Abstract

Gymnema sylvestre R. Br., one of the most important medicinal plants of the Asclepiadaceae family, is a herb distributed throughout the World, predominantly in tropical countries. The plant, widely used for the treatment of diabetes and as a diuretic in Indian proprietary medicines, possesses beneficial digestive, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic and anti-helmentic effects. Furthermore, it is believed to be useful in the treatment of dyspepsia, constipation, jaundice, hemorrhoids, cardiopathy, asthma, bronchitis and leucoderma. A literature survey revealed that some other notable pharmacological activities of the plant such as anti-obesity, hypolipidemic, antimicrobial, free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties have been proven too. This paper aims to summarize the chemical and pharmacological reports on a large group of C-4 gem-dimethylated pentacyclic triterpenoids from Gymnema sylvestre.

Keywords: Gymnema sylvestre, triterpenoids, oleanes, pharmacological activities, phytochemistry

1. Introduction

Plant natural products from abundant species represent attractive and sustainable starting materials for the preparation of new bioactive substances. Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. is a valuable herb from the family Asclepiadaceae, widely distributed in India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Australia, Indonesia, Japan, Vietnam, tropical Africa and Southwestern China. Other scientific and common names in different languages are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Scientific names | |

|---|---|

| Gymnema sylvestre, Asclepias geminata, Asclepias geminata, Periploca sylvestris, Gymnema melicida | |

| Language | Common names |

| English | Gymnema, Cowplant, Australian cowplant, Gurmari, Gurmarbooti, Gurmar, Periploca of the woods, Meshasringa, Gemnema Melicida, Gimnema, Gur-Mar, Gymnema montanum, Gymnéma, Gymnéma Sylvestre, Miracle plant, Periploca sylvestris, Shardunika, Vishani, Ram’s horn, Miracle fruit, Merasingi, Small Indian ipecac, Sugar destroyer |

| Sanskrit | Meshashringi, Madhunashini, Ajaballi, Ajagandini, Bahalchakshu, Karnika, Chakshurabahala, Kshinavartta |

| Marathi | Kavali, Kalikardori, Vakundi |

| Hindi | Gurmar, Merasingi |

| Marathi | Kavali, Kalikardori, Vakundi |

| Gujrathi | Dhuleti, Mardashingi |

| Telugu | Podapatri |

| Tamil | Adigam, Cherukurinja, Sarkarikolli |

| Kannada | Sannager-asehambu |

| Malayalam | Chakkarakolli, Madhunashini |

| Bengali | Mera-Singi |

Gymnema sylvestre (GS) is considered to have potent anti-diabetic properties. This plant is also used for controlling obesity, in the form of Gymnema tea, and it is often called “gurmar” (destroyer of sugar), as chewing the leaves causes the loss of the ability to taste sweetness [4,5]. Extracts of its leaves and roots are used in India and parts of Asia as a natural treatment for diabetes, as they help lower and balance blood sugar levels [6]. In addition, the plant possesses antimicrobial [7], anti-hyphal [8] anti-hypercholesterolemic [9], and hepatoprotective activities [10]. It also acts as a feeding deterrent to the caterpillar Prodenia eridania [11], prevents dental caries caused by Streptococcus mutans [12] and is used in cosmetics [13]. In addition, it is also used in the treatment of rheumatism, cough, ulcer, jaundice, dyspepsia, constipation, asthma, eye complaints, inflammations and snake bites [14,15]. The taxonomy of the plant is described in Table 2 [16].

Table 2.

Taxonomy of Gymnema sylvestre.

| Kingdom | Plantae |

|---|---|

| Subkingdom | Tracheobionta |

| Superdivision | Spermatophyta |

| Division | Magnoliophyta |

| Class | Magnoliopsida |

| Subclass | Asteridae |

| Order | Gentianales |

| Family | Asclepiadaceae |

| Genus | Gymnema R. Br. |

| Species | sylvestre |

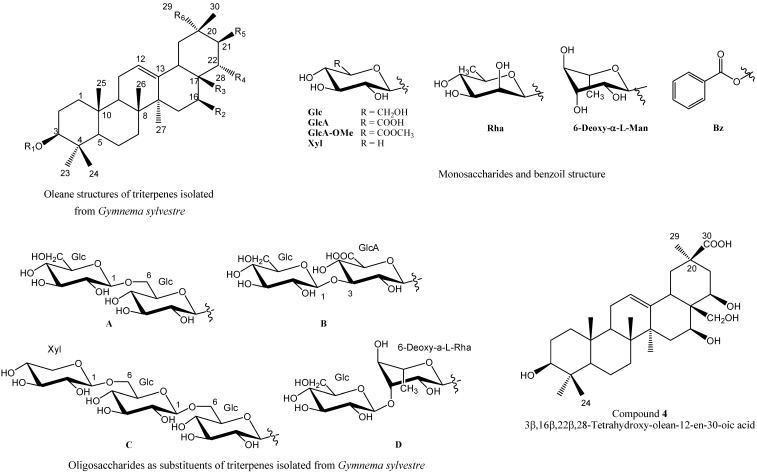

This paper aims to summarise the chemical and pharmacological reports on oleanes, a large group of pentacyclic triterpenoids gem-dimethylated at C-4 (Figure 1). The oleane skeleton includes a C12:13 double bond. The most common functional group in this class is the 3-OH substituent, which is present in the precursor squalene. Hydroxyl groups, free or acylated, are also present at C-16, C-21, C-22, C-28, and C-30. The first section of this review provides a general description of the plant, its chemical composition, extraction methods and uses. Then, the IUPAC names, biological activities and physical and chemical characterisation (IR, 1H and 13C-NMR, [α]D, X-ray, MS, etc.) of these compounds are described. These data have been obtained from various tables and references.

Figure 1.

General structures of oleane triterpenes isolated from Gymnema sylvestre.

2. Plant Description

GS is a vulnerable species. It is a slow growing large perennial and medicinal woody climber distributed throughout India in dry forests up to 600 m in height. GS is distributed across a large area, occurring from East Africa to Saudi Arabia, India, Sri Lanka, Vietnam and southern China, as well as Japan (Ryukyu Islands), the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Australia. In addition, it occurs throughout most of West Africa and extends to Ethiopia and South Africa [16,17]. The leaves of GS are green; the stems are hairy and light brown. The leaves are 2–6 cm in length and 1–4 cm in width and are simple, petiolate and opposite, with an acute apex and reticulate venation. They are pubescent on both surfaces [1,18]. They have a characteristic odour; the taste is slightly bitter and astringent. The leaves also possess the remarkable ability to inhibit the perception of sweet tastes for a few hours [19,20]. The flowers are small, yellow, in axillary and lateral umbel like cymes. The lobes of the calyces are long, ovate, obtuse and pubescent. The corolla is pale yellow, campanulate and valvate with a single corona and five fleshy scales [16,21,22,23]. The powdered material is slightly yellowish-green and is bitter tasting with a pleasant aromatic odour. When the powder is treated sequentially with 1 M aqueous NaOH and 50% KOH, it exhibits green fluorescence under UV at 254 nm; with 50% HNO3 in daylight, an orange colour is observed. The dilute hydro-alcoholic extract suppresses the ability to taste sweetness, foams copiously when shaken with water and forms a voluminous precipitate upon addition of dilute acid [22,24,25,26].

3. Chemical Composition

GS contains triterpene saponins belonging to the oleane and dammarene classes. Other constituents include formic, butyric and tartaric acids, flavones, anthraquinones, hentriacontane, pentatriacontane, α- and β-chlorophylls, phytin, resins, δ-quercitol, lupeol, β-amyrin-related glycosides and stigmasterol [27]. The plant extract also tests positive for alkaloids. In addition, the leaves yield acidic glycosides and anthraquinone derivatives. The pharmacological activities of GS are listed below.

4. Pharmacological Studies

4.1. Anti-Diabetic Activity and Mechanism of Action

GS has shown promising results as an anti-diabetic agent. The first scientific confirmation of the efficacy of GS in human diabetes came almost a century ago, when it was demonstrated that GS leaves reduce urinary glucose levels in diabetic subjects [28]. No adverse effect was observed; thus, it can be concluded that the powdered extract lowers fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels [2].

Several studies suggest that the hypoglycaemic activity of GS is due to stimulation of insulin release (and possibly regeneration of Langerhans islet β-cells), modulation of the enzymes responsible for glucose utilisation (increased phosphorylase activity and the decreased activity of gluconeogenic enzymes and sorbitol dehydrogenase) and inhibition of glucose absorption in the bowel [29,30,31,32]. Numerous studies using animal models have confirmed the hypoglycaemic effect of GS [33,34]. Microscopy of a group of animals receiving GS extract showed that the nuclei of β-endocrinocytes were significantly enlarged in all sections of the pancreas. Pancreatic islets occupied the same volume fraction and area [35], supporting the hypothesis that the use of GS increases the endogenous levels of insulin, possibly due to regeneration of pancreatic β-cells [36]. Other effects of GS extract include a prolonged hypoglyacemic action of exogenous insulin in dogs without a pancreas, an intensification of the effects of insulin, and an extended duration of reduced glucose levels [29]. Use of GS extracts to treat diabetes in rats significantly increases life expectancy. Plasma insulin was increased in mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus (DM) upon administration of the saponin fraction of the methanol extract of GS leaves or isolated triterpene glycosides [9]. The use of GS extracts for 21 days after streptozotocin intoxication reliably reduced plasma glucose levels, increased insulin levels (most likely due to increased membrane permeability rather than stimulation of exocytosis by other pathways) [37], and normalised high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [35] concentrations. Glycaemia and insulinaemia were restored to normal over 60 days in rats with diabetes after peroral administration of the alcohol fraction of GS extract. The number of Langerhans islets and β-cells in the pancreas doubled [31,38]. In 1990, the effects of a GS extract on type 1 and 2 DM were published [30]. Clinical trials were conducted in the USA on the patented preparation ProBeta, based on a GS extract [30,31,39,40]. Treatment of 27 patients with type 1 DM who were on insulin therapy with GS extract (400 mg/d) showed reduced fasting glucose levels, up to 35%, and normalised serum lipid concentrations. The required dose of exogenous insulin was reduced (up to 50%), and the level of endogenous insulin was increased 12 months after the start of treatment. It was proposed that GS increased the endogenous levels of insulin and C-peptide, possibly due to pancreatic regeneration.

4.2. Inhibitory Effects on Palatal Taste Response

Gymnema leaf and root extracts have been shown to affect the palatal taste response by interfering with the ability of the taste buds on the tongue to perceive sweet and bitter tastes. It is believed that inhibiting the perception of sweet taste may cause people taking it to limit their intake of sweet foods. This activity may be partially responsible for its hypoglycaemic effect [41]. The active compounds are thought to act by binding to the sweet taste receptor protein [42].

4.3. Hypolipidemic Activity

The altered blood lipid levels and hyperglycaemia associated with DM increase the risk of atherosclerosis [43]. Therefore, it is significant that GS not only possesses hypoglycaemic properties but can also correct impaired lipid exchange [9]. Extracts of GS have shown anti-atherosclerotic potential, with efficacy similar to the standard lipid-lowering agent clofibrate [9]. In vivo studies have been conducted primarily with rats. Significant decreases in fat absorption were observed when GS extract was administered orally to rats fed a high-fat or normal-fat diet. The administration of leaf extracts to hypolipidaemic rats for two weeks was found to reduce elevated serum triglycerides, total cholesterol, very low-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein levels in a dose-dependent manner [4,8]. An aqueous extract of GS was shown to suppress the accumulation of lipids in the liver of rats on a high fat diet to the same extent as chitosan [44]. Spontaneously hypertensive rats consuming extracts of GS showed a decrease in circulating cholesterol concentrations [45].

4.4. Anti-Obesity Activity

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and stroke. GS promotes weight loss through its ability to reduce sweet cravings and to control blood sugar levels [2,3,42,46]. A standardised GS extract in combination with niacin-bound chromium and hydroxycitric acid was evaluated for anti-obesity activity by monitoring changes in body weight, body mass index, appetite, lipid profiles and the excretion of urinary fat metabolites in moderately obese human volunteers.

4.5. Anti-Cancer Activity

The alcoholic extract of GS is a potent anti-cancer agent against the A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma) and MCF7 (human breast carcinoma) cell lines [47]. Additionally, the alcoholic extract of GS has been shown to inhibit intestinal breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) [48]. BCRP inhibition enhances the systemic availability of orally-administered drugs, including topotecan, irinotecan, nitrofurantoin, and sulfasalazine, by increasing absorption [48,49]. For this reason, GS extracts possess potent medicinal value in cancer treatment.

4.6. Haemolytic Activity and Mechanism of Action

Triterpene saponins usually show high haemolytic activity, whether they are neutral, acidic, or an ester saponin. Polar substituents on ring A and weakly polar substituents on rings D and E increase the lysis of erythrocyte membranes, which results in haemoglobin release. Triterpenes, acylglycosides, and saponins with strongly polar substituents on rings D and E exhibit a lower haemolytic activities [50,51]. With respect to the carbohydrate moiety, the situation is less clear. Haemolysis usually decreases with length and increases with branching of the sugar chain [52].

The molecular mechanism of these effects is not entirely clear. It seems that the first step is an irreversible interaction of the oligosaccharide chain with the erythrocyte membrane [53,54,55,56]. Therefore, the activity of a saponin is strongly influenced by the structure of the oligosaccharide moiety. In the following step, enzymatic deglycosylation releases the aglycon, which destroys the membrane locally. From the literature [57,58], it is evident that the haemolytic activity varies considerably with the structure of the glycoside.

4.7. Antimicrobial Activity

The crude ethanolic extract of GS leaves showed significant antibacterial activity against Bacillus pumilis, B. subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, but no activity against Proteus vulgaris or Escherichia coli [59]. The aqueous and methanolic extracts of the leaves also showed moderate activity against three pathogenic Salmonella species (Salmonella typhi, S. typhimurium and S. paratyphi) [60]. The chloroform and ethyl acetate extracts of the aerial parts of GS also exhibited activity against P. vulgaris, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Klebsella pneumoniae and S. aureus [61].

4.8. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The aqueous extract of GS leaves was investigated for anti-inflammatory activity in rats using carrageenan-induced paw oedema and the cotton pellet method at doses of 200, 300 and 500 mg/kg. The 300 mg/kg dose decreased paw oedema volume by 48.5% within 4 hours after administration [62], compared to the standard drug phenybutazone (57.6%). Additionally, doses of 200 and 300 mg/kg significantly reduced granuloma weight compared to the control group [18,62]. By elevating liver enzymes, such as γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and superoxide dismutase, extracts of GS show a protective effect against the release of slow-reacting substances and free radicals. The extracts did not inhibit granuloma formation or related biochemical indices, such as the hydroxyproline and collagen levels. Extracts of GS exhibited reduced gastrotoxicity even at high doses and did not affect the integrity of the gastric mucosa compared to other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents [63].

4.9. Anti-Larvicidal Activity

One ecological role of secondary metabolites is defence against phytophagous insects and pathogens. This suggests interesting applications in the search for new environmentally friendly, biodegradable, bioactive natural products that may avoid some of the deleterious environmental effects of synthetic pesticides [64,65,66]. Triterpenes and sterols have important roles in the acquisition of cholesterol by insects, which rely exclusively on exogenous cholesterol sources for normal growth, development, and reproduction [67]. Many terpenoids exhibit insecticidal and insect growth regulation (IGR) activities, inhibit enzymes and metabolism [68,69], and have antifeedant effects on phytophagous insects [70]. For example, aqueous extracts of GS show significant larvicidal activity against Culex larvae (44%–89% mortality in Culex quinquefasciatus) [71]. The extracts may also possess activity against the larvae of Anopheles subpictus [72].

4.10. Antioxidant Activity

GS extracts rich in oleane saponins have been examined for antioxidant activity. The IC50 values for DPPH scavenging, superoxide radical scavenging, inhibition of in vitro lipid peroxidation, and protein carbonyl formation were 238, 140, 99, and 28 μg/mL, respectively [73]. The antioxidant activity shown by the 55% v/v alcoholic GS extract may be due to the presence of flavonoids, phenols, tannins and triterpenoids, all of which were detected in preliminary phytochemical screening [4]. In vivo studies have shown that pre-treatment with GS extracts significantly enhanced the radiation (8 Gy)-induced augmentation of lipid peroxidation and depletion of glutathione and protein in mouse brain. Some multi-herbal ayurvedic formulations containing extracts of GS, such as Hyponidd and Dihar, have shown antioxidant activity by increasing the levels of superoxide dismutase, glutathione and catalase in rats [74,75].

4.11. Side-Effects

GS is considered safe when taken at the recommended doses. Short term use of low doses may have no noticeable side effects [76]. Extremely high doses may induce hypoglycaemia. Symptoms such as weakness, confusion, fatigue, shakiness, excessive sweating and loss of muscle control may occur. Gymnema may cause gastrointestinal distress, including abdominal cramping, nausea and vomiting, when taken on an empty stomach. Spontaneously hypertensive rats consuming GS showed no change in systolic blood pressure [45].

4.12. Toxicity

Several reports suggest that a reliably toxic dose of GS has not been found. The LD50 in mice and rats is greater than 5 g/kg [35]. Peroral administration of a hydro-alcoholic extract of GS (19.5:1) to mice at a dose of 0.25–8 g/kg did not produce any behavioural or neurological effects. Feeding studies lasting 52 weeks in rats including administration of 1% GS powder in the diet, showed no toxic effects; none of the animals died during this period [4]. No side effects were found upon administration of GS at doses of 0.50–0.56 g/kg/day in man [77]. GS has been reported to cause toxic hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury in patients who have been treated with this herb for diabetes mellitus [75]. D-400 (a formulation of herbs known for their hypoglycaemic actions that contains GS as one of the major components) showed no adverse effects on rats and no teratogenicity [78]. The plant increased the effectiveness of diabetic medication.

5. Discussion of the Specific Biological Activity of Tested Molecules

The aqueous extract of GS leaves shows potent anti-inflammatory activity in rats [62] and significant larvicidal activity, for example, against Culex quinquefasciatus [71] and Anopheles subpictus larvae [72].

Studies on the crude ethanolic extract of GS leaves showed significant antibacterial and anti-cancer activities. The LD50 values of the ethanolic and water extracts of GS administered intraperitoneally in mice was found to be 375 mg/kg [79]. In an acute toxicity study in mice, no gross behavioural, neurological, or autonomic effects were observed.

Not surprisingly, this plant has been and is still being studied by many research groups, as demonstrated by the publication of thousands of articles and the isolation of one hundred new and known molecules. However, few of the oleane triterpenoids isolated from GS that are gem-dimethylated at C-4 (see Figure 1 and Table 3 and Table 4 [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95], Table 5 [89,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105], Table 6 [81,82,83,88,89,91,92,93,94,95,103], Table 7 [51,89,95,99,100,104,105,106,107,108,109]) have been assayed (see Figure 1 and Table 8 [81,82,88,89,91,92,93,94,95,103,108,110,111,112,113,114,115] and Table 9 [51,89,95,99,102,103,104,105,108,111,112,115,116,117,118,119]).

Table 3.

Structures of gem-dimethylated oleanes isolated from Gymnema sylvestre.

| No. | CAS | Common Name | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 465-94-1 | Longispinogenin | H | OH | CH2OH | H | H | CH3 |

| 2 | 474-15-7 | Chichipegenin | H | OH | CH2OH | OH | H | CH3 |

| 3 | 53187-93-2 | Sitakisogenin | H | OH | CH2OH | H | OH | CH3 |

| 4 | 862377-55-7 | 3β,16β,22β,28-tetrahydroxy-olean-12-en-30-oic acid | See Figure 2 | |||||

| 5 | 287390-11-8 | Longispinogenin 3-O-β-d-glucuronopyranoside | GlcA | OH | CH2OH | H | H | CH3 |

| 6 | 287389-94-0 | 21β-O-Benzoylsitakisogenin 3-O-β-d-glucuronopyranoside |

GlcA | OH | CH2OH | H | Bz | CH3 |

| 7 | 873799-50-9 | Gymnemic acid A | GlcA | OH | CH2OH | H | H | COOH |

| 8 | 1096581-47-3 | Gymnemoside W2 | GlcA-OMe | OH | CH2OH | H | OH | CH3 |

| 9 | 330595-34-1 | Longispinogenin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-β-d-glucuronopyranoside potassium salt | B | OH | CH2OH | H | H | CH3 |

| 10 | 212775-47-8 | Alternoside VII | B | OH | CH2OH | OH | H | CH3 |

| 11 | 330595-32-9 | 21β-O-Benzoylsitakisogenin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-β-d-glucuronopyranoside | B | OH | CH2OH | H | Bz | CH3 |

| 12 | 330595-36-3 | 29-Hydroxylongispinogenin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-β-d-glucuronopyranoside potassium salt | B | OH | CH2OH | H | H | CH2OH |

| 13 | 1096581-44-0 | Gymnemoside W1 | A | OH | CH2OGlc | H | H | CH3 |

| 14 | 256510-01-7 | Alternoside XIX | C | OH | CH2OGlc | H | H | CH3 |

| 15 | 1422031-89-7 | 6-Deoxy-α-l-Rhamnopyranoside, (3β,16β,22α)-16-(hydroxy)-28-[(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)oxy]-22-hydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl | D | OH | CH2O(6-Deoxy-α-l)Man | OH | H | CH3 |

| 16 | 212775-23-0 | Alternoside II | B | OAc | CH2O(6-Deoxy-α-l)Man | OH | H | CH3 |

| 17 | 508-02-1 | Oleanolic acid | H | H | H | H | H | CH3 |

| 18 | 240140-86-7 | Oleanolic acid 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside | A | H | COOH | H | H | CH3 |

| 19 | 287389-96-2 | Oleanolic acid 3-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside | C | H | COOH | H | H | CH3 |

| 20 | 14162-53-9 | Oleanolic acid 28-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | H | H | COOGlc | H | H | CH3 |

| 21 | 78454-20-3 | Silphioside B | Glc | H | COOGlc | H | H | CH3 |

| 22 | 287389-95-1 | 3-O-β-d-Glucopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl oleanolic acid 28-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl ester | A | H | COOGlc | H | H | CH3 |

| 23 | 287389-97-3 | 3-O-β-d-Xylopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl oleanolic acid 28-β-d-glucopyranosyl ester | C | H | COOGlc | H | H | CH3 |

| 24 | 287389-98-4 | 3-O-β-d-Glucopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl oleanolic acid 28-β-d-glucopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl ester | A | H | COO-A | H | H | CH3 |

| 25 | 1422031-87-5 | 3β,16β,22α-Trihydroxy-olean-12-ene 3-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside | C | OH | CH3 | OH | H | CH3 |

Table 4.

Purification and biophysical properties of oleanes gem-dimethylated isolated from Gymnema sylvestre.

| No. | Chromatographic conditions | Melting point (°C) | IR analysis (cm−1) | Mass analysis | [α]D (Concentration, Solvent) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 247–249 | - | - | +53 (Acetone) | [80] |

| Preparative TLC (CH2Cl2/Me2CO, 17:3) | - | - | - | - | [81] | |

| - | 216–218 | - | EI: [M]+ 458 | +38.7 (c2.5, CHCl3) | [82] | |

| HR-ESI: [M]+ 458.3755 | ||||||

| - | 218–220 | - | - | +51.0 (CHCl3) | [83] | |

| - | 244–245 | - | - | - | [84] | |

| 2 | By synthesis | 315–317 | - | HR-ESI: [M-H2O]+ 456.3580 | +35.4 (c1.2, CHCl3) | [85] |

| - | 321–323 | - | - | +43 (c1, CHCl3) | [86] | |

| HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/CH3CN/H2O, 2:7:1) | - | - | - | - | [81] | |

| 3 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/CH3CN/H2O, 2:5:3) | - | - | - | - | [81] |

| HPLC (S-5; H2O/CH3CN, 63:37) | 333–335 | - | HR-ESI: [M-H2O]+ 456.3628 | +57.0 (c0.9, CHCl3:CH3OH 1:1) | [82,87] | |

| 4 | - | - | - | ESI: [M+H]+ 505, [M+Na]+ 527 | - | [88] |

| 5 | Silica gel column chromatography using as eluent CHCl3/CH3OH | 198–202 | 3414 (OH), 1724 | FAB: [M+Na]+ 657 | +16.08 (c0.10, CH3OH). | [89] |

| (COOH), 1636 (C=C), 1458, 1380, 1054. | ||||||

| 6 | Silica gel column chromatography using as eluent CHCl3/CH3OH | 192–195 | 3444 (OH), 1724, 1700, 1635 (C=C), 1457, 1388, 1280, 1074, 720. | FAB: [M+Na]+ 777 | +27.2 (c0.15, CH3OH). | [89] |

| 7 | - | - | - | - | - | [90] |

| 8 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 4:1) and Si-60 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1 to 5:2) | - | - | HR-ESI: [M+Na]+ 687.4085 | −6.5 (c0.01, CH3OH) | [91] |

| 9 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 1:4 to 7:3) | 305–310 | 3440, 2948, 1636, 1420, 1078, 1028 | HR-ESI: [(M.K)+H]+ 835.4065 | +18.1 (c0.08, CH3OH) | [92] |

| 10 | HPLC (ODS S-5, H2O/CH3CN, 4:1) | 213–215 | 3460, 1720, 1655, 1155 | FAB: [M−H]− 811 | +9.1 (c4.5, CH3OH) | [93] |

| 11 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 1:4 to 7:3) | 226–228 | 3422, 2948, 1702, 1636, 1460, 1388, 1282, 1160, 1076, 1026 | FAB: [M+H]+ 917, [M+Na]+ 939 | +15.4 (c0.16, CH3OH) | [92] |

| 12 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 1:4 to 7:3) | 290–293 | 3422, 2928, 1618, 1430, 1028 | FAB: [(M.K)+H]+ 851 | +10.3 (c0.12, CH3OH) | [92] |

| 13 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 4:1) and Si-60 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1 to 5:2) | - | - | ESI: [M-H]− 943 | −26.6 (c0.004, CH3OH) | [91] |

| [M-Glc]− 781, [M-2×Glc]− 619 | ||||||

| [M-3×Glc]− 457, [M+Na]+ 967 | ||||||

| HR-ESI: [M]+ 944.5290 | ||||||

| 14 | HPLC (YMC; S-5; H2O/CH3CN 3:1 to 13:7) | 187–189 | 3450, 1155 | FAB: [M-H]− 1075 | −23.4 (c3.1, CH3OH) | [94] |

| 15 | - | - | - | - | - | [95] |

| 16 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 1:4 to 7:3) | 294–296 | 3418, 2948, 1738, 1713, 1621, 1430, 1374, 1266, 1076, 1031 | FAB: [(M.K)+H]+ 1023 | +1.5 (c0.19, CH3OH) | [92] |

| HPLC (ODS S-5; H2O/CH3CN, 4:1) | 230–232 | 3400, 1730, 1665, 1240, 1160 | FAB: [M-H]− 999 | +2.3 (2.4, CH3OH) | [93] |

Table 5.

Purification and biophysical properties of oleanes gem-dimethylated isolated from Gymnema sylvestre.

| No. | Chromatographic conditions | Melting point (°C) | IR analysis (cm−1) | Mass analysis | [α]D (Concentration, Solvent) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H20, 30:1) | 296–298 | 3420, 2930, 1680 | EI: 456, 438, 248, 207, 203, 189 | +70.0 (c0.4, CHCl3) | [96] |

| HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H20, 4:1) | - | - | ESI: [M+CH3OH+ Na]+ 511, [M+Na]+ 479, 203, 191. | - | [97] | |

| HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/Acetic acid/Triethylamine, 99.55:0.30:0.15) | - | - | ESI: [M−H]− 455 | - | [98] | |

| 18 | Preparative TLC (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 4:1) | 220 (decomp.) | 3375, 2943, 1559, 1459, 1385, 1311, 1074, 1032, 913, 630 | LSI (%): [M+−H] 779 (18.4), 777(2.5), 733(0.5), 645(0.6), 617(3.0), 551(0.8), 497(0.5), 483(1.3), 455(2.8), 437(1.3), 367(6.0), 331(0.8), 275(24.2), 273(5.3), 183(100.0), 151(6.0), 91(100.0), 71(12.1), 45 (1.5) | +4.2 (c0.24, CH3OH) | [99] |

| 19 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 3:7 to 7:3) | 202–204 | 3410 (OH), 1710 (COOH), 1638 (C=C), 1458, 1036. | FAB: [M+Na]+ 935 | −3.28 (c0.15, CH3OH) | [89] |

| 20 | Silica gel column chromatography using as eluent CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O, 10:3:1 (lower layer) | - | - | ESI: [M+Na]+ 641.2 | - | [100,101] |

| CC silica gel, using EtOAc | [102] | |||||

| Flash chromatography (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 20:1) | 224–226 | 3435, 2944, 2873, 1735, 1460, 1385, 1072, 1029 | ESI: [M+Na]+ 641.4 | - | [103] | |

| 21 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 6:4) | - | - | FAB: [M−H]− 779, | - | [104] |

| [(M−H)−162]− 617, | ||||||

| [(M−H)−178]− 601 | ||||||

| HPLC (RP-C8; CH3OH/H2O) | - | - | HR-ESI: [M+Na]+ 803.4509 | - | [105] | |

| HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 13:7) | 230 | - | Incorrect data | −6.3 (c0.17, MeOH) | [103] | |

| 22 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 3:7 to 7:3) | 206–209 | 3424 (OH), 1735 (COOH), 1636 (C=C), 1457, 1034 | FAB: [M+Na]+ 943 | −6.5 (0.11, MeOH) | [89] |

| 23 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 3:7 to 7:3) | 212–215 | 3414 (OH), 1740 (COOR), 1636 (C=C), 1460, 1364, 1044, 896 | FAB: [M+Na]+ 1097 | −9.68 (c0.20, MeOH). | [89] |

| 24 | HPLC (RP-C18; CH3OH/H2O, 3:7 to 7:3) | 209–211 | 3424 (OH), 1734 (COOR), 1636 (C=C), 1458, 1074. | FAB: [M+Na]+ 1127 | −12.18 (c0.12, MeOH) | [89] |

| 25 | - | - | - | - | - | [95] |

Table 6.

Systematic names and chemical and spectral data of compounds 1–16.

| No. | Mol. formula | Mol. weight | Aspect | 1H-NMR | 13C-NMR | Systematic Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C30H50O3 | 458.72 | Amorphous powder | CDCl3 | CDCl3 | Olean-12-ene-3β,16β,28-triol | [81,82,83] |

| - | C5D5N | [93] | |||||

| 2 | C30H50O4 | 474.72 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-ene-3β,16β,22α,28-tetrol | [81,82] |

| 3 | C30H50O4 | 474.72 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-ene-3β,16β,21β,28-tetrol | [81,83] |

| 4 | C30H48O6 | 504.70 | White amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-en-30-oic acid, 3,16,22,28-tetrahydroxy-, (3β,16β,20β,22β) a | [88] |

| 5 | C36H58O9 | 834.84 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β)-16,28-dihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl | [89] |

| 6 | C43H62O11 | 754.95 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,21β)-21-benzoyloxy-16,28-dihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl | [89] |

| 7 | C36H56O11 | 664.82 | N. a. | N. a. | N. a. | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,20α)-20-carboxy-16,28-dihydroxy-30-norolean-12-en-3-yl | [103] |

| 8 | C37H60O10 | 664.87 | White powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,21β)-16,21,28-trihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl, methyl ester | [91] |

| 9 | C42H68O14K | 836.08 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β)-16,28-dihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-, monopotassium salt | [92] |

| 10 | C42H68O15 | 812.98 | Colorless needles | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,22α)-16,22,28-trihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl | [93] |

| 11 | C49H72O16 | 917.09 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,21β)-21-benzoyloxy-16,28-dihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl | [92] |

| 12 | C42H68O15K | 852.08 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,20α)-16,28,29-trihydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-, monopotassium salt | [92] |

| 13 | C48H80O18 | 945.14 | White powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranoside, (3β,16β)-28-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy-16-hydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 6-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl | [91] |

| 14 | C53H88O22 | 1077.25 | Colorless needles | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranoside, (3β,16β)-28-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy-16-hydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 6-[β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl] | [94] |

| 15 | C48H80O17 | 929.14 | White amorphous powder | N. a. | N. a. | 6-Deoxy-α-l-Rhamnopyranoside, (3β,16β,22α)-16-(hydroxy)-28-[(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)oxy]-22-hydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl | [95] |

| 16 | C50H80O20 | 1001.16 | Colorless needles | C5D5N | C5D5N | β-d-Glucopyranosiduronic acid, (3β,16β,22α)-16-acetyloxy-28-[(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)oxy]-22-hydroxyolean-12-en-3-yl 3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl | [92,93] |

a There is no correspondence between the structure and name of the compound reported in the literature and as indicated by the CAS number; N. a. = Not available.

Table 7.

Systematic names and chemical and spectral data of compounds 17–25.

| No. | Mol. formula | Mol. weight | Aspect | 1H-NMR | 13C-NMR | Systematic Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | C30H48O3 | 456.70 | White solid | C5D5N | C5D5N | 3β-Hydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid | [107] |

| CD3OD | CD3OD | [106] | |||||

| 18 | C42H68O13 | 780.98 | White solid | CD3OD | CD3OD | Olean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-[(6-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-, (3β) | [99] |

| C5D5N | C5D5N | [51] | |||||

| 19 | C47H76O17 | 913.10 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-[(O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-, (3β) | [89] |

| 20 | C36H58O8 | 618.84 | Colorless powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Oleanolic acid 28-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | [100] |

| 21 | C42H68O13 | 780.98 | White amorphous powder | - | CDCl3 | 3-O-(β-d-Glucopyranosyl)-oleanolic acid-28-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | [108] |

| - | C5D5N | [105] | |||||

| CD3OD | CD3OD | [104] | |||||

| 22 | C48H78O18 | 943.12 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-[(6-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-, β-d-glucopyranosyl ester, (3β)- | [89,109] |

| 23 | C53H86O22 | 1075.24 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-[(O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-, β-d-glucopyranosyl ester, (3β) | [89,95] |

| 24 | C54H88O23 | 1105.26 | Amorphous powder | C5D5N | C5D5N | Olean-12-en-28-oic acid, 3-[(6-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-, 6-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl ester, (3β) | [89] |

| 25 | C47H78O17 | 915.11 | N. a. | N. a. | N. a. | 3β,16β,22α-Trihydroxy-olean-12-ene 3-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside | [95] |

N. a. = Not available.

Table 8.

Biological activity of compounds 1–16 and their natural sources.

| No. | Part of the plant | Extract | Reference | Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stems | EtOH | [110] | Antitubercular activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv | [110] |

| Leaves | EtOH/H2O (19:1) | [111] | Inhibition on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase | [112] | |

| Aerial parts | CH2Cl2 | [81] | Anti-inflammatory | [113] | |

| 2 | Aerial parts | CH2Cl2 | [81] | Insect growth regulatory against Spodoptera frugiperda and Tenebrio molitor | [114] |

| Leaves | EtOH/H2O (19:1) | [111] | |||

| Stems | EtOH | [110] | |||

| Entire part | MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1:1) | [114] | |||

| 3 | Aerial parts | CH2Cl2 | [81] | - | - |

| Leaves | EtOH/H2O (19:1) | [111] | |||

| Leaves | EtOH | [108] | |||

| Stems | N. a. | [82] | |||

| 4 | Leaves | Not specified | [88] | - | - |

| 5 | Leaves | EtOH | [89] | Prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar, high blood lipids, or blood clotting | [115] |

| 6 | Leaves | EtOH | [89] | Prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar, high blood lipids, or blood | [115] |

| 7 | N. a. | N. a. | [103] | - | - |

| 8 | Leaves | EtOH/H2O (4:1) | [91] | - | - |

| 9 | Leaves | EtOH/H2O (3:2) | [92] | Antisweet activity | [92] |

| 10 | Roots | EtOH/H2O (7:3) | [93] | Antisweet activity | [93] |

| 11 | Leaves | EtOH/H2O (3:2) | [92] | Antisweet activity | [92] |

| 12 | Leaves | EtOH/H2O (3:2) | [92] | Antisweet activity | [92] |

| 13 | Leaves | EtOH/H2O (4:1) | [91] | - | - |

| 14 | Roots | EtOH | [94] | Antisweet activity | [94] |

| 15 | Stems | N. a. | [95] | - | - |

| 16 | Roots | EtOH/H2O (7:3) | [93] | Antisweet activity | [93] |

| Leaves | EtOH/H2O (3:2) | [92] | Antisweet activity | [92] |

Table 9.

Biological activity of compounds 17–25 and their natural sources.

| No. | Part of the plant | Extract | Reference | Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Leaves Leaves |

EtOH/H2O (19:1) H2O+microwave |

[111] [116,117] |

Inhibition on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase | [112] |

| Glucose uptake and gastric emptying | [101,118] | ||||

| Inhibition of Glycogen Phosphorylase | [108] | ||||

| 18 | Stems | N. a. | [95] | Haemolytic Activity | [99] |

| Obtained by synthesis | [99] | ||||

| 19 | Leaves | EtOH | [89] | Prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar, high blood lipids, or blood | [115] |

| 20 | Leaves | N. a. | [108] | Glucose uptake and gastric emptying | [101,118] |

| Haemolytic Activity | [51] | ||||

| Inhibition of Glycogen Phosphorylase | [103] | ||||

| Antimicrobial Activities | [119] | ||||

| 21 | Leaves | N. a. | [108] | Inhibition of the growth of HL60, A549 and | [105] [119] |

| Leaves | EtOH/H2O (3:2) | [105] | DU145 cancer cells | ||

| Leaves | MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1:1) | [104] | Amylase activity, total protein content and seedling growth | ||

| 22 | Leaves | EtOH | [89] | Prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar, high blood lipids, or blood | [115] |

| 23 | Leaves | EtOH | [89] | Prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar, high blood lipids, or blood | [115] |

| 24 | Leaves | EtOH | [89] | Prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar, high blood lipids, or blood | [115] |

| 25 | Stems | N. a. | [95] | - | - |

N. a. = Not available

For example, longispinogenin (1) was evaluated for anti-inflammatory activity in 12-O-tetra-decanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced inflammation in mice. The inhibitory effect was compared with that of a reference compound, quercetin (a known inhibitor of TPA-induced inflammation in mice), and two commercially available anti-inflammatory drugs, indomethacin and hydrocortisone. Longispinogenin (1) showed marked inhibitory activity, with an ID50 of 0.03–1.0 mg/ear, which was more potent than quercetin (1.6 mg/ear) and comparable to indomethacin (0.3 mg/ear) [113]. It also showed antitubercular activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv in Middlebrook 7H12 medium using the Microplate Alamar Blue Assay. Longispinogenin showed potent activity, although it was an order of magnitude less potent than the first-line antitubercular drug, rifampin [110]. Longispinogenin (1) and oleanolic acid (17) have been reported to strongly inhibit HIV-1 replication in H9 lymphocyte cells and in CEM 4 and MT-4 cells. However, the results of cell-free enzymatic assays should be cautiously extrapolated to the mode of action of these compounds in intact cells. In addition, these compounds were tested for inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT). RT is a key enzyme for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), as it catalyses the RNA- and DNA-dependent synthesis of double-stranded proviral DNA. Because replication of HIV is interrupted by RT inhibitors, inhibition of HIV RT is considered a useful approach for the prophylaxis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Several nucleosides; natural flavonoids, tannins and alkaloids; synthetic benzodiazepines and piperazine derivatives; and non-nucleoside-type compounds with diverse molecular structures have been reported as being HIV RT inhibitors. However, the efficacy of both nucleoside and non-nucleoside RT inhibitors is limited by high rates of viral mutation, which rapidly leads to the emergence of drug-resistant viral strains. Compounds possessing potent anti-HIV activity with novel structures and modes of action are urgently needed. Whereas oleanolic acid (17; 3.1 μM) was shown to possess potent inhibitory effect against HIV-1 RT, longispinogenin showed no or a weak inhibitory effect [112].

Chichipegenin (2) was evaluated for inhibition of the growth and development of the fall armyworm (FAW, Spodoptera frugiperda) and yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) by examining different aspects including insecticidal and growth-regulatory activities, rate of development, time of pupation, adult emergence, and deformities at each life stage [114].

Of those reported in Table 3, only compounds 9–12, 14 and 16 have been assayed for anti-sweetness activity. Solutions of these compounds (5 mL, 1 mM) were evaluated in adult volunteers using the method of Maeda et al. [120]. Each participant held the solution in the mouth with distilled water. Immediately after this, different concentrations of sucrose (0.5–0.1 M) were administered. The sweetness-inhibiting activity of each compound was expressed as the maximum concentration of sucrose for which sweetness was completely suppressed.

Compound 11 and the sodium salt of alternoside II (16) completely suppressed the sensation of sweetness. Compound 9, alternoside VII (10), alternoside XIX (14), and compound 12, which does not have an acyl group, were inactive even when tested at a lower concentration of sucrose (0.1 M) [92,93,94]. This finding seems to indicate that the anti-sweetness activity of these triterpene saponins is related to the presence of acyl groups on the D and E rings. This is consistent with the hypothesis that ester groups can play an important role in anti-sweetness activity.

Compounds 5, 6, 19, 22−24 are useful in the prevention or treatment of disorders related to high blood sugar and lipids or to blood clotting. In particular, compound 24 was tested in KunMing mice for inhibition of elevated blood glucose concentrations [115].

Only compound 18 has been evaluated for haemolytic activity (expressed as the Haemolytic Index (HI)) using the Austrian Pharmacopoeia method, with the Austrian Saponin standard HI.30000 as the reference [99]. Linkage of the terminal glucose to position 3 results in a compound with potent activity. Considering the significantly differing haemolytic indices for glycoside analogues, the investigation of other oleanolic acid glycosides seems promising. Furthermore, the effect of the configuration of the anomeric carbon attached to the aglycone should be investigated.

Oleane-type triterpene saponins are known to possess cytotoxic activity, but only silphioside B (21) was tested in vitro for cytotoxicity against three human tumour cell lines using the MTT assay: leukaemia (HL60), lung cancer (A549) and prostate cancer (DU145) [105]. This compound showed modest cytotoxicity. However, considering that this plant is both a medicine and a food, further studies should also be performed on other compounds. The influence of the oleanolic acid glycoside 21 on amylase activity and total protein content in wheat seedlings was studied [119]. Treatment of Triticum aestivum L. seeds with 1–10 μM aqueous solutions of 21 increased the α-amylase levels, total amylase activity and total protein content to an extent comparable to gibberellin A3 and 6-benzylaminopurine.

Compounds that reduce postprandial hyperglycaemia by inhibiting the absorption of carbohydrates have been shown to be effective for the prevention and the treatment of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. With this aim, oleanolic acid (17) and its 28-glucopyranoside derivative 20 were assayed to evaluate their effects on serum glucose in glucose-loaded and normal rats, but they showed no activity [101,118]. In addition, their anti-pruritic and gastromucosal protective effects have been evaluated in mice. Further experiments are necessary to gain insight into the mechanisms of action involved in these effects of saponins.

Compounds 17 and 20 showed good inhibition of rabbit muscle glycogen phosphorylase-a (GPa) monitored using a microplate reader (BIO-RAD) [108]. Briefly, GPa activity was measured by the release of phosphate from glucose 1-phosphate. Each test compound was diluted to different concentrations for IC50 determination, which was estimated by fitting the inhibition data to a concentration-effect curve using a logarithmic equation.

Pentacyclic triterpenes may exert hypoglycaemic effects, at least partially through GPa inhibition, but other mechanisms may also account for these effects. Further studies are needed to elucidate these molecular mechanisms in detail and to biologically evaluate natural and synthetic pentacyclic triterpenes as anti-diabetic agents.

Compound 20 has been tested for haemolytic activity using human erythrocytes in place of sheep cells. The corresponding haemolytic dose was defined as the final concentration that resulted in 50% of the haemolysis being caused by hypotonicity [51]. Comparing the results for oleanolic acid 17 with its 3- and 28-glucopyranoside (20) derivatives indicates that the sugar chain at the C-3 of oleanolic acid is essential, but that the sugar chain at C-28 results in inhibition of cytolytic activity; consequently, compound 20 exhibits little cytolytic activity.

6. Conclusions

Many Indian herbs are being used in traditional practice to cure diabetes. GS has an important place among such anti-diabetic medicinal plants and can also be used to treat dyspepsia, constipation, and jaundice, haemorrhoids, renal and vesicular calculi, cardiopathy, asthma, bronchitis, amenorrhoea, conjunctivitis and leucoderma. GS is a source of biologically active substances. A very broad spectrum of pharmacological activities has been reported, despite the fact that only a small proportion of isolated molecules were tested and that not all biological activities were evaluated. Some extracts and/or isolated compounds at various doses and in various combinations are beneficial in, among other things, the treatment of latent diabetes mellitus and the complex treatment of insulin-independent DM. In particular, some triterpenoids prolong the actions of hypoglycaemic preparations and promote regeneration of β-cells in insulin-dependent and insulin-independent DM. There has been rapid development in isolation and characterisation techniques as well as in in vivo studies using various rat and mouse models of life-threatening diseases. These compounds obviously require physicochemical characterisation, biological evaluation, toxicity studies, investigation of the molecular mechanism(s) of action and clinical trials. These classical approaches are necessary in the search for new lead molecules for the management of various diseases. Diabetes is becoming common throughout the world and many new drugs are being synthesised for treatment of this disorder. Many Indian herbs are being used in traditional practice to cure diabetes. GS has an important place among such anti-diabetic medicinal plants and can also be used to treat dyspepsia, constipation and jaundice, haemorrhoids, renal and vesicular calculi, cardiopathy, asthma, bronchitis, amenorrhoea, conjunctivitis and leucoderma. In future studies, compounds isolated from Gurmar must be evaluated scientifically using innovative experimental models and clinical trials to understand their mechanisms of action and to search for other active constituents in order for other therapeutic uses to be widely explored.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by AIPRAS Onlus (Associazione Italiana per la Promozione delle Ricerche sull’Ambiente e la Salute umana).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kanetkar P., Rekha S., Madhusudan K. Gymnema sylvestre: A memoir. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2007;41:77–81. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2007010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paliwal R., Kathori S., Upadhyay B. Effect of Gurmar (Gymnema sylvestre) powder intervention on the blood glucose levels among diabetics. Ethno. Med. 2009;3:133–135. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rachh P.R., Rachh M.R., Ghadiya N.R., Modi D.C., Modi K.P., Patel N.M., Rupareliya M.T. Antihyperlipidemic activity of Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. leaf extract on rats fed with high cholesterol diet. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2010;6:138–141. doi: 10.3923/ijp.2010.138.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh G.Y., Eisenberg D.M., Kaptchuk T.J., Phillips R.S. Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1277–1294. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurihara Y. Characteristics of antisweet substances, sweet proteins, and sweetness inducing proteins. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 1992;32:231–252. doi: 10.1080/10408399209527598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duke J.A., Jones P.M., Danny B., Jony D., Bully P. The Green Pharmacy. Rodale Press, Inc.; Emmaus, PA, USA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chodisetti B., Rao K., Giri A. Phytochemical analysis of Gymnema sylvestre and evaluation of its antimicrobial activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013;27:583–587. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.676548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vediyappan G., Dumontet V., Pelissier F., d’Enfert C. Gymnemic acids inhibit hyphal growth and virulence in Candida albicans. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishayee A., Malay C. Hypolipidaemic and antiatherosclerotic effects of oral Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. leaf extract in albino rats fed on a high fat diet. Phytother. Res. 1994;8:118–120. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2650080216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rana A.C., Avadhoot Y. Experimental evaluation of hepatoprotective activity of Gymnema sylvestre and Curcuma zedoaria. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granich M.S., Halpern B.P., Eisner T. Gymnemic acids: Secondary plant substances of dual defensive action. J. Insect Physiol. 1974;20:435–439. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiji Y. Cariostatic Materials and Foods, and Method for Preventing Dental Caries. 4912089A. U.S. Patent. 1990 Mar 27;

- 13.Komalavalli N., Rao M.V. In vitro micropropagation of Gymnema sylvestre–A multipurpose medicinal plant. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 2000;61:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kini R.M., Gowda T.V. Studies on snake venom enzymes: Part I Purification of ATPase, a toxic component of Naja naja venom and its inhibition by potassium gymnemate. Ind. J. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;22:152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kini R.M., Gowda T.V. Studies on snake venom enzymes: Part II Partial characterization of ATPases from Russell’s Viper (Vipera russelli) venom & their Interaction with potassium gymnemate. Ind. J. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;19:342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kritikar K., Basu B. Indian Medicinal Plants. International Book Distributors; Dehradun, India: 1998. p. 1625. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keshavamurthy K.R., Yoganarasimhan S.N. Flora of Coorg-Karnataka. Vimsat Publishers; Banglore, India: 1990. p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saneja A., Chetan S., Aneja K.R., Rakesh P. Gymnema sylvestre (Gurmar): A review. Der Pharm. Lett. 2010;2:275–284. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ninomiya Y., Imoto T. Gurmarin inhibition of sweet taste responses in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:1019–1025. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.4.R1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madhurima S.H., Ansari P., Alam S., Ahmad M.S., Akhtar S. Pharmacognostic and phytochemical analysis of Gymnema sylvestre R. (Br.) leaves. J. Herb. Med. Toxicol. 2009;3:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potawale S.E., Shinde V.M., Anandi L., Borade L., Dhalawat L., Deshmukh R.S. Development and validation of a HPTLC method for simultaneous densitometric analysis of gymnemagenin and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in herbal drug formulation. Pharmacologyonline. 2008;2:144–157. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhen H., Xu S., Pan S. Research on chemical constituents from stem of Gymnema sylvestre. Zhong Yao Cai. 2001;24:95–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurav S., Gulkari V., Durgkar N., Patil A. Systematic review: Pharmacognosy, phytochemistry, pharmacology and clinical applications of Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2007;1:338–343. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yackzan K.S. Biological effects of Gymnema sylvestre fractions. Alabama J. Med. Sci. 1966;3:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agnihotri A.K., Khatoon S., Agarwal M., Rawat A.K.S., Mehrotra S., Pushpangadan P. Pharmacognostical evaluation of Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2004;10:168–172. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi D.D. A method to prepare standardized extract of Gymnema sylvestre leaves for 75% gymnemic acids. IN2009DE00996 A. Indian Patent. 2009 Nov 19;

- 27.Sinsheimer J.E., Manni P.E. Constituents from Gymnema sylvestre leaves. J. Pharm. Sci. 1965;54:1541–1544. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600541035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charpurey K.G. Indian Medical Gazette. Spink&co; Calcutta, India: 1926. p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy M.L., Coulter I., Venuturupalli S., Roth E.A., Favreau J., Morton S.C., Shekelle P. Ayurvedic interventions for diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2001;41:977–983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baskaran K., Kizar A.B.K., Rhada S.K.R. Antidiabetic effect of a lead extract from Gymnema sylvestre in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1990;30:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(90)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanmugasundaram E.R., Rajeswari G., Baskaran K., Rajesh K.B.R., Radha S.K., Kizar A.B. Use of Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract in the control of blood glucose in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1990;30:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(90)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandey A., Tripathi P., Pandey R., Srivatava R., Goswami S. Alternative therapies useful in the management of diabetes: A systematic review. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2011;3:504–512. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhatt H.V., Mohan R.N., Panchal G.M. Differential diagnosis of byssinosis by blood histamine and pulmonary function test: A review and an appraisal. Int. J. Toxicol. 2001;20:321–327. doi: 10.1080/109158101753253054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srivastava Y., Nigam S.K., Bhatt H.V., Verma Y., Prem A.S. Hypoglycemic and lifeprolonging properties of Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract in diabetic rats. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 1985;21:540–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snigur G.L., Samokhina M.P., Pisarev V.B., Spasov A.A., Bulanov A.E. Structural alterations in pancreatic islets in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats treated with of bioactive additive on the basis of Gymnema sylvestre. Morfologiia. 2008;133:60–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chattopadhyay R.R. Possible mechanism of antihyperglycemic effect of Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract, Part I. Gen. Pharm. 1998;3:495–496. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(97)00450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nash R.J., Wilson F.X., Horne G. Compositions Comprising Imino Sugar Acids for Treatment of Energy Utilization Disease such as Metabolic Syndrome. WO 2009103953A1. PCT Int. Appl. 2009 Aug 27;

- 38.Shane-McWhorter L. Biological complementary therapies: A focus on botanical products in diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2001;14:199–208. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.14.4.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joffe D.J., Freed S.H. Effect of extended release Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract (Beta Fast G-XR) alone or in combination with oral hypoglycemics or insulin regimens for type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Control Newslett. 2001;76:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shapiro K., Gong W.C. Natural products used for diabetes. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2002;2:217–226. doi: 10.1331/108658002763508515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura Y., Tsumura Y., Tonogai Y., Shibata T. Fecal steroid excretion is increased in rats by oral administration of gymnemic acids contained in Gymnema sylvestre leaves. J. Nutr. 1999;129:1214–1222. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.6.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pothuraju R., Sharma R.K., Jayasimha C., Jangr S., Kumar P. A systematic review on Gymnema sylvestre in the obesity and diabetes management. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Starcevic J.N., Petrovic D. Carotid intima media-thickness and genes involved in lipid metabolism in diabetic patients using statins-a pathway toward personalized medicine. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2013;11:3–8. doi: 10.2174/1871525711311010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shigematsu N., Ryuji A., Makoto S., Mitsuo O. Effect of administration with the extract of Gymnema sylvestre R. Br leaves on lipid metabolism in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001;24:713–717. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preuss H.G., Jarrell S., Taylor S., Rich L., Shari A., Richard A. Comparative effects of chromium, vanadium and Gymnema sylvestre on sugar-induced blood pressure elevations in SHR. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1998;17:116–123. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierce A. Gymnema Monograph: Practical Guide to Natural Medicine. Stonesong Press Book; New York, NY, USA: 1999. pp. 324–326. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srikanth A.V., Sayeeda M., Lakshmi N., Ravi M., Kumar P., Madhava R.B. Anticancer activity of Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Nanotech. 2010;3:897–899. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamaki H., Satoh H., Satoko H., Hisakazu O., Yasufumi S. Inhibitory effects of herbal extracts on Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP) and structure-inhibitory potency relationship of isoflavonoids. Drug Metab. Pharm. 2010;25:170–179. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.25.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qingcheng M., Jashvant D.U. Role of the Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2) in drug transport. AAPS J. 2005;7:118–133. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romussi G., Cafaggi S., Bignardi G. Hemolytic action and surface activity of triterpene saponins from Anchusa officinalis L. Part 21: On the costituents of boraginaceae. Pharmazie. 1980;35:498–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hase J., Kobashi K., Mitsui K., Namba T., Yoshizaki M., Tomimori T. The structure-hemolysis relationship of oleanolic acid derivatives and inhibition of the saponin-induced hemolysis with sapogenins. J. Pharmacobiodyn. 1981;4:833–837. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schloesser E., Wulff G.Z. Uber die strukturspezifität des saponinhämolyse. I. Triterpensaponine und aglykone. Z. Naturforsch. B. 1969;24:1284–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Segal R., Milo-Goldzweig I. On the mechanism of saponins hemolysis. II. Inhibition of hemolysis by aldonolactones. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975;24:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(75)90317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Segal R., Milo-Goldzweig I., Seiffe M. The hemolytic properties of non-ionic hemolysins. Life Sci. 1972;11:61–70. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(72)90137-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Segal R., Schloesser E. Role of glycosidases in the membranlytic, antifungal action of Saponins. Arch. Microbiol. 1975;104:147. doi: 10.1007/BF00447315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Segal R., Shatovski P., Milo-Goldzweig I. Mechanism of saponin hemolysis. I. Hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974;23:973–981. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hostettmann K., Marston A. Saponins. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY, USA: 1995. p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gauthier C., Legault J., Girard-Lalancette K., Mshvildadze V., Pichette A. Haemolytic activity, cytotoxicity and membrane cell permeabilization of semi-synthetic and natural lupane- and oleanane-type saponins. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2009;17:2002–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Satdive R.K., Abhilash P., Devanand P.F. Antimicrobial activity of Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:699–701. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chand P., Shaik S., Sadath A., Ziaullah K. Anti salmonella activity of selected medicinal plants. Turk. J. Biol. 2008;33:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paul J.P., Jayapriya K. Screening of antibacterial effects of Gymnema sylvestre (L.) R.Br. Pharmacologyonline. 2009;3:832–836. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malik J.K., Manvi F.V., Alagawadi K.R., Noolvi M. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of Gymnema sylvestre leaves extract in rats. Int. J. Green Pharm. 2007;2:114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diwan P.V., Margaret J., Rama Krishna S. Influence of Gymnema sylvestre on inflammation. Inflammopharmacology. 1995;3:271–277. doi: 10.1007/BF02659124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubo I. Tyrosinase Inhibitors from Plants. In: Hedin P., Hollingworth R., Masler E., Miyamoto J., Thompson D., editors. Phytochemicals for Pest Control. Volume 685. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC, USA: 1997. pp. 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cespedes C.L., Martınez-Vazquez M., Calderon J.S., Salazar J.R., Aranda E. Insect growth regulatory activity of some extracts and compounds from Parthenium argentatum on fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Z. Naturforsch C. 2001;56:95–105. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-1-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Torres P., Avila J.G., Romo de Vivar A., Garcı´a A.M., Marı´n J.C., Aranda E., Ce´spedes C.L. Antioxidant and insect growth regulatory activities of stilbenes and extracts from Yucca periculosa. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:463–473. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikekawa N., Morisaki M., Fujimoto Y. Sterol metabolism in insects: Dealkylation of phytosterol to cholesterol. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:139–146. doi: 10.1021/ar00028a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kubo I., Klocke J.A. Isolation of Phytoecdysones as Insect Ecdysis Inhibitors and Feeding Deterrents. In: Hedin P.A., editor. Plant Resistance to Insects. Volume 208. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC, USA: 1983. pp. 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Caldero´n J.S., Ce´spedes C.L., Rosas R., Go´mez-Garibay F., Salazar J.R., Lina L., Aranda E., Kubo I. Acetylcholinesterase and insect growth inhibitory activities of Gutierrezia microcephala on fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith. Z. Naturforsch. C. 2001;56:382–394. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-5-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swain T. Tannins and Lignins. In: Rosenthal G.A., Janzen D.H., editors. Herbivores: Their Interactions with Secondary Plant Metabolites. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1979. pp. 657–682. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tandon P., Sirohi A. Assessment of larvicidal properties of aqueous extracts of four plants against Culex quinquefasciatus larvae. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2010;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khanna V.G., Kannabiran K., Rajakumar G., Rahuman A.A., Santhosh Kumar T. Biolarvicidal compound gymnemagenol isolated from leaf extract of miracle fruit plant, Gymnema sylvestre (Retz) Schult against malaria and filariasis vectors. Parasitol. Res. 2011;109:1373–1386. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharma K., Singh U., Vats S., Priyadarsini K., Bhatia A., Kamal R. Evaluation of evidenced-based radioprotective efficacy of Gymnema sylvestre leaves in mice brain. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2009;28:311–323. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.v28.i4.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Babu P.S., Stanely M.P.P. Antihyperglycaemic and antioxidant effect of hyponidd, an ayurvedic herbomineral formulation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2004;56:1435–1442. doi: 10.1211/0022357044607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patel S.S., Shah R.S., Goyal R.K. Antihyperglycemic, antihyperlipidemic and antioxidant effects of dihar, a polyherbal ayurvedic formulation in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2009;47:564–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dodson D., Mitchell D.R., Dodson D.C. The Diet Pill Guide: The Consumer’S Book of Over-the-Counter and Prescription Weight-Loss Pills and Supplements. St. Martin’s Press; 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, USA: 2001. p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ogawa Y., Sekita K., Umemura T., Saito M., Ono A., Kawasaki Y., Uchida O., Matsushima Y., Inoue T., Kanno J. Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract: A 52-week dietary toxicity study in wistar rats. Shōni Shikagaku Zasshi. 2004;45:8–18. doi: 10.3358/shokueishi.45.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russell F.E. Snake venom poisoning in the United States. Annu. Rev. Med. 1980;31:247–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.31.020180.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bhakuni D.S., Dhar M.L., Dhar M.M., Dhawan B.N., Gupta B., Srimal R.C. Screening of Indian plats for biological activity. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 1971;9:91–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Djerassi C., McDonald R.M., Lemin A.J. Terpenoids. III. 1 The isolation of erythrodiol, oleanolic acid and a new triterpene triol, longispinogenin, from the cactus Lemaiveocevcus longispinus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953:5940–5942. doi: 10.1021/ja01119a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zarrelli A., Della Greca M., Ladhari A., Haouala R., Previtera L. New triterpenes from Gymnema sylvestre. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2013;96:1036–1045. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201200331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yoshikawa K., Taninaka H., Kan Y., Arihara S. Antisweet natural products. XI. Structures of sitakisosides VI–X from Stephanotis lutchuensis Koidz. var. Japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994;42:2455–2460. doi: 10.1248/cpb.42.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tori K., Yoshimura Y., Seo S., Sakurawi K., Tomita Y., Ishii H. Carbon-13 NMR spectra of saikogenins. Stereochemical dependence in hydroxylation effects upon carbon-13 chemical shifts of oleanene-type triterpenoids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;46:4163–4166. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yasukawa K., Akihisa T., Oinuma H., Kasahara Y., Kimura Y., Yamanouchi S., Kumaki K., Tamura T., Takido M. Inhibitory effect of di- and trihydroxy triterpenes from the flowers of compositae on 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced inflammation in mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1996;19:1329–1331. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yoshikawa K., Taninaka H., Kan Y., Arihara S. Antisweet natural products. X. Structures of sitakisoside I–V from Stephanotis lutchuensis Koidz. var. japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994;42:2023–2027. doi: 10.1248/cpb.42.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khong P.W., Lewis K.G. New triterpenoid extractives from Lemaireocereus chichipe. Aust. J. Chem. 1975;28:165–172. doi: 10.1071/CH9750165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoshikawa K., Mizutani A., Kan Y., Arihara S. Antisweet natural products. XII. Structures of sitakisosides XI–XX from Stephanotis lutchuensis Koidz. var. japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997;45:62–67. doi: 10.1248/cpb.45.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peng S.L., Zhu X.M., Wang M.K., Ding L.S. A Novel triterpenic acid from Gymnema sylvestre. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2005;16:223–224. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ye W.C., Zhang Q.W., Liu Xin, Che C.T., Zhao S.X. Oleanane saponins from Gymnema sylvestre. Phytochemistry. 2000;53:893–899. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Y., Feng Y., Wang X., Xu H. Isolation and identification of a new component from Gymnema sylvestre. Huaxi Yaoxue Zazhi. 2004;19:336–338. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhu X.M., Xie P., di Y.T., Peng S.L., Ding L.S., Wang M.K. Two new triterpenoid saponins from Gymnema sylvestre. J. Integ. Plant Biol. 2008;50:589–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ye W., Liu X., Zhang Q., Che C.T., Zhao S. Antisweet saponins from Gymnema sylvestre. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:232–235. doi: 10.1021/np0004451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yoshikawa K., Ogata H., Arihara S., Chang H.C., Wang R.R. Antisweet natural products. XIII. Structures of alternosides I-X from Gymnema alternifolium. Jen-Der. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998;46:1102–1107. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.1102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yoshikawa K., Takahashi K., Matsuchika K., Arihara S., Chang H.C., Wang J.D. Antisweet natural products. XIV. Structures of alternosides XI–XIX from Gymnema alternifolium. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999;47:1598–1603. doi: 10.1248/cpb.47.1598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang M.Q., Liu Y., Xie S.X., Xu T.H., Liu T.H., Xu Y.J., Xu D.M. A new triterpenoid saponin from Gymnema sylvestre. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2012;14:1186–1190. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2012.726517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim D.H., Han K.M., Chung I.S., Kim D.K., Kim S.H., Kwon B.M., Jeong T.S., Park M.H., Ahn E.M., Baek N.I. Triterpenoids from the flower of Campsis grandiflora K. Schum. as human AcyI-CoA: Cholesterol Acyltransferase inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005;2:550–556. doi: 10.1007/BF02977757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Diandian S., Min-Hsiung P., Qing-Li W., Chung-Heon P., Rodolfo J., Chi-Tang H., James E.S. LC-MS method for the simultaneous quantitation of the anti-inflammatory constituents in oregano (Origanum species) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:7119–7125. doi: 10.1021/jf100636h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Guo S., Duan J.A., Tang Y.P., Yang N.Y., Qian D.W., Su S.L., Shang E.X. Characterization of triterpenic acids in fruits of Ziziphus species by HPLC-ELSD-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:6285–6289. doi: 10.1021/jf101022p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seebacher W., Haslinger E., Rauchensteiner K., Jurenitsch J., Presser A., Weis R. Synthesis and haemolytic activity of randianin isomers. Monats. Chem. 1999;130:887–897. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhu Y.-Y., Qian L.-W., Zhang J., Liu J.-H., Yu B.-Y. New approaches to the structural modification of olean-type pentacylic triterpenes via microbial oxidation and glycosylation. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:4206–4211. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matsuda H., Li Y., Murakami T., Matsumura N., Yamahara J., Yoshikawa M. Antidiabetic principles of natural medicines. III. Structure-related inhibitory activity and action mode of oleanolic acid glycosides on hypoglycemic activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998;46:1399–1403. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chiozem D.D., Trinh-Van-Dufat H., Wansi J.D., Djama C.M., Fannang V.S., Seguin S., Tillequin F., Wandji J. New friedelane triterpenoids with antimicrobial activity from the stems of Drypetes paxii. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009;57:1119–1122. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xiaoan W., Hongbin S., Jun L., Keguang C., Pu Z., Liying Z., Jia H., Luyong Z., Peizhou N., Spyros E.Z., et al. Naturally occurring pentacyclic triterpenes as inhibitors of glycogen phosphorylase: Synthesis, structure-activity relationships, and x-ray crystallographic studies. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:3540–3554. doi: 10.1021/jm8000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rastrelli L., Aquino R., Abdo S., Proto M., De Simone F., de Tommasi N. Studies on the constituents of Amaranthus caudatus leaves: Isolation and structure elucidation of new triterpenoid saponins and ionol-derived glycosides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:1797–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang Y., Peng Y., Li L., Zhao L., Hua Y., Hu C., Song S. Studies on cytotoxic triterpene saponins from the leaves of Aralia elata. Food Chem. 2013;138:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mencherini T., Picerno P., Del Gaudio P., Festa M., Capasso A., Aquino R. Saponins and polyphenols from Fadogia ancylantha (Makoni tea) J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:247–251. doi: 10.1021/np900466x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Werner S., Nebojsa S., Robert W., Robert S., Olaf K. Spectral assignments and reference data. Complete assignments of 1H and 13C-NMR resonances of oleanolic acid, 18α-oleanolic acid, ursolic acid and their 11-oxo derivatives. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2003;41:636–648. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu X., Ye W., Xu D., Zhang Q., Che Z., Zhao S. Chemical study on triterpene and saponin from Gymnema sylvestre. Zhongguo Yaoke Daxue Xuebao. 1999;30:174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang X., Huo L., Liu L., Xu Z., Wang W. Chemical constituents from leaves of Gymnema sylvestre (I) Zhongcaoyao. 2011;42:866–869. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Toshihiro A., Scott G., Franzblau M.U., Hiroki O., Fangqiu Z., Ken Y., Takashi S., Yumiko K. Antitubercular activity of triterpenoids from asteraceae flowers. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;28:158–160. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ye W.-C., Liu X., Zhao S.-X., Che C.-T. Triterpenes from Gymnema sylvestre growing in china. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2001;29:1193–1195. doi: 10.1016/S0305-1978(01)00060-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Toshihiro A., Jun O., Jun K., Ken Y., Motohiko U., Sakae Y., Kunio O. Inhibitory effects of triterpenoids and sterols on human immunodeficiency Virus-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Lipids. 2001;36:507–512. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Motohiko U., Toshihiro A., Ken Y., Yoshimasa K., Yumiko K., Kazuo K., Tamotsu N., Michio T. Constituents of compositae plants. 2. Triterpene diols, triols, and their 3-O-fatty acid esters from edible chrysanthemum flower extract and their anti-inflammatory effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:3187–3197. doi: 10.1021/jf010164e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cespedes C.L., Salazar J.R., Martınez M., Aranda E. C24.1. Insect growth regulatory effects of some extracts and sterols from Myrtillocactus geometrizans (Cactaceae) against Spodoptera frugiperda and Tenebrio molitor. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2481–2493. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ye W., Dai Y., Cong X., Zhu X., Zhao S. Isolation of Novel Gymnemic Acid Derivatives from Gymnema sylvestre R. Br in Prevention or Treatment of Disorders Related to High Blood Sugar, High Blood Lipids, or Blood Clotting. WO 2000047594A1. PCT Int. Appl. 2000 Aug 17;

- 116.Mandal V., Dewanjee S., Mandal S.C. Role of modifier in microwave assisted extraction of oleanolic acid from Gymnema sylvestre: Application of green extraction technology for Botanicals. Nat. Prod. Comm. 2009;4:1047–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mandal V., Mandal S.C. Design and performance evaluation of a microwave based low carbon yielding extraction technique for naturally occurring bioactive triterpenoid: Oleanolic acid. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010;50:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2010.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hisashi M., Yuhao L., Toshiyuki M., Johji Y., And Masayuki Y. Structure-related inhibitory activity of oleanolic acid glycosides on gastric emptying in mice. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:323–327. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(98)00207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Davidyans E.S. Effect of triterpenoid glycosides on α- and β-amylase activity and total protein content in wheat seedlings. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2011;47:480–486. doi: 10.1134/S0003683811050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Maeda M., Iwashita T., Kurihara Y. Studies on taste modifiers. Purification and structure determination of gymnemic acids, antisweet active principle from Gymnema sylvestre leaves. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:1547–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)99515-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]