Abstract

Introduction

The objectives of this study were to identify knowledge gaps and/or perceived limitations in the performance of paediatric appendiceal ultrasound by Australasian sonographers. We hypothesised that: sonographers’ confidence in visualising the appendix in children was poor, particularly outside predominantly paediatric practice; workplace support for prolonging examinations to improve visualisation was limited; and the sonographic criteria applied in diagnosis did not reflect contemporary literature.

Methods

A cross‐sectional survey of Australasian sonographers regarding paediatric appendicitis was conducted using a mixed methods approach (quantitative and qualitative data). Text responses were analysed for key themes, and quantitative data analysed using chi‐square, Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed‐rank tests.

Results

Of the 124 respondents, 27 (21.8%) reported a visualisation rate of less than 10%. Workplace support for extending examination time was significantly related to a higher appendix visualisation rate (χ 2(2) = 16.839, P < 0.001). Text responses reported frustration locating the appendix and a desire for more time and practice to improve visualisation. Sonographers suggested a significantly lower maximum diameter cut‐off in a 5‐year‐old compared to a 13‐year‐old (Z = −6.07, P < 0.001), and considered the presence of inflamed peri‐appendiceal mesentery as the most useful sonographic criterion in diagnosing acute appendicitis.

Conclusions

Respondents had a low opinion of their ability to confidently identify the appendix. Confidence was greater in those centres where extending scanning time was encouraged. Application of echogenic mesentery as the most significant secondary sonographic criterion is supported by recent studies. Opinions of diameter cut‐offs varied, indicating potential for improved awareness of recent research.

Keywords: Appendicitis, mixed methods, paediatric, sonographer, ultrasonography

Introduction

Ultrasound has a well‐established role as the first‐line imaging modality in children with suspected acute appendicitis.1 Ultrasound can be a reliable and accurate imaging modality in the paediatric cohort,2 without the potential harm inherent to ionising radiation from computed tomography (CT).3 However, diagnosis in children can be complex, with clinical assessment often limited by challenges in communication and history that are more easily addressed in an adult cohort. Whilst typical clinical findings as well as blood counts and inflammatory markers can suggest appendicitis, imaging is often required when the diagnosis is uncertain.4, 5 The utility of ultrasound examination in diagnosing appendicitis has been reviewed and analysed, with the critical role of the sonographer acknowledged in diagnostic accuracy.6, 7, 8

The ability of individuals to identify the appendix using ultrasound varies considerably, with visualisation rates ranging from 21% to 99%.9, 10 Identification of the entire appendix is critical to making the most accurate assessment for patients and clinicians.11 Sonographers in paediatric hospitals and centres that perform paediatric appendix ultrasound more frequently have higher reported visualisation rates than those based at centres that do not focus solely on children, where perceived lower diagnostic performance of ultrasound may contribute to more frequent CT requests compared with initial presentations at children's hospitals.12, 13, 14, 15 Recent findings from a paediatric centre averaging at least two appendix examinations per day, found sonographers were identifying the appendix in 91.7% of cases, and emphasised the importance of flexibility in examination time in the workplace.16

Application of current ultrasound criteria for diagnosing appendicitis also plays a role in the accuracy and value of examinations, with recent studies reviewing appendiceal diameter size criteria as an assessment tool and evaluating the value of secondary sonographic signs of inflammation.17, 18 Strict application of a binary diameter cut‐off has been shown to be responsible for a number of false‐positive diagnoses, and use of a range of diameters (6–8 mm) as an upper limit of normal, in conjunction with other sonographic criteria, has been proposed.17, 18 Sonographer awareness and integration of secondary signs of inflammation into examination findings have been demonstrated to improve the diagnostic value of appendix ultrasound.19, 20

The objectives of this study were to identify knowledge gaps and/or perceived limitations in performance of paediatric appendiceal ultrasound by Australasian sonographers. We hypothesised that: sonographers’ confidence in visualising the appendix during these examinations was poor, particularly outside paediatric hospitals; that there is a lack of workplace support for prolonging examinations to improve appendix visualisation; and the sonographic criteria applied in diagnosing appendicitis did not reflect contemporary literature.

To our knowledge, this is the first survey undertaken to identify sonographers’ opinions regarding performance of appendiceal ultrasound. Whilst the body of literature on appendix ultrasound has steadily grown, in Australasia it has primarily involved only tertiary centres.11, 16, 18, 21 It is therefore important to identify knowledge gaps and perceived limitations amongst the sonographers performing these studies not only in hospitals, but also in the wider medical imaging community. Such data may provide targets for future education and operational development, leading to improved practice.

Methods

The study utilised a mixed methods cross‐sectional survey of Australasian sonographers. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from participant responses to questions concerning sonographic criteria for appendicitis, opinions of their exam performance and examination strategies. The Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) assessed this research as meeting the conditions for exemption from HREC review and approval in accordance with section 5.1.22 of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2015), as it is research of negligible risk involving non‐identifiable data.

Recruitment

A survey invitation was emailed to 857 sonographers who had registered to participate in an online webinar related to paediatric appendicitis, hosted by the Australasian Sonographers’ Association (ASA) in June 2017. The survey closed 30 min prior to the commencement of the webinar presentation to avoid introducing bias into responses based on material discussed in the presentation. Based on a population of 4671 Australasian sonographers from 2016 data,22, 23 a sample of 95 respondents would be required to achieve 95% confidence intervals using a 10% margin of error.

Instrument

A nine‐question survey hosted on KeySurvey®(Version 8.17, Braintree, MA, USA) was developed based on factors identified in previous qualitative studies in Australasian hospitals, that influenced the outcomes of appendiceal ultrasound examinations.11, 16, 18, 21 Questions were selected by Australian clinical experts (a specialist paediatric sonographer and consultant paediatric radiologist), and two academics with extensive experience in quantitative and qualitative analysis. Participants were invited to complete non‐compulsory questions including: length of ultrasound experience (years); employment status full‐time equivalency (FTE); proportion of paediatric workload (% caseload); perception of workplace support for prolonging examinations (yes, no, not sure); confidence visualising the appendix with ultrasound (% visualisation rate); a choice of up to three of eight sonographic criteria for acute appendicitis they considered most useful, including an option to detail other criteria not included in the closed responses available; and an open‐ended question regarding their experience in appendiceal sonography. Upon receipt of an email invitation, a link displayed the study information sheet and participants were asked to proceed through the survey following their consent. Data were collected between the 8 and 14th of June 2017.

Data analysis

Text responses to an open‐ended question were analysed using NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. (Version 11, 2016, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) to identify key themes using an immersion/crystallisation approach.24, 25 Data obtained from responses were exported into Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis.

Where responses to questions resulted in low numbers in some cells, data were aggregated into smaller scales: full‐time equivalency responses in daily increments collapsed into a scale of 2‐day increments; visualisation rate responses, where 10% intervals were collapsed into four categories (<20%, 20–50%, 50–70%, >70%); and paediatric case load into a binary variable of greater or less than 50% paediatric case load.

Chi‐square tests of independence were used to identify significant relationships between ordinal variables (career length, FTE) about participant reported visualisation rate. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine differences between paediatric workload proportion and visualisation rate. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to determine significant differences between workplace support for prolonged examinations and visualisation rate, with post hoc pairwise comparisons between groups. A Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was used to compare responses to maximum appendiceal diameters at different ages. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Of those sonographers who were emailed the survey, 183 (21.4%) opened the link and viewed the information page, and 124 (14.5%) went on to complete the survey (2.7% of 4671 Australasian sonographers). One respondent declined to answer questions on career length and proportion of paediatric workload. There were 23 responses (18.5% of respondents) to the open‐ended question.

Demographics

Seventy‐two (58.1%) respondents reported practicing for over 10 years. Only 14 (11.3%) were students or in their first year of practice (Table 1). Seventy‐four (59.7%) sonographers worked at least 4 days/week (0.8 FTE), with only four (3.2%) working 2 days/week or less (0.2 FTE).

Table 1.

Respondent's career length

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Student | 7 | 5.6 |

| <1 year | 7 | 5.6 |

| 1–5 years | 17 | 13.7 |

| 5–10 years | 20 | 16.1 |

| >10 years | 72 | 58.1 |

| No response | 1 | <0.1 |

| Total | 124 | 100.0 |

Visualisation rate

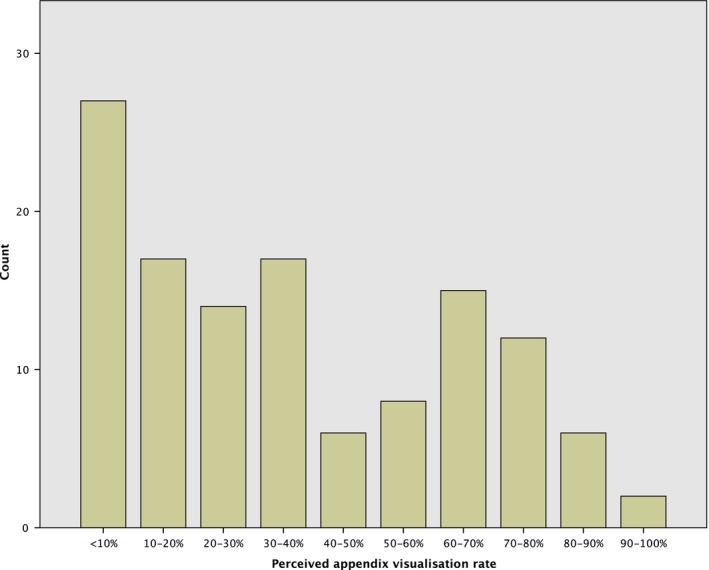

Eighty‐one (65.3%) respondents stated a perceived visualisation rate of less than 50%, with 27 (21.8%) citing less than 10%, and a median category of 10–20% (IQR < 10% to 30–40%) (Fig. 1). There were no significant associations between visualisation rate and FTE (χ 2(12) = 5.602, P = 0.935) or career length (χ 2(9) = 8.842, P = 0.452).

Figure 1.

Respondents reported ability to locate the appendix during ultrasound examinations of children with suspected appendicitis.

Paediatric case load

One hundred and six sonographers (85.5%) had a paediatric caseload of 25% or less, with only eight (6.4%) stating that they had a 50% or greater paediatric load, therefore responses were collapsed into a binary variable of those performing more, or less than, a 50% paediatric case‐load respectively (Table 2). The Mann–Whitney U test showed a statistically significant difference in visualisation rate between sonographers’ paediatric caseloads (U = 175.5, P = 0.002), sonographers with greater than 50% paediatric caseload had a mean rank of 97.56 compared to 59.53 for those with less than a 50% paediatric caseload.

Table 2.

Respondent's paediatric caseload proportion

| Proportion | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0% (no paediatrics) | 9 | 7.3 |

| 25% | 106 | 85.5 |

| 50% | 1 | <0.1 |

| 75% | 1 | <0.1 |

| 100% | 6 | 4.9 |

| No response | 1 | <0.1 |

| Total | 124 | 100.0 |

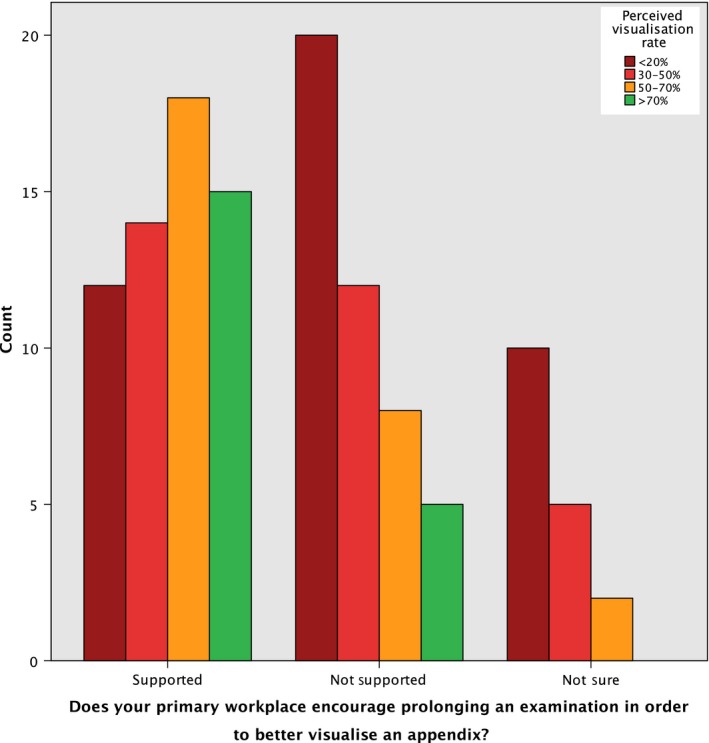

Workplace support

Fifty‐nine sonographers (n = 59, 47.6%) felt supported by their workplace to prolong an appendix ultrasound examination to improve visualisation; 45 (36.3%) thought that shorter examination times were a priority while 17 (13.7%) were not sure of their workplace policy in this regard. A Kruskal–Wallis H test showed statistically significant differences in visualisation rate between these three groups (χ 2(2) = 16.839, P < 0.001), with a mean rank score of 73.18 for those with workplace support, 52.97 with no support, and 40.00 where respondents were not sure of support(Fig. 2). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that workplace support to prolong appendix ultrasound examinations when required was associated with a higher perceived visualisation rate compared to those with no support (P = 0.007) or not sure of support (P = 0.001), while there was no statistically significant difference in perceived visualisation rate between respondents who felt no support or were not sure (P = 0.530).

Figure 2.

Perceived workplace support and visualisation rates.

The workplace support question also provided sonographers an option for a free‐text response that elicited 10 comments including: provided the distress to patient was not increased; that whilst there was support, no schedule adjustments were made; that the perception in public hospitals was that prolonged examinations are supported, with limited examination windows in private practices; that prolonging examinations depended on the workload at the time; that sonographers used their discretion to prolong exams and bore the responsibility for “catching up” as a result.

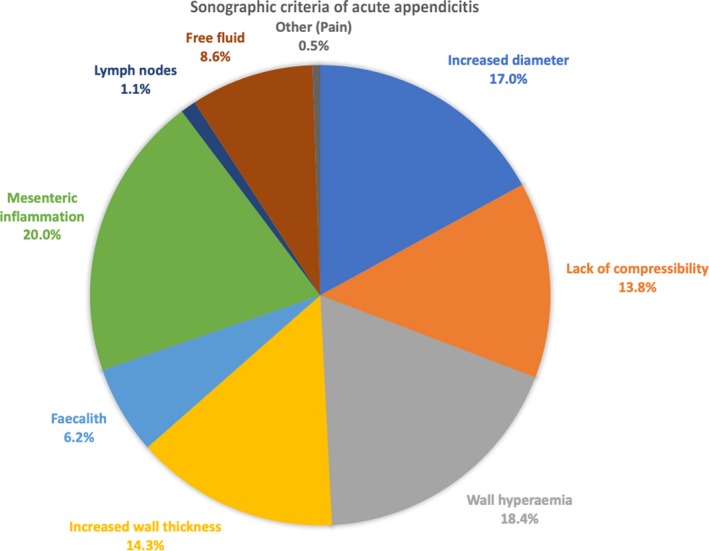

Sonographic criteria

Sonographers had significantly different responses to the maximum appendiceal diameter based on a child's age (Z = −6.07, P < 0.001), with a lower cut‐off suggested in a 5‐year‐old compared to a 13‐year‐old. The 124 sonographers gave 370 responses to the three sonographic criteria considered most useful when diagnosing acute appendicitis. These were: the presence of inflamed peri‐appendiceal mesentery 74 responses (20.0%); wall hyperaemia 68 responses (18.3%); and an increased appendiceal diameter 63 responses (17.0%); with the other criteria detailed in Figure 3, including two “other” open‐ended responses of migrating pain and a blind ending aperistaltic tube.

Figure 3.

The sonographic criteria reported as most useful in diagnosing acute appendicitis amongst respondents.

Open‐ended question responses

Subjective barriers identified in open text responses included: a lack of experience; limited exposure to a paediatric case load and frustration that there was a low level of clinical suspicion for the condition in children referred for appendix ultrasound. One respondent stated they “always say ‘appendix not identified’ and always have trouble identifying the appendix whether normal or abnormal”. Key themes identified in text responses included strategic/technical suggestions, and challenges that faced sonographers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Key themes from open text responses

| Strategic/technical tips | Challenges identified |

|---|---|

| Seeking assistance from a second sonographer or radiologist when the appendix is not initially identified | Difficulty locating the appendix, particularly when normal |

| Need for time/patience to improve visualisation | Lack of experience/practice in appendix sonography |

| Use of published criteria/scores, and complementary clinical information | Referral of children with low clinical suspicion |

| Small paediatric case‐load | |

| Difficulty locating the appendix, particularly when normal |

Discussion

Confidence visualising the appendix during paediatric ultrasound examinations was low, with over half of respondents (n = 81, 60.5%) only expecting to identify the appendix in every second examination, and 21.8% (n = 27) in one in ten examinations. This did not change significantly when considering career length or FTE. The eight sonographers (6.5%) who worked more than half their time in paediatrics responded with significantly greater confidence in visualisation. Research citing high rates of visualisation and accuracy in specialist centres and tertiary hospitals is not necessarily reflective of outcomes in most centres.26 Whilst knowledge that colleagues in paediatric practice have higher visualisation rates sets a bench mark for sonographers outside these centres, it might be of limited practical value in their clinical setting. Given many children do not present directly to paediatric hospitals, it is important to address the low level of diagnostic confidence that exists outside these specialist environments. A sonographer's confidence in their examination findings influences the radiology report seen by referring clinicians. For instance, in non‐paediatric centres with low referrer confidence in appendix ultrasound findings, there are higher rates of CT than for tertiary centres.27 An unambiguous, or even less ambiguous, examination finding could alter the pre‐test probability of a suspected condition and dictate referral preferences.

Approximately half of the sonographers who responded (n = 59, 48.8%) reported working in centres where they felt supported to take the time and steps necessary to extend an ultrasound examination if required and this was significantly (P = 0.003) associated with perceived improvement in visualisation rates. Those sonographers who responded that they were unsure or did not feel supported in their workplace to prolong an examination had lower confidence in their visualisation rate, suggesting that perceived workplace limitations regarding examination time, could potentially be detrimental to the quality of examination findings. Optional free‐text responses to this question reinforced this finding, stating that sonographers used their own discretion to prolong examinations and often took responsibility for any ensuing delays or other resultant impacts to the remainder of their scheduled list.

Survey respondents also described organisational strategies to improve practice as beneficial. These included: a policy to have a second sonographer/radiologist scan the patient when the appendix is not initially identified; and opportunity to take more time when required to extend the scan until complete visualisation is achieved. Complete visualisation of the appendix should be the goal of every examination; however, sometimes despite a dedicated attempt, visualisation is not successful. In these instances, ultrasound can still be useful to clinicians through the evaluation of secondary sonographic signs of appendicitis and their inclusion in the examination findings. A report that states “Appendix not identified, however no secondary signs of appendicitis were evident”, may influence the negative predictive value of the study and therefore alter post‐test probability far more than a report that simply states, “Appendix not identified and as such appendicitis cannot be excluded”.18 This can better inform clinical decision making, potentially reducing the incidence of negative appendectomies, or prevent a transfer to a tertiary centre.

A statistically significant (P < 0.001) difference was observed in responses regarding the maximum appendiceal diameter in children of different ages (5 and 13 years). This observation is in contrast with a previous review that reported appendix diameters are normally distributed but not age‐associated.28 Regardless of age, a maximum diameter of 6 mm was the most common response and corresponds with widely published traditional criteria.29 Respondents to the survey identified that they perceived the presence of inflamed peri‐appendiceal mesentery as the most indicative secondary sonographic criterion for acute appendicitis (Fig. 3). This subjective perception of sonographers agrees with published literature and is an important feature for sonographers to be aware of. The presence of echogenic mesentery is an important secondary sign of appendicitis, with strong positive predictive value even when the appendix cannot be identified, and assumes even greater importance in light of the low levels of confidence in visualising the appendix reported by respondents in this survey.30, 31

The study was limited by the distribution of invitations to participate in the survey to sonographers who were registered to watch a webinar on the topic of paediatric appendicitis. This may have introduced bias with webinar registrants potentially lacking confidence in these studies and seeking professional development, or conversely sonographers who are already focused on the topic may have registered to maintain their professional currency. The response rate of 18.35% of webinar registrants, representing 2.65% of all Australasian Sonographers, introduces non‐response bias and makes generalising the survey findings difficult, especially considering the diverse and heterogenous caseloads across sonographic practices. Whilst the survey was only active for a period of 7 days, possibly limiting the number of respondents, the planned sample size was exceeded. Responses regarding educational routes to qualification, and more details about their workplace would have potentially made respondents identifiable and fell outside the ethical approval for this survey. The inclusion of such information may have permitted more targeted and tailored approach to future education or quality improvement.

Conclusions

This survey has identified aspects of paediatric appendix ultrasound that are perceived weaknesses by sonographers performing these examinations. Poorer visualisation rates reported by sonographers not primarily working in paediatrics are consistent with published literature and suggest that children may undergo a less conclusive examination at non‐paediatric centres, potentially leading to treatment delays, unnecessary transfers, surgery or repeated/additional imaging.12, 32, 33 As many children may initially present in non‐tertiary paediatric centres with suspected appendicitis, this important finding provides an opportunity for improved practice in these centres.

The survey revealed a misconception that appendix diameter, and therefore the upper limit of normal as a diagnostic criterion changes with age. Sonographers should apply a range of 6–8 mm as the upper limit of normal, regardless of age, in conjunction with other sonographic criteria. Sonographer opinions on secondary sonographic criteria were in agreement with current literature. Awareness of criteria such as mesentery appearance and consideration of borderline diameters can reduce ambiguous findings,20 and can be integrated into worksheets or local protocols. Based on the findings of this survey, a workplace environment that overtly encourages staff to prolong examinations will result in improved visualisation rates and diagnostic confidence. Further investigation and discussion are warranted to determine how this can be incorporated into routine clinical practice for paediatric patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors received no financial or commercial support and declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the Australasian Sonographers Association for agreeing to facilitate this survey and distribute invitations to members. The webinar was sponsored by Philips Healthcare.

J Med Radiat Sci 65 (2018) 267–274

Funding Information

No funding information provided.

References

- 1. Reddan T, Corness J, Mengersen K, Harden F. Ultrasound of paediatric appendicitis and its secondary sonographic signs: Providing a more meaningful finding. J Med Radiat Sci 2016; 63: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mostbeck G, Adam EJ, Nielsen MB, et al. How to diagnose acute appendicitis: Ultrasound first. Insights Imaging 2016; 7: 255–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2012; 380: 499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marzuillo P. Appendicitis in children less than five years old: A challenge for the general practitioner. World J Clin Pediatr 2015; 4: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Podevin G, De Vries P, Lardy H, et al. An easy‐to‐follow algorithm to improve pre‐operative diagnosis for appendicitis in children. J Visc Surg 2017; 154: 245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sivit CJ. Controversies in emergency radiology: Acute appendicitis in children—the case for CT. Emerg Radiol 2004; 10: 238–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferguson M, Wright J, Ngo A‐V, Desoky S, Iyer R. Imaging of acute appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Infect Dis 2017; 12: 048–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quigley AJ, Stafrace S. Ultrasound assessment of acute appendicitis in paediatric patients: Methodology and pictorial overview of findings seen. Insights Imaging 2013; 4: 741–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alter SM, Walsh B, Lenehan PJ, Shih RD. Ultrasound for diagnosis of appendicitis in a community hospital emergency department has a high rate of nondiagnostic studies. J Emerg Med 2017; 52: 833–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee JH, Jeong YK, Park KB, Park JK, Jeong AK, Hwang JC. Operator‐dependent techniques for graded compression sonography to detect the appendix and diagnose acute appendicitis. Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184: 91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scrimgeour DSG, Driver CP, Stoner RS, King SK, Beasley SW. When does ultrasonography influence management in suspected appendicitis? ANZ J Surg 2014; 84: 331–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michailidou M, Sacco Casamassima MG, Karim O, et al. Diagnostic imaging for acute appendicitis: Interfacility differences in practice patterns. Pediatr Surg Int 2015; 31: 355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saito JM, Yan Y, Evashwick TW, Warner BW, Tarr PI. Use and accuracy of diagnostic imaging by hospital type in pediatric appendicitis. Pediatrics 2013; 131: e37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glass CC, Rangel SJ. Overview and diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016; 25: 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trout AT, Sanchez R, Ladino‐Torres MF, Pai DR, Strouse PJ. A critical evaluation of US for the diagnosis of pediatric acute appendicitis in a real‐life setting: How can we improve the diagnostic value of sonography? Pediatr Radiol 2012; 42: 813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cundy TP, Gent R, Frauenfelder C, Lukic L, Linke RJ, Goh DW. Benchmarking the value of ultrasound for acute appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg 2016; 51: 1939–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trout AT, Towbin AJ, Fierke SR, Zhang B, Larson DB. Appendiceal diameter as a predictor of appendicitis in children: Improved diagnosis with three diagnostic categories derived from a logistic predictive model. Eur Radiol 2015; 25: 2231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reddan T, Corness J, Mengersen K, Harden F. Sonographic diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children: A 3‐year retrospective. Sonography 2016; 3: 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Partain KN, Patel AU, Travers C, et al. Improving ultrasound for appendicitis through standardized reporting of secondary signs. J Pediatr Surg 2017; 52: 1273–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reddan T, Corness J, Harden F, Mengersen K. Improving the value of ultrasound in children with suspected appendicitis: A prospective study integrating secondary sonographic signs. Ultrasonography 2018; 10.14366/usg.17062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuan F, Necas M. Retrospective audit of patients presenting for ultrasound with suspicion of appendicitis. Australas J Ultrasound Med 2015; 18: 67–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Australian Sonographer Accreditation Registry . Sonographer Statistics, 2016. [Internet]. [cited 2018 April 2]. Available from: https://www.asar.com.au//about/sonographerstatistics

- 23. Sonographer Workforce Development Programme . Sonographer Clinical Supervision Training ‐ Issue 3, 2017. [Internet] [cited 2018 Apr 2]. p. 4. Available from: https://tas.health.nz/assets/SWS/Workforce/SWDP/SWDP-Newsletter-June-2017.pdf

- 24. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 2007; 42: 1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crabtree BF, Miller WL (eds). Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glass CC, Saito JM, Sidhwa F, et al. Diagnostic imaging practices for children with suspected appendicitis evaluated at definitive care hospitals and their associated referral centers. J Pediatr Surg 2016; 51: 912–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anderson KT, Putnam LR, Caldwell KM, et al. Imaging gently? Higher rates of computed tomography imaging for pediatric appendicitis in non–children's hospitals. Surgery 2017; 161: 1326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coyne SM, Zhang B, Trout AT. Does appendiceal diameter change with age? A sonographic study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203: 1120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kessler N, Cyteval C, Gallix B, et al. Appendicitis: Evaluation of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of US, Doppler US, and laboratory findings. Radiology 2004; 230: 472–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee MW, Kim YJ, Jeon HJ, Park SW, Jung SI, Yi JG. Sonography of acute right lower quadrant pain: Importance of increased intraabdominal fat echo. Am J Roentgenol 2009; 192: 174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reddan T, Corness J, Harden F, Mengersen K. Analysis of the predictive value of clinical and sonographic variables in children with suspected acute appendicitis using decision tree algorithms. Sonography 2018; doi: 10.1002/sono.12156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Menoch M, Simon HK, Hirsh D, et al. Imaging for suspected appendicitis: Variation between academic and private practice models. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016; 33: 147–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Otero HJ, Crowder L. Imaging utilization for the diagnosis of appendicitis in stand‐alone children's hospitals in the United States: Trends and costs. J Am Coll Radiol 2017; 14: 603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]