Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common illness that has been associated with filaggrin gene (FLG) loss of function (LoF) variation. In African-Americans, a group that commonly has AD and has not been well studied, FLG LoF variation is rarely found. The objective was to use massively parallel sequencing to evaluate FLG LoF variation in children of African ancestry to evaluate the association between FLG LoF variation and AD and AD persistence. We studied 262 African American children with AD. Nine unique FLG exon 3 LoF variants were identified for an overall minor variant frequency (MVF) of 6.30% (95% CI: 4.37, 8.73). The most common variants were p.R501X (1.72% (0.79, 3.24), p.S3316X (1.34% (0.54, 2.73), and p.R826X (0.95% (0.31, 2.21)). Over an average follow up of 96.4 (95% CI: 92.0, 100.8) months, African-American children with FLG LoF were less likely to be symptom free (odds ratio: 0.36 (0.14, 0.89) p=0.027) as compared to a FLG wildtype child. In contrast to previous reports, uncommon FLG LoF variants in African-American children exist and are associated with AD and more persistent AD. In contrast to Europeans, no FLG LoF variants predominate in African-American children. Properly determining FLG LoF status requires advanced sequencing techniques.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema or atopic eczema, is a common, chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by periods of acute flares. It is often a lifelong ailment, which frequently manifests as itchy, red patches on the flexural areas of the elbows and knees.(Abuabara et al., 2017; Margolis et al. 2014b) The prevalence of AD is increasing worldwide and it is a major public health burden. In the US, AD affects roughly 5–20% of all children and adults of all races and ethnicities, with a total cost of more than 4.2 billion dollars per year. (Abuabara et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2017; Shaw et al. 2011) Complex genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors are thought to be responsible for the development of AD, including the disruption of the normally protective skin barrier. The most common gene associated with susceptibility to AD is filaggrin (FLG) which is located within the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) on chromosome 1q21. FLG encodes the protein filaggrin (filament-aggregating protein), an important epidermal barrier protein involved in maintaining an intact skin barrier.(Brown and McLean, 2012; Margolis et al., 2012; Palmer et al., 2006; Sandilands et al., 2007)

FLG is transcribed as a large precursor protein, profilaggrin. In the granular cell layer of the epidermis, dephosphorylation and proteolysis of profilaggrin yields filaggrin, which binds to keratin intermediate filaments and subsequently assembles a keratin matrix.(Brown and McLean, 2012) This matrix acts as a protein scaffold and together with bound proteins and lipids forms the topmost skin layer, the stratum corneum.(Brown and McLean, 2012) Loss-of-function (LoF) mutations in exon 3 of the FLG gene are associated with markedly diminished or absent FLG protein production presumably due to nonsense mediated decay and AD of earlier onset, increased severity, and/or increased persistence.(Brown and McLean, 2012; Margolis et al., 2012)

Over 20 FLG LoF variants in exon 3 have been associated with susceptibility to AD. More than 300 FLG LoF variants have been identified in sequencing data available in the gnomAD browser, an international aggregate database of exome and genome sequencing data.(Lek et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017) As evidenced by several studies, FLG LoF mutations vary by race.(Brown and McLean, 2012; Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2014a; Palmer et al., 2006; Sandilands et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2017) Four FLG LoF mutations have been consistently associated with AD in patients of European ancestry (p.R501X, c.2282del4, p.S3247X, p.R2447X) and many studies focus primarily on these variants.(Brown and McLean, 2012; Margolis et al., 2012; Palmer et al., 2006; Sandilands et al., 2007) However, studies of patients of East Asian ancestry demonstrate larger numbers of variants, with c.3321delA the only variant associated with AD and found in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese populations.(Akiyama et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2017) Several recent studies, using a variety of genotyping and sequencing techniques, were not able to detect FLG LoF mutations in individuals of African ancestry with AD at frequencies noted in European and Asian populations.(Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2014a; Policari et al., 2014; Taylan et al., 2015; Thawer-Esmail et al., 2014; Winge et al., 2011) The goal of this study was to use massively parallel sequencing (MPS) to evaluate FLG LoF variation in children of African ancestry to comprehensively evaluate the association between FLG LoF variation and AD and AD persistence.

RESULTS

Of the 370 African American subjects PEER subjects who provided DNA, 262 had sufficient DNA for this study. The mean age of onset of AD was 2.09 (sd: 2.88) years of age and 58.8% were female. Seasonal allergies were noted in 66.7% and 55.7% had a history of asthma. The PEER study is an ongoing study. At the time of this analysis, 133 (50.7%) of the African American children had completed 10 years of follow-up. The African American cohort was followed on average for 96.4 (95% CI: 92.0, 100.8) months (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Participant demographics.

| African-American | White | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 262 | 133 |

| Mean age at enrollment (sd) | 7.66 (0.24) | 6.94(0.30) |

| Mean age of AD onset (sd) | 2.09 (2.88) | 1.46 (1.86) |

| Gender: female (%) | 160 (61.0 %) | 70 (52.6%) |

| Asthma (%) | 146 (55.8%) | 74 (55.8%) |

| Seasonal Allergies (%) | 175 (66.8%) | 96 (72.6%) |

| Mean observation time months (95% CI) | 96.4 (92.0, 100.8) | 113.5 (109.1, 117.8) |

The inter-rater agreement for the four “European” variants (p.R501X, c.2282del4 (p.S761fs), p.R2447X, and p.S3247X) was assessed between the MPS approach and previous data that used traditional sequencing approaches (Table 2). The Kappa score was in the “almost perfect” range (≥0.81) for the p.R501X, c.2282del4 (p.S761fs), and p.R2447X variants (Table 2).(Landis and Koch, 1977) The reliability for p.S3247X was in the “substantial” range (0.61–0.80).(Landis and Koch, 1977) The MPS approach did not identify three individuals heterozygous for p.S3247X noted by the TaqMan assay.

Table 2:

Inter-rater agreement between the previous approach that used TaqMan assays (Margolis et al., 2012) and the current approach that used targeted next generation sequencing. SD = standard deviation, NR=not reported (no outcomes for African Americans).

| Allele | African American N=262 |

White N=133 |

All subjects N=353 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement (%) | Kappa (SD) | Agreement (%) | Kappa (SD) | Agreement (%) | Kappa (SD) | |

| p.R501X | 99.10% | 0.86 (0.06) | 98.48% | 0.95 (0.08) | 98.87% | 0.93 (0.05) |

| p.2447X | 99.55% | 0.85 (0.07) | 100.00% | 1.00 (0.09) | 99.72% | 0.95 (0.05) |

| p.S3247X | 98.67% | 0.72 (0.06) | 100.00% | 1.00 (0.09) | 99.16% | 0.80 (0.05) |

| p.S761fs (c.2282del4) |

NR | NR | 97.74% | 0.90 (0.08) |

99.15% | 0.91 (0.05) |

| Composite based on variants listed above | 98.64% | 0.88 (0.06) | 96.21% | 0.92 (0.07) | 97.73% | 0.91 (0.04) |

In the African American children, the overall prevalence of any FLG LoF variant was 12.21%. Nine different FLG LoF variants were identified in 32 of the 262 children. The overall MVF of the FLG LoF composite was 6.30% (4.37, 8.73). Each individual variant had a minor variant frequency (MVF) of less than 2.0%. The three most common variants were p.R501X (MVF: 1.72% (0.79, 3.24), p.S3316X (1.34% (0.54, 2.73), and p.R826X (0.95% (0.31, 2.21)). MVF for the FLG LoF were compared between our sample population and the African population described in gnomAD (release date 10/3/2017 r2.0.12). All but one variant (p.H440fs) was reported in gnomAD. All variants among those of African ancestry with AD were more frequent in our cohort than in the reference gnomAD cohort (Table 3). Three of the variants (p.R501X, p.R2447X, and p.S3247X) were significantly more frequent than the gnomAD reference (Table 3). As expected, because of the reliability between the assays used, the MVF for p.R501X, p.R2447X, c.S761fs, and p.S3247 for white children were very similar to our previous report; therefore they were not reported.(Margolis et al., 2012) Four variants, all uncommon, that were not previously reported by us in the white cohort and not found in the African American children were noted; c.G1787fs, c.P685fs, c.T2496fs, and p.R1474X.(Margolis et al., 2012)

Table 3:

Descriptive information for FLG LoF stop gain variants noted in African American subjects in our study and comparisons with the African Ancestry cohort from gnomAD. All minor variant frequency (MVF) presented as percent with 95% CI and prevalence per hundred. All p-values estimated using two sided Fisher exact test. NR- Not Reported in gnomAD. *p.S3316X maps to p.S3640X using a 12 repeat FLG gene reference, which is not gnomAD standard.

| SNP | Chromosome Start |

MVF (genomes=524) | Variants noted | gnomAD |

Variants/ Genomes |

RSID | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.R501X | 152285861 | 1.72(0.79,3.24) | 9 | 0.43(0.35,0.52) P=0.001 |

103 23984 |

61816761 | c.1501C>T |

| p.R826X | 152284886 | 0.95(0.31,2.21) | 5 | 0.77(0.66,0.89) P=0.607 |

184 23970 |

115746363 | c.C2476C>T |

| p.R2447X | 152280023 | 0.76(0.21,1.94) | 4 | 0.05(0.23,0.09) P<0.0001 |

13 23962 |

138726443 | c.7339C>T |

| p.Q3818X | 152275910 | 0.19(0.00,1.06) | 1 | 0.04(0.02,0.08) P=0.228 |

11 24028 |

148606936 | c.11452C>T |

| p.Q570X | 152285654 | 0.19(0.00,1.06) | 1 | 0.02(0.000.05) P=0.126 |

3 15304 |

192402912 | c.1708C>T |

| p.R3409X | 152277137 | 0.19(0.00,1.06) | 1 | 0.01(0.00,0.04) P=0.096 |

2 15300 |

201356558 | c.10225C>T |

| p.S3247X | 152277622 | 0.76(0.21,1.94) | 4 | 0.05(0.02,0.09) P<0.0001 |

12 24008 |

150597413 | c.9740C>A |

| p.S3316X* | 152277415 | 1.34(0.54,2.73) | 7 | 0.78(0.67,0.90) P=0.132 |

187 24000 |

149484917 | c.9947C>A |

| p.H440fs | 152286044 | 0.19(0.00,1.06) |

1 | NR | NR | NR | c.1318delC |

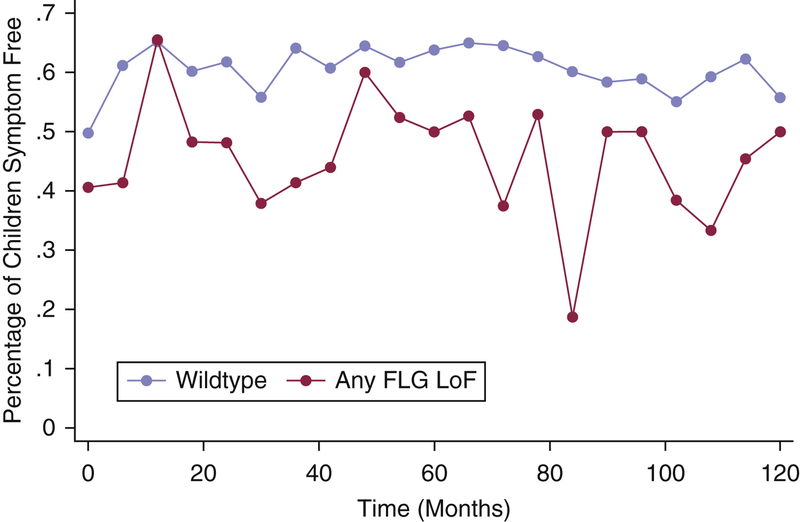

African American children with FLG LoF variant composite, based on the nine variants, have more persistent AD than children wildtype for FLG LoF (Figure 1). At nearly every time point (as displayed visually in Figure 1), African American children with at least one FLG LoF, were less likely to report that they were symptom free. The odds of an African American child reporting a 6-month period of disease free skin at any given time point was less in those with a FLG LoF variant than in those who did not have a variant (odds ratio: 0.36 (95% CI:0.14, 0.89) p=0.027) (p=0.024). The overall effect of FLG LoF on the persistence of AD was similar in those of African ancestry to our white cohort (0.45(0.22, 0.93)) (p=0.037). For the full cohort, the effect of the FLG LoF variant was 0.47 (0.27, 0.81) (p=0.006) and when adjusted for age of onset, race based on ancestral informative markers (Margolis et al., 2012), and gender the effect estimate was 0.42 (0.20, 0.74) (p=0.003).

Figure 1:

Percentage of African American children reporting symptom free skin during each 6 month period since time of enrollment in PEER.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to previous reports, we present findings from a large longitudinal study showing that there exist uncommon FLG exon 3 LoF variants in children of African ancestry that are associated with AD and with more persistent AD. The overall prevalence of FLG LoF variants are less than noted in a comparable cohort of white children and all of the African-American variants are uncommon (MAF < 5%) but the effect of these variants on persistence is similar to our previous observations in other races.(Margolis et al., 2012) Although the prevalence of AD in the US is highest among African-Americans, patients of African ancestry have been largely understudied.(Margolis et al., 2014a; Shaw et al., 2011) Studies have been unable to consistently identify FLG mutations in individuals with AD and African ancesty.(Margolis et al., 2014a; Policari et al., 2014; Thawer-Esmail et al., 2014; Winge et al., 2011) Using our current sequencing methods and informatics pipeline, we were also able to identify additional FLG LoF variants in patients of European ancestry beyond the commonly reported variants.(Margolis et al., 2012) In our previous study only 5.8% of the African Americans with AD had a FLG LoF variant.(Margolis et al., 2012) We now are able to show that 12.2% of this cohort will have a FLG LoF variant. We have also demonstrated the reliability of the MPS technique by comparing previous results to our current study.(Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis, Apter, Mitra, Gupta, Hoffstad, Papadopoulos et al., 2013; Margolis et al., 2014a) As expected, the MVF for the FLG LoF variants (p.R501X, c.2282del4 (p.S761fs), p.R2447X, and p.S3247X) in our current study was similar to those noted in our previous study. (Margolis et al., 2012)

Although previous studies have demonstrated FLG LoF variants in those of African ancestry, due to their rarity they have not been consistently detected, and their importance with respect to AD may have been overlooked.(Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2014a; Policari et al., 2014; Taylan et al., 2015; Thawer-Esmail et al., 2014; Winge et al., 2011) The results of the current study are in direct contrast to these previous reports including a report by some of the authors of this study.(Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2014a; Taylan et al., 2015; Thawer-Esmail et al., 2014; Winge et al., 2011) Fifty-three subjects included in this report had been previously evaluated in a published whole exome study.(Margolis et al., 2014a) The only meaningful technical difference between that study and our current analysis was the use of a local versus global alignment tool, which has been developed since that data were published.(Margolis et al., 2014a; McKenna et al., 2010) Using the local alignment tool the number of FLG LoF variants noted in these subjects increased from only two to nine (all rare).(Margolis et al., 2014a) It should be noted that one previous study did demonstrate decreased FLG breakdown products on the skin of subjects of African ancestry with AD, which in retrospect could have been caused by the undetected FLG LoF mutations.(Thawer-Esmail et al., 2014)

The difficulty of sequencing FLG is well known.(Palmer et al., 2006) The gene FLG is over 23kB and the majority of initially coded profilaggrin polyprotein, which is later processed to form the filaggrin protein, is encoded from exon 3.(Brown and McLean, 2012; Palmer et al., 2006; Sandilands et al., 2007) Exon 3 is not only large (>12kB), but also repetitive with 10–12 nearly identical tandem repeats of about 972 bp, making the area difficult to sequence.(Brown and McLean 2012; Lek et al., 2016; Margolis et al., 2014a; Palmer et al., 2006) Because of the intragenic homology of FLG, a recent report identified the FLG gene and several other genes as part of a so-called “NGS Dead Zone”. (Mandelker et al., 2016) It will be important for future studies to utilize improved bioinformatics tools and fully targeted approaches when evaluating this gene. (McKenna et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2017)

Our study does have some limitations. Prior convention suggests that FLG LoF mutations of exon 3 result in diminished production of filaggrin.(Palmer et al., 2006) However, at this time we do not have any direct evidence that most of the variants described in this study directly resulted in diminished production of filaggrin. This limitation is, however, true of many studies of FLG LoF variants. Most of our samples were obtained in the mail so we do not have easy access to study subjects and are not able to obtain tissue samples for FLG protein analysis. Even if possible, obtaining tissue to assess FLG for uncommon variants would require the identification and consent of a large number of participants. As has been recently noted, inflamed skin has diminished FLG production not specifically associated with FLG variation.(Pellerin et al., 2013; Seykora et al., 2015) In addition, as expected, children with FLG LoF mutations had more persistent disease. It is probable that all of the FLG LoF variants do have a profound effect on the production of FLG and skin barrier function. We focused only on FLG exon 3 LoF mutations and did not assess copy number variation, which others also have found to be associated with AD.(Brown and McLean, 2012) Our study focuses on African Americans and may not represent everyone with African ancestry. We included children with mild-moderate AD as per inclusion in the PEER cohort and this cohort may not generalize to everyone with AD. Finally, the group who agreed to provide DNA was not a random sample so it is possible that our findings may not generalize to the full PEER cohort.

In summary, we have shown that results from massively parallel sequencing and previous assays used for FLG LoF genotyping are highly concordant. Previous studies found that FLG LoF variants were not associated with the prevalence and persistence of AD in those of African ancestry may have missed associations due to technical limitations. We demonstrate that children of African ancestry with FLG LoF variants are more likely to have AD than those who do not have the LoF variants. The distribution of the frequency and the type of FLG LoF variants varies based on ancestry. The prevalence of these variants in children of African ancestry is less than those of European ancestry and Asian ancestry. Nonetheless, children with FLG LoF have more persistent AD and the overall effect of LoF mutations in African American children is similar to that seen in white children. In contrast to Europeans, no FLG LoF variants predominate in African American children. The variation in the prevalence and diversity of variants, is consistent with the genetic “bottleneck” hypothesized to have occurred with human migration out of Africa.(Amos and Hoffman, 2010) Finally, based on our results, properly determining FLG LoF status requires next generation sequencing techniques utilizing proper informatics tools.

Materials & Methods

Population and Design

The Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER; www.thepeerprogram.com) is a United States nationwide cohort of more than 8,000 subjects with pediatric-onset AD. The current study represents a subcohort of the 370 African Americans who previously participated in a study of genetics of AD.(Chang et al., 2017; Margolis et al., 2012) Self-described race was previously confirmed in this group using ancestral informative markers.(Margolis et al., 2012) At the time of enrollment, children were 2 to 17 years old, had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of AD, and had used pimecrolimus cream for at least 6 months.(Margolis et al., 2012) Subjects were followed for up to 10 years and during that time were not required to (and most did not) continue therapy with pimecrolimus.(Margolis et al., 2015) All patients provide written informed consent approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. Full details of the PEER cohort have been previously reported.(Margolis et al., 2015; Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2014b) In order to confirm the reliability of the MPS we also evaluated 133 previously assessed white subjects.(Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2013)

Genetic analysis

262 of the 370 eligible African American children had DNA sufficient to conduct MPS targeted capture. In order to confirm the reliability of the MPS technology, a sample of 133 of 433 white subjects from the PEER cohort were sequenced and their results were compared to the results that utilized a long range PCR and TaqMan-based approach.(Margolis et al., 2012) The goal of sequencing was the identification of exon 3 LoF FLG variants in African American children with AD. Exon 3 LoF variants have been previously described to diminish the production of FLG.(Brown and McLean, 2012; Palmer et al., 2006; Sandilands et al., 2007)

DNA was collected using Oragene DNA collection kits (DNA Genotek, Ottawa Canada). MPS was performed by creating a library preparation using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep kit. Briefly, 500 ng of input DNA was sheared on a Covaris Sonicator to a size of 150 bp. End repair was performed to remove overhangs and sequencing adapters were subsequently ligated to the blunt-ended fragments. Adapter ligated fragments were then PCR amplified, incorporating barcode sequences to enable downstream sample pooling. PCR amplified products were then size-selected by Ampure XP beads to ensure optimal insert sizes. To verify insert sizes and library concentration, size-selected genomic libraries were analyzed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument. Library concentrations were determined by Bioanalyzer analysis so that equimolar sample pooling prior to targeted capture-based enrichment of FLG occurred. Targeted capture was designed using Agilent SureDesign and included the entire FLG gene (exons and introns). 88% of the FLG gene was covered and the read depth was 185x. Samples were dual-indexed using appropriate SureSelect indexing primers (A01-H12), so that 96 samples were sequenced on a single lane of Illumina HiSeq 4000 instrument. Raw sequencing data were aligned and mapped to the reference genome hg19 using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.(Li and Durbin, 2010) Single nucleotide variant and insertion/deletion (indel) calling was accomplished using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) HaplotypeCaller, after following GATK Best Practices realignment and recalibration.(DePristo et al., 2011; McKenna et al., 2010; Van der Auwera et al., 2013) All calls were confirmed using VarDict and visualize using the integrative genomics viewer.(Lai et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2011)

Statistical Analysis

For the genetic prevalence study embedded in the longitudinal cohort study, variant frequency was reported as prevalence per individual (percent) of the minor variant and as genome minor variant frequency (MVF; percent with 95% confidence interval (CI)). Also, as is convention, a composite was created for all of the FLG LoF variants (no variant, a single variant, two or more variants including homozygote variant).(Brown and McLean, 2012; Margolis et al., 2012; Palmer et al., 2006; Sandilands et al., 2007) For this study we created a composite consistent with previous publications, which used the most common European (white) alleles and made a composite based on the findings from this study.(Margolis et al., 2012) The observed frequencies were compared to frequencies available from the gnomAD browser (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).(Wong et al., 2017)

To assess the reliability of the MPS technology, genotyping results from the current study were compared to previously reported long range PCR and TaqMan data using the Kappa statistic.(Margolis et al., 2012; Margolis et al., 2013) Comparisons between FLG LoF variant frequencies and the gnomAD browser were made using Fisher’s exact test. No correction was made for multiplicity because each comparison represented a pre-determined hypothesis.

Persistence was evaluated based on the self-reported outcome of whether or not a child’s skin was AD symptom-free during the previous 6-months.(Margolis et al., 2012) Persistence was determined by survey responses to a series of questions including: “During the last six months would you say that your child’s skin disease (AD) has shown: complete disease control, good disease control, limited disease control, or uncontrolled disease”. Symptom free was defined as an affirmative response of “complete disease control”. This finding has been shown to correlate with other tools used to evaluate symptom control.(Chang, et al 2017) The association between these outcomes (multiple outcomes recorded over time per participant) and the FLG variant composite were evaluated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) for binary outcomes assuming an independence working correlation structure with empirical standard errors. All analyses were conducted with Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Acknowledgement:

This study was funded by support from the NIH NIAMS R01-AR069062. The sponsor did not have a role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, the preparation of this report or in the decision to submit this report for publication. None of the authors have a financial conflict of interest with respect to this investigation.

Abbreviations:

- AD

Atopic Dermatitis

- CI

Confidence Interval

- FLG

Filaggrin

- LoF

Loss of Function

- MPS

Massively Parallel Sequencing

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

With respect to this investigation, none of the authors have a conflict of interest. The sponsor of this study is NIH NIAMS.

REFERENCES

- Abuabara K, Margolis DJ, Langan SM. The Long-Term Course of Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol Clin 2017;35:291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M FLG mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema: spectrum of mutations and population genetics. Brit J Dermatol 2010; 162:472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos W, Hoffman JI Evidence that two main bottleneck events shaped modern human genetic diversity. Proc Biol Sci 2010; 277:131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SJ, McLean WH One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132:751–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016; 536:285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr., Bolognia JL, Hodge JA, Rohrer TA, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76:958–72.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelker D, Schmidt RJ, Ankala A, McDonald GK, et al. Navigating highly homologous genes in a molecular diagnostic setting: a resource for clinical next-generation sequencing. Genet Med 2016; 18:1282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis DJ, Apter AJ, Gupta J, Bowser M, Sharma H, Duffy E, et al. The persistence of atopic dermatitis and Filaggrin mutations in a US longitudinal cohort. J Allergy Clin Immun 2012; 130:912–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis DJ, Apter AJ, Mitra N, Gupta J, Hoffstad O, Papadopoulos M, et al. Reliability and validity of genotyping filaggrin null mutations. J Dermatol Sci 2013; 70:67–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis DJ, Gupta J, Apter A, Hoffstad O, Papadopoulos M, Rebbeck TR, et al. Exome sequencing of Filaggrin and related genes in African-American children with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2014a; 134:2272–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis JS, Abuabrar K, Bilker W, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Persistence of mild of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 2014b; 150:593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010; 20:1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nature Genetics 2006; 38:441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L, Henry J, Hsu CY, Balica S, Jean-Decoster C, Mechin MC, et al. Defects in filaggrin-like proteins in both lesional and nonlesional atopic skin. J Allergy Clin Immun 2013; 131:1094–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policari I, Becker L, Stein SL, Smith MS, Paller AS. Filaggrin gene mutations in African Americans with both ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol 2014; 31:489–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandilands A, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Hull PR, O’Regan GM, Clayton TH, Watson RM, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the gene encoding filaggrin uncovers prevalent and rare mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema. Nature Genet 2007; 39:650–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seykora J, Dentchev T, Margolis DJ Filaggrin-2 barrier protein inversely varies with skin inflammation. Exp Dermatol 2015; 24:720–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: Data from the 2003 national survey of children’s health. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylan F, Nilsson D, Asad S, Lieden A, Wahlgren CF, Winge MCG, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of Ethiopian patients with ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136:507–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thawer-Esmail F, Jakasa I, Todd G, Brown SJ, Krobach K, Campbel LE, et al. South African amaXhosa patients with atopic dermatitis have decreased levels of filaggrin breakdown products but no loss-of-function mutations in filaggrin. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133:280–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winge MC, Bilcha KD, Lieden A, Shibeshi D, Sandilands A, Wahlgren CF, et al. Novel filaggrin mutation but no other loss-of-function variants found in Ethiopian patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165:1074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong XFCC Denil SLIJ, Foo JN, Chen H, Tay ASL, Haines RL, et al. Array-based sequencing of filaggrin gene for comprehensive detection of disease-associated variants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; in press doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]