Abstract

Twelve 1,5-disubtituted and fourteen 5-substituted 1,2,3-triazole derivatives bearing diaryl or dialkyl phosphines at the 5-position were synthesized and used as ligands for palladium-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions. Bulky substrates were tested, and lead-like product formation was demonstrated. The online tool SambVca2.0 was used to assess steric parameters of ligands and preliminary buried volume determination using XRD-obtained data in a small number of cases proved to be informative. Two modeling approaches were compared for the determination of the buried volume of ligands where XRD data was not available. An approach with imposed steric restrictions was found to be superior in leading to buried volume determinations that closely correlate with observed reaction conversions. The online tool LLAMA was used to determine lead-likeness of potential Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling products, from which 10 of the most lead-like were successfully synthesized. Thus, confirming these readily accessible triazole-containing phosphines as highly suitable ligands for reaction screening and optimization in drug discovery campaigns.

Introduction

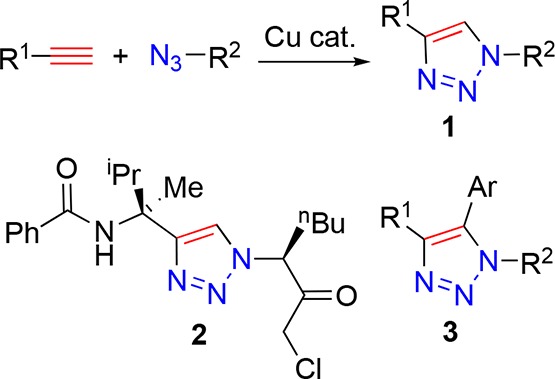

Click chemistry, as defined by Sharpless and co-workers,1−4 has transformed the face, and accessibility to the nonspecialist of molecular linking strategies. Among click approaches, the highly regioselective copper-catalyzed, Huisgen cycloaddition reaction to form 1,4-triazoles (Figure 1, 1) by Meldal and Sharpless,4,5 has grown in popularity and has been employed in increasingly varied applications over the intervening years.6 The copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) is ubiquitous,5,7−9 and often referred to as “the click reaction”, and the product 1,2,3-triazoles, bearing 1,4-substition patterns, with reliable fidelity and yields being synonymous with click chemistry (Figure 1, 1).8,10−15 However, the resulting triazoles are not always employed as innocent bystander linkage motifs. Triazoles of this type have been used as analogues of peptide linkages (Figure 1, 2),16 such peptidomimetics are physiologically stable, and their modular synthesis allows access to a broad range of biologically relevant applications.17,18 The utility of further synthetic transformations has been probed, particularly in the derivatization at the 5-position (Figure 1, 3).19,20

Figure 1.

Upper: copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). Lower: examples of 1,2,3-triazole-containing structures.

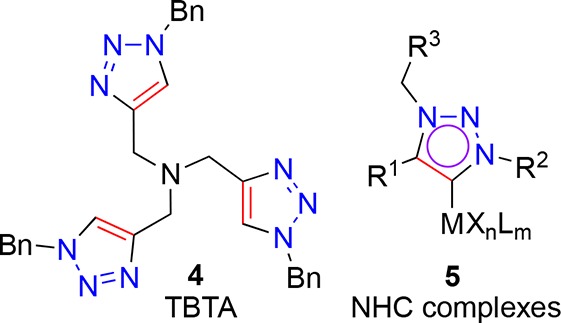

Copper-catalyzed triazole formation has been exploited in a wide range of scenarios21 and has been the subject of various mechanistic studies,22−26 leading to the proposal of a binuclear transition state involving two copper atoms. 1,2,3-Triazole derivatives have been employed as nitrogen-coordinating ligands,27 e.g. in N,N′-,28−34 N,S-,29 N,Se-29 and cyclometalated35−37 bidentate coordination complexes. Furthermore, tris-triazoles, such as TBTA (Figure 2, 4) and its analogues, have been used as ligands for reactions including the CuAAC by both Fokin38 and Zhu39 and their co-workers, demonstrating exceptional ligand-mediated reaction acceleration.

Figure 2.

Examples of triazole-containing or -derived ligands.

Alkylation of a 1,2,3-triazole derivative, to furnish a 1,3,4-trisubstituted triazolium salt, is the first step in the synthesis of a newer class of N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) reported in 2008 by Albrecht and co-workers40 and later extended by Lee and Crowley41−43 as ligands for gold and by Grubbs and Bertrand as ligands for ruthenium-mediated catalysis (Figure 2, 5).44 The ready access to a range of ligand scaffolds through the CuAAC has led the triazole–NHC platform to continue to gain in popularity.45−49 These reports demonstrate the 1,2,3-triazole unit is a legitimate candidate for further exploitation as a key component in ligand design and catalyst development.50

The co-authors of this report have investigated triazoles as chemosensors51−53 and as products of asymmetric synthesis.54−58 Furthermore, an interest in boronic acid derivatives as chemosensors,59−64 including the use of cross-coupling reactions as a means of sensing,65 means the co-authors of this report are familiar with boronic acids and esters.66 As such, a desire to bring together these streams of research under one umbrella has led to the research reported in this manuscript. Herein, the development of bulky and highly active triazole-containing phosphine ligands for palladium-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions is explored (Scheme 1).

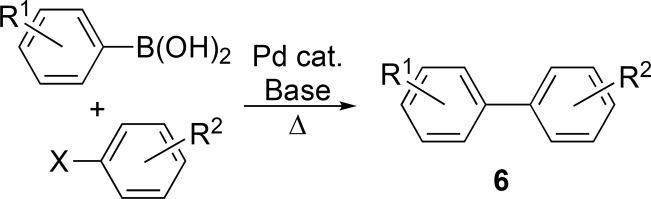

Scheme 1. Outline of a General Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Formation of Biaryl 6.

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions are well-studied and offer ready access to an extensive range of (bi)aryl motifs (Scheme 1, 6).67−76 The suite of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling chemistry available for the construction of biologically relevant products has transformed the field of medicinal chemistry, yet cross-coupling between sterically hindered and lead-like building blocks, particularly with aryl chlorides, remains challenging.77

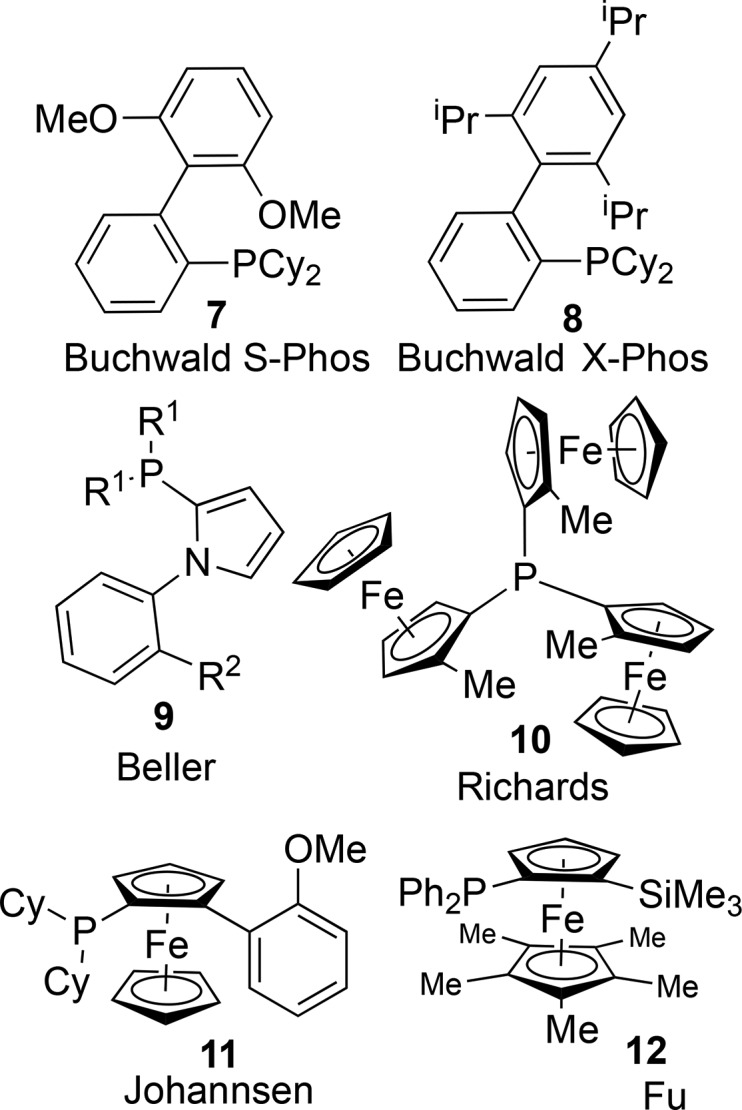

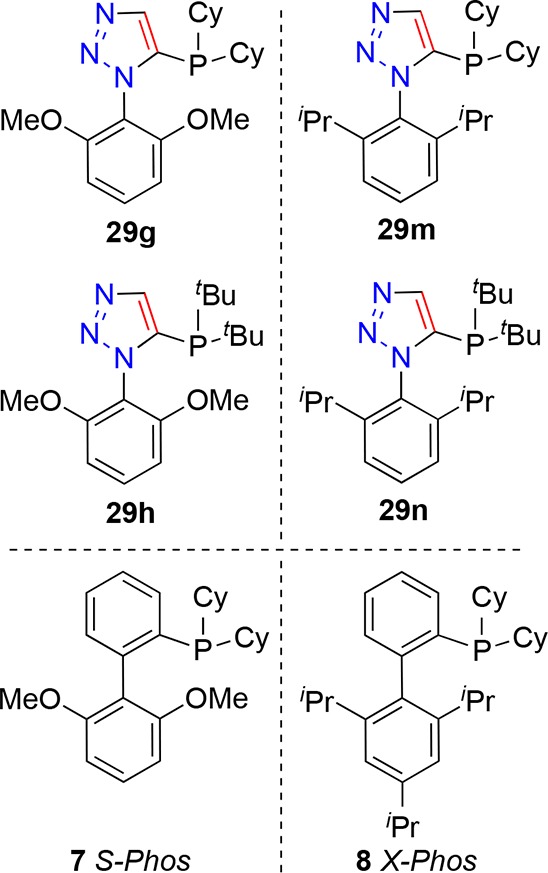

Developments in palladium-catalyzed chemistry have been heavily influenced by ligand design and optimization. Among the superior ligands for palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions are bulky alkyl phosphines,78−82 and bulky ortho-substituted aryl-alkyl phosphines,83,84 such as S-Phos (Figure 3, 7)85 and X-Phos (Figure 3, 8).86 Metallocyclic precatalysts have been developed which delivered greater stability, more facile manipulation and enhanced reaction outcomes.87−89

Figure 3.

Representative examples of bulky phosphine ligands including: upper: S-Phos (7) and X-Phos (8); middle left: heteroaromatic phosphine derivative (9); middle right and lower row: Phosphino-ferrocene derivatives displaying planar chirality.

Phosphines appended to one or more five-membered, all sp2 rings have been shown to offer advantages in some cases. The pyrrole-appended phosphines of Beller and co-workers (Figure 3, 9)90,91 have proven to be useful ligands in cross-coupling catalysis that furnishes drug-like products. Furthermore, the bulky, electron-rich, ferrocene-appended phosphines of Richards (Figure 3, 10),92 Johannsen (Figure 3, 11),93 Fu (Figure 3, 12),94 and their respective co-workers provide access to highly active palladium-ligand conjugates for cross-coupling some of the least active substrates.

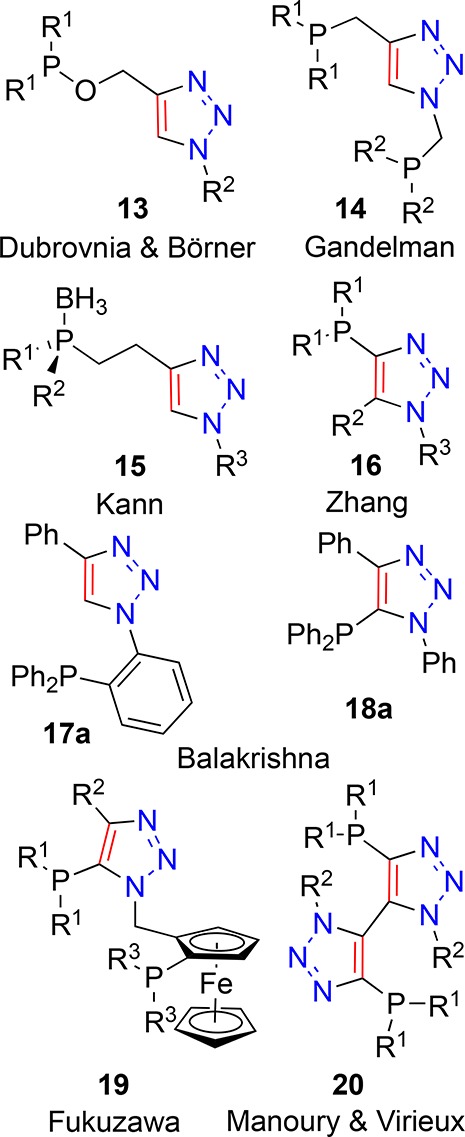

1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-triazoles have been used in the assembly of phosphorus-containing species that have the potential to be employed as ligands. Ready access to libraries of products using CuAAC reactions has permitted the development of phosphines connected to triazoles with sp3 linkages to the 1-N and 4-C positions. Examples include those reported by Dubrovnia, Börner and co-workers (Figure 4, 13),95 Gandelman and co-workers who prepared PCP′ pincer complexes from bis-phosphinotriazoles (Figure 4, 14),96 and Kann and co-workers who used a borane-protected P-chiral azide to deliver protected P-chiral triazole-containing phosphines (Figure 4, 15).97 Since proximal stoichiometric phosphine can arrest the CuAAC through coordinative saturation of substoichiometic copper catalyst or unwanted Staudinger-type reactions between phosphine and azide derivative, alternative approaches are required to deliver P-appended triazoles. Zhang and co-workers reported on the use of alkynyl Grignard reagents for the synthesis of a phosphine series where phosphorus is attached directly to a 1,2,3-triazole ring at the 4-position (Figure 4, 16).98−101 As part of an impressive, rigorous, and detailed study, Balakrishna and co-workers prepared not only expected aryl phosphine triazole derivative 17a (Figure 4) through lithium-halogen exchange and subsequent reaction with diphenylphosphorus chloride on the corresponding bromide under kinetic control but also thermodynamically favored 5-phosphino triazole 18a (Figure 4) from the same aryl bromide starting material under different conditions.102 Fukuzawa and co-workers also employed deprotonation of the 5-position of a 1,2,3-triazole to facilitate installation of 5-phosphino functionality in their ferroncenyl bisphosphino ligand synthesis (Figure 4, 19).103 Glover et al.104 and Austeri et al.105 also utilized deprotonation of the triazole 5-position to create planar chiral cyclophane-containing analogues of 18a. In order to successfully synthesize a bis-5-phosphino-triazole bidentate ligand, Manoury, Virieux, and co-workers employed an ethynyl phosphine oxide in their homocoupled dimer synthesis, which after treatment with trichlorosilane resulted in 20 (Figure 4).106 A structurally related 5–18 hybrid system was also recently reported by Cao et al., who showed the formation of bimetallic complexes of NHC–phosphine mixed systems.107

Figure 4.

Phosphorus-containing 1,2,3-triazole derivatives.

Bulky, or sterically hindered, phosphorus-containing ligands have also found application outside of the palladium catalysis arena; steric parameters appear to be important in a variety of gold-mediated transformations.108−110 Steric and electronic parameters of phosphine ligands have been a subject of study for more than 40 years.111 More recent contributions have built upon Tolman’s concept of cone angle as a descriptor of the steric bulk a ligand imparts about a metal, resulting in a parameter known as buried volume (%VBur) coming to the fore.112 Cavallo and co-workers have developed a free web-based tool for the calculation of %VBur, named SambVca.113 This parametrization of ligands, using both spectroscopic measurements and calculated properties (using principle component analysis for example), has facilitated exceptional ligand design and optimization across a range of catalyzed reactions.114−116

While a range of ligand-based solutions for cross-coupling reactions exist, a platform to rapidly deliver alternatives and explore chemical space around novel catalyst constructs, such as through CuAAC, offers approaches and complementary tools to the field. Furthermore, cross-coupling catalysis manifolds that provide access to increasingly three-dimensional products,117 and those directly delivering products with lead- or drug-like properties118 without need of protecting group removal or further derivatization are desired and less-well explored.77

Results and Discussion

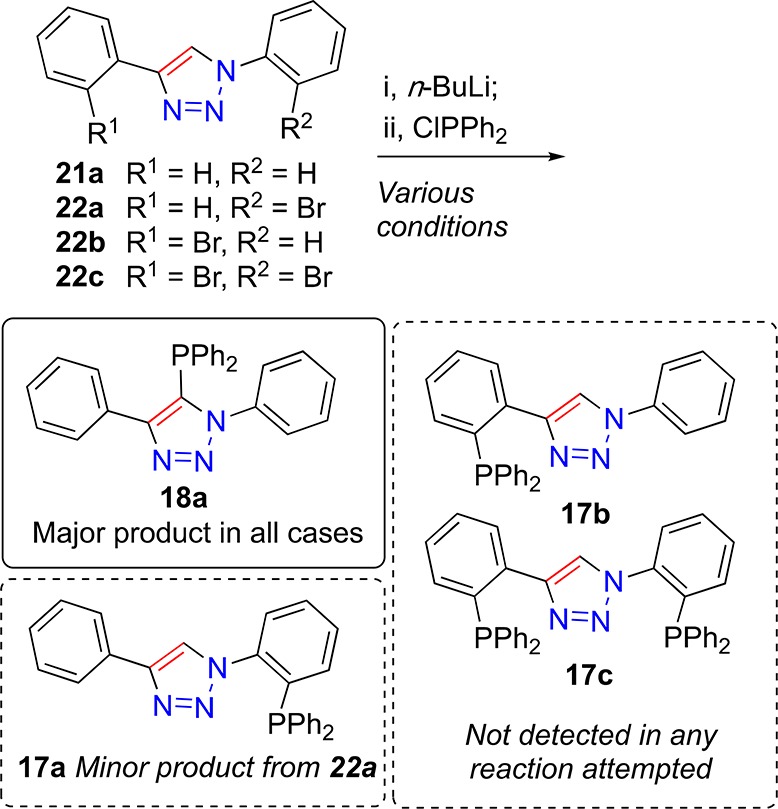

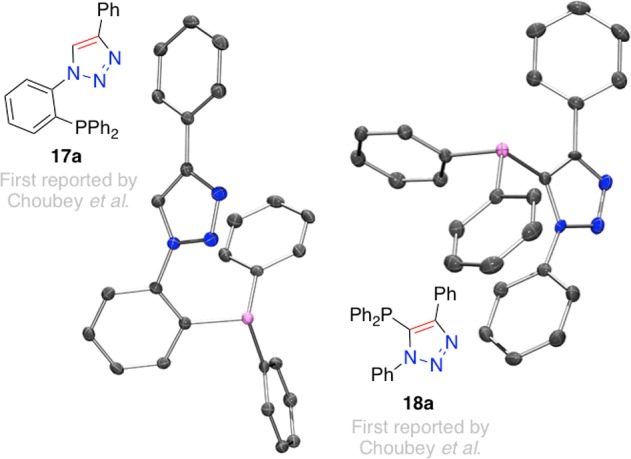

In order to overcome the general incompatibility of phosphines with the CuAAC reaction, an approach other than direct phosphine incorporation is required. While protection of the phosphine (as a phosphine oxide for example)106 is possible, the initial approach chosen in this program was to probe the potential for triazole-mediated directed ortho-lithiation or halogen-lithium exchange, and subsequent reaction with diphenyl phosphorus chloride, as possible routes to phosphino-triazoles 17a–c. Accordingly, 1,4-diphenyl-1,2,3-triazole (21a) was selected as a model substrate to test if ortho-lithiation could deliver the required intermediate to give the desired product 17a. As such, 21a was reacted at −78 °C with n-butyllithium, followed by addition of the phosphorus chloride reagent, before being allowed to warm to room temperature, and being allowed to stir for a period of time. Over numerous attempts only the unanticipated product 18a was isolated from such reactions, Scheme 2. This indicates that deprotonation of the 5-position of the triazole is facile, resulting in formation of the observed major product. In order to mitigate against the formation of unanticipated triazole-phosphine 18a, brominated triazole derivatives 22a–c were employed under a similar protocol, with varying amounts of n-butyllithium. In all cases, the same 5-phosphino-triazole product, 18a, was obtained, shown in Scheme 2. In the case of 22a, it was possible to isolate small quantities of the desired product 17a. X-ray crystal structures of both 17a and 18a were determined as shown in Figure 5.

Scheme 2. Reaction of 1,2,3-Triazoles 21a–d with n-Butyllithium Followed by Treatment with Diphenyl Phosphorous Chloride Led Primarily to Formation of Phosphino-Triazole 18a.

Figure 5.

Representation of the crystal structures of isomeric 17a (left) and 18a (right), ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level (Ortep3 for Windows and PovRay). For 17a the structure contains two crystallographically independent molecules with only one shown for clarity. For 18a the phenyl-appended 1-nitrogen and 4-carbon atoms of the triazole unit are disordered such that the triazole ring occupies two opposing orientations, related by a 180° rotation of the triazole ring about the phosphorus-triazole bond. The refined percentage occupancy ratio of the two positions are 59.7 (15) and 40.3 (15); one arbitrary molecule depicted and hydrogen atoms removed for clarity.

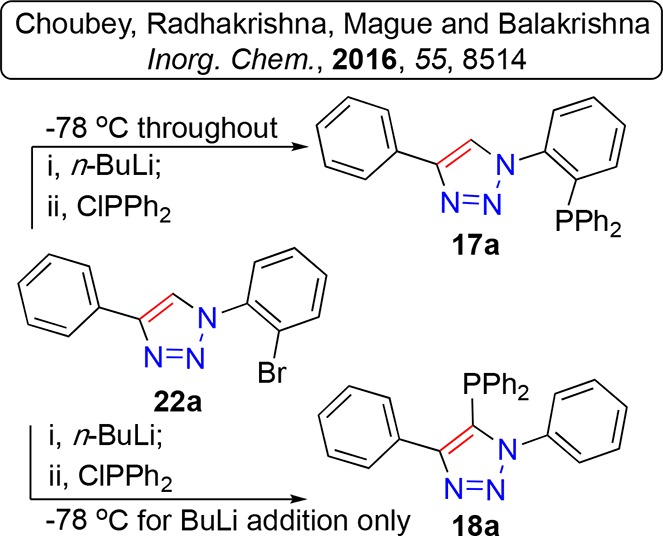

In fact these observations should not have been at all unanticipated.102,104 The aforementioned report of Balakrishna and co-workers had previously probed the reaction of 17a in more detail than us under analogous conditions102 and determined a “kinetic” and “thermodynamic” relationship between lithium-halogen exchange alone, versus lithium-halogen exchange followed by lithium (triazole-) proton exchange leading to products 17a and 18a respectively, Scheme 3.

Scheme 3. Previously Reported Kinetic (Upper) and Thermodynamic (Lower) Lithiation and Subsequent Phosphorous Addition to Brominated Triazole 22a Affording P-Aryl and P-Triazole Derivatives, Respectively.

Ref (102).

Attempts to block the triazole 5-H position, using the deuterium masking approach deployed by Richards and co-workers in the preparation of ferrocene derivatives,119 did not dramatically modify reaction outcomes in our hands. Variously deuterated products were always obtained from attempted lithiation-mediated access to products under routine conditions.

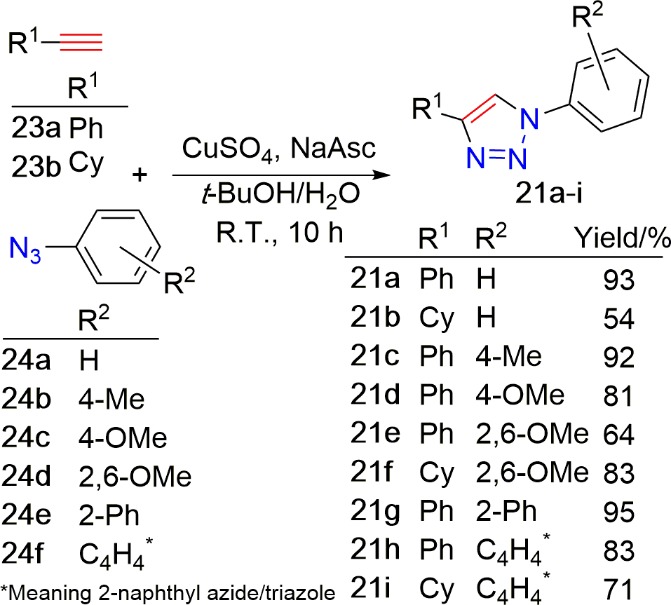

Since the scope of 18a-like ligands had not been investigated beyond the three triazole backbones reported by Glover et al.104 and Choubey et al.,102 we chose to focus attention on triazole 5-H lithiation to deliver a range of potential ligands for cross-coupling catalysis. To this end, alkynes 23a and 23b reacted smoothly with azides 24a–f to furnish 1,5-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles 21a–i in acceptable to good yields, shown in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4. CuAAC Reaction to Form 1,4-Disubstituted 1,2,3-Triazole Derivatives 21a–i.

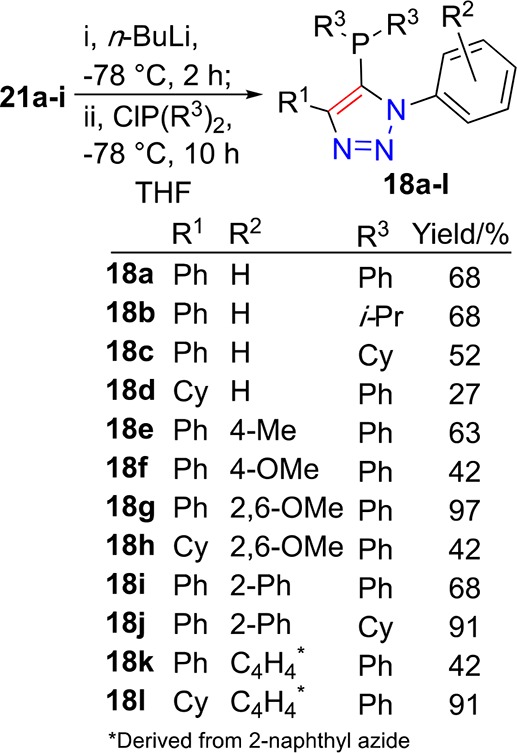

Applying the aforementioned triazole lithiation and subsequent quench with dicyclohexyl-, di-iso-propyl-, or diphenyl- phosphorus chloride reagent protocol to isolated 21a–i triazole set, with the express expectation of generating 5-phosphino triazole derivatives, delivered 12 targeted phosphino-triazoles 18a–l in acceptable to good yields (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Deprotonation and Subsequent Reaction with Phosphorous Chloride Reagent Protocol for Delivery of 18a–l.

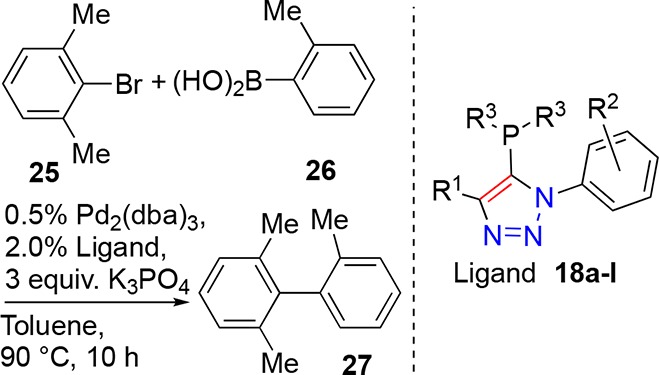

In order to benchmark the catalytic capability of ligands in this report, the palladium-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura reaction of 2-bromo-m-xylene (25) and ortho-tolylboronic acid (26) under standard conditions (1 mol % palladium, 2 mol % ligand, three equivalents of base, 10 h, toluene, 90 °C, see the Supporting Information) was compared. The catalyzed formation of compound 27 represents a challenging but achievable cross-coupling: While an aryl bromide is employed in the reaction, the product (a triply ortho-substituted biaryl) is sterically congested about the formed bond. Diphenyl aryl phosphine 17a and 5-phosphino triazoles 18a–l were employed as ligands in the benchmark reaction (Table 1). The use of 17a as ligand (Table 1, entry 1) resulted in 29% conversion to product 27. The 5-phosphino isomer of 17a, 18a, also gave less than 50% conversion to desired product 27 in the same reaction (Table 1, entry 2). As may be expected, switching the diphenylphosphine part of 18a to dialkylphosphine groups di-iso-propyl (18b) and dicyclohexyl (18c) improved the reaction outcomes, resulting in 62 and 75% conversion, respectively (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). Changing the alkyne-derived part of the triazole from phenyl (18a) to cyclohexyl (18d) gave a marked improvement delivering product 27 in 86% conversion (Table 1, entry 2 versus 5).

Table 1. Ligand Screening: 1,4-Disubstituted 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing Phosphine Ligand Mediate, Palladium-Catalyzed, Formation of 27a.

| entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | ligand | conversion [%]b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17a | 29 | |||

| 2 | Ph | H | Ph | 18a | 47 |

| 3 | Ph | H | i-Pr | 18b | 62 |

| 4 | Ph | H | Cy | 18c | 75 |

| 5 | Cy | H | Ph | 18d | 86 |

| 6 | Ph | 4-Me | Ph | 18e | 69 |

| 7 | Ph | 4-OMe | Ph | 18f | 83 |

| 8 | Ph | 2,6-OMe | Ph | 18g | 92 |

| 9 | Cy | 2,6-OMe | Ph | 18h | 90 |

| 10 | Ph | 2-Ph | Ph | 18i | 84 |

| 11 | Ph | 2-Ph | Cy | 18j | 92 |

| 12 | Ph | 2-Napthe | Ph | 18k | 91 |

| 13 | Cy | 2-Napthe | Ph | 18l | 99 |

Reaction conditions: 2-bromo-m-xylene (0.4 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (0.6 mmol), potassium phosphate (1.2 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (0.5 mol %), ligand (2 mol %), toluene (3 mL), 10 h, 90 °C.

Conversion determined by inspection of the corresponding 1H NMR spectra of crude reaction isolates. See the Supporting Information for details.

Meaning derived from naphthyl azide.

While good results were obtained in the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions with 18-derived catalysts the more effective ligands (generally larger) suffered somewhat from poor solubility. Thus, ligand modifications that retained activity but allowed for more ready synthesis and manipulation at larger scale were sought. From briefly surveying the results in Table 1 it was concluded that changes in the R1 (alkyne-derived) part (e.g., entry 8 versus entry 9) were less influential on the reaction outcome than changes in the R2 (azide-derived) part (e.g., entry 5 versus entry 13). Reasoning that smaller ligands may benefit from enhanced solubility and tractability, a strategy to retain the N-substituents (azide-derived parts) while minimizing the alkyne-derived parts was chosen for further elaboration. Gevorgyan and co-workers have already reported that 1,5-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles may be accessed by selective reaction at the 5-position of 1-substituted triazoles (Figure 6 shows the electrostatic potentials of the triazole-carbons they determined), and coupled with the synthetic strategies reported by Oki et al.103 for chiral bisphosphine synthesis, this led to the conclusion that 1-substitutued triazoles may be readily converted to a library of 1-substituted, 5-phosphino 1,2,3-triazoles

Figure 6.

Electrostatic potential charges as determined by Gevorgyan and co-workers,19 indicates rationale for selective C-5 deprotonation.

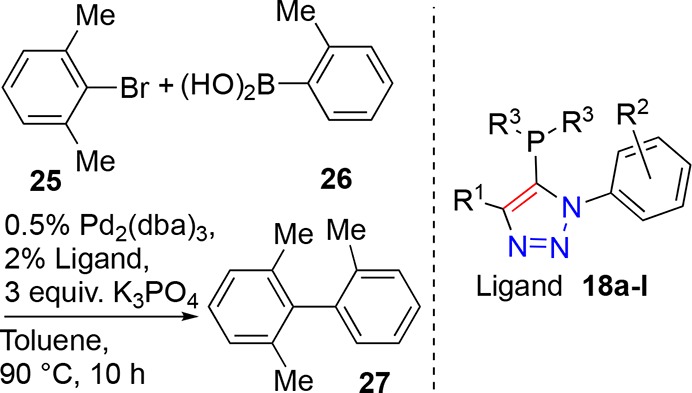

Following the optimized protocol of Oki et al.103 deployed in the synthesis of more complex constructs, a range of 1-substituted triazoles were synthesized. Specifically, trimethylsilylacetylene (23c) and aryl azides (24a–i) were exposed to CuAAC reaction conditions (Scheme 6) that led to effective triazole formation and desilylation in one pot. Acceptable to good yields of 1-substituted triazoles 28a–i were isolated after 24 h room temperature reactions.

Scheme 6. Trimethylsilylacetylene (23c) and Aryl Azides (24a–i) React under Desilylative CuAAC Reaction Conditions to Deliver 1-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazoles (28a–i).

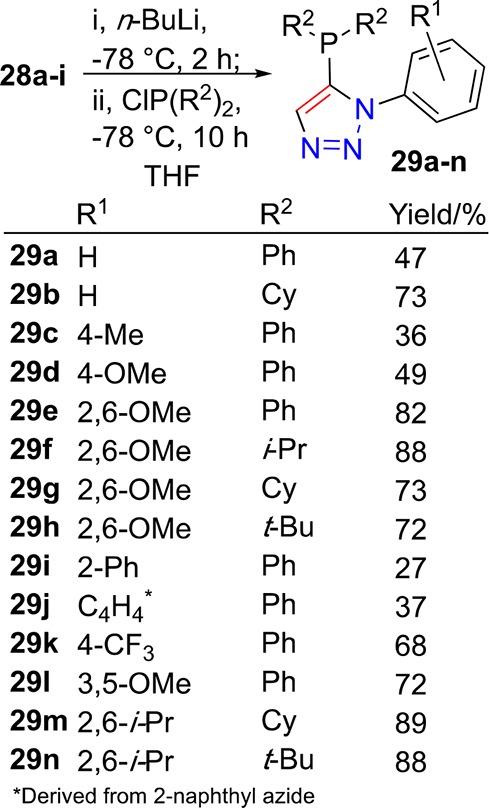

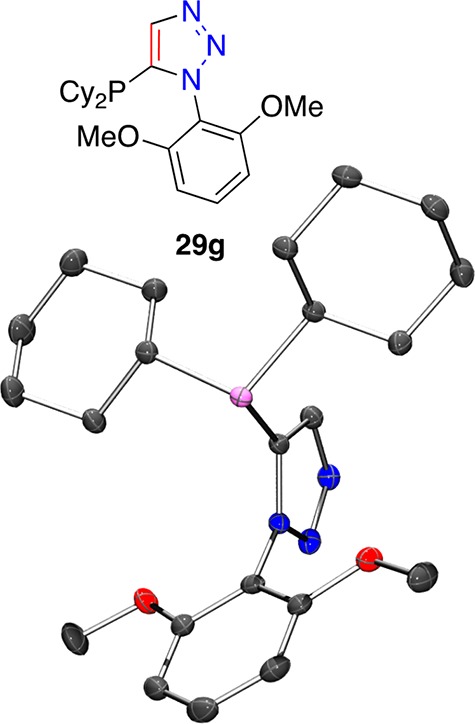

Triazoles 28a–i reacted smoothly under the deprotonation and phosphorus chloride reagent quench reaction conditions described earlier. Deprotonation at −78 °C, by treatment with n-butyllithium, followed by addition of dicyclohexyl-, di-iso-propyl-, di-tert-butyl- or diphenyl-phosphorus chloride at the same temperature (Scheme 7) resulted in formation of the desired triazole-containing phosphines 29a–n in acceptable to good yields. The X-ray crystal structure of 29g was determined (Figure 7); the orientation of the molecule (in the solid state) is such that the lone pair of the phosphine is oriented to the same direction as the 1-aryl substituent of the triazole. In turn, this orientation about a central five-membered ring describes a relatively wide binding pocket for metals with potential for arene-metal interactions alongside primary phosphorus–metal ligation.

Scheme 7. Deprotonation of 1-Aryl 1,2,3-Triazole Derivatices and Subsequent Reaction with Phosphorous Chloride Reagent Protocol for Delivery of 29a–n.

Figure 7.

Representation of the crystal structure of 29g, ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level (Ortep3 for Windows and PovRay), hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity.

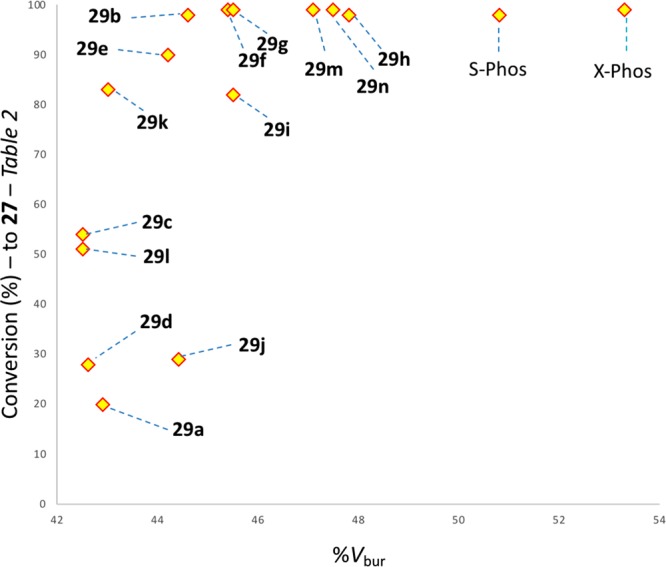

Ligands 29a–n were tested in the aforementioned benchmark Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction of 25 with 26 catalyzed by a palladium–phosphine complex, to produce biaryl 27 (Table 2, entries 1–14). Under the same conditions, commercially sourced ligands, S-Phos (7) and X-Phos (8) were also used for comparison (Table 2, entries 15 and 16, respectively). Diphenyl-phosphino triazole derived ligands failed to deliver product 27 in good yields, under the conditions employed the best conversion for this ligand class was only 54% (ligand 29c, Table 2, entry 3), whereas dialkyl-phosphino triazoles gave universally excellent conversion, equal to the commercially sourced S- and X-Phos in performance, under these conditions.

Table 2. Ligand Screening: 1-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing Phosphine Ligand Mediated, Palladium-Catalyzed, Reaction of Arylbromide 25 in the Formation of 27.

| entry | R1 | R2 | ligand | conversion [%]a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Ph | 29a | 20 |

| 2 | H | Cy | 29b | 98 |

| 3 | 4-Me | Ph | 29c | 54 |

| 4 | 4-OMe | Ph | 29d | 28 |

| 5 | 2,6-OMe | Ph | 29e | 90 |

| 6 | 2,6-OMe | i-Pr | 29f | 99 |

| 7 | 2,6-OMe | Cy | 29g | 99 |

| 8 | 2,6-OMe | t-Bu | 29h | 98 |

| 9 | 2-Ph | Ph | 29i | 82 |

| 10 | C4H4c | Ph | 29j | 29 |

| 11 | 4-CF3 | Ph | 29k | 83 |

| 12 | 3,5-OMe | Ph | 29l | 51 |

| 13 | 2,6-i-Pr | Cy | 29m | 99 |

| 14 | 2,6-i-Pr | t-Bu | 29n | 99 |

| 15 | S-Phos (7) | 98 | ||

| 16 | X-Phos (8) | 99 |

Reaction conditions: 2-bromo-m-xylene (0.4 mmol), o-tolylboronic acid (0.6 mmol), potassium phosphate (1.2 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (0.5 mol %), ligand (2.0 mol %), toluene (3 mL), 10 h, 90 °C.

Conversion determined by inspection of the corresponding 1H NMR spectra of crude reaction isolates. See the Supporting Information for details.

Derived from 2-naphthyl azide.

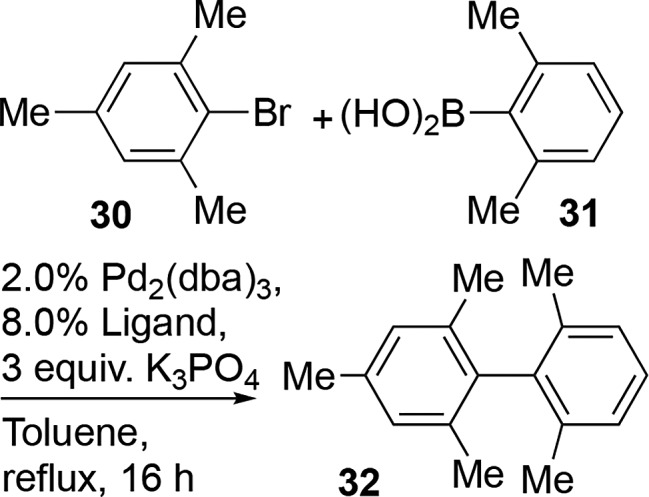

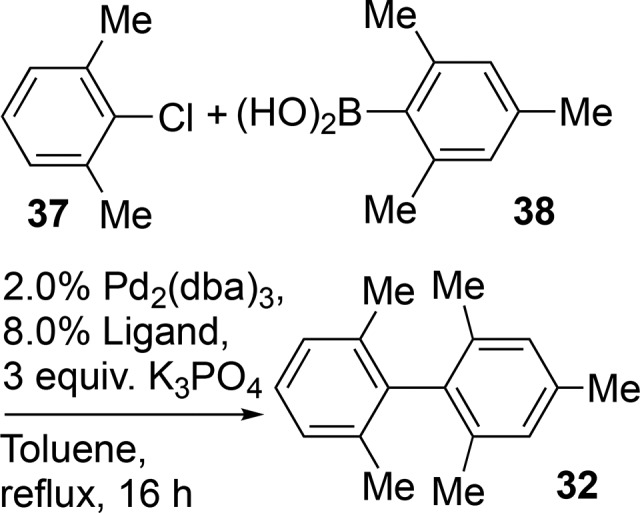

While pleased to have created ligands offering good performance in a benchmark reaction, the reaction itself did not offer enough diversity of outcomes to evaluate dialkyl-phosphino ligand performances against each other nor against readily available commercial ligands 7 and 8. Next, a more sterically demanding test-reaction was chosen to evaluate the ligands further. The formation of biaryl C–C bonds where the formed bond is flanked by four ortho-substituents presents a particularly challenging yet attractive transformation, not in the least due to the apparent three-dimensional nature of the cross-coupled products.117 The reaction of bromide 30 with boronic acid 31 was selected as one such reaction to probe catalyst effectiveness (Table 3). Conversion to product 32 may be monitored by gas chromatographic analysis, facilitating ready comparison of reactions performed in parallel. Having given quantitative conversions to product 27 (Table 2, entries 7, 8, 13, and 14), and being both relatively easy to synthesize and available in sufficient quantities, ligands 29g, 29h, 29m, and 29n were selected for further investigation. These ligands are triazole-analogues of leading phenylene ligands 7 and 8; thus, in order to probe any specific advantages of triazole-core ligands they were compared directly against S-Phos and X-Phos phenylene ligands. (For retained and compared ligands, see Figure 8.)

Table 3. Ligand Screening: 1-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing Phosphine Ligand Mediated, Palladium-Catalyzed, Reaction of Arylbromide 30 in Formation of 32.

| entry | ligand | conversion [%]a,b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29g | 99 |

| 2 | 29gc | 84 |

| 3 | 29h | 47 |

| 4 | 29m | 60 |

| 5 | 29n | 13 |

| 6 | S-Phos (7) | 87 |

| 7 | X-Phos (8) | 50 |

Reaction conditions: 2-bromomesitylene (0.5 mmol), 2,6-xylylboronic acid (1.0 mmol), potassium phosphate (2 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (2.0 mol %), ligand (8.0 mol %), toluene (3 mL), 18 h, reflux.

Determined by GC analysis with n-dodecane as internal standard.

Pd2(dba)3 (0.5 mol %), ligand (2 mol %).

Figure 8.

In order to ensure good reaction conversions, the catalyst loading, temperature, and reaction time were all increased in comparison to the earlier Suzuki–Miyaura reactions. The standard conditions employed in the comparisons of Table 3 (entries 1 and 3–7) were 4 mol % palladium and 8 mol % ligand in toluene at reflux for 16 h. Under these conditions, cyclohexyl-substituted triazole-containing ligands 29g and 29m gave higher conversions to 32 than did their tert-butyl-substituted analogues 29h and 29n (Table 3, entries 1 and 4 (99 and 60%) versus entries 3 and 5 (47 and 13%), respectively). In this comparison, the use of S-Phos (7) as ligand gave 87% conversion (Table 3, entry 6) and the use of X-Phos (8) as ligand gave 50% conversion (Table 3, entry 7) to compound 32 (under these conditions). Since ligand 29g gave the best conversion (under the conditions employed), catalyst loading was reduced to 1 mol % palladium (in the form of 0.5 mol % Pd2(dba)3) alongside 2 mol % 29g as ligand (Table 3, entry 2), and under these conditions, a conversion of 84% to 32 was achieved.

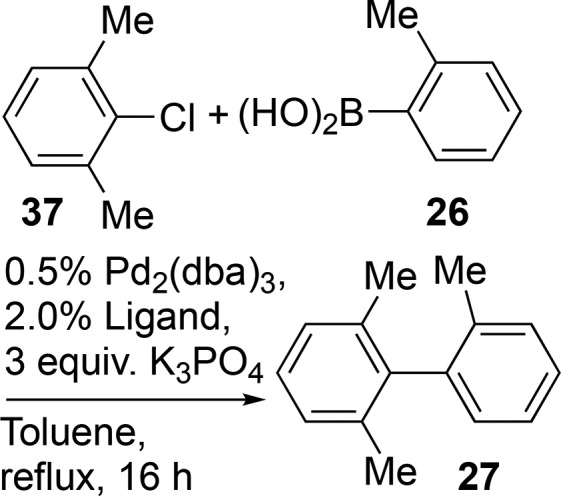

To further probe the utility of 1-aryl 5-phosphino 1,2,3-triazoles as ligands in Suzuki–Miyaura catalysis the synthesis of compound 27 from aryl chloride 37 and boronic acid 26 was investigated (shown in Table 4) deploying the same ligand set as in Table 3. The reaction conditions mirrored those used earlier for cross-coupling with bromide analogue 25 in Table 2, but in order to ensure good reaction conversions the reaction temperature was increased slightly (toluene at reflux).

Table 4. Ligand Screening: 1-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing Phosphine Ligand-Mediated, Palladium-Catalyzed, Reaction of Arylchloride 37 in the Formation of 27.

| entry | ligand | conversion [%]a,b | isolated yield [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29g | 99 | 93 |

| 2 | 29gc | 99 | 92 |

| 3 | 29h | 99 | 82 |

| 4 | 29m | 99 | 92 |

| 5 | 29n | 70 | |

| 6 | S-Phos (7) | 33 | 25 |

| 7 | X-Phos (8) | 99 | 90 |

Reaction conditions: 2-chloro-m-xylene (1.0 mmol), o-tolyboronic acid (1.5 mmol), potassium phosphate (3.0 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (0.5 mol %), ligand (2.0 mol %), toluene (3 mL), 10 h, 90 °C.

Determined by GC analysis with n-dodecane as internal standard.

Pd2(dba)3 (0.25 mol %), ligand (1.0 mol %).

Under the reaction conditions employed (Table 4), catalysts derived from triazole-containing ligands 29g, 29h, and 29m delivered compound 27 in quantitative yield (Table 4, entries 1, 3, and 4, respectively). Using 29g as ligand at a lower catalyst loading of 0.5 mol % of palladium proportionally, quantitative conversion to 27 (isolated yield 92%) was achieved. In this comparison, the use of S-Phos (7) as ligand gave 33% conversion (Table 4, entry 6), and the use of X-Phos (8) as ligand gave quantitative conversion (Table 4, entry 7) to compound 27.

Next, a demanding palladium-catalyzed reaction between 2-chloro-meta-xylene (37) and 2,4,6-trimethylphenylboronic acid (38) leading to product 32 was attempted. Two triazole ligand-based catalyst systems were compared against catalyst systems derived from S-Phos (7) and X-Phos (8); see Table 5.

Table 5. Ligand Screening: 1-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing Phosphine Ligand Mediate, Palladium-Catalyzed, Reaction of Arylchloride 37 in Formation of 32.

Reaction conditions: 2-chloro-m-xylene (0.5 mmol), 2,4,6-trimethylphenylboronic acid (1.0 mmol), potassium phosphate (2 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (2.0 mol %), ligand (8.0 mol %), toluene (3 mL), 18 h, reflux.

Determined by GC analysis with n-dodecane as internal standard.

Under the conditions employed, the four catalyst systems compared produced only moderate yields. That is not to say that these reactions could not be optimized further, but the side-by-side comparison revealed S-Phos (7) to be slightly better than triazole-containing phosphine 29g (55 versus 49% conversion; Table 5, entry 4 versus entry 1, respectively). Slightly lower conversions were obtained when 29m or X-Phos were used as ligands (Table 5 entries 2 and 4 respectively).

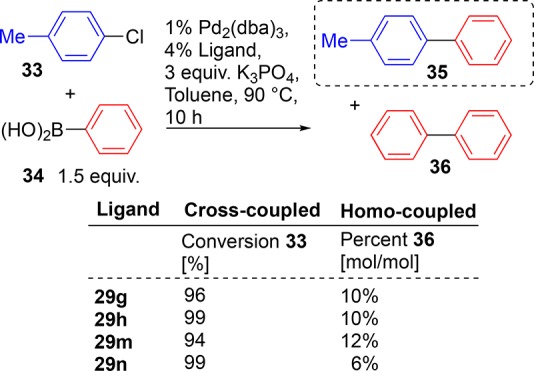

One potential problem with Suzuki–Miyaura catalyzed reactions, particularly evident when using less reactive aryl chlorides in cross-coupling, is homocoupling of the boronic acid containing reaction partner.122 In order to test our routine reaction protocols and our four selected triazole ligands (29g, 29h, 29m, and 29n) for their propensity to lead to undesired homocoupled product, the following reaction was probed. Aryl chloride 33 was reacted with 1.5 equiv of phenyl boronic acid 34. Catalyst loading was 2 mol % palladium and 4 mol % ligand. The reactions were conducted in toluene at 90 °C with 3 equiv of potassium phosphate as base; see Scheme 8. Set up like this, we can judge a reaction to be successful, i.e., not suffering from an adventitious homocoupling side reaction leading to product composition, if conversion of aryl chloride 33 is high (near 100%) and the amount of formed byproduct 36 is low. Choosing 1.5 equiv of boronic acid gives a chance for the formation of 36, thus evidencing the cross- versus homo-coupling potential of the ligands in the chosen Suzuki–Miyaura reaction under the conditions described.

Scheme 8. Percentage Homo-Coupled Product 36 under Described Reaction Conditions Using 50% Excess Boronic Acid 34.

All four of the tested ligands (Scheme 8, 29g, 29h, 29m, and 29n) gave good conversion to product 35 (ligands 29h and 29n leading to complete consumption of stating aryl chloride 33). In this case the apparently most bulky ligand, 29n, performed best giving just 6% (mol/mol) homocoupled product (36); the other three ligands gave rise to only slightly elevated amounts of homocoupled side product (10–12% (mol/mol)). Thus, demonstrating that under the conditions employed, reaction protocols used throughout this study do not suffer appreciably from loss of halide-containing starting materials through unwanted homocoupling.

Lead-like Compounds

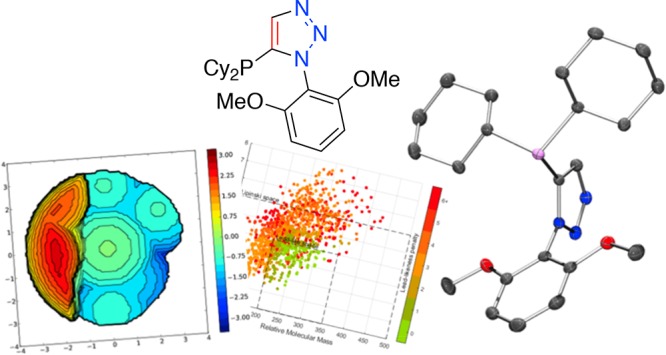

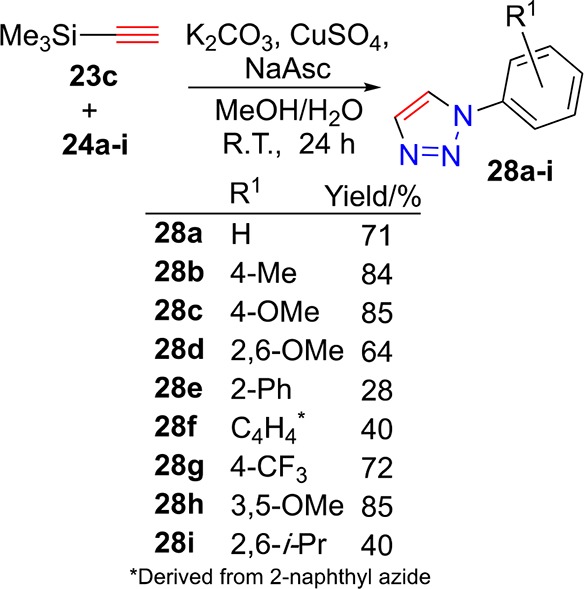

While the results discussed thus far have exemplified the effectiveness of ligands 29g and 29m to catalyze sterically demanding cross-coupling reactions, the ability to catalyze the cross-coupling of functionalities relevant to medicinal chemistry, to give lead- and drug-like products remains a critical need in the agrochemical and pharmaceutical sectors.77 To this end, a range of bis-aromatic products, containing motifs of the type that are commonly encountered in medicinal chemistry,123−125 were identified, and their synthesis embarked upon. The products of virtual Suzuki–Miyaura cross-couplings of 48 aromatic halides (iodides, bromides, or chlorides) and 44 aromatic boronic acids (or esters) from (i) a collection held within the lead research group; (ii) those curated within the University of Birmingham Scaffold Diversification Resource;126 and (iii) drawn from a boronic acid collection via the GSK Free Building Blocks resource; were enumerated and analyzed by the online resource LLAMA (Figure 9).118

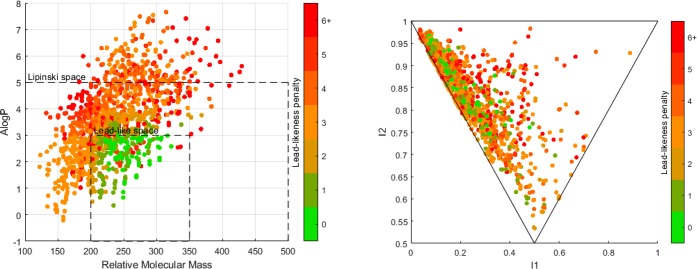

Figure 9.

Virtual Suzuki–Miyaura catalysis products generated and analyzed in the LLAMA web tool. Left: A log P versus molecular mass, Lipinski and lead-like space indicated. Right: PMI plot, rod, disc, sphere axis. (See the Supporting Information for data tables.)

The open-access web tool LLAMA allows the user to conduct virtual reactions and analyze the virtual product library for molecular properties such as molecular weight, A log P, and 3D character. Figure 9 left shows the full virtual library of 1661 compounds created from the virtual Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of the boronic acids and aryl halides described above. It shows that while the majority of these virtual products fall within Lipinkski space (Mw < 500, A log P < 5) only ∼20% lie within lead-like space as defined by Churcher et al. (200 < Mw < 350, A log P < 3). This fact is illustrated by the lead-likeness penalty scores of these compounds, which have an average of 3.47. This penalty scoring system was developed by the creators of LLAMA to visualize how far away from ideal lead-likeness a compound may be and incorporates all determined molecular properties into one score. Figure 9 (right side) shows the PMI analysis of the same 1661 virtual compounds in the library of virtual Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupled products. A PMI plot describes the 3D shape of the lowest energy conformation of a compound on a triangular plot. The upper left corner represents rod-like compounds, the bottom corner represents disc-like compounds, and the upper right corner represents spherical compounds. This analysis shows that the majority of the virtual library resides close to the rod–disc axis, representing flat compounds.

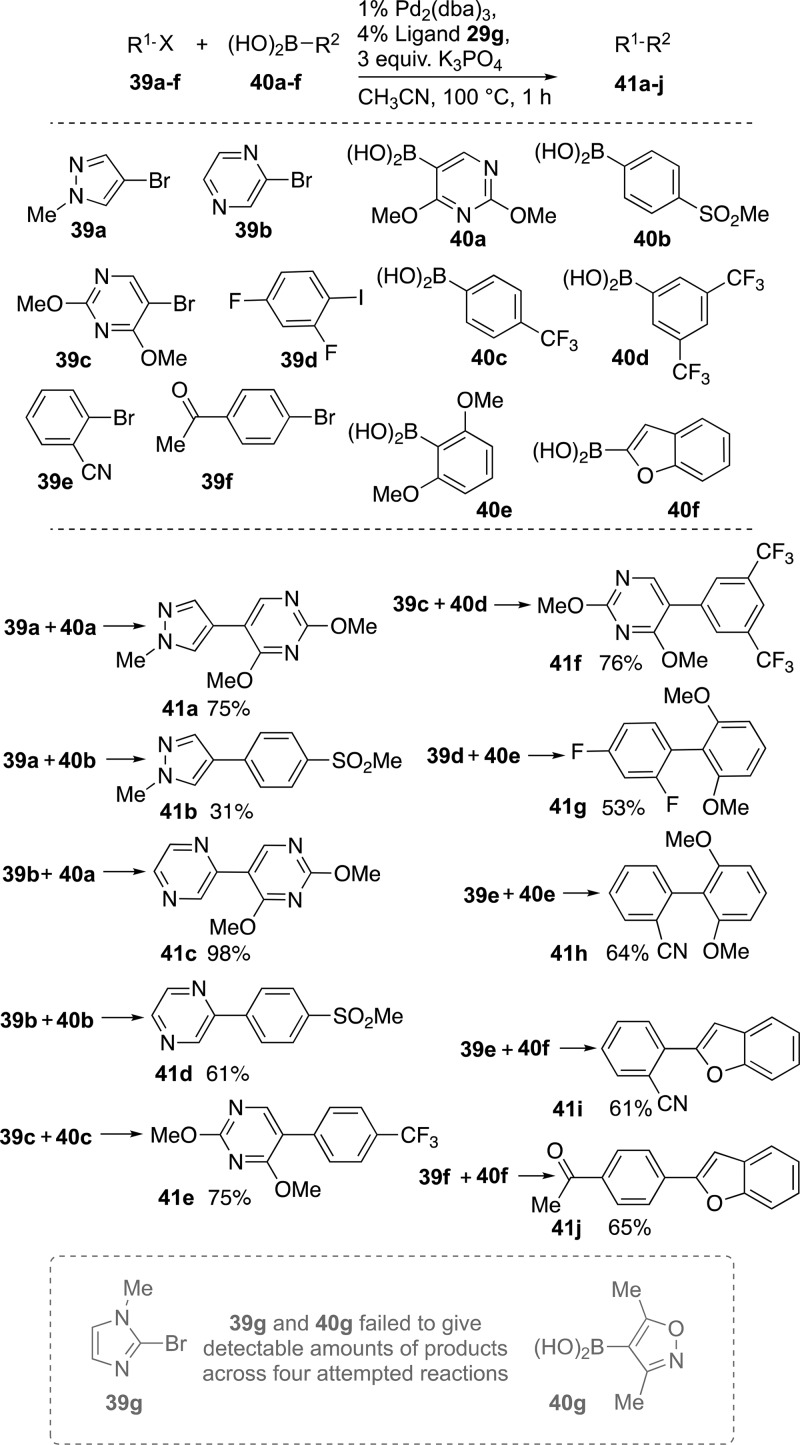

From the 1661 virtual compounds constructed within the LLAMA tool, 14 possible products that accessed preferable lead-like chemical space and were selected for testing 29g-mediated Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions, as in Scheme 9. In this case, the screening conditions involved microwave heating in a sealed-tube at 100 °C in acetonitrile for just 1 h. The possible products include challenging heteroatom-containing and/or ortho substituents, representing both a set of possible products displaying favorable characteristics for drug discovery and a robust challenge for road-testing our best new ligand, 29g.

Scheme 9. Microwave-Heated Synthesis (1 h) of 10 Lead-like Compounds by Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reactions Using 2 mol % Palladium and 4 mol % Ligand 29g.

Pleasingly, most of the reactions attempted gave greater than 50% isolated yield of these challenging cross-coupled products (41a–j); however, 2-bromo-1-methyl-1H-imidazole 39g and (3,5-dimethylisoxazol-4-yl)boronic acid 40g failed to deliver detectable amounts of desired cross-coupled products in four test scenarios under the conditions employed.

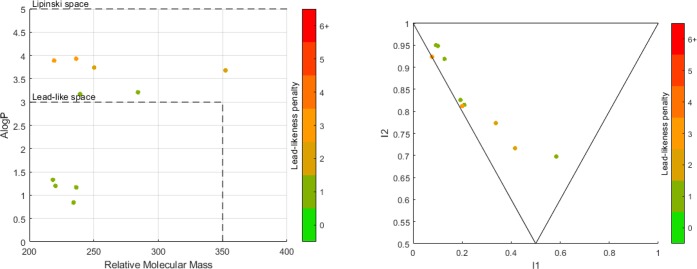

To determine the utility of the products created in this analysis, they were analyzed using the LLAMA web tool to determine their suitability as lead-like compounds (Figure 10). Figure 10 (left), shows how products 41a–j explore the drug-like space, with all products lying within the Lipinski space (Mw < 500, A log P < 5) and a significant proportion lying within the lead-like space (40% of the synthesized compounds). This illustrates the potential for this catalyst system to access both drug- and lead-like chemical space. Figure 10 (right) shows a PMI analysis of products 41a to j, this analysis demonstrates a capability of this catalyst system to access nonflat Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupled products.

Figure 10.

Left: Mw vs A log P. Right: PMI analysis of products synthesized in Scheme 9.

These analyzes show that these compounds can be described as high-quality starting points for drug discovery programs. These 10 compounds are now under evaluation for biological activity across a range of targets.127

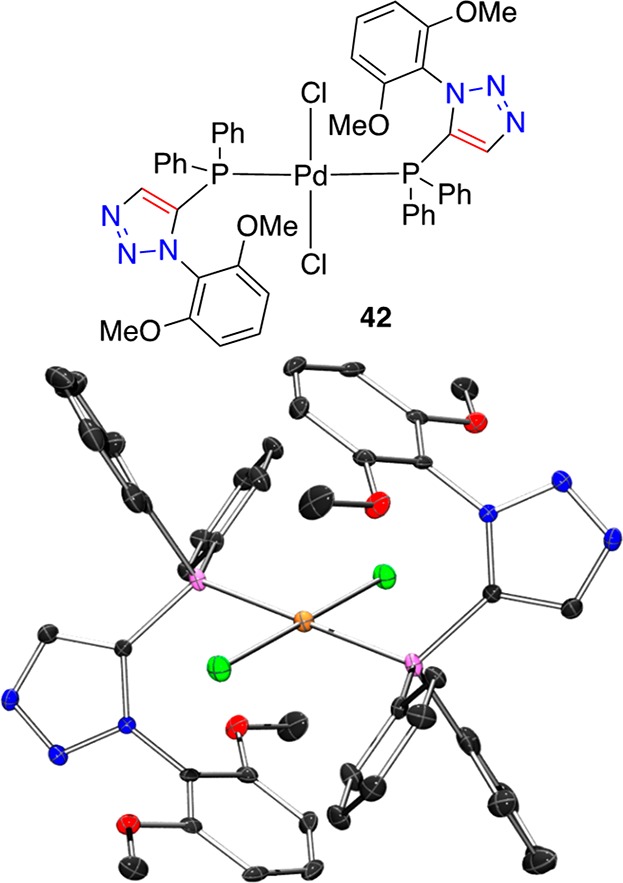

Palladium Complexes

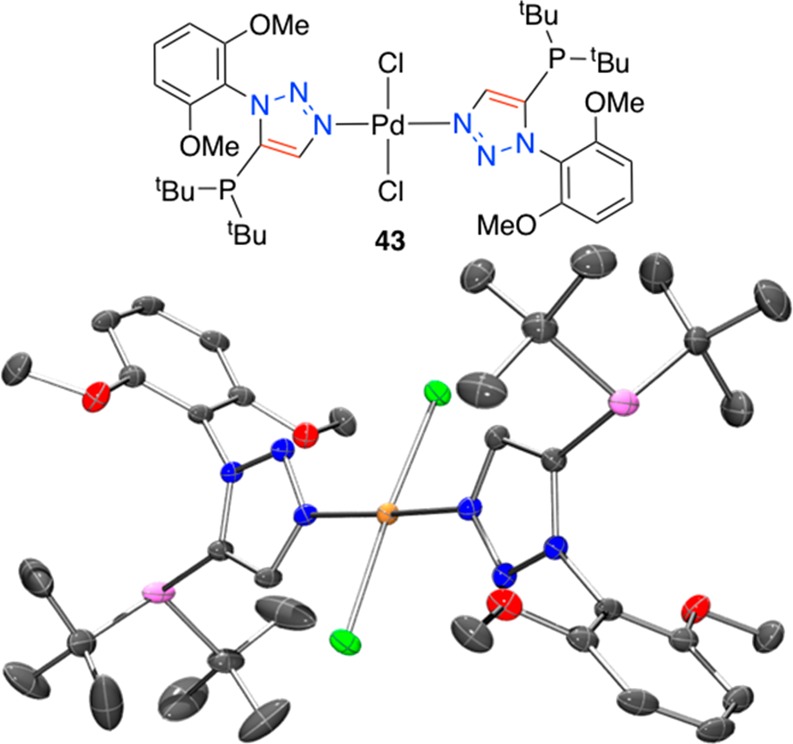

During the course of this study numerous attempts to grow crystals of palladium-phosphine complexes suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction were made. Thus far, two attempts to generate X-ray quality crystals of palladium phosphine complexes have been achieved, using ligands 29e and 29h with palladium(II) chloride.

The combination of 29e and trans-Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 in dichloromethane at room temperature led to the formation of material that was precipitated by addition of pentane and the residue thus obtained was recrystallized from dichloromethane and hexane. A representation of the single crystal XRD structure of the palladium complex (42) thus obtained is depicted in Figure 11. A 2:1 ligand/metal square planar trans dichloride palladium(II) complex 42 was identified. Complex 42 may offer insight into the structural features of 29 series complexes as catalysts. The five-membered 1,5-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole core presents the triazole 2,6-bismethoxy aryl fragment oriented toward the metal with an aryl-centroid···Pd distance of 3.843(2) Å, in this solid-state structure. The triazole phosphine ligand offers a distinct geometric difference to phenylene core ligands (c.f., S-Phos and X-Phos, Figure 3), being more akin to other five-membered ring core ligands (c.f., 9 and 10, Figure 3), generating a slightly wider metal-binding pocket while still offering a stabilizing shield about the metal center.

Figure 11.

Representation of the crystal structure of 42, ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level (Ortep3 for Windows and PovRay). The structure contains a palladium complex, which is located on an inversion center and two molecules of dichloromethane per complex. Only half of the complex and one dichloromethane molecule are unique. Pd···P bond lengths 2.322(9) Å. 2,6-Bismethoxy aryl-centroid···Pd 3.843(2) Å. Symmetry code used to generate equivalent atoms: 1 – x, −y, −z.

The combination of 29h and trans-Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 in dichloromethane at room temperature led to the formation of material that was precepted by addition of pentane and recrystallized from dichloromethane and hexane. A representation of the single crystal XRD structure of the palladium complex (43) thus obtained is depicted in Figure 12. To our surprise, the XRD crystal structure shows 29h functioning as a 3-N-coordinating ligand, with two such ligations are present about a trans-dichloride palladium(II) metal center. Since ligand 29h functions as expected in the aforementioned catalyzed reactions, it is suggested that a more crystalline and readily formed (kinetic) complex is formed under the crystallization conditions employed. However, that this stable complex is formed reminds us of another potentially important feature of the triazole-core ligands, namely, a rear-side ancillary coordination point. It is conceivable that the ancillary nitrogen may offer some advantages in some catalyzed reaction, such as aggregation suppression for example. Suffice it to say, the sterically encumbered phosphine face of ligand 29h, as evidenced by the isolation of 43, bodes well for understanding differing catalysis modes of action on steric rationales as well as opportunities for divergence from phenylene core ligands.

Figure 12.

Representation of the crystal structure of 43, ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level (Ortep3 for Windows and PovRay). The structure contains two molecules of dichloromethane per palladium complex (omitted for clarity).

Describing Phosphines

There is a growing body of literature discussing the importance of various parameters including steric effects116 of bulky phosphines83,84,128 relating to suitability and efficacy in catalysis (primarily as ligands for metals in metal mediated catalysis).108,115,129 While the Tolman cone angle has been an effective descriptor of ligand bulkiness for many years,111 it has been complimented more recently by Nolan’s percentage buried volume parameter (%Vbur).112 The %Vbur of ligands can be calculated using the SambVca (2.0) free web tool from Cavallo and co-workers;113,130 so we set about determining some steric parameters of our phosphines using this tool.

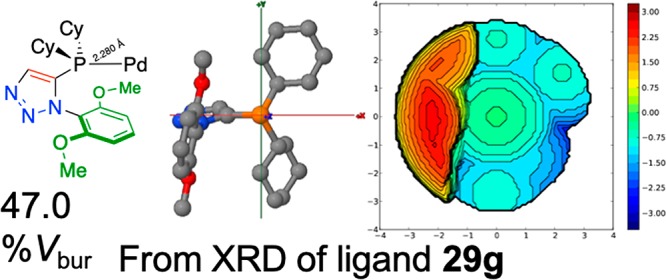

First, the crystal structure of the free ligand 29g was investigated, as follows: The PDB file corresponding to the XRD crystal structure of ligand 29g was edited in Spartan’16 Parallel Suite (Wave function Inc.) by changing the valence of phosphorus to four and adding a palladium atom with a standard bond length of 2.280 Å to generate a metal-coordinated model. The PBD file thus generated was not minimized or edited further, i.e., the atoms of the ligand remained in their crystallographically determined free-ligand position, and uploaded for analysis to the SambVca2.0 web tool for analysis. The added palladium atom was set as the center and then deleted; a summary of this analysis is shown in Figure 13. A steric map generated from this analysis is shown and a 47.0%Vbur was calculated, using otherwise default SambVca settings.

Figure 13.

Steric map of phosphine-palladium complex: Derived from crystal structure of free ligand 29g with a P–Pd distance of 2.280 Å applied, resulting in a 47.0%Vbur.

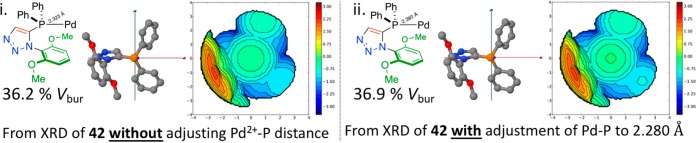

Following this analysis, the only palladium phosphine complex thus far successfully analyzed by single crystal X-ray diffraction studies (42) was investigated in a similar manner. Compound 42 is a square planar palladium(II) complex of ligand 29e and as such does not necessarily represent the catalytically relevant species, the determined %Vbur of 36.2% (Figure 14i) may not be the best comparator across a number of ligand structures, so three other forms of the complex were generated and compared. In order to find an appropriate comparison to fairly evaluate relative steric parameters of ligands 29e and 29g. The ligand portion of the crystal structure of 42 was edited in Spartan’16 Parallel Suite, the Pd–P bond length adjusted to 2.280 Å, and the SambVca-determined %Vbur of 36.9% (Figure 14ii) was essentially the same as that for the slightly longer, crystallographically determined, Pd–P bond length in the earlier analysis. Since a model to allow for comparison of ligands where crystallographically determined data is not available was ultimately sought two further analyses were conducted.

Figure 14.

(i) Chemical structure of part of the crystallographically determined complex 42, with a 2.323(2) Å Pd–P distance (from the crystal structure) used in the calculation of buried volume, 36.2%Vbur. (ii) Chemical structure of the bond-length-modified, crystal-structure-informed palladium complex of ligand 29e in complex 42 (2.280 Å Pd–P distance was used in the buried volume calculation), 36.9%Vbur.

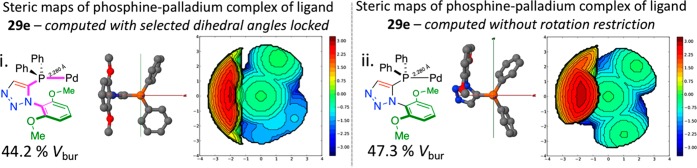

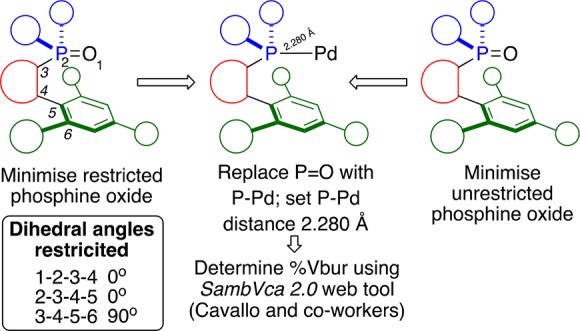

Sigman and co-workers have previously used phosphine oxides as computational models for structural minimization proxies of ligand–metal complexes,115 so it was reasoned that computational minimization of in silico generated phosphine oxides may be a sensible starting point to allow for comparison among some of the ligands in this report. Two approaches were compared for optimizing and computationally determining the %Vbur of ligand 29e (summarized in Figure 15) using Spartan’16 Parallel Suite. In one case a phosphine oxide structure with no geometric restrictions was used (Figure 15, right); in the second case, the dihedral geometries of atoms 1–6 were restricted presenting the ligand’s ancillary aryl group directly and orthogonally aligned to the coordination vector of the phosphine (the P–O bond in this minimization), as shown in (Figure 15, left). Through comparison of the geometry unrestricted and geometry restricted protocols, with the structurally determined geometry (as shown in Figure 13) a protocol for analysis across the ligands of this report might be reasonably determined. In both cases the same minimization and optimization cascade was adopted; the structures used for computationally determined %Vbur calculations were obtained as follows. First, molecular mechanics (MMFF) conformer distribution (1000 max conformers) and subsequent molecular mechanics equilibrium geometries were ranked, and the 20 lowest energy conformers were retained for DFT investigation. The 20 retained conformers’ equilibrium geometries were used as starting points for ground-state, gas phase equilibrium geometry determination (B3LYP 6-31G*). The lowest energy structure thus obtained was then edited to replace the oxygen (of the phosphine oxide) with a palladium atom and a standard P–Pd bond length of 2.280 Å was applied (Figure 15, center).

Figure 15.

Protocol for obtaining structures for comparison of steric parameters via an unrestricted (right) and a dihedral angles restricted model (left). In both cases, a phosphine oxide model was minimized using Spartan’16 and the P=O later replaced with a P–Pd bond of 2.280 Å. The structures thus obtained were then analyzed by the SambVca2.0 free web tool to determine the %Vbur and to create a steric map.

The procedure outlined in Figure 15 was first applied to ligand 29e, and buried volumes of 44.2 and 47.3% were determined for the restricted and unrestricted geometries, respectively (Figure 16) and compared to the buried volume determined crystallographically. While this protocol gives slightly higher values, the restricted geometry model is more closely aligned to the XRD-derived model than the unrestricted one. With this information alone, it is difficult to ascertain if any one model provides a superior approach for assessing ligands where solid state data is not available. Furthermore, it should be remembered that the 42-derived %Vbur numbers are from solid-state structures and might not offer the best cross-ligand comparison. As such, the most active ligands of our study were examined using both protocols shown below (Figure 17).

Figure 16.

(i) Chemical structure and computationally determined steric map and buried volume, structures derived in silico and calculated with restricted dihedral angles as describe in Figure 15 (left), 44.2%Vbur. (ii) Chemical structure and computationally determined steric map and buried volume of structures derived in silico and calculated without any dihedral restrictions as describe in Figure 15 (right), 47.3%Vbur.

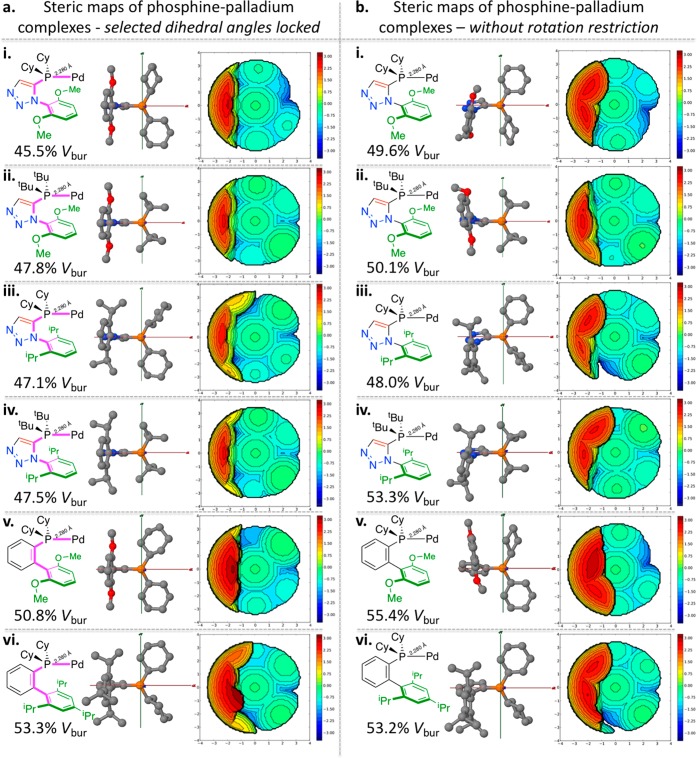

Figure 17.

SambVca2.0 derived %Vbur and steric maps for the: (a) left side: (i) 29g; (ii) 29h; (iii) 29n; (iv) 29m; (v) 7 S-Phos; (vi) 8 X-Phos, derived palladium complexes of structures derived in silico and calculated with restricted dihedral angles as describe in Figure 15 (left); (b) right side: (i) 29g; (ii) 29h; (iii) 29n; (iv) 29m; (v) 7 S-Phos; (vi) 8 X-Phos, derived palladium complexes of structures derived in silico and calculated without any dihedral restrictions as describe in Figure 15 (right).

Computed structures, percentage buried volumes, and steric maps of the six ligands of Figure 8, following the protocol outlined in Figure 15, are shown in Figure 17. The left side shows the information relating to restricted dihedral angle restricted complexes and the right side shows the structures obtained without imposing any geometrical restrictions (other than the 2.280 Å P–Pd distances imposed throughout). It is interesting and confounded our expectations that the unrestricted geometry-minimized structures give a higher buried volume than the restricted dihedral angle structures (Figure 17 column a versus column b). Among the two data treatments, there is broad agreement with and relative similarity to each other. While the geometry-unrestricted structures of triazole ligands bear a striking resemblance (by rudimentary visual inspection) to any XRD-derived structures, the buried volume determinations of previously reported S- and X-Phos (by the P=O minimization proxy discussed earlier) complexes more closely match the geometry-restricted models we employed (Table 6, entries 6 and 7).

Table 6. Calculated (Spartan v16 and SambVca2.0) Steric Properties of 29e, 29g, 29h, 29m, 29n, S-Phos 7, and X-Phos 8.

| entry | ligand | Vbur calcd [%] (restricted) | Vbur calcd [%] (unrestricted) | Ar centroid–Pd distance [Å] (restricted) | Ar centroid–Pd distance [Å] (unrestricted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29e | 44.2 (36.2)a | 47.3 | 3.363 (3.843(2))a | 4.176 |

| 2 | 29g | 45.5 (46.9)b | 49.6 | 3.403 (3.457)b | 3.745 |

| 3 | 29h | 47.8 | 50.1 | 3.558 | 3.580 |

| 4 | 29m | 47.1 | 48.0 | 3.639 | 3.901 |

| 5 | 29n | 47.5 | 53.3 | 3.647 | 3.794 |

| 6 | 7 (S-Phos) | 50.8 (49.7)c | 55.4 | 3.127 | 3.253 |

| 7 | 8 (X-Phos) | 53.3 (53.1)c | 53.2 | 3.309 | 3.481 |

From the steric maps of Figure 17, it was noted that the space between the dark red bulky zone (to the left of the steric maps arising from the ancillary aryl groups of all ligands) protrudes in a manner to give more space between the central axis and red zone. Since space near the coordination site may be crucial in permitting reaction with bulky substrates, we also report the distance between the ancillary aryl group’s centroid and the computed metal center (Table 6) for both the geometry-restricted and unrestricted ligands of Figure 8 are also listed in Table 6 (and contrasted against the data determined for ligand 29e). In Entry 2 the data arising from analysis of the previously detailed ligand crystal-structure-determined structures of 29g–complexes are given in parentheses. Between the restricted and unrestricted models of ligand–complex analysis, the centroid distance correlates more closely with the dihedral angle restricted model of a 29g–Pd complex.

It is notable that the P=O ligand minimization protocol adopted gives good structural parameter agreement between those determined for palladium complexes of ligand 29g both derived computationally and from a modified XRD structure of free ligand 29g (Table 6, entry 1). By analyzing 29a–n side-by-side using the same restricted dihedral angle minimization protocol (up to 10 conformers analyzed by DFT methods abbreviating the earlier minimization cascade for newly analyzed ligands) and plotting the computed %Vbur values against conversion to 27 (data from Table 2), as shown in Figure 18, it can be seen that a strong bulkiness versus conversion trend exists. Essentially any %Vbur value above 46% leads to quantitative conversion to products, under the prescribed conditions.

Figure 18.

Conversion to 27 (see Table 2) versus computed burried volume (%) as determined by the protocol discussed in Figure 15.

Further analysis of the data obtained for conversion in reactions catalyzed by 29 ligands is only against smaller data sets, and significant correlations of variances in conversions do not lead to any meaningfully comparable correlations. However, further study of cross-couplings of very bulky aryl chlorides may be warranted in the future since an intriguing balance between bulk and centroid distance is suggested (see the Supporting Information), but across only four data points surveyed to date, it may be too early to draw conclusion yet.132 A pre-peer-reviewed preprint of this article was deposited and may be viewed elsewhere.133

Conclusions

Two series of 1,2,3-triazole-containing 5-phosphino ligands were synthesized and tested as ligands in palladium catalyzed cross-coupling Suzuki–Miyaura reactions of bulky and heteroatom-containing substrates. The structural parameters of the 4-H triazole series (29) were determined by a restricted dihedral angle, phosphine oxide surrogate model, and a strong dependence upon bulkiness and catalytic activity were noted. Furthermore, a link to the space between the metal and the ancillary aryl group in the computed complexes was noted, suggesting bulkiness of ligand and space around the metal may both be implicated in delineating trends in cross-coupling of the most bulky and challenging substrates. Notably, triazole-nitrogens’ may not be completely innocent in the coordination environment created by these ligands, with a nitrogen coordination complex being characterized by XRD in one case. The ligands synthesized were benchmarked against commercially available ligands (X- and S-Phos) and in some cases the best triazole ligands match or outperformed them under the employed conditions, in like-for-like tests in triplicate. The phosphine ligands reported and characterized in this report represent easy to modify catalytic scaffolds that could be use in future library generation efforts and we are looking forward to facilitating access to these compounds and allowing others to include this type of ligand in their own catalyst screening campaigns.

Acknowledgments

J.S.F., Y.Z., P.C., H.v.N., and L.M. thanks the University of Birmingham for support. J.S.F. acknowledges the CASE consortium for networking opportunities.134,135 B.R.B. thanks Loughborough University and Research Councils UK for a RCUK Fellowship. J.S.F. thanks the Royal Society for an Industrial Fellowship and the EPSRC for funding (EP/J003220/1). Dr. Chi Tsang and Dr. Peter Ashton are thanked for helpful discussions about mass spectrometry. Dr. Cécile S. Le Duff is thanked for advice on NMR spectroscopy. Helena Dodd is thanked for providing an initial data analysis and presentation app for MatLab. J.S.F. and B.R.B. acknowledge the support of a Wellcome Trust ISSF award within the University of Birmingham. J.S.F. and H.v.N. are thankful for the support of the NEURAM H2020 FET Open project 712821. All investigators are grateful for a Royal Society Research Grant (2012/R1) that underpins this project. The GSK free building block programme furnished a collection of boronic acids from which 40a was sourced. The University of Birmingham Scaffold Diversification Resource is gratefully acknowledged for providing access to a collection of compounds from which 39a–f and 40b–f were sourced.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00539.

Accession Codes

CCDC 1856208–1856212 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript, specific contributions in addition to this are listed for each coauthor in alphabetical order: B.R.B. helped direct aspects of the research, initiated some of the steric parameter analysis and gave input and critical assessment throughout the progress of the project; P.C. analyzed molecular property analysis through use of LLAMA and wrote aspects of the manuscript and ESI pertaining to this aspect; J.S.F. led and coconceived the project, providing critical assessment of data, day-to-day project management and oversight, directed all aspects throughout, supervised the experimental work and wrote the majority of the manuscript; L.M. is responsible for collecting, analyzing and preparing for publication single crystal XRD data, writing aspects of the main text and ESI and training oversight of Y.Z. in aspects of XRD data collection and analysis; H.v.N. conducted all the experiments of Scheme 9 offered additional advice and wrote aspects of the ESI; Y.Z. co-conceived aspects of the project, conducted all ligand synthesis and all-bar the Scheme 9 reactions, wrote aspects of the main text, drafted a large proportion of the ESI, offered critical suggestions, under the mentorship of L.M. conducted some of the XRD data collection and analysis.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Finn M. G.; Kolb H. C.; Fokin V. V.; Sharpless K. B. Click chemistry - Definition and aims. Prog. Chem. 2008, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C.; Finn M. G.; Sharpless K. B. Click chemistry: Diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W. G.; Green L. G.; Grynszpan F.; Radic Z.; Carlier P. R.; Taylor P.; Finn M. G.; Sharpless K. B. Click chemistry in situ: Acetylcholinesterase as a reaction vessel for the selective assembly of a femtomolar inhibitor from an array of building blocks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1053–1057. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev V. V.; Green L. G.; Fokin V. V.; Sharpless K. B. A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective “Ligation” of Azides and Terminal Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornøe C. W.; Christensen C.; Meldal M. Peptidotriazoles on Solid Phase: [1,2,3]-Triazoles by Regiospecific Copper(I)-Catalyzed 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions of Terminal Alkynes to Azides. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Based upon citation reports using Thomas Reuters Web of Science TM for the term “click reaction”.

- Meldal M.; Tornøe C. W. Cu-Catalyzed Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2952–3015. 10.1021/cr0783479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses J. E.; Moorhouse A. D. The growing applications of click chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1249–1262. 10.1039/B613014N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurugan P.; Matosiuk D.; Jozwiak K. Click Chemistry for Drug Development and Diverse Chemical–Biology Applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4905–4979. 10.1021/cr200409f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amblard F.; Cho J. H.; Schinazi R. F. Cu(I)-Catalyzed Huisgen Azide–Alkyne 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reaction in Nucleoside, Nucleotide, and Oligonucleotide Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 4207–4220. 10.1021/cr9001462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sagheer A. H.; Brown T. Click chemistry with DNA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1388–1405. 10.1039/b901971p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iha R. K.; Wooley K. L.; Nyström A. M.; Burke D. J.; Kade M. J.; Hawker C. J. Applications of Orthogonal “Click” Chemistries in the Synthesis of Functional Soft Materials. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 5620–5686. 10.1021/cr900138t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze B.; Schubert U. S. Beyond click chemistry - supramolecular interactions of 1,2,3-triazoles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 2522–2571. 10.1039/c3cs60386e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tron G. C.; Pirali T.; Billington R. A.; Canonico P. L.; Sorba G.; Genazzani A. A. Click chemistry reactions in medicinal chemistry: Applications of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between azides and alkynes. Med. Res. Rev. 2008, 28, 278–308. 10.1002/med.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C.; Finn M. G.; Sharpless K. B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Fan E. Solid phase synthesis of peptidotriazoles with multiple cycles of triazole formation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 665–669. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.11.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson A. W.; Wood W. J. L.; Hornsby M.; Lesley S.; Spraggon G.; Ellman J. A. Identification of Selective, Nonpeptidic Nitrile Inhibitors of Cathepsin S Using the Substrate Activity Screening Method. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6298–6307. 10.1021/jm060701s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W. J. L.; Patterson A. W.; Tsuruoka H.; Jain R. K.; Ellman J. A. Substrate Activity Screening: A Fragment-Based Method for the Rapid Identification of Nonpeptidic Protease Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15521–15527. 10.1021/ja0547230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuprakov S.; Chernyak N.; Dudnik A. S.; Gevorgyan V. Direct Pd-Catalyzed Arylation of 1,2,3-Triazoles. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2333–2336. 10.1021/ol070697u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamajala K. D. B.; Patil M.; Banerjee S. Pd-Catalyzed Regioselective Arylation on the C-5 Position of N-Aryl 1,2,3-Triazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 3003–3011. 10.1021/jo5026145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn J.; Pinczewska A.; Goldup S. M. Synthesis of a Rotaxane CuI Triazolide under Aqueous Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13318–13321. 10.1021/ja407446c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlquist M.; Fokin V. V. Enhanced reactivity of dinuclear copper(I) acetylides in dipolar cycloadditions. Organometallics 2007, 26, 4389–4391. 10.1021/om700669v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley B. R.; Dann S. E.; Heaney H. Experimental Evidence for the Involvement of Dinuclear Alkynylcopper(I) Complexes in Alkyne-Azide Chemistry. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6278–6284. 10.1002/chem.201000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley B. R.; Dann S. E.; Harris D. P.; Heaney H.; Stubbs E. C. Alkynylcopper(I) polymers and their use in a mechanistic study of alkyne-azide click reactions. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2274–2276. 10.1039/b924649e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell B. T.; Malik J. A.; Fokin V. V. Direct Evidence of a Dinuclear Copper Intermediate in Cu(I)-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloadditions. Science 2013, 340, 457–460. 10.1126/science.1229506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarem A.; Berg R.; Rominger F.; Straub B. F. A Fluxional Copper Acetylide Cluster in CuAAC Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7431–7435. 10.1002/anie.201502368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott P. I. P.Organometallic complexes with 1,2,3-triazole-derived ligands. In Organometallic Chemistry; Fairlamb I. J. S., Lynam J. M., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2014; Vol. 39, Chapter 1, pp 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schweinfurth D.; Pattacini R.; Strobel S.; Sarkar B. New 1,2,3-triazole ligands through click reactions and their palladium and platinum complexes. Dalton Trans 2009, 9291–9297. 10.1039/b910660j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Saleem F.; Singh A. K. ’Click’ generated 1,2,3-triazole based organosulfur/selenium ligands and their Pd(II) and Ru(II) complexes: their synthesis, structure and catalytic applications. Dalton Trans 2016, 45, 11445–11458. 10.1039/C6DT01406B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.; Wang Y.; Wen X.; Ding C.; Li Y. Dual-functional click-triazole: a metal chelator and immobilization linker for the construction of a heterogeneous palladium catalyst and its application for the aerobic oxidation of alcohols. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2979–2981. 10.1039/c2cc18023e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohloch S.; Schweinfurth D.; Sommer M. G.; Weisser F.; Deibel N.; Ehret F.; Sarkar B. The redox series [Ru(bpy)2(L)]n, n = + 3, + 2, + 1, 0, with L = bipyridine, ″click″ derived pyridyl-triazole or bis-triazole: a combined structural, electrochemical, spectroelectrochemical and DFT investigation. Dalton Trans 2014, 43, 4437–4450. 10.1039/C3DT52898G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarney E. P.; Hawes C. S.; Blasco S.; Gunnlaugsson T. Synthesis and structural studies of 1,4-di(2-pyridyl)-1,2,3-triazole dpt and its transition metal complexes; a versatile and subtly unsymmetric ligand. Dalton Trans 2016, 45, 10209–10221. 10.1039/C6DT01416J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratsos I.; Urankar D.; Zangrando E.; Genova-Kalou P.; Kosmrlj J.; Alessio E.; Turel I. 1-(2-Picolyl)-substituted 1,2,3-triazole as novel chelating ligand for the preparation of ruthenium complexes with potential anticancer activity. Dalton Trans 2011, 40, 5188–5199. 10.1039/c0dt01807d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury B.; Khatua S.; Dutta R.; Chakraborty S.; Ghosh P. Bis-Heteroleptic Ruthenium(II) Complex of a Triazole Ligand as a Selective Probe for Phosphates. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 8061–8070. 10.1021/ic5010598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Hernández J. M.; Yang C.-H.; Beltrán J. I.; Lemaur V.; Polo F.; Fröhlich R.; Cornil J.; De Cola L. Control of the Mutual Arrangement of Cyclometalated Ligands in Cationic Iridium(III) Complexes. Synthesis, Spectroscopy, and Electroluminescence of the Different Isomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10543–10558. 10.1021/ja201691b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanick K. N.; Ladouceur S.; Zysman-Colman E.; Ding Z. Bright electrochemiluminescence of iridium(III) complexes. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3179–3181. 10.1039/c2cc16385c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur S.; Fortin D.; Zysman-Colman E. Enhanced Luminescent Iridium(III) Complexes Bearing Aryltriazole Cyclometallated Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11514–11526. 10.1021/ic2014013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T. R.; Hilgraf R.; Sharpless K. B.; Fokin V. V. Polytriazoles as Copper(I)-Stabilizing Ligands in Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2853–2855. 10.1021/ol0493094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels H. A.; Zhu L. Ligand-Assisted, Copper(II) Acetate-Accelerated Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition. Chem. - Asian J. 2011, 6, 2825–2834. 10.1002/asia.201100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew P.; Neels A.; Albrecht M. 1,2,3-Triazolylidenes as Versatile Abnormal Carbene Ligands for Late Transition Metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13534–13535. 10.1021/ja805781s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpin K. J.; Paul U. S. D.; Lee A.-L.; Crowley J. D. Gold(i) ″click″ 1,2,3-triazolylidenes: synthesis, self-assembly and catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 328–330. 10.1039/C0CC02185G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley J. D.; Lee A.-L.; Kilpin K. J. 1,3,4-Trisubstituted-1,2,3-Triazol-5-ylidene ‘Click’ Carbene Ligands: Synthesis, Catalysis and Self-Assembly. Aust. J. Chem. 2011, 64, 1118–1132. 10.1071/CH11185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. R.; Young P. C.; Lucas N. T.; Lee A.-L.; Crowley J. D. Gold(I) and Palladium(II) Complexes of 1,3,4-Trisubstituted 1,2,3-Triazol-5-ylidene “Click” Carbenes: Systematic Study of the Electronic and Steric Influence on Catalytic Activity. Organometallics 2013, 32, 7065–7076. 10.1021/om400773n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffard J.; Keitz B. K.; Tonner R.; Guisado-Barrios G.; Frenking G.; Grubbs R. H.; Bertrand G. Synthesis of Highly Stable 1,3-Diaryl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-5-ylidenes and Their Applications in Ruthenium-Catalyzed Olefin Metathesis. Organometallics 2011, 30, 2617–2627. 10.1021/om200272m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T.; Terashima T.; Ogata K.; Fukuzawa S.-i. Copper(I) 1,2,3-Triazol-5-ylidene Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for Click Reactions of Azides with Alkynes. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 620–623. 10.1021/ol102858u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Jarillo M.; Mendoza-Espinosa D.; Salazar-Pereda V.; González-Montiel S. Synthesis and Catalytic Benefits of Tetranuclear Gold(I) Complexes with a C4-Symmetric Tetratriazol-5-ylidene. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4305–4312. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid J.; Frey W.; Peters R. Polynuclear Enantiopure Salen–Mesoionic Carbene Hybrid Complexes. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4313–4324. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzhalov M. A.; Legkodukh A. S.; Anisimova T. B.; Novikov A. S.; Suslonov V. V.; Luzyanin K. V.; Kukushkin V. Y. Tetrazol-5-ylidene Gold(III) Complexes from Sequential [2 + 3] Cycloaddition of Azide to Metal-Bound Isocyanides and N4 Alkylation. Organometallics 2017, 36, 3974–3980. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper L.-A.; Wei X.; Hock S. J.; Pöthig A.; Öfele K.; Cokoja M.; Herrmann W. A.; Kühn F. E. Gold(I) Complexes with “Normal” 1,2,3-Triazolylidene Ligands: Synthesis and Catalytic Properties. Organometallics 2013, 32, 3376–3384. 10.1021/om400318p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.; Zhao P.; Astruc D. Catalysis by 1,2,3-triazole- and related transition-metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 272, 145–165. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scrafton D. K.; Taylor J. E.; Mahon M. F.; Fossey J. S.; James T. D. Click-fluors″: Modular fluorescent saccharide sensors based on a 1,2,3-triazole ring. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2871–2874. 10.1021/jo702584u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai W.; Chapin B. M.; Yoshizawa A.; Wang H.-C.; Hodge S. A.; James T. D.; Anslyn E. V.; Fossey J. S. Click-fluors″: triazole-linked saccharide sensors. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 918–928. 10.1039/C6QO00171H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai W.; Male L.; Fossey J. S. Glucose selective bis-boronic acid click-fluor. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2218–2221. 10.1039/C6CC08534B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain W. D.; Buckley B.; Fossey J. S.. Asymmetric “click” chemistry focusing on the copper catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Abstr. Pap. - Am. Chem. Soc., 2015, CATL-207. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain W. D. G.; Buckley B. R.; Fossey J. S. Kinetic resolution of alkyne-substituted quaternary oxindoles via copper catalysed azide-alkyne cycloadditions. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 17217–17220. 10.1039/C5CC04886A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain W. D. G.; Chapin B. M.; Zhai W.; Lynch V. M.; Buckley B. R.; Anslyn E. V.; Fossey J. S. The Bull-James assembly as a chiral auxiliary and shift reagent in kinetic resolution of alkyne amines by the CuAAC reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 10778–10782. 10.1039/C6OB01623E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain W. D. G.; Dalling A. G.; Sun Z.; Le Duff C. S.; Male L.; Buckley B. R.; Fossey J. S. Simultaneous Clicknetic Resolution Coetaneous catalytic kinetic resolution of alkynes and azides through asymmetric triazole formation. ChemRxiv 2017, 10.26434/chemrxiv.5663623.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain W. D. G.; Buckley B. R.; Fossey J. S. Asymmetric Copper-Catalyzed Azide–Alkyne Cycloadditions. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3629–3636. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fossey J. S.; James T. D. Boronic Acid Based Modular Fluorescent Saccharide Sensors. Rev. Fluoresc. 2009, 2007, 103–118. 10.1007/978-0-387-88722-7_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fossey J. S.; James T. D. Boronic acid based receptors. Supramol. Chem.: Mol. Nanomater. 2012, 2, 1346–1379. 10.1002/9780470661345.smc072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyabu R.; Kubo Y.; James T. D.; Fossey J. S. Boronic acid building blocks: tools for sensing and separation. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 1106–1123. 10.1039/c0cc02920c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyabu R.; Kubo Y.; James T. D.; Fossey J. S. Boronic acid building blocks: tools for self assembly. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 1124–1150. 10.1039/C0CC02921A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull S. D.; Davidson M. G.; van den Elsen J. M. H.; Fossey J. S.; Jenkins A. T. A.; Jiang Y.-B.; Kubo Y.; Marken F.; Sakurai K.; Zhao J.; James T. D. Exploiting the Reversible Covalent Bonding of Boronic Acids: Recognition, Sensing, and Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 312–326. 10.1021/ar300130w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai W.; Sun X.; James T. D.; Fossey J. S. Boronic Acid-Based Carbohydrate Sensing. Chem. - Asian J. 2015, 10, 1836–1848. 10.1002/asia.201500444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S. Y.; Wang H. C.; Flower S. E.; Fossey J. S.; Jiang Y. B.; James T. D. Suzuki homo-coupling reaction based fluorescent sensors for monosaccharides. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 35238–35241. 10.1039/C4RA07331B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley B. R. Recent Advances/Contributions in the Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction. Boron: Sensing, Synthesis and Supramolecular Self-Assembly 2015, 389–409. 10.1039/9781782622123-00389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson Seechurn C. C. C.; Kitching M. O.; Colacot T. J.; Snieckus V. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling: A Historical Contextual Perspective to the 2010 Nobel Prize. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5062–5085. 10.1002/anie.201107017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littke A. F.; Fu G. C. Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of aryl chlorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4176–4211. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan N. T. S.; Van Der Sluys M.; Jones C. W. On the Nature of the Active Species in Palladium Catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura Couplings – Homogeneous or Heterogeneous Catalysis, A Critical Review. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 609–679. 10.1002/adsc.200505473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald S. L. Transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling and the Heck coupling processes: Powerful reactions for carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 1524–1524. 10.1002/adsc.200404335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaura N. Heck and cross-coupling reactions: Two core chemistries in metal-catalyzed organic syntheses. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 1522–1523. 10.1002/adsc.200404320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.; Buchwald S. L. Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reactions Employing Dialkylbiaryl Phosphine Ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1461–1473. 10.1021/ar800036s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S.; Manabe K. Synthetic method for multifunctionalized oligoarenes using pinacol esters of hydroxyphenylboronic acids. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2589–2591. 10.1039/b603574d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rygus J. P. G.; Crudden C. M. Enantiospecific and Iterative Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18124–18137. 10.1021/jacs.7b08326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozuch S.; Martin J. M. L. What Makes for a Bad Catalytic Cycle? A Theoretical Study on the Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction within the Energetic Span Model. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 246–253. 10.1021/cs100129u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Zhang X.; Liang H.; Cao Z.; Zhao X.; He Y.; Wang S.; Pang J.; Zhou Z.; Ke Z.; Qiu L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Axially Chiral Biaryl Monophosphine Oxides via Direct Asymmetric Suzuki Coupling and DFT Investigations of the Enantioselectivity. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1390–1397. 10.1021/cs500208n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutchukian P. S.; Dropinski J. F.; Dykstra K. D.; Li B.; DiRocco D. A.; Streckfuss E. C.; Campeau L.-C.; Cernak T.; Vachal P.; Davies I. W.; Krska S. W.; Dreher S. D. Chemistry informer libraries: a chemoinformatics enabled approach to evaluate and advance synthetic methods. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2604–2613. 10.1039/C5SC04751J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littke A. F.; Dai C. Y.; Fu G. C. Versatile catalysts for the Suzuki cross-coupling of arylboronic acids with aryl and vinyl halides and triflates under mild conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4020–4028. 10.1021/ja0002058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hundertmark T.; Littke A. F.; Buchwald S. L.; Fu G. C. Pd(PhCN)2Cl2/P(t-Bu)3: A versatile catalyst for sonogashira reactions of aryl bromides at room temperature. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 1729–1731. 10.1021/ol0058947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littke A. F.; Fu G. C. Heck reactions in the presence of P(t-Bu)3: Expanded scope and milder reaction conditions for the coupling of aryl chlorides. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 10–11. 10.1021/jo9820059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littke A. F.; Fu G. C. A convenient and general method for Pd-catalyzed Suzuki cross-couplings of aryl chlorides and arylboronic acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 3387–3388. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G. C. The Development of Versatile Methods for Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions of Aryl Electrophiles through the Use of P(t-Bu)3 and PCy3 as Ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1555–1564. 10.1021/ar800148f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M.; Buchwald S. L. A Bulky Biaryl Phosphine Ligand Allows for Palladium-Catalyzed Amidation of Five-Membered Heterocycles as Electrophiles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4710–4713. 10.1002/anie.201201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman R. A.; Buchwald S. L. Pd-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura reactions of aryl halides using bulky biarylmonophosphine ligands. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 3115–3121. 10.1038/nprot.2007.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barder T. E.; Walker S. D.; Martinelli J. R.; Buchwald S. L. Catalysts for Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling Processes: Scope and Studies of the Effect of Ligand Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4685–4696. 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Anderson K. W.; Zim D.; Jiang L.; Klapars A.; Buchwald S. L. Expanding Pd-Catalyzed C–N Bond-Forming Processes: The First Amidation of Aryl Sulfonates, Aqueous Amination, and Complementarity with Cu-Catalyzed Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6653–6655. 10.1021/ja035483w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno N. C.; Tudge M. T.; Buchwald S. L. Design and preparation of new palladium precatalysts for C-C and C-N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 916–920. 10.1039/C2SC20903A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno N. C.; Niljianskul N.; Buchwald S. L. N-Substituted 2-Aminobiphenylpalladium Methanesulfonate Precatalysts and Their Use in C–C and C–N Cross-Couplings. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 4161–4166. 10.1021/jo500355k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford R. B.; Cazin C. S. J.; Holder D. The development of palladium catalysts for C-C and C-heteroatom bond forming reactions of aryl chloride substrates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 2283–2321. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zapf A.; Jackstell R.; Rataboul F.; Riermeier T.; Monsees A.; Fuhrmann C.; Shaikh N.; Dingerdissen U.; Beller M. Practical synthesis of new and highly efficient ligands for the Suzuki reaction of aryl chlorides. Chem. Commun. 2004, 38–39. 10.1039/b311268n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapf A.; Sundermeier M.; Jackstell R.; Beller M.; Riermeier T.; Monsees A.; Dingerdissen U.. Nitrogen-containing monodentate phosphines and their use in catalysis. WO2004101581A2, 2004.

- Pickett T. E.; Roca F. X.; Richards C. J. Synthesis of Monodentate Ferrocenylphosphines and Their Application to the Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction of Aryl Chlorides. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 2592–2599. 10.1021/jo0265479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. F.; Johannsen M. New Air-Stable Planar Chiral Ferrocenyl Monophosphine Ligands: Suzuki Cross-Coupling of Aryl Chlorides and Bromides. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3025–3028. 10.1021/ol034943n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.-Y.; Choi M. J.; Fu G. C. A surprisingly mild and versatile method for palladium-catalyzed Suzuki cross-couplings of aryl chlorides in the presence of a triarylphosphine. Chem. Commun. 2001, 2408–2409. 10.1039/b107888g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovina N. V.; Domke L.; Shuklov I. A.; Spannenberg A.; Franke R.; Villinger A.; Börner A. New mono- and bidentate P-ligands using one-pot click-chemistry: synthesis and application in Rh-catalyzed hydroformylation. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 8809–8817. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.07.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster E. M.; Nisnevich G.; Botoshansky M.; Gandelman M. Synthesis of Novel Bulky, Electron-Rich Propargyl and Azidomethyl Dialkyl Phosphines and Their Use in the Preparation of Pincer Click Ligands. Organometallics 2009, 28, 5025–5031. 10.1021/om900545s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolhem F.; Johansson M. J.; Antonsson T.; Kann N. Modular Synthesis of ChiraClick Ligands: A Library of P-Chirogenic Phosphines. J. Comb. Chem. 2007, 9, 477–486. 10.1021/cc0601635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]