Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the impact of religiosity on subjective life satisfaction and perceived academic stress in undergraduate pharmacy students.

Materials and Methods:

This 1-month descriptive study focused on pharmacy students of a public-sector university and used three survey questionnaires. The questionnaires included: the Duke University Religion Index to assess religiosity, Subjective Happiness Scale for documenting subjective happiness of life, and Perceived Stress Scale for evaluation of perceived stress due to academic load. The data were analyzed through Statistical Package for Social Services software, version 22. Chi-square test, Pearson’s correlation, and logistic regression were used. Study was exempted from ethical review.

Result:

Subjective happiness was positively (+) correlated with non-organized religious activity and intrinsic religiosity (P < 0.01). Perceived stress score reported negative (–) correlation with organized religious activity (P < 0.05). Female students appeared more stressed (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Religiosity may enhance life satisfaction and may relieve academic stress in pharmacy students.

KEYWORDS: Academic stress, pharmacy, religiosity, subjective life satisfaction, undergraduate students

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacy education has been identified as one among the health disciplines that may promote academic stress in students because of its exhaustive nature of study.[1,2] Stress negatively affects the mental health of the students resulting in stress-related disorders, low subjective life satisfaction, and poor academic performance.[3,4,5,6] According to the World Health Organization, stress would become a major cause of mortality by 2020.[7,8]

Pharmacy training is a rigorous and strenuous endeavor, which takes place in a competitive vocational environment. This includes taught lectures, clerkships, and residency in health-care settings that predispose undergraduate students to high levels of stress.[9,10,11] Stress screening has been considered in pharmacy students by some accreditation bodies.[12] Studies also report a high prevalence of self-medication of antidepressants to treat stress-resultant depression and anxiety among undergraduate pharmacy students.[13,14]

There is a plethora of evidence regarding the determinants of stress in university students, which include academic-related matters, environmental factors, and personal events.[5,15] Academia-related stress is most frequently reported.[3] It is most commonly reported in undergraduates especially in pharmacy students.[16,17,18] Several coping strategies have been suggested, however, none provides satisfactory solution.[19,20]

The role of religiosity in physical and mental health is well established.[21,22] Previous studies conducted by Al Rasheed et al.,[7] Al-Shagawi et al.,[8] and Albusalih et al.,[23] reported high academic stress and stress-related self-medication practice in pharmacy students of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia. This study evaluated the impact of religiosity on subjective life satisfaction and academic stress in pharmacy students enrolled in this university.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A descriptive study was conducted in December 2017 (1 month) to evaluate the impact of religiosity on subjective life satisfaction and perceived academic stress in pharmacy students.

Subjects and site

Pharmacy students studying in 2nd–5th year of Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree program, at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University located in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, were included in the study. Students enrolled in preparatory year (1st year) and those in their 6th year of study were not included. Students in 1st year are considered as prospective students and study a variety of allied health courses. They do not come under the jurisdiction of a pharmacy college. Students of 6th year of study are pharmacy residents and are stationed in hospitals. Students who did not wish to participate were left out.

Sampling strategy and sample size calculation

Convenient sampling strategy was used. The total number of pharmacy students enrolled at the time of study (December 2017) was 322. The sample size was calculated by an online sample size calculator using this figure, with the margin of error at 5%, and confidence level of 95%. The recommended sample size obtained was 175. A total of 242 respondents participated in the study.

Study questionnaires

The study used the following questionnaires separately as sections: the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL)[24] to assess the religiosity, Subjective Happiness Scale[25] for the assessment of subjective happiness of life, and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) for documenting perceived stress because of academic load.[26]

Section one included questions related to demographic characteristics such as age, marital status, gender, year of study, smoking status, any diagnosed physical or mental disorder, monthly family income status, grade point average (GPA), and academic expectations, whereas second section incorporated DUREL that contained five items related to religiosity. Subjective Happiness Scale formed section three of the questionnaire and it contained four items related to subjective happiness of life. PSS was included in section four that contained 10 questions regarding perceived stress. Items related to religiosity included questions on frequency of engagement in organized and unorganized religious activities. Items related to subjective happiness investigated the degree of happiness in relation to various life events, and items related to PSS measured students’ perceived stress because of personal, academic, and social factors. All tools measured students’ response on a numeric rating scale. All psychometric tools used, that is, DUREL, Subjective Happiness Scale, and PSS were previously validated.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed through IBM Statistical Package for Social Services (SPSS) statistics for Windows, version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Chi-square (χ2) test, Fisher’s exact test, and Pearson correlation were used as required. A value of P less than 0.05 was considered significant. The continuous variable was expressed as mean (X) and standard deviation (SD), categorical variables were expressed in sample count (N) and percentage (%), and the associations between variables were expressed in χ2 values and P value. The correlation results were interpreted in terms of correlation coefficient (ρ) and P value. Analysis of logistic regression was expressed as odds ratio (OR), probability (%), and relative risk (RR).

Ethics review and consent

The students were briefed about the study. A verbal consent was sought before handing the questionnaire. The study was exempted from review.

RESULTS

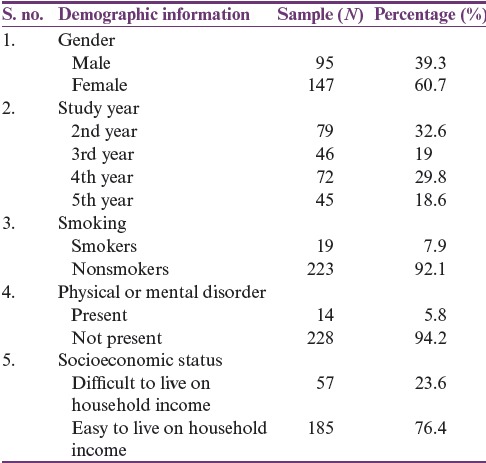

Of the total 322 pharmacy students, 242 responded to the survey. The response rate was 75.2%. Most of them were female students (n = 147, 60.7%) with a male:female (M/F) ratio of 1.55. The mean age of students was 20.76 years (SD, 1.3). The study incorporated responses from students studying in 2nd–5th year of PharmD. More than 90% of the students did not smoke and had no physical or mental illness. The mean GPA obtained from students was 4.3 of 5. A quarter of students (n = 57, 23.6%) highlighted that they find it difficult to live on monthly family income. The demographic information is tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information

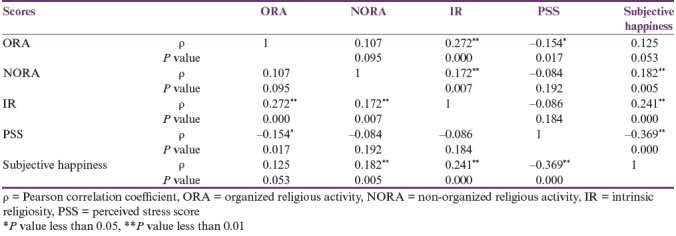

The mean score for intrinsic religiosity (IR) was 12.9 (SD, 2.5), for subjective happiness was 17.5 (SD, 3.8), and for PSS was 19.8 (SD, 5.0). Organized religious activity (ORA) was positively correlated with IR; however, a statistically significant (P < 0.02) negative correlation existed between ORA and PSS. The correlation coefficient was moderate (–0.154). Non-organized religious activity (NORA) had a significant (P < 0.01) and a moderate positive correlation with IR (+0.172) and subjective happiness (+0.182). IR was positively correlated (+0.241) with subjective happiness with statistical significance (P < 0.01). The same was negatively correlated with PSS (–0.137) with statistical significance (P < 0.05). PSS was negatively correlated with subjective happiness (–0.369) with a P value less than 0.01. The correlation is tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation between variables and their significance

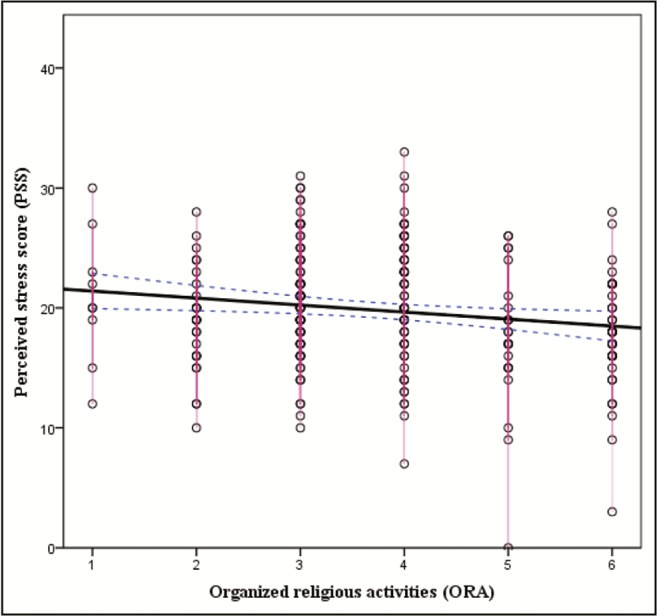

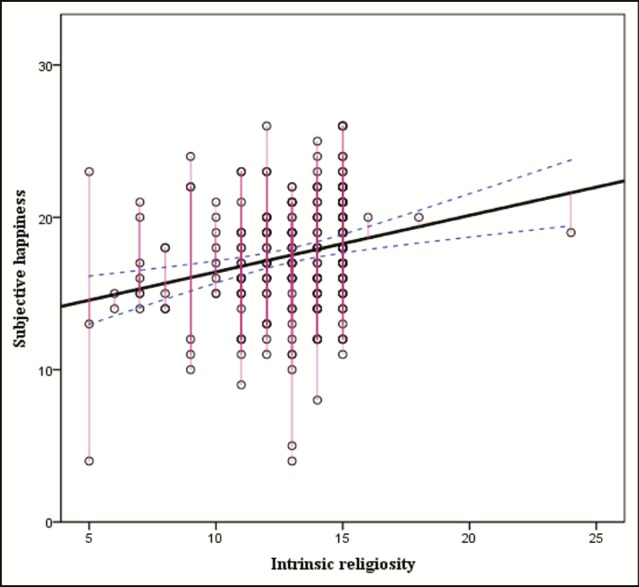

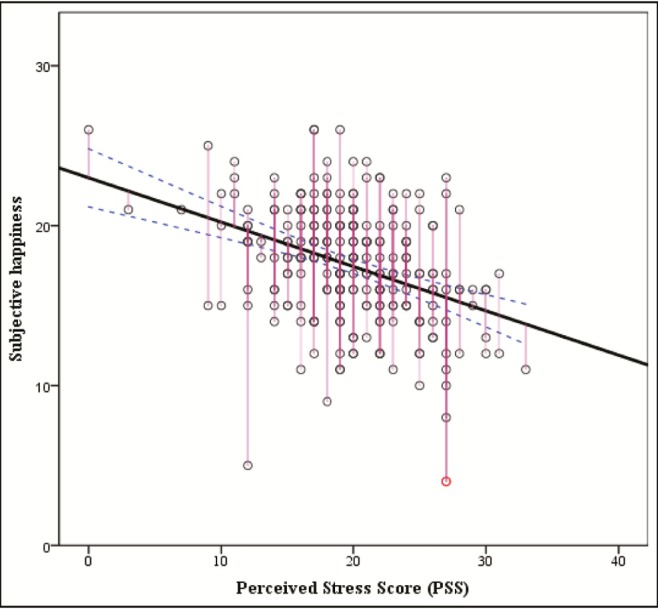

Figure 1 denotes relationship between PSS and ORA. A downward trend was observed in PSS as ORA score increased. Similarly, in Figure 2, an inclining trend was observed between subjective happiness score and IR. The subjective happiness score increased with an increase in IR score. Figure 3 reported a downward trend between subjective happiness and PSS. Subjective happiness decreased as PSS increased among respondents. The dotted lines represent mean value, whereas black line is correlation coefficient. The red circles are individual scores.

Figure 1.

Correlation between organized religious activity and Perceived Stress Scale

Figure 2.

Correlation between subjective happiness and intrinsic religiosity

Figure 3.

Correlation between subjective happiness and Perceived Stress Scale

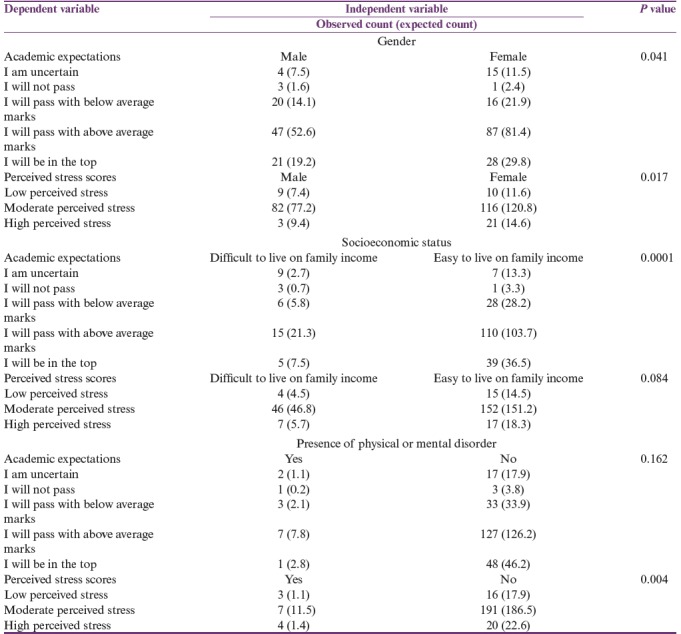

The association between gender and academic expectations was significant (P = 0.041) with χ2 value reported at 9.82. The association between gender and PSS score was significant (P = 0.017) with χ2 value reported at 8.129. No cell had expected count less than five, therefore the results are reliable. Moreover, the strength was weak to moderate, that is, phi reported at 0.184. Furthermore, association between expectation and socioeconomic status of students was significant (P = 0.0001) with χ2 value reported at 23.117 with moderate to strong effect, that is, phi value = 0.368. A significant association (P = 0.0162) was also reported between PSS score and physical and mental health profile of students with χ2 value reported at 9.566 and moderate effect, that is, phi reported at 0.209. The association of PSS score with socioeconomic status and health profile with academic expectations was not statistically significant (P < 0.05). The cross tabulation is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cross tabulation between dependent and independent variables

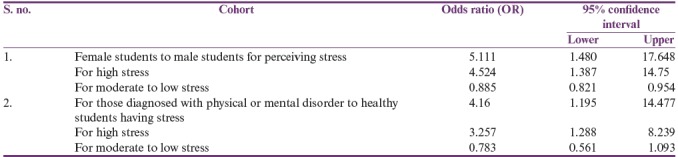

The probability of perceiving academic stress for female students as compared to male students was 83.6% (OR, 5.1). The RR for female students having a high perceived stress was reported at 4.5. Similarly, probability of perceiving academic stress for students who have any physical or mental disorder was reported at 80.6% (OR, 4.16) with a RR of 3.257 for being in high stress. The OR and risk estimates are tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Odds ratio and risk estimate

DISCUSSION

Studies have reported high levels of stress in students studying health-related subjects.[27,28] It affects their happiness, quality of life, and academic performance.[29,30] Their stress perception and response, coping strategies, and resistance, require an in-depth insight. This may help in devising new strategies and improving the existing approaches.[31] We found that religious activity or religiosity showed a positive effect on life satisfaction and academic stress reduction in pharmacy students.

Happiness is a term used for positive subjective experiences.[25,32,33] It consists of three components: experiencing positive emotion, being engaged in life activities, and finding a sense of purpose or meaning.[34] In general, it is a combination of positive emotions and meaningfulness. These attributes contribute to student learning process.

Stress is a complex concept and falls into three categories: stimulus, response, and interaction.[35] It occurs when straining exceeds an individual’s adaptive capacity. It may be caused by life transitions of adolescence, the requirements of a new program, the demands of higher education, and college life in young adults.[36] Evidence suggests that those who struggle with adjustment to college life are at risk for depression, anxiety, physical health problems, and negative health behavior.[37,38,39]

DUREL contains the first question about ORA, the second about NORA, and the final three regarding IR.[25] Our study showed a statistically significant positive correlation of NORA and IR with subjective happiness. But ORA failed to show such relationship with the same. This could be interpreted as: NORA and IR may reduce anxiety and increase subjective happiness in pharmacy students.[40] NORA and IR are concerned with personal religious coping or use of own cognitive and behavioral techniques in the face of stressful life events.[41] A successful management of problems in life is the basis of subjective happiness. Studies have proved this relationship in several domains.[42]

A negative correlation of ORA, NORA, and IR was observed with perceived stress in our students. This negative correlation is statistically significant in case of ORA only. This is because religious event may be considered as a social activity, and a research indicated that social relationship is one of the most important contributors to stress reduction.[43] Therefore, ORA had the most significant effect on stress reduction in our sample. This finding is also in line with previous studies.[44,45] Religion may promote happiness and reduce stress as it gives people a sense of purpose and serves as a resource for coping with negative life experiences and existential fears.

Apart from religiosity, cross tabulation reported statistically significant association between academic expectation and stress in female students. A study published by Hamaideh[46] in 2012 reported that female students had a higher perception of stress, conflicts, and emotional reactions to stressors; however, male students had higher behavioral and cognitive reaction. Levesque and Roger[47] in 2011 reported gender inequality in academic expectation and stress. However, it was independent to religion.[48]

Our study suggests that religion may be considered as life satisfaction–enhancing and stress-relieving tool. This concept is also supported by several studies conducted in undergraduate students.[49,50,51] An intervention based on this concept may be possible because of high interest of students in spirituality.[52] Psychology of religion reveals that religious coping styles are conceptually distinct from nonreligious coping styles and uniquely influence psychosocial health above and beyond the effects of nonreligious coping.[53]

Our results also negate the findings of few studies that showed adverse effect of religiosity on life satisfaction and contributed to high stress in students.[52,53,54] However, factors that differentiated those studies with ours were the age group of the students, mixed religious affiliations as well as cultural and societal influences. Therefore, our findings apply to this population and may not be exhaustive.

CONCLUSION

Religious activity was observed to have a positive effect in enhancing life satisfaction and reducing stress in pharmacy students in our study and may prove helpful in improving academic performance.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomathi KG, Ahmed S, Sreedharan J. Causes of stress and coping strategies adopted by undergraduate health professions students in a university in the United Arab Emirates. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:437–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assaf AM. Stress-induced immune-related diseases and health outcomes of pharmacy students: a pilot study. Saudi Pharm J. 2013;21:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher CT, Mehta Amil NV, Selvan R, Mirza IB, Radia P, Bharadia NS, et al. Perceived stress levels among undergraduate pharmacy students in the UK. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6:437–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch JD, Do AH, Hollenbach KA, Manoguerra AS, Adler DS. Students’ health-related quality of life across the preclinical pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73:147. doi: 10.5688/aj7308147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall LL, Allison A, Nykamp D, Lanke S. Perceived stress and quality of life among doctor of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:137. doi: 10.5688/aj7206137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Dubai SA, Al-Naggar RA, Alshagga MA, Rampal KG. Stress and coping strategies of students in a medical faculty in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2011;18:57–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Rasheed F, Naqvi AA, Ahmad R, Ahmad N. Academic stress and prevalence of stress-related self-medication among undergraduate female students of health and non-health cluster colleges of a public sector university in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2017;9:251–8. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_189_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Shagawi MA, Ahmad R, Naqvi AA, Ahmad N. Determinants of academic stress and stress-related self-medication practice among undergraduate male pharmacy and medical students of a tertiary educational institution in Saudi Arabia. Trop J Pharm Res. 2017;16:2997–3003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbas A. The catch-22 of pharmacy practice in Pakistan’s pharmacy education. Pharmacy. 2014;2:202–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbas A. Evidence based improvements in clinical pharmacy clerkship program in undergraduate pharmacy education: the evidence based improvement (EBI) initiative. Pharmacy. 2014;2:270–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naqvi AA. Evolution of clinical pharmacy teaching practices in Pakistan. Arch Pharma Pract. 2016;7:26–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.qAccreditation council for pharmacy education [homepage on the internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree [updated 2006] [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 1]. Available from: http://www.acpe-accredit.org .

- 13.Abbas A, Ahmed FR, Yousuf R, Khan N, Nisa ZN, Ali SI, et al. Prevalence of self-medication of psychoactive stimulants and antidepressants among undergraduate pharmacy students in twelve Pakistani cities. Trop J Pharm Res. 2015;14:527–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbas A, Rizvi SA, Hassan R, Aqeel N, Khan M, Bhutto A. The prevalence of depression and its perceptions among undergraduate pharmacy students. Pharmacy Education. 2015;15:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doble N, Supriya MV. Student life balance: myth or reality? Int J Edu Manag. 2011;25:237–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey LA, Drew S, Smith M. York, UK: Higher Education Academy; 2006. The first year experience: a review of literature for the higher education academy. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun SH, Zoriah A. Assessing stress among undergraduate pharmacy students in University of Malaya. Indian J Pharm Educ. 2015;49:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frick LJ, Frick JL, Coffman RE, Dey S. Student stress in a three-year doctor of pharmacy program using a mastery learning educational model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:64. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garber MC. Exercise as a stress coping mechanism in a pharmacy student population. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81:50. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holton MK, Barry AE, Chaney JD. Employee stress management: an examination of adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies on employee health. Work. 2015;53:299–305. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenig H, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:49–55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albusalih FA, Naqvi AA, Ahmad R, Ahmad N. Prevalence of self-medication among students of pharmacy and medicine colleges of a public sector university in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy. 2017;53:51. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy5030051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions. 2010;1:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46:137–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81:354–73. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConville J, McAleer R, Hahne A. Mindfulness training for health profession students-the effect of mindfulness training on psychological well-being, learning and clinical performance of health professional students: a systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Explore (NY) 2017;13:26–45. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart SM, Lam TH, Betson CL, Wong CM, Wong AM. A prospective analysis of stress and academic performance in the first two years of medical school. Med Educ. 1999;33:243–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarid O, Anson O, Yaari A, Margalith M. Academic stress, immunological reaction, and academic performance among students of nursing and physiotherapy. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:370–7. doi: 10.1002/nur.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies EB, Morriss R, Glazebrook C. Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e130. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diener E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000;55:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5:164–72. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seligman MEP. New York: Atria Paperback; 2002. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartlett D. Stress perspectives and processes. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyson R, Renk K. Freshmen adaptation to university life: depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:1231–44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell S, Lee C. Does timing and sequencing of transitions to adulthood make a difference? Stress, smoking, and physical activity among young Australian women. Int J Behav Med. 2006;13:265–74. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1303_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E, Hefner JL. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:534–42. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee C, Gramotnev H. Life transitions and mental health in a national cohort of young Australian women. Dev Psychol. 2007;43:877–88. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schumaker JF. Religion and mental health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tix AP, Frazier PA. The use of religious coping during stressful life events: main effects, moderation, and mediation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:411–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sander W. Religion, religiosity, and happiness. Rev Relig Res. 2017;59:251–62. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.French S, Joseph S. Religiosity and its association with happiness, purpose in life, and self-actualisation. Mental Health, Religion Culture. 1999;2:117–20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:461–80. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamaideh SH. Gender differences in stressors and reactions to stressors among Jordanian university students. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58:26–33. doi: 10.1177/0020764010382692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levesque R, Roger JR. Encyclopedia of adolescence. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinnells J. The Routledge companion to the study of religion. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.John F, Adekunle A, Jamal M, Tashia B. Religious commitment, social support and life satisfaction among college students. Coll Stud J. 2011;45:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roshani K. Relationship between religious beliefs and life satisfaction with death anxiety in the elderly. Ann Biol Res. 2012;3:4400–5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mooney M. Religion, college grades, and satisfaction among students at elite colleges and universities. Sociol Relig. 2010;71:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Los Angeles, CA: University of California; 2005. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 1]. UCLA Higher Education Research Institute. The Spiritual Life of College Students: A National Study of College Students’ Search for Meaning and Purpose. Available from: http://spirituality.ucla.edu/docs/reports/Spiritual_Life_College_Students_Full_Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winterowd C, Harrist S, Thomason N, Worth S, Carlozzi B. The relationship of spiritual beliefs and involvement with the experience of anger and stress in college students. J Col Stud Dev. 2005;46:515–29. [Google Scholar]