Summary

Objective

To compare the efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with topical capsaicin for pain relief in osteoarthritis (OA).

Design

A systematic literature search was conducted for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining any topical NSAID or capsaicin in OA. Pain relief at or nearest to 4 weeks was pooled using a random-effects network meta-analysis (NMA) in a Frequentist and Bayesian setting. Analysis was conducted for all trials and for trials using drugs listed as licensed for OA in the British National Formulary (BNF).

Results

The trial network comprised 28 RCTs (7372 participants), of which 17 RCTs (3174 participants) were included in the as licensed analyses. No RCTs directly compared topical NSAIDs with capsaicin. Placebo was the only common comparator for topical NSAIDs and capsaicin. Frequentist and Bayesian effect size (ES) estimates were in agreement. Topical NSAIDs were statistically superior to placebo overall (ES 0.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19 to 0.41) and as licensed (ES 0.32, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.39). However, capsaicin was only statistically superior to placebo when used at licensed doses (ES 0.41, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.64). No significant differences were observed in pain relief between topical NSAIDs and capsaicin (overall: ES 0.04, 95% CI −0.26 to 0.33; as licensed: ES-0.09, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.16).

Conclusions

Current evidence indicates that topical NSAIDs and capsaicin in licensed doses may be equally effective for pain relief in OA. Whether the equivalence varies between individuals remains unknown.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Topical, Capsaicin, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), Network, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a major cause of pain and disability for which two topical treatments are used: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and capsaicin1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Topical NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and diclofenac, reversibly block the production of prostanoids, thereby reducing pain and inflammation6. Topical NSAIDs, alongside paracetamol, are recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as first line pharmacological treatments1. Over £32 million's worth of prescriptions of topical NSAIDs were dispensed in community pharmacies in England in 20167. Topical NSAIDs are also freely available over-the-counter and are widely advertised to consumers. Meanwhile, capsaicin, the substance responsible for the warming spiciness of chili peppers, is primarily available on prescription in the UK. Almost 200,000 tubes of 0.025% capsaicin were dispensed in 2016, amounting to over £4 million7. Capsaicin is thought to cause defunctionalisation of spontaneously active peripheral nociceptors that otherwise maintain chronic pain conditions8.

Topical NSAIDs and capsaicin are applied directly to the skin over the painful joint and little to no active drug is absorbed into the bloodstream, resulting in their favourable safety profiles8, 9, 10. Topical administration therefore offers a safe and effective alternative to oral analgesics for people with just one or a few painful peripheral joints, especially for individuals with comorbidities, multiple medications, or those wishing to avoid tablets. The efficacy of topical NSAIDs and capsaicin in OA is documented6, 11, 12, 13, 14, however, no evidence for their relative efficacy is available so far to guide clinicians' prescribing practice. We therefore undertook the present network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare topical NSAIDs with capsaicin in people with symptomatic OA.

Method

Protocol and registration

This work forms part of a project examining the relative efficacy of topical NSAIDs and capsaicin in OA and neuropathic pain. The protocol is published15 and is also available on PROSPERO (2016:CRD42016035254).

Eligibility criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any topical NSAID or capsaicin to placebo in participants with OA were included. No other comparators were included for this analysis and only placebo-controlled trials were examined. Participants with painful physician-diagnosed OA (clinical or radiographic) or chronic joint pain attributable to OA at any site (excluding the spine) were included. Spinal pain was excluded as it is difficult to differentiate between OA pain and back pain secondary to other aetiologies. Trials with pain due to multiple conditions were included if the data for OA could be extracted separately.

Trials had to be a minimum of 1 week duration and report pain outcomes. Full texts published in any language and at any date were considered.

Identification and selection of trials

A search strategy, based on terms for (1) RCTs; (2) topical administration; (3) OA; and (4) capsaicin or NSAIDs, was created (Supplementary Information).

Medline, Embase, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, and Cochrane library were searched up to 16/11/2015. The searches were updated on 10/01/2018. In addition, reference lists of included publications and meta-analyses in the area were searched for eligible trials.

Citations were exported to Endnote where duplicates were removed before titles, abstracts, and full texts were assessed for eligibility.

Data collection and data items

The data were extracted independently by two authors (MSMP and JS) using a data extraction form created for this project. Publications in languages other than English were extracted by colleagues fluent in the language or using the Google Translate smart phone application. The following data were sought:

-

•

Publication details: Author, journal, year

-

•

Trial details: Country of study, trial funder, study design, blinding, setting, duration

-

•

Participant details: Number of participants and withdrawals, age, gender distributions, body mass index, joint affected, method of diagnosing OA

-

•

Intervention/placebo detail: Drug, formulation, dose/concentrations, frequency of application

-

•

Endpoint: Pain scores

The primary end point was pain at or nearest to 4 weeks. Change from baseline pain scores (extracted or calculated) were used. If unavailable, endpoint pain scores or percent change from baseline were used. If pain was measured by more than one instrument in a study, the following hierarchy16, 17, 18 was used to extract pain outcome data: (1) visual analogue scale (VAS) global pain score; (2) categorical global pain score; (3) pain during activity, such as walking; (4) Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale or pain subscale of other disease-specific composite tools; (5) Short Form-36 (SF-36) bodily pain subscale; (6) Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain subscale, McGill pain questionnaire; (7) tenderness; (8) physician's assessment of pain. Where multiple concentrations of a study drug were examined within a study, they were combined as one prior to the effect size (ES) calculations for the overall analyses19.

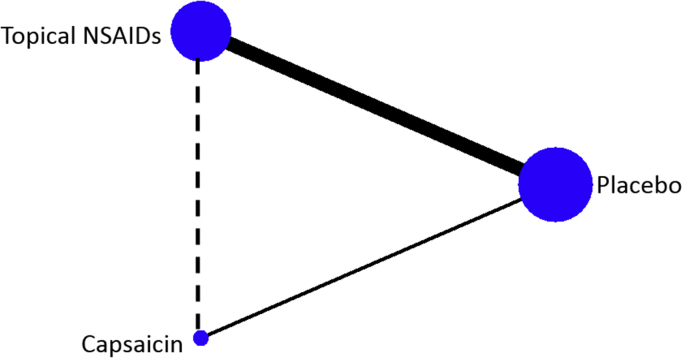

Network structure

A network diagram was plotted to illustrate the treatment nodes, direct comparisons, and indirect comparisons within the NMA.

Risk of bias within and across studies

Risk of bias assessment was carried out independently by two authors (MSMP and JS) using a modified Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Supplementary Material).

Statistical analysis

Hedges' ES and corresponding standard error (SE) were calculated for each study. The estimates were combined using Frequentist and Bayesian random-effects NMAs. The Frequentist ES and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. A Bayesian NMA was conducted using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations. Non-informative prior distributions were set, normal likelihood distributions were assumed, and three Markov chains with different initial values (chosen arbitrarily) were run simultaneously. The model fit was deemed appropriate, the chain converged within 10,000 simulations, and a total of 20,000 simulations comprised the burn-in period. The subsequent 50,000 iterations were examined. The median and the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the posterior distribution comprised the Bayesian ES and credible interval (CrI). The probability of each treatment being the best was calculated.

An overall analysis was conducted using all drug concentrations and topical formulations. Subgroup analysis was then conducted to examine topical NSAIDs and capsaicin used as recommended in the British National Formulary (BNF)20 (Supplementary Material). Trials were excluded from the as licensed analysis if they examined (1) topical NSAIDs not recommended in the BNF; (2) drugs used at concentrations lower than recommended; or (3) licensed drugs in formulations not in the recommended list. The as licensed analysis was conducted to guide clinical practice and inform decision-making based on the medications currently available to physicians.

The frequentist NMA was conducted in Stata (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) using the “network” command21. The Bayesian analyses were conducted in WinBUGs software (version 1.4.3, MRS Biostatistics Unit UK, 2007) using methods supplied by the NICE Decision Support Unit22.

Results

Study description

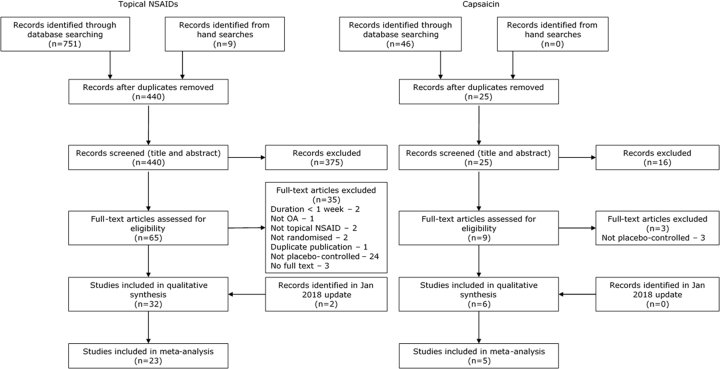

The results of the literature search and reasons for exclusion from this meta-analysis are illustrated in Fig. 1. Topical NSAIDs were compared to placebo in 32 RCTs. Data were not available for extraction for nine of the studies23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and the remaining 23 studies (6957 participants)32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 were included in the NMA. Of these, 13 trials34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 46, 50, 52, 53 used a topical NSAID at its recommended dose/formulation and were included in the as licensed analysis. Six placebo-controlled RCTs examining capsaicin were identified, of which five (415 participants)55, 56, 57, 58, 59 were included in the NMA. Data from the sixth study60 were not available for extraction. Four trials56, 57, 58, 59 used 0.025% capsaicin four times per day, as recommended in the BNF.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Results of the systematic literature search for placebo-controlled trials of topical NSAIDs and capsaicin in OA.

All trials were described as double-blinded and all but one55 were of parallel design. Data from the first period were extracted for the crossover trial. One publication was in Korean48 and the remainder were in English. 24 trials were limited to participants with knee OA, two to hand OA34, 57, and the two remaining trials56, 58 included OA at multiple sites (hand, wrist, elbow, shoulder, hip, knee, and ankle OA).

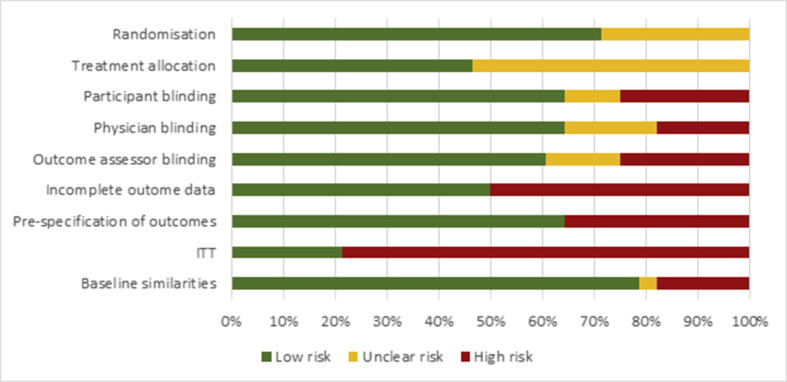

Risk of bias

Trials were associated with considerable risks of bias (Fig. 2). Although described as randomised, only 20 publications described the method of random number sequence generation in sufficient detail to ascertain its risk of bias. Furthermore, only 13 of the included trials adequately described the methods of allocation concealment. Although described as double-blinded, this was only considered adequate in 60–65% of all trials. No capsaicin trials were deemed to adequately blind their participants due to the warming sensation experienced on its initial application. Across the body of evidence, only six of the 28 studies analysed all participants that were randomised at baseline.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment. Risk of bias scores for all studies included in the overall analysis.

NMA

Overall analysis

The trial network was comprised of 28 RCTs with 3473 participants on placebo (28 RCTs), 3693 on topical NSAIDs (23 RCTs), and 206 on capsaicin (5 RCTs) (Fig. 3). Direct evidence for topical NSAIDs vs placebo and capsaicin vs placebo were available from placebo-controlled trials. No trials directly compared topical NSAIDs to capsaicin, and the two treatments were therefore compared using placebo as a common comparator (indirect evidence).

Fig. 3.

Trial network diagram. Nodes (circles) are weighted to represent the number of participants using each intervention. The solid lines represent the direct comparisons of the treatments in RCTs. The dotted line represents indirect comparisons generated through the NMA. The lines are weighted to represent the number of comparisons.

Frequentist and Bayesian analyses were in agreement with identical ES and only minor differences in the CI vs CrI (Table I). Direct estimates indicated that topical NSAIDs were superior to placebo for pain relief. In contrast, the ES estimate between capsaicin and placebo was associated with considerable variability and did not reach statistical significance. However, the indirect analyses found no statistically significant differences between topical NSAIDs and capsaicin, although the ES favoured topical NSAIDs. Topical NSAIDs had the highest probability of being the best treatment, followed by capsaicin and then placebo (Table II).

Table I.

ES and Frequentist CI/Bayesian CrI. Results of the overall and as licensed subgroup analysis of topical NSAIDs and capsaicin in OA

| Comparison | Type | N | Frequentist |

Bayesian |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | CI | ES | CrI | |||

| All trials | ||||||

| Topical NSAID vs placebo | Direct | 23 | 0.30 | 0.19 to 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.19 to 0.43 |

| Capsaicin vs placebo | Direct | 5 | 0.27 | −0.01 to 0.54 | 0.27 | −0.02 to 0.56 |

| Topical NSAIDs vs capsaicin | Indirect | 28 | 0.04 | −0.26 to 0.33 | 0.04 | −0.28 to 0.35 |

| As licensed | ||||||

| Topical NSAID vs placebo | Direct | 13 | 0.32 | 0.24 to 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.24 to 0.42 |

| Capsaicin vs placebo | Direct | 4 | 0.41 | 0.17 to 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.16 to 0.66 |

| Topical NSAIDs vs capsaicin | Indirect | 17 | −0.09 | −0.34 to 0.16 | −0.09 | −0.35 to 0.18 |

N: number of studies.

Table II.

Treatment rankings. The probability of each treatment being the “best” using Frequentist and Bayesian approaches

| Probability of being the best (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Frequentist | Bayesian | |

| All trials | ||

| Topical NSAID | 61.9 | 58.9 |

| Capsaicin | 38.1 | 41.1 |

| Placebo | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| As licensed | ||

| Topical NSAID | 23.5 | 25.9 |

| Capsaicin | 76.5 | 74.1 |

| Placebo | 0.0 | 0.0 |

As licensed analysis

Topical NSAIDs and capsaicin were used as licensed in 17 RCTs. 1705 participants on placebo (17 RCTs), 1328 on topical NSAID (13 RCTs), and 141 on capsaicin (4 RCTs) were included in the as licensed NMA. The results are presented in Table I. Exclusion of non-licensed topical NSAIDs marginally raised the ES and it remained superior to placebo. In contrast, capsaicin at its licensed dose had a considerably increased ES that was statistically superior to placebo. Using placebo as a common comparator, no statistically significant differences remained between topical NSAIDs and capsaicin used as licensed. However, the ES favoured capsaicin, which also had the highest probability of being the best treatment, followed by topical NSAIDs and placebo (Table II).

Discussion

Current evidence indicates that topical NSAIDs and capsaicin, when used as licensed, are both superior to placebo for pain relief. No significant differences were identified in the level of pain relief offered by topical NSAIDs compared to capsaicin. However, limited and poor quality evidence for capsaicin in OA provides uncertainty. Displaying seemingly negligible differences in efficacy, the decision of whether to prescribe topical NSAIDs or capsaicin should be guided by patient preference, safety, costs, and subsequent individual patient response.

Focussing on licensed doses of these two drugs renders the results of this meta-analysis more relevant for clinicians as they relate directly to the drugs recommended for prescription. The list of approved drugs was extracted from the BNF, a resource commonly used to guide prescribing practice in the UK61. The BNF was chosen as the leading authority on clinicians' selection of medicines in the UK, however it should be noted that they offer only recommendations of licensed medications and physicians can prescribe medications outside the recommended list61.

No direct or indirect (via NMA) quantitative evidence of the relative efficacy of topical NSAIDs vs capsaicin has been published previously. Some guidelines, such as those by Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), provide equal recommendations for the two treatments2, 4, 5. This may indicate a perceived equivalence in efficacy, in line with the findings of the current meta-analysis. In contrast, a narrative review examining topical treatments in OA concluded that capsaicin had less efficacy than topical NSAIDs62. Similarly, topical NSAIDs are generally favoured in guidelines such as those by NICE and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), perhaps indicating a postulated greater efficacy for topical NSAIDs1, 3. In addition, OARSI guidelines granted topical NSAIDs a greater mean benefit score (6.0/10) vs capsaicin (5.1/10)2. However, the comparative efficacy of the treatments in the narrative review was concluded primarily based on their mechanism of action, rather than quantitative analysis. Capsaicin was thought to be less effective as it lacked significant tissue penetration and anti-inflammatory effects62. Furthermore, guideline decisions are based not only on perceived efficacy, but on the quality of evidence. Indeed, the preference of topical NSAIDs may reflect a greater confidence in the evidence, rather than a perception of a larger effect. This is in keeping with the wide CI and associated uncertainty in the true effect of capsaicin in the current meta-analysis.

Although pain in OA has traditionally been viewed as nociceptive in nature, it is now widely accepted that some people experience pain with neuropathic-like pain components. Pain descriptors indicative of neuropathic pain, such as “burning” and “shooting” pain are used by subsets of individuals with OA63. In fact, almost 15% of people with knee pain report neuropathic-like pain64. This subgroup is of importance as true neuropathic pain is often difficult to manage and commonly does not respond to traditional analgesics, such as NSAIDs65, 66. Capsaicin, however, is licensed and used in neuropathic pain, where it is effective at higher doses67. It may therefore be that individuals with predominantly nociceptive OA pain benefit from topical NSAIDs whilst those with neuropathic pain components may benefit more from topical capsaicin. Further evidence on pain phenotypes and response to these two commonly used topical analgesics is warranted.

The present meta-analysis is subject to several limitations. Firstly, the conclusions drawn are limited by the scarcity of data available on capsaicin in OA. Only four trials compare 0.025% capsaicin to placebo and no direct estimates were available to compare topical NSAIDs to capsaicin. The low number of studies and participants on capsaicin resulted in an estimate with much uncertainty. The equivalence of the drugs may therefore be an artefact of the wide CIs. Secondly, the probability of being the best treatment is based predominantly on the ES, not on the uncertainty of the estimate. The probability of being the best was chosen to facilitate the translation of results to clinical practice, however the results should be interpreted with caution and in conjunction with the ES estimates. Thirdly, risk of bias assessment identified concerns over the high risk of bias in included trials. Poor compliance with complete outcome data reporting, analysis of all randomised participants, and pre-specification of published outcomes all have the potential to overestimate the results of this meta-analysis. Fourthly, because capsaicin is associated with a warming sensation on application, making it difficult to blind, it was deemed a high risk of bias domain for all capsaicin trials. This may result in inherent differences in the placebo group across the trial network, threatening the assumption of transitivity. Furthermore, the efficacy data for topical NSAIDs is predominantly based on knee OA (22 of 23 studies), whilst the trial population for capsaicin included hand, wrist, elbow, shoulder, hip, knee, and ankle OA. The differences in study populations may limit comparisons between the two treatments, however, it was not possible to conduct subgroup analyses by joint type due to limited data. Finally, by the very nature of analyses conducted at trial-level, the results of this NMA relate to populations of individuals with OA and may not be reflected at the individual patient level. In addition, data were unavailable to examine the efficacy of topical NSAIDs and capsaicin in subgroups with differing OA phenotypes (e.g., nociceptive vs neuropathic-like pain). Studies at the individual patient level are still required.

In conclusion, current evidence indicates that topical NSAIDs and capsaicin offer similar levels of pain relief in OA. Larger and better conducted RCTs, particularly for capsaicin, are required to confirm this. However, it is unknown whether individuals with different pain phenotypes respond differently to these two commonly used topical analgesics. Further work on phenotypic features of OA pain and their response to these two drugs is warranted.

Author contributions

MSMP conceived the work, developed and ran the search strategy, screened trials for eligibility, designed data collection tools, performed data collection, analysed the data, and drafted and revised the paper. JS extracted data for validation and revised the paper. DAW, MD, and WZ were involved in the conceptualisation of the work, interpretation of the data, and revision of the paper. WZ is the guarantor. All authors discussed the results, commented on the manuscript, and have approved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of interest

MSMP and JS declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. DAW reports grants from Arthritis Research UK, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Pfizer Inc., personal fees from GSK Consumer Healthcare, outside the submitted work. MD reports grants from AstraZeneca funding a non-drug PI-led study in Nottingham (Sons of Gout Study), grants from Arthritis Research UK during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Ad hoc Advisory Boards on osteoarthritis and gout for AstraZeneca, Grunenthal, Mallinckrodt and Roche, outside the submitted work. WZ grants from Arthritis Research UK Pain Centre, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from AstraZeneca and Hisun Pharm, royalties to his institution from EULAR, non-financial support from Peking University, Xiangya Hospital, outside the submitted work.

Role of funding source

The work was supported by Arthritis Research UK [grant number 20777]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data synthesis, data interpretation, or writing the report.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Drs Haruna Takahashi, Neele Dellschaft, and Yu Fu for their help with screening and data extraction of publications in Japanese, German, and Chinese.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.08.008.

Contributor Information

M.S.M. Persson, Email: monica.persson@nottingham.ac.uk.

J. Stocks, Email: joanne.stocks@nottingham.ac.uk.

D.A. Walsh, Email: david.walsh@nottingham.ac.uk.

M. Doherty, Email: michael.doherty@nottingham.ac.uk.

W. Zhang, Email: weiya.zhang@nottingham.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.NICE. Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults [CG177]2014 16/10/2015; (CG177). Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177/evidence/cg177-osteoarthritis-full-guideline3.

- 2.McAlindon T., Bannuru R., Sullivan M., Arden N., Berenbaum F., Bierma-Zeinstra S. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(3):363–388. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochberg M.C., Altman R.D., April K.T., Benkhalti M., Guyatt G., McGowan J. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):465–474. doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W., Doherty M., Leeb B., Alekseeva L., Arden N., Bijlsma J. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(3):377–388. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan K., Arden N., Doherty M., Bannwarth B., Bijlsma J., Dieppe P. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–1155. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.011742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derry S., Conaghan P., Da Silva J.A.P., Wiffen P.J., Moore R.A. The Cochrane Library; 2016. Topical NSAIDs for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Adults. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prescribing & Medicines Team P. Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2017. Prescription Cost Analysis, England - 2016.http://content.digital.nhs.uk/article/2021/Website-Search?productid=24706&q=title%3a%22Prescription+Cost+Analysis%22&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1&area=both#top [updated 30/03/2017; cited 2017 17/08/2017]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand P., Bley K. Topical capsaicin for pain management: therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action of the new high-concentration capsaicin 8% patch. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(4) doi: 10.1093/bja/aer260. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haroutiunian S., Drennan D.A., Lipman A.G. Topical NSAID therapy for musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(4):535–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng C., Wei J., Persson M.S.M., Sarmanova A., Doherty M., Xie D. Relative efficacy and safety of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(10):642–650. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin F.Y., Zhang W.Y., Jones A., Doherty M. Efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 2004 Aug;329(7461) doi: 10.1136/bmj.38159.639028.7C. 324-6B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laslett L.L., Jones G. Capsaicin as a Therapeutic Molecule. Springer; 2014. Capsaicin for osteoarthritis pain; pp. 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason L., Moore R.A., Derry S., Edwards J.E., McQuay H.J. Systematic review of topical capsaicin for the treatment of chronic pain. BMJ. 2004;328(7446):991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38042.506748.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W., Li Wan Po A. The effectiveness of topically applied capsaicin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46(6):517–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00196108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson M.S., Fu Y., Bhattacharya A., Goh S.-L., van Middelkoop M., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M. Relative efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and topical capsaicin in osteoarthritis: protocol for an individual patient data meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAlindon T.E., LaValley M.P., Gulin J.P., Felson D.T. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;283(11):1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jüni P., Reichenbach S., Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: rational approach to treating the individual. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20(4):721–740. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juhl C., Lund H., Roos E.M., Zhang W., Christensen R. A hierarchy of patient-reported outcomes for meta-analysis of knee osteoarthritis trials: empirical evidence from a survey of high impact journals. Arthritis. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/136245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins J.P.T., Green S. 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.www.cochrane-handbook.org Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee J.F. BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; London: 2017. British National Formulary.http://www.medicinescomplete.com (online) [cited 2017 27/11/2017]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.White I.R. Network meta-analysis. Stata J. 2015;(15):951–981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dias S., Welton N.J., Sutton A.J., Ades A.E. 2011. NICE DSU Technical Support Document 2: A Generalised Linear Modelling Framework for Pairwise and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials.http://www.nicedsu.org.uk last updated September 2016 21/09/2017. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ergün H., Külcü D., Kutlay S., Bodur H., Tulunay F.C. Efficacy and safety of topical nimesulide in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13(5):251–255. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318156b85f. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/988/CN-00619988/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barthel H.R., Haselwood D., Longley S., Gold M.S., Altman R.D. Randomized controlled trial of diclofenac sodium gel in knee osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.09.002. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gui L., Pellacci F., Ghirardini G. Use of ibuprofen cream in orthopedic outpatients. Double-blind comparison with placebo. <ORIGINAL> Impiego dell'ibuprofen crema in pazienti ambulatoriali di interesse ortopedico. Confronto in Doppia Cecita Con Placebo. Clin Terapeut. 1982;101(4):363–369. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/843/CN-00185843/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kageyama T. A double blind placebo controlled multicenter study of piroxicam 0.5% gel in osteoarthritis of the knee. Eur J Rheumatol Inflamm. 1987;8:114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth S.H. A controlled clinical investigation of 3% diclofenac/2.5% sodium hyaluronate topical gel in the treatment of uncontrolled pain in chronic oral NSAID users with osteoarthritis. Int J Tissue React. 1995;17(4):129–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galeazzi M., Marcolongo R. A placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and tolerability of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, DHEP plaster, in inflammatory peri-and extra-articular rheumatological diseases. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1993;19(3):107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose W., Manz G., Lemmel E.M. Behandlung der aktivierten gonarthrose mit topisch appliziertem piroxicam-gel. Topical application of Piroxicam-gel in the treatment of activated gonarthrosisMünch Med Wschr. 1991;133:562–566. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kageyama T. Pharmaceutical evaluation of KPG-200 (ketoprofen ointment) on arthrosis deformans: double blind controlled study compared with KPG-200 base. Yakuri Chiryo (Jpn Pharmacol Therap) 1984;12(6):2297–2317. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/365/CN-00542365/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto S., Kodama T., Hasegawa Y., Saeki K. Clinical evaluation of indomethacin ointment on osteoarthritis--evaluation by a multicenter double-blind trial (author's transl) Ryumachi [Rheumatism] 1979;19(4):328–336. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/312/CN-00022312/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rother M., Conaghan P.G. A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial in moderate osteoarthritis knee pain comparing topical ketoprofen gel with ketoprofen-free gel. J Rheumatol. 2013 Oct;40(10):1742–1748. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conaghan P.G., Dickson J., Bolten W., Cevc G., Rother M. A multicentre, randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of topical ketoprofen in transfersome gel (IDEA-033) with ketoprofen-free vehicle (TDT 064) and oral celecoxib for knee pain associated with osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2013 Jul;52(7):1303–1312. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altman R.D., Dreiser R.L., Fisher C.L., Chase W.F., Dreher D.S., Zacher J. Diclofenac sodium gel in patients with primary hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009 Sep;36(9):1991–1999. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon L.S., Grierson L.M., Naseer Z., Bookman A.A.M., Zev Shainhouse J. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2009 June;143(3):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rother M., Lavins B.J., Kneer W., Lehnhardt K., Seidel E.J., Mazgareanu S. Efficacy and safety of epicutaneous ketoprofen in transfersome (IDEA-033) versus oral cefecoxib and placebo in osteoarthritis of the knee: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 September;66(9):1178–1183. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niethard F.U., Gold M.S., Solomon G.S., Liu J.M., Unkauf M., Albrecht H.H. Efficacy of topical diclofenac diethylamine gel in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2005 Dec;32(12):2384–2392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baer P.A., Thomas L.M., Shainhouse Z. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with a topical diclofenac solution: a randomised controlled, 6-week trial [ISRCTN53366886] BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2005;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth S.H., Shainhouse J.Z. Efficacy and safety of a topical diclofenac solution (Pennsaid) in the treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the knee - a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Oct;164(18):2017–2023. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bookman A.A., Williams K.S., Shainhouse J.Z. Effect of a topical diclofenac solution for relieving symptoms of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J. 2004;171(4):333–338. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031793. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/786/CN-00490786/frame.html http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC509045/pdf/20040817s00030p333.pdf [Internet]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trnavský K., Fischer M., Vögtle-Junkert U., Schreyger F. Efficacy and safety of 5% ibuprofen cream treatment in knee osteoarthritis. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(3):565–572. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/907/CN-00468907/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rovenský J., Miceková D., Gubzová Z., Fimmers R., Lenhard G., Vögtle-Junkert U. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with a topical non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the efficacy and safety of a 5% ibuprofen cream. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2001;27(5–6):209–221. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/447/CN-00397447/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ottillinger B., Gömör B., Michel B.A., Pavelka K., Beck W., Elsasser U. Efficacy and safety of eltenac gel in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2001;9(3):273–280. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0385. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/216/CN-00347216/frame.html http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1063458400903856/1-s2.0-S1063458400903856-main.pdf?_tid=7c4f25c8-8c7d-11e5-bc4c-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1447690808_f34503605cea0726133a0e956cce000b [Internet]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grace D., Rogers J., Skeith K., Anderson K. Topical diclofenac versus placebo: a double blind, randomized clinical trial in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 1999 Dec;26(12):2659–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandelin J., Harilainen A., Crone H., Hamberg P., Forsskahl B., Tamelander G. Local NSAID gel (eltenac) in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee - a double blind study comparing eltenac with oral diclofenac and placebo gel. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26(4):287–292. doi: 10.3109/03009749709105318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baraf H.S.B., Gold M.S., Clark M.B., Altman R.D. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium 1% gel in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Physician Sportsmed. 2010 Jun;38(2):19–28. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.06.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dreiser R.L., Tisne-Camus M. DHEP plasters as a topical treatment of knee osteoarthritis - a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1993;19(3):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoo B., Choi S.W., Lee M.S., Moon H.B. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with ketoprofen (Ketotop): a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 1996;3(1):70–75. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/652/CN-01046652/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brühlmann P., Michel B.A. Topical diclofenac patch in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(2):193–198. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/440/CN-00437440/frame.html [Internet]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varadi G., Zhu Z., Blattler T., Hosle M., Loher A., Pokorny R. Randomized clinical trial evaluating transdermal Ibuprofen for moderate to severe knee osteoarthritis. Pain Physician. 2013;16(6):E749–E762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kneer W., Rother M., Mazgareanu S., Seidel E.J., group EI-s. A 12-week randomized study of topical therapy with three dosages of ketoprofen in Transfersome® gel (IDEA-033) compared with the ketoprofen-free vehicle (TDT 064), in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Pain Res. 2013;6:743. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S51054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shoara R., Hashempur M.H., Ashraf A., Salehi A., Dehshahri S., Habibagahi Z. Efficacy and safety of topical Matricaria chamomilla L.(chamomile) oil for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21(3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wadsworth L.T., Kent J.D., Holt R.J. Efficacy and safety of diclofenac sodium 2% topical solution for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 4 week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016 01 Feb;32(2):241–250. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1113400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yataba I., Otsuka N., Matsushita I., Matsumoto H., Hoshino Y. Efficacy of S-flurbiprofen plaster in knee osteoarthritis treatment: results from a phase III, randomized, active-controlled, adequate, and well-controlled trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(1):130–136. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2016.1176624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kosuwon W., Sirichatiwapee W., Wisanuyotin T., Jeeravipoolvarn P., Laupattarakasem W. Efficacy of symptomatic control of knee osteoarthritis with 0.0125% of capsaicin versus placebo. J Med Assoc Thail. 2010;93(10):1188–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCleane G. The analgesic efficacy of topical capsaicin is enhanced by glyceryl trinitrate in painful osteoarthritis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. Eur J Pain. 2000;4(4):355–360. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schnitzer T., Morton C., Coker S. Topical capsaicin therapy for osteoarthritis pain: achieving a maintenance regimen. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23(Suppl 3):34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altman R.D., Aven A., Holmburg C.E., Pfeifer L.M., Sack M., Young G.T. Capsaicin cream 0.025% as monotherapy for osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23(Suppl 3):25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deal C.L., Schnitzer T.J., Lipstein E., Seibold J.R., Stevens R.M., Levy M.D. Treatment of arthritis with topical capsaicin: a double-blind trial. Clin Therapeut. 1991;13(3):383–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCarthy G.M., McCarty D.J. Effect of topical capsaicin in the therapy of painful osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(4):604–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ogden J. The British National Formulary: past, present and future. Prescriber. 2017;28(12):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Altman R.D., Barthel H.R. Topical therapies for osteoarthritis. Drugs. 2011 July 01;71(10):1259–1279. doi: 10.2165/11592550-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hochman J.R., French M.R., Bermingham S.L., Hawker G.A. The nerve of osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(7):1019–1023. doi: 10.1002/acr.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernandes G., Sarmanova A., Warner S., Harvey H., Richardson H., Frowd N. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2017. SAT0670 The Prevalence of Neuropathic Pain-like Symptoms and Associated Risk Factors in the Nottingham Community: A Cross-sectional Study. [Conference Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freynhagen R., Bennett M.I. Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain. BMJ. 2009;36:339. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3002. 2009-08-12 11:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thakur M., Dickenson A.H., Baron R. Osteoarthritis pain: nociceptive or neuropathic? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(6):374. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Derry S., Rice A.S., Cole P., Tan T., Moore R.A. The Cochrane Library; 2017. Topical Capsaicin (High Concentration) for Chronic Neuropathic Pain in Adults. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.