Abstract

Although there is little difference in rates of marijuana use between White and Black youth, Blacks have significantly higher rates of marijuana use and disorder in young adulthood. Theory suggests that factors tied to social disadvantage may explain this disparity, and neighborhood setting may be a key exposure. This study sought to identify trajectories of marijuana use in an urban sample during emerging adulthood, neighborhood contexts that predict these trajectories and social role transitions or “turning points” that may re-direct them. Data are from a longitudinal cohort study of 378 primarily Black emerging adults who were first sampled in childhood based on their residence in low-income neighborhoods in Baltimore City and followed-up annually. Group-based trajectory modeling identified three groups: No Use (68.8%), Declining Use (19.6%) and Chronic Use (11.7%). Living in close proximity to an alcohol outlet, and living in a neighborhood with more female-headed households and higher rates of violent crime increased the odds of membership in the Chronic Use group relative to No Use. Living in a neighborhood with more positive social activity increased the odds of membership in the Declining Use group relative to No Use. Not receiving a high school diploma or GED, pregnancy and parenting also increased the odds of membership in the Declining Use group relative to No Use. These findings provide support that minority youth living in socially toxic and disordered neighborhoods are at increased risk of continuing on a trajectory of marijuana use during emerging adulthood while positive social activity in neighborhoods have the potential to redirect these negative trajectories. Besides taking on the responsibilities of parenting, emerging adults in the marijuana user groups had similar educational and family outcomes, suggesting that early marijuana use may have long-term implications.

INTRODUCTION

Minority youth disproportionately reside in low-income, urban neighborhoods (Aneshensel and Sucoff 1996; USDHHS 2001; Wallace and Muroff 2002). The proportion of Blacks in particular, living in high poverty areas exceeded that of all other racial/ethnic groups between 2006 and 2010 (Bishaw 2011). There is a growing body of research linking residence in high poverty neighborhoods to young adult substance use. Much of this research has focused on alcohol and tobacco (e.g. Brenner et al. 2011; Burlew et al. 2009; Buu et al. 2009; Ennett et al. 2010; Tobler et al. 2011). Fewer studies are focused on marijuana. Although there is little difference in marijuana use between White and Black youth, Blacks have significantly higher rates of use and disorder in young adulthood (Kennedy et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2016). Theory suggests that factors tied to social disadvantage may explain this disparity, and neighborhood setting may be a key exposure.

The theoretical basis for the current research draws on Garbarino’s (1995) work which suggests that high-risk behavior may be the by-product of socially toxic environments. Poor employment prospects, violence and poverty characterize these residential neighborhoods, which lack developmental assets for youth and make risky behaviors more likely. In less toxic and more cohesive neighborhoods, residents monitor youth activities, confront individuals “hanging out” on the street, call out disorderly behavior and lobby for neighborhood resources, services and social organizations thereby protecting youth from engaging in risky behaviors (Coleman 1988; Sampson et al. 1997). Absence of social cohesion and collective efficacy within neighborhoods can invite a wide-array of illegal behavior, such as drug selling and use, and incivilities to flourish. Impoverished neighborhoods also often suffer from physical disorder such as abandoned buildings, drug paraphernalia on the streets, vacant lots and graffiti that invite crime and further disorder, and promote helplessness among residents.

A key concept of Gabarino’s perspective is that exposure to social toxins (e.g. neighborhood criminal activity, local drug markets, violence, physical disorder) early in the life course is expected to negatively impact developmental trajectories giving rise to maladaptive coping that persists into young adulthood. In one of the few studies that examines neighborhood and marijuana use, Tarter et al. (2009) found that males living in neighborhoods with a greater proportion of boarded-up structures in childhood were at increased risk of marijuana use in young adulthood. Similarly, in a study of youth in Baltimore, Furr-Holden et al. (2011) found that young adults living in deteriorating neighborhoods (measured by increases in abandoned housing) were more likely to use marijuana two years later. In the same sample, Reboussin et al. (2014, 2015) found neighborhood disadvantage and youth perceptions of disorder were associated with marijuana use during adolescence. Other findings have been inconsistent. For example, Furr-Holden et al. (2015) found a cross-sectional association between neighborhood physical disorder and marijuana use during the year following high school but no association with positive social activity in the neighborhood. In a study of youth in Chicago, no association was found between neighborhood disadvantage and marijuana use (Fagan et al. 2013). In a national study of adolescents, rates of marijuana initiation were greater among adolescents living in neighborhoods with a higher unemployment rate but no relationship was found with youth perceptions of neighborhood safety (Tucker et al. 2013).

Much of the research on neighborhood predictors of marijuana use have focused on the population average at a specific time point or average trends in marijuana use over time. However, there is likely a great deal of heterogeneity in longitudinal patterns of marijuana use during young adulthood that may reflect different etiologic pathways. It may also reflect individual differences in the ability to adapt to a developmental period marked by numerous social role transitions. The life course perspective emphasizes how specific “turning points,” such as high school graduation, college enrollment, employment, marriage, or parenting, can redirect a negative trajectory (Elder 1998). While some transitions may redirect a negative trajectory (e.g. graduation), others may not because of the timing or ordering of the transition (e.g. early parenting or parenting outside of marriage). Group-based trajectory modeling is an alternative approach that can help identify multiple, developmental pathways through which individuals initiate, progress, and desist in their marijuana use (Nagin 1999). There are few studies that have used this approach to examine marijuana trajectories, particularly in urban minority samples. In a sample of 14 to 29 year olds living in East Harlem, Brook et al. (2014) found four trajectory groups: (1) non-users, (2) quitters, (3) moderate users, and (4) increasing chronic users. In a study of Black males in Pittsburgh between the ages of 13 and 24, Finlay et al. (2012) also found four trajectory groups: (1) non-users, (2) adolescent-limited, (3) late onset, and (4) early onset. In another study of Black males between the ages of 7 and 32, Juon et al. (2011) found five trajectory groups: (1) abstainers, (2) adolescent only, (3) early adult decliners, (4) later starters, and (5) persistent users. Findings are generally consistent across studies with most identifying a non-user group, a declining group, and early and late onset groups.

In the present study, we sought to identify trajectories of marijuana use during young adulthood in a sample of primarily low-income Blacks living in Baltimore City. Baltimore is a city with a long history of syndemics of poverty and illicit drug use (Agar & Reisinger 2002; Simon & Burns 1997). It is characteristic of struggling inner-city neighborhoods with violent crime and murder rates among the highest in the nation, and 29% of families living below the poverty level (U.S. Census Bureau 2016). Rates of past year marijuana use among 18-25 year olds are higher than the national average (37.4% vs. 31.7%) but consistent with other urban areas (e.g. 39.5% in New York City) (SAMHSA 2015). Based on the empirical work in urban minority samples, and given our focus on the young adult period, we expected to find four trajectories of marijuana use: a non-user group; a group characterized by increasing marijuana use during young adulthood; a young adult declining group; and a chronic marijuana user group.

We then examined whether aspects of the neighborhood environment where young adults resided at age 18 predicted marijuana trajectories through age 21. Consistent with research linking neighborhood physical disorder to marijuana use (Furr-Holden et al. 2015; Tarter et al. 2009) as well as Garbarino’s notion of socially toxic environments, we hypothesized that living in neighborhoods at age 18 with more physical disorder, alcohol and other drug activity, alcohol outlets, violence and crime would be associated with membership in trajectories characterized by chronic or increasing marijuana use relative to both no use and declining use. Although findings have been inconsistent (Fagan et al. 2013; Reboussin et al. 2014, 2015; Tucker et al. 2013), we hypothesized that higher levels of neighborhood disadvantage would be similarly associated. Finally, we hypothesized that living in a neighborhood at age 18 with positive social activity would not only be associated with no marijuana use but it could redirect a negative trajectory and be associated with declining marijuana use relative to chronic or increasing marijuana use.

Last, we investigated how “turning points” during young adulthood might redirect marijuana trajectories. Consistent with the life-course perspective, we hypothesized that positive life events like high school graduation, receipt of post-secondary education, employment and marriage may redirect a negative trajectory as well as be associated with no marijuana use. Given the young age of our sample, we hypothesized young adults who report being pregnant or getting someone pregnant and young adults who are parenting are more likely to be in the increasing, chronic and declining marijuana user groups. We hypothesize, however that marijuana users that take on the responsibility of parenting following these early pregnancies may be more likely to experience a redirection in their marijuana trajectory and be in the declining use group.

Limited research exists on the epidemiology of marijuana use among low-income, urban Black adolescents and even less on contextual stressors that may be particularly salient for this community (Copeland-Linder et al. 2011). The neighborhood context is especially relevant for this population because they are chronically exposed to poverty, community violence, physical and social disorder and illicit drug activity (including offers to sell drugs) (Aneshensel & Sucoff 1996; Crum et al. 1996; LaVeist & Wallace 2000; USDHHS 2001; Wallace & Muroff 2002). Therefore, it is critical to estimate the impact of various neighborhood characteristics in this urban context on marijuana use in order to identify those that are most related to risky behavior and should be the focus of interventions.

METHODS

Sample

Data were drawn from a community-based longitudinal study conducted by the Baltimore Prevention Intervention Research Center at Johns Hopkins University. The study population consisted of 799 children and families entering 1st grade in nine Baltimore City Public Schools in 1993. The children were recruited for participation in two school-based, preventive, interventions targeting early learning and aggressive and disruptive behavior (Ialongo et al. 1999). Students and teachers were randomly assigned to one of two interventions or control classrooms. The interventions were provided over the 1st grade year. The sample of 799 children was predominantly Black (85%) and 46% were male. The mean age at entrance into first grade was 6.2 years (SD=0.37). About 2/3 of children were receiving free or reduced price meals; a proxy for low socioeconomic status. To qualify for free meals household income had to be at 100% the federal poverty level or below and between 100-185% for reduced price meals.

Approximately 88% of the sample (n=700) were interviewed at least once between 12th grade and age 21 and have data on marijuana use. Participants who were lost to follow-up were more likely to be White (22%) than participants not lost to follow-up (14%). There were no differences with respect to teacher ratings of behavior in first grade, academic achievement, gender or free-lunch status. Of the 700 youth with at least one follow-up assessment, 378 continued to reside in Baltimore City in 12th grade where the environmental assessments were conducted. The current study sample was restricted to these 378 young adults (mean age=17.8 years, SD=0.37 at 12th grade). The sample was 53% male, 95% Black, 61% were receiving free or reduced price meals and 65% were assigned to an intervention condition in 1st grade. The young adults that continued to reside in Baltimore City were more likely to be Black (p<0.001) than those who did not reside in Baltimore City. They were also more likely to have received free or reduced price meals in 12th grade (p<0.01) possibly due to the fact that lower income families do not have the resources to move to more affluent areas outside of Baltimore City. There were no differences in gender or marijuana use in 12th grade between young adults who continued to live in Baltimore City and those who did not, nor differences on self-reports of anxious and depressive symptoms or teacher ratings of aggressive/disruptive behaviors in first grade. Among the 378 youth residing in Baltimore City in 12th grade, 36% moved to a different census tract between 12th grade and the age 21 assessment. However, 70% of those that moved continued to reside in Baltimore City at age 21.

Measures

Marijuana Use between Ages 18 and 21

Data on marijuana use was collected annually using an audio-computer assisted interview to increase accurate reporting of sensitive behavior. Past year frequency of use of marijuana was used in this analysis (0=none, 1=once, 2=twice, 3=3-4 times, 4=5-9 times, 5=10-19 times, 6=20-39 times, 7=40 or more times).

Neighborhood Factors at Age 18

Field Rater Assessments were obtained using the Neighborhood Inventory for Environmental Typology (NIfETy), a reliable and valid instrument developed by Furr-Holden et al. (2008). The NIfETy is a standardized inventory designed to assess characteristics of the environment shown to be related to violence, alcohol, tobacco and other drug activity. Assessments were conducted by two field-raters on the block face of the residence where youth lived during their 12th grade (age 18) interview. Physical Disorder is measured by summing positive responses to the presence of broken windows, abandoned buildings, vacant houses, vacant lots, unmaintained properties, broken bottles, graffiti and vandalism on the block face of the youth’s residence. Similarly, Alcohol and Other Drug Activity is the sum of the presence of drug paraphernalia, presence of specific drug items (e.g. syringes, baggies, vials/vial caps, blunt guts/wrappers, pot roaches, crack pipes, other drug paraphernalia), obvious signs of drug selling, alcohol bottles, broken bottles, people consuming alcohol, and intoxicated people on the block face of the youth’s residence. Positive Social Activity is the sum of youth playing outside, youth sitting in a group, youth in transit, positive adult interactions, adults sitting on steps and adults watching youth on the block.

Distance to the Nearest Alcohol Outlet

Alcohol outlet proximity is a measure of availability and access to alcohol outlets. It has been shown to be related to opportunities to use other drugs, including marijuana (Milam et al. 2013, 2016). It is also related to a number of neighborhood-level factors including neighborhood deprivation (Hay et al. 2009) and violent crime (Day et al. 2012; Furr-Holden et al. 2016). Data on alcohol outlets were obtained from the Board of Liquor License Commissioners for Baltimore City. Data included addresses of all establishments licensed to sell alcohol in Baltimore City in 2005. This investigation focused on off-premise licenses which include package good stores that sell liquor, beer, and wine and seven-day taverns that can sell package goods as studies generally find a stronger relationship between off-premise alcohol outlets and deleterious outcomes (Gruenenwald & Riemer 2006; Yu et al. 2009). The Network Analyst tool in ArcGIS was used to create the shortest route from the participants’ home to the nearest alcohol outlet. The Network Analysts calculates the route based on street networks. Network analysts accounts for walking paths and excludes natural borders and boundaries, such as a large body of water or a highway that people often do not cross in the course of moving through their neighborhood. Data are presented in miles to the nearest outlet.

Narcotic Calls for Service

Visible drug activity was measured using data on emergency and non-emergency narcotic calls for service reported to the Baltimore City Police Department. Narcotic calls for service can reflect a wide range of offenses related to narcotics, including but not limited to the sale and possession of illicit drugs, discarded paraphernalia, and drug-related overdose. Narcotic calls for service have been used to measure drug activity in prior research (Linton et al. 2014; Wooditch et al. 2013). These data were aggregated to neighborhood statistical area (NSA) due to the interpretability of NSAs and relevance to policy. Due to the skewness in this data, narcotic calls for service were dichotomized using a median split.

Violent Crime

Data on violent crimes for 2006 (data not available for 2005) were obtained from the Baltimore City Police Department. The data included the address that the violent crime occurred, the date, and the description of the crime. Violent crimes include rape, aggravated assault, homicide/manslaughter, and robbery. The violent crime data was geocoded at the census tract level and calculated as the number of violent crimes per 100 residents. Due to the skewness in the data, violent crime was dichotomized using a median split.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

Using data from the 2000 Decennial census and youth residences in 2005, we included the percent of families living in poverty and percent female-headed households. Female-headed households is a proxy for single-parent households and has been used in many investigations as a measure of household and neighborhood disadvantage (Chant 2008; Furr-Holden et al. 2016; Ross & Mirowsky 2001). In an analysis of census data, Synder and others found that household poverty is highest among female-headed households with children (Snyder et al. 2006).

Social-Role Transitions between Ages 19 and 21

We examined several social-role transitions occurring between the ages of 19 and 21: (1) graduating high school or receiving a GED, (2) post-secondary education including Junior College towards an Associate Degree, some college towards a Bachelors Degree, vocational/business school or obtaining an Associate Degree (3) working a full-time job for more than a three month period, (4) being married or engaged, (5) being pregnant or getting someone pregnant, and (6) being the primary caregiver for one’s child.

Control Variables

The school district provided information on students’ sex and ethnicity. School records and parent reports indicating each student’s free and reduced-price meal status were collapsed into a dichotomous variable of free or reduced price meals versus self-paid meals at any time during high school as an individual indicator of student socioeconomic status. Intervention status was coded 1 for youth in a 1st grade intervention classroom and 0 otherwise.

Analysis

Group-based trajectory modeling was used to identify patterns of past-year marijuana use frequency from age 18 to 21 (Nagin 1999). Models used a zero-inflated Poisson distribution to account for the large number of youth that did not use marijuana. Linear and quadratic terms for each trajectory group were included and compared. One to five group models were considered. The best model was selected based on a combination of the Bayesian information criteria (BIC), group interpretability, and having reasonably large groups (at least 10% of the sample). Trajectory models were constructed using PROC TRAJ in SAS version 9.4. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate model parameters. Participants were assigned to the marijuana trajectory group with the highest probability of membership.

Multinomial logistic regression models were fit for each neighborhood factor and social role transition factor to explore associations with marijuana trajectory groups adjusting for individual level factors. Less than 8% of the sample was missing data on individual-level covariates. Due to our small sample size we imputed missing data on individual-level covariates for regression modeling. We did not impute variables measured at the neighborhood level. Missing data on covariates for regression modeling was imputed using multiple imputations and a fully conditional specification (Buuren et al. 2006). This method is appropriate for data with arbitrary missing data patterns and both continuous and categorical variables. Twenty imputations were performed using PROC MI and regression analyses were performed using PROC MIANALYZE in SAS Version 9.4.

Results

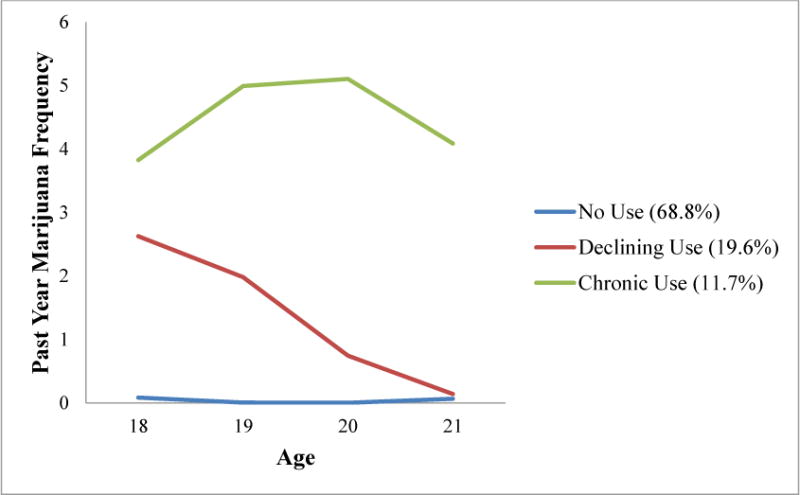

The Bayesian Information Criteria decreased in absolute value with the addition of each trajectory group (1-class=−2278.6, 2-class=−1389.3, 3-class=−1265.2, 4-class=−1214.5, 5-class=−1177.0) but reached an elbow at 4 groups suggesting a three group model was appropriate. The four group model had two groups with small prevalences given the sample size (8% and 9%) and the five class model had group sizes with <5% prevalence. For these reasons, we selected a three group marijuana trajectory model. As shown in Figure 1, the largest trajectory group (group 1; 68.8%) represents participants who do not report using marijuana during emerging adulthood. We refer to this group as the No Use group. The second largest group (group 2; 19.6%) reports using marijuana 3-4 times on average during the past year at age 18 with frequency of use declining to age 21 at which time they report no marijuana use. We refer to this group as Declining Use. The third group (group 3; 11.7%) reports using marijuana on average 5-9 times during the past year at age 18 with frequency increasing to an average of 10-19 times during the past year at ages 19 and 20 and then declining slightly at age 21 back to 5-9 times during the past year. We refer to this group as the Chronic Use group.

Figure 1.

Marijuana Trajectory Groups from Age 18 to 21

In multinomial regression models examining neighborhood factors (Table 1), living in neighborhoods with more positive social activity increased the odds of membership in the Declining Use group (AOR=1.21; 95% CI=1.02, 1.43; p=0.03) relative to No Use. Several factors were associated with membership in the Chronic Use group relative to the No Use group. Living further from an alcohol outlet decreased the odds of membership in the Chronic Use group (AOR=0.13; 95% CI=0.02, 0.78; p=0.03) relative to the No Use group. Living in neighborhoods with more female-headed households (AOR=1.06; 95% CI=1.00, 1.12; 0.04) and violent crime (AOR=1.97; 95% CI=0.99, 3.91; p=0.05) increased the odds of membership in the Chronic Use group relative to the No Use group. In multinomial regression models examining social role transitions (Table 2), obtaining a high school degree or GED was associated with a decreased risk of Declining Use relative to No Use (AOR=0.38; 95% CI=0.20, 0.72; p=01). Alternatively, getting pregnant or getting someone pregnant (AOR=1.95; 95% CI=1.32, 3.35; p=0.02) and parenting (AOR=2.02; 95% CI=1.10, 3.71; p=0.02) were significantly associated with an increased risk of membership in the Declining Use group relative to No Use.

Table 1.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Models for Neighborhood Factors at Age 18 Predicting Marijuana Trajectory Group Membership between Ages 18 and 21

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI), p-value1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Declining Use Vs No Use | Consistent High Use Vs No Use | Declining Use Vs Consistent High Use | |

| Physical Disorder | 1.15 (1.00, 1.32), 0.06 | 1.12 (0.94, 1.34), 0.21 | 1.02 (0.84, 1.25), 0.81 |

| Alcohol & Other Drug Activity | 1.16 (0.96, 1.40), 0.12 | 1.14 (0.90, 1.44), 0.29 | 1.02 (0.78, 1.33), 0.87 |

| Positive Social Activity | 1.21 (1.02, 1.43), 0.03 | 0.94 (0.74, 1.19), 0.61 | 1.29 (0.99, 1.68), 0.06 |

| Distance to Nearest Alcohol Outlet | 0.55 (0.16, 1.91), 0.35 | 0.13 (0.02, 0.78), 0.03 | 4.23 (0.57, 31.6), 0.16 |

| Narcotic Calls for Service | 0.96 (0.55, 1.67), 0.88 | 1.08 (0.53, 2.22), 0.82 | 0.88 (0.38, 2.03), 0.77 |

| Violent Crime | 1.34 (0.78, 2.31), 0.29 | 1.97 (0.99, 3.91), 0.05 | 0.68 (0.31, 1.51), 0.35 |

| % Female-Headed Households | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05), 0.80 | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12), 0.04 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01), 0.11 |

| % Families Living in Poverty | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05), 0.64 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09), 0.08 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.02), 0.26 |

Model adjusts for individual gender, race, intervention group and receipt of free or reduced price meals

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Models for Social Role Transitions Occurring Between Ages 19 and 21 Predicting Marijuana Trajectory Group Membership

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI), p-value1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Declining Use Vs No Use | Consistent High Use Vs No Use | Declining Use Vs Consistent High Use | |

| High School Graduation or GED | 0.38 (0.20, 0.72), 0.01 | 0.48 (0.21, 1.09), 0.08 | 0.79 (0.32, 1.95), 0.61 |

| Post-Secondary Education | 0.66 (0.38, 1.15), 0.15 | 0.58 (0.29, 1.18), 0.14 | 1.13 (0.51, 2.56), 0.75 |

| Employed Full-Time | 1.48 (0.84, 2.61), 0.17 | 1.47 (0.73, 2.98), 0.28 | 1.00 (0.45, 2.25), 0.99 |

| Married or Engaged | 2.17 (0.89, 5.25), 0.09 | 0.93 (0.24, 3.59), 0.92 | 2.33 (0.56, 9.76), 0.25 |

| Pregnancy | 1.95 (1.32, 3.35), 0.02 | 1.84 (0.93, 3.63), 0.08 | 1.06 (0.48, 2.32), 0.89 |

| Parenting | 2.02 (1.10, 3.71), 0.02 | 1.11 (0.48, 2.54), 0.81 | 1.82 (0.72, 4.59), 0.20 |

Model adjusts for individual gender, race, intervention group and receipt of free or reduced price meals

DISCUSSION

We identified three marijuana trajectory groups (No Use, Declining Use and Chronic Use) between the ages of 18 and 21 in a sample of primarily low-income Blacks living in Baltimore City. The Declining Use group had moderate use at age 18 and began to decline at age 19 to no use by age 21. The Chronic Use group started out slightly higher than the Declining Use group, increased slightly at ages 19 and 20 and then returned to the level of use at age 18. Our findings are generally consistent with the few studies of urban minority marijuana use (Brook et al. 2014; Juon et al. 2011; Finlay et al. 2012). There is general overlap between what we label the Declining Use group and the “quitters”, “adolescent only”, and “adolescent limited” groups described in the other studies. Similarly, our Chronic Use group overlaps with the “increasing chronic” and “persistent user” groups found in these studies. Because our trajectories occur during a shorter timeframe we cannot distinguish early and late onset groups. Other variation is likely due to different methods, samples and scales of measurement for marijuana use.

Consistent with work by Furr-Holden et al. (2011, 2015) and Tarter et al. (2009), we found a marginally significant association between objectively measured neighborhood physical disorder and marijuana use. The finding of an association with Declining Use may be reflective of the moderate level of marijuana use in this group at age 18 rather than its declining course between ages 19 and 21. A similar magnitude of association was found with the Chronic Use group but was not significant likely due to the small group size (n=43). These findings are also consistent with studies examining perceived neighborhood disorder (self-report) and adolescent marijuana use (Reboussin et al. 2014, 2015; Wilson et al. 2005). Key resources that support collective efficacy and civic engagement are often lacking in physically disordered neighborhoods which in turn can invite illegal behavior into the neighborhood (Wilson and Kelling 1982).

As noted in Furr-Holden et al. (2015), compared to physical environments, there is much less work examining the neighborhood social environment; a potential proxy for increased neighborhood surveillance and pro-social neighborhood-level norms. We found that living in neighborhoods with more positive activity increased the odds of being in the Declining Use group relative to the No Use group. We had hypothesized that youth living in neighborhoods with more positive social activity would be more likely to be in the No Use group relative to both of the marijuana user groups. One possible explanation for this counterintuitive finding is that the presence of positive social activity in the neighborhood may not matter (e.g. adults watching youth) for a chronic resistor (non-user) whereas for a marijuana user it may have the potential to alter their trajectory. Positive social activity did not distinguish No Use from Chronic Use which provides additional support to the idea that some neighborhood level factors such as social activity may have an effect on reductions in marijuana use but may not influence initiation. Finally, although underpowered, living in a neighborhood with positive social activity was an equally strong predictor of membership in the Declining Use group relative to the Chronic Use group (AOR=1.29; p=0.06) as compared to Declining Use relative to No Use (AOR=1.21; p=0.03). Together these findings support the idea that positive activities (e.g. youth playing outside, adults interacting in a positive manner) including the presence of adults monitoring activities (e.g. sitting on steps, watching youth) may lead to decreases in marijuana use in young adults in urban neighborhoods.

Consistent with research examining exposure to violence as a risk factor for substance use (Copeland-Linder et al. 2011; Doherty et al. 2012; Reboussin et al. 2014, 2015), we found that living in neighborhoods with more violent crime increased the odds of membership in the Chronic Use group relative to No Use. Marijuana may provide a means of coping with the constant feeling of threat and danger that comes with living in a violent neighborhood consistent with the stress reduction hypothesis (Brady & Donenberg 2006; Rosario et al. 2003). Neighborhood disadvantage, as measured by the percentage of female-headed households was also associated with Chronic Use. Neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty are often characterized by high levels of violence and crime that make drugs widely available and weaken beliefs about their potential harms. It can also isolate residents from key resources that support a successful transition to adulthood. Given the high levels of exposure to violence, poverty, and disorder more broadly, it may be important to emphasize the importance of school-based mental health services, so that young people can develop healthy ways to cope with trauma.

Although field-rater assessments of drug and alcohol activity and police reports of narcotic calls for service were not associated with marijuana use, living a greater distance from an alcohol outlet protected against membership in the Chronic Use group. This finding is consistent with Milam et al. (2013) who found that as distance to the nearest outlet increased, risk of marijuana use decreased. Although alcohol outlets reflect increased availability of alcohol, they have also been shown to be related to availability of tobacco and other drugs. McCord and Ratcliffe (2007) demonstrate that alcohol outlets are ideal locations for drug markets because alcohol outlets are more likely to be located in disorganized and high crime communities and attract drug users as many use multiple substances (i.e. tobacco, alcohol). Alcohol outlets represent a potential intervention target that could reduce drug activity in neighborhoods via land use and zoning policies that limit outlet density and restrict outlets from opening in certain zones (e.g. residential areas).

Emerging adulthood brings with it many social role transitions that can redirect a trajectory. We found that not obtaining a high school diploma or GED was significantly associated with Declining Use. It was similarly but marginally associated with Chronic Use. This is consistent with other research findings that marijuana use in adolescence is associated with dropout (Brook et al. 1999; Green et al. 2016; Tice et al. 2017). Pregnancy by the age of 21 was significantly associated with Declining Use and of the same magnitude, but marginally associated with Chronic Use relative to the No Use group. Thus, instead of protecting young adults from continued marijuana use, pregnancy by age 21 could be a result of risky behavior, which has been shown to be related to marijuana use that begins in adolescence (Green et al. 2017). Although pregnancy was associated with marijuana use in general (e.g. differentiated both marijuana trajectories from non-use), being the main caregiver for one’s child (i.e. parenting) was associated only with Declining Use. This suggests that while adolescent marijuana use in 12th grade is associated with early pregnancy, taking responsibility as the caregiver for a child may lead to a decline in marijuana use. Consistent with Kelly & Vuolo (2018) in a nationally representative sample of emerging adults, besides parenting, the Declining Use and Chronic Use groups were similar in regard to most other social role transitions (e.g. lack of high school graduation or GED, post-secondary education, employment, and early pregnancy) suggesting that early marijuana use may have long-term implications.

Limitations of the study should be noted. We relied on a single method (self-report) and reporter (young adult report) to measure drug use. Biological assays of drug use and peer reports of participant drug use would have strengthened this study but were not available. In addition, as is the case with most longitudinal studies, some young adults were lost to follow-up or had moved outside of Baltimore City by their senior year of high school so that objective neighborhood measures were not available. Youth who were lost to follow-up or moved outside of Baltimore City did not differ in their marijuana use in 12th grade or on first-grade behavioral measures such as self-reports of anxious and depressive symptoms or teacher ratings of aggressive/disruptive behaviors. However, this loss to follow-up left us underpowered for several comparisons in which the magnitude of association for the Chronic Use group was similar to the Declining Use group but the finding was only marginally significant (p<0.10).

The greatest strength of this study is the availability of a large sample of minorities participating in a longitudinal study designed to be sensitive to ethnic-minority populations with annual data collection. Although national probability studies have provided critical information on drug use in the U.S. population as a whole, they are less informative in understanding prevalence in subgroups; particularly socioeconomically disadvantaged, ethnic minority populations living in large urban areas. Our ability to more accurately reflect the true nature of minority drug use in the context of the urban neighborhoods where they live and illuminate within group differences makes this a unique contribution to the literature. This is one of the few studies that follows low-income Blacks from childhood to young adulthood and includes extensive measures of individual, family and peer factors as well as an innovative field-rater assessment of the urban neighborhoods where they live.

This study offers insight into marijuana trajectories during the transition to adulthood among primarily low income urban Blacks. Most importantly, our work provides empirical support for the neighborhood social environment as a determinant of marijuana use. These findings suggest that youth living in neighborhoods with crime, alcohol outlets, and poverty at age 18 are more likely to continue on a trajectory of use during emerging adulthood. However, neighborhood interventions that foster collective efficacy through positive social activity have the potential to redirect these negative trajectories of use. Similarities in social role transitions, however, suggest that early marijuana use may have long-term implications.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA032550, DA031738).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: All data collection procedures were carried out with approval from, and in compliance with, the IRB at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Informed Consent: Written parental consent was obtained from parents in accord with the requirements of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Committee on Human Research.

References

- Agar M, Reisinger HS. A heroin epidemic at the intersection of histories: the 1960s epidemic among African Americans in Baltimore. Med Anthropol. 2002;21:115–156. doi: 10.1080/01459740212904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishaw A. Areas with concentrated poverty: 2006-2010 (No. ACSBR/10-17) American Community Survey Briefs 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Donenberg GR. Mechanisms linking violence exposure to health risk behavior in adolescence: Motivation to cope and sensation seeking. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:673–680. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215328.35928.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AB, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Neighborhood variation in adolescent alcohol use: examination of sociological and social disorganization theories. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:651–9. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Balka EB, Whiteman M. The risk for late adolescence of early adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1549–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Finch SJ, Brook DW. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: a relationship with using weapons including guns. Aggress Behav. 2014;40:229–37. doi: 10.1002/ab.21520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, Johnson CS, Flowers AM, Peteer BJ, Griffith-Henry KD, Buchanan ND. Neighborhood risk, parental supervision and the onset of substance use among African American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18:680–689. [Google Scholar]

- Buu A, DiPiazza C, Wang J, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Parent, family and neighborhood effects on the development of child substance use and other psychopathology from preschool to the start of adulthood. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:489–498. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buuren SV, Brand JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Rubin DB. Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 2006;76:1049–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chant S. Dangerous equations? How female-headed households became the poorest of the poor: causes, consequences and cautions. In: Momsen Janet., editor. Gender and Development: Critical Concepts in Development Studies Critical concepts in development, 1 - Th. Routledge; London, UK: 2008. pp. 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:s95–s120. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland-Linder N, Lambert SF, Chen YF, Ialongo NS. Contextual stress and health risk behaviors among African American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40:158–173. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9520-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Lillie-Blanton M, Anthony JC. Neighborhood environment and opportunity to use cocaine and other drugs in late childhood and early adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;43(3):155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day P, Breetzke G, Kingham S, Campbell M. Close proximity to alcohol outlets is associated with increased serious violent crime in New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2012;36(1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty EE, Robertson JA, Green KM, Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME. A longitudinal study of substance use and violent victimization in adulthood among a cohort of urban African Americans. Addiction. 2012;107:339–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty EE, Cwick JM, Green KM, Ensminger ME. Examining the consequences of the “prevalent life events” of arrest and incarceration among an urban African-American cohort. Justice Quarterly. 2016;33:970–999. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2015.1016089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Hipp JR, Cai L. A social contextual analysis of youth cigarette smoking development. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:950–962. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Wright EM, Pinchevsky GM. Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and adolescent substance use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2013;43:69–84. doi: 10.1177/0022042612462218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, White HR, Mun EY, Cronley CC, Lee C. Racial differences in trajectories of heavy drinking and regular marijuana use from ages 13 to 24 among African American and White males. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:118–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CDM, Milam AJ, Nesoff ED, Johnson RM, Fakunle DO, Jennings JM, Thorpe RJ., Jr Not in my back yard: a comparative analysis of crime around publicly funded drug treatment centers, liquor stores, convenience stores, and corner stores in one mid-Atlantic city. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77(1):17–24. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CDM, Lee MH, Milam AJ, Duncan A, Reboussin BA, Leaf PJ, Ialongo NS. Neighborhood environment and marijuana use in urban young adults. Prevention Science. 2015;16:268–278. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0497-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CDM, Lee MH, Milam AJ, Johnson RM, Lee KS, Ialongo NS. The growth of neighborhood disorder and marijuana use among urban adolescents: a case for policy and environmental interventions. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:371–379. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CDM, Pokorni JL, Smart MJ, Ialongo NS, Holder H, Anthony JC. The NIfETy method for environmental assessment of neighborhood-level indicators of violence, alcohol and other drug exposure. Prevention Science. 2008;9:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. Raising children in a socially toxic environment. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Musci RJ, Matson PA, Johnson RM, Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS. Developmental patterns of adolescent marijuana and alcohol use and their joint association with sexual risk behavior and outcomes in young adulthood. J Urban Health. 2017;94:115–24. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Musci RJ, Johnson RM, Matson PA, Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS. Outcomes associated with adolescent marijuana and alcohol use among urban young adults: a prospective study. Addict Behav. 2016;53:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Remer L. Changes in outlet densities affect violence rates. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1184–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay GC, Whigham PA, Kypri K, Langley JD. Neighbourhood deprivation and access to alcohol outlets: a national study. Health & Place. 2009;15(4):1086–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Werthamer L, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Wang S, Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:599–641. doi: 10.1023/A:1022137920532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Fothergill KE, Green KM, Doherty EE, Ensminger ME. Antecedents and consequences of marijuana use trajectories over the life course in an African American population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Vuolo M. Social Science Research. 2018. Trajectories of marijuana use and the transition to adulthood. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SM, Caraballo RS, Rolle IV, Rock VJ. Not just cigarettes: A more comprehensive look and marijuana and tobacco use among African American and White youth and young adults. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2016;18(Suppl 1):S65–72. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TL, Wallace JM. Health risks and the inequitable distribution of liquor stores in African American neighborhoods. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(4):613–7. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Jennings JM, Latkin CA, Gomez MB, Mehta SH. Application of space-time scan statistics to describe geographic and temporal clustering of visible drug activity. J Urban Health. 2014;91:940–56. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9890-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord ES, Ratcliffe JH. A micro-spatial analysis of the demographic and criminogenic environment of drug markets in Philadelphia. Australian & New Zealand. Journal of Criminology. 2007;40:43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Milam AJ, Furr-Holden CD, Harrell P, Ialongo N, Leaf PJ. Off-premise alcohol outlets and substance use in young and emerging adults. Subst Use Misuse. 2013 doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.817426. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam A, Furr-Holden CD, Bradshaw C, Webster D, Cooley-Strickland M, Leaf P. Alcohol environment, perceived safety, and exposure to alcohol, tobacco and other drugs in early adolescence. Journal of Community Psychology. 2016;41:867–883. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Green KM, Milam AJ, Furr-Holden DM, Johnson RM, Ialongo NS. The role of neighborhood in urban black adolescent marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;154:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Green KM, Milam AJ, Furr-Holden CD, Ialongo NS. Neighborhood environment and urban African American marijuana use during high school. Journal of Urban Health. 2014;91:1189–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Ng-Mak DS. Community violence exposure and delinquent behaviors among youth: The moderating role of coping. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(3):258–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D, Burns E. The corner: A year in the life of an inner-city neighborhood. 1st. Broadway Books; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AR, McLaughlin DK, Findeis J. Household composition and poverty among female-headed households with children: Differences by race and residence. Rural Sociology. 2006;71(4):597–624. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2012-2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Substate Age Group Tables. Rockville, MD: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Gavaler JS, Reynolds M, Kirillova G, Clark DB, Wu J, et al. Prospective study of the association between abandoned dwellings and testosterone level on the development of behaviors leading to cannabis use disorder in boys. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice P, Lipari RN, Van Horn SL. The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2017. Substance use among 12th grade aged youths, by dropout status. 2013-2017 Aug 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM. Relationship between neighborhood context, family management practices, and alcohol use among urban, multi-ethnic, young adolescents. Prevention Science. 2009;10:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Pollard MS, de la Haye K, Kennedy DP, Green HD., Jr Neighborhood characteristics and the initiation of marijuana use and binge drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;128:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. State and County Quick Facts. American Community Survey; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race and ethnicity - A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Muroff JR. Preventing substance abuse among African-American children and youth: race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N, Syme SL, Boyce WT, Battistich VA, Selvin S. Adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use: the influence of neighborhood disorder and hope. Am J Health Promot. 2005;20:11–19. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JQ, Kelling GL. The Atlantic, retrieved 2016-05-01. Manhattan Institute; Mar, 1982. Broken Windows: The police and neighborhood safety. [Google Scholar]

- Wooditch A, Lawton B, Taxman FS. The geography of drug abuse epidemiology among probationers in Baltimore. Journal of Drug Issues. 2013;43:231–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Trends in cannabis use disorders among racial/ethnic population groups in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;165:181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Li B, Scribner RA, et al. Hierarchical additive modeling of nonlinear association with spatial correlations—an application to relate alcohol outlet density and neighborhood assault rates. Stat Med. 2009;28:1896–1912. doi: 10.1002/sim.3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]