Background

Nivolumab is an anti‐PD‐1 blocking monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, some patients on immunotherapy may experience rapid progression and worsening clinical status, known as hyperprogressive disease. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records of patients with NSCLC administered nivolumab therapy at Toneyama National Hospital, Japan, from January 2016 to January 2018. Of the 87 patients administered nivolumab therapy, five experienced rapid progression during one cycle of nivolumab therapy. Four patients were treated with corticosteroids to overcome their symptomatic events. Nivolumab exhibited efficacy after temporal progression, so‐called “pseudoprogression”, in three patients, and their symptoms and laboratory results improved. In the other patient, pleural and pericardial effusions increased after nivolumab therapy, and drainage was required, with no subsequent recurrence. The clinical courses of our case series indicate that alternative treatment, namely high‐dose corticosteroids, antibiotics, and drainage, effectively treated the symptoms of rapid tumor progression. Of note, corticosteroids suppressed the temporary inflammatory reaction to nivolumab. Although hyperprogressive disease is thought to be associated with poor quality of life and survival, these treatment strategies may be useful in patients with expected responses to immunotherapy.

Keywords: Programmed death‐1 ligand, immune check point inhibitor, immunotherapy, pseudoprogression, rapid progression

Introduction

PD‐1 is a receptor expressed on the surface of activated T cells, which binds to its ligands, PD‐L1 and PD‐L2. Engagement of PD‐1 by its ligands suppresses T cell function by inducing T cell apoptosis, anergy, exhaustion, and the production of immune suppressive cytokines.1, 2 A blockade of the PD‐1/PD‐L1 pathway restores effector T cell function and enhances anti‐tumor immune responses.3 Nivolumab is a fully human immunoglobulin G4 anti‐PD‐1 blocking monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Randomized phase III studies, CheckMate‐017 and CheckMate‐057, showed superior efficacy and tolerability of nivolumab over docetaxel in patients with NSCLC with disease progression following platinum‐containing chemotherapy.4, 5

Some patients on immunotherapy may experience a rapid deterioration in clinical status, termed hyperprogressive disease (HPD), which appears to negatively impact survival.6, 7 Herein, we describe five cases of HPD that occurred during one cycle of nivolumab therapy. The focus of this case series was on the management required to overcome these serious events.

Case report

Case 1

A 69‐year‐old man underwent concurrent chemoradiotherapy for stage IIIB squamous cell carcinoma from March to May 2015. The primary lung tumor recurred, and nivolumab was administered as second‐line chemotherapy in May 2016.

After nivolumab therapy, the patient began to complain of dyspnea. Oxygenation status and symptoms began to rapidly deteriorate, and tumor progression was observed on chest X‐ray. After two cycles of nivolumab therapy, computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed distinct disease progression. Carboplatin plus nab‐paclitaxel was administered as third‐line chemotherapy.

However, his symptoms and laboratory data deteriorated further, and a diagnosis of severe pneumonia was made. Levofloxacin and high‐dose corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/body for 3 days) were intravenously administered and oral prednisolone (1.0 mg/kg) was continued. The patient experienced symptomatic improvement, after which the prednisolone was gradually tapered every three days. The tumor propensity score (TPS) of PD‐L1 was negative (0%).

Case 2

An 83‐year‐old man was diagnosed with stage IIIA pleomorphic carcinoma (PC) of the lung in August 2015. He could not undergo curative radiotherapy because of a wide irradiation range. After first, second, and third‐line cytotoxic chemotherapy with docetaxel, pemetrexed, and vinorelbine, respectively, left‐sided pleural effusion emerged. Subsequently, nivolumab was administered as fourth‐line chemotherapy in October 2016.

Three days after commencing nivolumab therapy, the pleural effusion increased, and pericardial effusion was observed; subsequent drainage of these two sites was required. However, chest X‐ray imaging showed reduction of the lung tumor, and the pleural and pericardial effusions did not recur after drainage. CT images revealed a partial response to therapy, as evidenced by tumor shrinkage (Fig 1). Nivolumab therapy was continued for over 40 cycles. The TPS of PD‐L1 was 60–70%.

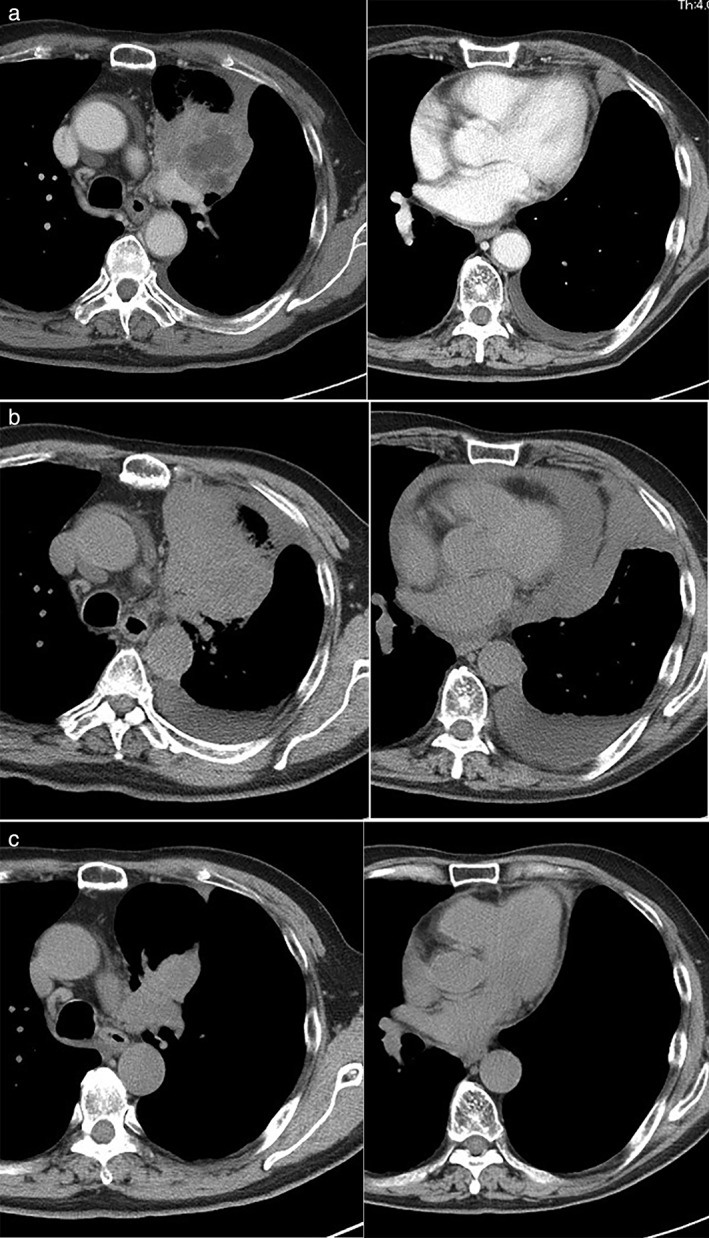

Figure 1.

(a) Chest computed tomography (CT) imaging showed a tumor in the left upper lobe and the presence of a pleural effusion. (b) Three days after the first administration of nivolumab, the pleural effusion and pericardial effusion progressed. (c) After chest and pericardial drainage, chest CT imaging showed tumor shrinkage in the lung, and no recurrence of either the pleural or pericardial effusion.

Case 3

A 74‐year‐old woman was diagnosed with stage IVA PC of the lung in April 2017 after cytological examination. Carboplatin plus pemetrexed was administered as first‐line chemotherapy. After six cycles of chemotherapy, primary tumor progression and pulmonary metastasis were noted. While two cycles of a combination of tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil (S‐1) were administered, CT imaging revealed worsening of each of the lesions. Nivolumab was administered as third‐line chemotherapy in November 2017.

After nivolumab therapy, the patient developed a fever and there was a significant increase in her C‐reactive protein (CRP) level. Although antibiotic therapy was subsequently administered, fever and laboratory data worsened on day 10 of nivolumab therapy (CRP 14.05 mg/dL, procalcitonin [PCT] 0.23 ng/mL). CT imaging revealed progression of each pulmonary tumor and metastasis, but interstitial pneumonia had not developed. Meropenem and high‐dose corticosteroids (dexamethasone 8 mg/body for 4 days) were intravenously administered to treat severe pneumonia. Subsequently, oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg) was continued. Her symptoms and laboratory data improved (CRP 5.16 mg/dL, PCT 0.08 ng/mL on day 21; CRP 0.20 mg/dL, PCT 0.05 ng/mL on day 44) and the prednisolone dosage was gradually tapered every two weeks. CT imaging revealed tumor shrinkage for a partial response, known as “pseudoprogression” (Fig 2). Although nivolumab therapy was not continued, the lesions were stable for more than six months. The TPS of PD‐L1 is unknown in this case.

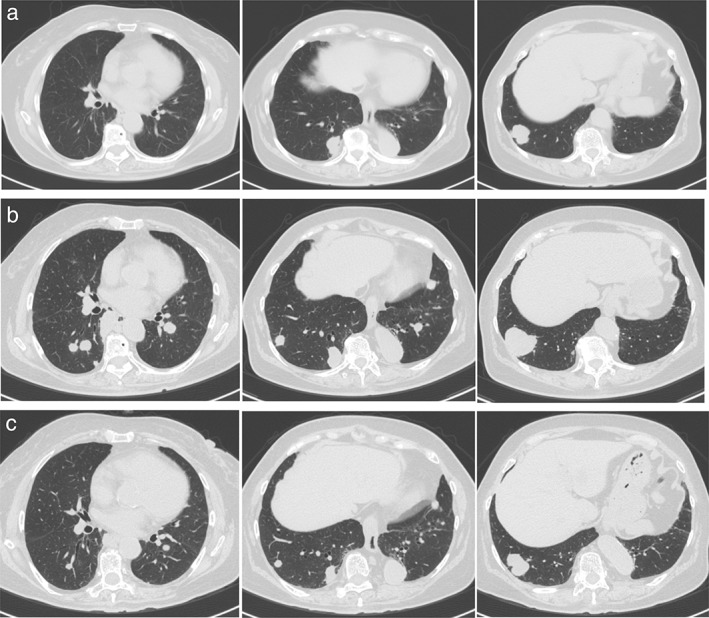

Figure 2.

(a) Chest computed tomography (CT) imaging showed tumors in the right lower lobe before nivolumab therapy. (b) Ten days after the first administration of nivolumab, each tumor increased in size and new pulmonary metastasis emerged in the bilateral lung. (c) After administration of high‐dose corticosteroids, and subsequent gradual tapering of prednisolone, chest CT imaging showed tumor shrinkage in the lung.

Case 4

A 53‐year‐old woman was diagnosed with stage IVB adenocarcinoma in August 2017. Carboplatin plus pemetrexed was administered as first‐line chemotherapy. During second‐line chemotherapy (docetaxel and ramucirumab), bone metastases progression was observed, for which the patient underwent palliative radiotherapy in the thoracic vertebrae. Nivolumab was subsequently administered as third‐line chemotherapy in January 2018.

After one cycle of nivolumab therapy, chest X‐ray and CT imaging showed distinct progression of the lung tumors. CRP levels were significantly elevated (14.06 mg/dL on day 15), but she had no symptoms of infection. Prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg) was administered, after which the CRP level improved (10.56 mg/dL on day 22) and shrinkage of the lung tumor was evident on chest X‐ray (Fig 3). Prednisolone was gradually tapered and nivolumab therapy was continued over six cycles. The TPS of PD‐L1 was 1–5%.

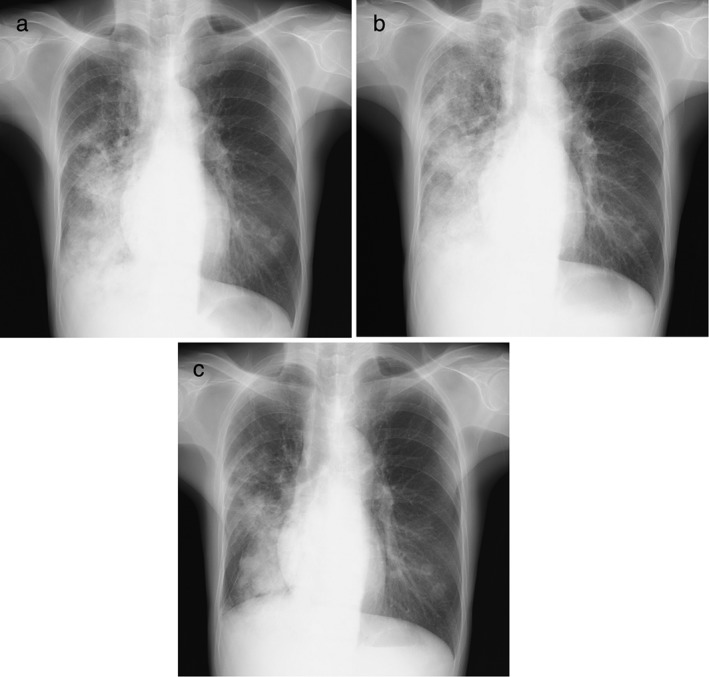

Figure 3.

(a) Chest X‐ray showed tumors in the middle and right lower lung fields before nivolumab therapy. (b) Chest X‐ray showed distinct progression of the lung tumors on day 15 of nivolumab administration. (c) After administration of prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg), chest X‐ray showed shrinkage of the lung tumor 22 days after initial nivolumab administration.

Case 5

An 80‐year‐old man was diagnosed with stage IVB squamous cell carcinoma in June 2017. Carboplatin plus nab‐paclitaxel was administered as first‐line chemotherapy. After four cycles of chemotherapy, progression of the primary tumor and pulmonary metastasis and lymphangiomatosis were observed. Nivolumab was administered as second‐line chemotherapy in January 2018.

After one cycle of nivolumab therapy, chest X‐ray and CT imaging showed distinct progression of the lung tumors and lymphangiomatosis. Dyspnea, oxygenation status, and symptoms worsened, and levofloxacin and high‐dose corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 500 mg/body for 3 days) were subsequently intravenously administered. Oral prednisolone (1.0 mg/kg) was continued and gradually tapered. Although the lymphangiomatosis slightly improved, dyspnea and oxygenation status gradually deteriorated. S‐1 was administered as third‐line chemotherapy, however, there was no symptomatic improvement, and distinct progression of the lung tumors was evident on CT imaging. The TPS of PD‐L1 was negative (0%).

Discussion

Immunotherapy can result in improved quality of life and a durable response in patients with NSCLC. However, approximately 10% of patients experience an aggressive pattern of accelerated progression,6 and predictors of HPD have not yet been identified. The inflammatory response, comprising activated cytotoxic lymphocytes or apoptosis‐promoting proteins, is increased in the tumors of patients with pseudoprogression.8, 9 To distinguish pseudoprogression from HPD before imaging surveillance, repeat biopsies should be considered. For other predictive markers, tumor progression was rapid and performance status (PS) worsened in response to nivolumab therapy in cases 1 and 5 (Table 1). In a recent study, poor PS predicted poor efficacy of nivolumab therapy.10 Physicians must be aware of poor PS or rapid tumor progression before commencing nivolumab therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases

| Age | Gender | ECOG PS | Histology | Brinkman Index | Lines of Therapy | Nivolumab Courses | TPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 69 | M | 2 | SQ | 2000 | 2 | 2 | < 1% |

| Case 2 | 83 | M | 1 | PC | 1200 | 4 | 40 (ongoing) | 60–70% |

| Case 3 | 74 | F | 1 | PC | 0 | 3 | 1 | Unknown |

| Case 4 | 53 | F | 1 | AD | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1–5% |

| Case 5 | 80 | M | 2 | SQ | 900 | 2 | 1 | < 1% |

AD, adenocarcinoma; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status at the start of nivolumab therapy; PC, pleomorphic carcinoma; SQ, squamous cell carcinoma; TPS, tumor propensity score from immunohistochemistry using a rabbit antihuman PD‐L1 antibody.

This case series indicates that several types of treatment, namely high‐dose corticosteroid therapy, antibiotic therapy, and drainage, effectively treated the symptoms of rapid tumor progression. Of note, corticosteroid therapy is beneficial for the management of inflammatory reactions, such as fever or CRP elevation (cases 3 and 4). In case 3, CT imaging revealed a partial response (tumor shrinkage) after prednisolone therapy; however, nivolumab was not administered thereafter. This pattern of progression might be a temporary inflammatory reaction, resembling a tumor flare, known as so‐called pseudoprogression.8 In case 1, symptomatic improvement was observed after high‐dose corticosteroid therapy and chemotherapy after nivolumab therapy. A recent report indicated a response to chemotherapy subsequent to exposure to immunotherapy11 this might indicate a potential synergistic effect. If the pivotal symptoms of HPD can be controlled, a clinical response to immunotherapy might be achieved later.

A previous study showed TPS of PD‐L1 and PD‐L2 of approximately 90% in PCs of the lung.12 We have reported that clinical responses were achieved in patients with PCs expressing PD‐L1.13 In the present case series, a long‐term response to immunotherapy could be maintained after HPD in patients with PC of the lung (cases 2 and 3). For patients in whom a response to immunotherapy could be expected (as evidenced by tissue type, high mutation burden, or PD‐L1 expression), aggressive treatment strategies may be considered for the pivotal events.14, 15, 16

Hyperprogressive disease is thought to be associated with poor quality of life and survival. However, a response with tumor shrinkage was achieved in some cases, and we were able to overcome severe symptoms. Specifically, the clinical courses of our case series indicate that corticosteroid therapy could suppress the temporary inflammatory reaction, leading to pseudoprogression. Further studies are required to identify useful biomarkers of delayed therapeutic outcomes in order to distinguish between true HPD and temporary disease progression.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 252–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD‐1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2008; 26: 677–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okazaki T, Honjo T. PD‐1 and PD‐1 ligands: From discovery to clinical application. Int Immunol 2007; 19: 813–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P et al Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous‐cell non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borghaei H, Paz‐Ares L, Horn L et al Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1627–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Champiat S, Dercle L, Ammari S et al Hyperprogressive disease is a new pattern of progression in cancer patients treated by anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 1920–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ledford H. Promising cancer drugs may speed tumours in some patients. Nature 2017; 544: 13–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiou VL, Burotto M. Pseudoprogression and immune‐related response in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3541–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Giacomo AM, Danielli R, Guidoboni M et al Therapeutic efficacy of ipilimumab, an anti‐ctla‐4 monoclonal antibody, in patients with metastatic melanoma unresponsive to prior systemic treatment: Clinical and immunological evidence from three patient cases. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009; 58: 1297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taniguchi Y, Tamiya A, Isa S et al Predictive factors for poor progression‐free survival in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Anticancer Res 2017; 37: 5857–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schvartsman G, Peng SA, Bis G et al Response rates to single‐agent chemotherapy after exposure to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2017; 112: 90–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim S, Kim MY, Koh J et al Programmed death‐1 ligand 1 and 2 are highly expressed in pleomorphic carcinomas of the lung: Comparison of sarcomatous and carcinomatous areas. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: 2698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanazu M, Uenami T, Yano Y et al Case series of pleomorphic carcinomas of the lung treated with nivolumab. Thorac Cancer 2017; 8: 724–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R et al Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non‐small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2018–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz‐Ares L et al First‐line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2415–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A et al Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2093–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]