Abstract

Key points

Periodic breathing and apnoea were more common in preterm compared to age‐matched term‐born infants across the first 6 months after term‐corrected age.

Periodic breathing decreased with age in both term and preterm infants.

Apnoea duration was not different between groups; however, the decline in apnoea index with postnatal age observed in the term infants was not seen in the preterm infants.

Falls in tissue oxygenation index (brain TOI) associated with apnoeas were greater in the preterm infants at all three ages studied.

The clinical significance of falls in brain TOI during periodic breathing and apnoea on neurodevelopmental outcome is unknown and warrants further investigations.

Abstract

Periodic breathing and short apnoeas are common in infants, particularly those born preterm, but are thought to be benign. The aim of our study was to assess the incidence and impact of periodic breathing and apnoea on heart rate, oxygen saturation and brain tissue oxygenation index (TOI) in infants born at term and preterm over the first 6 months after term equivalent age. Nineteen term‐born infants (38–42 weeks gestational age) and 24 preterm infants (born at 27–36 weeks gestational age) were studied at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months post‐term‐corrected age during sleep. Periodic breathing episodes were defined as three or more sequential apnoeas each lasting ≥3 s and apnoeas as ≥3 s in duration. The mean duration of periodic breathing episodes was longer in term infants than in preterm infants at 2–4 weeks (P < 0.05) and at 5–6 months (P < 0.05); however, the nadir in TOI was significantly less in the term infants at 2–3 months (P < 0.001). Apnoea duration was not different between groups; however, the decline in apnoea index with postnatal age observed in the term infants was not seen in the preterm infants. Falls in TOI associated with apnoeas were greater in the preterm infants at all three ages studied. In conclusion, periodic breathing and short apnoeas were more common in infants born preterm and falls in cerebral oxygenation were greater than in the term group. The clinical significance of this on neurodevelopmental outcome is unknown and warrants further investigations.

Keywords: infant, cerebral oxygenation, apnoea

Key points

Periodic breathing and apnoea were more common in preterm compared to age‐matched term‐born infants across the first 6 months after term‐corrected age.

Periodic breathing decreased with age in both term and preterm infants.

Apnoea duration was not different between groups; however, the decline in apnoea index with postnatal age observed in the term infants was not seen in the preterm infants.

Falls in tissue oxygenation index (brain TOI) associated with apnoeas were greater in the preterm infants at all three ages studied.

The clinical significance of falls in brain TOI during periodic breathing and apnoea on neurodevelopmental outcome is unknown and warrants further investigations.

Introduction

Development of respiratory control begins early in gestation and fetal breathing movements are one of the earliest motor behaviours, which are essential for normal antenatal lung growth and development (Carroll & Agarwal, 2010). Even in infants born at term, respiratory control is immature and requires weeks to months to become as stable as in adults. In infants born preterm, the control of the respiratory system is even less mature. This immaturity is frequently manifest as apnoea (Di Fiore et al. 2013). Indeed apnoea of prematurity is one of the most common diagnoses in the neonatal intensive care unit (Eichenwald et al. 2016). Apnoea of prematurity is defined as the cessation of breathing for >20 s or pauses of shorter duration if there is associated bradycardia (<100 beats min−1), cyanosis or marked pallor (NIH, 1986; Eichenwald et al. 2016). Apnoea of prematurity is inversely related to gestational age and is extremely common, occurring in more than 85% of infants born <34 weeks of gestation and in almost all infants born <28 weeks (Henderson‐Smart, 1981). As brief pauses in breathing are often associated with bradycardia or hypoxaemia, most apnoeas are shorter than 20 s (Eichenwald et al. 2016). Apnoea of prematurity is normally resolved by term‐equivalent age, when the reported incidence does not exceed that in term‐born infants (Hunt et al. 2004). Shorter apnoeas, with a lesser degree of bradycardia and hypoxia, can persist well after term‐equivalent age, and we have previously shown that these are associated with clinically significant falls in cerebral oxygenation in infants born preterm (Horne et al. 2017).

Apnoeas can occur in isolation or in a repetitive pattern termed periodic breathing (Kelly & Shannon, 1979). Periodic breathing is defined as three or more sequential apnoeas lasting ≥3 s separated by no more than 20 s of normal breathing (Berry et al. 2012). Because of its high prevalence, and the fact that periodic breathing is not thought to be associated with significant hypoxia or bradycardia, the traditional view of periodic breathing is that it is simply due to immaturity of respiratory control and is benign (Edwards et al. 2013). We have recently shown that periodic breathing in infants born preterm can persist up to 6 months post‐term‐corrected age and is associated with significant bradycardia and falls in cerebral oxygenation (Decima et al. 2015). Studies have shown that excessive or persistent apnoea of prematurity during infancy is associated with poorer long term neurodevelopmental outcomes (Janvier et al. 2004; Pillekamp et al. 2007), which have been suggested to be a result of hypoxic cerebral injury (Martin et al. 2011). Furthermore, low regional cerebral oxygenation levels in preterm infants in the neonatal unit have been associated with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 months of age (Alderliesten et al. 2014).

To date there have been limited longitudinal studies of the incidence of persistent apnoea and periodic breathing in infants born at term (Albani et al. 1985; Wilkinson et al. 2007; Brockmann et al. 2013), and the findings have only been compared to those in preterm infants in a single study (Albani et al. 1985). Furthermore, no study has investigated the physiological effects on heart rate, oxygen saturation or cerebral oxygenation in term infants. In order to provide normative data in term‐born infants to which data from infants born preterm could be compared, this study aimed to contrast the incidence and impact of persistent apnoea and periodic breathing during sleep on heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation (S pO 2) and brain tissue oxygenation index (TOI) over the first 6 months after term‐equivalent age in infants born at term and those born preterm.

Methods

Ethical approval

The studies conformed to the standards set by the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, except for registration in a database, and the procedures were approved by The Monash Medical Centre and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committees. Parents provided written informed consent before their baby's first study.

Polysomnographic recordings

We studied 17 infants born at term and 24 born preterm using daytime polysomnography at the Melbourne Children's Sleep Centre, Monash Medical Centre, longitudinally at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months term‐corrected age. Results of the effects of periodic breathing on cerebral oxygenation and apnoea in the preterm group have been published previously (Decima et al. 2015; Horne et al. 2017).

All electrodes and measuring devices for polysomnography were attached during the infant's morning feed. Infants were then allowed to sleep naturally in a pram in a darkened room at constant temperature. Infants were visually monitored continuously via an infra‐red camera placed above the pram and behavioural changes, such as body movements and crying, were recorded. Infants were placed down to sleep in both the prone and supine positions, with the initial starting position randomised. Sleeping position was changed between morning and afternoon sleep periods that were interrupted by a midday feed. Sleep state was assessed as quiet sleep (QS) or active sleep (AS) using electroencephalographic (EEG), behavioural, heart rate and breathing pattern criteria (Anders et al. 1971; Grigg‐Damberger, 2016).

Polysomnographic recordings included continuous monitoring of EEG (C4/A1; O2/A1), electro‐oculogram, submental electromyogram, electrocardiogram (ECG), thoracic and abdominal breathing movements (Resp‐ez Piezo‐electric sensor, EPM Systems, Midlothian, VA, USA), airflow from the nose and mouth (Breathsensor, Thermal Airflow Sensor, Mortora Instruments Australia, Sydney, NSW, Australia), arterial blood oxygen saturation (S pO 2) with a 2 s averaging time (Masimo Radical Oximeter, Masimo Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) placed on the infant foot, and abdominal skin temperature (ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia). In addition to the standard polysomnographic leads, we also measured cerebral oxygenation using a NIRO‐200 (NIRO‐200 spectrophotometer, Hamamatsu Photonics KK, Tokyo, Japan) with optodes positioned 4 cm apart on the frontal region. Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) depends on the relative transparency of biological tissue to light in the near‐infrared region of the spectrum. NIRS enables the non‐invasive measurement of cerebral tissue oxygenation index (TOI). All physiological data were recorded at a sampling frequency of 512 Hz using a Compumedics E‐Series Sleep Recording system with ProFusion PSG 2 software (Compumedics Limited, Abbortsford, Victoria, Australia). At the completion of the study, data were exported via European Data Format to analysis software (Chart 7.0, ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia).

Data analysis

Apnoeic events were defined as those lasting ≥3 s (Albani et al. 1985). Periodic breathing episodes were defined as three or more sequential apnoeas lasting ≥3 s interrupted by breathing lasting ≤20 s (Kelly & Shannon, 1979). The duration of each apnoea was measured and the duration of each periodic breathing episode was measured from the beginning of the first apnoea until the end of the last apnoea. The frequency of apnoea and periodic breathing was determined for each infant as the total number of episodes recorded. Apnoea index was defined as the number of apnoeas per hour of sleep. Changes in heart rate (HR), peripheral estimate of oxygen saturation (S pO 2) and cerebral oxygenation (TOI) were calculated beat–beat from Chart only during apnoeas and episodes of periodic breathing which were free of movement artifact during the 30 s prior to the episode onset (baseline) and during the entire episode. To allow for the time delay in recording changes in S pO 2 and TOI, nadirs were calculated during the event and up to 15 s after event termination. To account for differences between individual infants, all values were calculated as percentage change from baseline. Due to the cyclical nature of the changes in physiological parameters with the repetitive apnoeas, percentage changes from baseline averaged over each periodic breathing episode masked the actual changes observed. Thus each detected nadir was used to calculate maximal percentage change for each episode (nadir % change) from the baseline. Fractional cerebral tissue oxygen extraction (FTOE) was calculated as (S pO 2 − TOI)/S pO 2. An increase in FTOE reflects an increase of the oxygen extraction by brain tissue, suggesting a higher oxygen consumption in relation to oxygen delivery. Conversely, a decrease in FTOE suggests less utilisation of oxygen by brain tissue in comparison with the supply.

Statistical analysis

Data were first tested for normality and equal variance. The effects of sleep state, sleep position and age on the frequency and duration of periodic breathing and the cardiovascular parameters (baseline and nadir % change in HR, S pO 2 and TOI) were tested with two‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test if required. The relationship between postnatal age and the duration and frequency of periodic breathing episodes and nadir % change in HR, S pO 2 and TOI were tested with one‐way ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc testing if required. Differences between term and preterm infants were tested with Student's t test. Results are expressed as means ± SEM; a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

Term infants (9 male (M)/8 female (F)) were born between 38 and 42 weeks of gestational age (mean 40.1 ± 0.2 weeks, mean ± SEM) with birth weights appropriate for gestational age of between 2900 and 4615 g (mean 3666 ± 102 g). Apgar scores ranged from 7 to 9 (median 9) at 1 min and 9 to 10 (median 9) at 5 min. None of the infants had been exposed to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Infants were studied at 2–4 weeks (mean 3.4 ± 0.1 weeks), 2–3 months (mean 10.7 ± 0.2 weeks) and 5–6 months (mean 22.3 ± 0.3 weeks). Mean total sleep time at 2–4 weeks was 3 h 20 min ± 14 min; at 2–3 months it was 3 h 13 min ± 9 min; and at 5–6 months it was 2 h 53 min ± 11 min.

Preterm infants (13M/11F) were born between 27.3 and 36.2 weeks of gestational age (mean 31.2 ± 0.5 weeks, mean ± SEM) with birth weights of between 925 and 3060 g (mean 1698 ± 112 g). All of the infants were born with appropriate birth weight for gestational age. Apgar scores ranged from 2 to 9 (median 6) at 1 min, and from 4 to 10 (median 9) at 5 min. In the preterm cohort, exclusion criteria included intrauterine growth restriction, major congenital abnormalities, haemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus, significant intraventricular haemorrhage (grade III or IV) and chronic lung disease requiring ongoing respiratory stimulant medication, mechanical respiratory support or oxygen therapy at term‐equivalent age. Thirteen out of 24 had been administered caffeine for apnoea of prematurity during their hospital stay and none were on caffeine or supplemental oxygen at the time of the studies. Infants were studied at 2–4 weeks corrected age (CA) (mean 43 ± 0.1 weeks post‐conceptional age), 2–3 months (mean 51 ± 0.2 weeks post‐conceptional age) and 5–6 months (mean 63 ± 0.3 weeks post‐conceptional age). Mean total sleep time at 2–4 weeks was 3.5 ± 0.1 h; at 2–3 months it was 2.9 ± 0.1 h; and at 5–6 months it was 2.3 ± 2.6 h. There was no difference in total sleep time or sleep time in each sleep state or position between the term and preterm infants at any of the three ages studied.

Periodic breathing episodes

Term infants

The number of individual periodic breathing episodes and apnoeas analysed in each sleep state and sleep position are presented in Table 1. In term infants a total of 95 individual episodes of periodic breathing were detected; 64 at Study 1 at 2–4 weeks (one infant had 35 individual episodes), 24 at Study 2 at 2–3 months and 7 at Study 3 at 5–6 months. Eleven of the 17 infants (59%) exhibited periodic breathing during at least one of the three studies: 10 infants (79%) at 2–4 weeks; 7 (41%) at 2–3 months and 5 (29%) at 5–6 months. Four infants (24%) exhibited epochs of periodic breathing in all three studies and seven infants (41%) at Studies 1 and 2. The amount of time spent in periodic breathing fell with postnatal age: 2.6 ± 1.8% at Study 1, 0.4 ± 0.2% at Study 2 and 0.3 ± 0.2% at Study 3. There were no effects of sleep state or position on baseline or nadir % change in HR or S pO 2 at any age studied. Baseline TOI was higher in AS compared to QS and in the prone compared to supine positions at Study 1; however, these differences were small and not considered of clinical relevance so data were combined for further analysis.

Table 1.

Number and mean duration of episodes of periodic breathing and apnoea at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months in term infants

| AS supine | AS prone | QS supine | QS prone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–4 weeks | ||||

| Number of periodic breathing episodes | 27 | 25 | 3 | 9 |

| Periodic breathing duration (s) | 107 ± 25 | 46 ± 5 | 121 ± 40 | 91 ± 45 |

| Total number of apnoeas analysed | 53 | 88 | 22 | 33 |

| Apnoea duration (s) | 4.4 ± 0.2†† | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 |

| Apnoea index | 2.6 ± 0.6* | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 1.9± 0.7† | 3.1 ± 0.8 |

| 2–3 months | ||||

| Number of periodic breathing episodes | 15 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| Periodic breathing episode duration (s) | 43 ± 5 | 35 ± 5 | 47 ± 10 | — |

| Total number of apnoeas analysed | 33 | 22 | 32 | 29 |

| Apnoea duration (s) | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.2 |

| Apnoea index | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.7 |

| 5–6 months | ||||

| Number of periodic breathing episodes | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Periodic breathing episode duration (s) | 38 ± 8 | 37 ± 6 | 75 ± 39 | — |

| Total number of apnoeas analysed | 10 | 29 | 8 | 2 |

| Apnoea duration (s) | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.8 |

| Apnoea index | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± SEM. * P < 0.05. † P < 0.05, †† P < 0.01, AS vs. QS.

Preterm infants

Data from the preterm group has previously been reported (Decima et al. 2015). Briefly, in the preterm group a total of 261 individual episodes of periodic breathing were detected: 164 at Study 1, 62 at Study 2 and 35 at Study 3.

In the preterm infants 22 of the 24 infants (92%) exhibited periodic breathing during at least one of the three studies: 19 infants (79%) at 2–4 weeks corrected age (CA); 12 (50%) at 2–3 months CA and 10 (42%) at 5–6 months CA. Seven infants (29%) exhibited epochs of periodic breathing at all three studies and 10 infants (42%) at Studies 1 and 2. The two infants who did not exhibit periodic breathing were one female infant born at 27.5 weeks of gestation and one male infant born at 30.2 weeks of gestation.

The frequency and duration of periodic breathing at any of the three studies was not affected by gestational age at birth. The amount of time spent in periodic breathing fell with postnatal age in preterm infants: 6.9 ± 2.4% at Study 1, 3.6 ± 1.8% at Study 2 and 1.3 ± 0.6% at Study 3. There were no effects of sleep state or sleep position on the nadir % change in either HR, S pO 2 or TOI at any of the three ages studied and so data were combined for comparison with term infants.

Comparison between term and preterm infants

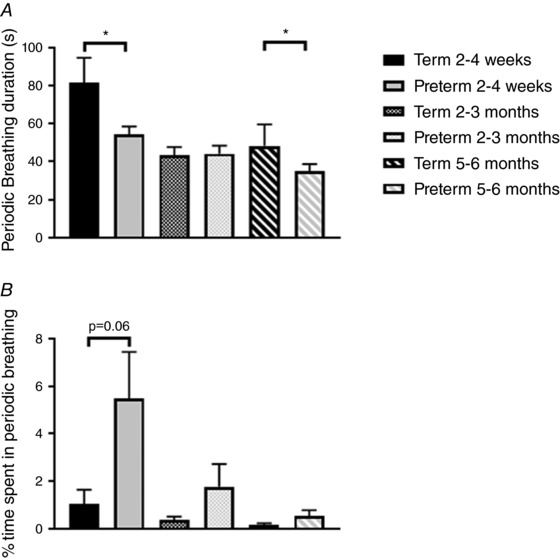

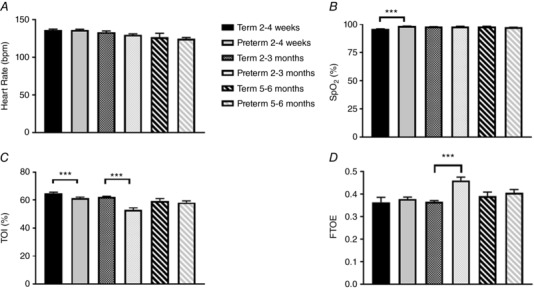

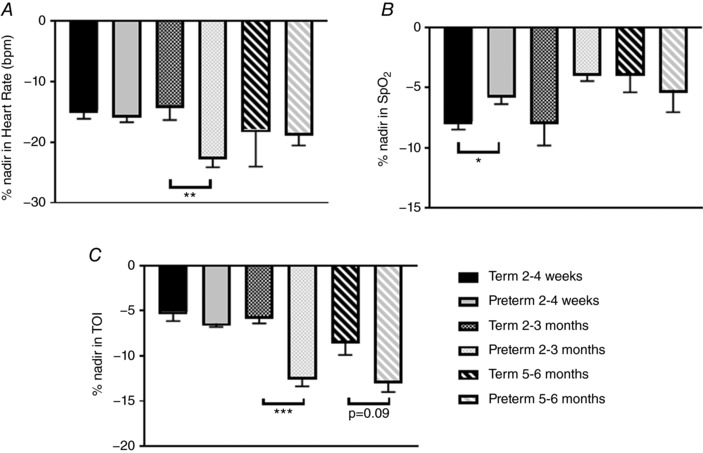

The mean duration of periodic breathing episodes and the time spent in periodic breathing (sleep states and positions combined) are compared between groups in Fig. 1. The mean duration of periodic breathing episodes was longer in term infants at 2–4 weeks (81 ± 13 vs. 54 ± 4 s, P < 0.05) and at 5–6 months (48 ± 11 vs. 31 ± 2 s, P < 0.05, Fig. 1 A). The percentage of sleep time spent in periodic breathing averaged higher in preterm infants (5.5 ± 1.9%) at 2–4 weeks compared to term infants (1.1 ± 0.6%); however, this just failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.06, Fig. 1 B). Baseline values for HR, S pO 2 , TOI and FTOE are compared between term and preterm groups in Fig. 2 (sleep states and positions combined). There were no differences between groups in HR at any of the three ages (Fig. 2 A). Baseline S pO 2 was significantly higher in the preterm group (98.6 ± 0.1%) compared to the term group (96.2 ± 0.2%, P < 0.001) at 2–4 weeks; however, this difference would be unlikely to be of clinical significance (Fig. 2 B). Baseline TOI was significantly lower in the preterm group at both 2–4 weeks and 2–3 months (P < 0.001 for both, Fig. 2 C). Baseline FTOE was not different between groups at 2–4 weeks or 5–6 months; however, it was significantly higher in the preterm infants at 2–3 months (P < 0.001). The maximum % change from baseline (% nadir) for HR, S pO 2 and TOI are compared between term and preterm infants in Fig. 3. The % nadir HR at 2–4 weeks was significantly less in the term group (P < 0.01, Fig. 3 A). The % nadir S pO 2 was significantly greater in the term infants at 2–4 weeks (P < 0.05, Fig. 3 B). The % nadir in TOI was significantly less in the term infants at 2–3 months (−5.6 ± 0.8 vs. −12.3 ± 1.1%, P < 0.001) with a similar trend at 5–6 months (−8.3 ± 1.6 vs. −12.7 ± 1.3%, P = 0.09, Fig. 3 C).

Figure 1. A, comparison of periodic breathing episode duration between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age. * P < 0.05. B, comparison of percentage sleep time spent in periodic breathing episode duration between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age.

Figure 2. Comparison of baseline heart rate (A), peripheral oxygen saturation (B), cerebral oxygenation (C) and fractional tissue oxygen extraction (D) between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age. *** P < 0.001.

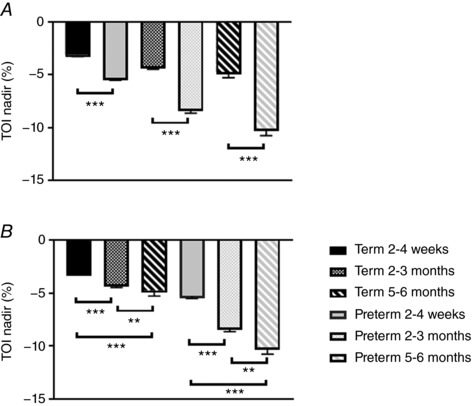

Figure 3. Comparison of percentage change in heart rate (A), peripheral oxygen saturation (B) and cerebral oxygenation (C) during periodic breathing between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Apnoeic events

Term infants

In term infants 16/17 infants at 2–4 weeks, 15/17 infants at 2–3 months and 11/17 infants at 5–6 months exhibited apnoeas. One hundred and ninety‐six apnoeas were analysed at 2–4 weeks, 116 at 2–3 months and 49 at 5–6 months. Infants had between 1 and 29 apnoeas at 2–4 weeks, between 1 and 24 at 2–3 months and between 1 and 15 at 5–6 months, with an average of three per hour at Study 1, two per hour at Study 2 and one per hour at Study 3. Apnoea duration ranged from 3.3 to 11.1 s at 2–4 weeks, 3.1 to 7.2 s at 2–3 months and 3.3 to 8.7 s at 5–6 months.

When data for sleep state and position were combined there was no effect of postnatal age on apnoea duration, HR or S pO 2 nadir. The % nadir in TOI was less at 2–4 weeks than at both 2–3 months and 5–6 months (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Preterm infants

Data for preterm infants have previously been reported (Horne et al. 2017). In brief, all preterm infants exhibited apnoeas at each age studied. Two hundred and fifty‐three apnoeas were recorded at 2–4 weeks, 203 at 2–3 months and 148 at 5–6 months. Infants had between 2 and 27 apnoeas at 2–4 weeks, between 1 and 27 at 2–4 months and between 1 and 16 at 5–6 months, with an average of three per hour at all three studies. Apnoea duration ranged from 3.0 to 15.7 s at 2–4 weeks, 3.1 to 7.3 s at 2–3 months and 3.0 to 8.1 s at 5–6 months. There were no effects of gestational age at birth on total apnoea number analysed, apnoea index or apnoea duration at any study. There was no effect of sleep state or sleep position on nadir HR or nadir S pO 2 at any study. Nadir TOI was statistically significantly lower in QS prone (−7.0 ± 0.7%) compared with QS supine (−4.5 ± 0.4%) at 2–4 weeks; however, this was only ∼2.5% and was not deemed clinically significant. Data were then combined for sleep state and position for comparison with term infants.

Comparison of term and preterm infants

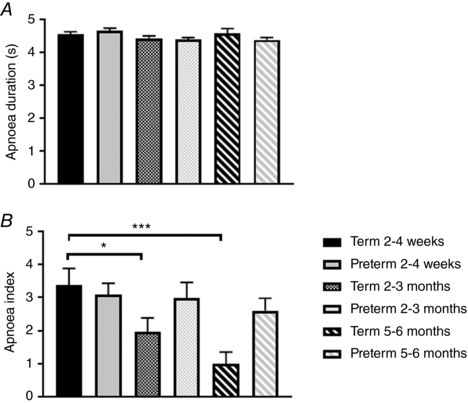

Apnoea duration was not different between term and preterm infants at any age (Fig. 4 A); however, apnoea index was lower at 5–6 months in the term infants (1.0 ± 0.4) compared to the preterm group (2.6 ± 0.4, P < 0.01, Fig. 4 B). There were no effects of postnatal age on apnoea index in the preterm infants; however, apnoea index fell significantly with postnatal age in the term infants (Fig. 4 B). There were no differences in % nadir HR or S pO 2 between groups, at any age. However, % nadir TOI (Fig. 5 A) was significantly greater in the preterm group compared to the term group at 2–4 weeks (−5.3 ± 0.2 vs. −3.1 ± 0.2%, P < 0.001), 2–3 months (−8.2 ± 0.4 vs. −4.2 ± 0.3%, P < 0.001) and 5–6 months (−10.1 ± 0.6 vs. −5.0 ± 0.5%, P < 0.001). The nadir TOI increased with postnatal age in both term and preterm groups (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 4. A, comparison of apnoea duration between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age. B, comparison of apnoea index between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 5. A, comparison of percentage nadir in cerebral oxygenation between term and preterm infants at 2–4 weeks, 2–3 months and 5–6 months corrected age. *** P < 0.001. B, effects of postnatal age on percentage nadir in cerebral oxygenation between term and preterm infants. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Discussion

The majority of studies investigating apnoea and periodic breathing during sleep in infants born at term have not extended past the newborn period and to date none have investigated the impact on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular physiology, nor compared the findings to those of infants born preterm. Our study has identified that short apnoeas and periodic breathing continue to occur during sleep in normal healthy infants across the first 6 months after birth. Apnoea index and the amount of time spent in periodic breathing declined with increasing postnatal age. These data provide normative values which can be used to compare data from preterm infants. When compared to age‐matched infants born preterm, the mean duration of periodic breathing was longer at both 2–4 weeks and 5–6 months of age. Despite this, the fall in cerebral oxygenation was greater in the preterm group compared to the term group at 2–4 weeks, with a similar trend observed at 5–6 months. Apnoea duration was not different between term and preterm infants; however, the decline in apnoea index observed in the term infants was not seen in the preterm infants, and apnoea index was higher in preterm than term infants at 5–6 months of age. Falls in cerebral oxygenation associated with apnoeas were greater in the preterm infants at all three ages studied. Notably, the falls in S pO 2 during the respiratory events were similar between the two groups. Accordingly, the greater fall in cerebral oxygenation in the preterm infants compared to term infants during respiratory events may be due to lower cerebral blood flow or lower haemoglobin level, leading to higher cerebral oxygen extraction. Studies in rat pups exposed to mild intermittent hypoxia, similar to that experienced by preterm infants during apnoea and periodic breathing, during the early postnatal period showed adverse changes in systemic and brain inflammation, and brain structure and metabolism (Darnall et al. 2017). It is yet to be ascertained if the falls in cerebral oxygenation related to apnoea and periodic breathing are associated with the increased incidence of adverse developmental outcomes in infants born preterm.

It has previously been shown that a 10% reduction in cerebral oxygenation is of clinical concern for the development of cerebral hypoxic injury in preterm infants in the neonatal unit (van Bel et al. 2008). In this prospective study of 20 preterm infants with a haemodynamically important patent duct, significantly lower cerebral oxygenation values (62 ± 9%) were found compared to 20‐matched preterm infants without a patent duct (72 ± 10%). As can be seen from Fig. 3 C TOI values fell to or below these levels in preterm infants at 2–3 and 5–6 months post‐term‐equivalent age, with term infants not experiencing these levels at any age studied. In a retrospective analysis of data from a study of over 1000 extremely preterm infants who survived to a postmenstrual age of 36 weeks, the risk of death or disability at 18 months corrected age was positively associated with the percentage of time infants experienced intermittent hypoxia (as measured by pulse oximeter oxygen saturation <80%) or bradycardia (pulse rate <80 min−1) for 10 s or longer whilst in the neonatal unit (Poets et al. 2015). Secondary outcomes of motor impairment, cognitive or language delay, and severe retinopathy of prematurity were also increased. Furthermore, low regional cerebral oxygenation levels in preterm infants in the neonatal unit have been associated with lower neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 months (Alderliesten et al. 2014). In newborn animal models cerebral oxygenation of <55% for more than 2.5 h predicted neurological injury (Hagino et al. 2005). Infants spend 12–16 h each day sleeping, so even if only 5–10% of this time is spent in periodic breathing over the first 3 months of life, this translates to ∼50–100 h of exposure to low cerebral oxygenation levels. Our findings coupled with the increased frequency of both periodic breathing and apnoea in the preterm group across the first 6 months post‐term‐corrected age suggest that even clinically well preterm infants are exposed to significantly greater levels of cerebral hypoxia compared to those born at term. Further studies with neurodevelopmental follow‐up in this population would be required to ascertain if these brief falls in cerebral oxygenation are associated with the neurocognitive deficits which are more prevalent in infants born preterm.

Preterm‐born infants are at significantly greater risk for the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Blair et al. 2006; Malloy, 2013). Early studies suggested that apnoea and periodic breathing may underpin this increased risk of SIDS (Guilleminault et al. 1975; Kelly & Shannon, 1979; Kelly et al. 1980). The Collaborative Home Infant Monitoring Evaluation (CHIME) study of over 1000 infants found that both full term and preterm infants with multiple apnoeic or bradycardic events had less favourable developmental outcomes at 1 year of age, as assessed by the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, compared to those infants with few or no events (Hunt et al. 2004). The study was, however, unable to determine if the respiratory events were causal or both the events and the developmental delays share a common aetiology. Our findings on the changes in cerebral oxygenation provide a potential mechanism and causal link between the respiratory events and developmental delay in both preterm and term infants.

When compared to preterm infants, periodic breathing duration was longer in the term infants at both 2–4 weeks and 5–6 months; however, the percentage of sleep time spent periodic breathing was longer in the preterm infants at all ages with this just failing to reach statistical significance at 2–4 weeks. Apnoea duration was not different between the term and preterm groups at any age; however, the apnoea index (number of apnoeas per hour of sleep) was higher in the preterm group at 5–6 months. The finding that the duration of central apnoeas was not different between term and preterm infants studied longitudinally has been previously reported (Albani et al. 1985). Importantly, the decline in apnoea index with increasing postnatal age observed in the term infants and also reported by others (Brockmann et al. 2013) was not apparent in the preterm infants. Central apnoeas and periodic breathing are more common in infants than in older children and adults and this has been attributed to immaturity of the respiratory system. Although an apnoea index of 3 events h−1 of sleep has conventionally been viewed as benign, the finding that this did not fall in the preterm group with age as it did in the term group highlights that immature respiratory control persists in even healthy preterm infants. The long term consequences of this are currently unknown; however, it may be that respiratory instability persists into childhood as children born preterm are at increased risk of obstructive sleep apnoea (Raynes‐Greenow et al. 2012). It has been suggested exposure to hypoxia or hyperoxia after birth can alter the development of the chemoreflex pathways in animal models (Ling et al. 1997) thus increasing the propensity to develop obstructive sleep apnoea.

Our findings that the effects on cerebral oxygenation were more marked at the older ages than at 2–4 weeks in the term infants were surprising. However, we previously found similar age‐related effects in falls in cerebral oxygenation associated with periodic breathing in the preterm infants (Decima et al. 2015). We suggested that the higher percentage fall in TOI could be in part due to the lower baseline cerebral TOI at 2–3 months of age, which we have reported in this (Fig. 2) and in previous studies in both term (Wong et al. 2011) and preterm infants (Fyfe et al. 2014). Physiologically, we have previously suggested that this age‐related fall in cerebral oxygenation is due to immaturity of cerebral blood flow–metabolism coupling during this period of rapid brain growth with accompanying increases in cerebral oxygen requirements. In addition, there is a physiological anaemia also occurring at 2–3 months (Strauss, 2010), further increasing the cerebral oxygen extraction in order to meet the metabolic demand, resulting in the low TOI. Our finding that FTOE was significantly higher in the preterm infants at this age supports this contention. Thus, any reduction in S pO 2 and cardiac output (as indicated by falls in HR) as occurs during apnoea is likely to have a more marked effect on cerebral oxygenation.

Although there are limited studies on the effects of postnatal age on apnoea frequency beyond term‐equivalent age, studies in term infants have reported a median central apnoea index (mixed and obstructive events were rare) of 5.5 events h−1 at 1 month and 4.1 events h−1 at 3 months, respectively (Brockmann et al. 2013). In this study events were scored according to standard paediatric criteria (Berry et al. 2012) so the short central events scored in our study may have been missed if they did not meet the apnoea criteria and the study did not account for sleep state or sleep position. However, the frequencies of apnoeic events per hour are similar to those reported in our study. Similarly, our apnoea duration of approximately 4 s is comparable to the median central apnoea duration reported in the earlier study (Brockmann et al. 2013). In contrast, another earlier study in preterm and term infants reported a much higher frequency of apnoeic events across the 6 months post‐term equivalent age. At term‐equivalent age, preterm infants had an apnoea frequency of 126 (100 min)−1 (76 h−1) compared to term infants (49 (100 min)−1 (29 h−1) (Albani et al. 1985). As in our study all apnoeas ≥3 s were scored by Albani et al.; however, preterm infants were born at later gestational ages (32.2–36.6 weeks of gestational age). It is unclear why the infants in this previous study (Albani et al. 1985) had significantly more events than are reported in our current study. Also in contrast to our study, which found a significant progressive fall in apnoea index in the term group but not the preterm group with significant difference between groups at 5–6 months, the study by Albani et al. found a reduction in apnoea index at 52 weeks compared to both 40 and 60 weeks post‐conceptional age (Albani et al. 1985).

We acknowledge that a limitation to this study was our indirect measurement of cerebral oxygenation and peripheral oxygen saturation; however, these methods have been well validated and are widely used both clinically and in research studies. We also acknowledge our small sample size of 24 preterm and 17 term infants and the wide gestational age at which the preterm infants were born. However, our analysis showed that gestational age did not affect the incidence or duration of apnoea or periodic breathing in the preterm group and our study design allowed repeated measures analysis to examine the effects of sleep state and sleeping position on cerebral oxygenation, heart rate and oxygen saturation. Our exclusion criteria for preterm infants of those infants diagnosed with significant intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH grades III or IV), intrauterine growth restriction and those who were on supplemental oxygen at the time of the studies precluded inclusion of infants born at very young gestational ages and thus our study reports findings on a relatively “healthy” group of preterm infants. We also acknowledge that our studies were conducted during the day with infants sleeping 2–3 h at each study. However, we have no reason to expect that apnoea duration, frequency or the effects on HR, S pO 2 or TOI would be different if studies had been conducted overnight, as infants of these ages routinely sleep during both daytime and night‐time in similar lengths of sleep bouts.

Conclusions

Periodic breathing and short apnoeas were more common in infants born preterm after term‐corrected age than those born at term. Despite episodes of periodic breathing being longer in the term group and no difference in apnoea duration between groups, falls in cerebral oxygenation were greater in the preterm group. The clinical significance of this on neurodevelopmental outcomes and the development of obstructive sleep apnoea is unknown and warrants further investigations.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

The study was carried out in The Ritchie Centre and Melbourne Children's Sleep Centre. R.S.C.H. conceived the study, obtained funding, carried out statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; S.R.Y. and K.L.F. collected the data; S.S. and A.O. assisted with data analysis; F.Y.W. contributed to interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia APP1006647, the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program and The Lullaby Trust (UK). F. Y. Wong is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1084254).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the parents who volunteered their infants for this study and the staff of the Melbourne Children's Sleep Centre where the studies were carried out. This research paper is dedicated to the memory of the late Professor Julian (Bill) Parer; friend, mentor and clinician‐scientist whose perinatal research curiosity inspired us.

Biography

Rosemary Horne is a Senior Principal Research Fellow and heads the Infant and Child Health research theme within the Ritchie Centre, Hudson Institute of Medical Research and Department of Paediatrics, Monash University, Australia. Her research interests focus on numerous aspects of sleep in infants and children. Rosemary has published more than 170 scientific research and review articles. She is Chair of the Physiology working group of the International Society for the Study and Prevention of Infant Deaths and the Red Nose (formerly SIDS and Kids Australia) National Scientific Advisory Group, a Director of the International Paediatric Sleep Association, and is on the editorial boards of the Journal of Sleep Research, Sleep and Sleep Medicine.

Edited by: Laura Bennet & Philip Ainslie

References

- Albani M, Bentele KH, Budde C & Schulte FJ (1985). Infant sleep apnea profile: preterm vs. term infants. Eur J Pediatr 143, 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderliesten T, Lemmers PM, van Haastert IC, de Vries LS, Bonestroo HJ, Baerts W & van Bel F (2014). Hypotension in preterm neonates: low blood pressure alone does not affect neurodevelopmental outcome. J Pediatr 164, 986–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders TF, Emde R & Parmelee A (1971). A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Criteria for Scoring of States of Sleep and Wakefulness in Newborn Infants. UCLA Brain Information Services/BRI Publications Office, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, Marcus CL, Mehra R, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Redline S, Strohl KP, Davidson Ward SL & Tangredi MM; American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2012). Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 8, 597–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair PS, Platt MW, Smith IJ & Fleming PJ (2006). Sudden infant death syndrome and sleeping position in pre‐term and low birth weight infants: an opportunity for targeted intervention. Arch Dis Child 91, 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann PE, Poets A & Poets CF (2013). Reference values for respiratory events in overnight polygraphy from infants aged 1 and 3 months. Sleep Med 14, 1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JL & Agarwal A (2010). Development of ventilatory control in infants. Paediatr Respir Rev 11, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnall RA, Chen X, Nemani KV, Sirieix CM, Gimi B, Knoblach S, McEntire BL & Hunt CE (2017). Early postnatal exposure to intermittent hypoxia in rodents is proinflammatory, impairs white matter integrity, and alters brain metabolism. Pediatr Res 82, 164–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decima PF, Fyfe KL, Odoi A, Wong FY & Horne RS (2015). The longitudinal effects of persistent periodic breathing on cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants. Sleep Med 16, 729–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore JM, Martin RJ & Gauda EB (2013). Apnea of prematurity – Perfect storm. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 189, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BA, Sands SA & Berger PJ (2013). Postnatal maturation of breathing stability and loop gain: the role of carotid chemoreceptor development. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 185, 144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenwald EC; Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics (2016). Apnea of prematurity. Pediatrics 137, e20153757. [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe KL, Yiallourou SR, Wong FY, Odoi A, Walker AM & Horne RS (2014). Cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants. Pediatrics 134, 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg‐Damberger MM (2016). The visual scoring of sleep in infants 0 to 2 months of age. J Clin Sleep Med 12, 429–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilleminault C, Peraita R, Souquet M & Dement WC (1975). Apneas during sleep in infants: possible relationship with sudden infant death syndrome. Science 190, 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagino I, Anttila V, Zurakowski D, Duebener LF, Lidov HG & Jonas RA (2005). Tissue oxygenation index is a useful monitor of histologic and neurologic outcome after cardiopulmonary bypass in piglets. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 130, 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson‐Smart D (1981). The effect of gestational age on the incidence and duration of recurrent apnoea in newborn babies. Aust Paediatr J 17, 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne RS, Fung AC, NcNeil S, Fyfe KL, Odoi A & Wong FY (2017). The longitudinal effects of persistent apnea on cerebral oxygenation in infants born preterm. J Pediatr 182, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt CE, Corwin MJ, Baird T, Tinsley LR, Palmer P, Ramanathan R, Crowell DH, Schafer S, Martin RJ, Hufford D, Peucker M, Weese‐Mayer DE, Silvestri JM, Neuman MR & Cantey‐Kiser J (2004). Cardiorespiratory events detected by home memory monitoring and one‐year neurodevelopmental outcome. J Pediatr 145, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier A, Khairy M, Kokkotis A, Cormier C, Messmer D & Barrington KJ (2004). Apnea is associated with neurodevelopmental impairment in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 24, 763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DH & Shannon DC (1979). Periodic breathing in infants with near‐miss sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics 63, 355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DH, Walker AM, Cahen L & Shannon DC (1980). Periodic breathing in siblings of sudden infant death syndrome victims. Pediatrics 66, 515–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L, Olson EB Jr, Vidruk EH & Mitchell GS (1997). Developmental plasticity of the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol 110, 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy MH (2013). Prematurity and sudden infant death syndrome: United States 2005–2007. J Perinatol 33, 470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RJ, Wang K, Koroglu O, Di Fiore J & Kc P (2011). Intermittent hypoxic episodes in preterm infants: do they matter? Neonatology 100, 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (1986). Infantile apnea and home monitoring. NIH Consens Statement Online 1986 Sep 29–Oct 1 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pillekamp F, Hermann C, Keller T, von Gontard A, Kribs A & Roth B (2007). Factors influencing apnea and bradycardia of prematurity – implications for neurodevelopment. Neonatology 91, 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poets CF, Roberts RS, Schmidt B, Whyte RK, Asztalos EV, Bader D, Bairam A, Moddemann D, Peliowski A, Rabi Y, Solimano A & Nelson H; Canadian Oxygen Trial Investigators (2015). Association between intermittent hypoxemia or bradycardia and late death or disability in extremely preterm infants. JAMA 314, 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynes‐Greenow CH, Hadfield RM, Cistulli PA, Bowen J, Allen H & Roberts CL (2012). Sleep apnea in early childhood associated with preterm birth but not small for gestational age: a population‐based record linkage study. Sleep 35, 1475–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RG (2010). Anaemia of prematurity: pathophysiology and treatment. Blood Rev 24, 221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bel F, Lemmers P & Naulaers G (2008). Monitoring neonatal regional cerebral oxygen saturation in clinical practice: value and pitfalls. Neonatology 94, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MH, Skuza EM, Rennie GC, Sands SA, Yiallourou SR, Horne RS & Berger PJ (2007). Postnatal development of periodic breathing cycle duration in term and preterm infants. Pediatr Res 62, 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong FY, Witcombe NB, Yiallourou SR, Yorkston S, Dymowski AR, Krishnan L, Walker AM & Horne RS (2011). Cerebral oxygenation is depressed during sleep in healthy term infants when they sleep prone. Pediatrics 127, e558–e565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]