Abstract

Interventions based on applied behavior analysis (ABA) have been shown to be effective for children with a wide range of cognitive, adaptive, and functional abilities. Many special education teachers understand the principles of ABA and are adept at implementing ABA interventions for students. However, as the principles of ABA can be complex, communicating with parents about ABA interventions can be challenging. Providing parents with clear and succinct information in the form of a brief customized reference guide can be instrumental for facilitating and extending communication about their child’s behavioral interventions. This article provides school personnel with guidelines and resources for helping parents understand and use interventions that are based on ABA. Specifically, this article presents 10 steps for creating an information guide for parents and provides recommendations for explaining the guide to parents.

Keywords: Parent collaboration, Applied behavior analysis, Behavior intervention plan

Mrs. Greenburg had been holding out hope that her son Tommy would “grow out” of his challenging behaviors, but his behaviors only worsened as he grew older. Now Mrs. Greenburg had to attend her first individualized education program (IEP) meeting and try to understand the strategies the teachers would use to help Tommy. The IEP team members talked about teaching Tommy to ask for a break when he needs one in order to decrease his tantrums and increase his work completion. That sounded like a good idea to Mrs. Greenburg. But she started feeling confused and a little overwhelmed when the team began talking about applied behavior analysis (ABA), which they said was the basis for Tommy’s interventions. The team members discussed differential reinforcement, collecting data, and graphing Tommy’s progress. By the end of the meeting, Mrs. Greenburg’s head was spinning. “There’s no way I’m going to remember all of this,” she said. “Do you have an information guide you can give me that I can review at home?”

ABA is an evidenced-based framework from which basic principles of behavior change are applied to socially significant behaviors, specifically to increase desired behaviors and decrease undesired behaviors (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968; Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). A common misconception is that ABA interventions are only suitable for students with autism spectrum disorder (Ross, 2007). In fact, the principles of ABA are effectively applied to behaviors encompassing social, functional, and academic contexts across age and ability levels (e.g., Briesch & Briesch, 2016; Didden, Duker, & Korzilius, 1997; Joseph, Alber-Morgan, & Neef, 2016). Students identified with disabilities may present different challenging behaviors that interfere in various ways with their academic achievement. Lin et al. (2013) documented the reciprocal relationship between problem behaviors and low academic achievement, a vicious cycle that worsens as students get older. Helping students achieve success in the classroom is socially significant, and using ABA as the basis for interventions will benefit students with a wide range of learning needs (Bloh & Axelrod, 2008).

Research has demonstrated parent involvement results in positive outcomes for a wide range of students across academic skills and social behaviors (e.g., Dalun, Hsein-Yuan, Oi-man, Benz, & Bowman-Perrott, 2011; Egbert & Salsbury, 2009; Gonida & Cortina, 2014; McNeal, 2014; Nokali, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010). However, although many special education teachers (at times under the guidance of a behavior analyst) understand the principles of ABA and are adept at implementing ABA interventions, they still may find it challenging to communicate these ideas to parents. As effective communication with parents is a critical factor for promoting student success in school, special education teachers can use this guide to assist with communicating the principles of ABA to parents. The purpose of this article is to provide practitioners with a tool for helping parents understand ABA interventions. Specifically, this article presents steps for creating a parent guide and suggestions for explaining the guide.

Why Create a Parent Guide?

Providing parents with clear and succinct information in the form of a brief reference guide can be instrumental for extending communication and facilitating parent involvement. Parents of students who are identified for special education services may be overwhelmed and confused when they are first introduced to IEP meetings and the various accompanying documents (Childre & Chambers, 2005; Fish, 2008; Gershwin-Mueller & Buckley, 2014; Stoner et al., 2005). The components of an IEP and the behavior intervention plan (BIP) include background information, standardized test scores, data from comprehensive assessments, present levels of performance, academic and social goals, and potential interventions. All of these components may be new to parents and not easily understood. Teachers can use this guide when developing BIPs for students as part of the IEP process or whenever they are using ABA strategies for an individual student.

For students receiving behavioral intervention services via behavioral goals on an IEP, the Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) of , 2004 requires parental consent for implementation of special education services, stating, “[The parent] understands and agrees in writing to the proposed activity” (34 CFR §§ 303.400–303.460). To be in compliance with the law, it is necessary to provide parents with a thorough explanation of their child’s interventions so they can provide informed consent. Additionally, many states/districts provide parents with a version of the Parental Rights and Procedural Safeguards document, such as the National Center for Learning Disabilities’ IDEA Parent Guide (Cortiella, 2006), which can be intimidating and confusing. This document is often lengthy and may not be helpful in assisting parents in understanding their rights and responsibilities. A simplified guide (such as this one) can lead to increased communication, collaboration, and trust between school personnel and parents.

Additionally, Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) are increasingly being hired by school districts to serve in supportive roles for students receiving special education services. According to Normand and Kohn (2013), approximately 89% of professionals with BCBA certification work with individuals with disabilities. Many of the instructional strategies based on the principles of ABA are ideal for interventions in schools because ABA encompasses the skills needed to improve behaviors in both general and special education classrooms, including management strategies both for the whole class and for students with individual BIPs (Gadke, Stratton, Kazmerski, & Rossen, 2016). The Behavior Analyst Certification Board’s (BACB’s) Professional and Ethical Compliance Code specifies, “Behavior analysts involve the client in the planning of and consent for behavior-change programs” (BACB, 2014, p. 12). As programs implementing strategies based on the principles of ABA can be complex, parents need to have a basic understanding of the behavioral interventions used with their child. That is, parents must understand the interventions well enough to provide consent for their use. A parent guide outlining the important principles of ABA and the interventions used with the student can be a helpful way to achieve this understanding. Finally, parent contributions to the development of BIPs and the IEP process are invaluable, yet lengthy documents and the terminology used may lead to confusion.

Not all school districts have a BCBA on staff to create a parent guide; however, many district personnel are qualified to provide basic information regarding ABA principles and interventions. These personnel may include school psychologists, special education teachers, and behavior specialists. The guide can be created in consultation with a BCBA and members of the special education school team. Additionally, the guide can be customized by the school team so it can be used to meet the needs of the school or district. Once the guide is created, it can be used by any of these personnel during special education team meetings with parents. Reviewing the guide together with parents during an IEP meeting can help ensure that all team members are on the same page regarding service delivery for the student.

For these reasons, the authors developed 10 steps for creating the guide by identifying critical information parents need to know about their child’s ABA interventions and by logically sequencing that information from simple to complex. Steps 1 through 6 are sequenced as follows: (a) a brief explanation of ABA, (b) definitions of basic ABA principles, (c) a summary of the BIP and its function, (d) descriptions of ABA interventions, (e) information about the types of data collected, and (f) examples of graphed data. The remaining steps address customizing the guide for the target student and enabling parents to access the information with ease by providing resources, a reference page, and a table of contents. Each step serves to enhance parent understanding of the interventions used with their child.

Creating a Parent Guide in 10 Steps

Depending on school district policy, parents can be provided with the guide prior to, during, or after the initial IEP meeting. This allows parents to have documentation and an explanation of their child’s interventions. The following are 10 steps for creating the parent guide.

To complete Step 1, provide a definition and brief explanation of ABA and describe how it is used in the school or classroom setting. Table 1 provides an illustration of how a textbook definition might be modified to become a parent-friendly one.

To complete Step 2, present information about common ABA terms. Include the definition of reinforcement along with clear and relatable examples. Explanations and examples should be brief but detailed enough for parents to understand, as illustrated in Table 2.

To complete Step 3, provide information about the BIP. Although the BIP is a separate document, it might be useful to include the following in the guide: the components of the BIP; how the BIP functions in the setting where services are provided; when, where, and how long services will be delivered; and the frequency of review. See Table 3 for an example of these materials.

To complete Step 4, provide a description of all commonly used strategies in the classroom. Use easy-to-understand language that is illustrated with examples. For instance, if self-graphing is an intervention used frequently in your setting, provide parents with detailed information of what students must do to monitor and graph their own behavior. See Table 4 for examples of commonly used strategies and interventions in classroom settings.

To complete Step 5, provide definitions of the types of data (e.g., frequency, duration) that are collected most often in your school setting. See Table 5 for an example.

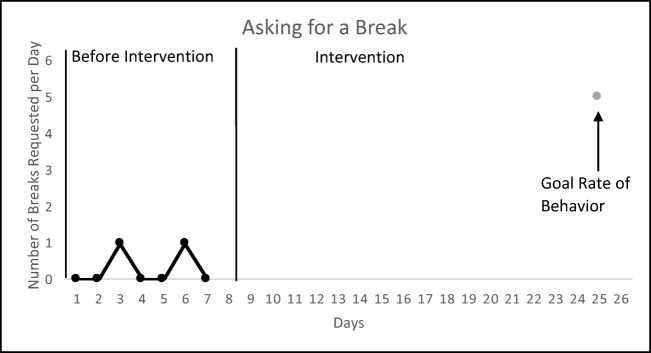

To complete Step 6, provide sample graphs showing desired behavior trends to help parents visualize the goal for successful intervention. Seeing preintervention (i.e., baseline) data with goal markers helps parents understand their child’s current challenges and expected rate of progress. Figure 1 shows an example of a graph illustrating a student’s preintervention data and the goal for desired rates of behavior after the intervention starts. Keep graphs simple and intuitive.

Table 1.

Definition of ABA

| Formal Definition | Simplified Definition |

|---|---|

| Cooper et al. (2007) define ABA as “the science in which tactics derived from the principles of behavior are applied to improve socially significant behavior and experimentation is used to identify the variables responsible for the improvement in behavior” (p. 20). | In simpler terms, ABA uses interventions that are supported by research. The interventions are used to improve socially significant human behaviors. Socially significant behaviors are those that are important to the child’s development. The main areas of development are social skills, language, academics, daily living, self-care, and vocational abilities. |

Table 2.

Definition of reinforcement and examples

| Definition | Examples |

|---|---|

| Reinforcement is a procedure used to increase the likelihood that the behavior will occur again the future. |

Example: Tommy often ignores his teacher’s directions to clean up. Today, when the teacher said it was time to clean up, Tommy put away all of his materials. Immediately after he put his materials away, the teacher praised Tommy and gave him a sticker on his sticker chart. Tommy’s cleaning up increased because he wanted praise and a sticker. Example: Tommy often wanders around the room during morning work time. Today, Tommy completed all of his morning work before the bell rang. As a reward, his teacher took away one homework assignment for Tommy and all the other students who completed their morning work on time. Tommy’s morning work completion increased because he wanted to avoid doing a homework assignment. |

Table 3.

The ABCs and BIPs of ABA

| Antecedent (A) | Behavior (B) | Consequence (C) |

|---|---|---|

| What occurs in the setting immediately before the behavior of interest | What the behavior of interest looks like | What occurs in the setting immediately after the behavior of interest |

| Behavior Intervention Plans (BIPs) | ||

| In an ABC contingency, the teacher collects data by recording what happens in the child’s environment before the behavior and what happens after the behavior. She does this several times in order to find out why the behavior is occurring. There are four reasons why a child might engage in a behavior: to gain attention, to gain a tangible object (e.g., a toy), to escape or avoid something, or to access a sensory experience (e.g., hand flapping or thumb sucking). Based on this information, the team develops a BIP. The BIP outlines interventions that are designed to address the reason for the student’s behavior. An intervention can be used to teach the child a new behavior that is more desired in a school setting so that he can have access to the same reward. Alternative behaviors allow the student to receive, maintain, or escape something in a way that is more appropriate. For example, instead of screaming or shouting out for attention, a child could be taught to say “excuse me” or raise his hand. Additionally, an intervention can be used to teach a new skill. For example, a student who has difficulty talking can be taught to use pictures as a means of communicating his wants and needs. | ||

Table 4.

Common behavioral interventions

| Intervention | Description |

|---|---|

| Token economy | Token economies work much like money. Students earn tokens for which they can later trade for a desired item. This is often used to increase motivation for students to complete tasks or follow classroom rules. |

| Differential reinforcement | When using differential reinforcement, the teacher provides a reward for a good behavior that is an alternative to an inappropriate behavior. For example, the teacher praises the student when he is in his seat but does not give the student attention when he is out of his seat. |

| Self-monitoring | Self-monitoring is an intervention in which students are taught to track their own behaviors. For example, a teacher may teach a student to count the number of math problems he completes during independent work time. |

| Self-graphing | Self-graphing involves teaching the student to put data points on a graph that show the number of behaviors that occurred during a time period. For example, a student may count the number of words he writes in his journal each day and graph them. Self-graphing works for children who are motivated by their own success. |

Table 5.

Types of data collection

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Frequency | The number of times a behavior occurs |

| Duration | The amount of time a behavior occurs |

| Rate | The number of times a behavior occurs per minute/h, etc. |

| Trials to criterion | The number of learning sessions until the student masters the skill |

In ABA, decision making is data based; all interventions are evidence based, meaning there are data to support the intervention’s effectiveness. When using a BIP or teaching a skill, data are taken continuously to see if the intervention is working and if any changes need to be made to improve the intervention

Fig. 1.

Sample graph

The remaining four steps (i.e., 7–10) involve tailoring the guide for the specific student’s program.

To complete Step 7, customize and personalize the guide for the target student. Use the student’s name and target behaviors in the guide’s examples so parents understand how the guide will be used for their child (see Tables 2 and 4 for examples).

To complete Step 8, provide a list of resources for parents to seek additional information. These resources can include the district website, parent support groups, and links to popular ABA networks or conferences in your area. Table 6 shows a sample list of resources for parents. Examining resources should not be a requirement for parents; however, many parents are interested in seeking out additional information.

To complete Step 9, provide a reference page that lists relevant terms (e.g., “Behavior Intervention Plan”) and their corresponding acronyms (e.g., “BIP”).

To complete Step 10, include a table of contents with page numbers so all of the information can be found easily.

Table 6.

Sample list of resources

| Resource | Type of Resource |

|---|---|

|

Association for Behavior Analysis International |

Conferences, journal articles, educational videos |

| Buchannan, S. M., & Weiss, M. J. (2010). Applied behavior analysis and autism: An introduction. Robbinsville, NJ: Autism New Jersey. | Book (overview of ABA) |

|

Center for Parent Information and Resources |

Support groups, parent resources |

|

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports |

Parent resources for interventions |

|

List of regional conferences for parents to attend http://ohaba.org/ (e.g., the Ohio Association for Behavior Analysis annual conference, April 7–8, 2017) |

Conference |

Explaining the Parent Guide

Once the parent guide is created, the team will need to carefully and thoroughly explain it to the parents. School teams should arrange a time to meet with parents in compliance with school district policy. The team should explain each section of the guide and encourage parents to ask questions. The team should read the definition of ABA and provide parents with a specific example of the socially significant behavior targeted for their child. For example, “We will use interventions that are supported by research to increase Tommy’s ability to ask for a break when he needs one.” The team should also provide parents with an explanation of the basic principles of ABA through examples of how the principles will be used with their child. To prevent confusion, avoid using technical terms or jargon. For example, “Tommy often wanders around the classroom when his teacher asks him to do his morning work. We would like Tommy to complete his work, and then we will reward him by letting him do an activity he likes.”

Communicate with parents exactly how, when, where, and how often the ABA interventions will be used. For example,

We are going to give Tommy reinforcement [or a reward] when he engages in a behavior we want to see in the classroom, but we will not provide reinforcement when he engages in a behavior we do not want to see. For example, we are going to use a break card to teach Tommy to ask for a break instead of crying, throwing a tantrum, or wandering around the classroom. The card has the words “I need a break” printed on it [show the card]. When Tommy gives the card to his teacher, he will be allowed to take a 3-minute break from his classwork. During his break, he will be allowed to choose an activity, such as going to the reading corner, taking a walk with the classroom aide, running a special errand for the teacher, drawing on his notepad, or sitting quietly in the relaxation area of the room. When Tommy’s break is over, the teacher will ask him to continue the task he was doing before he asked for the break. We will only allow Tommy to take a break when he uses the break card, but he will not get a break when he tantrums.

Encourage parents to ask questions (e.g., “How many breaks is he allowed to take?”) and respond to the questions according to the child’s BIP and the protocol in place for your school. For example, “If he asks for more than five breaks within an hour, we will give him a limited number of break cards to help him manage when he really needs a break. Once he uses all his break cards, he will have to wait until the end of the class period to get more.”

The next step is to review information about the BIP. Explain how the BIP is used, reviewed, and modified. For example,

We use a BIP to outline all of the interventions we be will using with Tommy. We will count and record the number of times per day Tommy engages in the appropriate behavior prior to the intervention. Then we will make a goal for that behavior. For instance, our goal for Tommy’s asking for a break is five times per day. Once we have a goal, we will start the intervention and compare Tommy’s behavior before and after the intervention. We will review the data weekly and, if necessary, make changes to the intervention so Tommy can successfully meet the goal.

After data collection and goals are discussed, provide information about how often the team will meet to review the data. For example, “We will meet as a team every 6 to 8 weeks to look at Tommy’s data and determine how well the interventions are working. Based on the data, we may adjust the interventions to help Tommy become more successful.” Emphasize that the parent can request to review the data at any point independent of a scheduled meeting. Next, discuss data collection and provide specific explanations of how each measurable dimension of behavior will be used with the child. For example, “We are going to be counting the number of times Tommy asks for a break each day. His teachers are going to make a tally mark on this data sheet [show the data sheet] every time he asks for a break. At the end of the day, the teacher will record the number of breaks on Tommy’s graph.” Show parents the sample graphs you have created (see Fig. 1). Point out the student’s current performance and future goal. For example, “Tommy currently does not ask for a break on most days. This graph shows the number of times he has asked for a break over the last 7 days. His goal for asking for a break should be five times each day. So, the goal marker shown on the graph is five.”

Encourage parents to provide feedback regarding their feelings toward the interventions used in the BIP. Emphasize that parents are entitled to request revisions and modification to the BIP at any time. At the end of the meeting, provide parents with an opportunity to ask any further questions. Also, provide your contact information and encourage parents to contact you before the next meeting if they have any questions regarding the ABA guide or the interventions implemented with their child. Check back with parents regularly to seek and offer any additional information and updates.

Key Aspects of a Parent Guide

Parent guides can vary across school districts based on the cultural characteristics of a school’s community and individual district policies; however, parent guides should have the following key aspects in common. First, the guide should focus on increasing appropriate student behaviors and decreasing inappropriate behaviors. Examples of appropriate behaviors may include paying attention during instruction, taking notes, completing assignments, and following the rules. If one of the behavioral goals is to decrease an inappropriate behavior (e.g., calling out, running out of the classroom, swearing), the behavior plan should also include goals to increase specific appropriate behaviors (e.g., asking for help politely, sharing materials, working quietly). Second, the guide should be kept as brief as possible (i.e., five to seven pages) while providing succinct and clear information for parents to better understand the behavioral interventions. Finally, the guide should be accessible to all parents (e.g., translated into their first language or revised to meet various reading levels of parents).

Cultural Considerations

In order to ensure accessibility, professionals should consider the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse parents, as well as the needs of parents with varying levels of education. When working with culturally diverse families, it is important to develop self-awareness about one’s own cultural biases and examine how those biases might interfere with communication with families (Bradshaw, 2013). Fong, Catagnus, Brodhead, Quigley, and Field (2016) provide the following recommendations for developing cultural awareness: consider the language of assessment, conduct an analysis of cultural identity, and use culturally responsive practice resources that are readily available (e.g., Bradshaw, 2013; Fong & Tanaka, 2013; Salend & Taylor, 2002; Sugai, O’Keeffe, & Fallon, 2012).

A culturally responsive practitioner uses easy-to-understand language to define behavior and “ensure the behaviors are communicated in a positive manner using multiple forms of communication that are sensitive to potential cultural differences in eye contact, wait time, meanings of words, non-vocal body language, personal space, and quality of voice” (Fong et al., 2016, pp. 87–88). Additionally, being culturally responsive requires that professionals take into account family preferences and whether or not interventions may interfere with a family’s cultural norms.

Customizing the guide for individual students is one way to increase accessibility for diverse families. For parents who are not fluent in English, the guide should be translated into the parents’ first language. Providing a translation of the guide may be necessary for some parents, but it is probably not sufficient for achieving the desired level of understanding that results in effective communication. Part of customizing the guide is identifying and addressing the priorities of culturally diverse parents. For example, if a potential intervention incorporates teaching the student to make choices, it would be culturally responsive to find out from the parents if choice making is a priority and to what extent children are encouraged to make choices within that family’s culture.

Professionals must also be culturally responsive when explaining the guide to parents. Other factors to consider may include understanding how to communicate respect (e.g., eye contact, using titles such as ma’am or sir, level of formality), understanding family structure (e.g., hierarchy of authority, gender roles, conflict resolution), and understanding the extent to which the family is comfortable with sharing information (Bradshaw, 2013). It is recommended that school personnel reflect on these considerations, seek more information about a family’s culture, and make any necessary changes either to the guide or to the explanation of the guide that will best serve families who are culturally and linguistically diverse.

Discussion and Limitations

The steps for creating the parent guide were developed by the authors based on their expertise and their experiences working with parents of students with disabilities in school contexts. It is important to note that school teams and district teams can adjust components of the guide or explanation process to meet their needs. Additionally, changes should be made to increase feasibility of use within a district or school building.

Although this guide is designed to enhance communication with parents about behavioral interventions, parents’ knowledge of ABA or the acceptability of interventions has not been empirically tested. Additionally, the authors were unable to find empirical research examining parent guides in general. However, pediatric journals have published research indicating that combining verbal instructions with written instructions is more effective than only verbal instructions for improving knowledge and satisfaction of parents of children being discharged from the hospital (e.g., Al-Harthy et al., 2016; Johnson & Sanford, 2005). Furthermore, behavioral researchers have demonstrated positive effects using parent training packages that included both verbal and written instructions (e.g., Drifke, Tiger, & Wierzba, 2017; Lerman, Swiezy, Perkins-Parks, & Roane, 2000; Mueller et al., 2003). Because there is currently no published research examining the effects of a parent guide for ABA interventions, future research should explore the effects of a parent guide on a variety of variables that address both student and parent outcomes. For example, future research could empirically evaluate the effects of using a parent guide on overall rates of parents’ involvement and understanding of special education services provided to their child. Additionally, the authors encourage practitioners to modify the guide to best meet the diverse needs of parents in their local community.

Equipped with her parent guide and the ongoing support of the special education teacher, Mrs. Greenburg felt she understood Tommy’s ABA interventions. She was no longer overwhelmed by the IEP and BIP, and she was looking forward to attending a follow-up meeting 6 weeks later to learn about Tommy’s progress. At the next meeting, the special education teacher showed Mrs. Greenburg some graphs that depicted the number of times Tommy asked for a break and his behaviors related to academic achievement. Mrs. Greenburg could see Tommy was on track and making good progress.

Conclusion

When a student is first identified with disabilities, parents’ introduction to the world of special education can be confusing and stressful (Childre & Chambers, 2005; Fish, 2008; Gershwin-Mueller & Buckley, 2014; Stoner et al., 2005). To decrease anxiety and confusion regarding special education services, it may be helpful to provide parents with a guide detailing their child’s interventions. If a school team is using interventions that are grounded in the principles of ABA, it is important to provide parents with information about the science and specific interventions used with their child. It is also important to provide explanations that are clear and easy to understand. Parents’ understanding of their child’s behavioral interventions can be a vital component to a child’s success in school.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Maria R. Helton declares that she has no conflict of interest. Sheila R. Alber-Morgan declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Al-Harthy N, Sudersanadas KM, Al-Mutairi M, Vasudevan S, Saleh GB, Al-Mutairi M, Hussain LW. Efficacy of patient discharge instructions: A pointer toward caregiver friendly communication methods from pediatric emergency personnel. Journal of Family and Community Medicine. 2016;23(3):155–160. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.189128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Retrieved from https://bacb.com/ethics-code/

- Bloh C, Axelrod S. IDEIA and the means to change behavior should be enough: Growing support for using applied behavior analysis in the classroom. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention. 2008;5(2):52–56. doi: 10.1037/h0100419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw W. A framework for providing culturally responsive early intervention services. Young Exceptional Children. 2013;16(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/1096250612451757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briesch AM, Briesch JM. Meta-analysis of behavioral self-management interventions in single-case research. School Psychology Review. 2016;45(1):3–18. doi: 10.17105/SPR45-1.3-18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Childre A, Chambers CR. Family perceptions of student centered planning and IEP meetings. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;40:217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cortiella C. IDEA parent guide: A comprehensive guide to your rights and responsibilities under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) New York, NY: National Center for Learning Disabilities; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dalun Z, Hsein-Yuan H, Oi-man K, Benz M, Bowman-Perrott L. The impact of basic-level parent engagements on student achievement: Patterns associated with race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2011;22(1):28–39. doi: 10.1177/1044207310394447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Didden R, Duker PC, Korzilius H. Meta-analytic study on treatment effectiveness for problem behaviors with individuals who have mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1997;101(4):387–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drifke MA, Tiger JH, Wierzba BC. Using behavioral skills training to teach parents to implement three-step prompting: A component analysis. Learning and Motivation. 2017;57:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egbert J, Salsbury T. Out of complacency and into action: An exploration of professional development experiences in school/home literacy engagement. Teaching Education Journal. 2009;20:375–393. doi: 10.1080/10476210902998474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fish W. Perceptions of parents of students with autism towards the IEP meeting: A case study of one family support group chapter. Education. 2008;127:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Tanaka S. Multicultural alliance of behavior analysis standards for cultural competence in behavior analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2013;8(2):17–19. doi: 10.1037/h0100970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gadke DL, Stratton KK, Kazmerski GS, Rossen E. Understanding the board certified behavior analyst credential. Communique. 2016;45:17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin-Mueller T, Buckley PC. Fathers’ experiences with the special education system: The overlooked voice. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities. 2014;39(2):119–135. doi: 10.1177/1540796914544548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonida EN, Cortina KS. Parental involvement in homework: Relations with parents and student achievement-related motivational beliefs and achievement. British Journal of Education Psychology. 2014;84(3):376–396. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

- Johnson A, Sanford J. Written and verbal information versus verbal information only for patients being discharged from acute hospital settings to home: Systematic review. Health Education Research. 2005;20(4):423–429. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph LM, Alber-Morgan SR, Neef N. Applying behavior analytic procedures to effectively teach literacy skills in the classroom. Psychology in the Schools. 2016;53:73–89. doi: 10.1002/pits.21883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC, Swiezy N, Perkins-Parks S, Roane HS. Skill acquisition in parents of children with developmental disabilities: Interaction between skill type and instructional format. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21:183–196. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(00)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Morgan PL, Hillemeier M, Cook M, Maczuga S, Farkas G. Reading, mathematics, and behavioral difficulties interrelate: Evidence from a cross-lagged panel design and population-based sample of US upper elementary students. Behavioral Disorders. 2013;38:212–227. doi: 10.1177/019874291303800404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal RJ. Parent involvement, academic achievement, and the role of student attitudes and behaviors as mediators. Universal Journal of Educational Research. 2014;2(8):564–576. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M. M., Piazza, C. C., Moore, J. W., Kelley, M. E., Bethke, S. A., Pruett, A. E., … Layer, S. A. (2003). Training parents to implement pediatric feeding protocols. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 545–562. 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nokali NE, Bachman HJ, Votruba-Drzal E. Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development. 2010;81:988–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normand MP, Kohn CS. Don’t wag the dog: Extending the reach of behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 2013;36:109–122. doi: 10.1007/BF03392294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross KR. Beyond autism treatment: The application of applied behavior analysis in the treatment of emotional and psychological disorders. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2007;3:528–536. doi: 10.1037/h0100826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salend SJ, Taylor LS. Cultural perspectives: Missing pieces in the functional assessment process. Intervention in School and Clinic. 2002;38(2):104–112. doi: 10.1177/10534512020380020601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner JB, Bock SJ, Thompson JR, Angell ME, Heyl BS, Crowley EP. Welcome to our world: Parent perceptions of interactions between parents of young children with ASD and education professionals. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20:39–51. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200010401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugai G, O’Keeffe BV, Fallon LM. A contextual consideration of culture and school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;14(4):197–208. doi: 10.1177/1098300711426334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]