Endorheic (hydrologically landlocked) basins spatially concur with arid/semiarid climates. Given limited precipitation but high potential evaporation, their water storage is vulnerable to subtle flux perturbations, which are exacerbated by global warming and human activities. Increasing regional evidence suggests a likely recent net decline in endorheic water storage, but this remains unquantified at a global scale. By integrating satellite observations and hydrological modeling, we reveal that during 2002–2016, the global endorheic system experienced a widespread water loss of about 106.3 Gt yr−1, attributed to comparative losses in surface water, soil moisture, and groundwater. This decadal decline, disparate from water storage fluctuations in exorheic basins, appears less sensitive to El Niño–Southern Oscillation-driven climate variability, implying possible responses to longer-term climate conditions and human water management. In the mass-conserved hydrosphere, such an endorheic water loss not only exacerbates local water stress, it also imposes excess water on exorheic basins, leading to a maximal sea level rise that matches the contribution of nearly half of the land glacier retreat (excluding Greenland/Antarctica). Given these dual ramifications, we suggest the necessity of long-term monitoring of water storage variation in the global endorheic system and inclusion of its net contribution to future sea level budgeting.

Global endorheic basins (Fig. 1a), where surface flow is landlocked from the ocean, cover a fifth of the Earth’s land surface but nearly half of its water-stressed regions1. Many arid and semiarid regions are inherently endorheic, where surface flow is unable to break topographic barriers, and retained in landlocked storage that equilibrates through evaporation2. Because surface flow is scarce in endorheic regions, water storage, particularly in sizable lakes, reservoirs, and aquifers, becomes of vital ecological and social importance. Endorheic water storage can be maintained only if the system fluxes, chiefly through precipitation, evaporation, and groundwater exchanges, remain in a delicate balance. However, recent climate change, notably warming and drying in many arid/semiarid regions3–5, has triggered observable perturbations to the endorheic water balance, intensified further by human water withdrawals, damming, and diversions5–8. Regional evidence of storage declines has been seen for decades in desiccating lakes (e.g., Aral Sea and Great Salt Lake)8,9, retreating glaciers (e.g., Tibetan and Amu Darya)10,11, and depleting aquifers (e.g., Arabian and Persian)12, suggesting a likely enduring decline of the total terrestrial water storage (TWS) within the global endorheic system.

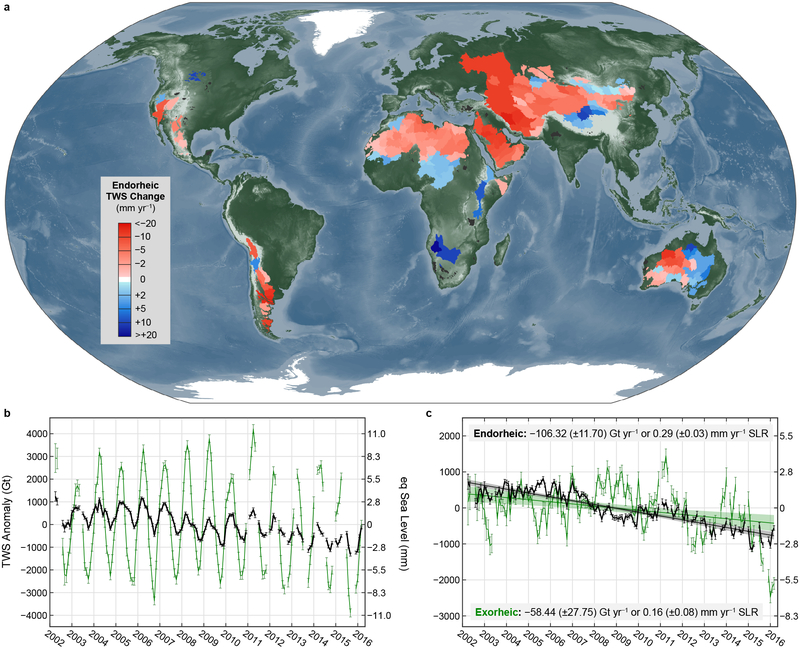

Figure 1.

Terrestrial water storage (TWS) changes within global endorheic and exorheic basins from GRACE observations, April 2002 to March 2016. (a) Trends in individual endorheic units, each comparable to the 3-degree mascon in size (~100k km2). No trends are calculated for sporadic endorheic regions (black) smaller than a mascon. (b) Monthly anomalies in endorheic (black) and exorheic (green) regions. (c) Deseasonalized anomalies (axes as in b). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of monthly anomalies induced by mascon data errors. Shadings illustrate 95% CIs for best-fit linear trends induced by both mascon and rescaling errors (see Methods for uncertainty analysis).

In the mass-conserved hydrosphere, a net endorheic water deficit not only aggravates water stress in endorheic regions, it also imposes the same amount of water surplus on the exorheic system, where surface flow reaches the ocean. Therefore, a persistent TWS decline in global endorheic basins signifies a potential source of sea level rise (SLR). The rate of SLR averaged at ~1.9 mm yr−1 during the past half century13, and increased to ~3.4 mm yr−1 in the current millennium despite occasional hiatuses due to El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)14–16. About 70–80% of the recent decadal SLR was attributed to ocean thermal expansion (~1.2–1.4 mm yr−1) and ice-sheet mass loss in Greenland and Antarctica (~1.0–1.3 mm yr−1). The other ~20–30% was induced by the net TWS change that integrates mountain glacier and ice cap (GIC) loss, groundwater depletion, reservoir impoundment, and mass changes in other stores (e.g., lakes, soil, and permafrost)4,15. Some of these TWS changes, however, were assessed without a discrete consideration of endorheic and exorheic origins, which may overestimate their individual impacts on the sea level budget. For example, glacial meltwater originating from endorheic basins produce no direct excess discharge to the exorheic system11, and reservoirs in endorheic basins do not detain runoff that otherwise drains to the ocean. Owing to observation changes, studies that explicitly assessed endorheic contributions are limited to major terminal lakes that are often considered as basin-wide integrators of climatic and hydrological conditions8,17–21. Particular emphases were given to the strikingly desiccating Aral Sea, and the world’s largest endorheic lake, the Caspian Sea, where water level has shown cyclic fluctuations but an overall lowering since the end of the Little Ice Age (~2 cm yr−1)22. Budget changes in these two lakes and their affected groundwater, if assuming a complete loss to exorheic regions via vapor transfer, contributed a potential SLR of ~0.1–0.2 mm yr−1 at recent decadal to centennial timescales17–19,21,23. Aside from regional evidence, the overall magnitude and spatial pattern of endorheic TWS decline have not been quantified at a global scale, and its net contribution to recent SLR remains unclear.

Here we determine the mass changes in TWS throughout the world’s endorheic basins and the potential impact on SLR during the early twenty-first century. Our monitored TWS is the vertical integration of all water forms on and below the continental surface24, where net mass changes are inverted from time-variable gravity fields observed by NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites25. We use the monthly mass anomalies during April 2002 through March 2016, from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory mascon solution26. This solution isolated TWS signals by removing the noise from the solid earth and improved spatial resolution over conventional spherical-harmonic solutions27. Monthly mascon anomalies are rescaled to 173 endorheic units (Fig. 1a), each aggregated from refined landlocked watersheds until the size exceeds a mascon. Scaled endorheic mass changes are partitioned into the contributions of surface water, soil moisture, and groundwater, in order to contrast possible attributions in different regions. We implement an ensemble of multiple hydrological models (Table S1) to derive monthly anomalies in soil moisture and part of surface water compartments including snowpack and plant canopies. Modeled surface water anomalies are further corrected by storage variations in major lakes/reservoirs estimated from altimetric/optical satellite observations (Fig. S1–S10) and mass changes in GIC derived from stereo imagery11 (Fig. S11; Tables S2–S3). By subtracting the corrected anomalies in land water content from net TWS changes, we then disaggregate the groundwater contribution from those of surface water and soil moisture. Detailed data processing and uncertainty analysis are given in Methods.

Net endorheic storage loss and potential impacts on sea level

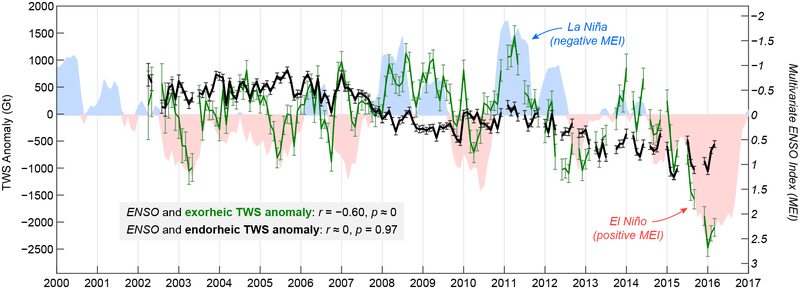

Our results confirm a widespread TWS decline within the global endorheic system during the studied 14 years (Fig. 1). Net water loss prevails in about three quarters of the endorheic units in area (23.2 out of 31.8 million km2) or number (129 out of 173), agglomerated particularly along the water-stressed Subtropical Ridge in Central Asia, the Middle East, and northern Africa (Fig. 1a). In total, the global endorheic system has undergone a net storage change of –106.32 (±11.70) Gt yr−1 (uncertainties in 95% confidence intervals (CIs)). This is about twice the rate of concurrent TWS changes from the entire exorheic region (−58.44 (±27.75) Gt yr−1 excluding Greenland/Antarctica), although the endorheic area is only a fifth of the global landmass (Fig. 1b–c). While the signature in exorheic TWS anomalies is closely linked to ENSO-driven climate variability (Fig. 2, with prominent positive/negative TWS anomalies during La Niña/El Niño events), endorheic anomalies appear less sensitive to such interannual modulations (see Fig. S12 and Table S4 for other climate oscillations). This contrast highlights the possible significance of longer-term climate conditions (e.g., multidecadal variability and anthropogenic warming) and direct human water management to TWS in the arid/semiarid hinderlands4,5,7–9.

Figure 2.

Linkage between TWS anomalies and El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Left y-axis shows deseasonalized monthly anomalies of global exorheic (green) and endorheic (black) TWS (error bars as in Fig. 1c). Right y-axis shows ENSO intensities in multivariate ENSO index (MEI)28,29 (accessed from www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/enso/mei/table.html). Positive MEI values indicate El Niño and negative values La Niña. Exorheic anomalies are significantly corrected with MEI (Pearson r = −0.50, p < 0.001), with the strongest correlation (–0.60) achieved by lagging MEI one season behind TWS anomalies (shown here). Under the same condition, endorheic anomalies appear less sensitive to ENSO modulations (also see Supplementary Information).

The net endorheic water loss, if it completely reaches the ocean, results in an average SLR of 0.29 (±0.03) mm yr−1, accounting for ~9% of the observed SLR (3.4 mm yr−1)16 and ~15–20% of the barystatic (mass-induced) contribution (1.6–2.0 mm yr−1)4,15 around the same period. Compared with other barystatic sources, the endorheic water loss equals nearly half of the global mass decline in GIC (0.6–0.7 mm yr−1 excluding Greenland/Antarctica)4,15, and matches the entire contribution of groundwater depletion (~0.27 mm yr−1)30. This endorheic loss also exceeds the previous estimates of the net inland water change, e.g., in the Caspian Sea, Aral Sea, Lake Chad, Great Salt Lake, and Tibetan lakes8,17–19,21,31, by a factor of ~2–4, which implies substantial but poorly understood changes in hydrological components within the global endorheic system. However, we recognize that our estimated SLR contribution is only the potential barystatic contribution of the net endorheic loss or its sea level equivalent. If assuming that the surplus of water vapor transferred from endorheic basins is evenly precipitated into the exorheic system (including both land and ocean with a negligible net vapor change30) and an average precipitation-to-discharge ratio of 2.4 from land32, we approximate that up to ~80% of the net endorheic TWS loss might end up in the ocean.

Regional variation and links to climate and human actions

Despite a net global decline, the change of endorheic TWS exhibits intriguing regional variation. On one hand, our map of TWS trends for individual endorheic units (Fig. 1a) shows exacerbated water scarcity in many of the world’s drought hotspots. They include not only drainage basins under intense human influences, such as those of the Caspian Sea, Aral Sea, Urmia Lake, Balkhash Lake, and Great Salt Lake, but also remote or sparsely populated deserts in Africa (e.g., Sahara), Central Asia (e.g., Taklamakan and Gobi), the Middle East (e.g., Arabian), South America (e.g., Atacama), western US (e.g., Great Basin and Mojave), and western Australia (e.g., Great Sandy and Gibson). TWS declines in these hotspots accentuate the evident impact of recent meteorological drought on arid/semiarid regions, which is often intertwined with human-induced evaporative loss through surface water diversion, damming, and groundwater abstraction4,5,8,9,33. On the other hand, water losses across most of the endorheic landmass contrast markedly with water gains in the Inner Tibetan Plateau (ITP), eastern Australia, Sahel, Great Rift Valley, Kalahari Desert (southern Africa), and northern Great Basin and Great Plains (North America). However, these water gains are more spatially constrained and are dominantly induced by natural variability5 (Supplementary text).

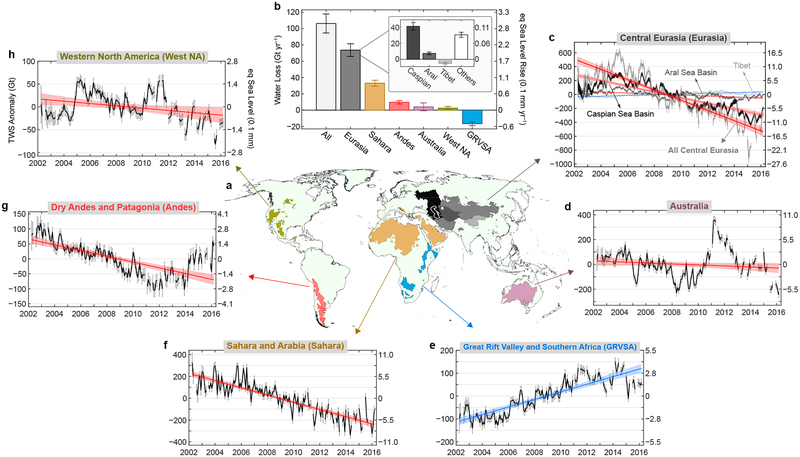

To further contrast regional variation, we group global endorheic basins by continent and climatic similarities into six primary zones (Fig. 3a), where TWS anomalies and changing trends are compared in Fig. 3b–h and Table 1. Approximately two-thirds of the global endorheic water loss (–73.64 (±7.74) Gt yr−1) stems from Central Eurasia, the largest zone covering one-third of the endorheic landmass. Water loss within Central Eurasia generally weakens along an eastward gradient, as illustrated in four secondary zones. Over half of the total zonal loss is concentrated on the Caspian Sea Basin alone, 10% on the Aral Sea Basin (including nearby watersheds receiving transbasin diversions) but largely balanced out by the water gain in ITP, and the other ~40% from across the remaining basins. Monthly TWS anomalies in Central Eurasia exhibit a strong monotonic decline since 2005, despite an earlier increase linked to the rise of the Caspian Sea level21, and a water gain in ITP that persisted for multiple decades31 but has decelerated since ~201334. The TWS in the vast desert zone of Sahara/Arabia underwent a continuous decrease throughout 2002–2016, resulting in the other one-third of the net global loss (–33.10 (±3.57) Gt yr−1). A marked storage decline also prevailed in Dry Andes/Patagonia (–9.61 (±1.96) Gt yr−1), but has slowed down and partially reversed since 2012. Net water losses in Australia and Western North America are less dramatic (–4.05 (±4.86) and −2.53 (±2.00) Gt yr−1, respectively) due to spatial dipole and short-term fluctuations. For instance, Australia’s Millennium Drought35 was temporarily alleviated by La Niña-induced precipitation anomalies in the eastern region (e.g., the Great Artesian Basin) during 2010–201236. Water declines in the latter three zones sum up to another 15% of the net global endorheic loss, which is, however, counteracted by the water gain in Great Rift Valley/Southern Africa (GRVSA, 16.60 (±2.28) Gt yr−1).

Figure 3.

Endorheic TWS changes in different geographic zones. (a) Six primary zones defined as basin groups by continental and climatic similarities, where Central Eurasia further highlights four secondary zones, i.e., the Caspian Sea Basin, the Aral Sea Basin, the Inner Tibetan Plateau, and the other regions. (b) Summary of zonal TWS trends (gigatons of water loss per year and mm of equivalent SLR per year). Error bars represent 95% CIs for each TWS trend. (c–h) Monthly series of deseasonalized zonal TWS anomalies (as in Fig. 1; axis labels consistent with h).

Table 1. TWS changes and hydrological attributions in zonal and global endorheic basins from April 2002 to March 2016.

All uncertainties are 95% (2-sigma) CIs.

| Endorheic Region |

Area | Terrestrial Water Storage | Surface Water | Soil Moisture | Groundwater | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 106 km2 | Gt yr−1 | mm yr−1 SLE | Gt yr−1 | % of ΔTWS | Gt yr−1 | % of ΔTWS | Gt yr−1 | % of ΔTWS | |

| Central Eurasia | 12.69 | −73.64 (±7.74) | 0.203 (±0.021) | −35.40 (±6.19) | 48.08 (±8.40) | −23.34 (±4.91) | 31.70 (±6.67) | −14.89 (±11.06) | 20.23 (±15.01) |

| Caspian Sea | 3.17 | −40.96 (±4.66) | 0.113 (±0.013) | −28.22 (±2.62) | 68.91 (±6.39) | −17.08 (±3.36) | 41.69 (±8.21) | 4.34 (±6.31) | −10.60 (±15.41) |

| Aral Sea | 1.65 | −7.31 (±1.68) | 0.020 (±0.005) | −6.04 (±0.86) | 82.67 (±11.77) | −2.28 (±0.79) | 31.25 (±10.80) | 1.02 (±2.04) | −13.92 (±27.95) |

| Tibet | 1.06 | 5.06 (±1.04) | −0.014 (±0.003) | 4.13 (±1.27) | 81.76 (±25.04) | 0.40 (±0.58) | 7.98 (±11.45) | 0.52 (±1.74) | 10.26 (±34.37) |

| Others | 6.80 | −30.42 (±3.17) | 0.084 (±0.009) | −5.27 (±3.11) | 17.32 (±10.22) | −4.38 (±1.85) | 14.41 (±6.07) | −20.77 (±4.81) | 68.27 (±15.80) |

| Sahara/Arabia | 11.07 | −33.10 (±3.57) | 0.091 (±0.010) | 0.01 (±0.53) | −0.03 (±1.61) | 0.12 (±2.46) | −0.36 (±7.43) | −33.23 (±4.37) | 100.39 (±13.19) |

| Andes/Patagonia | 1.38 | −9.61 (±1.96) | 0.026 (±0.005) | −2.88 (±1.40) | 29.94 (±14.62) | −2.98 (±0.89) | 31.06 (±9.29) | −3.75 (±2.57) | 39.00 (±26.73) |

| Australia | 4.13 | −4.05 (±4.86) | 0.011 (±0.013) | −0.03 (±1.73) | 0.79 (±42.68) | −0.20 (±2.47) | 4.88 (±61.08) | −3.82 (±5.72) | 94.33 (±141.27) |

| North America | 1.33 | −2.53 (±2.00) | 0.007 (±0.006) | −0.43 (±0.58) | 16.82 (±23.00) | −1.32 (±0.72) | 51.99 (±28.44) | −0.79 (±2.21) | 31.19 (±87.18) |

| GRVSA | 2.07 | 16.60 (±2.28) | −0.046 (±0.006) | 0.37 (±0.60) | 2.21 (±3.60) | −0.30 (±1.33) | −1.82 (±8.01) | 16.54 (±2.70) | 99.61 (±16.28) |

| Global | 32.67 | −106.32 (±11.70) | 0.293 (±0.032) | −38.36 (±10.52) | 36.08 (±9.89) | −28.02 (±7.93) | 26.36 (±7.46) | −39.94 (±17.62) | 37.56 (±16.57) |

Contributions of different water storage components

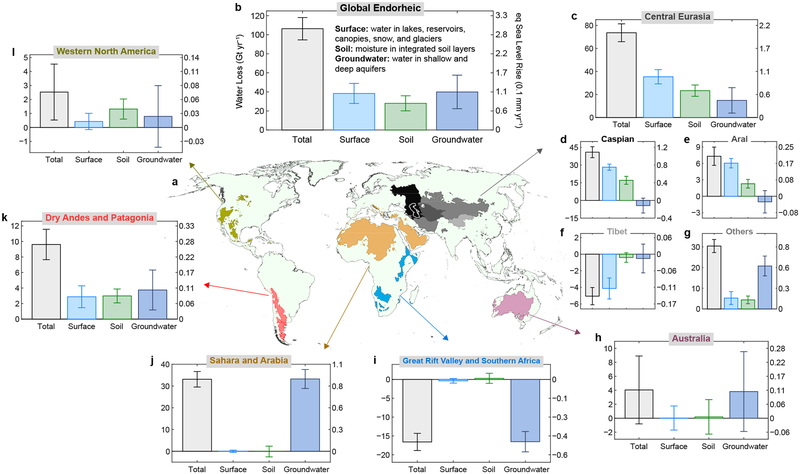

The net TWS changes aggregate the contributions of different hydrological components (Fig. 4 and Table 1). During the past 14 years, the net global endorheic loss is attributed to comparable declines in surface water (36.08% (±9.89)), soil moisture (26.36% (±7.46)), and groundwater (37.56% (±16.57)), but such contributions result from highly unequal partitions within zonal TWS changes. In Central Eurasia, surface water loss outweighs that of soil moisture and is more than double that of groundwater (Fig. 4c). The prominent surface water loss can be observed by the recent shrinkage of many large lakes across Central Asia and the Middle East (e.g., Aydar, Aral Sea, Bosten, Caspian Sea, Khyargas, Tengiz, and Urmia; Fig. S2). In particular, over 70% of the global endorheic surface water loss was induced by the level drop in the Caspian Sea (–6.8 cm yr−1). Another ~11% was caused by the desiccation of the Aral Sea (–1041.7 km2 yr−1) despite the compensation of excess discharge from warming-induced glacier melting (Fig. S5–S8 and Table S5). Surface water losses in these two basins coincided with drying climate (deficient precipitation and rising temperature, Fig. S13o–r), along with intensive water diversion (e.g., from the Volga River, Amu Darya, and Syr Darya) for irrigation, which supplemented moisture supplies for evapotranspiration17,20,37. Diversion-based irrigation may have also increased regional return flow38, resulting in possible groundwater recharge despite overall soil moisture loss (Fig. 4d–e). In contrast, increasing precipitation and, to a lesser extent, warming-induced glacier loss led to evident lake expansion in ITP9,39 (Fig. S13s–t; Table S5), where surface water surplus explains over 80% of the net TWS gain (Fig. 4f). As water relocation from glaciers to lakes does not alter the endorheic system storage, increasing net precipitation (i.e., precipitation minus evapotranspiration) is the primary contributor to the net TWS gain, which is in line with recent literature31,34,39. Surface freshwater is critically limited in the remaining endorheic zone of Central Eurasia (Fig. 4g), where groundwater withdrawal easily exceeds natural recharge12. Similar to river diversion, groundwater depletion might enhance evaporation by cumulatively transferring water from aquifers to the surface, which explains 68% of the zonal TWS loss.

Figure 4.

Endorheic net TWS changes partitioned into contributions of different hydrological storages. (a) As in Fig. 3a. (b) The global total of endorheic storage change and attributions to surface water, soil moisture, and groundwater (gigatons of water loss per year and mm of equivalent SLR per year). (c–l) Zonal net storage changes and different storage contributions (axis labels as in b). Error bars represent 95% CIs. Bar colors for different water storages follow the convention for blue (surface water and groundwater) and green (soil moisture) water resources.

Greater dominance of groundwater depletion to net TWS loss is seen in Australia (Fig. 4h) and Sahara/Arabia (Fig. 4j), where endorheic basins often remain arheic and groundwater becomes the only permanent water source. In Sahara/Arabia, for instance, annual groundwater depletion (–33.23 (±4.37) Gt yr−1) matches the rate of the zonal TWS loss. Our estimate is similar to that of Richey et al.7 (about −29 (±6) Gt yr−1 during 2003–2013) if one sums up their estimated depletions of major aquifers including Arabian, Nubian, Northwestern Sahara, Murzuk-Djado Basin, Taoudeni-Tanezrouft Basin, and Lake Chad Basin, although these authors did not correct modeled surface anomalies by lake storage changes (e.g., minor increase in Lake Chad). In addition to unsustainable human withdrawal, groundwater declines in these desert zones may result from vadose capillary fluxes that transport water from aquifers to compensate for soil moisture loss40. Such declines are in sharp contrast to the groundwater gain in GRVSA (16.54 (±2.70) Gt yr−1; Fig. 4i), indicating persistent recharge as a result of excess precipitation (Fig. S13i–j).

In Western North America, climate-induced soil moisture decrease (Fig. S13c–d) dominates the net TWS loss (Fig. 4l). Meanwhile, studies8,33,41 suggest that human activities, such as irrigation and mining, are crucial causes of the surface water decline in Great Salt Lake (–0.20 Gt yr−1, consistent with −0.17 Gt yr−1 in Wurtsbaugh et al8) and Salton Sea41 (–0.11 Gt yr−1) (Fig. S2), accounting for 12% of the zonal TWS loss. The contribution is more evenly partitioned among surface, soil, and aquifers in Dry Andes/Patagonia (Fig. 4k), where a quarter of the net TWS loss stems from the shrinkage of Lakes Titicaca, Poopό, and Mar Chiquita (Fig. S2). Such concurrent losses in multiple water stores imply an extensive impact of the recent precipitation deficit (Fig. S13e–f) and human activities on South America’s endorheic hydrology8,42,43.

Implications for global water cycle

Our findings reveal the recent decadal TWS decline in global endorheic basins, which largely outpaces the concurrent TWS change in the exorheic region. While exorheic TWS modulates the sea level by directly affecting surface runoff to the ocean, it is also subject to natural variability of the climate system (e.g., ENSO at multiyear timescales) that augments/suppresses the delivery of water from the ocean4,14. From another perspective, we show that endorheic TWS, albeit limited in quantity, can dominate the variation in global TWS at decadal timescales. This decadal loss in endorheic TWS suggests that recent climate conditions, in conjunction with direct human activities, resulted in a substantial vapor outflow from the continental interiors. The consequential water surplus to the exorheic system might be acting as a non-negligible source of SLR. Limited by available TWS observations, our calculated trend may not imply a secular signal beyond the studied GRACE era. Nevertheless, this decadal endorheic loss is in line with satellite-observed decreases in surface water extent since ~19809,33, model-simulated increases in water stress over the past half century44,45, and reported declines in water volumes of major saline lakes over the past ~140 years8, all predominantly in arid/semi-arid regions. Under the latest climate change scenarios, reversal of such a net decline in the next half/one century seems uncertain, considering projected decreases in precipitation, soil moisture, and discharge but increases in potential evaporation, drought duration, and water stress in many endorheic regions3,5,46–50.

Apart from a widespread net TWS loss, we quantify that the loss prevails comparatively in all three primary hydrological stores (surface, soil, and aquifers). However, their relative contributions vary among endorheic zones, resulting from strong spatial heterogeneity in flux-storage interactions and responses to climate and water management. As detailed in Methods and Supplementary Information, our partitioning of TWS losses relies on a synergy of multi-model ensemble and satellite observations, and emphasizes different components in the water cycle rather than attributions to natural variability versus secular forces. Despite uncertainties, our analysis exemplifies a critical effort toward the decoupling of climate-human influences on the recent TWS shift from endorheic to exorheic systems. This analytical decoupling is essential for projecting and managing water stress in arid/semiarid regions under future climate change. Given such dual ramifications both to regional water sustainability and to global SLR, we thereby suggest a continued understanding of long-term TWS variation in global endorheic basins, and an explicit inclusion of its net contribution (such as by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) in future sea level budgeting.

Methods

Defining endorheic regions.

Endorheic basin extents are mainly acquired from a total of 48,813 landlocked watersheds identified in the 15-second HydroSHEDS drainage basin dataset51 (Fig. S14a). Their spatial patterns are overall consistent with the depiction in the Global Drainage Basin Database52 (GDBD). Among minor discrepancies, 10 watersheds landlocked in ITP, Manchuria, Siberia, and western US are captured only in GDBD (Fig. S14a), and thus included to supplement HydroSHEDS. These watersheds are aggregated into three enumeration scales: (i) 173 endorheic units (Fig. 1a), each comparable to or larger than the size of a 3-degree spherical cap mascon (~100 thousand km2), (ii) 10 endorheic zones (Fig. 3a), including 6 primary zones in the continental level and 4 secondary zones within Central Eurasia, and (iii) the entire global endorheic system, i.e., the aggregated extent of all landlocked basins. Each endorheic unit, as further illustrated in Fig. S14b, is a single landlocked watershed if its size exceeds a mascon, or an agglomeration of contiguous/nearby watersheds until their total area exceeds a mascon. These units exclude sporadic landlocked watersheds smaller than a mascon and substantially detached from major endorheic clusters (black areas in Fig. 1a). The secondary zones of the Caspian Sea Basin and the Aral Sea Basin (Fig. 3a) include several surrounding endorheic watersheds to compensate for the GRACE signal leakage from the Caspian Sea and the Aral Sea. The Aral Sea Basin also integrates nearby endorheic watersheds receiving transbasin diversions from the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya.

Calculating endorheic TWS changes.

GRACE-observed monthly anomalies of equivalent water thickness (EWT) from April 2002 to March 2016 in the JPL 3-degree equal-area mason solution (JPL-RL05M version 2)26,27,53,54 are rescaled to each enumeration level (unit, zonal, and global) by an area-weighted scaling: , where M denotes a monthly anomaly for any enumeration region, mi the original anomaly in each mascon i that intersects with this region, and ai the intersection area. Deseasonalized time series M (with monthly climatology removed) is used to calculate the TWS trend by best-fit linear regression. The RL05M solution provides 0.5-degree gain factors simulated by the Community Land Model27. However, this model lacks surface water (SW) compartments (e.g., lakes and glaciers) and human processes, and the least-squares correction in the factor derivation tends to be dominated by the annual cycles of land water storage variations. Despite a partial recovery of the signal variation, the gain factors may not be suitable for calculating TWS trends at sub-mascon resolution. For these reasons, they are not applied in our rescaling process. Instead, rescaling-induced uncertainties are accounted for in our estimated zonal and global trends.

Specifically, uncertainties (eM) of monthly M in each enumeration region are propagated from the inherent errors (eM) associated with original mascon data and the rescaling uncertainties (er) induced by signal leakage in fringe mascons. Similar to M, a monthly em is calculated as , where ei denotes the provided data uncertainty for each mascon i that intersects with this region. To infer er, we compute the intersection area (ai) as a proportion (P) of each mascon (Fig. S15). A fringe mascon is indicated by a value of P between 0 and 1 (hereafter “internal fringe portion”). For each month, we first calculate the average EWT anomaly in the mascons enclosed by this region (i.e., P = 1). This assesses the signal in the region interior exclusive of external leakage impacts, despite a sacrifice of the signal in the internal fringe portion. We then lower the threshold (t) of P by a step of 0.05, and calculate the average anomaly (Mt) in the full mascons with P ≥ t, until t = 0 (i.e., all fringe mascons included). In this way, Mt gradually picks up the missing signal within this endorheic region as the internal fringe portion decreases. Meanwhile, it absorbs increasing signal leakage as the external fringe portion expands. The variance of Mt, therefore, reflects the uncertainty of signal scaling at sub-mascon resolution. Given this logic, the standard deviation in the array of Mt (Fig. S16) is used as a measure of this monthly er. Time series eM and the variation of residuals from the trend fitting are then propagated to infer a 95% CI of the TWS trend using a Monte Carlo method as in Wang et al55.

To further evaluate our estimated TWS changes, we determine how the EWT trend in each region changes from its endorheic interior to periphery. This is done by calculating the linear trend in monthly Mt with a gradually lowered t, as shown in Fig. S17 (blue profiles). For a region under a net TWS decline, a rising profile implies that the rate of water loss tends to weaken as one moves away from the endorheic interior. If we assume that this pattern is also true at sub-mascon scales, the magnitude of EWT decline in the internal portion of a fringe mascon would be greater than that in the external portion. Our signal scaling based on simple area partitioning of the fringe mascons thus underrates the actual water loss in the peripheral endorheic areas (where signals of weaker decline leak into the internal portions), leading to an overall conservative TWS trend for this enumeration region. This case applies to the entire endorheic system and most zones that experienced TWS declines. The exception in Dry Andes/Patagonia (Fig. S17c) is likely attributed to the complex endorheic boundary (Fig. S15a) and the leakage of stronger EWT declines from the exorheic Andes. In the Aral Sea Basin, fully enclosed mascons are found in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya regions (Fig. S15c) but the most significant water loss occurred in the Aral Sea. This explains the weak initial decline (when P = 1 in Fig. S17i) in this region. As P continues to decrease, the EWT trends are overall stable (black profile) despite increasing leakage of water loss in the nearby Caspian Sea (blue profile). Similarly, a decreasing profile for any region under a net TWS gain implies that our estimated TWS increase is likely underrated. This is seen in the GRVSA (Fig. S17e) and ITP (Fig. S17j). However, since their total water gain accounts for a marginal proportion (~17%) of the total water loss in the other regions, our reported net TWS decline in global endorheic basins is overall conservative (Fig. S17a).

Although our results do not apply the mascon-set of 0.5-degree gain factors, their impact is assessed by comparing EWT trends calculated with versus without the gain factors for each endorheic zone (black and red profiles in Fig. S17). Because the inclusion of gain factors only affects signal rescaling at sub-mascon resolution, the EWT trends at each t are calculated from the average anomalies within the intersected or internal mason portions (where P ≥ t). The profiles illustrate how EWT trends between the two solutions (with and without gain factors) increasingly differ as more incomplete mascons are included in rescaling. The two solution profiles appear highly consistent in each zone, and their divergence is enclosed by the 95% CIs induced by the inherent mascon data errors (transparent shades). Therefore, including the gain factors will make no significant difference to the estimation of global/zonal TWS trends.

Estimating lake storage changes.

We calculate storage changes in 142 large waterbodies (a total area of ~540k km2; Figs. S1–S2) that account for ~75% of the lakes/reservoirs in area and ~98% in volume across endorheic basins56,57. Level time series during our study period are collected from multi-mission altimeter observations (e.g., Envisat, Jason, TOPEX/Poseidon, and SARAL/AltiKa), as archived in the Database for Hydrological Time Series of Inland Water (DAHITI)58 (https://dahiti.dgfi.tum.de/en), the Hydroweb59 (http://hydroweb.theia-land.fr), and the USDA G-REALM (www.pecad.fas.usda.gov/cropexplorer/global_reservoir). Hypsometry is considered for 38 (87% in area) of the 142 lakes, where level-area functions for 8 largest lakes (79%) are calibrated in this study using time-variable inundation areas mapped from MODIS imagery (250-m MOD09Q1) (Figs. S3–S10), and level-area functions for the other 30 lakes (8%) are retrieved from the Hydroweb. For each of these 38 lakes, time series volume anomalies are calculated as the integrals of the hypsometric function from the average water level, and the mean volume seasonality is further removed for linear trend fitting. Volume anomalies in each of the remaining 104 lakes (13%) are approximated by water level time series that are assumed to vary with a static inundation area mapped from Landsat imagery acquired during 2008–2009 (representing the middle-stage extent during our study period) using methods in Sheng et al57.

Multiple error sources are identified to propagate the uncertainties of lake volume anomalies, which are used to infer 95% CIs for lake storage trends by the Monte Carlo method55 (as for TWS trends). For the 8 lakes with calibrated hypsometry, error sources include (i) level uncertainties provided in the altimetric data, (ii) mapping errors for inundation area, estimated from a relative bias of 5% in MODIS-based large waterbody extraction60, and (iii) uncertainties in calibrated hypsometry, calculated as the RMSE of fitted level-area functions (Figs. S3–S10). For each of the remaining 134 lakes, the trend CI is propagated from source (i), and another error term that attempts to reflect the overall uncertainty due to unknown fitting errors in the hypsometry retrieved from Hydroweb (for the 30 lakes), the ignored lake area variation (for the other 104 lakes), and gaps in the acquired level time series. We quantify this error term to be 14% (95% CI) of each lake storage trend, inferred from the 8 lakes where storage trends estimated using Hydroweb hypsometry or only water levels are validated against the estimates using our calibrated hypsometry. For the other smaller waterbodies where storage changes are unquantified in our study, we consider that they in total generate a 95% uncertainty of 10 Gt yr−1. If assuming lake volume change is proportional to lake area (akin to a simple bucket model where water budget variations reflect precipitation-evaporation residuals multiplied by the bucket cap size), we have one third of the net annual water loss in our studied 142 lakes to be ~10 Gt yr−1. This uncertainty is partitioned to different endorheic zones by their total small waterbody areas.

Estimating glacier mass changes.

Changes in glacier mass balance are estimated for three secondary zones in Central Eurasia (ITP, the Aral Sea Basin, and Others; Fig. 4a) that contain ~98% of the total glacier extent in global endorheic basins (Fig. S11). Our estimations are based on the 30-m gridded dataset of glacier surface elevation changes (thereafter dh/dt) from 2000 to 2016 in High Mountain Asia (HMA)11. The rates of dh/dt are derived by fitting a linear regression through time series of co-registered digital elevation models (DEMs) constructed from ASTER stereo images during 2000–2016. Details are given in Brun et al.11.

We obtain 132 dh/dt maps (in 1° grid with estimation uncertainties) covering the endorheic HMA. Pixels over non-glacierized regions are masked by the Randolph Glacier Inventory 6.061. Over the glacierized regions, pixels with absolute dh/dt rates above 50 m yr−1 are excluded as noise. Similar to Brun et al.11, Gardelle et al.62 and Neckel et al.63, glacier-hypsometry-averages are used to represent the average dh/dt for region-wide units. To reduce the uncertainty due to spatial heterogeneity of glacier changes, we divide the glacierized areas into several sub-regions11,64 including northwestern ITP, southern ITP, Qilian Mountains, Kunlun Mountains within the Tarim Basin, southern Tian Shan, northern Tian Shan, the Pamirs, and the remaining areas. Glacierized areas in each sub-region are considered as one virtual contiguous ice body, where glacier hypsometry is calculated using 100-m elevation bands discretized by the ALOS World 3D-30m DEM65. For each elevation band, dh/dt pixel values are filtered to the level of three normalized absolute deviations relative to the median of the elevation band11. Filtered dh/dt values are averaged for each elevation band, and the rate of volume change is calculated as the sum of the mean dh/dt multiplied by the glacier area in this band. The volume change is converted to mass change assuming a conversion factor of 850 (±60) kg m−3 66 and a negligible difference between the rates in 2000–2016 and 2002–2016. Glacier mass change rates for different elevation bands are then subtotaled to secondary endorheic zones (Table S2).

Besides the above-mentioned secondary zones in Central Eurasia, small clusters of glaciers scattered in the Caspian Sea Basin (726 km2 or 0.02% of the zonal area), Dry Andes/Patagonia (438 km2 or 0.03%), and Western North America (17 km2 or <0.01%) (Fig. S11; Table S3). By referring to previous studies of glacier changes around these zones64,67,68, glacier mass changes may only account for miniscule portions of the zonal TWS declines (Table S3, where glacial changes are largely under the TWS change uncertainties). For this reason, glacier mass changes in these zones are not explicitly quantified, and instead considered as modeled SWE variations over their glacierized regions.

Partitioning net TWS changes.

We partition GRACE-observed net TWS changes to SW, soil moisture (SM), and groundwater contributions through a comprehensive synergy of model simulations and satellite observations. Considering that some of the frequently used large-scale hydrological models lack SW and groundwater compartments69, we rely on hydrological models only for simulating monthly anomalies in SM, snow water equivalent (SWE), and canopy water (CW). Storage trends in major waterbodies and GIC are derived from multi-mission satellite measurements (see previous sections), and then combined with modeled SWE and CW trends to calculate the net SW change (Table S5). Eventually, the groundwater contribution is separated as the residual between GRACE-observed TWS change and the estimated SW and SM changes.

Similar to some existing studies69,70, we consider two widely-applied global hydrological models (WGHM71,72 and PCR-GLOBWB73) and five land surface models (LSMs) from the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS)74 (CLM, Mosaic, Noah, VIC, and CLSM) to simulate monthly changes in SWE, CW, and SM during 2002–2016 (see Table S1 for model descriptions). To account for model discrepancies induced by different climate forcing and parameterizations, we follow a typical ensemble approach, where deseasonalized multi-model time series are averaged to represent monthly anomalies and standard deviations among the model time series as ensemble uncertainties. Because the available modeling period for CLSM and PCR-GLOBWB discontinues after 2014, their time series are not included in the calculation of ensemble means. Instead, we compare their time series with the ensemble means from the other five models during 2002–2014, and use the monthly differences to further expand the ensemble uncertainties.

Several studies noticed that the amplitude of SM variation from WGHM is substantially lower than those of other models75,76, which is also seen in our studied endorheic basins (Fig. S18). To avoid possible biases in trend calculation, WGHM is excluded from the ensemble of SM anomalies, but is used to infer additional ensemble uncertainties together with CLSM and PCR-GLOBWB. We also assume that the during the studied GRACE era, direct irrigation impacts on SM were regional and limited to seasonal timescales, and did not considerably alter the interannual SM trends at zonal/global scales (also see Supplementary Information). Our modeled SM anomalies are validated against in situ measurements from the Soil Climate Analysis Network (SCAN; www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/scan) in endorheic North America (Fig. S19). For most SCAN stations, deseasonalized SM time series from measurements and models show significant correlations, and the discrepancies between their interannual trends are within the 95% CIs. Detailed validations are provided in Supplementary text, Fig. S20, and Table S6.

As previously described, our glacier mass changes are based on detected elevation changes from stereo-correlated time series DEMs11. These changes include the contributions of both alpine glaciers and snowpack. To avoid double-counting, we replace modeled SWE over glacierized endorheic HMA by satellite-observed glacier mass changes. This replacement also minimizes the influence of modeled SWE errors that are often amplified in alpine environments77,78. To further validate modeled SWE changes in other regions, we select endorheic North America with high-quality SWE estimates from the Snow Data Assimilation (SNODAS) program79 (Supplementary text). The time series of modeled and SNODAS anomalies show evident differences in magnitude, but agree fairly well in interannual trend (with a discrepancy insignificant to the CIs; Fig. S21). Although this validation is limited in North America, the amount of water stored in snowpack and canopies in endorheic basins is relatively small. This is reflected by the combined loss of SWE and CW (3.64 (±1.90) Gt yr−1), contributing <4% of the global endorheic TWS loss (Table S5). Thus the influence of their modeling uncertainties on our TWS partitioning is likely miniscule.

Assessing TWS responses to climate forcing.

Climate impacts on TWS changes are assessed by exploring (i) the correlations between annual net TWS changes and total precipitation and (ii) the trends in monthly temperature anomalies, for the global endorheic system and each endorheic zone (Fig. S13). We emphasize TWS changes in response to precipitation on an annual basis, in order to remove the influence of correlations dominated by seasonal variation. We calculate temperature trends to assess recent warming in endorheic regions and facilitate the discussion of warming-induced glacier retreat and possible enhancement of potential evapotranspiration. It is worth noting that evapotranspiration responds to radiative and aerodynamic variables in addition to temperature80, so we do not claim that warming alone necessarily caused the observed TWS loss. However, since existing evapotranspiration data do not adequately account for the impact of open surface water, the response of TWS changes to actual evapotranspiration is not explored.

To account for uncertainties in climate variables, we retrieve the monthly means of precipitation and temperature anomalies during 2002–2016 from multiple observation/assimilation sources. Sources of precipitation data include the CPC Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP)81 (www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.cmap.html), the Global Precipitation Climatology Center (GPCC) precipitation82 (total full v7; www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.gpcc.html), the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP)83 (www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html), and the PRECipitation REConstruction over Land (PREC/L)84 (www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.precl.html). As merged analysis and reanalysis precipitation data tend to show evident uncertainties over ITP85, its precipitations are acquired from a 0.25° gridded observation dataset85–87 provided by the National Climate Center of China Meteorological Administration. Sources of temperature data include the NOAA Global Surface Temperature88,89 (www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.noaaglobaltemp.html), the Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature90 (http://berkeleyearth.org/data), and mean surface air temperature from the GLDAS LSMs.

Data availability.

Calculated water storage changes in global endorheic regions are distributed through PANGAEA (doi: in process). Storage changes in major lakes and reservoirs are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (JW). Glacier mass change data are available through Nature Geoscience article doi:10.1038/NGEO2999.

Code availability.

All analytical codes generated in this paper are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Kansas State University faculty start-up fund to JW, NASA Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) Grant (#NNX16AH85G) to YS, and China’s Thousand Young Talents Program (#Y7QR011001) to CS. This work was funded in part by the NASA Sea Level Change team. A portion for this research was conducted at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with NASA. Assistance of endorheic basin aggregation and lake mapping was provided by Meng Ding, Takuto Urano, and Colin Bailey (Kansas State University). We thank Etienne Berthier (OMP/LEGOS) for support in providing glacier mass change data and comments on the manuscript, and Linghong Ke, Hang Pan, and Shengan Zhan (UCLA) for helping collect meteorological and altimetry data. Constructive suggestions were provided by Kehan Yang (University of Colorado Boulder) on snow water equivalent validation, Qian Cao (UCLA) on soil moisture validation, Martin Ménégoz (Barcelona Supercomputing Center) on climate variability, and Jordan M. McAlister (Oklahoma State University) on scientific implications and writing.

Footnotes

Financial and non-financial competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Wada Y et al. Global monthly water stress: 2. Water demand and severity of water stress. Water Resour. Res 47, W07518 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer UT Saline Lake Ecosystems of the World. (Dr W. Junk Publishers, Dordrcht, The Netherlands, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai AG Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 52–58 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reager JT et al. A decade of sea level rise slowed by climate-driven hydrology. Science 351, 699–703 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodell M, et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availabiltiy. Nature 557, 651–659 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wada Y, van Beek LPH, Wanders N & Bierkens MFP Human water consumption intensifies hydrological drought worldwide. Environ. Res. Lett 8, 034036 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richey AS et al. Quantifying renewable groundwater stress with GRACE. Water Resour. Res 51, 5217–5238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wurtsbaugh WA et al. Decline of the world’s saline lakes. Nat. Geosci 10, 816–821 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pekel JF, Cottam A, Gorelick N & Belward AS High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540, 418–422 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob T, Wahr J, Pfeffer WT & Swenson S Recent contributions of glaciers and ice caps to sea level rise. Nature 482, 514–518 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brun F, Berthier E, Wagnon P, Kääb A & Treichler D A spatially resolved estimate of High Mountain Asia glacier mass balances from 2000 to 2016. Nat. Geosci 10, 668–673 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleeson T, Wada Y, Bierkens MFP & van Beek LPH Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint. Nature 488, 197–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Church JA & White NJ Sea-level rise from the late 19th to the early 21st century. Surv. Geophys 32, 585–602 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cazenave A et al. The rate of sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 358–361 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dieng HB, Cazenave A, Meyssignac B & Ablain M New estimate of the current rate of sea level rise from a sea level budget approach. Geophys. Res. Lett 44, 3744–3751 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centre national d’études spatiales (CNES). Mean sea level product and image interactive selection. Archiving, Validation and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic (AVISO) data, https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/products/ocean-indicators-products/mean-sea-level/products-images.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahagian DL, Schwartz FW & Jacobs DK Direct Anthropogenic Contributions to Sea-Level Rise in the 20th-Century. Nature 367, 54–57 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vörösmarty CJ & Sahagian D Anthropogenic disturbance of the terrestrial water cycle. Bioscience 50, 753–765 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milly PCD et al. in Understanding Sea-Level Rise and Variability (Church JA et al. ed.) 226–255 (Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, UK, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pokhrel YN et al. Model estimates of sea-level change due to anthropogenic impacts on terrestrial water storage. Nat. Geosci 5, 389–392 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada Y et al. Recent Changes in Land Water Storage and its Contribution to Sea Level Variations. Surv. Geophys 38, 131–152 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beni AN et al. Caspian sea-level changes during the last millennium: historical and geological evidence from the south Caspian Sea. Clim. Past 9, 1645–1665 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahagian D Global physical effects of anthropogenic hydrological alterations: sea level and water redistribution. Global Planet. Change 25, 39–48 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Famiglietti JS Remote sensing of terrestrial water storage, soil moisture and surface waters. Geophys. Monogr. Ser 19, 197–207 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapley BD, Bettadpur S, Ries JC, Thompson PF & Watkins MM GRACE measurements of mass variability in the Earth system. Science 305, 503–505 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowlands DD et al. Resolving mass flux at high spatial and temporal resolutio using GRACE intersatellite measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett 32, L04310 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watkins MM, Wiese DN, Yuan DN, Boening C & Landerer FW Improved methods for observing Earth’s time variable mass distribution with GRACE using spherical cap mascons. J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea 120, 2648–2671 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolter K & Timlin MS Monitoring ENSO in COADS with a seasonally adjusted principal component index In Proceedings of the 17th Climate Diagnostics Workshop, Norman, OK, NOAA/NMC/CAC, NSSL, Oklahoma Clim. Survey, CIMMS and the School of Meteor., Univ. of Oklahoma, 52–57 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolter K & Timlin MS Measuring the strength of ENSOevents – how does 1997/98 rank? Weather 53, 315–324 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada Y et al. Fate of water pumped from underground and contributions to sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 777–780 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang GQ et al. Lake volume and groundwater storage variations in Tibetan Plateau’s endorheic basins. Geophys. Res. Lett 44, 5550–5560 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oki T & Kanae S Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou Z et al. Divergent trends of open-surface water body area in the contiguous United States from 1984 to 2016. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, doi:10.1073/pnas.1719275115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao F et al. Lake storage variation on the endorheic Tibetan Plateau and its attribution to climate change since the new millennium. Environ. Res. Lett 13, 064011 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Dijk AIJM et al. The Millennium Drought in southeast Australia (2001–2009): Natural and human causes and implications for water resources, ecosystems, economy, and society. Water Resour. Res 49, 1040–1057 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fasullo JT, Boening C, Landerer FW & Nerem RS Australia’s unique influence on global sea level in 2010–2011. Geophys. Res. Lett 40, 4368–4373 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozyavas A, Khan SD & Casey JF A possible connection of Caspian Sea level fluctuations with meteorological factors and seismicity. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett 299, 150–158 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor RG et al. Ground water and climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 322–329 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song CQ, Huang B, Richards K, Ke LH & Phan VH Accelerated lake expansion on the Tibetan Plateau in the 2000s: Induced by glacial melting or other processes? Water Resour. Res 50, 3170–3186 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walvoord MA, Phillips FM, Tyler SW & Hartsough PC Deep arid system hydrodynamics - 2. Application to paleohydrologic reconstruction using vadose zone profiles from the northern Mojave Desert. Water Resour. Res 38, 1291 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnum DA, Bradley T, Cohen M, Wilcox B & Yanega G State of the Salton Sea: A science and monitoring meeting of scientists for the Salton Sea. US Department of the Interior and US Geological Survey Open-file report 2017–1005 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Revollo MM Management issues in the Lake Titicaca and Lake Poopo system: Importance of developing a water budget. Lakes Reserv. Res. Manag 6, 225–229 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calizaya A, Meixner O, Bengtsson L & Berndtsson R Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) for integrated water resources management (IWRM) in the Lake Poopo Basin, Bolivia. Water Res. Manag 24, 2267–2289 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai A, Qian TT, Trenberth KE & Milliman JD Changes in Continental Freshwater Discharge from 1948 to 2004. J. Climate 22, 2773–2792 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wada Y, van Beek LPH & Bierkens MFP Modelling global water stress of the recent past: on the relative importance of trends in water demand and climate variability. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc 15, 3785–3808 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen JL et al. Long-term Caspian Sea level change. Geophys. Res. Lett 44, 6993–7001 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook BI, Smerdon JE, Seager R & Coats S Global warming and 21st century drying. Clim. Dynam 43, 2607–2627 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haddeland I et al. Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3251–3256 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prudhomme C et al. Hydrological droughts in the 21st century, hotspots and uncertainties from a global multimodel ensemble experiment. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3262–3267 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schewe J et al. Multimodel assessment of water scarcity under climate change. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3245–3250 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lehner B, Verdin K & Jarvis A New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Eos, Trans. Amer. Geophys. Union 89, 93–94 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masutomi Y, Inui Y, Takahashi K & Matsuoka Y Development of highly accurate global polygonal drainage basin data. Hydrol. Processes 23, 572–584 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiese DN JPL GRACE Mascon Ocean, Ice, and Hydrology Equivalent Water Height JPL RL05M.1. Ver. 1. Physical Oceanography Distributed Active Archive Center (PODAAC), California, USA, doi:10.5067/TEMSC-OCL05 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiese DN, Landerer FW & Watkins MM Quantifying and reducing leakage errors in the JPL RL05M GRACE mascon solution. Water Resour. Res 52, 7490–7502 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Sheng Y & Wada Y Little impact of the Three Gorges Dam on recent decadal lake decline across China’s Yangtze Plain. Water Resour. Res 53, 3854–3877 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Messager ML, Lehner B, Grill G, Nedeva I & Schmitt O Estimating the volume and age of water stored in global lakes using a geo-statistical approach. Nat. Commun 7, 13603 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheng Y et al. Representative lake water extent mapping at continental scales using multi-temporal Landsat-8 imagery. Remote Sens. Environ 185, 129–141 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwatke C, Dettmering D, Bosch W & Seitz F DAHITI - an innovative approach for estimating water level time series over inland waters using multi-mission satellite altimetry. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc 19, 4345–4364 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crétaux JF et al. SOLS: A lake database to monitor in the Near Real Time water level and storage variations from remote sensing data. Adv. Space Res 47, 1497–1507 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, Sheng Y & Tong TSD Monitoring decadal lake dynamics across the Yangtze Basin downstream of Three Gorges Dam. Remote Sens. Environ 152, 251–269 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Consortium RGI. Randolph Glacier Inventory – A Dataset of Global Glacier Outlines: Version 6.0: Technical Report (Global Land Ice Measurements from Space, Boulder, Colorado, USA, 2017) doi:10.7265/N5-RGI-60. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gardelle J, Berthier E, Arnaud Y & Kääb A Region-wide glacier mass balances over the Pamir-Karakoram-Himalaya during 1999–2011. Cryosphere 7, 1263–1286 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neckel N, Loibl D & Rankl M Recent slowdown and thinning of debris-covered glaciers in south-eastern Tibet. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett 464, 95–102 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gardner AS et al. A reconciled estimate of glacier contributions to sea level rise: 2003 to 2009. Science 340, 852–857 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tadono T et al. Precise global DEM generation by ALOS PRISM. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2, 71–76 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huss M Density assumptions for converting geodetic glacier volume change to mass change. Cryosphere 7, 877–887 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Falaschi D et al. Mass changes of alpine glaciers at the eastern margin of the Northern and Southern Patagonian Icefields between 2000 and 2012. J. Glaciol 63, 258–272 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mernild SH, Liston GE, Hiemstra C & Wilson R The Andes Cordillera. Part III: glacier surface mass balance and contribution to sea level rise (1979–2014). Int. J. Climatol 37, 3154–3174 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scanlon BR et al. Global models underestimate large decadal declining and rising water storage trends relative to GRACE satellite data. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, doi:10.1073/pnas.1704665115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Long D et al. Global analysis of spatiotemporal variability in merged total water storage changes using multiple GRACE products and global hydrological models. Remote Sens. Environ 192, 198–216 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Döll P, Kaspar F & Lehner B A global hydrological model for deriving water availability indicators: model tuning and validation. J. Hydrol 270, 105–134 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Müller Schmied H et al. Sensitivity of simulated global-scale freshwater fluxes and storages to input data, hydrological model structure, human water use and calibration. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc 18, 3511–3538 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wada Y & Bierkens MFP Sustainability of global water use: past reconstruction and future projections. Environ. Res. Lett 9, 104003 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodell M et al. The global land data assimilation system. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc 85, 381–394 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khandu, Forootan, Schumacher M, Awange JL & Müller Schmied H Exploring the influence of precipitation extremes and human water use on total water storage (TWS) changes in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna River Basin. Water Resour. Res 52, 2240–2258 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tangdamrongsub N et al. Evaluation of groundwater storage variations estimated from GRACE data assimilation and state-of-the-art land surface models in Australia and the North China Plain. Remote Sens. 10, 483 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Margulis SA, Cortes G, Girotto M & Durand M A Landsat-Era Sierra Nevada Snow Reanalysis (1985–2015). J. Hydrometeorol 17, 1203–1221 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wrzesien ML et al. Comparison of methods to estimate snow water equivalent at the mountain range scale: a case study of the California Sierra Nevada. J. Hydrometeorol 18, 1101–1119 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 79.National Operational Hydrologic Remote Sensing Center. Snow Data Assimilation System (SNODAS) Data Products at NSIDC, Version 1. National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Boulder, Colorado USA, doi:10.7265/N5TB14TC (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sheffield J, Wood EF & Roderick ML Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 491, 435–438 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xie PP & Arkin PA Global precipitation: A 17-year monthly analysis based on gauge observations, satellite estimates, and numerical model outputs. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc 78, 2539–2558 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schneider U et al. GPCC Full data reanalysis version 6.0 at 0.5: monthly land-surface precipitation from rain-gauges built on GTS-based and historic data. NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division (ESRL PSD), doi:10.5676/DWD_GPCC/FD_M_V7_050 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Adler RF et al. The version-2 global precipitation climatology project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979-present). J. Hydrometeorol 4, 1147–1167 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen MY, Xie PP, Janowiak JE & Arkin PA Global land precipitation: A 50-yr monthly analysis based on gauge observations. J. Hydrometeorol 3, 249–266 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 85.You QL, Min JZ, Zhang W, Pepin N & Kang SC Comparison of multiple datasets with gridded precipitation observations over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dynam 45, 791–806 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 86.New M, Lister D, Hulme M & Makin I A high-resolution data set of surface climate over global land areas. Climate Res. 21, 1–25 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu J & Gao XJ A gridded daily observation dataset over China region and comparison with the other datasets. Chinese J. Geophys.-Ch 56, 1102–1111 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith TM, Reynolds RW, Peterson TC & Lawrimore J Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880–2006). J. Climate 21, 2283–2296 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vose RS et al. Noaa’s Merged Land-Ocean Surface Temperature Analysis. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc 93, 1677–1685 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rohde R et al. A new estimate of the average earth surface land temperature spanning 1753 to 2011. Geoinfor. Geostat.: An Overview 1, doi:10.4172/2327-4581.1000101 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Calculated water storage changes in global endorheic regions are distributed through PANGAEA (doi: in process). Storage changes in major lakes and reservoirs are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (JW). Glacier mass change data are available through Nature Geoscience article doi:10.1038/NGEO2999.