This study demonstrates that foodborne pathogens can be established in mixed-species biofilms and that this can protect them from biocide action. The protection is not due to specific characteristics of the pathogen, here S. aureus and L. monocytogenes, but likely caused by specific members or associations in the mixed-species biofilm. Biocide treatment and resistance are a challenge for many industries, and biocide efficacy should be tested on microorganisms growing in biofilms, preferably mixed systems, mimicking the application environment.

KEYWORDS: Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, pathogen, mixed-species biofilm, processing environment, biocide

ABSTRACT

In nature and man-made environments, microorganisms reside in mixed-species biofilms, in which the growth and metabolism of an organism are different from these behaviors in single-species biofilms. Pathogenic microorganisms may be protected against adverse treatments in mixed-species biofilms, leading to health risk for humans. Here, we developed two mixed five-species biofilms that included one or the other of the foodborne pathogens Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. The five species, including the pathogen, were isolated from a single food-processing environmental sample, thus mimicking the environmental community. In mature mixed five-species biofilms on stainless steel, the two pathogens remained at a constant level of ∼105 CFU/cm2. The mixed five-species biofilms as well as the pathogens in monospecies biofilms were exposed to biocides to determine any pathogen-protective effect of the mixed biofilm. Both pathogens and their associate microbial communities were reduced by peracetic acid treatments. S. aureus decreased by 4.6 log cycles in monospecies biofilms, but the pathogen was protected in the five-species biofilm and decreased by only 1.1 log cycles. Sessile cells of L. monocytogenes were affected to the same extent when in a monobiofilm or as a member of the mixed-species biofilm, decreasing by 3 log cycles when exposed to 0.0375% peracetic acid. When the pathogen was exchanged in each associated microbial community, S. aureus was eradicated, while there was no significant effect of the biocide on L. monocytogenes or the mixed community. This indicates that particular members or associations in the community offered the protective effect. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms of biocide protection and to identify the species playing the protective role in microbial communities of biofilms.

IMPORTANCE This study demonstrates that foodborne pathogens can be established in mixed-species biofilms and that this can protect them from biocide action. The protection is not due to specific characteristics of the pathogen, here S. aureus and L. monocytogenes, but likely caused by specific members or associations in the mixed-species biofilm. Biocide treatment and resistance are a challenge for many industries, and biocide efficacy should be tested on microorganisms growing in biofilms, preferably mixed systems, mimicking the application environment.

INTRODUCTION

To prevent contamination, infection, or foodborne disease in the clinical or food producing sector, antimicrobials, detergents, and biocides are used to inactivate or eradicate microorganisms (1, 2). Most guidelines for biocides include testing of efficiency on planktonic pure cultures of microorganisms, but little is known about their efficacy on microbial biofilms (3). Moreover, most microorganisms live in complex biofilms (4) composed of multiple species (5, 6). In biofilms, microorganisms can cooperate (7) and protect themselves from adverse environmental conditions. Thus, several studies have reported that sessile cells can be up to 1,000-fold more resistant than cells in a planktonic state (8–10).

Biofilm formation and resistance to biocide treatment have been studied and recognized as important factors that contribute to the survival and persistence of microbial contamination in drinking water (11) and in oral hygiene (12, 13). The food processing environment is also believed to provide conditions for biofilm development, including polymicrobial biofilms. Although many studies have focused on monoculture systems, it is being recognized that biofilms are predominantly polymicrobial (14, 15). The behavior of microorganisms in a mixed biofilm differs from the behavior of a monospecies biofilm (16, 17), and for instance, resistance to antimicrobials can be increased in the mixed system (18). The complete picture on mechanisms involved in resistance has not been fully unraveled, but some of the reasons for biofilm resistance to antimicrobial compounds are proposed to reside in the specific architecture, the decreased metabolic activity, or the presence of extracellular matrix (19). In addition, conditions in a processing environment, such as temperature, have been shown to decrease biocide efficiency on biofilms (20, 21).

A major concern raised by the above-mentioned observations is whether pathogenic microorganisms can be protected in mixed biofilms (22, 23). It has been demonstrated that Bacillus subtilis, resistant to peracetic acid exposure, was able to protect Staphylococcus aureus, usually sensitive to this disinfectant, in a dual-species biofilm (24). Indeed, biofilms in food processing environments have been shown to contribute to foodborne pathogen survival in cleaning and disinfection treatments, leading to persistence of those microorganisms (25).

Listeria monocytogenes is a ubiquitous microorganism, and it can cause serious foodborne disease. This psychrotrophic bacterium has been found in different food products that can lead to listeriosis after ingestion (26). L. monocytogenes attaches to surfaces, but its ability to form biofilms is controversial (27, 28). Nevertheless, clones of L. monocytogenes can survive and persist in niches of processing environments for several years despite cleaning and disinfection procedures (29, 30).

S. aureus is one of the most common causative agents of food poisoning and is also involved in nosocomial infections (31). S. aureus can form biofilms on different abiotic surfaces found in food processing environments such as glass, stainless steel, polypropylene, and polystyrene (32). The food processing environment can also provide suitable conditions for S. aureus biofilm production, which is enhanced by suboptimal growth temperature as well as glucose and sodium chloride availability (33). Furthermore, increasing resistance of S. aureus in biofilms toward disinfectants in processing environments has been reported in several studies (21).

Both pathogens are commonly found in food processing environments, including dairy, meat, and seafood worldwide (34, 35), and are reported to be common contaminating agents in the Brazilian dairy industry (36–38). Furthermore, several studies have highlighted that the two pathogens are often found in polymicrobial communities (6, 23, 39, 40).

The effectiveness of biocides depends on the composition of the food soil (i.e., organic matter remaining after insufficient surface cleaning) and the temperature (3) as well as the antimicrobial used and the surface type (41), the treatment exposure time, and the procedure used (10). However, the biofilm mode of growth is also important for effectiveness of biocides. Therefore, the control of biofilm is important for public health in clinical or industrial environments and there is a need for understanding the mechanisms involved in the enhanced pathogen resistance seen in mixed-species biofilm. To date, most studies have focused on monospecies or dual-species biofilms; however, no studies have investigated biocide efficiency using more-complex biofilm communities.

The purpose of this study was to determine if a “reproducible” mixed-species biofilm model could be established by cocultivating a pathogen with an associated microbial community isolated from the food processing sector. Specifically, we sought to determine if foodborne pathogens, such as S. aureus and L. monocytogenes, could establish themselves in such a mixed community and how the presence of this more natural scenario affected their sensitivity to commonly used biocides.

RESULTS

Identification of the community members.

We isolated L. monocytogenes and S. aureus from two separate samples in Brazilian dairies (42, 43) and subsequently, from each of these samples, isolated four different microbial strains at random (Table 1). The sample containing L. monocytogenes BZ001 (42) also contained Klebsiella sp. (BZ002), Escherichia coli (BZ003), Comamonas sp. (BZ004), and Acinetobacter sp. (BZ006). The sample containing S. aureus BZ012 (43) also contained Aeromonas spp. (BZ013), Lactococcus lactis (BZ014), Candida tropicalis (BZ017), and Lactobacillus sp. (BZ018).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in the present study

| Pathogen/community | Background microorganisms | Name of strain | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes | BZ001 | 42 | |

| comLm | Klebsiella spp. | BZ002 | This study |

| comLm | E. coli | BZ003 | This study |

| comLm | Comamonas spp. | BZ004 | This study |

| comLm | Acinetobacter spp. | BZ006 | This study |

| S. aureus | BZ012 | 43 | |

| S. aureus | Sa30 | 43 | |

| comSa | Aeromonas sp. | BZ013 | This study |

| comSa | Lactococcus lactis | BZ014 | This study |

| comSa | Candida tropicalis | BZ017 | This study |

| comSa | Lactobacillus sp. | BZ018 | This study |

Establishment of the pathogen in a dual-species biofilm.

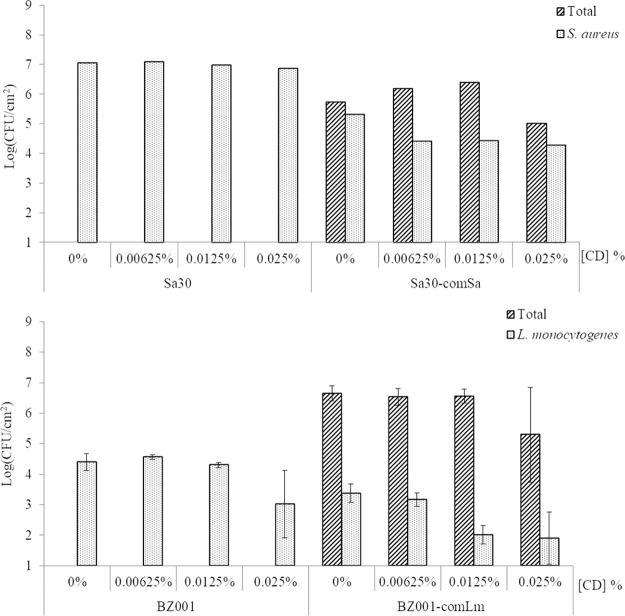

S. aureus and L. monocytogenes were individually grown in dual-species biofilms with each of their community members (Fig. 1). The total sessile cell counts ranged from 3.5 × 106 to 3.8 × 107 CFU/cm2, while L. monocytogenes counts ranged between 1.8 × 105 and 1.3 × 107 CFU/cm2 in the dual-species biofilms. The total sessile cell count for the S. aureus communities ranged from 3.9 × 106 to 9.2 × 107 CFU/cm2 and was between 1.0 × 106 and 6.9 × 107 CFU/cm2 for the pathogen in the dual-species biofilms.

FIG 1.

Quantification of viable sessile cells in dual-species biofilms. Each pathogen, L. monocytogenes (BZ001) (top) or S. aureus (BZ012) (bottom), was grown as a monofilm or dual biofilm developed on SSCs with each of the associated community members. At least three biological replicates for L. monocytogenes and only duplicates for S. aureus were done.

Stable concentration of the pathogen in mixed five-species biofilm.

In the S. aureus mixed five-species biofilm, the total sessile count was 1.9 × 106 CFU/cm2 and the S. aureus sessile cell count was 4.5 × 105 CFU/cm2 (Fig. 2). The two different S. aureus isolates, BZ012 and Sa30, behaved very similarly in the mixed biofilm (data not shown). The total sessile cell count of the L. monocytogenes community was 1.8 × 107 CFU/cm2, and the count was 2.3 × 105 CFU/cm2 for L. monocytogenes sessile cells. All members of the five-species communities remained in the mature biofilm based on the recovery of all members' colony morphology on brain heart infusion (BHI) plates and by PCR detection for the S. aureus community (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Sessile cell counts of mono- and mixed five-species mature biofilms. Pathogens were L. monocytogenes (BZ001) or S. aureus (Sa30). The mature biofilms were a 25-h biofilm and a 72-h biofilm for the S. aureus community and the L. monocytogenes community, respectively. Pathogen cell count was assessed on Baird Parker agar for S. aureus and Oxford agar for L. monocytogenes. Total community cell count was assessed on BHI agar. Error bars represent the standard deviations for three biological replicates.

MICs of the biocides.

The MIC of peracetic acid for the two pathogens was 0.075% (1/4 of the concentration used in the dairy) when grown as a monoculture. MICs of peracetic acid against the five species grown together were 0.075% for the mixed culture containing L. monocytogenes (comLm) and 0.015% (1/20 of the concentration used in the dairy) for the mixed culture containing S. aureus. The individual MICs of peracetic acid against the associated microorganisms were 0.075% for the four associated microbial community members of comLm (BZ002, BZ003, BZ004, BZ006), 0.075% for BZ0013, 0.15% for BZ014 and BZ017, and 0.3% for BZ018.

The chlorhexidine digluconate MICs were 0.000390625% for L. monocytogenes and 0.0001953125% for S. aureus. The MIC of chlorhexidine digluconate against the five species of the L. monocytogenes-associated microbial community grown together was 0.003125%. The MIC for chlorhexidine digluconate was not determined for the five-species culture containing S. aureus because it was above 0.025%, which was the maximum concentration that could be tested without precipitation.

The full community composition influences biocide susceptibility.

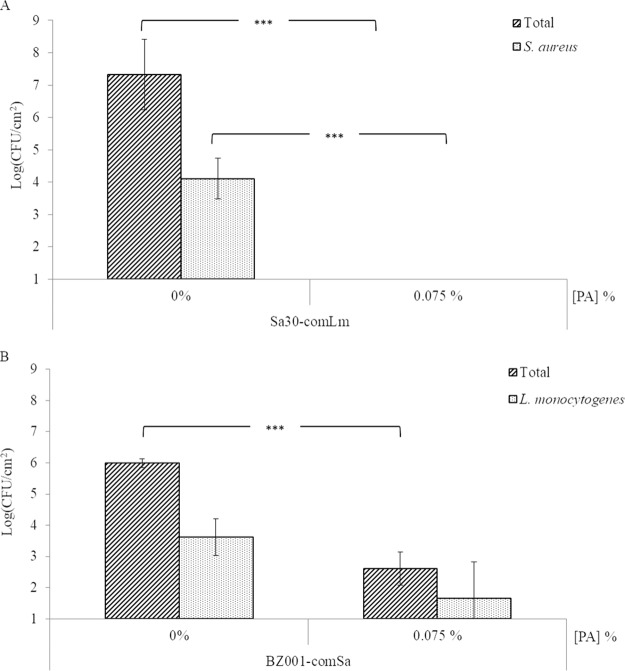

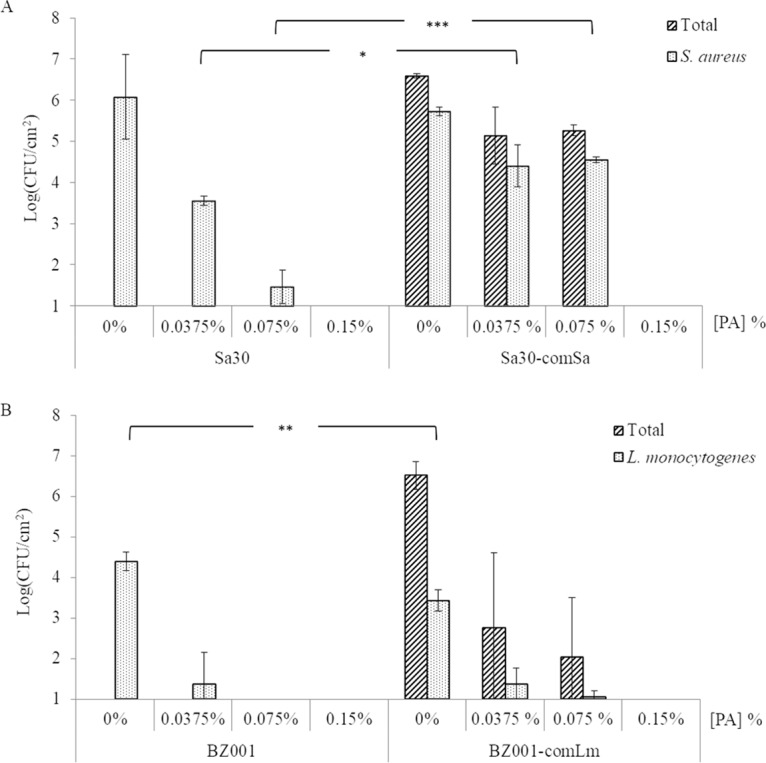

Using the monobiofilm and mixed five-species biofilm model described above, biocide susceptibility was assessed. The exposure of a monobiofilm of S. aureus to increasing concentrations of peracetic acid led to a sequential decrease of the S. aureus sessile cell survival (Fig. 3A) of 2.5 log between the exposures at 0% and 0.0375% and then a 2.1-log reduction between 0.0375 and 0.075% (MIC value). When S. aureus was part of a mixed-community biofilm, 0.075% peracetic acid caused only a 1.1-log reduction of the S. aureus sessile cells. This is a significantly (P = 0.0002) lower reduction than seen for the monobiofilm (4.6 log). Increasing the peracetic acid concentration from 0.075% to 0.15% fully eradicated S. aureus sessile cells from an initial concentration of 4.7 × 106 CFU/cm2 in a monobiofilm and 5.5 × 105 CFU/cm2 in a mixed five-species biofilm (Fig. 3A). At the same time, no associate microbial community member sessile cells were recovered when the mixed five-species biofilm was exposed to 0.15% peracetic acid (Fig. 3A), meaning that less than 10 CFU/cm2 was on the stainless steel coupon (SSC) if not all eradicated.

FIG 3.

Survival of sessile cells in biofilms formed on SSCs after peracetic acid exposure. For each pathogen, S. aureus (Sa30) (A) or L. monocytogenes (BZ001) (B), mono- and mixed five-species biofilms were developed on SSCs as mature biofilms before being treated with different concentrations of peracetic acid (PA) for 20 min. Sa30, monobiofilm of S. aureus; Sa30-comSa, mixed five-species biofilms containing Sa30; BZ001, monobiofilm of L. monocytogenes; BZ001-comLm, mixed five-species biofilms containing BZ001. Results are presented as the means for biological triplicates.

Treatment of an L. monocytogenes monobiofilm with 0.0375% peracetic acid caused a 3-log reduction of the sessile cells (Fig. 3B). The same treatment of the mixed five-species biofilm led to a 2-log reduction of L. monocytogenes sessile cells, while the total sessile cells decreased by 3.7 log. When exposed to a higher concentration of peracetic acid, e.g., 0.075%, no viable L. monocytogenes sessile cells were recovered from a monobiofilm. The total sessile cells and the L. monocytogenes sessile cells decreased by 0.8 log and 0.3 log, respectively, in the mixed five-species biofilm treated with 0.075% peracetic acid compared to treatment with 0.0375% (Fig. 3B). No viable sessile cells were recovered when L. monocytogenes was grown as a monospecies biofilm or in a mixed five-species biofilm treated with 0.15% peracetic acid (2-fold higher than the MIC) (Fig. 3B).

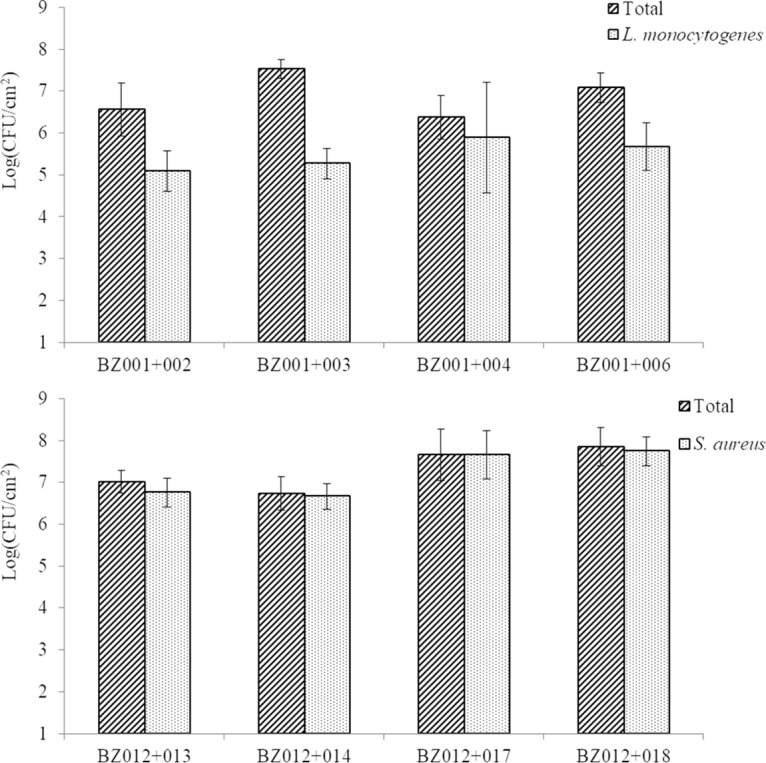

No effect of chlorhexidine digluconate was observed.

In order to assess susceptibility to other biocides used in the processing environment, the effect of chlorhexidine digluconate was also evaluated (Fig. 4). No effect of chlorhexidine treatment was observed on S. aureus grown as a monobiofilm or as part of a mixed five-species biofilm (Fig. 4, top).

FIG 4.

Survival of sessile cells in biofilms formed on SSCs after treatment with different concentrations of chlorhexidine digluconate for 20 min. For each pathogen, S. aureus (Sa30) (top) or L. monocytogenes (BZ001) (bottom), mono- and mixed five-species biofilms were developed on SSCs as mature biofilms before treatment. Sa30, monobiofilm of S. aureus; Sa30-comSa, mixed five-species biofilms containing Sa30; BZ001, monobiofilm of L. monocytogenes; BZ001-comLm, mixed five-species biofilms containing BZ001. Results are presented as the means of biological triplicates for L. monocytogenes (bottom) and only one biological replicate for S. aureus (top).

There was no impact of chlorhexidine digluconate treatment on L. monocytogenes for concentrations below 0.0125% (Fig. 4, bottom) whenever the pathogen was grown as a monobiofilm or as part of a mixed five-species biofilm. L. monocytogenes sessile cell counts remained steady in a monobiofilm with 104 CFU/cm2 when treated with a concentration of chlorhexidine digluconate below 0.0125%, while it decreased from 1.6 × 103 CFU/cm2 to 1.2 × 102 CFU/cm2 in a mixed five-species biofilm (Fig. 4, bottom). This 1.2-log reduction was observed in the monobiofilm when the sessile cells were exposed from 0.0125% to 0.25% chlorhexidine digluconate. The concentration of the total sessile cells, being 4 × 106 CFU/cm2, did not change when exposed to 0.00625% and 0.0125% but decreased 1.3 log when exposed to 0.025% of chlorhexidine digluconate. Concentrations higher than 0.025% were not investigated due to technical limitations, as the chlorhexidine digluconate precipitated.

The community rather the individual influences peracetic acid susceptibility.

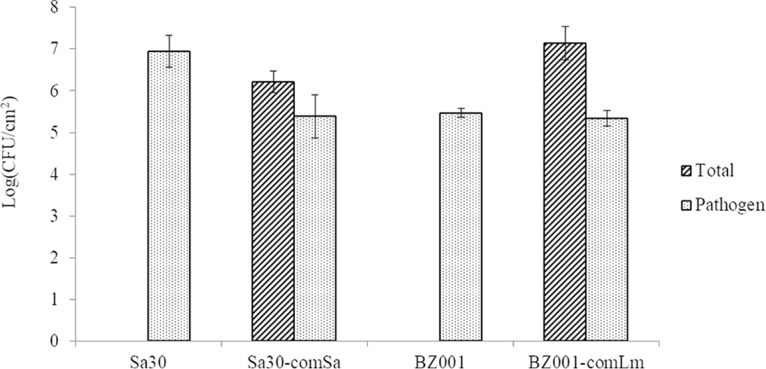

To determine if the altered sensitivity to peracetic acid in a mixed-species biofilm was due to the associated microbial community or to the pathogen, we interchanged the pathogens and the communities. When S. aureus was grown with the L. monocytogenes community members, on the SSC not treated with peracetic acid, the total sessile cells count was 1.3 × 108 CFU/cm2 and the S. aureus sessile cells count was 2.5 × 104 CFU/cm2 (Fig. 5A). No cells were recovered after treatment with 0.075% peracetic acid, indicating that the total sessile cells decreased by at least 6.3 log (P = 0.001) and the pathogen sessile cells decreased by at least 3.1 log (P < 0.001). When L. monocytogenes was grown with the S. aureus community members, the overall biofilm production on SSC did not change (Fig. 3B and 5B). Treatment with 0.075% peracetic acid led to a reduction of the total sessile cells by 3.4 log (P < 0.001) and a reduction of the L. monocytogenes sessile cells by 1.9 log (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Survival of sessile cells in mixed-species biofilm after 20 min with 0.075% peracetic acid (PA) treatment. Each pathogen, S. aureus (Sa30) (A) or L. monocytogenes (BZ001) (B), was grown as a mixed five-species biofilm developed on SSCs with the other pathogen community members, i.e., BZ001 associated with comSa and Sa30 associated with comLm. Sa30-comLm, mixed five-species biofilm containing Sa30; BZ001-com, mixed five-species biofilm containing BZ001. Results are presented as the means for biological triplicates.

DISCUSSION

In environments, either natural, clinical, or industrial, microorganisms live mainly in biofilms that are well-structured communities and composed mostly of more than one microbial species (5, 6). However, in a natural or man-made environment, the quantity and diversity of present species raise the complexity underlying the behavior of the biofilms compared to their single-species growth behavior (7). Pathogenic microorganisms can also form biofilms or inhabit biofilms, and this can cause problems for human health, especially if biocide treatment is not fully effective. Also, survival of microorganisms after biocide exposure is one of the results of behavior modification. To date, most biofilm studies focusing on their mechanistic properties or antimicrobial resistance have been done on monospecies biofilms, which do not reflect the complexity reached in a mixed community. Recently, some studies on mixed biofilms have also been conducted, but they have been limited in species diversity (44–47) without focusing on a specific pathogenic organism.

In this study, we set up and studied two mixed five-species biofilms containing a pathogenic bacterium. The ability of some strains to form biofilms fluctuated, with some dual-species sets of organisms showing better ability to form biofilm than others depending on the strain association. Norwood and Gilmour (48) have shown that Pseudomonas fragi and Staphylococcus xylosus were the predominant species in biofilms with L. monocytogenes, and they described, as have other studies, that some microorganisms can take over in mixed-species biofilms. However, no strains were inhibited in our study. Both in the dual-species and the mixed five-species biofilms, all strains remained in the mature biofilm, including both pathogens. A previous study on mixed biofilms composed of L. monocytogenes and Enterococcus spp. found that growth at 25°C on stainless steel gave the highest biofilm cell counts (44), supporting the temperature selection that was used in this present study. Furthermore, the mixed five-species biofilm model here was stable and reproducible, leading to a biofilm tool that can be used to study the behavior of a pathogen in mixed biofilms and to unravel the mechanisms involved in survival or persistence despite application of antimicrobial compounds such as biocides.

L. monocytogenes is commonly described as a non-/weak monolayered biofilm producer (23, 49) but can colonize and persist in mixed-species biofilms (23) as also found in the present study. Some authors have described that L. monocytogenes was inhibited in biofilms composed of several bacteria compared to monobiofilms (40, 48, 50), e.g., Staphylococcus sciuri prevented L. monocytogenes from adhering and being part of a biofilm (50). In contrast, the sessile cell counts of L. monocytogenes on stainless steel were similar in mono- and mixed five-species biofilms in this study, which is in accordance with other studies (40, 46, 51).

S. aureus, the other major pathogen selected, is a renowned biofilm former (52) and also occurs in multispecies biofilms with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (53, 54), B. subtilis (24), Enterococcus faecalis (55), or Candida albicans (53, 56). Some studies have reported that lactic acid bacteria such as Lactococcus spp. and Lactobacillus spp. (57, 58) can inhibit growth of this pathogen, while that was not noticed in this study. However, the sessile cell counts of each of the associated microbial community members, including the pathogen, decreased in the mixed five-species biofilms compared to the sessile cell counts in mono- or dual-species biofilms, which could be due to competition for nutriment and antimicrobial compound production (58).

Here, dairy sample communities were composed of various microorganisms representing the diversity existing in natural and man-made environments. Several studies have demonstrated that processing environments are composed of a large diversity of microorganisms (59, 60), and Dzieciol et al. (59) have shown that microbial communities were distinct depending on the collecting point, as observed in this study. Hence, it could be suggested that the microbial diversity in processing environments, leading to the biofilm diversity, could impair effective disinfection procedure, as Simões et al. (47) also concluded.

To date, very few studies have investigated antimicrobial resistance of mixed-species biofilms (46, 48) including comparisons with monospecies biofilm data. Using the mature mixed five-species biofilms on stainless steel coupons set up in this study, the biofilm models were subjected to biocides similar to those used in the processing environment where the strains were sampled. The effectiveness of biocide treatment on the two pathogens depended on the biocide used as previously shown (8, 44, 61). Peracetic acid treatment impaired survival in mono- and mixed five-species biofilms, while no significant effect of chlorhexidine digluconate was seen at the tested concentrations. da Silva Fernandes et al. (44) have described peracetic acid as the most efficient biocide used in processing environments compared to quaternary ammonium, sodium hypochlorite, or biguanide, and it was able to eliminate L. monocytogenes from the multispecies biofilm as observed in this study at a concentration of 0.15%. Our results indicate that peracetic acid as used in the dairies (0.3%) is efficient in reducing bacterial numbers, since less than 10 CFU/cm2 of sessile cells were recovered after treatment with 0.15% peracetic acid (1/2 of the factory in-use concentration). The effect of chlorhexidine digluconate cannot be evaluated since the biocide precipitated at concentrations above 0.025%.

It is noteworthy that sessile cells of S. aureus were recovered from both mono- and mixed five-species biofilm (comSa) when they were treated with 0.075% peracetic acid. Also, S. aureus sessile cells survived in a monospecies biofilm at this concentration, which was the MIC determined for this pathogen. This corroborates that biofilms can modify and increase the biocide susceptibility response as suggested by some authors (8).

The mixed associated microbial communities, comSa and comLm, protected the pathogens during peracetic acid treatment. Thus, a 1-log difference was obtained between sessile cell counts of L. monocytogenes in mono- and mixed five-species biofilms after biocide treatment. Using the same biocide, van der Veen and Abee (62) also observed that L. monocytogenes was more resistant to peracetic acid in mixed-species biofilm with Lactobacillus plantarum than in monospecies biofilm. In the case of S. aureus sessile cells, a decrease of 2.1 log was obtained between treatments at 0.0375% and 0.075% peracetic acid of the monospecies biofilm, while in a mixed five-species biofilm the decrease was only of 0.2 log. Hence, similar to results reported by Bridier et al. (24), S. aureus was less susceptible to peracetic acid exposure when the pathogen was part of a mixed-species biofilm than when grown as a monospecies biofilm.

We investigated if the increase of pathogen survival in mixed-species biofilm was due to the specific ability of this pathogen in the associated microbial community or to the community itself. We interchanged the pathogens and the associated microbial communities, i.e., S. aureus with comLm and L. monocytogenes with comSa. The new mixed five-species biofilms were treated only with 0.075% peracetic acid, which was the highest concentration that allowed survival sessile cells recovery in the first set of experiments. S. aureus was established at a lower density in comLm than in the original comSa, while the total sessile cell counts increased. However, S. aureus was not protected by the comLm community and no S. aureus sessile cells were recovered. In the biofilm composed of L. monocytogenes with comSa and treated with 0.075% peracetic acid, a slight increase of survival sessile cells of L. monocytogenes was recovered compared to the association with comLm. This could be due to microbial composition variation, comLm being composed of only Gram-negative bacteria while comSa was composed of Gram-positive and -negative bacteria as well as one yeast. Therefore, it is likely the full associated microbial community that is involved in the survival/resistance mechanisms. This protective effect could be due to the microbial species composition, which influences the biofilm matrix composition, as well as the presence of specific microorganisms with higher resistance to the tested biocide; e.g., the MIC for peracetic acid of each member of comLm was 0.075%, whereas members of comSa showed different MIC values ranging from 0.075% to 0.3% (the concentration used in dairy). This is in agreement with the suggestions that biocide resistance could be due to the extracellular matrix or to interactions between the organisms in the mixed biofilm (46, 63).

In conclusion, biofilms can vary due to the microbially diverse populations encountered in man-made environments. This diversity is a key challenge to eradicate unwanted microorganisms. Further studies are required to unravel the exact mechanisms leading to the protective role of the community using complex microbial biofilms mimicking biofilms encountered in industry/clinical or natural environment, as we attempted to set up in this study. Therefore, by improving the knowledge on mixed-species biofilm behavior in the presence of biocides, control of biofilm could be improved in any kind of sector.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth media, and biocides.

The strains of L. monocytogenes and S. aureus used in this study have been isolated from Brazilian dairies (42, 43) (Table 1). Four strains of the associated microbial community were also isolated as described below. They were isolated from the same sample as the pathogenic bacterium to obtain two communities as encountered in the dairy: one containing L. monocytogenes and one containing S. aureus (Table 1).

Two isolates of S. aureus, BZ012 and Sa30, were used in this study. The isolate BZ012 was selected to represent the sequence type ST398 (43), a major possible health risk ST, and was used for dual-biofilm and mixed-species biofilm setup experiments. The isolate Sa30 was chosen because it represented the major ST/CC trend, ST30/CC1, found in the Brazilian dairy industry (43), and this isolate was used for assessing biocide effects on biofilm containing S. aureus (including the MIC assay). It was rationalized that the associated microbial community members isolated from the sample containing S. aureus BZ012 would be suitable for any S. aureus dairy isolates, and therefore, they were also used as community members with the S. aureus Sa30 isolate in the biocide susceptibility experiments.

Isolates were grown on brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid), BHI agar (BHI broth, 1.5% agar; AppliChem) or tryptic soy agar (TSA; Oxoid), de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe agar (MRS), and dichloran rose Bengal chloramphenicol agar (DRBC; Oxoid, UK), and potato dextrose agar plus chloramphenicol (PDA-CAM; Oxoid, UK). S. aureus cells were enumerated on Baird Parker agar (Oxoid, UK) with egg yolk emulsion (Oxoid, UK), and L. monocytogenes cells were counted on Oxford (Oxoid, UK) with modified Listeria selective supplement (Oxoid, UK). Unless otherwise specified, isolates were grown at 37°C and liquid cultures were incubated under shaking conditions at 250 rpm. The isolates were stored in BHI containing 20% (vol/vol) glycerol (Merck, Germany) at −80°C. For biocide treatments, two biocides used in the dairies from where samples were taken were used: peracetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and chlorhexidine digluconate (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). These stock solutions were diluted in 0.9% (wt/vol) NaCl to the selected concentrations.

Selection of 4 associated microorganisms for each pathogen by phenotypical tests.

Using the samples from which L. monocytogenes BZ001 (42) and S. aureus BZ012 (43) were isolated, four associated community members were isolated by surface plating 0.1 ml of a 10-fold-diluted sample in peptone water (0.1%) supplemented with a 0.85% NaCl (Oxoid, UK) suspension on BHI agar, MRS, and DRBC. MRS and BHI agar plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 to 48 h. DRBC plates were incubated at 25°C up to 7 days and then purified on PDA-CAM. Up to three different colonies of different morphologies were selected and purified on the respective culture media for subsequent analysis. Only one community, i.e., four associated community members, for each pathogen species was selected and used in this study.

Species identification.

The isolates were identified by phenotypic characterization and 16S rRNA or 28S rRNA gene sequencing. Shape and motility were determined by microscopy using an Olympus microscope (BX51). Gram reactions were assessed by the 3% KOH method (64). Catalase or cytochrome oxidase was tested using 3% hydrogen peroxide (Merck, Germany) or dry slide (BD Diagnostics, NJ, USA), respectively. DNA manipulation and 16S rRNA gene sequencing using the primer couple 27F (65) and 1492R (66) or NL1 (67) and LS2 (68) for the 28S rRNA gene were performed as described by Oxaran et al. (42) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Primers for species identification

| Taxon | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 27F | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 65 |

| 1492R | GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 66 | |

| Eukaryotes | NL1 | GCCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG | 67 |

| LS2 | ATTCCCAAACAACTCGACTC | 68 | |

| S. aureus | 16S-Saureus-F | ATACAAAGGGCAGCGAAACC | This study |

| 16S-Saureus-R | TCATTTGTCCCACCTTCGAC | This study | |

| L. lactis | 16S-Llactis-F | AAGTTGAGCGCTGAAGGTTG | This study |

| 16S-Llactis-R | AACGCGGGATCATCTTTG | This study | |

| Lactobacillus spp. | 16S-Lbacillus-F | ATTTTGGTCGCCAACGAG | This study |

| 16S-Lbacillus-R | ACCCCACCAACAAGCTAATG | This study | |

| Aeromonas spp. | 16S-Aerom-F | GCAGCGGGAAAGTAGCTTG | This study |

| 16S-Aerom-R | ATATCCAATCGCGCAAGG | This study | |

| C. tropicalis | 16S-Ctropicalis-F | GTCGAGTTGTTTGGGAATGC | This study |

| 16S-Ctropicalis-R | ATCTCAAGCCCTTCCCTTTC | This study |

Development of mature biofilms on SSCs.

In order to reproduce the dairy processing environment, biofilm formation was assessed on stainless steel coupons (SSCs) at 25°C (the temperature noted in the investigated dairies) using an associated microbial community of strains isolated from Brazilian dairies (42, 43). Overnight cultures were inoculated to a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01 in a 5-ml BHI broth tube containing a 1- by 2-cm SSC (AISI 316, unpolished, 2B finish, prepared according to Kastbjerg and Gram [69]). Monospecies biofilms were produced from only one single strain, dual-species biofilms were composed of the pathogenic strain (L. monocytogenes or S. aureus) and one of the associated microbial community members, and mixed five-species biofilms were obtained by the association of a pathogen strain and the four associated microbial community members listed in Table 1 (each inoculated at an equal ratio). Adhesion was performed for 1 h 30 min at 25°C, with shaking at 90 rpm. Subsequently, the medium was gently discarded to remove planktonic and loosely attached cells and replaced with BHI broth followed by incubation at 25°C, with shaking at 90 rpm. To obtain a mature biofilm, the S. aureus-containing biofilm was incubated for 25 h and the L. monocytogenes-containing biofilm for 72 h.

Enumeration of planktonic and sessile cells.

Viable sessile cells in the mature biofilm on SSCs were enumerated by determination of CFU. The SSCs were gently washed three times with 2 ml NaCl (0.9%) and subsequently sonicated in 2 ml NaCl (0.9%) for 2 min (Delta 220T; Aerosec Industrie). The CFU count of viable sessile cells was assessed by the drop plating method on BHI agar for the total cell count (including all the associated microbial community members), and for the model pathogen cell count, a selective medium was used, i.e., BP or Oxford for S. aureus or L. monocytogenes, respectively. As growth control, the planktonic cell counts were done using the same method. The results considered the detection limit of the method used in this study, which was 10 CFU/cm2.

Species presence assessment.

To check that all associated microbial community members remained in the mature biofilm, two methods were used. For the community containing L. monocytogenes, species presence was evaluated by colony morphology on BHI agar, as the five community members showed distinct colony morphology. For the community containing S. aureus, colonies were not distinguishable on agar plate, and PCR using species-specific primers (Table 2) was used to detect the different organisms. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) from the sessile cells using the same suspension as that used for enumeration, as per the manufacturer′s recommendations. PCRs were performed using the TEMPase Hot Start 2× Master mix Blue II (Ampliqon, Denmark) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One microliter of gDNA was added as a matrix. The PCR was run in a Veriti thermal cycler (96-well model 9902; Applied Biosystems), and the amplicon presence was checked by gel electrophoresis.

MIC of biocides.

A first assessment of biocide susceptibility was performed using MIC assays in order to target concentrations to be used in the biofilm model. The concentrations used in the dairies were 0.3% and 0.04% for peracetic acid and chlorhexidine digluconate, respectively (S. H. I. Lee, personal communication). Each pathogen (L. monocytogenes and S. aureus Sa30) was assessed by MIC assay as monoculture and mixed culture (with the four associated microorganisms). The MIC assay was also done for the individual community members by following the same protocol. Overnight cultures were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.02 in BHI, and 100 μl was dispensed into wells (96-well, round-bottom microtiter plate; Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) containing 100 μl of a serial dilution of each biocide. The final biocide concentrations tested started at 4.8% and decremented by 2 up to 13 times for peracetic acid and started at 0.05% and decremented by 2 up to 9 times for chlorhexidine digluconate. The MIC was determined after incubation for 24 h at 25°C with shaking at 90 rpm and was defined as the minimum concentration inhibiting growth.

Biocide treatment of mature biofilm on stainless steel coupons.

After development of mature mono- or mixed five-species biofilms, sessile cells were subjected to disinfection treatment. SSCs were washed two times in 2 ml 0.9% NaCl-containing plates (6-well plate; Nunc, Denmark) and then immersed in 2 ml 0.9% NaCl solution at the selected biocide concentrations. Biocide treatment was stopped after 20 min of exposure (69) at 25°C with shaking at 90 rpm by transferring the SSCs to 2 ml of Dey-Engley neutralizing broth. Then, the SSCs were sonicated for 2 min in the neutralizing solution and enumeration was performed as described above.

Statistic data analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Excel Data Tool to process all data by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significance was defined with a Fisher test value as a P value of ≤0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Danish Council for Strategic Research (project number 0603-00552B), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP # 2012/50507-1), and the Goiás Research Foundation (FAPEG #2012/10267001047). This study was also financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES), finance code 001.

Author contributions: study concept and design, V.O. and L.G.; planning and sampling at dairies, L.T.C., S.H.I.L., C.H.C., E.C.P.D.M., V.F.A., and C.A.F.D.O.; analysis and interpretation of data, K.K.D. and V.O.; drafting of the manuscript, V.O.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, L.G., E.C.P.D.M., V.F.A., V.O., C.H.C., and C.A.F.D.O.; statistical analysis, V.O.

We declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Møretrø T, Sonerud T, Mangelrød E, Langsrud S. 2006. Evaluation of the antibacterial effect of a triclosan-containing floor used in the food industry. J Food Prot 69:627–633. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donlan RM. 2011. Biofilm elimination on intravascular catheters: important considerations for the infectious disease practitioner. Clin Infect Dis 52:1038–1045. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerf O, Carpentier B, Sanders P. 2010. Tests for determining in-use concentrations of antibiotics and disinfectants are based on entirely different concepts: “resistance” has different meanings. Int J Food Microbiol 136:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkinson HF, Lappin-Scott HM. 2001. Biofilms adhere to stay. Trends Microbiol 9:9–10. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davey ME, O'toole GA. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:847–867. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.847-867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elias S, Banin E. 2012. Multi-species biofilms: living with friendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:990–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadell CD, Xavier JB, Foster KR. 2009. The sociobiology of biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33:206–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juzwa W, Myszka K, Białas W, Dobrucka R, Konieczny P, Czaczyk K. 2015. Investigation of the effectiveness of disinfectants against planktonic and biofilm forms of P. aeruginosa and E. faecalis cells using a compilation of cultivation, microscopic and flow cytometric techniques. Biofouling 31:587–597. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2015.1075126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saá Ibusquiza P, Herrera JJR, Cabo ML. 2011. Resistance to benzalkonium chloride, peracetic acid and nisin during formation of mature biofilms by Listeria monocytogenes. Food Microbiol 28:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belessi C-EA, Gounadaki AS, Psomas AN, Skandamis PN. 2011. Efficiency of different sanitation methods on Listeria monocytogenes biofilms formed under various environmental conditions. Int J Food Microbiol 145:S46–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry D, Xi C, Raskin L. 2006. Microbial ecology of drinking water distribution systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol 17:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts AP, Mullany P. 2010. Oral biofilms: a reservoir of transferable, bacterial, antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 8:1441–1450. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal S, Pearce M, Achilles-Day UEM, Day JG, Morton LHG, Crean SJ, Singhrao SK. 2017. Developing an ecologically relevant heterogeneous biofilm model for dental-unit waterlines. Biofouling 33:75–87. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2016.1260710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benítez-Páez A, Belda-Ferre P, Simón-Soro A, Mira A. 2014. Microbiota diversity and gene expression dynamics in human oral biofilms. BMC Genomics 15:311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartrons M, Catalan J, Casamayor EO. 2012. High bacterial diversity in epilithic biofilms of oligotrophic mountain lakes. Microb Ecol 64:860–869. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Røder HL, Raghupathi PK, Herschend J, Brejnrod A, Knøchel S, Sørensen SJ, Burmølle M. 2015. Interspecies interactions result in enhanced biofilm formation by co-cultures of bacteria isolated from a food processing environment. Food Microbiol 51:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simões M, Simões LC, Vieira MJ. 2009. Species association increases biofilm resistance to chemical and mechanical treatments. Water Res 43:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burmølle M, Webb JS, Rao D, Hansen LH, Sørensen SJ, Kjelleberg S. 2006. Enhanced biofilm formation and increased resistance to antimicrobial agents and bacterial invasion are caused by synergistic interactions in multispecies biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:3916–3923. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03022-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bridier A, Briandet R, Thomas V, Dubois-Brissonnet F. 2011. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to disinfectants: a review. Biofouling 27:1017–1032. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2011.626899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdallah M, Khelissa O, Ibrahim A, Benoliel C, Heliot L, Dhulster P, Chihib N-E. 2015. Impact of growth temperature and surface type on the resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms to disinfectants. Int J Food Microbiol 214:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Silva Meira QG, de Medeiros Barbosa I, Alves Aguiar Athayde AJ, de Siqueira-Júnior JP, de Souza EL. 2012. Influence of temperature and surface kind on biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus from food-contact surfaces and sensitivity to sanitizers. Food Control 25:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Vizuete P, Orgaz B, Aymerich S, Le Coq D, Briandet R. 2015. Pathogens protection against the action of disinfectants in multispecies biofilms. Front Microbiol 6:705. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habimana O, Meyrand M, Meylheuc T, Kulakauskas S, Briandet R. 2009. Genetic features of resident biofilms determine attachment of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7814–7821. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01333-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bridier A, Sanchez-Vizuete MDP, Le Coq D, Aymerich S, Meylheuc T, Maillard J-Y, Thomas V, Dubois-Brissonnet F, Briandet R. 2012. Biofilms of a Bacillus subtilis hospital isolate protect Staphylococcus aureus from biocide action. PLoS One 7:e44506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdallah M, Benoliel C, Drider D, Dhulster P, Chihib NE. 2014. Biofilm formation and persistence on abiotic surfaces in the context of food and medical environments. Arch Microbiol 196:453–472. doi: 10.1007/s00203-014-0983-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P. 2007. The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes Infect 9:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borucki MK, Peppin JD, White D, Loge F, Call DR. 2003. Variation in biofilm formation among strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:7336–7342. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7336-7342.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kadam SR, den Besten HMW, van der Veen S, Zwietering MH, Moezelaar R, Abee T. 2013. Diversity assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation: impact of growth condition, serotype and strain origin. Int J Food Microbiol 165:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundén J, Autio T, Markkula A, Hellström S, Korkeala H. 2003. Adaptive and cross-adaptive responses of persistent and non-persistent Listeria monocytogenes strains to disinfectants. Int J Food Microbiol 82:265–272. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabuki DY, Kuaye AY, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2004. Molecular subtyping and tracking of Listeria monocytogenes in Latin-style fresh-cheese processing plants. J Dairy Sci 87:2803–2812. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Loir Y, Baron F, Gautier M. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning. Genet Mol Res 2:63–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J-S, Bae Y-M, Lee S-Y, Lee S-Y. 2015. Biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus on various surfaces and their resistance to chlorine sanitizer. J Food Sci 80:M2279–M2286. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rode TM, Langsrud S, Holck A, Møretrø T. 2007. Different patterns of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus under food-related stress conditions. Int J Food Microbiol 116:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kathariou S. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes virulence and pathogenicity, a food safety perspective. J Food Prot 65:1811–1829. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-65.11.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusumaningrum HD, Riboldi G, Hazeleger WC, Beumer RR. 2003. Survival of foodborne pathogens on stainless steel surfaces and cross-contamination to foods. Int J Food Microbiol 85:227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallim DC, Barroso Hofer C, Lisbôa R de C, Barbosa AV, Alves Rusak L, dos Reis CMF, Hofer E. 2015. Twenty years of Listeria in Brazil: occurrence of Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes serovars in food samples in Brazil between 1990 and 2012. Biomed Res Int 2015:540204. doi: 10.1155/2015/540204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veras JF, do Carmo LS, Tong LC, Shupp JW, Cummings C, Dos Santos DA, Cerqueira MMOP, Cantini A, Nicoli JR, Jett M. 2008. A study of the enterotoxigenicity of coagulase-negative and coagulase-positive staphylococcal isolates from food poisoning outbreaks in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Int J Infect Dis 12:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SHI, Camargo CH, Gonçalves JL, Cruz AG, Sartori BT, Machado MB, Oliveira CAF. 2012. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in milk and the milking environment from small-scale dairy farms of São Paulo, Brazil, using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Dairy Sci 95:7377–7383. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutiérrez D, Delgado S, Vázquez-Sánchez D, Martínez B, Cabo ML, Rodríguez A, Herrera JJ, García P. 2012. Incidence of Staphylococcus aureus and analysis of associated bacterial communities on food industry surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:8547–8554. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02045-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carpentier B, Chassaing D. 2004. Interactions in biofilms between Listeria monocytogenes and resident microorganisms from food industry premises. Int J Food Microbiol 97:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdallah M, Chataigne G, Ferreira-Theret P, Benoliel C, Drider D, Dhulster P, Chihib N-EE. 2014. Effect of growth temperature, surface type and incubation time on the resistance of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms to disinfectants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:2597–2607. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oxaran V, Lee SHI, Chaul LT, Corassin CH, Barancelli GV, Alves VF, de Oliveira CAF, Gram L, De Martinis ECP. 2017. Listeria monocytogenes incidence changes and diversity in some Brazilian dairy industries and retail products. Food Microbiol 68:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dittmann KK, Chaul LT, Lee SHI, Corassin CH, Fernandes de Oliveira CA, Pereira De Martinis EC, Alves VF, Gram L, Oxaran V. 2017. Staphylococcus aureus in some Brazilian dairy industries: changes of contamination and diversity. Front Microbiol 8:2049. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.da Silva Fernandes M, Kabuki DY, Kuaye AY. 2015. Behavior of Listeria monocytogenes in a multi-species biofilm with Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium and control through sanitation procedures. Int J Food Microbiol 200C:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giaouris E, Chorianopoulos N, Doulgeraki A, Nychas G-J. 2013. Co-culture with Listeria monocytogenes within a dual-species biofilm community strongly increases resistance of Pseudomonas putida to benzalkonium chloride. PLoS One 8:e77276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kostaki M, Chorianopoulos N, Braxou E, Nychas GJ, Giaouris E. 2012. Differential biofilm formation and chemical disinfection resistance of sessile cells of Listeria monocytogenes strains under monospecies and dual-species (with Salmonella enterica) conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2586–2595. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07099-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simões LC, Simões M, Vieira MJ. 2010. Influence of the diversity of bacterial isolates from drinking water on resistance of biofilms to disinfection. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:6673–6679. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00872-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Norwood DE, Gilmour A. 2000. The growth and resistance to sodium hypochlorite of Listeria monocytogenes in a steady-state multispecies biofilm. J Appl Microbiol 88:512–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nilsson RE, Ross T, Bowman JP. 2011. Variability in biofilm production by Listeria monocytogenes correlated to strain origin and growth conditions. Int J Food Microbiol 150:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leriche V, Carpentier B. 2000. Limitation of adhesion and growth of Listeria monocytogenes on stainless steel surfaces by Staphylococcus sciuri biofilms. J Appl Microbiol 88:594–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rieu A, Briandet R, Habimana O, Garmyn D, Guzzo J, Piveteau P. 2008. Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e biofilms: no mushrooms but a network of knitted chains. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:4491–4497. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00255-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bridier A, Dubois-Brissonnet F, Boubetra A, Thomas V, Briandet R. 2010. The biofilm architecture of sixty opportunistic pathogens deciphered using a high throughput CLSM method. J Microbiol Methods 82:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kart D, Tavernier S, Van Acker H, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. 2014. Activity of disinfectants against multispecies biofilms formed by Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biofouling 30:377–383. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.878333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seth AK, Geringer MR, Hong SJ, Leung KP, Galiano RD, Mustoe TA. 2012. Comparative analysis of single-species and polybacterial wound biofilms using a quantitative, in vivo, rabbit ear model PLoS One 7:e42897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kucera J, Sojka M, Pavlik V, Szuszkiewicz K, Velebny V, Klein P. 2014. Multispecies biofilm in an artificial wound bed—a novel model for in vitro assessment of solid antimicrobial dressings. J Microbiol Methods 103:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, Scheper MA, Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2010. Microbial interactions and differential protein expression in Staphylococcus aureus-Candida albicans dual-species biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Charlier C, Cretenet M, Even S, Le Loir Y. 2009. Interactions between Staphylococcus aureus and lactic acid bacteria: an old story with new perspectives. Int J Food Microbiol 131:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ammor S, Tauveron G, Dufour E, Chevallier I. 2006. Antibacterial activity of lactic acid bacteria against spoilage and pathogenic bacteria isolated from the same meat small-scale facility. Food Control 17:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2005.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dzieciol M, Schornsteiner E, Muhterem-Uyar M, Stessl B, Wagner M, Schmitz-Esser S. 2016. Bacterial diversity of floor drain biofilms and drain waters in a Listeria monocytogenes contaminated food processing environment. Int J Food Microbiol 223:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chmielewski RAN, Frank JF. 2003. Biofilm formation and control in food processing facilities. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2:22–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.da Costa Luciano C, Olson N, Tipple AFV, Alfa M. 2016. Evaluation of the ability of different detergents and disinfectants to remove and kill organisms in traditional biofilm. Am J Infect Control 44:e243–e249. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Veen S, Abee T. 2011. Mixed species biofilms of Listeria monocytogenes and Lactobacillus plantarum show enhanced resistance to benzalkonium chloride and peracetic acid. Int J Food Microbiol 144:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan Y, Breidt F, Kathariou S. 2006. Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes biofilms to sanitizing agents in a simulated food processing environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:7711–7717. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01065-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halebian S, Harris B, Finegold SM, Rolfei RD. 1981. Rapid method that aids in distinguishing Gram-positive from Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 13:444–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lane DJJ. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p 115–175. In Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M (ed), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Wiley Online Library, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turner S, Pryer KM, Miao VP, Palmer JD. 1999. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J Eukaryot Microbiol 46:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Donnell K. 1993. Fusarium and its near relatives, p 225–233. In Reynolds DR, Taylor JW (ed), The fungal holomorph: mitotic, meiotic and pleomorphic speciation in fungal systematics. CAB International, Wallingford, CT. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cocolin L, Bisson LF, Mills DA. 2000. Direct profiling of the yeast dynamics in wine fermentations. FEMS Microbiol Lett 189:81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kastbjerg VG, Gram L. 2009. Model systems allowing quantification of sensitivity to disinfectants and comparison of disinfectant susceptibility of persistent and presumed nonpersistent Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Microbiol 106:1667–1681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]