Abstract

To obtain enantiopure compounds, the so-called chiral high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method, i.e., HPLC using a chiral stationary phase, is very useful, as reviewed in the present Special Issue. On the other hand, normal HPLC (on silica gel) separation of diastereomers is also useful for the preparation of enantiopure compounds and also for the simultaneous determination of their absolute configurations (ACs). The author and coworkers have developed some chiral molecular tools, e.g., camphorsultam dichlorophthalic acid (CSDP acid), 2-methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid (MαNP acid), and others suitable for this purpose. For example, a racemic alcohol is esterified with (S)-(+)-MαNP acid, yielding diastereomeric esters, which are easily separable by HPLC on silica gel. The ACs of the obtained enantiopure MαNP esters can be determined by the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method. In addition, MαNP or CSDP esters have a high probability of giving single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography. From the X-ray Oak Ridge thermal ellipsoid plot (ORTEP) drawing, the AC of the alcohol part can be unambiguously determined because the AC of the acid part is already known. The hydrolysis of MαNP or CSDP esters yields enantiopure alcohols with the established ACs. The mechanism and application examples of these methods are explained.

Keywords: chiral molecule, absolute configuration, diastereomers, HPLC separation on silica gel, 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy, X-ray crystallography, internal reference of absolute configuration

1. Introduction

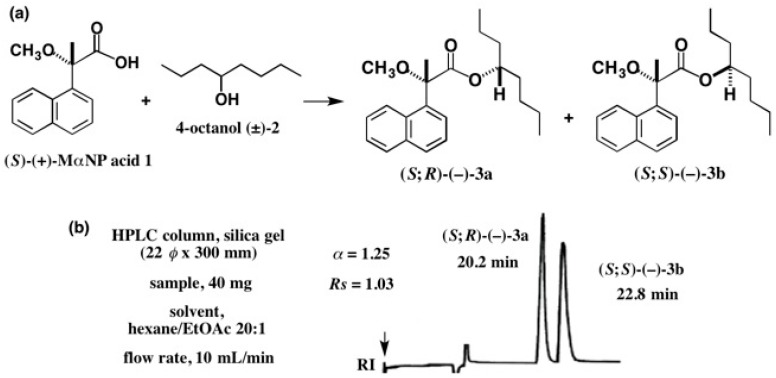

It is well known that the so-called chiral high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method, i.e., HPLC with a chiral stationary phase, is very useful for the separation of enantiomers, i.e., the preparation of enantiopure compounds [1,2,3,4,5], as will be explained in other review articles and/or research papers reported in this Special Issue. On the other hand, there is another HPLC method for the preparation of enantiopure compounds, where diastereomers are separated by normal HPLC on silica gel [6,7,8,9,10,11], or by reversed-phase HPLC [12]. For example, racemic 4-octanol (±)-2 was esterified with (S)-(+)-2-methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid 1 (MαNP acid) yielding a diastereomeric mixture of esters 3a and 3b (Figure 1) [13]. It was surprising to find that diastereomeric esters 3a and 3b (40 mg sample) could be completely separated by HPLC on silica gel (separation factor α = 1.25; resolution factor Rs = 1.03), regardless of the very small chirality of the 4-octanol moiety, which is generated by the difference between propyl (C3) and butyl (C4) groups; especially since both are normal chain alkyl groups. Please note that in this review article, the diastereomers are designated by compound numbers., e.g., 3a and 3b, where small letter a indicates the first-eluted fraction in HPLC, and b is the second-eluted one.

Figure 1.

Preparation of diastereomeric 4-octanol (S)-(+)-2-methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid (MαNP) esters 3a and 3b (a) and separation by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on silica gel (b). Redrawn with permission from [13].

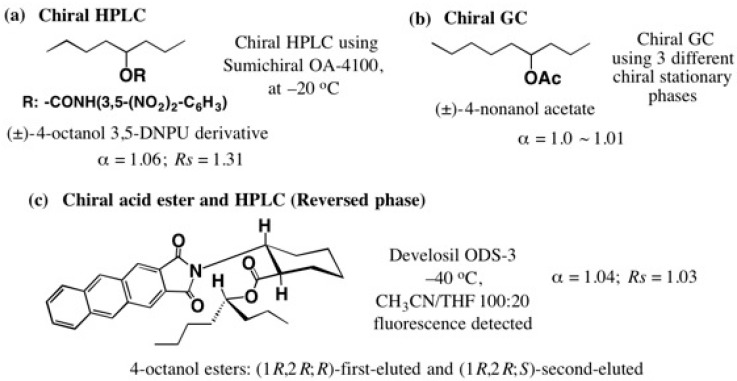

In general, it is very difficult to separate enantiomers or diastereomers composed of C, H, and O atoms by HPLC or gas chromatography (GC), especially in the case of aliphatic chain compounds. For example, Figure 2 shows the separation results of 4-octanol or 4-nonanol, reported to date: (a) a racemic 4-octanol 3,5-DNPU (3,5-dinitrophenylurethane) derivative was subjected to chiral HPLC at −20 °C, but the separation factor α remained low as α = 1.06 [14]; (b) separation of racemic 4-nonanol acetate was attempted by chiral GC, but this was not successful, α = 1.0~1.01 [15]; (c) racemic 4-octanol was esterified with a chiral acid yielding diastereomers, which were separated by HPLC (reversed phase) at −40 °C, but α remained low as α = 1.04 [16].

Figure 2.

HPLC or gas chromatography (GC) separation of alkyl chain alcohol derivatives (a)–(c).

In contrast, as shown in Figure 1, MαNP esters 3a and 3b were more effectively separated, indicating that MαNP acid is especially useful for such separation. Therefore, our first purpose is to develop chiral molecular tools such as MαNP acid for effective diastereomers separation by HPLC on silica gel, and then to obtain enantiopure compounds from the separated diastereomers, as will be explained in this review article.

There is another resolution method where diastereomeric ionic crystals, e.g., acid/amine, or inclusion complex crystals are fractionally recrystallized to separate diastereomers. If good crystals are obtained, the method is useful for separation on a large scale. However, the separated crystals are not always diastereomerically pure, despite many crystallizations. If so, it is difficult to obtain enantiopure target compounds. This is the reason why we have not used the ionic crystals or inclusion crystals, but selected covalently bonded diastereomers such as esters or amides, to which HPLC on silica gel is applicable for separation and further purification.

Our second purpose is to determine the absolute configuration (AC). It is well known that the X-ray Bijvoet method [17] using the heavy atom effect, the circular dichroism (CD) exciton chirality method [18], and the recent density functional theory (DFT) molecular orbital calculation [19] are all very useful as non-empirical methods of AC determination. There is another category of AC determination where the relative configuration against the internal reference of AC could be determined by X-ray crystallography and/or 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy methods [6,7,8,9,10,11]. If single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction are available and the final Oak Ridge thermal ellipsoid plot (ORTEP) drawing is obtained, it is very easy to determine the AC of the part in question, based on the AC of the internal reference. This X-ray internal reference method is the most straightforward and reliable.

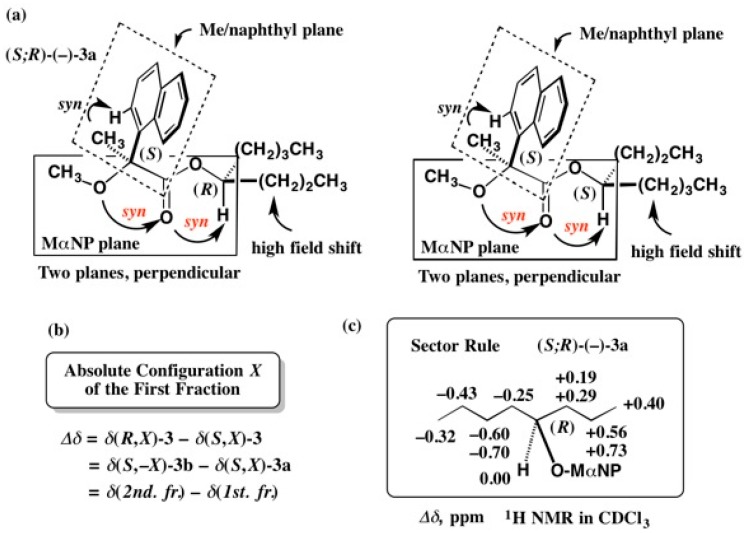

Another relative method is the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method, that is explained in Figure 3 [13]. The first-eluted MαNP ester (−)-3a and the second-eluted ester (−)-3b take the preferred conformations as shown in Figure 3a. In ester (−)-3a, the propyl group is located above the naphthyl group plane, and hence the protons of the propyl group feel the diamagnetic anisotropy effect leading to a high-field shift. On the other hand, in ester (−)-3b, the butyl group protons are placed above the naphthalene ring, leading to a high-field shift. The diamagnetic anisotropy effect (∆δ) is defined as shown in Figure 3b, where X is the AC of the first-eluted ester (−)-3a to be determined. The ∆δ values were calculated from the observed 1H-NMR spectra as shown in Figure 3c, where the propyl group showing positive ∆δ values is placed on the right side, while the butyl group giving negative ∆δ values is placed on the left side. By applying the present sector rule, the AC of the first-eluted MαNP ester (−)-3a was determined to be (R) [13].

Figure 3.

Determination of absolute configurations of 4-octanol MαNP esters (−)-3a and (−)-3b by 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy: (a) Preferred conformations; (b) Definition of Δδ value; (c) Sector rule. Redrawn with permission from [13].

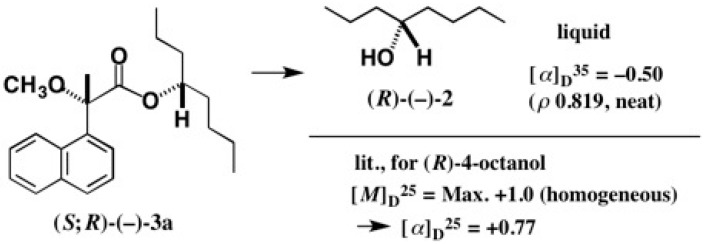

The first-eluted ester (−)-3a was hydrolyzed with KOH/MeOH yielding enantiopure 4-octanol (R)-(−)-2 (yield 70%), whose specific rotation value was negative: = −0.50 (ρ = 0.819, neat) (Figure 4) [13]. To compare with the reported data, we checked the literature, and found only one paper, reported in 1936, where (R)-AC was assigned to 4-octanol (+)-2 (Figure 4) [20]. Namely, the AC assignment was opposite to ours. It was a time before the discovery of the unambiguous AC determination by the X-ray Bijvoet method [17] using the anomalous scattering effect of heavy atoms, and hence the AC assignment in 1936 would be unreliable. Thus, we have first unambiguously determined the (R)-AC of 4-octanol (−)-2.

Figure 4.

Recovery of enantiopure 4-octanol (R)-(−)-2 and its optical rotation data. The literature data: value from [20]; value estimated from by us.

We have developed powerful chiral molecular tools suitable for the HPLC separation of diastereomers and also for the determination of ACs. The development and application examples of the methods using these chiral molecular tools will be explained in the following sections.

2. Use of (−)-Camphorsultam for Carboxylic Acids

2.1. Application to Spiro[3.3]Heptane-Dicarboxylic Acids

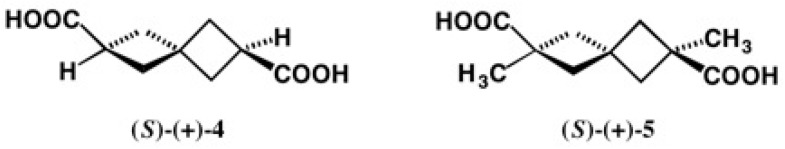

Fecht acid 4 is a unique dicarboxylic acid with spiro[3.3]heptane skeleton (Figure 5). However, it has protons at the α-positions of carboxylic acid groups, and hence it may be unstable under basic conditions. To prevent such a possibility, we designed a Fecht acid analog, 2,6-dimethyl-spiro[3.3]heptane-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (5) in which the α-positions are blocked by methyl groups (Figure 5) [21].

Figure 5.

Absolute configurations of Fecht acid (+)-4 and analog (+)-5.

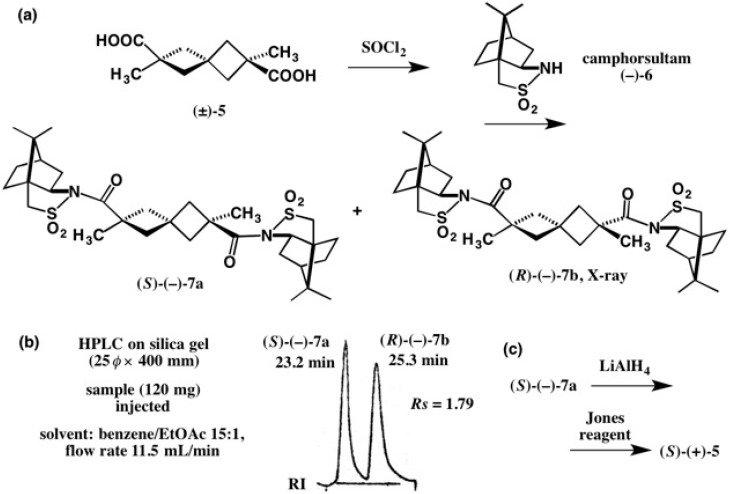

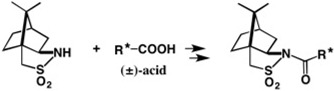

To make the chiral resolution of acid 5, we have tried the HPLC separation of diastereomeric amides formed from chiral amines, such as (S)-(−)-α-phenylethylamine, (S)-(−)-α-naphthylethyl-amine, and (+)-dehydroabietylamine, but all attempts were unsuccessful. Finally, we have found that (−)-camphorsultam 6 was useful as shown in Figure 6. Racemic acid (±)-5 was converted into the acid chloride, which was then treated with camphorsultam (−)-6/NaH. The obtained diastereomeric mixture (7a/7b) was well separated by HPLC on silica gel (resolution factor Rs = 1.79) (Figure 6b) [21]. Since the sample (120 mg) was separable in one run, this method is good for the preparation of enantiopure target compounds on a laboratory scale. We have a question why camphorsultam amides 7a and 7b are more easily separable by HPLC on silica gel than the other amides described above. The author considers that the polar SO2 moiety strongly interacts with silica gel.

Figure 6.

Preparation of diastereomeric amides 7a and 7b (a), separation by HPLC on silica gel (b), and recovery of acid (S)-(+)-5 (c). HPLC, redrawn from [22].

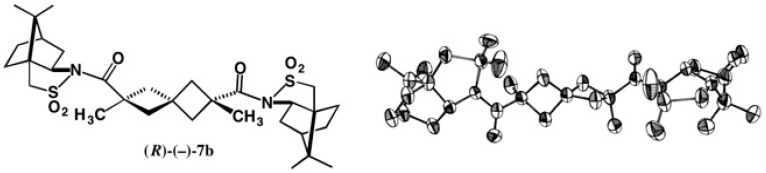

The second-eluted amide (−)-7b was recrystallized from EtOAc giving prisms suitable for X-ray analysis. The diffraction measurements were performed with Cu Kα X-ray giving the ORTEP drawing as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

X-ray ORTEP drawing of amide (R)-(−)-7b. Reprinted from [21].

The X-ray final R value (resudual factor) was 0.0581 for the (R)-AC shown, while that of the mirror image was 0.0650. Therefore, the (R)-AC was assigned to amide (−)-7b by the X-ray heavy atom effect of the sulfur atom contained in the camphorsultam unit. In addition, the (R)-AC of the 2,6-dimethyl-spiro[3.3]heptane-2,6-dicarboxylic acid unit was confirmed by using the camphor- sultam groups as the internal reference of AC. Thus, the AC of the dicarboxylic acid moiety in amide (−)-7b was doubly determined by X-ray crystallography; this is a great advantage of the camphorsultam method [21].

To cleave the amide C–N bond, the first-eluted amide (S)-(−)-7a was reduced with LiAlH4 yielding a bis(primary alcohol), which was then oxidized with the Jones reagent, affording dicarboxylic acid (S)-(+)-5 (Figure 5 and Figure 6c). The camphorsultam method is thus very useful for the preparation of enantiopure carboxylic acids and also for determining their ACs [21].

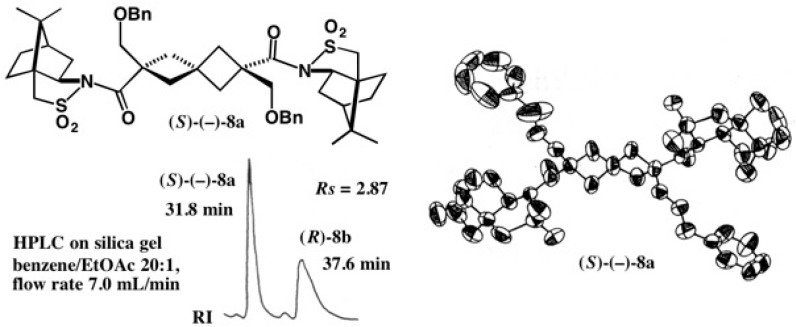

The related diastereomers 8a and 8b with benzyloxy groups were largely separated by HPLC on silica gel (Figure 8). It should be emphasized that these bis-amides appeared as clearly separated two spots even on a 5 cm thin layer chromatography (TLC) plate of silica gel. The first-eluted amide (−)-8a was recrystallized from EtOAc giving prisms, one of which was subjected to X-ray analysis [23]. From the ORTEP drawing, its (S) absolute configuration was established as shown. Amide (S)-(−)-8a was then converted to dicarboxylic acid (S)-(+)-5 (Figure 5).

Figure 8.

HPLC separation of camphorsultam amides 8a and 8b, and an X-ray ORTEP drawing of the first-eluted amide (S)-(−)-8a. HPLC, redrawn from [24]. X-ray ORTEP drawing, reprinted with permission from [23].

2.2. Application to Cyclophane-Carboxylic Acids

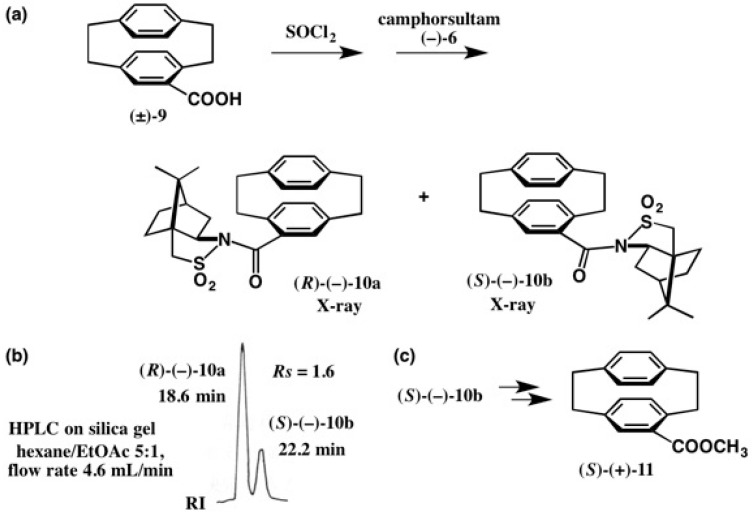

The camphorsultam method was useful for the preparation of enantiopure cyclophane compounds with a plane chirality, and also for the direct and clear-cut determination of their ACs. In 1970, Schloegl and coworkers reported the AC of [2.2]paracyclophane-4-carboxylic acid 9 [25]. Acid 9 was enantiomerically enriched by the kinetic resolution of its anhydride with (−)-phenyl-ethylamine, where (S)-AC was empirically assigned to acid (+)-9. Furthermore, the (R)-AC of acid (−)-9 was also determined by applying the empirical Horeau’s rule to related compounds. However, the AC of acid 9 was later involved in a controversy in relation to the AC determination of other paracyclophane compounds. Therefore, it was necessary to determine its AC in a non-empirical manner (Figure 9) [23].

Figure 9.

Preparation of diastereomeric amides 10a and 10b (a), separation by HPLC on silica gel (b), and preparation of ester (S)-(+)-11 (c). HPLC, redrawn from [24].

Racemic acid (±)-9 was converted to the acid chloride, which was then treated with camphorsultam (−)-6/NaH (Figure 9) [23]. The obtained diastereomeric mixture of amides 10a and 10b was separated by HPLC on silica gel as shown in Figure 9b. The second-eluted amide (−)-10b had a good crystallinity, and so it crystallized before HPLC. Thus, by combining recrystallization and HPLC separation, diastereomeric amides 10a and 10b were completely separated.

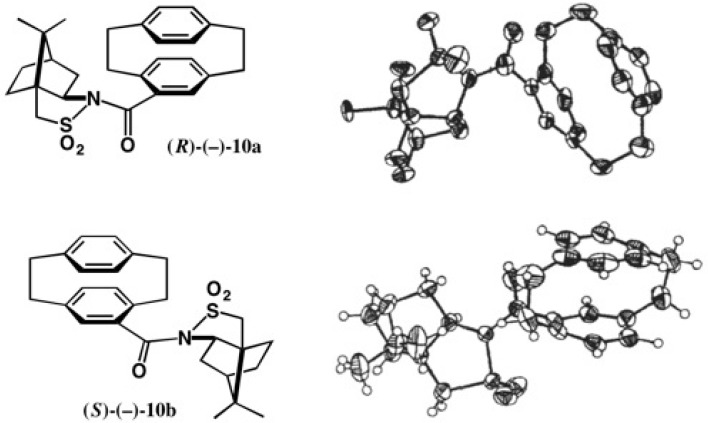

The second-eluted amide 10b was recrystallized from EtOAc yielding prisms suitable for X-ray. Based on the AC of the camphorsultam part in the ORTEP drawing, the AC of the cyclophane moiety in (−)-10b was unambiguously determined to be (S) (Figure 10), which was corroborated by the anomalous scattering effect of the sulfur atom (real image, R = 0.0299; mirror image, R = 0.0348) [23]. The first-eluted amide (−)-10a was recrystallized from MeOH giving prisms; X-ray analysis revealed that one asymmetric unit contained two independent molecules, and hence the final R value remained large. Therefore, it was difficult to determine the AC by the heavy atom effect, because of the small difference between final R values (R = 0.1226 for the real image and R = 0.1239 for its mirror image). However, by using the camphorsultam unit as an internal reference of AC, the (R)-AC of (−)-10a was clearly determined as shown in Figure 10. Finally, amide (S)-(−)-10b was converted to methyl ester (S)-(+)-11 (Figure 9c). The ACs of [2.2]paracyclophane-4-carboxylic acid 9 and related compounds were thus unambiguously determined [23].

Figure 10.

X-ray ORTEP drawings of camphorsultam amides (R)-(−)-10a and (S)-(−)-10b. Reprinted with permission from [23].

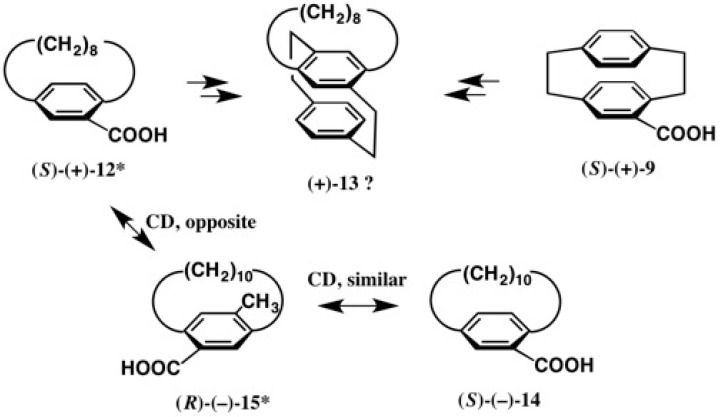

There had been conflicting reports concerning the ACs of [8]paracyclophane-10-carboxylic acid 12, [10]paracyclophane-12-carboxylic acid 14, and a related compound 15 (Figure 11). In 1972, Schloegl and a coworker determined the AC of [10]paracyclophane-12-carboxylic acid 14 as follows [26]. As in the case of [2.2]paracyclophane-4-carboxylic acid 9, acid 14 was enantiomerically enriched by the kinetic resolution of its anhydride with (−)-phenylethylamine, where (S)-AC was empirically assigned to acid (−)-14. Furthermore, the (S)-AC of acid (−)-14 was also determined by applying the empirical Horeau’s rule to related compounds.

Figure 11.

Absolute configurations (ACs) of chiral paracyclophane-carboxylic acids assigned by chemical correlation and comparison of circular dichroism (CD) spectra, where the ACs designated with an asterisk * were reversed, as will be explained below. The AC of compound (+)-13 has remained unclear. Redrawn with permission from [30].

On the other hand, in 1974–1977, Nakazaki and coworkers reported the synthesis of a unique compound, (+)-[8]bridged [2.2]paracyclophane 13, and related compounds starting from [8]para-cyclophane-10-carboxylic acid (+)-12 (Figure 11) [27]. The ACs of these compounds were determined by chemical correlation with [2.2]paracyclophane-4-carboxylic acid (S)-(+)-9, where chemical reactions of many steps were performed. So, the (S)-AC was assigned to acid (+)-12. The CD spectrum of acid (S)-(+)-[CD(+)248]-12 was almost a mirror image of that of 15-methyl-[10]paracyclophane-12-carboxylic acid (R)-(−)-[CD(−)245]-15 [27]. On the other hand, the CD of [10]paracyclophane-12-carboxylic acid (S)-(−)-[CD(−)239]-14 reported by Schloegl was similar including a sign to that of acid (−)-15 despite their opposite ACs (Figure 11) [26]. Thus, these AC assignments were clearly in conflict with each other [28,29]. To solve these problems, we have applied a more unambiguous method, i.e., the camphorsultam method, as explained below [30].

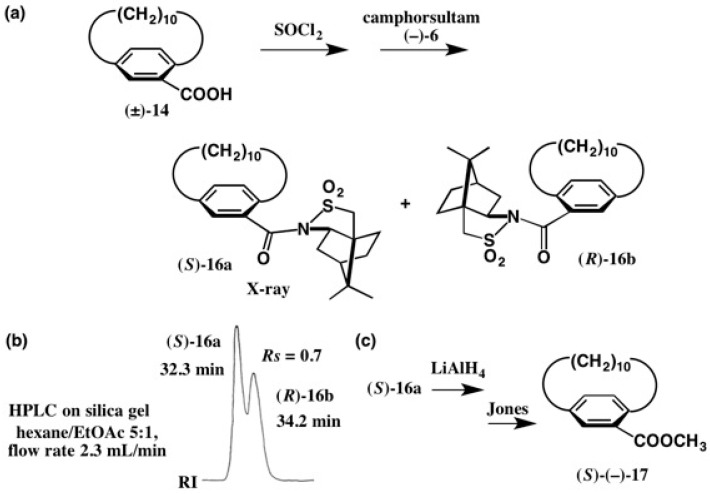

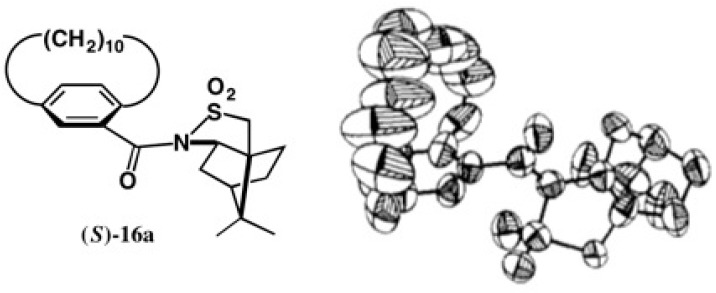

Racemic [10]paracyclophane-12-carboxylic acid, (±)-14 was converted to the acid chloride which was then treated with camphorsultam (−)-6/NaH (Figure 12). The obtained diastereomeric mixture of amides 16a and 16b was separated by HPLC on silica gel as shown in Figure 12b, where two peaks partially overlap with each other. So, HPLC separation was repeated twice to obtain pure diastereomers [30].

Figure 12.

Preparation of diastereomeric amides 16a and 16b (a), separation by HPLC on silica gel (b), and preparation of methyl ester (S)-(−)-17 (c). HPLC, redrawn from [24].

The second-eluted amide 16b had a good crystallinity, and it was recrystallized from MeOH giving prisms. However, X-ray experiments indicated that the asymmetrical unit contained three independent molecules, and hence it was difficult to continue the X-ray analysis. The first-eluted amide 16a was similarly recrystallized from MeOH giving plate crystals. Although the asymmetrical unit contained two independent molecules, it was possible to obtain the crystal structure as shown in Figure 13 [30].

Figure 13.

X-ray ORTEP drawing of amide (S)-16a. Reprinted with permission from [30].

As seen in the ORTEP drawing, the methylene chain showed large thermal vibration and/or disorder, and so the final R value remained large (R = 0.1119 for the real image and R = 0.1122 for mirror image). Thus, it was impossible to determine the AC by the anomalous scattering effect of the sulfur atom. However, it was easy to assign the (S)-AC of the paracyclophane part from the ORTEP drawing, because the AC of the camphorsultam unit was already known. The first-eluted amide (S)-16a was converted to methyl ester (S)-(−)-[CD(−)238.2]-17 [30], the CD data of which were similar to those of acid (−)-14 [26]. This X-ray result was consistent with the (S)-AC of acid (−)-14 previously assigned by the empirical methods [26].

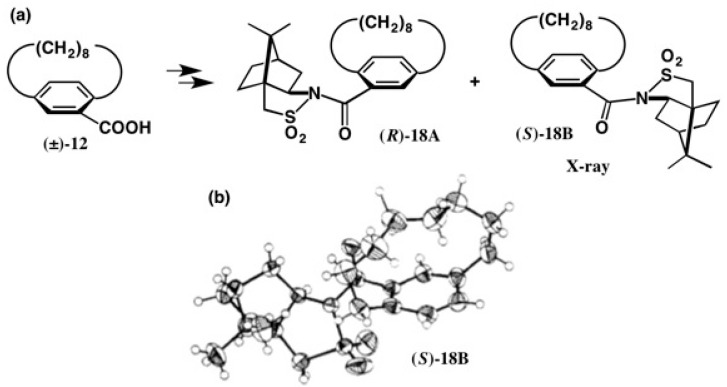

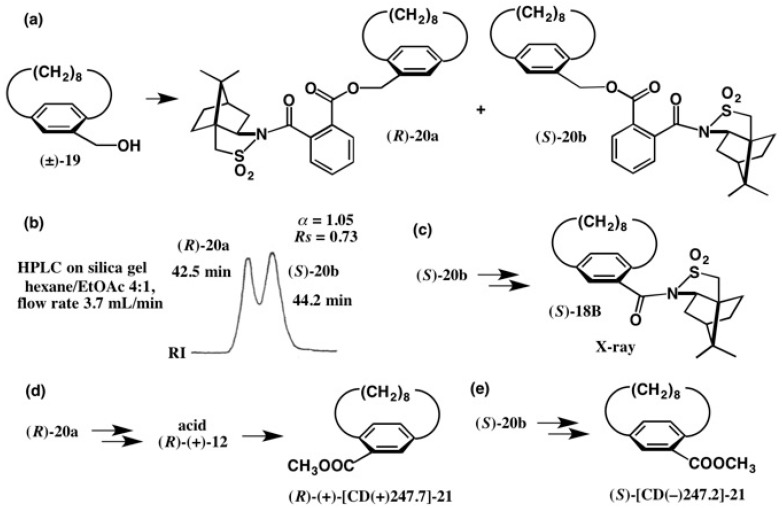

Next, the camphorsultam method was applied to [8]paracyclophane-10-carboxylic acid 12. Racemic acid (±)-12 was converted to diastereomeric amides 18A and 18B (Figure 14), which were subjected to HPLC, but unfortunately the amides could not be separated. (Please note that in compounds 18A and 18B, the capital letters A and B do not indicate HPLC elution order, just meaning two diastereomers). So, the fractional recrystallization from MeOH was applied, giving amide 18B as plate single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography. The ORTEP drawing of amide 18B was obtained as shown in Figure 14b. The (S)-AC of 18B was determined by the heavy atom effect (R = 0.0441 for the real image and R = 0.0538 for its mirror image). This assignment was also corroborated by the internal reference method of camphorsultam [30].

Figure 14.

Preparation of amides 18A and 18B (a), and the X-ray ORTEP drawing of camphorsultam amide (S)-18B (b). Reprinted with permission from [30].

The amount of amide 18B obtained by recrystallization was limited, and so we adopted the method of camphorsultam-phthalic acid (CSP acid) (−)-22 (see Figure 16), which had been developed by us for the chiral resolution of alcohols, as will be discussed in the next section. Racemic [8]paracyclophane-10-methanol (±)-19 was esterified with (−)-CSP acid 22, yielding diastereomeric esters 20a and 20b (Figure 15a), which were not base-line separated in HPLC, as shown in Figure 15b [30]. However, by repeating HPLC, it was possible to separate them completely. Next, we tried the recrystallization of the obtained esters from various solvents, but in all cases both esters were obtained as fine needles, which were unsuitable for X-ray analysis. So, to determine the ACs of these compounds, the second-eluted ester 20b was converted to camphorsultam amide, which was identical to amide (S)-18B (Figure 15c). The (S)-AC of 18B was clearly determined by X-ray analysis as shown in Figure 14. So, the ACs of esters 20a and 20b were determined to be (R) and (S), respectively [30].

Figure 16.

Chiral (−)-CSP and (−)-CSDP acids useful for alcohols.

Figure 15.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of esters 20a and 20b, which were then converted to methyl esters (R)-(+)-21 (d) and (S)-21 (e), respectively. Ester 20b was converted to amide 18B (c), by which the ACs of these compounds were established. HPLC, redrawn from [24].

The first-eluted ester (R)-20a was converted to [8]paracyclophane-10-carboxylic acid (R)-(+)-12 and then to the methyl ester (R)-(+)-[CD(+)247.7]-21 (Figure 15d). The second-eluted ester (S)-20b was similarly converted to methyl ester (S)-[CD(−)247.2]-21. These results clearly indicated that the (S)-AC of [8]paracyclophane-10-carboxylic acid (+)-12 previously assigned by chemical correlations requiring many steps was wrong and should be reversed (Figure 11) [30]. In addition, the AC of acid (−)-15 was also reversed (Figure 11). Thus, it should be emphasized that to determine the ACs of chiral compounds, it is necessary to select more straightforward and reliable methods as exemplified here.

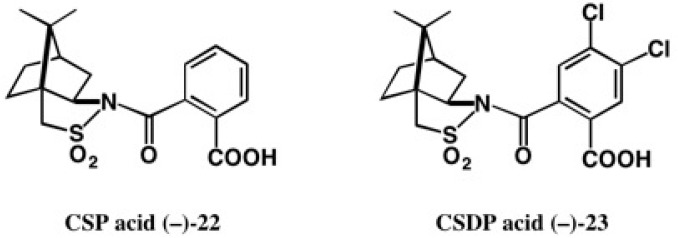

3. Use of Camphorsultam-Phthalic Acid (CSP Acid) for Alcohols—The CSP Acid Method

Application to Alcohols with an Aromatic Group

(−)-Camphorsultam 6 was useful for the chiral resolution of racemic carboxylic acids and AC determination by X-ray crystallography, as explained in Section 2. The development of novel chiral molecular tools applicable to racemic alcohols was desired. For this purpose, we have developed novel chiral molecular tools, camphorsultam-phthalic acid (CSP acid) (−)-22 and camphorsultam-dichlorophthalic acid (CSDP acid) (−)-23 (Figure 16).

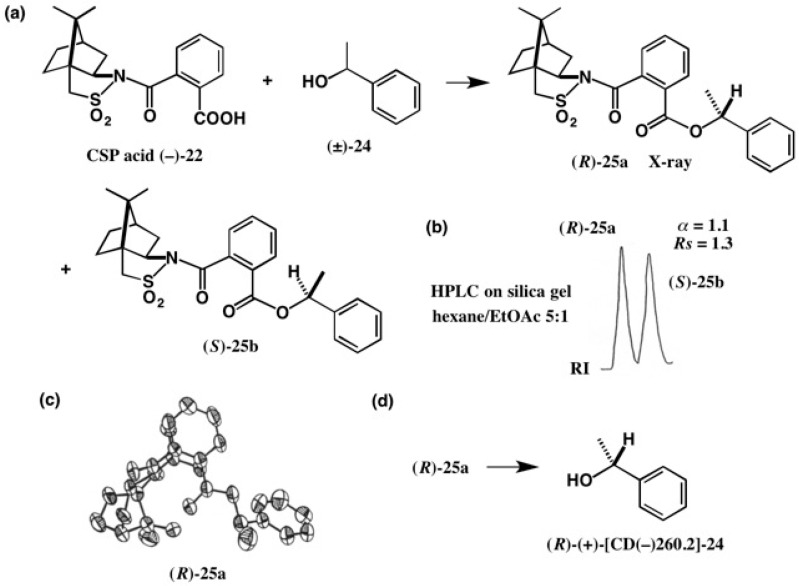

Camphorsultam-phthalic acid (−)-22 was easily prepared by treating phthalic anhydride with the camphorsultam anion. The CSP acid method was first applied to a simple alcohol, as shown in Figure 17 [31]. Racemic 1-phenylethanol (±)-24 was esterified with CSP acid (−)-24 yielding diastereomeric esters 25a and 25b, which were separated well by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.1, Rs = 1.3) (Figure 17b). The reason why we selected the phthalic acid as the connector between camphorsultam and acid moieties is that these two groups are close to each other, and hence the diastereomers are more different in stereochemistry and polarity, which would lead to larger separation in HPLC.

Figure 17.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of esters 25a and 25b, and the AC determination of ester (R)-25a by X-ray analysis (c). From ester (R)-25a, alcohol (R)-(+)-24 was obtained (d). HPLC, redrawn from [32]. ORTEP drawing, reprinted from [31].

The first-eluted ester 25a was recrystallized from MeOH giving prisms suitable for X-ray analysis. From the ORTEP drawing shown in Figure 17c, the AC of the 1-phenylethanol moiety was clearly determined as (R), because the AC of the CSP acid part was already known. The first-eluted ester (R)-25a was then converted to 1-phenylethanol (R)-(+)-24. The AC of the 1-phenylethanol previously assigned was thus corroborated by X-ray crystallography [31].

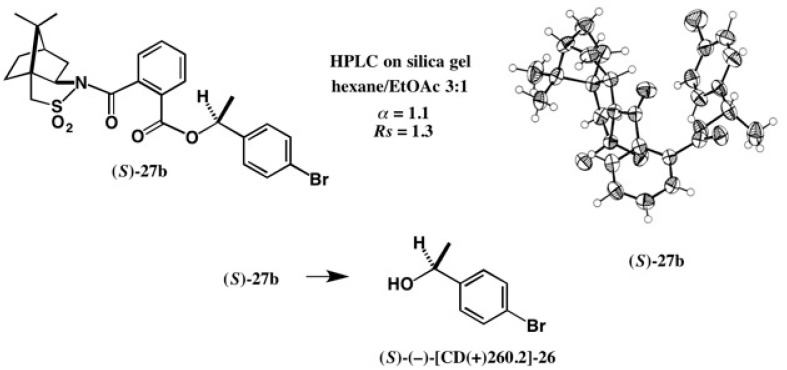

The CSP acid method was next applied to 1-(4-bromophenyl)ethanol 26 as shown in Figure 18 [31].

Figure 18.

Preparation and HPLC separation of esters 27a and 27b, and the AC determination of ester (S)-27b by X-ray analysis. From ester (S)-27b, alcohol (S)-(−)-26 was obtained. ORTEP drawing, reprinted from [31].

Racemic alcohol (±)-26 was esterified with CSP acid (−)-24 yielding diastereomeric esters 27a and 27b, which were similarly separated by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.1, Rs = 1.3). Both esters 27a and 27b were recrystallized from MeOH giving prisms. A single crystal of 27b was subjected to X-ray analysis giving the ORTEP drawing as shown in Figure 18, where the (S)-AC was unambiguously determined by the heavy atom effects of S and Br atoms (real image, R = 0.0352; mirror image, R = 0.0469). The (S)-AC was also confirmed by the internal reference method of AC using the camphorsultam unit. From ester 27b, alcohol (S)-(−)-[CD(+)260.2]-26 was recovered. The AC of alcohol 26 was thus established by X-ray crystallography [31].

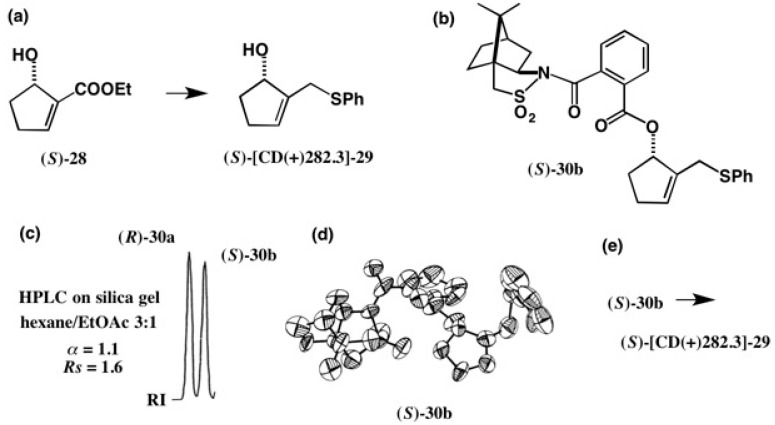

The enzymatic method is also useful for the chiral resolution of racemates. For example, alcohol 28 was resolved by treating its racemic acetate with the lipase PS yielding chiral alcohol 28, from which a chiral synthon 29 was prepared. However, the enantiomeric excess (ee) and AC of these compounds remained undetermined. So, the CSP acid method was applied to alcohol 29 as shown in Figure 19 [31].

Figure 19.

Preparation (a,b) and HPLC separation (c) of esters 30a and 30b, and the AC determination of ester (S)-30b by X-ray analysis (d). From ester (S)-30b, alcohol (S)-[CD(+)282.3]-29 was obtained (e). HPLC, redrawn from [32]. ORTEP drawing, reprinted from [31].

The CSP esters 30a and 30b were almost baseline separated as shown in Figure 19c (α = 1.1, Rs = 1.6). The X-ray analysis of ester 30b gave the ORTEP drawing (Figure 19d), where the final R value remained as high as R = 0.146 because of the poor crystallinity of ester 30b. Therefore, its AC could not be determined by the heavy atom effect, but easily determined by the internal reference method of camphorsultam to be (S). Finally, ester (S)-30b was converted to alcohol (S)-[CD(+)282.3]-29, where [CD(+)282.3] indicates the enantiomer showing a positive CD Cotton effect at 282.3 nm [31]. To specify an enantiomer, CD data are useful because the CD measurements need a smaller amount of sample than that for the measurement.

4. Camphorsultam-Dichlorophthalic Acid (CSDP Acid) for Alcohols—The CSDP Acid Method

As exemplified above, the CSP acid method is useful for the chiral resolution of racemic alcohols and the determination of ACs by X-ray crystallography. However, HPLC separation of diastereomeric CSP esters was not always effective, and in some cases, CSP esters crystallized as fine needles, which were not suitable for X-ray analysis. So, to improve the performance of the CSP acid method, we have explored the structure of chiral acids, and have found that the camphorsultam dichlorophthalic acid (CSDP acid) (−)-23 (Figure 16) was much more useful than CSP acid (−)-22.

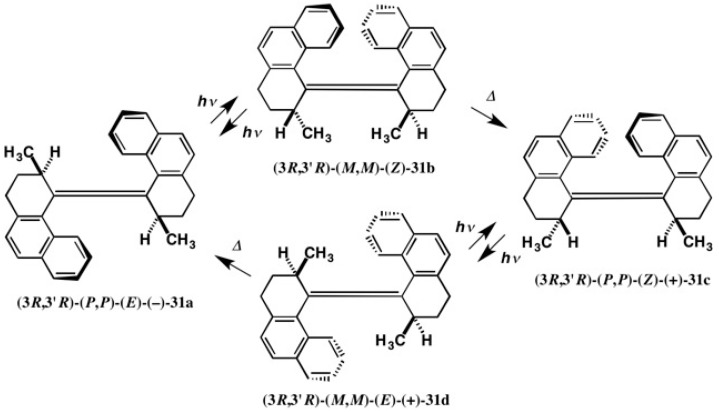

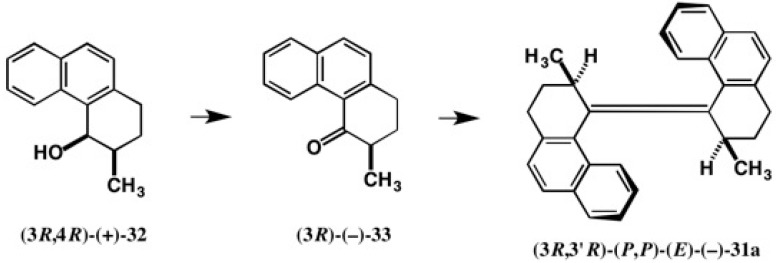

4.1. Synthesis of Chiral Molecular Motor

Molecular machines are very interesting and attractive as future mechanical machines of molecular scale. We have developed the light–powered molecular motor 31a–31d [33,34,35,36] as shown in Figure 20 [37], where trans-olefin 31a isomerizes to cis-olefin 31b under photo-irradiation. In this step, the left naphthalene moiety rotates counter-clockwise against the right naphthalene moiety. Furthermore, thermally unstable cis-olefin 31b is converted to thermally stable cis-olefin 31c, where the left naphthalene group again rotates counter-clockwise against the right naphthalene group. This thermal step is irreversible, although the photo-isomerization step is reversible, and hence in the steps, trans-olefin 31a → cis-olefin 31b → cis-olefin 31c, the rotation occurs in a counter- clockwise manner [36,37].

Figure 20.

Light-powered molecular motor 31 and rotation mechanism, where 31a–31d are rotation isomers. Redrawn with permission from [37].

Similarly, cis-olefin 31c isomerizes to thermally unstable trans-olefin 31d under photo-irradiation (Figure 20). In this step, the left naphthalene moiety again rotates counter-clockwise against the right naphthalene moiety. Furthermore, trans-olefin 31d is converted to thermally more stable trans-olefin 31a, where the left naphthalene group again rotates counter-clockwise against the right naphthalene group. This thermal step is again irreversible, although the photo-isomerization step is reversible, and hence the rotation occurs in a counter-clockwise manner in the steps, cis-olefin 31c → trans-olefin 31d → trans-olefin 31a. The rotation occurs only in a counter-clockwise manner [36,37].

It should be emphasized that molecular motor 31 undergoes the photo and thermal reactions 31a → 31b → 31c → 31d → 31a, where the left naphthalene group rotates counter-clockwise against the right naphthalene group. Therefore, by repeating these reactions, the molecular motor continuously rotates one-way [36,37]. It is obvious that the direction of motor rotation is governed by the molecular chirality, and hence it is important to synthesize the enantiopure molecular motor 31 and also to determine its absolute configuration in an unambiguous manner.

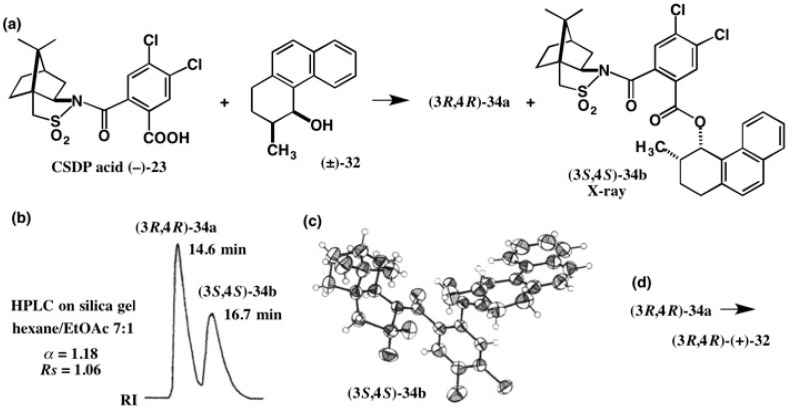

The molecular motor 31a was synthesized in an enantiopure form, starting from alcohol (3R,4R)-(+)-32 as shown in Figure 21 [33]. To obtain enantiopure alcohol 32 and to determine its AC, racemic cis-alcohol (±)-32 was esterified with CSP acid (−)-22, and the obtained diastereomeric CSP esters were separated by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.10). However, both CSP esters were obtained as fine needles or an amorphous solid. Hence their ACs could not be determined. So, we applied the new CSDP acid method, as shown in Figure 22 [33,38].

Figure 21.

Synthesis of a chiral light-powered molecular motor (3R,3′R)-(P,P)-(E)-(−)-31a starting from alcohol (3R,4R)-(+)-32.

Figure 22.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of esters 34a and 34b, and the AC determination of ester 34b by X-ray analysis (c). From ester (3R,4R)-34a, alcohol (3R,4R)-(+)-32 was obtained (d). Redrawn from [38].

Racemic cis-alcoho l (±)-32 was esterified with CSDP acid (−)-23, yielding diastereomeric CSDP esters, which were separated well by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.18, Rs = 1.06) [38]. Thus, the HPLC separation of CSDP esters was better than that of CSP esters. Furthermore, the second-eluted CSDP ester 34b was obtained as colorless prisms by recrystallizing from EtOAc, and hence the AC of CSDP ester 34b could be determined to be (3S,4S) by X-ray crystallography using the heavy atom effects of S and the two Cl atoms (real image, R = 0.0287; mirror image, R = 0.0448). The (3S,4S) AC was also confirmed by the internal reference method of AC using the CSDP acid unit. Treatment of the first-eluted ester (3R,4R)-34a with LiAlH4 yielded the enantiopure alcohol (3R,4R)-(+)-32, from which molecular motor (−)-31a was synthesized as shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22 [33].

Motor compound (−)-31a was obtained as prisms by recrystallizing from MeOH, and a single crystal was subjected to X-ray crystallography. It was easy to determine the helicity of the molecular skeleton of (−)-31a to be (P,P) based on the AC of the methyl group position. Thus, the relative and absolute configurations of molecular motor (−)-31a were unambiguously determined to be (3R,3′R)-(P,P)-(E) [33].

4.2. Application to Diphenyl Methanols

The so-called asymmetric synthesis is very useful for the preparation of chiral compounds, as it is well known. However, there are some drawbacks in the asymmetric synthesis: (i) the products were not always enantiopure; (ii) the ACs were sometimes assigned in an empirical manner, e.g., comparison with the previous data of similar compounds, or assignment due to the asymmetric reaction mechanism. The next example emphasizes that the AC of products should be unambiguously determined by X-ray crystallography.

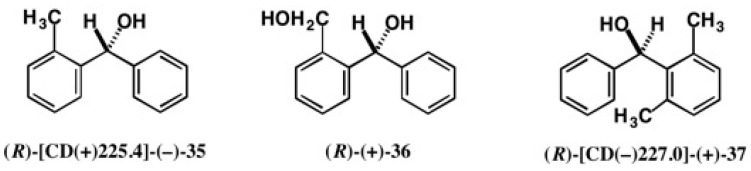

The AC of chiral alcohol 35, (2-methylphenyl)phenylmethanol had been a source of much confusion (Figure 23). In 1967, Cervinka and coworkers reported it to be (R)-(−) based on the asymmetric reductions [39]. However, in 1985, Seebach and coworkers assigned it to be (R)-(+) by catalytic asymmetric reactions [40]. Which assignment is correct? To solve this problem, we have applied the CSDP acid method as follows.

Figure 23.

ACs of chiral o-substituted diphenylmethanols.

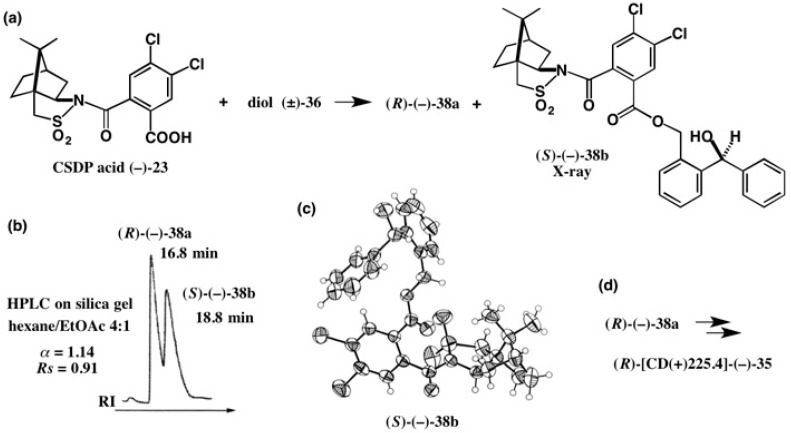

Racemic alcohol (±)-35 was esterified with CSDP acid (−)-23, yielding diastereomeric CSDP esters. However, the diastereomeric esters appeared as a single peak in HPLC on silica gel; they could not be separated at all. So, we have tested some synthetic precursors of alcohol 35, but all attempts were unsuccessful. Finally, we have found that diol 36 (Figure 23) could be separated as CSDP esters as shown in Figure 24 [41].

Figure 24.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of esters 38a and 38b, and the AC determination of ester (S)-(–)-38b by X-ray crystallography (c). Ester (R)-(–)-38a was converted to alcohol (R)-[CD(+)225.4]-(−)-35 (d). HPLC, redrawn from [42]. ORTEP drawing, reprinted with permission from [41].

Diol (±)-36 was esterified with CSDP acid (–)-23, yielding diastereomeric CSDP esters 38a and 38b, where the primary OH group was esterified. We had worried that the HPLC separation would become difficult, because in these esters the chiral groups in the CSDP acid moiety and alcohol part are remote from each other. However, the diastereomeric esters could be separated well by HPLC on silica gel, as shown in Figure 24b (α = 1.14, Rs = 0.91) [41].

The first-eluted ester, (−)-38a, was recrystallized from EtOH, giving prisms, one of which was subjected to X-ray analysis. However, it was found that the crystal was a twin, and hence it was unsuitable for X-ray crystallography. The second-eluted ester (−)-38b was similarly recrystallized from EtOH, giving single crystals, and the ORTEP drawing was obtained as shown in Figure 24c, where the (S)-AC was unambiguously determined by the Bijvoet method using one S and two Cl atoms (real image, R = 0.0324, Rw (weighted R-value) = 0.0415; mirror image, R = 0.0470, Rw = 0.0627). The (S)-AC was also corroborated by the internal reference method of AC using the CSDP acid unit. Starting from the first-eluted ester, (R)-(−)-38a, the desired alcohol (R)-[CD(+)225.4]-(−)-35 was synthesized (Figure 24d). Thus, the (R)-AC of alcohol (−)-35 has first been unambiguously determined by X-ray crystallography and chemical correlation [41]. It is again emphasized that the ACs of the asymmetric reaction products should be determined by an independent physical method such as X-ray crystallography.

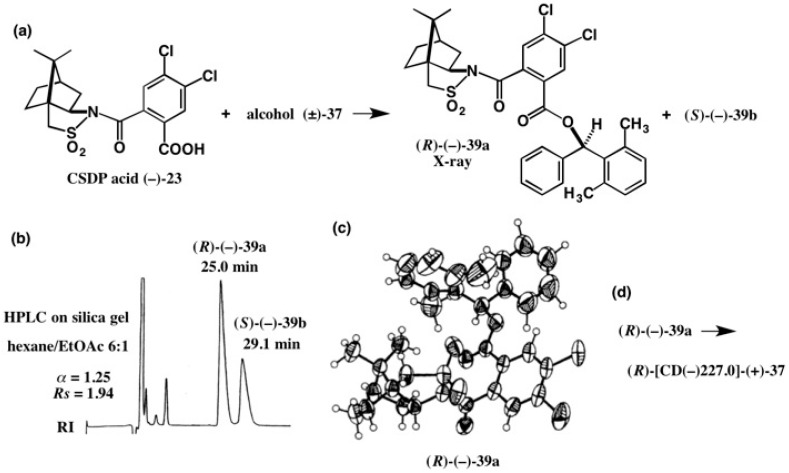

The next data provide the very interesting results and precautions for AC determination of similar and closely related compounds [43]. Chiral alcohol 37, (2,6-dimethylphenyl)phenyl- methanol (Figure 23), is similar in structure to (2-methylphenyl)phenylmethanol 35; the difference is one methyl or two methyl groups in the o-position. Therefore, we thought that the CSDP acid method would not be applicable to alcohol 37 directly, because CSDP esters of alcohol 35 could not be separated. However, it was surprising to find that CSDP esters 39a and 39b of alcohol 37 were base-line separated by HPLC on silica gel as shown in Figure 25b (α = 1.25, Rs = 1.94) [43].

Figure 25.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of esters 39a and 39b, and the AC determination of ester (R)-(−)-39a by X-ray crystallography (c). Alcohol (R)-[CD(−)227.0]-(+)-37 was recovered from ester (R)-(−)-39a (d). HPLC, redrawn from [44]. ORTEP drawing, reprinted from [43].

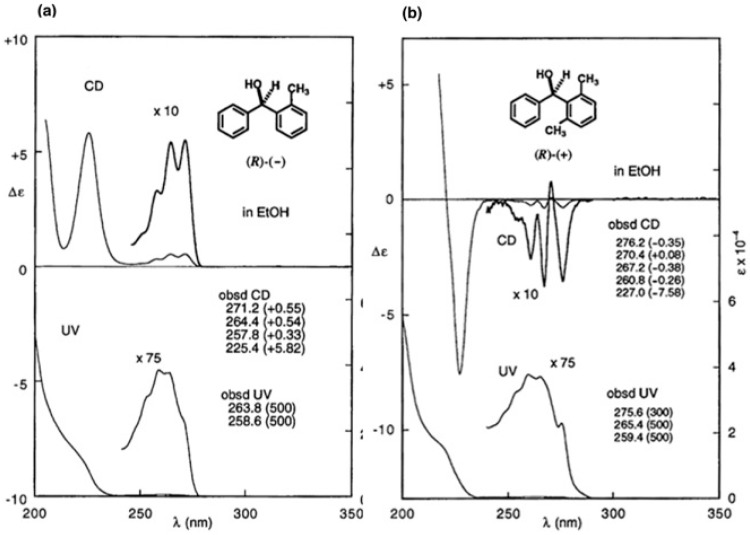

The first-eluted CSDP ester (−)-39a was converted to alcohol (+)-37, whose CD and UV spectra are shown in Figure 26b. It is interesting to see that the CD spectra of (2-methylphenyl)-phenylmethanol (R)-(−)-35 and (2,6-dimethylphenyl)phenylmethanol (+)-37 are similar in shape to each other, but opposite in sign (Figure 26). Therefore, we had once naturally thought that alcohol (+)-37 would have the opposite AC, i.e., (S)-AC. However, it was surprising to find that the comparison of CD spectra leads to an erroneous AC assignment in this case [43], as will be explained below.

Figure 26.

CD and UV spectra of o-substituted diphenylmethanols. (a) (2-methylphenyl)phenyl-methanol (R)-[CD(+)225.4]-(−)-35. Reprinted with permission from [41]; (b) (2,6-dimethylphenyl)-phenylmethanol (R)-[CD(−)227.0]-(+)-37. Reprinted from [43].

Later, we could obtain single crystals of the first-eluted ester (−)-39a by recrystallization from EtOH, and a crystal was subjected to X-ray crystallography. The ORTEP drawing is illustrated in Figure 25c, where (R)-AC was determined by the heavy atom effect (real image, R = 0.0358, Rw = 0.0488; mirror image, R = 0.0395, Rw = 0.0536) [43]. The (R)-AC was also confirmed by the internal reference method of AC using the CSDP acid unit. Since alcohol (+)-37 was obtained from the first-eluted CSDP ester (R)-(−)-39a, (R)-AC was assigned to alcohol (+)-37. Thus, we could find that the AC assignment by comparison of CD spectra led to erroneous conclusions in this case [43]. X-ray crystallography using an internal reference of AC is thus very powerful for clear AC determination.

4.3. Synthesis of a Cryptochiral Hydrocarbon

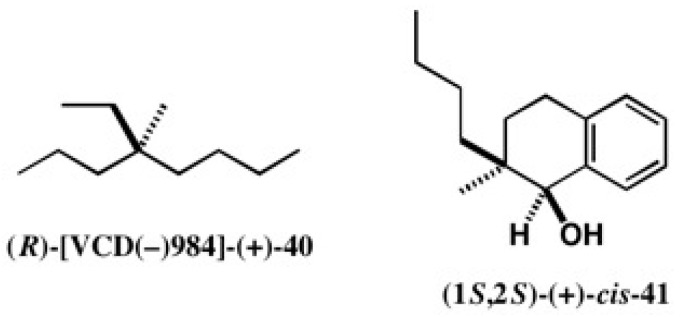

4-Ethyl-4-methyloctane 40 can exist as a basic and simple chiral hydrocarbon, where methyl, ethyl, propyl, and butyl groups are connected to a quaternary chiral center (Figure 27). Since the optical rotation value of 40 is very small as = +0.19 (neat), it may be called a cryptochiral hydrocarbon [45].

Figure 27.

Cryptochiral hydrocarbon (R)-[VCD(−)984]-(+)-40 and synthetic precursor (1S,2S)-(+)-cis-41.

In 1980, H. Wynberg and a coworker first synthesized chiral hydrocarbon (−)-40 (95% ee), but its AC could not be determined [46]. In 1988, L. Lardicci and coworkers reported the synthesis and determination of the AC of (+)-40, where they applied the CD exciton chirality method to acetylene tertiary alcohol benzoate for determining AC, but its observed CD was very weak (λext = 239 nm, ∆ε = +0.8) [47]. Therefore, it is difficult to say that the AC was unambiguously determined.

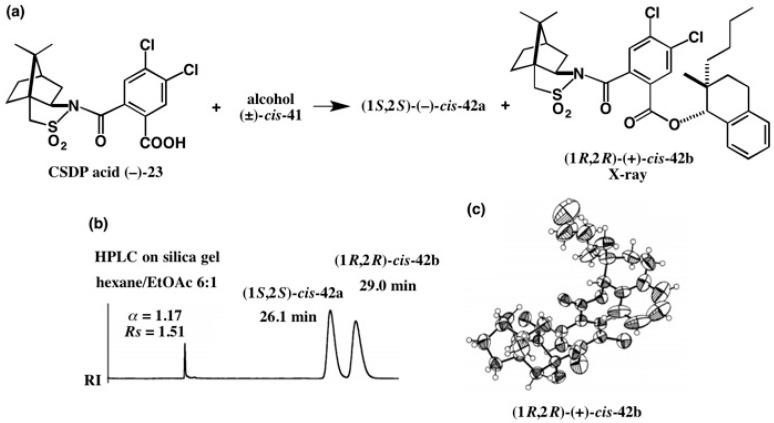

We selected the alcohol cis-41 as a synthetic precursor of hydrocarbon 40 (Figure 27). To obtain enantiopure alcohol cis-41 and to determine its AC, the CSDP acid method was applied, as shown in Figure 28 [45]. Racemic alcohol (±)-cis-41 was esterified with CSDP acid (−)-23, yielding diastereomeric esters 42a and 42b, which were baseline separated by HPLC on silica gel as shown in Figure 28b [45]. The second-eluted ester 42b was recrystallized from EtOH/CH2Cl2 giving single crystals, one of which was subjected to X-ray analysis. Figure 28c shows the ORTEP drawing of 42b, where AC was determined by the heavy atom effect (real image, R = 0.0598, Rw = 0.0740; mirror image, R = 0.0719, Rw = 0.0899). The (1R,2R)-AC of ester 42b was also established by the internal reference method of AC using the CSDP acid unit [45].

Figure 28.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of CSDP esters 42a and 42b, and the AC determination of ester (1R,2R)-(+)-cis-42b by X-ray crystallography (c). HPLC and ORTEP, reprinted with permission from [45].

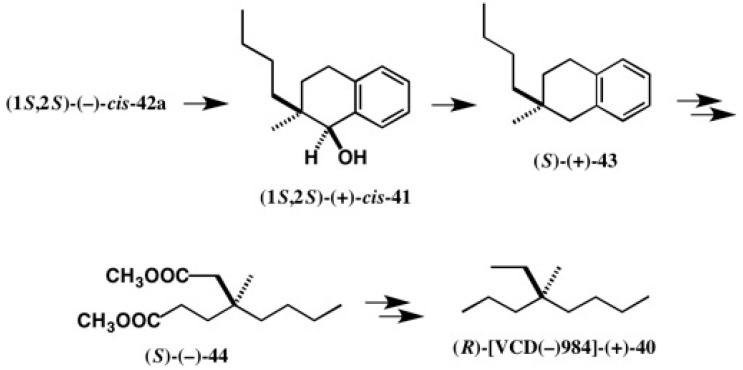

Starting from the first-eluted ester (1S,2S)-(−)-cis-42a, enantiopure cryptochiral hydrocarbon (R)-[VCD(−)984]-(+)-40 was synthesized as shown in Figure 29, where [VCD(−)984] indicates an enantiomer showing a negative vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) band at 984 cm−1 [45]. It should be noted that the (R)-AC of [VCD(−)984]-40 was also determined by the quantum mechanical calculation of VCD and IR, where the theoretically calculated VCD and IR spectra were compared with the observed spectra [48]. The theoretical AC determination was thus established in an experimental manner, as explained here.

Figure 29.

Synthesis of cryptochiral hydrocarbon (R)-[VCD(−)984]-(+)-40 starting from CSDP ester (1S,2S)-(−)-cis-42a.

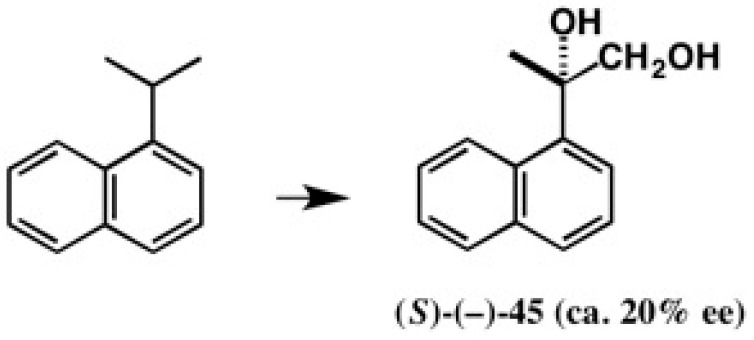

4.4. Application to 2-(1-Naphthyl)Propane-1,2-Diol

It was previously reported that 1-iso-propylnaphthalene was biotransformed in rabbits to 2-(1-naphthyl)propane-1,2-diol (S)-(−)-45 (Figure 30) [49]. However, its enantiomeric excess was very low (ca. 20% ee) and its AC was determined by chemical correlation to a compound, the AC of which had been determined by an empirical rule. Therefore, it was desired to obtain enantiopure diol 45 and to determine its AC in an unambiguous manner.

Figure 30.

Biotransformation of 1-iso-propylnaphthalene to 2-(1-naphthyl)propane-1,2-diol 45.

We have applied the CSDP acid method to racemic diol 45, as illustrated in Figure 31 [50]. Although these are CSDP esters of primary alcohols, where the chiral moiety of the alcohol part is far from that of the CSDP acid part, these diastereomers were largely separated by HPLC on silica gel (separation factor α = 1.27) [50]. This large α value indicates that esters 46a and 46b were more efficiently separated than the other CSDP esters discussed above. It may be due to the free OH group.

Figure 31.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of CSDP esters 46a and 46b. HPLC, reprinted from [42].

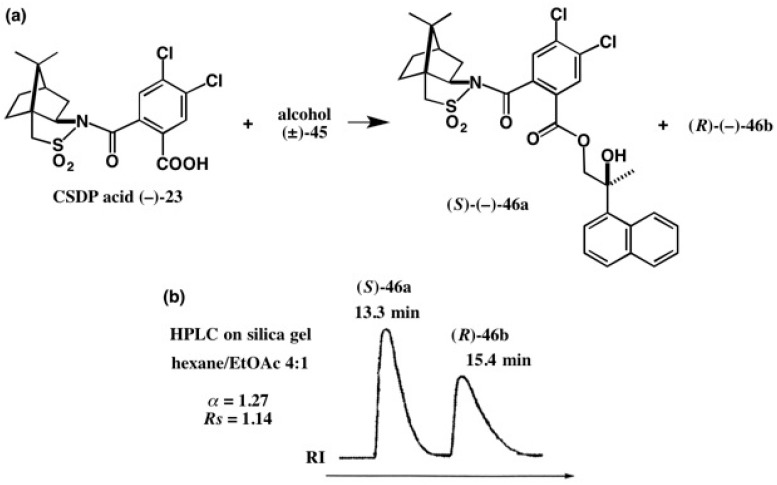

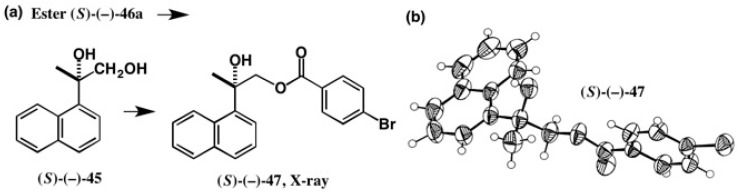

To obtain single crystals suitable for X-ray analysis, we tried to recrystallize these esters from various solvents, but all attempts were unsuccessful. So, we have adopted the following strategy, as shown in Figure 32 [50].

Figure 32.

Preparation (a) of p-bromobenzoate (S)-(−)-47 and its X-ray analysis (b). ORTEP drawing, reprinted from [50].

The reduction of the first-eluted ester 46a with LiAlH4 and successive benzoylation with p-Br-BzCl furnished p-bromobenzoate (−)-47, which was recrystallized from EtOH, giving good single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography. The ORTEP drawing of (−)-47 is shown in Figure 32b, where the (S)-AC was unambiguously determined by the original Bijvoet method. Namely, the 18 Bijvoet pairs were observed, and their observed intensity ratios agreed well with the calculated ratios [50]. In addition, the final R-value also indicated the (S)-AC (real image, R = 0.0249, Rw = 0.0342; mirror image, R = 0.0358, Rw = 0.0520). From these results, the (S)-AC of 2-(1-naphthyl)propane-1,2-diol (−)-45 was established.

5. Use of 2-Methoxy-2-(1-Naphthyl)Propionic Acid (MαNP Acid) for Alcohols—The MαNP Acid Method

5.1. Synthesis of Enantiopure MαNP Acid, HPLC Separation, and AC Determination by 1H-NMR Diamagnetic Anisotropy

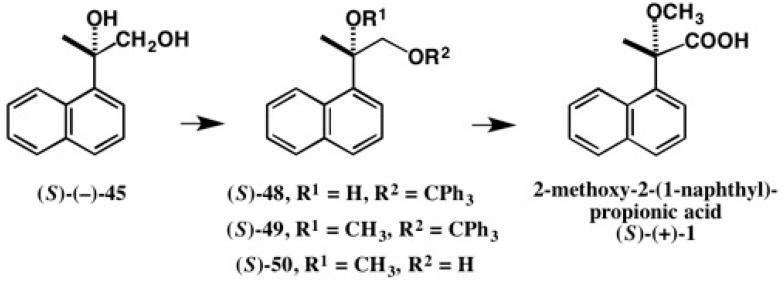

During the AC determination of diol (−)-45, we realized that it was possible to synthesize enantiopure 2-methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid 1, and the conversion was actually carried out as shown in Figure 33 [51]. Starting from enantiopure diol (S)-(−)-45, enantiopure 2-methoxy- 2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid (S)-(+)-1 was obtained, indicating that the (S)-AC of acid (+)-1 was established.

Figure 33.

Conversion of diol (S)-(−)-45 to 2-methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid (S)-(+)-1.

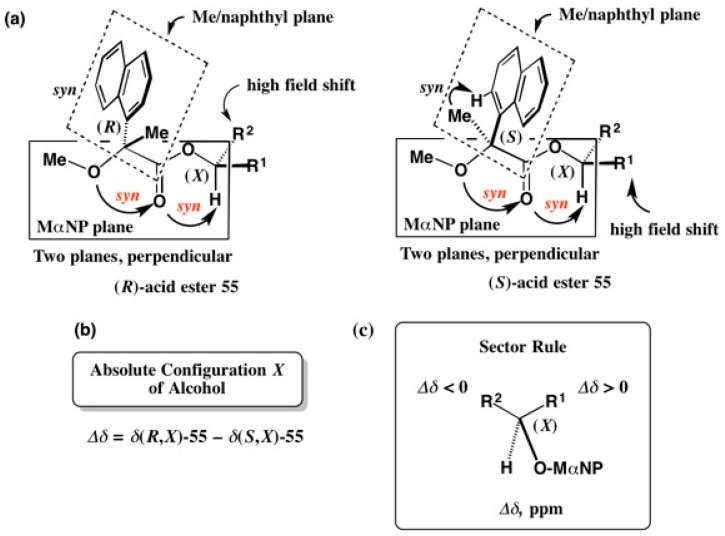

Chiral acid 1 is similar in structure to the Mosher’s α-methoxy-α-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetic acid (MTPA acid) 51 [52,53] and also to α-methoxyphenylacetic acid (MPA acid) 52 [54] (Figure 34). The NMR methods using these chiral acids have been widely employed for determining the ACs of various chiral secondary alcohols including natural products by using 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy shift data, although these methods are empirical rules. So, we had expected that acid 1 was also useful for determining the ACs of chiral secondary alcohols by the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method.

Figure 34.

Chiral acids useful for the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method.

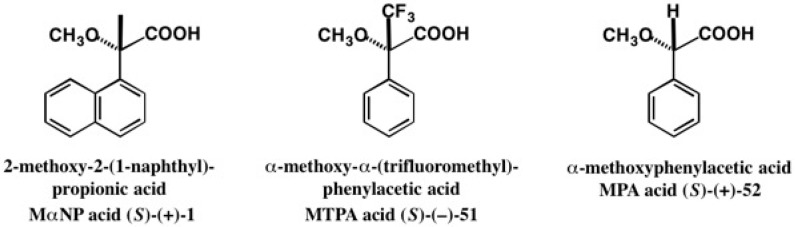

To employ as a chiral shift reagent, it was necessary to prepare enantiopure acid 1 on a large scale. So, we had looked for a simpler method to enantioresolve racemic acid (±)-1. It was surprising to find that natural menthol (−)-53 was very useful for the chiral resolution of racemic acid 1. Namely, racemic MαNP acid (±)-1 was reacted with menthol (−)-53 yielding diastereomeric esters 54a and 54b, which were largely separated by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.83, Rs = 2.26) (Figure 35) [51]. Such a large separation factor α has never been observed in the previous CSP and CSDP esters. The first-eluted ester (−)-54a was treated with NaOCH3 in MeOH and then with water yielding MαNP acid (+)-1, which was identical to acid (S)-(+)-1 shown in Figure 33. Therefore, the AC of the first-eluted ester (−)-54a was determined to be (S) [51].

Figure 35.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of menthol MαNP esters 54a and 54b. (c) Recovery of MαNP acid (S)-(+)-1 from the first eluted ester (−)-54a. HPLC, reprinted with permission from [51].

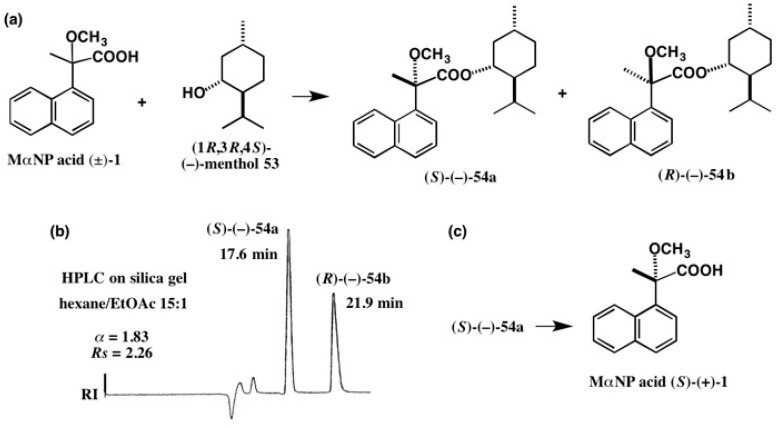

Figure 36 shows the AC determination of a secondary alcohol by the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method using (R)- and (S)-MαNP acids [55]. The (R)-acid ester 55 takes a preferred conformation as shown in Figure 36a, where the substituent R2 is located above the naphthalene ring, and hence it shows a high field shift.

Figure 36.

AC determination and mechanism of the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method using (R)- and (S)-MαNP acids. (a) Preferred conformation of MαNP esters; (b) Definition of Δδ; (c) Sector rule for determining the absolute configuration. Redrawn with permission from [55].

On the other hand, the (S)-acid ester 55 takes a similar preferred conformation, as shown in Figure 36a. However, the substituent R1 shows a high field shift because it is located above the naphthalene ring. The chemical shift difference ∆δ is defined as ∆δ = δ(R,X)-55 − δ(S,X)-55, where X denotes the AC of the alcohol part to be determined. From the observed 1H-NMR spectra, ∆δ values are calculated for each proton, and are plotted in the sector rule shown in Figure 36c, where the substituent R1 showing positive ∆δ values is placed on the right side. On the other hand, the substituent R2 showing negative ∆δ values is placed on the left side. Based on these data, the AC (X) of the alcohol part can be determined [55].

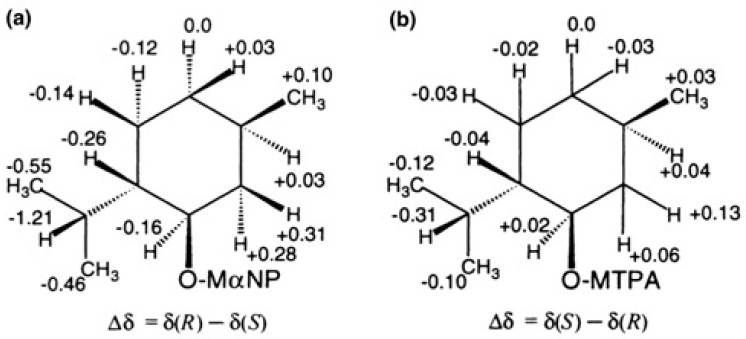

Figure 37a shows the distribution of ∆δ values of menthol MαNP esters (R)-(−)-54b and (S)-(−)-54a, where the isopropyl group showing negative ∆δ values is placed on the left side, while the methyl group showing positive ∆δ value is placed on the right side. Based on these data, the AC of (−)-menthol was determined as shown in Figure 35 [51]. Of course, this AC agreed with the previously established AC of (−)-menthol.

Figure 37.

Distribution of ∆δ values in ppm and AC determination. (a) Menthol MαNP esters and (b) menthol MTPA esters. Reprinted with permission from [51].

Figure 37b shows the distribution of ∆δ values of menthol MTPA esters. It should be noted that ∆δ is defined as ∆δ = δ(S,X) − δ(R,X). From the distribution of ∆δ values, the AC of (−)-menthol was assigned as shown. However, compared with the data of Figure 37a,b, the ∆δ values of MαNP esters are much larger than those of MTPA esters; ca. four times larger [51]. This is a great advantage of the MαNP ester method.

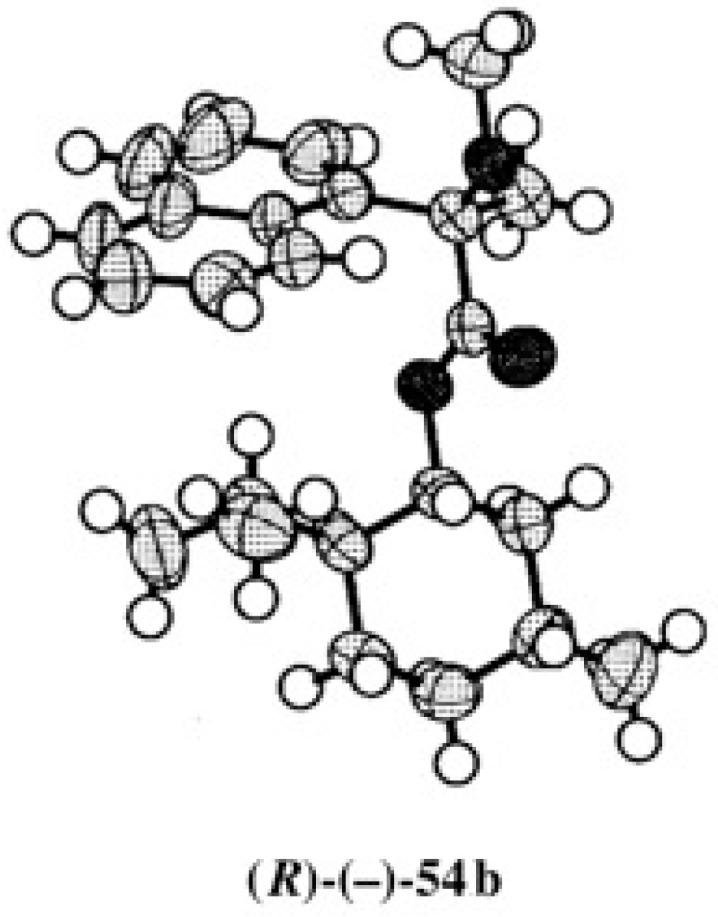

It was difficult to obtain single crystals of menthol MαNP esters 54a and 54b, although we had tried many recrystallizations from various solvents. Finally, we could obtain single crystals of ester (−)-54b suitable for X-ray analysis by recrystallizing from a mixed solvent (Et2O/MeOH). From the ORTEP drawing, the (R)-AC of the MαNP acid moiety was established (Figure 38) [56]. The chemical correlation, 1H-NMR spectra, and X-ray analysis are thus consistent with each other.

Figure 38.

X-ray ORTEP drawing of menthol MαNP ester (R)-(−)-54b. Reprinted with permission from [56].

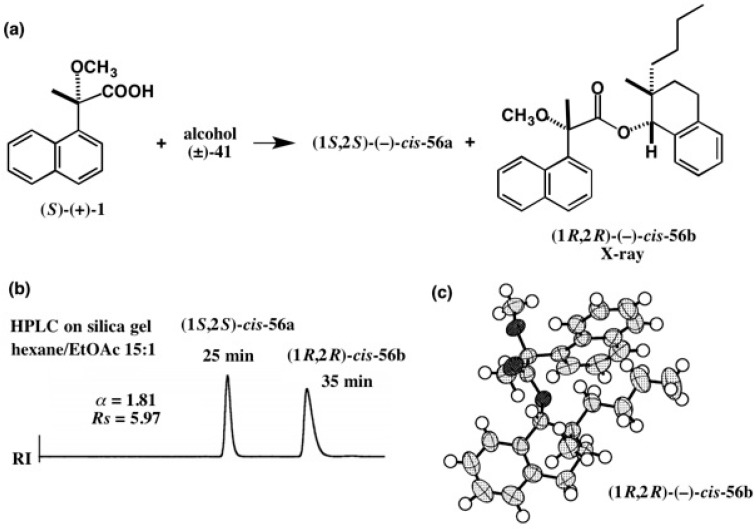

5.2. Application of the MαNP Acid Method to Aromatic Alcohol

As explained in Figure 35, one of the advantages of the MαNP acid method is that diastereomeric esters are largely separated by HPLC on silica gel. This was also proved by the example shown in Figure 39. Alcohol (±)-41, a synthetic precursor of a cryptochiral hydrocarbon 40 (Figure 27), was esterified with MαNP acid (S)-(+)-1, yielding diastereomeric esters 56a and 56b, which were largely separated by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.81, Rs = 5.97) [45]. This is very remarkable, when compared with the case of CSDP acid esters shown in Figure 28, where α = 1.17, and Rs = 1.51. The (1R,2R)-AC of (−)-cis-56b was also confirmed by X-ray crystallography as shown in Figure 39c [57].

Figure 39.

Preparation (a) and HPLC separation (b) of MαNP esters 56a and 56b. HPLC, reprinted with permission from [45]. (c) X-ray ORTEP drawing of MαNP ester (1R,2R)-(−)-cis-56b, reprinted with permission from [57].

5.3. Application of Aliphatic Chain Alcohols

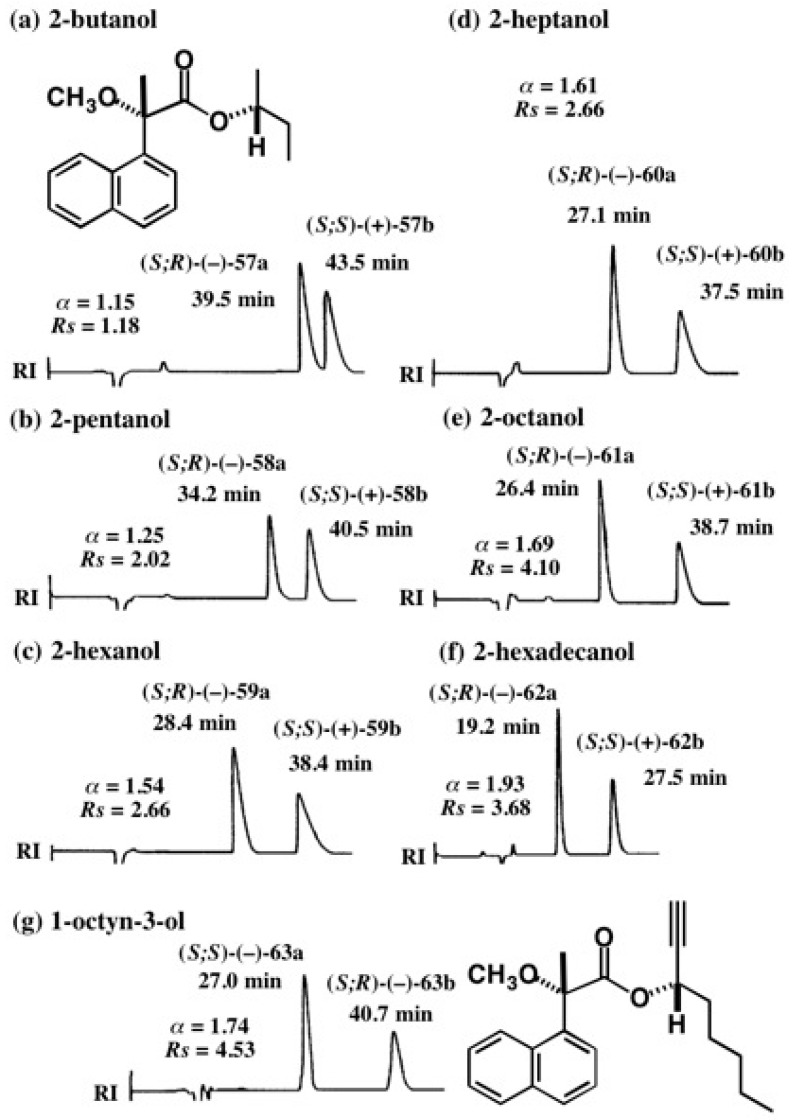

Another advantage of the MαNP acid method is that aliphatic chain alcohols can be resolved as MαNP esters, as exemplified in Figure 40 [58]. For example, racemic 2-butanol was esterified with (S)-(+)-MαNP acid yielding diastereomeric esters, which were almost baseline separated as shown in Figure 40a (α = 1.15, Rs = 1.18). In this case, the chirality of 2-butanol, i.e., the difference between methyl and ethyl groups, was recognized well by the MαNP acid/HPLC.

Figure 40.

HPLC separation of diastereomeric MαNP esters of aliphatic linear alcohols and acetylene alcohol (a–g). Reprinted with permission from [58].

In the case of 2-pentanol, the chirality is made by the difference between methyl and propyl groups. The difference is larger than the difference between methyl and ethyl groups. Therefore, 2-pentanol MαNP esters are more largely separated by HPLC on silica gel as shown in Figure 40b (α = 1.25, Rs = 2.02) [58]. Thus, the HPLC separation reflects the difference of chain length.

This tendency becomes remarkable, when extending to longer chain alcohols [58], as seen in Figure 40; (c) 2-hexanol, difference between methyl and butyl groups: α = 1.54, Rs = 2.66; (d) 2-heptanol, difference between methyl and pentyl groups: α = 1.61, Rs = 2.66; (e) 2-octanol, difference between methyl and hexyl groups: α = 1.69, Rs = 4.10; (f) 2-hexadecanol, difference between CH3 and CH3(CH2)13 groups: α = 1.93, Rs = 3.68. Thus, HPLC separation is very sensitive to the difference of chain length.

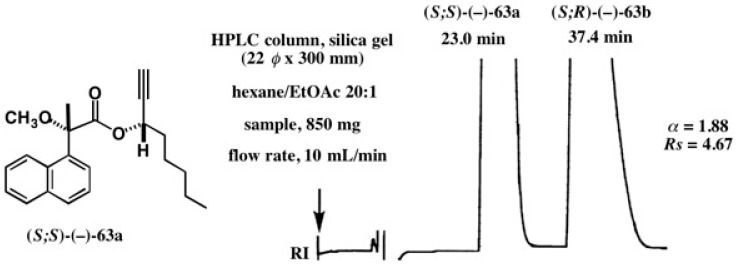

The case of 1-octyn-3-ol is also unique, and diastereomers 63a/63b were largely separated (α = 1.74, Rs = 4.53) (Figure 40g) [58]. Thus, the separation factor α of esters 63a/63b is larger than that of 2-heptanol esters 60a/60b, implying that the acetylene group is effective for HPLC separation. Such a large α value enabled HPLC separation on a large scale as shown in Figure 41, where an 850 mg sample was injected [59]. There is still enough space between the two bands, and hence it would be possible to load a larger amount of the sample. Thus, the MαNP acid method is very useful for the synthesis of enantiopure 1-octyn-3-ol on a large scale, which would be useful as a chiral synthon.

Figure 41.

Preparative HPLC separation of 1-octyn-3-ol MαNP esters 63a/63b: silica gel column, theoretical plate number, n = 9500–11,600; sample (850 mg) was injected. Reprinted with permission from [59].

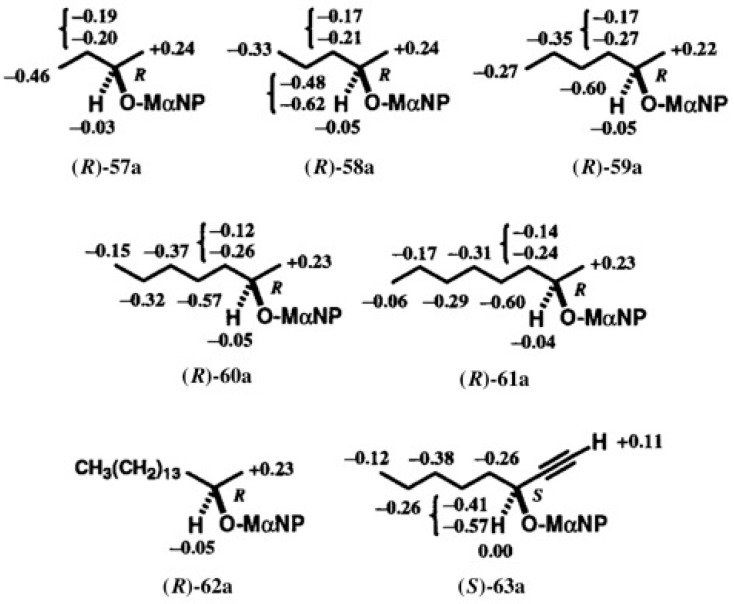

To determine the ACs of these chain alcohol MαNP esters, 1H-NMR spectra were measured, and their ∆δ values were calculated as shown in Figure 42 [58]. In the case of MαNP esters, the chemical shift difference ∆δ is originally defined as ∆δ = δ(R;X) − δ(S;X), where R and S indicate the ACs of the MαNP acid part, while X indicates the AC of the alcohol moiety to be determined.

Figure 42.

1H-NMR ∆δ values in ppm and ACs of the first-eluted MαNP esters. Reprinted with permission from [58].

In Figure 1, Figure 39, and Figure 40, racemic alcohols were esterified with (S)-(+)-MαNP acid 1. In such a case, the formula of ∆δ is transformed as follows. For example, in the case of 2-butanol, the first-eluted ester is defined as (S;X)-57a, where X denotes the AC of the alcohol part in the first-eluted MαNP ester. In addition, the second-eluted ester can be defined as (S;−X)-57b, where −X denotes the opposite AC of X. It should be noted that esters (S;−X) and (R;X) are enantiomers, and therefore, their chemical shift data are equal to each other. So, ∆δ = δ(R;X) − δ(S;X) = δ(S;−X) − δ(S;X) = δ(second-eluted ester) − δ(first-eluted ester) (see Figure 3). Based on this definition, ∆δ values were calculated [58].

In the case of 2-butanol esters 57a/57b, the methyl group showed a positive ∆δ value, and hence was placed on the right side, while the ethyl group showed negative ∆δ values, and hence was placed on the left side. Therefore, the AC of the first-eluted ester was determined to be (R) (Figure 42). In other esters 58–62, ∆δ values are reasonably distributed indicating (R)-ACs (Figure 42). Thus in the case of all MαNP esters 57–62, the (S;R)-diastereomers were eluted first [58].

In the case of 1-octyn-3-ol MαNP esters 63a/63b, the acetylene proton showed a positive ∆δ value, while the pentyl group showed negative ∆δ values, leading to the (S)-AC (Figure 42) [58].

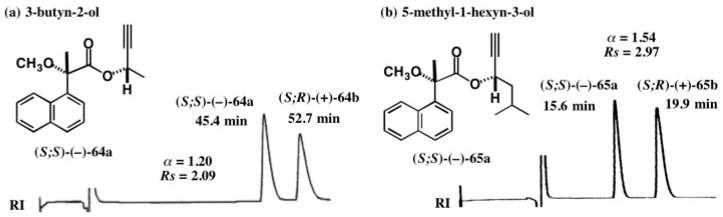

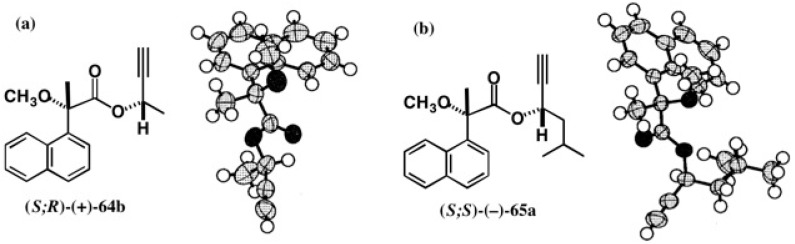

5.4. Application of Acetylene Chain Alcohols

The MαNP acid method has been applied to other acetylene alcohols as shown in Figure 43. In the case of 3-butyn-2-ol, the diastereomers 64a/64b were separated well as shown in figure 42a (α = 1.20, Rs = 2.09) [60]. The result indicated that acetylene and methyl groups are recognized well by HPLC on silica gel. In the case of 5-methyl-1-hexyn-3-ol, the iso-butyl group is longer than the methyl group, and hence esters 65a/65b were much more largely separated (α = 1.54, Rs = 2.97) [60].

Figure 43.

HPLC separation of diastereomeric MαNP esters of acetylene alcohols: (a) 3-butyn-2-ol, hexane/EtOAc 20:1, reprinted with permission from [60]; (b) 5-methyl-1-hexyn-3-ol, hexane/EtOAc 10:1, reprinted from [61].

It was easy to determine the ACs of these esters by applying the MαNP ester diamagnetic anisotropy method as shown Figure 44 [60]. In both cases, acetylene protons showed positive ∆δ values, while methyl and iso-butyl groups showed negative ∆δ values. Therefore, the ACs of the first-eluted esters were unambiguously determined to be (S).

Figure 44.

1H-NMR ∆δ values in ppm and ACs of the first-eluted MαNP esters 64a (a) and 65a (b). Reprinted with permission from [60].

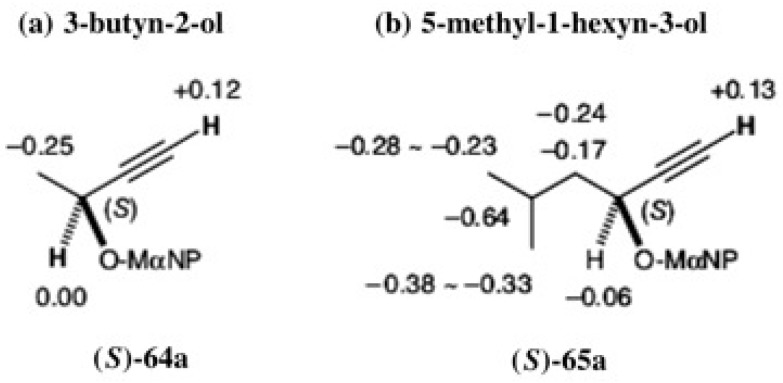

It should be noted that the ACs of these MαNP esters could be confirmed by X-ray crystallography. We were lucky to obtain single crystals of MαNP esters (S;R)-(+)-64b and (S;S)-(−)-65a, when recrystallizing from MeOH. The ORTEP drawings are illustrated in Figure 45, where the ACs of the alcohol parts were clearly determined by using the MαNP acid part as an internal reference of AC [56]. The ACs determined by the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method were thus corroborated by X-ray crystallography.

Figure 45.

X-ray ORTEP drawings of MαNP esters (S;R)-(+)-64b (a) and (S;S)-(−)-65a (b). Reprinted with permission from [56].

The 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method using MαNP acid has been originally developed as an empirical rule. However, we have never encountered any exception, where the AC determined by the 1H-NMR MαNP ester method disagreed with that by X-ray crystallography. This fact is very important for making the 1H-NMR MαNP ester method more reliable.

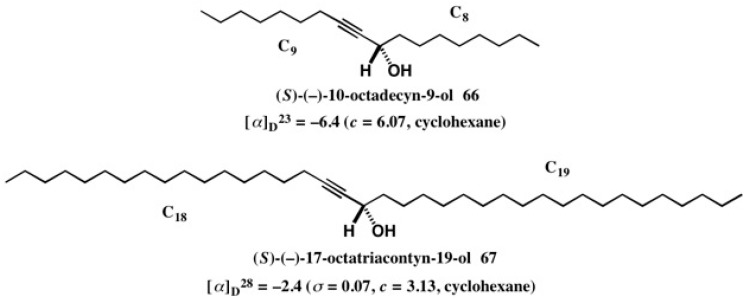

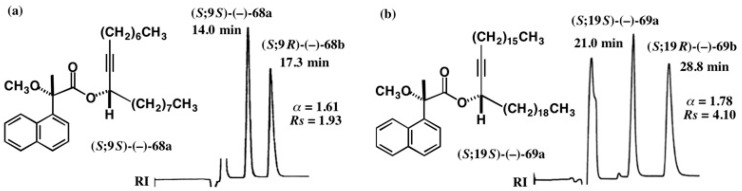

The MαNP acid method is also applicable to internal acetylene alcohols with long chains, and some enantiopure alcohols with established ACs were synthesized as exemplified in Figure 46 [62]. Racemic acetylene alcohol (±)-66 was esterified with (S)-(+)-MαNP acid yielding diastereomeric esters 68a/68b, which were largely separated by HPLC on silica gel (α = 1.61, Rs = 1.93) (Figure 47a) [62]. It was surprising to find that although the two side chains are similar in length, i.e., C8 and C9, the diastereomers were well separated. This fact implies that the acetylene group makes a dominant contribution for HPLC separation.

Figure 46.

Enantiopure acetylene alcohols with established ACs, which were prepared by the MαNP acid method.

Figure 47.

HPLC separation of diastereomeric MαNP esters of long chain internal acetylene alcohols: (a) 68a/68b, hexane/EtOAc 20:1, reprinted from [61]; (b) 69a/69b, hexane/EtOAc 50:1, reprinted with permission from [62].

The HPLC data of esters 69a/69b are also interesting, because the separation factor α became larger (α = 1.78, Rs = 4.10) (Figure 47b) [62]. The two side chains consist of C18 and C19 and hence they are more similar to each other than in the case of 68a/68b. However, the separation factor α is larger than that of 68a/68b. This fact again indicates that the acetylene group is a key factor to control the HPLC separation on silica gel.

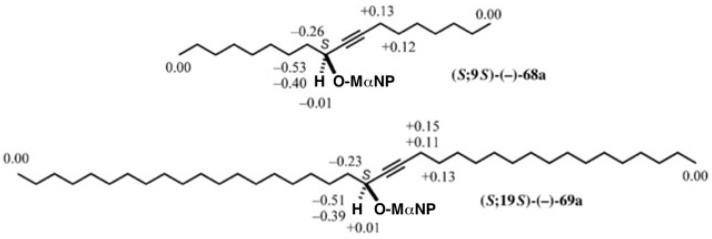

To determine the ACs of these compounds, 1H-NMR ∆δ values were calculated as shown in Figure 48 [62].

Figure 48.

1H-NMR ∆δ values in ppm and ACs of the first-eluted MαNP esters 68a and 69a. Reprinted with permission from [62].

In MαNP esters 68a/68b, the side chain containing the acetylene group showed positive ∆δ values, while the saturated side chain showed negative ∆δ values. Therefore, the AC of the first-eluted MαNP ester (−)-68a was determined to be (S). The same was found in MαNP esters 69a/69b, which led to the (S)-AC of the first eluted ester (−)-69a.

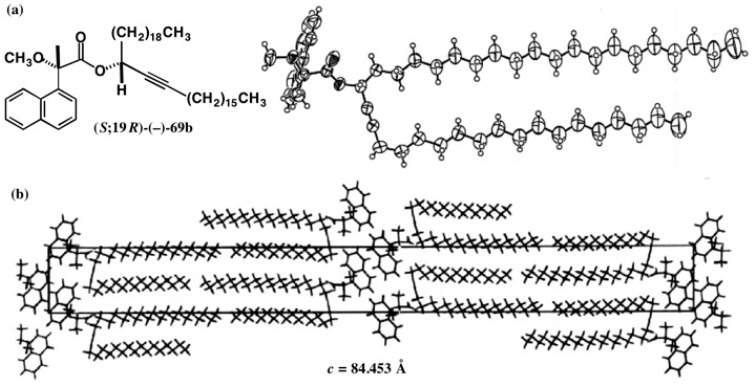

MαNP esters 68a, 68b, and 69a were obtained as a syrup or amorphous solid except ester 69b, which was recrystallized from iso-PrOH, giving thin plate crystals. However, because their thickness was ca. 5 μm, a conventional X-ray machine could not be used. Instead, the strong X-ray of synchrotron radiation in the SPring-8 in Hyogo, Japan was used for X-ray crystallography (final R = 0.0814). The ORTEP drawing was obtained as shown in Figure 49a, where (19R)-AC was unambiguously determined by using the MαNP acid part as an internal reference [62]. Thus, the AC assigned by the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy was confirmed by X-ray crystallography.

Figure 49.

X-ray crystal structure of MαNP ester (S;19R)-(−)-69b. (a) ORTEP drawing; (b) Crystal packing of (S;19R)-(−)-69b: view along the a axis; the rectangle indicates a unit lattice. Reprinted with permission from [62].

Figure 49b shows the crystal packing of MαNP ester molecules 69b, where the rectangle shows a unit lattice containing four molecules [62]. It is interesting that two side chains of a molecule are placed in parallel, and that these two alkyl chains form a pair with those of the second molecule in the unit lattice. These pairs are arranged so as to form an aliphatic bilayer in the crystal. The third and fourth molecules similarly form an aliphatic bilayer. It is very interesting that these aliphatic bilayer structures are similar to those of cell membranes.

It was easy to recover enantiopure long chain acetylene alcohol (S)-(−)-67, as shown in Figure 50. The specific rotation value of alcohol (S)-(−)-67 was small, but it was still measurable as listed in Figure 46, where the observed was larger than the standard deviation σ [62].

Figure 50.

Preparation of enantiopure acetylene alcohol (S)-(−)-67.

5.5. Synthesis of Enantiopure Saturated Long Chain Alcohol with Established AC

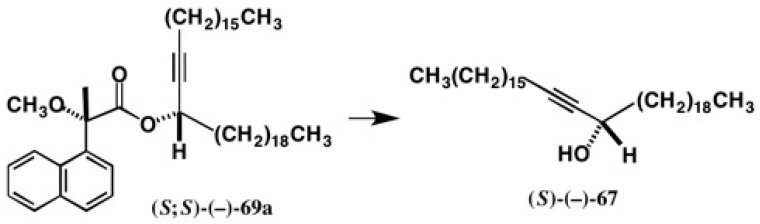

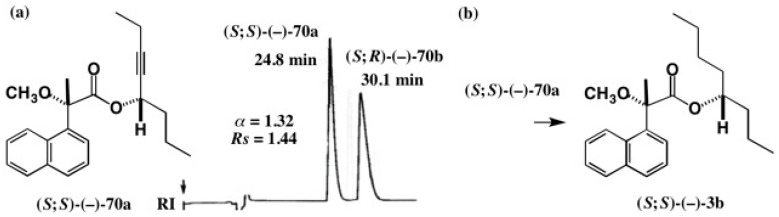

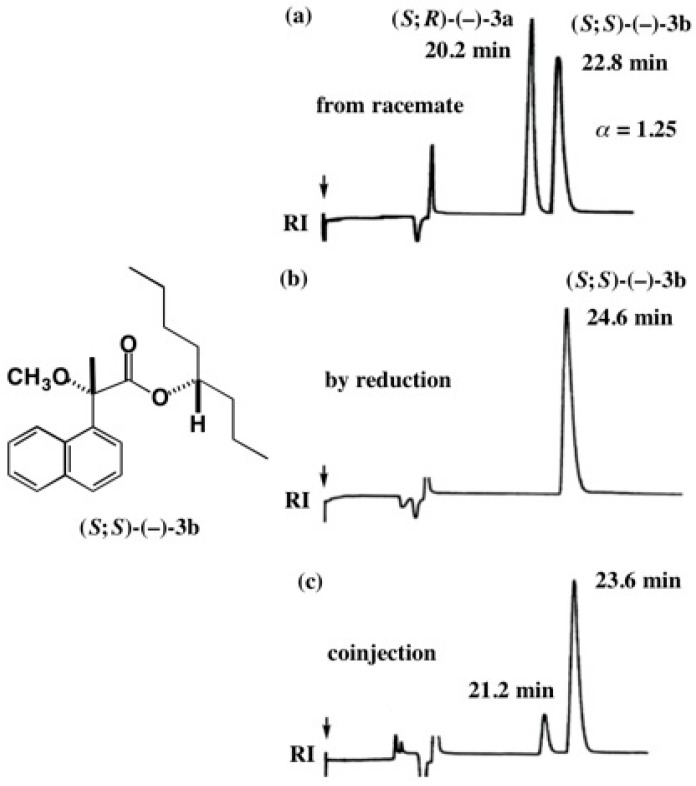

Next we tried to synthesize enantiopure saturated long chain alcohols. However, it was already reported that the direct catalytic reduction of acetylene alcohol led to partial racemization [63]. Therefore, to prevent the racemization, acetylene alcohol MαNP ester was subjected to the catalytic reduction, and the diastereomeric purity was checked as follows [13].

As a model compound, 5-octyn-4-ol was selected, and it was easy to separate its diastereomeric MαNP esters as shown in Figure 51a [60]. The first-eluted MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-70a was reduced with H2/PtO2 in diethyl ether yielding 4-octanol MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-3b [13]: see also Figure 1.

Figure 51.

HPLC separation of diastereomeric 5-octyn-4-ol MαNP esters, and conversion to 4-octanol MαNP ester by catalytic reduction: (a) 70a/70b, hexane/EtOAc 20:1, reprinted with permission from [60]; (b) Reduction with H2/PtO2 in diethyl ether.

To check the diastereomeric purity of MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-3b obtained by the catalytic reduction of acetylene alcohol MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-70a, HPLC comparison was performed as shown in Figure 52 [13].

Figure 52.

Diastereomeric purity check of MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-3b obtained by the catalytic reduction of acetylene alcohol MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-70a. HPLC, hexane/EtOAc 20:1. (a) (S;R)-(−)-3a and (S;S)-(−)-3b prepared from racemic 4-octanol (±)-2; (b) (S;S)-(−)-3b obtained by the reduction of ester (S;S)-(−)-70a; (c) coinjection of two samples used in (a,b). Reprinted with permission from [13].

Figure 52a shows the HPLC of esters (S;R)-(−)-3a and (S;S)-(−)-3b prepared from racemic 4-octanol (±)-2; the part (b) shows the HPLC of ester (S;S)-(−)-3b obtained by reduction of ester (S;S)-(−)-70a; the part (c) shows the coinjection of two samples used in (a) and (b). The HPLC (b) shows only one band indicating that the product was diastereomerically pure, and hence it was concluded that no racemization occurred during the catalytic reduction of the acetylene alcohol MαNP ester [13].

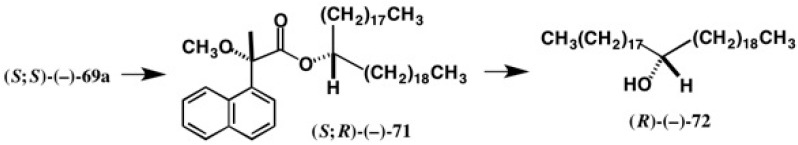

Next, the ultimate cryptochiral alcohol, (R)-(−)-19-octatriacontanol 72, was synthesized (Figure 53) [13]. Enantiopure acetylene alcohol MαNP ester (S;S)-(−)-69a was subjected to catalytic reduction, yielding saturated alcohol MαNP ester (S;R)-(−)-71. To recover alcohol 72, a drastic reaction condition was necessary; ester (S;R)-(−)-71 was treated with NaOCH3 in iso-PrOH yielding enantiopure alcohol (R)-(−)-72: = −0.038 (σ 0.56, c 1.04, CHCl3). The specific rotation value was thus very small, and much smaller than the standard deviation σ. Therefore, the observed value is not reliable, but there is no proper physical data to specify this enantiomer. So, the observed minus sign was used here [13].

Figure 53.

Preparation of enantiopure long chain alcohol with ultimate cryptochirality (R)-(−)-72.

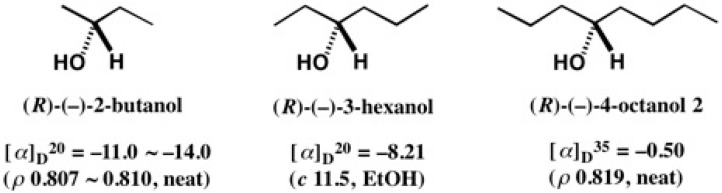

The present assignment of the minus sign to alcohol (R)-72 is logically reasonable, when compared with the optical rotation data of (R)-(−)-2-butanol, (R)-(−)-3-hexanol, and (R)-(−)-4-octanol 2 (Figure 54). These are chain alcohol homologs with the structure of CH3(CH2)nn-CH(OH)-(CH2)n+1CH3, where n = 0 for 2-butanol; n = 1 for 3-hexanol; n = 2 for 4-octanol 2; n = 17 for 19-octatriacontanol 72. Therefore, these compounds should have the same relationship between AC and the optical rotation sign.

Figure 54.

ACs and optical rotation data of alcohol homologs with the structure of CH3(CH2)n-CH(OH)-(CH2)n+1CH3: (R)-(−)-2-butanol [64], (R)-(−)-3-hexanol [65], and (R)-(−)-4-octanol 2 [13].

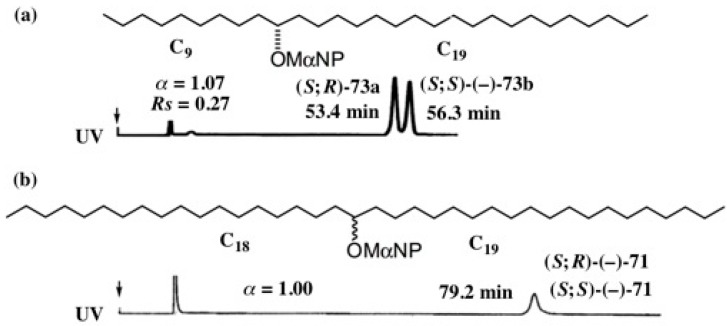

It is interesting to study whether the MαNP ester method is still useful for recognizing the chirality of saturated long chain alcohols or not. Figure 55 shows the analytical HPLC of two examples, 10-nonacosanol esters 73a/73b and 19-octatriacontanol esters 71 [13].

Figure 55.

Analytical HPLC of saturated long chain alcohols MαNP esters: silica gel column (10 φ × 300 mm, n = 34,400); sample (0.1 mg); detected by UV. (a) hexane/EtOAc 80:1; (b) hexane/EtOAc 150:1. Redrawn with permission from [13].

In the case of esters 73a/73b, CH3(CH2)88- and CH3(CH2)18- groups are compared. It was surprising to find that MαNP esters (S;R)-73a and (S;S)-73b were clearly separated, although two long alkyl chains CH3(CH2)8- and CH3(CH2)18- were compared (Figure 55a). The MαNP acid is thus useful for recognizing the chirality of long alkyl chain alcohols, where two chains are different in length to some extent.

Diastereomeric 19-octatriacontanol MαNP esters 71 were prepared from racemic 19-octa- triacontanol (±)-72 and (S)-(+)-MαNP acid, and the mixture was subjected to analytical HPLC as shown in Figure 55b. However, it was not possible to separate the two esters and they were eluted as a single peak [13]. It may be reasonable, because CH3(CH2)17– and CH3(CH2)18– chains are compared in the case of esters 71. Namely, the difference is only a –CH2 moiety between the CH3(CH2)17– and CH3(CH2)18– groups. This alcohol is thus one of the ultimate cryptochiral compounds, and hence the enantiopure synthesis of such a compound with established AC is extremely difficult.

As shown in Figure 53, however, it was possible to synthesize enantiopure 19-octatriacontanol (R)-(−)-72 with established AC. The MαNP acid method is thus also very powerful for the enantiopure synthesis of such ultimate cryptochiral compounds with established ACs [13].

6. Conclusions

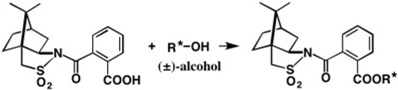

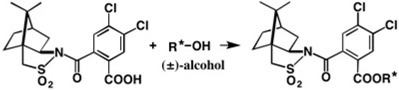

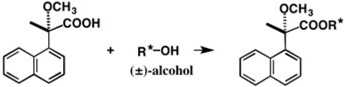

We have developed some chiral auxiliaries, such as camphorsultam, CSP acid, CSDP acid, and MαNP acid, which are very useful for the synthesis of enantiopure compounds and simultaneous determination of their ACs. As summarized in Table 1, the prepared diastereomers were separated well by HPLC on silica gel; the separation factor α for CSP esters (average α = 1.09), CSDP esters (average α = 1.20), MαNP esters (average α = 1.58). So, in most cases, HPLC separation on a preparative scale was possible.

Table 1.

Summary of the preparation of diastereomers, HPLC separation, and AC determination by X-ray crystallography and/or 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy.

| Preparation of Diastereomers | HPLC | AC Determination |

|---|---|---|

|

α, not determined Rs = 0.7~2.87 av. 1.74 |

X-ray, 6 examples |

|

α = 1.05~1.1 av. 1.09 Rs = 1.3~1.6 av. 1.4 |

X-ray, 3 examples |

|

α = 1.14~1.25 av. 1.20 Rs = 0.91~1.94 av. 1.31 |

X-ray, 4 examples |

|

α = 1.15~1.93 av. 1.58 Rs = 1.18~5.97 av. 2.98 |

1H-NMR, 13 examples X-ray, 5 examples |

α, separation factor; Rs, resolution factor; R*, chiral substituent.

Another advantage of the present methods is that the separated derivatives have a high probability to form single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography. Camphorsultam, CSP acid, and CSDP acid contain heavy atoms such as S and Cl, and hence their ACs could be determined by the X-ray anomalous scattering effect of heavy atoms. In addition, the ACs of these chiral auxiliaries, including MαNP acid, are established and hence they could be used as the internal reference of AC. So, it was easy to determine the ACs from the ORTEP drawings.

It should be noted that the target compound and chiral auxiliary are connected by a covalent bond, not by an ionic bond, and hence the covalently-bonded diastereomers can be separated and purified by HPLC on silica gel. On the other hand, ionic-bonded diastereomers are usually separated by fractional crystallization, and hence in some cases, it was difficult to obtain enantiopure compounds by fractional crystallization.

MαNP acid is very unique, because it can be applied to aliphatic alcohols in addition to aromatic alcohols. Diastereomeric MαNP esters are largely separated by HPLC on silica gel, as shown in Table 1. In this sense, the MαNP acid is superior to the Mosher’s MTPA acid and MPA acid. The ACs of MαNP esters could be determined by 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy where ∆δ values are ca. four times larger than those of MTPA esters. In some cases, single crystals of MαNP esters were obtained, and ACs were easily determined from ORTEP drawings. We have never encountered any exception, where the AC determined by 1H-NMR disagreed with that by X-ray crystallography. This fact is very important to evaluate the reliability of the 1H-NMR diamagnetic anisotropy method using MαNP acid.

The author believes that the diastereomer method using chiral molecular tools explained here would be applicable to a variety of compounds, and hopes that it would be useful for the progress of molecular chirality science.

Acknowledgments

The studies explained here were carried out in collaboration with many coworkers, especially my previous graduate students, whose names are listed in the references. The author sincerely thanks them for their efforts and contributions. The author also thanks Dr. George A. Ellestad, Department of Chemistry, Columbia University, for his valuable suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Okamoto Y., Ikai T. Chiral HPLC for Efficient Resolution of Enantiomers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:2593–2608. doi: 10.1039/b808881k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf C., Pirkle W.H. Conformational Effects on the Enantioselective Recognition of 4-(3,5-Dinitro-benzamido)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrophenanthrene Derivatives by a Naproxen-derived Chiral Stationary Phase. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3597–3603. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00307-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davankov V.A. Separation of Enantiomeric Compounds Using Chiral HPLC Systems. A Brief Review of General Principles, Advances, and Development Trends. Chromatographia. 1989;27:475–482. doi: 10.1007/BF02319569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allenmark S., Andersson S. Optical Resolution of Some Biologically Active Compounds by Chiral Liquid Chromatography on BSA-silica (Resolvosil) Columns. Chirality. 1989;1:154–160. doi: 10.1002/chir.530010209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitbach A.S., Lim Y., Xu Q.-L., Kurti L., Armstrong D.W., Breitbach A.Z. Enantiomeric Separations of α-Aryl Ketones with Cyclofructan Chiral Stationary Phases via High Performance Liquid Chromatography and Supercritical Fluid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2016;1427:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harada N. Powerful Novel Chiral Acids for Enantioresolution, Determination of Absolute Configuration, and MS Spectral Determination of Enantiomeric Excess. TCI MAIL. 2003;117:2–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harada N. Chiral Auxiliaries Powerful for Both Enantiomer Resolution and Determination of Absolute Configuration by X-Ray Crystallography. In: Denmark S.E., Siegel J.S., editors. Topics in Stereochemistry. Volume 25. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2006. pp. 177–203. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada N. Powerful Chiral Molecular Tools for Preparation of Enantiopure Alcohols and Simultaneous Determination of Their Absolute Configurations by X-Ray Crystallography and/or 1H-NMR Anisotropy Methods. In: Francotte E., Lindner W., editors. Chirality in Drug Research. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. pp. 283–321. Chapter 9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harada N. Determination of Absolute Configurations by X-Ray Crystallography and 1H-NMR Anisotropy. Chirality. 2008;20:691–723. doi: 10.1002/chir.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada N. X-Ray Crystallography and 1H-NMR Anisotropy Methods for Determination of Absolute Configurations. In: Andrushko V., Andrushko N., editors. Stereoselective Synthesis of Drugs and Natural Products. Wiley-Blackwell; New York, NY, USA: 2013. pp. 1629–1662. Chapter 46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada N. Determination of Absolute Configurations by Electronic CD Exciton Chirality, Vibrational CD, 1H-NMR Anisotropy, and X-Ray Crystallography Methods—Principles, Practices, and Reliability. In: Cid M.M., Bravo J., editors. Structure Elucidation in Organic Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2015. pp. 393–443. Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohrui H., Terashima H., Imaizumi K., Akasaka K. A Solution of the “Intrinsic Problem” of Diastereomer Method in Chiral Discrimination. Development of a Method for Highly Efficient and Sensitive Discrimination of Chiral Alcohols. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. 2002;78:69–72. doi: 10.2183/pjab.78.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akagi M., Sekiguchi S., Taji H., Kasai Y., Kuwahara S., Watanabe M., Harada N. A General Method for the Synthesis of Enantiopure Aliphatic Chain Alcohols with Established Absolute Configurations. Part 2, via Catalytic Reduction of Acetylene Alcohol MαNP Esters. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2014;25:1466–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2014.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takagi T., Aoyanagi N., Nishimura K., Ando Y., Ota T. Enantiomer Separations of Secondary Alkanols with Little Asymmetry by High-performance Liquid Chromatography on Chiral Columns. J. Chromatogr. 1993;629:385–388. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)87053-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nie M.-Y., Zhou L.-M., Liu X.-L., Wang Q.-H., Zhu D.-Q. Gas Chromatographic Enantiomer Separation on Long-chain Alkylated β-Cyclodextrin Chiral Stationary Phases. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2000;408:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(99)00804-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohtaki T., Akasaka K., Kabuto C., Ohrui H. Chiral Discrimination of Secondary Alcohols by Both 1H-NMR and HPLC After Labeling with a Chiral Derivatization Reagent, 2-(2,3-Anthracenedicarbox-imide)cyclohexane Carboxylic Acid. Chirality. 2005;17:S171–S176. doi: 10.1002/chir.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bijvoet J.M., Peerdeman A.F., van Bommel A.J. Determination of the Absolute Configuration of Optically Active Compounds by Means of X-rays. Nature. 1951;168:271–272. doi: 10.1038/168271a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harada N., Nakanishi K. Circular Dichroic Spectroscopy—Exciton Coupling in Organic Stereochemistry. University Science Books; Mill Valley, CA, USA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berova N., Polavarapu P., Nakanishi K., Woody R.W. Comprehensive Chiroptical Spectroscopy. Volumes 1 and 2 John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levene P.A., Rothen A. Optical Activity and Chemical Structure. J. Org. Chem. 1936;1:76–133. doi: 10.1021/jo01230a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murai S., Soutome T., Yoshida N., Osawa S., Harada N. Synthesis, Circular Dichroism, and Absolute Stereochemistry of a Fecht Acid Analog and Related Compounds. Enantiomer. 2000;5:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murai S. Master’s Thesis. Tohoku University; Sendai, Japan: 1991. Synthesis of Chiral Spiro[3.3]heptane Compounds and Determination of their Absolute Configurations. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harada N., Soutome T., Murai S., Uda H. A Chiral Probe Useful for Optical Resolution and X-Ray Crystallographic Determination of the Absolute Stereochemistry of Carboxylic Acids. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1993;4:1755–1758. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80409-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soutome T. Master’s Thesis. Tohoku University; Sendai, Japan: 1993. Synthesis of Chiral Bridged Aromatic Compounds and Determination of their Absolute Configurations. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falk H., Reich-Rohrwig P., Schloegl K. Absolute Configuration and Circular Dichroism of Optically Active [2.2]Paracyclophane Derivatives. Tetrahedron. 1970;26:511–527. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97846-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberhardt H., Schloegl K. Stereochemistry of Planar-chiral Compounds. II. Preparation, Chiroptical Properties, and Absolute Configuration of [10]Paracyclophane Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1972;760:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakazaki M., Yamamoto K., Ito M., Tanaka S. Preparations of Optically Active [8][8]- and [8][10]-Paracyclophanes with Known Absolute Configurations. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:3468–3473. doi: 10.1021/jo00442a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz L.H., Bathija B.L. Absolute Configuration of an Ansa Compound: Gentisic Acid Nona-methylene Ether. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:5344–5347. doi: 10.1021/ja00433a048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schloegl adopted the configurations of (R)-(–)-12, (R)-(+)-14, and (R)-(–)-15: Schloegl K. Planar Chiral Molecular Structures. Top. Curr. Chem. 1984;125:27–62.

- 30.Harada N., Soutome T., Nehira T., Uda H., Oi S., Okamura A., Miyano S. Revision of the Absolute Configurations of [8]Paracyclophane-10-carboxylic and 15-Methyl[10]paracyclophane-12-carboxylic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:7547–7548. doi: 10.1021/ja00069a082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harada N., Nehira T., Soutome T., Hiyoshi N., Kido F. Chiral Phthalic Acid Amide, a Chiral Auxiliary Useful for Enantiomer Resolution and X-Ray Crystallographic Determination of the Absolute Stereochemistry of Alcohols. Enantiomer. 1996;1:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nehira T. Ph.D. Thesis. Tohoku University; Sendai, Japan: 1996. Development of Novel Chiral Resolution Methods and Determination of the Absolute Configurations of Twisted π-Electron Compounds. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harada N., Koumura N., Feringa B.L. Chemistry of Unique Chiral Olefins. 3. Synthesis and Absolute Stereochemistry of trans- and cis-1,1′,2,2′,3,3′,4,4′-Octahydro-3,3′-dimethyl-4,4′-biphenanthrylidenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:7256–7264. doi: 10.1021/ja970669e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koumura N., Harada N. X-Ray Crystallographic Determination of the Stereochemistry of a Unique Chiral Olefin, [CD(–)238.0]-(3R,3′R)-(P,P)-(Z)-(+)-1,1′,2,2′,3,3′,4,4′-Octahydro-3,3′-dimethyl-4,4′-biphenan-thrylidene. Enantiomer. 1998;3:251–253. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koumura N., Harada N. Photochemistry and Absolute Stereochemistry of Unique Chiral Olefins, trans- and cis-1,1′,2,2′,3,3′,4,4′-Octahydro-3,3′-dimethyl-4,4′-biphenanthrylidenes. Chem. Lett. 1998;1998:1151–1152. doi: 10.1246/cl.1998.1151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koumura N., Zijlstra R.W.J., van Delden R.A., Harada N., Feringa B.L. Light-driven Monodirectional Molecular Rotor. Nature. 1999;401:152–155. doi: 10.1038/43646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujita T., Kuwahara S., Harada N. A New Model of Light Powered Chiral Molecular Motor with Higher Speed of Rotation (1). Synthesis and Absolute Stereostructure. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005;2005:4533–4543. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200500322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harada N., Koumura N., Robillard M. Chiral Dichlorophthalic Acid Amide, an Improved Chiral Auxiliary Useful for Enantioresolution and X-Ray Crystallographic Determination of Absolute Stereo-chemistry. Enantiomer. 1997;2:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cervinka O., Belovsky O., Fabryova A., Dudek V., Grohman K. Asymmetric Reactions. XII. A Limited Use of Asymmetric Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley Type Reduction for Determination of Absolute Configuration of Alcohols. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1967;32:2618–2624. doi: 10.1135/cccc19672618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seebach D., Beck A.K., Roggo S., Wonnacott A. Enantioselective Addition of Aryl Groups to Aromatic Aldehydes using Chiral Aryltitanium binaphthol Derivatives. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1985;118:3673–3682. doi: 10.1002/chin.198551086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe M., Kuwahara S., Harada N., Koizumi M., Ohkuma T. Enantioresolution by the Chiral Phthalic Acid Method: Absolute Configurations of (2-Methylphenyl)phenylmethanol and Related Compounds. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1999;10:2075–2078. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(99)00231-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuwahara S. Master’s Thesis. Tohoku University; Sendai, Japan: 1999. Chiral Resolution of Alcohols by the Chiral Phthalic Acid Method and Determination of their Absolute Configurations: New Developments. [Google Scholar]