ABSTRACT

Informed choice is an expectation of today’s parents. Concern is evident around whether education models are evolving to ensure flexibility for parents to access options perceived as meeting their needs. Historical and current evidence around childbirth education models including the introduction of mindfulness to parent education will be presented. The aim of this article is to describe the rationale for incorporating adult and experiential learning with mindfulness-based stress reduction in a childbirth education program implemented in Western Australia. The curriculum of the Mindfulness Based Childbirth Education 8-week program is shared with corresponding learning objectives for each session. Examples of educational materials that demonstrate how adult and experiential learning were embedded in the curriculum are presented.

Keywords: mindfulness, childbirth education, adult learning, experiential learning

In Australia, as in other Western countries, antenatal education is seen as an essential component of antenatal care (Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2008). However, even with the popularity and routine nature of attendance at these education sessions, evidence differentiating the benefits and effective educational approaches remains uncertain, particularly for first-time parents (Gagnon & Sandall, 2007). Notwithstanding, many women consider these sessions an important source of information about birth (Regan, McElroy, & Moore, 2013). The aim of antenatal education is to provide expectant parents with strategies to support pregnancy, childbirth, and parenthood (Ahldén, Ahlehagen, Dahlgren, & Josefsson, 2012) and, more specifically, provide a space where health-promoting behaviors can be positively influenced and women’s confidence for birthing increased. They are also seen as an avenue for the provision of information on pain and pain relief and the promotion of breastfeeding (Brixval, Axelsen, Andersen, Due, & Koushede, 2014).

Attending antenatal classes may also enable women to fulfill one of the four tasks that childbearing women have been theorized to be driven to complete, namely, to seek safe passage for herself and her child through pregnancy, labor, and birth (Rubin, 1976). Research, however, has not shown strong associations between antenatal class attendance and the experience of childbirth (Koehn, 2002; Spiby, Slade, Escott, Henderson, & Fraser, 2003). More recently, expecting fathers have become an integral part of antenatal classes (Brixval et al., 2014). However, women and their support person may not be gaining the necessary skills they need during childbirth education to prepare them for birth or early parenting (Renkert & Nutbeam, 2001).

Traditionally, antenatal education was restricted to the latter stages of pregnancy, focused on labor and birth and was developed by health professionals who typically delivered the programs in large groups in a predominantly didactic style (Svensson et al., 2008). Changes, however, started to occur in the 1970s in Australia with a greater involvement of midwives (Reiger, 2001). This became more pronounced in the 1980s. The 1990s was a pivotal moment for hospital-based antenatal education in Australia with many programs changing to small-group interactive learning. The instructor, however, still largely retained control. Contemporarily, it is argued that antenatal education should provide opportunities for attendees to learn skills to practice desired behaviors and be based on the principles of adult learning (Svensson et al., 2008). In the electronic age, an increasing number of antenatal learning forums and programs are available online for expectant parents. These cannot, however, provide the “human” element and interaction that comes with face-to-face classes and that which midwife academic Marlene Sinclair (2013) argues has the unique capacity to facilitate learners to generate their own knowledge.

CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION

Walker, Visger, and Rossie (2009) provide an overview of a range of childbirth education models. They suggest that the work of Grantly Dick-Read (1890–1959), a British obstetrician and leading advocate of natural childbirth, has had a profound impact on childbirth education and provides the foundation for three education models today: Lamaze, the Bradley Method, and Hypnobirthing. Lamaze is a philosophy that provides foundation and direction for women as they prepare for childbirth and motherhood. Classes typically include 12 hours of classroom activities in the third trimester of pregnancy either weekly or in an intensive format with class sizes limited to 12 pregnant women and their support persons. The emphasis is on experiential learning and includes strategies to incorporate the beliefs and cultural values of participants. The Bradley Method is a “partner-coached” natural birth model. The emphasis is on birth as a shared experience and prepares couples to birth naturally without unnecessary medical interventions. The role of the partner as “coach” is foundational to enable him or her to provide support during labor and ensure a supportive environment. Hypnobirthing supports women and their families to frame expectations abound birth positively with little use of medical model terms in its written documentation. It teaches deep relaxation, visualization, and self-hypnosis with an emphasis on birthing not needing to be painful.

Mindfulness

Another emerging childbirth education model applies adaptations of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program (Kabat-Zinn, 2013) to pregnancy and early parenting. Mindfulness incorporates concepts of paying attention on purpose, in the present moment and being nonjudgmental, and Kabat-Zinn (2013) proposes techniques to foster moment-to-moment, nonjudgmental awareness through meditation. Currently, the MBSR program has a multitude of applications. For example, clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions for improving mood and quality of life for those experiencing chronic lower back pain (Morone, Greco, & Weiner, 2008), fibromyalgia (Schmidt et al., 2011), irritable bowel syndrome (Gaylord et al., 2011), multiple sclerosis (Grossman et al., 2010), and cancer (Speca, Carlson, Goodey, & Angen, 2000).

Mindfulness incorporates concepts of paying attention on purpose, in the present moment and being nonjudgmental, and Kabat-Zinn proposes techniques to foster moment-to-moment, nonjudgmental awareness through meditation.

One of the most promising mindfulness-based applications is the integration of mindfulness with cognitive therapy in the Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) program. MBCT has demonstrated positive impact in preventing depressive relapse (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2013). In summary, mindfulness-based interventions and their successes exceed the snapshot of applications or interventions presented here, and these outcomes suggest mindfulness may have useful applications in other areas, such as pregnancy and parenting.

Evidence using MBSR interventions around childbirth or parenting are beginning to emerge, although the focus tends to be on clinical populations such as parents of children with disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity (Anderson & Guthery, 2015) and parents with youth attending a Strengthening Families Program (Coatsworth et al., 2015). The concept of integrating mindfulness with parent training as a health promotion strategy is at an early stage with outcomes predominantly focusing on reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, given the strong evidence linking mindfulness to the prevention of a depressive relapse (Segal et al., 2013), applications of mindfulness during the antenatal and early parenting period may well inoculate women against the onset of postnatal depression (PND) by building resilience to the demands of early parenting.

Maternal Mental Health

PND is the most prevalent mood disorder associated with childbirth and affects up to 15% of Australian childbearing women (National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], 2008). Factors that protect against PND include optimism and positive self-esteem, access to social support which includes being in a stable, supportive relationship with a partner, and the quality of the woman’s relationship with her parents (NHMRC, 2008). Having realistic expectations as well as access to information about pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting traditionally provided in childbirth education has also been suggested as providing a protective effect (NHMRC, 2008). The opportunity to build capacity by recognizing and building on protective factors, which can be regarded as strengths, is a concept introduced in the 1970s by Aaron Antonovsky (1979). Early detection and treatment for the 15% of women identified to be affected by PND is a health priority; however, the question of how we can assist the remaining 85% of mothers to not only maintain their mental health but also build personal capacity and strengthen their health reserves warrants greater attention. Moreover, it seems that skill-based antenatal programs have not been determined a sufficient protective factor in the development of PND (Brugha et al., 2000), so mindfulness-based interventions may show promise in building this resilience.

Aside from hypnobirthing, antenatal programs do not traditionally offer stress reduction techniques to pregnant women and their birth support person, even though research suggests that stress and anxiety during pregnancy contribute to lower birth weight, shorter gestation, and emotional and behavioral problems in children (O’Connor, Heron, Golding, Beveridge, & Glover, 2002; Talge, Neal, & Glover, 2007). Because of the demonstrated long-term effects on children of stress during pregnancy, mindfulness-based programs such as MBSR or the relevant applications seem warranted and indeed could contribute to best practice in health promotion during pregnancy (van den Bergh, Mulder, Mennes, & Glover, 2005).

Mindfulness and Parenting

Duncan and Bardacke (2009) adapted MBSR into Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting, which incorporated 3-hour weekly meetings over 9 weeks as well as a daylong retreat and postpartum reunion. Participants were American women who practiced meditation and yoga for 30 minutes, 6 days per week and mindfulness in daily life while being supported at home with a workbook and CDs. Results from this pilot study with 27 pregnant women found significant increases in mindfulness (p < .0001) and positive affect (p = .024) together with decreases in anxiety (p < .0001), depression (p = .016), and negative affect (p = .003; Duncan & Bardacke, 2009, p. 14). The study profile represented primiparous (93%) White (89%) women with an average age of 34 years who had attended graduate school or achieved a master’s doctoral degree (63%), experienced a major stressful life event during pregnancy (70%), and had prior experience with meditation or yoga (93%). The integration of yoga into antenatal education is not uncommon (Remer, 2012).

An Australian pilot study of an antenatal mindfulness intervention entitled the MindBabyBody program incorporated two components to their evaluation to determine differences in depression, anxiety, and stress; a randomized control trial with 32 women and a nonrandomized trial with 20 women (Woolhouse, Mercuri, Judd, & Brown, 2014). In both components, significant improvements in depression and anxiety were found within groups. However, differences between the intervention and usual care group were not significant.

A recent initiative in Australia involved the release of a free Mindfulness Meditation application (“app”) entitled “Mind the Bump” for mobile phones to support women and their partners’ mental and emotional well-being during preparation for their upcoming birth and transition to becoming new parents (Mind the Bump, 2014). The Mind the Bump app was released during PND awareness week in November 2014 and provides tailored exercises to support mental and emotional well-being from early pregnancy through to the first 2 years of the child’s life through the provision of information on brain education, mindfulness, and a child’s brain development. Building family resilience with vulnerable families in a context of adversity has been recognized (Walsh, 2002), but the potential reach of this app to the wider population and not just those women identified as having or being at risk for PND does offer the opportunity for all parents to increase resilience and build their capacity as a new parent. For those who have suffered a previous depressive episode, the tool could assist in preventing a relapse (Segal et al., 2013).

Parents Expectations and Experiences

Insight into what parents want is essential to meet the changing needs of parents as access to information is readily available from the Internet and online resources; this presents both opportunities and challenges (Buultjens, Robinson, & Milgrom, 2012; Young, 2010). Results from a Scottish study found that women expressed variable feedback around the importance of “in person” childbirth education with some suggesting there was no need for it (Hollins Martin & Robb, 2013). An American study also confirmed that women were using informal sources for information such as family, friends, the Internet, and television rather than attending classes (Martin, Bulmer, & Pettker, 2013). To ensure education is perceived as relevant and beneficial, ongoing feedback from parents, and the use of that feedback to make appropriate adjustments to programs, is crucial for the long-term sustainability of this educational approach.

As such, research has been undertaken to understand participant expectations of antenatal education classes. A Swedish study with 1,117 women and 1,019 partners found the top two reasons for both parents attending education classes were expectations that it will assist them to feel more secure as a parent and secure in caring for their newborn (Ahldén et al., 2012). Women assumed that classes would assist them to manage the birth and allow the opportunity to meet other expectant parents. Meeting other parents was not ranked as highly by partners who placed this reason sixth compared to third for women. The importance of being able to connect with new friends during the transition to motherhood was confirmed in a British study (Nolan et al., 2012).

Having informed choice is an expectation of parents in the early 21st century, who recommended three different program types to address changing learning needs across the childbirth continuum (Svensson et al., 2008). “Hearing detail and asking questions” involves a formal structure with a lecture style, whereas “learning and discussing” is more democratic with mini-lectures incorporating group discussions. The final program type “sharing and supporting each other” involves a facilitator and informal structure wherein the facilitator is flexible and able to respond to group needs (Svensson et al., 2008). Educators who can be innovative and adaptive to address the needs of parents are recognized as being particularly valuable (Zhou, 2013). Flexibility and the ability to tailor classes to the audience’s self-identified needs may address evidence that suggests more marginalized groups, for example, young, single mothers with lower educational levels who smoke (Fabian, Rådestad, & Waldenström, 2005) find classes to be least helpful.

CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION AND PEDAGOGY

It has been argued that childbirth education is at a crossroads (Walker et al., 2009), and questions are raised as to whether this education has evolved to keep abreast of the needs of parents (Jolivet & Corry, 2010). Women have access to more information about pregnancy and childbirth than ever before. The increase in the range of models for childbirth education and ensuring they are delivered in innovative and pedagogically sound ways is argued to be necessary to broaden and revive the interests of pregnant women (and their partners) in attending and engaging in this education (Jolivet & Corry, 2010). It is also deemed essential to providing women and their partners with the skills they need to navigate pregnancy, birth, and early parenting. Therefore, we need to consider not only what prospective parents want from antenatal education but also how they want it delivered.

Principles underpinning adult learning and experiential learning have been perceived across a range of studies as being important and useful for antenatal education (Remer, 2012; Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2009). In addition, many prospective parents consider that including problem-based and skills-based activities related to labor, birth, and parenting increase self-confidence and self-efficacy (Byrne, Hauck, Fisher, Bayes, & Schutze, 2014). Essentially, an ideal pedagogy for antenatal education is one that is conducive to learning, incorporates different approaches to learning such as visual, auditory, and kinesthetic plus incorporates a range of different activities (Zhou, 2013). An approach that actively engages partners along with expectant mothers has been shown to have a positive impact on the confidence of the partner to support the expectant mother during labor and childbirth (Koehn, 2002). In addition, providing a space where participants can learn from their peers as well as from “experts” is well regarded by participants (Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2006) as is positive language from facilitators (Hotelling, 2013).

Many prospective parents consider that including problem-based and skills-based activities related to labor, birth, and parenting increase self-confidence and self-efficacy.

MINDFULNESS-BASED CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION PROGRAM IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

The Mindfulness-Based Childbirth Education (MBCE) program described hereafter unites two disparate fields of evidence-based practice—namely, skills-based education and mindfulness—to improve emotional functioning and well-being in pregnancy, during birth, and early parenting. Parent-centered pedagogy guided development of workshop style sessions rather than didactic presentations on pregnancy, birth, and early parenting information. The MBCE acknowledges pregnant women and their partners as active learners through group work, role play, and decision making using the BRAIN (benefits, risks, alternatives, intuition, nothing) or BRAND (benefits, risk, alternative, now-or-later, decision) models which are popular among childbirth educators (Kaufman, 2007). The 8-week program of weekly 2.5-hour sessions also incorporated daily mindfulness meditation homework as prospective parents received a workbook and homework CDs to guide their daily practice of mindfulness meditation. The key components and learning objectives of the eight sessions is provided in Table 1. Each session incorporated education and mindfulness and was facilitated by one staff member who was a qualified childbirth educator, specialist antenatal yoga teacher, and mindfulness meditation teacher.

TABLE 1. Mindfulness-Based Childbirth Education: Overview of Sessions and Learning Objectives.

| Session 1 | Learning Objectives |

| The journey of pregnancy and birth | |

| Getting to know each other | Describe what mindfulness is and how it works. |

| Mindfulness meditation | Developing the ability to analyze how the social context of birth impacts on the experience and expectations of birth |

| Expectant versus active management and decision making | To apply the theory of active and expectant care models to personal choices |

| Able to assess which model of care they have chosen | |

| Ability to compare and contrast the differences between the model of care desired and the model of care adopted by their carer | |

| Session 2 | Learning Objectives |

| Mindfulness of breath | |

| Whose decision? | To analyze the roadblocks to developing a daily mindfulness practice and to find ways to integrate mindfulness into daily life and routine |

| Mindfulness and sensations | To understand the stages of labor and describe the relevant strategies available to cope with each stage |

| Awareness of roadblocks to mindfulness practice | To cultivate nonreactive awareness of sensations to improve maternal comfort during labor |

| Awareness of prevention in well-being, pregnancy, birth, and parenting | |

| Stages of labor | |

| Maternal comfort during labor | |

| Session 3 | Learning Objectives |

| Intervention | |

| Breathing for labor continued and yoga postures based on optimal fetal positioning (OFP) | To understand the “cascade of intervention” |

| Meditation with birth support person | To understand the risks and benefits of different types of interventions |

| Intervention charts: In groups of four, write in each section of the chart: What is it? When is it used? How? Advantages and disadvantages? | To understand standard hospital procedures (such as vaginal examinations upon arrival to hospital and “trace” scans upon admission) |

| Able to describe advantages and disadvantages of different types of interventions | |

| Able to use breath awareness to work with thoughts and sensations | |

| To understand how we can use our breath as an anchor in the midst of changing emotions and sensations | |

| To understand OFP and how yoga encourages OFP | |

| Session 4 | Learning Objectives |

| The journey of pregnancy and birth | |

| Mountain meditation | To describe the main fears associated with pregnancy |

| OFP yoga | To describe the relationship between thoughts and fears and how mindfulness of thoughts can enable us to more clearly understand and work with fear |

| To be able to use problem-solving skills to identify fears and to find suitable solutions if these fears were to become real | |

| To analyze and describe how to implement the theory of OFP to help during labor | |

| Through practicing the mountain meditation, experience the transient nature of thoughts and sensations and interpret and describe how this experience may help in labor. | |

| Session 5 | Learning Objectives |

| The journey of pregnancy and birth | |

| Seated meditation | To compare the difference between informed decisions and informed consent |

| Practice a short mindful yoga routine together based on principles of OFP and using the yoga breathing for birth practiced in earlier weeks. | To understand how to ask further information from your caregiver(s) to make an informed choice |

| Role play a scenario in a caregivers office, modeling the difference between informed choice and informed consent | To apply the BRAIN (benefits, risks, alternatives, intuition, nothing) model for making decisions to a particular intervention |

| Yoga positioning for birth and support techniques | To describe the purpose of different yoga postures and how they may benefit a women during labor (e.g., slow down postures, speed up postures) |

| To describe and use positions and nonpharmacological support techniques for women during labor | |

| To apply the understanding of seated mindfulness to mindfulness into movement by practicing walking meditation | |

| Session 6 | Learning Objectives |

| The journey of pregnancy and birth | |

| Seated mindfulness meditation | To understand how to make informed choices and how to evaluate different options |

| Yoga and support postures | To develop the necessary communication and decision-making skills to make informed choices through role play |

| Ice activity | To analyze the way in which thoughts relate to our fears and worries |

| Problem and solution cards | To apply mindfulness techniques to work with sensations (ice) |

| To apply the principle of BRAIN to make informed decisions | |

| Session 7 | Learning Objectives |

| The journey of pregnancy and birth: Breastfeeding and newborn needs | |

| Lake meditation | Apply knowledge of newborn needs to problem solve how to respond to baby crying |

| Labor problem and solution cards | Understanding the risk factors of postnatal depression |

| Breastfeeding problem and solutions cards | Able to describe the benefits of breastfeeding |

| Mindful parenting | Understands some of the common difficulties experienced when starting breastfeeding and how to overcome them |

| Newborn needs | Ability to use mindfulness techniques to respond openly and compassionately to your baby’s needs |

| Postnatal depression | |

| Session 8 | Learning Objectives |

| The journey of pregnancy and birth: Mindful parenting | |

| Lake meditation | Understanding how to integrate mindfulness practice into daily life and life after birth |

| Walking meditation | Describe and list what services are accessible for new parents. |

| Priorities activity | Assess and analyze the challenges that lay ahead as new parents. |

| Taking a stand activity | |

| Responsibilities activity | |

| Dealing with postpartum life activities |

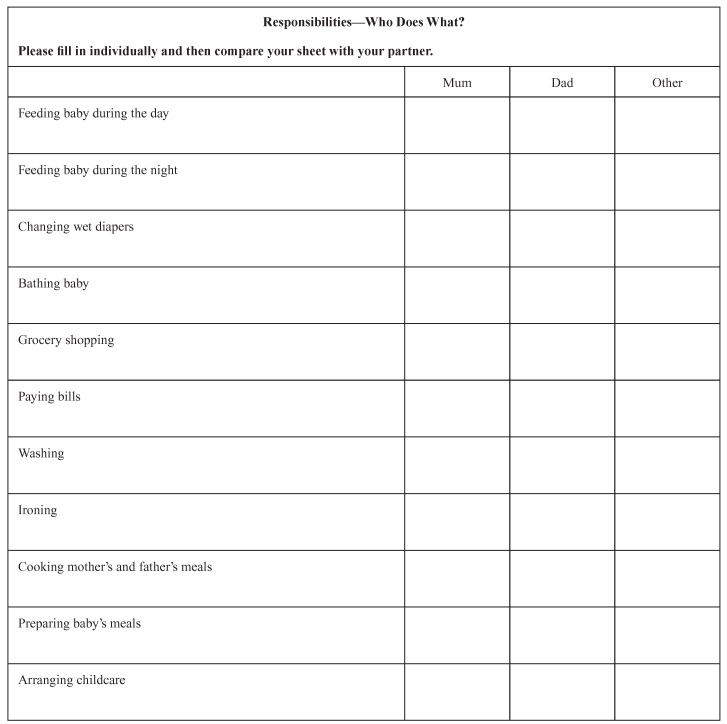

Within the education component, expectant parents were offered evidence-based information to enable informed choice in relation to pregnancy, birth, and early parenting decisions. A range of learning activities including group discussion, role play, and problem-solving activities were employed. Two examples of worksheets to encourage discussion between the woman and her partner are provided in Figures 1 and 2. Mindfulness exercises and specific meditations such as the lake, walking, and mountain meditations were taught to develop nonreactive, present-moment awareness. The application of mindfulness to situations of discomfort during pregnancy, labor, and early parenting were also reinforced.

Figure 1.

Parent worksheet around priorities.

Figure 2.

Parent worksheet around responsibilities.

EVALUATION OF THE MINDFULNESS-BASED CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION PROGRAM

A small pilot study was conducted in 2010 of the MBCE program with data from 12 pregnant women revealing significant improvements in childbirth self-efficacy and reduction in childbirth fear (Byrne et al., 2014). Results confirmed that women felt more confident in their ability to cope, were less fearful of birth, and had an increased expectations for a positive birth. Although not significant, there was a trend toward an increase in mindfulness by the end of the MBCE program (p = .058). The mean meditation time of 64 minutes per week, which ideally should be an hour per day, suggests a low dose of mindfulness was received. There were no significant changes in depression, anxiety, stress or PND scores for the 12 participants over the period of the program (Byrne et al., 2014).

A further qualitative study was conducted 4 months following completion of the MBCE program with two focus groups: 12 mothers and 7 partners (Fisher, Hauck, Bayes, & Byrne, 2012). Empowerment and a sense of community explained the essence of the experiences of both groups and infiltrated the key themes of “awakening my existing potential” and “being in a community of like-minded parents.” The MBCE program was perceived to facilitate parents’ sense of control and involvement in decisions during birth. The pedagogical approach was seen to foster a sense of community among the parents who created their own Facebook group and mothers group that extended into the postpartum period (Fisher et al., 2012).

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Today’s parents expect choice and variety in the content and presentation format of childbirth education offerings so they can select the type of education they feel will meet their individual needs. Parents also expect that health care is providing evidence-based services regardless of the model of education offered. Parents want to be able to make an informed choice from various offerings and are often willing to pay for a desirable service that is tailored to their needs. Of Australian women who gave birth in hospitals in 2011, the state of Western Australia had the highest proportion (40.9%) attending private hospitals (Li, Zeki, Hilder, & Sullivan, 2013). The Australian government promotes private health insurance by imposing a Medicare levy surcharge on high-income families without private hospital cover (Australian Government Medicare Levy Surcharge, 2013). Within the private hospital sector, women and their partners pay for childbirth education sessions. At this time, the public sector provides education at no cost; however, parents are still able to engage with education sessions offered through nongovernment family centers, yoga centers, and private companies.

Current educational offerings may result in a disinterest by some parents in attending classes (Martin et al., 2013), and classes that are attended may not be giving prospective parents the skills they need for birth and early parenting. Because there is no current evidence base for a recognized beneficial model of childbirth education, giving consumers various models to choose from may go some way to meeting their needs. Further international research into what elements parents believe should be included in childbirth education is warranted. For example, a recent Danish study confirmed that parents wanted couple relationship topics integrated into antenatal education (Axelsen, Brixval, Due, & Koushede, 2014). Although this topic can be included in different models of childbirth education, how the topic is embedded within the principles of adult learning requires further exploration and evaluation from parents.

The small number of international pilot studies that have evaluated programs incorporating mindfulness within childbirth education have produced promising results (Byrne et al., 2014; Duncan & Bardacke, 2009; Woolhouse et al., 2014). However, this model may not be suitable for many women as mindfulness-based education requires commitment and motivation because of the practice requirements. A “one-size-fits-all” approach to education will not address the diverse learning needs of parents who want options to select a childbirth education program they feel is suitable and tailored to their individual needs. In fact, these preliminary studies targeted educated and highly motivated women reflecting a potential market for ensuring the suite of educational offerings does include a mindfulness component. Growing awareness of mindfulness with the release of the Mind the Bump app in Australia could contribute to an increased awareness and demand in the future for models incorporating a mindfulness approach.

A “one-size-fits-all” approach to education will not address the diverse learning needs of parents who want options to select a childbirth education program they feel is suitable and tailored to their individual needs.

CONCLUSION

Historical and current evidence around childbirth education including the introduction of mindfulness to parent education was discussed; however, the aim of this article was to describe the rationale for incorporating adult and experiential learning with MBSR in a childbirth education program. The curriculum and learning objectives for this 8-week MBCE program was also presented. Having evidence-based options and informed choice is an expectation of parents, and the partnership between childbirth education and mindfulness contributes to an increasing variety and richness of educational offerings available to expectant parents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the parents who attended our Mindfulness-Based Childbirth Education program and graciously and honestly shared their experiences of the program.

Biographies

YVONNE HAUCK is the professor of midwifery in the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedicine at Curtin University in Western Australia.

COLLEEN FISHER is the professor of teaching and research in the School of Population Health at the University of Western Australia.

JEAN BYRNE is an honorary research fellow at Curtin University in Western Australia. She is also a qualified childbirth educator, specialist antenatal yoga teacher, and mindfulness meditation teacher.

SARA BAYES is a senior lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia.

REFERENCES

- Ahldén I., Ahlehagen S., Dahlgren L., & Josefsson A. (2012). A parent’s expectations about participating in antenatal parenthood education classes. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 21(1), 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S., & Guthery A. (2015). Mindfulness-based psychoeducation for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: An applied clinical project. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(1), 43–49. 10.1111/jcap.12103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Medicare Levy Surcharge. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.privatehealth.gov.au/healthinsurance/incentivessurcharges/mls.htm

- Axelsen S., Brixval C., Due P., & Koushede V. (2014). Integrating couple relationship education in antenatal education—A study of perceived relevance among expectant Danish parents. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 5, 174–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brixval C., Axelsen S., Andersen S., Due P., & Koushede V. (2014). The effect of antenatal education in small classes on obstetric and psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Systematic Reviews, 3, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugha T., Wheatley S., Taub N., Culverwell A., Friedman T., Kirwan P., . . . Shapiro D. (2000). Pragmatic randomized trial of antenatal intervention to prevent postnatal depression by reducing psychosocial risk factors. Psychological Medicine, 30(6), 1273–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buultjens M., Robinson P., & Milgrom J. (2012). Online resources for new mothers: Opportunities and challenges for perinatal health professionals. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 21(2), 99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne J., Hauck Y., Fisher C., Bayes S., & Schutze R. (2014). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based childbirth education pilot study on maternal self-efficacy and fear of childbirth. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 59(2), 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth J., Duncan L., Nix R., Greenberg M., Gayles J., Bamberger K., . . . Demi M. (2015). Integrating mindfulness with parent training: Effects of the mindfulness-enhanced strengthening families program. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L., & Bardacke N. (2009). Mindfulness-based childbirth education parenting education: Promoting family mindfulness during the perinatal period. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 190–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian H., Rådestad I., & Waldenström U. (2005). Childbirth and parenthood education classes in Sweden: women’s opinion and possible outcomes. Acta Obsetericia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 84, 436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C., Hauck Y., Bayes S., & Byrne J. (2012). Participant experiences of mindfulness-based childbirth education: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A., & Sandall J. (2007). Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), 10.1002/14651858.CD002869.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord S., Palsson O., Garland E., Faurot K., Coble R., Mann J., . . . Whitehead W. (2011). Mindfulness training reduces the severity of irritable bowel syndrome in women: results of a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 106, 1678–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P., Kappos L., Gensicke H., D’Souza M., Mohr D., Penner I., & Steiner C. (2010). MS quality of life, depression, and fatigue improve after mindfulness training: A randomized trial. Neurology, 75, 1141–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins Martin C., & Robb Y. (2013). Women’s views about the importance of education in preparation for childbirth. Nurse Education in Practice, 13, 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling B. (2013). The nocebo effect in childbirth classes. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 22(2), 120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet R., & Corry M. (2010). Steps toward innovative childbirth education: Selected strategies form the Blueprint for Action. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 19(3), 17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Piatkus. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman T. (2007). Evolution of the birth plan. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 16, 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehn M. (2002). Childbirth education outcomes: An integrative review of the literature. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 11, 10–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Zeki R., Hilder L., & Sullivan E. (2013). Australia’s mothers and babies 2011. Canberra, Australia: Australia Institute of Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Martin D., Bulmer S., & Pettker C. (2013). Childbirth expectations and sources of information among low- and moderate-income nulliparous pregnant women. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 22(2), 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mind the Bump. (2014). Mobile phone application developed by Beyond Blue and Smiling Mind. Retrieved from http://www.mindthebump.org.au/?gclid=CIfV5pHZjcQCFdcRvQodZSMAIg

- Morone N., Greco C., & Weiner D. (2008). Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomised controlled pilot study. Pain, 134, 310–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2008). Postnatal depression (reissued ed.). Canberra, Australia: Author; Retrieved from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/wh29-wh30 [Google Scholar]

- Nolan M., Mason V., Snow S., Messenger W., Catling J., & Upton P. (2012). Making friends at antenatal classes: A qualitative exploration of friendship across the transition to motherhood. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 21(3), 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor T., Heron J., Golding J., Beveridge M., & Glover V. (2002). Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan M., McElroy K., & Moore K. (2013). Choice? Factors that influence women’s decision making for childbirth. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 22(3), 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiger K. (2001). Our bodies, our babies: The forgotten women’s movement. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Remer M. (2012). Incorporating prenatal yoga into childbirth education classes. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 27(2), 92–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkert S., & Nutbeam D. (2001). Opportunities to improve maternal health literacy through antenatal education: An exploratory study. Health Promotion International, 16(4), 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. (1976). Maternal tasks in pregnancy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1(5), 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S., Grossman P., Schwarzer B., Jena S., Naumann J., & Walach H. (2011). Treating fibromyalgia with mindfulness-based stress reduction: Results from a 3-armed randomized controlled trial. Pain, 152, 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z., Williams J., & Teasdale J. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair M. (2013). Looking through the research lens at the challenges facing midwives delivering evidence-informed antenatal education. Evidence Based Midwifery, 11(4), 111. [Google Scholar]

- Speca M., Carlson L., Goodey E., & Angen M. (2000). A randomized, wait-listed controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(5), 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiby H., Slade P., Escott D., Henderson B., & Fraser R. (2003). Selected coping strategies in labor: An investigation of women’s experiences. Birth, 30, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Barclay L., & Cooke M. (2006). The concerns and interests of expectant and new parents: Assessing learning needs. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 15(4), 18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Barclay L., & Cooke M. (2008). Effective antenatal education: Strategies recommended by expectant and new parents. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 17(4), 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Barclay L., & Cooke M. (2009). Randomised-controlled trial of two antenatal education programmes. Midwifery, 25, 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talge N., Neal C., & Glover V. (2007). Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: How and why? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3–4), 245–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh B., Mulder E., Mennes M., & Glover V. (2005). Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioral development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review, 29(2), 237–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. S., Visger J. M., & Rossie D. (2009). Contemporary childbirth education models. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54(6), 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. (2002). A family resilience framework: Innovative practice applications. Family Relations, 51(2), 130–145. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse H., Mercuri K., Judd F., & Brown S. (2014). Antenatal mindfulness intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and stress: A pilot randomised controlled trial of the MindBabyBody program in an Australian tertiary maternity hospital. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D. (2010). Childbirth education, the internet and reality television: Challenges ahead. Birth, 37(2), 87–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N. (2013). Improving childbirth practice for adult parents-to-be. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 28(2), 25–29. [Google Scholar]