Abstract

Chronic pain is both a global public health concern and a serious source of personal suffering for which current treatments have limited efficacy. Recently, oxylipins derived from linoleic acid (LA), the most abundantly consumed polyunsaturated fatty acid in the modern diet, have been implicated as mediators of pain in the periphery and spinal cord. However, oxidized linoleic acid derived mediators (OXLAMs) remain understudied in the brain, particularly during pain states. In this study, we employed a mouse model of chronic inflammatory pain followed by a targeted lipidomic analysis of the animals’ amygdala and periaqueductal grey (PAG) using LC-MS/MS to investigate the effect of chronic inflammatory pain on oxylipin concentrations in these two brain nuclei known to participate in pain sensation and perception. From punch biopsies of these brain nuclei, we detected twelve OXLAMs in both the PAG and amygdala and one arachidonic acid derived mediator, 15-HETE, in the amygdala only. In the amygdala, we observed an overall decrease in the concentration of the majority of OXLAMs detected, while in the PAG the concentrations of only the epoxide LA derived mediators, 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME, and one trihydroxy LA derived mediator, 9,10,11-TriHOME, were reduced. This data provides the first evidence that OXLAM concentrations in the brain are affected by chronic pain, suggesting that OXLAMs may be relevant to pain signaling and adaptation to chronic pain in pain circuits in the brain and that the current view of OXLAMs in nociception derived from studies in the periphery is incomplete.

1. Introduction

The mammalian brain has a unique and highly regulated composition of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), many of which have been implicated in diverse signaling and regulatory processes [1,2]. When studying PUFAs in the brain, emphasis has largely focused on the omega-6 PUFA arachidonic acid (AA) and the omega-3 PUFA docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), the two most abundant PUFAs in the brain, and lipid mediators synthesized from these PUFAs [2–5]. Still largely unexplored, however, is the class of oxidized lipids that are derived directly from the precursor to AA, linoleic acid (LA). LA is the most abundantly consumed PUFA in US diets [6], though its concentration in central nervous system tissue is an order of magnitude lower than AA and DHA [7,8]. Despite the relatively low abundance of LA, oxidized linoleic acid derived mediators (OXLAMs), produced non-enzymatically and by lipoxygenases (5- or 12/15-LOX), cytochrome P450 (CYP-2C,2 J, 2E, 4A, or 4F) and soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) enzymes, have been detected in the brain of rodents [9–11]. With the emergence of increasingly sensitive analytical techniques for targeted lipidomic analysis, oxylipins present in various tissue at much smaller concentrations may be explored in a subregion specific way.

In the periphery, several OXLAMs have been implicated in nociception, usually having pro-nociceptive effects [11–17]. For example, the hydroxy LA derivatives 9- and 13‑hydroxy‑octadecadienoic acid (9-and 13-HODE), as well as their metabolites 9- and 13-oxo-octadecadienoic acid (9- and 13-oxoODE), have been shown to be endogenous ligands of Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 1 (TRPV1) receptors involved in heat sensitivity, mechanical allodynia and pain behaviors [15,16]. Moreover, the LA derived epoxide 9,10-EpOME, implicated in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain, and the di‑hydroxy LA derived mediator 12,13-Di-HOME, implicated in inflammatory pain, have also been shown to sensitize TRPV1 receptors and induce hypersensitivity in vivo in rodents [11,17]. Our group has recently shown that epoxy-alcohol and epoxyketone LA derived mediators produced in skin are capable of sensitizing rat dorsal root ganglia neurons to release the pain relevant neuropeptide Calcitonin Gene Related Peptide (CGRP) and inducing pain and itch-related behavior in vivo in rodents [13]. Furthermore, in a small clinical trial in patients suffering from severe headache, our lab has shown that decreasing dietary LA and increasing dietary n-3 PUFAs reduced headache with headache reductions correlating with lower circulating levels of OXLAMs [13,18]. Despite the abundance of LA in US diets and a growing body of evidence highlighting the effects of OXLAMs in the periphery and spinal cord, the effects of OXLAMs in the brain, particularly with respect to nociception, remain poorly understood. However, recently data has shown that the mono‑hydroxy LA derivative 13-HODE can influence neurotransmission in the hippo-campus similarly to the well characterized, pain-inducing lipid mediator, PGE2, as evidenced by increases in paired-pulse firing in ex vivo hippocampal slices [19]. This finding in CNS tissue suggests that the effects of OXLAMs seen in the periphery on neuronal firing and signaling could also occur in the brain.

Two brain regions of interest in the study of pain are the amygdala and the periaqueductal grey (PAG). The amygdala has been extensively implicated in pain perception, emotional responses to pain and pain modulation in both humans and animal models [For review [20–22]]. The PAG has long been known to be involved in descending modulation of pain [23,24]. Pain-related plasticity in both amygdala and PAG has been demonstrated in chronic inflammatory pain models, and extensive work has been done to characterize the effects of pain states on gene expression and receptor signaling in these regions [20,25–27]. However, lipidomic changes in these regions in pain have not been characterized.

In this report we measured the concentrations of OXLAMs in the amygdala and PAG in a model of chronic inflammatory pain in mice. We employed a targeted lipidomic analysis using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to quantify the concentrations of oxylipins within the amygdala and PAG of mice following an intraarticular injection of Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA). From punch biopsies of brain tissue only approximately 2 mg in size, we were able to quantify 12 hydroxy, keto and epoxy derivatives of LA, including two recently identified epoxy-alcohols, as well as one derivative of AA, 15-HETE. Our data suggest that levels of OXLAMs within the amygdala and PAG are generally reduced in animals experiencing chronic inflammatory pain, with a greater effect seen in the amygdala. This reduction is not seen in the concentration of 15-HETE.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male C57bl/6 mice (8 weeks old on arrival; Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in our animal facility with regulated temperature and humidity on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Mice had ad libitum assess to standard rodent chow and water. All procedures were approved by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institutes of Health.

2.2. Induction of chronic inflammatory pain

To induce chronic inflammatory pain, we used a model developed in rats by Butler et al [28] which results in chronic ankle swelling and hypersensitivity peaking by 1 week post injection, stabilizing by week 2 and lasting for 6 to 8 weeks [28–30], applied in mice. Briefly, at approximately 9 to 10 weeks of age, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and an intraarticular injection was made with a 27 G needle while the ankle was maintained in plantarflexion. For the CFA treatment group (n = 27), CFA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 10 μl) was injected into the ankle. In sham animals (n = 4), the same procedure was followed but no liquid was injected into the joint. Experimenter observation confirmed that swelling and hypersensitivity (unpublished observations) developed as seen previously in rats and lasted until the time of sacrifice. Mice were left for three weeks to ensure that the inflammatory state had time to develop, stabilize and develop chronicity according to previous accounts using this model in rats [28–30].

2.3. Tissue collection

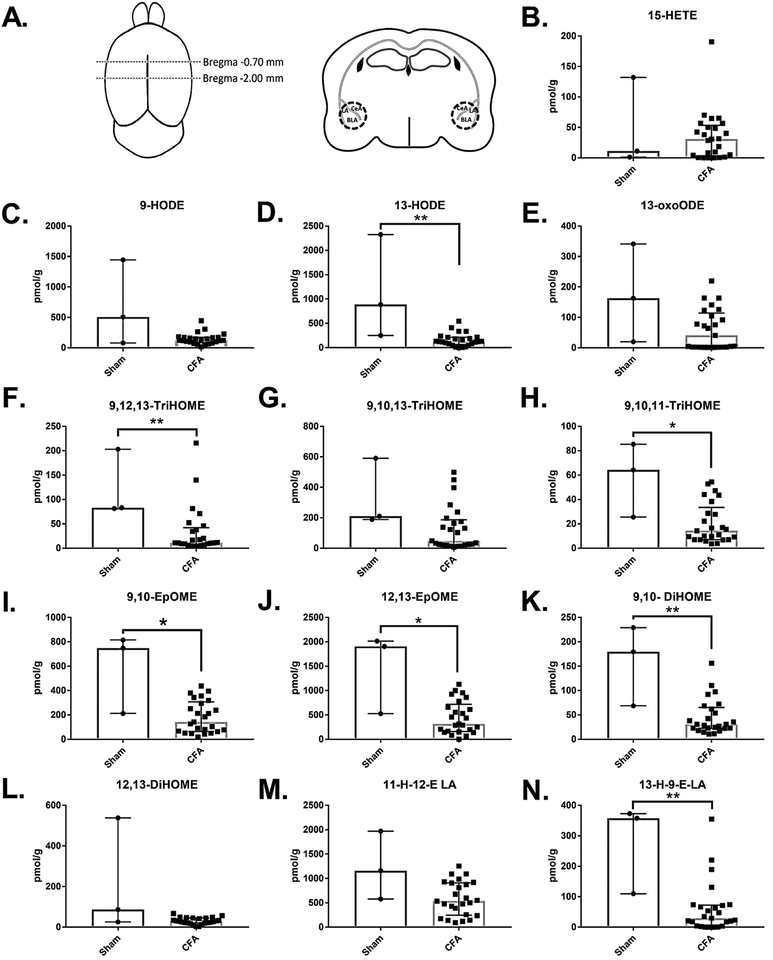

Three weeks (21–22 days) after CFA injections, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. Brains were extracted immediately and rapidly following decapitation and were sliced coronally using a brain block. Blocked sections were frozen on dry ice. The brain regions were then identified visually using anatomical landmarks (i.e. external and amygdalar capsule for the amygdala and cerebral aqueduct for the PAG) and collected using a 1 mm punch biopsy. For amygdala collection, the brain was blocked between Bregma −0.70 mm and −2.00 mm, and the amygdala was punched bilaterally (Fig. 1(A)). The ipsilateral and contralateral punches were pooled for analysis. For dissection of the PAG, the brain was blocked between Bregma −4.00 mm and −5.00 mm, and one medial punch was taken (Fig. 2(A)). Tissue punches were stored at −80 °C.

Fig. 1. Chronic inflammatory pain reduced the concentration of most OXLAMs quantified in punch biopsies of the amygdala.

A. Schematic of landmarks used during tissue collection. The brain was blocked between approximately Bregma −0.70 mm and Bregma −2.00 mm, and a 1 mm circular punch biopsy, the location of which is demarcated by the broken line, was collected bilaterally including the majority of the BLA and portions of the LA and CeA. B-N. Concentrations of AA derived (B) and LA derived (C-N) oxylipins measured in amygdala punch biopsies using LC-MS/MS reveal a statistically significant reduction in most (D, F, H-K,N) but not all oxylipins in animals experiencing chronic inflammatory pain (n = 25) compared to sham treated controls (n = 3). Individual values are displayed as pmol per gram of tissue. Bars represent median (interquartile range). P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 when comparing tissue collected from sham treated and CFA treated animals. BLA, basolateral amygdala; LA, lateral amygdala; CeA, central nucleus of the amygdala; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; oxoODE, oxooctadecadienoic acid; TriHOME, trihydroxyoctadecenoic acid; EpOME, epoxyoctadecenoic acid; DiHOME, dihydroxyoctadecenoic acid; 11-H-12-E LA,11‑hydroxy‑12,13-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid; 13-H-9-E LA, 13‑hydroxy‑9,10-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid.

Fig. 2. Chronicinflammatory pain reduced the concentration of some OXLAMs quantified in punch biopsies of the PAG.

A. Schematic of landmarks used during tissue collection. The brain was blocked between approximately Bregma −4.00 mm and Bregma −5.00 mm, and a 1 mm circular punch biopsy, the location of which is demarcated by the broken line, was taken using visual landmarks including the majority of the PAG. B-M. Concentration of OXLAMs measured in PAG punch biopsies using LC-MS/MS revealed a significant reduction in some (G-I) but not all OXLAMs in animals experiencing chronic inflammatory pain (n = 19) compared to sham treated controls (n = 3). Individual values are displayed as pmol per gram of tissue. Bars represent median (interquartile range). P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 when comparing tissue collected from sham treated and CFA treated animals. PAG, periaqueductal grey; HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; oxoODE, oxooctadecadienoic acid; TriHOME, trihydroxyoctadecenoic acid; EpOME, epoxyoctadecenoic acid; DiHOME, dihydroxyoctadecenoic acid; 11-H-12-E LA, 11‑hydroxy, 11‑hydroxy‑12,13-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid; 13-H-9-E LA, 13‑hydroxy‑9,10-trans-epoxyoctadecenoic acid.

2.4. Tissue preparation and lipid extraction

Samples of amygdala and PAG were transferred to 2 mL micro-centrifuge tubes filled with ceramic beads (Percellys Lysing Kit Tissue grinding CKMix50; Bertin Technologies) on dry ice. At least eight times greater volume of ice cold methanol containing 0.02% (v/v) BHT and0.02% (v/v) EDTA was added along with deuterated oxylipin internal standards containing equal amounts of 13-HODE-d4, Thromboxane B2-d4 (TXB2-D4), Leukotriene B4-d4 (LTB4-D4), PGE2-d4, 5-Hydroxy-Eicosatetraenoic acid-d8 (5-HETE-D8), 15-Hydroxy-Eicosatetraenoic acid-d8 (15-HETE-D8) and Lipoxin A4-d5 (LXA4-D5). Tissues were homogenized using a Percellys Cryolys bead homogenizer with temperature maintained between 0 and 6 °C using the soft tissue setting (2 cycles @ 5800 RPM for 15 s with 30 s break). The resulting homogenate was stored at −80 °C for 1 h to precipitate proteins. Samples were then centrifuged at 17,000 g and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and stored overnight at −80 °C in microcentrifuge tubes filled with nitrogen gas.

2.5. Solid phase extraction

Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) was performed to isolate the oxylipins prior to LC-MS/MS as modified from a previously described method developed by our group [13,31,32]. Briefly, SPE was performed using Strata × cartridges (33 u, 200 mg/6 ml; Phenomenex). The columns were conditioned using 6 ml of methanol followed by 6 ml of water. Samples were mixed with at least 12 times their volume of ice cold water and loaded onto the column. The columns were then rinsed with 10% methanol, dried with a vacuum (approximately 200 mmHg) for 2 min and eluted with methanol containing 0.0004% (v/v) BHT into a glass culture tube containing 10 μL 30% glycerol in methanol. The resulting eluate was dried under nitrogen gas and reconstituted in HPLC grade methanol, and lipid mediators were measured by LC-MS/MS. All samples were analyzed within a week after extraction. Experimenters were blinded to group identifications throughout tissue collection and processing.

2.6. LC-MS/MS analysis

Oxylipins were identified and quantified using Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments) coupled with a QTRAP 5500 MS/MS (AB Sciex) as previously described [13,32].

2.7. Data analysis

Chromatograms were analyzed using Analyst 1.6.3 (AB Sciex). Concentrations were determined based on standard curves prepared for each analyte quantified (9-HODE, 13-HODE, 9-oxoODE, 13-oxoODE, 9,10-EpOME, 12,13-EpOME, 9,10-DiHOME, 12,13-DiHOME, 9,12,13-TriHOME, 9,10,13-TriHOME, 9,10,11-TriHOME. 9-HOTrE, PGE2, PGF2a, 8-IsoPGF2a, TXB2, LTB4, LXA4, 5-HETE, 12-HETE, 15-HETE, 5-oxoETE, 18-HEPE, 4-HDHA, 7-HDHA, 10-HDHA, 14-HDHA, 17-HDHA, 10,17-DiHDHA, PD1, MaR1, RvD1, 16,17-EDP, 19(20)-EDP, 9-H-12-ELA, 11-H-12-E-LA, 11-H-9-E-LA, 13-H-9-E-LA, 9-K-12-E-LA, 11-K-12-ELA, 11-K-9-E-LA, and 13-K-9-E-LA), correcting for recovery of internal standards (see [32] for information about the internal standard used for each analyte). Calculated analyte concentrations are reported as pmol of oxylipin per gram of tissue.

Oxylipin peaks with a signal to noise ratio of less than 6 were not quantified and considered below the limit of quantification (BLQ). For each oxylipin, the least concentrated standard (or sample if concentration was lower than the lowest standard) above this signal to noise ratio was defined as the limit of quantification (LOQ). Peaks that were BLQ were imputed as one half of the LOQ for that analyte. Oxylipins in which greater than 50% of the samples were BLQ were not reported.

Oxylipin concentrations were compared between CFA and Sham treated animals in each brain region using an unmatched Mann-Whitney U test (GraphPad Prism 7.0, La Jolla, CA). The final number of quantifiable samples (n = 3 for the PAG and amygdala of sham treated controls, n = 19 for PAG of CFA treated mice and n = 25 for the amygdala of CFA treated mice) was reduced due to sample loss during tissue collection and sample preparation. Data are presented as median (interquartile range). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Oxylipin concentrations in the amygdala

We quantified oxylipins in punches of the amygdala (average mass2.39 mg [± 1.28 mg]), using a LC/MS-MS targeted lipidomic approach. We aimed to measure concentrations of 18 LA metabolites, 11 AA metabolites, one Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) metabolite, and 11 DHA metabolites. Of these, we were able to detect 12 LA metabolites and one AA metabolite in the amygdala (Fig. 1).

The concentration of the monohydroxy LA metabolite 13-HODE, in the amygdala was approximately 7-fold lower [p = 0.0067] in animals injected with CFA [125.8 (63.85–214.7) pmol/g] than in sham treated animals [885.8 (251.5–2326) pmol/g], while the concentration of 9-HODE and the ketone derivative of 13-HODE, 13-oxoODE, were not significantly different between groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1(C-E)). The ketone derivative of 9-HODE (9-oxoODE) was below the limit of quantification in >50% of samples and not reported. The concentrations of epoxy LA derived mediators (9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME) were significantly lower [p = 0.0409 for both] in amygdala of mice treated with CFA [142 (64.9–307.3) and 312.7 (158.8–719.5) pmol/g for 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME, respectively] as compared to controls [747.7 (212.2–815.5) pmol/g and 1906 (525.6–2015) pmol/g for 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME, respectively] (Fig. 1(I-J)). The di‑hydroxy lipid mediator derived from LA, 9,10-DiHOME was almost 6-fold more concentrated [p = 0.0098] in control animals’ amygdala [179.7(68.76–229.1) pmol/g] compared to CFA treated animals [30.66(22.63–65.31) pmol/g], while the di‑hydroxy mediator 12,13-DiHOME was not different between groups (Fig. 1(K-L)). The tri‑hydroxy LA derived mediators 9,12,13-TriHOME and 9,10,11-TriHOME were significantly more concentrated [p = 0.0098 and p = 0.0250 for 9,12,13-TriHOME and 9,10,11-TriHOME, respectively] in sham treated mice’s amygdala [83.33 (81.46–203.1) and 64.24 (25.59–85.30) pmol/g for 9,12,13-TriHOME and 9,10,11-TriHOME, respectively) compared to CFA treated animals [11.2 (7.844–41.92) and 14.29 (7.04–33.57) pmol/g for 9,12,13-TriHOME and 9,10,11-TriHOME, respectively], while the tri‑hydroxy LA derived mediator 9,10,13-TriHOME was trending [p = 0.0507] to be higher in the amygdala of sham treated animals [210.5 (189.5–590.6) pmol/g] compared to CFA treated mice[48.58 (21.63–186.1) pmol/g] (Fig. 1(F–H)). Similarly, the hydroxy‑ epoxy- LA metabolite 13-H-9-E LA was elevated [p = 0.0067] while 11-H-12-E LA was trending [p = 0.0623] to be elevated in controls [1159 (579.1–1973) and 357.8 (110.1–372.7) pmol/g for 11-H-12-E LA and 13-H-9-E LA, respectively) compared to CFA treated animals [537.1 (247.4–911.9) and 29.6 (3.866–72.55) pmol/g for 11-H-12-E LA and 13-H-9-E LA, respectively] (Fig. 1(M-N)). The other OXLAMs were BLQ.

All metabolites derived from AA except for 15-HETE were BLQ in the amygdala. 15-HETE was approximately 3-fold higher in the amygdala of animals injected with CFA [30.83 (2.794–53.42) pmol/g] than controls [11.08 (1.248–132) pmol/g], though this elevation was not statistically significant [p = 0.9393] (Fig. 1(B)).

All lipid mediators derived from DHA or EPA that we aimed to measure were BLQ.

3.2. Oxylipin concentrations in the PAG

In punch biopsies of the PAG (average mass 1.52 mg [± 0.93 mg]), the concentration of all mono-, di-, and tri‑hydroxy LA metabolites measured were not significantly affected by intraarticular CFA injection [p > 0.05], with the exception of 9,10,11-TriHOME which was significantly lower in CFA treated animals [36.19 (13.58–65.14) pmol/g] than controls [98.84(81.27–103) pmol/g, p = 0.0052] (Fig. 2(B-C), (E–G), and (J-K)). Both epoxy- LA metabolites (9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME) were approximately 2-fold less concentrated [p = 0.0299 and p = 0.0403 for 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME respectively] in the PAG of CFA treated animals [343.1 (162.0–509.5) and 832.4 (382.9–1274) pmol/g for 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME, respectively] than in controls [717.6 (564.3–1079) pmol/g and 1629 (1600–2895) pmol/g for 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME, respectively] (Fig. 2(H-I)). 13-oxoODE, 13-H-9-E LA, and 11-H-12-E LA were not significantly different between the groups [p > 0.05] (Fig. 2(D) and (L-M)). No other OXLAMs were above the LOQ.

All AA, DHA, and EPA metabolites that we aimed to measure were BLQ in the PAG.

4. Discussion and conclusions

In this report we measured the concentrations of oxylipins in punch biopsies of the amygdala and PAG in a mouse model of chronic inflammatory pain. Most of the mediators derived from AA and all mediators derived from DHA and EPA that we attempted to quantify were below our limit of detection. However, we were able to detect and quantify twelve LA metabolites in both tissues and one AA metabolite, 15-HETE, in the amygdala. Interestingly, many of the OXLAMs quantified were less concentrated in the amygdala of animals experiencing chronic inflammatory pain than in sham treated controls. No such reduction was seen in the concentration of 15-HETE, the only mediator not derived from LA that we were able to measure, although in most samples 15-HETE concentration was outside the linear range of the standard curve (Fig. 1). A similar trend was seen in the PAG, although the effect was less pronounced, and only the concentrations of 9,10-EpOME, 12,13-EpOME, and 9,10,11-TriHOME were significantly reduced in the PAG of CFA treated animals (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 3. Diagram of oxylipin synthesis from linoleic acid summarizing current findings.

Three weeks of chronic inflammatory pain affected the concentration of OXLAMs in multiple synthetic pathways in the amygdala, with the largest reduction in the concentration of 13-HODE relative to the mean concentration in sham treated controls. The oxylipin lowering effect of the chronic inflammatory pain model was limited to the epoxygenation products of LA in the PAG, with the exception of 9,10,11-TriHOME which was also the most reduced relative to the sham treated controls. OXLAM species shaded light grey highlight species with lower concentrations in the amygdala of CFA treated animals, while species shaded dark grey highlight species with lower concentrations in both the amygdala and PAG in this group. HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; oxoODE, oxooctadecadienoic acid; TriHOME, trihydroxyoctadecenoic acid; EpOME, epoxyoctadecenoic acid; DiHOME, dihydroxyoctadecenoic acid; 11-H-12-E LA,11‑hydroxy‑12,13-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid; 13-H-9-E LA, 13‑hydroxy‑9,10-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid.

The observed lower OXLAM concentrations in the amygdala and PAG of mice experiencing chronic inflammatory pain was surprising. Lipidomic analyses of peripheral tissues, dorsal root ganglia (DRG), trigeminal ganglia (TG) and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord in animal models of inflammatory pain have revealed concentration increases in several OXLAMs, including mono‑hydroxy (9- and 13-HODE), keto (9-and 13-oxoODE), di‑hydroxy (12,13-DiHOME), epoxy-keto and epoxy-alcohol derivatives of LA [13,16,17]. Furthermore, increased production of OXLAMs in peripheral tissues and sensory ganglia has also been detected in heat and burn related pain (particularly 9- and 13-HODE and 9- and 13-oxoODE) and in chemotherapy induced neuropathic pain (particularly 9,10-EpOME) [11,15,33]. Additionally, higher concentrations of some of these OXLAMs have been measured in psoriatic human skin and inflamed human dental pulp [31,34]. Importantly, these OXLAMs have been shown to activate and/or sensitize neurons at these sites and to promote nociception in vivo [11–17,33–35]. Based on the agreeance across several pain models in the periphery, increased OXLAM concentrations were expected in the brain. Our results suggest that the reverse effect may occur in brain regions involved in processing pain sensory stimuli and controlling pain sensation in this mouse model of chronic inflammatory pain. It should, however, be noted that brains were collected 3 weeks after the initial insult with CFA, and it is, therefore, possible that at a timepoint earlier in the time course of the model OXLAM concentrations may be higher. Another important note is that lower OXLAM concentrations may not be limited to pain-relevant brain regions in this model, and observed concentration differences may represent a global reduction in OXLAM concentrations in brain tissue rather than a circuit-specific effect.

The observed lower OXLAM concentrations in chronic pain can be partially explained, however, by the results from a recent transcriptomic study where authors found reduced expression of Cyp2e1, a gene encoding an LA epoxygenase CYP2e1, in the PAG, nucleus accumbens, and medial prefrontal cortex (all three regions studied) in a model of chronic neuropathic pain in mice [26]. We observed, in both the amygdala and the PAG, significantly lower concentration of the epoxide LA derived mediators, 9,10-EpOME and 12,13-EpOME. Though CYP2e1 is not traditionally acknowledged as a major epoxygenase of LA, this transcriptomic evidence, along with our findings, suggest that in the brain this metabolic pathway is suppressed in response to chronic inflammatory pain [26,36]. Further research is needed to confirm that LA epoxidation is indeed suppressed and to characterize the time course and functional significance of this suppression, as well as to explore the effects of chronic pain on enzymes involved in OXLAM synthesis in the amygdala.

A notable achievement of this report was our ability to measure concentrations of unesterified OXLAMs in very small tissue samples, averaging 1.98 mg and including samples as small as 0.18 mg, collected from functional and anatomically defined brain regions. Understanding lipid metabolism in distinct brain regions is an important step toward understanding the functional role of oxylipins in the brain. Furthermore, improving the spatial resolution of lipidomic analysis could potentially reveal subregion specific differences that can be masked in whole brain or larger regional analyses. In support of this, Lerner et al (2018) simultaneously performed lipidomic and transcriptomic analysis in mouse brain punches ranging from 0.4 to 1.9 mg in size. These authors found changes in phospholipid composition after seizure in the dorsal and ventral subregions of the hippocampus that were undetected when the whole hippocampus was analyzed [37]. As methods for detection of oxylipins continue to improve in sensitivity, refinement of the spatial resolution in lipidomic analyses in the brain and other functionally subdivided organs can provide insights into the role of lipid mediators in physiology and pathology.

In addition to OXLAMs previously detected in the rodent brain, we were also able to detect two novel, hydroxy‑ epoxy- LA derived mediators, 11-H-12-E LA and 13-H-9-E LA, that have not been previously reported in brain tissue. Recently, a report from our laboratory identified these OXLAMs in the skin of rodents and humans, finding that both these compounds were abundant in inflamed skin. We also found that 11-H-12-E LA was capable of sensitizing nociceptors in the dorsal root ganglia and eliciting pain-related behavior in vivo. Furthermore, plasma concentrations of 11-H-12-E LA were inversely corelated with clinical pain reductions in a small clinical trial manipulating LA and omega-3 PUFAs in the diet in people suffering from chronic daily headache [13]. Interestingly, this compound was highly concentrated in mouse brain samples measured here, but, in contrast to 13-H-9-E LA, was not significantly less concentrated in the amygdala of CFA treated animals (Fig. 1(M-N)). Further investigation is warranted to confirm the presence and relative concentrations of hydroxy‑ epoxy- LA derived mediators in the brain of rodents and humans.

This study had several limitations. Most importantly, the number of animals in the control group limits the reliability and interpretability of our results in a number of ways [38]. Firstly, the small sample size reduced our ability to detect differences between the groups, resulting in a low power (below 60% for all analytes). Secondly, it limits the generalizability of the statistically significant differences we were able to detect despite the low power. This necessitates further research to confirm these results. Additionally, it should be noted, particularly in the control group, that the small sample size and high variability in OXLAM concentrations limits our ability to accurately estimate the absolute concentrations of OXLAMs in this group, therefore, concentrations reported here are likely best interpreted as semi-quantitative and not absolute. Future studies with larger sample sizes are required to determine the absolute concentrations of the lipid mediators presented here in these tissues. It should be stressed, considering this, that the relative differences between the groups are still likely valid.

Additionally, with the exception of 15-HETE, we were able to detect only oxylipins derived from LA. This is surprising considering that LA is far less concentrated in the brain than AA and DHA, whose metabolites we were unable to detect [8]. Moreover, Taha et al. reported in 2016 that AA derived mediators were more highly concentrated in the rat brain than LA derived mediators [10]. However, whether the relative concentration of oxylipins is completely consistent with the concentration of their precursors is not agreed upon [9] and others have reported largely similar concentrations of metabolites from each precursor fatty acid, particularly in microwave fixed tissue [19]. Notably, our method for analyzing lipid mediators was optimized for quantification of OXLAMs, particularly epoxy alcohols, perhaps accounting for the improved detection of OXLAMs compared to other lipid mediators[32]. Method optimization may be especially important considering the small mass of our samples.

Lastly, detected concentrations, normalized by the mass of the sample, were significantly higher than normalized concentrations of OXLAMs reported in the past in the cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus and brain stem of rats [10,19]. Several possibilities can explain the high concentrations of OXLAMs in this report. During tissue collection we did not perform microwave fixation which would likely result in increased oxylipin concentrations, though others also do not routinely perform microwave fixation [19]. The lack of microwave fixation would likely be particularly relevant for this study as the concentration raising effect is thought to be mediated by hypoxia to which small punches with high relative surface area may be more susceptible. Conversely, the small tissue size used in this report may have allowed us to achieve a more efficient lipid mediator extraction than previous reports. Moreover, it is conceivable that species differences in the concentrations of oxylipins exist between mice and rats or that oxylipin concentrations vary between brain regions, particularly between large brain regions rich in white matter and brain nuclei predominately composed of grey matter. However, it should be stressed that in this study all samples were processed in the same manner and experimenters were blinded to the experimental groups throughout the tissue processing and data analysis, and, therefore, comparisons between groups in this study are likely unaffected by this limitations.

The results reported here are novel but merit confirmation and further exploration due to the several limitations of our study. Future studies should aim to confirm the lower OXLAM concentrations detected in the amygdala and PAG and see if they are consistent across models of chronic pain, the time course of chronic pain, species, and nuclei within the pain circuit. Future research should also explore whether the effects seen are specific to nuclei in the pain circuit or represent a more generalized reduction in OXLAM concentrations in the whole brain. Additionally, improving detection of multiple classes of oxylipins in the same small sample of tissue will also provide information about the specificity of this effect to OXLAMs, which is suggested in our results by the unchanged concentration of 15-HETE. The origin of OXLAMs in the brain is another important area of future research, particularly considering the low concentration of the precursor to OXLAMs, LA, in the brain [7,8]. While it is possible that some OXLAMs are synthesized in the brain, it is likely that the OXLAMs measured here were synthesized in the periphery, where LA and many of the enzymes involved in their synthesis are more concentrated, and entered the brain via circulation. However, the ability of OXLAMs to enter the brain from circulation has not been demonstrated in vivo. Therefore, future research should aim to determine whether OXLAMs found in the brain originate centrally or in the periphery. Moreover, the specific cell types that synthesize OXLAMs are not agreed upon, particularly in the central nervous system; however, with the rapid spread of single cell RNA sequencing, we expect this question will be answered in the near future. Future studies should also explore the role of unesterified OXLAMs in intra- and intercellular signaling in pain related brain circuits and in the brain as a whole. The presence of these compounds, the suppression of their concentration during chronic pain, and the demonstrated bioactivity of some of them in the peripheral nervous system, spinal cord dorsal horn and the hippocampus suggest that they may play a signaling role in pain circuits [13,15,16,19].

Chronic pain is both a significant source of suffering for the individuals it affects and a significant global health concern [39]. Despite a growing body of evidence suggesting that OXLAMs participate in nociceptive signaling in the periphery [11–14,17], little is known about the effects of chronic pain on synthesis of OXLAMs in the brain or the role of OXLAMs in central pain processing and adaptation to chronic pain. A major limitation in answering these questions has been limits to the detection of OXLAMs in functional nuclei of the brain in model species. In this report, we were able to detect 12 species of OXLAMs, including two that have not been previously detected in the brain, in murine brain nuclei involved in pain perception, the amygdala and PAG, in a model of chronic inflammatory pain. In mice experiencing chronic inflammatory pain we detected an overall reduction in most unesterified OXLAMs measured in the amygdala, an effect not seen in the one AA metabolite detected, 15-HETE. The same trend was seen in the PAG but to a lesser magnitude. These data provide the first look into the potential effects of chronic pain on OXLAM concentrations in the brain and reveals that the view of OXLAMs in nociception is incomplete. Understanding changes that occur in OXLAM concentrations in pain relevant brain nuclei could advance our knowledge of the role of OXLAMs in chronic pain beyond the periphery and inform development of therapeutic interventions, both pharmaceutical and dietary, targeting OXLAM synthesis or signaling to treat pain. This study also highlights the values and challenges of studying oxylipins with greater spatial resolution within the brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Programs of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, and the Clinical Center Department of Perioperative Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- OXLAM

oxidized LA derived mediator

- CFA

Complete Freund’s Adjuvant

- PAG

Periaqueductal grey

- LA

linoleic acid

- AA

Arachidonic acid

- DHA

Docosahexaenoic acid

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- HETE

Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- HODE

Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

- OxoODE

Oxooctadecadienoic acid

- TriHOME

Trihydroxyoctadecenoic acid

- EpOME

epoxyoctadecenoic acid

- DiHOME

Dihydroxyoctadecenoic acid

- 11-H-12-E LA

11‑hydroxy‑12,13-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid

- 13-H-9-E LA

13‑hydroxy‑9,10-trans-epoxy-octadecenoic acid

References

- [1].Bazinet RP, Layé S, Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 15 (2014) 771–785, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chen CT, Green JT, Orr SK, Bazinet RP, Regulation of brain polyunsaturated fatty acid uptake and turnover, Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 79 (2008) 85–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Phospholipase A2-generated lipid mediators in the brain: the good, the bad, and the ugly, Neuroscientist 12 (2006) 245–260, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858405285923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chang C-Y, Ke D-S, Chen J-Y, Essential fatty acids and human brain, Acta Neurol. Taiwan 18 (2009) 231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Haag M, Essential fatty acids and the brain, Can. J. Psychiatry 48 (2003) 195–203, https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370304800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Blasbalg TL, Hibbeln JR, Ramsden CE, Majchrzak SF, Rawlings RR, Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 93 (2011) 950–962, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Taha AY, Basselin M, Ramadan E, Modi HR, Rapoport SI, Cheon Y, Altered lipid concentrations of liver, heart and plasma but not brain in HIV-1 transgenic rats, Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 87 (2012) 91–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lozada LE, Desai A, Kevala K, Lee J-W, Kim H-Y, Perinatal brain docosahexaenoic acid concentration has a lasting impact on cognition in mice, J. Nutr 147 (2017) 1624–1630, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.117.254607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gabbs M, Leng S, Devassy JG, Monirujjaman M, Aukema HM, Advances in our understanding of oxylipins derived from dietary PUFAs, Adv. Nutr 6 (2015) 513–540, https://doi.org/10.3945/an.114.007732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Taha AY, Hennebelle M, Yang J, Zamora D, Rapoport SI, Hammock BD, et al. , Regulation of rat plasma and cerebral cortex oxylipin concentrations with increasing levels of dietary linoleic acid, Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids (2016), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sisignano M, Angioni C, Park C-K, Meyer Dos Santos S, Jordan H, Kuzikov M, et al. , Targeting CYP2J to reduce paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathic pain, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113 (2016) 12544–12549, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1613246113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hargreaves KM, Ruparel S, Role of oxidized lipids and TRP channels in orofacial pain and inflammation, J. Dent. Res 95 (2016) 1117–1123, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516653751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ramsden CE, Domenichiello AF, Yuan Z-X, Sapio MR, Keyes GS, Mishra SK, et al. , A systems approach for discovering linoleic acid derivatives that potentially mediate pain and itch, Sci. Signal (2017) 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aal5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shapiro H, Singer P, Ariel A, Beyond the classic eicosanoids: peripherally-acting oxygenated metabolites of polyunsaturated fatty acids mediate pain associated with tissue injury and inflammation, Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 111 (2016) 45–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Patwardhan AM, Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Weintraub ST,Uhlson C, et al. , Heat generates oxidized linoleic acid metabolites that activate TRPV1 and produce pain in rodents, J. Clin. Invest 120 (2010) 1617–1626, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI41678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Patwardhan AM, Scotland PE, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM, Activation of TRPV1 in the spinal cord by oxidized linoleic acid metabolites contributes to in-flammatory hyperalgesia, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106 (2009) 18820–18824, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zimmer B, Angioni C, Osthues T, Toewe A, Thomas D, Pierre SC, et al. , The oxidized linoleic acid metabolite 12,13-DiHOME mediates thermal hyperalgesia during inflammatory pain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863 (2018) 669–678, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ramsden CE, Faurot KR, Zamora D, Suchindran CM, Macintosh BA,Gaylord S, et al. , Targeted alteration of dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids for the treatment of chronic headaches: a randomized trial, Pain 154 (2013) 2441–2451, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hennebelle M, Zhang Z, Metherel AH, Kitson AP, Otoki Y, Richardson CE, et al. , Linoleic acid participates in the response to ischemic brain injury through oxidized metabolites that regulate neurotransmission, Sci. Rep 7 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02914-74342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Neugebauer V, Amygdala pain mechanisms, Handb. Exp. Pharmacol 227 (2015) 261–284, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-46450-2_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Veinante P, Yalcin I, Barrot M, The amygdala between sensation and affect: a role in pain, J. Mol. Psychiatry 1 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9256-1-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thompson JM, Neugebauer V, Amygdala plasticity and pain, Pain Res. Manag 2017 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8296501)8296501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Porreca F, Ossipov MH, Gebhart GF, Chronic pain and medullary descending facilitation, Trends Neurosci 25 (2002) 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fields HL, Pain modulation: expectation, opioid analgesia and virtual pain, Prog. Brain Res 122 (2000) 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Aissouni Y, El Guerrab A, Hamieh AM, Ferrier J, Chalus M, Lemaire D, et al. , Acid-sensing ion channel 1a in the amygdala is involved in pain and anxiety-related behaviours associated with arthritis, Sci. Rep 7 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1038/srep4361743617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Descalzi G, Mitsi V, Purushothaman I, Gaspari S, Avrampou K, Loh Y-HE, et al. , Neuropathic pain promotes adaptive changes in gene expression in brain networks involved in stress and depression, Sci. Signal (2017) 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aaj1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hu J, Wang Z, Guo Y-Y, Zhang X-N, Xu Z-H, Liu S-B, et al. , A role of periaqueductal grey NR2B-containing NMDA receptor in mediating persistent inflammatory pain, Mol. Pain 5 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-5-7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Butler SH, Godefroy F, Besson JM, Weil-Fugazza J, A limited arthritic model for chronic pain studies in the rat, Pain 48 (1992) 73–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(92)90133-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Martindale JC, Wilson AW, Reeve AJ, Chessell IP, Headley PM, Chronic secondary hypersensitivity of dorsal horn neurones following inflammation of the knee joint, Pain 133 (2007) 79–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pitcher MH, Tarum F, Rauf IZ, Low LA, Bushnell C, Modest amounts of voluntary exercise reduce pain- and stress-related outcomes in a rat model of persistent hind limb inflammation, J. Pain 18 (2017) 687–701, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sorokin AV, Domenichiello AF, Dey AK, Yuan Z-X, Goyal A, Rose SM, et al. , Bioactive lipid mediator profiles in human psoriasis skin and blood, J. Invest. Dermatol (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yuan Z-X, Majchrzak-Hong S, Keyes GS, Iadarola MJ, Mannes A, Ramsden CE, Lipidomic profiling of targeted oxylipins with ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, Anal. Bioanal. Chem (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Green DP, Ruparel S, Roman L, Henry MA, Hargreaves KM, Role of endogenous TRPV1 agonists in a postburn pain model of partial-thickness injury, Pain 154 (2013) 2512–2520, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ruparel S, Hargreaves KM, Eskander M, Rowan S, de Almeida JFA, Roman L, et al. , Oxidized linoleic acid metabolite-cytochrome P450 system (OLAM-CYP) is active in biopsy samples from patients with inflammatory dental pain, Pain 154 (2013) 2363–2371, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ruparel S, Henry MA, Akopian A, Patil M, Zeldin DC, Roman L, et al. , Plasticity of cytochrome P450 isozyme expression in rat trigeminal ganglia neurons during inflammation, Pain 153 (2012) 2031–2039, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Moran JH, Mitchell LA, Bradbury JA, Qu W, Zeldin DC, Schnellmann RG, et al. , Analysis of the cytotoxic properties of linoleic acid metabolites produced by renal and hepatic P450s, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 168 (2000) 268–279, https://doi.org/10.1006/taap.2000.9053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lerner R, Post JM, Ellis SR, Vos DRN, Heeren RMA, Lutz B, et al. , Simultaneous lipidomic and transcriptomic profiling in mouse brain punches of acute epileptic seizure model compared to controls, J. Lipid Res 59 (2018) 283–297, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M080093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Faber J, Fonseca LM, How sample size influences research outcomes, Dental PressJ. Orthod 19 (2014) 27–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Institute of Medicine (US), Committee On Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education, Relieving pain in America: A blueprint For Transforming prevention, care, education, and Research, National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC), 2011, https://doi.org/10.17226/13172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]