Abstract

Digital health interventions have been associated with reduced rescue inhaler use and improved controller medication adherence. This quality improvement project assessed the benefit of these interventions on asthma-related healthcare utilizations, including hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) utilization and outpatient visits. The intervention consisted of electronic medication monitors (EMMs) that tracked rescue and controller inhaler medication use, and a digital health platform that presented medication use information and asthma control status to patients and providers. In 224 study patients, the number of asthma-related ED visits and combined ED and hospitalization events 365 days pre- to 365 days post-enrollment to the intervention significantly decreased from 11.6 to 5.4 visits (p < 0.05) and 13.4 to 5.8 events (p < 0.05) per 100 patient-years, respectively. This digital health intervention was successfully incorporated into routine clinical practice and was associated with lower rates of asthma-related hospitalizations and ED visits.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Delivery of health care, Pulmonary medicine, Asthma, Digital health

Introduction

Treatment paradigms for asthma management have been established and accepted [1]. Implementation of the guideline recommendations, however, has been suboptimal due to inconsistent and inadequate assessment of adherence to treatments and reporting of disease control [2]. Additionally, guideline implementation may be hindered by the intermittent nature of asthma symptoms, patient concern about potential adverse effects of therapy, and medication cost [3]. Inadequate adherence may result in patients failing to achieve asthma control [2].

Studies have shown that digital health interventions improve asthma control, reduce use of short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) “rescue” medications, increase the number of days without SABA use and improve adherence to controller medications [4–6]. A pragmatic trial demonstrated a significant reduction in SABA use and an increase in SABA-free days when SABA was monitored with electronic medication monitors (EMMs), and patients and their health care providers (HCPs) received feedback about medication use [7]. This subsequent quality improvement project was implemented to assess the impact of the digital health intervention on healthcare utilization in an open, single-arm study.

Methods

Patients were enrolled from September 2014 to November 2017 during routine asthma care in specialty and primary care clinics. Inclusion criteria included provider diagnosis of asthma, prescription for SABA, Spanish or English fluency, and absence of other pulmonary disease or significant co-morbidity. Patients were prescribed medications according to standard guideline practice. Those who enrolled in a prior EMM clinical trial at Dignity Health were excluded [7].

Patients were provided digital EMMs (Propeller Health, Madison, WI) that attached to both controller and SABA inhaled medication(s). EMMs recorded date, time and number of puffs taken. The EMMs are part of a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 510(k) cleared digital health platform consisting of mobile applications, web-based dashboards, and communication channels such as text messaging and email.

Patients authorized their HCPs to view their reports through a web interface, enabling them to integrate real-time information on SABA use and controller adherence into clinical decision-making [7].

Healthcare utilization information was collected from Dignity Health claims data for hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits and outpatient visits. These events were identified as asthma-related when specific codes (ICD9 493.XX or ICD10 J45.XX) were present in the primary billing position. Rate differences and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated to assess the change in pre-post utilization for ED visits, hospitalizations, combined ED visits plus hospitalizations, and outpatient visits, and p-values were calculated using Wilcoxon signed rank tests. For patients prescribed both SABA and controller medications, the controller-to-total medication ratio, defined as the number of controller medication puffs recorded divided by the total number of puffs of SABA plus controller medications, was calculated [8]. Patients were observed for 365 data days pre- and post-enrollment.

Results

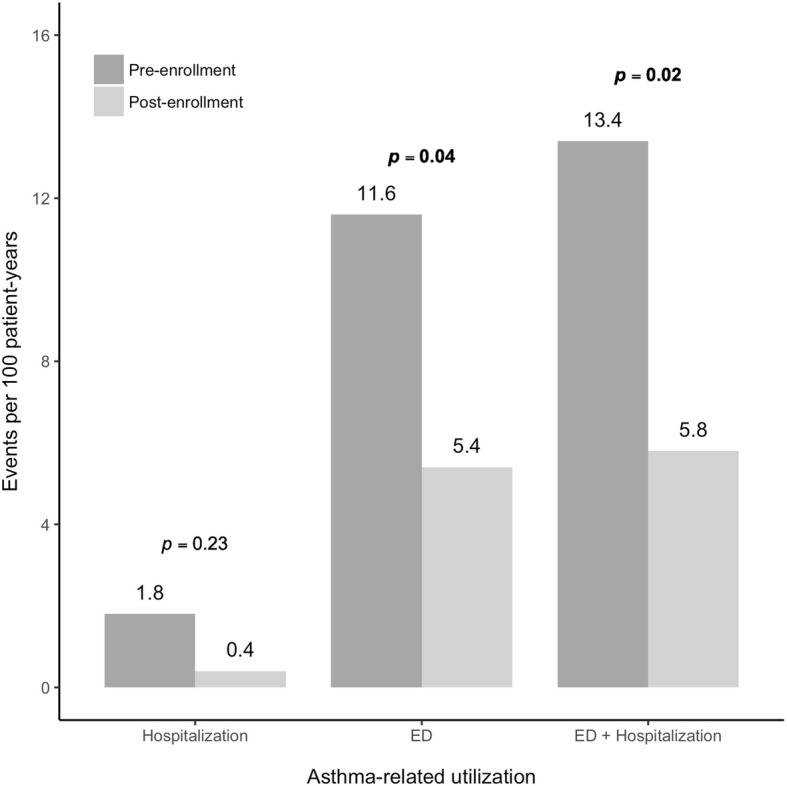

Participants (n = 224) were 57% female with a mean age of 33 years (Table 1). Asthma-related healthcare utilization data are reported for the pre- and post-enrollment years (Table 2; Fig. 1). From the pre- to post-enrollment year, asthma-related hospitalizations, ED visits, and combined ED and hospitalization events declined by 1.3 (95% CI, − 0.6, 3.3, p = 0.23), 6.0 (95% CI, 0.9, 11.6, p = 0.04), and 7.6 (95% CI, 1.9, 13.3, p = 0.02) events per 100 patient-years, respectively. Outpatient visits per patient for asthma increased by 2.6 (95% CI, 2.2, 2.9) visits per patient-year (p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Patient characteristics | n = 224 |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) years | 33 (23) |

| Age Range (years) | 3–88 |

| Female [n (%)] | 128 (57) |

| Adults (18+) [n (%)] | 132 (59) |

| Medication type [n (%)] | |

| SABA only | 50 (30) |

| Controller only | 2 (1) |

| Both SABA and controller | 172 (69) |

| Controller type [n (%)] | |

| ICS | 119 (53) |

| ICS/ LABA | 38 (17) |

Table 2.

Pre- versus post-enrollment year rates (95% confidence intervals) in asthma-related utilization

| Pre-enrollment | Post-enrollment | Rate Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations | 1.8 (0.5, 4.6) | 0.4 (0.01, 2.5) | 1.3 (−0.6, 3.3) |

| Emergency department (ED) visits | 11.6 (1.6, 17.0) | 5.4 (2.8, 9.4) | 6.3 (0.9, 11.6) |

| ED + Hospitalizations | 13.4 (9.0, 19.1) | 5.8 (3.1, 9.2) | 7.6 (1.9, 13.3) |

Fig. 1.

Asthma-related utilization rates pre-enrollment (dark gray) and post-enrollment (light gray) in the digital health intervention

Mean SABA use declined significantly from 0.68 puffs/day during week 1 to 0.16 puffs/day at week 52 (− 0.52 [95% CI, − 0.69, − 0.34]; p < 0.05). Among patients on controller medications (n = 76), the controller-to-total medication ratio improved during the same time points, increasing from 0.66 to 0.82 (0.16 [95% CI, 0.07, 0.25]; p < 0.01) (Table 3) reflecting a shift from rescue to controller use.

Table 3.

Inhaler use improvements from week 1 to 52 following enrollment in the digital health intervention

| Week 1 | Week 52 | Difference | Percent change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SABA puffs/day | 0.68 | 0.16 | 0.52 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.69)* | + 76% |

| Controller-to-total medication ratio | 0.66 | 0.82 | −0.16 (95% CI: − 0.25, − 0.07)* | − 24% |

*p < 0.01

Discussion

This quality improvement project utilized a digital health intervention that provided both patients and HCPs with information about asthma medication use to inform treatment decision-making. Implementation of the program resulted in a significant decrease in asthma-related ED visits and combined ED visits and hospitalizations. The decrease in asthma-related utilization events post-intervention was consistent with the decrease in use of SABA, and was associated with a higher asthma medication ratio, a metric associated with improved asthma outcomes and lower healthcare utilization [8]. Pre-enrollment rates of asthma-related hospitalizations and ED visits were consistent with published data from commercial health plans [9]. The increase in outpatient visits noted during the study may reflect program enrollment, or greater patient and HCP awareness of asthma.

These data allow both patients and HCPs to better assess whether treatment is achieving the predetermined goals of asthma control. If treatment goals were not achieved, patients and providers could determine whether to focus on better adherence or consider other treatment options. Increased adherence has been linked to reduced high-cost utilization. In one study, every 25% improvement in adherence was associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED event [10].

As a single-arm quality improvement project, the results need to be cautiously interpreted because of the Hawthorne effect (i.e. confounding by regression to the mean) and potential for temporal confounding that can bias the observed estimations. Nonetheless, the correlation of reduced SABA use, improved controller-to-total medication ratio and decreased asthma-related healthcare utilization present a set of consistent findings for this quality improvement project.

In conclusion, this analysis demonstrated that digital health interventions can be incorporated into routine clinical practice, and their use may contribute to improved outcomes including reduced healthcare utilization and reduced SABA use. The information collected by the EMMs, and shared with both patients and HCPs, can promote self-management and support personalized clinical care to achieve better asthma outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank to the California Health Care Foundation, as well as the following individuals who supported the work presented: Michael Schatz, Natalie DeWitt, Jesika Riley, Ben Theye, Antara Aiama, Kelly Henderson, Rubina Inamdar, and Bob Quade.

Funding

This work was supported by the California Health Care Foundation, Dignity Health, and Propeller Health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are considered Protected Health Information under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), and as such are only available upon specific authorization of access following HIPAA.

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency department

- EMMs

Electronic medication monitors

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HCP

Health care provider

- HIPPA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LABA

Long-acting Beta Agonist

- SABA

Short-acting Beta Agonist

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

RM: design and acquisition of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. SJS: interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. BGB: interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. MT: analysis, interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. MAB: design and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. RG: interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. LK: interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. DVS: design and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval. DAS: wrote the initial draft, interpretation of data, reviewed and revised content, final approval.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study met the criteria for an Institutional Review Broad (IRB) exemption (IRB Tracking: PRH1–18- 132) according to Copernicus Group IRB. Eligible patients accepted Propeller Heath’s Terms of Use, which informed participants of the possibility of user data being used for research publications in an aggregated, de-identified format [11].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RM reports a one-time honorarium from Propeller Health for his participation in an advisory board meeting.

SJS has served as a consultant to Aerocrine, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiicho Snakyo, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Propeller Health, Roche and Teva.

BGB has nothing to disclose.

MT, RG, LK, and DAS report salary and/or stock options from their employer, Propeller Health.

MAB and DVS report grants from the California Health Care Foundation during the conduct of the study and salary and stock options from their employer, Propeller Health. In addition, they have patents pending that are related but not directly involved in this work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rajan Merchant, Email: rajan.merchant@dignityhealth.org.

Stanley J. Szefler, Email: stanley.szefler@childrenscolorado.org

Bruce G. Bender, Email: benderb@njhealth.org

Michael Tuffli, Email: michael.tuffli@propellerhealth.com.

Meredith A. Barrett, Email: meredith.barrett@propellerhealth.com

Rahul Gondalia, Phone: (+1) 608-251-0470, Email: rahul.gondalia@propellerhealth.com.

Leanne Kaye, Email: leanne.kaye@propellerhealth.com.

David Van Sickle, Email: david@propellerhealth.com.

David A. Stempel, Email: david.stempel@propellerhealth.com

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Jul 17]. Available from: www.ginasthma.org

- 2.Murphy AC, Proeschal A, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord I, Bradding P, et al. The relationship between clinical outcomes and medication adherence in difficult-to-control asthma. Thorax. 2012;67:751–753. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peláez S, Lamontagne AJ, Collin J, Gauthier A, Grad RM, Blais L, et al. Patients’ perspective of barriers and facilitators to taking long-term controller medication for asthma: a novel taxonomy. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:42. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles T, Quinn D, Weatherall M, Aldington S, Beasley R, Holt S. An audiovisual reminder function improves adherence with inhaled corticosteroid therapy in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:811–816. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster J, Lavole K, Boulet L. Treatment adherence and psychosocial factors. Chung K, Bel E, Wenzel S, editors. Difficult-to-treat Sev. Asthma Eur. Respir. Monogr. Sheffield: European Respiratory. Society; 2011.

- 6.Barrett MA, Humblet O, Marcus JE, Henderson K, Smith T, Eid N, et al. Effect of a mobile health, sensor-driven asthma management platform on asthma control. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:415–421.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merchant RK, Inamdar R, Quade RC. Effectiveness of population health management using the propeller health asthma platform: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, Mosen D, Mendoza G, Apter AJ, et al. The controller-to-total asthma medication ratio is associated with patient-centered as well as utilization outcomes. Chest. 2006;130:43–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Most Recent Asthma Data [Internet]. Natl. Curr. Asthma Preval. 2016 [cited 2018 Jul 17]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm

- 10.Delea TE, Stanford RH, Hagiwara M, Stempel DA. Association between adherence with fixed dose combination fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on asthma outcomes and costs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3435–3442. doi: 10.1185/03007990802557344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Propeller Health. User Agreement [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 17]. Available from: https://my.propellerhealth.com/terms-of-service

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are considered Protected Health Information under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), and as such are only available upon specific authorization of access following HIPAA.