days at 24oC as described before [36]. The identity of all plasmids used for RNAi was confirmed by sequencing.

Immunostaining and Imaging

The fixation and immunostaining procedure has been previously described in [29]. Prior to application of primary anti-FLAG antibody, dissected gonads were pre-blocked with PBS/0.1%BSA/0.1%Tween-20/10% normal goat serum (PBS-T/NGS) for 1 hour at room temp. Descriptions of the antibodies and relevant dilutions are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Gonads were incubated in primary antibody solution overnight at 4oC followed by 3 washes with PBS-T and then with secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature and washed 3 times with PBS-T. Coverslips were mounted to immunostained gonads with Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs). Epifluorescence images were captured using a Leica DFC3000G camera attached to a Leica DM5500B microscope using LAS-X software (Leica). Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. Image processing including assembly of full-length germlines from several fields of view was performed in Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation of 3xFLAG::DLC-1 was performed with a protocol adapted from [37] using mouse anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) or mouse non-specific IgGs as controls, see supplemental file S1 for details. RNA was extracted from the eluents and input samples suspended in TRIzol using the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (ZymoResearch) and quantified by Qubit 3.0 fluorometer RNA HS assay kit (ThermoFisher). Immunoprecipitated RNA derived from anti-FLAG pulldowns averaged 8 ng/μL across five replicates, while IgG-associated RNA was undetectable by Qubit. Immunoprecipitation of 3xFLAG::DLC-1 from the UMT376 strain followed the same procedure, except the RNA extraction procedure was omitted.

GST Pulldowns

Full-length proteins were amplified from Bristol N2 cDNA and cloned into pDEST17 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to generate 6xHis-tagged proteins. GST-tagged full length DLC-1 has been previously described [29]. All constructs were sequenced and transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3) for expression. Expression of 6xHis-tagged proteins was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG at 15°C for 16–18 hrs. Expression of GST-tagged DLC-1 was induced with 1 mM IPTG at 37°C for 4 hrs. The GST pulldown assay was performed as described in [29].

Western Blots

Western blots were used to evaluate nematode gene expression, immunoprecipitation of 3xFLAG::DLC-1, and to determine the outcome of GST::DLC-1 pulldowns, as previously described [29]. Detailed information for the antibodies is in Supplemental Table 1. Blots were developed using Luminata Western HRP reagent (EMD Millipore) and imaged using ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics

Library preparation and sequencing of the total and immunoprecipitated RNA was performed at the Washington State University Spokane Genomics Core. Total RNA was oligo-dT primed to generate the input libraries while immunoprecipitated RNA was processed without enrichment. Total RNA and IP RNA (5 replicates each) libraries were pooled together to run on two Illumina HiSeq2500 lanes for a total of 439.61 million reads with a length of 100bp. Reads were almost equally distributed among these samples, 93.4% reads have a quality score higher than Q30. RNA-seq data is deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE 115281).

Details of RNA-seq data analysis are in Supplemental File S1. Briefly, sequenced reads were trimmed with Trim Galore! [38] to remove Illumina adapter sequences (v 0.4.2) and filtered for rRNA sequences using Bowtie2 (2.3.0) [39]. Reads that did not map to the rRNA sequences were then applied to the workflow adapted from a previous report [19]. The reads were mapped to WBcel235/ce11 genome using RNA Star (v 2.5.2b-0) [40]. Normalization and enrichment calculations for the RIP experiments were performed using DESeq2 (version 1.12.3) [41]. Genes were considered enriched when they had a log2foldchange > 1 and Padj < 0.01. Genes that did not correspond to the annotated features of the current reference genome were removed from the list of enriched genes. The finalized list of 2732 genes enriched in the 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP is reported in File S2.

For 3’UTR motif analysis, all available 3’UTRs for the genes enriched in the 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP were obtained through Wormbase (http://parasite.wormbase.org/biomart/martview/) and analyzed using Discriminative Regular Expression Motif Analysis (DREME) tool available on MEMEsuite.org [42]. A library of 3’ UTRs for all other genes not enriched in 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP was used as a control to evaluate the number of motif occurrences using the Find Individual Motif Occurrences (FIMO) tool available on MEMEsuite.org [43].

RESULTS

RIPseq of FLAG::DLC-1 from the intact animal

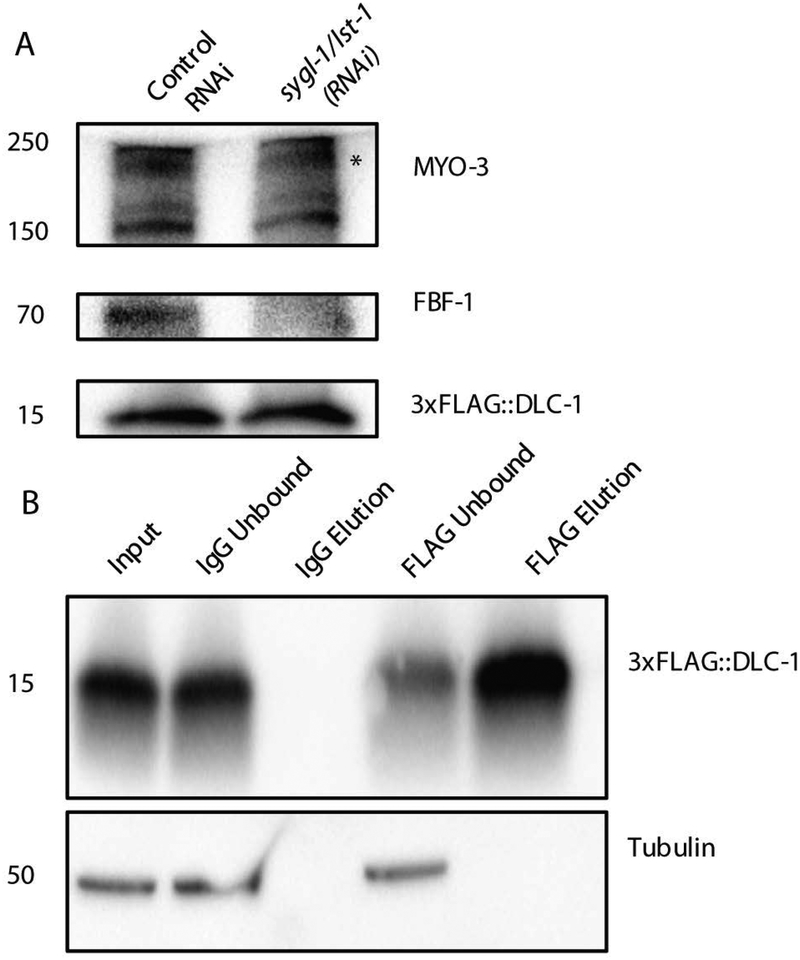

Using a single-copy insertion technique, we generated a transgene encoding 3x-FLAG tagged DLC-1 under the control of its endogenous promoter and 3’UTR [29]. This transgene was used to complement the dlc-1(tm3153) deletion, which renders the mutant animals sterile (at 24oC) or causes maternal-effect embryonic lethality (at 15oC). The 3xFLAG::DLC-1 transgene largely rescued dlc-1 deletion hermaphrodite fertility and embryonic viability at 24oC (99% embryonic viability, N=797; 100% fertility, N=794). We concluded that the transgenic 3xFLAG-tagged DLC-1 is fully functional in vivo. 3xFLAG-tagged DLC-1 was expressed throughout the germline, from the distal stem cells and progenitors to the oocytes [29], consistent with the previously reported endogenous expression pattern [44]. To test whether 3xFLAG::DLC-1 was also expressed in somatic tissues, we disrupted germline tissue formation in 3xFLAG::DLC-1 animal by double RNAi against sygl-1 and lst-1 [45]. Loss of germ cells was confirmed by a decrease in the levels of germline-specific protein FBF-1 (Fig. 1A). Western blotting detected expression of 3xFLAG::DLC-1 in sterile worms following double sygl-1/lst-1(RNAi), suggesting that 3xFLAG::DLC-1 is also abundant in somatic tissues (Fig. 1A), consistent with a previous report [46].

Figure 1. Expression and Immunopurification of 3xFLAG::DLC-1.

A) Western blot of 3xFLAG::DLC-1 worms treated with control RNAi or sygl-1/lst-1(RNAi) that prevents germ cell proliferation. Sterility was visually confirmed in sygl-1/lst-1(RNAi) treatment. 50 worms per treatment were collected and boiled in 2x loading buffer for 30 min before loading onto gel. Loss of germline tissue is followed through decreased abundance of FBF-1 protein. 3xFLAG::DLC-1 does not decrease in the background of sygl-1/lst-1(RNAi). Somatic myosin MYO-3 is used as loading control. Asterisk denotes the 210 kD myosin A heavy chain. Molecular weight of the protein bands is denoted by the numbers on the left side of western blot images.

B) 3xFLAG::DLC-1 is specifically immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (FLAG Elution), but not in the IgG control. The anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation reduces the amount of tagged protein in the lysate (FLAG Unbound), demonstrating an efficient IP. Tubulin is not recovered in either the IgG control or FLAG eluents.

We expect that the transgenic 3xFLAG::DLC-1 is able to enter all relevant protein complexes, including complexes with RNA-binding proteins, and allow for isolation of target mRNAs. For 3xFLAG::DLC-1 immunoprecipitation, we used the rescued strain where the transgene is the sole source of DLC-1. We immunoprecipitated 3xFLAG::DLC-1 from replicate lysates of young adult nematodes (24 hrs post-L4 stage; Fig. 1B). The immunoprecipitation of 3xFLAG::DLC-1 was specific, and not observed in the control with non-specific IgGs. The anti-FLAG antibodies were also selective as no immunoprecipitation of tubulin was observed (Fig. 1B). In agreement with our hypothesis, we detected RNA in the 3xFLAG::DLC-1 immunoprecipitate (108–432 ng/300 mg input tissue), but not in the non-specific IgG immunoprecipitate.

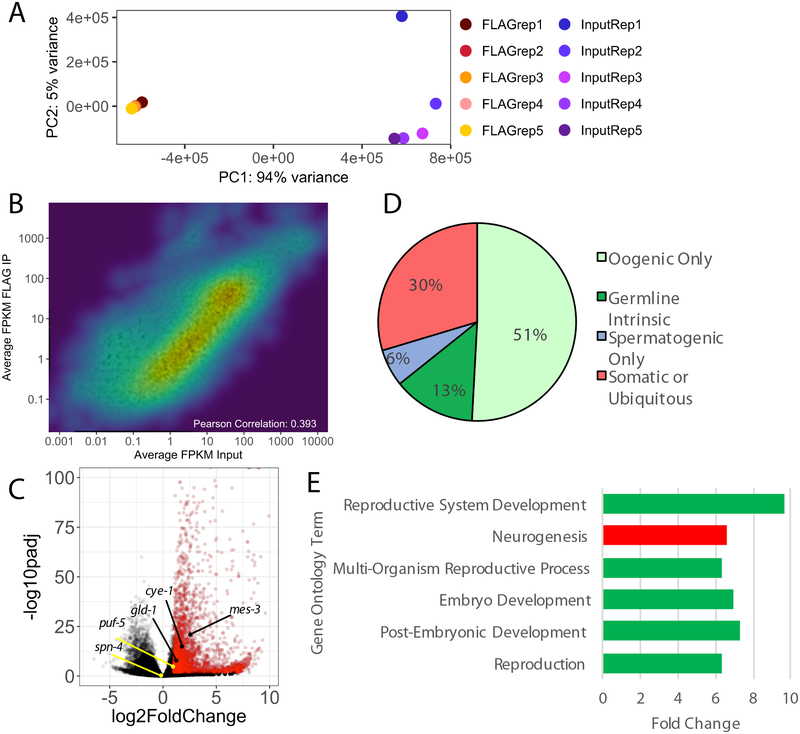

Total RNA associated with DLC-1-containing RNPs was purified and sequenced in five independent biological replicates. In parallel, we sequenced the mRNAs in five replicates of the corresponding input lysates after enriching them with oligo(dT) selection. We did not sequence the material isolated with non-immune IgG since an undetectable amount of isolated RNA was expected to result in amplification artifacts during sequencing library preparation. We mapped the sequencing reads from all replicates to the WBcel235/ce11 version of the C. elegans genome and excluded the reads mapping to the ribosomal RNA genes from further analysis. We used principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate the variability of our replicates. The PCA analysis indicated that the 3xFLAG::DLC-1 IP replicates tightly clustered together (Fig. 2A) suggesting their similarity and reproducibility. The input samples were clearly segregated from the immunoprecipitated mRNAs (Fig. 2A). We observed only a weak correlation between average fragment abundance of transcripts in 3xFLAG::DLC-1 IP and in the input RNAseq (R2 ~ 0.4) suggesting that the procedure didn’t simply return the most abundant mRNAs in the samples (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Identification and Characterization of DLC-1-Associated RNAs.

A) Principal component analysis of five 3xFLAG::DLC-1 replicate RNA immunoprecipitations (RIPs; FLAGrep1–5) compared against five inputs (InputRep1–5). PC, Principal Component. PC1 explains 94% of variance, and PC2 explains 5% of variance.

B) RNA-seq enrichment heatmap showing the distribution of average RIP FPKM versus average Input FPKM. Overall, the correlation is low (R2=0.393).

C) Volcano plot of 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIPseq. Inverse of the adjusted statistical significance (-log10(Padj); y-axis) is plotted against the average fold change (anti-FLAG/Input) for five samples (x-axis). Points have been colored by enrichment, red are enriched in 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP (Padj < 0.01 and log2FoldChange > 1; 2732 genes; File S2). The FBF-2 or GLD-1 target mRNAs cye-1, gld-1, and mes-3 are enriched in 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP. The GLD-1 target mRNAs puf-5 and spn-4 were not enriched in the RIP.

D) DLC-1-associated mRNAs are enriched for genes in the oogenic transcriptome. Comparison of DLC-1-associated genes against genes associated with a specific spermatogenic or oogenic program as defined in [47]. Genes termed “Somatic or Ubiquitous” did not fall under the other 3 specified categories.

E) Gene ontology analysis reveals that DLC-1 associated genes are involved in reproduction, development, and neurogenesis. The categories associated with germline expression (reproduction, development) are colored green, while neurogenesis associated with somatic expression is colored red. Analysis was performed using the Gene Enrichment Analysis (GEA) tool available on https://wormbase.org/tools/enrichment/tea/tea.cgi [49]. Fold change is expressed as the ratio of the enriched genes observed for the category over the number of genes expected to be recovered.

To identify transcripts enriched in the DLC-1 immunoprecipitations, we used DESeq2 to calculate log2 fold change [41] of the RNAs in the DLC-1 eluates relative to their abundance in the oligo(dT)-enriched inputs. While RNAs in DLC-1-containing RNPs appeared enriched several fold, the majority of RNAs in the lysate were moderately depleted compared to the IP sample (Fig. 2C). We identified 2732 RNAs exhibiting a statistically significant (adjusted P<0.01) enrichment of two-fold or greater in the DLC-1 immunoprecipitation (highlighted in red in Fig. 2C; Supplemental File S2). This number of transcripts is ~2.3-fold greater than typically recovered by isolation of a single RBP. These transcripts included 2206 protein-coding mRNAs, 346 long non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs, ncRNAs, antisense RNAs), and 87 small non-coding RNAs including snoRNAs and snRNAs (Table 2). We concluded that DLC-1 predominantly associates with mRNA-containing RNPs, and the non-coding RNAs might appear enriched in DLC-1 IP since the RNAs were not oligo(dT) selected for library preparation.

Table 2.

DLC-1 predominantly associates with protein-coding mRNAs

| Biotype* | # of Enriched Genes with Biotype | % of Enriched Genes |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA | 2206 | 81% |

| long noncoding | 346 | 13% |

| short noncoding | 87 | 3% |

| pseudogene | 86 | 3% |

Biotype analysis of DLC-1 associated genes based on assigned biotype from C. elegans genome annotation WS236 performed with Wormbase Parasite. “mRNA” represents “protein coding” category. Long noncoding is comprised of lincRNA, antisense, ncRNA. Short noncoding includes snRNA and snoRNA.

7 DLC-1-associated RNAs have no biotype annotation.

The mRNAs in DLC-1-containing complexes included mes-3, cye-1, and gld-1 (previously-characterized targets of FBF-2 and GLD-1 that depend on DLC-1 for their regulation [29], Ellenbecker et al., unpublished), but not puf-5 or spn-4 (GLD-1 targets that were not affected by dlc-1 loss; Fig. 2C). We conclude that the mRNAs identified in the DLC-1-containing RNPs (DLC-1-associated mRNAs) are likely relevant to DLC-1 biological activity.

Many DLC-1-associated transcripts (1756 of 2732 transcripts; Table 3) belong to the general oogenic mRNA program as defined in [47]. This overlap was statistically significant by the hypergeometric distribution test (P<1E−90). DLC-1-associated mRNAs were depleted of spermatogenesis transcripts, reflecting preparation of IP samples from young adult (oogenic) hermaphrodites (Table 3). We also compared overlap of our transcripts with a different dataset of transcripts that increase in abundance over twofold in the oogenic germlines as compared to spermatogenesis [48] and similarly recovered a significant overlap (321 of 2732; P<1E−53; Table 3). Based on analysis of overlap with the two distinct datasets, a large number of DLC-1-associated mRNAs are related to oogenesis. Despite the enrichment of germline transcripts, many somatic or ubiquitous mRNAs were also present (828 of 2732; Fig. 2D) in agreement with DLC-1 expression in somatic tissues. Analysis of the DLC-1 targets by Gene Ontology functional annotation clustering [49] identified the expected enrichment of transcripts associated with development and reproduction (Fig. 2E). Some enriched transcripts were related to neurogenesis (Fig. 2E), a process similarly associated with extensive post-transcriptional regulation and RNA transport [50–52]. We concluded that despite broad expression of 3xFLAG::DLC-1, it enters into mRNP complexes predominantly in the germline and neuronal tissues.

Table 3.

DLC-1-associated mRNAs are enriched in oogenesis-related transcripts

| Transcriptome | # of Overlapped Genes | % Overlap | Representation Factor | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oogenic Transcriptome [47] | 1756 | 19% | 1.4 | 6.82E-91 |

| Spermatogenic Transcriptome [47] | 533 | 8% | 0.6 | 3.23E-63 |

| Enriched in Oogenesis [48] | 321 | 32% | 2.4 | 5.3E-54 |

| Enriched in Spermatogenesis [48] | 115 | 13% | 1 | 0.403 |

DLC-1-associated mRNAs were compared against oogenic or spermatogenic transcriptomes. Representation factor and significance of overlap was evaluated by hypergeometric distribution test using the gene list comparison tool available at nemates.org/MA/progs/overlap_stats.html. Representation factor above 1.0 indicates more overlap than expected between independent groups, and below 1.0 indicates less overlap than expected.

Binding motifs in the 3’UTRs of mRNAs isolated with DLC-1

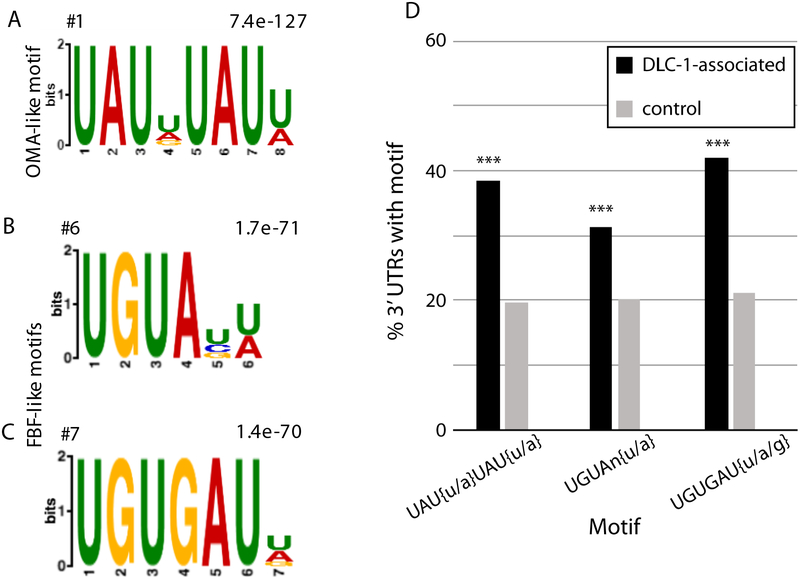

To test whether the mRNAs isolated with DLC-1 contain RBP binding motifs, we searched for sequences enriched in the 3’UTRs of this gene set. Using DREME [42], we identified the enriched motifs in the 3’UTR set compared to shuffled sequences (Fig. 3A–C; Supplemental File S3). Based on previously discovered DLC-1 association with FBF-2, we expected to recover motifs consistent with the presence of FBF targets. Indeed, within the ten most significant recovered motifs, we found two motifs similar to those recognized by PUF family RNA-binding proteins that includes FBF-2 (Fig. 3B, C; [24,53]). The top-scoring motif is a low-affinity OMA-1 binding site (UA[a/u]-rich repeats, Fig. 3A; [54]); the remaining high ranking motifs were not among the previously characterized targets of C. elegans RBPs. Since the DREME analysis estimates motif enrichment in comparison to shuffled 3’UTR sequences, it might return motifs that are highly represented across C. elegans 3’UTRs. To evaluate this possibility, we compared the prevalence of the motifs uncovered in the 3’UTRs of RIPseq mRNA set to their frequency across the 3’UTRs of the transcripts not associated with DLC-1. We find that all motifs were significantly enriched in the DLC-1-associated 3’UTR set with P values calculated by chi-square test smaller than 10−4 (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. 3’UTR Motifs in mRNAs Associated with DLC-1.

A-C) Motifs identified by DREME [42] analysis of the annotated 3’ UTRs of the DLC-1 associated mRNAs; WebLogo, rank and P-value (Fisher’s Exact test) are shown.

A) Top overrepresented motif similar to OMA-1-binding element [54].

B, C) Short motifs similar to the FBF-binding element (UGUNNNAU, [53]) were recovered from the top 10 most enriched motifs. The top 20 most represented motifs in the 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP are reported in File S3.

D) Motifs in A-C are significantly enriched in the DLC-1 associated 3’UTRs compared to the control set of C. elegans 3’UTRs. Motifs in A-C were used as input for FIMO [43] to scan DLC-1 associated UTRs or all other C. elegans 3’UTRs (at P value < 0.001). The graph plots percentage of genes containing a specific motif as the ratio of observed motif occurrences (with a P < 0.001) against the size of the input library for enriched in 3xFLAG::DLC-1 RIP (black) or control 3’UTRs (grey). Differences in motif prevalence between sets of 3’UTRs were evaluated by chi-square test; *** P<0.0001.

Identification of candidate DLC-1-containing RNPs through overlap in mRNAs

If DLC-1 is an integral component of regulatory RNPs, we expect to recover a significant overlap between mRNAs recovered in the DLC-1 IP and the documented targets of regulatory RNA-binding proteins. Initially, we compared DLC-1-associated mRNAs to those recovered in complex with FBF-2 [24] and GLD-1 [27]. We found that the set of DLC-1-associated mRNAs significantly overlapped with both FBF-2 targets (412 overlapped genes; hypergeometric distribution P<10−60) and GLD-1 targets (44 overlapped genes; hypergeometric distribution P<10−3; Table 4) in agreement with the known molecular and genetic interaction of DLC-1 with these RBPs ([29], Ellenbecker et al., unpublished). We concluded that overlap comparison has the potential to identify the mRNAs regulated with involvement of DLC-1.

Table 4.

DLC-1-associated mRNAs are shared with several germline RBPs

| RBP Transcriptome | # of Overlapped Genes | % of RBP targets in overlap | Representation Factor | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBF-2 [24] | 412 | 30% | 2.2 | 5E-61 |

| FBF-1 [24] | 547 | 26% | 1.9 | 1.23E-60 |

| GLD-2 [16] | 119 | 22% | 1.6 | 7.48E-08 |

| GLD-1 [27]* | 44 | 23% | 1.7 | 2.9E-04 |

| LIN-41 [19] | 188 | 17% | 1.2 | 0.001 |

| OMA-1 [28] | 173 | 16% | 1.2 | 0.02 |

| RNP-8 [16] | 129 | 15% | 1.1 | 0.194 |

| FOG-3 [47] | 94 | 13% | 1 | 0.328 |

| FOG-1 [47] | 6 | 7% | 0.5 | 0.062 |

| PUF-8 [25] | 6 | 4% | 0.3 | 2.5E-05 |

The 2732 RNAs enriched in DLC-1 RIP were compared for overlap with known RBP mRNA targets. # of overlapped genes is the number of DLC-1 associated RNAs that overlap with the mRNA targets for a specified RBP. Representation and P values were derived as in Table 3.

Similar overlap was observed using alternate GLD-1 target mRNA datasets from T. Schedl, personal communication, 19% overlap, P = 7.47E-07 and from [26], 16% overlap, P = 0.009.

We then compared the mRNAs isolated with DLC-1 to the previously published targets of several germline RNA-binding proteins including FBF-1 [24], GLD-2 [16], RNP-8 [16], LIN-41 [19], OMA-1 [28], FOG-3 and FOG-1 [47], and PUF-8 [25]. We observed significant (hypergeometric distribution P<0.05) overlap of DLC-1-associated mRNAs with the targets of FBF-1 (P<10−59), GLD-2 (P<10−7), LIN-41 (P<0.01), and OMA-1 (P=0.02; Table 4). The significant overlap with FBF-1 targets was expected since the targets of FBF-1 and FBF-2 are highly similar [24].

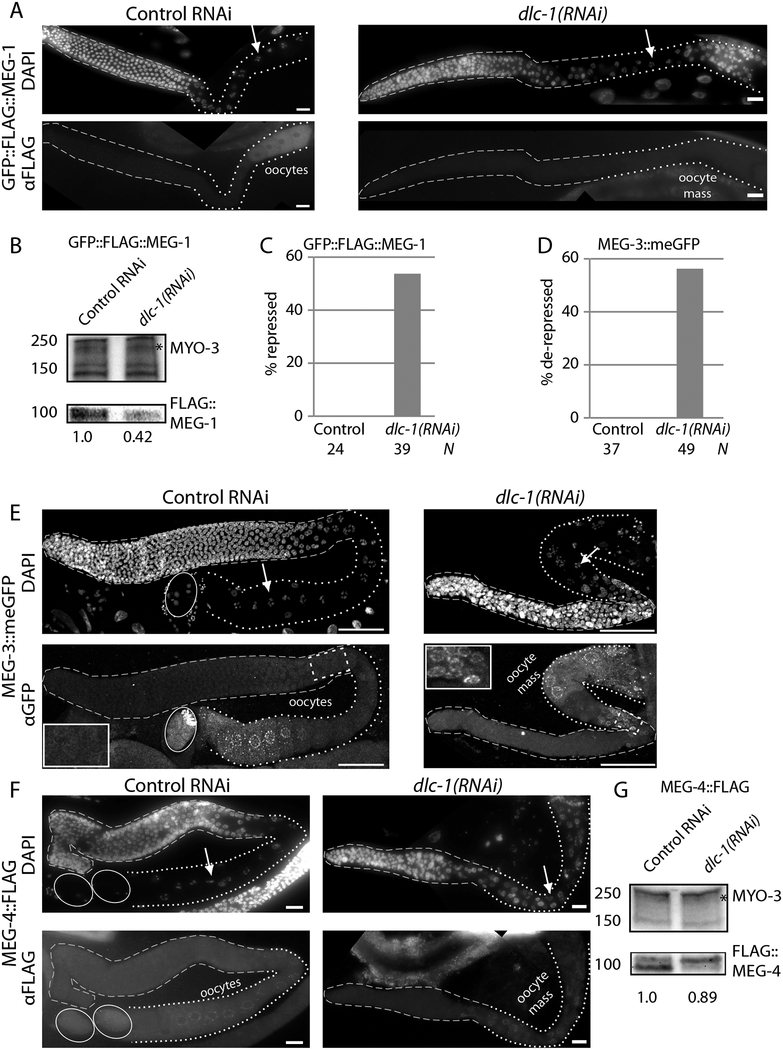

DLC-1 contributes to several mechanisms of germline translational control

As we hypothesized that DLC-1 has the potential to contribute to the regulatory activity of multiple germline RNA-binding proteins, we sought to test if DLC-1 might affect the expression of its other associated mRNA targets, beyond the previously identified targets of FBF-2 and GLD-1. We focused on a set of MEG proteins that are only expressed in the oocytes and early embryos. We chose meg-3 since its regulation has not been previously studied, and used meg-1 and meg-4 for comparison and contrast. Endogenously tagged GFP::FLAG::MEG-1, MEG-3::meGFP, and MEG-4::FLAG are expressed in the −1 to −3 oocytes in the wild type background [19,21]. Despite similar protein expression patterns and related function, mRNAs encoding the MEG proteins might be differentially regulated as they have been recovered in association with distinct RNA-binding proteins. meg-1 mRNA was found in complexes with GLD-1, GLD-2, LIN-41, RNP-8, and FBF-1 [16,19,24] and its expression is regulated by LIN-41, OMA-1, and OMA-2 [19]. meg-3 mRNA has not been identified in complex with germline RBPs so far, and meg-4 mRNA was recovered with GLD-2 and RNP-8 [16]. All three meg mRNAs are among the DLC-1-associated transcripts.

Following depletion of DLC-1 by RNAi, we assessed the expression of MEG proteins in the resulting sterile germlines. Similar to dlc-1(tm3153) mutant, dlc-1(RNAi) at 24oC resulted in initiation of oocyte differentiation followed by deterioration of gametes and formation of an “oocyte mass” at the proximal end of the gonad. The expression of GFP::FLAG::MEG-1 was lost in 52% of dlc-1(RNAi) sterile germlines (Fig. 4A,C; n = 39), suggesting that DLC-1 contributes to the activation of GFP::FLAG::MEG-1 expression. A decrease in GFP::FLAG::MEG-1 expression was also observed by Western blot (Fig. 4B). By contrast, in dlc-1(RNAi) background expression of MEG-3::meGFP was expanded in the proximal region of the gonad and extended into the late pachytene region in 51% of germlines (Fig. 4D,E; n = 49). Finally, the expression of MEG-4::FLAG was not affected by dlc-1(RNAi) (Fig. 4F,G; n = 35), although Western blot suggested that MEG-4::FLAG post-translational modifications were altered compared to the control (Fig. 4G). We conclude that DLC-1 might contribute to the function of the proteins activating MEG-1 expression as well as translational repressors of MEG-3.

Figure 4. DLC-1 Promotes Expression Control of Its Targets.

A, E-F) The expression of CRISPR-tagged GFP::3xFLAG::MEG-1, MEG-3::meGFP, or MEG-4::3xFLAG was evaluated in dissected, fixed, and immunostained gonads of worms treated with control or dlc-1(RNAi). DNA was stained by DAPI; arrows point to nuclei in diplotene characteristic of the oocytes. In the immunostained panels, gonads are outlined with dashed lines, while the oocytes (control treatment) or oocyte masses following dlc-1(RNAi) are identified with dotted lines. Enlarged regions in the insets of MEG-3::meGFP germlines are marked by yellow dashed boxes. Ovals in MEG-3::meGFP and MEG-4::FLAG control panels outline embryos. Images in panels A and F were obtained using an epifluorescent microscope, while images in panel E were obtained using a confocal microscope. Scale bars: 50 μM.

B, G) Representative Western blots of GFP::FLAG::MEG-1 (B) and MEG-4::FLAG (G) adult worms treated with dlc-1(RNAi) or control RNAi (MEG-1, 50 worms/lane; MEG-4, 100 worms/lane). Sterility was visually confirmed following dlc-1(RNAi) treatment. Band density was quantified using Bio-Rad Image Lab v5.1 software from the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP. The intensity of FLAG-tagged transgene band was normalized to the intensity of somatic myosin MYO-3 for loading control and then scaled to 1 in control RNAi (reported below the anti-FLAG Western blot for each protein). GFP::FLAG::MEG-1 is depleted after dlc-1(RNAi) treatment, while MEG-4::FLAG levels are largely unchanged following the same RNAi treatment. Molecular weight of the protein bands is denoted by the numbers on the left side of Western blot images. Asterisk marks the 210 kD myosin A heavy chain.

C, D) Bar plots showing the percentage of germlines exhibiting abnormal repression or expression of GFP::FLAG::MEG-1 or MEG-3::meGFP respectively after control or dlc-1(RNAi). N, number of germlines scored (below the bars). Expression of MEG-4::FLAG did not change following dlc-1(RNAi), N = 35. Effectiveness of dlc-1(RNAi) was confirmed as 100% of treated nematodes became sterile.

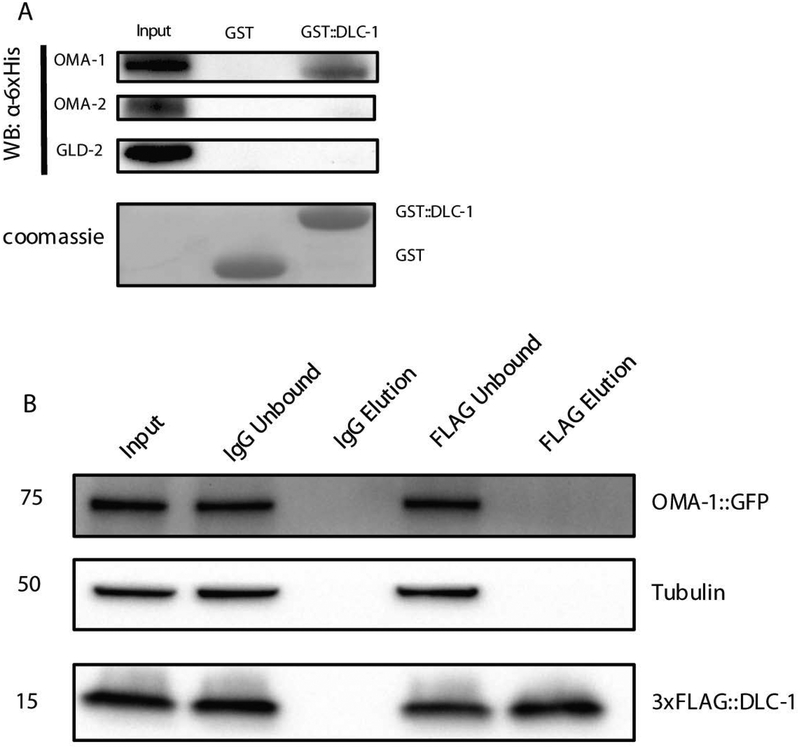

DLC-1 interacts with OMA-1 in vitro

DLC-1 might facilitate activation of MEG-1 expression by interacting with its regulators. Activation of MEG-1 expression in the oocyte requires the activities of OMA-1, OMA-2, and GLD-2 [19], and the overlaps between the mRNAs in complex with DLC-1 and GLD-2 and OMA-1 targets were significant. Based on these results, we tested OMA-1, OMA-2, and GLD-2 for direct interaction with DLC-1. GST pulldown assays performed with bacterially-expressed proteins indicated that DLC-1 could directly interact with OMA-1, but not with GLD-2 or OMA-2 (Fig. 5A). Selective interaction of DLC-1 with OMA-1, but not OMA-2 was surprising since OMA-1 and OMA-2 are similar (64% identity in the coding sequences) and largely functionally redundant [23]. The absence of detectable interactions between DLC-1 and GLD-2 or OMA-2 in vitro might result from the lack of other cofactors or post-translational modifications that may facilitate DLC-1 binding or indicate that the interactions are indirect. To explore DLC-1/OMA-1 interaction in vivo, we performed FLAG::DLC-1 immunoprecipitation from a strain that was also expressing GFP-tagged OMA-1. We find that OMA-1 did not co-immunoprecipitate with FLAG::DLC-1 (Fig. 5B) suggesting that the protein interaction might be unstable, occurs only in a subset of OMA-1 RNP complexes, or is an artifact of an in vitro experiment. A transient interaction of DLC-1 with OMA-1 provides one possible mechanism for DLC-1 input in RNA regulation during oogenesis.

Figure 5. DLC-1 Binds OMA-1 In Vitro.

A) Full length 6x-His-tagged OMA-1, OMA-2, and GLD-2 (detected by Western blotting) were tested for binding to GST-tagged DLC-1 (Coomassie). GST alone was used as a control.

B) 3xFLAG::DLC-1 is specifically immunoprecipitated from 3xFLAG::DLC-1; OMA-1::GFP worms with anti-FLAG antibody (FLAG Elution), but not in the IgG control. Tubulin is not recovered in either the IgG control or FLAG eluents. OMA-1::GFP is not recovered in the FLAG::DLC-1 eluents,.

DISCUSSION

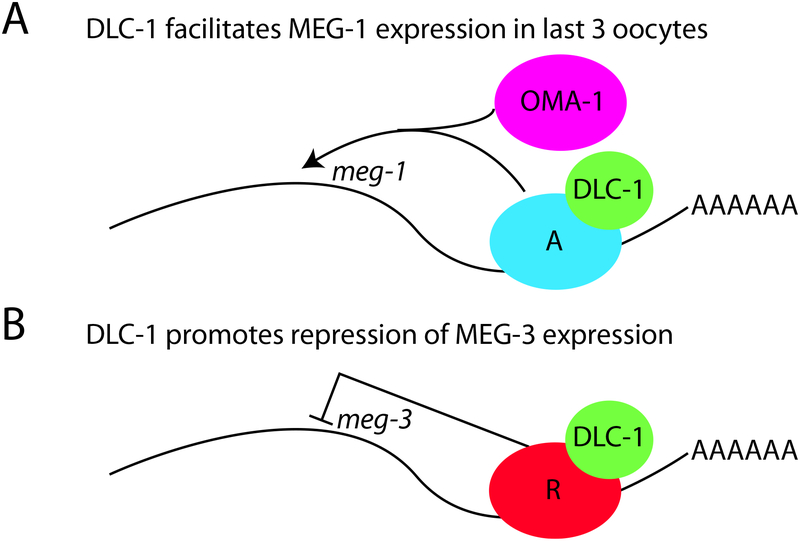

In this study, we report that the LC8 family protein DLC-1 enters multiple RNP complexes that collectively contain thousands of mRNAs. Our findings identify new requirements for DLC-1 in the control of both translational activation and repression during oocyte differentiation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Model of DLC-1 Involvement in Different Modes of Post-Transcriptional RNA Regulation.

A) A subset of DLC-1-associated transcripts including meg-1 requires DLC-1 for their activation in the oocytes. DLC-1 associates with these transcripts through the activator proteins, “A” in the schematic. Both GLD-2 and OMA-1/2 contribute to meg-1 activation [19], and DLC-1 may play a role in the transient recruitment of OMA-1 required for this process.

B) Other DLC-1-associated transcripts such as meg-3 require DLC-1 for their repression. These mRNA targets that also include gld-1, cye-1 and mes-3 are derepressed upon inactivation of DLC-1. DLC-1 associates with these transcripts through translational repressors, denoted “R”. DLC-1 is required for function of these translational repressors including FBF-2, GLD-1, and likely others. The model does not indicate the actual location of proteins on the transcript nor does it represent all components of regulatory RNP complexes.

We find that DLC-1 is incorporated in multiple RNP complexes expanding upon our previous results of DLC-1’s role in RNA regulation by two C. elegans RBPs, FBF-2 and GLD-1 ([29]; Ellenbecker et al., unpublished). The number of DLC-1-associated transcripts (2732) is greater than the typical number recovered with single RBPs, which is 1000–2000. This may suggest that DLC-1 acts as a cofactor for many RNP complexes. The mRNAs associated with DLC-1 are related to development and reproduction as well as neurogenesis, reflecting previously reported sites of DLC-1 expression and function. DLC-1 and other dynein motor components are required for the function of C. elegans ciliated neurons [55], but a role for DLC-1 in neuronal post-transcriptional gene expression control has not been previously reported. Many DLC-1-associated mRNAs belong to the oogenic transcriptome, which is consistent with DLC-1 expression in germlines undergoing oogenesis in young adult nematodes used for sample preparation and with disruption of oogenesis observed in dlc-1 mutant.

Among the recovered mRNAs are previously identified transcripts that require DLC-1 for regulation of their expression in the germline ([29]; Ellenbecker et al., unpublished). In addition, we identified new DLC-1 contributions to translational repression at the end of meiotic pachytene and translational activation in the oocytes (Fig. 6). Loss of DLC-1 causes derepression of MEG-3 in pachytene cells. Since the regulators that affect MEG-3 expression are unknown, we hypothesize that DLC-1 might contribute to the function of additional translational repressors beyond FBF-2 and GLD-1. By contrast, oocyte expression of MEG-1 was lost after dlc-1 knockdown. Activation of MEG-1 expression in the oocytes requires the activities of GLD-2 and OMA-1/OMA-2 [19]. We found direct interaction of DLC-1 with OMA-1 using an in vitro system, which might be relevant to activation of MEG-1 expression. However, we were unable to detect co-immunoprecipitation of OMA-1 with DLC-1 in vivo, thus the interaction might be transient or only reflect a small subset of OMA-1 regulatory RNP complexes. Alternatively, there is a possibility that the interaction is absent in vivo. Expression of MEG-4, another member of MEG protein family, was not affected by the depletion of DLC-1, although MEG-4 post-translational modifications were altered in the sterile dlc-1(RNAi) germlines. Further studies are needed to determine whether this differential protein modification is due to disrupted oogenesis or is caused specifically by the absence of DLC-1.

We scanned the 3’UTRs of meg-1, meg-3, and meg-4 for the presence of motifs enriched in DLC-1-associated mRNAs and found that each 3’UTR contained several instances of the enriched motif shown in Fig. 3B, while meg-1 and meg-4 3’UTRs additionally contained the motif shown in Fig. 3C. Therefore, simple presence or absence of these enriched motifs is unlikely to account for differential contribution of DLC-1 to the regulation of meg transcripts. Future experiments will test the importance of these motifs for regulation of meg-1 and meg-3 expression. Diverse contributions of DLC-1 to post-transcriptional control are enabled by its incorporation in a variety of regulatory complexes (Fig. 6). Binding to DLC-1 causes structural changes and/or facilitates higher-order complex assembly of its partner proteins [32,56], likely relevant to DLC-1 function in RNP complexes. Future work will determine DLC-1’s contribution to OMA-1 function as well as identify other components of DLC-1-containing RNP complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Voronina lab members, Jennifer Wang, Tiago Antao, Micah Gearhart, Tim Schedl, Geraldine Seydoux, and two anonymous reviewers for experimental suggestions, provision of reagents, bioinformatics support, or comments on the manuscript. Some nematode strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (P40OD010440). Confocal microscopy was facilitated by NIH awards S10OD021806 and P20GM103546. This work was supported by NIH R01GM109053 grant to EV, UM Research Award to ME, and UM ASUM award to ND. Funding sources had no involvement in study design and execution or writing the report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in the paper: RBP – RNA-binding protein; RNP – ribonucleoprotein complex; IP – immunoprecipitation; RIP – RNA immunoprecipitation

References

- [1].Morris AR, Mukherjee N and Keene JD (2010). Systematic analysis of posttranscriptional gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2, 162–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Keene JD (2007). RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet 8, 533–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Imig J, Kanitz A and Gerber AP (2012). RNA regulons and the RNA-protein interaction network. Biomol Concepts 3, 403–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Blackinton JG and Keene JD (2014). Post-transcriptional RNA regulons affecting cell cycle and proliferation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 34, 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nousch M and Eckmann CR (2013). Translational control in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line. Adv Exp Med Biol 757, 205–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pazdernik N and Schedl T (2013). Introduction to germ cell development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Adv Exp Med Biol 757, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kimble J and Crittenden SL (2007). Controls of germline stem cells, entry into meiosis, and the sperm/oocyte decision in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23, 405–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhang B, Gallegos M, Puoti A, Durkin E, Fields S, Kimble J and Wickens MP (1997). A conserved RNA-binding protein that regulates sexual fates in the C. elegans hermaphrodite germ line. Nature 390, 477–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Crittenden SL et al. (2002). A conserved RNA-binding protein controls germline stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 417, 660–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lamont LB, Crittenden SL, Bernstein D, Wickens M and Kimble J (2004). FBF-1 and FBF-2 regulate the size of the mitotic region in the C. elegans germline. Dev Cell 7, 697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ariz M, Mainpal R and Subramaniam K (2009). C. elegans RNA-binding proteins PUF-8 and MEX-3 function redundantly to promote germline stem cell mitosis. Dev Biol 326, 295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hansen D, Wilson-Berry L, Dang T and Schedl T (2004). Control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the C. elegans germline through regulation of GLD-1 protein accumulation. Development 131, 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kadyk LC and Kimble J (1998). Genetic regulation of entry into meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 125, 1803–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eckmann CR, Crittenden SL, Suh N and Kimble J (2004). GLD-3 and control of the mitosis/meiosis decision in the germline of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 168, 147–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim KW, Nykamp K, Suh N, Bachorik JL, Wang L and Kimble J (2009). Antagonism between GLD-2 binding partners controls gamete sex. Dev Cell 16, 723–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim KW, Wilson TL and Kimble J (2010). GLD-2/RNP-8 cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase is a broad-spectrum regulator of the oogenesis program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 17445–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Spike CA, Coetzee D, Eichten C, Wang X, Hansen D and Greenstein D (2014). The TRIM-NHL protein LIN-41 and the OMA RNA-binding proteins antagonistically control the prophase-to-metaphase transition and growth of Caenorhabditis elegans oocytes. Genetics 198, 1535–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tocchini C, Keusch JJ, Miller SB, Finger S, Gut H, Stadler MB and Ciosk R (2014). The TRIM-NHL protein LIN-41 controls the onset of developmental plasticity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 10, e1004533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tsukamoto T, Gearhart MD, Spike CA, Huelgas-Morales G, Mews M, Boag PR, Beilharz TH and Greenstein D (2017). LIN-41 and OMA Ribonucleoprotein Complexes Mediate a Translational Repression-to-Activation Switch Controlling Oocyte Meiotic Maturation and the Oocyte-to-Embryo Transition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 206, 2007–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Leacock SW and Reinke V (2008). MEG-1 and MEG-2 are embryo-specific P-granule components required for germline development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 178, 295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang JT et al. (2014). Regulation of RNA granule dynamics by phosphorylation of serine-rich, intrinsically disordered proteins in C. elegans. Elife 3, e04591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seydoux G (2018). The P Granules of C. elegans: A Genetic Model for the Study of RNA-Protein Condensates. J Mol Biol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Detwiler MR, Reuben M, Li X, Rogers E and Lin R (2001). Two zinc finger proteins, OMA-1 and OMA-2, are redundantly required for oocyte maturation in C. elegans. Dev Cell 1, 187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Prasad A, Porter DF, Kroll-Conner PL, Mohanty I, Ryan AR, Crittenden SL, Wickens M and Kimble J (2016). The PUF binding landscape in metazoan germ cells. RNA 22, 1026–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mainpal R, Priti A and Subramaniam K (2011). PUF-8 suppresses the somatic transcription factor PAL-1 expression in C. elegans germline stem cells. Dev Biol 360, 195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wright JE, Gaidatzis D, Senften M, Farley BM, Westhof E, Ryder SP and Ciosk R (2011). A quantitative RNA code for mRNA target selection by the germline fate determinant GLD-1. EMBO J 30, 533–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jungkamp AC, Stoeckius M, Mecenas D, Grün D, Mastrobuoni G, Kempa S and Rajewsky N (2011). In vivo and transcriptome-wide identification of RNA binding protein target sites. Mol Cell 44, 828–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Spike CA, Coetzee D, Nishi Y, Guven-Ozkan T, Oldenbroek M, Yamamoto I, Lin R and Greenstein D (2014). Translational control of the oogenic program by components of OMA ribonucleoprotein particles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 198, 1513–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang X, Olson JR, Rasoloson D, Ellenbecker M, Bailey J and Voronina E (2016). Dynein light chain DLC-1 promotes localization and function of the PUF protein FBF-2 in germline progenitor cells. Development 143, 4643–4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].King SM and Patel-King RS (1995). The M(r) = 8,000 and 11,000 outer arm dynein light chains from Chlamydomonas flagella have cytoplasmic homologues. J Biol Chem 270, 11445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilson MJ, Salata MW, Susalka SJ and Pfister KK (2001). Light chains of mammalian cytoplasmic dynein: identification and characterization of a family of LC8 light chains. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 49, 229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rapali P, Szenes Á, Radnai L, Bakos A, Pál G and Nyitray L (2011). DYNLL/LC8: a light chain subunit of the dynein motor complex and beyond. FEBS J 278, 2980–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Epstein E et al. (2000). Dynein light chain binding to a 3’-untranslated sequence mediates parathyroid hormone mRNA association with microtubules. J Clin Invest 105, 505–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rom I, Faicevici A, Almog O and Neuman-Silberberg FS (2007). Drosophila Dynein light chain (DDLC1) binds to gurken mRNA and is required for its localization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773, 1526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brenner S (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Novak P, Wang X, Ellenbecker M, Feilzer S and Voronina E (2015). Splicing Machinery Facilitates Post-Transcriptional Regulation by FBFs and Other RNA-Binding Proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans Germline. G3 (Bethesda) 5, 2051–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Voronina E, Paix A and Seydoux G (2012). The P granule component PGL-1 promotes the localization and silencing activity of the PUF protein FBF-2 in germline stem cells. Development 139, 3732–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Krueger F (2015) Trim Galore!: A wrapper tool around Cutadapt and FastQC to consistently apply quality and adapter trimming to FastQ filesed.^eds)

- [39].Langmead B and Salzberg SL (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dobin A et al. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Love MI, Huber W and Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bailey TL (2011). DREME: motif discovery in transcription factor ChIP-seq data. Bioinformatics 27, 1653–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Grant CE, Bailey TL and Noble WS (2011). FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27, 1017–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dorsett M and Schedl T (2009). A role for dynein in the inhibition of germ cell proliferative fate. Mol Cell Biol 29, 6128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kershner AM, Shin H, Hansen TJ and Kimble J (2014). Discovery of two GLP-1/Notch target genes that account for the role of GLP-1/Notch signaling in stem cell maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 3739–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Morthorst TH and Olsen A (2013). Cell-nonautonomous inhibition of radiation-induced apoptosis by dynein light chain 1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Dis 4, e799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Noble DC, Aoki ST, Ortiz MA, Kim KW, Verheyden JM and Kimble J (2016). Genomic Analyses of Sperm Fate Regulator Targets Reveal a Common Set of Oogenic mRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 202, 221–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ortiz MA, Noble D, Sorokin EP and Kimble J (2014). A new dataset of spermatogenic vs. oogenic transcriptomes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 4, 1765–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Angeles-Albores D, N Lee RY, Chan J and Sternberg PW (2016). Tissue enrichment analysis for C. elegans genomics. BMC Bioinformatics 17, 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sharifnia P and Jin Y (2014). Regulatory roles of RNA binding proteins in the nervous system of C. elegans. Front Mol Neurosci 7, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kiltschewskij D and Cairns M (2017) Post-Transcriptional Mechanisms of Neuronal Translational Control in Synaptic Plasticity, InTech [Google Scholar]

- [52].Antonacci S et al. (2015). Conserved RNA-binding proteins required for dendrite morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons. G3 (Bethesda) 5, 639–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bernstein D, Hook B, Hajarnavis A, Opperman L and Wickens M (2005). Binding specificity and mRNA targets of a C. elegans PUF protein, FBF-1. RNA 11, 447–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kaymak E and Ryder SP (2013). RNA recognition by the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte maturation determinant OMA-1. J Biol Chem 288, 30463–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li W, Yi P and Ou G (2015). Somatic CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations reveal roles of embryonically essential dynein chains in Caenorhabditis elegans cilia. J Cell Biol 208, 683–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Clark S et al. (2018). Multivalency regulates activity in an intrinsically disordered transcription factor. Elife 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lin R (2003). A gain-of-function mutation in oma-1, a C. elegans gene required for oocyte maturation, results in delayed degradation of maternal proteins and embryonic lethality. Dev Biol 258, 226–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Smith J, Calidas D, Schmidt H, Lu T, Rasoloson D and Seydoux G (2016). Spatial patterning of P granules by RNA-induced phase separation of the intrinsically-disordered protein MEG-3. Elife 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.