Abstract

Background

This study was conducted to evaluate the prognostic and recurrent impact of EGFR mutation status in resected pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma with consideration of the histological subtype.

Methods

Following retrospective analysis of whole 474 consecutive pathological N0M0 lung adenocarcinoma patients, the prognostic significance of EGFR mutation status was evaluated in limited 394 subjects. Overall survival and recurrence‐free interval (RFI) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using a log‐rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

The five‐year RFI was 85.7% and 93.3% for EGFR positive (n = 176) and negative (n = 218) cases, respectively (hazard ratio [HR] 1.992, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.005–3.982; P = 0.048). Following the exclusion of specific subtypes free from recurrence or EGFR mutation (adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma), the five‐year RFI was obviously poorer in EGFR positive compared to negative cases (80.7% and 92.1%, respectively; HR 2.163, 95% CI 1.055–4.341; P = 0.035). Multivariate analysis excluding the specific subtypes confirmed that male sex, age, current or Ex‐smoking status, pleural invasion, and EGFR‐positive status were independently associated with shorter RFI. No significant differences in five‐year overall survival were found between the EGFR mutation positive and negative groups (88.7% and 93.7%, respectively; HR 1.630, 95% CI 0.787–3.432; P = 0.2).

Conclusion

EGFR mutations are associated with recurrence in pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma. EGFR mutation status and histological subtype should be considered when evaluating the risk of recurrence in resected lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Keywords: EGFR mutation, histological subtype, lung adenocarcinoma, recurrence, surgery

Introduction

EGFR mutations represent one of the most frequent genetic aberrations in lung adenocarcinoma. The frequency in Asia is reported at 40–60%.1, 2 Somatic mutations in EGFR are more likely to occur in Asian, female, and adenocarcinoma patients.1, 3 A number of studies have estimated the prognostic impact of EGFR mutation in resected non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients; however, most of them included several types of histology and advanced stage. The prognostic significance of EGFR mutations as oncogenic driver mutations in resected pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma is yet to be determined. Herein, we evaluated the oncological consequences of EGFR mutations in pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma. In addition to overall survival (OS), the recurrence‐free interval (RFI) was utilized to estimate the oncological impact of EGFR mutation on recurrence. By using the RFI, death unrelated to lung cancer and the therapeutic effect of EGFR‐tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) were excluded.

Methods

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of consecutive patients with pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma at a single institution. Patient medical records were reviewed, and clinicopathological data including EGFR mutation status were obtained. The frequency of EGFR mutations was assessed in relation to different clinicopathological characteristics. The impact of EGFR mutation status on OS and RFI was evaluated in resected pN0M0 lung adenocarcinomas in all cases, as well as in a limited subset. In analysis of the limited subset, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) were excluded as there is no risk of recurrence in AIS/MIA and EGFR mutation does not occur in IMA.

The effects of EGFR mutation status on OS and RFI were initially estimated in all 394 tumors. Subsequently, OS and RFI were calculated for specific histological subtypes by considering the risk of recurrence and positive EGFR mutation status. After excluding AIS, MIA, and IMA, the analyzed cases included those ≤ 5 cm in tumor diameter and classified as pathological stage IA1–IIA, according to the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) tumor node metastasis (TNM) classification system (8th edition).4 All included cases underwent complete resection. Pathological diagnoses were conducted by two pathologists according to IASLC/American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) classification.5 If multiple tumors were resected in a single patient, they were identified as intrapulmonary metastases or independent tumors according to the latest IASLC proposals.6, 7 In cases where tumors were diagnosed independently of one another, each was considered a primary tumor. Observations of non‐relapsed tumors were censored at the time of recurrence in patients with multiple primary tumors.

The Institutional Review Board of Hiroshima University (Hiroshima, Japan) approved the retrospective design of this study for utilizing resected specimens and collecting and analyzing patient data (E‐12). All study participants provided informed written consent. The research was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Patients

The data of 474 consecutive lung adenocarcinoma patients who underwent surgical resection for pN0M0 disease at the Hiroshima University Hospital (Hiroshima, Japan) between January 2007 and December 2013 were retrospectively analyzed. The records of patients who underwent surgical resection with therapeutic intent were reviewed, and only completely resected cases were enrolled in the study. In cases treated with lobectomy (n = 232) or segmentectomy (n = 94), the lack of lymph node metastasis was confirmed by systematic or lobe‐specific lymphadenectomy. In cases where lymph node metastasis was not suspected by preoperative computed tomography (CT), positron‐emission tomography (PET)‐CT, and curative resection by wedge resection was deemed achievable intraoperatively, lymph node resection was omitted. Regardless of whether evaluation was performed by an external examination body or the institutional laboratory, EGFR mutation status was determined using a peptide nucleic acid (PNA)‐locked nucleic acid (LNA) PCR clamp‐based detection test as previously described.8 EGFR mutation status was usually established during the clinical course by an external examination body (LSI Medience Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with specimens obtained from bronchoscopic biopsy, frozen tissue, or formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) tissue. If EGFR mutation was not evaluated during the clinical course, DNA was extracted from frozen tissue sections using a QIAamp DNA Micro Kit or from FFPE tissue sections using a QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) in the institutional laboratory. The PNA‐LNA PCR clamp‐based detection test was conducted using a 7900HT Fast Real‐Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Primers and probes were supplied by Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Coralville, IA, USA). Details of the PCR conditions and oligonucleotide sequences of each primer and probe are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analyses

Overall survival and RFI were used to evaluate the oncological significance of EGFR mutation status. OS was defined as the interval between the date of surgery and the date of death from any cause. RFI was defined as the interval between the date of surgery and the date of radiologically detected recurrence. Patients who died from causes other than lung cancer were censored from RFI analysis. OS and RFI were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between survival curves were analyzed using the log‐rank test. The significance of frequencies was evaluated by chi‐square test. Patient age and pathological tumor size were compared as continuous variables using Mann–Whitney U tests. Univariate analyses were built with EGFR mutation status and clinicopathological factors regarding prognosis, and multivariate analysis was conducted using a Cox proportional hazards model with a backward stepwise procedure. P values calculated in two‐tailed tests were employed and < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and StatMate V (ATMS Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

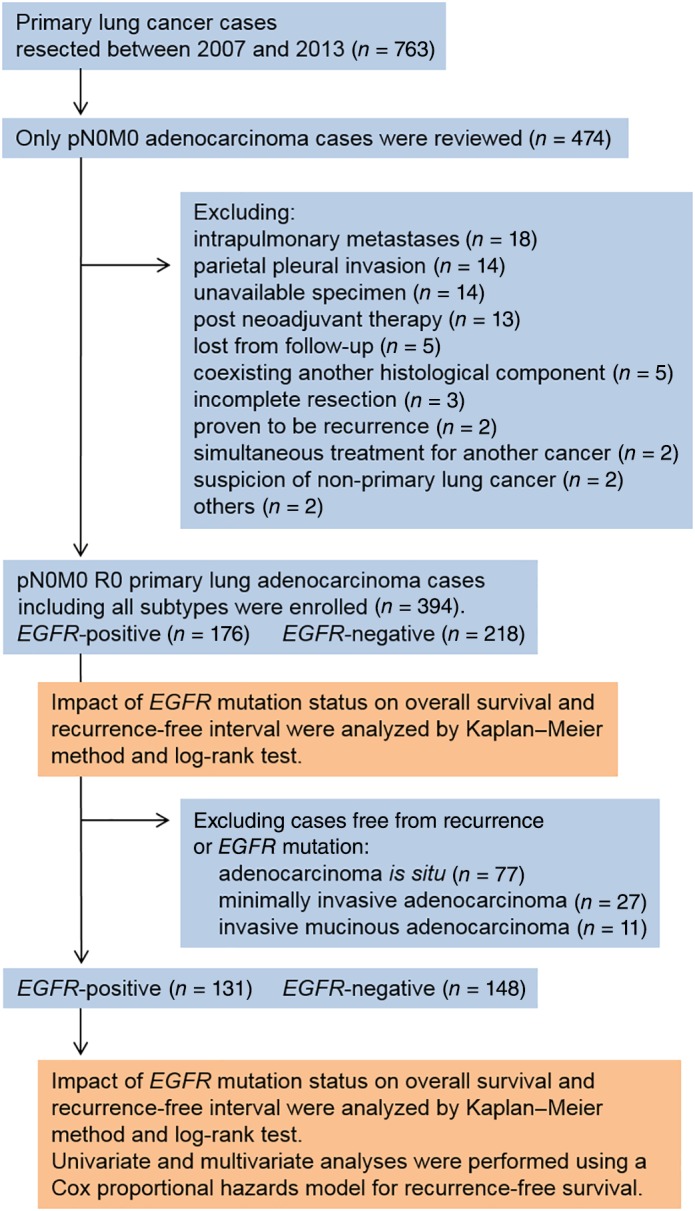

The CONSORT diagram of the study is shown in Figure 1. Of the 474 lung adenocarcinoma cases reviewed, 80 were excluded according to the following criteria: intrapulmonary metastases (n = 18); parietal pleural invasion (n = 14); specimen unavailability (n = 14); post neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy (n = 13); loss during postoperative follow‐up (n = 5); accompanied by another histological component (n = 5); incomplete resection (n = 3); proven to be recurrence (n = 2); simultaneously administered therapies for carcinoma of another organ (n = 2); potential to be a non‐primary lung adenocarcinoma (n = 2); recurrence of uncertain origin because of repeated surgery for several types of cancer (n = 1); and lung pleomorphic carcinoma occurring within a short interval after lung adenocarcinoma resection (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of the study.

Twenty‐six patients underwent resection for multiple lung adenocarcinomas (55 tumors in total) that were diagnosed as independent primary adenocarcinomas. Among patients with multiple lung adenocarcinomas, three tumors recurred, including one at the surgical margin and two intrapulmonary recurrences. In the latter two cases, the resected primary tumors were invasive adenocarcinoma and AIS or MIA. Therefore, we determined that invasive carcinoma was responsible for the recurrence. In the whole cohort, 33 patients recurred: local (lung or intrapulmonary lymph node) in 15, regional (mediastinal or intrapleural region) in 12, and distant (extra‐thoracic lymph node or another organ) in 6 patients.

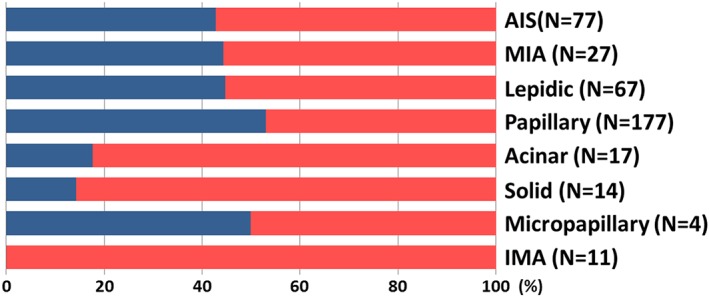

The prognostic impact of EGFR mutation status was evaluated in 394 tumors from 365 patients. The median follow‐up was 50.4 months (interquartile range [IQR] 28.1 months). A summary of the clinicopathological characteristics of the 394 cases enrolled in this study is provided in Table 1. EGFR mutation status was positive in 176 cases (44.7%). The frequency of EGFR mutation positivity was significantly higher in female patients; non‐smokers; patients with larger tumors (median 2.0 cm [IQR 1.2 cm] vs. 1.6 cm [IQR 1.3 cm] for EGFR positive and negative cases, respectively); papillary predominant subtypes; and cases accompanied by a lepidic or micropapillary component. Conversely, EGFR mutation positive status was observed significantly less frequently in the acinar and solid predominant histological subtypes. None of the IMA cases harbored an EGFR mutation (Table 2). The frequencies of EGFR mutations in different histological subtypes are summarized in Figure 2. Among the EGFR mutation positive cases, the proportions with an exon 19 deletion and L858R mutation were 39.2% (n = 69) and 53.4% (n = 94), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the enrolled lung adenocarcinoma cases (n = 394)

| Clinicopathological characteristic | Cases (n = 394) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median | 67 |

| Interquartile range | 14.0 |

| Sex, N (%) | |

| M | 195 (49.5) |

| F | 199 (50.5) |

| Smoking status, N (%) | |

| Current or Ex‐smoker | 182 (46.2) |

| Never‐smoker | 212 (53.8) |

| Surgical procedure, N (%) | |

| Lobectomy | 232 (58.9) |

| Segmentectomy | 94 (23.9) |

| Wedge resection | 68 (17.3) |

| Pathological tumor size, N (%) | |

| ≤ 1.0 cm | 77 (19.5) |

| > 1.0 and ≤ 2.0 cm | 163 (41.4) |

| > 2.0 and ≤ 3.0 cm | 97 (24.6) |

| > 3.0 cm | 57 (14.5) |

| Predominant subtype, N (%) | |

| AIS | 77 (19.5) |

| MIA | 27 (6.9) |

| Lepidic | 67 (17.0) |

| Papillary | 177 (44.9) |

| Acinar | 17 (4.3) |

| Solid | 14 (3.6) |

| Micropapillary | 4 (1.0) |

| IMA | 11 (2.8) |

| EGFR mutation status, N (%) | |

| Positive | 176 (44.7) |

| Negative | 218 (55.3) |

| EGFR mutant variants, N (%) | 176 (100) |

| Ex18 MUT | 11 (6.3) |

| Ex19 DEL | 68 (38.6) |

| Ex21 MUT | 95 (54.0) |

| L858R | 92 (52.3) |

| L861Q | 3 (1.7) |

| Double mutation | 2 (1.1) |

| Ex18 MUT and L858R | 1 (0.6) |

| Ex19 DEL and L858R | 1 (0.6) |

| Pleural invasion, N (%) | |

| Y | 53 (13.5) |

| N | 341 (86.5) |

| Lymphatic invasion, N (%) | |

| Y | 35 (8.9) |

| N | 359 (91.1) |

| Vascular invasion, N (%) | |

| Y | 50 (12.7) |

| N | 344 (87.3) |

| Recurrence, N (%) | |

| Y | 33 (8.4) |

| N | 361 (91.6) |

AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; DEL, deletion; Ex, exon; F, female; IMA, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma; L, leucine; M, male; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma; MUT, mutation; N, no; Q, glutamine; R, arginine; Y, yes.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the enrolled lung adenocarcinoma cases (n = 394) according to EGFR mutation status

| Clinicopathological characteristic | Cases (n = 394) | EGFR mutation status | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 176) | Negative (n = 218) | |||

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 67 | 67 | 66 | |

| Interquartile range | 14.0 | 13.0 | 13.25 | 0.5 |

| Sex, N (%) | ||||

| M | 195 | 75 (42.6) | 120 (55.0) | |

| F | 199 | 101 (57.4) | 98 (45.0) | 0.01* |

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||

| Current or Ex‐smoker | 182 | 68 (38.6) | 114 (52.3) | |

| Never‐smoker | 212 | 108 (61.4) | 104 (47.7) | 0.007* |

| Surgical procedure, N (%) | ||||

| Lobectomy | 232 | 110 (62.5) | 122 (56.0) | 0.2 |

| Segmentectomy | 94 | 42 (23.9) | 52 (23.9) | 1.0 |

| Wedge resection | 68 | 24 (13.6) | 44 (20.2) | 0.09 |

| Pathological tumor size, cm | ||||

| Median | 1.85 | 2.0 | 1.6 | |

| Interquartile range | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.03* |

| Pathological tumor size, N (%) | ||||

| ≤ 1.0 cm | 77 | 27 (15.3) | 50 (22.9) | 0.06 |

| > 1.0 and ≤ 2.0 cm | 159 | 68 (38.6) | 91 (41.7) | 0.5 |

| > 2.0 and ≤ 3.0 cm | 98 | 50 (27.9) | 48 (22.0) | 0.1 |

| > 3.0 cm | 60 | 31 (17.6) | 29 (13.3) | 0.2 |

| Predominant subtype, N (%) | ||||

| AIS | 77 | 33 (18.8) | 44 (20.2) | 0.7 |

| MIA | 27 | 12 (6.8) | 15 (6.9) | 1.0 |

| Lepidic | 67 | 30 (17.0) | 37 (17.0) | 1.0 |

| Papillary | 177 | 94 (53.4) | 83 (38.1) | 0.002* |

| Acinar | 17 | 3 (1.7) | 14 (6.4) | 0.04* |

| Solid | 14 | 2 (1.1) | 12 (5.5) | 0.04* |

| Micropapillary | 4 | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.9) | 0.8 |

| IMA | 11 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (5.0) | 0.007* |

| Lepidic component, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 309 | 149 (84.7) | 160 (73.4) | |

| N | 85 | 27 (15.3) | 58 (26.6) | 0.007* |

| Micropapillary component, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 85 | 49 (27.8) | 36 (16.5) | |

| N | 309 | 127 (72.2) | 182 (83.5) | 0.007* |

| Solid component, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 37 | 12 (6.8) | 25 (11.5) | |

| N | 357 | 164 (93.2) | 193 (88.5) | 0.1 |

| Mucinous component, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 51 | 10 (5.7) | 41 (18.8) | |

| N | 343 | 166 (94.3) | 177 (81.2) | < 0.001* |

| Pleural invasion, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 53 | 19 (10.8) | 34 (15.6) | |

| N | 341 | 157 (89.2) | 184 (84.4) | 0.2 |

| Lymphatic invasion, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 35 | 14 (8.0) | 21 (9.6) | |

| N | 359 | 162 (92.0) | 197 (90.4) | 0.6 |

| Vascular invasion, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 50 | 23 (13.1) | 27 (12.4) | |

| N | 344 | 153 (86.9) | 191 (87.6) | 0.8 |

| Recurrence, N (%) | ||||

| Y | 33 | 19 (10.8) | 14 (6.4) | |

| N | 361 | 157 (89.2) | 204 (93.6) | 0.12 |

P < 0.05. AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; F, female; IMA, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma; M, male; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma; N, no; Y, yes

Figure 2.

Frequency of EGFR mutation status according to predominant histological subtype. EGFR positive cases are represented by the blue bar, and EGFR negative by the red bar. ( ) positive, and (

) positive, and ( ) negative.

) negative.

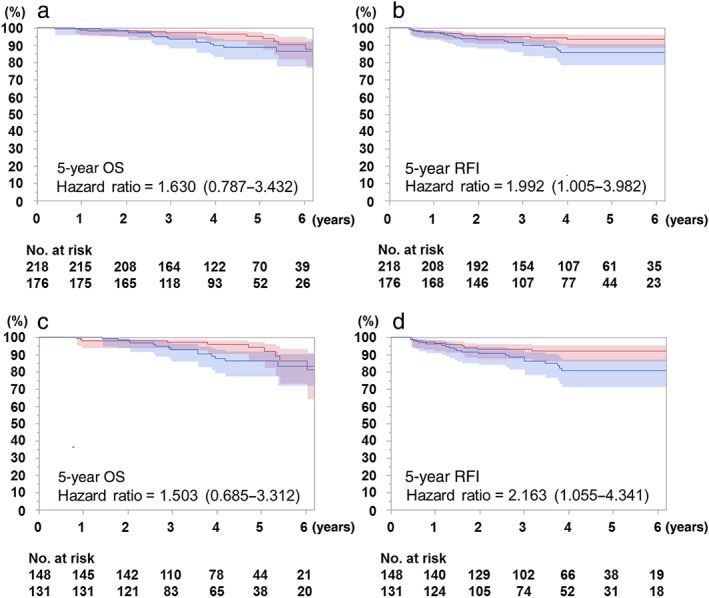

The overall five‐year OS was 88.7% and 93.7% for the EGFR positive and negative cases, respectively (hazard ratio [HR] 1.630, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.787–3.432; P = 0.2). The overall five‐year RFI was 85.7% and 93.3% for the EGFR positive and negative cases, respectively (HR 1.992, 95% CI 1.005–3.982; P = 0.048).

After excluding AIS, MIA, and IMA cases, the five‐year OS was 86.3% and 94.1% for EGFR positive and negative cases, respectively (HR 1.503, 95% CI 0.685–3.312; P = 0.3). The five‐year RFI was 80.7% and 92.1% for EGFR positive and negative cases, respectively (HR 2.163, 95% CI 1.055–4.341; P = 0.035) (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) and recurrence‐free interval (RFI) according to EGFR mutation status. Confidence limits are shown as colored shaded areas. (a) OS and (b) RFI curves of all histological subtypes (n = 394). (c) OS and (d) RFI curves of specific subtypes, excluding adenocarcinoma in situ, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (n = 279). (a) ( ) Negative 93.7%, (

) Negative 93.7%, ( ) Positive 88.7%, p = 0.2, (b) (

) Positive 88.7%, p = 0.2, (b) ( ) Negative 93.3%, (

) Negative 93.3%, ( ) Positive 85.7% p = 0.048, (c) (

) Positive 85.7% p = 0.048, (c) ( ) Negative 94.1%, (

) Negative 94.1%, ( ) Positive 86.3% p = 0.3, (d) (

) Positive 86.3% p = 0.3, (d) ( ) Negative 92.1%, and (

) Negative 92.1%, and ( ) Positive 80.7% p = 0.035.

) Positive 80.7% p = 0.035.

Univariate analysis after excluding AIS, MIA, and IMA cases identified age, pathological tumor size (cm), a highly malignant subtype (micropapillary/solid predominant adenocarcinoma), pleural/lymphatic/vascular invasion, and positive EGFR mutation status as significantly associated with shorter RFI. Multivariate analysis confirmed that male sex (HR 0.273, 95% CI 0.087–0.860; P = 0.027), age (HR 1.078, 95% CI 1.032–1.125; P = 0.001), current or Ex‐Smoking status (HR 3.056, 95% CI 1.087–8.590; P = 0.034), pleural invasion (HR 5.454, 95% CI 2.250–13.222; P < 0.001), and positive EGFR mutation status (HR 2.607, 95% CI 1.042–6.523; P = 0.041) were independently associated with poor RFI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of recurrence‐free interval in pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma cases, excluding AIS, MIA, and IMA (n = 279)

| Prognostic factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Male sex | 0.616 (0.302–1.257) | 0.183 | 0.273 (0.087–0.860) | 0.027* |

| Age | 1.063 (1.020–1.108) | 0.004* | 1.078 (1.032–1.125) | 0.001* |

| Current or ex‐smoking history | 1.025 (0.507–2.074) | 0.945 | 3.056 (1.087–8.590) | 0.034* |

| Pathological tumor size | 2.082 (1.437–3.015) | < 0.001* | 1.513 (0.966–2.370) | 0.071 |

| High malignancy subtype | 3.405 (1.305–8.882) | 0.012* | 0.984 (0.301–3.220) | 0.979 |

| Sublobar resection | 0.633 (0.273–1.470) | 0.287 | 1.071 (0.391–2.930) | 0.894 |

| Pleural invasion | 7.599 (3.716–15.539) | < 0.001* | 5.454 (2.250–13.222) | < 0.001* |

| Lymphatic invasion | 3.471 (1.580–7.624) | 0.002* | 0.745 (0.279–1.985) | 0.556 |

| Vascular invasion | 5.342 (2.573–11.093) | < 0.001* | 2.412 (0.991–5.874) | 0.052 |

| Positive EGFR mutation status | 2.165 (1.037–4.519) | 0.040* | 2.607 (1.042–6.523) | 0.041* |

P < 0.05. AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IMA, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

EGFR mutations represent one of the major somatic mutations in lung adenocarcinoma and are a therapeutic target in advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Several randomized phase III trials have demonstrated their clinical advantage over cytotoxic chemotherapy agents.9, 10 However, the oncological significance of EGFR mutation status in stage I lung adenocarcinoma is controversial.11 We retrospectively reviewed completely resected lung adenocarcinoma cases and evaluated the prognostic significance of EGFR mutation status with respect to specific histological features.

Although previous studies have shown that EGFR mutations are of significant prognostic value in lung adenocarcinoma, these studies included various histologic subtypes or pStage.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Systematic meta‐analyses have shown that EGFR mutation status is not a prognostic factor in patients with surgically resected NSCLC.11 Kobayashi et al. demonstrated that positive EGFR mutation status correlates with growth in early‐stage lung adenocarcinoma cases with a ground‐glass component of ≥ 50%.19 This report supports the unfavorable effects of EGFR mutation status in early‐stage lung adenocarcinoma. However, studies limited to stage I cases indicated better prognostic tendencies in patients with EGFR mutations20, 21, 22 which contrasts with our results. The discrepancy can be explained as follows. The frequency of EGFR mutations is higher in adenocarcinoma with a concomitant lepidic component (formerly known as a bronchioloalveolar carcinoma component).23, 24, 25 Previous studies did not consider histological subtypes or negative prognostic factors, such as pleural, lymphatic, and vascular invasion in their analyses.12, 20, 21, 22, 26, 27 AIS and MIA are constantly accompanied by the lepidic component and their distributions is higher in stage I. Thus, EGFR mutation in stage I adenocarcinoma is likely to be AIS or MIA. On the contrary, EGFR wild‐type tumors are likely to be invasive adenocarcinoma cases without a lepidic component, and therefore, more often accompanied by pleural and/or lymphovascular invasion. Without considering histological subtypes, comparing EGFR mutation positive to wild‐type cases is akin to comparing noninvasive or preinvasive cases to invasive tumors. In a cohort with extremely high five‐year OS of 98% and a low rate of EGFR mutations (20.2%),20 most cases harboring EGFR mutations might be AIS and MIA. AIS and MIA were first described in the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification5 and are free from recurrence after complete resection.28, 29 They must be considered separate from invasive adenocarcinoma as so in the newly revised TNM staging: Tis (AIS) and T1a(mi) (MIA).4 When evaluating recurrence risk in pN0M0 cases, it is important to exclude cases that are curable by complete resection. IMA should likewise be excluded from such analyses because this subtype is a variant of invasive adenocarcinoma5 that is moderately to highly malignant30, 31 but does not harbor EGFR mutations.30, 32, 33 Cases with relatively high malignancy that do not harbor EGFR mutations are not suitable for inclusion in analyses of the prognostic impact of EGFR mutation status. In fact, the proportion of EGFR mutation‐positive cases among AIS and MIA were high, while the recurrence rate of IMA was not particularly low (n = 2, 18.2%) in this study. Thus, the prognostic significance of EGFR mutations is underestimated unless AIS, MIA, and IMA are excluded. The more IMA cases included, the poorer the OS and RFI of the EGFR mutation‐negative cohort.

Apart from the histological distinctions, another reason for the discrepancy in results between previous studies and our study is the different methodology employed to estimate the prognostic impact. We employed OS and RFI as prognostic parameters. In the latter, non‐cancer‐specific deaths were censored. RFI censoring of deaths from causes other than lung cancer is preferable to directly estimate oncological impact. OS usually includes death from a non‐cancer‐specific event. A previous study included six patient deaths as prognostic events for OS15 however, five of them were EGFR wild‐type carriers who died without experiencing recurrence. Additionally, OS is generally improved in EGFR mutation‐positive cases after receiving EGFR‐TKIs.13, 34 Previous studies concluded that EGFR mutation is a favorable prognostic indicator and suggest that OS is prolonged by EGFR‐TKIs.14, 15, 16, 22 In summary, the distribution of EGFR mutation and potential curability varies considerably among sub‐histologies. The therapeutic effect of TKIs must be excluded to precisely estimate the prognostic impact of EGFR mutation. Thus, we report contradictory results on the prognostic impact of EGFR mutation compared to those in published literature.

In addition to distinguishing histological subtypes and utilizing cancer‐specific parameters, ethnic characteristics may also account for our results. The frequency of EGFR mutations is reported to be higher among Asian populations; some studies have reported incidence as high as 40–60%.1, 2 Conversely, the frequency of EGFR mutations in non‐Asian populations is reported to be lower, at 10–20%.35, 36 Among the latter populations, the significance of EGFR mutation status may be weaker, and another somatic mutation or a combination of several genetic aberrations may be important to estimate prognosis. Thus, ethnicities should also be taken into account in such analyses.

This study has some limitations, including its retrospective, single‐institutional design and limited sample size. The inclusion of cases with multiple tumors or those treated by wedge resection might be also a weakness of this study. Although second primary tumors and metastases in cases with multiple tumors were diagnosed according to the IASLC proposals, the absolute methodology with solid evidence to distinguish second primary from metastasis has not yet been established. In all wedge resection cases, although the potential of metastatic lymph nodes was excluded intraoperatively as well as preoperative CT/PET‐CT, pathological confirmation by systematic or lobe‐specific lymphadenectomy is preferred. Large‐scale prospective studies examining several genetic variations at multiple institutions are therefore warranted. As a clinical background, patients undergoing lobectomy or segmentectomy who have undergone adequate lymph node dissection are preferable.

In conclusion, EGFR mutations are associated with recurrence in pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma, particularly in types other than AIS, MIA, and IMA. The ratio of EGFR mutation and the risk of recurrence vary among histological subtypes. EGFR mutation status should be considered together with histological subtype when estimating the risk of recurrence in resected pN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. PCR conditions and oligonucleotide sequences for peptide nucleic acid (PNA)‐locked nucleic acid (LNA) PCR clamp method.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially conducted at the Analysis Center of Life Science, Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development, Hiroshima University (Hiroshima, Japan) and was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI grant number 15K19938). We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

References

- 1. Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: Biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 8919–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takano T, Ohe Y, Sakamoto H et al Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and increased copy numbers predict gefitinib sensitivity in patients with recurrent non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 6829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene and related genes as determinants of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sensitivity in lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 1817–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J et al The IASLC lung cancer staging project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11: 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M et al International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 244–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Franklin WA et al The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Summary of proposals for revisions of the classification of lung cancers with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11: 639–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Detterbeck FC, Franklin WA, Nicholson AG et al The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Background data and proposed criteria to distinguish separate primary lung cancers from metastatic foci in patients with two lung tumors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11: 651–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagai Y, Miyazawa H, Huqun et al Genetic heterogeneity of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non‐small cell lung cancer cell lines revealed by a rapid and sensitive detection system, the peptide nucleic acid‐locked nucleic acid PCR clamp. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 7276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R et al Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first‐line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open‐label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y et al Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Z, Wang T, Zhang J et al Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in resected non‐small cell lung cancer: A systematic review with meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9: e106053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee YJ, Park IK, Park MS et al Activating mutations within the EGFR kinase domain: A molecular predictor of disease‐free survival in resected pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009; 135: 1647–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kudo Y, Shimada Y, Saji H et al Prognostic factors for survival after recurrence in patients with completely resected lung adenocarcinoma: Important roles of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status and the current staging system. Clin Lung Cancer 2015; 16: e213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim YT, Seong YW, Jung YJ et al The presence of mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor gene is not a prognostic factor for long‐term outcome after surgical resection of non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. D'Angelo SP, Janjigian YY, Ahye N et al Distinct clinical course of EGFR‐mutant resected lung cancers: Results of testing of 1118 surgical specimens and effects of adjuvant gefitinib and erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7: 1815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim HR, Shim HS, Chung JH et al Distinct clinical features and outcomes in never‐smokers with nonsmall cell lung cancer who harbor EGFR or KRAS mutations or ALK rearrangement. Cancer 2012; 118: 729–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marks JL, Broderick S, Zhou Q et al Prognostic and therapeutic implications of EGFR and KRAS mutations in resected lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3: 111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Onozato R, Kuwano H, Mitsudomi T. Prognostic implication of EGFR, KRAS, and TP53 gene mutations in a large cohort of Japanese patients with surgically treated lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2009; 4: 22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobayashi Y, Mitsudomi T, Sakao Y, Yatabe Y. Genetic features of pulmonary adenocarcinoma presenting with ground‐glass nodules: The differences between nodules with and without growth. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Izar B, Sequist L, Lee M et al The impact of EGFR mutation status on outcomes in patients with resected stage I non‐small cell lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96: 962–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobayashi N, Toyooka S, Ichimura K et al Non‐BAC component but not epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation is associated with poor outcomes in small adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3: 704–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ohba T, Toyokawa G, Kometani T et al The mutations of the EGFR and K‐ras genes in resected stage I lung adenocarcinoma and their clinical significance. Surg Today 2014; 44: 478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sonobe M, Manabe T, Wada H, Tanaka F. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor gene are linked to smoking‐independent, lung adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2005; 93: 355–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsumoto S, Iwakawa R, Kohno T et al Frequent EGFR mutations in noninvasive bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 2498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blons H, Côté JF, Le Corre D et al Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in lung cancer are linked to bronchioloalveolar differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 1309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Ding K et al Prognostic and predictive value of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase domain mutation status and gene copy number for adjuvant chemotherapy in non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 139–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu WS, Zhao LJ, Pang QS, Yuan ZY, Li B, Wang P. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in resected lung adenocarcinomas. Med Oncol 2014; 31: 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ito M, Miyata Y, Kushitani K et al Prediction for prognosis of resected pT1a‐1bN0M0 adenocarcinoma based on tumor size and histological status: Relationship of TNM and IASLC/ATS/ERS classifications. Lung Cancer 2014; 85: 270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yanagawa N, Shiono S, Abiko M, Ogata SY, Sato T, Tamura G. New IASLC/ATS/ERS classification and invasive tumor size are predictive of disease recurrence in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 612–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shim HS, Kenudson M, Zheng Z et al Unique genetic and survival characteristics of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 1156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoshizawa A, Sumiyoshi S, Sonobe M et al Validation of the IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification for prognosis and association with EGFR and KRAS gene mutations: Analysis of 440 Japanese patients. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Watanabe H, Saito H, Yokose T et al Relation between thin‐section computed tomography and clinical findings of mucinous adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99: 975–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hwang DH, Sholl LM, Rojas‐Rudilla V et al KRAS and NKX2‐1 mutations in invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11: 496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lv C, An C, Feng Q et al A retrospective study of stage I to IIIa lung adenocarcinoma after resection: What is the optimal adjuvant modality for patients with an EGFR mutation? Clin Lung Cancer 2015; 16: e173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barlesi F, Mazieres J, Merlio JP et al Routine molecular profiling of patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Results of a 1‐year nationwide programme of the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup (IFCT). Lancet 2016; 387: 1415–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C et al Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 958–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. PCR conditions and oligonucleotide sequences for peptide nucleic acid (PNA)‐locked nucleic acid (LNA) PCR clamp method.