Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to describe the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and changes in demographic and phenotypic disease presentation in Otago, New Zealand.

Methods

This study was conducted at Dunedin Hospital and the study period was 1996–2013. Otago residents diagnosed with IBD were identified retrospectively from hospital lists using ICD-10 codes. Diagnosis, and place and date of diagnosis, were confirmed using medical notes and histology reports. Demographic, clinical and diagnostic data were recorded. Age-standardised incidence rates were estimated and trends over time assessed. Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess evidence for any changes in the distribution of disease location for Crohn's disease (CD) cases.

Results

The diagnosis of IBD was confirmed in 224 males and 218 females, and most were New Zealand European. Of the total number of confirmed IBD cases, 40.0% were ulcerative colitis (UC), 52.1% were CD and 7.9% were IBD unclassified. The age distribution illustrated bimodal peaks at 20–24 years and 65–69 years. Incidence rates varied from year to year, but there was no statistically significant change over the 18-year study period. The estimated age-standardised IBD incidence varied between 5.8/100,000 in 2006 and 29.8/100,000 in 2012. The incidence rates for UC and CD were 2.8/100,000 and 1.8/100,000, respectively, in 2006 and 6.3/100,000 and 21.8/100,000, respectively, in 2012. There were no significant phenotypic changes in CD patients over the study period.

Conclusions

The IBD incidence in Otago, New Zealand, is high compared to many other countries. Annual age-standardised incidence rates vary, highlighting the limitations of single-year incidence data.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, Epidemiology, Incidence, Inflammatory bowel disease, New Zealand, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a group of chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn's disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and IBD unclassified (IBDU) [1]. Specific causes of IBD are unknown; however, much evidence suggests a synergistic relationship between genetics, the external environment and the internal environment, e.g., the gut microbiota [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. IBD affects both males and females at similar rates, and the incidence peaks in young adults [8, 9]. A diagnosis of IBD necessitates lifelong treatment and monitoring, impacting heavily on patients' quality of life and the health system.

The incidence and prevalence of IBD is increasing worldwide [10]. Western societies of Celtic heritage have the highest reported prevalence, and rates are higher with increasing distance from the equator leading to a north-south [11, 12] and east-west gradient [13]. Most Asian countries have a low incidence, but there has been a recent rapid increase in rates [14]. In contrast, IBD rates are reported to be decreasing or at least plateauing in regions with previously high incidence rates [15, 16, 17].

The incidence of IBD in New Zealand is relatively high, although few studies have been published. Eason et al. [15] reported the mean annual incidence rates of CD and UC in Auckland were 1.75/100,000 and 5.4/100,000, respectively, in the 10-year period of 1969–1978. More recently, two separate studies conducted in the Canterbury region reported the WHO age-standardised IBD incidence rate was 25.2/100,000 in 2004 [16], increasing approximately 1.6-fold to 39.5/100,000 in 2014 [17]. The reasons for the increase remain elusive [16, 17].

As the epidemiology of IBD is changing, the description of IBD incidence over time remains important [8, 14, 18]. This study sought to investigate whether the IBD incidence in the Otago region of New Zealand had changed between 1996 and 2013, and to assess whether the phenotypic presentation of IBD had changed over this 18-year period.

Methods

Study Design

This study was conducted at Dunedin Hospital, the only secondary/tertiary referral centre and the only main regional hospital for the Otago region, New Zealand. The resident population in the Otago area increased from 176,295 in 1996 to 184,893 in 2013 [19]. In 2013, most Otago residents self-identified as European (89.1%), with fewer Maori (7.5%), Asian (5.2%), Pacific Island (2.0%) or other ethnicities (2.2%) [19] (selecting more than one ethnicity is possible in the New Zealand census). Throughout New Zealand, most health care is provided by the public sector. In Dunedin, gastroenterology services can be accessed in the public or, to a limited degree, in the private sector. IBD cases needing hospital admission or interventions are usually referred to Dunedin Hospital. This study included patients who accessed the public sector.

Case Ascertainment

A case was defined as a patient with an IBD diagnosis according to accepted criteria (including colonoscopy, histology and clinical presentation) who resided within the Otago District Health Board area at the time of diagnosis. Diagnoses had to be upheld after follow-up for the case to be included. A list of potential cases of IBD for the years 1996–2013 was compiled using the following strategies:

1. Hospital event data (which included day cases for procedures like colonoscopies, and inpatient care). Each individual in New Zealand is assigned a unique National Health Index (NHI) number. Approximately 5% of New Zealanders do not have a unique NHI number [20]. Following a hospital event, reasons for admission as a day case or as an inpatient are coded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). For this study, a list of NHI numbers for day cases or inpatients discharged from Dunedin Hospital with ICD codes for CD (K50 and 555), UC (K51 and 556) and IBDU (K52.3 and 558.9) for the 1996–2013 period was obtained. For each individual only their first-ever identified ICD code for CD, UC or IBDU was used.

2. Dunedin Hospital Gastroenterology Department (including outpatient clinics). Copies of outpatient clinic letters and endoscopy reports from the Gastroenterology Department were searched for names of IBD-associated medications, operations, investigations and the following terms: “colitis,” “distal colitis,” “ulcerative colitis,” “proctitis,” “Crohn,” “Crohn's Disease” and “terminal ileitis.” The NHI number of any suspected case was recorded.

3. EpiSoft database. The Dunedin Hospital Gastroenterology Department contributes data to an IBD-specific database (EpiSoft, Sydney, NSW, Australia). All IBD cases diagnosed in the department have been included in this database since 2012.

4. Paediatric gastroenterologist. Children with suspected IBD are referred to the paediatric gastroenterology service at the neighbouring Christchurch Hospital tertiary referral centre. A list of NHI numbers for all known paediatric cases of IBD diagnosed in Otago residents was provided.

For each suspected case, colonoscopy and histology reports and gastroenterology clinical notes were reviewed to confirm a diagnosis of IBD, the year of diagnosis and the address at the time of diagnosis. All cases seemingly diagnosed by barium enema, small bowel meal or other radiological investigation only were excluded.

For each confirmed case, demographic (date of birth, gender and ethnicity) and relevant clinical data were extracted from the medical records and entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Phenotyping data for UC and CD were extracted from the colonoscopy and histology reports used to make a diagnosis of IBD, as well as from radiological staging examinations. The phenotypic presentation was classified as CD or UC using the Montreal classification [21].

Statistical Methods

The list of confirmed IBD cases was analysed together, then grouped by CD, UC and IBDU. The list for each diagnosis was then grouped by the year of diagnosis and by 5-year age groups. Census data for the Otago District Health Board area were obtained for the years 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2013 (the 2011 census was delayed because of the Christchurch earthquake) [19]. Linear interpolation was used to estimate the population by 5-year age groups for the years between census years.

Annual 5-year age-specific incidence rates for each of the four diagnostic groups were calculated. Annual age-standardised incidence rates were calculated using the World Health Organisation (WHO) standard population. Linear regression models were used to explore any changes in age-standardised rates, with Durbin-Watson tests used to identify evidence for autocorrelation. Linear regression models – with Newey-West standard errors, where there was evidence of autocorrelation – were used to examine changes in the age-standardised rates for each diagnostic group using “year” as a continuous variable to identify linear trends.

CD, UC and IBDU were examined in a single model to determine whether there was any evidence that their rates were changing differently over the study period through a year-type interaction, as well as estimating type-specific rates of change. Total IBD was examined in a separate model. Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess evidence for any changes in the distribution of location for CD cases (ileal, colonic, ileocolonic or upper gastrointestinal).

All statistical modelling was performed using Stata 13.1, and a two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all cases.

Results

Case Ascertainment

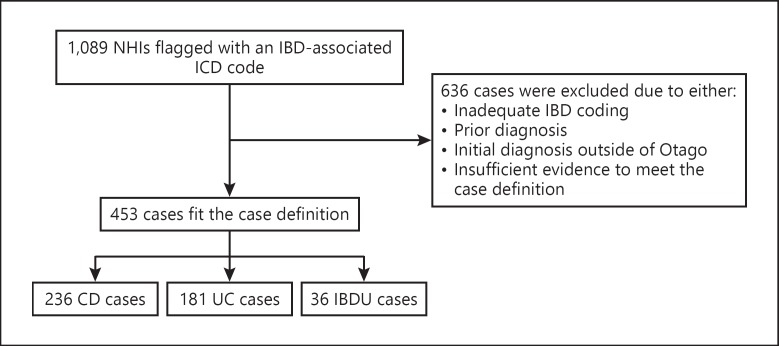

Of 1,089 IBD-coded cases, 453 (41.6%) new cases of IBD were confirmed among Otago residents for the period 1996–2013 (Fig. 1). Cases were excluded if there was evidence of a diagnosis prior to 1996, if the diagnosis had been made prior to residence in Otago or if there was insufficient evidence to meet the case definition.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of ascertainment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cases in Otago from 1996 to 2013. CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBDU, IBD unclassified.

Case Description

Of the 453 confirmed IBD cases, 52.1% were CD, 40.0% were UC and 7.9% were IBDU. Slightly fewer males (46%) than females had CD, while the opposite was observed for UC (57% males). Almost all cases (97.1%) were recorded as being New Zealand European (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data on the patients diagnosed with IBD in the Otago region, New Zealand, 1996–2013

| IBD overall (total n = 453) | CD (total n = 236) | UC (total n = 181) | IBDU (total n = 36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 233 (51.4) | 114 (48.3) | 101 (55.8) | 18 (50) |

| Female | 220 (48.6) | 122 (51.7) | 80 (44.2) | 18 (50) |

| Median age, years | ||||

| Male/female | 34/34 | 26/32 | 42/38 | 41/38 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| New Zealander/European | 440 (97.1) | 229 (97.0) | 177 (97.8) | 34 (94.4) |

| Maori | 8 (1.8) | 4 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (5.6) |

| Other | 5 (1.1)1 | 3 (1.3)2 | 2 (1.1)3 | 0 (0) |

Values are n (%) unless specified otherwise. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBDU, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified.

Middle Eastern (3), Asian (1) and Pacific Island (1).

Middle Eastern (2) and Asian (1).

Middle Eastern (1) and Pacific Island (1).

IBD Incidence

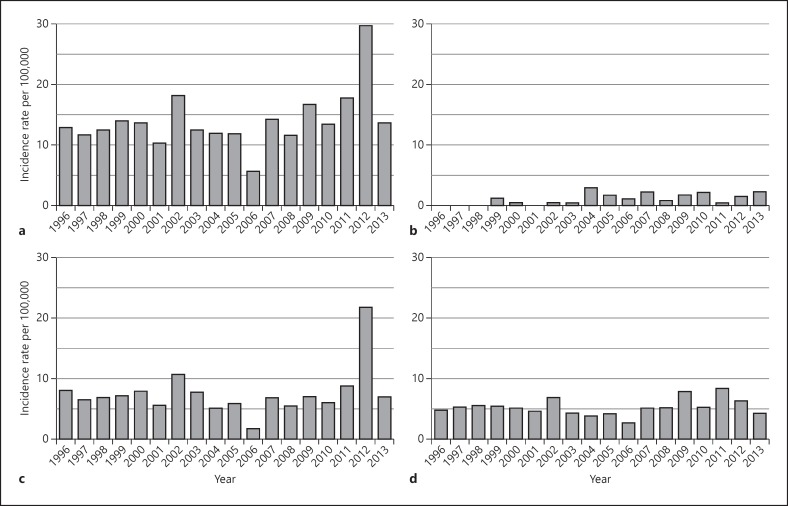

The annual age-standardised IBD incidence varied during the 18-year period, with the lowest incidence (5.8/100,000) in 2006 and the peak incidence (29.8/100,000) in 2012. The mean annual age-standardised incidence across the study period was 7.6/100,000 for CD, 5.4/100,000 for UC and 1.1/100,000 for IBDU (Fig. 2). Overall there were no statistically significant changes in incidence for CD (p = 0.110), UC (p = 0.646), IBDU (p = 0.323) or total IBD (p = 0.106) between 1996 and 2013. There were large annual fluctuations in IBD incidence over the 18 years, with a standard deviation of 3.7/100,000 per year.

Fig. 2.

Age-standardised incidence rates of IBD (a), IBDU (b), CD (c) and UC (d) in Otago 1996–2013. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBDU, IBD unclassified.

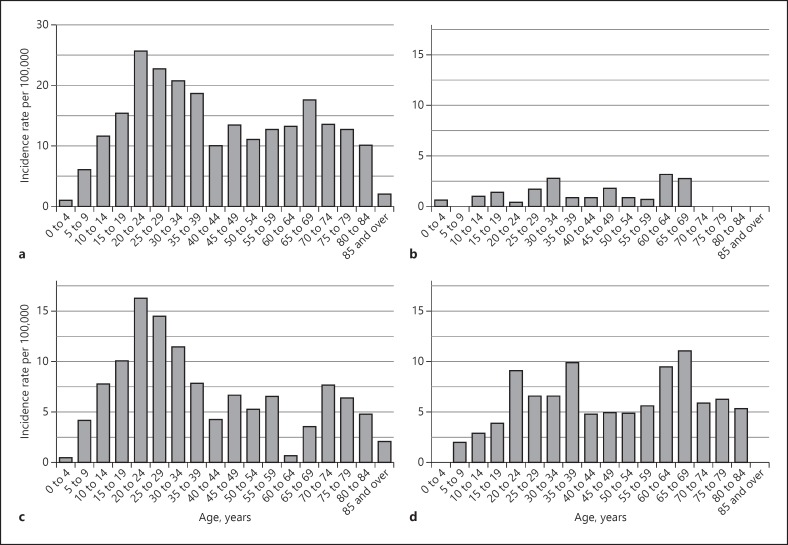

The age distribution of IBD cases was similar between the sexes. CD or UC among both sexes was most commonly diagnosed between 20 and 24 years, with 16% of all patients aged 20–24 years at diagnosis (Fig. 3). About half (52.4%) of all patients were aged 15–39 years at diagnosis. A second peak in UC incidence was observed in the 60- to 69-year age group, with a smaller second peak for CD in the 70- to 74-year age group (Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Age distribution of IBD (a), IBDU (b), CD (c) and UC (d) cases in Otago 1996–2013. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBDU, IBD unclassified.

Overall, almost half (43.5%) of the CD patients had ileocolonic disease, with about one-third (31.5%) having colonic disease and about one-quarter ileal disease (23.6%). A small proportion (14.4%) had perianal involvement, and the number of patients with perianal involvement in any one year varied from none in 1998, 2011 and 2013 to 5 in 2012. The proportion of CD patients diagnosed with L1, L2 and L3 disease did not change significantly over the 18-year study period (p = 0.257).

Discussion

This study describes for the first time the annual IBD incidence and changes in phenotypic presentation in the Otago region, New Zealand, over an 18-year time period. Overall, we observed an upward trend in IBD incidence, as well as in CD and UC, between 1996 and 2013, but this was not statistically significant. The most notable finding was the overall variation in incidence over the 18-year study period. The highest incidence of IBD was in 2012, peaking at 29.8 cases per 100,000, while a low rate was observed in 2006 (5.8/100,000). These observations may be explained by incomplete case finding, misclassification of the year of diagnosis, possible deficiencies in hospital medical record coding practise or variation in the number of tertiary students moving to the Otago region for university study whose disease onset occurred during their university years. Another possibility is that people previously resident in Christchurch at the time of the 2011 earthquake may have relocated to Dunedin. As this was a stressful event and stress can trigger IBD [22], this may in part explain the high number of cases in 2012. Although these annual fluctuations in incidence are not readily explained, they do highlight the importance of looking at incidence rates over time rather than drawing conclusions from a snapshot in time, and it questions the validity of using routine hospital data to monitor relatively uncommon diseases, at least at a regional level. Additional databases such as those recording pharmaceuticals may have increased our case detection, as has been observed elsewhere [23].

Worldwide, overall rates of IBD continue to increase, although there is variation in incidence rates within and between countries. In recent years, different studies from around the world have reported annual IBD incidence rates were increasing, plateauing or even decreasing [14, 17, 24]. While Asia-based population studies continue to show increasing IBD incidence rates, two recent Eastern Canadian studies found statistically significant reductions in IBD incidence among populations with previously high rates [11, 13, 14, 25, 26], whereas two separate Danish studies, conducted during a time period similar to that of our study, both observed increases in CD incidence and UC incidence in both men and women [27, 28]. Our study was relatively small, but the overall upward trend in IBD incidence, while not statistically significant, suggests that the IBD incidence in the Otago region of New Zealand is probably increasing.

The IBD incidence rates for the Otago region appear relatively low compared with those reported in the recent New Zealand studies in the neighbouring Canterbury region [16, 17]. In 2004, Gearry et al. [16] found that the age-standardised CD and UC incidence rates in the Canterbury region were 16.3 and 7.5 per 100,000, respectively. For the same year, the CD and UC incidence rates in Otago were considerably lower, at 5.1 and 3.9 per 100,000. In 2014, the CD and UC incidence rates in Canterbury had increased to 26.4 and 12.6 per 100,000, respectively [17], which was higher than the peak rates reported in 2012 in our study. This marked difference in incidence rates between two neighbouring regions with similar population characteristics, and an apparently comparable environment, is surprising but might be explained by the relatively small numbers and the year-to-year variation in annual IBD incidence rates that our 18-year study demonstrated. Another possible explanation is that we did not identify all cases during the study period. Further, it is possible that not all true cases were accurately coded by the hospital medical records, as has been described for other conditions [29]. Despite these apparent differences, the Otago and Canterbury studies show that New Zealand has IBD incidence rates at or above the 60th percentile of studies from around the world, with the CD incidence higher than that of UC and ranking in the 80th to 100th quintile [8].

The IBD rates were similar for males and females in our study, and the age distributions for both CD and UC were consistent with international observations [8]. We found a low IBD incidence among Maori, the indigenous population of New Zealand, which is consistent with other New Zealand studies [16, 30]. Although Maori account for approximately 7% of the Otago population [19], only 1.7% of the IBD cases over the past 18 years identified with this ethnic group. We identified only 1 case of IBD in a resident of Asian heritage, suggesting a low incidence of IBD amongst Asian people, which is consistent with a low reported incidence of about 1 case per 100,000 in Asian countries [5].

We observed that almost half (43.5%) of the patients with CD had ileocolonic disease. This proportion is similar to the approximately 45% reported in studies from Asia, Australia and New Zealand, but almost twice as much as that reported from European countries (25%) [10, 12]. We also observed that disease presentation at diagnosis did not change significantly over the study period, which has been reported elsewhere [31]. However, an increase in the proportion of cases with L3 disease location over time was reported between 2007/2008 and 2010/2011 in the same area of neighbouring Australia, but the number of cases with complete disease location data was relatively small [24]. Nevertheless, this observation may be real, and although there is no clear explanation for this increase, investigation of the length of the small intestine has proven problematic and spurred the rapid evolution and introduction of methods for visualising the small intestine with minimal invasion. The introduction of magnetic resonance enterography [32], computed tomographic enteroclysis [33] and/or wireless capsule endoscopy [34, 35], for example, as part of common practise might, in part, be accountable for this finding.

Age and disease phenotype at diagnosis in Otago were compared with observations from other geographical regions [10, 12]. Our observations in Otago were similar to recent reports from the neighbouring Canterbury region [17]. The age at diagnosis was similar in European and Asian countries, and the location of inflammation in UC patients was similar in the Asian and New Zealand studies [10, 12]. In Europe, 41–46% of UC cases were left-sided, compared with 15% in our Otago study [10]. For CD, 60–70% of cases were classified as B1 in New Zealand, Europe and Asia, which is lower than the 88% reported from Australia [10, 12]. Among CD cases in Otago, 28.7% involved a stricturing phenotype, which was higher than the rates reported in Western and Eastern European (slightly less than 20%), Australasian (10%) and Asian (17%) studies [10, 12].

As we used a strict case definition, it is highly unlikely that we overestimated the IBD incidence rates in Otago. Underestimation is more likely, as we excluded cases of IBD which appeared to be diagnosed using barium enemas or via other radiological means only; our case definition required a histological and/or endoscopic verification of the diagnosis. It is possible that a small number of cases who had a colonoscopy at a small rural hospital in the Otago region and were not admitted to Dunedin Hospital or seen at the Dunedin Hospital Gastroenterology Department at any stage would not have been identified, thereby further contributing to an underestimate of incidence rates. Although we did not capture private practice cases, private practice is small in Otago and the number of such cases is likely to be negligible. Finally, some clinical phenotype data were missing from the medical records.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the IBD incidence rates in the Otago region, New Zealand, are amongst the highest in the world, but lower than the rates reported for the neighbouring northern Canterbury region in 2004 and 2014. Although examining the annual incidence over almost two decades provided a more comprehensive description, our strict case definitions and possible hospital medical record coding errors may have led to an underestimation of the true IBD incidence rates.

Statement of Ethics

This study had ethical approval from the University of Otago Human Health Ethics Committee (Ref. No. HD14/63) that complies with the Declaration of Helsinki standards.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Medical Records Department at Dunedin Hospital for their assistance throughout the study. This research was funded through the Gastroenterology Unit at Dunedin Hospital and the GutHealthNetwork of the University of Otago.

References

- 1.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahid SS, Minor KS, Soto RE, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1462–1471. doi: 10.4065/81.11.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruel J, Ruane D, Mehandru S, Gower-Rousseau C, Colombel JF. IBD across the age spectrum: is it the same disease? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:34–98. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Limbergen J, Radford-Smith G, Satsangi J. Advances in IBD genetics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:372–385. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz M, Butt AG. Is the north to south gradient in inflammatory bowel disease a global phenomenon? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:34–447. doi: 10.1586/egh.12.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, et al. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588–597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bitton A, Vutcovici M, Patenaude V, Sewitch M, Suissa S, Brassard P. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Québec: recent trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1770–1776. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-Pacific Crohn's and Colitis Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158–165. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitton A, Vutcovici M, Patenaude V, Sewitch M, Suissa S, Brassard P. Decline in IBD incidence in Québec: part of the changing epidemiologic pattern in North America. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1782–1783. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leddin D, Tamim H, Levy AR. Decreasing incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in eastern Canada: a population database study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eason RJ, Lee SP, Tasman-Jones C. Inflammatory bowel disease in Auckland, New Zealand. Aust NZ J Med. 1982;12:125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1982.tb02443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gearry RB, Richardson A, Frampton CM, Collett JA, Burt MJ, Chapman BA, et al. High incidence of Crohn's disease in Canterbury, New Zealand: results of an epidemiologic study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:936–943. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000231572.88806.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su HY, Gupta V, Day AS, Gearry RB. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Canterbury, New Zealand. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2238–2244. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turunen P, Kolho KL, Auvinen A, Iltanen S, Huhtala H, Ashorn M. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Finnish children, 1987–2003. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:677–683. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Census data and reports Statistics New Zealand. 2014. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-culture-identity/ethnic-groups-NZ.aspx (cited 23 November 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health National Health Index questions and answers. 2018 www.health.govt.nz/our-work/health-identity/national-health-index/nhi-information-health-consumers/national-health-index-questions-and-answers#bwhatis (updated 9 January 2018; cited 11 July 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19((suppl A)):5a–36a. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1481–1491. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Mack DR, Nguyen GC, Marshall JK, Gregor JC, et al. Validation of international algorithms to identify adults with inflammatory bowel disease in health administrative data from Ontario, Canada. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:887–896. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Studd C, Cameron G, Beswick L, Knight R, Hair C, McNeil J, et al. Never underestimate inflammatory bowel disease: high prevalence rates and confirmation of high incidence rates in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:81–86. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuang CH, Lin SH, Chen CY, Sheu BS, Kao AW, Wang JD. Increasing incidence and lifetime risk of inflammatory bowel disease in Taiwan: a nationwide study in a low-endemic area 1998–2010. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2815–2819. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000435436.99612.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J, Ng SC, Lei Y, Yi F, Li J, Yu L, et al. First prospective, population-based inflammatory bowel disease incidence study in mainland of China: the emergence of “Western” disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1839–1845. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828a6551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lophaven SN, Lynge E, Burisch J. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1980–2013: a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:961–972. doi: 10.1111/apt.13971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nørgård BM, Nielsen J, Fonager K, Kjeldsen J, Jacobsen BA, Qvist N. The incidence of ulcerative colitis (1995–2011) and Crohn's disease (1995–2012) – based on nationwide Danish registry data. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1274–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, Parsons GA, Nilsson CI, Alibhai A, et al. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1424–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yap J, Wesley A, Mouat S, Chin S. Paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2008;121:19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, Winther KV, Borg S, Binder V, et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:481–489. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castiglione F, Mainenti PP, De Palma GD, Testa A, Bucci L, Pesce G, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of small bowel Crohn's disease: direct comparison of bowel sonography and magnetic resonance enterography. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:991–998. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802b87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sailer J, Peloschek P, Schober E, Schima W, Reinisch W, Vogelsang H, et al. Diagnostic value of CT enteroclysis compared with conventional enteroclysis in patients with Crohn's disease. AJR Am J f Roentgenol. 2005;185:1575–1581. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilangovan R, Burling D, George A, Gupta A, Marshall M, Taylor SA. CT enterography: review of technique and practical tips. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:876–886. doi: 10.1259/bjr/27973476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Gurudu SR, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, et al. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with non-stricturing small bowel Crohn's disease. Am J f Gastroenterol. 2006;101:954–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]