Abstract

The lymphatic drainage of the inner layers (mucosa and submucosa) and the outer layers (muscularispropria and adventitia) of the thoracic esophagus is different. Longitudinal lymphatic vessels and long drainage territory in the submucosa and lamina propria should be the bases for bidirectional drainage and direct drainage to thoracic duct and extramural lymph nodes (LN). The submucosal vessels for direct extramural drainage are usually thick while lymphatic communication between the submucosa and intermuscular area is usually not clearly found, which does not facilitate transversal drainage to paraesophageal LN from submucosa. The right paratracheal lymphatic chain (PLC) is well developed while the left PLC is poorly developed. Direct drainage to the right recurrent laryngeal nerve LN and subcarinal LN from submucosa has been verified. Clinical data show that lymph node metastasis (LNM) is frequently present in the lower neck, upper mediastinum, and perigastric area, even for early-stage thoracic esophageal cancer (EC). The lymph node metastasis rate (LNMR) varies mainly according to the tumor location and depth of tumor invasion. However, there are some crucial LN for extramural relay which have a high LNMR, such as cervical paraesophageal LN, recurrent laryngeal nerve LN, subcarinal LN, LN along the left gastric artery, lesser curvature LN, and paracardial LN. Metastasis of thoracic paraesophageal LN seems to be a sign of more advanced EC. This review gives us a better understanding about the LNM and provides more information for treatments of thoracic EC.

Keywords: esophageal carcinoma, lymphatic, lymph node metastasis, lymphadenectomy, radiotherapy

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is a common upper gastrointestinal tumor with a high incidence in Eastern Asia and Eastern and Southern Africa.1 Despite improvements in diagnosis and treatments of EC, overall 5-year survival rate is still very low (–40%).2,3 Because of the complex lymphatic drainage system, the lymph node metastasis rate (LNMR) of EC is very high,4 even for submucosal EC (about 20%–40%).5,6 Lymph node metastasis (LNM) is an important prognostic factor, especially the number or ratio of involved nodes.7–10

Disposal of all potential involved lymph nodes (LN) is essential for a curative treatment. Esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy or three-field lymphadenectomy (3FL) is the typical strategy for resectable EC. However, the extent of lymph node dissection is still controversial.11 Radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy is a prior choice for unresectable EC. The irradiation field for LN is also controversial until now. Involved-field irradiation and elective nodal irradiation are both available. No matter which method is used, it is a fact that EC has a poor survival and the lymph node recurrence is a main failure.11–14 Though much experience in patterns of LNM for EC has been accumulated in past decades, it is challenging to evaluate the status of LNM and to make a reasonable treatment plan for different patients. The anatomy of the lymphatic drainage of the esophagus was well elucidated mainly by Japanese researchers, which is useful for understanding the LNM. In this review, we first discuss the anatomical lymphatic drainage of the esophagus and then analyze the patterns of LNM, aiming to verify the relationship of the anatomical and clinicopathologic data for the guiding treatment of EC.

Anatomy of lymphatic drainage

Esophagus develops from the dorsal part of the foregut while the respiratory tract from the ventral part.15 As a result, these two systems generally have shared blood and lymphatic vessels. The embryologic origin of the lymphatic system is the hemangioblast, which is also the progenitor cell of vascular system.16 Therefore, the lymphatic system is often accompanied by the artery and vein. It is helpful to study the blood vessels and nerves of the esophagus for identifying the lymphatics. Although the anatomy of the individual lymphatic drainage system of the esophagus is quite variable, even at different ages17 or for different diseases,18 there are some universal characteristics of the intramural and extramural configurations.

Normal intramural configurations

The esophageal wall is composed of four layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia.19 The morphological studies of the lymphatics can be examined by a series of techniques, such as sliver staining or D2-40 immunohistochemical staining, transmission electronic microscopy, scanning electronic microscopy, and so on.20–23 Many anatomical lymphatic maps of the esophagus with some differences have been illustrated in past decades.19,20,24–26

Epithelium and its basement lamina

The innermost layer is multi-layered squamous epithelium without keratinization and it folds along papillae.15,20,21,23 The basement lamina is approximately 50–80 µm and discontinuous. Scanning electron microscopy shows numerous foramina of diameter of 3–5 µm in this layer. Lymphocytes and Langerhans cells are richly distributed in the basal lamina and they tend to appear near the papillae.23

Lamina propria

The lymphatic vessels are thought to be not obvious because of low LNMR when tumor invades this layer. It has been proved that lymphatic vessels are densely arranged in the lamina propria, and most of them run longitudinally while limited circumferentially.20,21,23,27 There are no lymphatic vessels connected to intermuscular and extramural lymphatic vessels directly, which may be an explanation for low LNMR. The mucosal vessel density has a great interindividual variation.20,21,27

The foramina on the basal lamina may be the communicating route of immune cells between the epithelium and the lamina propria.23 Valves of lymphatic vessels are not detected in the inner layer of the lamina propria while they are detected in the outer layer.23,28

Muscularis mucosae

The muscularis mucosae of the esophagus was well described by Kaoruko Nagai et al.22 The lymphatic vessels obliquely or longitudinally cross the muscularis mucosae. In the cervical part of the esophagus, the muscularis mucosa is poorly developed. As a result, the muscularis mucosa is consistently connected with submucosa. It is a continuous sheet of longitudinally arranged bundles of smooth muscle cells in the thoracic part while it is a complicated network formed by smooth muscle cells with various directions in the abdominal part.

Submucosa

The lymphatic vessels in this layer are generally located in the outer margin.20,27,29 Although they are not obviously found to be connected to the vessels from the lamina propria and the muscularis mucosae, they should be the collecting vessels on the way to extramural lymphatics. Unlike the dense lymphatic vessels in lamina propria, they are much fewer even around the glandular tissues. They mainly run longitudinally along the long axis of the esophagus or occasionally circumferentially along the outer margin.20,29

There are many lymphatic drainage pathways between submucosa and extramural lymphatic system. First, submucosal plexus can join to regional lymph node without the relay of intermuscular lymphatic plexus. It was verified that submucosal lymphatic flow repeatedly drain into the right recurrent laryngeal nerve node (recR)30 and occasionally to the subcarinal node.31 However, there is no verified direct communication between submucosa and paraesophageal node yet. Second, it can join to thoracic duct (TD) directly with thick collecting vessels by passing through a complete gap.31 Third, it may join to intermuscular lymphatic plexus which is connected with the extramural lymphatics. However, this pathway is not identified histologically even in sequential sections.20,31

For a direct drainage to TD, the submucosal plexus can extend longitudinally over 20 mm oral and anal from the level of the complete gap, and it is well developed near the complete gap.31 Though the submucosal territory of direct drainage to regional lymph node is not investigated, it may be also long due to its thick collecting vessels.

Muscularis propria

The muscularis propria is formed of an inner circular muscle layer and an outer longitudinal muscle layer. The intermuscular lymphatic plexus is clearly visible, and it runs circumferentially in thoracic esophagus.20,31 Its afferent is usually thin and connective vessels from submucosa could not be identified even in sequential sections. It can communicate with lymphatics in the adventitia,32 extramural lymph node,31,32 or TD directly.31,33

Adventitia

The adventitia, also called fasciae, forms a loose connective tissue on the surface of the esophagus in all its length.34 A thick vascular fascia contain lymphatic vessels was repeatedly discovered between the aorta and the left aspect of the esophagus, which is called the mesoesophagus.35 A belt-like connective tissue that contained the afferent vessels from the esophagus or trachea was also found.30 However, the specific anatomy of the lymphatic drainage in these fascias is not clearly investigated, which may be a critical aspect for understanding the lymphatic drainage of the esophagus.

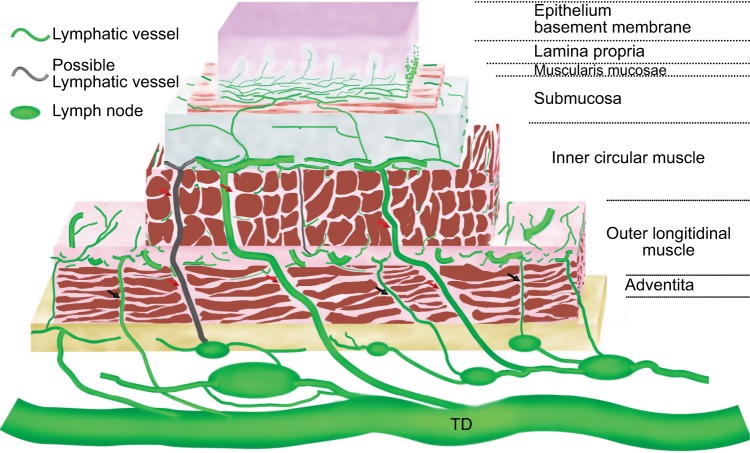

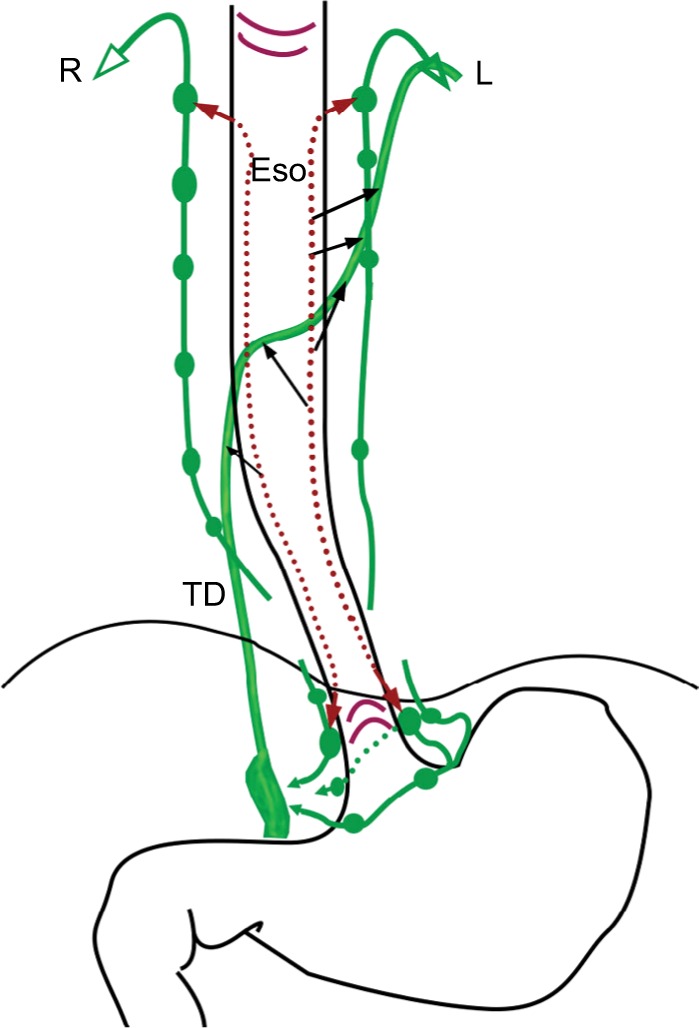

In brief summary, the schema of the intramural lymphatic drainage of the esophagus can be illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic lymphatic drainage of the esophagus.

Notes: Vessels exist in all layers except epithelium and its basement membrane. They run mainly longitudinally in the lamina propria and the submucosa and circumferentially in the intermuscular space. Vessels in lamina propria and muscularis mucosae connect to submucosa. Vessels in submucosa are generally located in the outer margin of this layer. They connect to TD, regional lymph node, and possibly to intermuscular lymphatic plexus and paraesophageal node. The direct lymphatic drainage to TD and regional lymph node pass through a complete gap (red arrows). The intermuscular lymphatic plexus connects to TD, regional lymph node, and paraesophageal node through an incomplete gap (black arrows). Vessels in adventitia connect to TD and regional lymph node.

Abbreviation: TD, thoracic duct.

Normal extramural configurations

There are two routes: direct drainage to TD and lymphatic drainage with nodal relay.

Direct drainage to TD

TD generally receives the lymphatic fluid of the entire body except the right hemithorax, right head and neck, and right arm. It commonly terminates at or near the left venous angle.36 Most of its intrathoracic portion travels upward accompanying with the esophagus and the descending aorta. The position of the direct drainage territory appears to be restricted to the right and/or dorsal quadrants of the esophagus at a specific level,31 which may depend on the topographical relationship between the TD and the esophagus. The ratio of direct drainage to TD is about 43.3% and the connective vessels are located mainly at the level of the first to third and sixth to eighth thoracic vertebrae.32

Lymphatic drainage with nodal relay

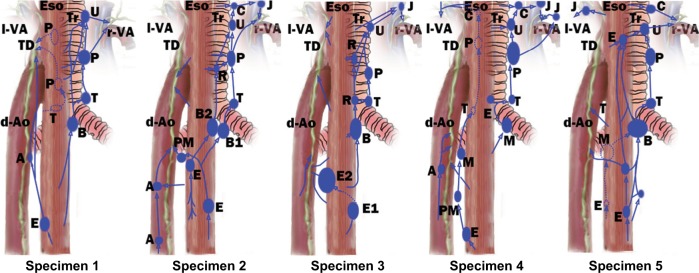

The thoracic ascending extramural lymphatic drainage of the esophagus was elucidated by Saito et al.37 Their results can be summarized in Figure 2. Lymphatic drainage with nodal relay is likely to originate at the intermuscular lymphatic plexus. However, it can also originate at submucosa for specific nodes.30,31 The paratracheal lymphatic chain (PLC) is usually well developed on the right while poorly developed on the left.30,33,37,38 The left esophageal wall mainly drains to TD with or without nodal relay while limited to the left PLC. The right esophageal wall mainly drains to the right PLC with multi-stationed. Communication of left and right lymphatic drainage is observed in the middle and lower thoracic esophagus.

Figure 2.

Schematic representations of extramural lymphatic drainage in five esophagus specimens based on the result of Saito et al.37

Notes: (A) Thoracic paraaortic node; (B) bifurcational node; (C) cervical paratracheal node; (E) paraesophageal node; (J) deep cervical node; (M) main bronchus node; (P) thoracic paratracheal node; (PM) posterior mediastinal node; (R) retrotracheal node; (U), uppermost thoracic paratracheal node.

Abbreviations: d-Ao, descending aorta; Eso, esophagus; TD, thoracic duct; Tr, trachea; l-VA, left venous angle; r-VA, right venous angle.

Cervical paraesophageal LN and supraclavicular LN are usually the upmost nodes in the neck for thoracic esophagus. They drain lymphatics of the cervical esophagus and part of the upper thoracic esophagus. They sometimes receive lymphatics from lower LN. The efferent of cervical para-esophageal LN can join to supraclavicular LN or venous angles directly. Due to the poorly developed left PLC and the route of direct drainage to TD, ascending lymphatics to supraclavicular LN are fewer on the left than on the right. The efferent of supraclavicular LN joins to venous angles. The left supraclavicular LN also has communication with the terminal tributaries of the TD.38,39

The left recurrent laryngeal nerve node (recL) is consistently equal to the left paratracheal LN. The recR is located very close or mostly continuous to the superior portion of the right paratracheal chain.30,38 The recL receives lymphatics from lower levels of left PLC in two specimens, while the recR can receive lymphatics from all lower levels of right PLC in all specimens (Figure 2). The recR was also verified to receive lymphatics from submucosal plexus directly. The efferent of recL commonly connects to TD directly and occasionally connects to cervical LN, while the efferent of recR connects to the venous angle or cervical LN. The collateral lymphatic vessels of recR were also found because of the close topographical relationship between the afferent and efferent.30 The right paratracheal LN receives lymphatics mainly from the lower and middle thoracic esophagus while occasionally from the upper thoracic esophagus. Its efferent connects to recR, cervical LN, or venous angle. Main bronchus LN mainly drains lymphatic drainage from lung and occasionally from the lower and middle esophagus. Its efferent connects to TD or PLC. Subcarinal LN relatively consistently receives ascending lymphatic drainage from the lower and middle thoracic esophagus and frequently connects to PLC or TD directly.31,33,37,38 The afferent of the middle and lower thoracic paraesophageal LN is likely to originate from intermuscular lymphatic plexus, and its efferent connects to TD, subcarinal LN, main bronchus LN, or PLC. Posterior mediastinal LN collects mainly lymphatic drainage of middle and lower thoracic esophagus on the left and terminates at TD. Ligamentumarteriosum LN drains lymphatic drainage of the left upper pulmonary lobe16,40 and routinely connects to the left phrenic LN which belong to anterior mediastinal LN.38

There is no sufficient investigation to elucidate the descending lymphatic drainage system. The efferent of the proximal and distal ends of the submucosal lymphatic plexus is important for understanding the extramural lymphatic drainage. However, only the recR is well investigated and confirmed to be connected directly from the submucosal lymphatic plexus.30 The lymphatic drainage of the lower esophagus and the gastric cardia is different. Mediastinal lymph flow from the gastric cardia is unusual,41 which may be observed when partial or total blockade at the cardiac portion of the stomach.42 Though the submucosa is continuous from lower esophagus to gastric cardia, vasculature was sparsely found in the submucosa of the esophagogastric junction.43 Therefore, the esophagogastric junction should be also an essential watershed of lymphatic drainage. In addition, the pulmonary ligament lymphatic plexus can drain lymphatics from lower esophagus and communicate with celiac lymphatics.16

Direction of lymphatic drainage

The lymph flow of the thoracic esophagus can both run upward to the neck and downward to the celiac area.44,45 There is no adequate investigation to illuminate the bidirectional lymph flow. As we discussed above, lymphatic vessels in the lamina propria and submucosa run longitudinally with long extended territory, which should be the main anatomical bases. However, it is still not sufficient to explain the bidirectional lymph flow because lymph flow in a normal vessel is always seemed to be unidirectional, especially for vessels with valves. Valves of lymphatic vessels are detected in the outer layer of the lamina propria,23,28 while not detected in the submucosa yet. The retrograde lymphatic spread of cancer cells occurred in the lamina propria for valve-equipped lymphatic vessels.28 This phenomenon can be depicted by the change of the fluid pressures around the valves.46 Many reasons have an important impact on the fluid pressure, such as lymphatic obstruction, swallowing, esophageal peristalsis, and so on. The blockage of intramural lymph vessels has very important roles upon the esophageal lymph flow.42,45 The collateral branches of TD with insufficient valves may be another reason for bidirectional lymph flow.36,47 The direction of lymphatic drainage of the esophagus is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schema of direction of esophageal lymphatic drainage.

Notes: The submucosal lymphatic drainage is bidirectional while extramural lymphatic drainage should be unidirectional. Black arrows indicate direct drainage to TD from submucosa.

Abbreviations: ESO, esophagus; L left; R right; TD, thoracic duct.

Clinical patterns of LNM for TEC

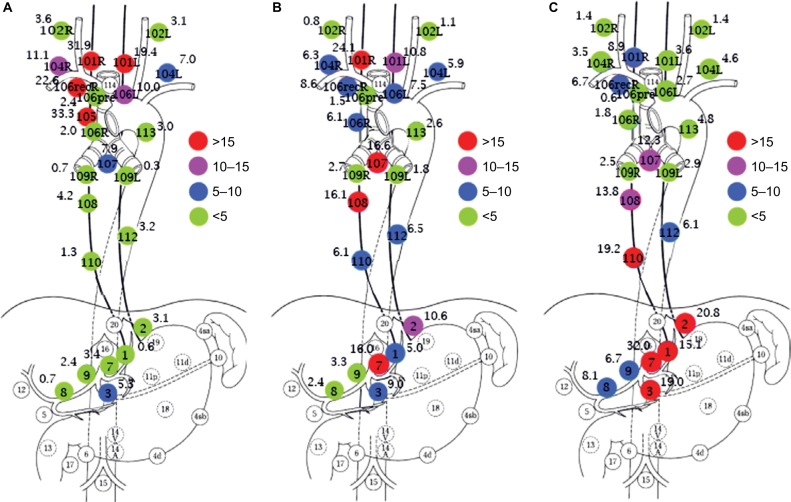

We reviewed studies meeting the following requirements from PubMed up to 31 November 2017: I. Esophagectomy with 3FL was adopted for all patients; II. Lymph node stations were based on the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer of 11th edition.48 Left and right of each station should be summed up separately; III. Different locations of thoracic esophageal cancer (TEC) should be summed up separately; IV. Paper of review or meta-analysis was excluded. V. All papers should be full text online versions. The terms of literature search: (“lymph”) AND (“esophageal” OR “esophagus” OR “oesophagus”) AND (“cancer” OR “carcinoma” OR “tumor” OR “neoplasm”). As a result, five studies49–53 were identified for eventual analysis (2 groups of 7 were repeated data: Sharma et al and Fujita et al52,54; Nishimaki et al53,55). The distribution of LNM for these studies is not shown here. The integrated LNMR of each station in different locations for TEC is shown in Figure 4. When the station was unclear, or if it had no result of this station for count in the study, that paper was excluded for calculating the LNMR for that particular station.

Figure 4.

The LNMR of different stations in the upper TEC (A); the middle TEC (B); and the lower TEC (C) (%).

Notes: Numbers and naming of main regional LN. 101, cervical paraesophageal LN; 102, deep cervical LN; 104, supraclavicular LN; 105, upper thoracic paraesophageal LN; 106, thoracic paratracheal LN; 106rec, recurrent nerve LN; 106pre, pretracheal LN; 107, subcarinal LN; 108, middle thoracic paraesophageal LN; 109, main bronchus LN; 110, lower thoracic paraesophageal LN; 112, posterior mediastinal LN; 113, ligamentum arteriosum LN; 1, right paracardial LN; 2, left paracardial LN; 3, lesser curvature LN; 4, LN along the greater curvature; 5, suprapyloric LN; 6, infrapyloric LN; 7, LN along the left gastric artery; 8, LN along the common hepatic artery; 9, LN along the celiac artery.

Abbreviations: L, left; R, right; LN, lymph nodes; LNMR, lymph node metastasis rate; TEC, thoracic esophageal cancer.

In the neck, the LNMR of each station is station 101>station 104 and station 101R>station 101L. As shown in Figure 2, station 101 is generally the uppermost collecting LN and the right PLC is well developed. However, extramural ascending vessels to cervical paraesophageal LN are much fewer than that to recR and recL. Compared to station 106rec, the high LNMR in station 101 may indicate the direct drainage from submucosal lymphatic plexus. The collateral lymphatic vessels of recR may be another reason.30 Interestingly, compared to station 104R which receives much more vessels, the LNMR of station 104L decreases insignificantly when the location changes from upper TEC to lower TEC. Virchow’s nodes from descending lymphatic drainage through TD should be the main reason.38,39

In the mediastinum, the LNMR for station 106 is station 106recR>station 106recL (station 106L)>station 106R>station 106pre. The high LNMR of station 106recR for all TEC may be due to the direct drainage from the sub-mucosal lymphatic plexus and well developed right PLC. What is more, the recR has a high cortical proportion and few anthracotic macrophages without hyalinization, which facilitates to trap the migrating cancer cells.30 Though it is not verified, the direct drainage to recL from submucosal lymphatic plexus may also exist. As shown in Figure 2, the right paratracheal LN (station 106R) partly relays the right ascending extramural lymphatic drainage. The extramural lymphatics of the lower and middle thoracic esophagus are consistently connected to subcarinal LN and submucosal-lymphatics occasionally connect to subcarinal LN directly. As a result, the LNMR of station 107 is over 5.0% for all locations of TEC. The paraesophageal lymph node usually originates from intermuscular lymphatic plexus. Due to the poor lymphatic communication between intermuscular space and submucosa, LNM of paraesophageal LN is sign of more advanced TEC. Therefore, the LNMR of thoracic paraesophageal lymph node (station 105, station 108, and station 110) varies greatly according to the location and T stage (depth of tumor invasion) of TEC. The LNMR of sta tion 112 is over 5.0% for the middle and lower TEC, which may be due to thoracic paraaortic node chain (Figure 2A) in the mesoesophagus fascia. The LNMR of station 109R, station 109L, or station 113 is <5.0% for all TEC.

The celiac LNMR is usually station 7>station 2>station 1>station 9>station 8. The ascending branches from the left gastric and the left inferior phrenic arteries are important components of the distal mesoesophagus.56 Therefore, station 7 (LN along the left gastric artery) may be the major celiac collecting lymphatics. Paracardial LN (station 1 and station 2) should be another crucial relayed LN in the celiac area. The LNMR of station 3 (lesser curvature LN) is also high, even for upper TEC. These results may indicate that lesser curvature LN receives the submucosal descending lymphatic drainage.

Figure 4A shows that the LNM of upper TEC is mainly ascending to the upper mediastinal and cervical area. There is a high LNMR (33.3 %) in the upper thoracic paraesophageal LN (station 105) for upper TEC, which does not match with the result of Figure 2 (poorly developed). Only one study had investigated this station in our result.53 The LNMR is about 0%–22.2% for upper TEC in other studies.4,57 Though the LNMR is low, LNM can be found in lower mediastinum and celiac area for upper TEC. Figure 4C shows that LNM of lower TEC is frequently in perigastric area and middle and lower paraesophageal area, while LNM in upper mediastinum and neck is also common. Figure 4B shows that the LNM for middle TEC is evidently bidirectional. The LNMR of cervical and upper mediastinal area decreases and the LNM of celiac area increases compared to upper TEC while the opposite compared to lower TEC.

Conclusion

Except epithelium and its basement membrane, lymphatic vessels exist in all layers of the esophagus. The lymphatic vessels run longitudinally in submucosa and muscularis mucosae, while circumferentially in muscularispropria. Longitudinal lymphatic vessels and long drainage territory should be the anatomical bases for bidirectional drainage. The submucosal vessels for direct extramural drainage are usually thick while connective lymphatic vessels between the submucosa and intermuscular area are usually not clearly found, which does not facilitate transversal drainage to paraesophageal LN from submucosa. Direct drainage to TD from submucosa is common, especially for the left esophageal wall. Direct drainage to the recR and subcarinal LN from submucosa has been verified. Other nodes in lower neck, upper mediastina, and upper abdomen may have the same way. The right PLC is well developed, while the left PLC is poorly developed.

Clinical data verified that LNM can be found from the neck to the celiac area for every location of TEC. LNM is frequently present in the lower neck, upper mediastinum and perigastric area. The LNMR in different stations of TEC is variable according to the change of tumor location, T stage, individual differences, etc. However, there are some crucial LN for extramural relay which have a high LNMR, such as cervical paraesophageal LN, recR, and recL, subcarinal LN, LN along the left gastric artery, lesser curvature LN, and paracardial LN. It was found that the station of resected LN rather than the number of resected LN may be more important for lymphadenectomy.58 Resection of recR and recL can improve the prognosis of TEC.59,60 Subcarinal LN dissection is also necessary for esophagectomy of TEC.61,62 By 3FL in superficial EC, it was found that 51% LNM occurred in the deep cervical region and around recurrent laryngeal nerves, and 33% occurred in the perigastric region,63 suggesting that submucosal direct drainage is the major route. Other researches also had the same results.64,65 Metastasis of thoracic paraesophageal LN is a sign of more advanced EC because its afferent is likely to originate at intermuscular lymphatic plexus.

The lymphatic drainage of inner layer (mucosa and sub-mucosa) and outer layer (muscularispropria and adventitia) of the esophagus is different. The lymphatic metastasis seems to be in all the length of the esophagus for TEC. Therefore, 3FL with total esophagus resection or wide-range LN (from neck to celiac area) and total esophagus irradiation should be a radical method for TEC theoretically, even for an early-stage TEC. However, these methods result in more treatment intolerance and complications. Multimodality treatment has been widely investigated in order to improve the poor survival of EC.66 Chemotherapy not only can eradicate distant metastasis or micrometastasis but also can enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy when concurrent chemoradiotherapy is used. Perioperative radiotherapy or/and chemotherapy improves the chance of radical surgery. However, we should balance the merits and faults of different therapies for making a standard treatment, not just put these therapies together. For a best multimodality treatment, it is questionable whether a standard lymphadenectomy is needed or whether LN irradiation with or without chemotherapy can be an effective alternative to lymphadenectomy, especially for LN in neck and upper mediastina where it is difficult for surgery. With the rapid development in different agencies, more safe and effective methods with a better quality of life are proposed for TEC. Beyond that, the anatomical investigation of the lymphatic drainage of the esophagus is further needed.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth EC, Lagergren J, Fitzgerald RC, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17048. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, Lagergren P. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2383–2396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isono K, Sato H, Nakayama K. Results of a nationwide study on the three-field lymph node dissection of esophageal cancer. Oncology. 1991;48(5):411–420. doi: 10.1159/000226971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akutsu Y, Uesato M, Shuto K, et al. The overall prevalence of metastasis in T1 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 295 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257(6):1032–1038. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827017fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hölscher AH, Bollschweiler E, Schröder W, Metzger R, Gutschow C, Drebber U. Prognostic impact of upper, middle, and lower third mucosal or submucosal infiltration in early esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):802–808. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182369128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi YK, Chen Y, Li XT, Sun YS. Prognostic significance of the size and number of lymph nodes on pre and post neoadjuvant chemotherapy CT in patients with pN0 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a 5-year follow-up study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):61662–61673. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugawara K, Yamashita H, Uemura Y, et al. Numeric pathologic lymph node classification shows prognostic superiority to topographic pN classification in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 2017;162(4):846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Liang H, Gao Y, et al. Metastatic lymph node ratio demonstrates better prognostic stratification than pN staging in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after esophagectomy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38804. doi: 10.1038/srep38804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shao Y, Geng Y, Gu W, et al. Assessment of lymph node ratio to replace the pN categories system of classification of the TNM system in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1774–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shang QX, Chen LQ, Hu WP, Deng HY, Yuan Y, Cai J. Three-field lymph node dissection in treating the esophageal cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(10):E1136–E1149. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.10.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natsugoe S, Matsumoto M, Okumura H, et al. Clinical course and outcome after esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy in esophageal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395(4):341–346. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu PK, Chen HS, Huang CS, et al. Patterns of recurrence after oesophagectomy and postoperative chemoradiotherapy versus surgery alone for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2017;104(1):90–97. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xi M, Xu C, Liao Z, et al. The impact of histology on recurrence patterns in esophageal cancer treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2017;124(2):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosekrans SL, Baan B, Muncan V, van den Brink GR. Esophageal development and epithelial homeostasis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309(4):G216–G228. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00088.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brotons ML, Bolca C, Fréchette E, Deslauriers J. Anatomy and physiology of the thoracic lymphatic system. Thorac Surg Clin. 2012;22(2):139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhemchuzhnikova LE. Age changes in the anatomy of the lymphatic system of the human pancreas. Arkh Anat Gistol Embriol. 1959;36(3):53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brundler MA, Harrison JA, de Saussure B, de Perrot M, Pepper MS. Lymphatic vessel density in the neoplastic progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(2):191–195. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.028118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice TW, Bronner MP. The esophageal wall. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(2):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yajin S, Murakami G, Takeuchi H, Hasegawa T, Kitano H. The normal configuration and interindividual differences in intramural lymphatic vessels of the esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(6):1406–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimori H, Hayashi S, Naito M, Murakami G, Fujita M, Hosokawa M. Mucosal lymphatic vessels of the esophagus distant from the cancer margin: morphometrical analysis using 27 surgically removed specimens of squamous cell carcinoma located in the upper or middle thoracic esophagus. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2011;88(2):43–47. doi: 10.2535/ofaj.88.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagai K, Noguchi T, Hashimoto T, Uchida Y, Shimada T. The organization of the lamina muscularis mucosae in the human esophagus. Arch Histol Cytol. 2003;66(3):281–288. doi: 10.1679/aohc.66.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto T, Noguchi T, Nagai K, Uchida Y, Shimada T. The organization of the communication routes between the epithelium and lamina propria mucosae in the human esophagus. Arch Histol Cytol. 2002;65(4):323–335. doi: 10.1679/aohc.65.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice TW, Zuccaro G, Adelstein DJ, Rybicki LA, Blackstone EH, Gold-blum JR. Esophageal carcinoma: depth of tumor invasion is predictive of regional lymph node status. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65(3):787–792. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice TW. Superficial oesophageal carcinoma: is there a need for three-field lymphadenectomy? Lancet. 1999;354(9181):792–794. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raja S, Rice TW, Goldblum JR, et al. Esophageal submucosa: the watershed for esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(6):e1401, 1403–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomita N, Matsumoto T, Hayashi T, et al. Lymphatic invasion according to D2-40 immunostaining is a strong predictor of nodal metastasis in superficial squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: algorithm for risk of nodal metastasis based on lymphatic invasion. Pathol Int. 2008;58(5):282–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oshiro H, Osaka Y, Tachibana S, Aoki T, Tsuchiya T, Nagao T. Retrograde lymphatic spread of esophageal cancer: a case report. Medicine. 2015;94(27):e1139. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hahn HP, Shahsafaei A, Odze RD. Vascular and lymphatic properties of the superficial and deep lamina propria in Barrett esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(10):1454–1461. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817884fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizutani M, Murakami G, Nawata S, Hitrai I, Kimura W. Anatomy of right recurrent nerve node: why does early metastasis of esophageal cancer occur in it? Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28(4):333–338. doi: 10.1007/s00276-006-0115-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuge K, Murakami G, Mizobuchi S, Hata Y, Aikou T, Sasaguri S. Submucosal territory of the direct lymphatic drainage system to the thoracic duct in the human esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125(6):1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami G, Sato I, Shimada K, Dong C, Kato Y, Imazeki T. Direct lymphatic drainage from the esophagus into the thoracic duct. Surg Radiol Anat. 1994;16(4):399–407. doi: 10.1007/BF01627660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murakami G, Abe M, Abe T. Last-intercalated node and direct lymphatic drainage into the thoracic duct from the thoracoabdominal viscera. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(3):93–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02913469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stecco C, Sfriso MM, Porzionato A, et al. Microscopic anatomy of the visceral fasciae. J Anat. 2017;231(1):121–128. doi: 10.1111/joa.12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuesta MA, Weijs TJ, Bleys RL, et al. A new concept of the anatomy of the thoracic oesophagus: the meso-oesophagus. Observational study during thoracoscopicesophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(9):2576–2582. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis PN. Anatomy of the lymphatics. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito H, Sato T, Miyazaki M. Extramural lymphatic drainage from the thoracic esophagus based on minute cadaveric dissections: fundamentals for the sentinel node navigation surgery for the thoracic esophageal cancers. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29(7):531–542. doi: 10.1007/s00276-007-0257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murakami G, Sato T, Takiguchi T. Topographical anatomy of the bron-chomediastinal lymph vessels: their relationships and formation of the collecting trunks. Arch Histol Cytol. 1990;53(Suppl):219–235. doi: 10.1679/aohc.53.suppl_219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizutani M, Nawata S, Hirai I, Murakami G, Kimura W. Anatomy and histology of Virchow’s node. Anat Sci Int. 2005;80(4):193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2005.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riquet M. Bronchial arteries and lymphatics of the lung. Thorac Surg Clin. 2007;17(4):619–638. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aikou T, Shimazu H. Difference in main lymphatic pathways from the lower esophagus and gastric cardia. Jpn J Surg. 1989;19(3):290–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02471404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Natsugoe S. Experimental and clinical study on the lymphatic pathway draining from the distal esophagus and gastric cardia. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;90(3):364–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arakawa M, Masuzaki T, Okuda K. Pathomorphology of esophageal and gastric varices. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22(1):073–082. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suga K, Shimizu K, Kawakami Y, et al. Lymphatic drainage from esophagogastric tract: feasibility of endoscopic CT lymphography for direct visualization of pathways. Radiology. 2005;237(3):952–960. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2373041578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okanobu K. The lymphatics of the esophagus – evaluation of endoscopic RI-lymphoscintigraphy with SPECT. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;91(7):808–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmid-Schönbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(4):987–1028. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riquet M, Le Pimpec Barthes F, Souilamas R, Hidden G. Thoracic duct tributaries from intrathoracic organs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(3):892–898. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Japan Esophageal Society Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, 11th edition: part I. Esophagus. 2017;14:1–36. doi: 10.1007/s10388-016-0551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jang HJ, Lee HS, Kim MS, Lee JM, Zo JI. Patterns of lymph node metastasis and survival for upper esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(3):1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kato H, Tachimori Y, Watanabe H, et al. Lymph node metastasis in thoracic esophageal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1991;48(2):106–111. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930480207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, Liu S, Pan J, et al. The pattern and prevalence of lymphatic spread in thoracic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36(3):480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma S, Fujita H, Yamana H, Kakegawa T. Patterns of lymph node metastasis in 3-field dissection for carcinoma in the thoracic esophagus. Surg Today. 1994;24(5):410–414. doi: 10.1007/BF01427033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishimaki T, Tanaka O, Suzuki T, Aizawa K, Hatakeyama K, Muto T. Patterns of lymphatic spread in thoracic esophageal cancer. Cancer. 1994;74(1):4–11. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940701)74:1<4::aid-cncr2820740103>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Yamana H, et al. Lymph node metastasis and recurrence in patients with a carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus who underwent three-field dissection. World J Surg. 1994;18(2):266–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00294412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishimaki T, Suzuki T, Tanaka Y, Nakagawa S, Aizawa K, Hatakeyama K. Evaluating the rational extent of dissection in radical esophagectomy for invasive carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Surg Today. 1997;27(1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01366932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tachimori Y. Total mesoesophagealesophagectomy. Chin Med J. 2014;127(3):574–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ding X, Zhang J, Li B, et al. A meta-analysis of lymph node metastasis rate for patients with thoracic oesophageal cancer and its implication in delineation of clinical target volume for radiation therapy. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1019):e1110–e1119. doi: 10.1259/bjr/12500248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyata H, Yamasaki M, Makino T, et al. Therapeutic value of lymph node dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J SurgOncol. 2015;112(1):60–65. doi: 10.1002/jso.23965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ye K, Xu JH, Sun YF, Lin JA, Zheng ZG. Characteristics and clinical significance of lymph node metastases near the recurrent laryngeal nerve from thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(3):6411–6419. doi: 10.4238/2014.August.25.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shiozaki H, Yano M, Tsujinaka T, et al. Lymph node metastasis along the recurrent nerve chain is an indication for cervical lymph node dissection in thoracic esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14(3–4):191–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2001.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niwa Y, Koike M, Hattori M, et al. The prognostic relevance of sub-carinal lymph node dissection in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(2):611–618. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4819-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J, Hu Y, Xie X, Fu J. Subcarinal node metastasis in thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(2):423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matsubara T, Ueda M, Abe T, Akimori T, Kokudo N, Takahashi T. Unique distribution patterns of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with superficial carcinoma of the thoracic oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1999;86(5):669–673. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kato H, Tachimori Y, Mizobuchi S, Igaki H, Ochiai A. Cervical, mediastinal, and abdominal lymph node dissection (three-field dissection) for superficial carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Cancer. 1993;72(10):2879–2882. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931115)72:10<2879::aid-cncr2820721004>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Endo M, Yoshino K, Kawano T, Nagai K, Inoue H. Clinicopathologic analysis of lymph node metastasis in surgically resected superficial cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13(2):125–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klevebro F, Ekman S, Nilsson M. Current trends in multimodality treatment of esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer – review article. Surg Oncol. 2017;26(3):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]