Abstract

X chromosome inactivation silences one X chromosome in female mammals. However, this silencing is incomplete, and some genes escape X inactivation. We describe methods to determine the chromosome- wide X inactivation status of genes in tissues or cell lines derived from mice using a combination of skewing of X inactivation and allele-specific analyses of gene expression based on RNA-seq.

Keywords: Allelic gene expression, X inactivation, Escape from X inactivation

1. Introduction

The mammalian X chromosome is regulated by mechanisms that evolved due to the fundamental difference in the number of X chromosomes between males (XY) and females (XX). These mechanisms restore a balanced expression between X and autosomes (X up-regulation) and between the sexes (X inactivation or XCI) [1]. XCI leads to silencing of one whole X chromosome in females, yet some genes escape this silencing and thus remain biallelically expressed.

We and others determined that about 15% and 3% of human and mouse X-linked genes escape XCI, respectively [2, 3]. Genes located in the pseudoautosomal region (PAR) of the sex chromo-somes usually escape XCI [4]; in addition, a subset of conserved dosage-sensitive X-linked genes with Y-linked paralogs located outside of the PAR consistently escape XCI [5, 6]. Other escape genes, called “variable escape genes” or “facultative escape genes” show variability between tissues, cell types, and/or between female individuals in terms of expression from the inactive X chromosome [7–9]. Genes that escape XCI are usually more highly expressed in females, which causes a sex-bias in gene expression [1, 7]. Mutations in genes that escape XCI can cause human diseases in both males and females [10].

In this chapter we describe methods we have used to identify genes subject to XCI and genes that escape XCI in mouse. XCI is random in most somatic tissues—i.e., either the paternal or the maternal allele is inactivated in each cell of early mammalian embryos [11]. Silencing of one allele is subsequently faithfully transmitted to daughter cells, which results in a mosaic pattern in mammalian females [12]. Thus, the first step necessary to measure allelic expression in bulk cells or tissues by molecular means such as RNA-seq is to develop systems in which XCI is skewed. Such systems may naturally occur, as in extraembryonic tissues of the mouse where the paternal X chromosome is specifically inactivated. Indeed, patterns of XCI and escape from XCI have been determined in trophoblastic cells [13–15]. However, in the embryo proper and in adult tissues or in cell lines derived from tissues, XCI skewing needs to be induced by cell cloning or by using mutations. For example, an Xist mutation causes the mutant X chromosome to remain active because Xist is essential for the onset of XCI [16]. Another example is the use of an Hprt mutation, which can be selected against in cell culture—favoring the normal allele—by growing cells in HAT (hypoxanthine–aminopterin–thymidine) media [17].

An essential premise of molecular analysis of allelic expression based on sequencing is an efficient way to differentiate alleles. Sequencing methods such as RNA-seq should be performed using systems in which the frequency of SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) is sufficient to distinguish alleles at multiple loci. Maximizing the level of allelic differences in mouse can be achieved by mating different mouse strains or species, for example, by crossing the laboratory mouse Mus musculus to wild-derived Mus spretus or Mus castaneus, to attain SNP density of 1/75 bp or 1/121 bp, respectively. In human, mouse-human hybrid cells selected to retain either an inactive or an active human X chromosome were initially used to catalog escape genes, which removes the need to differentiate alleles [2]. This study showed that expression of an escape gene on the inactive X chromosome is highly variable, ranging from a few percent to 50%, and rarely reaching 75% of the expression on the active X allele [2]. In addition, one should keep in mind that escape from XCI varies between cell types, tissues and individuals both in human and mouse [18, 19].

Single-cell RNA-seq has opened up alternative approaches to measuring allelic expression without the need of XCI skewing [20, 21]. These approaches work best for well-expressed genes, as allelic expression of low-expressed genes in single cells can be obscured by technical noise including variable capture efficiency and random allele dropout [22]. Another approach is RNA-FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) for the detection of nascent transcripts in individual nuclei. This method offers the advantage of examining cells in situ without the need of SNPs, thus potentially allowing for identification of cell types within a tissue [23]. However, RNA-FISH is dependent on robust expression of the gene of interest, and cannot easily be used to concurrently examine multiple genes. While the probability of escape can be evaluated at the single-cell level by counting cells with one or two signals, quantification of allelic expression levels is not possible by RNA-FISH. An additional in situ approach is to label each allele of an expressed X-linked gene with a different color tag to visualize the distribution of allelic expression, which also allows for purifying cells with skewed XCI by flow-sorting [24]. However, this method requires engineering the gene of interest with color reporter sequences. Newer methods promise to assess the transcriptome in situ (e.g., FISSEQ), but have not been applied to allelic expression analyses [25].

Indirect approaches to determine the XCI status of genes rely on examining their characteristic epigenetic marks, for example, DNA methylation or histone modifications. One such approach takes advantage of allele-specific methylation patterns on X-linked genes: silenced genes are usually methylated at their promoter CpG island, while escape genes lack such methylation [26–28]. Non-CpG methylation also marks the bodies of genes that escape XCI specifically in neuronal tissues [29, 30]. Other epigenetic modifications such as H3K27me3 and macroH2a are depleted at escape genes [3, 13, 31].

Here, we describe our approaches based on analyses of mouse hybrid cell lines and tissues using RNA-seq followed by mapping and quantifying reads from each allele identified by SNPs. We applied these approaches to the study of XCI and escape from XCI in multiple mouse tissues to test allele-specific expression in F1 mice resulting from crosses between laboratory strain BL/6 mice and M. spretus, in which XCI was skewed [19]. The method is applicable to the analysis of autosomal genes, including imprinted genes and genes with random monoallelic expression (provided that either cell clones or single cells are used). The approach described is also relevant for human studies, but in this case fewer SNPs are available and skewed XCI rarely occurs naturally so that again, RNA-seq on cell clones or single cells would be appropriate.

2. Materials

2.1. In Vivo Mouse Model

C57BL6/J breeder mice from Jackson Laboratory (JAX™ Mice Stock Number 000664).

Mus spretus (wild-derived inbred strain SPRET/Ei) breeder mice from Jackson Laboratory (JAX™ Mice Stock Number 001146).

DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen #9504).

Taq DNA polymerase Promega #M5005.

RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen #74104).

Reverse transcriptase SuperScriptII (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific #18064014).

QIAquick standard/MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen #28106/28006) or AMPure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter Life Sciences #A63881).

2.2. In Vitro Mouse Model

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco/ Thermo-Fisher Scientific #11965–084).

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), which can be purchased from various vendors, for example, Seradigm (#1500–500).

Penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco/Thermo-Fisher #15140–122).

2.3. RNA-Seq

Illumina TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit v2, which includes oligo-dT magnetic beads, washing buffer, elution buffer, and Elute, Prime, Fragment Mix (Illumina #RS-122–2001/2002).

Nuclease-free water (Molecular Biology Grade Water).

Reverse transcriptase SuperScriptII (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific #18064014).

QIAquick standard/MinElute PCR purification kits (Qiagen #28106/28006).

AMPure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter Life Sciences #A63881).

PCR cycler.

Illumina sequencer.

3. Methods

3.1. In Vivo Mouse Model

The onset of XCI during embryogenesis depends on increased expression of the long noncoding RNA Xist, itself dependent on the presence of the proximal A-repeat of Xist [32]. We have derived a mouse model with skewed X inactivation, using a mutant in which the proximal A-repeat of Xist (XistΔ), is deleted (B6. Cg-Xist<tm5Sado>, RIKEN) [19]. Carrier female mice are bred to M. spretus male mice. Note that the cross can only be done using male spretus mice. F1 female mice with skewed inactivation of the spretus X chromosome are identified by genotyping. As an alternative to M. spretus, M. castaneus can be used; while there are fewer SNPs between this species and the reference C57BL/6 (BL6) genome, M. castaneus is a bit easier to breed and can be crossed in both directions. Both mouse systems can be adapted to single cell RNA-seq analyses, in which case XCI skewing is unnecessary.

Maintain a small colony of BL6 mutant Xist (XistΔ/+) mice by breeding carrier females to normal BL6 males. Genotype progeny to verify mutant status using Xist-specific primers [32]. Note that males with the mutation cannot be used for breeding because of lethality of the paternal Xist mutation, which prevents imprinted XCI of the paternal X chromosome in extraembryonic tissues in F1 carrier females [32]

Breed BL6 carrier females with the mutant Xist (XistΔ/+) to M. spretus (or M. castaneus) males.

Prepare genomic DNA from ear-punches using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit and perform standard PCR using Taq DNA polymerase to verify mutant status using Xist-specific primers [32]. We usually collect tissues from F1 females heterozygous for the Xist mutation at 8 weeks of age.

Extract total RNA from homogenized XistΔ/+ hybrid tissues (50–100 mg) using RNeasy mini kit and proceed with RNA- seq library preparation (see Subheading 3.3).

To verify skewing of XCI of the spretus X chromosome reverse-transcribe RNA into cDNA using SuperScriptII and perform PCR (see above) using primers specific for a control expressed gene, which is subject to XCI and can be differentiated by SNPs between the mouse species, for example, Pgk1 [33]. After purification of the RT-PCR products using QIAquick standard/MinElute PCR purification kit or AMPure XP beads sequence the cDNA by Sanger sequencing, which should show only the Pgk1 allele from BL6 in the cDNA.

3.2. In Vitro Mouse Model

We previously derived a cell line, Patski, from the kidney of an 18dpc F1 female embryo from a cross between a M. spretus male and a BL6 female with an HprtBM3 mutation [34], in which XCI was skewed by growing cells in HAT media [17]. After HAT selection, this cell line with skewed XCI of the BL6 X chromosome no longer needs to be grown in HAT.

Grow Patski cells in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Verify that the karyotype is normal or near-diploid as mouse cell lines tend to undergo multiple, rapid changes in chromosome ploidy in culture. If necessary, go back to an early passage. (see also Note 1).

Extract total RNA from Patski cell pellets (2–3 × 106 cells), using RNeasy mini kit and proceed with RNA-seq library preparation (see Subheading 3.3).

3.3. RNA-Seq Library Preparation

We use standard protocols to prepare RNA-seq libraries using Illumina TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit v2.

Isolate polyA mRNA using 0.1–4 μg of total RNA, which is diluted into a total volume of 50 μl with nuclease free water and then mixed with 50 μl of oligo-dT magnetic beads. Incubate at 65 °C for 5 min, and wash beads with 200 μl washing buffer prior to elution with 50 μl elution buffer. Following a second round of mRNA selection, mRNA is eluted using the Elute, Prime, Fragment Mix and then fragmented at 94 °C for 4–8 min depending on the need of read length.

Perform double-strand cDNA synthesis using reverse transcriptase, followed by end-repair and A-tailing according to the TruSeq instructions. Note that clean-up steps can be done using QIAquick standard/MinElute PCR purification kits or AMPure XP beads.

Ligate indexed adapters followed by two rounds of clean-up with AMpure XP beads to completely remove un-ligated adapters and adapter dimers.

Perform fragment enrichment by 15-cycle PCR followed by clean-up with AMpure XP beads.

Sequence libraries using an Illumina sequencer generating 36 bp single-end reads. Note that longer reads (for instance, 75 bp) or paired-end reads are preferred, especially when using a mouse system with lower SNP density rate (e.g., the M. musculus × M. castaneus cross). A yield of ~100 million reads is recommended for allelic expression analysis.

3.4. Allele-Specific Expression Analysis

We present two methods for identifying genes that are subject to XCI (i.e., with sole expression from the active X) and genes that escape XCI (i.e., with biallelic expression).

3.4.1. Method 1

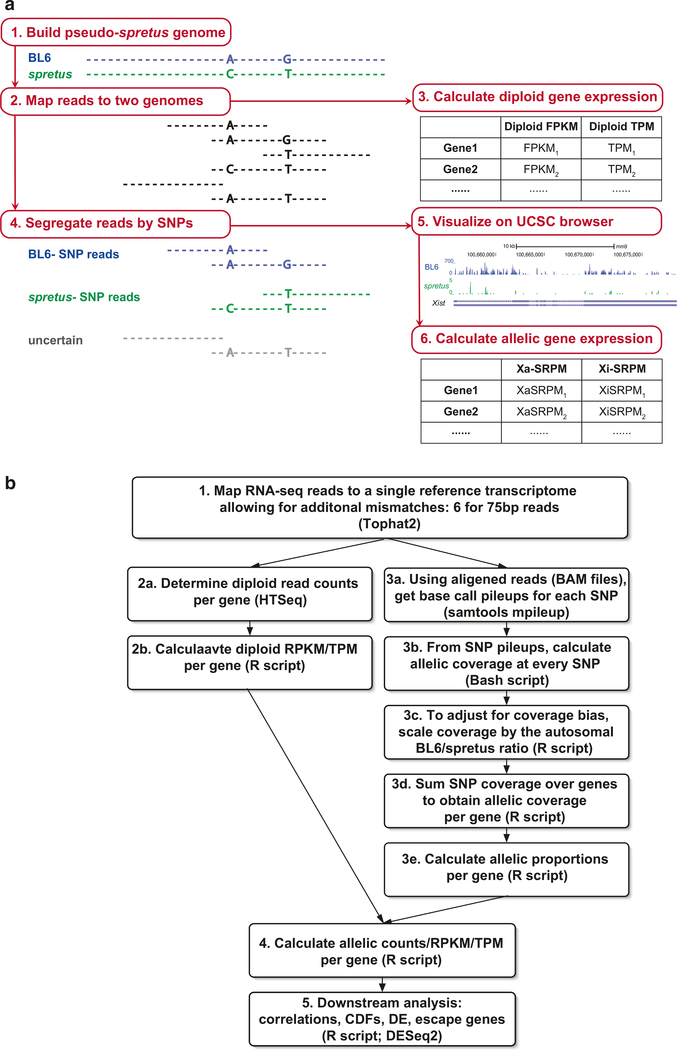

The first approach is summarized by the workflow depicted in Fig. 1a. Here, reads from the RNA-seq are aligned to both the reference genome (BL6) and to the other mouse species genome (M. spretus or M. castaneus), separately. Heterozygous SNPs between the two parental species are then inspected to assign each RNA-seq read to the corresponding allele. The specific steps follow:

To identify reads that map to each parental genome of F1 cells or tissues, a “pseudo-spretus” genome (or a “pseudo-castaneus” genome) is first assembled by substituting known het-erozygous SNPs of spretus (or castaneus) into the BL6 NCBIv37/mm9 reference genome [35]. Spretus SNPs (or castaneus SNPs) can be obtained from the Sanger Institute (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/science/data/mouse-genomes-project). According to the Nov/2011 spretus SNP database, 1,532,011 heterozygous SNPs were located on the X chromosome with 31,062 located in exons, while 33,909,724 were on autosomes, with 1,064,513 in exons. (see Note 2). A detailed breakdown of SNP numbers can be found in Table 1 for the BL6 × M. spretus cross.

Map RNA-seq reads to both the BL6 and the pseudo-spretus genomes and transcriptomes using Tophat/v2 [36] with default parameters.

Calculate gene expression based on all high-quality, uniquely mapped reads using cufflinks/v2 [33] to determine the diploid gene-level RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon length per million mapped reads) expression values. Alternatively, gene expression values can be estimated using TPM (transcripts per kilobase of exon length per million mapped reads).

- Segregate all high-quality (MAPQ ≥ 30) and uniquely mapped reads into three categories (Table 2):

- BL6-SNP reads containing only BL6-specific SNP(s).

- spretus-SNP reads containing only spretus-specific SNP(s).

- Allele-uncertain reads, that is, reads that do not contain valid SNPs.

The allelic reads coverage tracks can be uploaded to the UCSC genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu) for visualization and inspection (Fig. 1a) [37, 38].

Estimate SNP-based haploid gene expression from alleles on the Xi or the Xa (Xi-SRPM or Xa-SRPM) using the SRPM (allele-specific SNP-containing exonic reads per ten million high-MAPQ uniquely mapped reads).

Fig. 1.

Two allele-specific RNA-seq analysis approaches. (a) Workflow based on mapping RNA-seq reads to both the reference assembly and the pseudo-spretus assembly containing SNPs. (b) Workflow based on mapping RNA-seq reads to the reference assembly only and then determining allelic coverage based on read pileups at each SNP. Step-by-step descriptions are provided in Subheadings 3.4 and 3.5 in the main text

Table 1.

Spretus SNP location summary

| Location | Total SNPsa | Number of exonic SNPsb | Number of genes with exonic SNPsc |

|---|---|---|---|

| X chromosome | 1,532,011 (4.3%) | 31,062 (2.0%) | 1,099 (73.6%) |

| Autosomes | 33,909,724 (95.7%) | 1,064,513 (3.1%) | 27,010 (93.1%) |

| Both | 35,441,735 (100%) | 1,095,575 (3.1%) | 28,109 (92.1%) |

The SNP information was obtained from the Sanger Institute (SNP database Nov/2011 version)

Total number of SNPs at the corresponding chromosomal locations (X, autosomes or both); percentage of SNPs over total SNPs in the genome is shown in parentheses

Number of genes with exons containing SNPs at the corresponding chromosomal locations (X, autosomes or both); percentage of SNPs located in exons is shown in parentheses

Number of genes with exons containing SNPs at the corresponding chromosomal locations (X, autosomes or both); percentage of genes with exons is shown in parentheses

Table 2.

Allelic reads mapping and segregation examples

| Experiment | Total number of reads | Percent of highquality (MAPQ ≥ 30) and uniquely mapped reads | Percent of BL6-SNP reads | Percent of spretus-SNP reads | Percent of SNP-uncertain reads | BL6/spretus ratio in autosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain rep. 1 | 104,241,363 | 80.2 | 11.5 | 10.4 | 78.1 | 1.04 |

| Brain rep. 2 | 36,430,212 | 85.6 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 76.8 | 1.04 |

| Spleen rep. 1 | 88,842,032 | 73.2 | 12.1 | 11.3 | 76.6 | 1.03 |

| Spleen rep. 2 | 32,538,760 | 72.0 | 12.2 | 11.3 | 76.5 | 1.04 |

The in vivo mouse tissue (brain and spleen) RNA-seq example data sets were reported in [16]

3.4.2. Method 2

The workflow for an alternative allele-specific expression analysis approach is shown in Fig. 1b. In this case, reads are only aligned to the BL6 reference genome from which diploid expression is calculated. Diploid expression values can then be apportioned to each allele for those genes with sufficient SNP coverage. An advantage of this approach is that allele-ambiguous reads will be included for genes with informative SNP coverage, increasing the level of allelic coverage and thereby providing additional power for performing subsequent differential expression analysis. A step-by-step description of this approach follows:

Map RNA-seq reads to the BL6 reference transcriptome with Tophat2 [36, 39] using default parameters, except that additional mismatches are tolerated. For example, six mismatches were allowed for 75 bp single-end reads. Alternatively, to avoid potential bias for the reference genome during read alignment, one could consider utilizing a ‘SNP-masked’ index, where bases at SNP sites are replaced by an ‘N’.

- Use the aligned reads (typically saved in the BAM file format) to determine diploid expression using a standard pipeline to:

- Assign mapped reads to refSeq exons using HT-seq [40].

- Counts per gene can subsequently be converted into TPMs or RPKMs.

- In parallel with step 2, determine allelic gene coverage as follows:

- Use the aligned reads to generate SNP coverage pileups using a tool such as SAMtools mpileup [41].

- Calculate allelic coverage for each SNP using the base-level pileups.

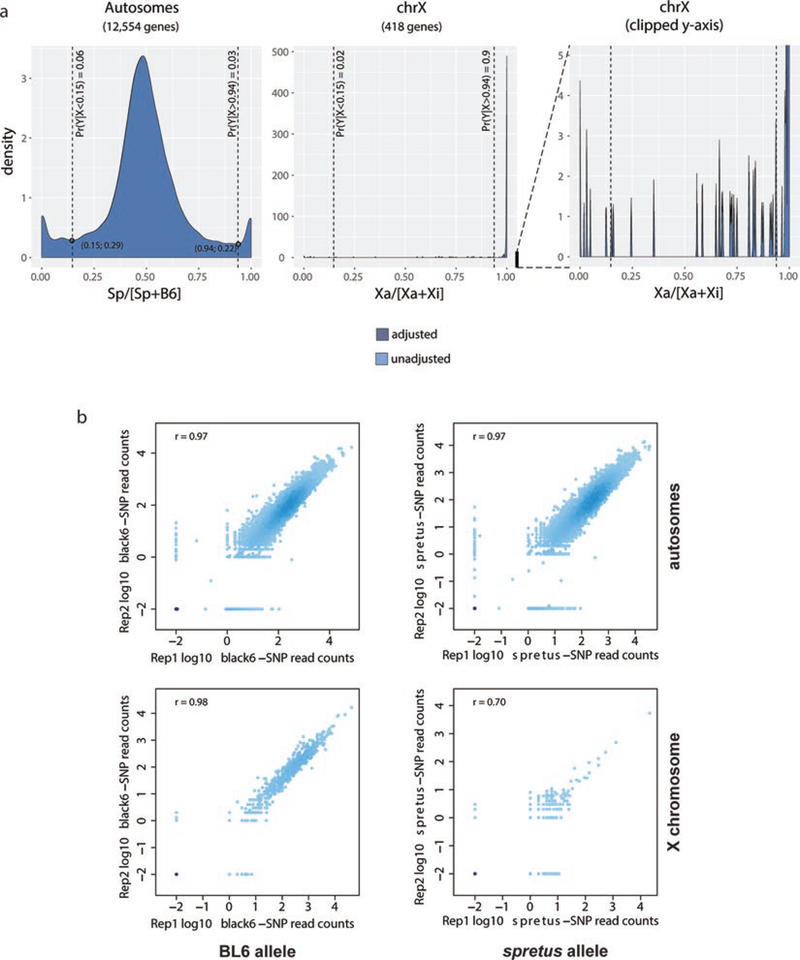

- Scale allelic coverage scores using the autosome-wide ratio of reference/alternative (i.e., BL6/spretus) SNP calls in order, to account for potential coverage bias in favor of the reference assembly. In our experience, this bias is seldom severe (Fig. 2a). An exception to this is where the cells under study show aneuploidy, in which case counts from affected chromosomes should be excluded in the calculation of the reference/alternative scaling factor.

- Determine gene level coverage by aggregating all SNPs that fall within a gene once SNP-level coverage has been determined and adjusted, if necessary. Genes containing spretus/BL6 SNPs that are covered by a total of at least five reads should be considered for allelic analysis.

- Calculate an allelic proportion of SNP read coverage (spretus/(spretus + BL6)) for each gene with sufficient SNP coverage. The allelic ratio for autosomal genes should be tightly distributed around 1:1, apart from a small set of imprinted genes (Fig. 2a). The allelic ratio for X-linked genes, on the other hand, should be strongly skewed toward the active X-chromosome, with relatively few genes showing biallelic or inactive X-chromosome-specific expression (Fig. 2a).

Distribute diploid read counts for each gene to each allele based on this SNP-read allelic proportion. The allele-specific counts can subsequently be converted into allelic TPM or RPKM expression values.

Allelic differential expression analysis can be performed using DESeq2 [42] for each allele as well as for diploid expression.

Fig. 2.

Allelic ratio distributions and reproducibility of biological replicates. (a) Density histograms of the distribution of allelic proportions (spretus/(spretus +BL6) for genes along autosomes (left) and the X-chromosomes (middle) for Patski female mouse F1 cells in which the inactive X (Xi) is from BL6 and the active X (Xa) from spretus. In the autosomal density plot the vertical dashed lines intersect the two minima (coordinates given in parentheses). The area under the curve to the left and right of these minima reflect a small proportion of imprinted genes that exhibit allele-specific expression. (see also Note 2). In the X chromosome density plot the Xa/(Xa+Xi) ratio for most genes is 1 since most genes are subject to XCI. (see also Note 3). Plotting the same thresholds (vertical dashed lines) on the X-chromosome density plot clearly highlights the fact that expression is skewed toward the Xa. However, an additional X-chromosome distribution is provided with the y-axis clipped to reveal small spikes of biallelic and active-X specific expression (right). Density plots before and after adjusting allelic coverage scores using the autosome-wide ratio of reference/alternative (i.e., BL6/spretus) SNP calls overlap perfectly, indicating that there was little bias in favor of the reference assembly. (b) Scatter plots of two biological replicates (rep1 and rep2) of in vivo hybrid mouse brain RNA-seq BL6 (left column) and spretus (right column) read counts for autosomal genes (top row) and for X-linked genes (bottom row). Each dot represents a gene; x-axis and y-axis are allelic SNP read counts in rep1 and rep2, respectively. Spearman correlation coefficient r between the two replicates are shown

3.5. Detection of Escape Genes

In our original survey, we identified genes that escape X inactivetion based on a cutoff of at least 10% expression from the inactive X versus the active X [3]. We subsequently refined this approach using a binomial model to identify genes escaping XCI and estimate the statistical confidence of the escape probability of X-linked genes [19]. (see Note 4).

- For each gene i on chromosome X, denote the number of allele- specific RNA-seq reads mapped to the inactive/active chromosomes as ni0 and ni1, respectively. Let ni = ni0 + ni1. Model the number of RNA-seq reads from the inactive X, ni0, by the following binomial distribution:

where pi indicates the expected proportion of allelic reads from Xi. The maximum likelihood estimate of the binomial proportion is . Using Wald’s method, compute the confidence interval of each as , where zα/2 is the 100(1 − α/2)th percentile of N(0,1).

To incorporate the mapping biases toward the BL6 genome over the pseudo-spretus genome into the above model, define the mapping bias ratio rm for each RNA-seq experiment to be rm = NA0/NA1, where NA0 and NA1 are the number of allele- specific autosomal reads in the “inactive X containing” genome and the “active X containing” genome, respectively. Thus, the mapping bias corrected estimate of allelic proportion pi is . The upper and lower confidence limits can be corrected accordingly.

- For each RNA-seq experiment, define an X-linked gene as an “escape” gene using the following three criteria:

- The 99% lower confidence limit (α = 0.01) of the escape probability is >0.

- The diploid gene expression measured by RPKM is ≥1, which indicates the gene was expressed.

- The normalized Xi-SRPM is ≥2.

- Genes that escape XCI can also be called using the alternative allele-specific expression analysis approach (Subheading 3.4.2). The alternative criteria for identifying escape genes are as follows:

- The 99% lower confidence limit (α = 0.01) of the escape probability is greater than 0.01, which is based on a binomial distribution parameterized by the expected proportion of reads from the Xi indicating some contribution from the Xi.

- The diploid gene expression measured by TPM is ≥1, indicating that the gene is expressed.

- The Xi-TPM is ≥0.1, representing sufficient reads from the Xi.

- The SNP coverage is ≥5.

Biological replicates of RNA-seq experiments should be analyzed separately. Consistency between biological replicates can be estimated using Spearman correlation coefficient r, or the coefficient of determination R2. In both our in vivo and in vitro systems, the observed Xi − SRPM values are correlated between biological replicates (r ≥ 0.7) (Fig. 2b).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants GM046883 (C.M.D.), GM113943 (C.M.D., W.M.), and DK107979 (C.M.D., W.N.).

Footnotes

Note that the Patski cell line should grow slowly (population doubling about 20–24 h); if it starts to grow fast it is usually because of increased aneuploidy.

Anomalies in the allelic ratio of SNP read coverage (spretus/ (spretus + BL6)) for autosomal genes, which should be relatively tightly distributed around 1:1, may indicate aneuploidy. Note that, while the BL6 genome is generally invariant, the genome from different spretus mice may vary from the canonical Sanger sequence, which may necessitates SNP validation.

Anomalies in the allelic ratio of SNP read coverage (spretus/ (spretus + BL6)) for X-linked genes, which should be strongly skewed toward the active X-chromosome, may indicate incomplete XCI skewing and/or numerical or structural X abnormalities.

The approaches described here for mouse systems are applicable to the analysis of human tissues. However, fewer SNPs are available to differentiate alleles in human and skewed XCI rarely occurs naturally, which necessitates the derivation of cell clones or single cells.

References

- 1.Deng X, Berletch JB, Nguyen DK et al. (2014) X chromosome regulation: diverse patterns in development, tissues and disease. Nat Rev Genet 15:367–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrel L, Willard HF (2005) X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature 434:400–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang F, Babak T, Shendure J et al. (2010) Global survey of escape from X inactivation by RNA-sequencing in mouse. Genome Res 20:614–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berletch JB, Yang F, Disteche CM (2010) Escape from X inactivation in mice and humans. Genome Biol 11:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellott DW, Hughes JF, Skaletsky H et al. (2014) Mammalian Y chromosomes retain widely expressed dosage-sensitive regulators. Nature 508:494–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortez D, Marin R, Toledo-Flores D et al. (2014) Origins and functional evolution of Y chromosomes across mammals. Nature 508:488–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaton BP, Brown CJ (2016) Escape artists of the X chromosome. Trends Genet 32:348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berletch JB, Yang F, Xu J et al. (2011) Genes that escape from X inactivation. Hum Genet 130:237–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disteche CM (2016) Dosage compensation of the sex chromosomes and autosomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 56:9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disteche CM (2012) Dosage compensation of the sex chromosomes. Annu Rev Genet 46:537–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyon M (1961) Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L). Nature 190:372–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Migeon BR (2014) Females are mosaic: X inac-tivation and sex differences in disease. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrese JM, Sun W, Song L et al. (2012) Site-specific silencing of regulatory elements as a mechanism of X inactivation. Cell 151:951–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbel C, Diabangouaya P, Gendrel AV et al. (2013) Unusual chromatin status and organization of the inactive X chromosome in murine trophoblast giant cells. Development 140: 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn EH, Smith CL, Rodriguez J et al. (2014) Maternal bias and escape from X chromosome imprinting in the midgestation mouse placenta. Dev Biol 390:80–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berletch JB, Ma W, Yang F et al. (2015) Identification of genes escaping X inactivation by allelic expression analysis in a novel hybrid mouse model. Data Brief 5:761–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lingenfelter PA, Adler DA, Poslinski D et al. (1998) Escape from X inactivation of Smcx is preceded by silencing during mouse development. Nat Genet 18:212–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balaton BP, Cotton AM, Brown CJ (2015) Derivation of consensus inactivation status for X-linked genes from genome-wide studies. Biol Sex Differ 6:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berletch JB, Ma W, Yang F et al. (2015) Escape from X inactivation varies in mouse tissues. PLoS Genet 11:e1005079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng Q, Ramskold D, Reinius B et al. (2014) Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science 343:193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks H, Kerstens HH, Barakat TS et al. (2015) Dynamics of gene silencing during X inactivation using allele-specific RNA-seq. Genome Biol 16:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benitez JA, Cheng S, Deng Q (2017) Revealing allele-specific gene expression by single-cell transcriptomics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Nadaf S, Deakin JE, Gilbert C et al. (2011) A cross-species comparison of escape from X inactivation in Eutheria: implications for evolution of X chromosome inactivation. Chromosoma 121:71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu H, Luo J, Yu H et al. (2014) Cellular reso-lution maps of X chromosome inactivation: implications for neural development, function, and disease. Neuron 81:103–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Daugharthy ER, Scheiman J et al. (2015) Fluorescent in situ sequencing (FISSEQ) of RNA for gene expression profiling in intact cells and tissues. Nat Protoc 10:442–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotton AM, Lam L, Affleck JG et al. (2011) Chromosome-wide DNA methylation analysis predicts human tissue-specific X inactivation. Hum Genet 130:187–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotton AM, Price EM, Jones MJ et al. (2015) Landscape of DNA methylation on the X chromosome reflects CpG density, functional chromatin state and X-chromosome inactivation. Hum Mol Genet 24:1528–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filippova GN, Cheng MK, Moore JM et al. (2005) Boundaries between chromosomal domains of X inactivation and escape bind CTCF and lack CpG methylation during early development. Dev Cell 8:31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keown CL, Berletch JB, Castanon R et al. (2017) Allele-specific non-CG DNA methylation marks domains of active chromatin in female mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E2882–E2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR et al. (2013) Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science 341:1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marks H, Chow JC, Denissov S et al. (2009) High-resolution analysis of epigenetic changes associated with X inactivation. Genome Res 19:1361–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoki Y, Kimura N, Kanbayashi M et al. (2009) A proximal conserved repeat in the Xist gene is essential as a genomic element for X-inactivation in mouse. Development 136:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G et al. (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28:511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hooper M, Hardy K, Handyside A et al. (1987) HPRT-deficient (Lesch-Nyhan) mouse embryos derived from germline colonization by cultured cells. Nature 326:292–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mouse Genome Sequencing C, Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K et al. (2002) Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420:520–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL (2009) TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25:1105–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS et al. (2002) The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res 12:996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raney BJ, Dreszer TR, Barber GP et al. (2014) Track data hubs enable visualization of user-defined genome-wide annotations on the UCSC Genome Browser. Bioinformatics 30:1003–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C et al. (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14:R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31:166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A et al. (2009) The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]