Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of denosumab or zoledronic acid (ZA) using symptomatic skeletal events (SSEs) as the primary endpoint in Asian postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer.

Methods

Asian postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer receiving subcutaneous denosumab 120 mg Q4W, or intravenous ZA 4 mg Q4W until the primary analysis cut-off date were retrospectively analysed in the Hong Kong Practice-Based Cancer Research Center(HKCRC) from March 2011 to March 2013. The time to first on-study SSE that was assessed either clinically or through routine radiographic scans was the primary endpoint.

Results

242 patients received denosumab or ZA treatment (n = 120, mean age of 64.9 years (SD 3.01) and n = 122, 65.4 years (3.44), respectively). The median times to first on-study SSE were 14.7 months (12.9–45.6) and 11.7 months (9.9–45.6) for denosumab and ZA, respectively (hazard ratio, HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.71–2.95; p = 0·0002). Compared with the ZA group, denosumab-treated patients had a significantly delayed time to first SSE (HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.29–1.45], p < 0.0001). An increased incidence of SSE was found in the 16-month follow-up with rates of 2.1 and 10.7% for denosumab and ZA, respectively (P = 0.033). The difference persisted with time with rates of 8.3 and 17.2% at the final follow-up, respectively (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

In postmenopausal women aged ≥60 years with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer, denosumab significantly reduced the risk of developing SSEs compared with ZA. The findings of this pilot trial justify a larger study to determine whether the result is more generally applicable to a broader population.

Keywords: Denosumab, Zoledronic acid, Breast cancer, Symptomatic skeletal event, Outcome analyses

Background

Oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer, one of the most common malignancies reported worldwide, has a protracted risk of symptomatic skeletal events(SSEs), which are defined as radiation to the bone, symptomatic pathologic fracture, surgery to the bone, or symptomatic spinal cord compression [1–4]. SSEs often occur in women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer and the associated complications have a substantial disease and economic burden. After 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen, patients have a sustained risk of SSEs [5]. Long-term follow-up from pivotal upfront trials of adjuvant aromatase inhibitors, including Arimidex and Tamoxifen, alone or in combination, have demonstrated a continuing rate of SSEs of approximately 11% per year after initial therapy [6, 7]. These findings emphasize the need for extended adjuvant therapy.

Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody, neutralizes the Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand (RANKL), which is essential for the formation, function, and survival of the osteoclasts; also, it blocks osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [8, 9]. Gnant et al. [1] described the application of denosumab for preventing SSEs in postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive stage 1–3 breast cancer undergoing denosumab as adjuvant treatment. Nevertheless, their study subjects who had a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score < − 2.5 at study entry failed to be specifically excluded. Furthermore, other risk factors influencing the occurrence of SSEs in their study subjects were not described. The ZO-FAST study [10] of zoledronic acid (ZA), which was also performed in postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive stage 1–3 breast cancer every 6 months, revealed no difference in the SSE rates in the long-term follow-up. In another AZURE trial [11] evaluating ZA, the time to first SSE was reduced with the exploitation of ZA; however, this difference was attributable to the effect on SSEs after breast cancer recurrence, and there was no difference in the SSE rates before breast cancer recurrence.

For Asian postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer, to the best of our knowledge, a direct comparison between denosumab and ZA has rarely been reported in the published literature. Denosumab and ZA are effective interventions to prevent SSEs, and they provide a new bone protection option for postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. Nevertheless, several unanswered questions remain [12]. The purpose of the retrospective study was to evaluate the efficacy of denosumab or ZA using SSEs as the primary endpoint in Asian postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer.

Methods

Study population

Subjects included in this analysis were collected from the Hong Kong Practice-Based Cancer Research Center (HKCRC). Eligible patients were Asian postmenopausal women aged ≥60 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer diagnosed from March 2011 to March 2013. All patients had completed treatment with surgery and/or radiation and chemotherapy ≥4 weeks before study enrolment and received adjuvant denosumab or ZA therapy. The main exclusion criteria were the following: previous denosumab or ZA exposure or any aromatase inhibitor use during the 3 months; non-healed or planned surgery; chemotherapy or endocrine therapy for other diseases; active metabolic bone disease; undergoing castration; recurrence and metastasis before SSEs; use of medication that affects bone metabolism; renal deterioration during treatment; other primary tumours or advanced cancer; discontinuation or interruption of denosumab or ZA treatment; unable to complete surveys; life expectancy < 1 year; a BMD T score ≤ − 2.5 SD at the lumbar spine or femoral neck; modification of therapy during the follow-up period; severe infectious diseases; an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of IV or V; and co-occurring mental illness.

Definitions of the descriptive variables

The patients’ body mass index (BMI) was calculated during the clinical examination. The BMD T-score was measured at the lumbar spine or femoral neck. Radiographic skeletal surveys of SSEs confirmed radiologically by a radiologist were performed within 4 weeks, every 3 months thereafter, and at the end-of-study visit. SSEs were defined as radiation therapy to the bone (including radioisotopes), pathologic fracture (excluding trauma), surgery to the bone, or spinal cord compression.

Study design and treatment

This was a retrospective study in which postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer underwent either subcutaneous denosumab 120 mg Q4W or intravenous ZA 4 mg Q4W until the primary analysis cut-off date. The denosumab and ZA doses were not adjusted or suspended. All patients were instructed to take calcium (1 g/day) and vitamin D (400 IU/day). The same antineoplastic therapy was routinely used and was not adjusted in the two groups.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive and outcome variables were assessed by calculating the frequencies, means, and standard deviations (SDs). Comparison between groups was conducted using Pearson’s Chi-square test or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. The time to first SSE was assessed using a Kaplan-Meyer analysis and Log-rank test. The risk and factors of SSEs were analysed by the Cox regression model. The analyses were based on the data up to the primary analysis cut-off. A p-value < 0.05 was used as a threshold for significance. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software (IBM-SPSS Statistics version 23.0, Inc., New York, USA).

Results

Patients

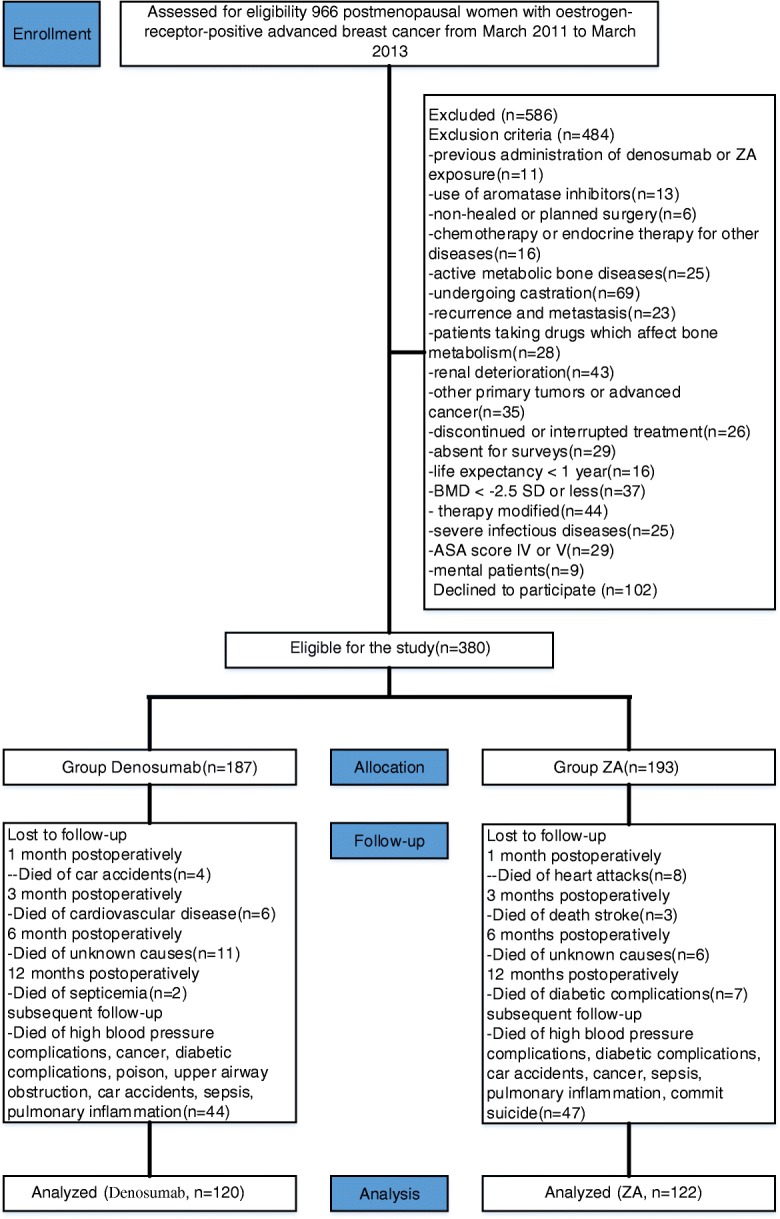

A total of 966 patients were assessed for study eligibility. Of these, 242 patients (denosumab group n = 120, mean age 64.9 years (SD 3.01) and ZA group n = 122, 65.4 years (SD 3.44), respectively) met the inclusion criteria. Details are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. The median duration for study at the primary analysis cut-off date was 37 months (IQR 25.1–45.3) for patients on denosumab and 38 months (IQR 26.2–45.8) for those on ZA. The median time to first on-study SSE was 16.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 14.3–45.3) with denosumab compared to 11.7 months (9.9–45.6) with ZA (hazard ratio [HR] 0.44, 95% CI 0.71–2.95; p = 0.0002). Compared with the ZA group, denosumab-treated patients had a significantly delayed time to first SSE (HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.29–1.45], p < 0.0001). An increased incidence of SSE was found at the 16-month follow-up with rates of 2.1 and 10.7% for denosumab and ZA, respectively (P = 0.033). The difference persisted with time with rates of 8.3 and 17.2% at the final follow-up (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram demonstrating methods for identification of studies to assess the efficacy of denosumab or zoledronic acid (ZA) using symptomatic skeletal events(SSEs) as the primary end point in postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer

Table 1.

Comparison of patient demographics between groups

| Variable | Denosumab (n = 120) | ZA (n = 122) | P – value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.9 ± 3.01 | 65.4 ± 3.44 | 0.19*a |

| Menopause age | 53.1 ± 1.82 | 52.9 ± 1.78 | 0.43*a |

| Pathological types, No. | 0.92*b | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 97 | 98 | |

| Other pathological types | 23 | 24 | |

| Tumor staging | 0.95*c | ||

| I | 53 | 57 | |

| II | 46 | 40 | |

| III | 21 | 25 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 2.34 | 23.9 ± 2.36 | 0.11*a |

| BMD | −2.30 ± 0.21 | −2.33 ± 0.29 | 0.37*a |

| Personal history of fractures | 15/120 | 19/122 | 0.49*b |

| Family history of fractures | 17/120 | 18/122 | 0.90*b |

* No statistically significant values. a Analysed using an Independent-Samples t-test; b Analysed using the Chi-square test; c Analysed using the Mann-Whitney test. ZA: zoledronic acid; SSEs: symptomatic skeletal events; BMI: body mass index; BMD: bone mineral density

The homogeneity test of variances and t test of clinical data

In this study, both the pathological type and tumour stage in the 2 groups of patients were similar. There were no significant differences in the clinical risk factors, including the age at diagnosis, age at menopause, BMI, personal or family fracture history, or chemotherapy history.

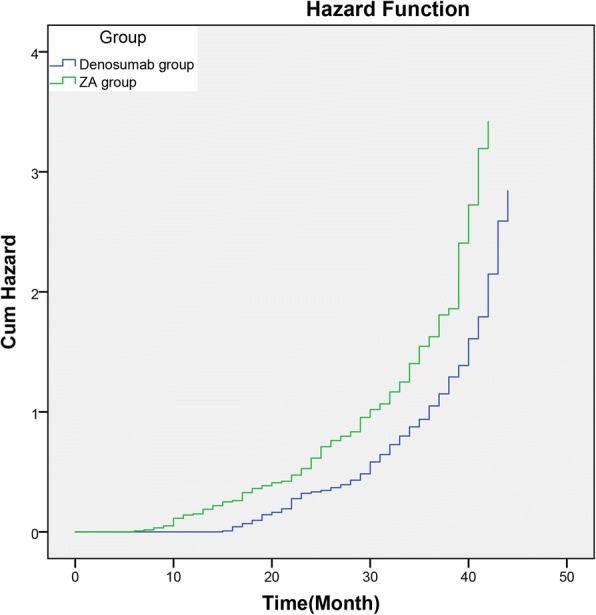

SSE incidence and risk

In a comparison of the SSEs as endpoints, there were 11 fewer first on-study SSEs in the denosumab group than in the ZA group (10 versus 21, respectively) (Table 2). As anticipated, there were fewer first on-study pathologic fractures in the denosumab group than in the ZA group (4 versus 13). In addition to pathological fractures, the numbers of patients with confirmed first on-study SSEs in each remaining event type was lower in the denosumab group than in the ZA group.

Table 2.

Comparison of SSE incidence between groups

| Variable | Denosumab (n = 120) | ZA(n = 122) | P - value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total incidence of SSEs | 10/120 | 21/122 | 0.04*a |

| SSE incidence | |||

| within 2 years | 3/120 | 4/122 | 0.21a |

| after 2 years | 7/120 | 17/122 | 0.04*a |

* Statistically significant values. aAnalysed using the Chi-square test. ZA: zoledronic acid; SSEs: symptomatic skeletal events

In the ZA group, the first on-study SSE incidence was 17.2% (21 /122), in which the first on-study SSE incidence during 2-year drug use was 3.3% (4/122). After 2-year treatment, 13.9% (17/122) of cases developed a first on-study SSE. In contrast, in the denosumab group, the incidence of first on-study SSEs was only 8.3% (10/120), which was lower than in the ZA group (P = 0.04). The incidence of first on-study SSEs was 5.8% (7/120) after 2 years, which was also significantly lower than that in the ZA group (P = 0.04), but there was no significant difference between groups in the first on-study SSE within the 2-year period [2.5% (3/120) vs. 3.3% (4/122), respectively, P = 0.21].

Compared with ZA, denosumab reduced the risk of first on-study SSEs by 20% (HR, 0.80; 95% CI 0.52–0.88; P = 0.002). The median time to the first on-study SSE was not reached in the denosumab group, while it was 25.5 months in the ZA group. As previously reported, denosumab reduced the risk of first on-study SSEs by 18% compared to ZA. The risk of a first on-study SSE in the ZA group was 10 times higher than that in the denosumab group during the 2-year drug use (HR = 10.843, P = 0.026). After 2-year treatment, the ZA group had an increased risk of a first on-study SSE compared with the denosumab group (HR = 13.221, P = 0.001).

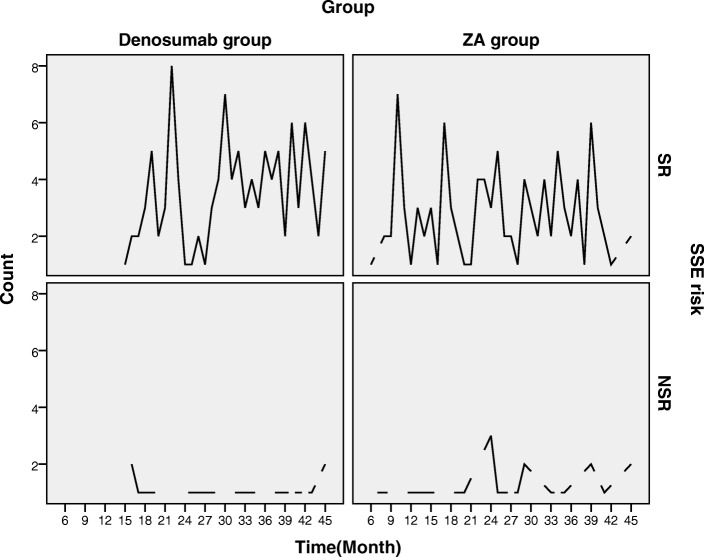

Cumulative risk of SSEs

The Kaplan-Meyer curve showed that the cumulative risk curve in the denosumab group was significantly lower than that in the ZA group (P = 0.002) (Figs. 2, 3 and Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of hazard

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the distribution and size of SR and NSR at each follow-up time point. There were statistically significant differences in SR or NSR between groups noted. SR: symptomatic skeletal event; NSR: non-symptomatic skeletal event

Table 3.

SSE risk ratio between groups

| Variable | Denosumab (n = 120) | ZA(n = 122) | P - value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total SSE HR(95%CI) | 12.43 | 19.92 | 0.002* |

| (2.17-17.44) | (3.34–21.35) | ||

| SSE HR(95%CI) | |||

| within 2 years | 6.33 | 7.27 | 0.106* |

| (1.36-12.38) | (1.54–19.63) | ||

| after 2 years | 36.26 | 83.52 | 0.001* |

| (3.31-161.15) | (4.29–92.60) | ||

* Statistically significant values. SSEs: symptomatic skeletal events; ZA: zoledronic acid; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval

Clinical risk factors for SSEs

In the denosumab group, the risk of a first on-study SSE in a person with a history of SSEs was approximately 15 times higher than for someone with no history of SSEs (HR =15.41, P = 0.001). The risk of a first on-study SSE with a family history of SSEs was approximately 2 times higher than for someone with no family history of SSEs (HR = 2.07, P = 0.001). The risk of a first on-study SSE in a denosumab-treated patient aged > 60 years was approximately 1-fold higher than in a ZA-treated patient (HR =1.59, P = 0.001). The clinical risk of other factors that influence the occurrence of SSEs, including menopausal patients aged ≤50 years and low BMI (≤ 19 kg /m2), increased the trend in the first on-study SSE risk, but no significant differences were observed (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical risk factors for SSEs in two groups

| Denosumab | ZA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | HR(95%CI) | P –value | HR(95%CI) | P - value |

| Age (y) | 0.003* | 0.001* | ||

| ≤60 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 60 | 3.13(1.02–1.68) | 4.72(2.36–7.17) | ||

| Menopause age(y) | 0.440 | 0.247 | ||

| ≤50 | 5.04(0.03–22.12) | 5.04(0.03–22.12) | ||

| > 50 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PHF | 0.002* | 0.005* | ||

| no | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 21.34(5.23–49.12) | 36.75(2.39–74.32) | ||

| FHF | 0.037* | 0.041* | ||

| no | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 6.79(1.10–11.65) | 8.86(1.43–38.15) | ||

| BMI(kg/m2) | 0.793 | 0.219 | ||

| ≤19 | 3.76(0.66–31.32) | 5.36(0.19–44.61) | ||

| > 19 | 1 | 1 | ||

* Statistically significant values. SSEs: symptomatic skeletal events; ZA: zoledronic acid; PHF: personal history of fractures; FHF: family history of fractures; BMI: body mass index

Discussion

In the retrospective study on 242 Asian postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer who underwent denosumab or ZA treatment, the most important finding was that denosumab-treated patients had a decreased risk of SSEs compared with ZA-treated patients, which coincided with the results of some other reports [1, 4, 21]. No safety differences were found in women treated with denosumab or ZA.

There was a recent review of the treatment and prevention of SSEs in postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer [9, 13, 14]. Previous therapy with aromatase inhibitors (AI), which reduce endogenous serum oestrogen concentrations and are related to accelerated bone loss, decreased the BMD and increased the SSE risk, making them important in the comprehensive treatment for women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer [14, 15]. Because AI can effectively reduce the levels of oestrogen in postmenopausal women with breast cancer, significantly reduce breast cancer recurrence and metastasis, and prolong patient survival, they have become one of the preferred endocrine therapy drugs for postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer [12, 16]. However, postmenopausal women, because the skeletal system has lost the protective effect of oestrogen, are at a high risk of SSEs, and AI will add an additional 3 to 4% / year bone loss, increasing the risk of SSEs [4]. In recent years, international scholars have focused their attention on a new drug (denosumab) and have comprehensively evaluated its effectiveness and safety [17, 18]. However, the findings in postmenopausal women have remained unclear and have demonstrated the need for further study [17–19]. Moreover, there are no literature data on the SSEs evaluated in Asian postmenopausal women.

There are many large-scale clinical trials studying the effects of denosumab in postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer [20–22], but the tests in the subgroup analysis of SSEs are limited because the control group is women receiving tamoxifen (TAM) [19]. Previous studies have shown that TAM has a weak oestrogen effect, which can protect the bone system in postmenopausal breast cancer women [23]. This interference factor may increase the risk of SSEs caused by denosumab treatment. In the current study, we selected postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer who received ZA as a control group to avoid the interference of endocrine therapy and accurately analyse the risk of denosumab-related SSEs. Statistical analysis showed that the clinical data of the patients in both groups failed to have selective bias. Furthermore, our analyses of SSEs excluded asymptomatic fractures and/or spinal cord compression. Because of any SSE having the potential to convert symptomatic over time, the number of SSEs could be underestimated in some cases [18].

Few previous reports have focused on denosumab versus ZA for preventing SSEs in Asian postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer in the Asian population [24–26]. However, the majority of these studies had low sample sizes and a relatively short follow-up period; therefore, drawing conclusions about the relative superiority of one drug over the other using SSEs as the primary endpoint may be inappropriate. Lipton et al. [27] reported that in breast cancer patients with bone metastases, denosumab was superior to ZA in delaying the time to the first on-study SSE (HR = 0.82; P = 0.01) and the time to the first and subsequent on-study SSEs (HR = 0.77; P = 0.001). Martin et al. [28] evaluated further results from this study (denosumab was shown to be superior to ZA in preventing SSEs in women with breast cancer in a randomized, double-blind phase III study) related to SSEs and showed that denosumab had superior efficacy in the time to first SSE compared with ZA. In this study, baseline characteristics of our population were consistent with a previously published study [21, 22], and the SSE rate in the denosumab group was significantly lower compared with that in the ZA group regardless of whether analysis was performed during drug use, after the cessation of drug use, or during the follow-up period. The total SSE incidence rates in the denosumab and ZA groups were 8.3 and 17.2%, respectively, which were lower than the 19.5% (40-month follow-up) and 24.8% (70-month follow-up) in the BIG1–98 trial. These differences may be related to the differences between the Chinese and Western race, physical quality and lifestyle. In addition, in the study, 2 (2/120) cases treated with denosumab for 2 years, who were followed up individually, had SSEs at the end of 9 and 16 months after treatment, respectively. The SSE incidence of denosumab-treated patients (8.3%, 10/120) was significantly lower than the 17.2% (21/122) of ZA-treated patients. Although the results at any individual skeletal site for any individual variable should be interpreted with caution because of the small population sizes, the present outcomes in our study were comparable to those of other series [21, 22].

Throughout the follow-up period, the risk of SSEs in the denosumab group was nearly 7 times lower than that in the ZA group. However, there was no significant difference in the risk of SSEs within the 2-year period. Some studies claimed that ZA-treated patients had an increased trend in the risk of SSEs compared with denosumab-treated patients [29, 30], which was not consistent with our findings. One reason may be that patients with an average age of 65 years included in the study may influence the rate of SSEs with denosumab treatment; also, there are differences between denosumab and ZA in the distribution of BMD increases in the cortical and trabecular compartments of bone as well as the effect of denosumab on decreasing cortical porosity, which may contribute to increases in the bone strength [30]. Additionally, although denosumab treatment has an established anti-fracture efficacy, there is recent concern about the increased SSE risk following its discontinuation [18]. Simultaneously, the differences in both race and lifestyle between countries can directly influence the results.

The clinical risk factors (including age, premature menopause, personal fracture history, family fracture history, low BMI and chemotherapy history) in the two groups were analysed in the current study. We found that patients with a history of fracture or a family history of fractures had a higher risk of SSEs. The age of menopause, BMI and chemotherapy history had no significant effect on the occurrence of SSEs; the specific reasons for this finding are unclear and may be related to bone.

The limitations of the study include the short follow-up period, small sample size, and lack of follow up evaluation of the changes in the blood calcium and BMD. Nevertheless, the patient population is a strength of the study and suggests that the current findings are applicable to a wide range of postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer. Additionally, the precision for estimating the percent of SSEs is low, resulting in large confidence intervals. Although the study is powered to detect SSE differences, the analyses in this study failed to exclude subtle fractures that occurred before the endpoint measurement.

Conclusions

At the time of the cut-off date for this analysis, we conclude, as expected, that denosumab significantly reduced the risk of SSEs compared with ZA in Asian postmenopausal women who had oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer regardless of whether they were followed for 2 years or less, which provided further evidence for the superior ability of denosumab to prevent SSEs versus ZA. Further investigation of the long-term utility of denosumab and ZA is necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Xiaohui Li for her assistance with the technical help.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission Fund Project (201640057), Natural Science Foundation of China (81770876; 81270011; 81472125), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant BK20151114), Foundation of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Jiangsu Province (YB201578), and Fundamental Research Funds for Medical Innovation Center of Health and Family Planning Commission of Wuxi (CXTD006). The funding body did not play a role in study design, analysis, interpretation of the data, or the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AI

Aromatase inhibitors

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- BMI

Body mass index

- HKCRC

Hong Kong Practice-Based Cancer Research Center

- RANKL

Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand

- SDs

Standard deviations

- SSEs

Symptomatic skeletal events

- TAM

Tamoxifen

- ZA

Zoledronic acid

Authors’ contributions

CZ, FZ, GL, FY, and ZJ contributed to the conception and design, data collection, and revision of the article for important intellectual content, and participated in coordination. XZ, JM, WY, WJ, and FY performed data collection, data analysis, and revision of the article for important intellectual content, and drafted the manuscript. MZ, MX, and KG conceived of the study, participated in the design of the study, performed data interpretation and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Hongkong Elizabeth hospital. The study was found by the institution to be exempt from requiring consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chi Zhang, Email: Alpha_doc@163.com.

Fan Zhang, Email: fzhang1105@163.com.

Guanzhao Liang, Email: gzhliang1989@aliyun.com.

Xianshang Zeng, Email: xianshangzh@126.com.

Weiguang Yu, Email: 10211270007@fudan.edu.cn.

Zhidao Jiang, Email: jiangzhidao727@126.com.

Jie Ma, Email: cherryraul@sina.com.

Mingdong Zhao, Email: zhaonissan@163.com.

Min Xiong, Email: gkysxm@sohu.com.

Keke Gui, Email: gilbird@163.com.

Fenglai Yuan, Email: bjjq88@163.com.

Weiping Ji, Email: jiweiping19841022@126.com.

References

- 1.Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Dubsky PC, Hubalek M, Greil R, Jakesz R, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer (ABCSG-18): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JP, Dempster DW, Ding BY, Dent-Acosta R, San Martin J, Grauer A, et al. Bone remodeling in postmenopausal women who discontinued Denosumab treatment: off-treatment biopsy study. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(11):2737–2744. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappetta A, Spano L, Evangelista L, Zovato S, Opocher G, Pastorelli D. Impressive response to denosumab in a patient with bone metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach after 2 years of zoledronic acid. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2015;26(2):232–235. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husnoo N, Abbas S. Management of Aromatase Inhibitor-Induced Bone Loss in breast Cancer patients. Br J Surg. 2016;103:134–135. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JP, Reid IR, Wagman RB, Kendler D, Miller PD, Jensen JEB, et al. Effects of up to 5 years of Denosumab treatment on bone histology and Histomorphometry: the FREEDOM study extension. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(9):2051–2056. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JP, Roux C, Ho PR, Bolognese MA, Hall J, Bone HG, et al. Denosumab significantly increases bone mineral density and reduces bone turnover compared with monthly oral ibandronate and risedronate in postmenopausal women who remained at higher risk for fracture despite previous suboptimal treatment with an oral bisphosphonate. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(7):1953–1961. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell-Baird C, Harrelson S, Frey G, Balakumaran A. Clinical efficacy of denosumab versus bisphosphonates for the prevention of bone complications: implications for nursing. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(12):3625–3632. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Body JJ, Bone HG, De Boer RH, Stopeck A, Van Poznak C, Damiao R, et al. Hypocalcaemia in patients with metastatic bone disease treated with denosumab. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(13):1812–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewiecki EM. Denosumab update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(4):369–373. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832ca41c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman R, de Boer R, Eidtmann H, Llombart A, Davidson N, Neven P, et al. Zoledronic acid (zoledronate) for postmenopausal women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant letrozole (ZO-FAST study): final 60-month results. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(2):398–405. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman R, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Bell R, Wilson C, Rathbone E, et al. Adjuvant zoledronic acid in patients with early breast cancer: final efficacy analysis of the AZURE (BIG 01/04) randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):997–1006. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman R, Hadji P. Denosumab and fracture risk in women with breast cancer. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):409–410. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)61032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa AG, Bilezikian JP. How long to treat with Denosumab. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13(6):415–420. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki K, Ito Y, Takahashi S. Re: superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of three pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(9):2264–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman RE, Rathbone E, Brown JE. Management of cancer treatment-induced bone loss. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(6):365–374. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boskovic L, Gasparic M, Petkovic M, Gugic D, Lovasic IB, Soldic Z, et al. Bone health and adherence to vitamin D and calcium therapy in early breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy with aromatase inhibitors. Breast. 2017;31:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anastasilakis AD, Makras P. Multiple clinical vertebral fractures following denosumab discontinuation. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(5):1929–1930. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3459-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MR, Coleman RE, Klotz L, Pittman K, Milecki P, Ng S, et al. Denosumab for the prevention of skeletal complications in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: comparison of skeletal-related events and symptomatic skeletal events. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):368–374. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farooki A, Fornier M. Denosumab and fracture risk in women with breast cancer. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2056–2057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilcken N, Lee CI. In postmenopausal women with breast cancer treated with aromatase inhibitors, denosumab reduced fractures. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6). doi:10.7326/acpjc-2015-163-6-011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Abdel-Rahman O. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid to prevent aromatase inhibitors-associated fractures in postmenopausal early breast cancer; a mixed treatment meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(8):885–891. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2016.1192466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu EQ, Xie J, Signorovitch J, Diener M, Sorg R, Namjoshi M. Number needed to treat and treatment cost per fracture avoided with denosumab compared with zoledronic acid in patients with breast cancer with bone metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27).

- 23.Ekholm M, Bendahl P-O, Ferno M, Nordenskjold B, Stal O, Ryden L. Two Years of Adjuvant Tamoxifen Provides a Survival Benefit Compared With No Systemic Treatment in Premenopausal Patients With Primary Breast Cancer: Long-Term Follow-Up (> 25 years) of the Phase III SBII:2pre Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(19):2232−+. doi:10.1200/jco.2015.65.6272. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Nakamura T, Matsumoto T, Sugimoto T, Hosoi T, Miki T, Gorai I, et al. Clinical trials express: fracture risk reduction with Denosumab in Japanese postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis: Denosumab fracture intervention randomized placebo controlled trial (DIRECT) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(7):2599–2607. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugimoto T, Matsumoto T, Hosoi T, Miki T, Gorai I, Yoshikawa H, et al. Three-year denosumab treatment in postmenopausal Japanese women and men with osteoporosis: results from a 1-year open-label extension of the Denosumab fracture intervention randomized placebo controlled trial (DIRECT) Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(2):765–774. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie JP, Diener M, Sorg R, Wu EQ, Namjoshi M. Cost-effectiveness of Denosumab compared with Zoledronic acid in patients with breast Cancer and bone metastases. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12(4):247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipton A. Denosumab in breast Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin M, Bell R, Bourgeois H, Brufsky A, Diel I, Eniu A, et al. Bone-related complications and quality of life in advanced breast Cancer: results from a randomized phase III trial of Denosumab versus Zoledronic acid. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(17):4841–4849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis GK, Bone HG, Chlebowski R, Paul D, Spadafora S, Fan M, et al. Effect of denosumab on bone mineral density in women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for non-metastatic breast cancer: subgroup analyses of a phase 3 study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118(1):81–87. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0352-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Gkiomisi A, Bisbinas I, Gerou S, Makras P. Comparative effect of Zoledronic acid versus Denosumab on serum Sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 levels of naive postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, head-to-head clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):3206–3212. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.