Abstract

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an infrequent cause of acute myocardial ischemia and is associated with various pathophysiologies, such as pregnancy, postpartum, and collagen diseases. It is frequently fatal and most cases are diagnosed at autopsy. Therefore, the early diagnosis of SCAD and initiation of treatment may be life saving. In this report, we describe a case of SCAD of right coronary artery, possibly triggered by transient high blood pressure, with no apparent atherosclerotic involvement detected by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and successfully treated with stent implantation. The IVUS helped us to confirm the diagnosis, navigate the guidewire into the true lumen, and understand the mechanism for the appearance of a lotus root formation.

Keywords: Coronary dissection, Myocardial infarction, Intravascular ultrasound

Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is infrequent, but may sometimes result in acute coronary syndrome and sudden cardiac death 1, 2, 3, 4. It is often fatal and is mostly recognized at postmortem examination in young victims of sudden death [5]. Therefore, its diagnosis might be underestimated and its natural history has not been elucidated.

We report on a case of SCAD involving the right coronary artery (RCA) in a middle-aged woman, presenting with acute myocardial infarction. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent implantation was performed on the basis of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging. IVUS imaging was useful diagnostically and for navigating the guidewire into the true lumen, despite a good angiographic appearance.

Case report

A 50-year-old woman presented with an acute myocardial infarction. She suddenly experienced severe chest pain after straining to have a bowel movement. She visited her local hospital and was subsequently transferred to our hospital. With the exception of slightly elevated blood cholesterol, she had no risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis. There was no family history of sudden death and no history of connective tissue disease, drug abuse, or recent trauma. She was not postmenopausal. Acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed, based on inferior electrocardiographic (ECG) changes showing ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, along with reciprocal ST-segment depression in leads V2, V3, V4, and V5, and raised creatine kinase-MB (179 U/L; local reference limit, 23 U/L). Low-molecular-weight heparin, aspirin, nitroglycerin, and clopidogrel were prescribed, but she continued to experience chest pain and was referred for cardiac catheterization. Coronary angiography revealed a total occlusion and the presence of a thin longitudinal radiolucent line representing an intimal medial flap with contrast staining developed from the ostium of the RCA to near the posterior descending artery bifurcation site (Fig. 1A). Her left coronary artery was smooth walled with no evidence of atherosclerosis. With ongoing symptoms and persisting ST elevation of the ECG, PCI was undertaken on the RCA. The lesion was crossed with a 0.014-in. guidewire (SION Blue, Asahi Intecc Co. Ltd., Aichi, Japan), which was steered into the distal-RCA with angiographic guidance. Subsequently, a 40 MHz IVUS catheter (ViewIt, Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was advanced into the RCA to investigate the extent of the dissection and to confirm the correct placement of the guidewire. The IVUS showed extensive circumferential dissection, with a mobile intimal flap and mobile thrombus, extending deep into the media layer from the proximal to the distal RCA with the true lumen collapsed due to a false lumen, suggesting SCAD. There was no evidence of atherosclerotic change on the IVUS. However, the guidewire and IVUS catheter had been placed within the false lumen (Fig. 1B). Therefore, our intention was to cross another wire into the true lumen under IVUS guidance. The IVUS was positioned at the dissection entrance site, and a second guidewire (Fielder FC, Asahi Intecc Co. Ltd.) was introduced into the true lumen under IVUS guidance after several attempts (Fig. 2A). After the advancement of the second guidewire into the true lumen, the IVUS examination was repeated. The IVUS showed multiple channels within mobile thrombus similar to a lotus root form proximal to the posterior descending artery bifurcation site of the RCA (Fig. 2B–D) even only 5 hours after the onset of chest pain. A 3.5 × 30 mm drug-eluting stent (Endeavor sprint, Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) was deployed only at the dissection entry point, whereas others propose sealing the entire dissection to avoid distal progression. A final IVUS examination demonstrated partial sealing of the dissection, with good stent apposition.

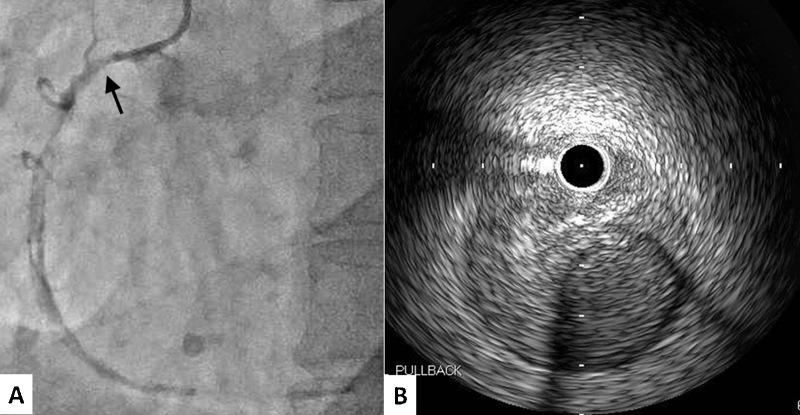

Fig. 1.

Long-axis oblique projection showing total occlusion and contrast media staining developed from the ostium of the right coronary artery to near the posterior descending artery bifurcation site (A). An arrow marks position of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) transducer at time of image acquisition. The initial IVUS showed the guidewire and IVUS catheter placed within the false lumen (B).

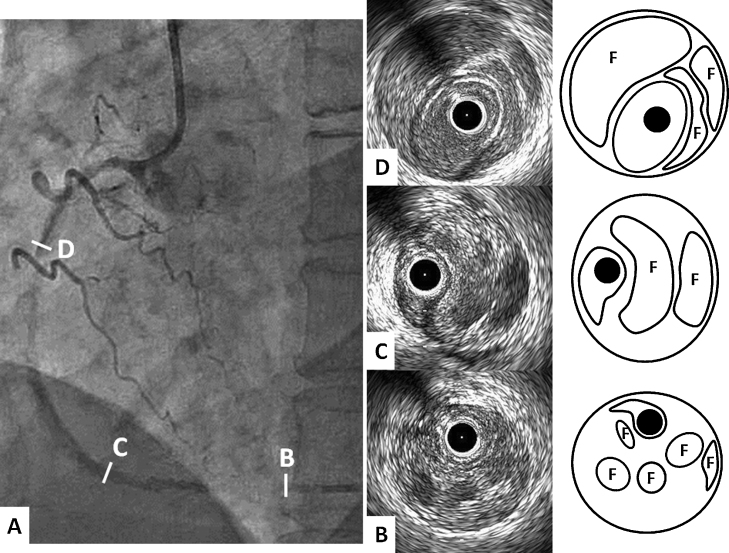

Fig. 2.

Coronary angiography taken before the intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) navigating the guidewire into the true lumen (A). The IVUS findings and schematic illustration of the right coronary artery (RCA). Multiple channels separated by clots were observed in the entire segments of the RCA. The channels were unified to be a single lumen in the ostial RCA (B–D). F indicates false lumen on the illustrations.

Her chest symptoms disappeared completely and ST-segment elevation on the ECG resolved after the intervention and she was discharged on aspirin and clopidogrel. She is currently asymptomatic and a repeated coronary angiogram is planned six months after the intervention.

Discussion

In this case, IVUS allowed us to: (a) understand the time course of a lotus root formation; (b) confirm the diagnosis; (c) navigate the guidewire into the true lumen; (d) determine the diameter of the vessel segment stented; and (e) confirm the result following stent implantation.

SCAD is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome first described in 1931 [6]. The ratio of female to male is 2:1 and the dissection is more frequently diagnosed in the left coronary artery [7]. Coronary artery dissection is characterized by a separation of the layers of the artery wall. This results in the formation of an intramural hematoma in the media of the arterial wall that creates a false lumen. Expansion of this lumen through blood or clot accumulation leads to compression of the real lumen with myocardial ischemia. Previous IVUS studies reported a multiple channel appearance in the false lumen of the dissected arteries 8, 9. In this case, the IVUS images demonstrated that this phenomenon could be observed only 5 hours after the onset of chest pain. We speculate that it was due to spontaneous recanalization because of hyperfibrinolysis by upregulation of plasminogen activators immediately after the formation of an intramural hematoma in the subintimal space. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of reporting the time course of lotus root formation. The etiopathologic mechanism that caused SCAD in this case remains unclear, however, we postulate that straining to have a bowel movement induced a rapid rise in blood pressure leading to SCAD.

There are no guidelines established to guide optimal treatment of patients with SCAD. The potential therapy includes medical therapy and revascularization with either PCI or coronary artery bypass graft. In our case, the patient was clinically unstable because of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and for this reason a conservative approach was not chosen. It is appropriate for many cases and is particularly indicated in hemodynamically unstable patients, such as those with acute myocardial infarction. Coronary luminal imaging using IVUS may help guide PCI procedures for SCAD. This can resolve diagnostic uncertainty, for example, where there is no contrast penetration of the false lumen, and to identify clearly the extent of the false lumen with respect to anatomical landmarks. Also, IVUS helps to ensure accurate guidewire placement in the true lumen and appropriate stent diameter. In our case, IVUS images easily navigated the guidewire placement from the false lumen into the true lumen.

References

- 1.Iskandrian A.S., Bemis C.E., Kimbiris D., Mintz G.S., Hakki A. Primary coronary artery dissection. Chest. 1985;87:227–228. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorgensen M.B., Aharonian V., Mansukhani P., Mahrer P. Spontaneous coronary dissection: a cluster of cases with this rare finding. Am Heart J. 1994;127:1382–1387. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celik S., Sagcan A., Altintig A., Yuskel M., Akin M., Kultursay H. Primary spontaneous coronary dissections in atherosclerotic patients. Report of nine cases with review of the pertinent literature. Eur J Card Surg. 2001;20:573–576. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basso C., Morgagni G.L., Thiene G. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a neglected cause of acute myocardial ischaemia and sudden death. Heart. 1996;75:451–454. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMaio S., Kinsella S., Silverman M.E. Clinical course and long term prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:471–474. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pretty H.C. Dissecting aneurysm of coronary artery in a woman aged 42. BMJ. 1931;i:667. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma P.K., Sandhu M.S., Mittal B.R., Aggarwal N., Kumar A., Mayank M., Bhattacharya A., Anand R.K., Grover A. Large spontaneous coronary artery dissections: a study of three cases, literature review, and possible therapeutic strategies. Angiology. 2004;55:309–318. doi: 10.1177/000331970405500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terashima M., Awano K., Honda Y., Yoshino N., Mori T., Fujita H., Ohashi Y., Seguchi O., Kobayashi K., Yamagishi M., Fitzgerald P.J., Yock P.G., Maeda K. Images in cardiovascular medicine. “Arteries within the artery” after Kawasaki disease: a lotus root appearance by intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2002;106:887. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000030708.86783.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakanishi T., Kawata M., Matsuura T., Kuroda M., Mori K., Hirayama Y., Adachi K., Matsuura A., Sakamoto S. A case of coronary lesion with lotus root appearance treated by percutaneous coronary intervention with intravascular ultrasound guidance. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2010;25:131–134. doi: 10.1007/s12928-010-0022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]