Abstract

An elective laparoscopic ovariectomy on a healthy dog revealed a cystic structure in the left ovary. The surgical procedure was successful. Histopathological examination showed the presence of a teratoma adjacent to the ovary. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first reported case of an ovarian teratoma removed by laparoscopic ovariectomy in a dog by using a multiport laparoscopic ovariectomy technique.

Keywords: dogs, laparoscopy, ovariectomy, teratoma

Ovarian diseases are rare in female dogs [2], but the most common ovarian diseases seem to be cystic ovaries and ovarian tumors [1]. The types of tumors that have originated from the primordial germ cells of the ovary, dysgerminoma, teratoma, and embryonal carcinoma, are rare, observed in 6–12% [4] or 20% [8] of canine ovarian neoplasms. Ovariectomy is therapeutic under most conditions and is suggested by many authors [3,7]. Being less invasive and requiring less hospitalization time [6] than other procedures, laparoscopic procedures are becoming more frequently applied in veterinary and human medicine [10]. The aim of this report is to describe a single successful case of a laparoscopic ovariectomy in which a teratoma was found and removed. We show that, in the patient presented in this report, the procedure was feasible and there was no need to convert to an open procedure.

A mixed-breed dog of an estimated age of approximately 2 years, clinically healthy, and weighing 23.45 kg, was admitted to the Oeiras Veterinary Hospital to undergo an elective laparoscopic ovariectomy. The dog had been adopted from a dog shelter and its previous history was unknown.

The dog's owner signed a consent document advising of the risks of laparoscopic ovariectomy and the possible necessity of converting to an open celiotomy in case of an emergency situation such as hemorrhage or iatrogenic injury. The animal was kept and the procedure was performed in accordance with the Portuguese government's Animal Care Guidelines (Decree-Law No. 260/2012).

Physical examination of the dog during a pre-surgical appointment was unremarkable; the dog's respiratory and cardiac functions were considered normal and the animal was very active. Hematological and biochemical parameters were within normal limits.

The dog was premedicated with acepromazine (Calmivet; Vetoquinol, Portugal) 0.05 mg/kg and tramadol (Tramadol Labesfal; Labesfal, Portugal) 5 mg/kg intravenous (IV), and anesthesia was induced with 4 mg/kg IV propofol (Propofol Lipuro; B. Braun Medical, Portugal). General anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (Vetflurane; Virbac, Portugal) in oxygen. At induction, 8.75 mg/kg Synulox (7.0 mg amoxicillin and 1.75 mg clavulanic acid; Zoetis, Portugal) was administered subcutaneously and administration was continued postoperatively as a part of a standard protocol. The dog was closely monitored during the surgical procedure via pulse oximetry and electrocardiography. IV fluid therapy (NaCl 0.9%, Soro Fisiológico Braun Vet; B. Braun Medical) was administered during the procedure and through the subsequent 8 h.

For abdominal access, the pneumoperitoneum was established with a Veress needle (2.1 mm; Richard Wolf, USA) inserted after the xiphoid process. CO2 was provided via automatic insufflator (Electronic Insufflator 2002; Cabot Medical, USA) with a gas flow of 9 L/min at a pressure set to 9 to 11 mmHg. The first cannula (threaded, 5.5 mm in all cases) was placed 2 cm caudal to the umbilicus. A perimeter mark was made with the cannula to achieve the length of the incision and a number 11 scalpel blade was used to make the skin and linea alba incisions. The telescope (5.3 mm, 0°, Panoview; Richard Wolf) was inserted and the abdomen was evaluated using a standard clockwise rotation to access the possibility of iatrogenic injury. Additionally, two cannulas were placed 5 cm cranial and 5 cm caudal to the first cannula, under direct vision of the telescope. The dog was positioned in right lateral recumbency and the telescope, which was placed in the cranial port, was handled by an assistant, while the surgeon maneuvered the dissecting/grasping forceps in the middle port and the bipolar forceps in the caudal port.

With the subject in right lateral recumbency, observation of the left ovary area revealed the presence of a cystic structure with a hard consistency and a grossly normal non-gravid uterus. The left ovarian pedicle, proper ligament, and suspensory ligament were sealed and transected by using a high-frequency bipolar forceps with an integrated blade (RoBi plus forceps; Karl Storz, Germany). Then the proper ligament of the ovary was grasped, elevated, and tacked to the body wall by passing a 40 mm, half circle, curved cutting needle, and sutured percutaneously through the body wall. The dog was then positioned in left lateral recumbency and the instruments placed in inverted order in the three ports. The ovarian structures had no macroscopic abnormalities and the ovariectomy was performed using the same techniques as that just described. No additional masses were detected in the abdominal viscera or the abdominal wall, and no intraabdominal or peripheral lymph nodes were enlarged. There were no additional abnormalities noted during examination of the abdomen. The dog was then tilted in right lateral recumbency, the caudal cannula pulled out, the 1 cm incision extended to 2 cm and ovaries removed from the abdomen. The ovaries were checked to ensure complete removal and the pneumoperitoneum was released. The three portals were then removed and the abdominal incisions closed in two layers using a 2/0 absorbable synthetic monofilament glyconate suture (Monosyn; B. Braun) in a simple interrupted suture pattern. When the surgical procedure was completed the dog received a 0.2 mg/kg subcutaneous dose of meloxicam (Metacam; Boehringer Ingelheim, Portugal). All surgically removed structures were fixed in a 10% formalin solution and processed for histopathological evaluation. One day after the surgery, the dog was discharged home with 0.1 mg/kg meloxicam per orally for two days. On gross examination, both ovaries were enclosed within an ovarian bursa. The right and left ovaries had a regular appearance, with hard consistency and a dark brown color. Adjacent to the left ovary there was a cystic structure, measuring 2.5 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm, with a whitish, fibrous wall as well as hairs and sebaceous content (Figs. 1 and 2). Histopathological examination showed both ovaries to have no changes of pathological significance. The cystic structure next to the left ovary was surrounded by epidermis and had a lumen filled with keratin and hair. Adjacent to the cyst, there were well defined sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and several inflammatory infiltrates populated with macrophages and ceroid pigment (Fig. 3). A diagnosis of a dermoid cyst (teratoma) was made.

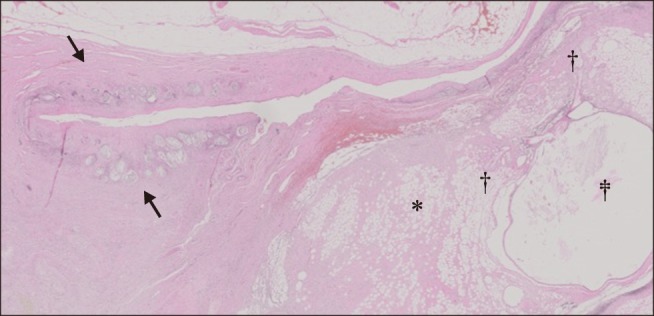

Fig. 1. Left ovary and teratoma. The arrows indicate atresic follicles. Indicated by symbols are abundant adipose tissue (*), multiple hair follicles and sebaceous glands (†), and a cystic follicle with stratified epithelium and keratin inside it (‡). H&E stain. 40×.

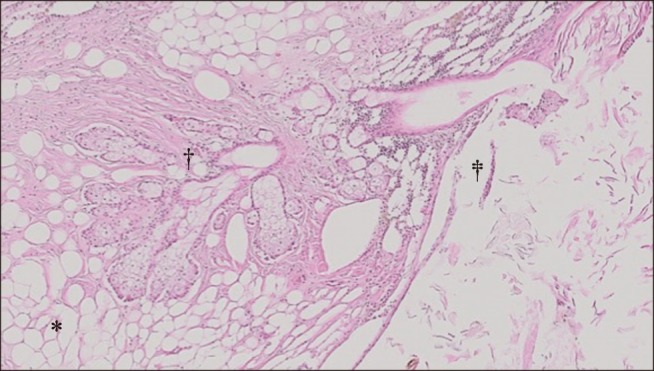

Fig. 2. Left ovary and teratoma. The symbols indicate sebaceous glands and hair follicles (*), cystic follicle with stratified epithelium (†), and keratin (‡). H&E stain. 100×.

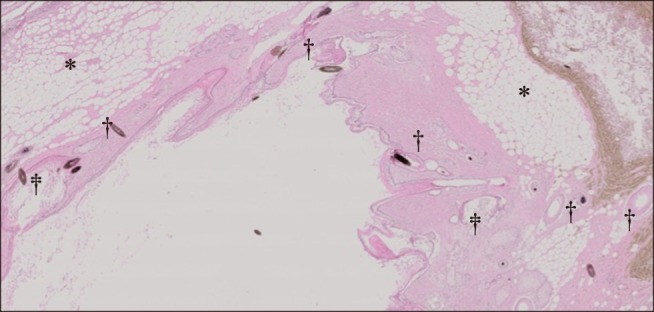

Fig. 3. Left ovary and teratoma. Symbols indicate abundant adipose panicle (*) and epidermis and dermis with several hair follicles (†) and keratin (‡). H&E stain. 40×.

The cyst was lined by well-differentiated skin with keratinization, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles. On the basis of the morphological observations, the cyst was considered a teratoma attached to the left ovary. As described in previous studies, teratomas seem to occur more frequently on the left side of dogs, and generally, ovarian tumors have a predilection for the left ovary, as observed in this dog, although the reason remains unknown [5,9,11].

At follow-up, one year after surgery, the dog was clinically normal and abdominal ultrasound did not indicate the presence of anatomical alterations in the abdominal organs nor the presence of free abdominal fluid.

Laparoscopic surgery may be particularly relevant to ovarian teratoma removal, where detailed examination of the ovarian structures is required and where an open laparotomy approach would most likely require a larger abdominal incision. Based on a recent case report in which a larger teratoma was successfully removed by a single incision laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy [5], and on our experience in the present case, we suggest that laparoscopic techniques for the removal of ovarian teratomas can be used as a viable minimally invasive treatment for ovarian neoplasia.

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first reported case of a teratoma removed by laparoscopic ovariectomy in a dog by using a multiport laparoscopic ovariectomy technique. Further study involving a large sample size is required to evaluate the benefits and risks associated with laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of ovarian neoplasia in dogs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Arlt SP, Haimerl P. Cystic ovaries and ovarian neoplasia in the female dog - a systematic review. Reprod Domest Anim. 2016;51(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/rda.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SD, Kustritz MVR, Olson PNS. Disorders of the canine ovary. In: Johnston SD, Kustritz MVR, Olson PNS, editors. Canine and Feline Theriogenology. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia; 2001. pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapatkin AS, Fordyce HH, Mayhew PD, Smith GK. Canine hip dysplasia: the disease and its diagnosis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2002;24:526–538. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein MK. Tumors of the female reproductive system. In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, editors. Withrow & MacEwen's Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 610–618. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez D, Singh A, Wright TF, Gartley C, Walker M. Single incision laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy for an ovarian tumor in a dog. Can Vet J. 2017;58:975–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matyjasik H, Adamiak Z, Pesta W, Zhalniarovich Y. Laparoscopic procedures in dogs and cats. Pol J Vet Sci. 2011;14:305–316. doi: 10.2478/v10181-011-0049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEntee MC. Reproductive oncology. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2002;17:133–149. doi: 10.1053/svms.2002.34642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patnaik AK, Greenlee PG. Canine ovarian neoplasms: a clinicopathologic study of 71 cases, including histology of 12 granulosa cell tumors. Vet Pathol. 1987;24:509–514. doi: 10.1177/030098588702400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rota A, Tursi M, Zabarino S, Appino S. Monophasic teratoma of the ovarian remnant in a bitch. Reprod Domest Anim. 2013;48:e26–e28. doi: 10.1111/rda.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tapia-Araya AE, Díaz-Güemes Martin-Portugués I, Bermejo LF, Sánchez-Margallo FM. Laparoscopic ovariectomy in dogs: comparison between laparoendoscopic single-site and three-portal access. J Vet Sci. 2015;16:525–530. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2015.16.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi Y, Sato T, Shibuya H, Tsumagari S, Suzuki T. Ovarian teratoma with a formed lens and nonsuppurative inflammation in an old dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2004;66:861–864. doi: 10.1292/jvms.66.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]