Abstract

Congenital heart diseases may be seen isolated as well as in conjunction with other anomalies. Coarctation of aorta forms 6–8% of all congenital heart diseases. Most commonly, it is seen in conjunction with bicuspid aortic valve. Both disorders may be seen together with anomalies of coronary artery. We present here a case presenting with shortness of breath and diagnosed with coarctation of aorta, bicuspid aortic valve, and serious aortic stenosis together with a fistula between circumflex artery and descending aorta for which we recommended surgery.

Keywords: Coarctation of aorta, Bicuspid aortic valve, Circumflex artery, Fistula

Introduction

Coarctation of the aorta is a term usually used for stenosis located in ligamentum arteriosis of aorta. Coarctation of aorta, which forms 6–8% of all congenital heart diseases, may be seen alone or in conjunction with other anomalies of heart and vessels [1]. Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) may lead to aortic stenosis or regurgitation and may be seen in conjunction with coronary artery anomalies [2].

Congenital coronary artery fistula is a rare, isolated anomaly of the coronary artery system. It is defined as a direct communication between a coronary and another vascular structure [3]. Approximately, 20–45% are in conjunction with other congenital heart diseases such as tetralogy of Fallot, atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Right coronary artery is most commonly involved. Most coronary artery fistulas drain into right cardiac chambers. The other coronary arteries are involved rarely [4].

We present here a case presenting with shortness of breath and diagnosed with coarctation of aorta, BAV, and serious aortic stenosis together with a fistula between circumflex artery and descending aorta who we recommended for surgery.

Case report

A 66-year-old male patient presented to our clinic with exertional dyspnea for 5 years, which had been worsening over the previous year. On physical examination, blood pressure of upper extremity was 140/80 mmHg (no pressure difference between right and left upper extremities) while that of lower extremities was 100/50 mmHg and heart rate was 77 beats/min and arrhythmic. S1 was normal while S2 was hard and paired. S4 was heard but not S3. A 3/6 midsystolic, 2/6, and also 2/6 pansystolic murmurs were heard at aortic, mitral, and tricuspid foci, respectively.

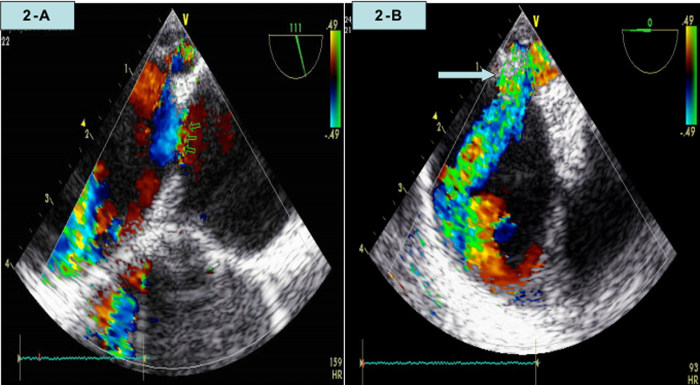

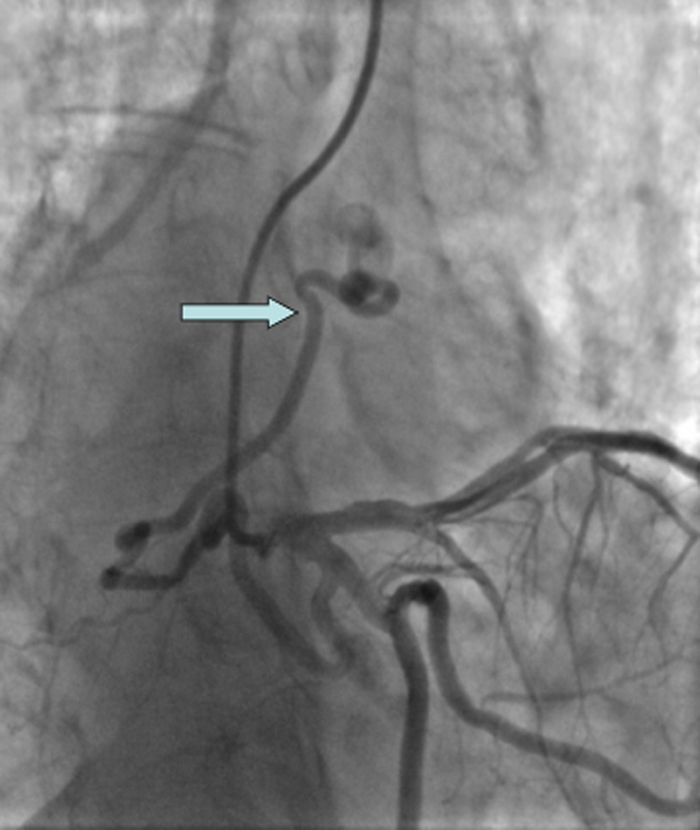

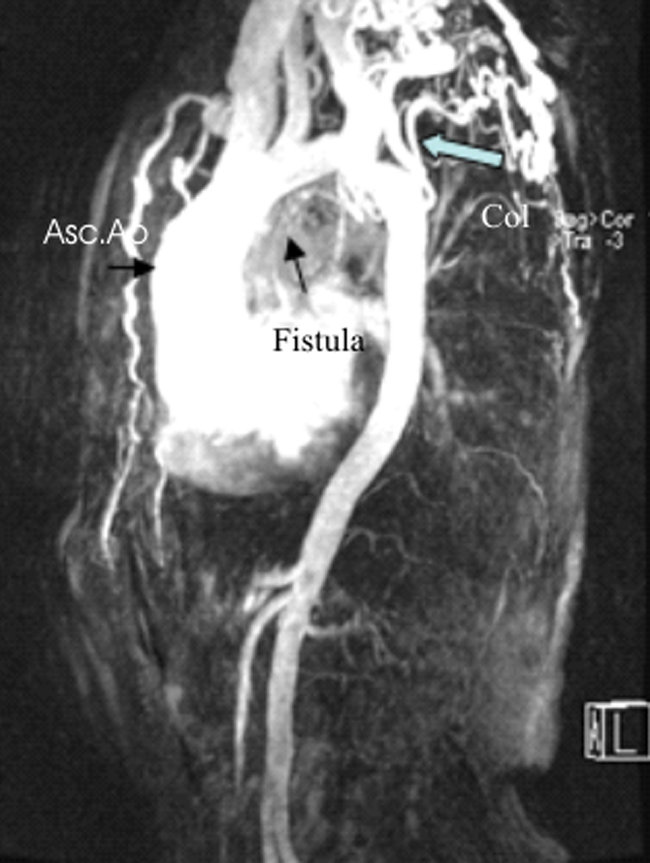

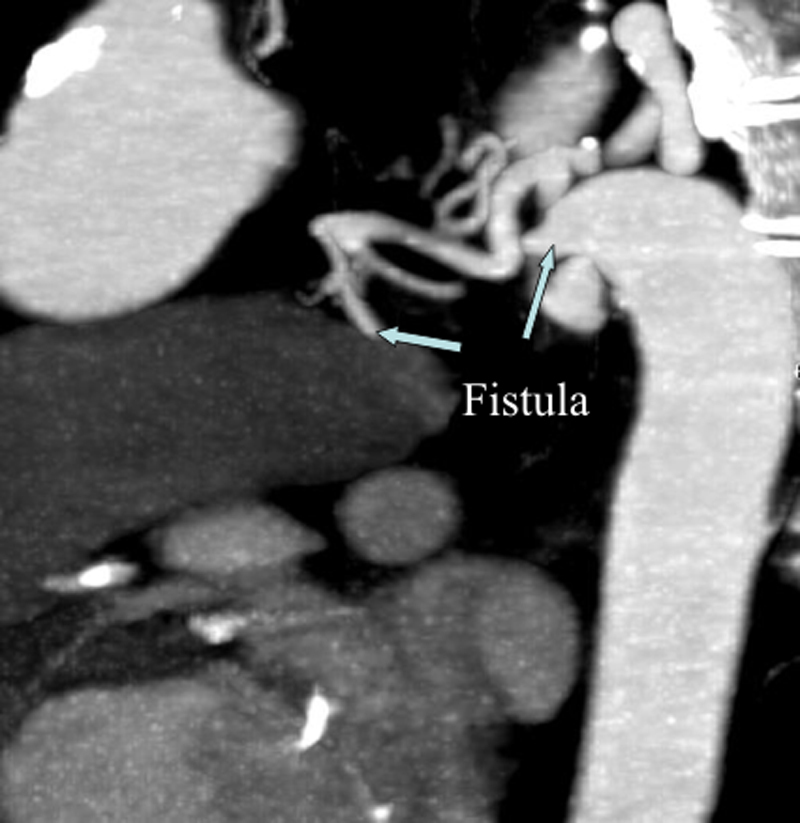

Electrocardiographic findings included a normal sinus rhythm with a rate of 92 beats/min, right bundle branch block, left anterior hemiblock, and frequent ventricular extrasystoles. Chest X-ray revealed an increased cardio-thoracic index, clear sinuses, prominent aortic arch and a wide mediastinum. Transthoracic echocardiographic (TTE) findings included increased left ventricle wall thickness, widened left cardiac chambers, and ascending aorta (55 mm at the level of valsalva sinuses and 46 mm after sinotubular junction). Systolic dysfunction was detected at both ventricles [left ventricle ejection fraction (EF) 30%, right ventricle EF 35%]. Aortic valve was bicuspid in structure and its’ opening was decreased (valve area of 1 cm2 via planimetry and of 0.8 cm2 according to the continuity equation). Maximum and mean pressures on aortic valve were 56 and 36 mmHg via continuous wave (CW) Doppler, and these findings suggested a severe aortic valve stenosis. Moderate mitral and aortic and severe tricuspid insufficiencies were detected via color Doppler ultrasound. Pulmonary artery pressure calculated via tricuspid insufficiency was 60 mmHg. Although a turbulent flow was observed via color Doppler ultrasound over descending aorta in suprasternal analysis, the highest pressure measured over it was 35 mmHg via CW Doppler. Transesophageal echocardiographic (TEE) findings included a BAV (Fig. 1), color crossover in color Doppler ultrasound between aortic arch and descending aorta (Fig. 2A) and collateral flow draining into descending aorta (Fig. 2B). Catheter used in femoral intervention could not be pushed forward toward proximal area in coronary angiography. Coronary angiography was performed via right brachial artery. A convoluted fistula was observed, whose origin was circumflex artery and area of drainage could not be detected (Fig. 3). Findings of aortography included a widened aortic root and ascending aorta along with a substantially decreased crossover of contrast-material after left subclavian artery part of aorta. The blood flow of distal parts was observed to be via collateral vessels. Pressures of ascending aorta and femoral artery were 130/85 mmHg and 75/45 mmHg, respectively. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed that coarctation area and collateral veins drained into distal aorta. Besides, fistula, originating from circumflex artery as a silhouette, was shown to be associated with descending aorta (Fig. 4). Many arterial collaterals providing associations with distal parts were observed in upper thoracic prevertebral area and a coarctation with a preocclusive appearance (99%) was detected in short segment of aorta in computed tomography angiography. Supravalvular ascending aorta was wide and a widening was detected in proximal of left subclavian artery, left common carotid artery, and brachiocephalic trunk. Besides, it was seen that the fistula originating from circumflex artery which was convoluted in structure drained into the descending aorta (Fig. 5). Once he was discussed at the cardiology-cardiovascular surgery conference, the decision for surgery was made as these findings were taken into consideration. He was discharged from the hospital with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, statin, and spironolactone since he declined the surgery, and was told to comply with follow-up visits.

Fig. 1.

Transesophageal echocardiography showing a bicuspid aortic valve (arrows).

Fig. 2.

Color crossover in color Doppler ultrasound between aortic arch and descending aorta (A) and collateral flow draining into descending aorta (B).

Fig. 3.

Coronary angiography showing origin of fistula from circumflex artery.

Fig. 4.

Fistula, originating from circumflex artery as a silhouette, was shown to be associated with descending aorta in magnetic resonance angiography. Asc.Ao, ascending aorta; Col, collateral vessels.

Fig. 5.

Fistula was originating from circumflex artery which was convoluted in structure drained into descending aorta in computed tomography angiography.

Discussion

Coarctation of aorta forms 6–8% of all congenital heart diseases and is seen in males more than females (M/F = 1.5/1). It may be seen alone or in conjunction with ventricular septal defect (VSD), PDA, intracranial aneurysm, subaortic stenosis, mitral valve anomalies, and BAV, as the last one being the most common accompanying anomaly [1].

BAV, although mostly sporadic, may be a congenital heart disorder which is seen in 1–2% of the general population and in 10–17% of first degree relatives. It is mostly seen in conjunction with coarctation of aorta (50–80%) [2]. BAV may lead to aortic valve stenosis and insufficiency. Aortic valve stenosis, the most common complication of BAV, is seen in 50% of cases. Stenosis demonstrates a rapid progression and is seen in early decades (fourth) [2]. Although rare, BAV may be seen in conjunction with coronary artery anomalies. Congenital coronary artery fistula was first defined by Krause in 1865 [5]. From 55% to 80% of all cases are isolated whereas the remaining 20–45% are in conjunction with other congenital heart diseases. These include tetralogy of Fallot, ASD, VSD, and PDA. Up to 92% of coronary artery fistula drain into right cardiac chambers whereas the rest, 8%, go into the left. Most common involvement area is right coronary artery followed by left anterior descending artery, both the right coronary artery and left anterior descending artery, circumflex artery, diagonal artery, and marginal artery as 50–60%, 25–42%, 5%, 18%, 1.9% and 0.7%, respectively. Left main coronary artery is a rare place for involvement [4]. Coronary artery fistula may cause angina, dyspnea, heart failure, and arrhythmias. It may cause so-called machinery murmur heard at left or right parasternal area.

TTE and TEE are foremost diagnostic modalities for detection of cardiac anomalies. Anatomy of coarctation, existence of collaterals, and vascular abnormalities may be detected by means of magnetic resonance imaging and, as an alternative, computed tomography angiography. Besides, information may be gathered regarding nature of stenosis, increased pressure on coarctation, existence of collateral and formation of aneurysm by means of aortography and catheterization [6].

Conclusion

Diagnosis of congenital heart diseases may be overlooked even until adult ages. The diagnosis is established either by incidental detection of a murmur or by interrogation of patient's complaint. The diagnosis not established until adult ages may be related either to presence of other accompanying anomalies retarding symptoms – such as collateral circulation – or to presence of insignificant anomalies in hemodynamic terms. Congenital heart diseases may be isolated or in conjunction with other anomalies. Presence of additional anomalies should be investigated even in cases when a congenital heart disease is diagnosed at older ages. The treatment, by the way, should be provided in the light of guidelines as well as taking the patient's preference into consideration.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest that should be declared.

References

- 1.Silversides C.K., Kiess M., Beauchesne L., Bradley T., Connelly M., Niwa K., Mulder B., Webb G., Colman J., Therrien J. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: outflow tract obstruction, coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, Ebstein anomaly and Marfan's syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:e80–e97. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70355-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Mozzi P., Longo U.G., Galanti G., Maffulli N. Bicuspid aortic valve: a literature review and its impact on sport activity. Br Med Bull. 2008;85:63–85. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koneru J., Samuel A., Joshi M., Hamden A., Shamoon F.E., Bikkina M. Coronary anomaly and coronary artery fistula as cause of angina pectoris with literature review. Case Rep Vasc Med. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/486187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chowdhury U.K., Rizhvi A., Sheil A., Jagia P., Mittal C.M., Govindappa R.M., Malhotra P. Successful surgical correction of a patient with congenital coronary arteriovenous fistula between left main coronary artery and right superior cavo-atrial junction. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2009;50:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause W. Uber den Ursprung einer accessorischen A, coronaria cordis aus der A pulmonalis. Z Rat Med. 1865;24:225–227. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stougiannos P.N., Danias P.G., Karatzis E.N., Kakkavas A.T., Trikas A.G. Incidental diagnosis of a large coronary fistula: angiographic and cardiac MRI findings. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2011;52:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]