Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Inner-city Black women may be more susceptible to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than White women, although mechanisms underlying this association are unclear. Living in urban neighborhoods distinguished by higher chronic stress may contribute to racial differences in women’s cognitive, affective, and social vulnerabilities, leading to greater trauma-related distress including PTSD. Yet social support could buffer the negative effects of psychosocial vulnerabilities on women’s health.

Methods/Design:

Mediation and moderated mediation models were tested with 371 inner-city women, including psychosocial vulnerability (i.e., catastrophizing, anger, social undermining) mediating the pathway between race and PTSD, and social support moderating psychosocial vulnerability and PTSD.

Results:

Despite comparable rates of trauma, Black women reported higher vulnerability and PTSD symptoms, and lower support compared to White Hispanic and non-Hispanic women. Psychosocial vulnerability mediated the pathway between race and PTSD, and social support moderated vulnerability, reducing negative effects on PTSD. When examining associations by race, the moderation effect remained significant for Black women only.

Conclusions:

Altogether these psychosocial vulnerabilities represent one potential mechanism explaining Black women’s greater risk of PTSD, although cumulative psychosocial vulnerability may be buffered by social support. Despite higher support, inner-city White women’s psychosocial vulnerability may actually outweigh support’s benefits for reducing trauma-related distress.

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is a ubiquitous risk in geographical areas characterized by social disadvantage; trauma contributes to chronic stress as well as to stress-related disorders in women (Anakwenze & Zuberi, 2013; Clark et al., 2008; Vogel & Marshall, 2001). Jackson and Knight (2006) theorized that environmental characteristics shape stress-responsive behavior and subsequent distress. Relative to non-Hispanic and Hispanic Whites, Black women tend to live in neighborhoods more differentiated by violence and experience higher rates of racial discrimination (Gillespie et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2011). Correspondingly, Black inner-city residents, females and low-income individuals all tend to be most vulnerable to traumatic event exposure; other chronic stressors are also especially pervasive for those groups (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Living in an urban environment increases the likelihood that traumatic events profoundly affect Black women’s psychological distress and physical health. Compared to women of other ethnicities and race, Black inner-city women may be particularly vulnerable to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Alim et al., 2006; Bradley et al., 2005; Breslau et al., 1991; Ghafoori et al., 2012; Lipsky et al., 2009; Tolin & Foa, 2006).

The mechanisms by which Black women’s traumatic stress, along with the psychosocial imprint of their environment, may lead to greater symptoms of PTSD, is unknown. Psychological vulnerability includes a variety of regulatory strategies that may deleteriously affect a person’s coping and together promote stress-related disorders (Alim et al., 2008; Sinclair & Wallston, 1999; Thoits, 1982). Within urban contexts, negative coping is shown to predict negative symptoms including PTSD (Dempsey, 2002; Richards et al., 2004). As reviewed by Agaibi and Wilson (2005), vulnerability to PTSD is multifaceted, including one’s coping styles, cognitive and social factors. Deficits in personal and social resources may be more salient than perceived strengths, and individual vulnerabilities often function in an integrated, additive fashion rather than separately (Agaibi and Wilson 2005; Gaffey et al., 2018; Hobfoll et al., 2003). Since personal and social resources tend to aggregate, we propose that the umbrella term psychosocial vulnerability is more inclusive than psychological vulnerability, but do not suggest that this term encompasses all potentially important vulnerabilities (Cundiff et al., 2013; Hobfoll, 2003; Lillis et al., 2018).

Psychosocial vulnerability is operationalized as pain catastrophizing, anger and social undermining. Based on past examinations of individual vulnerability factors, there may be race differences in pathways between psychosocial vulnerability and trauma-related distress. Compared to White Hispanic and non-Hispanics, Blacks have reported greater vulnerability across multiple domains including maladaptive cognitions (e.g., catastrophizing; Edwards et al., 2005; Forsythe et al., 2011), negative affect (e.g., anger; Gibbons et al., 2014; Krieger et al., 1996; Mawbry & Kiecolt, 2005; Ryan et al., 2006) and chronic negative social experiences (e.g., personal victimization such as social undermining; Duffy et al., 2002; Lincoln et al., 2003; Vinokur and van Ryn, 1993). Although many other factors likely influence psychosocial vulnerability, these factors represent emotional, cognitive and social domains, and together partially account for the complex psychosocial vulnerability predisposing Black women to trauma-related distress.

Factors within the proposed operationalization of psychosocial vulnerability have also been associated with race differences in physical health conditions associated with PTSD. Pain catastrophizing (i.e., rumination and magnification) and anger are correlated with chronic pain, both of which may be higher among Black compared to White men and women (Burns et al., 2008; Forsythe et al., 2011; Hardt et al., 2008; Mabry & Kiecolt, 2005; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Meints et al., 2016). Greater catastrophizing and negative affect (i.e., anger) potentially reflect environmental differences in the appraisal and experience of stress, and in social as well as physical pain (Sullivan et al., 1995, 2001). A history of traumatic stress, exacerbated by environmental stress resulting from Black women’s experiences with racial and social disadvantage, may be modulated by catastrophizing, anger and other psychosocial vulnerabilities. Thus, inner-city Black women’s coping style may heighten their risk of significant psychological distress and physical malady, leaving them more susceptible to PTSD compared to their White counterparts.

In addition to trauma, stressors associated with inner-city Black women’s disadvantaged status may also lead to social undermining - where close relationships are negative, prevent one from meeting goals, and sabotage effective coping (Finch et al., 1999; Lakey et al., 1994; Oetzel et al., 2014; Rohed & Woods, 1995). Social undermining is shown to be an independent construct from low social support per se (Creed & Moore, 2006; Vinokur & van Ryn, 1993). Undermining may be especially powerful because negative events are unpredictable and therefore more distressing (Cranford, 2004; Duffy et al., 2002; Vinokur & van Ryn, 1993). As such, social undermining can increase one’s risk of psychological distress, perhaps more so for women with a history of trauma, and could lead to a poorer quality of life for Black women in particular (Brewin et al., 2000; Hepburn et al., 2013; Oetzel et al, 2014).

Other factors may protect against race differences in PTSD. Social support is a vital aspect of psychological resilience and is crucial for “buffering” against trauma, chronic stress, and psychosocial vulnerability across the lifespan (e.g., Cohen and McKay, 1984; Gaffey et al., 2018; Guay, Billette and Marchand, 2006). Individuals may overcome (or buffer against) psychosocial vulnerabilities using their social support network, resulting in better psychological wellbeing (i.e., lower symptoms of PTSD). There are also well-established negative associations between social support and PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008; Ozer et al., 2003). Thus, social support may moderate the pathway between psychosocial vulnerability and PTSD, helping individuals compensate for other (potentially automatic) negative aspects of coping. In turn, women with greater psychosocial vulnerability and high social support would have less symptoms of PTSD compared to those with less support. Social support could, thus, be a particularly effective coping strategy for urban Black women to protect against PTSD (Alim et al., 2008).

Positive social interactions may be even more important for Black women in the inner-city who may depend more on their networks for instrumental and emotional resources to manage greater stress (Rhodes et al., 1994). Compared to White individuals, Blacks appear to maintain more extensive social networks, composed of a greater proportion of family and fictive kin, and report more frequent contact with members of their network (Ajrouch et al., 2001; Rhodes et al., 1994). Those unique social relationships may prevent individuals from deferring to cognitive, emotional or social resources that are maladaptive for managing stress and promote psychological distress instead of buffering against distress (Galovski & Lyons, 2004; Garnefski & Spinhoven, 2001). Thus, social support may be more pivotal for those who have other psychosocial vulnerabilities.

Given past findings and our hypotheses about a broader, integrated influence of race in inner-city women’s chronic stress and social circumstances, the aggregate effects of catastrophizing, anger, and social undermining (i.e., psychosocial vulnerability) on psychological distress, and the potential role of social support in protecting against such vulnerability, we thought it was important to assess associations between inner-city women’s race (i.e., Black vs. White [Hispanic and non-Hispanic]), psychosocial vulnerability and social support on symptoms of PTSD. To focus on distinctive pathways for Black women and to maximize statistical power, we collapsed across ethnicity. As part of an ongoing, longitudinal study examining trauma and physical pain, we studied a population of urban female residents presenting to the Rush University Medical Center (RUMC) Emergency Department (ED). We proposed the following hypotheses: 1) Greater psychosocial vulnerability would be associated with higher symptoms of PTSD; 2) Black women would have higher vulnerability (e.g., catastrophizing, anger, social undermining) and PTSD symptoms compared to White women; 3) Psychosocial vulnerability would mediate the association between race and PTSD symptoms such that Black women’s greater vulnerability would account for their higher PTSD symptoms; 4) Social support would moderate the association between vulnerability and PTSD, with high support limiting the influence of race differences in vulnerability on PTSD; and 5) The moderating effect of social support would differ for Black and White participants.

METHODS

Participants

The sample included women who were between the ages of 18-41 and fluent in English who presented to the RUMC ED with an acute pain complaint. Potential participants’ eligibility was initially reviewed using electronic medical records. Research staff contacted patients within 72-hours following the ED visit to confirm eligibility with a brief screening. Participants were excluded if they had a history of chronic pain, were pregnant or trying to become pregnant, presented to the ED under the influence of drugs or alcohol, received psychiatric services during the ED visit, or had presenting pain related to a physical trauma. Overall, 1591 women were recruited between 2/1/2016 and 5/15/18 and 375 were immediately deemed ineligible. Of the remaining 1216 recruits, 683 did not answer follow-up phone calls to schedule and did not attend their baseline session, 162 refused to participate due to no longer being interested, and 3 declined to report race leaving N = 371.

See Table 1 for descriptive data across the sample and by race. The final sample averaged 28.46 years of age (SD = 6.010). The largest proportion of participants identified as Black (45.2%). About a third of the women possessed a high school education or less (37.7%) and many reported incomes less than $39,999 (73.1%). Half of the sample was unemployed or held multiple jobs (52.8%), and reported their income was not enough to meet needs (53.4%). Overall, this group is representative of the racial and economic distribution within the Rush ED population.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Psychosocial Variables, and Pain Ratings

| All Participants (N=371) |

Black (N=221) |

White (N=150) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p-value | |

| Demographic Variables | |||||||

| Relationship Status | .01 | ||||||

| Single | 140 | 37.7 | 100 | 45.2 | 40 | 26.7 | |

| In a relationship | 161 | 43.4 | 89 | 40.3 | 72 | 48.0 | |

| Married | 56 | 15.1 | 23 | 10.4 | 33 | 22.0 | |

| Divorced | 4 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.4 | 1 | .7 | |

| Other | 10 | 2.7 | 6 | 2.7 | 4 | 2.7 | |

| Education | .001 | ||||||

| High school or Less | 140 | 37.7 | 96 | 43.4 | 44 | 29.3 | |

| Some college | 156 | 42.0 | 102 | 46.2 | 54 | 36.0 | |

| College degree or higher | 75 | 20.2 | 23 | 10.4 | 52 | 24.7 | |

| Annual Income | .001 | ||||||

| < $10,000 | 129 | 34.8 | 101 | 45.7 | 28 | 18.7 | |

| $10,000-$39,999 | 142 | 38.3 | 83 | 37.6 | 59 | 39.3 | |

| >$40,000 | 92 | 24.8 | 31 | 14.0 | 61 | 40.7 | |

| Unknown | 8 | 2.2 | 6 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Employment | .05 | ||||||

| Full-Time | 175 | 47.2 | 98 | 44.3 | 77 | 51.3 | |

| Part-Time/Multiple jobs | 99 | 26.7 | 53 | 24.0 | 46 | 30.7 | |

| Unemployed | 97 | 26.1 | 70 | 31.7 | 27 | 18.0 | |

| Income Needs Met | .001 | ||||||

| Not Enough | 198 | 53.4 | 142 | 64.3 | 56 | 37.3 | |

| Enough | 146 | 39.4 | 74 | 33.5 | 72 | 48.0 | |

| More Than Enough | 27 | 7.3 | 5 | 2.3 | 22 | 14.7 | |

| Trauma | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Range |

| Crime-Related Events General Disaster |

0.78 2.76 |

0.95 1.86 |

.84 2.90 |

.99 1.84 |

.69 2.55 |

.88 1.87 |

0-4 0-13 |

| Sexual Abuse | 0.51 | 0.78 | .48 | .79 | .54 | .77 | 0-3 |

| Physical Abuse | 0.53 | 0.75 | .52 | .71 | .56 | .82 | 0-3 |

| Total | 4.58 | 3.05 | 4.74 | 3.04 | 4.35 | 3.05 | 0-23 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Range | |

| Age | 28.46 | 6.10 | 28.47 | 6.27 | 28.45 | 5.87 | 18-41 |

| Psychosocial Variables | |||||||

| Social Support*** | 15.11 | 4.30 | 14.34 | 4.48 | 16.25 | 3.76 | 0-20 |

| Social Undermining* | 15.47 | 5.97 | 16.03 | 6.56 | 14.65 | 4.87 | 0-28 |

| Pain Catastrophizing* | 28.78 | 12.40 | 29.97 | 12.58 | 27.01 | 11.94 | 0-52 |

| Anger* | 13.88 | 5.14 | 14.34 | 5.63 | 13.19 | 4.23 | 0-20 |

| Psychological Distress | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms** | 11.40 | 5.59 | 10.79 | 5.75 | 12.30 | 5.23 | 0-32 |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001 (2-tailed tests)

Procedures

Participants completed informed consent at the baseline interview within 14 days of presenting to the ED. Trained research assistants administered the survey-interviews using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). Information collected included demographic characteristics, psychosocial functioning, mental health, and trauma history. Participants then completed other tasks not relevant to this manuscript. The session took ~2.5 hours and participants received gift cards upon completion. The RUMC Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Measures

Demographics questionnaire.

A structured demographics questionnaire was used to assess characteristics of the sample including age, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, income, whether income needs were met, and employment status.

Pain catastrophizing.

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Sullivan et al., 1995) consisted of 13-items characterizing thoughts and feelings that may occur while in pain. Using a 5-point scale (0 = “not at all” to 4 = “all the time”), participants rated the degree to which they experienced certain thoughts and feelings while in pain. Catastrophizing equaled the total score, with higher scores indicating more catastrophizing. The Scale has demonstrated strong internal consistency (Forsythe et al., 2011; α = 0.93), including for Black individuals specifically (α = 0.89; Chibnall & Tait, 2005), as our reference group of interest. Cronbach’s α for this study was .95.

Anger.

The PROMIS Anger scale (Pilkonis et al., 2011) assessed feelings of irritation, being grouchy, etc. over the past 14 days. The scale used 5-point ratings (0 = “never” to 4 = “always”), summing to a total score, with higher scores indicating greater anger. The measure has been shown to have high internal consistency (α = 0.96), but has not been assessed in Black individuals specifically. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Social undermining.

The Social Undermining Scale (SUND; Abbey et al., 1985) examines the extent an individual believes they are victimized by members of their social network. Using a 7-item, 5-point scale (0 = “not at all” to 4 = “nearly all the time/all the time”), participants indicated how frequently they are targeted with negative behavior such as, “act(ing) in an angry or unpleasant manner.” Items were summed, with higher scores indicating greater undermining. Internal consistency has previously been .84-.91 (Cranford, 2004; Vinokur & van Ryn, 1993), and the measure has been consistent with Black individuals (α = .75). Cronbach’s α was .89.

Social support.

Social support was assessed based on Weiss’s (1974) Theory of Social Provisions. Participants responded to a 10-item, 5-point scale (1 = “none of the time” to 5 = “all the time”), assessing participants’ number of confidants and whether they had others with whom to confide in, help with responsibilities, turn to for support, and who makes them feel loved. The sum indicated the total level of social support. Reliability for the scale has ranged from .81 to .91 (Weiss, 1974). Although there is no data for Black individuals alone, Cronbach’s α was similarly .85 in this study.

Traumatic Events.

The Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ; Hooper et al., 2011) was used to measure the experiences of traumatic events across the lifespan. The 24-item measure assesses if participants ever experienced trauma across crime-related events, general disaster, as well as physical and sexual assault (yes/no). The number of events endorsed was totaled. Although the THQ cannot be assessed by traditional psychometrics it has sound properties (Hooper et al., 2011).

PTSD Symptoms.

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) was used to measure PTSD symptoms. Before completing the PCL-5, participants were asked to reflect on a lifetime trauma they considered to be the worst or most distressing event. Participants then completed the PCL-5, rating the degree to which they experienced PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, and negative alterations in cognition and mood in the last month. The PCL-5 has excellent psychometric properties (Blevins et al., 2015), but has not been assessed in Black individuals alone. Cronbach’s α in this study was .94.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics, psychosocial variables, trauma, and PTSD symptoms. Regression was used to assess collinearity between social support and social undermining (tolerance > .2, variance inflation factor [VIF] < 10). T-tests and zero-order correlations between hypothesized predictor, mediator, and criterion variables were examined to determine the criteria for testing mediation and moderation (see Table 2 for a correlation matrix; Baron and Kenny, 1986). Overall, p-values < 0.05 were interpreted as significant.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations Among Trauma, Social Support, Factors of Psychosocial Vulnerability, PTSD and Race

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trauma | -- | ||||||

| 2. Social Support | −.278*** | -- | |||||

| 3. Pain Catastrophizing | .078 | −.243*** | -- | ||||

| 4. Anger | .302*** | −.472*** | .281*** | -- | |||

| 5. Social Undermining | .302*** | −.501*** | .227*** | .498*** | -- | ||

| 6. PTSD Symptoms | .350*** | −.459*** | .387*** | .563*** | .463*** | -- | |

| 7. Race, 1=Black | .063 | −.218*** | .117* | .111* | .114* | .118* | -- |

Note: N = 371,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Pain catastrophizing, anger, and social undermining scales were integrated to create a latent variable representing psychosocial vulnerability. Other continuous variables were measured as described above. Analyses were conducted using 10,000 iterations (Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000). A sample of >200 participants is appropriate for testing SEM, and was exceeded (Kline, 2005). The models were evaluated based on chi-square (p < .05 required; Hu and Bentler, 1999), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; < .08 acceptable, < .05 excellent) and its relevant 90% confidence interval, the comparative fit index (CFI; > .90 acceptable, > .95 excellent), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; < .08 acceptable, < .05 excellent).

SEM analyses were planned in three stages. First, a mediation model controlling for social support was used to determine whether psychosocial vulnerability mediated the independent pathway between race and PTSD symptoms. A second moderated mediation model was used to assess if social support moderated the pathway between psychosocial vulnerability and PTSD symptoms, thus reducing potential race-associated effects of vulnerability on PTSD. For the moderation portion of the model, the PTSD symptoms variable was regressed on psychosocial vulnerability and social support separately, as well as an interaction term, ‘psychosocial vulnerability’ X ‘social support,’ that was generated using the Mplus XWITH command. Finally, to assess race differences in the moderation effect, race was removed from the model and the moderation effect of social support was assessed separately within Black and White samples.

RESULTS

There was no missing data and all variables were normally distributed. Additionally, there was no collinearity between social undermining and social support (tolerance: .744, VIF: 1.344). Based on t-tests and zero-order correlations, Black participants reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms (t(348) = −2.341, p = .020), suggesting there were effects to be mediated. There were no significant differences in trauma between Black women and those in the comparison group (t(369) = −1.213, p = .226). Compared to other participants, Blacks exhibited significantly greater psychosocial vulnerability (i.e., pain catastrophizing [t(369) = −2.270, p = .024], anger [t(369) = −2.257, p = .025], and social undermining [t(369) = −2.321, p = .021]). Across all participants and when examining the racial groups separately, pain catastrophizing, anger, and social undermining were correlated with greater PTSD symptoms (all p < .001). To assess the moderating role of social support in protecting against psychosocial vulnerability, we determined that Blacks had significantly less social support and that social support was negatively correlated with symptoms of PTSD (t(369) = 4.433, p <. 001; r = −.463, p < .001). Overall, criteria for the proposed paths were met for PTSD.

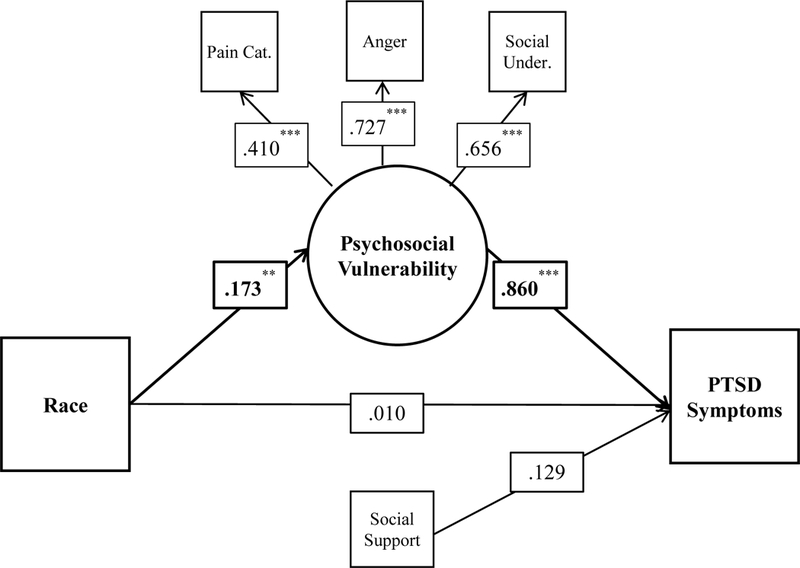

Addressing the first set of analyses, the hypothesized mediation model controlling for social support is presented in Figure 1. The model had good fit (x2(6) = 14.543, p = 0.024; CFI = 0.983; RMSEA = 0.062, 90% C.I. [0.021-0.103]; SRMR = 0.024). Race was a significant predictor of psychosocial vulnerability (β = 0.173, p = 0.003) and vulnerability significantly predicted PTSD (β = 0.860; p < 0.001). When examining standardized direct effects, the association between race and PTSD was not significant, indicating that the path was mediated (β = −0.010; see Table 3). Psychosocial vulnerability mediated the association between race and PTSD (β = 0.149, 95% CI (1.536, 9.114), p = 0.009), with 14.9% of the variance explained.

Figure 1.

Results of the mediation model including standardized β weights. The mediated pathway and relevant manifest and latent variables are highlighted in bold. Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 3.

Total and Unique Direct and Indirect Effects from the Mediation Model

| Model: Race to PTSD | B | SEB | β | SEβ | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | |||||

| Race | .322 | 1.469 | .010 | .045 | .827 |

| Indirect Effects | |||||

| Psychosocial vulnerability | 4.849 | 1.924 | .149 | .057 | .009 |

| Social support | −.432 | .367 | −.013 | .011 | .238 |

| Psychosocial vulnerability and support1 | −.486 | .484 | −.015 | .015 | .309 |

| Total Effects | 4.254 | 1.624 | .130 | .048 | .007 |

| Total Indirect | 3.932 | 1.682 | .120 | .050 | .016 |

Notes: Total effects equal the sum of direct and indirect effects.

The indirect pathway in which both psychosocial vulnerability and then social support are mediators is automatically estimated by the model but is not an interaction

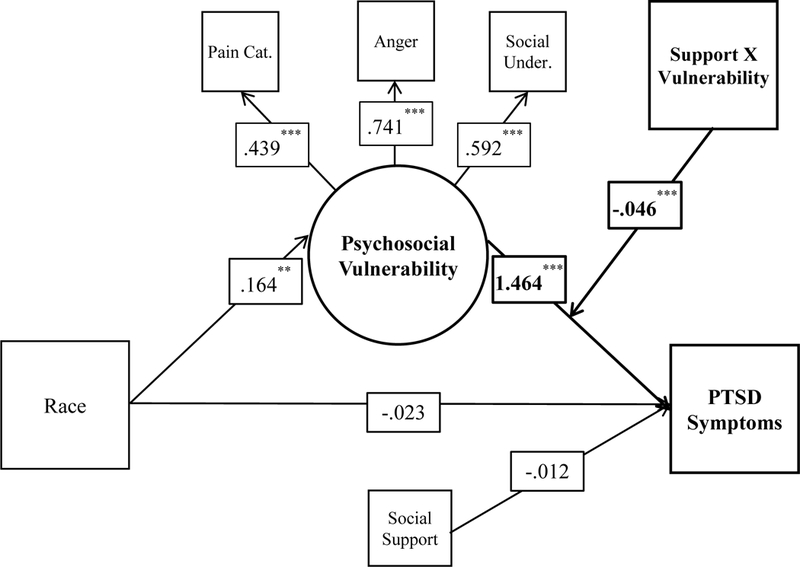

The second aim was to test the moderating role of social support in the pathway between psychosocial vulnerability and PTSD (Stride et al., 2016; Figure 2). Of note, fit statistics were unavailable when specifying the required model parameters for the interaction as the model was saturated. The psychosocial vulnerability X social support interaction term was significant (β=−0.046, 95% CI (−0.067, −0.025), p < 0.001), suggesting that the effect of psychosocial vulnerability on PTSD symptoms was lower for those with greater social support (Preacher et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Results of the moderated mediation model including standardized β weights. The moderated pathway and relevant latent and manifest variables are highlighted in bold. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Finally, additional analyses examined the moderating effect of social support separately in Black and White women. The interaction was significant for Black (β= −0.231, 95% CI (−0.284, −0.178), p < 0.001), but not for White individuals (β= −0.063, 95% CI (−0.146, 0.020), p = 0.448).

DISCUSSION

Urban, low income, Black women’s sociocultural environment, including experiences of trauma and disadvantage, uniquely and appreciably increases their risk of trauma-related psychopathology (Jackson et al., 2010). In this study of inner-city women, Black participants exhibited higher symptoms of PTSD compared to White Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants. Interestingly, there were no racial differences in trauma. Together these findings add to other studies reporting greater PTSD symptoms in Black compared to White women (e.g., Brewin et al., 2000; Frueh et al., 1998; Kaczkurkin et al., 2016). As Black men and women are less likely to seek psychological treatment compared to their White counterparts, potential racial differences in the incidence and severity of PTSD symptoms could have far-reaching clinical consequences (e.g., Roberts et al., 2011).

A lifetime of social disadvantage, chronic and traumatic stress could alter Black women’s cognitive, affective, and social resources, contributing to differential effects in their symptoms of PTSD and comorbid health problems such as pain (Olatunji et al., 2007; Qureshi et al., 2011). Our investigation is singular for using pain catastrophizing, anger, and social undermining to measure psychosocial vulnerability. Compared to White women, Black women reported higher vulnerability, which mediated the association between race and PTSD. If psychosocial vulnerability is produced by Black women’s environmental and personal stress, the contributing factors may also heighten the group’s sensitivity to further stress and thwart adaptation to additional negative events in a recurrent and harmful pattern. Studies examining psychosocial mediators are frequently hindered by assessing single resources rather than integrating across multiple factors, a conceptual and statistical choice essential for developing a more realistic representation of vulnerability toward understanding racial differences in health outcomes (Hobfoll et al., 2003; Hummer, 1996; Rini et al., 1999). Yet, psychosocial vulnerability only explained 14.9% of the variance in PTSD symptoms and we merely assessed three psychosocial factors. Other cognitive and affective strategies (e.g., desire for personal control, engagement, aggression, reappraisal, guilt; Blair et al., 2013; Greenberg, 1995; Lillis et al., 2018; Lincoln et al., 2003; Roemer et al., 2001) or health behaviors (e.g., alcohol, nicotine or other substance use; Hakimi et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2010) are maladaptive ways to cope with stress and could also underlie vulnerability to PTSD. Exploring additional factors with Black women in an urban setting together with the psychosocial factors from this study could further explain race differences in PTSD symptoms and the broader physical impact of environmental stress.

For over 30 years, social support has been touted as a protective factor for buffering against stressors, adversity, and hardship (Cohen and McKay, 1984). In this study, social support moderated the association between Black women’s heightened psychosocial vulnerability and symptoms of PTSD although the moderation effect was not found for White women. Our results contrast with findings that social support protects against PTSD for White women, but is less effective for Black women (Lipsky et al., 2016). Yet our findings align with numerous studies illustrating the benefits of social support for marginalized or disadvantaged groups of women and trauma survivors (e.g., Anderson et al., 2003; Schumm et al., 2006). Conservation of Resource (COR) Theory’s extension, social resource theory, offers one potential explanation concerning the unique utility of social support for disadvantaged groups (Hobfoll et al., 1988). Hobfoll and colleagues (1990) theorized that although beneficial, support systems are limited and are modified by stress so that support resources may become depleted by time and circumstances. Adding to that theory, perhaps disadvantaged individuals with fewer resources may also yield a greater benefit from social support, such as buffering against vulnerability and lowering psychological distress. Despite reporting lower social support, the cumulative effects of psychosocial vulnerability and social disadvantage were outweighed by the benefits of Black women’s social support, even though those resources were limited. Although White women exhibited lower vulnerability, it appears inner-city White women could become more overwhelmed by their vulnerability when managing stress.

Social support is a paramount resource for Black women (Mays et al., 1996). Williams et al. (2003) theorized that aspects of Black women’s expectations and their overall supportive network could inoculate them against stress-related psychopathology. Social relationships can also exacerbate psychological distress, particularly when individuals anticipate help but do not receive it (Brewin et al., 2000; Hepburn et al., 2013). Negative social interactions might be especially potent for those exposed to social disadvantage and chronic stress as well as trauma, such as Black women in urban settings. Our sample also reported a high level of trauma, which is shown to engender alienation or estrangement from social networks (Coker et al., 2003). Compared to White women, Black trauma survivors have endorsed more negative reactions from their social network following sexual assault (Hakimi et al., 2016). An individual’s assessment of negative interactions shapes their response to the events, including whether events are viewed as negative, and effects on psychological health (Crossley, 2009). If people feel greater sympathy and compassion toward perpetrators of negative social behavior, than they may be more likely to attempt reconciliation (Coker et al., 2003; Crossley et al., 2008). When attempts to appeal for positive social support fail, it could increase one’s perception of unreliable support, fueling additional maladaptive social interactions, and promoting social withdrawal or isolation. Thus, it may be as important to evade negative interactions as to engage in positive ones (Oetzel et al., 2014).

Our investigation has several limitations. First, the findings may be specific to this sample. We did not possess statistical power to concurrently examine differences in PTSD symptoms based on race and ethnicity. Other literature reporting higher PTSD symptoms in Blacks had greater proportions of White individuals (e.g., Ndao-Brumblay & Green, 2005; Ullman & Filipas, 2001), and it will be valuable to examine these processes with more racially balanced samples as well as women in non-urban settings. Second, causality cannot be determined due to using cross-sectional data. When testing alternate models reversing psychosocial vulnerability and social support, the models had poor fit (Kline, 2005) and did not align with relevant theoretical background. Additional data collection within this study will enable us to examine longitudinal trajectories between these factors. In another limitation, social support resources could take other forms not assessed in this investigation but more relevant to Black women, such as community cohesion, neighborhood disorder, or involvement in a religious community (Gapen et al., 2011; Gallup, 1984; Johns et al., 2012; Sampson, 2003). Black women might also use different types of support depending on their needs. In a study of intimate partner violence, women indicated that emotional support (e.g., empathy) is more beneficial than instrumental support (e.g., tangible services or assistance; Coker et al., 2003). Each type of support could yield different effects, with some mechanisms protecting against women’s distress while others (e.g., social undermining) could prolong stress.

This study offers additional insight into associations between race, trauma, and PTSD within an urban context. Race defines one’s personal and social resources and begets exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage, as well as experiences of conflict and traumatic stress (Gillespie et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2011). It appears that urban, low income Black women exhibit greater symptoms of PTSD, that the distinct association between race and PTSD is partially explained by psychosocial vulnerability, but may be buffered by Black women’s social support. Although social support is widely viewed as an asset, for this group especially, support resources may become strained and depleted due to constant stress, limiting the value of those networks (Hobfoll et al., 1990; 2003). Altogether, our study outlines potential mechanisms explaining vulnerability to PTSD symptoms in the context of the stressors inherent in low income, urban environments, and indicates that these factors may differentially impact Black women in particular. As each of the factors studied may be given to intervention, they also provide critical information about potential intervention strategies.

References

- Abbey A, Abramis DJ, & Caplan RD (1985). Effects of different sources of social support and social conflict on emotional well-being. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 6(2), 111–129. Doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0602_2 [Google Scholar]

- Alim TN, Charney DS, & Mellman TA (2006). An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. Journal of Clinical Psychology 62(7):801–813. Doi:10.1002/jclp.20280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DK, & Saunders DG (2003). Leaving an abusive partner: An empirical review of predictors, the process of leaving, and psychological well-being. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 4(2), 163–191. Doi:10.1177/1524838002250769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch KJ, Antonucci TC, & Janevic MR (2001). Social networks among Blacks and Whites: The interaction between race and age. The Journals of Gerontology B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(2):S112–S118. Doi:10.1093/geronb/56.2.S112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anakwenze U, & Zuberi D Mental health and poverty in the inner city. Health and Social Work, 38(3), 147–157. Doi:10.1093/hsw/hlt013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. Doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Schwartz AC, & Kaslow NJ (2005). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among low‐income, African American women with a history of intimate partner violence and suicidal behaviors: self‐esteem, social support, and religious coping. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(6), 685–696. Doi:10.1002/jts.20077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Vythilingam M, Crowe SL, McCaffrey DE, Ng P, Wu CC, Scaramozza M, Mondillo K, Pine DS, Charney DS, & Blair RJ (2013). Cognitive control of attention is differentially affected in trauma-exposed individuals with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 43(1), 85–95. Doi:10.1017/S0033291712000840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. Doi:10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, & Peterson E (1991). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(3), 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, & Valentine JD (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. Doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Quartana PJ, & Bruehl S (2008). Anger inhibition and pain: conceptualizations, evidence and new directions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(3), 259–279. Doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9154-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibnall JT, & Tait RC (2005). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in African American and Caucasian Workers’ Compensation claimants with low back injuries. Pain, 113(3), 369–375. Doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Ryan L, Kawachi I, Canner MJ, Berkman L, & Wright RJ (2008). Witnessing community violence in residential neighborhoods: a mental health hazard for urban women. Journal of Urban Health, 85(1), 22–38. Doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9229-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & McKay G (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis In Baum A & Singer JE (Eds.) Handbook of Psychology and Health. (pp. 253–267). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Watkins KW, Smith PH, & Brandt HM Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: application of structural equation models. Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 259–267. Doi:10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA (2004). Stress‐buffering or stress‐exacerbation? social support and social undermining as moderators of the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms among married people. Personal Relationships, 11(1), 23–40. Doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00069.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed PA, & Moore K (2006). Social support, social undermining, and coping in underemployed and unemployed persons. Journal of Applied and Social Psychology, 36(2), 321–339. Doi:10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00010.x [Google Scholar]

- Crossley CD (2009). Emotional and behavioral reactions to social undermining: a closer look at perceived offender motives. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1),14–24. Doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.06.001 [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MK, Ganster DC, & Pagon M (2002). Social undermining in the workplace. The Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 331–351. Doi:10.2307/3069350 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, & Ivankovich O (2005). Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: a comparison of African American, Hispanic, and white patients. Pain Medicine, 26(1), 88–98. Doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JF, Okun MA, Pool GJ, & Ruehlman LS (1999). A comparison of the influence of conflictual and supportive social interactions on psychological distress. Journal of Personality, 67(4), 581–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe LP, Thorn B, Day M, & Shelby G (2011). Race and sex differences in primary appraisals, catastrophizing, and experimental pain outcomes. Journal of Pain, 12(5), 563–572. Doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Brady KL, & de Arellano MA (1998). Racial differences in combat-related PTSD: empirical findings and conceptual issues. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(2), 287–305. Doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00087-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffey AE, Burns JW, Aranda F, Purim-Shem-Tov YA, Burgess HJ, Beckham JC, Bruehl S, & Hobfoll SE (2018-In press). Social support, social undermining, and acute clinical pain in women: Mediational pathways of negative cognitive appraisal and emotion. Journal of Health Psychology. Doi:10.1177/1359105318796189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski T, & Lyons JA (2004). Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(5), 477–501. Doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00045-4 [Google Scholar]

- Gapen M, Cross D, Ortigo K, Graham A, Johnson E, Evces M, Ressler KJ, & Bradley B (2011). Perceived neighborhood disorder, community cohesion, and PTSD symptoms among low-income African Americans in an urban health setting. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), 31–37. Doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, & Spinhoven P (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311–1327. Doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6 [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoori B, Barragan B, Tohidian N, & Palinkas L (2012). Racial and ethnic differences in symptom severity of PTSD, GAD, and depression in trauma‐exposed, urban, treatment‐seeking adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(1), 106–110. Doi:10.1002/jts.21663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng CY, Gerrard M, Cutrona C, Wills TA, & Stock M (2014). Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: a differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychology, 33(1), 11–9. Doi:10.1037/a0033857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie CF, Bradley B, Mercer K, Smith AK, Connelly K, Gapen M, Weiss T, Schwartz AC, Cubells JF, & Ressler KJ (2009). Trauma exposure and stress-related disorders in inner city primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry, 31(6), 505–514. Doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MA (1995). Cognitive processing of traumas: the role of intrusive thoughts and reappraisals. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(14), 1262–1296. Doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02618.x [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi D, Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, & Gobin RL Relationship between negative social reactions to sexual assault disclosure and mental health outcomes of black and white female survivors. (2016). Psychological Trauma, 10(3), 270–275. Doi:10.1037/tra0000245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J, Nickel R, & Buchwald D (2008). Prevalence of chronic pain in a representative sample in the United States. Pain Medicine, 9(7), 803–812. Doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn GC, & Enns JR (2013). Social undermining and well-being: the role of communal orientation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(4), 354–366. Doi:10.1108/JMP-01-2013-0011 [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE (1988). The ecology of stress. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Freedy J, Lane C, & Geller P (1990). Conservation of social resources: social support resource theory. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(4), 465–478. Doi:10.1177/0265407590074004 [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ, Ennis N, & Jackson AP (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643. Doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LM, Stockton P, Krupnick JL, & Green BL (2011). Development, use, and psychometric properties of the Trauma History Questionnaire. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16(3), 258–283. Doi:10.1080/15325024.2011.572035 [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. Doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, & Knight KM (2006). Race and self-regulatory health behaviors: The role of the stress response and the HPA axis in physical and mental health disparities In Schaie KW & Carstensen LL (Eds.) Societal impact on aging series. Social structures, aging, and self-regulation in the elderly (pp. 189–239). New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM, & Rafferty JA (2010). Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. American Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 933–939. Doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns LE, Aiello AE, Cheng C, Galea S, Koenen KC, & Uddin M (2012). Neighborhood social cohesion and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community-based sample: findings from the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(12), 1899–1906. Doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0506-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczkurkin AN, Asnaani A, Hall-Clark B, Peterson AL, Yarvis JS, Foa EB, & STRONG STAR Consortium. (2016). Ethnic and racial differences in clinically relevant symptoms in active duty military personnel with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 90–98. Doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, & Norris FH (2008). Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(3), 274–281. Doi:10.1002/jts.20334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, & Moosbrugger H (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika, 65(4), 457–474. Doi:10.1007/BF02296338 [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Details of path analysis. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, & Sidney S (1996). Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health, 86(10), 1370–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Tardiff TA, & Drew JB (1994). Negative social interactions: Assessment and relations to social support, cognition, and psychological distress. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 42–62. Doi:10.1521/jscp.1994.13.1.42 [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22(2), 144–168. Doi:10.1177/00957984960222002 [Google Scholar]

- Lillis TA, Burns J, Aranda F, Purim-Shem-Tov YA, Bruehl S, Beckham JC, & Hobfoll SE (2018-In press). PTSD Symptoms and Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: The Roles of Vulnerability and Resilience Factors among Low-income, Inner-city Women. The Clinical Journal of Pain. Doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, & Taylor RJ (2003). Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 390–407. Doi:10.2307/1519786 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Kernic MA, Qiu Q, & Hasin DS (2016). Traumatic events associated with posttraumatic stress disorder: the role of race/ethnicity and depression. Violence Against Women, 22(9), 1055–1074. Doi:10.1177/1077801215617553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry JB, & Kiecolt KJ (2005). Anger in black and white: Race, alienation, and anger. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(1), 85–101. Doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Caldwell CH, & Jackson JS (1996). Mental health symptoms and service utilization patterns of help-seeking among African American women In Neighbors HW & Jackson JS (Eds.), Mental health in Black America (pp. 161–176). Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Keyes KM (2010). Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1477–1484. Doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meints SM, Miller MM, & Hirsh AT (2016). Differences in pain coping between Black and White Americans: a meta-analysis. Journal of Pain, 17(6), 642–653. Doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2004). Mplus user’s guide. 3rd ed Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ndao-Brumblay SK, & Green CR (2005). Racial differences in the physical and psychosocial health among black and white women with chronic pain. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(10), 1369–1377. Doi:10.1177/1043659614526250 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Wilcox B, Archiopoli A, Avila M, Hell C, Hill R, & Muhammad M (2014). Social support and social undermining as explanatory factors for health-related quality of life in people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Communication, 19(6), 660–675. Doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.837555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, & Tolin DF (2007). Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(5), 572–581. Doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, & Weiss DS (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52–73. Doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D, & PROMIS Cooperative Group. (2011). Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment, 18(3), 263–283. Doi:10.1177/1073191111411667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, & Hayes AF (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227, Doi:10.1080/00273170701341316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi SU, Long ME, Bradshaw MR, Pyne JM, Magruder KM, Kimbrell T, Hudson TJ, Jawaid A, Schulz PE, & Kunik ME (2011). Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 23(1), 16–28. Doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.23.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Ebert L, & Meyers AB (1994). Social support, relationship problems and the psychological functioning of young African-American mothers. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(4), 587–599. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Litz BT, Orsillo SM, & Wagner AW (2001). A preliminary investigation of the role of strategic withholding of emotions in PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(1), 149–156. Doi:10.1023/A:1007895817502 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, & Koenen KC (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41(1), 71–83. Doi:10.1017/S0033291710000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AM, Gee GC, & Laflamme DF (2006). The association between self-reported discrimination, physical health and blood pressure: findings from African Americans, Black immigrants, and Latino immigrants in New Hampshire. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 17(2), 116–132. Doi:10.1353/hpu.2006.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ (2003). The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3 Supplement), S53–S64. Doi:10.1353/pbm.2003.0073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Briggs‐Phillips M, & Hobfoll SE (2006). Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner‐city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(6), 825–836. Doi:10.1002/jts.20159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair VG, & Wallston KA (1999). The development and validation of the Psychological Vulnerability Scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23(2), 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Stride CB, Gardner SE, Catley N, & Thomas F (2016). Mplus code for mediation, moderation and moderated mediation models (1–80). Retrieved from www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/mplusmedmod.htm

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, & Pivik J (1995). The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7(4), 524–532. Doi:10.1037//1040-3590.7.4.524 [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, & Kirsch I (2001). Catastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain, 91(1–2), 147–54. Doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00430-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (1982). Life stress, social support, and psychological vulnerability: Epidemiological considerations . Journal of Community Psychology, 10(4), 341–362. Doi:10.1002/1520-6629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, & Foa EB (2006). Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 959–992. Doi:10.1037/1942-9681.S.1.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, & Filipas HH (2001). Predictors of PTSD symptom severity and social reactions in sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(2), 369–389. Doi:10.1023/A:1011125220522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur AD, & Van Ryn M (1993). Social support and undermining in close relationships: their independent effects on the mental health of unemployed persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 350–359. Doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel L, & Marshall LL (2001). PTSD symptoms and partner abuse: Low income women at risk. J Trauma Stress 14:569–84. Doi:10.1023/A:1011116824613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The ptsd checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. (1974). The provisions of social relationships In: Rubin Z, (Ed.), Doing unto others. (pp. 17–26). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 20–47. Doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 98(Supplement 1–2), S29–S37. Doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]