Abstract

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer mortality in Japan and worldwide. Although previous studies identify various genetic variations associated with gastric cancer, host genetic factors are largely unidentified. To identify novel gastric cancer loci in the Japanese population, herein, we carried out a large‐scale genome‐wide association study using 6171 cases and 27 178 controls followed by three replication analyses. Analysis using a total of 11 507 cases and 38 904 controls identified two novel loci on 12q24.11‐12 (rs6490061, P = 3.20 × 10−8 with an odds ratio [OR] of 0.905) and 20q11.21 (rs2376549, P = 8.11 × 10−10 with an OR of 1.109). rs6490061 is located at intron 19 of the CUX2 gene, and its expression was suppressed by Helicobacter pylori infection. rs2376549 is included within the gene cluster of DEFB families that encode antibacterial peptides. We also found a significant association of rs7849280 in the ABO gene locus on 9q34.2 (P = 2.64 × 10−13 with an OR of 1.148). CUX2 and ABO expression in gastric mucosal tissues was significantly associated with rs6490061 and rs7849280 (P = 0.0153 and 8.00 × 10−11), respectively. Our findings show the crucial roles of genetic variations in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer.

Keywords: ABO, CUX2, DEFB, gastric cancer, genome‐wide association study

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- GWAS

genome‐wide association study

- J‐MICC

Japan Multi‐Institutional Collaborative Cohort

- JPHC study

Japan Public Health Center‐based prospective study

- OR

odds ratio

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative real‐time PCR

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- ToMMo

Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization

1. INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer mortality with 1.3 million cases and 819 000 deaths worldwide.1, 2 Approximately 90% of gastric cancer is adenocarcinoma, and gastric cancers are divided into cardiac or non‐cardiac gastric cancer by location and into diffuse type or intestinal type by histology.3 Helicobacter pylori, a spiral Gram‐negative bacterium, infects approximately half of the entire human population and causes progressive damage to the gastric mucosa.4, 5 Nearly 90% of gastric cancer patients are infected with H. pylori, 6 and eradication of H. pylori reduces the risk of gastric cancer,7 indicating its important role in gastric carcinogenesis. Eradiation of H. pylori and smoking cessation contribute to the decrease of gastric cancer incidence,8 but the prognosis of gastric cancer is still poor because the symptoms of gastric cancer tend to emerge during the late stage of the disease, and treatment options, such as chemotherapeutic agents, are limited. Currently, early‐stage gastric cancers are treated by endoscopic resection with a favorable prognosis.9 Therefore, identification of risk factors is important for early detection and improved prognosis of gastric cancer.

Our recent study indicated that a family history of gastric cancer was associated with a 2.44‐fold higher disease risk,10 and genetic factors are estimated to contribute 28% of gastric cancer risk according to a large‐scale twin study.11 CDH1 is a causative gene of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, caused by mismatch repair genes, such as MSH2 or MLH1, is also associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer.12 However, hereditary cancer syndromes are linked to <3% of gastric cancer cases.13 Therefore, the remaining 25% are likely to be explained partly by common variants and partly by uncommon variants with intermediate/high risk. Previous GWAS identified genetic variations associated with gastric cancer, such as PSCA (8q24.3),14 PLCE1 (10q23.33),15 MUC1 (1q22),14 3q13.31 and 5p13.1,16 5q14.3,17 6p21.1,18, 19 and ATM (11q22.3),20 as well as blood type A.21 However, the number of screening samples and the identified loci in these studies are relatively small compared with those of other cancers, such as prostate, breast, and colon.22 Herein, we carried out GWAS and replication analyses using case‐control sets with more than 50 000 samples and identified two novel loci on 12q24.11‐12 and 20q11.21. We also found a significant association of rs7849280 on 9q34.2 located near the ABO gene, which was not identified in the previous GWAS.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample

Characteristics of each cohort in GWAS are shown in Table 1. A total of 11 507 Japanese gastric cancer patients and 38 904 controls were obtained from BioBank Japan,23, 24 the Japan Public Health Center‐based prospective study (JPHC study),25 the J‐MICC study,26 and ToMMo,27 Aichi Cancer Center (replication 1),28 and the National Cancer Center (replication 2).14 All gastric cancer patients were histologically confirmed. Individuals with a past history of any cancer were excluded from the controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Stage | Sample | Source | Platform | Sample numbers (female %) | Age (y) (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | GC | BBJ | OEE or OE + HE | 6171 (25.4) | 66.7 ± 10.2 |

| Control | JPHC, J‐MICC, ToMMo | OEE | 27 178 (60.7) | 55.9 ± 10.0 | |

| Replication 1 | GC | ACC | Invader | 1374 (25.5) | 61.1 ± 27.3 |

| Control | ACC | Invader | 2049 (25.3) | 58.8 ± 24.0 | |

| Replication 2 | GC | NCC | Invader | 1332 (38.1) | 58.2 ± 12.6 |

| Control | NCC | Invader | 3205 (34.4) | 67.5 ± 13.2 | |

| Replication 3 | GC | BBJ | Invader | 2630 (25.2) | 69.9 ± 9.4 |

| Control | BBJ | Invader | 6472 (46.6) | 45.4 ± 18.1 |

ACC, Aichi Cancer Center; BBJ, Biobank Japan; GC, gastric cancer; GWAS, genome‐wide association study; HE, Human Exome; J‐MICC, Japan Multi‐Institutional Collaborative Cohort study; JPHC study, Japan Public Health Center‐based prospective study; NCC, National Cancer Center; OE, OmniExpress; OEE, OmmiExpressExome; ToMMo, Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization.

For gene expression analysis, gastric mucosal tissues from the gastric angulus and blood were obtained from patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and biopsy at the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic (280 individuals with H. pylori infection, and 28 individuals without H. pylori infection).29 Fifty‐three individuals with H. pylori infection underwent a second esophagogastroduodenoscopy 6 months to 1 year after the first esophagogastroduodenoscopy and successful eradication, and mucosal tissues were collected from the gastric angulus by biopsy. The remaining tissues were subjected to RNA extraction and qRT‐PCR analysis. Genomic DNA was purified from peripheral blood leukocytes. The number of samples analyzed in this study was determined based on the maximum number of samples available when we conducted the experiments. All participants provided informed consent, and the project was approved by the ethical committees at each institute.

2.2. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping and imputation analysis

The strategy of our screening is shown in Figure S1. In previous studies,30, 31 6171 gastric cancer cases and 27 178 controls were genotyped using Illumina OmniExpressExome or OmniExpress + HumanExome BeadChip (Table 1). We excluded the following samples from analysis: closely related samples, gender‐mismatched samples including lack of information, control samples with past history of any cancers, and samples from subjects whose ancestries were estimated to be distinct from East Asian populations using a principal component analysis. Approximately 951 117 SNP were genotyped in both platforms (OmniExpressExome or OmniExpress + HumanExome). Based on the genotyping results of 511 850 SNP on autosomal chromosomes that passed the quality control (QC) filters (call rate ≥0.99 in the case and control samples, minor allele frequency (MAF) of ≥0.01, and P value of Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium in the control group ≥1 × 10−6), imputation of the ungenotyped SNP was conducted by MaCH32 and minimac33 using data from the JPT/CHB/CHS (Japanese in Tokyo, Japan/Han Chinese in Beijing/South Han Chinese) subjects and using the 1000 genome project phase 1 (release 16, March 2012) as a reference. We excluded SNP that met the following criteria: MAF <0.01, Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium P value <1 × 10−6, R 2 < 0.4, or a large allele frequency difference between the reference panel and the GWAS (>0.16).31 We also excluded insertion/deletion polymorphisms.

Among 1293 SNP in 16 regions for which P <1 × 10−6, we selected one SNP from three previously reported regions (1q22, 5p13.1, and 8q24.3) that included a total of 849 SNP (Table S1). For 13 other novel regions, we selected SNP by linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis using the criterion of pairwise r 2 values <0.2 (Figure S2). Finally, we selected three SNP from 12q24.11‐12, but only one SNP from 12 other novel regions (Table S2). In the replication analysis, we genotyped 18 SNP in 2706 gastric cancer cases and 5254 controls (replication 1 and replication 2) using the multiplex PCR‐based Invader assay (Third Wave Technologies). Three SNP (rs7849280, rs6490061, and rs2376549) that were not identified by the previous GWAS and showed a significant association with gastric cancer in a meta‐analysis of GWAS, replication 1 and replication 2 were selected for further analysis using an additional cohort (replication 3). The investigators were blinded during the genotyping experiments.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We applied the SNP QC as follows: call rate ≥0.99 in the case and control samples, MAF ≥0.01, and P value of Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium in the control group ≥1 × 10−6. Consequently, 511 850 SNP on autosomal chromosomes passed the QC filters among the 951 117 SNP genotyped in both OmniExpressExome and OmniExpress + HumanExome.

Association of the SNP with gastric cancer risk was investigated by logistic regression analysis using PC1 and PC2 as covariates. In the GWAS, the genetic inflation factor λ was derived from the P values obtained by logistic regression analysis for all the tested SNP. The quantile‐quantile plot was drawn using the R program. λ1000 was calculated using the following formula34:

Odds ratios were calculated using major alleles as non‐effect alleles/reference alleles, unless stated otherwise. Combined analyses of the GWAS and the replication stage were conducted by using p‐link. Heterogeneity across the two stages was examined using Cochrane's Q test.35 We considered P = 5 × 10−8 (GWAS and meta‐analysis) as the significant threshold after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

2.4. ABO blood type estimation

Single nucleotide polymorphisms rs505922 and rs8176746 on the ABO gene were used for ABO blood type estimation, as previously described.36 Single‐nucleotide deletion at amino acid position 87 in exon 6 (rs8176719) results in the O allele, and C796A in exon 7 (rs8176746) distinguishes the B allele from the A or O allele. rs505922 was used as a marker of the O allele37, and we also confirmed a strong LD between rs505922 and rs8176719 (r 2 = 0.97) through the genotyping of both SNP in 94 individuals. Thus, we estimated the blood type based on the genotypes of rs505922 and rs8176746.

2.5. Quantitative real‐time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from human tissues using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNAs were synthesized using Super Script III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). qRT‐PCR was conducted using the SYBR Green Master Mix on a Light Cycler 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Absolute copy numbers were calculated using serial dilutions of a plasmid, including a cDNA fragment as a standard. Expression levels of CUX2 and ABO mRNA were normalized against GAPDH. The primer sequences used are shown in Table S3.

2.6. Genome‐wide gene association analysis

SNP‐based P values from the GWAS were used as input for the gene‐based analysis. We used all 19 427 protein‐coding genes as the basis for a genome‐wide gene association analysis in MAGMA (http://ctg.cncr.nl/software/magma).38 After SNP annotation, there were 17 599 genes covered by at least one SNP. Gene association tests were carried out by taking the LD between the SNP into account using 1000 Genomes East Asian data. We applied a stringent Bonferroni correction to account for multiple testing, setting the genome‐wide threshold for significance at 2.84 × 10−6 (= 0.05/17 599).

2.7. Creation of a genetic risk‐prediction model

A total of six significant variants (rs1057941, rs13361707, rs2294008, rs7849280, rs6490061, and rs2376549) were incorporated into a genetic risk‐prediction model for gastric cancer as explanatory variables in a logistic regression model. To establish the risk‐prediction model, each sample was scored on each of the six variants with the frequency of risk alleles. OR were estimated for each sample based on the following formula:

where βn are the regression coefficients and x n are the scores of each valuable. The R software package Epi was used to draw receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots and calculate AUC.

2.8. Data availability

Individual phenotype data, genotyping data, imputation data and summary statistics that support the findings of this study can be found at National Bioscience Database Center with the accession code hum0014 (http://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/). Some access restrictions are applied to the individual data for approved reasons.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Genome‐wide association screening of gastric cancer

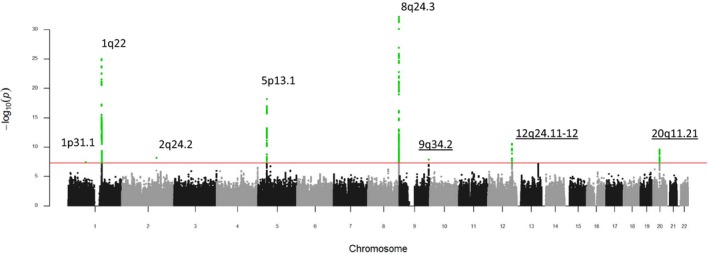

In the present study, a total of 11 507 gastric cancer patients and 38 904 controls from four independent cohorts were analyzed (Table 1 and Figure S1). In the screening stage, 6171 gastric cancer patients and 27 178 non‐cancer controls that were genotyped using the Illumina OmniExpressExome or OmniExpress + HumanExome BeadChip were used for association analysis. After carrying out a standard QC procedure (MAF ≥0.01, HWE ≥1 × 10−6, and call rate ≥0.99), we selected 511 850 SNP for further analysis. Then, we conducted genome‐wide imputation and obtained association results for 6 573 681 SNP (R 2 ≥0.4). The genomic inflation factor λ was 1.2280 (Figure S3) and 1.0227 (λ1000).34 In addition to three previously reported loci (1q22, 5p13.1, and 8q24.3),14, 16 five genomic regions at 1p31.1 (RPL7P10), 2q24.2 (BAZ2B), 9q34.2 (ABO), 12q24.11‐12 (CCDC63‐CUX2), and 20q11.21 (DEFB115‐DKKL1P1‐LOC149935‐DEFB116‐RPL31P3‐LOC100133268‐DEFB118‐DEFB119‐DEFB121‐DEFB122‐DEFB123‐REM1) showed a significant association with a P value of <5 × 10−8, as shown in Figure 1 and Table S4.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot showing genome‐wide P values of association. The genome‐wide P values of 6 573 681 autosomal single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in 6171 cases and 27 178 controls from the screening phase are shown. Three previously reported loci (1q31.1, 5p13.1, and 8q24.3) and five novel loci indicate a significant association. Red horizontal line represents the genome‐wide significance threshold of P = 5.0 × 10−8. Association of the SNP with gastric cancer risk was investigated by logistic regression analysis using PC1 and PC2 as covariates

3.2. Replication and meta‐analysis

Next, we selected 18 SNP in 16 genomic regions with strong associations (P < 1.0 × 10−6) for further replication analysis by a multiplex‐polymerase chain reaction‐based Invader assay (Table S2).39 We selected high‐LD SNP rs13361707, rs2294008, and rs2376549, instead of rs1692252, rs2978977, and rs6088146, within 5p13.1, 8q24.3, and 20q11.21, respectively, because we could not design probes for rs1692252, rs2978977, and rs6088146. These 18 SNP were analyzed using two Japanese cohorts consisting of 2706 cases and 5254 controls.40, 41 Three SNP (rs7849280 on 9q34.2, rs6490061 on 12q24.11‐12, and rs2376549 on 20q11.21) that were not identified by the previous GWAS and showed a significant association with gastric cancer in a meta‐analysis of three cohorts were further analyzed using an additional cohort (replication 3 including 2630 cases and 6472 controls). A meta‐analysis of three replication cohorts showed a significant association for three SNP with P values of 1.90 × 10−6, 0.0271, and 0.0428 (Table S5). A meta‐analysis of four cohorts indicated that three loci on 9q34.2, 12q24.11‐12, and 20q11.21 were significantly associated with gastric cancer risk (P values of 2.64 × 10−13, 3.20 × 10−8, and 8.11 × 10−10 and OR values of 1.148, 0.905, and 1.109, respectively) without significant heterogeneity (Table 2 and Figure S4). We also confirmed the association of previously reported loci at 1q22 (rs1057941), 5p13.1 (rs13361707), and 8q24.3 (rs2294008) (Table 2 and Figure S5).

Table 2.

Results of association analysis of gastric cancer in each stage

| SNP | Chr | Effect allele | GWAS | Replication 1 | Replication 2 | Replication 3 | Meta_replication | Meta | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | P | ORa | P | ORa | P | ORa | P | ORa | P | Q b | I c | ORa | P | Q b | I c | |||

| rs1057941 | 1 | G | 0.743 | 1.03 × 10−25 | 0.838 | 6.21 × 10−3 | 0.718 | 1.06 × 10−7 | 0.773 | 1.04 × 10−8 | 0.085 | 66.36 | 0.751 | 2.36 × 10−33 | 0.170 | 43.55 | ||

| rs13361707 | 5 | C | 1.186 | 6.74 × 10−17 | 1.225 | 5.36 × 10−5 | 1.108 | 2.64 × 10−2 | 1.160 | 1.26 × 10−5 | 0.142 | 53.63 | 1.180 | 1.02 × 10−21 | 0.291 | 18.91 | ||

| rs2294008 | 8 | C | 0.785 | 4.64 × 10−25 | 0.765 | 6.06 × 10−7 | 0.649 | 2.13 × 10−17 | 0.702 | 8.83 × 10−22 | 0.026 | 79.85 | 0.761 | 1.47 × 10−44 | 0.003 | 82.73 | ||

| rs7849280 | 9 | G | 1.163 | 1.34 × 10−8 | 1.127 | 3.15 × 10−2 | 1.047 | 3.74 × 10−1 | 1.185 | 4.30 × 10−6 | 1.134 | 1.90 × 10−6 | 0.147 | 47.88 | 1.148 | 2.64 × 10−13 | 0.233 | 29.85 |

| rs6490061 | 12 | T | 0.863 | 8.07 × 10−9 | 0.902 | 5.26 × 10−2 | 0.943 | 2.38 × 10−1 | 0.967 | 3.34 × 10−1 | 0.946 | 2.71 × 10−2 | 0.550 | 0.00 | 0.905 | 3.20 × 10−8 | 0.052 | 61.09 |

| rs2376549 | 20 | C | 1.149 | 3.21 × 10−10 | 1.086 | 1.43 × 10−1 | 1.043 | 3.93 × 10−1 | 1.047 | 2.12 × 10−1 | 1.054 | 4.28 × 10−2 | 0.834 | 0.00 | 1.109 | 8.11 × 10−10 | 0.079 | 55.89 |

Non‐effect alleles were considered as references.

P value for Cochrane's Q statistic.

I 2 heterogeneity index.

GWAS, genome‐wide association study; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

3.3. Subgroup analysis

Because our GWAS showed a high genomic inflation factor of 1.2280, we excluded SNP within the three previously reported loci (1q22, 5p13.1, and 8q24.3) that were significantly associated with gastric cancer in our current study. However, the genomic inflation factor λ was still 1.2269 (Figure S6) and 1.0226 (λ1000). The genomic inflation factor λ was also similar (λ = 1.2388, Figure S7) when we used only the 511 850 SNP genotyped by Illumina SNP CHIP. When we included PC1‐10 as covariates, λ was reduced to 1.1474 (Figure S8a). Although SNP on 9q34.2 did not clear the GWAS threshold in the screening stage (P = 9.72 × 10−8, Table S6 and Figure S8b), this SNP indicated significant association in the replication analysis (P = 1.90 × 10−6 and OR = 1.134, Table 2). Because the age and gender distribution was different between the cases and controls in this study, we also assessed six significant SNP by logistic regression analysis using age and gender as covariates. As a result, all six SNP showed a significant association in the screening stage (P < 5 × 10−8), replication stage (P < 0.05), and meta‐analysis of four cohorts (P < 5 × 10−8) (Table S7). Although we cannot exclude the potential impact of population stratification in the screening stage, all six loci were considered to be associated with gastric cancer in the Japanese population.

We further analyzed the six significant SNP in the two major subtypes of gastric cancer, diffuse type and intestinal type,3 using samples from the screening stage. All six SNP were significantly associated with both diffuse‐type (n = 1452) and intestinal‐type (n = 1425) gastric cancer (P < 0.05, Table S8). All the SNP showed a stronger association with diffuse‐type gastric cancer than with intestinal type, although this was not statistically significant, with the exception of 1q22 and 8q24.3 (Table S9). Then, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on gender and age and found that rs7849280 on 9q34.2 showed a stronger effect among females (OR = 1.127 for male and OR = 1.290 for female, P het = 0.022, Table S10), suggesting a histology‐ and gender‐dependent impact of genetic factors on gastric carcinogenesis. In addition, all six SNP showed stronger impact in early‐onset gastric cancer (64 years old or younger) (Tables S11 and S12).

We also analyzed previously reported loci. In addition to 1q22, 5p13.1, and 8q24.3, we evaluated SNP rs9841504 at 3q13.31 (ZBTB20),16 rs7712641 at 5q14.3,17 rs2494938 at 6p21.1 (LRFN2),18, 19 rs2294693 at 6p21.1 (UNC5CL), and rs2274223 at 10q23.33 (PLCE1)15 in our GWAS sample set. As a result, only SNP rs9841504 showed an association with the same risk allele as the previous report (P = 0.0167 and OR = 0.939, Table S13); although the effects of this SNP were very small compared to the previous study (OR = 0.76).

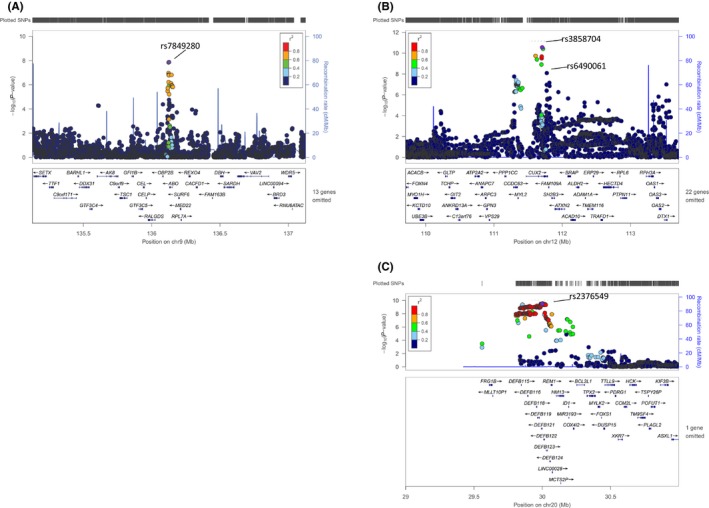

3.4. Functional analysis of 9q34.2, 12q24.11‐12, and 20q11.21

Regional plots of the three significant loci are shown in Figure 2. Several SNP on 1q22, 8q24.3, 9q34.2, and 12q24.11‐12 showed a strong association (P < 1 × 10−5) even after conditioning with lead SNP (rs1057941, rs2294008, rs7849280 and rs6490061), but SNP in 5p13.1 and 20q11.21 did not show a strong association (Figure S9). SNP rs7849280 on 9q34.2 is located in the 3′ flanking region of the ABO gene. Association of ABO blood type with gastric cancer risk was previously reported.21 ABO blood type is determined by genetic variations of ABO genes associated with enzymatic activity of the glycosyltransferase encoded by the ABO gene. Therefore, we estimated the ABO blood type using the genotyping results of two tagging SNP (rs505922‐T and rs8176746‐A), which were shown to be associated with the O and B alleles of the ABO gene, respectively.37 We successfully determined the ABO blood type in 98.7% of samples and found that individuals with blood types O, B, and AB showed significantly lower risks for gastric cancer compared with those with blood type A (OR = 0.81‐0.87, Table S14), and this effect was more prominent in female patients, concordant with that of rs7849280 (OR = 0.82‐0.90 and 0.70‐0.83 for male and female, respectively). In addition, blood type A showed stronger effect in early‐onset gastric cancer (Table S15). Interestingly, the G allele frequency was 75.3% among AA blood type, 37.5%‐37.6% among AO or AB blood types, and 0.6%‐2.2% among BB, BO, or OO blood types (Table S16), suggesting that the A allele of the ABO gene was in strong LD with the risk G allele of rs7849280. However, multivariate analysis showed that both rs7849280 and blood type A remained associated with gastric cancer risk, with P values of 0.0137 and 0.0455, respectively (Table S17). We also evaluated ABO expression in gastric mucosal tissues with different H. pylori infection statuses.29 As a result, ABO expression was markedly decreased in the stomach tissues of subjects with H. pylori infection compared with those without H. pylori infection (Figure S10a), whereas H. pylori eradication reactivated ABO expression (Figure S10b). Moreover, higher ABO expression was associated with risk G allele of rs7849280 (Figure S10c, P = 8.00 × 10−11). These findings suggested that multiple genetic variations that regulate ABO expression and/or glycosyltransferase activity are associated with gastric cancer risk in this locus.

Figure 2.

Regional plots of three loci for gastric cancer. The −log10 P values from the screening stage in (A) 9q34.2 (rs7849280), (B) 12q24.11‐12 (rs6490061), and (C) 20q11.21 (rs2376549) are shown. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) genotyped in the replication stage are shown in the figure. Estimated recombination rates (from 1000 Genomes) are plotted in blue. The SNP are color coded to reflect their correlation with the genotyped SNP. Pairwise r 2 values are from 1000 Genomes East Asian data (March 2012 release). The genes, position of the exons and direction of transcription are noted. The plots were generated using LocusZoom (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom)

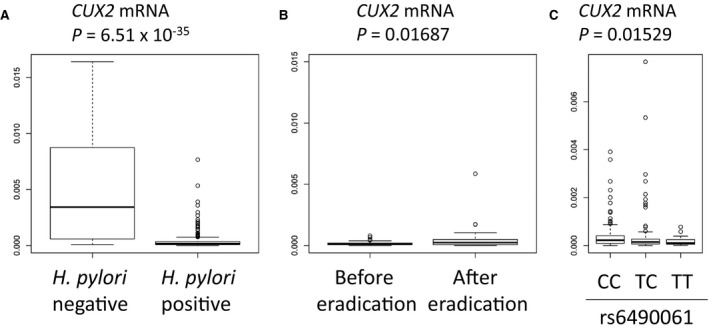

Twelve SNP within a 477‐kb region, including the CCDC63‐CUX2 genes on 12q24.11‐12, and 228 SNP within a 263‐kb region, including the DEFB family genes on 20q11.21, showed significant associations in the screening stage (P < 5 × 10−8, Table S4). However, none of these SNP alter the amino acid sequence. SNP rs6490061 is located at intron 19 of the CUX2 gene. Interestingly, CUX2 expression was markedly decreased in he H. pylori‐positive stomach (Figure 3A), whereas H. pylori eradication did not recover CUX2 expression levels (Figure 3B). Moreover, the risk C allele of rs6490061 was associated with a higher CUX2 mRNA expression (P = 0.0153, Figure 3C). Because CUX2 functions as an accessory factor that promotes the repair of oxidative DNA damage,42 H. pylori infection might suppress CUX2 expression and subsequently increase gastric cancer risk by damaging the DNA repair pathway.

Figure 3.

Regulation of CUX2 expression by Helicobacter pylori infection and host genetic factors. Box plots indicate the qRT‐PCR analysis of CUX2 mRNA levels in the biopsy samples from the background gastric mucosa. Vertical axis indicates the expression level of CUX2 normalized against GAPDH expression. Box, 25th and 75th percentiles; middle line in the box, median; whiskers, min value inside the 25th percentile − 1.5 × interquartile range and max value inside the 75th percentile + 1.5 × interquartile range; points, outliers. A, CUX2 mRNA in H. pylori‐negative controls (n = 28) and H. pylori‐infected patients (n = 280). B, CUX2 expression levels in each individual patient (n = 53) before and after H. pylori eradication. C, Association of rs6490061 with CUX2 expression in H. pylori‐infected patients (CC, n = 143; TC, n = 117; TT, n = 20). P values were calculated by a t test (A, B) or Kruskal‐Wallis test (C). CC, TC, and TT are genotpe at rs6490061

The cluster of DEFB family genes is located on 20q11.21 (Figure 2). DEFB families that encode antimicrobial peptides are dominantly expressed in the male reproductive organs, such as the testis and epididymis.43 Analyses using the eQTL database of a GTEx data portal (http://www.gtexportal.org/home/)44 indicated that SNP rs2376549 is associated with DEFB121 expression in the testis and DEFB119 expression in the esophagus (Figure S11). Interestingly, the low‐risk T allele was associated with higher DEFB expression, suggesting that DEFB have a protective effect against H. pylori infection.

We also conducted a genome‐wide gene association analysis and found that 15 loci were significantly associated with gastric cancer (P < 2.84 × 10−6), including three known (1q22, 5p13.1, and 8q24.3) and two novel (CUX2 and DEFB) loci (Figure S12). The other 10 loci, including SPSB1, CCDC141, AP1AR, ARHGAP26, RAB3IL1, MTUS2, GPR18, NRXN3, ADCY7, and SAE1, were also likely to be associated with gastric cancer.

Then, we constructed the risk‐prediction mode using the six significant SNP (Figure S13). AUC for total gastric cancer was 0.581, suggesting a modest impact of these SNP on gastric cancer risk. Subgroup analysis indicated that the AUC of males and females were the same (0.583), whereas the AUC of diffuse‐type gastric cancer (0.602) was higher than that of intestinal‐type (0.569). These results suggested that genetic factors play more important roles in the development of diffuse‐type gastric cancer, concordant with the subgroup analysis (Table S8).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we conducted a large‐scale GWAS using more than 50 000 people in a Japanese population and identified significant loci at 9q34.2, 12q24.11‐12, and 20q11.21. Our results showed that H. pylori infection markedly suppressed CUX2 expression, and rs6490061 was associated with CUX2 expression, suggesting that CUX2 might be a causative gene in 12q24.11‐12. H. pylori infection might have a stronger impact among risk C allele carriers because of the higher CUX2 expression level in the stomach. Although the association of rs6490061 with gastric cancer was marginal (P = 3.2 × 10−8), rs6490061 showed a strong association with a P value of 1.22 × 10−11 after adjusting for age and gender. Many SNP in 12q24.11‐12 showed a strong association even after conditioning with rs6490061 (Figure S9b), suggesting the involvement of multiple variations in these loci with gastric cancer risk. Functional variation rs671 in ALDH2 was also associated with gastric cancer risk in the screening stage (P = 7.57 × 10−9 and OR = 0.773), but this SNP was excluded from further analyses as a result of the low level of imputation accuracy (r 2 of 0.2677). rs671 is associated with alcohol metabolism,45 and alcohol is also a risk factor for various cancers.46 Therefore, we want to evaluate the interaction of alcohol, rs671 and rs6490061 in the development of gastric cancer in a future study using samples with information about alcohol consumption.

The 20q11.21 locus is not reported to be associated with cancers, but this locus is reported to be associated with inflammatory bowel diseases, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.47 DEFB family members are included within 300 kb of the associated region, and these genes encode the beta subfamily of defensins that function as antimicrobial peptides and protect tissues from bacterial infections.48 In addition, the risk allele of rs2376549 is associated with a low expression of DEFB121 and DEFB119. Therefore, DEFB families are likely to be causal genes in this locus. rs2376549 is also associated with FRG1B expression in the stomach; however, FRG1B is a pseudogene and its role is not understood so far.

In the present study, we excluded 9q34.3 from the novel locus because blood type A is known to be associated with gastric cancer risk and rs7849280 was associated with the A allele of the ABO gene. However, the risk G allele of rs7849280 was associated with higher ABO mRNA expression, whereas H. pylori infection suppressed ABO mRNA expression. A previous report indicated enhanced binding of H. pylori to epithelial cells of individuals with blood type O, which resulted in increased acute inflammatory response and peptic ulcer risk.49 Accumulating evidence indicates that acute inflammation may inhibit the development of cancer but chronic inflammation promotes cancer development.50 Current and previous studies showed the association of blood types A and O with gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer,51, 52 respectively. These findings suggest that both rs7849280 and ABO blood type are key regulators of host‐bacterial interaction and H. pylori‐related diseases.

Among eight loci identified in the previous studies, 1q22, 5p13.1 and 8q24.3 cleared GWAS threshold. Rare loss of function variations on ATM 20 was not evaluated in our imputation analysis because of low allelic frequency in the Japanese population. Among the remaining four loci that were identified in the GWAS of the Chinese population, 3q13.31 indicated significant association with the same risk allele (P = 0.0167), whereas the remaining three loci did not. Concordant with this result, 3q13.31 was validated in the meta‐analysis.53 Considering the sufficient number of samples used in our imputation analysis (6171 cases and 27 178 controls), these results would be due to differences in host genetic background and/or H. pylori subtypes54 between Chinese and Japanese.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of gastric cancer using 11 507 gastric cancer samples, and we identified two novel loci that would be associated with antibacterial response (20q11.21) and DNA repair (12q24.11‐12). However, AUC of the risk prediction system using six significant SNP was 0.583 which is not sufficient for stratification of individuals using genetic risk score only. In addition, these results need to be validated in other ethnic groups. Although the eradication of H. pylori reduces gastric cancer risk, the risk reduction is as low as 30%‐40%, and a substantial proportion of the subjects develop gastric cancer even after H. pylori eradiation.55 Because post‐eradication gastric cancer is an important clinical problem, the development of a risk‐prediction system is necessary to identify high‐risk individuals with current or past H. pylori infection. We hope our findings will contribute to the elucidation of the molecular pathology of gastric cancer and the implementation of personalized medical care for this disease.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the participants in this study. We would like to express our gratefulness to the staff of BioBank Japan, Tohoku Medical Megabank, Iwate Tohoku Medical Megabank, J‐MICC, and JPHC for their outstanding assistance. This study was partially supported by the BioBank Japan project and the Tohoku Medical Megabank project, which is supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology Japan and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The JPHC Study was supported by the National Cancer Research and Development Fund since 2010 and was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan from 1989 to 2010. The J‐MICC Study was supported by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research for Priority Areas of Cancer (17015018) and Innovative Areas (221S0001) and the JSPS KAKENHI Grant (16H06277) from the Japan Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology. This study was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants (25293168 to Ko.M and 15K08792 to Ke. M.).

Tanikawa C, Kamatani Y, Toyoshima O, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies gastric cancer susceptibility loci at 12q24.11‐12 and 20q11.21. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:4015–4024. 10.1111/cas.13815

REFERENCES

- 1. Herrero R, Park JY, Forman D. The fight against gastric cancer – the IARC Working Group report. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:1107‐1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration , Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, et al. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505‐527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so‐called intestinal‐type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo‐clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:629‐641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127‐1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori . Int J Cancer. 2015;136:487‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high‐risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:187‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnold M, Karim‐Kos HE, Coebergh JW, et al. Recent trends in incidence of five common cancers in 26 European countries since 1988: analysis of the European Cancer Observatory. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1164‐1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, et al. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262‐270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hirata M, Matsuda K. Cross‐sectional analysis of BioBank Japan clinical data: a large cohort of 200,000 patients with 47 common diseases. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:S9‐S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer–analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:78‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McLean MH, El‐Omar EM. Genetics of gastric cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:664‐674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sereno M, Aguayo C, Guillen Ponce C, et al. Gastric tumours in hereditary cancer syndromes: clinical features, molecular biology and strategies for prevention. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:599‐610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Study Group of Millennium Genome Project for Cancer , Sakamoto H, Yoshimura K, et al. Genetic variation in PSCA is associated with susceptibility to diffuse‐type gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:730‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Hu N, et al. A shared susceptibility locus in PLCE1 at 10q23 for gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:764‐767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi Y, Hu Z, Wu C, et al. A genome‐wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for non‐cardia gastric cancer at 3q13.31 and 5p13.1. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1215‐1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Z, Dai J, Hu N, et al. Identification of new susceptibility loci for gastric non‐cardia adenocarcinoma: pooled results from two Chinese genome‐wide association studies. Gut. 2017;66:581‐587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jin G, Ma H, Wu C, et al. Genetic variants at 6p21.1 and 7p15.3 are associated with risk of multiple cancers in Han Chinese. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:928‐934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu N, Wang Z, Song X, et al. Genome‐wide association study of gastric adenocarcinoma in Asia: a comparison of associations between cardia and non‐cardia tumours. Gut. 2016;65:1611‐1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Helgason H, Rafnar T, Olafsdottir HS, et al. Loss‐of‐function variants in ATM confer risk of gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:906‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Z, Liu L, Ji J, et al. ABO blood group system and gastric cancer: a case‐control study and meta‐analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:13308‐13321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang CQ, Yesupriya A, Rowell JL, et al. A systematic review of cancer GWAS and candidate gene meta‐analyses reveals limited overlap but similar effect sizes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:402‐408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nagai A, Hirata M, Kamatani Y, et al. Overview of the BioBank Japan Project: study design and profile. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:S2‐S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirata M, Nagai A, Kamatani Y, et al. Overview of BioBank Japan follow‐up data in 32 diseases. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:S22‐S28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsugane S, Sobue T. Baseline survey of JPHC study–design and participation rate. Japan Public Health Center‐based Prospective Study on Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases. J Epidemiol. 2001;11:S24‐S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamajima N, J‐MICC Study Group . The Japan Multi‐Institutional Collaborative Cohort Study (J‐MICC Study) to detect gene‐environment interactions for cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:317‐323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuriyama S, Yaegashi N, Nagami F, et al. The Tohoku Medical Megabank Project: design and mission. J Epidemiol. 2016;26:493‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsuo K, Oze I, Hosono S, et al. The aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) Glu504Lys polymorphism interacts with alcohol drinking in the risk of stomach cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1510‐1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mori J, Tanikawa C, Ohnishi N, et al. EPSIN 3, a novel p53 target, regulates the apoptotic pathway and gastric carcinogenesis. Neoplasia. 2017;19:185‐195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akiyama M, Okada Y, Kanai M, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies 112 new loci for body mass index in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1458‐1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Low SK, Takahashi A, Ebana Y, et al. Identification of six new genetic loci associated with atrial fibrillation in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2017;49:953‐958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A genome‐wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341‐1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome‐wide association studies through pre‐phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955‐959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Freedman ML, Reich D, Penney KL, et al. Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36:388‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II–The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1987;(82):1‐406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakao M, Matsuo K, Ito H, et al. ABO genotype and the risk of gastric cancer, atrophic gastritis, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20:1665‐1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakao M, Matsuo K, Hosono S, et al. ABO blood group alleles and the risk of pancreatic cancer in a Japanese population. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1076‐1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: generalized gene‐set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ohnishi Y, Tanaka T, Ozaki K, Yamada R, Suzuki H, Nakamura Y. A high‐throughput SNP typing system for genome‐wide association studies. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:471‐477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hidaka A, Sasazuki S, Matsuo K, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of ADH1B, ADH1C and ALDH2, alcohol consumption, and the risk of gastric cancer: the Japan Public Health Center‐based prospective study. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:223‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saeki N, Saito A, Choi IJ, et al. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in mucin 1, at chromosome 1q22, determines susceptibility to diffuse‐type gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:892‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pal R, Ramdzan ZM, Kaur S, et al. CUX2 protein functions as an accessory factor in the repair of oxidative DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22520‐22531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schutte BC, Mitros JP, Bartlett JA, et al. Discovery of five conserved beta‐defensin gene clusters using a computational search strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2129‐2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Consortium GT. Human genomics. The Genotype‐Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648‐660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takeshita T, Morimoto K, Mao XQ, Hashimoto T, Furuyama J. Phenotypic differences in low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase in Japanese workers. Lancet. 1993;341:837‐838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:292‐293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. Host‐microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119‐124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pazgier M, Hoover DM, Yang D, Lu W, Lubkowski J. Human beta‐defensins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1294‐1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alkout AM, Blackwell CC, Weir DM. Increased inflammatory responses of persons of blood group O to Helicobacter pylori . J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1364‐1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Korniluk A, Koper O, Kemona H, Dymicka‐Piekarska V. From inflammation to cancer. Ir J Med Sci. 2017;186:57‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tanikawa C, Urabe Y, Matsuo K, et al. A genome‐wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for duodenal ulcer in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2012;44:430‐434, S1‐S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hansson LE, Nyren O, Hsing AW, et al. The risk of stomach cancer in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:242‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shi J, Li W, Ding X. Assessment of the association between ZBTB20 rs9841504 polymorphism and gastric and esophageal cancer susceptibility: a meta‐analysis. Int J Biol Markers. 2017;32:e96‐e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ogura M, Perez JC, Mittl PR, et al. Helicobacter pylori evolution: lineage‐specific adaptations in homologs of eukaryotic Sel1‐like genes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Doorakkers E, Lagergren J, Engstrand L, Brusselaers N. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djw132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Individual phenotype data, genotyping data, imputation data and summary statistics that support the findings of this study can be found at National Bioscience Database Center with the accession code hum0014 (http://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/). Some access restrictions are applied to the individual data for approved reasons.