Abstract

Media coverage of mental health and other social issues often relies on episodic narratives that suggest individualistic causes and solutions, while reinforcing negative stereotypes. Community narratives can provide empowering alternatives, serving as media advocacy tools used to shape the policy debate on a social issue. This article provides health promotion researchers and practitioners with guidance on how to develop and disseminate community narratives to broaden awareness of social issues and build support for particular programs and policy solutions. To exemplify the community narrative development process and highlight important considerations, this article examines a narrative from a mental health consumer-run organization. In the narrative, people with mental health problems help one another while operating a nonprofit organization, thereby countering stigmatizing media portrayals of people with mental illness as dangerous and incompetent. The community narrative frame supports the use of consumer-run organizations, which are not well-known and receive little funding despite evidence of effectiveness. The article concludes by reviewing challenges to disseminating community narratives, such as creating a product of interest to media outlets, and potential solutions, such as engaging media representatives through community health partnerships and using social media to draw attention to the narratives.

Keywords: journalism, community narratives, ethnography, mental health consumer-run organizations, mass media

Introduction

Health promotion researchers and practitioners often unearth a number of rich narratives that would appeal to a wide audience (e.g. Thomas, Owens, Friedman, Torres, & Hébert, 2013). Writing and publishing these narratives can provide the public with thoughtful, engaging, and accurate materials that raise awareness about important social issues. Community narratives can also support project dissemination efforts, thereby appealing to funding agencies (Olson, Cooper, Viola, & Clark, 2016; Tetroe et al., 2008). In this paper, we examine and provide practical guidance on how to develop and disseminate community narratives that build support for particular health promotion programs and policy solutions.

To exemplify their utility, we discuss a community narrative that counters negative stereotypes about mental illness and raises the profile of mental health consumer-run organizations, which are an evidence-based approach to promoting recovery (Nelson, Ochocka, Janzen, & Trainor, 2006; Segal, Silverman, & Temkin, 2010, 2013). Consumer-run organizations are independent nonprofits operated by people with mental illness (Brown & Townley, 2015). Organizational activities often include maintaining a drop-in center, hosting support groups, and pursuing mental health advocacy initiatives (Brown, Shepherd, Wituk, & Meissen, 2007).

Background

Foundations of community narrative

Narratives are stories or accounts of connected events, which have a natural connection to lay readers (Kottler, 2014). Through narrative, humans shape their identity, ascribing meaning to themselves and the world (Merrill & Fivush, 2016). Community narratives are collective stories that community members share with each other, which are then integrated into personal life stories (Rappaport, 2000). Mental health community narratives can reduce stigma by countering media portrayals that focus on people acting in a violent or deranged manner (Parrott & Parrott, 2015).

Community narratives as media advocacy tools

Despite the value of community narratives, mass media outlets rarely publicize them (Dorfman & Gonzalez, 2012). Instead, journalists tend to focus on emotionally compelling individual stories where problems are typically resolved through the protagonist’s efforts (Editors of Writer’s Digest, 2012). Regardless of author intentions, readers tend to attribute both problems and solutions to individual decisions rather than societal or community contextual factors (Dorfman & Gonzalez, 2012). When news stories are framed episodically (focusing on anecdotal stories to illustrate trends), audiences tend to attribute causes of problems to the individual, whereas when stories have thematic frames (looking at the larger environment and institutions) viewers tend to place more blame on society and government (Gearhart, Craig, & Steed, 2012; Kim & Demers, 2013). Community narratives address these problems by examining the community’s influence on the lives of its participants rather than focusing on individual problems and problem-solving efforts. By disseminating community narratives that implicate particular programs or policies as solutions to the problem of interest, health promotion practitioners can increase public support for said programs or policies.

Episodic narratives may be particularly problematic in the context of social media, where readers’ engage less with the original narrative and more with social media commentary (Gershoff & Mukherjee, 2015). The commentary often idolizes or villainizes the narrative’s characters (Shigeta et al., 2017). Community narratives help to limit this behavior in social media settings by reducing emphasis on individual characters, instead creating a forum that is well-positioned to promote civic engagement and political participation around community narrative related issues (Gil de Zúñiga, Jung, & Valenzuela, 2012).

Community narratives for health education

Narratives also have the potential to be powerful educational tools that promote behavior change (Murphy et al., 2015). For example, the universally compelling nature of narrative storytelling can help engage focal audiences in health-related messages while minimizing the message resistance that arises during direct persuasive appeals (Aronson, 2012). Narratives can provide readers with healthy behavioral models that, if perceived as credible, can reduce message resistance, promote observational learning, and enhance self-efficacy to undertake similar behaviors (Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007). Mental health community narratives may give people hope in their potential for recovery and motivation to get involved in a recovery-promoting community, such as a consumer-run organization (Brown, Shepherd, Wituk, & Meissen, 2008).

Example community narrative project

To illustrate the writing of community narratives, the “method” describes a life history and community narratives project conducted in collaboration with members of a mental health consumer-run organization. The “results” section contains the narrative, which sought to counter negative stereotypes about mental illness and serve as a media advocacy tool, promoting the use of an evidence-based approach to mental health recovery. By analyzing the community narrative in the “discussion” section, we aim to clarify how journalistic principles can be integrated into health promotion projects, facilitating the dissemination of community narratives.

Method

The narrative study sought to understand people’s life stories and how their entwinement with a consumer-run organization promoted mental health and community integration. Substantial detail on the nature of this project and its methods are provided elsewhere (Brown, 2009, 2012). Study procedures received institutional review board approval.

Study setting and sample

The consumer-run organization under study was the P.S. Club, which operated in a small town as a nonprofit with four part-time staff members. The organization had a membership of approximately 30 people, with a core group of 5 to 10 regular attendees. Participants were predominantly non-Hispanic white, and evenly split between men and women. Participants were most often in their fifties and had an average of educational attainment of a high school degree.

Observations and interviews at the P.S. Club

The project began with participant observations at the P.S. Club. Over an 18-month period there were 32 observations at the P.S. Club, which typically lasted 3–4 hours each. A series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 7 participants also supported the development of the community narrative. During the interviews, we wanted participants to tell their stories in their own words, including their challenges, how those challenges influenced their lives, and what each participant had done to overcome challenges.

Community narrative construction

In writing the community narrative of the P.S. Club, we focused on summarizing how the club influenced the lives of community participants. The lead author reviewed observation notes and transcripts to draft the narrative, with supporting authors providing subsequent input to further refine it. The finished product aimed to educate readers about the nature of severe mental health problems and the utility of consumer-run organizations as part of the treatment system. Reliance on quotes in the write-up allowed participants to speak for themselves, thereby enabling the narratives to provide an insider’s perspective on how consumer-run organizations can be beneficial.

Although we attempted to convey the insider’s perspective with the narrative, our scientific perspective heavily influenced narrative construction. We decided which quotes to present and organized those quotes in a manner consistent with our understanding of the P.S. Club. The blend of perspectives in narratives is similar to the write-up of traditional ethnographic material, where the author blends data from the field with their own understanding of the situation. Thus, narrative represents the complex interplay between lived experience and storyteller interpretation (Josselson & Hopkins, 2015). After producing a draft narrative, we shared it with participants, in an effort to promote accuracy and avoid publishing details participants did not want to share. Pseudonyms are used to protect the identities of individual participants.

Results - A Journalistic Community Narrative of the P.S. Club

As executive director of a mental health organization, Nick fights against the stigma that people with mental disorders face.

“They just hear the name schizophrenia and they automatically think you are a bad person,” he says.

Nick isn’t just sympathetic because of his role. He has schizophrenia, a complex disorder that can cause people to see or hear things that aren’t there, have false beliefs such as others are out to get them, or become completely inactive. One percent of the population has the disorder.

The stigma that isolates people with schizophrenia was the impetus for the creation of Nick’s organization, the P.S. Club, a self-help organization where people with mental illness find acceptance and support. Filling an important gap in the mental health system, the P.S. club recognizes that “people with mental illness […] want the same kinds of relationships and stuff that people that don’t have a mental illness want.” says Nick. “They want someone to care about, someone to be there for them.”

The P.S. Club opened in 1993 when Nick wrote a grant to the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services. There are 21 such consumer-run self-help organizations in Kansas staffed by people with mental illnesses, who do everything from administration to vacuuming.

With its home in the town of Wellington, Kanas, the club developed as a place where people can drop-in and socialize with people who understand the torment of having a mental disorder. “It’s given me a place to go to so I don’t have to sit here and be by myself all day,” says Carl, president of the club’s board of directors and who has depression. These recreational activities promote the development of lasting friendships. “If I’m in a store or someplace and somebody from the P.S Club sees me, they’ll always stop and say hello and that’s a good feeling. Real good feeling.” In turn, the friendships have served as a powerful antidepressant. Carl attributes a large part of his recovery from depression to his socializing at the club. “I think a lot of it has to do with me just coming to the clubhouse. Having somebody to talk to,” he says. Club members say it’s nice to face their challenges with each other, but they want their camaraderie even when times are easier. “Just for happiness in life,” says Nick, “everybody needs friends.”

In an effort to further promote the recovery of members through relationships, the P.S. Club started a peer counseling program, which helps both the counseling providers and recipients. “I’ve done a lot of peer counseling in the last probably 15 years. Finding ways to help me help somebody else has actually helped me too,” says Carl.

With a successful drop-in center and peer counseling program in place, the P.S. Club began to pursue efforts aimed at changing the broader community. Members started attending conferences such as the Kansas Recovery Leadership Summit, where participants worked to identify and prioritize mental health policy reforms. Nick discussed the need to reform a new drug prescription program that lowers costs for many medications but few for mental health. “So there again, you know, it’s a good program but we’re left out,” he says with frustration.

Club members also started working to reduce stigma in their community by delivering educational presentations about mental illness and their organization. Nick and Carl gave a presentation at a local high school, where they talked about their struggles with mental illness. “One thing that I want to emphasize with you is that if anything happens with you, don’t give up. Just don’t give up and say forget it,” said Carl. “Keep going, because you can be your own best friend or you can be your own worst enemy as well.” In the end, their message was simple – mental illness is a challenge to be overcome, much like any other problem humans face.

Members are learning to fulfill commitments and become leaders by taking on roles and responsibility in the P.S. Club. “Some of them will eventually, you know, be willing to take on leadership roles and stuff like that, which gives them a real sense of accomplishment, and makes them feel good about themselves,” says Nick. Serving as leaders and taking on responsibilities helps many in the P.S. Club gain personal insight and improve self-esteem.

Through all of its efforts, the P.S. Club supports the recovery of approximately 25% of Sumner County residents with severe mental health problems who are seeking treatment. It reaches many more through its advocacy and stigma reduction activities. In the end, it may simply be the presence of such an organization that changes perceptions the most, exemplifying the potential of people who were once locked away in psychiatric hospitals.

Discussion

The P.S. Club narrative provides an example of health promotion practitioners using their existing relationships and areas of interest to write a community narrative that applies several principles of journalism. The resulting narrative counters stereotype-reinforcing sensationalized portrayals of mental illness, thereby helping to reduce stigma. Further, it focuses reader attention on the value of consumer-run organizations as an approach to recovery rather than the feats of a particular person with mental health problems. By doing so, readers are more likely to conclude that addressing mental health challenges requires collective action and community supports rather than blaming mental illness on poor decision making and personal failures (Ocasio & Weintraub, 2014). The problem addressed by community narratives is not unique to mental health however. Health disparities, obesity, youth violence, and numerous other health issues struggle with similar media framing problems (Gearhart et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2010).

Integrating journalism into community narratives

Health promotion practitioners have the relationships in place to write compelling community narratives but may lack training and experience. Although the basics can be learned relatively quickly, partnerships between journalists and health promotion practitioners are one way to bridge the gap between health promotion and journalism. Multi-sector community health partnerships may be particularly well suited to engage health promotion practitioners and journalists in collaborative efforts to disseminate community narratives (Brown et al., 2013; Butterfoss, 2007). The partnerships can provide journalists with opportunities to develop contacts for health stories and health promotion practitioners with access to the media.

Health promotion researchers and practitioners interested in pursuing community narratives can apply several principles of journalistic feature writing to enhance their narratives. A journalistic feature typically begins with a compelling lead that draws the reader into the story in the opening paragraphs. The P.S. Club narrative begins with a cause and effect relationship lead, which serves to explain how one event triggers another event central to the story (Friedlander & Lee, 2011). In the P.S. Club narrative, the lead explains how the stigma and isolation faced by people with mental illness (the cause) is the impetus for the creation of the P.S. Club (the effect). In keeping with the tenets of journalistic writing, the narrative presented uses short sentences, brief paragraphs, extensive quotes, and avoids jargon. The conclusion is also important in journalistic writing because it rewards the reader for finishing the story. The P.S. Club narrative concludes with quotes about hope and recovery that provide the reader with a sense of closure while still acknowledging ongoing struggles.

Story structure

Narrative arc is a classic story structure that focuses the audience on the main character’s central problems and her successes and failures in addressing them (Friedlander & Lee, 2011). Thus, use of narrative arc helps give a narrative practical value, providing the audience with a template for solving similar problems (i.e. the moral of the story). At the beginning of a story with narrative arc, the main character is briefly established and then presented with a problem to overcome. In a community narrative, the community takes the place of the main character. Thus, in the example narrative, the P.S. Club is the focus and the story explores how the organization promotes recovery from mental health problems.

Towards the end of a dramatic story with narrative arc, the main character resolves the central problem in a climatic event and the story ends. Community narratives offer the opportunity to break the individual-effort-triumphs-over-all narrative, as contrived and simplistic endings are not necessary for a compelling story. The P.S. Club narrative reflects the reality that the club helped participants improve quality of life and make recovery progress, although challenges remain.

Narrative arc is nevertheless useful because it helps to focus the story on a central plot, which connects various life events and happenings, providing an explanation of how the events lead to a particular outcome (Cohn, 2013). In the P.S. Club study, the particular outcome of interest was the mental health and community integration of the P.S. Club participants. Recursive movement between the data and the emerging story outline enabled plot identification and refinement. Inconsistencies between major developments in each participant’s life and the preliminary plot indicate the need for plot refinement. However, minor events that do not contradict the plot but do not further its development may be excluded from the story. Development of a plot helps the narrative focus on events that led to the current outcome of interest (Daiute, 2014). As such, plot identification is critical from both a storytelling and an analytic perspective, as it makes the story more compelling and focused on consequential events.

Plot refinement aids in the identification of both key problems and effective solutions since problems and solutions together drive the plot. By identifying solutions through plot refinement, health promotion practitioners can rewrite stereotype-reinforcing dominant cultural narratives into life-enhancing community narratives that allow personal stories to become tales of resilience (Rappaport, 2000).

Visual storytelling

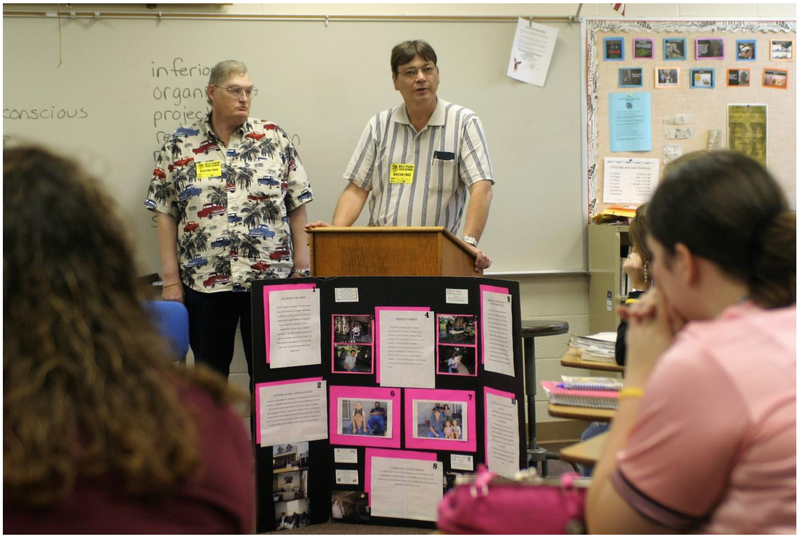

Still photography and video help draw the reader into the story with emotionally compelling information, increasing readership and the potential for dissemination (Gitner, 2015). Visuals provide unique contextual information about the P.S. Club and communicate important non-verbal information such as emotions and how people present themselves (Harrison, 2002). In the P.S. Club narrative, the photos complement and elaborate upon the prose in varying ways. For example, Figure 1 captures P.S. Club members laughing while playing cards, illustrating the connections participants make. Figure 2 illustrates the passionate presentations given by P.S. Club members, which help to reduce stigma and provide members opportunities to develop leadership skills.

Figure 1.

Recreational activities such as playing cards serve as a medium for the development of friendships at the P.S. Club.

Figure 2.

The P.S. Club is always looking for places to make public presentations about mental health problems and the activities of their organization, such as this presentation to a high school psychology class. The students were brimming with questions, curious about life with mental health problems.

Narrative dissemination opportunities and challenges

A principal question about community narratives is where they might be published. One dissemination option is to pursue newspaper, magazine, trade journal, and trade book outlets. The annual publication, “Writer’s Market” provides a listing of publishers that accept freelance submissions (Brewer, 2016). The communities represented by the narratives may also be interested in distributing them in their own newsletter or marketing efforts. Health promotion practitioners can also disseminate narratives in educational contexts. For example, the community narrative about the P.S. Club and life history narratives about its participants are published in a book (Brown, 2012). Self-publishing a book and selling it on http://Amazon.com or another online retailer is also an option. Websites are a dissemination method that provides maximum accessibility. Organizations interested in the topic may be willing to post or provide links to the narratives.

Creating a video version of the narratives is another dissemination option. The video produced as part of the example study [https://tinyurl.com/makingitsane] is used by consumer-run organizations during their presentations in the community to raise awareness about mental illness and how their organizations can be helpful. Some consumers have noted that the video narratives are inspiring and helpful in understanding the recovery process, reflecting the potential of video narratives as a tool for health promotion.

Local media outlets can also help disseminate narratives. For example, health promotion practitioners can collaborate with a community to create a press release that includes key community narrative information. Connecting the press release to a news peg, such as an important community event or anniversary, can help to garner media attention. If journalists cover the event, they are likely to draw heavily from a well-constructed press release or fact sheet in creating their story (Rock, McIntyre, Persaud, & Thomas, 2011).

An important consideration for health promotion researchers and practitioners pursuing the dissemination of narratives is its impact on funding and career advancement. Although narratives are not core deliverables for most projects, media attention does raise the profile of the authors, which organizations value. Further, it supports project dissemination efforts, which are a key consideration for funding agencies. Thus, although narrative dissemination requires substantial time commitments, it also provides meaningful career and project benefits.

Limitations to community narratives

A key tension in our approach to creating a community narrative is that, as outsiders, we created a representation of the community of interest and worked to disseminate it. Although we took steps to engage community members in the storytelling process, such as by getting their feedback on narratives, their limited influence diminished the empowering potential of this project. However, narratives created by community members may be less appealing to a broad audience unless their creators have relevant storytelling experience. Participant comments about their stories and the process of telling them can enhance understanding of the differences between writer and community member perspectives. Alternatively, oral history methods could be adopted and utilized, allowing participants to tell their stories in the first person.

Conclusions

Empowering community narratives are a promising strategy for improving well-being. Sharing such narratives with a broader audience can raise awareness of critical challenges and promising solutions without focusing undue attention on individual-level causes. Integrating the principles of journalism into community narrative construction efforts can aid narrative dissemination efforts, promote policy change, and help close the research to practice gap.

Acknowledgements:

Support for this research comes from the Kansas Department for Children and Families. Additionally, this article is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) through a Community Networks Program Center grant U54 CA153505. Findings and recommendations herein are not official statements of these agencies. The authors would also like to thank Greg Meissen, Lou Medvene, Sharon Iorio, Deac Dorr, and Darcee Datteri for their feedback on earlier versions of this work..

Biographies

Louis D. Brown, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Public Health in El Paso, Texas.

Joseph C. Berryhill, Ph.D., is a Clinical Psychologist at Quetzal Associates in East Providence, Rhode Island.

Eric C. Jones, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, Human Genetics and Environmental Sciences at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Public Health in El Paso, Texas.

References

- Aronson E (2012). The social animal (11th ed.). New York: Worth. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer RL (Ed.) (2016). Writer’s market 2017: The most trusted guide to getting published (95th ed.). New York: Writer’s Digest Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD (2009). Making it sane: Using life history narratives to explore theory in a mental health consumer-run organization. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 243–257. doi: 10.1177/1049732308328161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD (2012). Consumer-run mental health: Framework for recovery. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Alter TR, Brown LG, Corbin MA, Flaherty-Craig C, McPhail LG, . . . Weaver ME (2013). Rural Embedded Assistants for Community Health (REACH) Network: First-person accounts in a community-university partnership. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 206–216. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9515-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Shepherd MD, Wituk SA, & Meissen G (2007). Goal achievement and the accountability of consumer-run organizations. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 34, 73–82. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9046-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Shepherd MD, Wituk SA, & Meissen G (2008). Introduction to the special issue on mental health self-help. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 105–109. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9187-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, & Townley G (2015). Determinants of engagement in mental health consumer-run organizations. Psychiatric Services, 66, 411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss FD (2007). Coalitions and partnerships in community health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn N (2013). Visual narrative structure. Cognitive Science, 37(3), 413–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiute C (2014). Narrative inquiry: A dynamic approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman L, & Gonzalez P (2012). Media advocacy: A strategy for helping communities change policy In Minkler M (Ed.), Community organizing and community building for health and welfare (pp. 407–420). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Editors of Writer’s Digest (Ed.) (2012). Crafting novels & short stories: The complete guide to writing great fiction. New York: Writer’s Digest Books. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander EJ, & Lee J (2011). Feature writing: The pursuit of excellence (7th ed.). New York: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart S, Craig C, & Steed C (2012). Network news coverage of obesity in two time periods: An analysis of issues, sources, and frames. Health Communication, 27, 653–662. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.629406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff AD, & Mukherjee A (2015). Online social interaction In Norton MI, Rucker DD, Lamberton C, Norton MI, Rucker DD, & Lamberton C (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of consumer psychology. (pp. 476–503). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gil de Zúñiga H, Jung N, & Valenzuela S (2012). Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17, 319–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gitner S (2015). Multimedia storytelling for digital communicators in a multiplatform world. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison B (2002). Photographic visions and narrative inquiry. Narrative Inquiry, 12(1), 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hinyard LJ, & Kreuter MW (2007). Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education & Behavior, 34, 777–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josselson R, & Hopkins B (2015). Narrative psychology and life stories Martin Jack [Ed]; Sugarman Jeff [Ed]; Slaney Kathleen L [Ed] (2015) The Wiley handbook of theoretical and philosophical psychology: Methods, approaches, and new directions for social sciences (pp 219–233) xiv, 478 pp Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kim AE, Kumanyika S, Shive D, Igweatu U, & Kim S-H (2010). Coverage and framing of racial and ethnic health disparities in US newspapers, 1996–2005. American Journal of Public Health, 100, S224–S231. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, & Demers D (2013). How the mass media really work : An introduction to their role as agents of control and change. Spokane, WA: Marquette Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kottler J (2014). Stories we’ve heard, stories we’ve told: Life changing narratives in therapy and everyday life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill N, & Fivush R (2016). Intergenerational narratives and identity across development. Developmental Review, 40, 72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, Moran MB, Zhao N, de Herrera PA, & Baezconde-Garbanati LA (2015). Comparing the relative efficacy of narrative vs nonnarrative health messages in reducing health disparities using a randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 2117–2123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Ochocka J, Janzen R, & Trainor J (2006). A longitudinal study of mental health consumer/survivor initiatives: Part 2--A quantitative study of impacts of participation on new members. Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ocasio LR, & Weintraub K (2014). Cultivating courage, compassion, and cultural sensitivity in news reporting of mental health In Parekh R & Parekh R (Eds.), The Massachusetts General Hospital textbook on diversity and cultural sensitivity in mental health. (pp. 277–293). Totowa, NJ, US: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olson BD, Cooper DG, Viola JJ, & Clark B (2016). Community narratives In Jason LA, Glenwick DS, Jason LA, & Glenwick DS (Eds.), Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. (pp. 43–51). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott S, & Parrott CT (2015). Law & disorder: The portrayal of mental illness in U.S. crime dramas. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(4), 640–657. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2015.1093486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J (2000). Community narrative: Tales of terror and joy. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock MJ, McIntyre L, Persaud SA, & Thomas KL (2011). A media advocacy intervention linking health disparities and food insecurity. Health Education Research. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal SP, Silverman CJ, & Temkin TL (2010). Self-help and community mental health agency outcomes: A recovery-focused randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services, 61(9), 905–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.9.905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal SP, Silverman CJ, & Temkin TL (2013). Self-Stigma and empowerment in combined-CMHA and consumer-run services: Two controlled trials. Psychiatric Services, 64(10), 990–996. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigeta N, Ahmed S, Ahmed SW, Afzal AR, Qasqas M, Kanda H, . . . Turin TC (2017). Content analysis of Canadian newspapers articles and readers’ comments related to schizophrenia. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 10, 75–81. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2016.1261167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Wensing M, . . . Grimshaw JM (2008). Health research funding agencies’ support and promotion of knowledge translation: An international study. Milbank Quarterly, 86, 125–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00515.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TL, Owens OL, Friedman DB, Torres ME, & Hébert JR (2013). Written and spoken narratives about health and cancer decision making: A novel application of photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 14, 833–840. doi: 10.1177/1524839912465749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]