Abstract

Background

Glioma patients suffer from a wide range of symptoms which influence quality of life negatively. The aim of this review is to give an overview of symptoms most prevalent in glioma patients throughout the total disease trajectory, to be used as a basis for the development of a specific glioma Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) for early assessment and monitoring of symptoms in glioma patients.

Methods

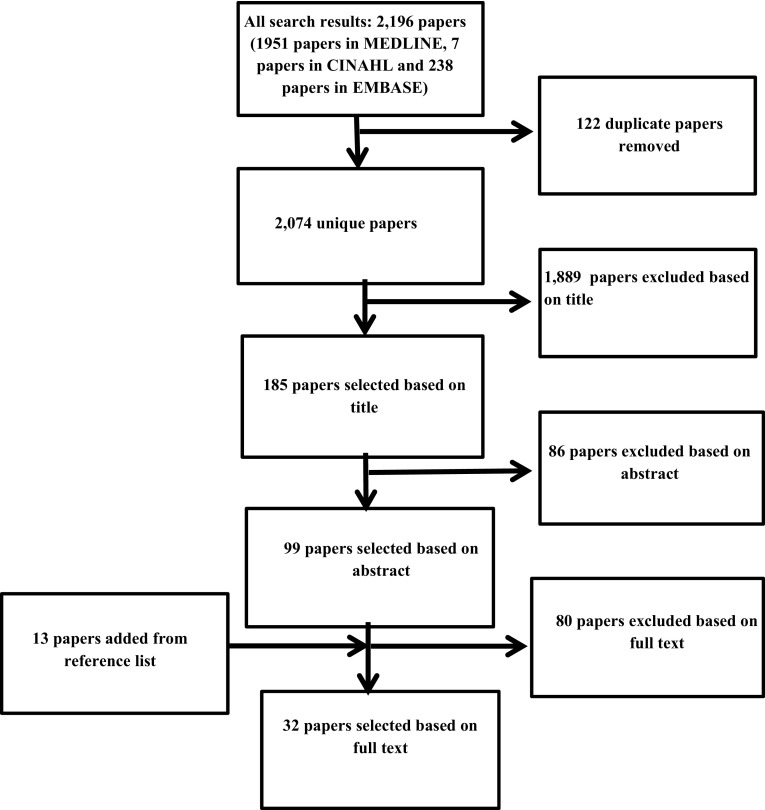

A systematic review focused on symptom prevalence in glioma patients in different phases of disease and treatment was performed in MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE according to PRISMA recommendations. We calculated weighted means for prevalence rates per symptom.

Results

The search identified 2.074 unique papers, of which 32 were included in this review. In total 25 symptoms were identified. The ten most prevalent symptoms were: seizures (37%), cognitive deficits (36%), drowsiness (35%), dysphagia (30%), headache (27%), confusion (27%), aphasia (24%), motor deficits (21%), fatigue (20%) and dyspnea (20%).

Conclusions

Eight out of ten of the most prevalent symptoms in glioma patients are related to the central nervous system and therefore specific for glioma. Our findings emphasize the importance of tailored symptom care for glioma patients and may aid in the development of specific PROMs for glioma patients in different phases of the disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11060-018-03015-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Glioma, Glioblastoma, Symptoms, Adverse events, Toxicity, Patient reported outcomes, PROM

Introduction

Gliomas are the most common primary malignant brain tumors in adults. The annual incidence of malignant glioma in the United States is ~ 5/100,000 with a slight predominance in males [1]. Despite multimodal treatment prognosis remains poor, especially for glioblastoma [2]. Glioma patients often suffer from a wide range of symptoms. These symptoms are often of a neurological nature [3] with a great impact on the patients’ quality of life [4, 5]. Symptom burden in cancer patients may also influence treatment intensity [6]. Improving symptom management in order to maintain quality of life has therefore become a major treatment goal [7].

Symptoms in glioma patients can be caused by the tumor or occur as side effect of treatment. Adequate symptom management for glioma patients relies on knowledge about the prevalence of symptoms in this patient population and efficacy of symptom-aimed treatments [4, 8]. Different papers have reviewed the prevalence or treatment of unique symptoms in glioma patients, such as cognitive deficits [9], seizures [10], and depression [11]. In other papers side effects for specific treatment regimens were reviewed, e.g. toxicity of systemic treatment [12]. However, to our knowledge a review of the symptom burden of the glioma population for the total disease trajectory has not been published.

A thorough overview of symptoms in the total trajectory of glioma patients may also stimulate the development of Patient Reported Outcome Measurements (PROMS) about symptoms for this population. PROMS for assessment of symptoms have been successfully introduced in patient care in the last decade and have been identified as an essential part of symptom management for glioma patients [13–15]. While a few PROMS have been validated to measure symptoms in brain tumor patients (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain/FACT-Br [16], EORTC QLQ-BN20 [17], and MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-Brain/MDASI-BT) [18], only the MDASI-BT is suitable for daily use. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) is one of the most used PROM’s in symptom care worldwide and has been validated in different groups of patients [19]. Use of this tool resulted in significant improvement of patients symptom burden and symptom management delivered in a diversity of health care settings [20, 21]. However, the ESAS is based on most prevalent symptoms in cancer patients in general and does not include symptoms for specific tumor types like glioma. It has been recommended to add additional questions for specific patient groups [19].

The aim of this study is to perform a systematic review of symptom prevalence in patients with a glioma throughout the total disease trajectory, in order to enhance professionals’ awareness of the symptom burden of glioma patients, and to provide a basis for the development of a symptom-directed glioma PROM suitable for use in clinical practice as well as in research.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature review using the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL, searching from January 1st 2000 until December 31, 2017. The search domain included synonyms for the ‘glioma’ population and for ‘symptoms, signs, side effects and adverse events’ (see Supplementary Material I). Papers in English or Dutch language were included if they described the prevalence of symptoms, signs or adverse events in adult glioma patients, present in any stage of the disease. We only included papers with 50 patients or more to avoid bias due to small sample sizes. Papers on HRQoL were included when prevalence of symptoms was reported. Papers were excluded if they:

did not describe original studies

described only severity of symptoms or hematological toxicities.

Two researchers (FYFdV and MIJ) selected papers based on title and abstract. Agreement about the selection of full papers was reached in consensus meetings. All data from the selected studies by researcher one (FYFdV or MIJ) were checked by researcher two (FYFdV or MIJ). We hand-searched included papers for cross-references. Included studies were evaluated according to the STROBE statement (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [22], see Supplementary Material Table II. We registered symptom prevalence for different phases of disease: at diagnosis; during treatment and follow-up; and in the end-of-life stage. Prevalence of symptoms by glioma grade was also described, when available. For symptoms that were defined differently in the included studies (e.g. cognitive disorders) the most deployed definition was used in this review, but all original descriptions were registered.

For all studies both the characteristics of the study population and the prevalence rates of symptoms were registered for the total group and for subgroups, if available. In one study the first author was contacted to provide additional information about prevalence rates of symptoms not explicitly mentioned in the paper [23].

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) [24].

Data analysis

We registered the prevalence rates of symptoms per study. Weighted means were calculated per symptom for the total disease trajectory and per phase of disease. Only studies describing the specific symptom were included in this analysis. For symptoms registered separately such as ‘nausea’ and ‘vomiting’ instead of ‘nausea/vomiting’ the highest rates were used for calculating weighted means to achieve prevalence rates best representing the total group. If symptom prevalence was only registered for different phases such as ‘presenting symptoms’ and ‘phase of follow-up’, with no registration of prevalence for the total disease trajectory, we also used the highest reported rates to calculate weighted means.

Results

Published papers

The search strategy identified 2074 unique papers of which 32 papers were included for this review with a total of 7656 patients included (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection of papers

Study and patient characteristics

Study characteristics are presented in Table 1. Seven papers used a prospective design [25–31], one of which was a randomized controlled trial [28]. Data were usually collected by a search in the patients’ medical records. In seven studies describing symptoms in the treatment phase, symptoms were registered according to the CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events), varying from registering all grades, to only registering grade 3 and 4 [25, 28, 31–35]. In four studies data were collected by means of validated PROMs including symptoms: the EORTC module for brain cancer patients (EORTC QLQ-BN20) [27], the ESAS-r (ESAS revised) [30], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [26, 36], the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) [36], and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [36]. Telephone interviews with patients were performed in the study of Sizoo, including 58 patients, in addition to data that were obtained from the medical records [37]. The study of Russo, including 527 patients, used face to face interviews [38]. Questionnaires completed by proxies and physicians after the patient died were conducted in the study of Koekkoek, including 178 patients [23].

Table 1.

Study specifics

| Study | n | Goal | Treatment | Time point | Retrospective/Prospective | Datacollection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bae, 2013 | 300 | Investigate signs and symptoms during temozolomide | Chemotherapy | Treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records on CTCAE version 3.0, grade 1–4 | [32] |

| Brada, 2001 | 138 | Investigate efficacy and toxicity of temozolomide in glioblastoma patients | Chemotherapy | Treatment | P (phase II trial) | Medical records on CTCAE, grade 1–4 | [25] |

| Cao, 2012 | 112 | Investigate safety and efficacy during chemoradiation vs. radiation in elderly patients | Chemoradiation, radiation (hyofractioned) chemotherapy | Diagnosis, treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records on CTCAE version 3.0, grade 1–5 | [33] |

| Chen, 2017 | 712 | Investigate mutant IDH1 and seizures in glioma patients | Diagnosis | R (cross-sectional) | Medical records | [39] | |

| Diamond, 2017 | 50 | Investigate prognostic awareness, communication and cognitive function in patients with glioma | All | P | HADS (score 9 or higher) | [26] | |

| Ening, 2015 | 233 | Investigate risk factors for glioma therapy complications at diagnosis | Surgery, chemotherapy, chemoradiation, radiation | Treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records | [53] |

| Iuchi, 2014 | 121 | Investigate incidence epilepsy in glioma patients | Surgery, chemoradiation | Diagnosis, FU** | R (cohort) | Medical records | [40] |

| Jakola, 2012 | 55 | Investigate the association between location, survival, and long-term health in patients with low grade glioma | Surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy | FU | P | EORTC-BN20 (Likert score 3 and 4) | [27] |

| Kerkhof, 2013 | 291 | Investigate seizure control of valproic acid | Anti-epileptics | Diagnosis, All (diagnosis and FU) | R (cohort) | Medical records* | [41] |

| Kim, 2013 | 406 | Investigate incidence epilepsy in glioma patients | Surgery, chemoradation, chemotherapy, radiation | Diagnosis, All (diagnosis and FU) | R (cohort) | Medical records* | [42] |

| Kocher, 2005 | 81 | Investigate signs and symptoms during chemoradiation | Chemoradiation | Treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records* | [54] |

| Koekkoek, 2014 | 178 | Investigate signs and symptoms at end-of life | Palliative care | End-of-life | R (cross-sectional) | Developed symptom questionnaire, completed by physician’s and proxies after patient died | [23] |

| Liang, 2016 | 184 | Investigate indidence of epilepsy in supratentorial glioblastoma patients | Surgery, chemotherapy, (intra-tumor) radiotherapy | Diagnosis, FU | R (cohort) | Medical records | [43] |

| Malström, 2012 | 291 | Investigate safety and efficacy during chemotherapy vs. radiation in elderly patients | Chemotherapy, (hypofractioned) radiation | Treatment | P (RCT) | WHO grading system for AE grade 2–5; N/V by National Cancer Institute CTC version 2.0 | [28] |

| Mamo, 2017 | 64 | Investigate adverse events in glioblastoma patients with bevacizumab | Targeted therapy | Treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records, CTCAE grade 3 and 4 | [34] |

| Piribauer, 2003 | 103 | Investigate feasibility and toxicity during lomustine therapy in eldery patients | Chemotherapy | Diagnosis | R (cohort) | Medical records | [44] |

| Posti, 2015 | 142 | Investigate presenting symptoms at diagnosis | Diagnosis | R (cohort) | Medical records from emergency rooms, intensive care unit, and different inpatient wards; hospital and imaging referrals, disch letters | [45] | |

| Rasmussen, 2017 | 1930 | Investigate symptoms in glioma patients | Surgery | Diagnosis | P (cohort) | Danish Neuro-oncology Registry | [29] |

| Russo, 2017 | 527 | Investigate prevalence of headache in glioma patients | Diagnosis | R (cross-sectional) | Face to face interviews | [38] | |

| Sagberg, 2013 | 164 | Investigate responsiveness of EQ-5D in glioma patients with surgery | Surgery | Diagnosis | R (cross-sectional) | Medical records | [46] |

| Saito, 2014 | 76 | Investigate signs and symptoms during chemoradiation in eldery patients | Chemoradiation, radiation, chemotherapy | Treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records-CTCAE grade 3 and 4 | [35] |

| Salmaggi, 2005 | 134 | Set up a registry for glioblastoma patients in Lombardia, Italy | Surgery radiation chemotherapy | Diagnosis | R (cohort) | Medical records-reports on signs/symptoms and seizures | [47] |

| Sanai, 2012 | 119 | Investigate surgery associated complications | Surgery | Diagnosis, treatment | R (cohort) | Medical records and telephone interviews | [48] |

| Seekatz, 2017 | 54 | Screening for symptom burden in glioma patients | All | P(cohort) | Revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) Score 4–10 | [30] | |

| Sizoo, 2010 | 58 | Investigate signs and symptoms at end-of life | Palliative care | End-of-life | R (cohort) | Medical records& charts of nurse specialist on telephone interviews about symptoms based on self-developed checklist | [37] |

| Stupp, 2002 | 64 | Investigate toxicity of chemoradation | Chemoradiation plus adjuvant chemotharapy | Treatment | P (cohort) | Medical records - CTCAE version 2.0, grade 3–4 | [31] |

| Thrier, 2015 | 57 | Investigate signs and symptoms at end-of life | Palliative care | End-of-life | R (cohort) | Daily reporting of signs and symptoms by standardized protocol | [55] |

| Valko, 2014 | 65 | Investigate incidence fatigue after surgery in glioma patients | Surgery | Treatment | P (cohort) | Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS score 4–9), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS score 10 or higher), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS score 10 or higher) | [36] |

| Van Breemen, 2009 | 108 | Investigate seizure control of anti-epileptics | Anti-epileptics | Diagnosis, All (diagnosis and FU) | R (cohort) | Medical records | [49] |

| Woo, 2014 | 198 | Investigate risk factors for seizures in glioma patients | Surgery, chemoradiation, chemotherapy | Diagnosis, FU | R (cohort) | Medical records | [50] |

| You, 2012 | 508 | Investigate incidence epilepsy and postoperative seizure control | Surgery | Diagnosis, FU | R (cohort) | Medical records* | [51] |

| Yuile, 2006 | 133 | Investigate signs and symptoms during radiotherapy | Radiation | Diagnosis | R (cohort) | Medical records | [52] |

*Not explicitly mentioned, **FU follow up

Seventeen papers described symptoms in glioma patients at time of diagnosis [29, 33, 38–52]. In sixteen papers symptoms are described in the phase of treatment or follow-up [25, 27, 28, 31–36, 40, 43, 48, 50, 51, 53, 54]. After initial surgery, patients were treated with chemoradiation, chemotherapy or targeted therapy, or radiation. In eleven of the twelve papers recording symptoms and toxicities during or after systemic treatment, chemotherapy or chemoradiation with temozolomide was part of the treatment [25, 28, 31–35, 40, 43, 53, 54]. One paper that registered symptoms during follow-up did not describe which chemotherapy was administered to patients [27]. Three papers described symptoms in the first 10 weeks after surgery: 1–6 weeks postoperatively [48], within 30 days postoperatively [53] and within 10 weeks postoperatively [36]. Symptoms in the end-of-life phase were described in three papers, in which the definition of end of life varied from the moment no next lines of established tumor treatment were possible [37] to 3 months and 1 week before death (retrospectively described by proxies and physicians after the patients’ death) [23], and the last 10 days of life [55]. Two papers registered symptoms in all phases of the disease [26, 30]. Of all papers, nine recorded three or less predefined symptoms: seizures only in seven studies [39–41, 43, 49–51]; and seizures, cognitive deficits and headache in two studies [29, 38].

Patient characteristics are described in Table 2. Most patients were male (60%) and suffered from glioblastoma WHO grade IV.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Study | N | M/F | Age (year) Mean range |

KPS (%) (Mean) |

KPS ≥ 70% |

Glioma WHO II (n) | Glioma WHO III (n) | Glioma WHO IV (n) | Median OS (months) range | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bae, 2013 | 300 | 187/113 | 49 17–84 |

87 | 20 | 67 | 213 | [32] | ||

| Brada, 2001 | 138 | 85/53 | 54 24–77 |

100% (KPS > 70%) |

138 | [25] | ||||

| Cao, 2012 | 112 | 73/39 | 70 60–86 |

80 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 7 | [33] | |

| Chen, 2017 | 712 | 400/312 | 55 | 77 | 128 | 507 | [39] | |||

| Diamond, 2017 | 50 | 34/16 | 50 18–77 |

16 | 34 | [26] | ||||

| Ening, 2015 | 233 | 117/116 | 58 | 79% (KPS > 70%) |

0 | 0 | 233 | 9.5 0–72 |

[53] | |

| Iuchi, 2014 | 121 | 74/47 | 58 | 19 | 21 | 81 | [40] | |||

| Jakola, 2012 | 55 | 30/25 | 41 | 91% (KPS ≥ 80%) |

55 | [27] | ||||

| Kerkhof, 2013 | 291 | 169/122 | 60 24–85 |

0 | 0 | 291 | 13 | [41] | ||

| Kim, 2013 | 406 | 244/162 | 51 18–86 |

75% (KPS > 70%) |

0 | 124 | 282 | [42] | ||

| Kocher, 2005 | 81 | 53/28 | 52 15–72 |

83 | 12 | 22 | 47 | [54] | ||

| Koekkoek, 2014 | 178 | 125/53 | 60 | 20%3 m 2%1 w |

0 | 19 | 159 | 12.4 gr III 10.6–14.1 10.6 gr IV 9.2–12.1 |

[23] | |

| Liang, 2016 | 184 | 100/84 | 49 20–69 |

47 e 56 we |

184 | [43] | ||||

| Malström, 2012 | 291 | 173/118 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 291 | 8.3 chemo 6.0 rt 7.5 hypofr rt |

[28] | ||

| Mamo, 2017 | 64 | 40/24 | 54 26–83 |

88% | 64 | [34] | ||||

| Piribauer, 2003 | 103 | 65/38 | > 55 55–83 |

79 | 0 | 0 | 103 | 17.5 py 8.6 pe |

[44] | |

| Posti, 2015 | 142 | 76/66 | 60 | 29 | 31 | 82 | [45] | |||

| Rasmussen, 2017 | 1930 | 1158/772 | 18–79 | 247 | 279 | 1364 | [29] | |||

| Russo, 2017 | 527 | 314/213 | 53 | 139 | 87 | 268 | [38] | |||

| Sagberg, 2013 | 164 | 56 | 73 | 43 | 121 | [46] | ||||

| Saito, 2014 | 76 | 50/26 | 47 py 71 pe |

82% py 70% pe |

0 | 0 | 76 | 15.2 12.9–18.5 21.6 py 15.6 pe |

[35] | |

| Salmaggi, 2005 | 134 | 82/52 | 61 | 85% | 0 | 0 | 134 | [47] | ||

| Sanai, 2012 | 119 | 45 18–81 |

75 | 34 | 23 | 62 | [48] | |||

| Seekatz, 2017 | 54 | 60 24–79 |

54 | [30] | ||||||

| Sizoo, 2010 | 58 | 39/19 | 52 18–81 |

0 | 15 | 41 | 21 gr III 11–86 12 gr IV 0.5–71 |

[37] | ||

| Stupp, 2002 | 64 | 39/25 | 52 24–70 |

64% (KPS > 80%) |

64 | 23 | [31] | |||

| Thrier, 2015 | 57 | 39/18 | 59 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 12 | [55] | |

| Valko, 2014 | 65 | 44/21 | 57 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 65 | [36] | ||

| Van Breemen, 2009 | 108 | 54/54 | 40 53 |

33 | 75 | > 8 years HGG 19 LGG |

[49] | |||

| Woo, 2014 | 198 | 122/76 | 55 18–88 |

81% | 125 | 73 | 9.0 11.0 gr III 8.0 gr IV |

[50] | ||

| You, 2012 | 508 | 306/202 | 38 16–72 |

88% (KPS ≥ 80%) |

508 | 0 | 0 | 32.9 12–58.3 |

[51] | |

| Yuile, 2006 | 133 | 84/49 | 59 22–86 |

0 | 0 | 133 | 10 0.1–51.8 |

[52] |

Chemo chemotherapy, e with epilepsy, gr III grade III glioma, gr IV grade IV glioma, HGG high grade glioma, hypofr hypofractioned, LGG low grade glioma, OS overal survival rate, pe patients of 65 years or older, py patients younger than 65 years, rt radiotherapy, we without epilepsy, 3 m 3 months before death, 1 w 1 week before death

Symptom prevalence throughout the disease course

A total of 25 symptoms were identified: alopecia, anorexia, aphasia, anxiety/depression, cognitive deficits, constipation, confusion, diarrhea, dizziness, drowsiness, dyspepsia, dysphagia, dyspnea, fatigue, gait disturbance, headache, motor deficits, nausea/vomiting, pain, right-left-confusion, seizures, sensory deficits, skin problems, urinary incontinence, and visual deficits. The symptoms nausea/vomiting and anxiety/depression were commonly registered as paired symptoms. In this review we used this paired definition for these symptoms, but if prevalence rates were only described for the symptoms separately in studies, we registered both of these rates.

Most prevalent symptoms

The prevalence of symptoms for the total disease trajectory is recorded in Supplementary Material Table III. Table 3 shows weighted means of symptom prevalence. The ten most prevalent symptoms for the total disease trajectory are: seizures (37%), cognitive deficits (36%), drowsiness (35%), dysphagia (30%), headache (27%), confusion (27%), aphasia (24%), motor deficits (21%), fatigue (20%) and dyspnea (20%).

Table 3.

Weighted means (in %) of symptom prevalence

| Seizures (1) | Cognitive deficits (2) | Drowsiness (3) | Dysphagia | Headache | Confusion(4) | Aphasia (5) | Motor deficits (6) | Fatigue (7) | Dyspnea (8) | Nausea/vomiting (9) | Urinary incontinence (10) | Pain (11) | Anxiety/depression (12) | Anorexia (13) | Sensory deficits | Dizziness (14) | Visual deficits (15) | Gait disturbance | Alopecia | Skin problems (16) | Right left confusion | Constipation | Diarrhea | Dyspepsia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total disease trajectory | 36.5 | 35.9 | 35.3 | 30.0 | 27.2 | 26.5 | 23.7 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 19.6 | 19.0 | 16.5 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.0 | 12.1 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 6.7 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Diagnostic phase |

34.7 | 36.0 | 15.0 | 4.0 | 30.5 | 20.1 | 21.6 | 6.5 | 13.3 | 23.5 | 6.7 | 10.0 | |||||||||||||

| Treatment/FU phase | 36.7 | 18.3 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 13.7 | 23.2 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 12.7 | 5.9 | 12.8 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 2.0 | |||||

| End-of-Life phase | 44.6 | 44.3 | 81.3 | 41.9 | 37.3 | 40.3 | 48.0 | 44.2 | 49.9 | 17.7 | 19.2 | 37.0 | 15.2 | 15.8 | 2.0 | 23.0 | 22.0 | 9.0 |

The symptoms presented here as most prevalent are not necessarily the symptoms reported in most studies. Confusion and dyspnea for example are reported in only three studies, including two studies in the end of life phase [23, 37]. When excluding studies which registered only unique symptoms (n = 9), the most frequently reported symptoms in the 23 remaining studies are: seizures (16 studies), headache (14 studies), fatigue (13 studies), nausea/vomiting (12 studies), and motor deficits (10 studies).

Symptom prevalence per phase

The prevalence of symptoms per phase of disease is also recorded in Supplementary Material Table III, and weighted means in Table 3. The five most prevalent symptoms in the diagnostic phase are cognitive deficits (36%), seizures (35%), headache (31%), dizziness (24%), and motor deficits (22%). In the treatment and follow-up phase the most prevalent symptoms are seizures (37%), nausea/vomiting (23%), cognitive deficits (18%), fatigue (14%), visual deficits (13%) and anorexia (13%). Nausea/vomiting is more prevalent during systemic treatment than postoperatively. Other symptoms in the treatment phase are less common, with weighted prevalence means of 10% or less. In the end-of-life phase, drowsiness (81%), fatigue (50%), aphasia (48%), seizures (45%), cognitive deficits (44%), and motor deficits (44%) are most prevalent.

Most of the 25 symptoms are described in all three phases of disease and treatment. Alopecia, anorexia, dyspepsia and diarrhea are only reported during systemic treatment or radiation.

Symptom prevalence by tumor grade

In some studies symptom prevalence was described by tumor grade (see Table 4). Seizures show a high prevalence in all grades. Cognitive disorders are more prevalent in grade III and IV tumors, but their prevalence in grade II tumors is still considerable. The prevalence of headache is less different between tumor grades (22–38%).

Table 4.

Symptoms by grade of glioma

| Study | Histological grade glioma | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO II | WHO III | WHO IV | |

| Seizures | |||

| Iuchi | 47% pr 74% t |

29% pr 67% t |

20% pr 57% t |

| Kim | 34–37% | 29% | |

| Posti | 83% | 65% | 38% |

| Van Breemen | 70% pr 76% t |

52% pr 80% t |

|

| Rasmussen | 58% pr | 45% pr | 24% |

| Cognitive disorders | |||

| Posti | 21% | 45% | 74% |

| Rasmussen | 24% | 41% | 48% |

| Headache | |||

| Rasmussen | 22% | 30% | 38% |

Discussion

The most prevalent symptoms in patients with glioma throughout the total disease trajectory in this review are seizures, cognitive deficits, drowsiness, dysphagia, headache, confusion, aphasia, motor deficits, fatigue, and dyspnea. The exact prevalence of symptoms varies strongly between different phases of the disease. The findings of the review emphasize the unique nature of glioma patients’ symptom burden, which is closer related to the symptoms of a brain disease than to the symptom burden of cancer patients in general [56, 57].

Seizures are highly prevalent in glioma patients. Seizures were assessed frequently and were registered exclusively in seven papers [39–41, 43, 49–51]. To avoid bias of increased attention for this symptom in these papers, we also calculated weighted mean prevalence of seizures in papers not exclusively registering the symptom. The prevalence of seizures then decreased to 28%, which is still high. The symptoms confusion, dysphagia and dyspnea show especially high prevalence in the end-of-life phase, but are reported less frequently during the phases of diagnosis and treatment and follow-up.

This review shows the unique nature of glioma patients’ symptom burden. Symptoms seem to be largely caused by the tumor itself and to a much lesser degree by treatment. This is confirmed by results of other studies. A review of Sizoo [58] about symptoms in the end-of life-phase for glioma patients showed a comparable or even higher prevalence of neurological symptoms such as seizures, cognitive decline and progressive neurological deficits compared to our study. Except for fatigue, the more generally acknowledged end-of-life symptoms in cancer such as anorexia and weight loss occur less often in glioma patients than in other groups of palliative care patients. Ostgathe concluded that the prevalence of confusion in the end-of-life phase was significantly higher in patients with primary brain tumors than in patients with brain metastases or a general palliative care population [59]. In a systematic review of Wei [12] reporting toxicities in patients with high grade glioma treated with chemo-radiation, gastrointestinal toxicities and fatigue remained under 7%.

Eight of the ten most prevalent symptoms in this review are included in at least two of the three existing PROMS measuring symptoms in glioma patients with the same or different wordings (EORTC QLQ-BN20, FACT-Br, MDASI-BT). Confusion and dysphagia are not included in one of them. This could be because of their prominence in the end-of-life phase: other PROMS did not include all phases of the total disease trajectory in development of the PROM. Dyspnea and fatigue are reported in the core versions of the three PROMS (dyspnea not on the FACT-Br). ‘Visual deficits’ is included in all three mentioned PROMS, but showed a prevalence of only 12% in this review. No other neurological symptoms are included in at least two of those three PROMS.

Limitations

In this review only seven of the 32 studies we included used prospective data. In only four studies patients were asked about symptoms themselves by a validated PROM, only one of which was specifically developed for patients with brain tumors (QLQ-BN-20). Most studies used collected data in medical records only, which possibly resulted in symptoms being missed because patients were not asked about them or the symptoms were not documented in the records. Patients are more likely to reveal their real symptom burden with the use of a questionnaire than through spontaneous self-report [60]. This phenomenon is likely to have led to underreporting of symptoms. The poor representation of brain tumor PROMS in this review is likely to be caused by difficulties in using these questionnaires in this patient population in general: questionnaires are quickly experienced as being too long or difficult due to cognitive or functional impairments, which can result in decreased compliance and use [13]. A glioma PROM that is perceived as brief and easy could increase its use. Secondly, we had to exclude some studies who did use a specific PROM but only reported scale scores, and not prevalence. Another limitation of this review is the use of different definitions for symptoms and pairing of symptoms in the included studies, which may have influenced our results.

Strengths

This is the first published systematic review of symptoms in glioma patients throughout the whole continuum of the disease trajectory, as well as per phase and (where possible) by grade of glioma.

Conclusion and recommendations

Eight out of ten of the most prevalent symptoms in glioma patients in this review are neurological in nature. Because of this unique symptom burden differing from symptoms in cancer patients in general and its effect on quality of life and treatment, the results of our review stress a need for tailored symptom care in glioma patients. This care will be improved by use of a specific glioma PROM focusing on glioma specific symptoms throughout all disease stages and suitable for daily use.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Funding was provided by Cancer Center University Medical Center Utrecht.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, et al. Neuro-oncology System tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009–2013. Neuro-oncology. 2016;18:175. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukand JA, Blackinton DD, Crincoli MG, Lee JJ, Santos BB. Incidence of neurologic deficits and rehabilitation of patients with brain tumors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(5):346–350. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boele FW, Klein M, Reijneveld JC, Verdonck-De IM, Leeuw, Heimans JJ. Symptom management and quality of life in glioma patients. CNS Oncol. 2014;3(1):37–47. doi: 10.2217/cns.13.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Microsoft. Janda S, Steginga D, Langbecker J, Dunn D, Walker, Eakin E. Quality of life among patients with a brain tumor and their carers. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(6):617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koldenhof JJ, et al. Symptoms from treatment with sunitinib or sorafenib: a multicenter explorative cohort study to explore the influence of patient-reported outcomes on therapy decisions. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(9):2371–2380. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minniti G, et al. Health-related quality of life in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated with short-course radiation therapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(2):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walbert T, Chasteen K. Palliative and supportive care for glioma patients. Cancer Treat Res. 2015;163:171–184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-12048-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boone M, Roussel M, Chauffert B, Le Gars D, Godefroy O. Prevalence and profile of cognitive impairment in adult glioma: a sensitivity analysis. J Neuro-oncol. 2016;129(1):123–130. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koekkoek JAF, Kerkhof M, Dirven L, Heimans JJ, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJB. Seizure outcome after radiotherapy and chemotherapy in low-grade glioma patients: a systematic review. Neuro-oncology. 2015;17(11):924934. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooney AG, Carson A, Grant R. Depression in cerebral glioma patients: a systematic review of observational studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;103(1):61–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei W, Chen X, Ma X, Wang D. The efficacy and safety of various dose-dense regimens of temozolomide for recurrent high-grade glioma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Neuro-oncol. 2015;125(2):339–349. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boele FW, et al. Attitudes and preferences toward monitoring symptoms, distress, and quality of life in glioma patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):3011–3022. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bultz BD, Waller A, Cullum J, Jones P, Halland J. Implementing routine screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, for patients with head and neck and neurologic cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(10):1249–1261. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trad W et al. (2015) Screening for psychological distress in adult primary brain tumor patients and caregivers: considerations for cancer care coordination. 5(9):3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Weitzner MD, Meyers CA, Gelke CK, Byrne KS, Cella DF, Levin VA. The functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) scale development of a brain subscale and revalidation of the general version (FACT-G) in patients with primary brain tumors. Cancer. 1995;75(5):11511161. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950301)75:5<1151::AID-CNCR2820750515>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osoba AD, et al. The development and psychometric validation of a brain cancer quality-of-life questionnaire for use in combination with general cancer-specific questionnaires. Qual Life Res. 2017;5((1)):139–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00435979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong TS, et al. Validation of the M. D. Anderson symptom inventory brain tumor module (MDASI-BT) J Neuro-oncol. 2006;80(1):2735. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson La, Jones GW. A review of the reliability and validity of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Current Oncology. 2009;16(1):53–64. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbera L, et al. Does routine symptom screening with ESAS decrease ED visits in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy? Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(10):3025–3032. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2671-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strasser F, et al. The effect of real-time electronic monitoring of patient-reported symptoms and clinical syndromes in outpatient workflow of medical oncologists: E-MOSAIC, a multicenter cluster-randomized phase III study (SAKK 95/06) Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):324–332. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Von Elm E, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koekkoek JaF, et al. Symptoms and medication management in the end of life phase of high-grade glioma patients. J Neuro-oncol. 2014;120(3):589–595. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brada M, et al. Original article multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2017;12(2):259266. doi: 10.1023/a:1008382516636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diamond EL, et al. Neuro-oncology cognitive function in patients with malignant glioma. N Engl J Med. 2018;10(1):15321541. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakola AS, et al. Low grade gliomas in eloquent locations-implications for surgical strategy, survival and long term quality of life. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malmström A, et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(9):916–926. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen B, Steinbjørn R, Laursen RJ, Kosteljanetz M, Schultz H, Mertz B. Epidemiology of glioma: clinical characteristics, symptoms, and predictors of glioma patients grade I–IV in the the Danish Neuro-oncology Registry–. J Neuro-oncol. 2017;135(3):571579. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2607-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seekatz B, et al. Screening for symptom burden and supportive needs of patients with glioblastoma and brain metastases and their caregivers in relation to their use of specialized palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2761–2770. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stupp BR, et al. Promising survival for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme treated with concomitant radiation plus temozolomide followed by adjuvant. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1375–1382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae SH, et al. Toxicity profile of temozolomide in the treatment of 300 malignant glioma patients in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(7):980–984. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.7.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao JQ, Fisher BJ, Bauman GS, Megyesi JF, Watling CJ, Macdonald DR. Hypofractionated radiotherapy with or without concurrent temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma multiforme: a review of ten-year single institutional experience. J Neuro-oncol. 2012;107(2):395–405. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mamo A, et al. Progression pattern and adverse events with bevacizumab in glioblastoma. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(5):468–471. doi: 10.3747/co.23.3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito K, et al. Toxicity and outcome of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma: a retrospective study. Neurol Med Chir. 2014;54(4):272–279. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa2012-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valko PO, Siddique A, Linsenmeier C, Zaugg K, Held U, Hofer S. Prevalence and predictors of fatigue in glioblastoma: a prospective study. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17(2):274–281. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sizoo EM, et al. Symptoms and problems in the end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12(11):1162–1166. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo M, et al. Headache as a presenting symptom of glioma: a cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia. 2017;0(0):1–6. doi: 10.1177/0333102417710020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H, Judkins J, Thomas C, Golfinos JG, Lein P, Chetkovich DM. Mutant IDH1 and seizures in patients with glioma. Neurology. 2017;88(19):1805–1813. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iuchi T, Hasegawa Y, Kawasaki K, Sakaida T. Epilepsy in patients with gliomas: incidence and control of seizures. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerkhof M, et al. Effect of valproic acid on seizure control and on survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-oncology. 2013;15(7):961–967. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YH, et al. Seizures during the management of high-grade gliomas: clinical relevance to disease progression. J Neuro-oncology. 2013;113(1):101–109. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang S, Zhang J, Zhang S, Fu X. Epilepsy in adults with supratentorial glioblastoma: incidence and influence factors and prophylaxis in 184 patients. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piribauer M, et al. Feasibility and toxicity of CCNU therapy in elderly patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14(2):137–143. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Posti JP, et al. Presenting symptoms of glioma in adults. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;131(2):88–93. doi: 10.1111/ane.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sagberg LM, Jakola AS, Solheim O. Quality of life assessed with EQ-5D in patients undergoing glioma surgery: what is the responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference? Qual Life Res. 2014;23(5):1427–1434. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salmaggi a, et al. A multicentre prospective collection of newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients in Lombardia, Italy. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(4):227–234. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0465-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanai N, Martino J, Berger MS. Morbidity profile following aggressive resection of parietal lobe gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(6):1182–1186. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.JNS111228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Breemen MSM, Rijsman RM, Taphoorn MJB, Walchenbach R, Zwinkels H, Vecht CJ. Efficacy of anti-epileptic drugs in patients with gliomas and seizures. J Neurol. 2009;256(9):1519–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woo PYM, et al. Risk factors for seizures and antiepileptic drug-associated adverse effects in high-grade glioma patients: a multicentre, retrospective study in Hong Kong. Surg Pract. 2015;19(1):2–8. doi: 10.1111/1744-1633.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You G, et al. Seizure characteristics and outcomes in 508 resection of low-grade gliomas: a clinicopathological study. Neuro-oncology. 2012;14(2):230–241. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuile P, Dent O, Cook R, Biggs M, Little N. Survival of glioblastoma patients related to presenting symptoms, brain site and treatment variables. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13(7):747–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ening G, Osterheld F, Capper D, Schmieder K, Brenke C. Risk factors for glioblastoma therapy associated complications. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;134:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kocher M, Kunze S, Eich HT, Semrau R, Müller RP. Efficacy and toxicity of postoperative temozolomide radiochemotherapy in malignant glioma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181(3):157–163. doi: 10.1007/s00066-005-1314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thier K, Calabek B, Tinchon A, Grisold W, Oberndorfer S. The last 10 days of patients with glioblastoma: assessment of clinical signs and symptoms as well as treatment. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(10):985–988. doi: 10.1177/1049909115609295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Beuken-van MHJ, Everdingen JM, de Rijke AG, Kessels HC, Schouten M, van Kleef, Patijn J. Quality of life and non-pain symptoms in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teunissen SCCM, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HCJM, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sizoo EM, Pasman HRW, Dirven L, Marosi C. The end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(3):847–857. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ostgathe C et al (2010) Differential palliative care issues in patients with primary and secondary brain tumours. 18(9):1157–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Homsi J, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: Patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(5):444–453. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.