The metalloid extrusion systems are very important bacterial resistance mechanisms. Each of the previously reported ArsB, Acr3, ArsP, ArsJ, and MSF1 transport proteins conferred only inorganic or organic arsenic/antimony resistance. In contrast, ArsK confers resistance to several inorganic and organic trivalent arsenicals and antimonials. The identification of the novel efflux transporter ArsK enriches our understanding of bacterial resistance to trivalent arsenite [As(III)], antimonite [Sb(III)], trivalent roxarsone [Rox(III)], and methylarsenite [MAs(III)].

KEYWORDS: ArsK, ArsR2, arsenic efflux regulation, bacterial arsenic resistance, efflux transporter

ABSTRACT

Arsenic-resistant bacteria have evolved various efflux systems for arsenic resistance. Five arsenic efflux proteins, ArsB, Acr3, ArsP, ArsJ, and MSF1, have been reported. In this study, comprehensive analyses were performed to study the function of a putative major facilitator superfamily gene, arsK, and the regulation of arsK transcriptional expression in Agrobacterium tumefaciens GW4. We found that (i) arsK is located on an arsenic gene island in strain GW4. ArsK orthologs are widely distributed in arsenic-resistant bacteria and are phylogenetically divergent from the five reported arsenic efflux proteins, indicating that it may be a novel arsenic efflux transporter. (ii) Reporter gene assays showed that the expression of arsK was induced by arsenite [As(III)], antimonite [Sb(III)], trivalent roxarsone [Rox(III)], methylarsenite [MAs(III)], and arsenate [As(V)]. (iii) Heterologous expression of ArsK in an arsenic-hypersensitive Escherichia coli strain showed that ArsK was essential for resistance to As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) but not to As(V), dimethylarsenite [dimethyl-As(III)], or Cd(II). (iv) ArsK reduced the cellular accumulation of As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) but not to As(V) or dimethyl-As(III). (v) A putative arsenic regulator gene arsR2 was cotranscribed with arsK, and (vi) ArsR2 interacted with the arsR2-arsK promoter region without metalloids and was derepressed by As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III), indicating the repression activity of ArsR2 for the transcription of arsK. These results demonstrate that ArsK is a novel arsenic efflux protein for As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) and is regulated by ArsR2. Bacteria use the arsR2-arsK operon for resistance to several trivalent arsenicals or antimonials.

IMPORTANCE The metalloid extrusion systems are very important bacterial resistance mechanisms. Each of the previously reported ArsB, Acr3, ArsP, ArsJ, and MSF1 transport proteins conferred only inorganic or organic arsenic/antimony resistance. In contrast, ArsK confers resistance to several inorganic and organic trivalent arsenicals and antimonials. The identification of the novel efflux transporter ArsK enriches our understanding of bacterial resistance to trivalent arsenite [As(III)], antimonite [Sb(III)], trivalent roxarsone [Rox(III)], and methylarsenite [MAs(III)].

INTRODUCTION

Arsenic is a metalloid that is widely distributed in the environment (1). Arsenic exists in various forms, such as inorganic trivalent arsenite [As(III)], inorganic pentavalent arsenate [As(V)], organic pentavalent roxarsone [Rox(V)], methylarsenate [MAs(V)], and the trivalent forms Rox(III) and methylarsenite [MAs(III)] (2, 3). Microorganisms participate in the geochemical cycle of arsenic; as a result of continuous exposure to arsenic, most microorganisms have evolved pathways for arsenic resistance and detoxification (4, 5). Arsenic resistance genes are organized in the ars operon (6, 7). In general, the minimal ars operon contains a repressor encoded by the gene arsR, arsC encoding an As(V) reductase, and a gene encoding one of the As(III) efflux transporters (8, 9).

ArsR is a well-studied transcriptional repressor that has an autoregulatory function for metals or metalloids (10). When a metal or metalloid is taken up into the cells and binds ArsR, the conformation of ArsR changes, and the ArsR protein disassociates from the DNA, thereby enabling the DNA to be transcribed (10). The regulatory activities of four ArsR proteins, named ArsR1 to ArsR4, have been studied in Agrobacterium tumefaciens 5A, revealing a complex regulatory network among these repressors (8). The As(V) reductase ArsC catalyzes the reduction of As(V) to As(III) and is involved in bacterial As(V) resistance (9). In addition, the efflux transporter is the main resistance protein in the ars operon; it reduces the intracellular arsenic concentration via its efflux activity (11).

To date, five types of arsenic transporters (ArsB, Acr3, ArsJ, ArsP, and MSF1) have been found in various arsenic-resistant bacteria, and each confers resistance to different types of arsenic compounds (11–15). ArsB and Acr3 are both widespread determinants of As(III) efflux transporters in arsenic-resistant bacteria (16, 17). ArsB is classified in the ion transporter superfamily, and Acr3 is in the bile/arsenite/riboflavin transporter (BART) superfamily (18, 19). ArsB and Acr3 catalyze As(III) export coupled to electrochemical energy, and they can also couple with ArsA (ATPase encoded by arsA) to form primary As(III) transporter systems, which are much more efficient in extruding As(III) (11, 16). For resistance to As(V), As(V) is converted to As(III) by ArsC, and As(III) is then excreted by ArsB or Acr3 (9). Recently, a novel As(V) resistance protein, ArsJ, was identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa DK2 (12). ArsJ belongs to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), which is a ubiquitous transporter superfamily mediating the transport of various substrates (12, 20). Typically, arsJ is adjacent to the gene that encodes glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (12). When As(V) is taken up by phosphate transporters, GAPDH catalyzes the addition of As(V) to G3P to form 1-arseno-3-phosphoglyceric acid, and then ArsJ extrudes As(V) as the 1-arseno-3-phosphoglyceric acid form (12, 21). The MAs(III) efflux permease ArsP was identified in Campylobacter jejuni and shown to confer resistance to organic arsenicals Rox(III) and MAs(III) but not to inorganic arsenicals (22). Additionally, another MFS superfamily gene, mfs1, was found upstream of the mfs2-GAPDH genes in Halomonas sp. strain GFAJ-1 (15). MFS2 is highly homologous to ArsJ in P. aeruginosa DK2, and experimental results showed that the mfs1-mfs2-GAPDH gene operon functions in As(V) resistance but not in As(III) resistance. However, the individual function of mfs1 is still unclear (15).

Arsenic extrusion appears to be the most ubiquitous resistance pathway for arsenic-resistant bacteria (23), and genes in the ars operon are usually related to arsenic resistance. In a previous study, we isolated the highly arsenic-resistant bacterial strain A. tumefaciens GW4 from arsenic-enriched groundwater sediment (24). A putative MFS superfamily gene, which we named arsK, was found on the arsenic gene island of strain GW4. A phylogenetic tree analysis based on amino acid sequences showed that ArsK is different from the five known transporters (ArsB, Acr3, ArsJ, ArsP, and MFS1) (11, 12, 14, 15, 22). In this study, a novel arsenic efflux transporter, ArsK, was identified, revealing that bacteria can use one transport system for the resistance to several trivalent arsenicals or antimonials.

RESULTS

ArsK is widely distributed in arsenic-resistant bacteria.

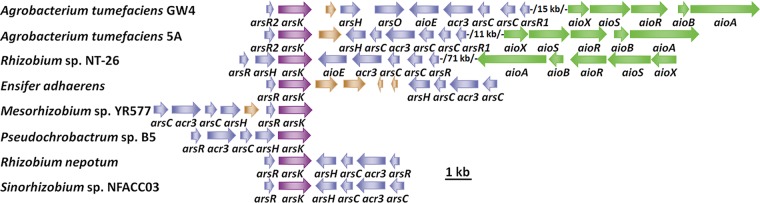

Arsenic is widely distributed in the environment, and most bacteria and archaea have ars operons (12). A genome analysis identified a putative gene, which we named arsK, in the arsenic gene island of A. tumefaciens GW4 (Fig. 1). The arsK homologs were also closely related to other arsenic-resistant bacteria, such as A. tumefaciens 5A, Rhizobium sp. strain NT-26, Ensifer adhaerens, Mesorhizobium sp. strain YR577, Pseudochrobactrum sp. strain B5, Rhizobium nepotum, and Sinorhizobium sp. strain NFACC03 (Fig. 1). The multiple sequence alignment results showed that three Cys residues (Cys97, Cys183, and Cys318) exist in ArsK from A. tumefaciens GW4 and that the Cys183 is conserved (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Besides, the ArsK orthologs were found in bacteria (including Cyanobacteria), but not in archaea, fungi, plants, or animals (data not shown), revealing that ArsK may be widely distributed in bacteria only or that the similar function proteins are much less homologous in archaea or eukaryotes.

FIG 1.

Putative arsK genes are conserved in bacterial ars operons. Representative ars operons containing arsK genes (purple) in As(III)-resistant bacteria. The accession numbers of bacterial genomes are NZ_AWGV00000000 (A. tumefaciens GW4), NZ_AGVZ00000000 (A. tumefaciens 5A), NZ_FO082821 (Rhizobium sp. NT-26), NZ_CP015882 (E. adhaerens), NZ_FPBI00000000 (Mesorhizobium sp. YR577), NZ_MOYL00000000 (Pseudochrobactrum sp. B5), NZ_JWJH00000000 (R. nepotum), and NZ_FMXF00000000 (Sinorhizobium sp. NFACC03).

The arsK gene product belongs to the MFS superfamily, and BLAST and conserved domains analyses showed that ArsK has the MFS_1 domain and the predicted arabinose efflux permease domain. MFS is an ancient and ubiquitous transporter superfamily, and members of this family can move substrates across membranes (20). Three major nomenclature and classification systems have been proposed for transporters to predict their substrates: the Pfam protein family database (http://pfam.xfam.org/clan/MFS), the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (http://slc.bioparadigms.org/), and the Transporter classification database (http://www.tcdb.org/) (20). However, the substrate transported by ArsK was not predicted by any of these three databases. These results indicated that ArsK may be involved in a common efflux mechanism in arsenic-resistant bacteria.

In addition, a genome analysis showed that there are four arsR genes in the genomes of strains A. tumefaciens GW4 and 5A (8), and they have been named arsR1 to arsR4 (8). The arsR2 is present upstream of arsK in strains GW4 and 5A (Fig. 1). A genome analysis showed that the ArsR2 (WP_020810055) from A. tumefaciens GW4 is closest to an ArsR of Agrobacterium sp. strain D14 (WP_059754788) and other Agrobacterium or Rhizobium strains. The ArsR2 amino acid sequence was also aligned with the ArsR orthologues in the NCBI GenBank database (see Fig. S2). Interestingly, the most closely related arsR2-like genes are all located adjacent to arsK, indicating that ArsR2 may regulate the expression of arsK. The multiple sequence alignment results showed that four Cys residues (Cys91, Cys92, Cys108, and Cys109) of ArsR2 are conserved in the related strains (Fig. S2), and the roles of the Cys residues can be investigated in the future.

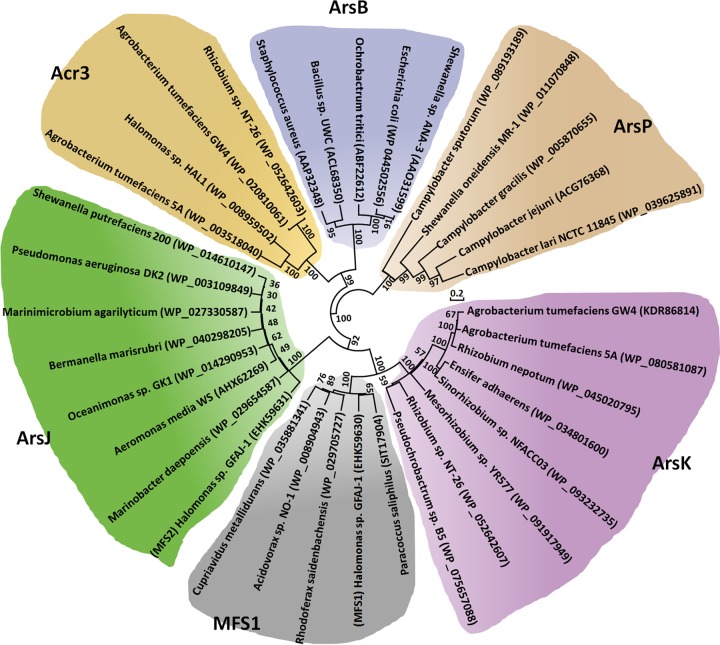

ArsK is phylogenetically divergent from other arsenic efflux proteins.

To associate the distribution of ArsK and the other arsenic efflux proteins with their phylogenetic affiliation, a phylogenetic tree based on their amino acid sequences was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA7 software (Fig. 2). ArsP sequences formed distinct groups, which was consistent with their different efflux functions related to organic arsenicals. In addition, because they both function in As(III) efflux, ArsB and Acr3 sequences formed distinct groups together, but they were clearly divergent from each other at the subgroup level (Fig. 2). ArsJ and MFS1 were reported to be different MFS superfamily proteins (12, 15), and ArsK also belongs to MFS superfamily according to a bioinformatics analysis. ArsK, ArsJ, and MFS1 sequences also formed distinct groups together, but they were clearly divergent from each other in the subgroups (Fig. 2). The multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis revealed that ArsK may be a novel arsenic efflux protein that is clearly divergent from ArsB, Acr3, ArsP, ArsJ, and MFS1.

FIG 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of ArsK amino acid sequences and other arsenic efflux proteins. The tree was produced by MEGA7. The bacterial names and the protein accession numbers are shown.

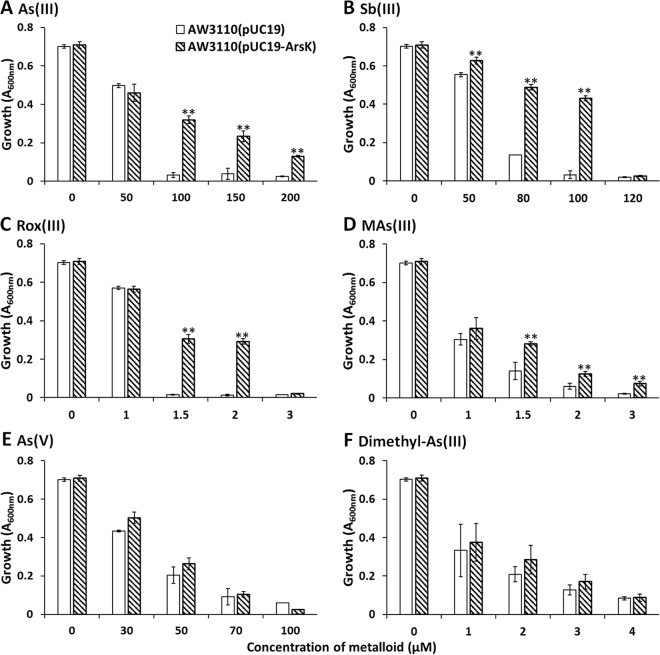

ArsK confers the resistance to As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III).

To investigate the function of the arsK gene in the ars operon, the arsK gene from strain GW4 was cloned into pUC19 under the control of the lac promoter, creating the plasmid pUC19-ArsK. ArsK was expressed in the arsenic-hypersensitive strain AW3110, and the resistance to arsenicals was assayed. Arsenicals exist in several different oxidation states and species, and the following arsenicals/antimonites were used to testify the function of ArsK: trivalent inorganic arsenical As(III), trivalent inorganic antimonite Sb(III), pentavalent inorganic arsenical As(V), and trivalent organic arsenicals Rox(III), MAs(III), and dimethyl-As(III). Due to the low toxicity of pentavalent inorganic antimonate Sb(V) and pentavalent organic arsenicals Rox(V), MAs(V), and dimethylarsenate [DMAs(V)], strain AW3110 grew well even with high concentrations of these substances (data not shown). Therefore, we did not test bacterial resistance to Sb(V), Rox(V), MAs(V), and DMAs(V).

As shown in Fig. 3A, strain AW3110 cells harboring the plasmid pUC19-ArsK were resistant up to 200 μM As(III). Strain AW3110(pUC19-ArsK) was resistant up to 100 μM Sb(III) (Fig. 3B). Strain AW3110(pUC19-ArsK) was resistant up to 2 μM Rox(III) (Fig. 3C). Strain AW3110(pUC19-ArsK) was resistant up to 3 μM MAs(III) (Fig. 3D). In contrast, cells expressing arsK had the same level of resistance to As(V) and dimethyl-As(III) as cells of the same strain harboring an empty pUC19 vector (Fig. 3). In addition to arsenicals, we also tested bacterial resistance to Cd(II), and ArsK did not confer resistance to Cd(II) (see Fig. S3).

FIG 3.

ArsK conferred resistance to As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III). Growth of E. coli strain AW3110 with plasmid pUC19 or pUC19-ArsK was measured with the addition of different amounts of As(III) (A), Sb(III) (B), Rox(III) (C), MAs(III) (D), As(V) (E), and dimethyl-As(III) (F). The data are the means from three replicates. **, P < 0.01.

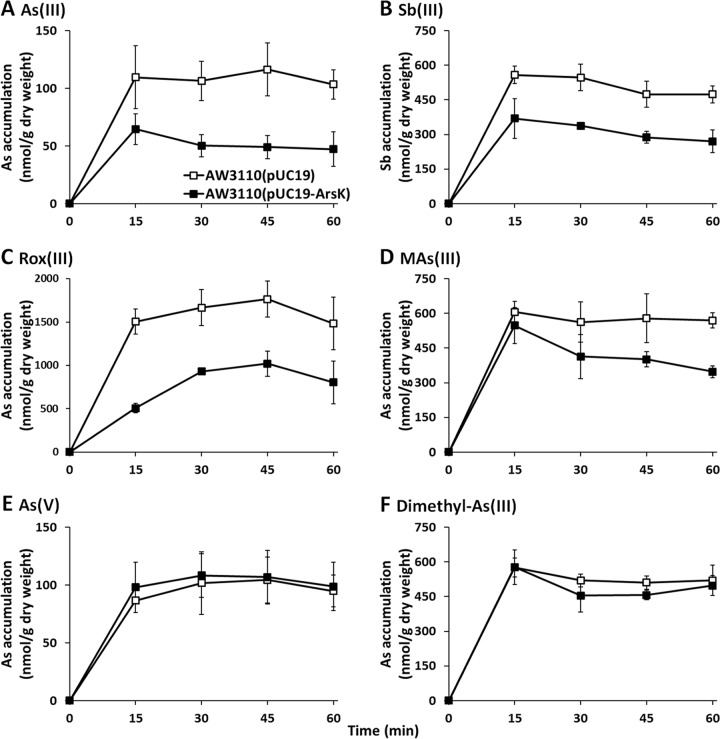

ArsK is essential for reducing cellular As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) accumulation.

To investigate the efflux function of ArsK, the effect of arsK expression on the accumulation of As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), MAs(III), As(V), and dimethyl-As(III) was examined (Fig. 4). Cells expressing arsK accumulated less As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) than cells lacking the arsK gene (Fig. 4). However, there was no significant difference in either As(V) or dimethyl-As(III) between the cells expressing arsK and those with empty vector only (Fig. 4E and F). These results indicated that ArsK can export As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) out of cells but has no effect on As(V) or dimethyl-As(III). In addition, compared to that in strain AW3110(pUC19), the intracellular accumulation of As(III) and Sb(III) in strain AW3110(pUC19-ArsK) was reduced by approximately 50% in 15 min, and so we speculated that As(III) and Sb(III) may be the best substrates of ArsK. Next, we performed a mutational analysis by site-directed mutagenesis of each of the three residues (Cys97, Cys183, and Cys318) and then examined the metalloid resistance of these mutant strains. However, the mutation of a single cysteine residue did not influence the function of ArsK (see Fig. S4).

FIG 4.

ArsK reduced the cellular accumulation of As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III). The levels of cellular As(III) (A), Sb(III) (B), Rox(III) (C), MAs(III) (D), As(V) (E), and dimethyl-As(III) (F) in E. coli strain AW3110 with plasmid pUC19 or pUC19-ArsK are shown. The data are the means from three replicates.

As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), MAs(III), and As(V) induce arsK expression.

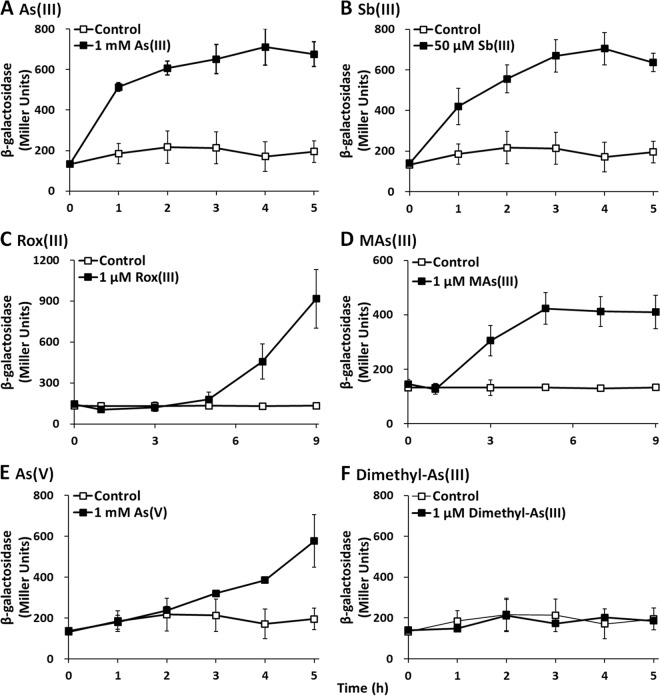

To further investigate the function of the arsK gene, lacZ reporter gene assays were performed. As expected, arsK::lacZ expression was significantly induced by As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III,) and MAs(III) in wild-type GW4 (Fig. 5), which was consistent with the resistance and efflux phenotype of ArsK to As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) (Fig. 3 and 4). Dimethyl-As(III) did not induce the expression of arsK::lacZ, consistent with the null resistance and efflux phenotype of ArsK related to dimethyl-As(III) (Fig. 3F and 4F). However, the expression of arsK::lacZ was also induced by As(V) (Fig. 5E), even though ArsK had no effect on the resistance or efflux of As(V) (Fig. 3E and 4E). We speculate that when As(V) was added to the medium, As(V) was reduced to As(III) by ArsC, and then As(III) induced the expression of arsK::lacZ. These results indicate that ArsK can be induced by As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III), which then extrudes As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) out of the cells.

FIG 5.

Expression of arsK was induced by As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), MAs(III), and As(V) in strain GW4. Strain GW4 containing the expression plasmid pLSP-arsR2-arsK was cultured in MMNH4 medium with or without the addition of As(III) (A), Sb(III) (B), Rox(III) (C), MAs(III) (D), As(V) (E), or dimethyl-As(III) (F). The data are the means from three replicates.

As(III) and Sb(III) induced the expression of arsK within 1 h, but MAs(III) induced expression after 1 h and Rox(III) induced expression only after 5 h. The delayed time of induction of MAs(III) and Rox(III) may be caused by the slow uptake of MAs(III) and Rox(III) into the cells. Currently, the uptake mechanisms of MAs(III) and Rox(III) remain unknown. In addition, the amounts of As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) needed for the induction of arsK expression varied from micromoles to millimoles (Fig. 5). The toxicity of Rox(III)/MAs(III), Sb(III), and As(III) is in a decreasing order, which appears to be correlated with the increasing substrate amount for induction (Fig. 5).

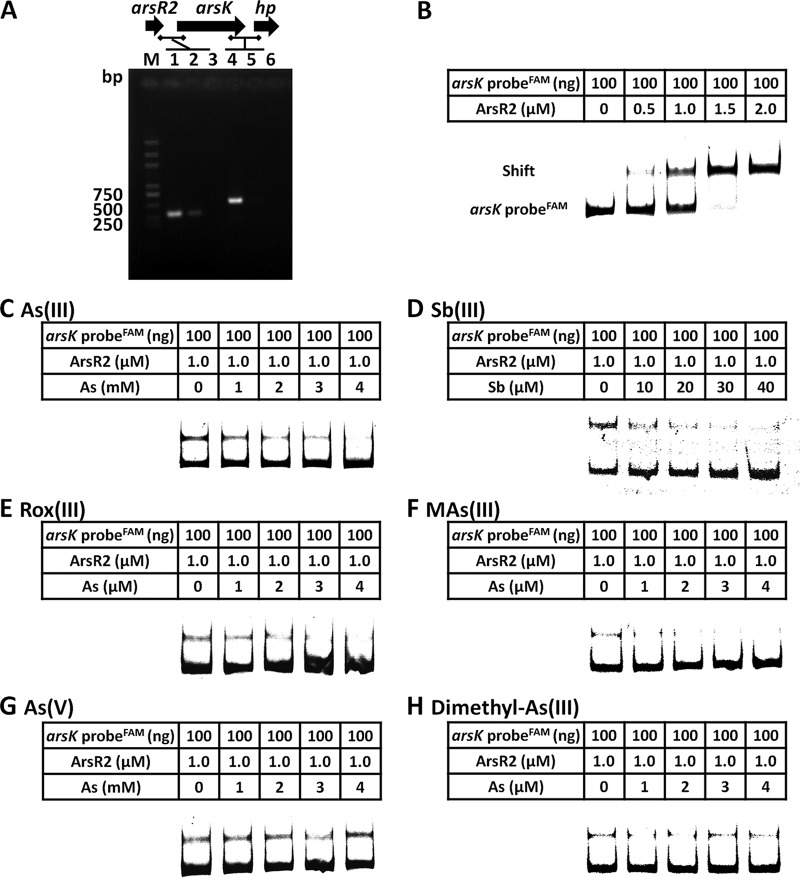

ArsR2 negatively regulates the expression of arsK.

Reverse transcriptase PCRs (RT-PCRs) showed that arsR2 and arsK are cotranscribed (Fig. 6A), revealing that arsR2 and arsK are in the same operon. To investigate the regulation of ArsR2 and the transcription expression of arsK, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed. As shown in Fig. 6B, an increase in ArsR2 protein in the binding assay resulted in electrophoretic shifts of the 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled arsR2-arsK promoter. These results indicated that ArsR2 interacted with the arsR2-arsK operon regulatory region. Furthermore, with the addition of increasing amounts of As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III), the electrophoretic shifts of the FAM-labeled arsR2-arsK promoter gradually disappeared (Fig. 6C to F). However, As(V) and dimethyl-As(III) had no effect on the interaction between ArsR2 and DNA (Fig. 6G and H). These results were in accordance with the resistance and efflux function of ArsK for As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) but not for As(V) or dimethyl-As(III) (Fig. 3 and 4). These results indicate that As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) bind ArsR2, affecting a change in the conformation of ArsR2. ArsR2 then regulates the expression of arsK, and the ArsK transporter excretes the relevant substance out of the cells. Besides, the derepression amounts of As(III), Sb(III), and Rox(III)/MAs(III) for EMSAs were in a decreasing order, which was correlated between the metalloid toxicities.

FIG 6.

ArsR2 negatively regulates the expression of arsK. (A) RT-PCR analysis illustrating the cotranscription of arsR2 and arsK. Total RNA was extracted from strain GW4 grown in MMNH4 medium with 1 mM As(III). M, molecular weight marker (DL 2000 plus). In lanes 1 and 4, total DNA was used as the template; in lanes 2 and 5, total RNA was used as the template; in lines 3 and 6, double-distilled water (ddH2O) was used as the template. The horizontal lines represent the locations of primers. (B) EMSAs. FAM-labeled arsR2-arsK probe interacted with ArsR2 protein. The amounts of DNA probes and ArsR2 are shown in the tables above each panel. Competition EMSAs including arsR2-arsK probe and ArsR2 protein with increasing amounts of As(III) (C), Sb(III) (D), Rox(III) (E), MAs(III) (F), As(V) (G), or dimethyl-As(III) (H). The amount of DNA probe was 100 ng, the amount of ArsR2 was 1.0 μM, and the amounts of each metalloid are shown in the tables above each panel.

DISCUSSION

The results from this study are consistent with the conclusion that ArsK is a novel membrane transporter mediating resistance to several organic and inorganic arsenicals or antimonials in A. tumefaciens GW4. This conclusion is supported by multiple lines of evidence. The expression of arsK in the arsenic-sensitive strain AW3110 resulted in increased resistance to As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) but had no effect on bacterial resistance to As(V) or dimethyl-As(III). ArsK reduced intracellular As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) accumulation in strain AW3110 but did not affect the concentration of As(V) or dimethyl-As(III). In addition, the expression of arsK was induced by As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III). These results indicate that ArsK functions in an efflux mechanism specific for As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III). A genome analysis showed that the arsK gene is widely distributed in various species, indicating that the apparent efflux function mediated by ArsK is a common resistance mechanism in arsenic-resistant bacteria. This finding enriches our knowledge of the various mechanisms of bacterial arsenic resistance.

A previous study analyzed approximately 2,500 genomes and over 700 putative membrane transporters encoded in the identified ars operons (23). Distinct clusters of ArsB, Acr3, and ArsP were found, whereas MFS proteins were divided into two subclusters (23). A phylogenetic analysis revealed that there are at least two types of MFS superfamily arsenic efflux transporters in arsenic-resistant bacteria. As expected, ArsJ and MFS1 belong to the MFS superfamily (12, 15), and now another MFS superfamily transporter, ArsK, has been identified in this study. Although these three transporters belong to the same MFS superfamily, multiple lines of evidence show conspicuous differences among ArsK, MFS1, and ArsJ. First, the phylogenetic affiliation of ArsK, ArsJ, and MFS1, based on their amino acid sequences, revealed that they formed distinct groups and were clearly divergent. Second, ArsJ and the mfs1-arsJ-GAPDH gene operon both confer resistance to As(V) but not to As(III) (12). However, ArsK confers resistance to As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) but not to As(V) or dimethyl-As(III). These results clearly reveal that ArsK is a novel arsenic transporter with different functions compared to those of ArsJ and MFS1 (21).

ArsK has very different characteristics compared to the other five types of arsenic efflux transporters, namely, ArsB, Acr3, ArsP, ArsJ, and MFS1. As a toxic metalloid element, arsenic exists in several different oxidation states and species (25, 26). Interestingly, arsenic efflux transporters show high specificity for oxidation states and inorganic/organic species. ArsB, Acr3, and ArsP only confer resistance to trivalent arsenicals, and ArsJ only confers resistance to pentavalent arsenicals (11, 12, 14, 22). ArsB, Acr3, and ArsJ only confer resistance to inorganic arsenicals, and ArsP only confers resistance to organic arsenicals (11, 12, 14, 22). Although ArsK only confers resistance to trivalent arsenicals, it confers resistance to both inorganic and organic forms. Therefore, ArsK is a new arsenic transporter that confers resistance to both inorganic and organic arsenicals. A genome analysis of eight arsenic-resistant bacteria showed that ArsK frequently coexists with Acr3 or ArsB. We speculate that ArsK independently confers organic arsenical resistance and confers inorganic arsenical resistance by cooperating with Acr3 or ArsB.

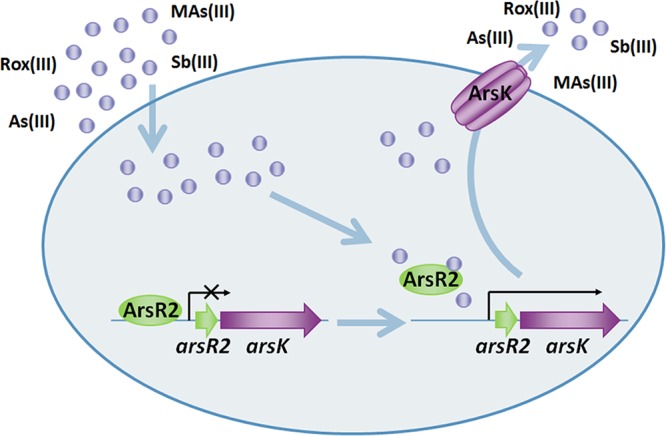

ArsK confers a novel arsenic resistance mechanism in A. tumefaciens GW4, and a model for the mechanism is presented in Fig. 7. ArsR2 is a repressor and interacts with the promoter region of the arsR2-arsK operon. When As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), or MAs(III) is taken up by cells, they can react with protein sulfhydryl groups, thereby causing cellular stress. As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), or MAs(III) interacts with ArsR2 and changes the protein conformation. Subsequently, the interaction between ArsR2 and the arsR2-arsK operon is weakened, which activates the expression of arsK. ArsK specifically extrudes As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) out of the cells and reduces the intracellular concentrations to avoid toxicity. In summary, an inorganic and organic arsenical resistance mechanism was identified in A. tumefaciens GW4. The arsR2-arsK operon gene arsK encodes a trivalent inorganic and organic arsenical efflux transporter, and the gene arsR2 encodes a regulator involved in the regulation of arsK transcriptional expression.

FIG 7.

Proposed roles of ArsK and ArsR2 in As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) transport and resistance. As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), or MAs(III) is taken up into the cells and then interacts with ArsR2. The altered conformation of ArsR2 releases its suppression of the arsR2-arsK operon, and then the arsK gene is expressed. ArsK specifically catalyzes the efflux of As(III), Sb(III), Rox(III), and MAs(III) out of the cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and reagents.

Escherichia coli AW3110, which is hypersensitive to As(III), was used (Table 1) (12). For most experiments, E. coli cultures bearing the indicated plasmids were grown aerobically in lysogeny broth (LB) or low-phosphate minimal mannitol (MMNH4) medium at 37°C supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Amp) or 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm), as indicated. MMNH4 medium contains 10 g of d-mannitol, 1 g of K2HPO4, 1 g of KH2PO4, 0.25 g Na2PO4, 0.01 g of FeCl3, 0.25 g of MgCl2, and 0.1 g of CaCl2 per liter. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm (27). All reagents were obtained from commercial sources. Rox(III), MAs(III), and dimethyl-As(III) were prepared by reduction of the pentavalent forms. Briefly, 0.2 mM arsenical was mixed with 27 mM Na2S2O3, 66 mM Na2S2O5, and 82 mM H2SO4, after which the pH was adjusted to 6 with NaOH (28).

TABLE 1.

The strains and plasmids used in this research

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. tumefaciens GW4 | Wild type, As(III)-oxidizing strain | 24 |

| E. coli DH5α | supE44 lacU169(φ80lacZΔM15) hrdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli S17-1 | F− RP4-2-Tc::Mu aphA::Tn7 recA λpir lysogen; Smr Tpr | Invitrogen |

| E. coli BL21 | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm me131 (DE3) pLysS (Cmr) | Invitrogen |

| E. coli AW3110 | ΔarsRBC::cam F-IN(rrn-rrnE) | 12 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Ampr, clone and expression vector | MiaoLingBio |

| pUC19-ArsK | pUC19 containing ArsK coding region | This study |

| pLSP-KT2lacZ | Kmr, oriV, lacZ-fusion vector used for lacZ fusion constructs | 8 |

| pLSP-arsR2-arsK | pLSP-KT2lacZ containing arsR2-arsK promoter | This study |

| pET-28(a+) | Kmr, His6 tag expression vector | Novagen |

| pET-ArsR2 | pET-28(a+) containing ArsR2 coding region | This study |

| pUC19-C97 | Cys97 site mutant of ArsK | This study |

| pUC19-C183 | Cys183 site mutant of ArsK | This study |

| pUC19-C318 | Cys318 site mutant of ArsK | This study |

Tc, tetracycline; Sm, streptomycin; Tp, trimethoprim; Cm, chloramphenicol; Km, kanamycin; Amp, ampicillin.

Plasmid construction.

For the expression of ArsK (accession number KDR86814.1) in E. coli, the arsK gene was cloned from A. tumefaciens GW4 genomic DNA into the plasmid pUC19 under the control of the lac promoter, creating plasmid pUC19-ArsK (Table 1) (12). The primers pUC19-ArsK-F and pUC19-ArsK-R were used for cloning arsK (Table 2). The PCR fragment was gel purified, digested with the indicated restriction enzymes, and ligated into the vector plasmid pUC19, which had been digested with HindIII and BamHI, generating plasmid pUC19-ArsK (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

The primers used in this research

| Primer | Descriptiona | Use |

|---|---|---|

| pUC19-ArsK-F | 5′-AAA AAGCTTGATGAGGGTGACGTCGTTG-3′ | Cloning for gene expression |

| pUC19-ArsK-R | 5′-AAA GGATCCGTCTCACTGTCAATGCCTC-3′ | |

| arsR2-arsK-F | 5′-GACATCCGACAGTCAGGG-3′ | Verification of cotranscription |

| arsR2-arsK-R | 5′-CACGGAGCCGATAGTCA-3′ | |

| arsK-hp-F | 5′-GGTGCCATCAGTGTCG-3′ | Verification of cotranscription |

| arsK-hp-R | 5′-CGCTGCAATCAGTCCC-3′ | |

| pLSP-arsK-F | 5′-AAA GAATTCGCCTTGACTTCGGTGAC-3′ | Cloning for lacZ reporter gene |

| pLSP-arsK-R | 5′-AAA GGATCCCCAACGCACGGACAAT-3′ | |

| pET28-arsK-F | 5′-AAA GGATCCATGGAAGAACGTCA-3′ | Overexpression of ArsK |

| pET28-arsK-R | 5′-AAA AAGCTTAGAGCCGATACGATGC-3′ | |

| arsK-EMSA-F | 5′-GTGTCTTGCCGTTTGC-3′ | Cloning for EMSA |

| arsK-EMSA-R | 5′-CCCTGACTGTCGGATGT-3′ | |

| C97-F | 5′-ACGCTCGCGATTGGCGCTTGGTCGC-3′ | Site mutant for ArsK |

| C97-R | 5′-GCCAATCGCGAGCGTCAGGGCCGCT-3′ | |

| C183-F | 5′-AACCTGTTTCTTGGTATGCCACTTC-3′ | Site mutant for ArsK |

| C183-R | 5′-ACCAAGAAACAGGTTCATTCCTGCA-3′ | |

| C318-F | 5′-GCCTTCGCCATCGGCCTTGGGCTCG-3′ | Site mutant for ArsK |

| C318-R | 5′-GCCGATGGCGAAGGCGACCGCACCC-3′ |

The underlined sequences denote the restriction enzyme sites.

Metalloid resistance assays.

For metalloid resistance assays in liquid media, AW3110 competent cells were transformed with the indicated plasmids. Cells were grown overnight with shaking at 37°C in LB with 100 μg/ml Amp and 50 μg/ml Cm. The overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold in MMNH4 medium with 100 μg/ml Amp and 50 μg/ml Cm containing various concentrations of metal(loid)s plus 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) and incubated at 37°C with shaking for another 48 h. The growth was estimated from the absorbance at 600 nm.

Cotranscription assays.

Overnight cultures were inoculated into 100 ml MMNH4 medium with the addition of 1 mM As(III) and incubated at 28°C with 100 rpm shaking. The samples used for RNA isolation were taken after a 16-h cultivation (mid-log phase). Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and incubated with RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa) at 37°C to remove genomic DNA, and the reaction was then terminated by the addition of 50 mM EDTA at 65°C for 10 min. After determining the concentration of RNA by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo), 1,000 ng total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with a RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo). The resulting cDNA was used as the template in the PCR system, and the primers arsR2-arsK-F and arsR2-arsK-R were used for testing the cotranscription of arsR2 and arsK genes (Table 2). The primers arsK-hp-F and arsK-hp-R were used for testing the cotranscription of arsK and hypothetical protein (HP) genes (Table 2) (29). The correct sizes of these two PCR products are 321 bp and 534 bp, respectively. The lack of the arsK-HP gene product with RNA indicated that the RT-PCRs were not contaminated with DNA.

Detection of the amount of cellular metalloids.

E. coli cells expressing ArsK and with the expression vector only were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 2 at 37°C in LB. The cells were harvested and suspended in buffer A (75 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 0.15 M KCl, and 1 mM MgSO4) (22). To initiate the transport reaction, 20 μM each metalloid was added to a 5-ml cell suspension. Aliquots (1 ml) from the cell suspension were withdrawn at the indicated times, washed twice at room temperature with 1 ml buffer A, and lysed using an ultrasonic cell disruptor (Ningbo Xinzhi Instruments). To monitor the metalloid concentration, we used high-performance liquid chromatography with hydride generation-atomic fluorescence spectroscopy (HPLC-HG-AFS) (Beijing Haiguang Instruments) (30).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The site-directed mutagenesis of ArsK was generated by the Fast Mutagenesis system (TransGen Biotech), which was used in our previous study (31). The primers C97-F/C97-R, C183-F/C183-R, and C318-F/C318-R were used for PCR and the construction of the mutational vectors (Table 2).

Reporter gene assays.

The reporter gene assays in this study were evaluated based on β-galactosidase activity. The promoter region of arsR2 was predicted by BPROM (http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=bprom&group=programs&subgroup=gfindb) and PCR amplified using primers pLSP-arsK-F and pLSP-arsK-R (Table 2). The promoter sequence (Table 2) was inserted into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pLSP-KT2lacZ, and the resulting plasmids were then introduced into strain GW4 via conjugation. Overnight cultures were inoculated (200 μl) into 100 ml MMNH4 with or without metalloids and incubated at 28°C with 100 rpm shaking. During the incubation, β-galactosidase assays were conducted as described previously (31, 32).

Plasmid construction, expression, and purification of ArsR2.

The arsR2 gene was PCR cloned as a BamHI-HindIII fragment using primers pET28-arsK-F and pET28-arsK-R (Table 2) into pET-28a(+), resulting in pET-28a-arsR2 (Table 1). BL21 cells containing pET-28a-arsR2 were induced at an OD600 of 0.4 by adding 0.3 mM IPTG and cultivated at 20°C for 12 h. They were then harvested by centrifugation (7,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and resuspended in borate saline buffer (pH 8.0) with 20 mM imidazole (33). Unbroken cells and fragments were collected by centrifugation at 7,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was mixed with 2 ml Ni-NTA His-Bind resin (7sea Biotech) and gently agitated at 4°C for 1 h to allow the polyhistidine-tagged protein to bind to the resin. The resin was washed with 10 ml borate saline buffer containing 60 mM imidazole and then eluted with 5 ml borate saline buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. Fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo) (31).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

The DNA fragment of the arsR2 regulatory region was amplified using the primers arsK-EMSA-F and arsK-EMSA-R (Table 2). The forward primer was labeled with the fluorophore 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). All reaction mixtures with or without metalloids were incubated at 28°C for 30 min in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10 mM MgCl2, 100 µg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA]). The binding solution was then loaded onto a 6% native PAGE gel. After 3 h of running at 80 V in 1× Tris-glycine-EDTA (TGE) buffer (120 mM Tris, 950 mM glycine, 5 mM EDTA), the gels were exposed in a phosphor imaging system (Fujifilm FLA-5100) (31).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31670108).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01842-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang Q, Qin D, Zhang S, Wang L, Li J, Rensing C, McDermott TR, Wang G. 2015. Fate of arsenate following arsenite oxidation in Agrobacterium tumefaciens GW4. Environ Microbiol 17:1926–1940. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oremland RS, Stolz JF. 2003. The ecology of arsenic. Science 300:939–944. doi: 10.1126/science.1081903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stolz JF, Basu P, Santini JM, Oremland RS. 2006. Arsenic and selenium in microbial metabolism. Annu Rev Microbiol 60:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai L, Liu G, Rensing C, Wang G. 2009. Genes involved in arsenic transformation and resistance associated with different levels of arsenic-contaminated soils. BMC Microbiol 9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlin DJ, Naujokas MF, Bradham KD, Cowden J, Heacock M, Henry HF, Lee JS, Thomas DJ, Thompson C, Tokar EJ, Waalkes MP, Birnbaum LS, Suk WA. 2015. Arsenic and environmental health: state of the science and future research opportunities. Environ Health Perspect 124:890–899. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1510209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Zhang L, Wang G. 2014. Genomic evidence reveals the extreme diversity and wide distribution of the arsenic-related genes in Burkholderiales. PLoS One 9:e92236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Wang J, Jing C. 2017. Comparative genomic analysis reveals organization, function and evolution of ars genes in Pantoea spp. Front Microbiol 8:471. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang YS, Brame K, Jetter J, Bothner BB, Wang G, Thiyagarajan S, McDermott TR. 2016. Regulatory activities of four ArsR proteins in Agrobacterium tumefaciens 5A. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:3471–3480. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00262-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Govarthanan M, Lee SM, Kamala-Kannan S, Oh BT. 2015. Characterization, real-time quantification and in silico modeling of arsenate reductase (arsC) genes in arsenic-resistant Herbaspirillum sp. GW103. Res Microbiol 166:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu C, Shi W, Rosen BP. 1996. The chromosomal arsR gene of Escherichia coli encodes a trans-acting metalloregulatory protein. J Biol Chem 271:2427–2432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng YL, Liu Z, Rosen BP. 2004. As(III) and Sb(III) uptake by GlpF and efflux by ArsB in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 279:18334–18441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Yoshinaga M, Garbinski LD, Rosen BP. 2016. Synergistic interaction of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and ArsJ, a novel organoarsenical efflux permease, confers arsenate resistance. Mol Microbiol 100:945–953. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen Z, Luangtongkum T, Qiang Z, Jeon B, Wang L, Zhang Q. 2014. Identification of a novel membrane transporter mediating resistance to organic arsenic in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2021–2029. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02137-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wysocki R, Bobrowicz P, Ulaszewski S. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACR3 gene encodes a putative membrane protein involved in arsenite transport. J Biol Chem 272:30061–30066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu S, Wang L, Gan R, Tong T, Bian H, Li Z, Du S, Deng Z, Chen S. 2018. Signature arsenic detoxification pathways in Halomonas sp. strain GFAJ-1. mBio 9:e00515-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00515-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tisa LS, Rosen BP. 1990. Molecular characterization of an anion pump. The ArsB protein is the membrane anchor for the ArsA protein. J Biol Chem 265:190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Li M, Huang Y, Rensing C, Wang G. 2013. In silico analysis of bacterial arsenic islands reveals remarkable synteny and functional relatedness between arsenate and phosphate. Front Microbiol 4:347. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansour NM, Sawhney M, Tamang DG, Vogl C, Saier MH Jr.. 2007. The bile/arsenite/riboflavin transporter (BART) superfamily. FEBS J 274:612–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prakash S, Cooper G, Singhi S, Saier MH. 2003. The ion transporter superfamily. Biochim Biophys Acta 1618:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan N. 2015. Structural biology of the major facilitator superfamily transporters. Annu Rev Biophys 44:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-033901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao FJ. 2016. A novel pathway of arsenate detoxification. Mol Microbiol 100:928–930. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Madegowda M, Bhattacharjee H, Rosen BP. 2015. ArsP: a methylarsenite efflux permease. Mol Microbiol 98:625–635. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Wu S, Lilley RM, Zhang R. 2015. The diversity of membrane transporters encoded in bacterial arsenic-resistance operons. PeerJ 3:e943. doi: 10.7717/peerj.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan H, Su C, Wang Y, Yao J, Zhao K, Wang Y, Wang G. 2008. Sedimentary arsenite-oxidizing and arsenate-reducing bacteria associated with high arsenic groundwater from Shanyin, Northwestern China. J Appl Microbiol 105:529–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Lado L, Sun G, Berg M, Zhang Q, Xue H, Zheng Q, Johnson CA. 2013. Groundwater arsenic contamination throughout China. Science 341:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1237484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen BP, Ajees AA, McDermott TR. 2011. Life and death with arsenic. Arsenic life: an analysis of the recent report "A bacterium that can grow by using arsenic instead of phosphorus". Bioessays 33:350–357. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Han Y, Shi K, Fan X, Wang L, Li M, Wang G. 2017. An oxidoreductase AioE is responsible for bacterial arsenite oxidation and resistance. Sci Rep 7:41536. doi: 10.1038/srep41536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshinaga M, Rosen BP. 2014. A C·As lyase for degradation of environmental organoarsenical herbicides and animal husbandry growth promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:7701–7706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403057111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi K, Wang Q, Fan X, Wang G. 2018. Proteomics and genetic analyses reveal the effects of arsenite oxidation on metabolic pathways and the roles of AioR in Agrobacterium tumefaciens GW4. Environ Pollut 235:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen F, Cao Y, Wei S, Li Y, Li X, Wang Q, Wang G. 2015. Regulation of arsenite oxidation by the phosphate two-component system PhoBR in Halomonas sp. HAL1. Front Microbiol 6:923. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi K, Fan X, Qiao Z, Han Y, McDermott TR, Wang Q, Wang G. 2017. Arsenite oxidation regulator AioR regulates bacterial chemotaxis towards arsenite in Agrobacterium tumefaciens GW4. Sci Rep 7:43252. doi: 10.1038/srep43252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang YS, Heinemann J, Bothner B, Rensing C, McDermott TR. 2012. Integrated co-regulation of bacterial arsenic and phosphorus metabolisms. Environ Microbiol 14:3097–3109. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou Z, Du D, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Niu G, Tan H. 2014. A gamma-butyrolactone-sensing activator/repressor, JadR3, controls a regulatory mini-network for jadomycin biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol 94:490–505. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.