Abstract

Background

Liver disease (LD) prolongs mirtazapine half‐life in humans, but it is unknown if this occurs in cats with LD and healthy cats.

Hypothesis/Objectives

To determine pharmacokinetics of administered orally mirtazapine in vivo and in vitro (liver microsomes) in cats with LD and healthy cats.

Animals

Eleven LD and 11 age‐matched control cats.

Methods

Case‐control study. Serum was obtained 1 and 4 hours (22 cats) and 24 hours (14 cats) after oral administration of 1.88 mg mirtazapine. Mirtazapine concentrations were measured by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Drug exposure and half‐life were predicted using limited sampling modeling and estimated using noncompartmental methods. in vitro mirtazapine pharmacokinetics were assessed using liver microsomes from 3 LD cats and 4 cats without LD.

Results

There was a significant difference in time to maximum serum concentration between LD cats and control cats (median [range]: 4 [1‐4] hours versus 1 [1‐4] hours; P = .03). The calculated half‐life of LD cats was significantly prolonged compared to controls (median [range]: 13.8 [7.9‐61.4] hours versus 7.4 [6.7‐9.1] hours; P < .002). Mirtazapine half‐life was correlated with ALT (P = .002; r = .76), ALP (P < .0001; r = .89), and total bilirubin (P = .0008; r = .81). The rate of loss of mirtazapine was significantly different between microsomes of LD cats (–0.0022 min−1, CI: −0.0050 to 0.00054 min−1) and cats without LD (0.01849 min−1, CI: −0.025 to −0.012 min−1; P = .002).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Cats with LD might require less frequent administration of mirtazapine than normal cats.

Keywords: appetite stimulant, feline, hepatic, microsomes

Abbreviations

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AMC

age‐matched control

- AUC

area under the curve

- CL

clearance

- F

bioavailability

- HB

homogenization buffer

- Kel

estimation of elimination rate

- LC/MS/MS

liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantitation

- QA/QC

quality assurance, quality control

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- T1/2

half‐life

- Vd

volume of distribution

1. INTRODUCTION

Mirtazapine is an appetite stimulant that has become a common treatment for supportive care in sick cats.1 In humans, several factors can affect the metabolism of mirtazapine, including age, renal and hepatic impairment.2 In cats, renal disease decreases clearance, but the effect of liver disease (LD) is unknown.3 Mirtazapine is primarily metabolized by the liver, initially by demethylation and oxidation, and then by conjugation to glucuronic acid.2 Hepatic impairment can cause as much as a 33% decrease in clearance and a 39% increase in the half‐life of mirtazapine in humans, thus in patients with LD the drug is administered less frequently.2 The purpose of this study was to compare the pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine administered PO in cats with LD compared with age matched healthy control cats using a limited sampling strategy based on the pharmacokinetic modeling in healthy cats.4 The secondary purpose was to use liver microsomes obtained from cats with and without LD to compare the pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine in vitro. Our hypothesis was that cats with LD would have prolonged half‐life of mirtazapine compared to cats without LD.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. In vivo studies

2.1.1. Cats

Cats were categorized into one of the following groups: healthy age‐matched controls and cats with LD. Healthy age‐matched control cats were defined as having a normal CBC, serum biochemistry (creatinine ≤ 1.6 mg/dL), urinalysis (USG > 1.035) and total T4 level. Exclusion criteria for age‐matched control cats included other systemic illness, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, hyperthyroidism, cancer, LD, or heart disease. Cats with LD were defined based on increased activity of liver‐derived alanine aminotransferase (ALT) enzyme (> 200 UI/L) or total bilirubin (>1 mg/dL) without clinical suspicion of prehepatic or posthepatic hyperbilirubinemia. Exclusion criteria for LD cats included hyperthyroidism or chronic kidney disease (defined as creatinine > 1.6 mg/dL and USG < 1.035). Age matching was performed by enrolling healthy control cats that were within 1 year of the age of an enrolled LD cat. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Colorado State University and all owners reviewed and signed consent forms before enrolling their cat in the study.

2.1.2. Drug preparation

Commercially available generic 15 mg mirtazapine tablets (Amerisourcebergen, Chesterbrook, Pennsylvania) were compounded into 1.88 mg capsule doses by the pharmacy at the Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital according to the Professional Compounding Centers of America protocol as previously described.4 Mirtazapine capsules were compounded within 1 month of use and stored at room temperature.

2.1.3. Dosing and sampling

Eleven cats with LD and 11 age‐matched control cats received 1.88 mg mirtazapine once PO. Serum was obtained at 1, 4, and, when possible, 24 hours after drug administration. Sampling time points were determined with limited sampling modeling (described below) based on pharmacokinetic assessment of mirtazapine in young and old normal cats.3, 4 Serum was collected via centrifugation immediately after clot formation and frozen in aliquots at −80°C until analysis.

2.1.4. Mirtazapine sample extraction and evaluation

Mirtazapine was measured using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) by the Pharmacology Core at Colorado State University using a validated LC/MS/MS based assay for the analysis of mirtazapine in feline serum.4 Assay performance for each batch was assessed using at least 10% quality assurance, quality control (QA/QC) samples dispersed among unknown samples at low (1 ng/mL), mid (10 ng/mL), and high (100 ng/mL) ranges of the standard curve (0.5–500 ng/mL) with batches failing if >25% of the QA/QC samples were outside of the accepted level of 85% accuracy. Accuracy of QA/QC samples among the batches analyzed for this study ranged from 94.5 ± 4.6 to 92.2 ± 6.8%. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for this assay was based on the level of detection with >85% accuracy and a coefficient of variation (%) <15%, and was determined to be 0.5 ng/mL. Assay performance was linear to >500 ng/mL, but 500 ng/mL was used as the upper limit of the assay as utilized because of a lack of samples exceeding this concentration.

2.1.5. Limited sampling modeling and pharmacokinetic analysis

The mirtazapine serum concentration versus time data for 10 healthy cats administered a fixed oral 1.88 mg dose in two earlier studies was used for calculation of drug exposure (AUC0–24 h) by noncompartmental methods.3, 4 The resulting AUC values were found to be normally distributed by Q–Q plot and subsequently analyzed as a response to time point mirtazapine concentration values as predictors by best subset multiple linear regression. This method evaluates all single time points as well as all possible combinations of multiple time points as predictors of the outcome (AUC0–24 h). Data used in the best subset linear regression analysis were those time points corresponding to postadministration samples and were designated as 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 corresponding to the number of hours the samples were collected after administration. The combinations of statistical correlation, number of samples required, and length of time required after administration were all considered in choosing the optimal limited sampling scheme. All regression analysis was carried out using Minitab v 15.1.1.0 software (Minitab, State College, Pennsylvania). The results of best subset multiple linear regression revealed that using 2 points as predictors of AUC0‐infinity (1 and 4 hours) could provide the best combination of statistical correlation (r 2 = 0.989) while minimizing sample number and time postadministration. The final model using the identified time points is described by the equation

where C 1 hour and C 4 hours represent the serum concentrations at 1 and 4 hours, respectively, after oral administration. This equation was used to estimate AUC in study samples.

A 24 hours time point was included when possible for the estimation of elimination rate (K el), which was calculated with the 4 and 24 hours time points using the equation:

Half‐life was then calculated using the equation:

The 24 hours time point was chosen to provide a more accurate estimation of elimination while still maintaining serum concentrations that are above the LLOQ of the analytical assay. C max was reported as the highest measured serum concentration (either 1 or 4 hours) and T max was reported as the time point corresponding to the highest measured serum concentration.

2.1.6. Statistical analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were compared between the 2 groups using repeated Mann Whitney test in Prism software (Prism 5; GraphPad, La Jolla, California). Parameters compared included AUC, C max (maximum serum concentration), and T max (time to maximum serum concentration), and in the cats where a 24 hours sample was obtained, half‐life. Mann Whitney test was also used to compare, age, mg/kg dose, serum ALT activity, alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP), total bilirubin, and albumin concentrations between groups. Spearman rank test was used to assess correlation between ALT, ALP, total bilirubin, albumin, and half‐life. For all analyses, a P‐value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

2.2. In vitro studies

2.2.1. Collection of liver microsomes

Liver samples for microsome isolation were collected at necropsy within 30 minutes of euthanasia from 3 LD cats (hepatic lipidosis) and 4 cats with normal CBC, serum biochemistry and urinalysis. Euthanasia was not performed for the purpose of the study. Age matching was not possible in the in vitro study. One LD cat from which microsomes were collected had also been enrolled in the in vivo study, but had not received mirtazapine for more than a week before humane euthanasia (a feeding tube was in place). Samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until microsome isolation.

2.2.2. Liver microsome preparation

Microsomes from liver pieces were prepared by a differential centrifugation method. All steps were carried out at 4°C or on ice. Liver pieces were homogenized in buffer (HB: 100 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA) in a dounce homogenizer at a 100 mg‐liver‐weight/mL‐HB ratio. Homogenates were subjected to the following differential centrifugation scheme: 800g for 10 minutes, 7000g for 10 minutes, 18 000g for 5 minutes, and 100 000g for 60 minutes. After each spin, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and the pellet was discarded except after the final spin. The pellet after the final spin, which contains microsomes, was kept and resuspended gently in a small volume (100–400 μL) of HB and stored at −80°C. A small aliquot was taken for protein concentration determination by bicinchoninic acid assay. The protein content of the samples was adjusted after measurement to 1.5 mg/mL microsomal protein. Microsome aliquots were thawed on ice when needed and aliquots were not used more than three freeze/thaw cycles.

2.2.3. Liver microsome incubations

Liver microsomes were incubated with mirtazapine for a total time of 80 minutes, and loss of mirtazapine was determined. Incubations were performed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (44 mM KH2PO4, 56 mM K2HPO4), adjusted to pH 7.43 with 1.0 M NaOH. Reaction master mixes were prepared with a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) regenerating system (Gentest NADPH Regenerating System, Corning, NY) which facilitates stability of microsomes for up to 2 hours. The amount of regenerating system ensured a roughly constant concentration of NAPDH at 1.5 mM. Reaction master mixes were preincubated at 37°C for 5 minutes. Metabolism reactions were initiated by the addition of 100 ng/mL mirtazapine and incubated at 37°C. Time points were taken at 0, 20, 40, 60, and 80 minutes. At each time point, 100 μL of reaction mix was removed and mixed 1 : 1 with acetonitrile. Samples were vortexed and stored at −80°C until ready for analysis.

After incubation, samples were processed for analysis by LC/MS/MS using the previously validated method for mirtazapine analysis in feline serum.4 Samples were thawed, internal standard (trazodone 25 ng/mL) was spiked into each reaction, and then samples were spun at 18 000g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and put into mass spectrometry vials for analysis. Mirtazapine was quantified via multiple reaction monitoring, and by integration of the chromatographic peaks associated with the analyte. Concentrations were based on the ratio of mirtazapine : internal standard using Analyst (AB Sciex) software. Standards and QCs were prepared in microsomes similar to incubation reactions to account for any matrix effects in the samples.

2.2.4. Statistical analysis

To calculate the in vitro half‐life of mirtazapine, the fraction mirtazapine remaining in the incubation samples was converted to percentage remaining and natural log transformed before least squares (ordinary) fit nonlinear regression (straight line). A repeated measures two‐way ANOVA was used to compare the in vitro k el (slope of the line in least squares nonlinear regression) of mirtazapine between LD cats and non‐LD cats. Calculation of the in vitro half‐life was performed by dividing 0.693 by the in vitro k el : t 1/2 = 0.693/k el.

The apparent intrinsic hepatic clearance (CLint,app) of mirtazapine was then calculated using the in vitro half‐life as follows:

CLint,app = (0.693/in vitro t 1/2)

(incubation volume/mg of microsomal protein)

(mg microsomal protein/gram of liver)

(grams of liver/kg body weight)11

Values for mg of microsomal protein per gram of liver (21.3 mg) and grams of liver per kg of body weight (24.6 g) for cats were taken from previously published literature.5, 6

3. RESULTS

3.1. In vivo studies

The average age of LD cats was 8.8 +/– 4.2 years (range 2–15 years). There were 5 spayed female cats and 6 castrated male cats. The average age of age‐matched control cats was 8.3 +/– 3.9 years (range 2–13 years). There were 8 spayed female cats and 3 castrated male cats. There was no significant difference in age between groups (P = .66). Values for serum ALT activity, serum ALP activity, serum total bilirubin concentration, serum albumin concentration, and dose of mirtazapine (mg/kg) for both groups are presented in Table 1. There was a statistically significant elevation in serum ALT activity (P < .0001), serum ALP activity (P < .0002), and serum total bilirubin concentration (P < .0001) in LD cats when compared to age‐matched control cats. All cats tolerated oral administration of mirtazapine. There was no statistically significant difference noted in the dose of mirtazapine administered between LD cats and age‐matched control cats (0.43 +/– 0.1 versus 0.47 +/– 0.1 mg/kg; P = .53). No adverse effects to the mirtazapine were observed or reported during this study.

Table 1.

Median and range clinicopathologic variables and mirtazapine pharmacokinetic parameters of cats with LD and healthy age matched control cats after cats received 1.88 mg mirtazapine PO once

| Liver Group (n = 11) | Age‐Matched Control (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| Dose mg/kg | 0.45 (0.22–0.58) | 0.48 (0.28–0.62) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 407 (138–1690) | 45 (30–72) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 233 (24–454) | 29 (8–50) |

| T Bili (mg/dL) | 4.3 (0.1–21.1) | 0 (0‐0.1) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 (2.8‐3.9) | 3.7 (3.2–3.9) |

| C max (ng/mL) | 40.1 (26–87.3) | 49.1 (32.2–80.2) |

| T max (hours) | 4 (1–4) | 1 (1–4) |

| AUC (ng/mL•h) | 382 (215–1075) | 440 (277–944) |

| Half‐lifea | 13.8 (7.9–61.4) | 7.4 (6.7–9.1) |

n = 7 in each group for half‐life calculation.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AUC, area under the curve (drug exposure); C max, maximum serum concentration; T bili, total bilirubin; T max, time to maximum serum concentration.

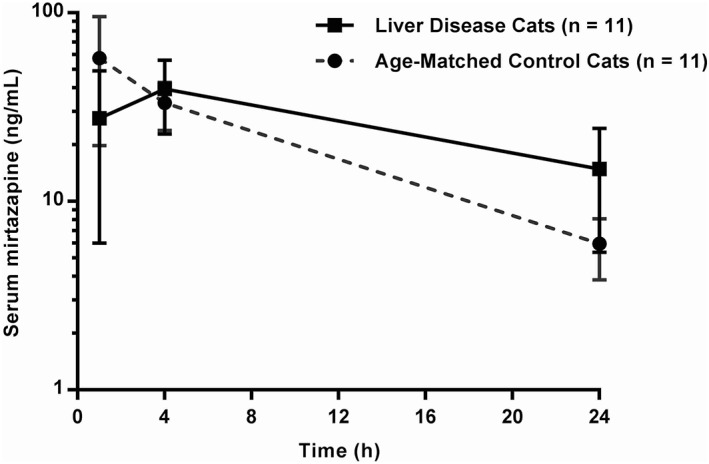

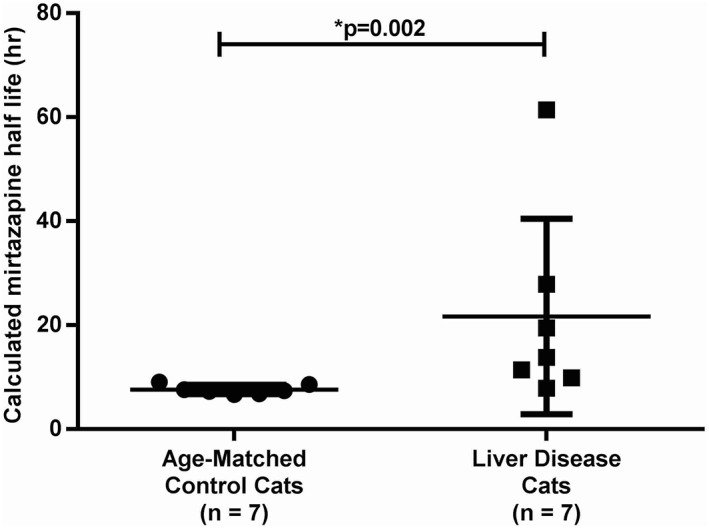

The pharmacokinetic parameters for LD cats and age‐matched control cats are summarized in Table 1 and the serum mirtazapine concentration‐time graph is depicted in Figure 1. There was a statistically significant difference in T max between LD cats and age‐matched control cats (P = .03). AUC was not significantly different between the two groups; however, the calculated half‐life of LD cats was significantly increased (P < .002) compared with age‐matched control cats (Figure 2). There was a correlation between serum ALT activity (P = .002; r = .76), serum ALP activity (P < .0001; r = .89), and serum total bilirubin concentration (P = .0008; r = .81) when compared with the serum half‐life of mirtazapine.

Figure 1.

Serum concentration‐time profile for 1.88 mg mirtazapine administered PO once to cats with LD (n = 11) and age‐matched control cats (n = 11)

Figure 2.

When 1.88 mg mirtazapine was administered once PO to cats with LD and age‐matched control cats without LD, the calculated half‐life of LD cats (n = 7) was significantly increased compared with age‐matched control cats (n = 7; P < .002)

3.2. In vitro studies

The average age of LD cats from which microsomes were collected was 3 +/– 1.5 years (range 2–5 years). There was 1 spayed female cat and 2 castrated male cats. The average age of cats without LD from which microsomes were collected was 6.1 +/– 3.2 years (range 2.5–10 years). There were 2 spayed female cats and 2 castrated male cats. Values for serum ALT activity, serum ALP activity, serum total bilirubin concentration, and serum albumin concentration for cats from which microsomes were collected are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Median and range clinicopathologic variables of cats with and without LD from which liver microsomes were collected

| LD Group (n = 3) | Non‐LD Group (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 469 (137–693) | 63 (19–76) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 159 (112–230) | 52 (50–68) |

| T Bili (mg/dL) | 8.1 (0.1–10.5) | 0.1 (0–0.1) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.5 (1.9–3.9) | 3.3 (2.0–3.5) |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; T bili, total bilirubin.

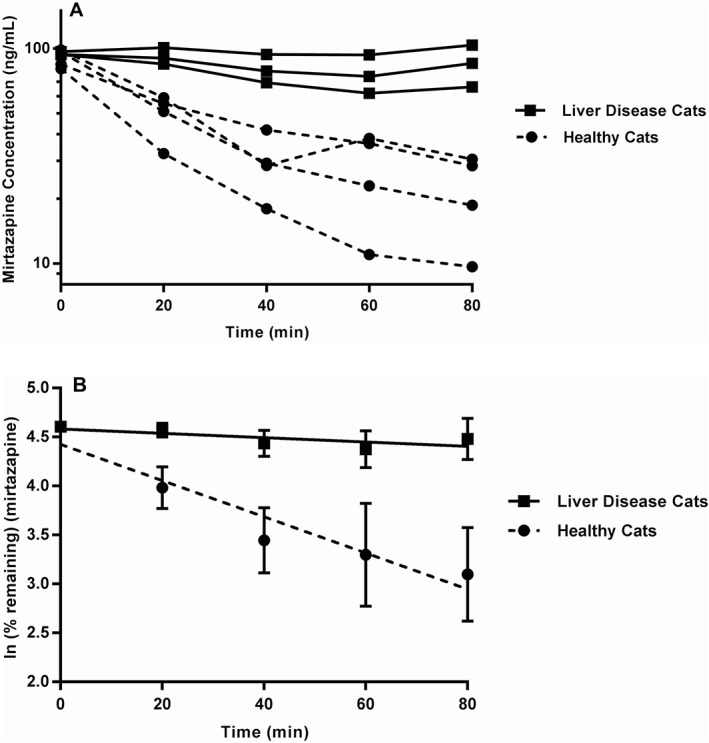

When liver microsomes from cats without and without LD were incubated with mirtazapine, there was a significant difference in the slope of the line representing the rate of loss (k el) of mirtazapine between LD cats (–0.0022 min−1, CI: −0.0050 to 0.00054 min−1) and cats without LD (0.01849 min−1, CI: −0.025 to −0.012 min−1; P = .002; Figure 3). When in vitro half‐life was calculated using the slope of the regression line from both groups, microsomes from cats with LD had an in vitro half‐life of 313.6 versus 37.5 minutes for microsomes from cats without LD representing a >8‐fold reduction in the metabolism of mirtazapine because of LD. The apparent intrinsic clearance of mirtazapine for LD cats was 0.77 versus 6.5 mL/min/kg for cats without LD representing a >8‐fold reduction in the presence of LD.

Figure 3.

Mirtazapine metabolism in liver microsomes from cats with and without LD. A, Measured mirtazapine concentrations at various time points during in vitro metabolism. B, Nonlinear regression of ln‐transformed percent remaining values to calculate the in vitro elimination rate (k). There is a statistically significant difference between the slopes of the regression lines representing the in vitro elimination rate of mirtazapine (ANOVA; P = .002)

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to assess the pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine in LD cats in comparison to healthy age‐matched control cats using both a limited sampling method in vivo and liver microsome assays in vitro. In cats where a limited sampling method was used to predict pharmacokinetics, the calculated half‐life was significantly prolonged in LD cats compared with healthy age‐matched control cats. Additionally, LD cats had significantly longer time to maximum serum concentration than did age‐matched control cats. When mirtazapine was incubated with liver microsomes from LD cats and cats without LD, metabolism of mirtazapine in the microsomes of LD cats was prolonged in comparison to cats without LD.

Overall, the findings in our study are consistent with pharmacokinetic changes in humans as a result of LD. In humans, hepatic impairment results in a 33% decrease in mirtazapine clearance and a 39% prolongation in the half‐life of mirtazapine (mean 44 +/– 4.8 hours in LD versus 31.6 +/– 7.5 hours in healthy age‐matched controls).2, 7 In our study in LD cats, a 185% prolongation in the half‐life of mirtazapine was seen (mean 21.7 +/– 18.8 hours versus 7.6 +/– 0.9 hours in healthy age‐matched controls). Time to maximum serum concentration is similar between humans with LD and healthy age‐matched controls, unlike in our study where LD cats had prolonged time to maximum serum concentration. The reason for this is unknown, although factors associated with LD such as altered gastrointestinal motility and decreased intestinal perfusion secondary to portal hypertension might be involved. A limitation to the present study is that only 2 time points were evaluable for these parameters (1 or 4 hours) and thus might not accurately represent the true values. The time points were chosen based on an ability to accurately predict the overall exposure (AUC0‐infinity) with minimal sampling and thus there was a tradeoff in accurate prediction of true C max and T max. However, the T max predicted for healthy control cats in this study does closely match the T max measured in healthy controls from previous studies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative pharmacokinetic parameters of single dose oral 1.88 mg mirtazapine in cats of difference ages and disease states3, 4

| Healthy Young Cats4 | Healthy Geriatric Cats (Age‐match to CKD)3 | CKD Cats3 | Healthy Cats (Age‐match to Liver) | Cats with LD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirtazapine PO Administration (capsule formulation; 0.44 mg/kg) | Mirtazapine PO Administration (capsule formulation; 0.44 mg/kg) | Mirtazapine PO Administration (capsule formulation; 0.51 mg/kg) | Mirtazapine PO Administration (capsule formulation; 0.47 mg/kg) | Mirtazapine PO Administration (capsule formulation; 0.43 mg/kg) | |

| PK Parameter | N = 4 | N = 6 | N = 6 | N = 11 | N = 11 |

| T max (h) | 1.0 (1.0–4) | 1.0 (1.0–4) | 1.0 (0.5‐1.5) | 1.0 (1.0–4) | 4.0 (1.0–4) |

| C max (ng/mL) | 73.1 (45.5) | 79.6 (21.7) | 110.6 (30.8) | 54.0 +/– 15.8 | 43.9 +/– 18.8 |

| AUC0‐∞ (ng*h/mL) | 407.4 (102.1) | 1320.4 (236.0) | 1701.2 (301.3) | 470 +/– 182 | 434 +/– 230 |

| Half life (h) | 10.3 (2.3) | 12.1 (1.1) | 15.2 (4.2) | 7.6 +/– 0.9 | 21.7 +/– 18.8 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve (drug exposure); C max, maximum serum concentration; CKD, chronic kidney disease; PO, oral; T max, time to maximum serum concentration.

Serum PK parameter values are reported as mean (SD), except for T max, which is reported as median (min–max).

An interesting finding in this study is that the in vitro experiments with liver microsomes recapitulated in vivo pharmacokinetic findings, confirming that the increased half‐life measured in LD cats can be explained, at least in part, by a reduction in the intrinsic hepatic clearance of mirtazapine in these cats. Microsomes have the potential as a valuable tool to explore factors that affect drug metabolism as well as potential drug interactions. Important future directions to better inform feline pharmacology would be exploration and identification of the specific cytochrome P450 activities that are dysfunctional in LD, and whether this varies depending on the type of LD. This is particularly important as in humans, alterations in cytochrome P450 activities have been shown to be non‐uniform and variable depending on disease type and severity.8

Given the results of this and previous studies on mirtazapine in cats, the age and disease status of cats should be taken into account when prescribing mirtazapine. A comparison of pharmacokinetic data for mirtazapine across age and disease in cats is presented in Table 3. In a previous study, the mean half‐life of mirtazapine was determined to be nine hours in healthy cats, and once daily 1.88 mg dosing did not result in significant drug accumulation.4 In another pharmacokinetic study evaluating mirtazapine in cats with chronic kidney disease, it was determined that kidney disease can prolong the clearance and half‐life of mirtazapine.3 The mean half‐life of mirtazapine was determined to be fifteen hours in cats with kidney disease, and based on the results of this study, decreased dosing frequency (ie, every 48 hours) of mirtazapine in cats with kidney disease has been recommended. In our study, because of the significant effects of kidney disease on mirtazapine pharmacokinetics, cats with concurrent kidney disease were excluded to eliminate this variable from the analysis.

The study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting results. The measured variables (ALT, ALP, total bilirubin) might not be the best evaluation of liver function and fasting and postprandial bile acid levels were not evaluated in the cats with LD in this study. However, currently no gold standard of liver function exists to inform adjustment of dose regimens in humans with liver dysfunction.8 Diagnostic imaging of the liver, fine needle aspirate or biopsy was also not performed in all of the cats in the LD so further conclusions cannot be drawn regarding what type of LD was present or the relationship to mirtazapine metabolism.

In our study, blood work was not re‐evaluated after administration of mirtazapine as only 1 dose was administered. In humans, mirtazapine rarely causes an idiosyncratic increase in ALT that resolves with discontinuation of the drug.9 In a pharmacodynamic study of mirtazapine in cats with chronic kidney disease, one cat developed an increased ALT activity with no associated clinical signs that resolved with discontinuation of the drug.10 It is unknown if there is increased risk of idiosyncratic liver enzymes elevation if values are already increased at the time of mirtazapine administration. A challenge of enrollment was that owners were commonly reluctant to return their cat to the clinic for the 24 hours blood sample, thus the calculation of predicted half life, which required a 24 hours time point, was based on a subset of 7 cats with LD and the concomitant 7 age‐matched control cats.

An additional limitation of the study was that it was not feasible to collect liver microsomes from age‐matched non‐LD cats, and this may have introduced some potential bias. In an attempt to minimize this bias, liver microsomes were collected from non‐LD cats who were a range of ages. It is also noted that the method used for evaluation of in vitro metabolism does not account for any drug clearance via direct phase II metabolic reactions and thus the possibility of alterations in direct conjugation of mirtazapine cannot be assessed in our study.

In conclusion, when 1.88 mg of mirtazapine was administered once PO to LD cats and age‐matched control cats, cats with LD displayed prolonged time to maximum serum concentration and prolonged calculated half‐life. This observation was further supported in vitro by the demonstration of delayed metabolism of mirtazapine by liver microsomes from LD cats. These findings should be taken into consideration when prescribing mirtazapine to feline patients with LD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Dr Quimby is a consultant, advisory board member and key opinion leader speaker for Kindred Bio, a company with a financial interest in mirtazapine.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label antimicrobial use.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) DECLARATION

The study was reviewed and approved by the IACUC at Colorado State University.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the doctors and staff of Just Cats Veterinary Clinic, Stamford, CT for assistance with enrollment. This work was performed at Colorado State University. This study was funded by a grant from the Angelo Fund for Feline Therapeutics at Colorado State University and supported, in part, by the University of Colorado Cancer Center Shared Resource Support Grant (P30CA046934) supporting the Pharmacology Shared Resource. This work was completed at the Gastrointestinal Laboratory, Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas.

Fitzpatrick RL, Quimby JM, Benson KK, et al. In vivo and in vitro assessment of mirtazapine pharmacokinetics in cats with liver disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:1951–1957. 10.1111/jvim.15237

Present address Rikki L. Fitzpatrick, VCA Advanced Animal Care, Indianapolis, IN 46038 Luke A. Wittenburg, Dr Wittenburg, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, Davis, CA 95616

Funding information Angelo Fund, Colorado State University; University of Colorado Cancer Center, Grant/Award Number: P30CA046934

REFERENCES

- 1. Agnew W, Korman R. Pharmacological appetite stimulation: rational choices in the inappetent cat. JFeline Med Surg. 2014;16:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Timmer CJ, Sitsen JM, Delbressine LP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;38:461–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quimby JM, Gustafson DL, Lunn KF. The pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine in cats with chronic kidney disease and in age‐matched control cats. JVet Intern Med. 2011;25:985–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Quimby JM, Gustafson DL, Samber BJ, et al. Studies on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of mirtazapine in healthy young cats. JVet Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gregus Z, Watkins JB, Thompson TN, et al. Hepatic phase I and phase II biotransformations in quail and trout: Comparison to other species commonly used in toxicity testing. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1983;67:430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Latimer HB. Variability in body and organ weights in the newborn dog and cat compared with that in the adult. Anat Rec. 1967;157:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murdoch DL, Ashgar J, Ankier SI. Influence of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of single doses of mirtazapine in elderly subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35:76. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verbeeck RK. Pharmacokinetics and dosage adjustment in patients with hepatic dysfunction. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:1147–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adetunji B, Basil B, Mathews M, et al. Mirtazapine‐associated dose‐dependent and asymptomatic elevation of hepatic enzymes. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quimby JM, Lunn KF. Mirtazapine as an appetite stimulant and anti‐emetic in cats with chronic kidney disease: A masked placebo‐controlled crossover clinical trial. Vet J. 2013;197:651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu C, Li P, Gallegos R, et al. Comparison of intrinsic clearance in liver microsomes and hepatocytes from rats and humans: Evaluation of free fraction and uptake in hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1600–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]