Abstract

Friedel-Craft acylation at 100 °C of 2,5,9,9-tetramethyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-benzocycloheptene [ar-himachalene (1)], a sesquiterpenic hydrocarbon obtained by catalytic dehydrogenation of α-, β- and γ-himachalenes, produces a mixture of two compounds: (3,5,5,9-tetramethyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-benzocyclohepten-2-yl)-ethanone (2, in 69% yield), with a conserved reactant backbone, and 3, with a different skeleton, in 21% yield. The crystal structure of 3 reveals it to be 1-(8-ethyl-8-hydroperoxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)-ethanone. In this compound O-H…O bonds form dimers. These hydrogen-bonds, in conjunction with weaker C-H…O interactions, form a more extended supramolecular arrangement in the crystal.

Keywords: ar-himachalene, Friedel-Craft acylation, hydroperoxyde, hydrogen-bonds

1. Introduction

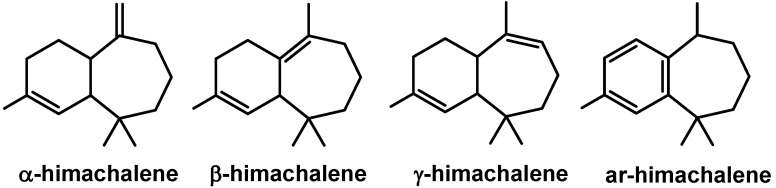

Atlas Cedar (Cedrus atlantica) is the principal species in Moroccan forests. The tree plays a significant role in the socio-economy of Morocco, being good for furniture making. Furthemore, Atlas cedarwood oils are constituents of several products such as drugs, perfumes etc. [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The essential oil is mainly composed of the sesquiterpene hydrocarbons α-himachalene, β-himachalene, and γ-himachalene (Figure 1) which together can make up almost 70% of the composition [7,8] Ar-Himachalene (Figure 1), valued in perfumery [1,7] and the male-produced pheromone component of the flea beetle Aphthona flava [9,10], constitutes only 0.5% of the total oil.

Figure 1.

Main components of cedarwood oil.

Essential oils are an extremely useful source of starting materials for several industrial processes used for the synthesis of fragances and pharmaceutical compounds. A new route to high added value compounds from these cheap natural products is therefore a challenge, among which catalytic functionalization is of major interest. In fact, many different methods for functionalization of this essential oil were developed by our group within the framework of preparing new products having olfatory properties [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Several publications are devoted to the synthesis of new chiral ketone-peroxides, which play an important role in organic synthesis as substrates for the preparation of many classes of compounds such as chiral aromatic alcohols [19] or Schiff base [20] derivatives. As a contribution to this widespread area, we describe herein the synthesis and characterization of a new functionalized peroxide which could be a useful starting material for the preparation of new aromatic musk odorants [21,22].

2. Results and Discussion

In the first step of our procedure, ar-himachalene (1) was prepared in good yield by dehydrogenation of the mixture of α-, β- and γ-himachalene using the previously published method [23]. The reaction, catalyzed with Raney nickel, affords ar-himachalene in 93% yield.

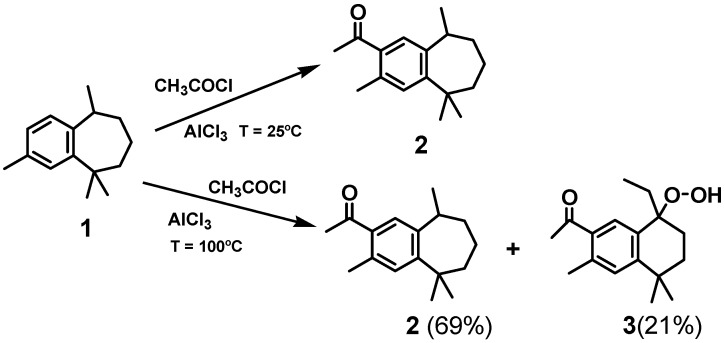

In the second step of the procedure (Scheme 1), Friedel-Craft acylation of ar-himachalene with acetyl chloride at room temperature, using AlCl3 as catalyst, gave 1-(3,5,5,9-tetramethyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-benzocyclohepten-2-yl)-ethanone (2) as single product. When this reaction was carried out at 100 °C, keeping other conditions constant, 2 as major product (69%) and 1-(8-ethyl-8-hydroperoxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-naphthalen-2-yl)-ethanone (3, in 21% yield) were obtained.

Scheme 1.

Friedel-Craft acylation of ar-himachalene.

The spectroscopic data of the two newly prepared products 2 and 3 are consistent with the assigned structures, characterized in 1H-0 and 13C-NMR spectroscopies by the existence of only two CH aromatic signals, which appeared as singlets, at 7.10 ppm and 7.50 ppm for 2 and at 7.09 ppm and 7.71 ppm for 3. The methyl moiety of the acetyl groups appeared at 2.50 ppm and 2.48 ppm for 2 and 3, respectively. The rearrangement of the seven membered ring in compound 3, is shown by the presence of ethyl group signals at 0.85 ppm (CH2CH3, d, J = 7.5 Hz) and 1.85 ppm (CH2CH3, q, J = 7.5 Hz). These assignments are in agreement with the 13C-NMR data. In the 1H-NMR of compound 3 a signal at 2.12 ppm attributable to OOH was found. Its relative sharpness points out the participation of the hydroperoxide group in hydrogen-bonds.

The formation of this new acyl-hydroperoxyde 3 can be explained by the oxyfunctionalization of acyl-ar-himachalene with molecular oxygen when exposed to air, as described by Orfanopoulos et al. [24]. Scheme 2 shows the proposed mechanism. The molecular oxygen [2 + 2] ene reaction of the product A’ (probably formed in situ at 100 °C as a consequence of the basicity of AlCl4−) gives intermediate B’, which was converted to the transition state C’ [24]. Rearrangement of the transition state C’ gives the hydroperoxide 3. We note here that the derivatives of himachalene with seven-membered rings are susceptible to undergo rearrangements. Recently, Gouygou et al. [25,26] have reported the reactivity of epoxides derived from the sesquiterpenic himachalenes in the presence of Lewis or Bronsted acids which catalyze the rearrangement of the ring-opening reactions to give ketones or aldehydes through the formation of carbocations.

Scheme 2.

A possible mechanism for the formation of acyl-hydroperoxide (3).

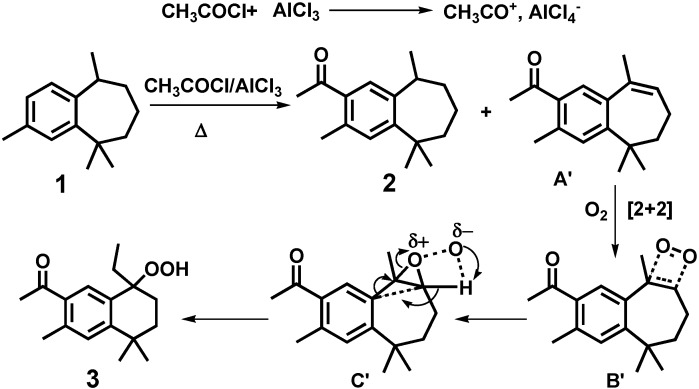

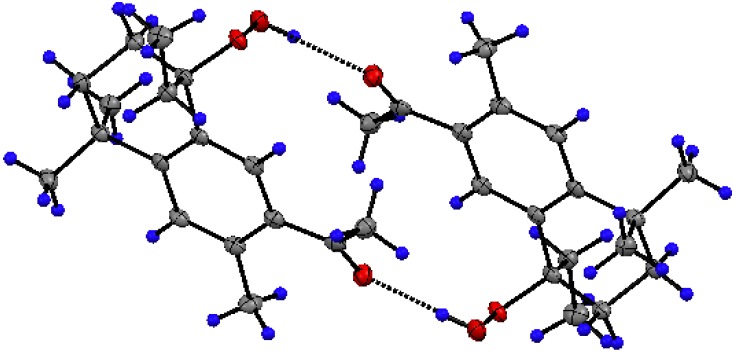

The X-ray single crystal structure analysis permits us to confirm the structure of the rearranged product 3 (Figure 2). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) are given in Table 1.

Figure 2.

ORTEP drawing (50 % thermal ellipsoids) of 3.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 3 (e.s.d.s in parentheses).

| O(1)-O(2) | 1.462(3) | O(1)-C(8)-C(9) | 109.8(2) |

| O(1)-C(8) | 1.452(3) | O(1)-C(8)-C(16) | 102.4(2) |

| O(3)-C(11) | 1.232(3) | O(1)-C(8)-C(7) | 110.2(2) |

| O(2)-O(1)-C(8) | 108.73(19) | O(3)-C(11)-C(1) | 120.8(3) |

The formation from ar-himachalene of a new bicyclic 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene is observed. Although the C(8) asymmetric center has the R-configuration in the molecule shown in Figure 2, the existence of a center of symmetry in space group P21/n corroborates the formation of a racemic mixture. A bond length of 1.462(3) Å has been found for the hydroperoxide, corresponding to a single bond O-O. It compares well with other hydroperoxides [27,28,29,30,31]. Bond lengths and angles around C(8) show its sp3 character. On the other hand, the environment of C(11) in the acyl group shows its usual sp2 geometry. In addition to demonstrating the nature of these functional groups and the new skeleton with two six membered condensed rings instead of ar-himachalene, the crystal structure also reveals the existence of intra- and intermolecular hydrogen-bonds (Table 2). The strongest of these interactions contributes to form dimers (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Hydrogen-Bonds (lengths in Å, angles in °) for 3 (e.s.d.s in parentheses).

| D--H..A | d(D--H) | d(H..A) | d(D....A) | angle (D--H..A) | Symmetry label |

| O(2)--H(2A)..O(3) | 0.8400 | 1.9400 | 2.765(3) | 165.00 | 3_556 |

| C(3)--H(3)..O(1) | 0.9500 | 2.4800 | 3.321(4) | 147.00 | 4_555 |

| C(7)--H(7B)..O(2) | 0.9900 | 2.3700 | 2.806(4) | 106.00 | intramolecular |

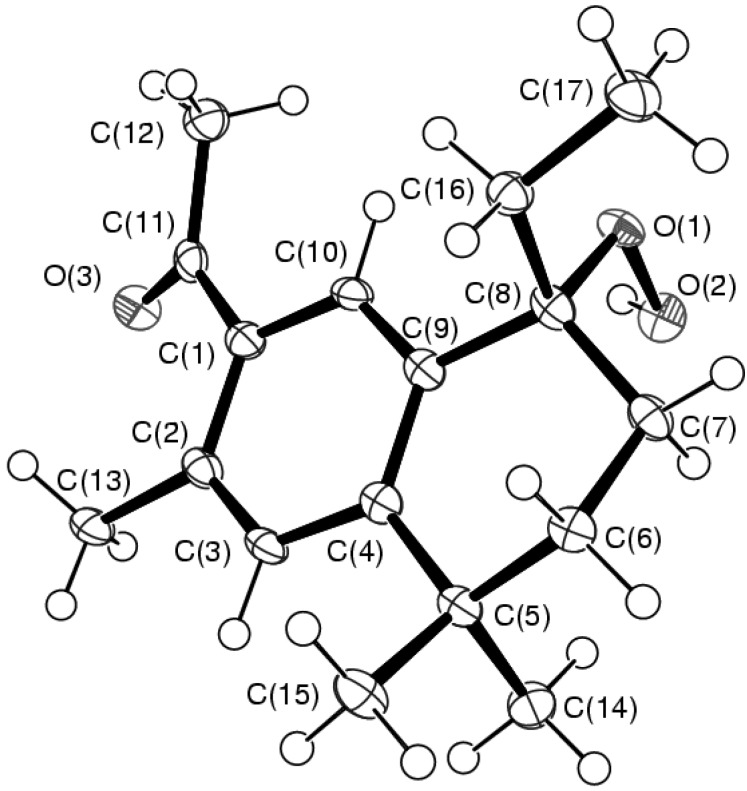

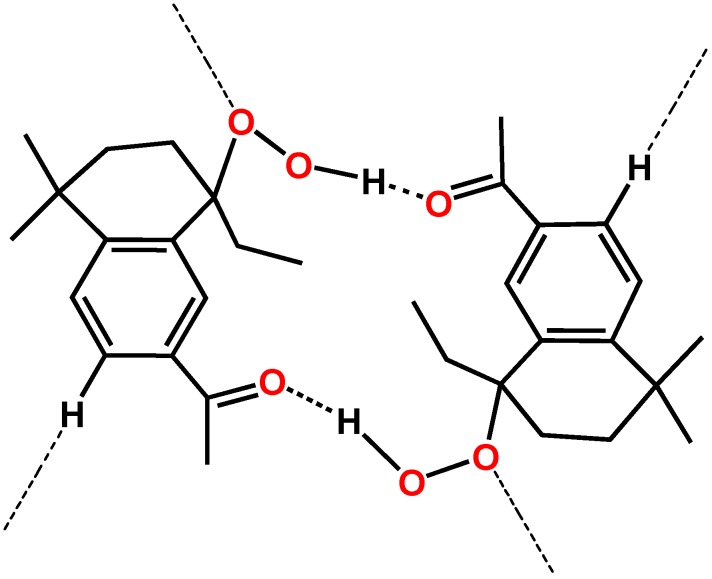

Figure 3.

Molecular dimers formed by two hydrogen-bonds with a total bond length between donor O(2) and acceptor O(3) of 2.765(3) Å.

The association of two molecules is also enhanced by a C(7)--H(7B)..O(2) intramolecular interaction. The dimer adopts an overall conformation in which the rings are oriented parallel to each other.

A second weaker intermolecular hydrogen-bond, C(3)—H…O(1) 3.321(4) Å, is responsible for the interaction between the first one and other dimers forming chains of indefinite length. In this hydrogen-bond the internal hydroperoxide oxygen atom O(1) acts as acceptor. The whole hydrogen-bonded scheme involves most of all potential proton donors and acceptors. An useful way to define a hydrogen-bond pattern is the graph set [32]. In our case, the morphology of hydrogen-bonded array is shown in Figure 4, where the intramolecular hydrogen-bond has been suppressed for clarity.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen-bond patterns.

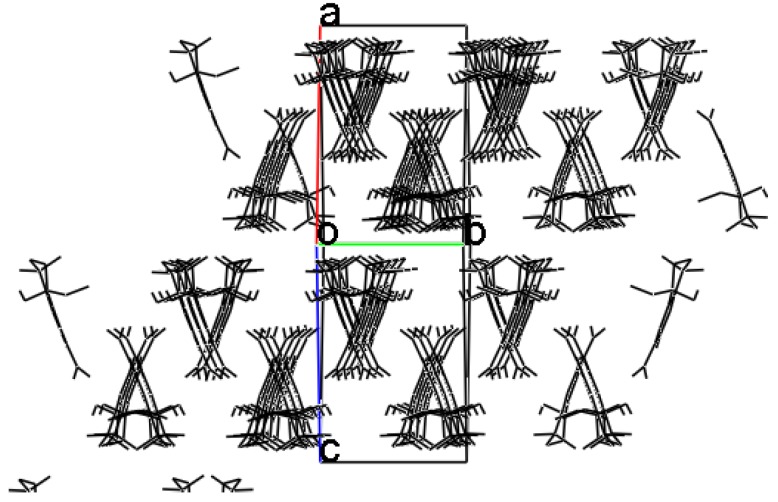

Through this interaction each dimer is bonded to four other bimolecular sets. The global effect of all the described intermolecular interactions is a supramolecular arrangement in columns. These rows form layers aligned to the (−1 0 1) plane (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Layers of molecular rows aligned to the (−1 0 1) plane.

3. Experimental

3.1. General

NMR studies were performed on a Bruker Avance 300 spectrometer in CDCl3, chemicals shifts are given in ppm relative to external TMS and coupling constant (J) in Hz. Liquid chromatography was performed on silica gel (Merk 60, 220-440 mesh; eluent: hexane/ethylacetate). All the reagents and solvents used in the experiments were purchased from commercial sources as received without further purification (Aldrich, Fluka, Acros), and Ar-himachalene were prepared by our team [23].

3.2. General Acylation Procedure:

Acyl chloride (1.56 mmol, 0.122 g) and AlCl3 (1.87 mmol, 0.25 g) were mixed in nitromethane (10 mL), and heated at 100 °C. The aromatic compound (1 mmol) was added to the mixture and the progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. At the end of the reaction, the solvent was evaporated on a rotary evaporator and a saturated solution of NaHSO4 (20 mL) was added. The crude material was extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. Evaporation of the solvent afforded the crude products which were separated by column chromatography using hexane/ethyl acetate (8/2). The products were obtained in yields of 69% for 2 and 21% for isolated 3.

3.3. Acyl-Ar-Himachalene 2:

Pale yellow oil, NMR 1H (CDCl3), δ ppm: 1.24 (3 H, s, CH3), 1.32 (3 H, d, J = 6.9, CH3), 1.36 (3 H, s, CH3), 1.40–1.45 (1 H, m, CHH), 1.54–1.57 (1 H, m, CHH), 1.67–1.74 (4 H, m, CH2), 2.44 (3 H, s, CH3), 2.48 (3 H, s, ArCH3), 3.20 (1 H, m, CHCH3), 7.14 (1 H, s, C4ar-H), 7.49 (1 H, s, C1ar-H); NMR 13C (CDCl3): 19.82, 20.61, 22.73, 27.95, 28.54, 32.67, 33.21, 35.24, 38.61, 39.74, 125.97, 129.57, 133.70, 134.98, 140.03, 150.42, 198.79.

3.4. Acyl-Hydroperoxyde 3:

White solid, 1H-NMR (CDCl3), δ ppm: 0.85 (3 H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH3), 1.20 (3 H, s, C(CH3)2), 1.22 (3 H, s, C(CH3)2), 1.55–1.65 (1 H, m, HCH), 1.71–1.74 (1 H, m, HCH), 1.81 (2 H, q, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH3), 1.87–1.97 (1 H, m, HCH), 2.12 (1 H, s, OOH), 2.25–2.39 (1 H, m, HCH), 2.43 (3 H, s, C3ar-CH3), 2.47 (3 H, s, COCH3), 7.09 (1 H, s, C4ar-H), 7.72 (1 H, s, C1ar-H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 8.62, 21.85, 25.23, 29.31, 31.04, 31.33, 32.19, 34.16, 35.30, 84.65, 128.34, 130.24, 133.70, 134.40, 138.03, 151.28, 199.50.

3.5. X-ray Structure Determination

Single crystals of compound 3 were obtained and mounted on glass fiber to carry out the crystallographic study. Crystal data and experimental details are given in Table 3. X-ray diffraction data collection was measured at 100 K on a Bruker Smart APEX CCD 3-circle diffractometer using a sealed tube source, graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at the Servicio Central de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Universidad de Cádiz. Four sets of frames were recorded over a hemisphere of the reciprocal space by omega scan with δ(ω) 0.30 degrees and exposure of 10 seconds per frame. Correction for absorption was applied by scans of equivalents using program SADABS [33]. An insignificant crystal decay correction was also applied. The structure was solved by direct methods, completed by subsequent difference Fourier syntheses and refined on F2 by full matrix least-squares procedures using the programs contained in SHELXTL package [34] Non hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. The program ORTEP-3 was used for plotting [35]. Crystallographic data in CIF format for 3 have been deposited at Cambridge Crystallographic Data System with reference CCDC 752508.

Table 3.

Crystal Data and Details of the Structure Determination for Compound 3.

| Formula | C17 H24 O3 |

| Formula Weight | 276.36 |

| Crystal System | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/n (No. 14) |

| a, b, c (Å) | 14.459(9), 8.166(5), 14.459(9) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 115.50(2), 90 |

| V (Å3) | 1540.9(17) |

| Z | 4 |

| d(calc) (g/cm3) | 1.191 |

| µ (MoKα) (mm−1) | 0.080 |

| F(000) | 600 |

| Crystal Size (mm) | 0.27 × 0.54 × 0.56 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Radiation, λ (Å) | MoKα, 0.71073 |

| θ Min-Max (°) | 1.7, 25.0 |

| Dataset (h, k, l ranges) | −17:16; −9:7; −17:17 |

| Tot., Uniq. Data, R(int) | 7525, 2657, 0.188 |

| Observed data [I > 2.0 σ(I)] | 2236 |

| Nref, Npar | 2657, 187 |

| R, wR2, S * | 0.0703, 0.1937, 1.06 |

| Max. and Av. Shift/Error | 0.000, 0.000 |

| Min. and Max. Resd. Dens. (e/A3) | −0.31, 0.31 |

* w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.0755P) 2 + 0.9681P] where P = (Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3

4. Conclusions

Following our studies on the suitable use of natural resources in order to obtain products of high added value, in the present work we have shown that the Friedel-Crafts acylation of ar-himachalene, under mild conditions, at 25 °C, produces (3,5,5,9-tetramethyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-benzocyclohepten-2-yl)-ethanone (2). However, at 100 °C, the Friedel-Crafts reaction leads to a mixture of two compounds: (3,5,5,9-tetramethyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-benzocyclohepten-2-yl)-ethanone (2, 69%), in which the backbone of reactant is conserved, and 1-(8-ethyl-8-hydroperoxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)-ethanone (3, 21%). In the solid state this new hydroperoxy compound forms dimers by hydrogen-bonds. These dimers are grouped in extended pattern by weaker hydrogen-bonds.

Acknowledgements

We thank to the SCCYT (Universidad de Cádiz) for X-ray data collection and the Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa de la Junta de Andalucía for financial support.

References

- 1.Adams R.P. Cedar Wood oil–analysis and properties. In: Linskens H.F., Jackson J.F., editors. Modern Methods of Plant Analysis, New Series, Vol. 12, Essential Oils and Waxes. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY, USA: 1991. pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Digrak M., Ilcim A., Hakki A.M. Antimicrobial activities of several parts of Pinus brutia, Juniperus oxycedrus, Abies Cilicia, Cedrus libani and Pinus nigra. Phytother. Res. 1999;13:584–587. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199911)13:7<584::AID-PTR508>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh D., Rao S.M., Tripathi A.K. Cedarwood oil [Cedrus deodara] as a potential insecticidal agent against mosquitoes. Naturwissenschaften. 1984;71:265–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00441340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker G.T. Cedarwood oil. Perfum. Essent. Oil Rec. 1968;59:347–350. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence B.M. Cedarwood oil. Perfum. Flavor. 1980;5:63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori K. Recent results in the synthesis of ecologically important bioregulators. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001;73:601–606. doi: 10.1351/pac200173030601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalchat J.-C., Garry R.-P., Michet A. Essential oil in sawdust of Cedrus atlantica from Morocco. JOER. 1994;6:323–325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balchin L. Relationship between bioactivity and chemical composition of commercial essential oils. Flavour Fragrance J. 1998;13:98–104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199803/04)13:2<98::AID-FFJ705>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartelt R.J., Cossé A.A., Zilkowski B.W., Weisleder D., Momany F.A. Male-specific sesquiterpenes from Phyllotreta and Aphthona flea beetles. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001;27:2397–2423. doi: 10.1023/A:1013667229345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori K. Synthesis of (R)-ar-turmerone and its conversion to (R)-ar-himachalene, a pheromone component of the flea beetle: (R)-ar-himachalene is dextrorotatory in hexane, while levorotatory in chloroform. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Firdoussi L., Benharref A., Allaoud S., Karim A., Castanet Y., Mortreux A., Petit F. Palladium(II)-catalyzed acetoxylation and methoxylation of olefinic terpenes. J. Mol. Catal. 1992;72:L1–L5. doi: 10.1016/0304-5102(92)80037-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Firdoussi L., Baqqa A., Allaoud S., Ait Allal B., Karim A., Castanet Y., Mortreux A. Selective palladium-catalyzed functionalization of limonene: synthetic and mechanistic aspects. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1998;135:11–22. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(97)00285-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ait Allal B., El Firdoussi L., Allaoud S., Karim A., Castanet Y., Mortreux A. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2000;200:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziyat H., El Houssame S., Ait Ali M.Y., Ait Itto M., Karim A., Wartchow R., Butenschon H. Synthesis, structure, and absolute configuration of a new cyclopropanic compound derived from the sesquiterpene β-himachalene. Z. Naturforsch. 2004;59b:1177–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziyat H., Ait Ali M., Karim A., Meliet C., Castanet Y., Mortreux A. Acta Chim. Slov. 2004;51:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziyat H., Ait Itto M.Y., Ait Ali M., Riahi A., Karim A., Daran J.-C. Arkivoc. 2006;xii:152–160. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feddouli A., Ait Itto M.Y., Ait Ali M., Hasnaoui A., Riahi A. Efficient Approach for the synthesis of novel functionalized isoxazolines from limonene. Synth. Commun. 2006;36:3617–3624. doi: 10.1080/00397910600943709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Firdoussi L., Ait Ali M., Karim A., Spannenberg A. Zeitschrift Kristallographie. 2007;NCS 222:195–196. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mévellec V., Mattioda C., Schulz J., Rolland J.P., Roucoux A. Enantioselective hydrogenation of ethyl pyruvate in biphasic liquid–liquid media by reusable surfactant-stabilized aqueous suspensions of platinum nanoparticles. J. Catal. 2004;225:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2004.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao W.T., Zheng Z. Synthesis and characterization of chiral nitrobenzaldehyde-schiff base ligands. Molecules. 2003;8:788–792. doi: 10.3390/81100788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fehr C., Chaptal-Gradoz N.C. Syntheses of the enantiomers of vulcanolide. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2002;85:533–543. doi: 10.1002/1522-2675(200202)85:2<533::AID-HLCA533>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fehr C., Chaptal-Gradoz N., Galindo J. Synthesis of (−)-Vulcanolide by enantioselective protonation. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:853–858. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020215)8:4<853::AID-CHEM853>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abouhamza B., Allaoud S., Karim A. 2,4-Dimethyl-3-phenyl-[2'-methyl-3'-chloro]-7-chloro-8-methyl-1,3-diaza-2,4-diboranaphtalene Tricarbonylchromium Complexes. Molecules. 2001;6:M211. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alberti M.N., Orfanopoulos M. Stereoelectronic and solvent effects on the allylic oxyfunctionalization of alkenes with singlet oxygen. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:10660–10675. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.07.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Haib A., Benharref A., Parrès-Maynadié S., Manoury E., Daran J.-C., Urrutigoïty M., Gouygou M. Molecular rearrangement of epoxide derived from sesquiterpenes by Lewis acid catalysis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:1272–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.04.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Haib A., Benharref A., Parrès-Maynadié S., Manoury E., Urrutigoïty M., Gouygou M. Lewis acid- and Bronsted acid-catalyzed stereoselective rearrangement of epoxides derived from himachalenes: Access to new chiral polycyclic structures. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2011;22:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee K.-H., Nozaki H., McPhail A.T. Structure and stereochemistry of maytensifolin-a, a novel hydroperoxy-nortriterpene from maytenus diversifolia. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:707–710. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perales A., Piozzi F. The X-ray revised stereochemistry of the hydroperoxide of atractyligenin. Z. Kristallogr. 1989;188:255–259. doi: 10.1524/zkri.1989.188.3-4.255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernat V., André-Barrès C., Baltas M., Saffon N., Vial H. Synthesis of antimalarial G-factors endoperoxides: Relevant evidence of the formation of a biradical during the autoxidation step. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:9216–9224. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.07.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griesbeck A.G., Lex J., Saygin K.M., Steinwascher J. Azidohydroperoxidation of pinenes: stereoselectivity pattern and the first X-ray structure of a 2-azidohydroperoxide. Chem. Commun. 2000:2205–2206. doi: 10.1039/B005834N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khrustalev, Antipin N.Yu., Kosnikov A.Yu., Antonovsky V.L. Krystallografiya. Crystallogr. Rep. 2004;49:860. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etter M.C. Encoding and decoding hydrogen-bond patterns of organic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990;23:120–126. doi: 10.1021/ar00172a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheldrick G.M. SADABS. University of Göttingen; Göttingen, Germany: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldrick G.M. SHELXTL, Version 6.10, Crystal Structure Analysis Package. Bruker AXS; Madison, WI, USA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrugia L.J. ORTEP-3 for Windows, Version 1.076. ORTEP-3 for Windows-a version of ORTEP-III with a Graphical User Interface (GUI) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997;30:565. doi: 10.1107/S0021889897003117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]