Abstract

Background & Aims

Ticagrelor has been acknowledged as a new oral antagonist of P2Y12-adenosine diphosphate receptor, as a strategy with more rapid onset as well as more significant platelet inhibition function in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. The clinical benefit of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel remains controversial. The current meta-analysis was conducted to better evaluate the role of ticagrelor in comparison of clopidogrel in treating ACS patients.

Methods

The publications involving the safety as well as the efficacy of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor were screened and identified updated to June 2018. After rigorous review, eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were extracted and propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was conducted. To analyze the summary odds ratios (ORs) of the endpoints of interest, we applied Meta-analysis Revman 5.3 software.

Results

There were a total of 10 studies that met our inclusion criteria, of which the risk of bleeding rate (P = 0.43), MI (P = 0.14), and stroke (P = 0.70) had no association with significant differences between patients receiving ticagrelor or clopidogrel. Nonetheless, higher rate of dyspnea was observed in ticagrelor group (OR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.70–2.05, P<0.00001 = .

Conclusions

Our present findings suggest similar efficacy and safety profiles for clopidogrel and ticagrelor Ticagrelor should be considered as a valuable option to reduce the risk of bleeding, MI and stroke, whereas potentially increases the incidence of dyspnea. Given the metabolic process, ticagrelor may be a valid and even more potent antiplatelet drug than clopidogrel, as an alternative strategy in treating patients with clopidogrel intolerance or resistance.

Keywords: Ticagrelor, Clopidogrel, Acute coronary syndrome, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a series of urgent clinical syndromes in the coronary arteries because of decreased blood flow. It has been acknowledged that occurrence as well as the development of ACS has a strong link to platelet aggregation. Therefore, standard treatment has been established with the use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with P2Y12 receptor inhibitor and aspirin for ACS patients regardless previous treatments, such as medical management or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1, 2].

Clopidogrel, a P2Y12 receptor antagonist as a valid antiplatelet drug for patients ACS patients, has been extensively used worldwide for over a decade. As a prodrug, it often requires hepatic conversion and leads to onset delay of metabolites with a wide variability of platelet inhibition between individuals, and more than one-third of them display minimal platelet inhibition or “clopidogrel non responders” [3–5]. Moreover, the high bleeding risk, stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction (MI) and poor response of patients with the use of clopidogrel show the limitation of its efficacy [6–8]. Hence, slow onset and low potency of platelet inhibition of clopidogrel has been found based on previous publications [9].

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting oral antagonist of P2Y12-adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor blocker with reversibility and without catabolite activation, which can have a substantial impact on faster and greater platelet inhibition than clopidogrel [10, 11]. Ticagrelor has more remarkable beneficial outcomes in reversible long-term P2Y12 inhibition than clopidogrel in the total death, cardiovascular prevention, stent thrombosis as well as myocardial infarction without increasing the major bleeding rates in a wide ACS patient population with timely intervention, according to the Phase III PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial [12]. Thus, several clinical management guidelines suggested that ticagrelor could be a valid strategy and associated with superior effects over clopidogrel for P2Y12 inhibition in ACS patients [13, 14].

Earlier studies have been published for the assessment of safety and efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in ACS patients Nevertheless, given the differences of genetic backgrounds, comorbidities, disease patterns, and demographics, patients tend to show various prognostic results with uncertain bleeding risk [15, 16].

Therefore, attempts have been made in the present study in order to offer conclusive clinical evidence on the controversial results through this meta-analysis that evaluates the safety and efficacy profile of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in ACS patients.

Methods and materials

Search strategy

An electronic search of literature using Embase, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library was conducted by two reviewers separately up to June 2018. All publications with the following keywords were included: “Ticagrelor”; “Clopidogrel” and “Acute coronary syndrome”. We also applied the associated Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms. References from relevant studies and review literatures were further searched to confirm retrieval of all possible pertinent trials.

Eligibility criteria

Qualified Studies were assessed based on the following criteria [1]: the studies are designed as random control trials (RCTs) and propensity score matching (PSM) control trials comparing clopidogrel versus ticagrelor [2]; inclusion of patients with ACS [3]; the incidence of vascular effects as well as major adverse cardiovascular were considered as the primary efficacy end point, which was also defined as the composite events of stroke, myocardial infarction(MI), bleeding and dyspnea.

Quality assessment

The quality of retrieved studies was rated and collected separately by two studiers (Dong Wang and Xiao-Hong Yang). And the quality of observational studies was under assessment with the use of Newcastle- Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale [17]. RCTs were graded using the Jadad scale [18].

Data extraction

Data from each included study were checked and collected for consistency by two investigators. Any arising disagreements were settled through discussion to reach general consensus. The main categories from each of the eligible studies were included on the basis of the following parameters: family name of first author, year of publication, study design, dose and method of drugs, number of patients, follow-up time, and clinical outcome.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were carefully conducted through the use of Review Manager version 5.3 software (Revman; The Cochrane collaboration Oxford, United Kingdom). We used the inverse variance method for the calculation of endpoints of interest based on ORs with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs); the individual estimate of the OR was weighted through endpoint outcomes across each study.

The heterogeneity across studies was examined through the I2 statistic to evaluate the sensitivity [19], describing as follows respectively: low, I2<50%; moderate or high, I2 ≥ 50% [20]. We applied the fixed-effect models when low heterogeneity showed in studies. In other cases, we used the random effects model. Studies with a P value less than 0.05 was thought to have statistical significance.

Results

Searched outcomes and general features of the trials

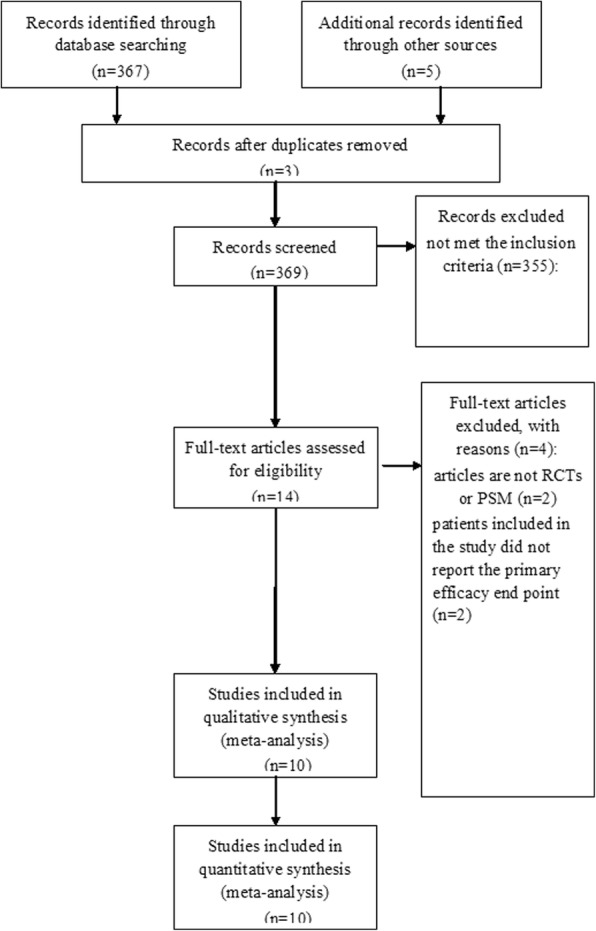

Electronic search of literatures resulted in a total number of 369 publications originally. On the basis of the abovementioned criteria, assessment of detail was carried out and 14 publications were included, whereas some articles were excluded due to the lack of outcomes of two approaches. Hence, there were a total number of 10 studies with eligibility [12, 21–29]. Figure 1 revealed the detailed search process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of selection process to identify eligible studies

The abovementioned studies were based on evidence with moderate to high quality. Table 1 described the major characteristics of the qualified studies in more detail.

Table 1.

Major characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Publication year | Study design | No. Patients | Drug Dose | Follow-up, mo | Clinical Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor, mg.q.d | Clopidogrel, mg.q.d | |||||

| Cannon | 2007 | RCT | 6732 | 6676 | 90 mg.bid | LD: 300 MD: 75 | 3 | 1、2、3、4 |

| Lars Wallentin | 2009 | RCT | 9333 | 9291 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 300–600 MD: 75 | 12 | 1、2、3、4 |

| Cannon | 2010 | RCT | 663 | 327 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 300 MD: 75 | 12 | 1、2、3 |

| Laurent Bonello | 2014 | RCT | 30 | 30 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 600 MD: 75 | N | 4 |

| Y. Hiasa | 2014 | RCT | 93 | 46 | 90/45 mg.bid | 75 | 3 | 3 |

| Shinya Goto | 2015 | RCT | 401 | 400 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 300 MD: 75 | 12 | 1、2、3 |

| Huidong Wang | 2016 | RCT | 100 | 100 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 300 MD: 75 | 12 | 1、2、3 |

| Ran Xiong | 2015 | RCT | 112 | 112 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 600 MD: 150 | 12 | 1 |

| I-Chih Chen | 2016 | PSM | 224 | 224 | / | / | 12 | 1、2、3、4 |

| Cheng-Han Lee | 2018 | PSM | 2389 | 19,112 | LD: 180 mg.bid MD: 90 mg.bid | LD: 300–600 MD: 75 | 18 | 1、2、3 |

RCT random control trial, PSM propensity score matching, LD loading dose, MD maintenance dose

Outcome [1]: MI [2]; stroke [3]; TIMI-defined bleeding [4]; Dyspnea

Clinical and methodological heterogeneity

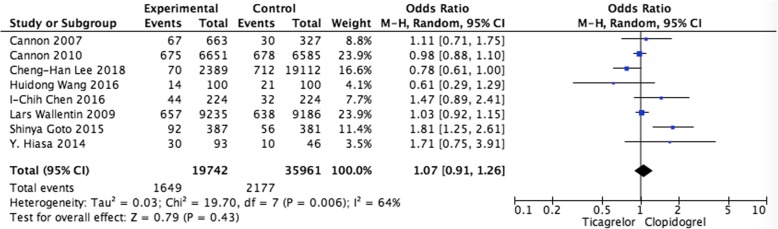

Pooled analysis of the risk of bleeding

Pooled data from 8 studies showed no differences in the risk of bleeding (OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.91–1.26, P = 0.43) when comparing ticagrelor and clopidogrel group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled analysis of the risk of bleeding between ticagrelor and clopidogrel

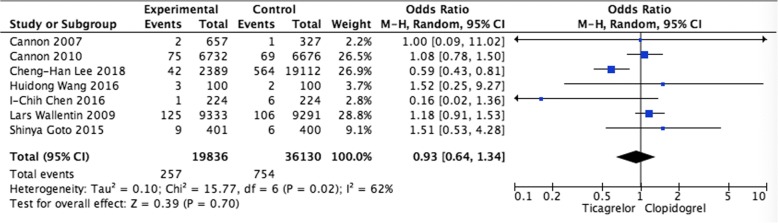

Pooled analysis of stroke Stroke rate was available for 7 trials. No significant differences were observed when comparing ticagrelor and clopidogrel (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.64–1.34, P = 0.70) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pooled analysis of stroke between ticagrelor and clopidogrel

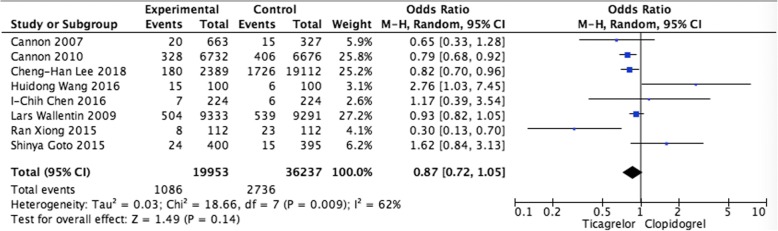

Pooled analysis of MI

In the analysis of MI in patients who were treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel, eight studies were included. Pooled data revealed that ticagrelor was not associated with higher trend of rate than clopidogrel, with the pooled OR being 0.87 (95% CI 0.72–1.05, P = 0.14) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pooled analysis of MI between ticagrelor and clopidogrel

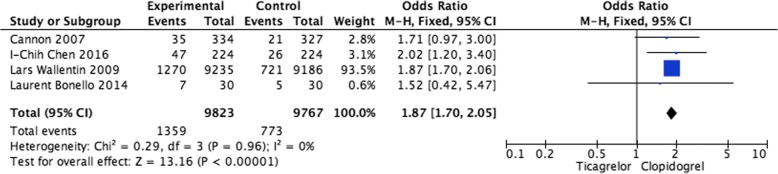

Pooled analysis of dyspnea events The incidences of dyspnea events in patients with ACS were available for four studies (Fig. 5). The pooling analysis revealed that ticagrelor was linked to a higher rate of dyspnea (OR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.70–2.05, P<0.00001).

Fig. 5.

Pooled analysis of dyspnea events between ticagrelor and clopidogrel

Discussion

Dual antiplatelet therapy, usually accompanied with a P2Y12 receptor antagonist and aspirin, is generally acknowledged as a vital approach in treating ACS patients, partly because of the increased occurrence of thrombogenesis. Dual antiplatelet therapy has been also regarded as a standard therapy especially after PCI according to several clinical guidelines [14, 30].

Clopidogrel, a P2Y12 receptor antagonist, has been generally utilized with aspirin as prescribed antiplatelet agents in an attempt to decrease the MI risk and stent thrombosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes with or without ST elevation [22]. However, clopidogrel requires 2-step hepatic metabolism as an inactive pro-drug that has a strong link to delayed onset and various responses [31, 32].

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting oral antagonist of P2Y12-receptor antagonist with reversibility and without catabolite activation, which can have a substantial impact on faster with consistent greater platelet inhibition than clopidogrel [10, 12].

However, previous trial supported by some studiers demonstrated no remarkable difference in terms of the bleeding rate with the use of ticagrelor in comparison of clopidogrel. Additionally, results of ventricular pauses on Holter monitoring as well as the dose-related episodes of dyspnea were found with high occurrence when using ticagrelor [12]. We conducted the study to evaluate the function of ticagrelor in terms of its superior effect to clopidogrel for ACS patients.

The present analysis showed no statistical reduction of bleeding incidence, MI as well as stroke in ticagrelor in comparison of clopidogrel. Nonetheless, dyspnea was more common in the ticagrelor group.

Although susceptibility of higher bleeding risk was affected by platelet inhibition, controversy existed regarding to the link of bleeding risk and platelet inhibition level, of which the risk of major bleeding based on platelet inhibition level has not been estimated [33, 34]. As shown in human race, there is variation in the drug response with different populations. Comparing with non-Asian patients, Asian patients tend to be more susceptive with high bleeding risk in terms of the lower body weight, different genetic background, disease patterns as well as comorbidities [35]. Higher bleeding risk in Asian population has gained interests with standard doses of new P2Y12 inhibitors, especially in East Asian patients [36]. Furthermore, on basis of clinical experience and evidence, there may be a dissimilarity between the Chinese and Japanese patients [37, 38]. It is always important to take different genetic predisposition into consideration in order to perform proper antiplatelet therapy if clopidogrel is applied as a control. Compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor is less likely to be influenced by CYP2C19 polymorphism [39]. The role of platelet inhibition in ticagrelor may gain popularity among Asian patients who are prone to have higher prevalence of loss of CYP2C19 function polymorphism, which may be associated with the remarkable decrease of ischemic events [40].

Increased risk of cardiovascular events usually leads to bleeding [41]. However, the risk factors of subsequent cardiovascular events were associated with major bleeding with differences in degree between Asian and non-Asian patient individuals. Debates exists concerning the reason for the susceptibility of Asian patients to subsequent cardiovascular events. Asian patients who suffer numerically higher subsequent ischemic events are those who are associated with major bleeding than without bleeding [40]. In addition, another strong predictor of adverse prognosis after ACS is the age of patients [42, 43]; ACS patients with older age tend to be accompanied with drug-related bleeding complications and increased risk of CV death. Previous clinical prognosis of older age with ACS is often further complicated by more common comorbidity [44, 45]. The abovementioned findings need further evaluation to offer strong evidence.

Dyspnea is another pivotal parameter as adverse effect in addition to bleeding. In our study, ticagrelor exerted increased dyspnea incidence in comparison of clopidogrel, which mainly due to its function in increasing the inhibition of P2Y12 on sensory neurons and the endogenous adenosine concentration [46–48].

The main strength of our study is the use of a well-maintained and updated database including studies that were designed as random control trials (RCTs) and propensity score matching (PSM) control trials. Nevertheless, potential bias exists by the intrinsic retrospective study and the imbalance in baseline demographics and clinical characteristics, which may impact the comparison of relevant outcomes. More large-scale studies with greater statistical significance are warranted for the confirmation of the safety as well as efficacy profile of ticagrelor and clopidogrel.

Conclusion

In summary, we present a meta-analysis with evidence-based data comparing ticagrelor and clopidogrel in treating ACS patients. Aggregated results showed no increase in major bleeding rate, MI and stroke with the use of ticagrelor except for dyspnea rate. However, considering ticagrelor is less likely to be influenced by metabolic activation and various drug action between individuals, it has potential to be a valid, alternative antiplatelet drug in comparison of clopidogrel. Hence, ticagrelor may be a valid and even more potent antiplatelet drug than clopidogrel, especially as an alternative strategy in treating patients with clopidogrel intolerance or resistance.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

DW and X-H Yang have made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study; J-DZ, R-BL and MJ searched literature, extracted data from the collected literature and analyzed the data; DW and X-RC wrote the manuscript; X-HY revised the manuscript; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet. 2001;358(9281):527–533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9497):1607–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67660-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matetzky S, Shenkman B, Guetta V, et al. Clopidogrel resistance is associated with increased risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:3171–3175. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130846.46168.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiviott SD, Antman EM. Clopidogrel resistance: a new chapter in a fast-moving story. Circulation. 2004;109:3064–3067. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134701.40946.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Hiatt BL, et al. Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation. 2003;107:2908–2913. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072771.11429.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients under- going surgical revascularization for non- ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in unstable angina to prevent recurrent ischemic events (CURE) trial. Circulation. 2004;110:1202–1208. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140675.85342.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in pa- tients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuliczkowski W, Witkowski A, Polonski L, et al. Interindividual variability in the response to oral antiplatelet drugs: a position paper of the working group on antiplatelet drugs resistance appointed by the section of cardiovascular interventions of the polish cardiac society, endorsed by the working group on thrombosis of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:426–435. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tantry US, Bonello L, Aradi D, et al. Consensus and update on the definition of on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate associated with ischemia and bleeding. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(24):2261–2273. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storey RF, Husted S, Harrington RA, et al. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by AZD6140, a reversible oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1852–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husted Steen, Emanuelsson Håkan, Heptinstall Stan, Sandset Per Morten, Wickens Mark, Peters Gary. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the oral reversible P2Y12 antagonist AZD6140 with aspirin in patients with atherosclerosis: a double-blind comparison to clopidogrel with aspirin. European Heart Journal. 2006;27(9):1038–1047. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husted S., James S. K., Bach R. G., Becker R. C., Budaj A., Heras M., Himmelmann A., Horrow J., Katus H. A., Lassila R., Morais J., Nicolau J. C., Steg P. G., Storey R. F., Wojdyla D., Wallentin L. The efficacy of ticagrelor is maintained in women with acute coronary syndromes participating in the prospective, randomized, PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. European Heart Journal. 2014;35(23):1541–1550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li YH, Hsieh IC, Shyu KG, Kuo FY. What could be changed in the 2012 Taiwan ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction guideline? Acta Cardiol Sin. 2014;30(5):360–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the Management of Patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139–e228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt DL, Pare G, Eikelboom JW, et al. The relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and ischaemic and bleeding outcomes in stable outpatients: the CHARISMA genetics study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(17):2143–2150. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta RH, Parsons L, Peterson ED. National Registry of myocardial infarction I. comparison of bleeding and in-hospital mortality in Asian-Americans versus Caucasian-Americans with ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving reperfusion therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(7):925–931. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non randomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed December 27, 2013.

- 18.Jadad Alejandro R., Moore R.Andrew, Carroll Dawn, Jenkinson Crispin, Reynolds D.John M., Gavaghan David J., McQuay Henry J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannon CP, Husted S, Harrington RA, et al. Safety, tolerability, and initial efficacy of AZD6140, the first reversible oral adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel, in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: primary results of the DISPERSE-2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(19):1844–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S, et al. Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study. Lancet. 2010;375(9711):283–293. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonello L, Laine M, Kipson N, et al. Ticagrelor increases adenosine plasma concentration in patients with an acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(9):872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiasa Y, Teng R, Emanuelsson H. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety of ticagrelor in Asian patients with stable coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2014;29(4):324–333. doi: 10.1007/s12928-014-0277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goto S, Huang CH, Park SJ, et al. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese patients with acute coronary syndrome -- randomized, double-blind, phase III PHILO study. Circ J. 2015;79(11):2452–2460. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Wang X. Efficacy and safety outcomes of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in elderly Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1101–1105. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S108965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong R, Liu W, Chen L, Kang T, Ning S, Li J. A randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of doubling dose clopidogrel versus ticagrelor for the treatment of acute coronary syndrome in patients with CYP2C19*2 homozygotes. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(8):13310–13316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen IC, Lee CH, Fang CC, et al. Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome in Taiwan: a multicenter retrospective pilot study. J Chin Med Assoc. 2016;79(10):521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CH, Cheng CL, Kao Yang YH, Chao TH, Chen JY, Li YH. Cardiovascular and bleeding risks in acute myocardial infarction newly treated with Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel in Taiwan. Circ J. 2018;82(3):747–756. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(10):1235–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schomig A. Ticagrelor--is there need for a new player in the antiplatelet-therapy field? N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1108–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0906549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallentin L, Varenhorst C, James S, Erlinge D, Braun OO, Jakubowski JA, et al. Prasugrel achieves greater and faster P2Y12 receptor-mediated platelet inhibition than clopidogrel due to more efficient generation of its active metabolite in aspirin-treated patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:21–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker RC, Bassand JP, Budaj A, et al. Bleeding complications with the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the PLATelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(23):2933–2944. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breet NJ, van Werkum JW, Bouman HJ, et al. Comparison of platelet function tests in predicting clinical outcome in patients undergoing coronary stent implantation. JAMA. 2010;303(8):754–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang TY, Chen AY, Roe MT, et al. Comparison of baseline characteristics, treatment patterns, and in-hospital outcomes of Asian versus non-Asian white Americans with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes from the CRUSADE quality improvement initiative. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(3):391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine GN, Jeong YH, Goto S, et al. Expert consensus document: world heart federation expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in east Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(10):597–606. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiang CE, Zhang S, Tse HF, Teo WS, Omar R, Sriratanasathavorn C. Atrial fibrillation management in Asia: from the Asian expert forum on atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2013;164(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiang CE, Wang KL, Lip GYH. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an Asian perspective. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:789–797. doi: 10.1160/TH13-11-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF, et al. Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9749):1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang HJ, Clare RM, Gao R, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: a retrospective analysis from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J. 2015;169(6):899–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steg PG, Huber K, Andreotti F, et al. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: position paper by the working group on thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1854–1864. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, et al. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2727–2733. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2345–2353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopes RD, Alexander KP. Antiplatelet therapy in older adults with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: considering risks and benefits. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(5 Suppl):16C–21C. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newby LK. Acute coronary syndromes in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2011;12(3):220–222. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328343e9ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belchikov YG, Koenig SJ, Dipasquale EM. Potential role of endogenous adenosine in ticagrelor-induced dyspnea. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(8):882–887. doi: 10.1002/phar.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cattaneo M, Schulz R, Nylander S. Adenosine-mediated effects of ticagrelor: evidence and potential clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(23):2503–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cattaneo M, Faioni EM. Why does ticagrelor induce dyspnea? Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(6):1031–1036. doi: 10.1160/TH12-08-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.