Abstract

Background

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica L. P. Beauv) has been considered as a tractable model crop in recent years due to its short growing cycle, lower amount of repetitive DNA, inbreeding nature, small diploid genome, and outstanding abiotic stress-tolerance characteristics. With modern agriculture facing various adversities, it’s urgent to dissect the mechanisms of how foxtail millet responds and adapts to drought and stress on the proteomic-level.

Results

In this research, a total of 2474 differentially expressed proteins were identified by quantitative proteomic analysis after subjecting foxtail millet seedlings to drought conditions. 321 of these 2474 proteins exhibited significant expression changes, including 252 up-regulated proteins and 69 down-regulated proteins. The resulting proteins could then be divided into different categories, such as stress and defense responses, photosynthesis, carbon metabolism, ROS scavenging, protein synthesis, etc., according to Gene Ontology annotation. Proteins implicated in fatty acid and amino acid metabolism, polyamine biosynthesis, hormone metabolism, and cell wall modifications were also identified. These obtained differential proteins and their possible biological functions under drought stress all suggested that various physiological and metabolic processes might function cooperatively to configure a new dynamic homeostasis in organisms. The expression patterns of five drought-responsive proteins were further validated using western blot analysis. The qRT-PCR was also carried out to analyze the transcription levels of 21 differentially expressed proteins. The results showed large inconsistency in the variation between proteins and the corresponding mRNAs, which showed once again that post-transcriptional modification performs crucial roles in regulating gene expression.

Conclusion

The results offered a valuable inventory of proteins that may be involved in drought response and adaption, and provided a regulatory network of different metabolic pathways under stress stimulation. This study will illuminate the stress tolerance mechanisms of foxtail millet, and shed some light on crop germplasm breeding and innovation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12870-018-1533-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.), Drought stress, Comparative proteomics, Expression pattern, Western blot, qRT-PCR

Background

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) is an ancient crop in the subfamily of Panicoideae, and is distributed worldwide in arid and semi-arid regions. It originated in North China, and was domesticated more than 8,700 years ago. As foxtail millet grains are rich in protein and minerals, especially when compared to those of rice, wheat, and maize, it was named first among the “Five Grains of China” due to its high nutritional values [1].

Foxtail millet possess most noticeable morphological and anatomical attributes, such as dense root distribution, thick cell wall, small leaf area and epidermal cell arrangement, which endow it with strong drought tolerance and high water use efficiency, and further allow it to be primarily cultivated in arid, semi-arid, and barren regions. Today, foxtail millet is attracting more attention in agricultural production, especially as global warming and lacking water resources become increasingly severe in the world [2].

Additionally, foxtail millet carries attractive qualities such as a small diploid genome (~490 Mb), inbreeding nature, less repetitive DNA, short growing cycle and abiotic stress-tolerance [3]. As opposed to other proximal plants, such as pearl millet, switchgrass, and napiergrass, these features highlight it as a model crop for exploring the mechanisms of drought tolerance, evolutionary genomics, architectural traits, C4 photosynthesis and the physiology of bioenergy crops [4]. Recently, the genome sequences of foxtail millet cultivars“Yugu1” and “Zhanggu” have been sequenced and submitted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genomic Institute and Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) of China, respectively [3, 5].

After the genomic sequence of foxtail millet was released, the vital stress-related gene families, such as the SiNAC, SiWD40 and SiALDH gene families, were systematically analyzed and identified [6–8]. The SiPLDa1, SiDREB2, SiNAC, SiOPR1, and SiAGO1b genes were all reported to mediate various stress responses and developmental processes during dehydration stress [6, 9–12]. Deep sequencing technology was also used to investigate the genome-wide transcriptome reconfiguration of foxtail millet under drought stress, and a great number of differentially expressed genes (2,824), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were identified [13]. Under dehydration stress, 105 and 84 differentially expressed genes were identified in foxtail millet roots and shoots, respectively, and the responses of genes involved in gluconeogenesis and glycolysis pathways took place earlier in roots compared to shoots. Furthermore, the protein degradation pathway may also perform a key role in drought tolerance of foxtail millet [11].

Although drought-responsive genes and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) were identified, there have been hardly any systematic investigation summaries of protein profiling for drought stressed foxtail millet. Protein profiling will contribute to the systematic scrutiny of changes in protein levels and activities, and provide information about which proteins may participate in certain biological processes. Recently, tandem mass tags (TMT), combined with liquid chromatography−quadruple mass spectrometry (LC−MS/MS) analysis, has been utilized as an useful quantitative proteomic technique, which facilitates simultaneous identification and relative quantification of proteins with great efficiency and accuracy. This method is also widely used for quantitative comparative analysis of plant proteomes [14]. In this study, the TMT combined with LC-MS/MS-based proteomic approach was used, and the differentially expressed proteins in foxtail millet seedlings after drought treatment were quantitatively identified. There were 2474 differential proteins that were quantitatively identified, among which, 321 drought responsive proteins were identified. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that these differential proteins may take part in various biological processes. These biological processes may function synergistically by initiating different response mechanisms on the protein level to reconfigure and achieve new homeostasis in drought conditions. Our results begin filling the gap in our knowledge regarding the proteomic activity and regulated response mechanisms under drought conditions in foxtail millet, which will further deepen the understanding of the physiological and molecular basis of stress tolerance in crops.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The foxtail millet variety, Yugu1, which is known to be a drought resistant variety and whose genome has been sequenced, was used for all experiments [15]. Plastic pots (21 cm in diameter × 21 cm in height) were used as experimental units. Each pot was filled with 3-kg soil consisting of a mixture of nutrient soil and loamy sand in a ratio of 1:1. Plants were grown in greenhouse with well-watered conditions under 30/25 °C day/night cycle with a 14-h photoperiod for three weeks. The drought treatments were performed as previously described [16]. Soil moisture of well-watered and drought-treated experimental units was controlled at 60–70% and 20-30% of field capacity respectively, and the treatments lasted for 7 days. The pots were randomized in four replicates between the two treatments. After drought treatments, seedlings were immediately harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for protein and RNA extraction, and then to perform proteomic, western blot and gene expression analysis.

Protein extraction and trypsin digestion

Protein extraction and trypsin digestion were performed according to a previously established method [17] with slight modification. Samples were first grinded in liquid nitrogen, then the tissue powder in lysis buffer was ultra-sonicated three times. The remaining debris was removed after centrifugation, and the protein was precipitated with 15% TCA and washed with cold acetone. The precipitates were re-suspended in buffer made of 100 mM TEAB and 8 M urea at pH 8.0. The protein concentration was determined using 2-D Quant kit (GE Healthcare B80648356 Piscataway USA).

For protein digestion, the protein solution was reduced with 10 mM DTT and alkylated with 20 mM Iodoacetic acid. After that, the protein samples were diluted by adding 100 mM TEAB with urea concentration less than 2M. Finally, the protein was digested at 1:50 and 1:100 trypsin-to-protein mass ratios with two replicates of each. For each sample, approximately 100 μg of protein were digested for the following experiments.

TMT labeling and HPLC fractionation

After trypsin digestion, the peptide was desalted by Strata X C18 SPE column (Phenomenex) and vacuum-dried. The peptide was reconstituted using 6-plex TMT kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and the sample was then fractionated according to protocol of [17].

LC-MS/MS analysis

The peptides were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid (FA), and then directly loaded onto a reversed-phase pre-column (Acclaim PepMap 100, Thermo Scientific). The peptide separation was performed using a reversed-phase analytical column (Acclaim PepMap RSLC, Thermo Scientific). LC-MS/MS analysis was performed according to protocol of [17].

Database searching

The resulting MS/MS data were processed using Mascot search engine (v.2.3.0). Tandem mass spectra were blasted against Uniprot_foxtail_4555 (http://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/4555) database concatenated with reverse decoy database. Trypsin/P was specified as the cleavage enzyme allowing up to two missing cleavages. Mass error was set to 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.02 Da for fragment ions. Carbamidomethyl on Cys, TMT6plex (N-term) and TMT6plex (K) were specified as the fixed modifications, and oxidation on Met was specified as the variable modification. FDR was adjusted to <1% and peptide ion score was set to >20.

Gene Ontology (GO) annotation proteome was derived from the UniProt-GOA database (www. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/GOA/). The proteins were classified by Gene Ontology annotation based on three categories: biological process, cellular component and molecular function. The functional description of identified protein domains was annotated by InterProScan (a sequence analysis application) based on protein sequence alignment method, using the InterPro domain database. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/) was used to annotate protein pathway: first, by using the KEGG online service tool, KAAS, to annotate e the protein’s KEGG database description, then by mapping the annotation results on the KEGG pathway database using KEGG online service tool, KEGG mapper. Wolf-psort (http://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html) was used to predict the protein’s subcellular localization. The Protein-Protein Interaction analysis was performed according to [18].

Physiological parameters measurements

The measurements of physiological parameters, such as antioxidant enzyme activity and proline and soluble sugar content, were performed as described previously [19]. The Glycine betaine (GB) content was measured according to [20]. The detections of spermine and spermidine were carried out according to the method of [21].

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from foxtail millet seedlings in extraction buffer containing 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF and 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol. Protein extracts were separated on 12% SDS−PAGE gels and then transferred to a PVDF membrane using a Mini Trans-Blot cell (Beijin Jun Yi electrophoresis equipment, China). The membranes were first blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin in TBST buffer (100mM NaCl2, 20mM Tris pH 8.0 and 0.5% Tween-20) for 2h, and then incubated with polyclonal antibodies at a 1:1000 dilution for another 2h at room temperature. After washing three times with TBST buffer, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibody of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG at a 1:1000 dilution for 2h. After three times further washes in TBST buffer,the membranes were visualized with a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) detection system (Sangon Biotech, China). The western blot analysis was repeated twice. The SiActin (XM_004978702) was used as the internal control to quantify protein loading of different samples. Antibody production was conducted as described above. The peptides of SiPPR (XM_004978236) (residues 186-508) and SiRLK (XP_004956304.1) (residues 1-386) were expressed and purified as described [22]. The purified peptide was injected into rabbits for polyclonal antibody preparation. Using these polyclonal antibodies, only one band was detected at the corresponding position in the Western Blot. The antibodies for SiCAT (XM_004985783), SiHSP70 (XM_004981194), SiTuBulin (XM_004981865) and Actin were purchased from Agrisera, Sweden(product numbers were AS09 501, AS08 371, AS10 680, and AS13 2640, respectively.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from foxtail millet was extracted with Trizol reagent (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA electropherogram is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. First strand cDNAs were synthesized using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (TaKaRa). Quantitative Real-time PCR was performed in 7500 real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) using the FastStart Universal SYBR Green (Roche) Master. The FastStart Universal SYBR Green (Roche) Master is supplemented with ROX reference dye for background noise correction. Each PCR reaction was carried out with gene-specific primers in a total volume of 20μL containing 10μL SYBR Green Master mix, 0.5μM gene-specific primers, and appropriately diluted cDNA. The foxtail millet actin gene SiActin was used as the internal reference [7]. All primers were annealed at 56 °C. Each PCR reaction was repeated three times independently. Relative gene expression was calculated according to the delta-delta Ct method [7]. All primers are listed in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Results

Identification and quantification of drought-responsive proteins of foxtail millet

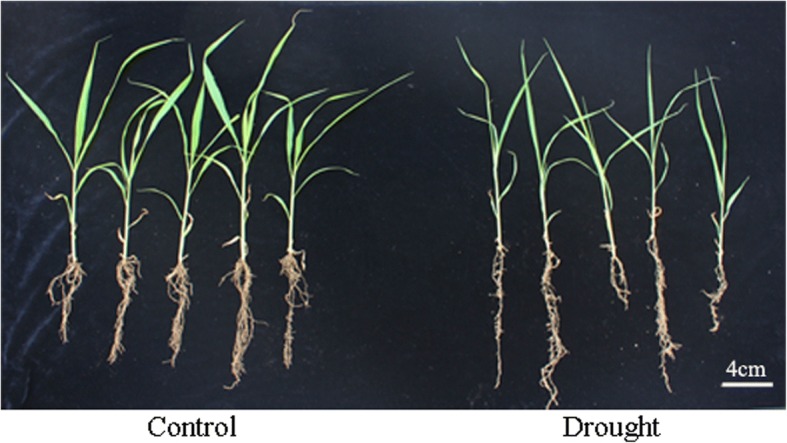

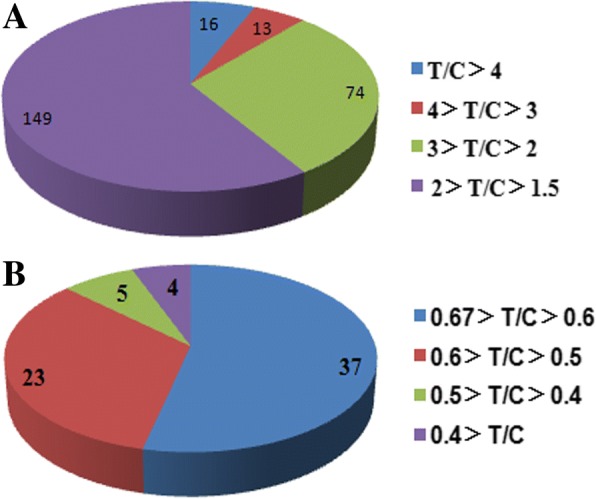

After natural drought treatment for 7 days, the foxtail millet seedlings showed stunted growth, and yellowish, wilting and curled leaves compared to those of the untreated control (Fig. 1). These seedlings were then used for quantitative proteomic analysis. A total of 4074 annotated proteins were identified in two biological replicates (Additional file 3: Table S2). Among the identified 4074 proteins, 2474 proteins were found in all four replicates and could be quantified (Additional file 4: Table S3). In published reports, the cutoff values of 1.2- to 1.5-fold change threshold and p-value (p < 0.05) was adopted [17, 23–25]. We adopted more stringently threshold of fold changes (cutoff of over 1.5 for increased expression and less than 1/1.5 (0.67) for decreased expression) and p-value<0.01 to assess significant changes according to previous report [26, 27]. With a threshold of fold changes (cutoff of over 1.5 for increased expression and less than 1/1.5 (0.67) for decreased expression) and p-value <0.01, 321 proteins with significant abundance variations were obtained, of which the abundance of 252 proteins increased while the abundance of the other 69 proteins decreased (Fig. 2, Additional file 5: Table S4). In the proteins with increased expression, 16 proteins showed increased levels of over 4 folds compared to that of the control, 87 showed increased levels between 2 and 4 folds than that of the control, and the remaining 149 proteins showed an increase of less than 2 folds. The variations of 60 decreased proteins ranged from 0.67-0.5 fold compared to that of control, while only 9 proteins among these changed by less than 0.5 fold (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The phenotype of foxtail millet seedlings under drought stress

Fig. 2.

Pie chart showing the distribution of differentially expressed proteins. T/C Ratio: relative fold change abundance of proteins in Foxtail millet under drought stress compared with control (cutoff of over 1.5 for increased expression and less than 1/1.5 (0.67) for decreased expression). a: Up-regulated proteins, b: Down-regulated proteins

Overview of quantitative proteomics analysis

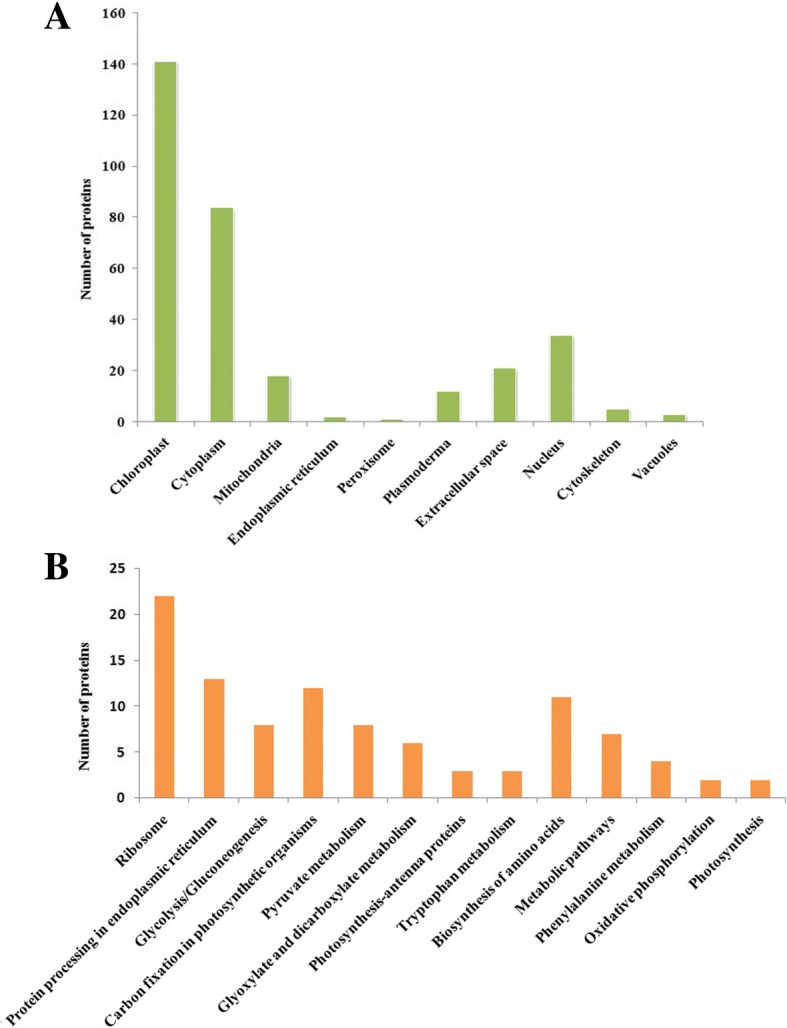

Referring to the classification criteria of the categories, these drought-responsive proteins could be further classified into different sub-categories. The subcellular localization analysis showed that these proteins were mainly localized in the chloroplast, cytoplasm, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), peroxisome, plasmodesma, extracellular space, nucleus, cytoskeleton, and vacuoles (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, about 140 proteins that accounted for 43.6% of the 32l differential proteins were mainly localized in the chloroplast. The results indicated relatively comprehensive distributions and functions of these identified proteins, and displayed the importance of chloroplast-related proteins and biological processes under drought response processes. To further investigate the pathways the identified proteins are involved in, KEGG analysis was also performed. Results suggested that these proteins were mainly enriched in ribosome-related protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, carbon fixation, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism and amino acid biosynthesis (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Categories of differentially expressed proteins. a: The subcellular localization, b: The KEGG Pathway Annotation

Network of protein-protein interaction

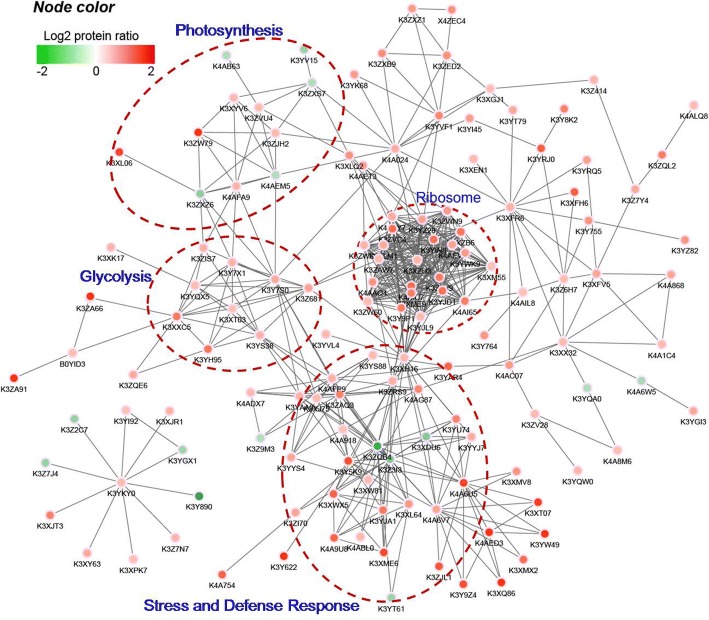

To better understand how these diverse pathways interrelate in foxtail millet under drought conditions, the protein-protein interaction network was assembled using the STRING database and Cytoscape software. As shown in the interactome figure, there are 137 nodes and 317 interactions with a combined score higher than 0.70 (Fig. 4, Additional file 6: Table S5). Four concentrated clusters, which include most of the drought responsive and interactive proteins, were highlighted by the dotted circles (Fig. 4). The functions of the proteins in these four clusters are generally focused on stress and defense response, photosynthesis, glycolysis, and protein synthesis; the abundance of most of these proteins increased, which displays the pivotal response of these proteins under drought conditions. Intensive study of the variations and correlations of these crucial nodes and their encompassed proteins in foxtail millet are undergoing.

Fig. 4.

Analysis for Protein-protein interaction network for the different expressed proteins

Functional classification of differential proteins

The identified drought-responsive proteins were further classified into seven major categories according to the functional categories [28, 29]: stress and defense response, photosynthesis, carbon metabolism, ATP synthesis, protein biosynthesis, folding and degradation, metabolism-related proteins, and cell organization-related proteins (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differentially Expressed Proteins in Foxtail millet under drought stress

| Protein accession | Protein name | T/C Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| A Stress and defense response | ||

| K3Z9P0 | late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein, group 3-like | 3.7 |

| K3XLP0 | late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein, group 3-like | 2.3 |

| K3XYM7 | late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein D-34-like | 2.3 |

| K3YJU5 | late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein D-34-like | 1.8 |

| K3ZK82 | abscisic stress-ripening protein (ASR) 2-like | 2.8 |

| K3YB35 | abscisic stress-ripening protein (ASR) | 2.0 |

| K3YAY4 | Non-specific lipid-transfer protein (nsTLP) | 8.5 |

| K3ZKC1 | Non-specific lipid-transfer protein (nsTLP) | 4.4 |

| K3XN75 | Non-specific lipid-transfer protein (nsTLP) 2B-like | 2.8 |

| K3ZKB1 | Non-specific lipid-transfer protein (nsTLP) | 2.4 |

| K3YJA1 | 14-3-3-like protein GF14-C-like | 2.4 |

| K3XL64 | 14-3-3-like protein GF14-C-like | 1.9 |

| P19860 | Bowman-Birk type major trypsin inhibitor | 4.0 |

| K4AJ19 | Bowman-Birk type trypsin inhibitor-like | 2.5 |

| K3YAC0 | Bowman-Birk type bran trypsin inhibitor-like | 1.7 |

| K3ZLV9 | cysteine proteinase inhibtor 8-like | 2.8 |

| K3ZP55 | cysteine proteinase inhibitor 8-like | 2.0 |

| K3ZRS9 | serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A | 1.7 |

| K3XH16 | DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase 20-like | 1.6 |

| K3YXA4 | defensin-like protein 2-like | 4.1 |

| K4AG87 | Superoxide dismutase (SOD) [Cu-Zn] | 2.2 |

| K3YYS4 | peroxiredoxin-2E-2, chloroplastic-like | 1.8 |

| K3XJT3 | peroxidase (POD) 72-like | 2.3 |

| K3XY63 | peroxidase (POD) 3-like | 1.7 |

| K3XJR1 | peroxidase (POD) 72-like | 1.6 |

| K3Z7N7 | peroxidase (POD) 2-like | 1.6 |

| K3YTW2 | peroxidase (POD) 2-like | 1.6 |

| K3XPK7 | peroxidase (POD) 24-like | 1.5 |

| K3XW81 | Catalase (CAT) | 1.5 |

| K4A918 | Catalase (CAT) | 1.5 |

| K4AE60 | L-ascorbate peroxidase (APX)1, cytosolic-like | 1.9 |

| K4AET3 | glutathione S-transferase (GST) F8, chloroplastic-like | 1.8 |

| K3Z9K9 | glutathione S-transferase (GST) DHAR2-like | 1.6 |

| K3YAR4 | glutaredoxin-C6-like | 2.7 |

| K3ZAQ3 | thioredoxin | 2.3 |

| K3YAA0 | thioredoxin M2, chloroplastic-like | 1.6 |

| K4AFP9 | thioredoxin F, chloroplastic-like | 1.6 |

| K3Z7G0 | aldo-keto reductase | 1.6 |

| K4AAI8 | GDP-D-mannose 3,5-epimerase (MEG) | 1.8 |

| K3XEC7 | respiratory burst oxidase homolog protein B-like | 1.6 |

| K3ZQB4 | leucine-rich repeat receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase BAM1-like | 0.3 |

| K3Z3I3 | leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase | 0.5 |

| K3YT61 | receptor-like protein kinase | 0.5 |

| K3ZRC5 | G-type lectin S-receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase | 0.5 |

| K3Y7I7 | SNF1-related protein kinase regulatory subunit gamma-1-like | 0.5 |

| K3YT86 | calcium sensing receptor, chloroplastic-like | 0.6 |

| K3XDU6 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DHX36-like | 0.5 |

| K3YDC9 | pentatricopeptide repeat-containing (PPR) protein | 0.5 |

| K3ZSE8 | pentatricopeptide repeat-containing (PPR) protein | 0.6 |

| K3YUP4 | aquaporin PIP2-4-like | 0.5 |

| K3Z2C7 | peroxidase (POD) 1-like | 0.5 |

| K3Y890 | peroxidase (POD) 1-like | 0.2 |

| K3Z7J4 | cationic peroxidase SPC4-like | 0.5 |

| B Photosynthesis | ||

| K3ZW79 | chlorophyll a-b binding protein (LHCII), 7, chloroplastic-like | 4.3 |

| K3XL06 | chlorophyll a-b binding protein (LHCII), 2, chloroplastic-like | 3.5 |

| K3ZJH2 | chlorophyll a-b binding protein (LHCII) CP26, chloroplastic-like | 1.5 |

| K3XYV6 | oxygen-evolving enhancer protein (OEE) 2, chloroplastic-like | 1.5 |

| K3Y8K2 | quinone-oxidoreductase homolog, chloroplastic-like | 2.3 |

| K3YI45 | quinone oxidoreductase-like protein, chloroplastic-like | 1.9 |

| X4ZEC4 | Cytochrome b6 | 2.0 |

| K4AFA9 | photosystem I reaction center subunit II, chloroplastic-like | 1.6 |

| K4A024 | ATP synthase subunit gamma, chloroplastic | 1.7 |

| K3ZA91 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain | 5.3 |

| K3ZA66 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain | 4.6 |

| B0YID3 | Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (Fragment) | 1.5 |

| K3Y7S0 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | 1.7 |

| K3Y7X1 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA), chloroplastic-like | 1.6 |

| K3Z3Q6 | pyruvate, phosphate dikinase (PPDK) 2 | 3.8 |

| K3ZQE6 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) 2-like | 1.7 |

| K3XFH6 | NADP-dependent Malic enzyme (ME) | 2.9 |

| K3XFV5 | NADP-dependent Malic enzyme (ME) | 1.7 |

| K3YIQ9 | carbonic anhydrase | 1.8 |

| K3XKA7 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase-like protein | 2.2 |

| K3YZ82 | ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase | 2.0 |

| K3YS88 | Thioredoxin reductase | 1.5 |

| K4A8E1 | pheophorbide a oxygenase, chloroplastic-like | 1.6 |

| K3ZVU4 | THYLAKOID FORMATION1, chloroplastic-like | 1.5 |

| K3Y6H7 | 15-cis-phytoene desaturase, chloroplastic/chromoplastic -like | 1.6 |

| K4ALQ8 | protochlorophyllide reductase | 1.5 |

| K3YV15 | chlorophyll a-b binding protein (LHCII) P4, chloroplastic-like | 0.5 |

| K4AEM5 | photosystem I reaction center subunit III, chloroplastic-like | 0.6 |

| K3ZXZ6 | photosystem I reaction center subunit psaK, chloroplastic-like | 0.5 |

| K3YI05 | phosphoenolpyruvate/phosphate translocator 2, chloroplastic-like | 0.6 |

| K3ZXS7 | thylakoid membrane phosphoprotein 14 kDa, chloroplastic-like | 0.6 |

| C Carbon metabolism | ||

| K3XK17 | fructokinase-1-like | 1.6 |

| K3YH95 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | 2.4 |

| K3YS38 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | 1.6 |

| K3ZIS7 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA) | 1.6 |

| K3XT03 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA) cytoplasmic isozyme-like | 1.5 |

| K3XXC5 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 2.4 |

| K3Z681 | enolase 2-like | 1.8 |

| K4A8I4 | multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatase 1 | 2.2 |

| K3Y755 | pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 subunit | 2.0 |

| K3Z6H7 | ATP-citrate synthase alpha chain protein 3 | 1.5 |

| K3XFR6 | ATP-citrate synthase beta chain protein 1 | 1.6 |

| K4A754 | lysosomal beta glucosidase-like | 2.7 |

| K3ZSG5 | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase | 2.2 |

| K4A2Q0 | Beta-amylase | 2.1 |

| K3YQX5 | pyrophosphate--fructose 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase subunit alpha-like | 1.5 |

| D ATP synthesis | ||

| K3YVF1 | ATP synthase subunit O, mitochondrial-like | 2.1 |

| K3Y764 | apyrase 3-like | 2.0 |

| K3YT79 | ADP,ATP carrier protein 2, mitochondrial-like | 1.7 |

| K4AIL8 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) | 1.5 |

| K3ZXB9 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit 6b-1-like | 2.1 |

| K3ZED2 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5b-1, mitochondrial-like | 2.0 |

| K3ZXZ1 | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 7 | 1.9 |

| E Protein biosynthesis, folding and degradation | ||

| K4AIU7 | 40S ribosomal protein S17-4-like | 2.6 |

| K3YLC1 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P1 | 6.6 |

| K3ZVC4 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0-like | 2.6 |

| K3YIN8 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0-like | 2.5 |

| K3YJD1 | 60S ribosomal protein L7-4-like | 2.5 |

| K3XZB6 | 60S ribosomal protein L35Ae | 2.5 |

| K3ZTV9 | 60S ribosomal protein L4-1-like | 2.3 |

| K3XME9 | 60S ribosomal protein L11-like | 2.3 |

| K3Y9P1 | 60S ribosomal protein L7-3-like | 2.3 |

| K4AI65 | 40S ribosomal protein S28-like | 2.3 |

| K3XLQ2 | 30S ribosomal protein S20 | 2.0 |

| K4AAQ4 | 60S ribosomal protein L4-1-like | 2.0 |

| K3YWK9 | 40S ribosomal protein S24 | 1.9 |

| K3YZ28 | 60S ribosomal protein L27a-2-like | 1.8 |

| K4AEV9 | 50S ribosomal protein L10, chloroplastic-like | 1.8 |

| K3XLM1 | 50S ribosomal protein L13, chloroplastic-like | 1.7 |

| K4AFY7 | 50S ribosomal protein L18, chloroplastic-like | 1.7 |

| K3XZH3 | 60S ribosomal protein L9-like | 1.6 |

| K3YJL9 | Ribosomal protein | 1.5 |

| K3ZAW7 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2B-like | 1.5 |

| K3ZW60 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | 1.5 |

| K3XM55 | 40S ribosomal protein S5-like | 1.5 |

| K3YN67 | large subunit ribosomal protein L38 | 1.5 |

| K3ZWN9 | elongation factor 1-delta 1-like | 1.9 |

| K3ZWQ4 | elongation factor 1-beta-like | 1.6 |

| K4ABL0 | transcription elongation factor A protein 3-like | 1.5 |

| K3YGI3 | glycine--tRNA ligase 1, mitochondrial-like | 1.7 |

| K3Y622 | 70 kDa peptidyl-prolyl isomerase-like | 4.6 |

| K3YU74 | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 2.2 |

| K3YYJ7 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 1.7 |

| K3YVL4 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 1.6 |

| K3XJ75 | disulfide isomerase-like 2-2-like | 1.5 |

| K3XLF8 | 16.9 kDa class Iheat shock protein 1-like | 4.7 |

| K3YW49 | 18.6 kDa class III heat shock protein-like | 4.7 |

| K4AED3 | 26.7 kDa heat shock protein, chloroplastic-like | 4.6 |

| K3XQ86 | 17.5 kDa class II heat shock protein-like | 4.2 |

| K3XT07 | 17.5 kDa class II heat shock protein-like | 3.7 |

| K3Y9Z4 | 23.2 kDa heat shock protein-like | 3.3 |

| K3Y5K9 | heat shock protein 82-like | 3.2 |

| K3ZJL1 | 21.9 kDa heat shock protein-like | 3.1 |

| K3XMX2 | 16.6 kDa heat shock protein-like | 2.6 |

| K3XMV8 | 16.9 kDa class I heat shock protein 1-like | 2.0 |

| K4A6U5 | heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein-like | 3.6 |

| K4A6V7 | heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein 2-like | 1.8 |

| K3Z4G5 | heat shock 70kDa protein | 1.8 |

| K3XFF0 | heat shock 70kDa protein | 2.0 |

| K3XWJ9 | ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN GUARD CELL 2-like | 1.9 |

| K3Z2Q9 | ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit | 1.8 |

| K3ZHP9 | Xaa-Pro aminopeptidase P-like | 1.9 |

| K3ZI70 | Carboxypeptidase | 1.8 |

| K3Z5Z6 | ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN GUARD CELL 2-like | 0.6 |

| K3Y7X0 | cysteine proteinase 1-like | 0.5 |

| K3ZUJ8 | cysteine proteinase 2-like | 0.6 |

| K3ZA06 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein L18a-like | 0.6 |

| F Metabolism-related proteins | ||

| K3YQW0 | Arginine decarboxylase | 1.6 |

| K3ZV28 | spermidine synthase 1-like | 1.5 |

| K4A8M6 | polyamine oxidase-like isoform X2 | 1.5 |

| K3Y7I4 | shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase-like | 1.5 |

| K3YKY0 | caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase-like | 1.5 |

| K3YI92 | cinnamoyl-CoA reductase 1-like | 1.5 |

| K3YI97 | O-methyltransferase ZRP4-like | 2.2 |

| K3ZIX3 | O-methyltransferase 2-like | 1.9 |

| K3XEN1 | delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS) | 1.5 |

| K3YH74 | betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH)1, chloroplastic-like | 1.5 |

| K3YRJ0 | succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial-like | 2.9 |

| K3Z7Y4 | Cysteine synthase | 1.7 |

| K3YRQ5 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase-like | 1.8 |

| K3Z414 | 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate--homocysteine methyltransferase-like | 1.6 |

| K4ADX7 | peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase A4, chloroplastic-like | 1.5 |

| K3XGJ1 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | 1.5 |

| K3XX32 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 1.5 |

| K4A868 | alanine aminotransferase 2-like | 1.7 |

| K4A1C4 | alanine aminotransferase 2 | 1.5 |

| K3XK90 | chorismate mutase 3 | 1.6 |

| K4AC07 | omega-amidase NIT2-A-like | 1.9 |

| K3YRS9 | allene oxide synthase (AOS), chloroplastic-like | 1.7 |

| K3ZV70 | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase (ACO) 1-like | 1.6 |

| K3XV98 | Lipoxygenase | 2.8 |

| K3ZI80 | patatin | 2.4 |

| K4A844 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase | 2.0 |

| K3ZQL2 | cyclopropane fatty acid synthase | 2.3 |

| K3ZQQ2 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family member 10-like | 2.3 |

| K3XGR5 | O-acyltransferase WSD1-like | 1.7 |

| K3YK68 | Acyl carrier protein | 1.9 |

| K3Z5V8 | purple acid phosphatase (PAP) 2-like | 2.7 |

| K3XZ04 | (DL)-glycerol-3-phosphatase (GPP) 2-like | 2.2 |

| K4A648 | callose synthase 10-like isoform X2 | 1.5 |

| K3ZN95 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 72B3-like | 1.6 |

| K3XWQ1 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 90A1-like | 1.5 |

| K3Z7G1 | lactoylglutathione lyase | 1.9 |

| K3Y7S6 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | 1.6 |

| K3YIW6 | lactoylglutathione lyase-like isoform X1 | 1.8 |

| K3YGX1 | 4-coumarate--CoA ligase 1-like | 0.5 |

| K3Z9M3 | methionine sulfoxide reductase B3, chloroplastic-like | 0.6 |

| K3YQA0 | primary amine oxidase-like | 0.6 |

| K4A6W5 | Asparagine synthetase | 0.6 |

| K3ZSH2 | putative amidase C869.01-like | 0.6 |

| K3XH80 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 88A1-like | 0.6 |

| K4A3F8 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 90A1-like | 0.6 |

| G Cell organization-related proteins | ||

| K4A9U8 | tubulin alpha-1 chain-like | 2.8 |

| K3XWX5 | tubulin beta-1 chain-like | 2.8 |

| H Others | ||

| K3XME6 | ADP-ribosylation factor 2-like | 3.4 |

| K3XHN1 | WD-40 repeat-containing protein MSI4-like | 1.6 |

| K4ADU6 | expansin-B3-like | 1.7 |

| K3ZVC8 | plastid-lipid-associated protein 2 | 2.4 |

| K4AB63 | plastid-lipid-associated protein 3, chloroplastic-like | 0.6 |

Protein accession: database accession numbers according to UniProt. Protein name: the function of differentially expressed proteins was annotated using the UniProt and NCBI database. T/C Ratio: relative fold change abundance of proteins in Foxtail millet under drought stress compared with control. (With a threshold of fold change (cutoff of over 1.5 for increased expression and less than 1/1.5 (0.67) for decreased expression) and T test p-value <0.01)

Proteins function in stress and defense response

Under drought stress, the abundances of multiple stress and defense response proteins changed. These proteins mainly comprise late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein, ABA-, stress-and ripening-induced (ASR) proteins, plant nonspecific lipid transfer proteins (nsLTPs), 14-3-3 proteins, plant protease inhibitors, protein phosphatases, antioxidant enzymes and aquaporin (Table 1A).

As well-known drought response proteins, the abundances of four LEA proteins and two nsLTPs (K3YAY4, K3ZKC1) showed dramatic increases. The protein abundance of 13 ROS scavenging enzymes were also found to be increased under drought (Table 1A). Another 13 proteins showed decreased abundance (Table 1A), including receptor-like protein kinase, pentatricopeptide repeat-containing (PPR) protein and aquaporin.

Photosynthesis, carbon metabolisms and ATP synthesis related proteins

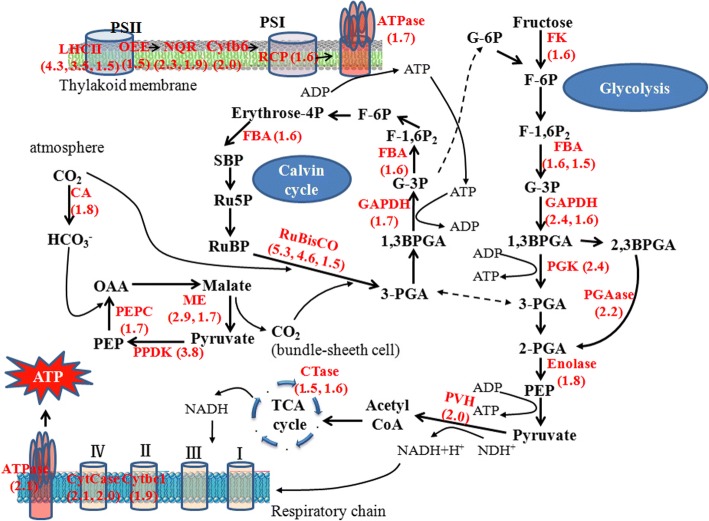

Self-protection processes, such as ROS scavenging, ion transport and osmolyte synthesis, have high ATP demands, and thus, several proteins involved in energy metabolism pathways are up-regulated under various abiotic stresses [30]. In our results, 50 such proteins related to photosynthesis, glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and ATP synthesis for energy production were detected with obvious variation in abundance (Table 1B, C and D) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of the identified the differential proteins participated energy metabolic pathways in foxtail millet seedlings under drought stress. All red words represent proteins with increased abundance and the change fold was also presented. The broken arrows indicate that there are multisteps between the two compounds. Abbreviations: F-6P: fructose-6-phosphate, F-1,6P2: fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, FBA: fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, G-3P: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, 1,3BPGA: 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, PGK: phosphoglycerate kinase, GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, 2-PGA: 2-phosphoglycerate, 3-PGA: 3-phosphoglycerate, PGAase: 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate 3-phosphatase, FK: fructokinase, RuBisCO: ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, RuBP: ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate, CA: carbonic anhydrase, PVH: Pyruvate dehydrogenase, PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate, PEPC: phosphoenolpyrovate carboxylase, NADP+/NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, ME: NADP-dependent malic enzyme, SBP: Sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphate, S7P: Sedoheptulose-7P, R5P: Ribose-5P, Ru5P: Ribulose-5P, G-6p: Glucose-6P, ADP: adenosine diphosphate, ATP: adenosine triphosphate, PSI: photosystem I, PSII: photosystem II, RCP: reaction center protein, LHCII: chlorophyll a/b binding protein, LHC: light-harvesting complex, NQR: quinone-oxidoreductase, Cytb6: Cytochrome b6, CTase: citrate synthase, CytCase: cytochrome c oxidase subunit, Cytbc1: cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit, ATPase: ATP synthase

The abundance of 14 proteins that are involved in light reaction and Calvin Cycle were dramatically increased by more than 1.5 folds, such as three chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins (LHCII), one oxygen-evolving enhancer protein (OEE), two quinine oxidoreductases, two Rubisco small chain, and so on (Table 1B) (Fig. 5). The abundances of proteins involved in CO2 assimilation also increased, including pyruvate dehydrogenase, phosphate dikinase (PPDK), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), NADP-dependent malic enzyme (NADP-ME), and carbonic anhydrase (Table 1B) (Fig. 5).

In addition to photosynthesis-related proteins, the abundances of proteins related to carbohydrate and ATP metabolism also changed. These include 11 proteins involved in glycolysis and the TCA cycle, such as two glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases (GAPDH), two fructose-bisphosphate aldolases (FBA), and two citrate synthases (Table 1C) (Fig. 5). Four proteins related to ATP metabolism, including ATP synthase subunit, apyrase, ADP/ATP carrier protein and nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK), were all increased by over 1.5 fold (Table 1C) (Fig. 5).

Proteins involved in protein biosynthesis, folding and degradation

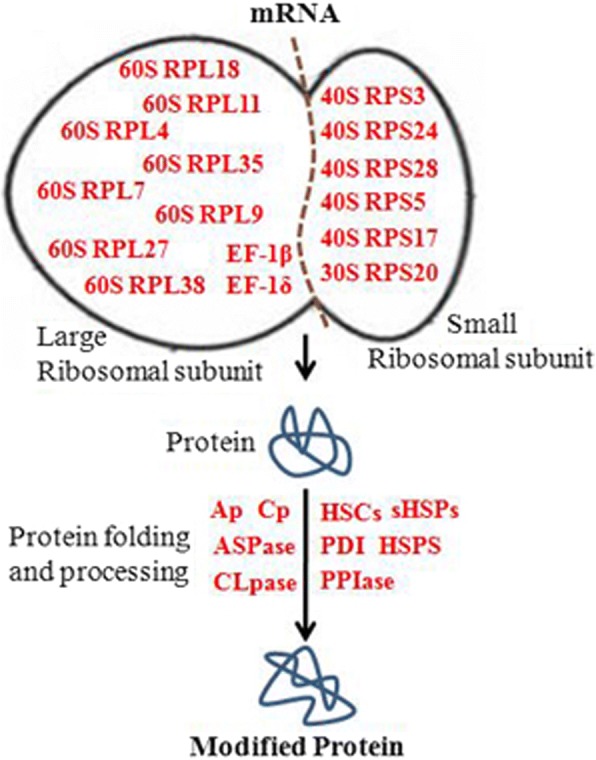

The protein synthesis machinery performs a pivotal role in stress adaptation due to its role in post-transcriptional regulation. In our research, 52 proteins with marked variation related to protein biosynthesis, folding and degradation were identified (Fig. 6). From our proteomic data, the abundance of 21 ribosomal proteins with different sizes were identified to be significantly increased under drought stress (Table 1E). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) and disulfide isomerase are involved in protein folding and modification, respectively, and were found increased in their abundance, especially one PPIase, which increased by 4.6 fold (Table 1E). Heat shock proteins (HSPs) function as molecular chaperones; six HSPs and two HSC70 proteins showed significant accumulation in foxtail millet under drought stress (Table 1E). In addition, aspartic protease, Clp protease proteolytic subunit, aminopeptidase, and carboxypeptidase, which are responsible for removing modified, abnormal, and mistargeted proteins by proteolysis, were also up-regulated under drought stress (Table 1E) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram of the identified the differential proteins participated protein biosynthesis, folding and degradation pathway in foxtail millet seedlings under drought stress. All red words represent proteins with increased abundance. Abbreviations: PDI: protein disulfide isomerase like protein, 40SRP: 40S ribosomal protein S6, HSC: heat shock cognate, HSP: heat shock protein, PPIase: Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase, sHSPs: small HSPs, PDI: protein disulfide isomerase, ASPase: aspartic protease, CLpase: Clp protease proteolytic subunit, Ap: aminopeptidase, Cp: carboxypeptidase

Metabolism-related proteins

In this research, the detected differential proteins were found to occupy a wide variety of metabolic pathways including polyamine metabolism, lignin biosynthesis, amino acid metabolism, secondary metabolism, hormone metabolism, and lipid and fatty acid metabolism (Table 1F). Here, three key enzymes involved in PA metabolism, such as arginine decarboxylase, spermidine synthase, and polyamine oxidase, and three proteins related to lignin biosynthesis, such as shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyl transferase, caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, were all found to be increased in abundance after drought treatment (Table 1F). In addition, the proteins related to phosphorus metabolism, such as purple acid phosphatase (PAP), (DL)-glycerol-3-phosphatase (GPP), and callose synthase, also accumulated in foxtail millet under drought stress (Table 1F).

Cell organization-related proteins

Microtubules (MTs) are one of the two key components in the eukaryotic cytoskeleton. The arrangements and stabilities of MTs are related to the stress resistance and tolerance of plants [31]. In foxtail millet, two proteins identified as tubulin α-1 chain and tubulin β-1 chain were both up-regulated by 2.8 folds (Table 1G). The increased abundance of α/β-tubulin in foxtail millet may affect polymerization and alignment of MTs, and further affect cell stability and plant resistance in response to drought.

Other proteins changed under drought

In our proteomic analysis, other proteins, which have been reported to be involved in abiotic stress response, were also identified (Table 1H). The ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF), which plays critical roles in membrane trafficking, was increased by 3.4 folds in abundance when plants were stressed. The abundance of WD40 proteins and Expansins (EXP), which act as scaffolding molecules and mediate cell-wall loosening and extension, respectively, were increased by 1.6 folds in abundance (Table 1H). Plastid lipid-associated proteins (PAP) are amphipathic proteins and regulated by various abiotic stressors. Two PAPs with opposite accumulation trends were also identified (Table 1H).

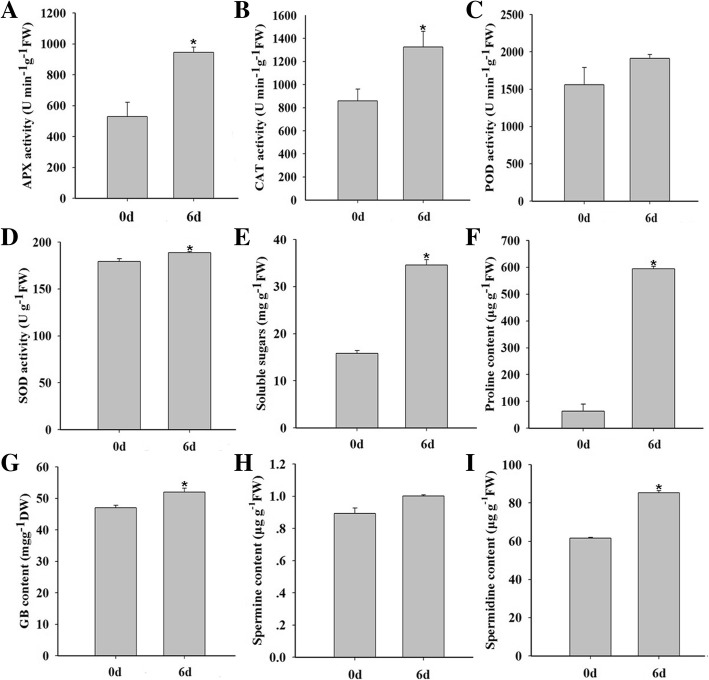

Variation of physiological parameters

To further elucidate the molecular mechanism of drought tolerance in foxtail millet, physiological parameters, including antioxidant enzymes, the content of soluble sugar, proline, GB and polyamines, were measured. As shown in Fig. 7, after drought treatment, the activities of L-ascorbate peroxidase (APX), peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) were increased 78%, 54% and 22%, respectively, compared with those of the control. There was only a slight increase in superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. The enhanced activities of these antioxidant enzymes were consistent with the accumulation of the corresponding proteins in our proteomics data (Table 1A). The contents of proline and soluble sugars were about 9 and 2 folds higher than those of the control under drought respectively, and the GB content was also up-regulated. The spermine and spermidine levels in foxtail millet seedlings also increased by 12% and 38% under drought treatment, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Physiologic parameters measurement in foxtail millet under drought stress. Total activity of the antioxidant enzymes APX (a), CAT (b), POD (c) and SOD (d) in foxtail millet under drought stress. The content of soluble sugare (e), proline (f), GB (g), spermine (h) and spermidine (i) in foxtail millet under drought stress

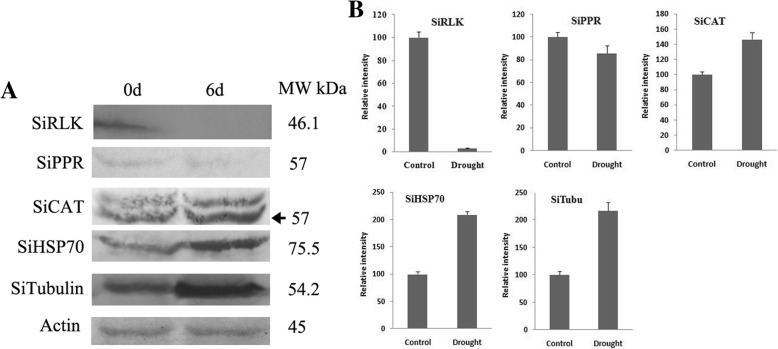

Validation of differential proteins by western blot

In order to validate the content variation of proteins identified in the proteomic analysis, five proteins including SiRLK (K3ZRC5), SiPPR (K3YDC9), SiCAT (K4A918), SiHSP70 (K4A6V7) and SiTubulin (K4A9U8) were randomly picked for western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 8, drought stress could significantly induce the accumulation of SiCAT, SiHSP70 and SiTubulin, and obviously reduce the enrichment of SiRLK. The expression of SiPPR was slightly decreased in the drought treatment. The variation trends of these proteins under drought stress were in good accordance with the proteomic analysis results.

Fig. 8.

Western blot of selected drought-responsive proteins in foxtail millet. Five proteins including SiRLK(K3ZRC5), SiPPR (K3YDC9), SiCAT (K4A918), SiHSP70 (K4A6V7) and tubulin (K4A9U8) were chosen for western blot analysis. The SiActin was used as the internal control to confirm the same total protein loading quantity of different samples. a: The result of western blot, b: Quantitative analysis of protein change using Image J

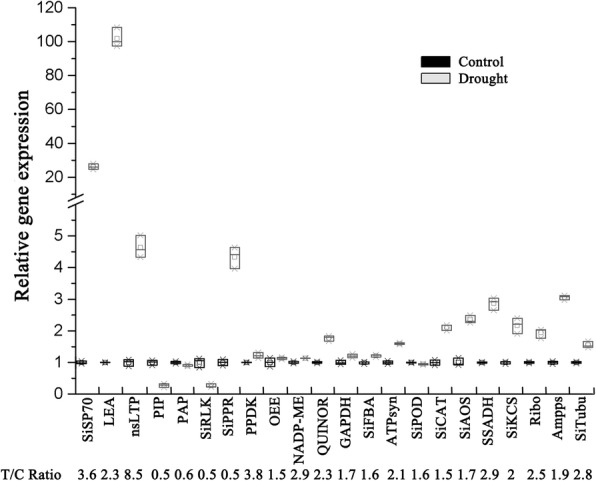

Transcriptional analysis of drought-responsive proteins

To explore the correlation between translation and transcription of the differential proteins and their coding genes during drought stress in foxtail millet, 22 differential proteins were randomly selected and qRT-PCR was conducted (Fig. 9). Of these 22 proteins, only eight proteins (PIP (K3YUP4), PAP (K4AB63), SiRLK (K3ZRC5), SiCAT (K4A918), SiAOS (K3YRS9), SSADH (K3YRJ0), SiKCS (K4A844), and Ribo (K3YJD1)) were positively correlated with their corresponding coding genes. Other proteins showed loosely correlated post-transcriptional and post-translational levels. As shown in Fig. 9, mRNA levels of HSP70 and LEA were significantly increased by more than 25-fold after drought treatment, but their corresponding proteins were only increased by 3.3 and 2.3-fold, respectively. The post-transcriptional level nsLTP was up-regulated by 4.6 folds, but the abundance of its protein was increased by 8.5 folds. Other genes, such as PPDK (K3Z3Q6), OEE (K3XYV6), NADP-ME (K3XFH6), QUINOR (K3Y8K2), GAPDH (K3Y7S0), SiFBA (K3Y7X1), ATPsyn (K3YVF1), SiPOD (K3XJR1) and SiTubu (K4A9U8), showed no significant changes at the transcriptional level, even though they displayed differential expression profiles at the post-translational level. Furthermore, the expression pattern of PPR even exhibited an opposite trend compared to its coding protein under drought stress.

Fig. 9.

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression patterns in Foxtail millet under drought stress. CK: control treatment. The SiActin gene was used as the internal control. The relative fold change abundance of corresponding proteins identified under drought stress compared with control treatment was presented in bottom line. NADP-ME: NADP-dependent malic enzyme, SiCAT: Catalase, SiLEA: late embryogenesis abundant protein, SiOEE: oxygen-evolving enhancer protein, GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, SiFBA: fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, QUINOR: quinone-oxidoreductase homolog, HSP70: heat shock protein, nsLTP: non-specific lipid-transfer protein, PPR: pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein, Ribo: 60S ribosomal protein, SSADH: succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, AOS: allene oxide synthase, PIP: aquaporin, ATPsyn: ATP synthase subunit O, PPDK: pyruvate, phosphate dikinase, Ampps: Xaa-Pro aminopeptidase, Tubu: tubulin, KCS: 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase, PAP: plastid-lipid-associated protein, SiRLK: receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase

Discussion

Drought stress is one of major constraints limiting crop production worldwide. This multidimensional stress causes changes in the physiological, morphological, biochemical, and molecular traits in plants. Many plants have evolved intricate resistance mechanisms to tolerate drought stress. However, these mechanisms are varied from plant species to species. Foxtail millet, as an extremely drought tolerant and resistant grain crop, has been proposed as a novel model species for functional genomic study and drought tolerance investigation [15, 32].

More and more research in foxtail millet subjected to drought stress demonstrate that functional proteins play key roles in stress response [33, 34]. Previous transcriptomic study suggested that an elaborate regulatory network positively regulated foxtail millet in response to drought. This network involved multiple biological processes and pathways, which included signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, redox regulation, photosynthesis, and osmotic adjustment [35]. However, The alterations in protein expression, along with the physiological variations occurring in foxtail millet under drought stress still require extensive and intensive research. In our study, 321 proteins that respond to drought were identified, and functional analysis revealed that these proteins were involved in stress response, photosynthetic and metabolic pathways (Table 1), indicating that multiple sophisticated mechanisms worked together to reestablish a new cellular homeostasis under drought stress.

LEA proteins are highly hydrophilic and thermally stable, the accumulation of LEA proteins may protect cellular structures from injuries by maintaining orderly structures within the cell [36]. Aquaporins are conserved integral membrane proteins that are involved in plant water uptake [37]. The decrease of aquaporin K3YUP4 under drought may be beneficial to reduce membrane water permeability, and promote cellular water conservation.

The antioxidant defense system in plants under drought stress is composed of ROS scavenging enzymes. Among them, CAT, SOD, APX, and GPx are essential to remove ROS and act synergistically to counteract oxidative damage caused by drought stress [38]. In our results, the abundance of 13 ROS scavenging enzymes and activities of APX, POD, CAT and SOD increased (Table 1A and Fig. 7), all of which could enhance drought resistance in foxtail millet

The abundance of ribosomal proteins, protein chaperones, and proteases were all changed significantly, all of which perform pivotal roles in protein synthesis and modification, aiding in stress adaptation. From our data, 21 ribosomal proteins were identified to be significantly increased under drought (Table 1E, Fig. 5). Similar results have also been reported in cucumber and maize under stres [39]. HSPs and HSC70 were identified to be significant accumulated which could aid in maintaining protein homeostasis and promoting refolding of denatured proteins under drought (Table 1E) [40, 41]. The four proteases, which could participate in proteins modification and correstions, were also be identified accumulated under drought (Table 1E). These differential proteins and response mechanisms are consistent with previous studies in Arabidopsis under salt stress [42].

The maintenance of photosynthetic rates under drought stress is essential for drought tolerance in crops [43]. Here the increase in multiple light reaction-related proteins and Calvin Cycle-related proteins (K3ZA91 and K3ZA66) were identified (Fig. 5) [44]. Previously reported that drought stress could lead to a reduction in internal CO2 concentration due to stomatal closure [44]. The increase in the CO2 assimilation-related proteins may facilitate CO2 concentration and assimilation, and in turn contribute to maintain higher photosynthetic rate in foxtail millet under drought stress (Table 1B) (Fig. 5).

The glycolytic pathway has also been reported to respond to drought. In our results, the expression of fructokinase was up-regulated 1.6 fold, and the amounts of related enzymes were all increased, which indicates a potential increased flux of carbohydrates to the TCA cycle (Table 1C) (Fig. 5) [39, 45, 46]. This is further supported by the increase we saw in pyruvate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase; pyruvate dehydrogenase catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA and NADH and links the glycolysis pathway to the TCA cycle, and citrate synthase catalyzes the first step of the TCA cycle. The results indicate an acceleration of carbon metabolism, which would provide more energy for stress resistance [28]. The enhanced energy production resulted in decreaesd carbohydrate synthesis, which leaded to a reduction in biomass under drought stress.

The reversible protein phosphorylation regulated by kinase and phosphatase is fundamental for many signaling pathways of various stress-related biological processes [47]. Our study detected the variation of one serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A and four receptor-like protein kinases (Table 1A). Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A is significant in its role as a regulator for microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). This, taken along with the increase in α/β-tubulin, suggests that the phosphorylation and stabilizing microtubules are key factors in drought response of foxtail millet [48].

Abundance of proteins belonging to different metabolic pathways, including polyamine metabolism, lignin biosynthesis, fatty acid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, hormone metabolism and nucleotide metabolism (Table 1F), were also affected under drought [49]. In the abiotic stress response, polyamines, ROS (H2O2) and NO act synergistically in promoting ABA responses in guard cells [21, 50, 51]. In our study, three key enzymes involved in PA metabolism were found to be accumulated (Table 1F). The increase in PA synthetases were consistent with the accumulation of polyamines (Fig. 6).

Osmotic regulated substances, such as proline and GB, could improve water uptake from drying soil and protect cell metabolism by balancing the osmotic pressure and maintaining cell turgor in plant cells during drought [52, 53]. Delta-1-pyrroline 5-carboxylase synthetase (P5CS) (K3XEN1) and betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH) (K3YH74), which catalyze the rate-limiting steps of proline and glycinebetaine (GB) biosynthesis respectively, were both significantly up-regulated to deal with osmotic stress caused by drought (Table 1F).

Lignin is a basic component of the plant secondary cell wall, and the lignin content and composition changed during abiotic and biotic stresses [54]. Here, three proteins related to lignin biosynthesis such as shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyl transferase, caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase were found to be increased, while only one protein, 4-coumarate--CoA ligase, was reduced under drought (Table 1F). Very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) are important components of the protective barrier present at the plant-environment interface [55]. 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCS), which is responsible for VLCFA synthesis, was found to be up-regulated about two folds after drought treatment. A cyclopropane fatty acid synthase was also increased 2.3 folds (Table 1F). Previous evidence has suggested that the existence of a cyclopropane ring within membrane fatty acids could enhance the stability of biological membranes [56]. NsLTPs are soluble, small, basic proteins in plants, which have been reported to be involved in catalyzing the transfer of phospholipids and play an important role in plant defense and stress responses [57]. Our results suggest a very important role of lipid metabolism in drought tolerance of foxtail millet, which could also explain the dramatic increase of nsLTP (K3YAY4) under drought. Further in-depth study will help to understand how lipids function in the stress-resistance mechanisms in foxtail millet.

The plant hormones, especially jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ETH), are important signaling molecules and play critical roles in mediating biotic/abiotic stress responses in plants [58]. In this research, the key enzymes of allene oxide synthase (AOS) (K3YRS9) and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase (ACO) (K3ZV70), which catalyze the first and final step of JA and ETH biosynthesis respectively, were all increased in abundance under drought (Table 1F). These results further proved that the phytohormone metabolic pathway also participates in stress responsive processes.

We also performed correlated analysis of transcriptomics−proteomics, in which the corresponding transcripts of only 23 differential proteins were identified in our proteomics study (Additional file 7: Table S6) [15]. The weak correlation between the transcriptomic and proteomic data was consistent with the results of previous reports in other species. As protein isoforms and their abundances are not only regulated at the transcription level, but also at post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels. The results confirmed the formerly established perception that transcription levels are not directly correlated with protein expression levels [14, 28, 39, 46], and post-transcriptional regulation performs a vital role in gene expression [59].

It could be concluded from this study that the proteins that participated in energy metabolism and protective materials synthesis were obviously changed, and the contents of most of them were enhanced dramatically. These changes further contribute to protect plant cells avoiding water defect damage, and maintain growth of foxtail millet under drought. These were consistent with previous proteomic studies of drought tolerant genotype plants under drought [43].

In all, the proteomic profiling obtained in this research has offered comprehensive insights into the various mechanisms of drought tolerance in foxtail millet, and more detailed studies are needed to determine the key proteins and pathways of plants under stress.

Conclusions

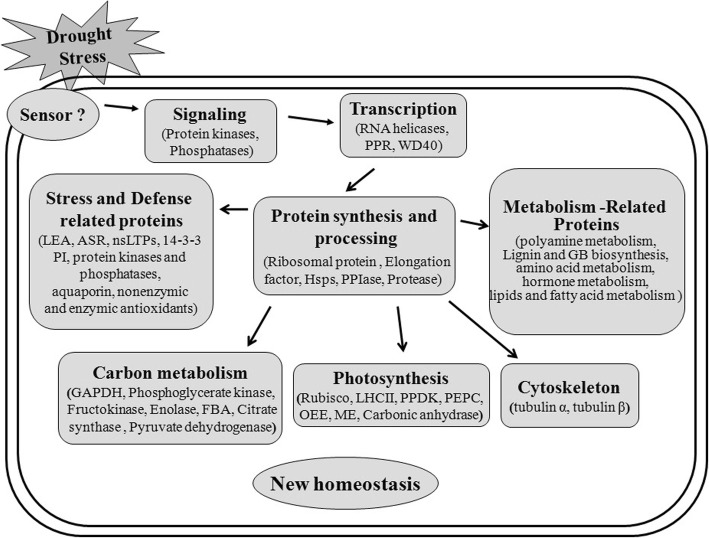

In this report, quantitative proteomic analysis was employed and a series of comprehensive proteomic data of foxtail millet under drought stress was obtained. Among the identified proteins, 252 up-regulated proteins showed more than a 1.5-fold change and 69 proteins showed less than 0.67-fold change in abundance. These proteins were further classified into a broad range of biological processes, particularly participation in stress and defense responses, photosynthesis, carbon metabolism, protein synthesis and various metabolic processes. Drought signals are perceived and transmitted into the cell, which is mediated by putative sensors and signal transduction mechanisms. Through post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational regulation, the abundance and activities of functional proteins involved in stress and defense responses, energy pathways and a variety of metabolic pathways were changed to reestablish a new cellular homeostasis under drought stress (Fig. 10). Notably, most of the proteins identified in this work have previously been found to participate in responses to and be regulated by drought and other abiotic stresses. Western blot and qRT-PCR were performed to analyze the accumulation and expression of proteins and mRNA of the selected proteins, respectively. Stress related physiological parameters, such as antioxidant enzymes, the content of soluble sugar, proline, GB and polyamines, were also detected for foxtail millet after drought treatment.

Fig. 10.

A simple model of the drought stress responses in foxtail millet. Foxtail millet can perceive duought stress signals by putative sensors and transmit them to the cellular machinery by signal transduction to regulate gene expression. Through regulation of transcription, protein synthesis and processing, the abundance and activities of functional proteins involved in stress and defense response, energy pathways and a variety of metabolism pathways were changed. These processes might work cooperatively to establish a new cellular homeostasis under drought stress

The proteome profiling obtained in this research has offered comprehensive insights into the various mechanisms of drought tolerance in foxtail millet. The identified differential proteins are candidate resources for the millet research community in selecting proteins for further stress-tolerant germplasm innovation and cultivation.

Additional files

Figure S1. The RNA Electropherogram. 1μg of total RNA was separated by denaturing 1.0% (w/v) agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide. Total RNA was isolated from foxtail millet seedlings, 1: Control treatment, 2: drought treatment, M: DNA Maker. (JPG 21 kb)

Table S1. Oligonucleotide primers used in qRT-PCR in this study. (DOC 98 kb)

Table S2. List of annotation all 4075 identified proteins. (XLSX 1117 kb)

Table S3. List of 2474 quantified proteins were found in all four replicates in foxtail millet after drought treatment. (XLS 97 kb)

Table S4. List of 321 differentially expressed proteins in foxtail millet after drought treatment. (XLSX 23 kb)

Table S5. The parameters of Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) Networks (XLSX 118 kb)

Table S6. Comparative analysis the transcriptome and proteome data in foxtail millet after drought treatment. (XLSX 17 kb)

Acknowledgments

None

Funding

This work was supported by Shandong Provential Natural Science Foundtion (No. ZR2016CM23), the Young Talents Training program of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2016-2018), the Major in Shandong Province Science and Technology Projects (2015ZDJS03001-2), the Shandong Key Research and Development Program (2016ZDJS10A03-05) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31401310), The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Availability of data and materials

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD008176 ( http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride).

Abbreviations

- APX

Ascorbate peroxidase

- CAT

Catalases

- FA

Formic acid

- FBA

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GB

Glycine betaine

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GPP

(DL)-glycerol-3-phosphatase

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- MT

Microtubule

- NDPK

Nucleoside diphosphate kinase

- OEE

Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein

- PAP

Purple acid phosphatase

- POD

Peroxidase

- PPIase

Peptidyl-prolylcis/transisomerase

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

Authors’ contributions

JWP and WL designed the study and supervised the experiments. ZL, QGW and ML performed the experiments. JWP, WL, YAG and AKG analyzed the data, JWP and WL wrote the manuscript, WL and WQZ reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jiaowen Pan, Email: jwpan01@126.com.

Zhen Li, Email: lizhen1891@126.com.

Qingguo Wang, Email: wangqingguo1963@163.com.

Anna K. Garrell, Email: agarrell@boragenbio.com

Min Liu, Email: jnlium@sina.com.

Yanan Guan, Email: yguan65@163.com.

Wenqing Zhou, Email: Alica.Wenqing@gmail.com.

Wei Liu, Email: wheiliu@163.com.

References

- 1.Lata C, Gupta S, Prasad M. Foxtail millet: a model crop for genetic and genomic studies in bioenergy grasses. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2013;33(3):328–343. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2012.716809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu H, Zhang J, Liu KB, Wu N, Li Y, Zhou K, Ye M, Zhang T, Zhang H, Yang X, et al. Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(18):7367–7372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900158106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang G, Liu X, Quan Z, Cheng S, Xu X, Pan S, Xie M, Zeng P, Yue Z, Wang W, et al. Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):549–554. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doust AN, Kellogg EA, Devos KM, Bennetzen JL. Foxtail millet: a sequence-driven grass model system. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(1):137–141. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennetzen JL, Schmutz J, Wang H, Percifield R, Hawkins J, Pontaroli AC, Estep M, Feng L, Vaughn JN, Grimwood J, et al. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):555–561. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puranik S, Bahadur RP, Srivastava PS, Prasad M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a membrane associated NAC family gene, SiNAC from foxtail millet [Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv] Mol Biotechnol. 2011;49(2):138–150. doi: 10.1007/s12033-011-9385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra AK, Muthamilarasan M, Khan Y, Parida SK, Prasad M. Genome-wide investigation and expression analyses of WD40 protein family in the model plant foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) PloS One. 2014;9(1):e86852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu C, Ming C, Zhao-Shi X, Lian-Cheng L, Xue-Ping C, You-Zhi M. Characteristics and Expression Patterns of the Aldehyde Dehydrogenase (ALDH) Gene Superfamily of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) PloS One. 2014;9(7):e101136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lata C, Bhutty S, Bahadur RP, Majee M, Prasad M. Association of an SNP in a novel DREB2-like gene SiDREB2 with stress tolerance in foxtail millet [Setaria italica (L.)] J Exp Bot. 2011;62(10):3387–3401. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng Y, Zhang J, Cao G, Xie Y, Liu X, Lu M, Wang G. Overexpression of a PLDalpha1 gene from Setaria italica enhances the sensitivity of Arabidopsis to abscisic acid and improves its drought tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29(7):793–802. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0865-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Liu T, Fu J, Zhu Y, Jia J, Zheng J, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Wang G. Construction and application of EST library from Setaria italica in response to dehydration stress. Genomics. 2007;90(1):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Tang S, Jia G, Schnable JC, Su H, Tang C, Zhi H, Diao X. The C-terminal motif of SiAGO1b is required for the regulation of growth, development and stress responses in foxtail millet (Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv) J Exp Bot. 2016;67(11):3237–3249. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi X, Xie S, Liu Y, Yi F, Yu J. Genome-wide annotation of genes and noncoding RNAs of foxtail millet in response to simulated drought stress by deep sequencing. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;83(4-5):459–473. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng BB, Fang YN, Pan ZY, Sun L, Deng XX, Grosser JW, Guo WW. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis revealed alterations of carbohydrate metabolism pathways and mitochondrial proteins in a male sterile cybrid pummelo. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(6):2998–3015. doi: 10.1021/pr500126g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang S, Li L, Wang Y, Chen Q, Zhang W, Jia G, Zhi H, Zhao B, Diao X. Genotype-specific physiological and transcriptomic responses to drought stress in Setaria italica (an emerging model for Panicoideae grasses) Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10009. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08854-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazargani MM, Sarhadi E, Bushehri AA, Matros A, Mock HP, Naghavi MR, Hajihoseini V, Mardi M, Hajirezaei MR, Moradi F, et al. A proteomics view on the role of drought-induced senescence and oxidative stress defense in enhanced stem reserves remobilization in wheat. J Proteomics. 2011;74(10):1959–1973. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J, Lan H, Fang H, Huang X, Zhang H, Huang J. Quantitative proteomic analysis of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) salt response. PloS One. 2015;10(3):e0120978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan J, Ye Z, Cheng Z, Peng X, Wen L, Zhao F. Systematic analysis of the lysine acetylome in Vibrio parahemolyticus. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(7):3294–3302. doi: 10.1021/pr500133t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan J, Zhang M, Kong X, Xing X, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Liu Y, Sun L, Li D. ZmMPK17, a novel maize group D MAP kinase gene, is involved in multiple stress responses. Planta. 2012;235(4):661–676. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang C, Zhou Y, Fan J, Fu Y, Shen L, Yao Y, Li R, Fu S, Duan R, Hu X, et al. SpBADH of the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum strongly confers drought tolerance through ROS scavenging in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;96:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fincato P, Moschou PN, Spedaletti V, Tavazza R, Angelini R, Federico R, Roubelakis-Angelakis KA, Tavladoraki P. Functional diversity inside the Arabidopsis polyamine oxidase gene family. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(3):1155–1168. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang QS, Wu JH, Li CY, Wei YR, Sheng O, Hu CH, Kuang RB, Huang YH, Peng XX, McCardle JA, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals that antioxidation mechanisms contribute to cold tolerance in plantain (Musa paradisiaca L.; ABB Group) seedlings. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11(12):1853–1869. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.022079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu M, Dai S, Zhu N, Booy A, Simons B, Yi S, Chen S. Methyl jasmonate responsive proteins in Brassica napus guard cells revealed by iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(7):3728–3742. doi: 10.1021/pr300213k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lan P, Li W, Wen TN, Shiau JY, Wu YC, Lin W, Schmidt W. iTRAQ protein profile analysis of Arabidopsis roots reveals new aspects critical for iron homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(2):821–834. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.169508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Liang W, Xing J, Tan F, Chen Y, Huang L, Cheng CL, Chen W. Dynamics of chloroplast proteome in salt-stressed mangrove Kandelia candel (L.) Druce. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(11):5124–5136. doi: 10.1021/pr4006469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu H, Ren JM, Jia X, Levy T, Rikova K, Yang V, Lee KA, Stokes MP, Silva JC. Quantitative Profiling of Post-translational Modifications by Immunoaffinity Enrichment and LC-MS/MS in Cancer Serum without Immunodepletion. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(2):692–702. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O115.052266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi H, Wang X, Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Chan Z. Comparative physiological and proteomic analyses reveal the actions of melatonin in the reduction of oxidative stress in Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon (L). Pers.) J Pineal Res. 2015;59(1):120–131. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W, Wei Z, Qiao Z, Wu Z, Cheng L, Wang Y. Proteomics analysis of alfalfa response to heat stress. PloS One. 2013;8(12):e82725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevan M, Bancroft I, Bent E, Love K, Goodman H, Dean C, Bergkamp R, Dirkse W, Van Staveren M, Stiekema W, et al. Analysis of 1.9 Mb of contiguous sequence from chromosome 4 of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1998;391(6666):485–488. doi: 10.1038/35140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huerta-Ocampo JA, Barrera-Pacheco A, Mendoza-Hernandez CS, Espitia-Rangel E, Mock HP. Barba de la Rosa AP: Salt stress-induced alterations in the root proteome of Amaranthus cruentus L. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(8):3607–3627. doi: 10.1021/pr500153m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, Ji S, Fang X, Wang Q, Li Z, Yao F, Hou L, Dai S. Protein Kinase LTRPK1 Influences Cold Adaptation and Microtubule Stability in Rice. J Plant Growth Regul. 2013;32(3):483–490. doi: 10.1007/s00344-012-9314-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashraf M. Inducing drought tolerance in plants: recent advances. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28(1):169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirayama T, Shinozaki K. Research on plant abiotic stress responses in the post-genome era: past, present and future. Plant J. 2010;61(6):1041–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi W, Cheng J, Wen X, Wang J, Shi G, Yao J, Hou L, Sun Q, Xiang P, Yuan X, et al. Transcriptomic studies reveal a key metabolic pathway contributing to a well-maintained photosynthetic system under drought stress in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) Peer J. 2018;6:e4752. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Wang L, Xing X, Sun L, Pan J, Kong X, Zhang M, Li D. ZmLEA3, a multifunctional group 3 LEA protein from maize (Zea mays L.), is involved in biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54(6):944–959. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang HY, Yang SW, Carlson JE, Ku YG, Ahn SJ. Two aquaporins of Jatropha are regulated differentially during drought stress and subsequent recovery. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170(11):1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Damage, and Antioxidative Defense Mechanism in Plants under Stressful Conditions. J Botany. 2012;2012:1–26. doi: 10.1155/2012/217037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du CX, Fan HF, Guo SR, Tezuka T, Li J. Proteomic analysis of cucumber seedling roots subjected to salt stress. Phytochem. 2010;71(13):1450–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heidarvand L, Maali Amiri R. What happens in plant molecular responses to cold stress? Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32(3):419–431. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0451-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun L, Liu Y, Kong X, Zhang D, Pan J, Zhou Y, Wang L, Li D, Yang X. ZmHSP16.9, a cytosolic class I small heat shock protein in maize (Zea mays), confers heat tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31(8):1473–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pang Q, Chen S, Dai S, Chen Y, Wang Y, Yan X. Comparative proteomics of salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana and Thellungiella halophila. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(5):2584–2599. doi: 10.1021/pr100034f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Cai X, Xu C, Wang Q, Dai S. Drought-Responsive Mechanisms in Plant Leaves Revealed by Proteomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(10):1706. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamori W, Hikosaka K, Way DA. Temperature response of photosynthesis in C3, C4, and CAM plants: temperature acclimation and temperature adaptation. Photosynth Res. 2014;119(1-2):101–117. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9874-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xue GP, McIntyre CL, Jenkins CL, Glassop D, van Herwaarden AF, Shorter R. Molecular dissection of variation in carbohydrate metabolism related to water-soluble carbohydrate accumulation in stems of wheat. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(2):441–454. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan X, Zhu B, Zhu H, Chen Y, Tian H, Luo Y, Fu D. iTRAQ protein profile analysis of tomato green-ripe mutant reveals new aspects critical for fruit ripening. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(4):1979–1993. doi: 10.1021/pr401091n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luan S. Protein phosphatases in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:63–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartels S, Gonzalez Besteiro MA, Lang D, Ulm R. Emerging functions for plant MAP kinase phosphatases. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(6):322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng D, Wang X, Li Z, Zhang Y, Peng Y, Li Y, He X, Zhang X, Ma X, Huang L, et al. NO is involved in spermidine-induced drought tolerance in white clover via activation of antioxidant enzymes and genes. Protoplasma. 2016;253(5):1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0880-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alcazar R, Altabella T, Marco F, Bortolotti C, Reymond M, Koncz C, Carrasco P, Tiburcio AF. Polyamines: molecules with regulatory functions in plant abiotic stress tolerance. Planta. 2010;231(6):1237–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wimalasekera R, Schaarschmidt F, Angelini R, Cona A, Tavladoraki P, Scherer GF. POLYAMINE OXIDASE2 of Arabidopsis contributes to ABA mediated plant developmental processes. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;96:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan W, Zhang M, Zhang H, Zhang P. Improved tolerance to various abiotic stresses in transgenic sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) expressing spinach betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase. PloS One. 2012;7(5):e37344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayat S, Hayat Q, Alyemeni MN, Wani AS, Pichtel J, Ahmad A. Role of proline under changing environments: a review. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7(11):1456–1466. doi: 10.4161/psb.21949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moura JC. Bonine CA, de Oliveira Fernandes Viana J, Dornelas MC, Mazzafera P: Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010;52(4):360–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joubes J, Raffaele S, Bourdenx B, Garcia C, Laroche-Traineau J, Moreau P, Domergue F, Lessire R. The VLCFA elongase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana: phylogenetic analysis, 3D modelling and expression profiling. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;67(5):547–566. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li C, Zhao J-L, Wang Y-T, Han X, Liu N. Synthesis of cyclopropane fatty acid and its effect on freeze-drying survival of Lactobacillus bulgaricus L2 at different growth conditions. World J Microb Biot. 2009;25(9):1659–1665. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-0060-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin KF, Liu YN, Hsu ST, Samuel D, Cheng CS, Bonvin AM, Lyu PC. Characterization and structural analyses of nonspecific lipid transfer protein 1 from mung bean. Biochem. 2005;44(15):5703–5712. doi: 10.1021/bi047608v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen D, Ma X, Li C, Zhang W, Xia G, Wang M. A wheat aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase gene, TaACO1, negatively regulates salinity stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2014;33(11):1815–1827. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang Y, Yang B, Harris NS, Deyholos MK. Comparative proteomic analysis of NaCl stress-responsive proteins in Arabidopsis roots. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(13):3591–3607. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials