Abstract

Prenatal exposure to alcohol can result in a range of neurobehavioral impairments and physical abnormalities. The term fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) encompasses the outcomes of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE), the most severe of which is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). These effects have lifelong consequences, placing a significant burden on affected individuals, caregivers, and communities. Caregivers of affected children often report that their child has sleep problems, and many symptoms of sleep deprivation overlap with the cognitive and behavioral deficits characteristic of FASD. Alcohol-exposed infants and children demonstrate poor sleep quality based on measures of electroencephalography (EEG), actigraphy, and questionnaires. These sleep studies indicate a common theme of disrupted sleep pattern, more frequent awakenings, and reduced total sleep time. However, relatively little is known about circadian rhythm disruption, and the neurobehavioral correlates of sleep disturbance in individuals with PAE. Furthermore, there is limited information available to healthcare providers about identification and treatment of sleep disorders in patients with FASD. This review consolidates the findings from studies of infant and pediatric sleep in this population, providing an overview of typical sleep characteristics, neurobehavioral correlates of sleep disruption, and potential avenues for intervention in the context of PAE.

Keywords: prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE), fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), sleep, circadian rhythm, neurobehavior

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) refer to the range of adverse physical, behavioral, and cognitive effects caused by prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE; Chudley et al., 2005). In the United States, the prevalence of FASD is estimated to be 2.5–4.3% (Roozen et al., 2016), making it more prevalent than autism spectrum disorders (Christensen et al., 2016). Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which lies on the severe end of the spectrum, affects an estimated 6.7 per 1000 individuals (Roozen et al., 2016). Although a diagnosis of FAS requires the presence of facial dysmorphology (Del Campo and Jones, 2017), PAE most profoundly affects brain development and consequent behavioral and cognitive abilities (Donald et al., 2015).

Individuals across the spectrum of diagnoses subsumed under FASD have primary impairments in many behavioral and cognitive domains, including intellectual capacity, executive functioning, attention, learning, and memory (Mattson et al., 2011; Riley et al., 2011). Children with FASD may exhibit impaired intellectual functioning (Mattson et al., 1997; Dalen et al., 2009) and demonstrate a generalized deficit in information processing and integration (Kodituwakku, 2009). This results in greater difficulty with complex tasks, particularly those that place higher demands on executive functioning (Kodituwakku, 2009; Mattson et al., 2011; Khoury et al., 2015). Children with FASD also show impairment in emotional processing (Greenbaum et al., 2009; Petrenko et al., 2017), and parents report significantly more behavioral and emotional problems compared to IQ-matched controls (Greenbaum et al., 2009; Mattson and Riley, 2000). As a result of these deficits, individuals with FASD experience increased rates of psychopathology, academic difficulties, trouble with the law, and substance use problems, negatively impacting their daily functioning and the well-being of their families and caregivers (Mattson et al., 2011; Streissguth et al., 1996; Fryer et al., 2007; Pei et al., 2011; Popova et al., 2011).

Although cognitive and emotional development have been well described in individuals with FASD, there are other behavioral consequences of PAE that may further exacerbate cognitive and emotional functioning, such as altered stress reactions and sleep disturbances. Yet, these behaviors have not been well studied in the FASD population. Sleep quality, in particular, can be affected by PAE, and caregivers of children with FASD often report that their child has problems with sleep (Wengel et al., 2011). Furthermore, animals exposed to alcohol in utero have demonstrated long-term disruption in circadian rhythmicity (Handa et al., 2007). However, the effects of PAE on sleep quality and circadian rhythms have been understudied, and the possibility that sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances contribute to deficits in other domains in individuals with FASD has not been explored. This review will focus on the current state of research surrounding the relationship between PAE, sleep, and circadian rhythm in humans. The following sections also provide background information on typical sleep characteristics in infants and children, neurobehavioral consequences of sleep disruption, potential avenues for intervention, and future research directions.

Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Clock Genes

Although the true physiological function of sleep remains unknown, sleep appears to be a universal process across species (Dahl, 1996; Siegel, 2009) and is one of the many biochemical, physiological, and behavioral activities regulated by the circadian clock. The master circadian pacemaker, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, has an endogenous periodicity of just over 24 hours, but is synchronized each day via environmental cues (e.g., light) to the 24-hour light-dark cycle of the earth (van Esseveldt et al., 2000). Specific clock genes (i.e., Period [Per1, Per2, Per3]; Clock; Bmal1, Cryptochrome [Cry1, Cry2]) produce proteins that generate biological rhythms at the cellular level throughout the body, which are regulated by transcriptional-translational feedback loops that take approximately 24 hours to complete (Ko and Takahashi, 2006). Environmental factors that alter the expression of these genes, such as alcohol, can have downstream effects on circadian functions, including sleep (Sarkar, 2012).

Sleep is crucial to early brain development, and in the first five years of life, the average child spends more time asleep than in all waking activities combined (Dahl, 1996). During this time, the sleep-wake cycle pattern changes considerably, with total sleep time decreasing gradually from infancy through childhood (Feinberg, 1974). Newborn and infant sleep is classified into three stages: rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep, previously termed active sleep; non-REM (NREM) sleep, previously termed quiet sleep; and transitional sleep, previously termed indeterminate sleep (Anders et al., 1971; Berry et al., 2015). REM sleep is characterized by rapid eye movements, irregular respiration, irregular heart rate, low or absent muscle tone, and a range of involuntary motor behaviors (e.g., facial grimaces, clonic jaw jerks, muscle twitches, large athetoid limb movements). Defining features of NREM sleep are regular respiration and heart rate, chin muscle tone, and a lack of body and eye movements. Transitions between wake and sleep are classified as transitional sleep, when features of the sleep stage are discordant and do not fit the definition of REM or NREM sleep (Grigg-Damberger, 2016).

As infants mature, the proportion of time spent in transitional sleep decreases. By 3 to 6 months of age, NREM sleep can be further differentiated into three different subtypes: N1, N2, and N3. These stages are defined by parameters measured via polysomnography, including electroencephalography (EEG), eye movements, and muscle tone (See Table 1; Iber et al., 2007). Typical sleep architecture follows a 90-minute cycle, repeating three to six times throughout the night, with each cycle consisting of alternating stages of NREM and REM sleep (Iber et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), and respiratory characteristics of each sleep stage, as defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (Iber et al., 2007).

| Stage | Brain Activity | Eye Movements (EOG) | Muscle Tone (EMG) | Breathing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakefulness | Alpha rhythm (8–13 Hz) | Eye blinks Reading/rapid eye movements |

Normal or high chin muscle tone | |

| NREM (quiet sleep) | ||||

| N1 | Low amplitude (4–7 Hz) Vertex sharp waves Hypnagogic hypersynchrony (bursts of 3–4.5 Hz) |

Slow, conjugate, regular, sinusoidal eye movements | Normal chin muscle tone Few body movements |

Regular, rhythmic |

| N2 | Low amplitude, mixed frequency EEG K-complexes (well-delineated negative sharp wave) Sleep spindles (bursts of 11–16 Hz waves) |

No or slow eye movements | Variable, can be very low | Regular, rhythmic |

| N3 | Slow wave (0.5–2 Hz), large amplitude | Typically none | Variable, can be very low | Regular, rhythmic |

| REM (active sleep) | Low amplitude, mixed frequency EEG Triangular, serrated, “sawtooth” waves (2–6 Hz) |

Rapid eye movements: conjugate, irregular, sharply peaked, <500 msec | Lowest of any sleep stage Short, irregular bursts of muscle activity <0.25 sec |

Irregular |

Measurement of sleep and circadian rhythm

The gold standard of sleep measurement is polysomnography, which uses EEG to directly monitor electrophysiological activity. Electrodes are placed directly on the scalp and body and provide measurements of brain activation, eye movement, skeletal muscle activation, and heart rate (Markovich et al., 2014). Actigraphy is another recommended method for detecting sleep quantity and circadian patterns, and is a less expensive, non-invasive alternative to polysomnography (Holley et al., 2009). This technology uses a small accelerometer, generally in the form of a wristband, to detect movement. Movement data are sampled several times per second for up to several weeks, and provide an objective and more ecologically valid measure of activity/inactivity and sleep/wake parameters (e.g., sleep onset latency, total sleep time, percent of time spent asleep, total wake time, percent of time spent awake, number of awakenings; Ancoli-Israel et al., 2003). Actigraphy can be used to evaluate sleep variability in insomnia, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, and treatment effects for sleep apnea, and is also useful for studying populations for whom polysomnography would be impractical (Morgenthaler et al., 2007). Previous studies have found that, although actigraphy has high sensitivity (i.e., ability to detect sleep), its specificity (i.e., ability to detect wake) is poor (Sadeh, 2011). Actigraphy measurement is often coupled with self-report questionnaires or sleep logs to provide a more complete picture of sleep quality and disturbance (Morgenthaler et al., 2007).

The Role of Sleep in Brain Development

Before birth, the human fetus demonstrates four distinct behavioral states that reflect fetal nervous system activity. These behavioral states parallel the sleep-wake stages of infants and children, and are classified using fetal heart patterns, body movements, and eye movements into four states: quiet sleep (analogous to NREM), active sleep (analogous to REM), quiet wake, and active wake (Nijhuis et al., 1982). To maintain a behavioral state, such as quiet/NREM sleep, neural integrity is required; thus, the stability and organization of behavioral states are used as a measure of neurophysiologic development, integrity, and maturity (Mulder et al., 1998).

Research suggests that the emergence of sleep stages early in life may be indicative of brain maturation levels, and REM sleep, in particular, may further contribute to proper brain development (Mirmiran, 1995). Newborn infants spend approximately two-thirds of the day asleep, about eight hours of which is spent in REM sleep (Blumberg, 2010; Roffwarg et al., 1966). One overarching theory is that the formation of mature neural circuitry is activity-dependent, such that early sensory experience directs the developmental course of the nervous system (Marks et al., 1995). In animals, the formation of neural circuity in the visual, auditory, and somatosensory systems is activity-dependent (Masino and Knudsen, 1990; Simons and Land, 1987; Nicolelis et al., 1991; Uhlrich et al., 1988), and deprivation of sensory input can affect neuronal morphology, connectivity, and synaptic density (Fox and Wong, 2005; Masino and Knudsen, 1990). Likewise, it has been hypothesized that the neural stimulation arising from REM sleep may provide adjunct afferent input that guides the course of neural development and shapes synaptic connectivity, particularly during the time in which exogenous activation (i.e., wakefulness) is limited (e.g., in utero; Marks et al., 1995; Mirmiran, 1995; Roffwarg et al., 1966; Shaffery et al., 2002). Furthermore, studies suggest that the neuronal activity generated during REM sleep is important to the synaptic changes that occur during memory consolidation (Shaffery et al., 2002).

Empirical tests of this hypothesis in newborn cats and ferrets have found that brainstem-generated ponto-geniculo-occipital (PGO) waves that occur during REM sleep are instrumental in the neural differentiation and development of the lateral geniculate nucleus, which transmits visual information from the retina to the visual cortex (Davenne and Adrien, 1984; Davenne and Adrien, 1987; Davenne et al., 1989; Meister et al., 1991; Penn and Shatz, 1999; Wong et al., 1993). Furthermore, rat pups deprived of REM sleep demonstrate slowed development of the visual cortex, prolonging its immature, plastic state (Shaffery et al., 2002). Though these effects are difficult to study in humans, infants with more mature neonatal sleep patterns during the first two days of life score higher on measures of mental development at six months of age (Freudigman and Thoman, 1993; Gertner et al., 2002). Additionally, evidence suggests that specific sleep stages and patterning are related to the processing of different types of learning and memory (Stickgold and Walker, 2007). For example, NREM slow wave sleep (i.e., N3) has been associated with consolidation of non-emotional declarative memories, whereas REM sleep is important to emotional memory consolidation (Spencer et al., 2017; Backhaus et al., 2008), and NREM N2 plays a role in motor and procedural memory (Barakat et al., 2011). Disrupted sleep cycle organization has also been related to impaired recall of verbal material (Ficca et al., 2000). The specific mechanisms underlying these complex relationships remain unclear, and it is likely that there is a bidirectional interaction between sleep quality and disrupted neural activity. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that early sleep characteristics are not only important to neurodevelopment, but may also be predictive of later neurobehavioral function. Thus, the effects of sleep disruption can be far-reaching, to the extent that poor sleep may further impact neural organization and behavioral outcome in individuals with PAE.

Alcohol, Circadian Rhythms, and Sleep

Developmental Alcohol Exposure and Circadian Rhythm

Both human and animal studies have shown that behavioral, endocrinological, and immunological processes regulated by circadian rhythm are also disrupted by acute alcohol intake (Sarkar, 2012; Chen et al., 2006; Danel et al., 2009; Devaney et al., 2003; Arjona et al., 2006). Developmental alcohol exposure appears to have similar negative consequences on circadian rhythmicity, potentially via alcohol-induced damage to the SCN. Normal function of the SCN is critical to the coordination of other internal physiological processes with the sleep-wake cycle, and dysfunction of the SCN has the potential to disrupt sleep and other physiological outcomes (Handa et al., 2007). Earnest et al. (2001) posited that developmental alcohol-induced damage to the SCN likely would not completely disrupt circadian rhythmicity, but would cause more subtle changes, leading to permanently reduced rhythm amplitude, circadian period alterations, and reduced SCN response to light entrainment. Indeed, developmental exposure to ethanol in rats has been found to produce changes to the endogenous rhythmicity of the SCN circadian clock that persist into adulthood, as well as alterations in the rat clock genes Per1, Per2, and Per3 (Rojas et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2006; Allen et al., 2004; Farnell et al., 2008). These genes are involved in circadian control, and such alterations may be a biomarker of poor coordination of phase shifts in response to a changing light-dark signal (Chen et al., 2006). In fact, animal studies have shown that developmental alcohol exposure permanently alters phase-shifting responses to light (Farnell et al., 2004), and both deep body temperature and activity levels take longer to synchronize to changes in the light-dark cycle (Sei et al., 2003; Sakata-Haga et al., 2006). In a rodent model, late gestational alcohol exposure reduces SCN BDNF (Allen et al., 2004), and fetal ethanol exposure was found to affect SCN function, serotonin function, and melatonin release, all three of which are crucial to inducing and regulating sleep (Chen et al., 2006; Weinberg et al., 2008; Cajochen et al., 2003).

Disruptions in the circadian system may also be related to deficits in neuropsychological performance and social functioning, as well as mood dysregulation and affective disorders (Gruber et al., 2000; Ichikawa et al., 1993; Nestler et al., 2002; Barnard and Nolan, 2008; McClung, 2007), some of which are seen in individuals with FASD. Therefore, circadian rhythm disruption may further contribute to impairments in cognition and behavior in individuals affected by PAE (Sakata-Haga et al., 2006). Furthermore, these alterations in circadian rhythm appear to persist into adulthood in the animal model; thus, the disruption of circadian rhythm could be a useful long-term biological marker of PAE.

PAE and Sleep

The effects of PAE on sleep have primarily been investigated in infants, although a few studies have examined sleep during gestation, as well as childhood. These studies have found abnormalities in several general areas, including behavioral state organization (i.e., the proportion and sequencing of different sleep-wake stages), sleep patterns, brain activity as measured by EEG, and sleep movements. See Table 2 for a summary of findings.

Table 2.

Summary of sleep study findings reported in infants and children with prenatal alcohol exposure. CSHQ = Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Owens et al., 2000b); EEG = electroencephalography; FASD = fetal alcohol spectrum disorders; PAE = prenatal alcohol exposure; REM = rapid eye movement; NREM = non-rapid eye movement

| Study | Type of Study | Participants | Measurements | Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional | N = 33 children with FASD, 4–12 years old | Polysomnography (n = 5), CSHQ | 85% of caregivers reported that their child had clinically elevated levels of sleep problems. Polysomnography in 5 children indicated fragmented sleep and mild sleep disordered breathing. |

| Chernick et al. (1983) | Cross-sectional |

N = 70 newborn infants n = 17 alcohol-exposed n = 17 alcohol-matched controls n = 18 smoking-exposed n = 18 smoking-matched controls |

EEG recordings of 90–120 minutes at 3 days old, spectral analysis of EEG | Infants of alcoholic mothers had significantly greater EEG power (i.e., hypersynchrony) in quiet, indeterminate, and REM sleep. EEG power did not differ between infants of smokers and controls. |

| Goril et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | N = 36 children with FASD, 6–18 years old | Polysomnography, dim light melatonin onset test, clinical interview | 78% of sample had significant sleep disturbance (e.g., low sleep efficiency, increased sleep fragmentation). 58% were diagnosed with a sleep disorder, and 79% had an abnormal melatonin secretion curve. |

| Hanft et al. (2006) | Longitudinal |

n = 17 substance-exposed infants n = 17 age-matched non-exposed infants |

Time-lapse videosomnography at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of age | No group differences in proportion of sleep stages. Substance-exposed infants had significantly shorter “Longest Sleep Period” at 6 months, and shorter “Total Sleep Time” at 3, 6, and 12 months. |

| Havlicek et al. (1977) | Cross-sectional |

N = 52 infants n = 26 babies of alcoholic mothers n = 26 babies of healthy mothers |

EEG recordings of 90–120 minutes in infants 38–42 weeks postconceptional age | Infants of alcoholic mothers demonstrated significantly higher EEG power in quiet, indeterminate, and REM sleep; 150–200% higher than that of controls. |

| Ioffe & Chernick (1988) | Cross-sectional |

N = 441 neonates born to mothers who drank varying amounts of alcohol during pregnancy n = 134 abstainers n = 103 occasional drinkers n = 64 moderate drinkers n = 59 binge drinkers n = 81 alcoholics |

EEG studies during spontaneous sleep in infants 36 to 48 hours of age, at 30 to 40 weeks gestation | Infants of occasional drinkers and alcoholic mothers showed elevated total power of EEG across gestational age. EEG maturation was abnormal in alcohol-exposed infants, and was most affected in infants of binge drinking mothers. |

| Ioffe & Chernick (1990) | Longitudinal | N = 38 infants with varying levels of alcohol exposure | EEG sleep study at 40 weeks’ postconceptional age; Bayley developmental assessment at 6 weeks to 9 months of age; Subset given a McCarthy developmental assessment between 4–7 years old | Alcohol-exposed infants had significantly increased EEG power and lower motor and mental Bayley test scores, compared to controls. Increased EEG power during REM was correlated with worse motor development scores, and increased power during quiet sleep was correlated with worse mental development scores. |

| Ioffe et al. (1984) | Cross-sectional |

N = 42 infants, prospectively identified n = 11 preterm infants with heavy PAE (>2oz alcohol/day) n = 11 control infants with minimal exposure (<1oz alcohol on any occasion) n = 10 non-exposed preterm infants n = 10 controls matched to healthy-preterm sample |

EEG sleep study at 30–40 weeks’ postconceptional age (i.e., age 1–3 days for controls; age 4–6 weeks for preterm) | Alcohol-exposed preterm infants demonstrated increased EEG power in quiet, indeterminate, and REM sleep, compared to controls. Healthy preterm infants did not differ from their control group. Effect of alcohol on EEG is not related to preterm birth or acute alcohol withdrawal. |

| Ipsiroglu et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional | N = 27 parents and children with FASD, 2–15 years old | Qualitative interviews, comprehensive clinical sleep assessment | All parents identified sleep problems, but these were underdiagnosed by physicians. Symptoms were often identified by physicians, but attributed to ADHD. |

| Mulder et al. (1998) | Cross-sectional | N = 28 near-term pregnant women and their fetuses | Ultrasound to obtain fetal heart rate, body, eye, and breathing movements | Acute low-dose alcohol intake immediately reduced fetal eye movements and breathing activity, and disturbed behavioral state organization (especially REM). |

| Pesonen et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional, epidemiologic cohort study |

N = 289 children, 8 years old n = 51 with >0 maternal alcohol consumption |

Actigraphy, Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children | PAE was associated with decreased sleep efficiency. Alcohol-exposed children had significantly greater odds of short sleep duration (2.9-fold) and low sleep efficiency (3.6-fold). |

| Rosett et al. (1979) | Cross-sectional |

N = 31 three-day-old infants: n = 14 heavy-drinking mothers n = 8 heavy-drinking mothers who abstained/drank moderately during 3rd trimester n = 9 abstinent mothers |

24-hour bassinet sleep monitor | No group differences in proportion of sleep stages; infants with heavy-drinking mothers slept less, had poorer sleep quality, more restlessness, and more frequent arousals during NREM sleep. |

| Sander et al. (1977) | Cross-sectional |

N = 12 three-day-old infants: n = 4 heavy-drinking mothers n = 4 heavy-drinking mothers who abstained/drank moderately during 3rd trimester n = 4 abstinent mothers |

24-hour bassinet sleep monitor; standard sleep polygraphy | Abnormal patterning of sleep stages in alcohol-exposed infants; difficulty reaching NREM sleep, more arousals during REM/NREM sleep, fewer intact sleep cycles. |

| Scher et al. (1988) | Cross-sectional |

N = 55 alcohol- or marijuana-exposed infants n = 18 alcohol-exposed during 1st trimester n = 13 non-alcohol exposed during 1st trimester |

EEG sleep study at 24–36 hours old | First trimester alcohol use predicted increased number of arousals per minute and % indeterminate sleep; decreased % low voltage active/REM sleep and trace alternant quiet sleep. Infants of alcohol-users had increased number of arousals per minute, number of spontaneous arousals, and duration of spontaneous arousals. EEG sleep disturbance was in the absence of FAS or clinical withdrawal. |

| Scher et al. (2000) | Prospective longitudinal |

N = 71 infants n = 37 cocaine-exposed n = 34 non-cocaine-exposed |

EEG sleep study at 24–36 hours old, and at 1 year old | Alcohol use during pregnancy predicted greater levels of wakefulness at birth and increased spectral power at higher EEG frequencies. Alcohol-exposed infants took longer to complete a sleep cycle. |

| Troese et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | N = 13 mothers and their 6–8 week old infants | Naps recorded via EEG, videography, actigraphy | High PAE group had increased sleep fragmentation and decreased REM sleep; suppressed spontaneous movements during sleep. |

| Wengel et al. (2011) | Cross-sectional |

N = 31 children, 3–6 years old n = 19 with FASD n = 12 non-exposed controls |

Actigraphy, sleep log, Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), Sensory Profile | FASD group took longer to fall asleep, but no differences on other actigraphy variables. Parents reported more sleep problems in FASD group (e.g., increased bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, night awakenings, parasomnias, and shorter sleep duration). |

Behavioral state organization and sleep pattern

PAE affects development of numerous neuronal networks, consequently altering state regulation and brain activity (Scher et al., 2000). Mulder et al. (1998) examined the effects of acute maternal alcohol intake on fetal behavioral states between weeks 37 and 40 of gestation using ultrasound. As pregnant mothers consumed two glasses of wine, ultrasound scanners measured changes in fetal heart rate, eye movements, breathing movements, and body movements. Results showed that acute intoxication caused immediate disruption of behavioral state organization in the fetus, especially active/REM sleep, and also suppressed fetal breathing and eye movements. Given the importance of REM sleep for normal brain development, the immediate alteration to fetal REM sleep during alcohol intake may contribute to later CNS dysfunction in infants with PAE (Mulder et al., 1998).

Sleep disruption during infancy was among the first problems investigated in newborns with PAE, shortly after the fetal alcohol syndrome was characterized by Jones and Smith (1975). In a small (n = 12) study examining infants on the third day of life, Sander et al. (1977) found that the patterning of sleep stages was abnormal, especially in infants with heavy PAE. These infants had difficulty reaching a NREM episode without waking first, exhibited more arousals during both REM and NREM sleep, and had fewer intact REM/NREM cycles, compared to controls. Havlicek et al. (1977) also found that infants born to alcoholic mothers had difficulty reaching quiet/NREM sleep, and awoke more easily. As a follow-up to Sander et al.’s study, Rosett et al. (1979) monitored sleep and wake states for 24 hours in a sample of three-day-old infants, and found that infants with heavy PAE had more frequent arousals, particularly NREM sleep interrupted by transitional sleep. An increase in the number of transitional sleep periods (i.e., when features of the sleep stage are inconsistent with the definition of either REM or NREM sleep), increased time awake, and increased time to complete a full sleep cycle have also been more recently reported (Scher et al., 2000). Furthermore, the greater the quantity of alcohol consumed during the third trimester, the less time the infant spent sleeping (Rosett et al., 1979).

Other studies suggest that sleep fragmentation (i.e., sleep disruption due to arousals or awakening), as opposed to sleep-wake state organization (i.e., the proportion and sequencing of sleep stages), may be a better indicator of prenatal substance exposure. Hanft et al. (2006) demonstrated that infants of substance-abusing mothers, compared to non-exposed controls, spent less total time asleep, and their longest sleep period was significantly shorter. However, the groups did not differ in the proportion of other sleep-wake variables (i.e., active sleep %, quiet sleep %, awake %, number of nighttime awakenings), suggesting that in utero exposure to substances may not always affect overarching organization and proportion of sleep-wake states. Although it is unclear whether these effects were specific to PAE, the results from this study are consistent with the findings from Rosett et al. (1979) and Sander et al. (1977), in that infants prenatally exposed to alcohol sleep less overall and experience more arousals during sleep than non-exposed infants.

Abnormal EEG

Studies of EEG in newborns and infants prenatally exposed to alcohol have also uncovered abnormalities in brain activity during sleep. Many of these studies have examined the EEG power spectrum: a measure derived from brain waves via Fourier transform that represents the distribution of frequencies that compose the EEG signal. Across studies, infants prenatally exposed to alcohol demonstrate increased spectral power of the EEG during sleep, which is exhibited at alpha, beta, delta, and theta frequencies, and may appear visually as a higher amplitude wave-form (i.e., hypersynchrony; Scher et al., 2000; Chernick et al., 1983; Havlicek et al., 1977).

Havlicek et al. (1977) first described the power-spectrum characteristics of quiet/NREM, active/REM, and indeterminate sleep in infants born to alcoholic mothers. EEG power was increased in most frequency bands by an average of 150 to 200%, compared to controls, in all three stages of sleep, with the greatest increase in active sleep. Furthermore, alcohol-exposed infants did not demonstrate any difference in power between REM and NREM sleep for any frequency band, except theta. However, controls demonstrated significantly lower power in all frequency bands during REM sleep, compared to NREM sleep. Havlicek et al. (1975) suggest the lack of a NREM-REM power spectrum difference is an indicator of delayed EEG maturation, as this finding was also observed in infants who were born prematurely. Ioffe and Chernick (1988) also demonstrated that alcohol exposure affects the maturation of neonatal EEG, and elevated power is observed during infant REM and NREM sleep as early as 30 weeks’ gestational age, up through 40 weeks’ gestational age. These EEG changes persist postnatally up to six weeks of age, providing evidence that this abnormality is not due to acute alcohol withdrawal (Ioffe et al., 1984). Furthermore, increased EEG power appears to be a specific effect of alcohol, and is not associated with maternal smoking (Chernick et al., 1983).

Increased power of the EEG is correlated with problems in motor and mental development later in life (Ioffe and Chernick, 1988; Ioffe and Chernick, 1990). Such EEG-sleep disturbances are also present in infants with PAE who do not meet criteria for FAS (Scher et al., 1988), and further support findings of altered neonatal state regulation in the FASD population. One caveat is that skull thickness demonstrates a weak, but significant, inverse relationship with EEG topography (Hagemann et al., 2008). Given that PAE affects fetal bone development, and that animal models of FASD have found reduced bone volume in the skull (Shen et al., 2013; Birch et al., 2015), it is possible that such increased EEG power could be partially related to decreased skull thickness. However, as mentioned above, Havlicek et al. (1977) found no NREM-REM power spectrum difference in the alcohol-exposed group, whereas controls exhibited significantly lower power in REM compared to NREM. If the observed increase in EEG power were solely related to reduced skull thickness in the alcohol-exposed infants, one would expect the NREM-REM power difference to persist in the alcohol-exposed group. Thus, the observed findings are likely indicative of altered brain activity during sleep in the alcohol-exposed group.

Sleep movement

PAE affects sleep movements both in utero and in infancy. Fetal breathing movements during sleep are suppressed by acute alcohol intake (Mulder et al., 1998) and major body movements, indicative of restlessness, are more frequent during sleep in prenatally exposed newborns (Rosett et al., 1979; Scher et al., 1996; Scher et al., 1988). On the other hand, six- to eight-week-old infants with PAE exhibited suppressed sleep-related spontaneous motor movements (Troese et al., 2008). Sleep-related spontaneous motor movements are important to maintaining cardio-respiratory tone during sleep; such movements are independent of major body movements, which are related to arousals and restlessness. Furthermore, the suppression of sleep-related spontaneous motor movements has been associated with chronic sleep deprivation and increases in obstructive sleep apnea (Troese et al., 2008; Franco et al., 2000).

Summary

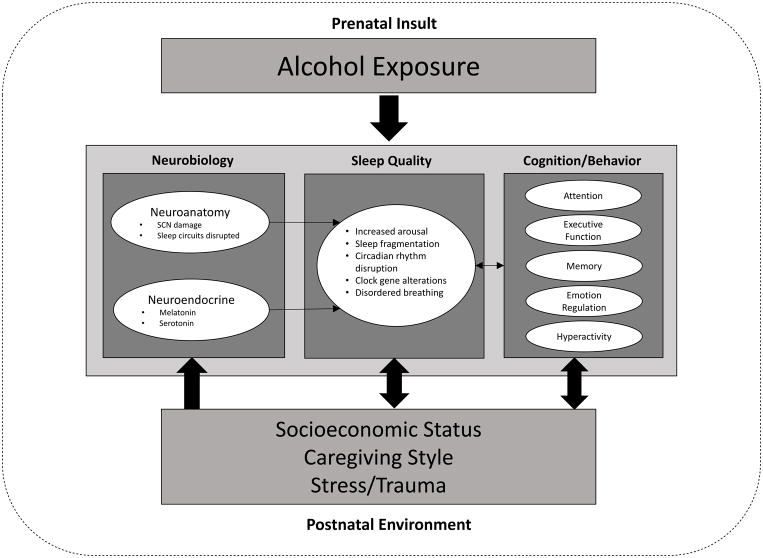

The effects of alcohol exposure are immediately observable in the developing fetus as a disruption of behavioral state organization and reduced eye and breathing movements. PAE is associated with poorer sleep quality and sleep fragmentation, and exposed infants demonstrate symptoms of sleep debt, such as irritability and decreased alertness (Scher et al., 1988; Troese et al., 2008). Changes in EEG are evident at birth, and while it is possible that these effects are due to alcohol withdrawal, such alterations persist at four to six weeks old (Ioffe et al., 1984). Sleep fragmentation has also been reported at six to eight weeks of age (Troese et al., 2008). These findings suggest that the EEG and sleep abnormalities observed in alcohol-exposed infants are not a primary consequence of acute withdrawal from alcohol. Indeed, Scher et al. (1988) also noted that EEG-sleep disturbances were present in infants with moderate alcohol exposure, none of whom displayed any clinical withdrawal states. However, a major limitation to many of these studies is that longitudinal data during the first years of life have not been collected to determine how sleep changes during early development in infants/toddlers with FASD. It remains unknown how persistent sleep disturbance is in the context of alcohol-exposed brain maturation and development; nonetheless, in non-exposed preterm infants, similar disruptions in sleep state organization and motor activity are reflective of altered brain development (Scher et al., 1996). The findings from alcohol-exposed infants offer important insight regarding potential etiologies of the sleep problems observed later in childhood. See Figure 1 for a proposed model of the effects of PAE on sleep disturbance.

Figure 1.

A proposed model of different factors that interact to affect sleep quality in the context of prenatal alcohol exposure. This model includes neurobehavioral functioning as a potential outcome to be examined in relation to sleep quality. Environmental factors that may affect both sleep quality and neurobehavioral functioning should also be considered. The relationships among these factors are complex, and many are likely to be bidirectional. SCN = suprachiasmatic nucleus

Sleep in Children with PAE

Sleep is a complex neurologic function; thus, it is not surprising that sleep difficulties are a prevalent problem in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, including children with FASD (Jan et al., 2008). Consequently, caregivers of children with FASD often report that their child has problems with sleep, and sleep abnormalities are one of the most common comorbidities with FASD, along with intellectual disability and ADHD (Wengel et al., 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2010). These sleep disturbances are considered similar to the sleep difficulties experienced by children with other forms of cognitive loss and brain disturbance, rather than being specific to a particular diagnosis (Jan et al., 2010). However, there are limited data characterizing sleep patterns in this population and the prevalence of sleep disorders in FASD is currently unknown.

In an effort to help stimulate research in this area, Jan et al. (2010) presented anecdotal evidence from their clinical experience with children with FASD and sleep disturbance. They reported that the sleep disturbance described by caregivers of children with FASD tends to include difficulties falling asleep, frequent awakenings during the night, and early morning awakenings. These symptoms mirror the first diagnostic criterion of insomnia disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), but could also be the result of abnormal melatonin production/secretion, reflecting disturbance of the sleep-wake centers in the SCN and hypothalamus. Two studies utilizing a parent-report sleep screener, the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ; Owens et al., 2000b), found that three- to twelve-year-old children with FASD had significantly more problems with sleep onset latency, sleep duration, and night awakenings, compared to controls. The FASD group also had greater bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, and prevalence of parasomnias (i.e., bedwetting, sleep talking, and night terrors; Chen et al., 2012; Wengel et al., 2011).

Actigraphy data in this population are limited. In a study conducted by Wengel et al. (2011), three to six-year-olds with PAE exhibited significantly longer sleep onset latency, though there were no differences from controls in total activity, sleep efficiency, sleep percent, sleep time, or number of wake bouts. However, the small sample size (n = 31; 19 alcohol-exposed) rendered this an underpowered study, and potential differences may not have been detectable. In contrast, a much larger actigraphy study (n = 289; 51 alcohol-exposed) in eight-year-olds reported that PAE was associated with a significant increase in the odds of having shorter sleep duration and lower sleep efficiency (Pesonen et al., 2009).

Only two studies have examined sleep in children with FASD using a multidimensional assessment, consisting of polysomnography in conjunction with caregiver questionnaires. Chen et al. (2012) sought to establish a profile of sleep problems in children with PAE. Their sample consisted of 33 children aged 4 to 12 years with a diagnosis on the fetal alcohol spectrum whose sleep habits were assessed using the CSHQ (Owens et al., 2000b); a small subsample were referred to participate in polysomnography. Caregivers of children with PAE reported that their child had a significantly greater number of sleep problems, and 85% of children in the FASD group scored above the CSHQ clinical cutoff for sleep dysfunction, compared to only 30% of the community sample comparison group. Children with FASD also slept an hour less each night, on average. Only five children in the sample completed polysomnography. These data were compared to published normative data from typically developing children, and there were no statistically significant group differences. However, the FASD group did demonstrate an elevated total arousal index, indicative of fragmented sleep. All five children in this sample also had mild sleep disordered breathing; the median apnea hypopnea index (AHI), used to indicate severity of sleep apnea, was more than two standard deviations above the reported mean AHI in community sample data. Importantly, craniofacial abnormalities observed in some individuals with FASD can include narrowed upper airways, which may contribute to increased likelihood of disordered breathing during sleep (Usowicz et al., 1986). Additionally, animals with PAE demonstrate a blunted respiratory response to low oxygen (Dubois et al., 2008). Either of these abnormalities have the potential to contribute to sleep disordered breathing, and consequently, increase the frequency of cortical arousal during sleep (Chen et al., 2012).

Goril et al. (2016) also collected polysomnography data in addition to melatonin levels from a larger sample of children and adolescents (6 to 18 years old) with PAE (n = 36). Compared to normative data, children with FASD demonstrated lower than normal sleep efficiency (i.e., ratio of total amount of time spent asleep to the total amount of time spent in bed) and increased sleep fragmentation. Additionally, 58% of children met criteria for at least one sleep disorder, as defined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3; American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014). The most common diagnoses were parasomnias (19.5% NREM parasomnia, 5.6% REM parasomnia, 2.8% both NREM and REM parasomnia) and insomnia (16.7%), though others included sleep apnea (5.6%) and nocturnal enuresis (2.8%). In addition, the majority of participants (79%) had an abnormal melatonin profile that was either delayed (17%), advanced (8%), or abnormal but not clearly classifiable (54%). Abnormal melatonin secretion profiles are consistent with the disruption in sleep patterns observed clinically (Jan et al., 2010). Children with bilateral brain damage or other forms of severe cognitive loss frequently experience symptoms associated with circadian rhythm sleep disorders due to abnormal melatonin production and/or secretion, which may be a result of disrupted input from the cerebral cortex to the SCN (Jan et al., 2010; Saper et al., 2005). Considering the widespread brain damage caused by PAE and the complexity of sleep as a neurological function, it is not surprising that children with FASD experience greater rates of sleep problems related to chronic altered circadian rhythm and melatonin production.

Neurocognitive and Behavioral Correlates of Sleep Disruption

In adults, sleep deprivation is associated with impaired cognitive functioning, particularly on complex tasks that involve the prefrontal cortex, such as higher levels of executive function, cognitive processing, language skills, attention, and working memory (Sadeh et al., 2002). In pediatric populations, sleep difficulties are closely related to poor daytime functioning (Kheirandish and Gozal, 2006) and may negatively affect emotion regulation, interpersonal relationships, academic performance, and cognitive skills (Markovich et al., 2014; Vriend et al., 2013). Impaired sleep in children is associated with behavioral problems, including hyperactivity, aggressiveness, inattentiveness, impulsivity, depression, and other mood disorders (Jan et al., 2010; Owens, 2009; Stepanski, 2002). Pediatric sleep disturbance is related to deficits in verbal fluency, abstract and deductive reasoning, planning, flexibility, inhibition, problem solving, attention, vigilance, memory formation, and motor skills (Maski and Kothare, 2013; Kheirandish and Gozal, 2006; Jan et al., 2010). Moreover, evidence suggests that the effects of sleep disruption may be more severe in children with developmental disabilities (Ingrassia and Turk, 2005): disturbed sleep is associated with increased behavioral symptoms, particularly hyperactivity, disorganization, and oppositionality (Wengel et al., 2011; Jan et al., 2008).

The extent to which sleep disturbance moderates or mediates other behavioral outcomes in individuals with FASD is currently unknown. Sleep fragmentation, alone, may influence neurobehavioral performance. For example, typically developing children with fragmented sleep perform worse on neurobehavioral tasks related to higher executive control, such as sustained attention and behavioral inhibition; however, they are not affected on simple tasks of motor speed, working memory, or reaction time (Sadeh et al., 2002). Similarly, obstructive sleep apnea (which also causes sleep fragmentation) may contribute to daytime sleepiness (Carroll et al., 1995) and neurobehavioral deficits in attention, memory, concentration, and academic achievement (Gozal, 1998). Children with obstructive sleep apnea demonstrate significantly lower IQ scores, compared to controls (Blunden et al., 2000), and verbal abilities and overall language scores are also adversely affected (Kheirandish and Gozal, 2006). Importantly, Owens et al. (2000a) found that children with obstructive sleep apnea demonstrated modest impairments in executive functioning, attention, and motor skills. However, after treatment of obstructive sleep apnea, children show significant improvements in daytime sleepiness, symptoms of ADHD, internalizing behaviors, and quality of life (Marcus et al., 2012). These data suggest that reducing sleep apnea improves functioning on a number of behavioral domains.

Unfortunately, the conclusions drawn from the majority of these studies are limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data, and the complex relationship between sleep disruption and neurobehavioral functioning. In light of the challenges of appropriate experimental design and complexities in data interpretation, no studies, to our knowledge, have examined the extent to which sleep disturbance is related to neurobehavioral outcomes in children with an FASD. One study of developmental ethanol exposure in mice found that the exposed mice demonstrated severe sleep fragmentation and reduced slow-wave sleep, which were significantly correlated with memory impairment (Wilson et al., 2016). Children with FASD demonstrate particular deficits in executive functioning (i.e., planning, response inhibition, abstract thinking, cognitive flexibility), attention, language development, processing speed, learning and memory. Based on the findings from adult and pediatric populations, we hypothesize that sleep disturbance would be associated with greater impairment in attention, memory processes, and executive function in this population. However, it is possible that PAE negatively affects both sleep quality and neurobehavioral functioning separately, and while these two outcomes may demonstrate a relationship, determination of causality must be examined in the context of a longitudinal study with a sleep disorder treatment component. Nonetheless, considering the wide range of cognitive deficits and behavioral problems present in populations with FASD, the possibility remains that cognitive and behavioral consequences of PAE are exacerbated by sleep deficits (Volgin and Kubin, 2012). Thus, further examination of these relationships and subsequent exploration of sleep disturbance as a potential moderator or mediator of neurobehavioral outcomes is crucial.

Postnatal Environmental Factors

In addition to the insult that alcohol exerts on the fetal brain, postnatal environmental factors also contribute to the cognitive and behavioral outcomes of children with PAE. These children are often affected by adverse environmental circumstances, such as living with a parent who abuses alcohol, neglect, physical or emotional abuse, removal from the home, transient or long term foster care placement, and/or being raised by an adoptive family (Streissguth et al., 2004). Stressors in the home environment may expose the infant to excessive arousal, compromising development of self-regulation skills (Vig et al., 2005). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder can also include sleep disturbance, such as nightmares or night terrors. Thus, inability to establish a regular pattern of sleep and disorders of regulation, which are common in children in foster care, might also be expected in many alcohol-exposed children.

In epidemiologic studies of FASD, mothers of alcohol-exposed children consistently have lower education, higher rates of unemployment, and lower overall SES, compared to controls (May and Gossage, 2011). Low socioeconomic status (SES) has also been associated with greater sleep problems (Buckhalt et al., 2007). This may be due to a multitude of factors, including chronic stress due to lack of resources, overcrowded living spaces, and inadequate temperature control in the bedroom (Williams, 1999). Poor health outcomes, such as asthma and obesity, are more common due to lack of access to adequate healthcare in lower SES groups. Both these conditions are risk factors for sleep disordered breathing. Thus, a child with PAE who comes from a low SES background may be at greater risk of having poor sleep quality.

Attachment style, which is shaped early in infancy via interactions with the caregiver, develops at a similar time to sleep regulation, and there is evidence to suggest that these two constructs exhibit a bidirectional relationship (Adams et al., 2014). Secure attachment style, which is generally thought to be fostered by consistent, sensitive, and responsive mothering, is associated with better sleep quality; insecure attachment is more likely to occur in children whose caregivers engage in neglectful or abusive parenting, and is associated with poorer sleep (Adams et al., 2014). Considering the environmental risk factors associated with PAE, it is not surprising that children with PAE demonstrate higher levels of insecure attachment (O’Connor et al., 2002). Furthermore, Adams et al. (2014) posit that caregiving style plays a role in the development of sleep patterns, which is regulated by complex interactions between circadian, homeostatic, and environmental factors (Davis et al., 2004). Thus, inconsistent caregiving style and subsequent attachment behaviors also may be a potential source of sleep disturbance and behavioral dysregulation in children with PAE. It is likely that environmental factors, such as unpredictable caregiving style, limited exposure to behavioral routines early in life, low SES, and high levels of anxiety (Vig et al., 2005; Buckhalt et al., 2007) interact with neurobiological vulnerability to produce the sleep disturbances observed in this population.

Interventions

When a child with FASD is sleep deprived, intervention services may be less effective or ineffective (Jan et al., 2010). Yet, sleep problems in individuals with FASD are often not appropriately identified or treated. Ipsiroglu et al. (2013) used qualitative interviews and comprehensive clinical sleep assessments to investigate reasons why sleep problems often go undiagnosed and untreated in children with FASD. Children ages 2 to 15 (n = 27) and their parents participated in comprehensive clinical sleep assessments that addressed the importance of sleep and how sleep problems affected the child’s well-being and the entire family’s quality of life. However, healthcare providers often missed relevant information about these sleep problems, or attributed the problems to other causes, preventing proper identification and, therefore, treatment of sleep disorders. Additionally, in the majority of children assessed for the study (74%), symptoms were treated with prescription sleep medication prior to being evaluated with a relevant sleep disorder screening or diagnostic questionnaire. FASD standard-of-care guidelines do not address how to assess for sleep disorders, nor do the usual diagnostic measures encompass screening for sleep problems, resulting in a lack of information in this important area and a tendency to defer to pharmaceutical treatment (Ipsiroglu et al., 2013).

The limited research findings on sleep disturbance in children with FASD indicate that future interventions should target fragmented sleep, decreased slow-wave sleep, and circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Given the high rate of ADHD in alcohol-exposed children, we may also obtain important insight regarding the best avenues for intervention by examining assessment and treatment of similar sleep problems in children with ADHD. It is estimated that up to 50% of children with ADHD have sleep disturbance (Corkum et al., 1998); difficulty initiating sleep (i.e., bedtime resistance, delayed sleep onset) and maintaining sleep (i.e., sleep fragmentation) are especially problematic, both of which mirror the findings from the limited literature on sleep in children with FASD. While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for sleep disturbance in ADHD are still limited, results are promising for the efficacy of behavioral sleep interventions (e.g., bedtime routines, sleep environment modification, behavior reinforcement strategies) in improving sleep quality (Corkum et al., 2016; Keshavarzi et al., 2014; Hiscock et al., 2015). Importantly, these interventions also improved behavior, psychosocial health, and quality of life and had a lasting positive impact on sleep at six month follow-up.

Sleep hygiene is a behavioral technique that involves sleep scheduling, improved sleep environment, and sleep-promoting practices. In addition to demonstrating efficacy as an intervention in ADHD, sleep hygiene has also been shown to be an effective intervention in children with autism spectrum disorders who experience sleep problems (Weiskop et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2014). Jan et al. (2010) emphasize that it is essential for sleep hygiene practices to be tailored to the individual child according to their cognitive and health needs. Even still, this type of intervention may be unsuccessful due to a child’s impaired understanding of environmental cues used to promote sleep. Jan et al. suggest minimizing stimuli at night; this can be accomplished with earplugs or white noise machines, dimming lights and removing clutter, and removing tags from pajamas and blankets to avoid sensory distractors. Sleep scheduling involves enforcing rules, structure, routine, and consistency, particularly for bedtime and wake-up time, even on weekends. Preparing for sleep is also important, and calming behaviors and wind-down rituals can aid in promoting sleep, while physical behaviors, screen time, and caffeine should be avoided to minimize alertness and delayed sleep onset (Jan et al., 2010).

Melatonin therapy, in conjunction with sleep hygiene techniques, could also help to establish sleep scheduling (Jan et al., 2010). Melatonin may decrease sleep-onset latency and increase total sleep time, but its effectiveness depends on the type of sleep disturbance, environmental factors, and other medical conditions (Cohen et al., 2014). In clinical trials of melatonin treatment in children with autism spectrum disorders, melatonin therapy was associated with improved sleep outcomes (e.g., sleep onset latency, sleep duration), as well as improvement in internalizing problems and behavioral problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, withdrawal, aggression, social), stereotyped and compulsive behaviors, and parenting stress (Malow et al., 2012; Giannotti et al., 2006; Garstang and Wallis, 2006; Wasdell et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2011; Paavonen et al., 2003; Tordjman et al., 2013). Melatonin has also been shown to reduce sleep onset difficulties in children with ADHD (Weiss et al., 2006; Van der Heijden et al., 2007; Tjon Pian Gi et al., 2003). However, melatonin is not a regulated drug in the United States. Rather, melatonin is classified as a dietary supplement; therefore, its use has not been evaluated for safety in children, nor is it subject to the same standards of purity as pharmaceuticals. Melatonin has the potential to interact with enzymes important for metabolizing a variety of prescription drugs (e.g., SSRIs), and animal studies have demonstrated that melatonin modulates the rhythms of the reproductive, cardiovascular, immune, and metabolic systems (Kennaway, 2015; Dubocovich et al., 2010; Dubocovich and Markowska, 2005). Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence that melatonin is safe for long-term use, particularly with pediatric populations. Alternatively, light therapy can be used to advance or delay the sleep phase, and is another intervention that has demonstrated effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders who have circadian sleep disorders (Cohen et al., 2014). Considering the associations of FASD behaviors with sleep disturbance, there is a great need for future research studies that examine the most effective interventions targeting sleep problems in children with FASD.

Conclusion

Although there have been a limited number of studies examining sleep disturbance in individuals with PAE, sleep problems may be a pervasive issue that impact the quality of life of affected children and their caregivers. The effects of alcohol on fetal sleep-wake states and eye movements are immediately apparent, and for infants with PAE, these abnormalities persist in the form of sleep fragmentation, decreased REM sleep, and reduced total sleep time. Furthermore, alcohol-exposed infants demonstrate symptoms of sleep deprivation, particularly decreased alertness and increased irritability. In childhood, PAE is associated with a greater likelihood of having shorter sleep duration and poor sleep efficiency, as well as sleep fragmentation, mild sleep disordered breathing, and melatonin secretion abnormalities. Additionally, environmental stressors that often accompany PAE, such as inconsistent caregiving, child abuse, and removal from the home, are related to increased sleep problems. Sleep disturbance may be one of the most common comorbidities with PAE, though healthcare providers often fail to properly assess for sleep disorders. Consequently, sleep disorders frequently go undiagnosed and untreated, which may affect individuals’ well-being in a variety of domains.

The mechanisms underlying the effects of PAE on sleep have not been widely examined. Animal studies have shown that the circadian function of neurons in the hypothalamus and clock mechanism of the SCN are significantly altered by PAE (Chen et al., 2006; Farnell et al., 2008), lending support to the hypothesis that neuronal damage due to alcohol exposure in utero can lead to circadian dysregulation and sleep disturbance (Earnest et al., 2001). However, one of the challenges to understanding the relationship between PAE and sleep disturbance in humans is that while sleep problems may be a direct result of alcohol-induced neuropathology, they may also be due to other pre-existing health problems, psychopathology, or environmental factors. Nevertheless, given that problems with sleep can further exacerbate these conditions, screening and treatment are warranted regardless of whether the primary cause is due to PAE.

Future Directions

Given the impact of sleep disturbance on neurobehavioral functioning and quality of life in typically developing children and children with other neurodevelopmental disorders, this is a significant, clinically relevant issue that is not well understood in the FASD population. The studies reviewed herein attest to the need for formal sleep assessment at the level of primary care for individuals with PAE. Further characterizing the sleep profile of children with PAE using comprehensive methods of sleep measurement (e.g., polysomnography, actigraphy, questionnaires) in larger samples will aid in establishing standard-of-care guidelines for clinicians and in developing the most effective methods of intervention. This information would help healthcare providers make better informed diagnoses, and would be particularly useful in determining the most appropriate medications for an individual. Furthermore, elucidating the relationship between sleep disturbance and neurobehavioral functioning may reveal alternate avenues for managing behavior problems, ameliorating emotional dysregulation, and improving cognitive function in individuals with PAE.

Many of the sleep studies conducted to date are limited by small sample size and lack of an appropriate control group. Future studies should aim to include age- and sex-matched typically developing controls in order to further clarify the relationship between PAE and sleep. Additionally, studies examining a non-exposed contrast group, such as children with ADHD or sleep disorders, would be helpful in determining the specificity of sleep problems and their potential relationship to neurobehavioral outcomes. Such information could aid in differential diagnosis and earlier identification of affected children. Ultimately, increased understanding of the effects of PAE on sleep quality should be used to inform the development of novel interventions aimed at improving the quality of life of children affected by PAE.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grants R01AA012446, R21AA025425, and T32AA013525

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams GC, Stoops MA, Skomro RP. Sleep tight: Exploring the relationship between sleep and attachment style across the life span. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GC, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ. Developmental alcohol exposure disrupts circadian regulation of BDNF in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Illinois: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; Virginia: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders T, Emde R, Parmelee A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Criteria for Scoring of States of Sleep and Wakefulness in Newborn Infants. UCLA Brain Information Service/BRI Publications Office, NINDS Neurological Information Network; California: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Arjona A, Boyadjieva N, Kuhn P, Sarkar DK. Fetal ethanol exposure disrupts the daily rhythms of splenic granzyme B, IFN-gamma, and NK cell cytotoxicity in adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1039–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus J, Hoeckesfeld R, Born J, Hohagen F, Junghanns K. Immediate as well as delayed post learning sleep but not wakefulness enhances declarative memory consolidation in children. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat M, Doyon J, Debas K, Vandewalle G, Morin A, Poirier G, Martin N, Lafortune M, Karni A, Ungerleider LG, Benali H, Carrier J. Fast and slow spindle involvement in the consolidation of a new motor sequence. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard AR, Nolan PM. When clocks go bad: Neurobehavioural consequences of disrupted circadian timing. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry RB, Gamaldo CE, Harding SM, Brooks R, Lloyd RM, Vaughn BV, Marcus CL. AASM scoring manual version 2.2 updates: New chapters for scoring infant sleep staging and home sleep apnea testing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1253–1254. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SM, Lenox MW, Kornegay JN, Shen L, Ai H, Ren X, Goodlett CR, Cudd TA, Washburn SE. Computed tomography assessment of peripubertal craniofacial morphology in a sheep model of binge alcohol drinking in the first trimester. Alcohol. 2015;49:675–689. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg MS. Beyond dreams: Do sleep-related movements contribute to brain development? Front Neurol. 2010;1:140. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2010.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunden S, Lushington K, Kennedy D, Martin J, Dawson D. Behavior and neurocognitive performance in children aged 5–10 years who snore compared to controls. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000;22:554–568. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200010)22:5;1-9;FT554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K, Parikh S, Bassila M. Growth failure and sleep disordered breathing: A review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M, Keller P. Children’s sleep and cognitive functioning: Race and socioeconomic status as moderators of effects. Child Dev. 2007;78:213–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajochen C, Krauchi K, Wirz-Justice A. Role of melatonin in the regulation of human circadian rhythms and sleep. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:432–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JL, McColley SA, Marcus CL, Curtis S, Loughlin GM. Inability of clinical history to distinguish primary snoring from obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Chest. 1995;108:610–618. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Kuhn P, Advis JP, Sarkar DK. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters the expression of period genes governing the circadian function of beta-endorphin neurons in the hypothalamus. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1026–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, Olson HC, Picciano JF, Starr JR, Owens J. Sleep problems in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:421–429. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernick V, Childiaeva R, Ioffe S. Effects of maternal alcohol intake and smoking on neonatal electroencephalogram and anthropometric measurements. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:41–47. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90924-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, Daniels J, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, Kurzius-Spencer M, Lee LC, Pettygrove S, Robinson C, Schulz E, Wells C, Wingate MS, Zahorodny W, Yeargin-Allsopp M Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudley AE, Conry J, Cook JL, Loock C, Rosales T, LeBlanc N Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMAJ. 2005;172:S1–S21. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Conduit R, Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SM, Cornish KM. The relationship between sleep and behavior in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A review. J Neurodev Disord. 2014;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkum P, Lingley-Pottie P, Davidson F, McGrath P, Chambers CT, Mullane J, Laredo S, Woodford K, Weiss SK. Better nights/better days - Distance intervention for insomnia in school-aged children with/without ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41:701–713. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkum P, Tannock R, Moldofsky H. Sleep disturbances in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:637–646. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. The impact of inadequate sleep on children’s daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(96)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalen K, Bruaroy S, Wentzel-Larsen T, Laegreid LM. Cognitive functioning in children prenatally exposed to alcohol and psychotropic drugs. Neuropediatrics. 2009;40:162–167. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danel T, Cottencin O, Tisserand L, Touitou Y. Inversion of melatonin circadian rhythm in chronic alcoholic patients during withdrawal: Preliminary study on seven patients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:42–45. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenne D, Adrien J. Suppression of PGO waves in the kitten: Anatomical effects on the lateral geniculate nucleus. Neurosci Lett. 1984;45:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenne D, Adrien J. Lesion of the ponto-geniculo-occipital pathways in kittens. I. Effects on sleep and on unitary discharge of the lateral geniculate nucleus. Brain Res. 1987;409:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenne D, Fregnac Y, Imbert M, Adrien J. Lesion of the PGO pathways in the kitten. II. Impairment of physiological and morphological maturation of the lateral geniculate nucleus. Brain Res. 1989;485:267–277. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KF, Parker KP, Montgomery GL. Sleep in infants and young children: Part two: Common sleep problems. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18:130–137. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5245(03)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campo M, Jones KL. A review of the physical features of the fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaney M, Graham D, Greeley J. Circadian variation of the acute and delayed response to alcohol: Investigation of core body temperature variations in humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:881–887. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald KA, Eastman E, Howells FM, Adnams C, Riley EP, Woods RP, Narr KL, Stein DJ. Neuroimaging effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the developing human brain: A magnetic resonance imaging review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2015;27:251–269. doi: 10.1017/neu.2015.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubocovich ML, Delagrange P, Krause DN, Sugden D, Cardinali DP, Olcese J. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXV. Nomenclature, classification, and pharmacology of g protein-coupled melatonin receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:343–380. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubocovich ML, Markowska M. Functional MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors in mammals. Endocrine. 2005;27:101–110. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois C, Houchi H, Naassila M, Daoust M, Pierrefiche O. Blunted response to low oxygen of rat respiratory network after perinatal ethanol exposure: Involvement of inhibitory control. J Physiol. 2008;586:1414–1427. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnest DJ, Chen WJ, West JR. Developmental alcohol and circadian clock function. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:136–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnell YZ, Allen GC, Nahm SS, Neuendorff N, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ. Neonatal alcohol exposure differentially alters clock gene oscillations within the suprachiasmatic nucleus, cerebellum, and liver of adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnell YZ, West JR, Chen WJ, Allen GC, Earnest DJ. Developmental alcohol exposure alters light-induced phase shifts of the circadian activity rhythm in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1020–1027. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130807.21020.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg I. Changes in sleep cycle patterns with age. J Psychiatr Res. 1974;10:283–306. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(74)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficca G, Lombardo P, Rossi L, Salzarulo P. Morning recall of verbal material depends on prior sleep organization. Behav Brain Res. 2000;112:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K, Wong RO. A comparison of experience-dependent plasticity in the visual and somatosensory systems. Neuron. 2005;48:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco P, Chabanski S, Szliwowski H, Dramaix M, Kahn A. Influence of maternal smoking on autonomic nervous system in healthy infants. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:215–220. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudigman KA, Thoman EB. Infant sleep during the first postnatal day: An opportunity for assessment of vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1993;92:373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer SL, McGee CL, Matt GE, Riley EP, Mattson SN. Evaluation of psychopathological conditions in children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e733–741. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garstang J, Wallis M. Randomized controlled trial of melatonin for children with autistic spectrum disorders and sleep problems. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32:585–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertner S, Greenbaum CW, Sadeh A, Dolfin Z, Sirota L, Ben-Nun Y. Sleep-wake patterns in preterm infants and 6 month’s home environment: Implications for early cognitive development. Early Hum Dev. 2002;68:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(02)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Cerquiglini A, Bernabei P. An open-label study of controlled-release melatonin in treatment of sleep disorders in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:741–752. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D. Sleep-disordered breathing and school performance in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:616–620. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum RL, Stevens SA, Nash K, Koren G, Rovet J. Social cognitive and emotion processing abilities of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A comparison with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1656–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg-Damberger MM. The visual scoring of sleep in infants 0 to 2 months of age. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:429–445. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber R, Sadeh A, Raviv A. Instability of sleep patterns in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:495–501. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann D, Hewig J, Walter C, Naumann E. Skull thickness and magnitude of EEG alpha activity. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1271–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Zuloaga DG, McGivern RF. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters core body temperature and corticosterone rhythms in adult male rats. Alcohol. 2007;41:567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanft A, Burnham M, Goodlin-Jones B, Anders TF. Sleep architecture in infants of substance-abusing mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:141–151. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlicek V, Childiaeva R, Chernick V. EEG frequency spectrum characteristics of sleep states in full-term and preterm infants. Neuropadiatrie. 1975;6:24–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlicek V, Childiaeva R, Chernick V. EEG frequency spectrum characteristics of sleep states in infants of alcoholic mothers. Neuropadiatrie. 1977;8:360–373. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock H, Sciberras E, Mensah F, Gerner B, Efron D, Khano S, Oberklaid F. Impact of a behavioural sleep intervention on symptoms and sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and parental mental health: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;350:h68. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley S, Hill CM, Stevenson J. A comparison of actigraphy and parental report of sleep habits in typically developing children aged 6 to 11 years. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2009;8:16–27. doi: 10.1080/15402000903425462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chessonn A, Quan S. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: Rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Sato T, Takahashi K. Long-term follow-up study of a school refuser with non-24-hour sleep-wake rhythm. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1993;47:437–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1993.tb02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingrassia A, Turk J. The use of clonidine for severe and intractable sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders--A case series. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;14:34–40. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe S, Chernick V. Development of the EEG between 30 and 40 weeks gestation in normal and alcohol-exposed infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1988;30:797–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1988.tb14642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe S, Chernick V. Prediction of subsequent motor and mental retardation in newborn infants exposed to alcohol in utero by computerized EEG analysis. Neuropediatrics. 1990;21:11–17. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe S, Childiaeva R, Chernick V. Prolonged effects of maternal alcohol ingestion on the neonatal electroencephalogram. Pediatrics. 1984;74:330–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipsiroglu OS, McKellin WH, Carey N, Loock C. “They silently live in terror...” Why sleep problems and night-time related quality-of-life are missed in children with a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Soc Sci Med. 2013;79:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan JE, Asante KO, Conry JL, Fast DK, Bax MC, Ipsiroglu OS, Bredberg E, Loock CA, Wasdell MB. Sleep health issues for children with FASD: Clinical considerations. Int J Pediatr. 2010;2010:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2010/639048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]