Abstract

Anger is a central characteristic of negative affect and is relatively stable from infancy onward. Absolute levels of anger typically peak in early childhood and diminish as children become socialized and better able to regulate emotions. From infancy to school-age, however, there are also individual differences in rank-order levels of anger. For example, although decreasing in absolute levels, some children may stay the same and others may increase in rank order relative to their peers. Although change in rank order of anger over time may provide unique insight into children’s social development, little is known concerning variations in developmental patterns of anger from a rank-order perspective and how these patterns are related to children’s behavioral adjustment. The current study (N = 361) used group-based trajectory analysis and identified six distinct patterns of parent-reported child anger by rank across 9 months to 7 years: Low/Stable Rank, Average/Stable Rank, Average/Decreasing Rank, Average/Increasing Rank, High/Decreasing Rank and High/Stable Rank. Most children (65.1%) were in low to average rank groups. However, 28.2% and 6.7% of the children were in Average/Increasing and High/Stable groups, respectively. Children in the High/Stable group showed elevated levels of externalizing and internalizing problems at age 8 compared to children in the Average/Stable, Average/Decreasing and High/Decreasing groups. These findings help to clarify different patterns of anger development across childhood and how they may relate to later problem behaviors.

Keywords: anger development, individual variation, problem behaviors, group-based trajectory analysis

Anger in response to a blocked goal is a common emotion in infants and toddlers. As a primary emotion (Izard, 1991), anger coordinates social, psychological, and physical processes linked to self-defense and overcoming obstacles to obtain goals (Izard & Kobak, 1991; Lemerise & Dodge, 2008). Although anger has an adaptive value, excessive expression of anger may be maladaptive -- the ability to regulate anger is a major achievement for infants and toddlers (Loeber & Hay, 1997). In the current study, we focused on child anger from a temperament perspective and conceptualize it as individual differences in the activation and expression of anger in contexts in which a goal is blocked (Rothbart, 1981; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). This operational definition differentiates child anger reactivity from attentional and behavioral processes that can modulate the expression of anger.

Converging evidence suggests that children who display high levels of anger during early childhood relative to other children are at a greater risk for developing peer problems, poor school functioning, and both externalizing and internalizing problems during childhood and adolescence (Blair, 2002; Lemerise & Dodge, 2008; Rydell, Berlin, & Bohlin, 2003), particularly if high levels relative to peers persist over time (Eisenberg et al., 2009). However, relatively little research has examined individual variation in the development of anger. To better understand the development of anger and associated behavioral outcomes, the current study used a group-based trajectory model to identify patterns of change in rank-order of anger measured by parents’ report from infancy to age 7. We then examined whether distinct patterns of stability and change in anger rankings differentially predicted externalizing and internalizing problems at age 8 years.

Developmental Patterns of Anger during Childhood

Anger in response to blocked goals emerges early in development and can be seen in infants as young as 4 months of age (Izard et al., 1995; Lewis, Ramsay, & Sullivan, 2006). To characterize the normative development of anger throughout childhood, some studies have examined change in mean levels of anger over time and other studies have examined stability of child anger, that is, the extent to which children retain relative rank within a sample over time. Mean levels of expressed anger increase during the first year of life and into toddlerhood (Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, 2010; Goodenough, 1931). As children increase in physical mobility, parents respond with greater control (e.g., limit setting), and, in turn, elicit more anger from children (Roben et al., 2012; Shaw & Bell, 1993). Mean levels of anger decrease after toddlerhood and into middle childhood (Denham, Lehman, & Moser, 1995), presumably as children become better at regulating their emotions and communicating and negotiating goals with parents and peers. However, not all children follow this pattern. Eisenberg’s longitudinal studies suggest that although anger decreases over time for most children, a small group of children continue to demonstrate high levels of anger toward caregivers and peers during middle childhood (Eisenberg et al., 1997), emphasizing the need to study individual variations in developmental patterns of anger.

With regard to rank-order, anger is moderately stable from infancy through middle childhood and beyond (Bornstein et al., 2015; Komsi et al., 2006; Lemery, Goldsmith, Klinnert, & Mrazek, 1999). For example, correlations of anger from infancy to early childhood range from .24 to .68 (Lemery et al., 1999), suggesting moderate stability but also considerable variation in the rank-order of anger from age to age. These findings again imply that individual children may demonstrate different patterns of anger over time.

Most research relevant to individual variations in developmental patterns of anger has focused on anger-related behaviors, particularly aggression (Shaw & Bell, 1993), rather than anger reactivity (e.g., overall anger proneness). Although aggression can be motivated by anger, there is evidence that they are not interchangeable constructs. Aggression may be a strategy to achieve goals but may not be accompanied by, or driven by, anger in children after preschool (Kempes, Matthys, De Vries, & Van Engeland, 2005). Specifically, reactive aggression is often associated with high levels of anger, while proactive aggression is driven by individuals’ goals, often in the absence of evident signs of anger (Hubbard et al., 2002). In addition, anger is typically adaptive and normative in appropriate levels (Razza, Martin, & Brooks-Gunn, 2012), while aggression is more often considered a problem behavior especially when it causes physical harm to others (Campbell, Spieker, Burchinal, & Poe, 2006; Loeber & Hay, 1997). Thus, studies of variations in aggression trajectories do not capture normative patterns of anger development, and may emphasize atypical development.

A few studies have focused on individual variations in developmental patterns of anger. One study found that infants varied both in the initial level of anger and the rate at which they increased from 4 to 16 months (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2010). Another study found three different profiles of anger trajectories between 6 and 12 months of age, ranging from no or little anger over time, to increasing levels, or consistently high levels over time (Brooker et al., 2014). While these studies provide some understanding of individual variations in the early developmental patterns of anger, they are limited to the first two years.

One issue in examining variations in anger trajectories across childhood is the need to use appropriate measures for each developmental stage, specifically since anger is elicited and expressed in different ways at different ages. Different measures may not provide comparable estimates of the level of anger if they have different means and variances. The current study addressed the inherent heterotypic continuity and the resulting measurement issues by examining patterns of variation in the rank-order of levels of anger. We did so by using a family of temperament measures from infancy to middle childhood that are built upon the same underlying model of temperamental anger (Carranza, González-Salinas, & Ato, 2013; Goldsmith & Rothbart, 1991; Rothbart et al., 2001). Examining rank-order allowed us to incorporate developmentally analogous measures across age (Kwon, Janz, Letuchy, Burns, & Levy, 2017) and examine the impact of relative levels and patterns of anger, rather than variations in absolute or mean levels of anger, by using group-based trajectory analysis (D. Nagin, email communication, July 4, 2016).

Behavioral Problems Associated with Patterns of Anger

A second goal of the current study was to assess the developmental implications of different patterns of rank-ordered anger across childhood. The tendency to react with high levels of anger to a blocked goal or provocation, along with poor self-regulation, has been found to increase risk for externalizing problems, peer rejection, and victimization (Cole, Teti, & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Crick & Dodge, 1994; Deater-Deckard, Petrill, & Thompson, 2007). For example, high levels of anger during early childhood predicted externalizing problems during later childhood and into adolescence and young adulthood (Caspi, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 2009; Razza et al., 2012; Rydell et al., 2003). Therefore, children who demonstrate high and stable levels of anger relative to their peers versus the pattern of decreasing anger relative to their peers across childhood may also be more likely to demonstrate externalizing problem.

There is also evidence that children who show more anger during early childhood, compared with other children, are more likely to develop internalizing problems during middle and late childhood (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Kim & Deater‐Deckard, 2011; Lemery, Essex, & Smider, 2002). One explanation is that children high in anger have general problems with emotion regulation that are evident in both externalizing and internalizing domains. Another possibility is that children who are high in anger, relative to their peers, are less likely to make friends and more likely to be rejected and victimized by peers, which may, in turn, increase sadness and anxiety (Razza et al., 2012). However, these studies did not capture individual variations in the context of longitudinal patterns of anger and how such individual variation may be related to later behaviors.

Identifying different patterns of anger across childhood may be a better predictor of child outcomes than single assessments of child anger (Lemery et al., 1999). For example, differentiating children with persistently high anger from those with initially high but decreasing patterns of anger may be especially relevant for understanding the development of adaptive social skills in children, as these skills emerge around the preschool years. Furthermore, the studies discussed above have proceeded from a mean level approach and additional insights could be gained regarding the development of externalizing and internalizing problems by examining patterns of stability and change in rank order of anger over time. The current study aimed to take a first step toward that goal by identifying distinct patterns of rank order of anger in relation to problem behaviors at age 8. Of note, meta-analyses of the temperament literature have found negligible sex differences in anger during childhood (Else-Quest, 2012; Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006), in contrast to the consistent and significant gender differences found for externalizing and internalizing behaviors beginning in middle childhood (Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003; Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005). Thus, in the current study, we have included child sex as a covariate when using developmental patterns of child anger to predict child externalizing and internalizing problems at age 8 but have not estimated sex differences in the models.

Current Study

The current study used data from a sample of 361 adopted children to identify different patterns of anger using group-based trajectory analysis (Nagin, 1999) of rank-ordered parent reports of children’s anger at six ages across 9 months to 7 years. We then examined how these patterns at each age point were related to externalizing and internalizing behaviors at age 8. Based on the previous research on anger and aggression, we expect to find 4 different developmental patterns. Specifically, research on the development of anger using a mean level approach (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2010; Brooker et al., 2014) suggests the following three patterns: High/Stable Rank, Moderate/Increasing Rank and Low/Stable Rank. Children in the High/Stable group would show consistently high levels of anger by rank compared to their peers, regardless of changes in their absolute levels of anger over time. Children in the Moderate/Increasing group would initially show moderate levels of anger by rank, relative to other children, but continue to show increasing rank-order of anger over time compared to peers. Finally, children in the Low/Stable group would show consistently low levels of anger relative in rank to their peers over time. Furthermore, we expected that children in the High/Stable Rank group would show higher absolute levels of externalizing and internalizing problems at age 8 than children in the Low/Stable Rank and Moderate/Increasing Rank groups. We also expected, based on research on patterns of aggression (Campbell et al., 2006; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network [NECCRN], 2004), to identify a High/Decreasing Rank group, as some children may become better regulated relative to their peers with development. We expected that children in this group would initially be ranked as high in anger, but continue to show decreasing rank-order of anger over time relative to their peers.

Methods

Participants

The sample is from the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS) Cohort I, which includes 361 adopted children, their adoptive parents and at least one birth parent (Leve et al., 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from The Pennsylvania State University, for “Genes, Prenatal Drug Exposure, and Postnatal Rearing Environment: An Adoption Study”, IRB number: PRAMS00040044, “The Early Growth and Development Study: Family Process, Genes, and School Entry”, IRB number: PRAMS26790, and “Gene-Environment Interplay and the Development of Psychiatric Symptoms in Children”, IRB number: PRAMS00034837 and all individuals provided written informed consent before participating. Forty-two percent of the children were female and 58% were Caucasian, 21% were multi-racial, 11% were African American, 9% were Latino and 1% were other or unknown ethnicity/not reported. The median age of the child at the adoption placement was 2 days (SD = 13 days). There were 21 (6%) same-sex couples. For parsimony, we refer to all families as “adoptive mother” and “adoptive father” (there were no differences between same sex and mother-father families on study descriptives or bivariate associations). Data from the first seven in-person assessments of the adopted child and adoptive parents were used in this study. Detailed recruitment, assessment, and demographic information is available elsewhere (Leve et al., 2013). This sample is a community sample, which was not selected for risk for elevated anger or problem behaviors.

Measures

Child anger.

Child anger was assessed at 9, 18, and 27 months and 4.5, 6 and 7 years of age using an average of adoptive mothers’ and fathers’ reports on a widely-used and well-validated family of temperament questionnaires designed to provide developmentally appropriate and conceptually equivalent indices of anger. Each parent rated child anger at each age and ratings were averaged across parents (rs = .39 - .59).

At 9 months, child anger was measured with the 20-item Distress to Limitations subscale (α = .85) from the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ: Rothbart, 1981). The IBQ was designed to measure temperament in 3- to 12-month-old infants using a 7-point Likert scale.

At 18 and 27 months, child anger was measured with the 28-item Anger Proneness subscale (α = .87) from the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ: Goldsmith, 1996). The TBAQ is appropriate for use in children from 16 to 32 months of age (Goldsmith, 1996) and is scored on a 7-point Likert scale.

At 4.5, 6 and 7 years, child anger was measured with the 6-item Anger subscale (α = .74 - .76) from the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ: Rothbart et al., 2001). The CBQ was designed to measure child temperament between the age of 3 years and 7 years using a 7-point Likert scale. The Anger subscale in the CBQ is considered to be developmentally and conceptually equivalent to the Distress to Limitations subscale in the IBQ (Rothbart et al., 2001) and the Anger Proneness subscale in the TBAQ (Goldsmith, 1996).

Child externalizing and internalizing behaviors.

Child problem behaviors were measured when children were 8 years of age using an average of adoptive mothers’ and fathers’ reports on the 112-item Child Behavior Checklist 6–18 years (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The Externalizing broadband scale (α = .90) consists of 35 items that assess aggressive and oppositional behaviors. The Internalizing broadband scale (α = .84) consists of 31 items that assess anxious/depressed behaviors, withdrawal, and somatic complaints. Parent rated child externalizing and internalizing behavior ratings were averaged across parents (rs = .36 and .52 for internalizing behaviors and externalizing behaviors, respectively).

Control variables.

Additional control variables were included in the analyses to account for possible confounds if significantly correlated with child anger and problem behavior.

Adoption openness.

Because this study used data from an adoption sample, adoptive parents’ reports of child anger may be influenced by their perceived knowledge of or contact with the birth parents (Ge et al., 2008). Therefore, we included a composite index of birth mothers’ and adoptive parents’ perceived openness at 5– 9 months as a covariate in all analyses.

Child sex.

In this sample, using raw externalizing and internalizing behaviors (not T-scores), we found significant effects of child sex on externalizing behaviors at age 8, but not for internalizing behaviors at age 8. In addition, we did not find significant gender differences in anger at any age (detailed findings available from the author upon request). We therefore included child sex as a covariate in the model when predicting problem behaviors at age 8.

Perinatal risk index.

Perinatal risks have been linked with difficult temperament and problem behaviors in children (Beck & Shaw, 2005; Gutteling et al., 2005). We therefore included total perinatal risks as a covariate using an index derived from birth mother reports and coded medical records based on an adaptation of the McNeil-Sjöström Scale for Obstetric Complications (see Marceau et al., 2016; McNeil, 1995 for more details).

Child externalizing and internalizing behaviors at 18 months.

To rule out the contributions of initial problem behaviors at 18 months before attributing relations between patterns of anger to problem behaviors at 8 years, child externalizing and internalizing behaviors at 18 months were included using adoptive parent reports on the 99-item Child Behavior Checklist 1.5– 5 years (α = .73 - .86) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). Scores were averaged across adoptive mothers and fathers to create an index score for problem behaviors at 18 months (rs = .29 and .35 for internalizing behaviors and externalizing behaviors, respectively).

Attrition Analysis

Some adoptive families declined to participate in the study at a given wave or declined to complete a measure at one or more of the assessments. Of the 361 linked sets of participants, the proportion of missingness is listed below: adoptive mother report of child anger at different ages: 3.6% - 30.9%, adoptive father report of child anger at different ages: 10.5% - 38.7%, adoptive mother report of child problem behaviors at age 8: 36.0%, adoptive father report of child problem behaviors at age 8: 47.4%. Within the current sample, Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) chi-square tests indicated that data were missing completely at random, χ2 (1180) = 1187.87, p = .43.

Group-based trajectory analysis is able to accommodate data across repeated measures in the longitudinal model that are missing at random, thus incorporating all available data at each time of assessment (Nagin, 2005). Standard data imputation approaches (e.g., multiple imputation) were not appropriate in the current analysis for the following reasons: 1) the single population assumption of multiple imputation is incompatible with the assumption of multiple subgroups within the population of group-based trajectory analysis (Colder et al., 2001; Costello, Swendsen, Rose, & Dierker, 2008) and 2) the results provided by group-based trajectory analysis do not generate a typical variance-covariance matrix which is needed to pool the results in multiple imputation.

Data Analysis

Prior to the trajectory analysis, scores were averaged for child anger and problem behaviors across adoptive mothers and fathers to create an index score for child anger at each age and problem behaviors at age 8. If one parent report was missing, the other parent report was used as the index score. Next, the adoption openness and perinatal risk index were regressed out if they were significantly correlated with adoptive parents’ reports of child anger at each age or child problem behaviors at age 8. The standardized residuals from these regressions were saved. Finally, child anger across 9 months to 7 years of age was standardized within age to minimize differences in measurement at different ages. These composite scores were then used as indicators for group-based trajectory analyses.

Data analyses proceeded in two steps. First, semi-parametric group-based trajectory analysis (Jones, Nagin, & Roeder, 2001; Nagin, 1999) was conducted in SAS Proc Traj (Jones et al., 2001) to describe the distinctive clusters of developmental patterns in adoptive parents’ reports of child anger from ages 9 months to 7 years. The model provides the estimated proportion of individuals in each group, the shape of the pattern (linear, quadratic or cubic) of each group, and “posterior probability” of the membership of each group for each child in the sample. According to Nagin (2005), an average posterior probability of membership greater than 0.70 for each group indicates satisfactory model fit. Censored normal models were estimated. The time metric used in the current analysis was child age in years (e.g., 0.75, 1.50, 2.25, 4.5, 6, and 7 years). In the current study, we examined models with 2 to 7 groups and selected the optimal model based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), where a higher BIC value indicates better relative fit (Nagin & Tremblay, 1999). The BIC rewards parsimony and favors the more parsimonious model with fewer groups (Kass & Raftery, 1995; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999).

After ascertaining the optimal trajectory model, the next set of analyses was designed to investigate how developmental patterns (groups) of child anger predicted externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors at age of 8. Each child was classified to the group with the largest posterior probability, which best described the developmental patterns of his/her anger profile. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVAs) were then examined using the univariate general linear models with n-level group factor as the main predictor and child externalizing or internalizing behaviors at age 8 as dependent variables. Gender and initial problem behaviors (e.g., child externalizing or internalizing problems at 18 months) were included as covariates in the analysis. Group differences on externalizing and internalizing behaviors were determined by conducting least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparison test with Bonferroni Correction.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The means, standard deviations, minimums and maximums for child anger (raw score) at each assessment, and externalizing behaviors and internalizing behaviors (raw score) at age 8, are provided in Table 1. Bivariate Pearson correlations of the level of anger over time and externalizing and internalizing behaviors are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Anger | ||||

| 9 months (N=351) | 3.13 | .67 | 1.13 | 5.24 |

| 18 months (N=341) | 3.36 | .59 | 1.77 | 4.99 |

| 27 months (N=318) | 3.55 | .59 | 2.07 | 5.61 |

| 4.5 years (N=302) | 4.21 | .89 | 1.75 | 6.67 |

| 6 years (N=309) | 3.99 | .92 | 1.50 | 6.33 |

| 7 years (N=300) | 3.97 | .91 | 1.58 | 6.58 |

| Child Externalizing Behavior | ||||

| 8 years (N=247) | 5.27 | 4.69 | 0 | 26.00 |

| Child Internalizing Behavior | ||||

| 8 years (N=247) | 7.16 | 5.92 | 0 | 32.50 |

Note. SD = Standard Deviation, Min = Minimum, Max = Maximum.

Table 2.

Bivariate Pearson Correlations between Anger at 9, 18, 27 Months and 4.5, 6 and 7 Years and Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors at 8 Years

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anger (9 mo.) | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Anger (18 mo.) | .48*** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Anger (27 mo.) | .46*** | .68*** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Anger (4.5 yrs) | .25*** | .39*** | .43*** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Anger (6 yrs) | .25*** | .36*** | .37*** | .71*** | 1 | |||

| 6. Anger (7 yrs) | .19** | .27*** | .34*** | .66*** | 75*** | 1 | ||

| 7. Externalizing Behaviors (8 yrs) | .07 | .14* | .15* | .35*** | .47*** | .47*** | 1 | |

| 8. Internalizing Behaviors (8 yrs) | .06 | .18** | .11 | .23** | .34*** | .33*** | .64*** | 1 |

Note.

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05.

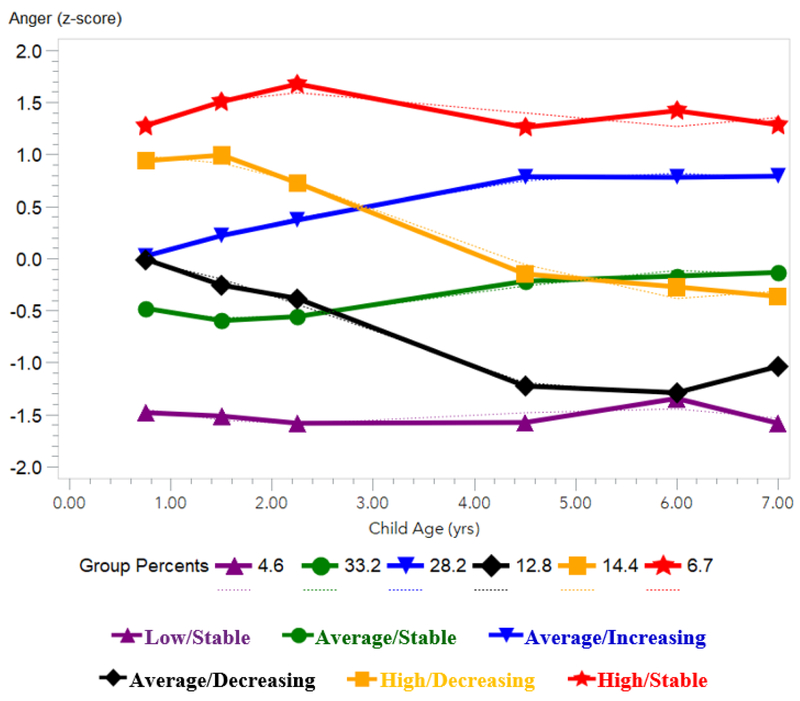

Identification of Developmental Patterns

Table 3 reports the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) scores for trajectory models with two to seven groups. The BIC score increases from the two-group model to the six-group model and decreases afterwards. As mentioned above, a larger BIC indicates better relative fit, and thus a six-group model fit the data better than other models based on BIC score maximization. However, the difference in BIC between the six-group and seven-group models was small. Because of the small proportion of the first group (2.7%) in the seven-group model and in the interest of parsimony, a six-group model (Figure 1) was selected as the optimal model for follow-up analyses. For the six-group model, the average posterior probability of membership for each group is well above the 0.70 threshold, ranging from 0.77 to .86, indicating satisfactory model fit. More information about the numeric characteristics of the six-group model and the syntax file are available from the author upon request.

Table 3.

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) by Number of Groups

| Model | BIC Score |

|---|---|

| Group 2 | −2560 |

| Group 3 | −2525 |

| Group 4 | −2492 |

| Group 5 | −2473 |

| Group 6 | −2469 |

| Group 7 | −2471 |

Note. A larger BIC score suggests a better model fit.

Figure 1.

Developmental Patterns of Anger from Infancy to Middle Childhood.

We examined increases or decreases in anger in the context of rank-order, rather than mean level, based on our initial grouping analyses. As shown in Figure 1, the first, second, and third developmental patterns showed relatively low and average rank-order of anger over time. Children in 1 Group (4.6% of the sample, N = 17; Low/Stable) ranked lower in anger, relative to peers, and their rank order remained stable over time. Children in 2 Groups (33.2% of the sample, N = 120; Average/Stable) ranked low to average in anger, relative to peers, and their rank order remained stable over time. Children in 3 Groups (12.8% of the sample, N = 46; Average/Decreasing) ranked at average levels at 9 months, with a sharp decrease in rank order between 27 months and 4.5 years old. Children in 4 Groups (28.2% of the sample, N = 102; Average/Increasing) ranked at average levels of anger at 9 months of age, with an increase so that by 7 years of age they ranked higher in anger than other children. Children in 5 Groups (14.4% of the sample, N = 52; High/Decreasing) were ranked one standard deviation above the mean in levels of anger, then rank order decreased sharply to average from 18 months to 4.5 years old, and their rank order remained stable after 4.5 years. Finally, children in 6 Groups (6.7% of the sample, N = 24; High/Stable) were initially ranked as relatively high in anger and their rank order remained high, relative to peers, over time, despite slight fluctuations (a slight decrease during toddlerhood, a slight increase during preschool, a decrease at age 7), with higher rank order compared to other groups at each assessment.

Developmental Patterns of Anger Predicting Age 8 Child Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors

The mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of parent-reported child externalizing and internalizing behaviors at age 8 for each group are presented in Table 4. Group comparisons for mean levels of internalizing behaviors at age 8 were significant, F(7, 230) = 6.26, p < .01. Child initial internalizing broadband scores at 18 months were positively associated with internalizing scores at 8 years, F(1, 230) = 17.57, p < .01. Gender was not a significant predictor of age 8 internalizing scores, F(1, 230) = .04, p = .84. Furthermore, patterns (rank order trajectory groups) of child anger were associated with child internalizing scores at age 8, F(5, 230) = 3.08, p = .01. Post-hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction indicated that children in the High/Stable group had significantly higher levels of internalizing problems than children in the Average/Stable, the High/Decreasing, and the Average/Decreasing groups. There were no significant group differences among other groups.

Table 4.

Parent-Reported Child Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors (Mean, Standard Error and 95% Confidence Interval) at Age 8 by Group

| Group | Internalizing Behaviors | Externalizing Behaviors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | 95% CI | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Low/Stable | 4.43 (1.34)a,b | [1.79, 7.07] | 6.70 (1.59)a,b,c | [3.56, 9.84] |

| Average/Stable | 4.59 (0.47)a | [3.66, 5.52] | 6.85 (0.55)a,b | [5.77, 7.94] |

| Average/Increasing | 6.02 (0.55)a,b | [4.93, 7.12] | 8.42 (0.65)b,c | [7.15, 9.70] |

| Average/Decreasing | 4.80 (0.81)a | [3.20, 6.41] | 4.97 (0.95)a | [3.10, 6.83] |

| High/Decreasing | 4.62 (0.75)a | [3.13, 6.11] | 4.71 (0.88)a | [2.98, 6.44] |

| High/Stable | 8.96 (1.15)b | [6.71, 11.22] | 12.57 (1.35)c | [9.91, 15.24] |

Note. 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval. SE = Standard Error. Values with different superscripts within Internalizing and within Externalizing columns differ significantly.

Similar to internalizing behaviors, results for externalizing behaviors at age 8 were also significant, F(7, 230) = 13.16, p < .01. Child initial externalizing broadband scores at 18 months were positively related to externalizing scores at 8 years, F(1, 230) = 28. 52, p < .01. Patterns (rank order trajectory groups) of child anger were also associated with child externalizing behaviors, F(5, 230) = 6.62, p < .01, such that children in the High/Stable group had significantly higher levels of externalizing behaviors than children in the Average/Stable, the High/Decreasing and the Average/Decreasing groups. In addition, children in the Average/Increasing group showed significantly higher levels of externalizing behaviors than children in the Average/Decreasing and the High/Decreasing groups, but not children in other groups. There were no differences between the Low/Stable, the Average/Stable, the Average/Decreasing and the High/Decreasing groups. Additionally, child gender was associated with externalizing behaviors, with boys (M = 7.88) showing higher levels of externalizing behaviors compared to girls at age 8 (M = 6.32), F(1, 230) = 4.27, p = .04.

Secondary Analysis

For child externalizing and internalizing behaviors at age 8, there were 31.6% missing data. To examine whether children with outcome data at age 8 were over-represented in certain trajectory groups, we compared trajectory group frequencies for children with outcome data and children without outcome data using configural frequency analysis (CFA). Trajectory group frequencies did not differ for children with outcome data and children without outcome data, χ2 (5) = 2.71, p = .75, suggesting that children with outcome data were not over-represented in certain trajectory groups and the current findings are not biased because of the missing data at age 8.

Discussion

The current study is one of the first studies to examine individual variation in patterns of child anger from infancy to middle childhood. With multiple assessments of child temperamental anger over time, this study allowed a fine-grained description of distinct patterns, capturing stability and change in children’s rank order of parent-reported anger from infancy to middle childhood.

Although most children were in groups indicating that they maintained low to average levels of anger across time relative to their peers, we identified a small group of children (6.7%, which constituted 24 children in this study) who exhibited chronic high levels of anger over time relative to other children. This finding is consistent with previous research on anger development during infancy (Brooker et al., 2014) and with research on patterns of aggression (Côté, Vaillancourt, LeBlanc, Nagin, & Tremblay, 2006; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network [NECCRN], 2004; Tremblay, 2002). This small group of children were ranked higher in anger than other children in early infancy and over time, which could possibly have been accompanied by aggression as a dysregulated expression of anger at the preschool age (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network [NECCRN], 2004; Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, 2000), consistent with the prediction that this group would show higher levels of externalizing problems at age 8.

Of note, children in the High/Stable group showed significantly higher levels of internalizing problems than other children, consistent with widely reported high levels of co-occurrence in childhood internalizing and externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2001; McConaughy & Skiba, 1993; Roos et al., 2016). One possible explanation for the high co-occurrence of internalizing and externalizing problems in the High/Stable group is that high levels of early anger reactivity could impede the development of effective emotion regulatory skills (Calkins, 1994; Fox & Calkins, 1993). Children who are easily angered may be less likely to use or develop more adaptive and sophisticated regulatory strategies to modulate any kind of negative emotions (e.g., anger, sadness, and fear), thus leading to higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems compared to children who are less easily angered. It is also possible that high levels of externalizing problems indicate a general vulnerability that may place children at risk for later psychopathology, including internalizing problems. These possible mechanisms are likely to function together to explain the association between child anger and later internalizing problems, and require examination in future research.

It should be noted that not all children who ranked high in anger at infancy continued to do so after preschool. Children in the Average/Decreasing and High/Decreasing groups steadily decreased in rank-order of anger from 18 months to 4.5 years, which may reflect their increasing emotion regulation during this period. In contrast to the two decreasing trajectory groups, children in the Average/Increasing group increased in their rank-order of anger after toddlerhood and maintained moderate to high rank-order through middle childhood. This finding is consistent with studies of aggression and broader types of disruptive behaviors following children from early childhood to school age that identified groups of children with increasing levels of aggression over time (Kingston & Prior, 1995; Munson, McMahon, & Spieker, 2001; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). An Average/Increasing group has also been found in studies examining developmental profiles of anger with increases in displays of anger during infancy (Brooker et al., 2014). Note, however, that because of the analytic method used in the current study, children in the Average/Increasing group did not necessarily increase their absolute levels of anger. They may have stayed the same while other children decreased normatively in levels of anger, resulting in their increasing rank-order in levels of anger after toddlerhood.

Many important developmental processes occur during the toddler and preschool periods. As shown in Figure 1, the most clear shifts in patterns of stability and change in children’s rank order of anger occurred between 27 months and 4.5 years, suggesting a sensitive period of anger development and the development of emotion regulation. Taking advantage of multiple assessments of child anger over time, the current study was able to identify this inflection point. Of note, however, is that the apparent shift may be partially due to the need to use different, developmentally appropriate instruments to measure anger at 27 months and 4.5 years.

Although children in the Average/Increasing and High/Stable groups ended up at similar rank order of anger at age 7, the underlying mechanisms for the two groups may be different, as reflected in their different developmental patterns. For example, membership in the High/Stable group may reflect more of a primarily genetic risk for anger and externalizing, whereas the Average/Increasing group may reflect factors in the environment that enhanced a risk for anger proneness that might not otherwise have been expressed (Moffitt, 2005). This highlights the need to examine the correlates of and mechanisms related to the distinct developmental patterns. In particular, a parent-offspring adoption design such as the one used in the current study, where the rearing parents are genetically unrelated to their children, has the ability to examine the ways in which genes and environments work together, helping researchers better understand mechanisms and correlates unique to distinct trajectories. The aim of the current paper was to take the initial step of identifying distinct patterns of stability and change in temperamental anger allowing us to build on this foundation in subsequent research.

Identifying factors associated with an increase or a decrease in rank-order of level of anger remains an important aim for future research. Specifically, it is particularly important to directly examine risk factors (e.g., birth parents’ high levels of anger reactivity and adoptive parents’ over-reactive parenting) associated with the increase in the rank-order level of anger for children in the Average/Increasing group and protective factors (e.g., adoptive parents’ warm and sensitive parenting) associated with the decrease in the level of anger for children in the Decreasing groups.

Limitations, Conclusions, and Directions for Future Research

First, in conducting this research we made a theoretical distinction between anger and aggression. We acknowledge limitations in being able to clearly make such a distinction due to both conceptual and methodological overlap in measures of anger reactivity (Roberton, Daffern, & Bucks, 2015; Roseman, Wiest, & Swartz, 1994). As mentioned in the introduction, anger may include aggressive behaviors but anger or aggression can occur in the absence of the other (Averill, 1983; Roberton et al., 2015). Consistent with this, anger, assessed using temperament measures, showed low to moderate correlations with aggressive behavior, assessed using the CBCL, although both were measured via parent report. Thus, we considered anger as our primary construct, while acknowledging the inherent issues in distinguishing anger and aggression. Second, the sample size was relatively small for the analytic approach, which decreased our confidence in the number of groups. For example, when predicting problem behaviors at age 8, the size of the Low/Stable group is small, leading to large standard errors and thus decreasing the power to detect differences between this group and any other groups. A larger sample size would be preferable for attempting to replicate this study.

Third, the current study used three different (IBQ, TBAQ, CBQ) but equivalent age–related measures of child anger, which made it necessary to examine rank-order rather than absolute increases or decreases in levels of anger across time. However, child anger may manifest differently from infancy to childhood and these measures may not provide exactly the same information about anger. Fourth, the study relied on parent reports of child anger. Because of the developmental periods covered in the study, it was difficult to use informants other than the parents, although mother and father reports were combined to minimize rater effects. Including data from other informants and contexts, such as observational ratings or teacher reports when relevant, could provide additional information about the generalizability of the developmental patterns of anger. Fifth, in predicting outcomes, each child was classified to the group with the largest posterior probability after ascertaining the optimal trajectory model. We acknowledge that this approach ignored the uncertainty in class allocation, which leads to the underestimation of the true effect in terms of predicting later outcomes based on different developmental patterns (groups). Another limitation of the current study is the large percentage (30%) of missing data at older ages.

In summary, our findings reinforce the importance of understanding the mechanisms underlying distinct developmental patterns of anger, particularly the High/Stable and Average/Increasing trajectory groups; in the future, the unique parent-offspring adoption design used in the present study will enable us to examine gene-environment mechanisms in anger development. Furthermore, the current study suggests that the absolute level of anger or change in the anger level is not the only source of information regarding risk. Rather, children’s rank order position relative to peers, even as they all may (or may not) be rising and falling in anger levels, conveys information in and of itself that may be particularly relevant to understanding the development of children’s social and peer relationships.

Acknowledgments

The Early Growth and Development Study was supported by grant R01 HD042608 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), NIH, U.S. PHS (PI Years 1–5: David Reiss, MD; PI Years 6–10: Leslie Leve, PhD), grant R01 DA020585 from NIDA, the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH), the OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Jenae Neiderhiser, PhD), grant R01 MH092118 from NIMH (PIs: Jenae Neiderhiser, PhD and Leslie Leve, PhD), and grant UG3 OD023389 from the Office of the Director, NIH, U.S., PHS (MPIs: Leslie Leve, PhD., Jenae Neiderhiser, Ph.D., & Jody Ganiban, PhD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the birth and adoptive families who participated in this study and the adoption agencies who helped with the recruitment of study participants.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry [Google Scholar]

- Averill JR (1983). Studies on anger and aggression: Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist, 38(11), 1145–1160. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.38.11.1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JE, & Shaw DS (2005). The influence of perinatal complications and environmental adversity on boys’ antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(1), 35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C (2002). Early intervention for low birth weight, preterm infants: The role of negative emotionality in the specification of effects. Development and Psychopathology, 14(02), 311–332. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402002079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Gartstein MA, Hahn CS, Auestad N, & O’Connor DL (2015). Infant Temperament: Stability by Age, Gender, Birth Order, Term Status, and Socioeconomic Status. Child development, 86(3), 844–863. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker JM, Hill-Soderlund AL, & Karrass J (2010). Fear and anger reactivity trajectories from 4 to 16 months: the roles of temperament, regulation, and maternal sensitivity. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 791–804. doi: 10.1037/a0019673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Buss KA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Aksan N, Davidson RJ, & Goldsmith HH (2014). Profiles of observed infant anger predict preschool behavior problems: Moderation by life stress. Developmental Psychology, 50(10), 2343–2352. doi: 10.1037/a0037693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD (1994). Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 53–72. doi: 10.2307/1166138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, & Poe MD (2006). Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(8), 791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carranza JA, González-Salinas C, & Ato E (2013). A longitudinal study of temperament continuity through IBQ, TBAQ and CBQ. Infant Behavior and Development, 36(4), 749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A (2000). The child is father of the man: personality continuities from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 158–172. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Mehta P, Balanda K, Campbell RT, Mayhew K, Stanton WR, . . . Flay BR (2001). Identifying trajectories of adolescent smoking: an application of latent growth mixture modeling. Health Psychology, 20(2), 127–135. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.2.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Teti LO, & Zahn-Waxler C (2003). Mutual emotion regulation and the stability of conduct problems between preschool and early school age. Development and Psychopathology, 15(01), 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello DM, Swendsen J, Rose JS, & Dierker LC (2008). Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 173–183. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Vaillancourt T, LeBlanc JC, Nagin DS, & Tremblay RE (2006). The development of physical aggression from toddlerhood to pre-adolescence: A nation wide longitudinal study of Canadian children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(1), 68–82. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9001-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Petrill SA, & Thompson LA (2007). Anger/frustration, task persistence, and conduct problems in childhood: a behavioral genetic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(1), 80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01653.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Lehman EB, & Moser MH (1995). Continuity and change in emotional components of infant temperament. Child Study Journal, 25(4), 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, . . . Guthrie IK (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72(4), 1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, Guthrie IK, Jones S, . . . Maszk P (1997). Contemporaneous and longitudinal prediction of children’s social functioning from regulation and emotionality. Child Development, 68(4), 642–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04227.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, . . . Losoya SH (2009). Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM (2012). Gender differences in temperament. Handbook of Temperament, 479–496. [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS, Goldsmith HH, & Van Hulle CA (2006). Gender differences in temperament: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, & Calkins S (1993). Pathways to aggression and social withdrawal: Interactions among temperament, attachment, and regulation In Rubin KH & Asendorpf J (Eds.), Social Withdrawal, Inhibition, and Shyness in Childhood (pp. 81–100). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith H (1996). Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development, 67(1), 218–235. doi: 10.2307/1131697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith H, & Rothbart MK (1991). Contemporary instruments for assessing early temperament by questionnaire and in the laboratory Explorations in Temperament (pp. 249–272): Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough FL (1931). Anger in young children. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutteling BM, de Weerth C, Willemsen-Swinkels SH, Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, Visser GH, & Buitelaar JK (2005). The effects of prenatal stress on temperament and problem behavior of 27-month-old toddlers. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 14(1), 41–51. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0435-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE (1991). The psychology of emotions. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Fantauzzo CA, Castle JM, Haynes OM, Rayias MF, & Putnam PH (1995). The ontogeny and significance of infants’ facial expressions in the first 9 months of life. Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 997–1013. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.997 [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, & Kobak RR (1991). Emotions system functioning and emotion regulation In Garber J & Dodge KA (Eds.), The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation (pp. 303–321). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, & Roeder K (2001). A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods & Research, 29(3), 374–393. doi: 10.1177/0049124101029003005 [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, & Raftery AE (1995). Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 773–795. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1995.10476572 [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Lofthouse N, Bates JE, Dodge KA, & Pettit GS (2003). Differential risks of covarying and pure components in mother and teacher reports of externalizing and internalizing behavior across ages 5 to 14. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(3), 267–283. doi: 10.1023/A:1023277413027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempes M, Matthys W, De Vries H, & Van Engeland H (2005). Reactive and proactive aggression in children A review of theory, findings and the relevance for child and adolescent psychiatry. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 14(1), 11–19. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0432-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, & Deater-Deckard K (2011). Dynamic changes in anger, externalizing and internalizing problems: Attention and regulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(2), 156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02301.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston L, & Prior M (1995). The development of patterns of stable, transient, and school-age onset aggressive behavior in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(3), 348–358. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komsi N, Räikkönen K, Pesonen A-K, Heinonen K, Keskivaara P, Järvenpää A-L, & Strandberg TE (2006). Continuity of temperament from infancy to middle childhood. Infant Behavior and Development, 29(4), 494–508. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S, Janz KF, Letuchy EM, Burns TL, & Levy SM (2017). Association between body mass index percentile trajectories in infancy and adiposity in childhood and early adulthood. Obesity, 25(1), 166–171. doi: 10.1002/oby.21673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA, & Dodge KA (2008). The development of anger and hostile interactions. Handbook of Emotions, 3, 730–741. [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Essex MJ, & Smider NA (2002). Revealing the relation between temperament and behavior problem symptoms by eliminating measurement confounding: Expert ratings and factor analyses. Child Development, 73(3), 867–882. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Goldsmith HH, Klinnert MD, & Mrazek DA (1999). Developmental models of infant and childhood temperament. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 189–204. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, & Pears KC (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(5), 505–520. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6734-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, & Reiss D (2013). The Early Growth and Development Study: a prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(01), 412–423. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Ramsay DS, & Sullivan MW (2006). The relation of ANS and HPA activation to infant anger and sadness response to goal blockage. Developmental Psychobiology, 48(5), 397–405. doi: 10.1002/dev.20151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, & Hay D (1997). Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 371–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, De Araujo-Greecher M, Miller ES, Massey SH, Mayes LC, Ganiban JM, . . . Neiderhiser JM (2016). The perinatal risk index: early risks experienced by domestic adoptees in the United States. PloS One, 11(3), e0150486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConaughy SH, & Skiba RJ (1993). Comorbidity of externalizing and internalizing problems. School Psychology Review, 22(3), 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil T (1995). McNeil-Sjöström scale for obstetric complications Lund University Department of Psychiatry, Malmö University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (2005). The new look of behavioral genetics in developmental psychopathology: gene-environment interplay in antisocial behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 533–554. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson JA, McMahon RJ, & Spieker SJ (2001). Structure and variability in the developmental trajectory of children’s externalizing problems: Impact of infant attachment, maternal depressive symptomatology, and child sex. Development and Psychopathology, 13(02), 277–296. doi: 10.1017/S095457940100205X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D, & Tremblay RE (1999). Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development, 70(5), 1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 4(2), 139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network NECCR (2004). Trajectories of Physical Aggression from Toddlerhood to Middle Childhood: Predictors, Correlates, and Outcomes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 69(4), i–143. doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976X.2004.00312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Smithmyer CM, Ramsden SR, Parker EH, Flanagan KD, Dearing KF, . . . Simons RF (2002). Observational, physiological, and self–report measures of children’s anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child development, 73, 1101–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razza RA, Martin A, & Brooks-Gunn J (2012). Anger and Children’s Socioemotional Development: Can Parenting Elicit a Positive Side to a Negative Emotion? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(5), 845–856. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9545-1 [Google Scholar]

- Roben P, Caroline K, Bass AJ, Moore GA, Murray-Kolb L, Tan PZ, . . . Teti LO (2012). Let me go: The influences of crawling experience and temperament on the development of anger expression. Infancy, 17(5), 558–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberton T, Daffern M, & Bucks RS (2015). Beyond anger control: Difficulty attending to emotions also predicts aggression in offenders. Psychology of Violence, 5(1), 74–83. doi: 10.1037/a0037214 [Google Scholar]

- Roos LE, Fisher PA, Shaw DS, Kim HK, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, . . . Leve LD (2016). Inherited and environmental influences on a childhood co-occurring symptom phenotype: Evidence from an adoption study. Development and Psychopathology, 28(1), 111–125. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseman IJ, Wiest C, & Swartz TS (1994). Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 206–221. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.206 [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK (1981). Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child development, 569–578. doi: 10.2307/1129176 [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, & Fisher P (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72(5), 1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell A-M, Berlin L, & Bohlin G (2003). Emotionality, emotion regulation, and adaptation among 5-to 8-year-old children. Emotion, 3(1), 30–47. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, & Bell RQ (1993). Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(5), 493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ, & Gilliom M (2000). A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(3), 155–172. doi: 10.1023/A:1009599208790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, & Nagin DS (2003). Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 189–200. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE (2002). Prevention of injury by early socialization of aggressive behavior. Injury Prevention, 8(suppl 4), iv17–iv21. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.suppl_4.iv17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]