Abstract

In this review, a brief history and current state-of-the-art is given to stimulate the rational design of new microbubbles through the reverse engineering of current ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs). It is shown that an effective microbubble should be biocompatible, echogenic and stable. Physical mechanisms and engineering calculations have been provided to illustrate these properties and how they can be achieved. The rational design paradigm is applied to study current FDA-approved and commercially available UCAs. Given the sophistication of microbubble designs reported in the literature, rapid development and adoption of ultrasound device hardware and the growing number of revolutionary biomedical applications moving toward the clinic, the field of Microbubble Engineering is fertile for breakthroughs in next- generation UCA technology. It is up to current and future microbubble engineers and clinicians to push forward with regulatory approval and clinical adoption of advanced UCA technologies in the years to come.

Keywords: microbubble, coalescence, surface forces, dissolution, imaging, drug delivery

A brief history

The field of ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs) was born in the late 1960’s with the observation by Gramiak and Shah of enhanced ultrasound signals from the aortic valve after the injection of dyes [1]. They determined that bubbles formed by agitation of the dye solution were responsible for enhancing the ultrasound echoes. This important discovery opened the possibility of improving the ultrasound scattering contrast between blood and tissue to image cardiac and vascular structures. Research on injectable microbubbles progressed over the ensuing years, and the first UCA for echocardiography was approved in the 1990’s for clinical use. First-generation UCAs comprised an albumin shell and air core (Albunex). These microbubbles were sufficiently stable and small (<10 μm diameter) to pass through the lung capillaries to the left ventricle [2]. Second-generation microbubbles comprising perfuoropropane gas (Optison) significantly extended contrast signal duration [3]. Shortly thereafter, lipid-coated microbubbles were developed and approved for echocardiography and radiology [4,5]. Currently, clinical and research studies employ lipid-coated microbubbles more than any other formulation.

Early on, microbubbles were conjugated to targeting ligands for ultrasound molecular imaging [6]. At the same time, the remarkably strong response of microbubbles to ultrasound inspired studies examining in vitro sonoporation and in vivo drug delivery, in which microbubble cavitation induces pore formation in the cellular plasma membrane and vascular endothelium, respectively [7]. Parallel research investigated the use of ultrasound and microbubbles to dissolve blood clots in situ [8]. Around the turn of the twentieth century, ultrasound-mediated drug delivery research had expanded as far as enabling measurable gene transfection in tissue [9], as well as transient, noninvasive and targeted disruption of the blood-brain barrier [10]. Microbubble Engineering began to mature as a field during this time, and researchers began to explore new methods to load drugs and genes onto UCAs [11]. Thus, the microbubble emerged as a drug carrier that could transport and release therapeutic agents into tissue on-demand by the targeted application of ultrasound. Microbubble UCAs also play a key role in the utilization of novel plane-wave imaging strategies, including super-resolution ultrasound localization microscopy of deep vascular structures [12]. On the therapeutic side, microbubble-assisted chemotherapy was recently shown to significantly improve outcomes for human pancreatic cancer patients [13], and microbubble-assisted blood-brain-barrier disruption is now in human clinical trials for treating brain cancer in both Europe and Canada (clinicaltrials.gov).

The development of microbubble engineering principles for advanced imaging and drug delivery has spawned new applications outside the field of ultrasound. Researchers have employed the methods to synthesize perfluorocarbon microbubbles to encapsulate other gases, such as oxygen [14]. Microbubble encapsulation of oxygen has provided a biocompatible formulation for direct injection into the bloodstream or body cavities [15,16]. Oxygen and other bioactive gases can thus be delivered passively by diffusion or actively by stimulation with ultrasound to improve the effects or radiotherapy, for example [17]. Until recently in the field of molecular diagnostics, UCAs have long been handicapped by potentially immunogenic conjugation chemistries, which are essential to the attachment of targeting moieties and probes to the microbubble surface. The state-of-the-art in non-toxic conjugation schemes, such as azido click-chemistry, has recently been applied to pre-clinical UCAs with demonstrable biocompatibility in a large animal model [18]. Currently, we witness the advent of promising near-clinical applications for blood-brain-barrier disruption and drug-delivery in the treatment of neurological diseases such as brain cancer and Alzheimer’s [19–21]. These applications often repurpose existing UCAs such as Sonovue and Definity to translate a purely thermal (and potentially unsafe) process involving the use of focused ultrasound (FUS) alone, into a safer mechanical process by using microbubbles as actuators of acoustic forces. In pursuit of such applications, Microbubble Engineering has emerged as an important discipline within the field of colloid science.

Two approaches to microbubble development have been employed. Clinicians and health-technology professionals began by developing simple UCA formulations to achieve regulatory approval, and now use them based on their regulatory status with the aim of increasing translational potential. At the same time, researchers have taken to engineering, validating and optimizing novel microbubble formulations for a particular application, such as molecular imaging or drug delivery. As expected of efforts surrounding clinical translation, the field has begun to favor convergence of these two approaches, in which parametric considerations and their bioefffects in vivo produce validating, but not necessarily expository data regarding paths for microbubble engineering. This lack of exposition, and significant pockets of misunderstanding regarding the fundamental principles of microbubble engineering, has resulted in debates regarding dose metrics for therapeutic studies [22,23], acceptable doses [24,25] and even safety in established imaging applications [26,27]. We therefore offer the following review of UCA microbubbles to stimulate greater sophistication in microbubble design and insights into their ultimate clinical translation.

Reverse Engineering

Future UCAs face significant barriers to adoption, yet offer the expected advantages of next-generation theranostic agents. The cost and time involved in regulatory approval processes are sizeable, but at the same time it is not difficult to identify significant obstacles in the repurposing of existing UCA formulations for future applications. For example, the use of fluid volume as a dose metric and the absence of an effect-associated dose metric impedes comparisons of safety and efficacy in theranostic applications [24,25]. Indeed, significant differences in bioeffects due to microbubble size alone can be seen in both therapeutic and imaging applications [22,28,29]. Such effects, paired with batch-to-batch inconsistencies in microbubble concentration between competing formulations (or even the same formulation) are imposing factors when considering the cost of implementing new formulations and evaluating safety for clinical use [30]. It is up to investigators to engineer not only an agent, but to accommodate prospective questions and concerns regarding the adoption of the microbubble design, be it wholly novel or a modified formulation.

The purpose of this review is to facilitate the rational design of next-generation microbubbles through reverse engineering of UCAs that are currently approved for clinical use. The review follows a paradigm set forth in an illuminating book chapter by David Needham [31], featuring another colloidal system - low-temperature-sensitive liposomes - which is deconstructed to teach the development and validation steps and gain deeper insight. Needham argued that undertaking the process of reverse engineering helps to develop deeper learning, problem solving skills, critical thinking and inventiveness. According to Needham, reverse engineering involves finding answers to a few key questions in order to identify the essential design features of a device, product or process:

What is it for?

How should it work?

What is it made of?

How is it made?

What are the characteristics of the material?

Has anybody made something similar?

Does it really work?

These simple questions become relevant as we witness the continued application of primitive UCAs for more sophisticated applications, such as the repurposing of diagnostic UCAs for therapeutic applications. Indeed, the feasibility and efficacy of innovations in ultrasound theranostics will require novel UCA formulations. This review article aims to guide the reader through the reverse engineering process, highlighting critical functions expected of UCA formulations, and interrogating the current state-of-the-art from an engineering perspective. Such an approach provides an objective method for evaluating both existing and new microbubble products, and outlines a streamlined path towards optimizing microbubbles for future applications. Below we provide answers to each of these reverse-engineering questions, in turn.

Application of UCAs in biomedicine

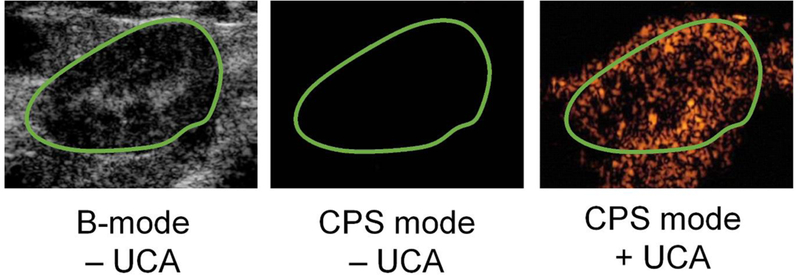

Ultrasound is unique among the imaging techniques in that it uses mechanical waves rather than electromagnetic waves to image the structures and processes of the body. A typical ultrasound image acquisition cycle uses the pulse-echo method, in which a high-frequency ultrasound pulse is transmitted from a transducer probe into the body, and the resulting reflected and backscattered waves are received and processed to form an image. The speed of sound in tissue is quite fast (1540 m/s), so frame rates can be as high as 1500 Hz. The high frame rate allows high temporal resolution of dynamic processes, such as turbulent flow in the carotid artery. Alternatively, the high frame rate provides high sensitivity to detect anatomical features through signal averaging and super-resolution methods. Ultrasound is also portable and inexpensive compared to other imaging modalities. The main drawback of ultrasound is the image quality, which is limited by the inherent scattering properties of tissue. Blood in particular is a poor ultrasound scatterer. The comparatively high scattering of interstitial tissue makes it difficult to distinguish echoes from vascular structures within the tissue, or to visualize cardiac structures. The purpose of the UCA is to increase acoustic scattering of the blood beyond that of tissue, and thus create sufficient contrast between vascular structures and interstitial tissue (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image enhancement with microbubble UCAs. Shown are a b-mode image of the rat kidney and Cadence Pulse Sequencing (CPS) mode images before and after UCA injection taken with a Siemens Sequoia ultrasound scanner. Note that the green boundary defining the kidney as the region of interest is drawn from the anatomical B-mode image, and that contrast is observed outside the kidney owing to nearby vasculature. Images from [33].

In theranostic applications, the purpose of UCAs is to serve not only as an imaging probe, but also as a mechanical cell and tissue disruptor, a microfluidic mixer and a drug delivery vehicle. By applying ultrasound at an elevated intensity, a microbubble undergoes larger amplitudes of oscillation than those seen in contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Consequently, these oscillations effect mechanofuidic permeabilization of tissue within approximately a diameter’s range of the microbubble [34,35]. This behavior is advantageous in the context of transient and tunable blood-brain barrier disruption, a primary focus of current therapeutic UCA applications [19,21,20]. As a delivery vehicle, the purpose of UCAs is to localize release of drug molecules, which may be dissociated from the microbubble via these same large-amplitude oscillations [36,37]. Compared to other technologies in drug delivery, UCAs offer the significant advantage of spatio-temporally targeting. The combined capability to sense and actuate the microbubble with ultrasound provides unprecedented capability for feedback-control of pharmaceutical delivery.

Properties of the UCA

Safety for intravenous injection

For obvious reasons, a contrast agent should be safe to inject into the bloodstream. It should be small enough (<10 μm diameter) to traverse the capillary vessels without occluding flow. This sets the upper limit for a microbubble to about the size of a red blood cell. It also should be nontoxic and biologically inert - that is, it should not induce any unintended physiological processes, such as activation of the immune system or the thrombotic cascade. Therefore, a contrast agent should be non-immunogenic, and it should only be made of biocompatible components that can easily be metabolized and excreted from the body. The current FDA-approved and commercially available UCAs have been tested extensively for safety, in both retrospective and prospective trials [38,39]. Names and characteristics for three UCAs currently on the market are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Currently FDA-approved and commercially available UCAs.

| UCA | Gas | Shell | Size (Diameter) | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Optison™ (GE Healthcare) |

C3F8 |

Protein Human serum albumin 𝜓₀ = −9.5 mV |

3.0 – 4.5 μm (max 32 μm) 95% less than 10 μm |

5.0–8.0 × 108 /mL |

|

Definity® (Lantheus) |

C3F8 |

Phospholipid DPPC: 0.401 mg/ML DPPA: 0.045 mg/mL DPPE-mPEG5000 : 0.304 mg/mL 𝜓₀= −4.2 mV |

1.1 – 3.3 μm (max 20 μm) 98% less than 10 μm |

1.2 × 1010 /mL |

| Sonovue® aka Lumas on® (Bracco) | SF6 |

Phospholipid DSPC: 0.038 mg/mL DPPG: 0.038 mg/mL PA: 0.008 mg/mL 𝜓₀= −28.3 mV |

1.5 – 2.5 μm (max 20 μm) 99% less than 10 μm |

1.5–5.6 × 108 /mL |

DPPC = 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DPPA = 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate; DSPC = 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DPPE-mPEG5000 = 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-5000]; DPPG = 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol); PA = palmitic acid; 𝜓₀ is the zeta potential measured [40].

As the table shows, microbubble stabilization has been accomplished by encapsulation of low-solubility, biologically inert gases (SF6 and C3F8) within a biologically degradable shell of lipid or protein. The necessity of a gas core is discussed next, in the context of acoustic scattering. Dissolution of the gas core is unavoidable owing to ventilation/perfusion mismatch of oxygen at the alveolus, but the process can be delayed long enough for an ultrasound examination by using low-solubility gases. Of course, the gas itself must be nontoxic and biologically inert. As will be shown below, a shell is needed to stabilize the microbubble against coalescence and rapid dissolution. From the standpoint of safety, the shell is necessary to protect the thrombogenic gas surface from clotting factors in the blood.

Echogenicity

The UCA should have a large acoustic scattering cross section in order to scatter sound waves more strongly than blood and interstitial tissue structures. Scattering occurs when an object is much smaller than the acoustic wave. This limit is expressed mathematically for a sphere by the relation kR << 1, where R is radius and k is acoustic wavenumber (k = 2πf /c; where f is frequency and c is sound speed). Red blood cells are the main endogenous acoustic scatterers in blood. The echogenicity of a particle is quantified by the scattering cross section (m2), defined as the ratio of the scattered power (W) and the incoming sound intensity (W m−2). Rayleigh derived an expression for the acoustic scatter (σs) of a particle in terms of its size, mass density and compressibility [41]:

| (1) |

where ρ and ρ0 are the mass densities of the particle and medium, respectively, and K and K0 are the compression bulk moduli of the particle and medium. The term πR2 is the particle’s geometric cross section, and the term (kR)4 gives the frequency dependence. Overall, the scattering cross section scales with particle size as R6. Thus, a single 1-pm particle scatters as much as one million 100-nm particles. It is therefore advantageous to use larger microbubbles, provided they are small enough to traverse the capillaries (<10 μm diameter).

Additionally, the scattering cross section scales as f4, but frequency is often limited by the range of clinical ultrasound (1–10 MHz). The properties ρ0 and K0 of blood are fixed to the values of water. This leaves particle properties ρ and K as the only adjustable parameters to maximize the value of σs. The effect of particle density on scatter is quite small, typically less than 10% [42]. On the other hand, particle compressibility has a very large effect, especially if the particle is highly compressible (low K). This is perhaps the raison d’etre of the gas core in UCA design. No other state of matter lends such high compressibility: a microbubble is the most echogenic particle that can be achieved. For a given particle size and ultrasound frequency, the Rayleigh scattering cross section for gas is ~109 fold greater than for liquid (glycerin) and ~108 fold greater than for solid (steel) [42].

The microbubble echo is further amplified by resonance phenomena. For small-scale oscillations (ΔR/R << 1), the linearized resonance frequency for a bubble is given by the following expression [42]:

| (2) |

where γ is the gas/water interfacial tension, κ is the polytropic gas constant and P0 is the hydrostatic pressure. For a free (unshelled) microbubble, the surface tension is γ = 0.072 N/m, which gives a resonant radius R0 ≈ 4 μm at 1.0 MHz and R0 ≈ 0.6 μm for 10 MHz. Fortuitously, microbubbles resonate at or near frequencies used by clinical ultrasound scanners. The scattering cross section for small-amplitude (linear) oscillations is given by [42]:

| (3) |

where Ω = f/f0 is the ratio of acoustic driving frequency to the bubble resonance frequency and S is the damping constant. Damping includes contributions from acoustic re-radiation (δrad ), viscous dissipation of the medium (δvis ) and thermal hysteresis (δth). At resonance, approximate equations for these damping terms are [43]:

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

| (4c) |

where μ is the medium viscosity. Thermal damping is of similar magnitude to the viscous dissipation damping for UCAs, so one can (if expedient) omit δth, double δvis, and achieve near-parity [43]. These equations allow one to estimate the scattering cross section for an unshelled bubble driven at its resonance frequency. Figure 2 shows a plot of the scattering cross section versus radius for liquid and solid particles, as predicted by Rayleigh theory, compared to resonant microbubbles. The graph shows that at 1 MHz, the lower limit for clinical diagnostic ultrasound, the resonant microbubble scatters ~1011 fold more than an equivalently sized liquid drop. At the upper limit of 10 MHz, the resonant microbubble scatters ~109 fold more than an equivalently sized liquid drop. The enormous amplification in acoustic backscatter is precisely why microbubbles are the dominant UCA.

Figure 2.

Particle acoustic scattering cross section versus radius. Rayleigh theory (equation 1) was applied to estimate the cross sections for liquid (glycerin) and solid (steel) microspheres. The simple oscillator model (equations 2–4) was used to estimate the cross section for resonant gas bubbles - that is, the bubble is driven at its resonance frequency for each size. Solid lines show the cross sections at 1 MHz for liquid and solid particles. Dashed lines show the cross sections at 10 MHz for liquid and solid particles. Arrows show the cross sections for resonant gas bubbles at these frequency limits.

Stability against coalescence

A contrast agent should be stable long enough in suspension for storage, handling and injection, as well as in vivo for the imaging exam (5–30 min). In the preceding section, it was illustrated that a microbubble is an ideal UCA owing to its excellent echogenicity. Unfortunately, unshelled microbubbles are neither biocompatible nor stable. The free gas/water interface is highly thrombogenic due to its propensity for rapid plasma protein adsorption. In addition, unshelled microbubbles are prone to the destabilizing mechanisms of coalescence and dissolution. The problem of coalescence can be addressed by considering the range and magnitude of the surface forces involved as two microbubbles approach one another. As two bubbles collide, the probability of coalescence is given by [44]:

| (5) |

where τd is the drainage time and τc is the contact time. The drainage time τd is the characteristic time it takes to drain the thin liquid film of medium between the two bubbles brought together. This analysis is useful to examine coalescence under conditions of fluid flow, e.g. in a flow focusing device, where collisions are brought about by convection. On the other hand, microbubble stability during storage in the vial can be considered from an alternative viewpoint of the energetics. It is generally considered safe to assume that the microbubbles are stable against coalescence if an energy barrier exists between them that exceeds 25 kT, where k is Boltzmann’s constant and T is absolute temperature [45].

First, consider the interaction between two unshelled microbubbles. All particles interact by the ubiquitous and usually attractive van der Waals force, which arises from a discontinuity in the dielectric properties of the intervening medium. For two spheres of equal radius R separated by a distance x, the van der Waals interaction energy is given by [45]:

| (6) |

where A is the Hamaker constant (3.7 × 10−20 J for two air bubbles in water). The negative sign denotes an attractive force. A second interaction between two unshelled microbubbles in water is the attractive hydrophobic force, where the interaction energy is given by [46]:

| (7) |

where γi is the interfacial energy and x0 is a characteristic decay length, approximately equal to the size of one water molecule (0.3 nm). Uncoated bubbles experience a large attraction because γi is equal to the surface tension of water, 72 mN/m at 25 °C. Figure 3a shows the theoretical interaction potential for two approaching 3-μm diameter bubbles that are uncoated. The van der Waals and hydrophobic attraction forces combine to give a strong, long-range attraction, and the bubbles readily coalesce.

Figure 3.

Theoretical energy-distance profiles between two 3-μm diameter bubbles. a) Uncoated: van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions yield a purely attractive (negative) potential. b) Optison: the protein shell removes the hydrophobic attraction and imposes electrostatic and hydration repulsions, generating an energy barrier to coalescence. c) Sonovue: the lipid shell imposes electrostatic and protrusion repulsions, generating a purely repulsive (positive) potential. d) Defnity: the PEG brush on the lipid shell yields a long-range repulsion.

Coalescence can be avoided by adding a shell onto the microbubble that diminishes the attractive hydrophobic force, while also imposing new repulsive surface forces that overpower the van der Waals surface force. Current UCAs comprise a surfactant shell (protein or lipid) that has hydrophilic chemical groups facing the aqueous medium. Recall that Table 1 above shows a list of currently FDA-approved and commercially available UCAs, as well as their composition, surface potential (charge), size and concentration.

All of the commercial UCAs listed in Table 1 have an anionic surface charge [40]. The charged surface results in an enriched “double layer” of counter ions in the intervening medium that yields an osmotic repulsion, whose interaction energy for two spheres is given by [45]:

| (8) |

where κd−1 is the Debye length (~0.7 nm in physiological phosphate buffered saline) and Z is an interaction constant is the dielectric constant, Ɛ0 is the dielectric constant for water, e is the electronic charge, z is the counter ion charge valence and 𝜓0 is the surface potential, related to the surface charge σ by the relation . However, an analysis of the relative contributions of the electrostatic and van der Waals forces shows that a surface potential exceeding −50 mV would be necessary to stabilize the microbubbles under physiological conditions. Indeed, the surface charge is mainly used to mimic the erythrocytes, which have a negatively charged glycocalyx, in order to minimize interactions between the microbubbles and other cells in the cardiopulmonary system.

It turns out that the commercial UCAs listed in Table 1 are stabilized by alternative mechanisms other than charge. For example, Optison microbubbles are stabilized by a protein shell, and it is well documented that proteins exhibit short-range “hydration” repulsion [47]. The hydration force is analogous to the hydrophobic force in that it exhibits an exponential decay, but instead it is a repulsive force between hydrophilic surfaces. The force arises from the work required to remove the layer of tightly bound water molecules (the hydration shell) from the protein’s hydrophilic surface, in order to advance the surfaces into contact. The hydration interaction potential between two spheres is given by [45]:

| (9) |

where λh is a characteristic decay length (~0.6 nm) and Wh is an interaction energy (~30 mJ m−2). The hydration force is sufficient to stabilize protein-shelled microbubbles, such as Optison, against coalescence. Figure 3b shows the theoretical interaction potential between two 3-μm diameter Optison bubbles based on the equations above. The surface of Optison is negatively charged [40], but it is the hydration force that provides stability.

The other commercial UCAs listed in Table 1, and many of the synthesized microbubbles described in the literature [48], are coated with lipids. Lipid membranes are known to exhibit short-range repulsive forces owing to out-of-plane protrusions and membrane undulations (the latter can be neglected for the gel-state lipids used to coat microbubbles). A repulsive force arises from the entropy loss as the protrusions are confined while the two surfaces approach. The protrusion interaction potential between two spheres is given by [45]:

| (10) |

where Γ is the lipid surface density and λp is a characteristic decay length (~0.1 nm). The protrusion force is sufficient to stabilize lipid-coated microbubbles, such as Sonovue. Figure 3c shows the theoretical interaction potential between two 3-μm diameter Sonovue bubbles. The surface of Sonovue is negatively charged [40], but it is the protrusion force that provides stability.

Defnity microbubbles also comprise lipids, but 8 mol% of the lipids are conjugated to methyl-terminated poly(ethylene glycol) (mPEG) of ~5000 Da molecular weight (average value due to polydispersity of the PEG). The methyl termination is critical to limiting immunogenicity, as the unstable thioester group on complement protein C3b is known to bind to free hydroxyl groups [49]. PEG is a hydrophilic and dynamic polymer, which extends away from the lipid surface into the aqueous medium. The inter-PEG distance for Definity is ~2.4 nm, which is smaller than the Flory radius of ~6.0 nm, so the PEG molecules form a hydrated brush on the microbubble surface. The length L of the brush is ~11 nm. Collision of two microbubbles leads to compression of the brush layers, and the interaction energy is given by [45]:

| (11) |

where Γ is the PEG surface coverage (1.76× 105 molecules/pm2) and L is the brush length (11.1 nm). Figure 3d shows the theoretical interaction potential between two 3-μm diameter Definity bubbles. The PEG brush yields a long-range steric repulsion that extends tenfold longer than the hydration or protrusion forces.

These calculations show how the various shells of commercial UCAs can add repulsive forces (electrostatic, hydration, protrusion and polymer-steric) to overwhelm the van der Waals attraction. In each example, the repulsive forces produced an energy barrier far in excess of 25kT, thereby stabilizing the microbubbles against diffusion-induced coalescence. This should lead to long-term stability, provided the microbubbles are stable against dissolution, which is considered below. Finally, it should be noted that microbubbles can be made to coalesce by other mechanisms, such as ultrasound-induced oscillations [50].

Stability against dissolution

The second destabilization mechanism for microbubbles is dissolution of the gas into the surrounding aqueous medium. For populations of densely concentrated microbubbles, this same mechanism can lead to Ostwald ripening [51], where gas difuses from smaller to larger bubbles until the gas phase separates completely. A model for microbubble dissolution into an isotropic, infinite medium was first derived by Epstein and Plesset [52]:

| (12) |

where again R is bubble radius, t is time, D is gas diffusivity in the aqueous medium, H is Henry’s constant (H = cs/ρ; cs is the mass concentration of the gas solute in the aqueous medium and ρ is the mass concentration of gas in the contacting gas phase), F is the ratio of dissolved gas concentration to that at saturation , Λ is a function of surface tension ; M is the gas molecular weight and B is the universal gas constant) and ρ∞ is the mass concentration of gas in the gas phase for a flat interface at system pressure P (ρ∞ = MP/BT). The time-dependent term in the second brackets of equation (12) can be neglected due to rapid establishment of the gas concentration profile in the aqueous phase surrounding the bubble [53].

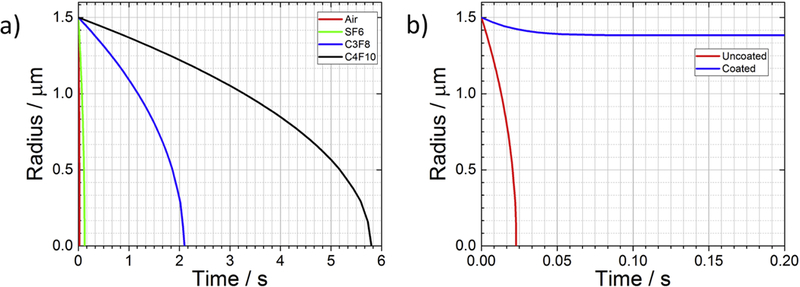

An uncoated gas microbubble has surface tension (γ ≈ 0.07 N/m), which as seen in equation (12) leads to a finite value for A and therefore rapid dissolution even in a saturated solution (F = 1). The dissolution rate (—dR/dt) can be reduced by the choice of low-solubility gases, such as SF6 or C3F8. Figure 4a shows the lifetimes of 3-μm diameter bubbles containing different gases, such as those used in the commercial UCAs (Table 1). Note that SF6 only slightly increases stability over air in comparison to the perfluorocarbons. Microbubble dissolution within seconds remains unavoidable due to surface tension. However, in a multi-gas environment, such as when an SF6 bubble is injected into blood containing N2 and O2, the lifetime is extended significantly by the process of gas exchange [54,55].

Figure 4.

Theoretical dissolution curves for a 3-μm diameter bubble. a) Uncoated microbubbles containing various gases in a saturated medium dissolving due to surface tension; gas parameters taken from [60]. B) Lipid-coated vs. uncoated air bubbles dissolving in an undersaturated medium (F = 0.8); lipid shell permeability is taken from [64] and elasticity is taken from [61].

Microbubble coatings used for commercial contrast agents inhibit dissolution by diminishing (or possibly eliminating) surface tension [56,53]. According to equation (12), , and UCAs are thus stable in saturated media. Upon injection into the body, however, microbubbles experience hemodynamic pressure variations [57] and under-saturation of total dissolved gases due to ventilation-perfusion mismatch [58]. While these forces ultimately ensure complete bubble dissolution, the rate is hindered by the limited permeability [59] and elasticity [60] of the shell, thereby allowing sufficient stability for an imaging exam. Coated microbubbles dissolve according to a modified Epstein-Plesset relation [61]:

| (13a) |

| (13b) |

where is the mass transfer resistance of water, Ωshell is the mass transfer resistance of the shell, γ0 is the shell surface tension at the resting radius R0, and E is the shell elasticity E0 and α are material constants following work by Kausik Sarkar’s group [62]. In theory, the permeation resistance and elasticity of a lipid shell can stabilize a microbubble even in a degassed environment, as shown in Figure 4b. In reality, however, the lipid monolayer shell is unstable to sustained compression and periodically collapses [59,63], leading to complete dissolution in an under-saturated medium. Here, the chemical potential gradient for the gas provides the work necessary to compress, buckle and fold the lipid shell. The process occurs in multiple discrete crumpling-to-smoothing transitions. In saturated media, the chemical potential gradient vanishes, and the microbubble is stable indefinitely.

UCA composition

The components of commercial UCAs are listed in Table 1 and shown schematically in Figure 5. Optison microbubbles consist of a perfluoropropane core coated with human serum albumin protein. Serum albumin is the most abundant protein in blood, which in principle should make the agent biocompatible for intravenous injection. During the manufacturing process, the heat-denatured protein acts as a surfactant and adsorbs to the gas/water interface. Proteins spontaneously attach to gas/water interfaces owing to their amphiphilicity and internal ordering, which is relieved when the protein adsorbs and partially unravels (increasing entropy). The aggregated protein shell is estimated to be ~15 nm thick [65]. A vial of Optison contains up to ~8 × 108 /mL with a volume fraction of ~3.5% [66]. Note that the size distribution is highly polydisperse, and both size and concentration vary from batch-to-batch [30].

Figure 5.

Cartoon schematic of shell and gas components for Optison, Sonovue and Definity. Molecular structures are not shown to scale.

Defnity and Sonovue both have lipid shells primarily comprising zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine and an anionic phospholipid. The acyl chains are fully saturated to give a straight (all trans) configuration to allow close packing and enhanced cohesion. Sonovue has palmitic acid, which is a single-chain, anionic lipid. Defnity has a phospholipid-anchored hydrophilic PEG polymer, which as discussed above provides steric stabilization against coalescence. The lipids self-assemble into a monolayer at the gas/water interface, with their headgroups facing the aqueous medium and their tails facing the gas phase. Surface tension- driven dissolution forces the lipids to pack tightly on the interface; the estimated area per molecule is ~0.45 nm2 [67,68]. A vial of Sonovue contains up to ~5.6 × 108 /mL with a volume fraction of 0.65%, and a vial of Defnity contains up to ~1.2 × 1010 /mL with a volume fraction of ~4.4% [66]. Again, note that the size distributions of these agents are highly polydisperse, and both size and concentration vary significantly from batch-to-batch.

UCA synthesis

Each commercial UCA is manufactured differently, and these manufacturing methodologies become increasingly important in high-volume applications such as oxygen delivery [15], or in formulations which require efficient drug-loading or conjugation of costly biologics. Optison is made by heating a 0.5–3% (w/v) solution of human serum albumin to 65–80 °C and applying mechanical shearing and hydrodynamic cavitation in the presence of C3F8 by a milling process to produce the microbubbles (Figure 6a), which are then cooled and stored under refrigeration [69]. The Optison microbubbles come to the user already prepared and stored in a sealed vial. One gently agitates the vial to disperse the microbubbles. While extracting the microbubbles with a syringe, an extra syringe needle is placed in the rubber septum to serve as a vent, in order to avoid inducing a vacuum that could destabilize the microbubbles. The recommended dose for human clinical imaging is 0.5 mL, corresponding to a microbubble volume dose of ~22 μL.

Figure 6.

Methods of UCA manufacture: A) Optison is made by mechanical cavitation (mechanical shearing and hydrodynamic cavitation) in a rotor-stator homogenizer mill. B) Defnity is made by shaking back-and-forth at 4–5 kHz in a vial shaker. C) Sonovue is made by rehydrating a freeze-dried lipid powder.

Defnity microbubbles are made on demand at the patient bedside, via “activation” with a vial shaker [70] (Figure 6b). Prior to activation, each vial contains 6.52 mg/mL C3F8 in the headspace, and each mL of the clear liquid contains 0.75 mg lipid blend (consisting of 0.401 mg DPPC, 0.304 mg DPPE-mPEG5000 and 0.045 mg DPPA), 103.5 mg propylene glycol and 126.2 mg glycerin. Microbubbles are formed by mechanical agitation as the vial is shaken back and forth at a speed of ~4500 Hz for 45 s. The newly formed microbubbles are ready to be extracted via a syringe and vent for intravenous injection. The recommended bolus dose is 10 pL/kg corresponding to a microbubble volume dose of ~44 μL (for an average adult).

Sonovue microbubbles are also made on demand from freeze-dried lipid [71]. Each vial contains a white powder consisting of 24.56 mg of free PEG4000, 0.19 mg DSPC, 0.19 mg DPPG and 0.04 mg PA, as well as 60.7 mg SF6 gas in the headspace. Microbubbles form spontaneously when 5 mL of diluent is added to the vial (Figure 6c), and are ready to be extracted via a syringe and vent for intravenous injection. The recommended dose for echocardiography is 2.0 mL, corresponding to a microbubble volume dose of ~16 μL.

UCA Material Properties

All of the commercial UCAs are echogenic and provide adequate contrast for their clinical imaging indications. Optison was the first of the current commercial UCAs to be approved. The C3F8 gas clears relatively quickly from the body through the lungs. In a clinical trial described in the package inset, a single intravenous dose of 20 mL of Optison was given to healthy volunteers, and most of the C3F8 was eliminated through the lungs within 10 min. The recovery was 96% ± 23% (mean ± SD), and the pulmonary elimination half-life was 1.3 ± 0.69 min. The C3F8 concentration in expired air peaked approximately 30–40 s after administration. In another reported clinical trial, the median duration of Optison contrast enhancement for each of four doses (0.2, 0.5, 3.0 and 5.0 mL) was approximately one, two, four and five min, respectively. Albumin-coated microbubbles are known to bind complement protein C3b [72], which may reduce circulation persistence and can lead to hypersensitivity. Complement fixation may be why Optison microbubbles are avidly taken up by liver Kupffer cells [73]. When driven by ultrasound, albumin-coated microbubbles are known to exhibit “sonic cracking”: during expansion the shell ruptures and an uncoated gas bubble emerges that then rapidly dissolves owing to surface tension [74,75]. The protein shell is expected to be metabolized by the normal human routes for serum albumin.

Defnity was the first lipid-coated microbubble to be approved for human use. Clinical trials show similar behavior with Optison, which has the same gas core species. Following an intravenous injection, the C3F8 was not detectable after 10 min in most subjects either in the blood or in expired air. C3F8 concentrations in blood were shown to decline in a mono-exponential fashion with a mean half-life of 1.3 min in healthy subjects. The lipid shell is thought to be metabolized to free fatty acids. The duration of useful contrast detection at the recommended dose for a bolus injection is 3.4 min. The PEGylated shell is believed to reduce complement C3 binding [76], but the PEG brush may also induce an antibody response after multiple administrations [77]. The acoustic behavior of lipid-coated microbubbles is markedly different from that of protein-coated agents: the shell is highly compliant to both compression and expansion, and the bubble remains encapsulated and stable after the pulse. As the mechanical index is increased, lipid-coated microbubbles may experience acoustically driven dissolution, presumably via lipid shedding [78], and fragmentation [74].

Sonovue (Lumason) is the most recent contrast agent to be approved in the US for echocardiography. Interestingly, despite the prediction of rapid dissolution in Figure 4, the SF6 gas has a similar half-life to the perfluorocarbon used in the other agents. This may be due to a gas-exchange process between the SF6 core and dissolved gases in the blood [54,55]. According to the package insert for Sonovue, after intravenous bolus injections of 0.03 mL/kg and 0.3 mL/kg, corresponding to approximately 1 and 10 times the recommended doses, concentrations of SF6 in blood peaked within 1–2 min for both doses. The terminal half-life of SF6 in blood was approximately 10 min for the 0.3 mL/kg dose. The area-under-the-curve of SF6 was dose-proportional over the dose range studied. Twenty minutes following injection, the mean cumulative recovery of SF6 in expired air was 82 ± 20% at the 0.03 mL/kg dose and 88 ± 26% at the 0.3 mL/kg dose. SF6 undergoes first-pass elimination within the pulmonary circulation; approximately 40% to 50% of the SF6 content was eliminated in the expired air during the first minute following injection. Following the first appearance of contrast within the left ventricle, the mean duration of useful contrast effect ranged from 1.7 to 3.1 minutes. Sonovue showed markedly less uptake by liver Kupffer cells than Optison [73]. According to a study performed by researchers at Bracco [66], the acoustic behavior and stability of Sonovue is similar to Defnity, as both are coated with phospholipids, and superior to Optison. Sonovue was the first UCA approved by the FDA for liver imaging and pediatric imaging.

Off-Market and Preclinical UCAs

Other UCAs have been approved in the US, but are not currently on the market. This includes lipid-coated, C5F12/N2-flled Imagent (Alliance Pharmaceutical), as well as the air-filled agents Levovist (lipid/galactose shell) and Albunex (albumin shell), the latter of which was replaced by the longer circulating Optison. Other UCAs have only been approved outside the US, such as lipid-coated, C4F10-flled Sonazoid (GE Healthcare). Yet more UCAs have been under development, but not yet approved, such as the polymer-coated Sonovist (Scherring) and Cardiosphere (Point Biomedical).

One exciting development in the ultrasound molecular imaging community is the experimental agent BR55 (Bracco): a lipid-coated, C4F10-fiUed microbubble decorated with peptides targeted to VEGFR2, a biomarker for tumor angiogenesis [79]. The peptides on the microbubble surface bind to VEGFR2 molecules overexpressed on the endothelium, causing the microbubble to adhere to the neovessels. The molecular imaging agent has been shown to improve diagnosis of prostate cancer [80] and breast cancer [81] in human patients. This new agent may open the gateway for more targeted UCAs in the future. Fujiflm Visualsonics also markets non-targeted and target-ready Micromarker (Bracco) for preclinical use with high- frequency small-animal scanners.

Another exciting development is the commercialization of monodisperse microbubbles. Advanced Microbubble Labs (Boulder, CO) now markets size-isolated microbubbles (SIMB) for research use. The lipid-coated, C4F10-filled SIMBs are packaged ready-for-use in various sizes, from 1–2 μm to 6–8 μm diameter (Figure 7a). Additionally, Tide Microfuidics (Enschede, The Netherlands) now markets a microfluidic device to generate highly monodisperse microbubbles. The device makes use of recent advances in microfluidic flow-focusing to generate microbubbles with precise size and shell properties (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Commercialized next-generation microbubbles: A) Size-Isolated Microbubbles (SIMBs); graphic taken from AMB Labs (www.advancedmicrobubbles.com). B) Microfluidic microbubbles; graphic taken from Tide Microfluidics (www.tidemicrofluidics.com).

Performance of UCAs in imaging and therapy

UCAs have been used in millions of patients throughout the world, and they have proven safe and efficacious for diagnostic monitoring through a rigorous regulatory process [38,39]. Unfortunately, all of the current commercial UCAs were developed almost three decades ago, mainly for echocardiography. Owing to intellectual property and regulatory constraints, these agents have changed very little from their original formulations. At the same time, microbubble technology has made enormous advancements. There are now vast numbers of UCA synthesis techniques and designs described in the research literature, including targeted microbubbles, drug/gene-loaded microbubbles, multi-modal imaging agents, phase-change agents and many others. At the same time, our understanding of microbubble physical, chemical and biological behavior has improved tremendously. It is now clear that the currently approved UCAs are somewhat crude in terms of material characteristics, physical properties and biomedical performance compared to next-generation microbubble designs, and there is a need to translate these advanced formulations through regulatory approval and to clinical adoption.

At the same time, ultrasound devices have gotten smaller, faster and smarter than ever. For example, the iQ Butterfly device was approved by the US FDA in 2018 for 13 applications [82]. This revolutionary ultrasound imaging probe plugs into your smart phone, employs machine learning to optimize images and costs only ~$2,000. As another example, MRI-guided focused ultrasound devices have been approved by the US FDA for treatment of uterine fibroids, prostate cancer, bone metastasis and other indications [83]. While such “hardware” technologies have been readily approved and adopted, the “software” technology (microbubble UCAs) has been largely neglected when it comes to clinical translation. This is problematic, as it could be argued that the microbubble, which is injected into the patient, is just as important as the external ultrasound device. Clinical applications employing microbubbles are therefore using sub-optimal technology because clinical adoption of microbubble technology has lagged that of ultrasound devices. The translation of more sophisticated microbubble designs to clinical practice will require a paradigm shift in the attitude of engineers and clinicians to value the importance of UCA “software” as much as ultrasound device hardware and their novel applications.

Conclusions

In this review, a brief history and current state-of-the-art is given to stimulate the rational design of new microbubbles through the reverse engineering of current UCAs. It is shown that an effective microbubble should be biocompatible, echogenic and stable. Physical mechanisms and engineering calculations have been provided to illustrate these properties and how they can be achieved. The rational design paradigm championed by David Needham [31] is applied to study current FDA-approved and commercially available UCAs. Given the sophistication of microbubble designs reported in the literature, rapid development and adoption of ultrasound device hardware and the growing number of revolutionary biomedical applications moving toward the clinic, the field of Microbubble Engineering is fertile for breakthroughs in next- generation UCA technology. It is up to current and future microbubble engineers and clinicians to push forward with regulatory approval and clinical adoption of advanced UCA technologies in the years to come.

Highlights:

Ultrasound contrast agents are echogenic microbubbles used in medical diagnostics.

Their components can be deconstructed using reverse engineering principles.

The components act to stabilize against coalescence and dissolution.

Overall, their characteristics are dated and rather crude from an engineering perspective.

Better designs must be promoted to keep pace with device hardware and applications.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by NIH grant R01 CA195051.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Gramiak R, Shah PM. Echocardiography of the aortic root. Invest Radiol 1968;3:356–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Keller MW, Glasheen W, Kaul S. Albunex: a safe and effective commercially produced agent for myocardial contrast echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr Off Publ Am Soc Echocardiogr 1989;2:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jablonski EG, Dittrich HC, Bartlett JM, Podell SB. Ultrasound Contrast Agents: The Advantage of Albumin Microsphere Technology In: Thompson DO, Chimenti DE, editors. Rev. Prog. Quant. Nondestruct. Eval, Springer; US; 1998, p. 15–22. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-5339-7_2. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Unger E, Shen DK, Fritz T, Lund P, Wu GL, Kulik B, et al. Gas-filled liposomes as echocardiographic contrast agents in rabbits with myocardial infarcts. Invest Radiol 1993;28:1155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schneider M Characteristics of SonoVue(TM). Echocardiogr Mt Kisco N 1999;16:743–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Villanueva FS, Jankowski RJ, Klibanov S, Pina ML, Alber SM, Watkins SC, et al. Microbubbles targeted to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 bind to activated coronary artery endothelial cells. Circulation 1998;98:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Okada K, Kudo N, Niwa K, Yamamoto K. A basic study on sonoporation with microbubbles exposed to pulsed ultrasound. J Med Ultrason 2001 2005;32:3–11. doi:10.1007/s10396-005-0031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wu Y, Unger EC, McCreery TP, Sweitzer RH, Shen D, Wu G, et al. Binding and lysing of blood clots using MRX-408. Invest Radiol 1998;33:880–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shohet RV, Chen S, Zhou YT, Wang Z, Meidell RS, Unger RH, et al. Echocardiographic destruction of albumin microbubbles directs gene delivery to the myocardium. Circulation 2000;101:2554–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology 2001;220:640–6. doi:10.1148/radiol.2202001804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Unger EC, Porter T, Culp W, Labell R, Matsunaga T, Zutshi R. Therapeutic applications of lipid-coated microbubbles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2004;56:1291–314. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Errico C, Pierre J, Pezet S, Desailly Y, Lenkei Z, Couture O, et al. Ultrafast ultrasound localization microscopy for deep super-resolution vascular imaging. Nature 2015;527:499–502. doi:10.1038/nature16066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dimcevski G, Kotopoulis S, Bjanes T, Hoem D, Schjott J, Gjertsen BT, et al. A human clinical trial using ultrasound and microbubbles to enhance gemcitabine treatment of inoperable pancreatic cancer. J Control Release Off J Control Release Soc 2016;243:172–81. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Swanson EJ, Mohan V, Kheir J, Borden MA. Phospholipid-stabilized microbubble foam for injectable oxygen delivery. Langmuir ACS J Surf Colloids 2010;26:15726–9. doi:10.1021/la1029432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kheir JN, Scharp LA, Borden MA, Swanson EJ, Loxley A, Reese JH, et al. Oxygen gas- filled microparticles provide intravenous oxygen delivery. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:140–88. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Feshitan JA, Legband ND, Borden MA, Terry BS. Systemic oxygen delivery by peritoneal perfusion of oxygen microbubbles. Biomaterials 2014;35:2600–6. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fix SM, Papadopoulou V, Velds H, Kasoji SK, Rivera JN, Borden MA, et al. Oxygen microbubbles improve radiotherapy tumor control in a rat fibrosarcoma model - A preliminary study. PLOS ONE 2018;13:e0195667. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Slagle CJ, Thamm DH, Randall EK, Borden MA. Click Conjugation of Cloaked Peptide Ligands to Microbubbles. Bioconjug Chem 2018;29:1534–43. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Carpentier A, Canney M, Vignot A, Reina V, Beccaria K, Horodyckid C, et al. Clinical trial of blood-brain barrier disruption by pulsed ultrasound. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:343re2–343re2. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lipsman N, Ironside S, Alkins R, Bethune A, Huang Y, Perry J, et al. ACTR-42. INITIAL EXPERIENCE OF BLOOD-BRAIN BARRIER OPENING FOR CHEMOTHERAPEUTIC-DRUG DELIVERY TO BRAIN TUMOURS BY MR-GUIDED FOCUSED ULTRASOUND. Neuro-Oncol 2017;19:vi9–vi9. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nox168.033. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lipsman N, Meng Y, Bethune AJ, Huang Y, Lam B, Masellis M, et al. Blood-brain barrier opening in Alzheimer’s disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun 2018;9:2336. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Song K- H, Fan AC, Hinkle JJ, Newman J, Borden MA, Harvey BK. Microbubble gas volume: A unifying dose parameter in blood-brain barrier opening by focused ultrasound. Theranostics 2017;7:144–52. doi:10.7150/thno.15987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].McMahon D, Hynynen K. Acute Inflammatory Response Following Increased Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Induced by Focused Ultrasound is Dependent on Microbubble Dose. Theranostics 2017;7:3989–4000. doi:10.7150/thno.21630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kovacs ZI, Burks SR, Frank JA. Reply to Silburt et al.: Concerning sterile inflammation following focused ultrasound and microbubbles in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2017;114:E6737–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711544114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McMahon D, Hynynen K. Reply to Kovacs et al. .: Concerning acute inflammatory response following focused ultrasound and microbubbles in the brain. Theranostics 2018;8:2249–50. doi:10.7150/thno.25468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Grayburn PA. “Product Safety” Compromises Patient Safety (an Unjustified Black Box Warning on Ultrasound Contrast Agents by the Food and Drug Administration)||Dr. Grayburn has received past research grant support for studying the ultrasound contrast agents mentioned in this editorial. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:892–3. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kusnetzky LL, Khalid A, Khumri TM, Moe TG, Jones PG, Main ML. Acute Mortality in Hospitalized Patients Undergoing Echocardiography With and Without an Ultrasound Contrast Agent. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1704–6. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sirsi S, Feshitan J, Kwan J, Homma S, Borden M. Effect of microbubble size on fundamental mode high frequency ultrasound imaging in mice. Ultrasound Med Biol 2010;36:935–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Choi JJ, Feshitan JA, Baseri B, Shougang Wang, Yao-Sheng Tung, Borden MA, et al. Microbubble-Size Dependence of Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Mice In Vivo. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2010;57:145–54. doi:10.1109/TBME.2009.2034533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Goertz DE, de Jong N, van der Steen AFW. Attenuation and Size Distribution Measurements of Defnity™ and Manipulated Defnity™ Populations. Ultrasound Med Biol 2007;33:1376–88. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Needham D Reverse engineering of the low temperature-sensitive liposome (LTSL) for treating cancer In: Park K, editor. Biomater. Cancer Ther, Woodhead Publishing; 2013, p. 270–353e. doi:10.1533/9780857096760.3.270. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bracco Diagnostics Inc.’s LUMASON® (sulfur hexafluoride lipid-type A microspheres) for injectable suspension, for intravenous use or intravesical use, receives U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for use in ultrasonography of the urinary tract in pediatric patients for the evaluation of suspected or known vesicoureteral reflux n.d. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/bracco-diagnostics-incs-lumason-sulfur-hexafluoride-lipid-type-a-microspheres-for-injectable-suspension-for-intravenous-use-or-intravesical-use-receives-us-food-and-drug-administration-approval-for-use-in-ultrasonography−−300389247.html (accessed October 2, 2018).

- [33].Garg S, Thomas AA, Borden MA. The effect of lipid monolayer in-plane rigidity on in vivo microbubble circulation persistence. Biomaterials 2013;34:6862–70. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou Y, Kumon RE, Cui J, Deng CX. The size of sonoporation pores on the cell membrane. Ultrasound Med Biol 2009;35:1756–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fan Z, Liu H, Mayer M, Deng CX. Spatiotemporally controlled single cell sonoporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012;109:16486–16491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Borden MA, Caskey CF, Little E, Gillies RJ, Ferrara KW. DNA and Polylysine Adsorption and Multilayer Construction onto Cationic Lipid-Coated Microbubbles. Langmuir 2007;23:9401–8. doi:10.1021/la7009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nomikou N, Tiwari P, Trehan T, Gulati K, McHale AP. Studies on neutral, cationic and biotinylated cationic microbubbles in enhancing ultrasound-mediated gene delivery in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater 2012;8:1273–80. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Appis AW, Tracy MJ, Feinstein SB. Update on the safety and efficacy of commercial ultrasound contrast agents in cardiac applications. Echo Res Pract 2015;2R55–62. doi:10.1530/ERP-15-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Muskula PR, Main ML. Safety With Echocardiographic Contrast Agents. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ja’afar F, Leow CH, Garbin V, Sennoga CA, Tang M- X, Seddon JM. Surface Charge Measurement of SonoVue, Defnity and Optison: A Comparison of Laser Doppler Electrophoresis and Micro-Electrophoresis. Ultrasound Med Biol 2015;41:2990–3000. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rayleigh JWS. The theory of sound. London: Macmillan; 1894. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hoff L Acoustic Characterization of Contrast Agents for Medical Ultrasound Imaging. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2001. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-0613-1. [Google Scholar]

- [43].van der Meer SM, Dollet B, Voormolen MM, Chin CT, Bouakaz A, de Jong N, et al. Microbubble spectroscopy of ultrasound contrast agents. J Acoust Soc Am 2007;121:648–56. doi:10.1121/1.2390673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Segers T, Lohse D, Versluis M, Frinking P. Universal Equations for the Coalescence Probability and Long-Term Size Stability of Phospholipid-Coated Monodisperse Microbubbles Formed by Flow Focusing. Langmuir 2017;33:10329–39. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Israelachvili JN. Intermolecular and Surface Forces: Revised Third Edition Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tabor RF, Wu C, Grieser F, Dagastine RR, Chan DYC. Measurement of the Hydrophobic Force in a Soft Matter System. J Phys Chem Lett 2013;4:3872–7. doi:10.1021/jz402068k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Valle-Delgado JJ, Molina-Bolívar JA, Galisteo-González F, Gálvez-Ruiz MJ. Evidence of hydration forces between proteins. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 2011;16:572–8. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2011.04.004. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Klibanov AL. Ultrasound Contrast Agents: Development of the Field and Current Status. In: Krause PDW, editor. Contrast Agents II, Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2002, p. 73–106. doi:10.1007/3-540-46009-8_3. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Janssen BJC, Huizinga EG, Raaijmakers HCA, Roos A, Daha MR, Nilsson-Ekdahl K, et al. Structures of complement component C3 provide insights into the function and evolution of immunity. Nature 2005;437:505–11. doi:10.1038/nature04005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Postema M, Marmottant P, Lancée CT, Hilgenfeldt S, de Jong N. Ultrasound-induced microbubble coalescence. Ultrasound Med Biol 2004;30:1337–44. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Segers T, de Rond L, de Jong N, Borden MA, Versluis M. On the stability of monodisperse phospholipid-coated microbubbles formed by flow-focusing at high production rates. Langmuir ACS J Surf Colloids 2016. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Epstein PS, Plesset MS. On the Stability of Gas Bubbles in Liquid-Gas Solutions. J Chem Phys 1950; 18:1505. doi:10.1063/1.1747520. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Duncan PB, Needham D. Test of the Epstein-Plesset model for gas microparticle dissolution in aqueous media: effect of surface tension and gas undersaturation in solution. Langmuir ACS J Surf Colloids 2004;20:2567–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kwan JJ, Borden MA. Microbubble dissolution in a multigas environment. Langmuir ACS J Surf Colloids 2010;26:6542–8. doi:10.1021/la904088p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kwan JJ, Borden MA. Lipid monolayer dilatational mechanics during microbubble gas exchange. Soft Matter 2012;8:4756–66. doi:10.1039/C2SM07437K. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kim DH, Costello MJ, Duncan PB, Needham D. Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Polycrystalline Phospholipid Monolayer Shells: Novel Solid Microparticles. Langmuir 2003;19:8455–66. doi:10.1021/la034779c. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kabalnov A, Klein D, Pelura T, Schutt E, Weers J. Dissolution of multicomponent microbubbles in the bloodstream: 1. theory. Ultrasound Med Biol 1998;24:739–49. doi:10.1016/S0301-5629(98)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kwan JJ, Kaya M, Borden MA, Dayton PA. Theranostic Oxygen Delivery Using Ultrasound and Microbubbles. Theranostics 2012;2:1174–84. doi:10.7150/thno.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Borden MA, Longo ML. Dissolution Behavior of Lipid Monolayer-Coated, Air-Filled Microbubbles: Effect of Lipid Hydrophobic Chain Length. Langmuir 2002;18:9225–33. doi: 10.1021/la026082h. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Katiyar A, Sarkar K, Jain P. Effects of encapsulation elasticity on the stability of an encapsulated microbubble. J Colloid Interface Sci 2009;336:519–25. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Thomas AN, Borden MA. Hydrostatic Pressurization of Lung Surfactant Microbubbles: Observation of a Strain-Rate Dependent Elasticity. Langmuir 2017;33:13699–707. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b03307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Paul S, Katiyar A, Sarkar K, Chatterjee D, Shi WT, Forsberg F. Material characterization of the encapsulation of an ultrasound contrast microbubble and its subharmonic response: Strain-softening interfacial elasticity model. J Acoust Soc Am 2010;127:3846–57. doi:10.1121/1.3418685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kwan JJ, Borden MA. Lipid monolayer collapse and microbubble stability. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2012;183:82–99. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Borden MA, Longo ML. Oxygen Permeability of Fully Condensed Lipid Monolayers. J Phys Chem B 2004;108:6009–16. doi:10.1021/jp037815p. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Christiansen C, Kryvi H, Sontum PC, Skotland T. Physical and biochemical characterization of Albunex, a new ultrasound contrast agent consisting of air-filled albumin microspheres suspended in a solution of human albumin. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 1994;19 ( Pt 3):307–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hyvelin J- M, Gaud E, Costa M, Helbert A, Bussat P, Bettinger T, et al. Characteristics and Echogenicity of Clinical Ultrasound Contrast Agents: An In Vitro and In Vivo Comparison Study. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36:941–53. doi:10.7863/ultra.16.04059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Orsi M, Essex JW. The ELBA Force Field for Coarse-Grain Modeling of Lipid Membranes. PLOS ONE 2011;6:e28637. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lum JS, Dove JD, Murray TW, Borden MA. Single Microbubble Measurements of Lipid Monolayer Viscoelastic Properties for Small-Amplitude Oscillations. Langmuir 2016;32:9410–7. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lambert KJ, Podell SB, Jablonski EG, Hulle C, Hamilton K, Lohrmann R. Protein encapsulated insoluble gas microspheres and their preparation and use as ultrasonic imaging agents. WO1995001187A1, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Unger EC. United States Patent: 5088499 - Liposomes as contrast agents for ultrasonic imaging and methods for preparing the same. 5088499, 1992.

- [71].Schneider M CH, Bichon D FR, Bussat P FR, et al. United States Patent: 5380519 - Stable microbubbles suspensions injectable into living organisms. 5380519, 1995.

- [72].Anderson DR, Tsutsui JM, Xie F, Radio SJ, Porter TR. The role of complement in the adherence of microbubbles to dysfunctional arterial endothelium and atherosclerotic plaque. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:597–606. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Yanagisawa K, Moriyasu F, Miyahara T, Yuki M, Iijima H. Phagocytosis of ultrasound contrast agent microbubbles by Kupffer cells. Ultrasound Med Biol 2007;33:318–25. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chomas JE, Dayton P, Allen J, Morgan K, Ferrara KW. Mechanisms of contrast agent destruction. TEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2001;48:232–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Postema M, van Wamel A, Lancée CT, de Jong N. Ultrasound-induced encapsulated microbubble phenomena. Ultrasound Med Biol 2004;30:827–40. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chen CC, Borden MA. The Role of Poly(ethylene glycol) Brush Architecture in Complement Activation on Targeted Microbubble Surfaces. Biomaterials 2011;32:6579–87. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Fix SM, Nyankima AG, McSweeney MD, Tsuruta JK, Lai SK, Dayton PA. Accelerated Clearance of Ultrasound Contrast Agents Containing Polyethylene Glycol is Associated with the Generation of Anti-Polyethylene Glycol Antibodies. Ultrasound Med Biol 2018;44:1266–80. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Thomas DH, Butler M, Anderson T, Emmer M, Vos H, Borden M, et al. The “quasi-stable” lipid shelled microbubble in response to consecutive ultrasound pulses. Appl Phys Lett 2012;101:071601. doi: 10.1063/1.4746258. [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pochon S, Tardy I, Bussat P, Bettinger T, Brochot J, von Wronski M, et al. BR55: a lipopeptide-based VEGFR2-targeted ultrasound contrast agent for molecular imaging of angiogenesis. Invest Radiol 2010;45:89–95. doi:10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181c5927c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Smeenge M, Tranquart F, Mannaerts CK, de Reijke TM, van de Vijver MJ, Laguna MP, et al. First-in-Human Ultrasound Molecular Imaging With a VEGFR2-Specific Ultrasound Molecular Contrast Agent (BR55) in Prostate Cancer: A Safety and Feasibility Pilot Study. Invest Radiol 2017;52:419–27. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Willmann JK, Bonomo L, Testa AC, Rinaldi P, Rindi G, Valluru KS, et al. Ultrasound Molecular Imaging With BR55 in Patients With Breast and Ovarian Lesions: First-in-Human Results. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2133–40. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.8594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Meet Butterfly iQ - Whole body imaging, under $2k n.d. https://www.butterflynetwork.com/ (accessed June 12, 2018).

- [83].State of the Technology. Focus Ultrasound Found n.d. https://www.fusfoundation.org/the-technology/state-of-the-technology (accessed June 12, 2018).