Abstract

The catalytic properties of olefin metathesis ruthenium complexes bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands with stereogenic centers on the backbone are described. Differences in catalytic behavior depending on the backbone configurations of symmetrical and unsymmetrical NHCs are discussed. In addition, an overview on asymmetric olefin metathesis promoted by chiral catalysts bearing C2-symmetric and C1-symmetric NHCs is provided.

Keywords: metathesis, NHC ligands, stereogenic centers, ruthenium catalysts

1. Introduction

Ruthenium-catalyzed olefin metathesis represents nowadays an indispensable synthetic tool for constructing carbon-carbon double bonds in both organic and polymer chemistry [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The use of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) as ancillary ligands [9,10] for ruthenium olefin metathesis complexes (second generation catalysts) has led to tremendous advances in the design of robust and effective catalysts for various metathesis applications, including some challenging and difficult transformations [11,12,13,14,15].

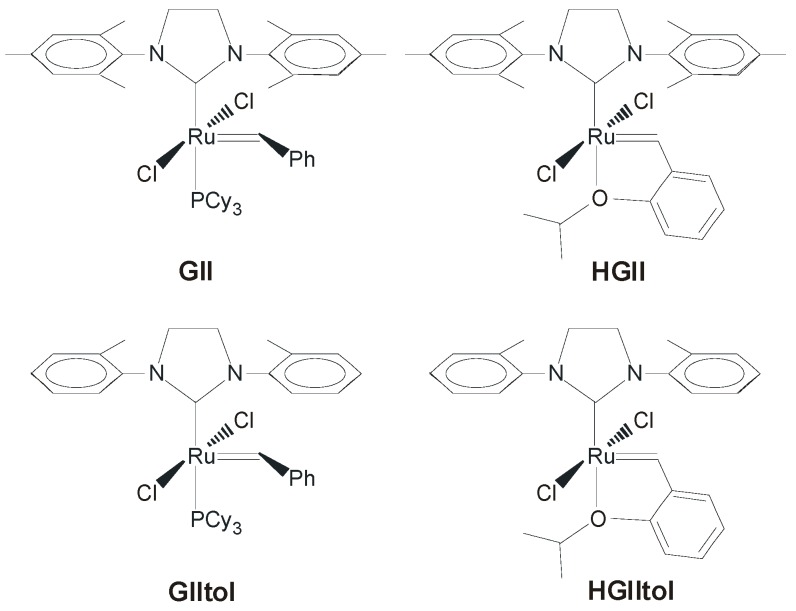

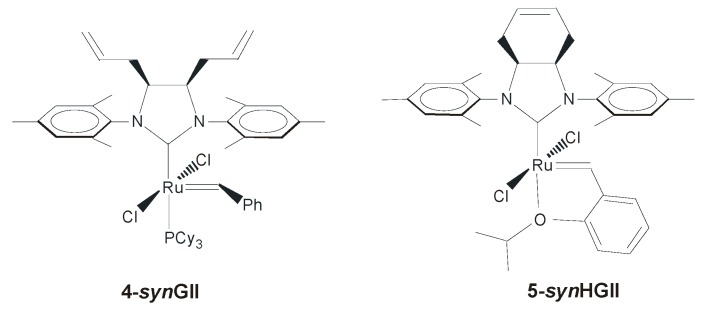

In order to improve catalytic performance of NHC-stabilized ruthenium metathesis complexes, many efforts have been devoted to the manipulation of the NHC scaffold of the commercially available second generation catalysts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Commercial Grubbs’ and Hoveyda-Grubbs’ second generation catalysts.

Modifications of the NHC ligand include the nature of the ring backbone (saturated or unsaturated), substitution at the nitrogen atoms and at the carbon atoms of the backbone, ring-size variation, introduction of heteroatoms in the skeleton, and introduction of chirality [11,12,13,14,15]. Among these, modifications of the steric and electronic properties of substituents on the backbone and/or the nitrogen atoms have had a significant impact on catalyst activity, stability and selectivity in several metathesis applications [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

This review provides an overview of the reactivity and selectivity shown by olefin metathesis ruthenium catalysts bearing NHC ligands with substituents on the backbone in definite stereochemical arrangements, mostly focusing on their catalytic performances in challenging metathesis reactions, such as asymmetric or sterically hindered reactions. Relevant literature data for ruthenium catalysts with syn and anti NHC backbone configurations are discussed according to the substitution pattern at the nitrogen atoms (symmetrical or unsymmetrical), highlighting, where it is possible, the effect of changing NHC backbone configuration on catalytic behavior. A brief description of ruthenium catalysts coordinated with backbone-monosubstituted NHCs is also presented.

2. Ruthenium Catalysts Bearing Symmetrically N-Substituted NHCs with syn or anti Backbone Configurations

2.1. Non-Aromatic N-Substituents

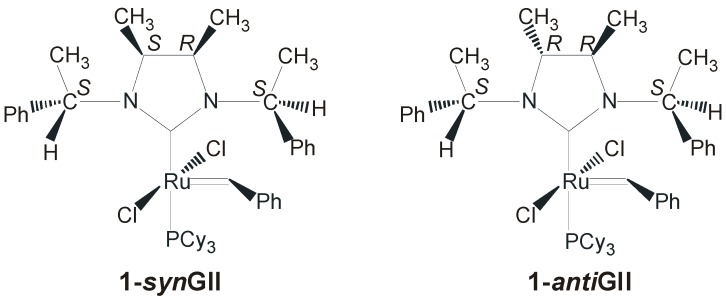

Many research efforts have been devoted to improving catalyst performance by increasing the σ-donor properties of the NHC ligand through the introduction of more electron-donating N-alkyl substituents. However, most ruthenium complexes bearing only alkyl side chains were unstable and did not provide better catalytic results compared with the parent catalysts GII and HGII [30,31,32,33]. In 2008, the first examples of monophosphine Ru complexes bearing monodentate saturated NHC ligands which combine benzyl chiral groups on the nitrogens with methyl backbone substituents were reported in the literature (1-synGII and 1-antiGII, Figure 2) [21].

Figure 2.

NHC-Ru complexes with N-(S)-phenylethyl groups and syn or anti methyl groups on the backbone.

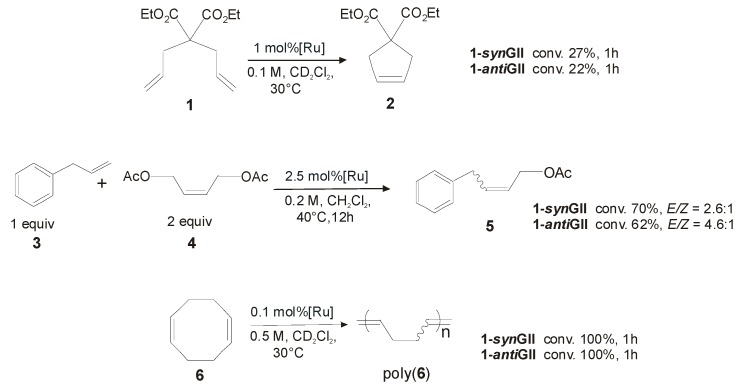

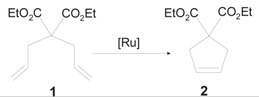

Both complexes, presenting S-phenylethyl N-substituents and syn (1-synGII) or R,R-anti (1-antiGII) methyl groups on the backbone, were prepared in around 40% yield by deprotonation of the corresponding imidazolinium salts obtained after condensation of the corresponding chiral diamines. 1-synGII showed higher cataytic activity than 1-antiGII in all reported representative reactions (Scheme 1) [34], however both performed worse than GII.

Scheme 1.

Representative RCM, CM and ROMP metathesis reactions.

Indeed, in the presence of 1-synGII the ring-closing metathesis (RCM) of diethyl diallylmalonate (1) led to only 27% of conversion to product 2 after 1 h, and the cross–metathesis (CM) of allylbenzene (3) and cis-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (4) to 70% yield of 5 in 12 h, giving in all reactions slightly higher conversion than its anti analogue. Better results, although mediocre compared to GII, were observed in the ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) of 6, where 100% conversion was achieved in 1 h. Most likely the presence of benzyl N-substituents slows down the efficiency of catalysts with respect to N-aryl groups. Nevertheless, it is possible to discriminate in the described complexes a different behavior of catalysts with syn or anti NHC backbone configuration, being 1-synGII always better performing than 1-antiGII. Interestingly, in ROMP and CM reactions both the catalysts gave improved selectivity toward Z double-bond formation (E/Z ratio of 2.6:1 with 1-synGII).

2.2. N-Aryl Substituents

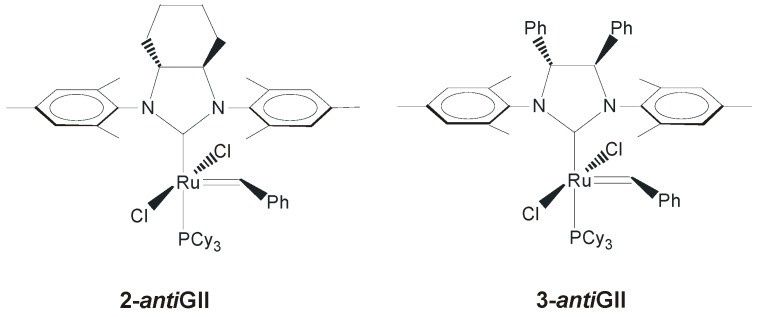

The first complexes with modifications of the backbone of the NHC ring (2-antiGII and 3-antiGII, Figure 3) were reported by Grubbs and coworkers in 1999, along with the famous second-generation catalyst GII [35]. The introduction of this type of NHCs was essentially due to an expected enhanced activity of the resulting ruthenium catalysts, as a consequence of the more basic nature of the NHC, presenting a saturated backbone, with respect to the ruthenium-based complexes with unsaturated NHCs known until then. The RCM activity of complexes 2-antiGII and GII was explored and an increased reactivity especially at elevated temperatures was actually found.

Figure 3.

Catalysts with anti NHC backbone.

The first example of a ruthenium complex bearing an NHC ligand with a syn configuration of the backbone was reported by Köhler et al., in 2005 (Figure 4) [36]. With the aim of synthesizing complex 4-synGII with syn allyl substituents on the backbone as functional groups for immobilization of the catalyst to a solid support, they instead formed a new NHC ligand featuring an olefinic group in the ligand backbone, then employed it to prepare the complex 5-synHGII. In the ring-closing metathesis of N,N-diallyl-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide, complex 5-synHGII was slightly less active than the benchmark catalysts HGIItol, especially at low catalyst loadings.

Figure 4.

Complexes with olefinic moieties on the NHC.

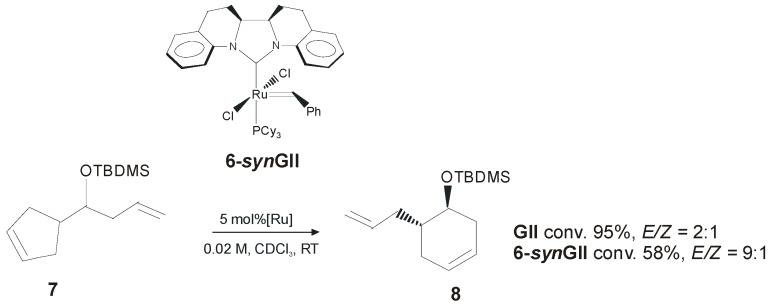

In 2007 Blechert and coworkers presented a new ruthenium complex 6-synGII (Figure 5) containing an NHC ligand in which the N-aryl substituents were connected to the NHC backbone through a syn related C2 unit [37]. In this complex, the steric influence exerted by the aromatic moiety on the ruthenium alkylidene moiety is much stronger than in GII, therefore an increase of the diastereoselectivity of ring rearrangement metathesis reactions (dRRM) was expected. Catalyst 6-synGII was found to have limited stability in solution, even in the absence of olefin substrates, thus showing less catalytic efficiency than GII. Nevertheless, promising results in the RRM of racemic 7 were observed. Possible deactivation pathways involving intramolecular carbene-arene bond formation (intramolecular C-H insertion) were also investigated.

Figure 5.

Diastereoselective RRM of 7 with catalyst 6-synGII.

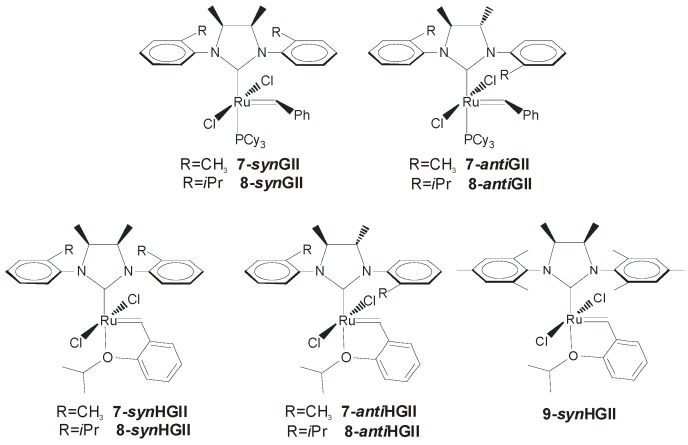

In 2009, the effect of NHC backbone configurations in ruthenium catalysts bearing aromatic N-tolyl groups was explored by Grisi and coworkers (7-synGII and 7-antiGII, Figure 6) [26]. The synthesis of 7-synGII and 7-antiGII proceeded in good yield (55%–60%), although it required several steps, including the preparation of meso and chiral 1,2-diamines [38] to achieve the corresponding NHC ligand precursors.

Figure 6.

Catalysts with syn and anti methyl groups on the NHC backbone.

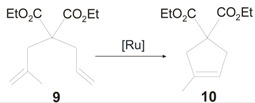

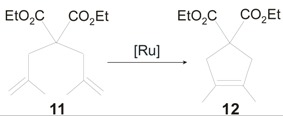

The catalytic properties of 7-synGII and 7-antiGII were probed in RCM reactions and intriguing results were registered above all in the RCM of hindered olefins carried out with 7-synGII. In fact, while 7-synGII promoted the RCM of 1 with almost the same efficiency of the commercial GIItol and slower rate than GII (Table 1), catalytic activity higher than that of GIItol and quite similar to GII was observed in the RCM of 9 (Table 2), and, more significantly, 7-synGII outperformed both GIItol and GII in the RCM of challenging encumbered substrate 11 (Table 3). 7-antiGII showed a lower activity than 7-synGII in the RCM of all three malonate derivatives, with an enhanced gap for hindered substrates where only half of yield with respect to 7-synGII was reached in the ring-closure of 11.

Table 1.

RCM of diethyl diallylmalonate 1.

|

| Catalyst | t (min) | Yield (%) a | Ref. | Catalyst | t (min) | Yield (%) b | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GII | 40 | >98 | [34] | HGIItol | 3 | >99 | [39] |

| GIItol | 60 | 98 | [26] | 7-synHGII | 4 | >99 | [26] |

| 7-synGII | 60 | 98 | [26] | 7-antiHGII | 5 | >99 | [27] |

| 7-antiGII | 60 | 92 | [26] | 8-synHGII | 3 | >99 | [27] |

| 8-synGII | 13 | 100 | [27] | 8-antiHGII | 6 | >99 | [27] |

| 8-antiGII | 60 | >96 | [27] |

a Reactions conducted in CD2Cl2 (0.1 M) at 30 °C, catalyst 1 mol %; b Reactions conducted in C6D6 (0.1 M) at 60 °C, catalyst 1 mol %.

Table 2.

RCM of diethyl allylmethallylmalonate 9.

|

| Catalyst | t (min) | Yield (%) a | Ref. | Catalyst | t (min) | Yield (%) b | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GII | 60 | 98 | [34] | HGIItol | 8 | >99 | [39] |

| GIItol | 60 | 84 | [26] | 7-synHGII | 9 | >99 | [27] |

| 7-synGII | 60 | 90 | [26] | 7-antiHGII | 16 | >99 | [27] |

| 7-antiGII | 60 | 80 | [26] | 8-synHGII | 6 | >99 | [27] |

| 8-synGII | 20 | 95 | [27] | 8-antiHGII | 12 | >99 | [27] |

| 8-antiGII | 60 | 83 | [27] |

a Reactions conducted in CD2Cl2 (0.1 M) at 30 °C, catalyst 1 mol %; b Reactions conducted in C6D6 (0.1 M) at 60 °C, catalyst 1 mol %.

Table 3.

RCM of dietyl dimethallylmalonate 11.

|

| Catalyst | t (h) | Yield (%) a | Ref. | Catalyst | t (h) | Yield (%) b | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GII | 96 | 17 | [34] | HGIItol | 0.5 | >95 | [39] |

| GIItol | 1 | 70 | [26] | 7-synHGII | 0.5 | >95 | [27] |

| 7-synGII | 1 | 82 | [26] | 7-antiHGII | 1 | 78 | [27] |

| 7-antiGII | 1 | 47 | [26] | 8-synHGII | 1 | 85 | [27] |

| 8-synGII | 1 | 70 | [27] | 8-antiHGII | 1 | 59 | [27] |

| 8-antiGII | 1 | 35 | [27] | 9-synHGII | 72 | 55 | [22] |

a Reactions conducted in CD2Cl2 (0.1 M) at 30 °C, catalyst 5 mol %; b Reactions conducted in C6D6 (0.1 M) at 60 °C, catalyst 5 mol %.

No significant difference between the two isomers of 7 with dissimilar backbones was appreciated in CM of 3 and 4, being both catalysts less active than GII, with slightly higher E selectivity. The behavior of the two catalysts was also flattened in the ROMP of 6, where both catalysts exhibit high activities as well as E/Z ratios very similar to GII and GIItol [26].

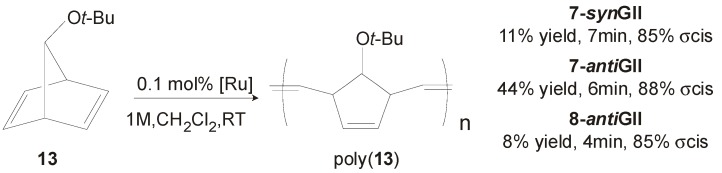

7-synGII and 7-antiGII were tested in the ROMP of 13 (Scheme 2), as well. Both catalysts gave highly sindiotactic poly(13) with low polydispersities (PDI = 1.1–1.2), 100% of anti units and cis contents that reached 88% in the case of 7-antiGII. The latter surprisingly was found more active than the syn analogue, converting 44% of monomer in 6 minutes with 0.1% of catalyst [40].

Scheme 2.

ROMP of 13 promoted by catalysts 7-GII, and 8-antiGII.

An important role on the catalytic activity is also played by the bulkiness of N-aryl substituents, as generally reported for Ru complex, even with backbone unsubstituted NHCs [41,42,43,44,45]. Phosphine-containing Ru catalysts bearing N-o-isopropylphenyl groups in place of N-o-tolyl (8-synGII and 8-antiGII, Figure 6) can be prepared in good yields (60%–65%) with the same procedures adopted for 7-synGII and 7-antiGII [27]. As expected by the increased catalyst bulkiness, 8-synGII and 8-antiGII exhibited higher activity in the RCM of substrates 1 and 9 [41,42,43,44,45] with respect to the corresponding o-tolyl N-substituted catalysts (Table 1 and Table 2), whereas the RCM of the more encumbered 11 appeared slowed down (Table 3). The increase of catalyst bulkiness was counterproductive also in the ROMP of 13 (Scheme 2), where 8-antiGII gave lower conversion to polymer (8%) with respect to its analogous with N-o-tolyl groups, 7-antiGII (44%) [40].

The analogous phosphine-free catalysts 7-HGII and 8-HGII were easily synthesized with standard procedures in good yields (60%–88%) [27]. All obtained phosphine-free catalysts were able to convert 1 to 2 in a few minutes at 60 °C, with performances comparable to HGIItol, as emerged from data reported in Table 1. 7-antiHGII and 8-antiHGII revealed slightly less efficiency in the RCM of 9 (Table 2), and this gap was increased in the RCM of 11, where only 7-synHGII showed an activity comparable with the commercial HGIItol (see data in Table 3).

The phosphine-free Ru catalyst bearing a syn methyl substituted backbone and N-mesityl groups (9-synHGII, Figure 6), reported by Grubbs [22], is able to almost completely convert 1 in 1 h, at 30 °C in CD2Cl2 in the presence of 1 mol % of catalyst and 0.1 M of monomer, being less efficient than HGII. On the other hand at only 15 ppm catalyst loading and 50 °C, the catalyst performed slightly better than HGII, giving over 40% of conversion in 24 h. Less interesting behaviour was recorded for more encumbered substrates, and, in the RCM of 11, even mediocre results were observed (55% conversion in 3 days, Table 3).

The role of the NHC backbone configuration in the RCM of challenging hindered substrates, investigated by theoretical studies on monophosphine o-tolyl N-substituted catalysts, revealed that the rate determining step occurs at the very beginning of the RCM, during the first CM of the substrate, and the corresponding transition state of the syn complex, that induces a syn orientation of the o-tolyl groups, presents lower energy than the anti complex mainly due to steric reasons [27].

The presence of NHC backbone substituents plays a significant additional role, besides the orientation of the N-aryl groups, that is the increase of catalyst stability toward decomposition through C-H activation by restricting rotation around the N-aryl bond [20,22].

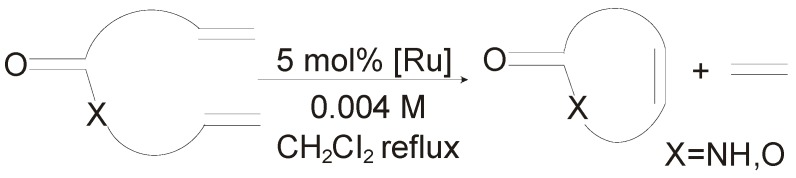

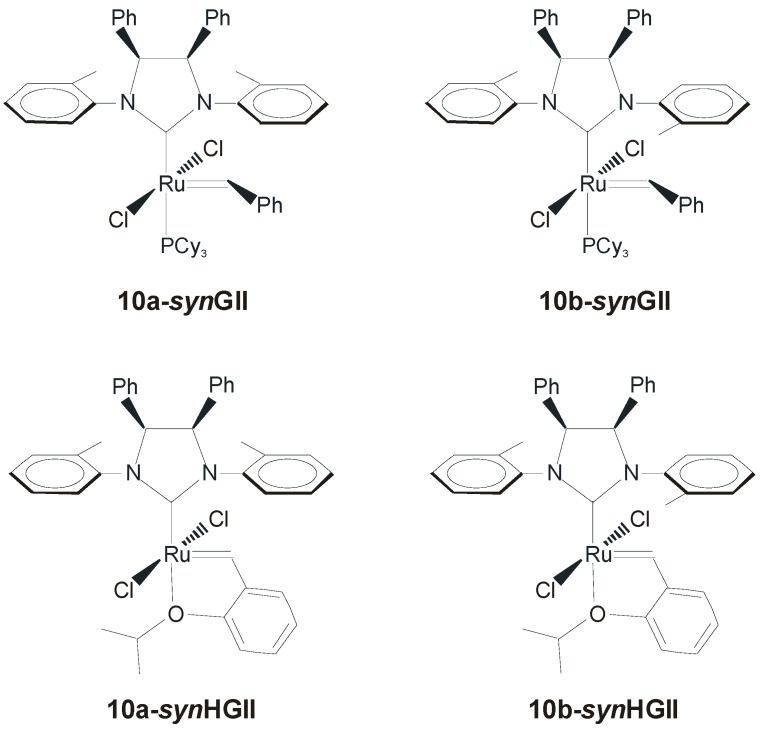

Phosphine-containing catalyst 7-synGII was further tested in the macrocyclic RCM to produce unsaturated lactones and lactams according to the general reaction reported in Scheme 3.

Scheme 3.

Macrocyclic RCM to form 14–17.

Results are collected in Figure 7, where comparison with the behavior of GII and GIItol is also reported. RCM of 14-membered lactones and lactams 14–17 were successfully carried out with 7-synGII that exhibited an intermediate activity in between GII and GIItol [46]. As for E/Z ratios of unsaturated macrocyclic products, they generally reflected the thermodynamic stabilities predicted by DFT calculations for the E and Z isomers. Only small differences, with slightly lower E/Z ratios observed, can be appreciated in the formation of 16 promoted by 7-synGII and GIItol (E/Z = 90:10).

Figure 7.

Macrocyclic RCM products 14–17.

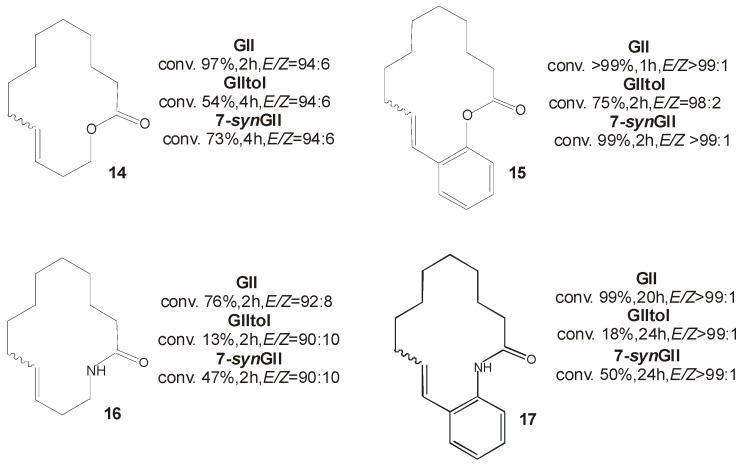

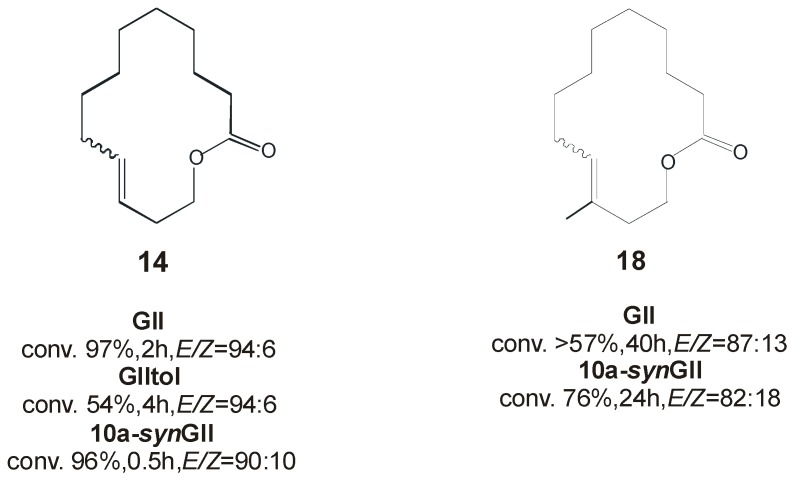

In another work, the same group presented ruthenium catalysts 10-synGII and 10-synHGII (Figure 8) where syn methyl substituents on the NHC backbone were replaced with more encumbered syn phenyl groups [47]. Complex 10-synGII was synthesized in good yields (58%) by a shorter synthetic pathway than that of 7-synGII, starting from the commercially available meso-1,2-diphenylethylenediamine. Surprisingly, two isomeric compounds, corresponding to different conformations of the N-tolyl substituents (10a-synGII and 10b-synGII, Figure 8), were obtained.

Figure 8.

Catalysts with syn phenyl groups on the NHC backbone.

Since complex 7-synGII as well as GIItol exist as a mixture of rotational isomers both in the solid state and in solution [18,26,48], the obtainment of separate, stable rotational isomers was strictly related to the steric pressure exerted by the bulky phenyl groups on the backbone. Phosphine-containing complexes 10a-synGII and 10b-synGII were easily converted in the corresponding phosphine-free catalysts 10a-synHGII (95% yield) and 10b-synHGII (84% yield) by treatment with 2-isopropoxystyrene.

The catalytic behavior of complexes with different N-tolyl conformations was investigated in model RCM reactions and, one year later, this study was extended to some other attractive RCM transformations, as well as other representative metathesis processes (ROMP, CM) [39]. Catalysts with frozen syn orientation of the N-tolyl groups were clearly identified as the most efficient in all the examined reactions, outperforming also the commercially available catalysts GIItol and HGIItol in almost all cases. In the challenging RCM of malonate derivative 11, complex 10a-synGII gave the better result obtained with a phosphine-containing catalysts up to now (92% conversion within 30 min) (Table 4), proving to be more efficient than complexes 7-synGII and GIItol (Table 3). In comparison to the catalytic beaviour of complexes 7-synGII and GIItol, existing as a mixture of inseparable syn and anti NHC conformational isomers [18,26,48], the catalytic behavior of 10a-synGII, possessing frozen syn N-tolyl groups, furnished the unequivocal evidence for the importance of correctly disposed N-aryl groups to successfully accomplish RCM reactions. As for phosphine-free complex 10a-synHGII, although the differences in activity with respect to complexes 10b-synHGII and HGIItol were less pronounced (see Table 3 and Table 4), it turned out to be the most efficient, allowing the ring-closure of the difficult substrate 11 also at a low catalyst loading (0.5 mol %). In the easier RCM of hindered N-tosyl derivatives, such as N-allyl-4-methyl-N-(2-methylallyl)benzenesulfonamide and 4-methyl-N,N-bis(2-methylallyl)benzenesulfonamide, catalyst loadings as low as 0.05–0.1 mol % were required to achieve quantitative conversions [47,39].

Table 4.

RCM of dienes 1, 9 and 11 with catalysts 10a and 10b.

| Diene Substrate | RCM Product | Catalyst a (mol %) | t (min) | Yield (%) | Catalyst b (mol %) | t (min) | Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 10a-synGII (1.0) | 30 | >98 | 10a-synHGII (1.0) | 5 | >99 |

| 1 | 2 | 10b-synGII (1.0) | 60 | 70 | 10b-synHGII (1.0) | 12 | >99 |

| 9 | 10 | 10a-synGII (1.0) | 35 | >95 | 10a-synHGII (1.0) | 6 | >99 |

| 9 | 10 | 10b-synGII (1.0) | 60 | 66 | 10b-synHGII (1.0) | 60 | 95 |

| 11 | 12 | 10a-synGII (5.0) | 30 | 92 | 10a-synHGII (5.0) | 30 | >99 |

| 11 | 12 | 10b-synGII (5.0) | 60 | 44 | 10b-synHGII (5.0) | 120 | 94 |

In the RCM of (±)-linalool, a plant-derived monoterpene alcohol, to form 1-methylcyclopent-2-en-1-ol and isobutylene, the reactivity trend highlighted once again the superior performance of complex 10a-synGII with respect to both its anti conformer 10b and GIItol. As an intriguing secondary aspect, both isomers of 10-synGII, as well as GIItol, were found able to promote the dehydration reaction of the cyclization product (1-methylcyclopent-2-en-1-ol) to well-defined mixtures of methylcyclopentadiene isomers, which represents a viable route to specialized fuel products.

The catalytic potential of 10-synGII and 10-synHGII was also explored in the ring-closing ene-yne metathesis (RCEYM) of (1-(allyloxy)prop-2-yne-1,1-diyl)dibenzene, where the overall reactivity profile puts complexes with syn related N-tolyl groups 10a-synGII and 10a-synHGII among the most efficient catalysts known until now.

In the macrocyclic RCM reactions (Scheme 3) to form the 14-membered lactones 14 and 18, respectively (Figure 9), complex 10a-synGII showed better performance than benchmark catalysts GII and GIItol, proving that correct N-tolyl conformation, combined with increased stability due to NHC backbone substitution, led to highly efficient catalysts.

Figure 9.

Macrocyclic RCM products 14 and 18.

The beneficial role of syn phenyl groups on the NHC backbone was also noticed in the CM of allyl benzene (3) and cis-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (4) and in the ROMP of 1,5-cyclooctadiene (6) (Scheme 1), where higher efficiency compared to commercial catalysts GIItol and HGIItol was found. No influence of the NHC backbone configuration on E/Z selectivity was instead observed in both the transformations.

Therefore, the judicious choice of syn related NHC backbone substituents permits the obtainment of stable Ru metathesis complexes with frozen syn NHC conformation, which seems to be a general requirement to successfully accomplish olefin metathesis reactions. This insight provides the inspiration for further development of NHC-bearing olefin metathesis catalysts.

3. Ruthenium Catalysts Bearing Unsymmetrically N-Substituted NHCs with syn and anti Backbone Configurations

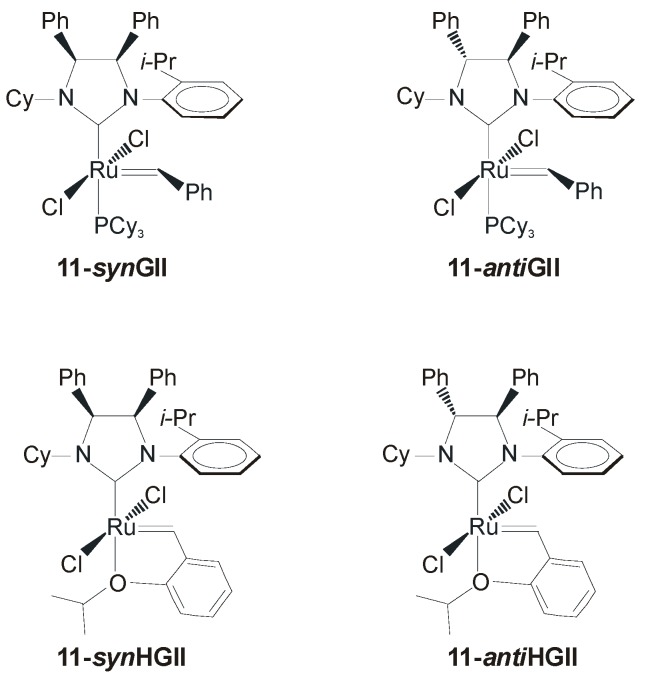

The introduction of differently oriented substituents on the backbone of unsymmetrical NHCs was recently described by Grisi et al. [49]. The synthesis of ruthenium catalysts containing unsymmetrical NHCs that combine phenyl substituents on the backbone in syn or anti stereochemical relationships and N-cyclohexyl, N-isopropylphenyl groups (11-GII and 11-HGII, Figure 10) was easily accomplished in moderate to good yields (45%–64%).

Figure 10.

Catalysts with unsymmetrical NHCs and syn or anti phenyl substituted backbone.

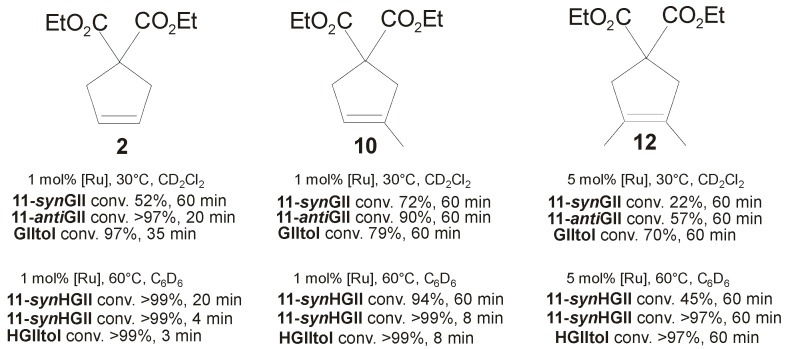

The catalytic properties of these complexes were evaluated in the RCM of diethyl diallylmalonate (1), diethyl allylmethallylmalonate (9), and diethyl dimethallylmalonate (11) to form cycloolefins 2, 10 and 12 (Figure 11). Complexes 11-antiGII and 11-antiHGII performed better than their syn analogues in all of the tested RCM reactions. Notably, anti complexes disclosed an unexpectedly high propensity to the ring closure of the most hindered diolefins 9 and 11, rivaling with the benchmark catalysts GIItol and HGIItol. This is in contrast with results reported for analogous systems incorporating symmetrical N-substituents [26,27], where instead syn isomers were found better performing, and suggests that the impact of backbone configuration of unsymmetrical N-substituted NHCs on catalyst properties is not easily predictable or interpretable.

Figure 11.

RCM to form cycloolefins 2, 10 and 12.

The catalytic behavior of catalysts 11-GII and 11-HGII was also investigated in the CM of allylbenzene (3) and cis-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (4), depicted in Scheme 1. In this reaction, syn complexes 11-synGII and 11-synHGII showed better performances than their anti congeners, reaching high conversions (88% and 72%, respectively) and low E/Z ratios (~3).

Although preliminary, this study clearly indicates that the presence of differently oriented phenyl groups on the backbone of unsymmetrical NHCs can dramatically affect catalytic activity and selectivity, providing a new opportunity in catalyst design.

4. Ruthenium Complexes Bearing NHCs with anti Backbone Configuration in Asymmetric Metathesis

4.1. Symmetrical N-Substituents

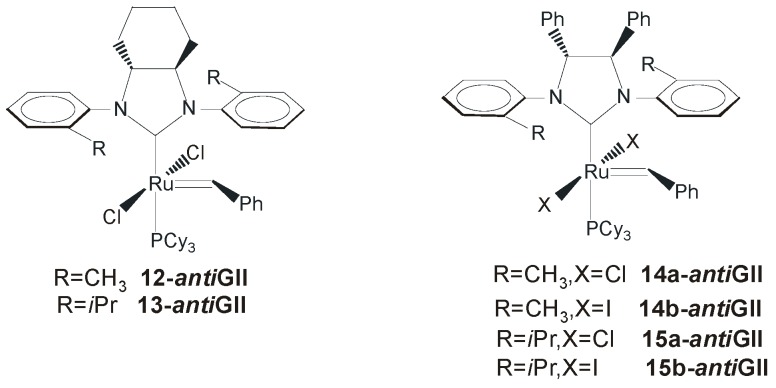

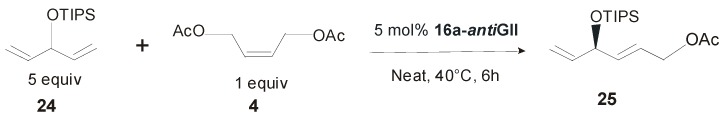

The introduction of chirality into the backbone of the NHC framework was proposed for the first time by Grubbs and coworkers with the synthesis of ruthenium complexes 2-antiGII and 3-antiGII (Figure 3), bearing (1R,2R)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane and (1R,2R)-1,2-diphenylethylenediamine moieties as chiral entities [35]. Subsequently, in 2002, Grubbs’ group reported on the first asymmetric reaction promoted by these catalysts and by chiral catalysts 12-, 13-, 14-and 15-antiGII (Figure 12) [16], obtained in high yields (~70%) starting from commercially available enantiopure 1,2-diamines.

Figure 12.

Catalysts 12-GII–15-GII bearing monodentate NHCs with anti backbone.

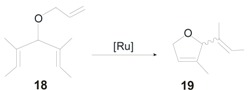

The catalytic behavior of all these complexes was evaluated in the asymmetric ring-closing metathesis (ARCM) of prochiral trienes (Scheme 4). Complexes derived from (1R,2R)-1,2-diphenylethylenediamine (3-, 14- and 15-antiGII) gave higher enantiomeric excesses than those prepared from (1R,2R)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane. Replacement of the mesityl substituent (in 2- and 3-antiGII) with o-tolyl (in 12- and 14-antiGII) or o-isopropylaryl groups (in 13- and 15-antiGII) led to increased enantioselectivity. More significantly, changing in situ the halide ligands of catalysts 12-GII—15-GII from Cl− to I− further improved the enantioselectivity, allowing to reach 90% ee in the ARCM of triene 18 with catalyst 15b-antiGII (Scheme 4). No effects of temperature and solvent on enantioselectivity were observed.

Scheme 4.

Asymmetric ring-closing metathesis reactions.

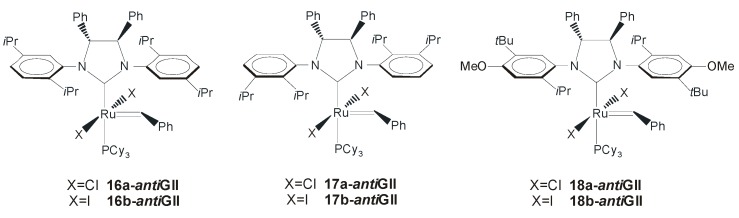

The authors proposed that the chiral information of the NHC backbone was transferred to the ruthenium center through the ortho-substituted N-aryl groups (the so-called “gearing” effect), and, in a later study, a theoretical explanation of the origin of the enantioselectivity of the reaction was also offered by Costabile and Cavallo [50]. The authors rationalized the enantiomeric excesses experimentally obtained by Grubbs essentially as a result of the chiral folding of the N-bonded aromatic groups imposed by the anti Ph groups on the NHC backbone, which imposes a chiral orientation around the Ru=C bond, which, in turn, selects between the two enantiofaces of the substrate. To enhance enantioselectivity and expand the substrate scope of the ARCM, in 2006 Grubbs and coworkers reported chiral complexes 16-antiGII–18-antiGII, differing for the number of substituents and/or for their arrangement on the N-aryl moieties (Figure 13) [51]. Among them, catalysts 16-GII and 18-GII presenting substitution on the N-aryl group of the NHC para to the o-isopropyl group showed enantioselectivities very similar to those of the parent chiral catalyst 15-GII, while catalysts 17a-antiGII and 17b-antiGII with o-isopropyl substituents on the same side of the aromatic ring led to an increase in enantioselectivity.

Figure 13.

Catalysts 16-GII–18-GII bearing monodentate NHCs with anti backbone.

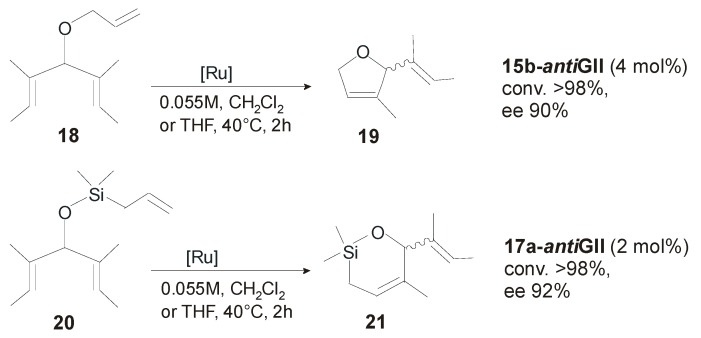

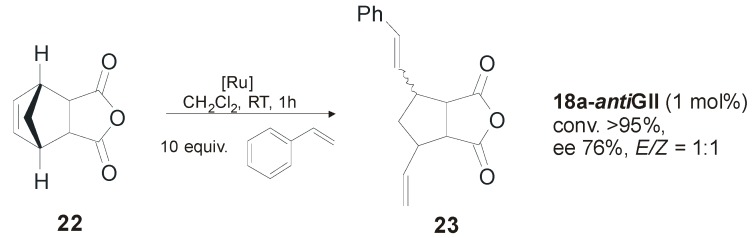

Catalysts 15b- and 17a-antiGII were successfully employed in the desymmetrization of the alkenyl ether- and silyl ether-prochiral trienes forming five- to seven-membered rings. Conversions > 98% and 92% enantiomeric excess were obtained with 17a-antiGII in the ARCM of silyl ether 20 (Scheme 4). In general, the diiodide catalysts showed higher enantioselectivity than the dichloride analogues, although in some cases lower conversions were obtained. The same type of catalysts was used by the Grubbs’ group in the asymmetric ring-opening cross-metathesis (AROCM) for a number of norbornenes and related strained bicycles [52]. In the model reaction of cis-5-norbornene-endo-2,3-dicarboxylic anhydride (22) with styrene (Scheme 5), catalyst 18a-antiGII provided the product 23 with a good enantiomeric excess (76%) and high yield (95%) at low catalyst loading (1 mol %). No selectivity between E and Z isomers was observed, and the use of the analogous diiodide complex 18b-antiGII generated in situ did not lead to significant improvements in reactivity or selectivity.

Scheme 5.

Asymmetric ring-opening cross metathesis.

Moreover, in the same work, the first examples for the most challenging asymmetric metathesis transformations, the asymmetric cross-metathesis (ACM) reactions, were reported. The enantiomeric excesses observed in ACM reactions of meso-diene substrates containing differently encumbered substituents at the allylic carbon atom with cis-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (4) were modest. In the ACM of TIPS-protected 1,4-pentadien-3-ol (24) with 4, catalyst 16a-antiGII gave 25 in 54% yield and 52% ee (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Asymmetric cross-metathesis.

Besides the above described catalysts with phenyl substituents on the backbone, also ruthenium complexes bearing symmetrical NHC ligands with anti methyl groups on the backbone were explored in the ARCM of model substrate 18 (Scheme 4). Catalyst 1-antiGII [21], that bears a C2 symmetric NHC ligand with four stereogenic centers, since, in addition to the R,R methyl substituted backbone, they have S-phenylethyl N-substituents, gave modest enantioselectivity (33% ee) in the asymmetric ring-closure of 18, probably due to the minor role of the chiral phenylethyl groups in transferring the asymmetric information from the backbone to the substrate.

In fact, when o-tolyl or o-isopropylaryl groups replaced phenylethyl groups on nitrogens, catalysts bearing NHCs with S,S methyl substituted backbone (7-antiGII and 8-antiGII) [27] exhibited in the presence of NaI good enantioselectivities (83% ee and 90% ee, respectively), comparable to those obtained by analogous anti phenyl substituted backbone 14b-antiGII and 15b-antiGII.

4.2. Unsymmetrical N-Substituents

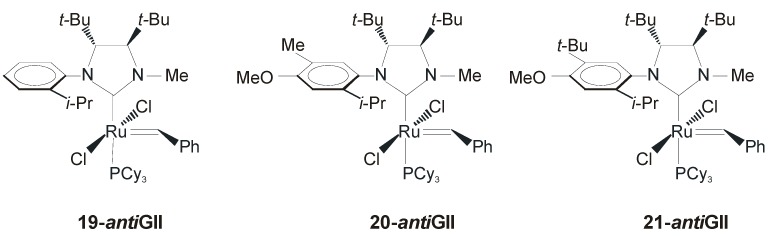

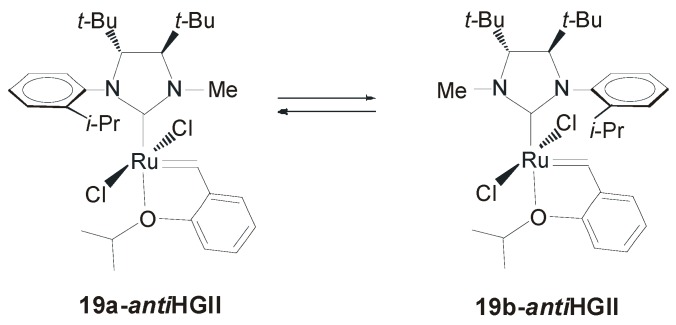

In 2007 Collins and coworkers reported the synthesis of the new complex 19-antiGII bearing a C1-symmetric monodentate NHC ligand [53] (Figure 14). In this system the anti phenyl groups on the backbone were replaced with two anti tert-butyl groups, with the hope that an encumbered and electro-donating group could lead to an increased enentioselectivity and a pronounced reactivity. Considering the high steric hindrance, it seemed necessary to replace one N-aryl substituent with a smaller N-substituent, thus a Me-group was employed. Complex 19-antiGII was obtained in low yield (~30%) starting from enantiopure 1,2-di-tert-butyldiamine.

Figure 14.

Catalysts bearing C1-symmetric monodentate NHC.

For complexes bearing unsymmetrically substituted NHC ligands there are two possible rotational isomers: the syn isomer, in which the N-alkyl substituent lies over the carbene unit and its anti counterpart, in which the N-aryl substituent resides above the carbene. In the case of 19-antiGII, NOE experiment and X-Ray analysis revealed the sole presence of the syn isomer.

Catalyst 19-antiGII was tested in ARCM reactions of several prochiral trienes showing lower enantioselectivities with respect to Grubbs’ chiral catalysts 15a- and 17a-antiGII but, interestingly, the best results obtained in the RCM of standard substrate 18 were obtained without the use of any halide additive (Table 5) [54].

Table 5.

RCM of prochiral triene 18.

|

| Catalyst | ee (%) | Conv. (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19-antiGII a | 82 | >98 | [53] |

| 19-antiGII b | 48 | >98 | [53] |

| 15a-antiGII a | 35 | >98 | [51] |

| 15b-antiGII b | 90 | >98 | [51] |

| 17a-antiGII a | 46 | >98 | [51] |

| 17b-antiGII b | 90 | >98 | [51] |

a Catalyst 2 mol %, CH2Cl2 (0.055 M), 40 °C; b Catalyst 4 mol % with NaI as the additive, THF, 40 °C.

However, the role of the halide addictive with catalysts 19-antiGII is strongly dependent on the size of the ring formed. In fact, while in the ARCM of triene 18 a reduction of the enantioselectivity was observed by adding NaBr or NaI, when a seven-membered ring is involved the addition of the halide is even beneficial. The low enantiomeric excesses registered in desymmetization to form six- and seven-membered rings was attributed to the NHC rotation that could occur during the catalytic cycle causing the erosion of enantiomeric excesses. NHC rotation at room temperature was observed in 19-antiHGII, the Hoveyda version of 19-antiGII, that was formed as a mixture of rotational isomers with clear prevalence of the syn isomer (19a-antiHGII, Figure 15). Notwithstanding, 19-antiHGII showed the same reactivity profile and enantioselectivities as 19-antiGII, suggesting that, although the NHC is rotating at room temperature, the reaction takes place in the conformation in which the N-methyl group is syn to the carbene at a much faster rate than when the N-aryl group is syn to the carbene.

Figure 15.

Rotational isomers of 19-antiHGII.

The same group also reported catalysts 20-antiGII and 21-antiGII (Figure 14), bearing a modified N-aryl substituent, with the expectation that an increased substitution at the N-aryl group would result in a hindered rotation and therefore in a reduction of the supposed interconversion between isomeric active species during the catalytic cycle [54]. 20-antiGII and 21-antiGII were obtained in moderate yields (42%–44%) as a mixture of rotational isomers, in which the syn isomer prevailed. No rotation of the NHC ligand was observed in either catalyst at room temperature. Catalysts 20-antiGII and 21-antiGII showed similar or enhanced catalytic performances in terms of both activity and selectivity with respect to the parent catalyst 19-antiGII. Therefore, all the significant reactivity of 20- and 21-antiGII was assumed to occur from the major syn isomer. Notably, the high levels of asymmetric induction observed in ARCM reactions were achieved without the use of halide additives and, in particular, catalyst 21-antiGII was found to be especially efficient in the asymmetric ring closing metathesis involving six and seven-membered rings (Scheme 7). All the catalysts were also able to promote the asymmetric synthesis of [7] helicene. Using vinylcyclohexane as an additive and C6F6 as a solvent, 21-antiGII gave 80% of enantiomeric excess [55].

Scheme 7.

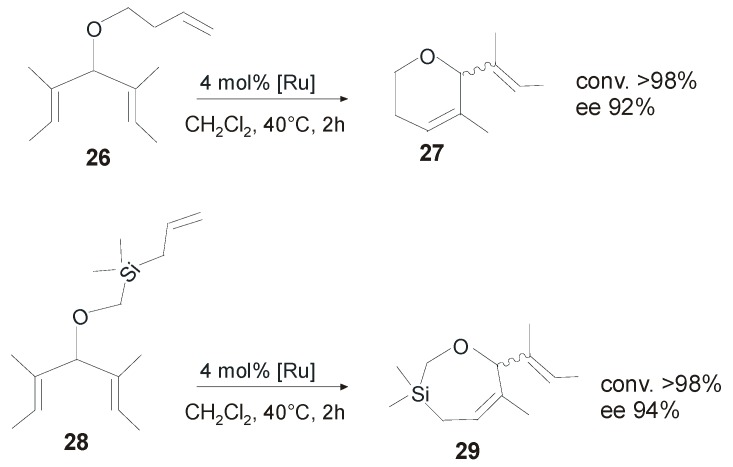

Asymmetric ring closing metathesis of 26 and 28 catalyzed by 21-antiGII.

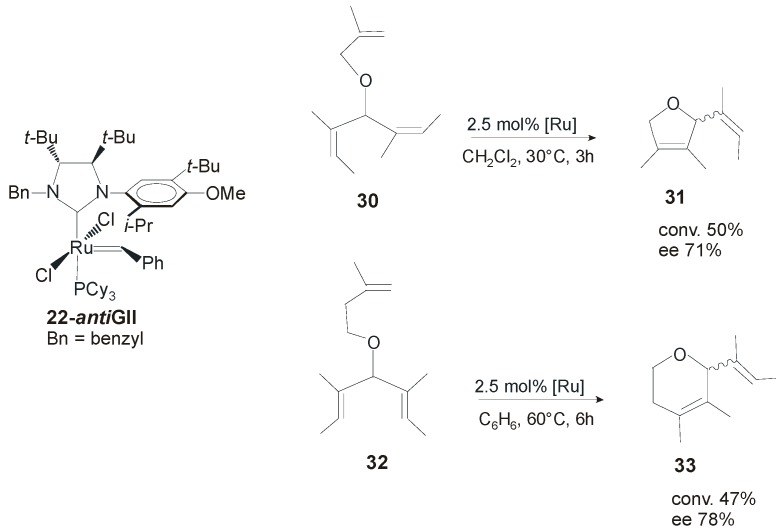

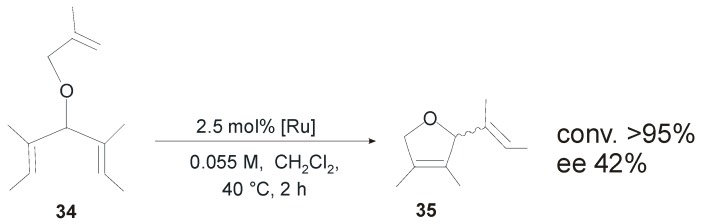

One deficiency of all these complexes is related to their pronounced thermal sensitivity and instability in solution. To overcome this disadvantage, Collins and coworkers synthesized a series of new complexes by varying the nature of the N-alkyl substituents [23].The substitution of the N-Me group with larger N-benzyl or N-propyl substituent led to improved thermal and solution state stability. The new complexes, isolated as mixtures of syn/anti rotational isomers, were evaluated in desymmetrization reactions of meso-trienes and showed lower reactivities than the parent catalyst 19-antiGII. Moreover, lower enantiomeric excesses in almost all cyclization reactions were registered, suggesting an important effect of the N-alkyl group on the observed enantioselectivities. On the other hand, the increased robustness of these catalysts allowed for their application also in more challenging metathesis reaction, such as the ARCM of prochiral trienes affording tetrasubstituted olefins. In the desymmetrization of trienes 30 and 32 catalyst 22-antiGII (in which the anti isomer is the major isomer) gave 31 and 32 in 71% and 78% ee, respectively (Scheme 8) [28].

Scheme 8.

Asymmetric ring closing metathesis of 30 and 32 catalyzed by 22-antiGII.

Enantiopure catalysts 11-antiGII and 11-antiHGII (Figure 10), incorporating a C1-symmetric NHC ligand with anti phenyl groups on the backbone, were tested in the ARCM of prochiral trienes 18 and 34 (Scheme 9) [49]. In the ARCM of 18 both the catalysts gave quantitative conversion to 19 along with low enantiomeric excesses (18%–19%). The use of NaI as an additive led to higher ee values (52%–53% ee), as observed by Grubbs with chiral catalysts bearing C2-symmetric NHCs, and in contrast with the results reported by Collins with catalysts 19-antiGII–22-antiGII, which are actually structurally much more similar to 11-antiGII and 11-antiHGII. In the challenging enantioselective desymmetrization of 34 to afford the tetrasubstituted cycloolefin 35 both the catalysts efficiently performed the cyclization of 34 (>95%), equaling the best results, in terms of conversion and enantioselectivity, obtained by Collins with modified versions of 19-antiGII, in which the N-Me group is replaced with N-propyl group (95% conversion, 43% ee) [28].

Scheme 9.

Asymmetric ring closing metathesis of 34 catalyzed by 11-antiGII and 11-antiHGII.

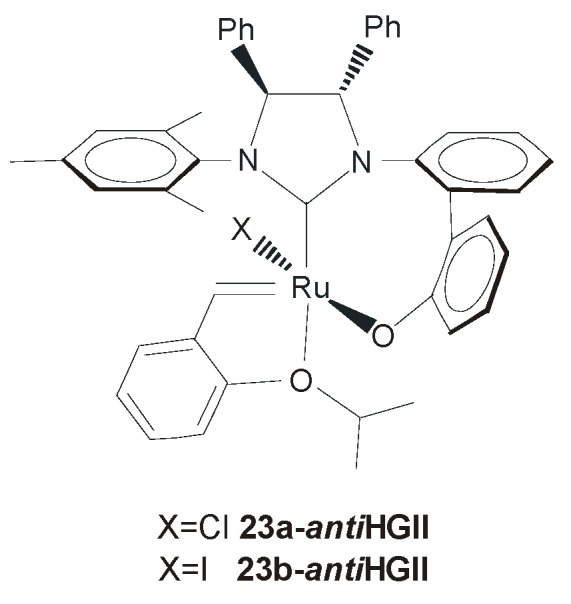

The relevance of the chirality of the NHC backbone in ruthenium complexes with differing N-aryl substituents was also proved by the work of Hoveyda and co-workers. In 2005, they reported the synthesis of the biphenolate NHC complexes 23a-antiHGII and 23b-antiHGII (Figure 16), presenting a C1-symmetric bidentate NHC ligand [56].

Figure 16.

Catalyst 23-antiHGII with chiral bidentate NHC.

Within these systems, the presence of anti groups on the NHC backbone influences the orientation of the achiral biphenyl moiety, which coordinates diastereoselectively to the ruthenium center. In this way, the chiral information on the NHC backbone is efficiently transferred to the metal. Although chromatographic isolation of chloride complex 23a-antiHGII was not possible, both the catalysts 23a- and 23b-antiHGII could be used in situ proving efficiency in a series of AROCM transformations with high enantioselectivities [56,57].

5. Chiral Ruthenium Complexes Bearing Backbone-Monosubstituted NHCs

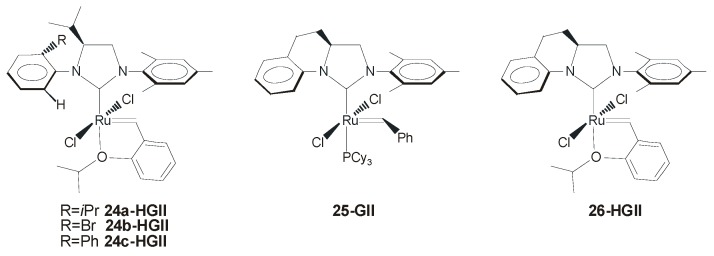

In 2010, a new concept in the design of chiral NHC Ru-based systems was introduced by Blechert and coworkers (Figure 17) [29]. The NHC ligand was characterized by a monosubstituted backbone with a single stereocenter, and two different N-aryl substituents. The mono-ortho-substituted phenyl group next to the stereocenter in the backbone efficiently transfers the chirality to the olefin coordination sphere, and the opposing mesityl group, due to the lack of backbone substituent, adopts a planar arrangement which increases the space for metathesis transformations. These catalysts proved to be highly stable and highly active, providing excellent results in terms of both enantioselectivity and E-selectivity in AROCM reactions. In the AROCM of 22 with 5 equivalents of styrene (Scheme 5), complex 24c-HGII allowed for complete conversion of 22 also at low catalysts loading (0.05 mol %) or at low temperature (−10 °C), along with high enantiomeric excesses (88% and 93%, respectively) and E/Z ratios >30:1. Notably, no halide additives were required for this transformation.

Figure 17.

Catalysts with backbone-monosubstituted NHCs.

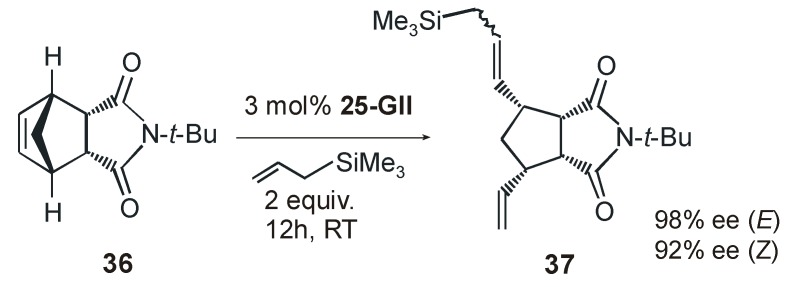

One year later the same group reported ruthenium catalysts 25-GII and 26-HGII coordinated with a new type of chiral NHC ligand presenting an intramolecular linkage between the N-aryl and the backbone which creates a rigid chiral environment around the metal [58]. Catalysts 25-GII and 26-HGII were employed in AROCM with excellent results in terms of activity, enantioselectivity, and substrate scope, however E/Z selectivities were less pronounced than those observed with previous complexes 24-HGII. Significantly, for the first time the AROCM of norbornenes with allyltrimethylsylane as the cross-partner was investigated (e.g., AROCM of 36, Scheme 10). The fixed, non–rotable N-aryl unit in the NHC ligand of catalysts 25-GII and 26-HGII led to higher enantioselectivities for both E/Z stereoisomers of the formed olefin with respect to Grubbs catalyst 18a-antiGII, in which the possible partial N-aryl rotation gives rise to a more flexible reaction pocket, resulting in a lower enantioselectivity [59].

Scheme 10.

AROCM of 36 with allyltrimethylsilane in the presence of 25-GII.

6. Conclusions

Since their discovery, the NHC-containing olefin metathesis ruthenium catalysts have undergone extensive modifications in the ligand shell with the purpose of providing effective catalysts that are readily available, easy to handle, reliable, and highly selective. Significant progress in catalyst design is undoubtedly related to the manipulation of the NHC framework. In this review we focused on the impact of NHC ligands bearing substituents at the backbone in a fixed stereochemical arrangement on the catalytic properties of metathesis ruthenium complexes. The reported results highlight the crucial role of NHC backbone configuration in giving positive enhancement for RCM reactions, especially with sterically demanding olefins, as well as for challenging asymmetric transformations. As a future perspective, we believe that the intriguing behavior of ruthenium complexes bearing unsymmetrical NHCs with different backbone configuration represent an important starting point for further development of metathesis catalysts.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica are gratefully acknowledged.

Author Contributions

V.P., C.C., and F.G. wrote the paper; F.G. conceived, designed and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Grubbs R.H. Handbook of Metathesis. Volume 1–3 Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connon S.J., Blechert S. In: Ruthenium Catalysts and Fine Chemistry. Dixneuf P.H., Bruneau C., editors. Volume 11. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2004. pp. 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fürstner A. Olefin Metathesis and Beyond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3012–3043. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000901)39:17<3012::AID-ANIE3012>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoveyda A.H., Zhugralin A.R. The remarkable metal-catalysed olefin metathesis reaction. Nature. 2007;450:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshmuhk P.H., Blechert S. Alkene metathesis: The search for better catalysts. Dalton Trans. 2007;38:2479–2491. doi: 10.1039/b703164p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Astruc D. The metathesis reactions: From a historical perspective to recent developments. New J. Chem. 2005;29:42–56. doi: 10.1039/b412198h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lozano-Vila A.M., Monsaert S., Bajek A., Verpoort F. Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalysts Derived from Alkynes. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:4865–4909. doi: 10.1021/cr900346r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grela K. Olefin Metathesis Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkinson M.N., Richter C., Schedler M., Glorius F. An overview of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nature. 2014;510:485–496. doi: 10.1038/nature13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan S.P. N-Heterocyclic Carbenes: Effective Tools for Organometallic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vougioukalakis G.C., Grubbs R.H. Ruthenium-Based Heterocyclic Carbene-Coordinated Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1746–1787. doi: 10.1021/cr9002424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samojlowicz C., Bieniek M., Grela K. Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalysts Bearing N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3708–3742. doi: 10.1021/cr800524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tornatzky J., Kannenberg A., Blechert S. New catalysts with unsymmetrical N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8215–8225. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30256j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamad F.B., Sun T., Xiao S., Verpoort F. Olefin metathesis ruthenium catalysts bearing unsymmetrical heterocylic carbenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:2274–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahane S., Bruneau C., Fischmeister C. Z Selectivity: Recent Advances in one of the Current Major Challenges of Olefin Metathesis. ChemCatChem. 2013;5:3436–3459. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201300688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seiders T.J., Ward D.W., Grubbs R.H. Enantioselective Ruthenium-Catalyzed Ring-Closing Metathesis. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3225–3228. doi: 10.1021/ol0165692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritter T., Day M.W., Grubbs R.H. Rate Acceleration in Olefin Metathesis through a Fluorine-Ruthenium Interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11768–11769. doi: 10.1021/ja064091x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart I.C., Ung T., Pletnev A.A., Berlin J.M., Grubbs R.H., Schrodi Y. Highly Efficient Ruthenium Catalysts for the Formation of Tetrasubstituted Olefins via Ring-Closing Metathesis. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1589–1592. doi: 10.1021/ol0705144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berlin J.M., Campbell K., Ritter T., Funk T.W., Chlenov A., Grubbs R.H. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Ring-Closing Metathesis to Form Tetrasubstituted Olefins. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1339–1342. doi: 10.1021/ol070194o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung C.K., Grubbs R.H. Olefin Metathesis Catalyst: Stabilization Effect of Backbone Substitutions of N-Heterocyclic Carbene. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2693–2696. doi: 10.1021/ol800824h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grisi F., Costabile C., Gallo E., Mariconda A., Tedesco C., Longo P. Ruthenium-Based Complexes Bearing Saturated Chiral N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands: Dynamic Behavior and Catalysis. Organometallics. 2008;27:4649–4656. doi: 10.1021/om800459y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhn K.M., Bourg J.-B., Chung C.K., Virgil S.C., Grubbs R.H. Effects of NHC-Backbone Substitution on Efficiency in Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5313–5320. doi: 10.1021/ja900067c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savoie T., Stenne B., Collins S.K. Improved Chiral Olefin Metathesis Catalysts: Increasing the Thermal and Solution Stability via Modification of a C1-Symmetrical N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligand. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:1826–1832. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200900269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieille-Petit L., Luan X., Gatti M., Blumentritt S., Linden A., Clavier H., Nolan S.P., Dorta R. Improving Grubbs’ II type ruthenium catalysts by appropriately modifying the N-heterocyclic carbene ligand. Chem. Commun. 2009;18:3783–3785. doi: 10.1039/b904634h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatti M., Vieille-Petit L., Luan X., Mariz R., Drinkel E., Linden A., Dorta R. Impact of NHC Ligand Conformation and Solvent Concentration on the Ruthenium-Catalyzed Ring-Closing Metathesis Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9498–9499. doi: 10.1021/ja903554v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grisi F., Mariconda A., Costabile C., Bertolasi V., Longo P. Influence of syn and anti Configurations of NHC Backbone on Ru-Catalyzed Olefin Metathesis. Organometallics. 2009;28:4988–4995. doi: 10.1021/om900497q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costabile C., Mariconda A., Cavallo L., Longo P., Bertolasi V., Ragone F., Grisi F. The Pivotal Role of Symmetry in the Ruthenium-Catalyzed Ring-Closing Metathesis of Olefins. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:8618–8629. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenne B., Timperio J., Savoie J., Dudding T., Collins S.K. Desymmetrizations Forming Tetrasubstituted Olefins Using Enantioselective Olefin Metathesis. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2032–2035. doi: 10.1021/ol100511d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiede S., Berger A., Schlesiger D., Rost D., Lühl A., Blechert S. Highly Active Chiral Ruthenium-Based Metathesis Catalysts through a Monosubstitution in the N-Heterocyclic Carbene. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2010;49:3972–3975. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dinger M.B., Nieczypor P., Mol J.C. Adamantyl-Substituted N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands in Second-Generation Grubbs-Type Metathesis Catalysts. Organometallics. 2003;22:5291–5296. doi: 10.1021/om034062k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledoux N., Allaert B., Pattyn S., Mierde H.V., Vercaemst C., Verpoort F. N,N′-Dialkyl- and N-Alkyl-N-mesityl-Substituted N-Heterocyclic Carbenes as Ligands in Grubbs Catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:4654–4661. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louie J., Grubbs R.H. Highly Active Metathesis Catalysts Generated in Situ from Inexpensive and Air-Stable Precursors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:247–249. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010105)40:1<247::AID-ANIE247>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledoux N., Linden A., Allaert B., Vander Mierde H., Verpoort F. Comparative Investigation of Hoveyda–Grubbs Catalysts bearing Modified N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:1692–1700. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200700042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritter T., Hejl A., Wenzel A.G., Funk T.W., Grubbs R.H. A Standard System of Characterization for Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. Organometallics. 2006;25:5740–5745. doi: 10.1021/om060520o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholl M., Ding S., Lee C.W., Grubbs R.H. Synthesis and Activity of a New Generation of Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalysts Coordinated with 1,3-Dimesityl-4,5-dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene Ligands. Org. Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weigl K., Köhler K., Dechert S., Meyer F. Synthesis and Structure of N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes with Tethered Olefinic Groups: Application of the Ruthenium Catalyst in Olefin Metathesis. Organometallics. 2005;24:4049–4056. doi: 10.1021/om0503242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vehlow K., Gessler S., Blechert S. Deactivation of Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts through Intramolecular Carbene-Arene Bond Formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:8082–8085. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chooi S.Y.M., Leung P., Ng S., Quek G.H., Sim K.Y. A simple route to optically pure 2,3-diaminobutane. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1991;2:981–982. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)86141-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perfetto A., Costabile C., Longo P., Grisi F. Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts with Frozen NHC Ligand Conformations. Organometallics. 2014;33:2747–2759. doi: 10.1021/om5001452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mariconda A., Grisi F., Granito A., Longo P. Stereoselective Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of 7-tert-Butoxy-bicyclo[2,2,1]hepta-2,5-diene by NHC–Ruthenium Catalysts. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013;214:1973–1979. doi: 10.1002/macp.201300069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jafarpour L., Stevens E.D., Nolan S.P. A sterically demanding nucleophilic carbene: 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene). Thermochemistry and catalytic application in olefin metathesis. J. Organomet. Chem. 2000;606:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fürstner A., Ackermann L., Gabor B., Goddard R., Lehmann C.W., Mynott R., Stelzer F., Thiel O.R. Comparative Investigation of Ruthenium-Based Metathesis Catalysts Bearing N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Ligands. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:3236–3253. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010803)7:15<3236::AID-CHEM3236>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dinger M.B., Mol J.C. High Turnover Numbers with Ruthenium-Based Metathesis Catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002;344:671–677. doi: 10.1002/1615-4169(200208)344:6/7<671::AID-ADSC671>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Courchay F.C., Sworen J.C., Wagener K.B. Metathesis Activity and Stability of New Generation Ruthenium Polymerization Catalysts. Macromolecules. 2003;36:8231–8239. doi: 10.1021/ma0302964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urbina-Blanco C.A., Leitgeb A., Slugovc C., Bantreil X., Clavier H., Slawin A.M.Z., Nolan S.P. Olefin Metathesis Featuring Ruthenium Indenylidene Complexes with a Sterically Demanding NHC Ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:5045–5053. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grisi F., Costabile C., Grimaldi A., Viscardi C., Saturnino C., Longo P. Synthesis of Unsaturated Macrocycles by Ru-Catalyzed Ring-Closing Metathesis: A Comparative Study. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012;2012:5928–5934. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201200960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perfetto A., Costabile C., Longo P., Bertolasi V., Grisi F. Probing the Relevance of NHC Ligand Conformations in the Ru-Catalysed Ring-Closing Metathesis Reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:10492–10496. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart I.C., Benitez D., O’Leary D.J., Tkatchouk E., Day M.W., GoddardIII W.A., Grubbs R.H. Conformations of N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands in Ruthenium Complexes Relevant to Olefin Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1931–1938. doi: 10.1021/ja8078913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paradiso V., Bertolasi V., Grisi F. Novel Olefin Metathesis Ruthenium Catalysts Bearing Backbone-Substituted Unsymmetrical NHC Ligands. Organometallics. 2014;33:5932–5935. doi: 10.1021/om500731k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costabile C., Cavallo L. Origin of Enantioselectivity in the Asymmetric Ru-Catalyzed Metathesis of Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9592–9600. doi: 10.1021/ja0484303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Funk T.W., Berlin J.M., Grubbs R.H. Highly Active Chiral Ruthenium Catalysts for Asymmetric Ring-Closing Olefin Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1840–1846. doi: 10.1021/ja055994d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berlin J.M., Goldberg S.D., Grubbs R.H. Highly Active Chiral Ruthenium Catalysts for Asymmetric Cross- and Ring-Opening Cross-Metathesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7591–7595. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fournier P., Collins S.K. A Highly Active Chiral Ruthenium-Based Catalyst for Enantioselective Olefin Metathesis. Organometallics. 2007;26:2945–2949. doi: 10.1021/om700312c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fournier P., Savoie J., Stenne B., Bédard M., Grandbois A., Collins S.K. Mechanistically Inspired Catalysts for Enantioselective Desymmetrizations by Olefin Metathesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:8690–8695. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grandbois A., Collins S.K. Enantioselective Synthesis of [7]Helicene: Dramatic Effects of Olefin Additives and Aromatic Solvents in Asymmetric Olefin Metathesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:9323–9329. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Veldhuizen J.J., Campbell J.E., Giudici R.E., Hoveyda A.H. A Readily Available Chiral Ag-Based N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complex for Use in Efficient and Highly Enantioselective Ru-Catalyzed Olefin Metathesis and Cu-Catalyzed Allylic Alkylation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6877–6882. doi: 10.1021/ja050179j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giudici R.E., Hoveyda A.H. Directed Catalytic Asymmetric Olefin Metathesis. Selectivity Control by Enoate and Ynoate Groups in Ru-Catalyzed Asymmetric Ring-Opening/Cross-Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3824–3825. doi: 10.1021/ja070187v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kannenberg A., Rost D., Eibauer S., Tiede S., Blechert S. A Novel Ligand for the Enantioselective Ruthenium-Catalyzed OlefinMetathesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:3299–3302. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ragone F., Poater A., Cavallo L. Flexibility of N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands in Ruthenium Complexes Relevant to Olefin Metathesis and Their Impact in the First Coordination Sphere of the Metal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4249–4258. doi: 10.1021/ja909441x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]