Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the magnitude of response to secukinumab treatment over 3 years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) grouped by baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in a pooled study of two pivotal phase III studies: MEASURE 1 (NCT01358175) and MEASURE 2 (NCT01649375).

Methods

This post hoc analysis pooled data from all patients with available baseline CRP in the two studies who received subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg (approved dose; N=197) or placebo (N=195). Assessed efficacy endpoints included Assessments of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS)20/40, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), BASDAI50, AS Disease Activity Score inactive disease and ASAS partial remission among patients grouped by baseline CRP based on central laboratory cut-off <5 mg/L (normal) or ≥5 mg/L (elevated) and a cut-off <10 mg/L or ≥10 mg/L.

Results

At baseline, 36.5% (143/392) patients had normal and 63.5% (249/392) had elevated CRP. At week 16, ASAS20/40 response rates were higher for secukinumab versus placebo in normal (56.9%/34.7% vs 28.2%/7.0%; p<0.01/p<0.001) and in elevated (63.2%/42.4% vs 29.0%/15.3%; both p<0.0001) CRP groups. Improvement was reported for all outcomes (p<0.05) in both groups, except for ASAS partial remission in the normal CRP group, where a numerical difference 12.5% vs 2.8%, p=0.07) was observed. Similar trends of improvement were observed in the <10 and ≥10 mg/L groups across all efficacy outcomes at week 16. Treatment responses to secukinumab in all CRP groups further improved over 156 weeks.

Conclusion

Secukinumab 150 mg demonstrated rapid and sustained efficacy in patients with AS irrespective of baseline CRP, with greater magnitude of response in patients with more elevated CRP.

Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis, DMARDs (biologic), inflammation, cytokine, spondyloarthritis

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Elevated baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) has been described to be a predictor of treatment response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

What does this study add?

This post hoc analysis showed that secukinumab 150 mg provides rapid and sustained efficacy in patients with AS irrespective of baseline CRP levels, with greater magnitude of response in patients with elevated CRP.

The results herein show that patients with normal baseline CRP levels also have a strong likelihood of experiencing a positive treatment response with interleukin-17A inhibition.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

There was an unmet need for effective treatment strategies in patients with AS with normal baseline CRP levels, and herein, we show that secukinumab works in patients with both normal and elevated CRP levels, thus widening the spectrum of patients who could be treated effectively.

Introduction

Constituting a major part of the spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease characterised by irreversible structural damage of the sacroiliac joints and the spine, which is frequently associated with pain, stiffness, disability and reduced quality of life.1 2 Elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients with AS is an important factor for the early detection of the disease.3 CRP is an item in the Assessments of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification criteria, and is one of the key components of the AS Disease Activity Score (ASDAS). Elevated baseline CRP has also been described as a predictor of treatment response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in patients with active AS.4–8

According to the ASAS-EULAR recommendations,9 the first treatment of choice in patients with axSpA is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), while conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs), according to the new nomenclature proposed,10 are largely not efficacious.11 This is in contrast to biologic DMARDs, such as TNFi and interleukin-17A (IL-17A) inhibitor, which are the only biologics that are currently recommended and approved for the management of AS.9 The baseline factors associated with TNFi treatment responses in patients with AS have been described by several authors.5–7 12 Among these, elevated baseline CRP levels is an important factor that predicts ASAS20 and ASAS40 responses, ASAS partial remission and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index 50 (BASDAI50) outcomes in patients with active AS treated with TNFi.6–8 12 13 Elevated CRP levels have also been shown to predict structural changes in patients with AS who treated with TNFi.13 However, the relationship between baseline CRP levels and the treatment response to IL-17A inhibition has not been assessed to date in patients with active AS. In addition, effective treatment strategies for patients with AS with normal baseline CRP levels are needed, as studies show response rates to TNFi are lower in patients with AS with normal CRP levels compared with those with elevated CRP levels.5 6 12–14

Secukinumab, a fully human monoclonal IgG1κ antibody that selectively neutralises IL-17A, significantly improved the signs and symptoms of active AS in the pivotal phase III MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 studies, with responses sustained over 3 years.15–18 Herein, we present a post hoc analysis that assessed the response to secukinumab treatment in patients with active AS, across normal and elevated baseline CRP levels in data pooled from the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 studies over 3 years.

Methods

Study design and patients

The MEASURE 1 (NCT01358175) and MEASURE 2 (NCT01649375) study designs, eligibility criteria, methodology and statistical analysis strategies have been described previously.15 Briefly, patients aged ≥18 years with AS, fulfilling the modified New York criteria,19 with a score ≥4 (0–10 on the BASDAI,20 and spinal pain score ≥40 mm on (0–100 mm) the visual analogue scale, despite treatment with maximum tolerated doses of NSAIDs, were included in these studies. Patients treated with DMARDs and TNFi agents (other than sulfasalazine and methotrexate) were included with washout periods required before initiation of the study treatment. Patients treated with no more than one TNFi agent with an inadequate response to an approved dose for ≥3 months or had unacceptable side effects with at least one dose were allowed to participate. Patients were allowed with the following concomitant medications at a stable dose: sulfasalazine (≤3 g per day), methotrexate (≤25 mg per week), prednisone or equivalent (≤10 mg per day) and NSAIDs. Key exclusion criteria were patients with total spinal ankylosis, evidence of infection or cancer on chest radiography, active systemic infection within 2 weeks prior randomisation and previous treatment with cell-depleting therapies or biological agents other than TNFi agents. A flowchart of key inclusion and exclusion criteria of MEASURE 1 and 2 studies has been presented in online supplementary figure S1.

rmdopen-2018-000749supp001.docx (201.6KB, docx)

In MEASURE 1, patients received intravenous secukinumab 10 mg/kg at baseline, weeks 2 and 4, followed by subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg or 75 mg every 4 weeks starting at week 8. Placebo was given on the same intravenous to subcutaneous dosing schedule. Based on the clinical response, placebo-treated patients were re-randomised to receive subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg or 75 mg at week 16 (ASAS20 non-responders) or week 24 (ASAS20 responders). In MEASURE 2, patients received subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg, 75 mg or placebo at baseline, weeks 1, 2 and 3, followed by the same dose every 4 weeks starting at week 4. All placebo-treated patients were re-randomised to subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg or 75 mg at week 16.

This post hoc analysis pooled data from all patients in the two studies (MEASURE 1 and 2) with available baseline CRP levels (patients with non-missing baseline CRP) who received subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg (approved dose) or placebo. It has been reported that a CRP level above 5‒8 mg/L is the generally accepted cut-off for an abnormally high CRP, reflective of inflammation in rheumatological disorders.13 14 21 22 A high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) assay was performed in the MEASURE studies.23 24 The lower detection limit of CRP was 0.15 mg/L (represents the lowest measurable CRP concentration that can be distinguished from zero). Patients in this post hoc analysis were grouped by baseline CRP level as defined by the central laboratory (normal (<5 mg/L) or elevated (≥5 mg/L)) and by another clinically relevant cut-off: CRP levels <10 mg/L or ≥10 mg/L. Patients in the elevated (≥5 mg/L CRP) group were further subdivided into the following ranges: ≥5 to <10 mg/L, ≥10 to <15 mg/L and ≥15 mg/L (online supplementary data). Furthermore, to assess the proportion of patients who achieved early reduction in inflammation, patients were grouped based on whether or not they had a 50% decrease in CRP levels from baseline by week 4.

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.25

Outcome measures

Descriptions of the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints in the overall population in both studies have been published previously.15 Efficacy assessment in this analysis of pooled patients data through week 156 included ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS partial remission, mean change from baseline in total BASDAI score, BASDAI50 (an improvement of at least 50% of the initial total BASDAI score) and ASDAS inactive disease (ASDAS <1.3).7 26–28 All efficacy outcomes were assessed in patients grouped by (1) normal and elevated baseline CRP levels (normal (<5 mg/L) or elevated (≥5 mg/L)), (2) baseline CRP levels of <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L, (3) patients within subgroups by elevated CRP ranges and (4) patients with or without a 50% CRP decrease by week 4.

Statistical analysis

The results are reported for patients originally randomised to subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg (approved dose) or placebo. Statistical analyses used non-responder imputation through week 16, multiple imputation (MI) from week 20 to 156 for binary variables and mixed-effect model repeated measure (MMRM) for all time points through week 156 for continuous variables. The statistical comparisons for binary variables (n, percentages, odds ratios, 95% CIs and p values) were performed using a logistic regression model with study, treatment and TNFi status as factors, and baseline score if appropriate (only BASDAI50 and ASDAS inactive disease had their baseline value) and weight as covariates. The continuous variables (least square mean±SE [LSM±SE], 95% CI and p values) used study, treatment, analysis visit, TNFi status as factors and weight and baseline values as continuous covariates. Treatment by analysis visit and baseline value by analysis visit were included as interaction terms in the model, for which an unstructured covariance structure was assumed.

Results

A total of 392 patients with available baseline CRP values were pooled in this post hoc analysis of the two studies (MEASURE 1 and 2) from the secukinumab 150 mg (N=197) and placebo (N=195) groups. Of these, 36.5% (143/392) of patients had normal baseline CRP (<5 mg/L) and 63.5% (249/392) of patients had elevated baseline CRP (≥5 mg/L). The proportion of patients with normal and elevated CRP was similar in the secukinumab 150 mg and placebo groups.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients in the normal (<5 mg/L) and elevated (≥5 mg/L) CRP groups were balanced across the groups in this analysis, except for the proportion of TNFi-naïve, human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27-positive patients and hsCRP level. The mean age in the normal and elevated CRP groups was 43.8 and 41 years, respectively, and the mean time since AS diagnosis was 7.0 and 7.2 years. Baseline BASDAI was comparable across these groups with different levels of baseline inflammation (mean BASDAI score was 6.7 and 6.4 in the normal and elevated CRP groups, respectively). Mean patients global assessment of disease activity was 67.4 and 66.0, the proportion of HLA-B27-positive patients was 67.8% and 77.9% and the proportion of TNFi-naïve patients was 63.6% and 71.5% in the normal and elevated CRP groups, respectively. As expected, the median hsCRP (mg/L) values were lower in the normal CRP (2.1 (0.2‒4.9)) group compared with the elevated CRP (16.1 (5.0‒237.0)) group. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in the secukinumab 150 mg and placebo groups by normal (<5 mg/L) and elevated (≥5 mg/L) CRP are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Normal baseline CRP (<5 mg/L) |

Elevated baseline CRP (≥5 mg/L) |

|||

| Pooled secukinumab 150 mg (N=72) |

Pooled placebo (N=71) |

Pooled secukinumab 150 mg (N=125) |

Pooled placebo (N=124) |

|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.3 (10.5) | 45.3 (13.2) | 39.9 (12.7) | 42.2 (12.3) |

| Male, n (%) | 39 (54.2) | 47 (66.2) | 91 (72.8) | 93 (75.0) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 74.5 (14.6) | 76.4 (13.8) | 79.2 (18.4) | 79.0 (15.3) |

| Caucasian, n (%)* | 50 (69.4) | 51 (71.8) | 88 (70.4) | 100 (80.6) |

| Time since AS diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 5.9 (7.2) | 8.1 (9.9) | 7.2 (7.5) | 7.3 (8.3) |

| Positive for HLA-B27, n (%) | 44 (61.1) | 53 (74.6) | 99 (79.2) | 95 (76.6) |

| TNFi-naïve, n (%) | 52 (72.2) | 39 (54.9) | 84 (67.2) | 94 (75.8) |

| Concomitant methotrexate use, n (%) | 9 (12.5) | 7 (9.9) | 16 (12.8) | 17 (13.7) |

| hsCRP (mg/L), median (minimum‒maximum) | 2.1 (0.2‒4.9) | 1.9 (0.2‒4.9) | 16.8 (5.0‒237.0) | 14.9 (5.0‒146.8) |

| Total BASDAI score, mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.4) | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.6) | 6.6 (1.4) |

| PtGA of disease activity (0‒100 mm), mean (SD)† | 68.0 (17.4) | 66.9 (19.3) | 63.7 (19.1) | 68.4 (16.7) |

*Race was self-assessed.

†Disease activity was scored on a visual-analog scale from 0 (no disease activity) to 100 mm (the most severe disease activity).

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; N, number of patients in this pooled study; PtGA, patients global assessment; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; hsCRP, high sensitivity CRP.

Efficacy

Normal and elevated CRP

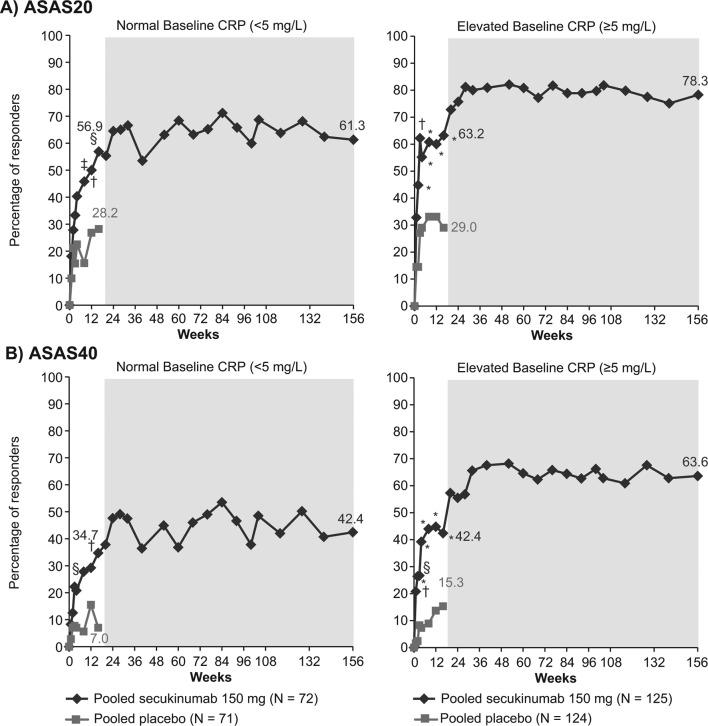

The ASAS20 response rate at week 16 was 56.9% with secukinumab 150 mg compared with 28.2% with placebo (p<0.01) in the normal CRP group, and 63.2% vs 29.0% (p<0.0001) in the elevated CRP group (figure 1A). The ASAS40 response rate was 34.7% with secukinumab 150 mg vs 7.0% with placebo (p<0.001) at week 16 in the normal CRP group and 42.4% vs 15.3% (p<0.0001) in the elevated CRP group (figure 1B). These responses were sustained or further improved with secukinumab treatment in both the normal and elevated CRP groups through week 156 (figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Improvement in (A) ASAS20 and (B) ASAS40 response rates in patients with normal or elevated CRP at baseline through week 156. *p<0.0001; †p<0.001; §p<0.01; ‡p<0.05 vs placebo; missing values were imputed as non-response through week 16. MI presented from week 20 to 156 (shaded area) included n=56 and 103 in the normal baseline CRP and elevated baseline CRP groups, respectively. Data for secukinumab 150 mg and placebo at week 16, and for secukinumab 150 mg at week 156 are depicted. ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society criteria; CRP, C-reactive protein; MI, multiple imputation; N, number of patients with available baseline CRP (normal or elevated) included in this pooled study through week 16; n, number of patients in this pooled study from week 20 to 156.

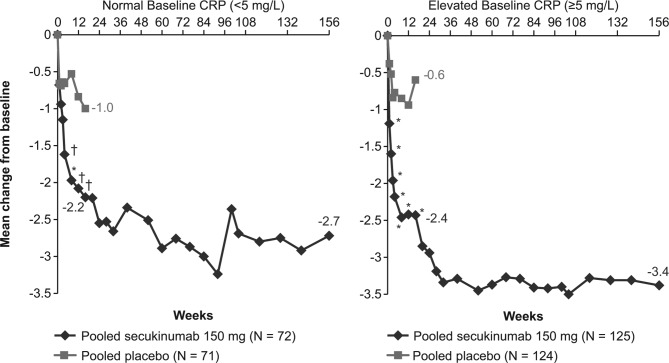

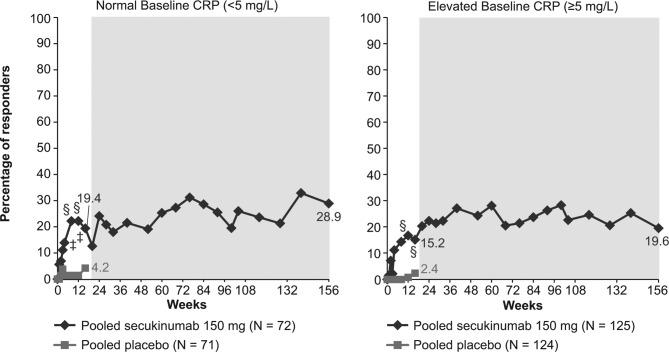

The LSM change from baseline in the BASDAI score at week 16 in the normal and elevated CRP groups was −2.2 and −2.4 with secukinumab 150 mg vs −1.0 and −0.6 with placebo (p<0.001 and p<0.0001), respectively (figure 2). A higher proportion of patients in the secukinumab 150 mg (19.4%) group achieved ASDAS inactive disease than those in the placebo (4.2%; p<0.05) group at week 16 in normal and 15.2% vs 2.4% (p<0.01), respectively, in elevated CRP groups (figure 3). These improvements in BASDAI score and ASDAS inactive disease response rates were sustained or further improved over 156 weeks of treatment with secukinumab 150 mg in both the normal and elevated CRP groups (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Improvement in BASDAI score in patients with normal or elevated CRP at baseline through week 156. *p<0.0001; †p<0.001; vs placebo; MMRM data shown through week 156. From week 20 to 156 data shown for n=56 and 103 patients in the normal baseline CRP and elevated baseline CRP groups, respectively. Data for secukinumab 150 mg and placebo at week 16, and for secukinumab 150 mg at week 156 are depicted. BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; MMRM, mixed-effect model repeated measure; N, number of patients with available baseline CRP (normal or elevated) included in this pooled study through week 16; n, number of patients in this pooled study from week 20 to 156.

Figure 3.

Percent of patients with ASDAS inactive disease grouped by normal or elevated CRP at baseline through week 156. §p<0.01; ‡p<0.05 vs placebo; missing values were imputed as non-response through week 16. MI presented from week 20 to 156 (shaded area) included n=56 and 103 in the normal baseline CRP and elevated baseline CRP groups, respectively. Data for secukinumab 150 mg and placebo at week 16 and for secukinumab 150 mg at week 156 are depicted. ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; CRP, C-reactive protein; MI, multiple imputation; N, number of patients with available baseline CRP (normal or elevated) included in this pooled study through week 16; n, number of patients in this pooled study from week 20 to 156.

BASDAI50 responses in the normal and elevated CRP groups were 27.8% and 39.2% with secukinumab 150 mg vs 7.0% and 10.5% with placebo (p<0.01 and p<0.0001), respectively. The ASAS partial remission response rate was 12.5% and 16.0% with secukinumab 150 mg vs 2.8% and 4.0% with placebo (p=0.07 and p<0.01) in the normal and elevated CRP groups, respectively, at week 16. These results were further improved after 156 weeks of secukinumab treatment in both groups (BASDAI50: 40.4% and 60.6%; ASAS partial remission: 14.4% and 32.1%, in normal and elevated CRP groups, respectively).

Efficacy outcomes in the additional groups by CRP ranges of ≥5 to <10 mg/L, ≥10 to <15 mg/L and ≥15 mg/L showed higher responses in patients with higher CRP levels and are presented in online supplementary table S1.

Baseline CRP levels of <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L

Overall, 54.1% (212/392) of patients had a CRP level <10 mg/L and 45.9% (180/392) had a CRP level ≥10 mg/L. Efficacy outcomes in patients grouped by baseline CRP levels <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L are presented in table 2. The ASAS20/40 response rate at week 16 was 51.8%/33.6% with secukinumab 150 mg compared with 29.4%/9.8% with placebo (p<0.01/0.001) in the <10 mg/L group and 72.4%/47.1% vs 28.0%/15.1% (both p<0.0001) with secukinumab vs placebo in the ≥10 mg/L group. Similar improvements were observed in both groups for other efficacy endpoints at week 16, which were sustained or further improved over 156 weeks of secukinumab treatment (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical efficacy in patients grouped by baseline CRP levels: <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L

| Week | Baseline CRP levels <10 mg/L | Baseline CRP levels ≥10 mg/L | |||

| Pooled secukinumab 150 mg (N=110) |

Pooled placebo (N=102) |

Pooled secukinumab 150 mg (N=87) |

Pooled placebo (N=93) |

||

| ASAS20, % | 16 | 51.8** | 29.4 | 72.4**** | 28.0 |

| 156 | 63.0 | – | 83.3 | – | |

| ASAS40, % | 16 | 33.6*** | 9.8 | 47.1**** | 15.1 |

| 156 | 44.5 | – | 70.3 | – | |

| BASDAI, mean change from baseline | 16 | −1.99**** | −0.86 | −2.78**** | −0.62 |

| 156 | −2.73 | – | −3.62 | – | |

| BASDAI50, % | 16 | 30.0** | 10.8 | 41.4**** | 7.5 |

| 156 | 46.0 | – | 61.8 | – | |

| ASDAS inactive disease, % | 16 | 20.0** | 4.9 | 12.6* | 1.1 |

| 156 | 28.9 | – | 15.6 | – | |

| ASAS partial remission, % | 16 | 16.4** | 2.9 | 12.6* | 4.3 |

| 156 | 21.7 | – | 31.1 | – | |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 vs placebo; missing values were imputed as non-response at week 16. MI and MMRM data presented at week 156 included n=88 and 71 in baseline CRP levels <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L, respectively. For BASDAI, LS mean change from baseline was presented using MMRM at weeks 16 and 156.

ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society criteria; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; LS, least squares; MI, multiple imputation; MMRM, mixed-effect model repeated measures; N, number of patients included in this pooled study at week 16; n, number of patients in this pooled study at week 156.

Efficacy in patients with or without a 50% decrease in baseline CRP

A higher proportion (140/197 (71.1%)) of patients in the secukinumab 150 mg group reported a CRP decrease of 50% from baseline at week 4 compared with the placebo (28/193 (14.5%)) group. The ASAS20 response rate at week 16 was 72.1% with secukinumab 150 mg compared with 35.7% with placebo (p<0.001) in patients with a 50% CRP decrease, and the response rate was 33.3% vs 27.9% (p=0.31) in patients without a 50% CRP decrease. Improvements across all other efficacy endpoints were observed at week 16 in patients with a 50% CRP decrease treated with secukinumab versus placebo, except for ASDAS inactive disease and ASAS partial remission response rates (table 3). These results were sustained or further improved after 156 weeks of secukinumab treatment (table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical efficacy in subgroups of patients with or without 50% CRP decrease from baseline by week 4

| Week | With 50% CRP decrease by week 4 | Without 50% CRP decrease by week 4 | |||

| Pooled secukinumab 150 mg (N=140) |

Pooled placebo (N=28) |

Pooled secukinumab 150 mg (N=57) |

Pooled placebo (N=165) |

||

| ASAS20, % | 16 | 72.1*** | 35.7 | 33.3 | 27.9 |

| 156 | 77.8 | – | 56.2 | – | |

| ASAS40, % | 16 | 49.3** | 14.3 | 15.8 | 12.1 |

| 156 | 64.1 | – | 32.3 | – | |

| BASDAI, mean change from baseline | 16 | −2.69**** | −0.60 | −1.34 | −0.78 |

| 156 | −3.42 | – | −2.22 | – | |

| BASDAI50, % | 16 | 42.1** | 10.7 | 17.5* | 9.1 |

| 156 | 60.8 | – | 33.1 | – | |

| ASDAS inactive disease, % | 16 | 21.4 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 3.6 |

| 156 | 25.3 | – | 16.6 | – | |

| ASAS partial remission, % | 16 | 18.6 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 4.2 |

| 156 | 31.8 | – | 7.7 | – | |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 vs placebo; missing values were imputed as non-response at week 16. MI and MMRM data presented at week 156 included n=120 and 39 with and without 50% CRP decrease by week 4, respectively. One placebo patient from each study (MEASURE 1 and 2) did not included in the analysis of 50% CRP decrease by week 4 due to unavailability of the post baseline CRP value. For BASDAI, LS mean change from baseline was presented using MMRM at weeks 16 and 156.

ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society criteria; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; LS, least squares; MI, multiple imputation; MMRM, mixed-effect model repeated measures; N, number of patients included in this pooled study at week 16; n, number of patients in this pooled study at week 156.

Discussion

Long-term (156-week) efficacy and safety results of secukinumab in AS from the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 studies have been reported previously.17 18 This report focuses on the pooled efficacy of secukinumab 150 mg over 3 years across both patients grouped by baseline CRP levels (<5 mg/L (normal) or ≥5 mg/L (elevated) and <10 mg/L or ≥10 mg/L) and by the proportion of patients with a CRP decrease of 50% from baseline by week 4. In this post hoc analysis, secukinumab 150 mg showed improvement across all efficacy endpoints by week 16 in patients with AS in both normal and elevated baseline CRP levels, with a greater magnitude of improvement observed in patients with elevated levels of baseline CRP, except for ASDAS inactive disease. A similar trend of improvement was also observed across all efficacy endpoints in patients grouped by baseline CRP <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L, except for ASDAS inactive disease. A higher proportion of secukinumab-treated patients with a CRP decreased by 50% from baseline at week 4 reported improvement in all efficacy endpoints at week 16. All these improvements were sustained or further improved over 156 weeks of secukinumab treatment.

It has been reported that a higher CRP level is a predictor of improved ASAS20 and ASAS40 responses in patients with AS receiving TNFi therapy.6 12 In this pooled study, treatment response to secukinumab was not dependent on baseline CRP level, with the majority of patients in the normal (57%), elevated (63%), <10 mg/L (52%) and ≥10 mg/L (72%) baseline CRP groups achieving an ASAS20 response by 16 weeks of secukinumab treatment. The ASAS40 responders at week 16 were comparable across these groups: normal (35%), elevated (42%), <10 mg/L (34%) and ≥10 mg/L (47%). These responses improved across all baseline CRP groups through long-term (156 week) secukinumab treatment. This analysis shows that patients with normal baseline CRP levels also have a strong likelihood of experiencing a positive treatment response with IL-17A inhibition.

Improvement of the ASDAS composite index measuring disease activity has been associated with elevated baseline CRP level in patients receiving TNFi therapy.29 Individual items in the BASDAI and baseline CRP level are components of the ASDAS composite index and, therefore, are used to determine ASDAS inactive disease response rate.30 In our study, 19% of patients with normal and 15% of patients with elevated baseline CRP attained ASDAS inactive disease status with secukinumab at week 16. Similarly, the change in BASDAI score was −2.2 in the normal CRP and −2.4 in the elevated CRP groups with secukinumab treatment at week 16. Comparable results were also reported in patients with baseline CRP <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L groups for ASDAS inactive disease status and BASDAI score. These findings further confirm that attaining ASDAS inactive disease status and improvement in BASDAI score with secukinumab treatment is not dependent on having an elevated baseline CRP value, as improvements were seen across the full patient spectrum, regardless of baseline levels of inflammation. This is in contrast to previous studies of TNFi therapies in patients with AS.31–35 However, it is possible that the number of patients with normal CRP at baseline treated in prior studies with TNFi was too low to show significant response rates. A recent study in non-radiographic axSpA showed that patients treated with the TNFi who had normal CRP values, and no MRI findings at baseline had ASAS40 response rates of 42% with TNFi vs 25% with placebo (p=0.264).36 Nevertheless, regulatory authorities currently request that patients in non-radiographic axSpA studies have either an abnormal CRP and/or positive MRI findings at baseline for the purposes of inclusion.

The BASDAI50 response rate in secukinumab-treated patients was higher (39%) in the elevated baseline CRP group versus the normal group (28%) at week 16. Similarly, in the higher hurdle efficacy endpoint of ASAS partial remission, a higher proportion (16%) of patients in the elevated baseline CRP group responded at week 16, which was further improved (32%) by week 156, compared with the patients with normal baseline CRP (13% at week 16% and 14% at week 156). These response rates in secukinumab-treated patients were more comparable across the baseline CRP <10 mg/L and ≥10 mg/L groups at week 16. Thus, while it is not exclusively required for responsiveness to secukinumab treatment, an elevated baseline CRP level has a positive influence on efficacy in signs and symptoms in AS. These results with IL-17A-inhibition are in-line with research suggesting that elevated baseline CRP is a predictor of improvements in BASDAI50 and ASAS partial remission in patients with AS on TNFi therapy.7 12 37

Achieving at least a 50% decrease in CRP by week 4 was analysed as a key threshold, since the average group-level reduction in CRP levels in the MEASURE 1 and 2 studies with secukinumab treatment was 50%.15 In patients with at least a 50% CRP decrease by week 4, the ASAS20 response rate at week 16 was 72% compared with 33% in patients with less than a 50% CRP decrease. Similar trends of improvement in patients with at least a 50% CRP decrease by week 4 were observed across all efficacy endpoints at week 16, which were sustained or further improved over 156 weeks of secukinumab treatment. The results of our study suggest that an early reduction of CRP levels may be a predictor of treatment response to secukinumab. Conversely, patients showing a <50% decrease in CRP at week 4 are less likely to respond to secukinumab at week 16. To what extent those patients could benefit from an increased dose of secukinumab after week 4 is an open question. It remains to be seen whether higher doses of secukinumab may be able to reduce CRP levels further in these patients and/or lead to greater improvements in AS signs and symptoms. The 300 mg dose of secukinumab is being evaluated in AS in ongoing clinical studies. However, although reflective of an association between CRP level, inflammation and clinical symptoms, the thresholds of CRP reduction assessed in this study may not reflect consistently reproducible clinical phenotypes and, therefore, need to be explored further.

A limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 studies did not stratify randomisation by baseline CRP level. In addition, although a hsCRP assay was used, detection of a 50% drop in CRP values would be more challenging in patients with normal baseline CRP values (<5 mg/L) due to detection limits of the laboratory assay. Other design limitations include the lack of a comparator group beyond week 16 and the fact that, although originally randomised treatment groups were blinded in these studies up to week 104, the nature of the study designs determined that patients and investigators were aware that all patients received secukinumab from week 16 onward, which may have introduced systematic bias in the reporting of results.

In conclusion, secukinumab 150 mg provided sustained long-term improvement over 3 years in multiple clinical domains in a mixed population of patients with AS with or without increased baseline CRP level, who were either naïve or had responded inadequately to TNFi treatment. While a substantial percentage of patients with normal baseline CRP values can respond to secukinumab, the magnitude of response is higher in patients with increased baseline CRP. Inclusion of prospectively planned analyses by baseline CRP level in future clinical trials would help guide treatment strategies for patients with AS with normal, as well as elevated, baseline CRP.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 studies, the study investigators, John Gallagher, medical consultant for Novartis Pharma AG, Niladri Maity, senior scientific writer for Novartis, India and Neeta Pillai, scientific editor for Novartis, India. The first draft of this manuscript was written by Niladri Maity based on input from all the authors, and scientific review support was provided by Neeta Pillai.

Footnotes

Presented at: This manuscript based on the work previously presented at the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Annual Meeting, November 3-8, 2017, San Diego, United States. JB, JS, RL, et al. Secukinumab Demonstrates Rapid and Sustained Efficacy in Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients with Normal or Elevated Baseline CRP Levels: Pooled Analysis of Two Phase 3 Studies [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69(Suppl 10).

Contributors: All authors participated in the interpretation of data, critical review and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was sponsored by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland and designed by the scientific steering committee and Novartis personnel. Medical writing support was funded by Novartis.

Competing interests: JB has received research grant from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer, Celgene, Celltrion, Centocor, Chugai, EBEWE Pharma, Medac, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB, and served as consultant or paid speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer, Celgene, Celltrion, Centocor, Chugai, EBEWE Pharma, Medac, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. AD has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB, and has received honorarium for serving on the advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. RL has received research grant from Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB, and Wyeth, served as consultant for AbbVie, Ablynx, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, GSK, Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB, and Wyeth, and paid speaker for Abbott, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB, Wyeth. XB has received research grant from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Chugai, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and Werfen, served as consultant or paid speaker for AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Chugai, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and Werfen. CMR has received research grant from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, and Wyeth, served as consultant for Pfizer, Roche, UCB, Wyeth, and Merck, and paid speaker for Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, and Wyeth. JS has received research grant from AbbVie, Pfizer, and Merck, served as consultant for AbbVie, Pfizer, Merck, UCB, and Novartis, and paid speaker for AbbVie, Pfier, Merck, and UCB. EQF is an employee of Novartis. RM, BP, KKG are employees of Novartis and own Novartis stock. DVH served as consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Daiichi, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda, UCB.

Patient consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all screened patients.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each participating site and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Novartis is committed to sharing with qualified external researchers access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents from eligible studies. These requests are reviewed and approved the basis of scientific merit. All data provided is anonymised to respect the privacy of patients who have participated in the trial in line with applicable laws and regulations. The data may be requested from the corresponding author of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet 2007;369:1379–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60635-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bodur H, Ataman S, Rezvani A, et al. . Quality of life and related variables in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Qual Life Res 2011;20:543–9. 10.1007/s11136-010-9771-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reveille JD, diagnosis Bfor. Biomarkers for diagnosis, monitoring of progression, and treatment responses in ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:1009–18. 10.1007/s10067-015-2949-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, et al. . ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1811–8. 10.1136/ard.2008.100826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vastesaeger N, van der Heijde D, Inman RD, et al. . Predicting the outcome of ankylosing spondylitis therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:973–81. 10.1136/ard.2010.147744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis JC, Van der Heijde DM, Dougados M, et al. . Baseline factors that influence ASAS 20 response in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with etanercept. J Rheumatol 2005;32:1751–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, et al. . Prediction of a major clinical response (BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:665–70. 10.1136/ard.2003.016386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Vries MK, van Eijk IC, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, et al. . Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level, and serum amyloid a protein for patient selection and monitoring of anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1484–90. 10.1002/art.24838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. . 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smolen JS, van der Heijde D, Machold KP, et al. . Proposal for a new nomenclature of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:3–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, et al. . 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:896–904. 10.1136/ard.2011.151027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rudwaleit M, Claudepierre P, Wordsworth P, et al. . Effectiveness, safety, and predictors of good clinical response in 1250 patients treated with adalimumab for active ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:801–8. 10.3899/jrheum.081048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braun J, Baraliakos X, Hermann KG, et al. . Serum C-reactive protein levels demonstrate predictive value for radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis treated with golimumab. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1704–12. 10.3899/jrheum.160003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rudwaleit M, Schwarzlose S, Hilgert ES, et al. . MRI in predicting a major clinical response to anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1276–81. 10.1136/ard.2007.073098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. . Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei JC, Baeten D, Sieper J, et al. . Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in Asian patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: 52-week pooled results from two phase 3 studies. Int J Rheum Dis 2017;20:589–96. 10.1111/1756-185X.13094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baraliakos X, Kivitz AJ, Deodhar AA, et al. . Long-term effects of interleukin-17A inhibition with secukinumab in active ankylosing spondylitis: 3-year efficacy and safety results from an extension of the Phase 3 MEASURE 1 trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018;36:50–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marzo-Ortega H, Sieper J, Kivitz A, et al. . Secukinumab provides sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms of active ankylosing spondylitis with high retention rate: 3-year results from the phase III trial, MEASURE 2. RMD Open 2017;3:e000592 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. . A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gossec L, Portier A, Landewé R, et al. . Preliminary definitions of 'flare' in axial spondyloarthritis, based on pain, BASDAI and ASDAS-CRP: an ASAS initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:991–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Fleischmann R, et al. . Early disease activity or clinical response as predictors of long-term outcomes with certolizumab pegol in axial spondyloarthritis or psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:1030–9. 10.1002/acr.23092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Price CP, Trull AK, Berry D, et al. . Development and validation of a particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay for C-reactive protein. J Immunol Methods 1987;99:205–11. 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90129-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eda S, Kaufmann J, Roos W, et al. . Development of a new microparticle-enhanced turbidimetric assay for C-reactive protein with superior features in analytical sensitivity and dynamic range. J Clin Lab Anal 1998;12:137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. . The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:ii1–44. 10.1136/ard.2008.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braun J, Davis J, Dougados M, et al. . First update of the international ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:316–20. 10.1136/ard.2005.040758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. . Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:47–53. 10.1136/ard.2010.138594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inman RD, Baraliakos X, Hermann KA, et al. . Serum biomarkers and changes in clinical/MRI evidence of golimumab-treated patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of the randomized, placebo-controlled GO-RAISE study. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:304 10.1186/s13075-016-1200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van der Heijde D, Joshi A, Pangan AL, et al. . ASAS40 and ASDAS clinical responses in the ABILITY-1 clinical trial translate to meaningful improvements in physical function, health-related quality of life and work productivity in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 2016;55:80–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, et al. . Predictors of treatment response and drug continuation in 842 patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor: results from 8 years' surveillance in the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:2002–8. 10.1136/ard.2009.124446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lord PA, Farragher TM, Lunt M, et al. . Predictors of response to anti-TNF therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: results from the British society for rheumatology biologics register. Rheumatology 2010;49:563–70. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arends S, Brouwer E, van der Veer E, et al. . Baseline predictors of response and discontinuation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocking therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective longitudinal observational cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R94 10.1186/ar3369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fagerli KM, Lie E, van der Heijde D, et al. . Selecting patients with ankylosing spondylitis for TNF inhibitor therapy: comparison of ASDAS and BASDAI eligibility criteria. Rheumatology 2012;51:1479–83. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vastesaeger N, Cruyssen BV, Mulero J, et al. . ASDAS high disease activity versus BASDAI elevation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis as selection criterion for anti-TNF therapy. Reumatol Clin 2014;10:204–9. 10.1016/j.reuma.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sixteen-week study of subcutaneous golimumab in patients with active nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2702–12. 10.1002/art.39257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baraliakos X, Koenig AS, Jones H, et al. . Predictors of clinical remission under anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: pooled analysis from large randomized clinical trials. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1418–26. 10.3899/jrheum.141278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2018-000749supp001.docx (201.6KB, docx)