Abstract

Glucosinolate profiles significantly vary among Brassica rapa genotypes. However, the molecular basis of these variations is largely unknown. In this study, we investigated a major quantitative trait locus (QTL) controlling aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation in B. rapa leaves. The QTL, which encompasses three tandem MAM genes and two MYB genes, was detected in two BC2DH populations. Among the five-candidate genes, only the expression level of BrMAM-3 (Bra013007) was significantly correlated with the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa leaves. We identified a naturally occurring insertion within exon 1 of BrMAM-3, which is predicted to be a loss-of-function mutation, as confirmed by qRT-PCR. We determined that the loss of function was associated with the low glucosinolate content in B. rapa accessions. Furthermore, overexpressing the BrMAM-3 gene resulted in an increase in total aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis transgenic lines. Our study provides insights into the molecular mechanism underlying the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa leaves, thereby facilitating in the manipulation of total aliphatic glucosinolate content in Brassica crops.

Giving vegetables a nutritional upgrade

The identification of a gene controlling the production of a critical class of plant metabolites could enable researchers to engineer healthier crops. Vegetables such as cabbage and broccoli generate various glucosinolates as a defense mechanism against pests and disease. But these molecules also have nutritional and medicinal value, and researchers led by Xiaowu Wang at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences have homed in on a key step in their manufacturing process. Working with the model species Brassica rapa, Wang and colleagues learned that a gene called BrMAM-3 performs the critical first step in synthesizing a major class of glucosinolates. Manipulation of this gene as well as those encoding the enzymes that subsequently shape the functional characteristics of the resulting glucosinolates could yield enhanced vegetables that are even healthier for consumers.

Introduction

Glucosinolates are sulfur- and nitrogen-containing plant secondary metabolites that commonly occur in the order Brassicales, including important Brassica crops such as oilseed rape (B. napus), cabbage (B. oleracea, Capitata group), and broccoli (B. oleracea, Italica group), and the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Physical tissue or cell injury causes these amino acid-derived thioglycosides to co-occur with specific β-glucosidases called myrosinases and associated proteins, thereby generating an activated plant defense system known as the “mustard oil bomb”1. Glucosinolate derivatives such as isothiocyanates, thiocyanates, and nitriles have a wide range of biological functions, which include anti-carcinogenicity in humans2–6, anti-nutritional effects using seed meal in animals7, and insect pest repellent and fungal disease suppression8,9. Moreover, glucosinolates are responsible for the special flavors of Brassica vegetables such as B. rapa and B. oleacrea10,11. Due to their diverse roles in plant metabolism, animal nutrition, disease, and flavors, glucosinolates are a potential target for genetic manipulation and applications in crop improvement programs.

Glucosinolates are classified into aliphatic, aromatic, and indole glucosinolates, depending on their precursor amino acids12,13. Glucosinolate biosynthesis occurs in three independent stages: chain elongation of the precursor amino acid, formation of the core structure, and side-chain modifications. In A. thaliana, chain elongation is an iterative three-step process that operates predominantly on Met and results in up to six methylene groups, which contribute to the variations in glucosinolate structures. The committed step during Met side-chain elongation is catalyzed by methylthioalkylmalate synthase (MAM)12,14–16, which is derived from isopropylmalate synthase (IPMS) of Leu biosynthesis.17 Recent reports have confirmed that glucosinolate levels are controlled by at least six R2R3-MYB superfamily transcription factors18–23. In A. thaliana, the aliphatic glucosinolates genes are regulated by AtMYB28, AtMYB29, and AtMYB76 genes18–22, whereas AtMYB34, AtMYB51, and AtMYB122 control the formation of indole glucosinolates23. Additionally, MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis by directly interacting with glucosinolate-related MYBs24.

Brassica crops are of great economic importance to human beings because these are a rich source of beneficial health glucosinolates such as glucoraphanin and sulforaphane. Vegetable forms of B. rapa (Chinese cabbage, turnip, pakchoi, komatsuna, mizuna green, and rapini) are widely cultivated in many parts of the world25, and individual plants generally contain a limited number of major aliphatic glucosinolate profiles10,26. Glucosinolate content and profiles are highly variable and accession-specific in various B. rapa genotypes, in which the aliphatic (4C) 3-butenyl and the aliphatic (5C) 4-pentenyl glucosinolates are the predominant glucosinolates. To date, 102 putative genes of the glucosinolate biosynthesis pathway of B. rapa have been inferred by comparative genomic analyses27. The expression of seven MYB transcription factors in different organs of Chinese cabbage (B. rapa ssp. Pekinensis) has been investigated28. The expression profiles of BrMYB28 and BrMYB29 in stems differ from those in other organs28. In addition, three genes encoding AOP2 are differentially expressed in B. rapa29. However, more work is required to characterize the genes involved in glucosinolate biosynthesis in B. rapa.

The level and composition of aliphatic glucosinolates are under complex genetic control and are highly heritable30. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis is a powerful method to study the genetics underpinning quantitative variations in glucosinolate profiles and to estimate the number of variable loci affecting a trait.31 QTL analysis of seed and leaf glucosinolates has been conducted in A. thaliana9,14,32,33, B. oleracea34, B. napus35–37, B. juncea38,39, as well as B. rapa26. In Arabidopsis, the epistatic interaction of two major genetic QTL controlling total aliphatic glucosinolates that map to the GS-Elong (MAM1 and MAM-L) and GS-AOP loci regulate aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation14. In B. rapa, QTL analysis has identified 16 loci that control aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation, three loci that regulate total indolic glucosinolate concentration, and three loci that influence aromatic glucosinolate concentrations26. Although these reports have identified QTLs that control the variability of glucosinolate contents and profiles across Brassica species, its underlying molecular genetic mechanism remains unclear.

Genome polyploidization is an evolutionary process that fuels diversity in plant species40. Besides ancient whole-genome duplication events involving ancestral Arabidopsis and Brassica species41, Brassica crops underwent additional whole-genome triplication (WGT) events. These genome duplication events followed by gene losses during rediploidization resulted in highly complex relationships among the regulatory pathways of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Brassica species compared to that in Arabidopsis. The MAM genes are often found as clusters of tandem arrays and differentiated in the Arabidopsis and A. lyrata genomes9,12. In B. rapa, seven MAM genes, comprising five syntenic and two non-syntenic, have been identified27; however, their function in relation to glucosinolate accumulation is poorly understood.

In our previous study, we analyzed the phylogenetic and syntenic relationships of MAM genes from 13 sequenced Brassicaceae species. Based on these analyses, we proposed that the syntenic loci of MAM genes underwent lineage-specific evolution routes and were driven by positive selection after the divergence from Aethionema arabicum29. Upon the divergence of the Brassica genus, B. rapa retained five syntenic MAM genes that were generated via WGT followed by biased gene loss. BrMAM-1 and BrMAM-2 are clustered in the medium-fractionated subgenome (MF1), whereas BrMAM-3, BrMAM-4, and BrMAM-5 are clustered in the least-fractionated subgenome (LF). Furthermore, BrMAM-3 and BrMAM-1/2 are homologous genes. However, the contribution of these MAM genes in the observed variations in aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation of B. rapa remains unclear.

In this study, we investigated a major QTL locus controlling the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa leaves. The QTL locus includes a complex loci with three tandem MAM genes (BrMAM-3, BrMAM-4, and BrMAM-5) and a nearby loci with two MYB genes (BrMYB28.1 and BrMYB34.1). All these genes are possibly involved in controlling aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation in B. rapa. The present study was conducted to clarify the gene(s) contributing to the significant QTLs involved in glucosinolate composition and accumulation in B. rapa leaves. Our study may facilitate the genetic engineering of plants to accumulate glucosinolates without compromising overall plant fitness.

Results

Expression of BrMAM-3 is significantly associated with the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates

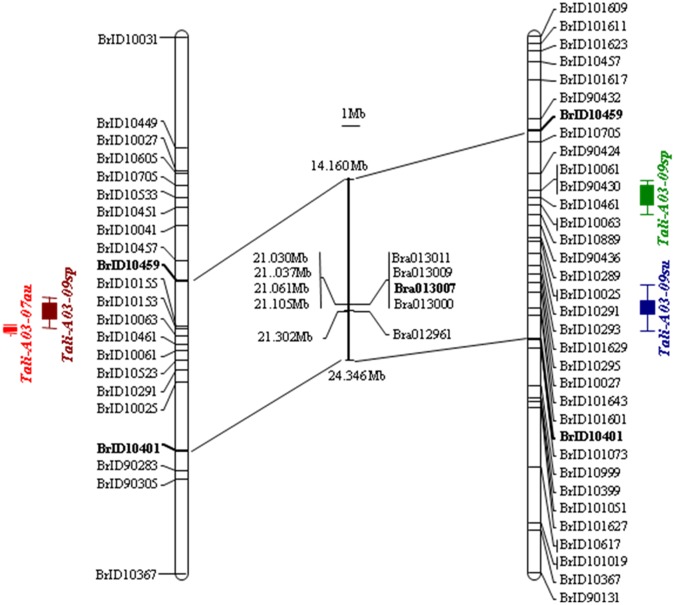

A major QTL locus on chromosome 3 was consistently detected by MapQTL4 in the RC_BC2DH and YS_BC2DH populations, which explained a large proportion (31.0% and 53.0%, respectively, in autumn of 2007 and spring of 2009; 29.0% and 12.9%, respectively, in spring of 2009 and summer of 2009) of the observed phenotypic variations in total aliphatic glucosinolates (Fig. 1). There are eight genes (Supplementary Table S1, S2) in the major QTL region and five were considered as candidate genes, including three tandem MAM genes, namely, BrMAM-3 (Bra013007), BrMAM-4 (Bra013009), and BrMAM-5(Bra013011), and two MYB genes, namely, BrMYB34 (Bra013000) and BrMYB28 (Bra012961).

Fig. 1. A major QTL locus on chromosome 3.

A major QTL was mapped to a ~10.185-Mb genomic DNA region between markers BrID10459 and BrID10401 in RC_BC2DH (a) and YS_BC2DH (b) populations in autumn of 2007 and the spring of 2009, and in the spring of 2009 and the summer of 2009, respectively

The association between the expression of candidate genes (Supplementary Table S3) and the glucosinolate profiles was analyzed in 52 double-haploid (DH) lines (Table 1). The profiles of eight glucosinolates, including three aliphatic,3-butenyl- (NAP), 4-pentenyl- (GBN), and 2-hydroxy-3-butenyl-glucosinolate (PRO), four indolic3-indolmethyl- (GBC), 1-methoxy-3-indoylmethyl- (NEO), 4-hydroxy-3-indoylmethyl- (4OH), and 4-methoxy-3-indoylmethyl-glucosinolate (4ME), and one aromatic glucosinolate, 2-phenylethyl-glucosinolate (NAS), were detected in all varieties. The total glucosinolate content in our collections ranged from 0.96 μmol g−1 dry weight (DW) to 46.02 μmol g−1 DW, with the aliphatic glucosinolates making up the highest ratio (75.5%, Table S1). NAP was the most abundant glucosinolate, with a mean content of about 3.98 μmol g−1 DW, representing 30.5% of the total glucosinolate content (Supplementary Table S4).

Table 1.

Correlation analysis between expression of candidate genes and dominant glucosinolates in Brassica rapa

| Genes | PRO | NAP | GBN | 4OH | GBC | NAS | 4ME | NEO | SUM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrMYB28.1 (Bra012961) | −0.06 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| P value | 0.66 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.08 |

| BrMYB34.1 (Bra13000) | −0.10 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| P value | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| BrMAM-3 (Bra013007) | −0.13 | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.14 | −0.06 | 0.57 |

| P value | 0.34 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.70 | <0.0001 |

| BrMAM-4 (Bra013009) | −0.06 | −0.14 | 0.24 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.16 | −0.03 |

| P value | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.81 |

| BrMAM-5 (Bra013011) | −0.11 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| P value | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.48 | 0.27 |

Among the five-candidate genes, BrMAM-3 (Bra013007) was significantly and positively associated with NAP (0.70) and the accumulation of total glucosinolates (0.57) (P < 0.001) as well as 4OH (0.43) (P < 0.01). BrMYB34.1 (Bra13000) was associated with NAP (0.42), 4OH (0.46), and the accumulation of total glucosinolates (0.40) (P < 0.01). BrMAM-5 (Bra013011) was associated with 4OH (0.44) and GBC (0.47) (P < 0.01). BrMYB28.1 (Bra012961) and BrMAM-4 (Bra013009) showed no correlation with glucosinolate accumulation. These results suggest that BrMAM-3 plays an important role in controlling the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates. Our inference agrees with the fact that overexpression of the AtMAM1 gene in Brassica spp. increases total aliphatic glucosinolate content42.

Nucleotide polymorphisms of candidate genes situated within major QTLs

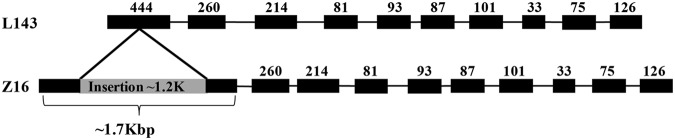

We found that an insertion in BrMAM-3 that was related to the observed variations in aliphatic glucosinolates. The BrMAM-3 gene that was predicted consists of 11 exons, encoding 504 amino acids. The deduced protein sequence of the BrMAM-3 gene showed 81.2% and 77.9% identity with AtMAM1 and AtMAM3, respectively. The BrMAM-3 gene showed 100% identity with the L143 and Z16 accessions, except for one transposon insertion in exon 1. Furthermore, ten single-nucleotide substitutions (SNPs) across introns and exons were detected. Among the SNPs, three synonymous and one non-synonymous mutations were located in exons; the other SNPs were detected within introns, but did not affect the characteristics of amino acids. However, the BrMAM-3 transcript containing the 1.2-kb transposon insertion fragment (Fig. 2) was predicted to be translated into a non-functional truncated protein of 101 amino acids that included a frame shift. We detected trace or no aliphatic glucosinolates in the Z16 accession, which harbors the BrMAM-3 allele with the transposon insertion.

Fig. 2. Gene structure of BrMAM-3 in accessions L143 and Z16.

Exons are shown in black blocks and numbers above the blocks indicate exon length. The gray block in exon one indicates the transposon insertion

No correlation with aliphatic glucosinolates was observed for the variations in BrMYB34.1, BrMYB28.1, BrMAM-4, and BrMAM-5. The gene sequences showed 100% identity between L143 and Z16 accessions, except for several SNPs across introns and exons. For example, there were two SNPs involved in BrMYB34.1, three in BrMYB28.1, and five in BrMAM-5 (Figure S1). These SNPs did not affect the characteristics of amino acids. Moreover, the BrMAM-4 and BrMAM-5 genes exhibited intact gene structures compared to AtMAM. The BrMAM-4 gene contains eight exons, and the BrMAM-5 gene has seven exons. These encode proteins with incomplete motifs, lacking two conserved motifs, respectively. The missing motifs belong to the PLN03228 (methylthioalkylmalate synthase) conserved domain, which may result in lower or inactive enzyme activity during methionine biosynthesis29. Therefore, the BrMYB34.1, BrMYB28.1, BrMAM-4, and BrMAM-5 genes were not considered key candidate genes that control the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa. BrMAM-1 and BrMAM-2, which are clustered as MF1, also had intact gene structures compared to AtMAM. BrMAM-1 lost one exon and BrMAM-2 encodes a protein that lacks two conserved motifs29. These two genes were not detected by QTL analysis, suggesting that although these have inherited the same MAM gene of A. thaliana, these did not inherit the key role in controlling aliphatic glucosinolates accumulation during rediploidization.

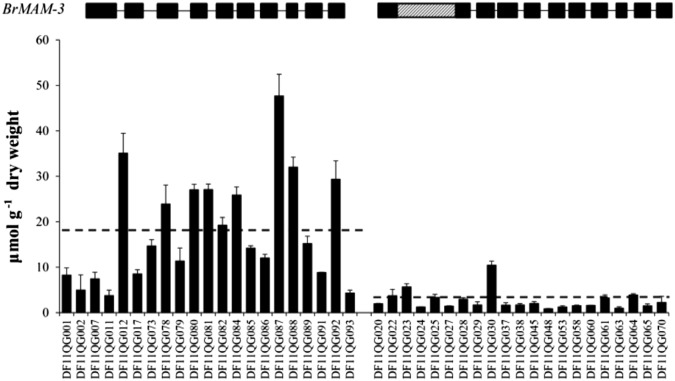

Relationship between total aliphatic glucosinolates and nucleotide polymorphisms in BrMAM-3

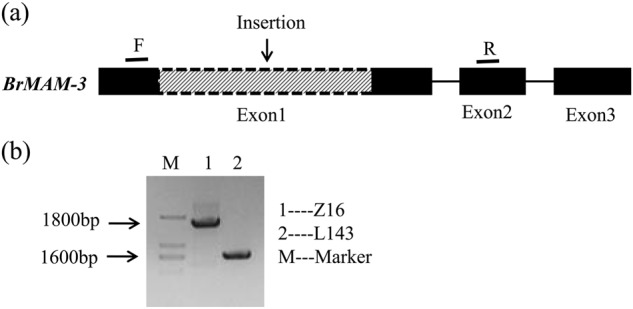

The insertion of BrMAM-3 was used to develop a PCR-based marker across exons 1 and 2 and was validated in Z16 and L143 accessions (Fig. 3). The marker was used to analyze the association between total aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation and the BrMAM-3 transposon-insertion alleles in a natural DH germplasm collection (Fig. 4). Correlation analysis showed that the transposon-insertion polymorphism is significantly associated with variations in the total aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation among the tested B. rapa accessions. Of the 42 screened DH lines, half of the accessions possessed the functional allele, whereas the others harbored transposon insertions (Fig. 4). The accessions with the functional alleles had a significantly higher amount of total aliphatic glucosinolates than those with insertion alleles. The average number of total aliphatic glucosinolates in DH lines with the functional BrMAM-3 allele was about sixfold greater than those with the mutated insertion allele.

Fig. 3. Schematic model of development of marker used to detect 1.2-kbp insertion mutation across exons 1 and 2 of BrMAM-3.

a Insertion identified in accession Z16. Amplified region used to detect the insertion mutation encompassed part of exon 1, intron 1, and part of exon 2. F forward primer, R reverse primer. b Amplified fragments of BrMAM-3 in the accessions L143 and Z16

Fig. 4. Amplified fragments of BrMAM-3 and total aliphatic glucosinolates variations among germplasm collection of B. rapa leaves.

Dashed lines indicate the average amount of total aliphatic glucosinolates

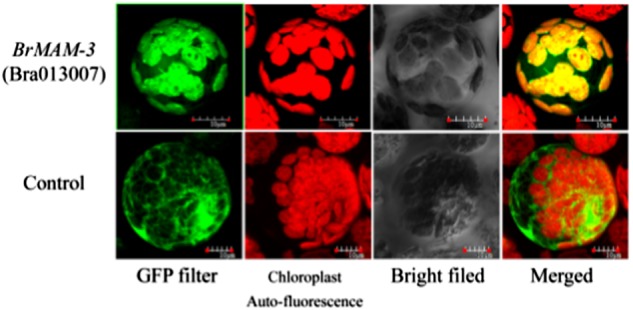

BrMAM-3 is localized to the chloroplast

We investigated the subcellular localization of BrMAM-3 to further analyze its characteristics. The ProCAMV35S:BrMAM-3:GFP vectors were constructed and detected by monitoring the transient expression of GFP in B. rapa mesophyll protoplast cells (Fig. 5). The transiently transformed cells showed strong green fluorescence signals in the chloroplasts, demonstrating that BrMAM-3 protein is a predominantly chloroplast-localized protein, which agrees with that reported of AtMAM3 in Arabidopsis (Col-0)13,16.

Fig. 5. Subcellular localization of the BrMAM-3 protein in Brassica rapa protoplast.

Images were taken in dark field for green fluorescence and chloroplast autofluorescence (in red color), whereas cellular morphology was assessed by imaging the cells in bright field. The bar indicates 10 μm

BrMAM-3 encodes a functional protein that controls the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates

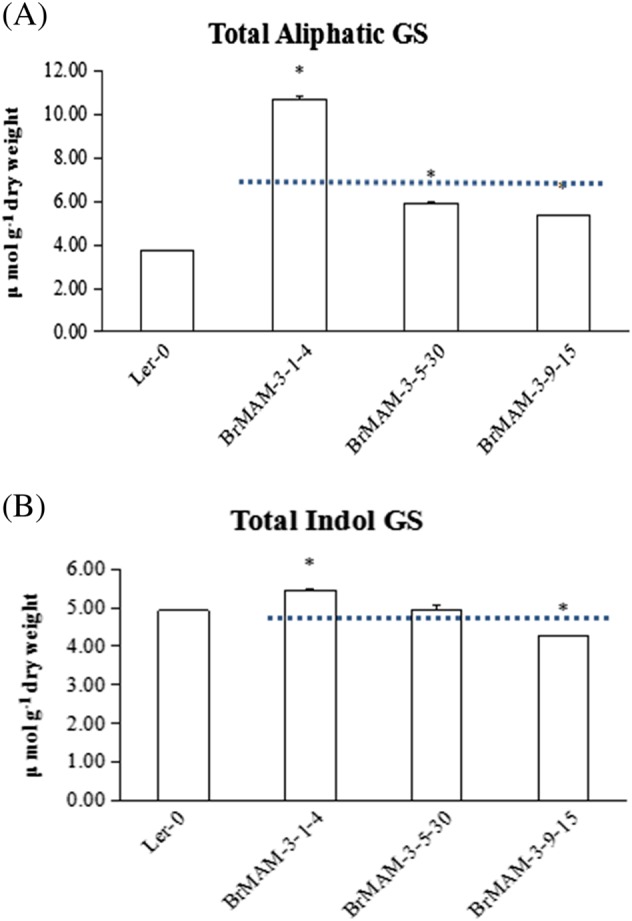

A complementation test was performed by creating transgenic plants overexpressing the BrMAM-3 gene in the natural Arabidopsis mutant Landsberg erecta (Ler-0), in which the 5′ portion of MAM1 is deleted12. Three independent homozygous lines of BrMAM-3 were analyzed for total as well as individual glucosinolate fractions in 8-week-old rosette leaves.

The functional complementation of the BrMAM-3 gene elevated the accumulation of total aliphatic glucosinolate 1.4- to 2.9-fold compared to Ler-0 (Fig. 6a). However, the average amount of total indol glucosinolates of the complement lines did not exceed that of Ler-0 (Fig. 6b). Thus, the results of mutant complementation analysis in A. thaliana suggest that the BrMAM-3 gene controls the levels of aliphatic glucosinolates.

Fig. 6. Functional complementation analysis of BrMAM-3 gene in the Arabidopsis natural mutant Ler-0.

The BrMAM-3 gene is overexpressed in Ler-0, and the glucosinolate content and profile (in µnmol g−1 dry weight) was determined in 8-week-old rosette leaves. The individual graphs show the accumulation of a total aliphatic glucosinolates; b total indol glucosinolate. Three independent mutant-complemented lines of BrMAM-3 gene were analyzed, and average foliar glucosinolates from 30 individual plants are represented along with their standard errors. Asterisks indicate significant differences in glucosinolate content compared with Ler-0 (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA analysis with Duncan post hoc test). Dashed lines indicate the average amount of total aliphatic/indol glucosinolates

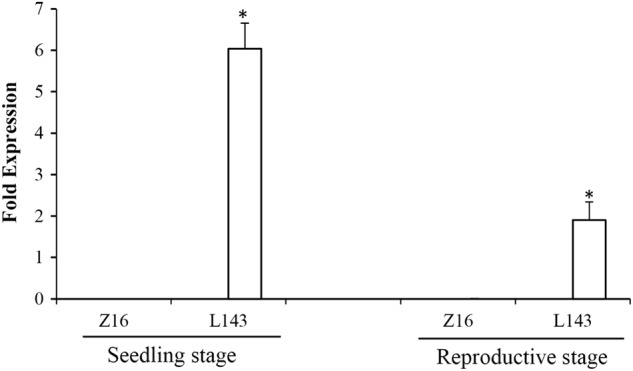

Expression patterns of BrMAM-3 are associated with the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa leaves

We measured BrMAM-3 transcript expression in the accessions L143 and Z16 at the seedling and reproductive stages by qRT-PCR. The transcript levels of BrMAM-3 were significantly higher in L143 than Z16 (Fig. 7). In Z16, undetectable or trace expression levels of BrMAM-3 were observed in both the seedling and reproductive stages. In contrast, BrMAM-3 was upregulated in glucosinolate-synthesizing tissues of L143 such as seedling leaves and mature leaves. The BrMAM-3 expression profile in L143 coincided with the pattern of AtMAM1 transcript accumulation, which showed maximum accumulation in expanding leaves followed by mature leaves.16

Fig. 7. Expression profile of BrMAM-3 gene at the seedling and reproductive stages in accessions Z16 and L143.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted, and the expression levels of BrMAM-3 in L143 siliques are indicated. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of three biological repeats. Asterisks indicate significant differences in the expression profile of the BrMAM-3 gene compared to the Z16 accession (P < 0.05, determined by one-way ANOVA)

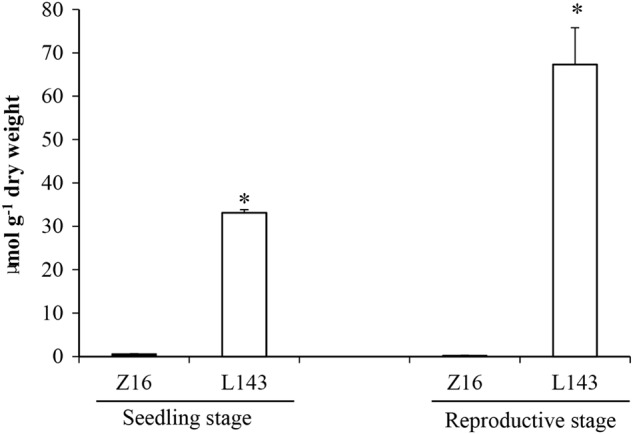

To test whether the transcription of BrMAM-3 gene contributes to the accumulation of total aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa, we analyzed the glucosinolate profiles of different developmental stages by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). There were pronounced differences in the total aliphatic glucosinolate concentrations between Z16 and L143 both at the seedling and reproductive stages (Fig. 8). At the seedling stage, Z16 had trace amounts of total aliphatic glucosinolates in the leaves, whereas the expanding leaves of L143 depicted high aliphatic glucosinolate levels. These observations coincided with the expression pattern of BrMAM-3. In the reproductive stage, the total aliphatic glucosinolate in the leaves of L143 were higher than that of Z16. The total aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation in L143 at the seedling and reproductive stages was apparently inconsistent with the BrMAM-3 expression patterns. Therefore, other BrMAM genes or the R2R3-BrMYB superfamily transcription factors may be involved in glucosinolate accumulation.

Fig. 8. Total aliphatic glucosinolates accumulation (in µmol g–1 dry weight) in Z16 and L143 at the seedling and reproductive stages.

Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of three biological repeats. Asterisks indicate significant differences in aliphatic glucosinolates content compared to the Z16 accession (P < 0.05, determined by one-way ANOVA)

Discussion

Aliphatic glucosinolates, secondary metabolites known to be involved in plant defense, make up the majority of the glucosinolate content in A. thaliana and Brassica spp. In A. thaliana, the amount of total aliphatic glucosinolates is regulated by three R2R3-MYB transcription factors (MYB28, MYB29, and MYB76), and their structural diversity arises from chain elongations of methionine and side-chain modifications. However, the molecular genetic mechanism controlling aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation in B. rapa is largely unknown. Our study implicates BrMAM-3 in controlling aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation. This research will pave the way for the genetic manipulation of total aliphatic glucosinolate levels in B. rapa.

Variations in BrMAM-3 are related to reduced aliphatic glucosinolate levels in B. rapa

Apart from the artificially generated genotypes and high-throughput technologies, the analysis of naturally occurring genetic variations provides insights into the control of important plant processes. Relationships between naturally occurring variants and aliphatic glucosinolates have been reported in A. thaliana43–45 and B. olerace46, but are limited in B. rapa and other Brassica species. A previous report has shown that silencing of the AtMAM gene family in B. napus canola and B. napus rapeseed reduces the content of aliphatic and total glucosinolates47.

We analyzed the association between the expression and structure of five-candidate genes and glucosinolate content and profiles to study the genes involved in the differential aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation among B. rapa accessions. Our results showed that the two MYB genes (BrMYB28.1 and BrMYB34.1) and two MAM genes (BrMAM-4 and BrMAM-5) showed no significant correlation with aliphatic glucosinolates, BrMAM-3 exhibited a significant positive correlation with aliphatic glucosinolates. Mutant complementation of A. thaliana showed that BrMAM-3 increases the amount of total aliphatic glucosinolates. However, detailed expression analysis using qRT-PCR assays revealed that BrMAM-3 has genotypic-specific expression partitioning in B. rapa. Moreover, a large insertion in exon 1 of BrMAM-3 among the accessions with a trace amount of total aliphatic glucosinolate indicates that the loss function of BrMAM-3 results in a reduction in total aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa. Meanwhile, the transposon insertion in the first exon of BrMAM-3 could lead to a different transcriptional regulation of BrMAM-3 between the L143 and Z16 accessions.

Functional divergence could occur in the MAM of the major QTL

Based on the results of phylogenetic and syntenic analyses of sequenced Brassicaceae species, we propose a lineage-specific evolution pattern for syntenic MAM loci48. Upon divergence of the Brassica genus, B. rapa retained various copies of MAM genes, which were generated from WGT, followed by biased gene loss.

The three tandem BrMAM genes in the major QTL locus, with the same gene order and orientation, are located in the conserved syntenic region of the LF. BrMAM-4 underwent a recent TD event to give rise to BrMAM-548. The present study showed that BrMAM-3 is responsible for the observed variations in aliphatic glucosinolates, indicating that BrMAM-3 retained the function of the MAMa gene. Sequence analysis showed that BrMAM-4 and BrMAM-5 have intact gene structures compared to AtMAM, which lacks the methylthioalkylmalate synthase-conserved domain. Further investigation demonstrated that BrMAM-4 is not associated with the accumulation of glucosinolates, indicating that BrMAM-4 may have lost MAM enzyme activity. BrMAM-5 is associated with 4OH and GBC but not aliphatic glucosinolates, suggesting that it acquired a new function (neofunctionalization) that is involved in indol glucosinoate biosynthesis.

BrMAM-1 and BrMAM-2 are located in the conserved syntenic region of the MF. BrMAM-1 underwent a recent TD event to give rise BrMAM-248. These two genes may have retained their catalytic activity for aliphatic glucosinoate accumulation, which requires validation in a future investigation.

BrMAM-3 is a candidate for engineering the high aliphatic glucosinolate trait in B. rapa

Glucosinolates have obtained the status of “model” secondary metabolites because their hydrolysis products exhibit different biological activities, e.g., as defense compounds and attractants. For humans, these compounds function as cancer-preventing agents, biopesticides, and flavor compounds. In the past decade, certain glucosinolates have been identified as potent cancer-preventing agents. Sulforaphane, the isothiocyanate derivative of glucoraphanin found in broccoli, has been the focus of many of these studies. These results aim to increase the sulforaphane content in broccoli and promote the health benefits of this vegetable. However, many Brassica species such as B. rapa, B. napus, and B. juncea harbor trace amounts of glucoraphanin, which is the precursor of sulforaphane49. RNA interference (RNAi) has been demonstrated to be an efficient method of silencing GSL-ELONG47 and GSL-ALK gene families50 to manipulate the beneficial glucosinolate profiles in B. napus. However, efforts in developing beneficial glucosinolate profiles in B. rapa are limited.

In B. rapa, the aliphatic glucosinolates are the predominant glucosinolates but vary among varieties in terms of content and glucosinolate profiles10,51. Our previous study identified three BrAOP2 genes encoding the functional AOP2 that is involved in side-chain modifications of aliphatic glucosinolates29. Thus, it is possible to block BrAOP2 genes to develop beneficial glucosinolates. In our current study, the accessions with functional BrMAM-3 alleles had a significantly higher amount of total aliphatic glucosinolates than those with insertion alleles, demonstrating that the BrMAM-3 gene plays an important role in controlling the accumulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa. Thus, BrMAM-3 could be utilized to improve the amount of total aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa accessions with low aliphatic glucosinolate content. Silencing of BrAOP2 genes and overexpression of the functional BrMAM-3 gene can be coupled to enrich the amount of beneficial glucosinolates in B. rapa.

Our findings provide functional evidence of expression partitioning of BrMAM-3 gene in controlling aliphatic glucosinolate content. Our results suggest that the naturally occurring transposon insertion in exon 1 of BrMAM-3 contributes largely to the observed variations in accumulation of total aliphatic glucosinolates in B. rapa. The information obtained in the current study may aid in manipulating the aliphatic glucosinolate content in Brassica crops using conventional breeding and/or transgenic approaches.

Materials and methods

Plant material

To characterize the association of glucosinolate profiles of B. rapa and the expression pattern of five-candidate genes, we performed transcriptome profile sequencing in 52 B. rapa accessions according to Cheng et al.52 (Supplementary Table S3). These accessions belong to 11 cultivar groups (Supplementary Table S5).

Two DH accessions Z16 and L143 were germinated and grown in a greenhouse at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China) in the spring of 2011. Z16 is a Chinese cabbage accession with low glucosinolate content, whereas L143 is a yellow sarson accession with a high level of glucosinolates content. Leaf samples were collected from these plants for BrMAM-3 gene expression and glucosinolates profiling. Three biological replicates of each sample were prepared under normal growth conditions (10 weeks after sowing). Different tissues were collected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80 °C until further use.

Forty-two B. rapa accessions (Supplementary Table S5) were used to screen for BrMAM-3 sequence variations. The accessions were grown in a greenhouse in Beijing in the fall of 2011 to investigate aliphatic glucosinolate profiles. The temperature in the greenhouse was between 15 and 25 °C night/day.

A. thaliana ecotype Landsberg erecta (Ler) was used for functional complementation in vivo. Seeds of Ler-0 were plated on soil and cold-treated at 4 °C for 3 days in the dark. After stratification, seeds were transferred into a temperature-controlled growth chamber under short-day conditions (8 h light, 16 h dark) at 21–24 °C and 40% humidity.

For plants grown on Petri dishes, the seeds were surface sterilized with 75% (v/v) ethanol for 7 min and then washed thrice with sterile water. Seeds were sown on Murashige and Skoog (MS)-agar medium (one-half-strength MS salt, pH 5.8) and cold-treated at 4 °C for 2 days in the dark, then placed in a growth chamber (16 h of light at 22 °C and 8 h of darkness at 18 °C). Transgenic plants were selected by germination on half-strength MS medium containing kanamycin/hygromycin antibiotics and were subsequently treated as wild-type plants.

Development of BC2DH populations, QTL mapping, and isolation and sequencing of candidate genes

The recurrent parents, L143 and L144 (with a high levels of glucosinolates), were used as the female and the donor as the male parent (Z16 accession) to generate the F1 generation. A single F1 plant (maternal) was backcrossed to the respective cultivars (paternal) to produce BC1F1 plants. Then, each BC1F1 plant was backcrossed a second time with the two cultivars. Two BC2DH populations designated as RC_BC2DH (derived from the cross L143) and YS_BC2DH (derived from the cross L144) were developed by another culture. A total of 250 BC2DH lines were obtained from the two BC2DH populations.

For the analysis of phenotypic measurement of aliphatic glucosinolates, 120 individual lines of each BC2DH populations were used and grown in the greenhouse in two different seasons. Linkage maps were constructed using JoinMap 4 and QTL analysis was performed with MapQTL4 (https://www.kyazma.nl/). QTL mapping was initially performed on transformed data with interval mapping (IM) followed by composite interval mapping, referred to as MQM mapping in MapQTL4. The significant cofactors for each MQM model were determined through an iterative automatic cofactor selection. The genome-wide logarithm of odds (LOD) significance threshold was obtained from permutation tests with 1000 replicates as implemented in MapQTL4.

To detect possible variations in the candidate genes involved on the major QTL locus in L143 and Z16 accessions, the candidate gene sequences were amplified with specific primers (Supplementary Table S6) from genomic DNA, and sequenced using an ABI3730XL analyzer and analyzed using ClustalX.

Generation of transgenic plants

The coding sequences of BrMAM-3 gene were isolated and amplified using L143 cDNA as template with the gene-specific primers, including restriction sites (BrMAM-3, forward primer with KpnI restriction site: 5′-GGGGTACCATGGCTTCGTCACTTCTG-3′, reverse primer with XbaI restriction site: 5′-GCTCTAGATTATACCACAGAAGAAATC-3′), and ligated to a pEASY-T1 vector. Following sequence analysis, the pEASY-T1:BrMAM-3 constructs were digested with KpnI/XbaI and inserted into the pCambia 1300 vector driven by a CaMV35S promoter. The resulting construct was verified by DNA sequencing and subsequently transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101). The binary vector pCambia 1300 containing a hygromycin resistance gene was utilized in the selection of transformed Arabidopsis lines. The floral infiltration method53,54 was used to transform natural mutant Ler-0 plants. Transgenic plants were selected by germination on half-strength MS medium containing 30 μg mL−1 hygromycin antibiotics and were subsequently treated as wild-type plants. The T2 generation derived from the selected plants was used to identify homozygous transformed lines. The T3 generation homozygous plants were subsequently employed in HPLC analysis.

Construction of the ProCAMV35S:BrMAM-3:GFP fusion plasmid and transformation of B. rapa mesophyll protoplast cells

To identify the subcellular localization of the BrMAM-3 gene, ProCAMV35S:BrMAM-3:GFP (green fluorescent protein) constructs were generated. The BrMAM-3 coding sequences without stop codon were isolated and amplified from cDNA with the gene-specific primers including restriction sites (forward primer with an XbaI restriction site: 5′-TCTAGAATGGCTTCGTCACTTCTGAC-3′, reverse primer with KpnI restriction site: 5′-TTGGTACC TACCACAGAAGAAATC-3′). The PCR-amplified BrMAM-3 was inserted into the pSPYCE-35S/pUC-SPYCE vector by XbaI/KpnI digestion and ligation. The resulting constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. The subcellular locations of the BrMAM-3 genes were detected by monitoring the transient expression of GFP in B. rapa mesophyll protoplast cells54 on an OLYMPUS FV1200 Laser Confocal System. GFP fluorescence was imaged at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm, and the emission signal was detected between 495 and 530 nm for GFP and between 643 and 730 nm for chlorophyll autofluorescence.

Glucosinolate extraction and HPLC analysis

The extraction and quantification of glucosinolates were performed by HPLC as previously described (Hehongju protocols, 2002). Lyophilized samples (0.2 g) were weighed in 15-mL plastic tubes and immersed in boiling methyl alcohol (5 mL) containing 100 µL benzyl glucosinolate as the internal standard. After 20 min of gentle shaking, samples were cooled at 4 °C and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant (extract) was cleaned twice with 70% methyl alcohol. The extracts were loaded onto DEAE Sephadex A25 columns and desulfated overnight using purified sulfatase before HPLC. The column was then washed thrice with 0.5 mL deionized water, and the eluent that was filtered using a 0.45 μm membrane was used for HPLC analysis. Specific glucosinolates were identified by comparing retention times and UV absorption spectra with purified standards. Concentrations of individual glucosinolates were calculated as nmol mg−1 DW relative to the area of the internal standard peak using the respective response factors reported earlier55.

Reverse transcriptase-mediated first-strand synthesis and real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from different organs of accessions L143 and Z16 using a total RNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sangon, http://www.sangon.com) and then treated with DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) to eliminate any DNA contamination. RNA purity was determined spectrophotometrically, and quality was determined by examining rRNA bands on 1% agarose gels. cDNAs were synthesized from ~2 μg of total RNA using TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Transgen, www.transgen.com.cn) with oligo(dT) as primer in a 20-μL reaction.

The specificity of the primers of BrMAM-3 and BrGAPDH was verified by DNA sequencing after their PCR products were cloned into pEASY-T1 vectors. The efficiency of gene-specific BrMAM-3 and GAPDH primer pairs was initially ascertained using a fourfold serial dilution of the L143 cDNA. A linear correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.95 and above was observed over a 64-fold dilution range, which reflected the high efficiency of each primer pair. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed in a total volume of 15 µL, which included 2 µL of diluted cDNA, 0.5 µL of each primer (10 pM), and 7.5 µL of 2× SYBR Green Master Mixes (Thermo Fisher, USA) on an Eppendorf real-Time PCR system (Eppendorf, Germany), according to the kit manual. The RT-qPCR program was conducted at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 60 s. The expression level of BrGAPDH was used as an internal control, and the expression of other genes was computed using the 2–ΔΔCT method56. The primers used in this work are listed in Supplementary Table S7.

Insertion marker analysis

The forward primer F (5′-CGTCCGTACAACAAGTCATCC-3′) in exon 1 and the reverse primer R (5′-AACTTAACACTACTCGCGGCC-3′) in exon 2 were designed to develop an insertion marker for BrMAM-3. PCR was performed under the following conditions: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1.5 min), and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel to determine the genotype of the insertion marker.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s post hoc test using the SPSS software. A P value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The National Key Research and Development Program of China (equally by 2016YFD0100307 and 2016YFD0100506), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31630068) and Application Basic Research Program of Qingdao [14-2-4-112-jch] supported this study. The work was also funded by the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. This research work was carried out in the Key Laboratory of Biology and Genetic Improvement of Horticultural Crops, Ministry of Agriculture, China.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jifang Zhang, Hui Wang

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41438-018-0074-6).

References

- 1.Rask L, et al. Myrosinase: gene family evolution and herbivore defense in Brassicaceae. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000;42:93–113. doi: 10.1023/A:1006380021658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fahey JW, et al. Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo[a]pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7610–7615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112203099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahey JW ZY, Talalay P. Broccoli sprouts: an exceptionally rich source of inducers of enzymes that protect against chemical carcinogens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10367–10372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamet-Payrastre L, et al. Phytochemicals from cruciferous plants protect against cancer by modulating carcinogen metabolism. J. Nutr. 2001;131:3027–3033. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3027S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traka M, Mithen R. Glucosinolates, isothiocyanates and human health. Phytochem. Rev. 2009;8:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s11101-008-9103-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Kensler TW, Cho CG, Posner GH, Talalay P. Anticarcinogenic activities of sulforaphane and structurally related synthetic norbornyl isothiocyanates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:3147–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faulkner K, Mithen R, Williamson G. Selective increase of the potential anticarcinogen 4-methylsulphinylbutyl glucosinolate in broccoli. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:605–609. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clay NK, Adio AM, Denoux C, Jander G, Ausubel FM. Glucosinolate metabolites required for an Arabidopsis innate immune response. Science. 2009;323:95–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1164627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroymann J, Donnerhacke S, Schnabelrauch D, Mitchell-Olds T. Evolutionary dynamics of an Arabidopsis insect resistance quantitative trait locus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14587–14592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734046100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padilla G, Cartea ME, Velasco P, de Haro A, Ordas A. Variation of glucosinolates in vegetable crops of Brassica rapa. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schonhof I, Krumbein A, Bruckner B. Genotypic effects on glucosinolates and sensory properties of broccoli and cauliflower. Nahrung. 2004;48:25–33. doi: 10.1002/food.200300329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benderoth M, et al. Positive selection driving diversification in plant secondary metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9118–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601738103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonderby IE, Geu-Flores F, Halkier BA. Biosynthesis of glucosinolates--gene discovery and beyond. Trends Plant. Sci. 2010;15:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kliebenstein DJ, Lambrix VM, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T. Gene duplication in the diversification of secondary metabolism: Tandem 2-oxoglutarate–dependent dioxygenases control glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:681–693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Textor S, et al. Biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana: recombinant expression and characterization of methylthioalkylmalate synthase, the condensing enzyme of the chain-elongation cycle. Planta. 2004;218:1026–1035. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Textor S, de Kraker JW, Hause B, Gershenzon J, Tokuhisa JG. MAM3 catalyzes the formation of all aliphatic glucosinolate chain lengths in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:60–71. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Kraker JW, Gershenzon J. From amino acid to glucosinolate biosynthesis: protein sequence changes in the evolution of methylthioalkylmalate synthase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:38–53. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beekwilder J, et al. The impact of the absence of aliphatic glucosinolates on insect herbivory in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gigolashvili T, Engqvist M, Yatusevich R, Muller C, Flugge UI. HAG2/MYB76 and HAG3/MYB29 exert a specific and coordinated control on the regulation of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2008;177:627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gigolashvili T, Yatusevich R, Berger B, Muller C, Flugge UI. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor HAG1/MYB28 is a regulator of methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;51:247–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirai MY, et al. Omics-based identification of Arabidopsis Myb transcription factors regulating aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6478–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonderby IE, et al. A systems biology approach identifies a R2R3 MYB gene subfamily with distinct and overlapping functions in regulation of aliphatic glucosinolates. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gigolashvili T, et al. The transcription factor HIG1/MYB51 regulates indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;50:886–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schweizer F, et al. Arabidopsis basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis, insect performance, and feeding behavior. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3117–3132. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takuno S, et al. Effects of recombination on hitchhiking diversity in the Brassica self-incompatibility locus complex. Genetics. 2007;177:949–958. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lou P, et al. Quantitative trait loci for glucosinolate accumulation in Brassica rapa leaves. New Phytol. 2008;179:1017–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, et al. Glucosinolate biosynthetic genes in Brassica rapa. Gene. 2011;487:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YB, et al. MYB transcription factors regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis in different organs of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) Molecules. 2013;18:8682–8695. doi: 10.3390/molecules18078682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, et al. Three genes encoding AOP2, a protein involved in aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis, are differentially expressed in Brassica rapa. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:6205–6218. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mithen R, Clarke J, Lister C, Dean C. Genetics of aliphatic glucosinolates. III. Side-chain structure of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Heredity. 1995;74:210–215. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1995.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Vreugdenhil D. Naturally occurring genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kliebenstein DJ, Pedersen D, Barker B, Mitchell-Olds T. Comparative analysis of quantitative trait loci controlling glucosinolates, myrosinase and insect resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2002;161:325–332. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfalz M, Vogel H, Mitchell-Olds T, Kroymann J. Mapping of QTL for resistance against the crucifer specialist herbivore Pieris brassicae in a new Arabidopsis inbred line population, Da(1)-12 x Ei-2. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giamoustaris A, Mithen R. Genetics of aliphatic glucosinolates. IV. Side-chain modification in Brassica oleracea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1996;93:1006–1010. doi: 10.1007/BF00224105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howell PM, Sharpe AG, Lydiate DJ. Homoeologous loci control the accumulation of seed glucosinolates in oilseed rape (Brassica napus) Genome. 2003;46:454–460. doi: 10.1139/g03-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uzunova M, Ecke W, Weissleder K, Robbelen G. Mapping the genome of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). I. Construction of an RFLP linkage map and localization of QTLs for seed glucosinolate content. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1995;90:194–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00222202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Meng J. Detection of loci controlling seed glucosinolate content and their association with Sclerotinia resistance in Brassica napus. Plant Breed. 2003;122:19–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2003.00784.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood T, Ekuere U, Yeh F, Good AG, Stringam GR. Molecular mapping of seed aliphatic glucosinolates in Brassica juncea. Genome. 2003;46:753–760. doi: 10.1139/g03-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramchiary N, et al. QTL analysis reveals context-dependent loci for seed glucosinolate trait in the oilseed Brassica juncea: importance of recurrent selection backcross scheme for the identification of ‘true’ QTL. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007;116:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0648-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hittinger CT, Carroll SB. Gene duplication and the adaptive evolution of a classic genetic switch. Nature. 2007;449:677–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franzke A, Lysak MA, Al-Shehbaz IA, Koch MA, Mummenhoff K. Cabbage family affairs: the evolutionary history of Brassicaceae. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zang YX, Kim JH, Park YD, Kim DH, Hong SB. Metabolic engineering of aliphatic glucosinolates in Chinese cabbage plants expressing Arabidopsis MAM1, CYP79F1, and CYP83A1. BMB Rep. 2008;41:472–478. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2008.41.6.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kliebenstein DJ, et al. Genetic control of natural variation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:811–825. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mithen R, Raybould AF, Giamoustaris A. Divergent selection for secondary metabolites between wild populations of Brassica oleracea and its implications for plant-herbivore interactions. Heredity. 1995;5:472–484. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1995.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neal CS, Fredericks DP, Griffiths CA, Neale AD. The characterisation of AOP2: a gene associated with the biosynthesis of aliphatic alkenyl glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li G QuirosCF. In planta side-chain glucosinolate modification in Arabidopsis by introduction of dioxygenase Brassica homolog BoGSL-ALK. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003;106:1116–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Z, et al. MAM gene silencing leads to the induction of C3 and reduction of C4 and C5 side-chain aliphatic glucosinolates in Brassica napus. Mol. Breed. 2010;27:467–478. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9444-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, et al. Lineage-specific evolution of methylthioalkylmalate synthases (MAMs) involved in glucosinolates biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:18. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosa EAS, Heaney RK, Fenwick GR, Portas CAM. Glucosinolates in crop plants. Hortic. Rev. 1997;19:99–215. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z, et al. Reducing progoitrin and enriching glucoraphanin in Brassica napus seeds through silencing of the GSL-ALK gene family. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;79:179–189. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JK, et al. Variation of glucosinolates in vegetable crops of Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis. Food Chem. 2010;119:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.08.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng F, et al. Subgenome parallel selection is associated with morphotype diversification and convergent crop domestication in Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1218–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng.3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown PD, Tokuhisa JG, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J. Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:471–481. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.