Abstract

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is a growing concern in health care. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), forming biofilms, is a common cause of resistant orthopedic implant infections. Gentamicin is a crucial antibiotic preventing orthopedic infections. Silica–gentamicin (SiO2-G) delivery systems have attracted significant interest in preventing the formation of biofilms. However, compelling scientific evidence addressing their efficacy against planktonic MRSA and MRSA biofilms is still lacking, and their safety has not extensively been studied.

Materials and methods

In this work, we have investigated the effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids against planktonic MRSA as well as MRSA and Escherichia coli biofilms and then evaluated their toxicity in zebrafish embryos, which are an excellent model for assessing the toxicity of nanotherapeutics.

Results

SiO2-G nanohybrids inhibited the growth and killed planktonic MRSA at a minimum concentration of 500 µg/mL. SiO2-G nanohybrids entirely eradicated E. coli cells in biofilms at a minimum concentration of 250 µg/mL and utterly deformed their ultrastructure through the deterioration of bacterial shapes and wrinkling of their cell walls. Zebrafish embryos exposed to SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) showed a nonsignificant increase in mortality rates, 13.4±9.4 and 15%±7.1%, respectively, mainly detected 24 hours post fertilization (hpf). Frequencies of malformations were significantly different from the control group only 24 hpf at the higher exposure concentration.

Conclusion

Collectively, this work provides the first comprehensive in vivo assessment of SiO2-G nanohybrids as a biocompatible drug delivery system and describes the efficacy of SiO2-G nanohybrids in combating planktonic MRSA cells and eradicating E. coli biofilms.

Keywords: SiO2, gentamicin, MRSA, antibacterial and antibiofilm effects, nanotoxicity, zebrafish

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is a current hot topic and a significant threat to health care. The antibiotic-resistant bacterium, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), is at the heart of most clinical cases of notorious orthopedic surgery infections.1 S. aureus is also a principal etiological agent of device-related infections and can adhere to the implanted orthopedic devices and then colonize their surfaces forming biofilms.2–4 Biofilms are aggregates of bacterial cells enclosed in a diffuse polymeric matrix.5–8 Biofilm matrix is resistant to the host immune response and antibacterial agents, which has led to the challenge of treating biofilms,2,7,9 to the surgical removal of the implanted device to eliminate the infection,4,6 and to remarkable morbidity and mortality rates of the patients within hospital settings.2 Biofilms also form complex pedestal-like structures, water channels, and pores,8 making them physiologically and morphologically different from their planktonic counterparts.10–12 The different resistance mechanisms of biofilms to antibiotics have been grouped in a previous review7 as follows: 1) the slow penetration of antibiotics into the biofilm matrix; 2) the alteration of the chemical microenvironment within the biofilms, antagonizing the action of antibiotics; and 3) the formation of a highly protected spore-like states by the subbacterial populations of biofilms. Concrete data speaking for the sole responsibility of any of such resistance mechanisms are still lacking.6,13 Furthermore, old biofilms are highly resistant to antibiotics and antibacterial agents.11,14 It has previously been observed that tobramycin (5 µg/mL) kills 97% of the young (2 days) biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after 4 hours treatment. However, even a higher tobramycin concentration (50 µg/mL) kills only 50% of the old (7 days) biofilms.15 Toté et al16 have found that different biocides reduce the number of viable S. aureus and P. aeruginosa cells in biofilms but the matrices of biofilms are not affected. Allan et al17 have shown that killing Escherichia coli cells with commercial disinfectants, in most cases, requires at least double the concentration of disinfectant when the cells were in biofilms compared with that needed for planktonic cells. Choi et al18 have reported a fourfold increase in the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of silver nanoparticles (NPs) required for E. coli cells in biofilms compared with that needed for planktonic cells. Such tenacity of the formed biofilms is the leading cause to remove the infected orthopedic implants and to treat the infections before implanting new devices.19 Consequently, therapeutic modalities that could target the antibiotics, preventing the formation of biofilms, would be an effective way to control them.5

Generally speaking, silica (SiO2)-based formulations could be utilized for the targeted drug delivery and for squelching the intricate multidrug resistance.20,21 More specifically, SiO2 materials could be utilized as local antibiotic delivery systems in orthopedic implants targeting effective antibiotic concentrations in bone tissue and avoiding the drawbacks of systemic antibiotic administrations, like toxicity or limited tissue exposure.3 Aminoglycosides (i.e., gentamicin and kanamycin), glycopeptide antibiotics (i.e., vancomycin), and quinolones (i.e., ciprofloxacin) have broadly been utilized in orthopedic surgery, preventing or treating associated infections.1 There are a large number of published studies on loading antibiotics onto SiO2 materials for the prolonged localized drug delivery applications, as described for gentamicin22–27 and vancomycin.28,29 It has been demonstrated that kanamy-cin-resistant E. coli is susceptible to kanamycin-conjugated SiO2 NPs, though it is resistant to pristine kanamycin, because of the modified antibacterial mechanism of action of kanamycin conjugated to SiO2 NPs.30 However, none of those above studies has investigated the antibiofilm effects of antibiotic-loaded SiO2 NPs against S. aureus biofilms to ascertain their efficacy in orthopedic applications.

In our previous research,27 we have demonstrated better antibacterial effects of silica–gentamicin (SiO2-G) nanohybrids against Bacillus subtilis than Pseudomonas fluorescens or E. coli. However, further research is needed on bacterial strains most commonly involved in orthopedic applications, like S. aureus and their biofilms, to reveal the practical potential of the nanohybrids. Therefore, this study determines the antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids against MRSA and MRSA biofilms, respectively, for promising orthopedic applications. Bacterial motility constitutes a critical virulence factor in bacterial colonization by initiating the contact of bacterial cells with surfaces.8 A recent study31 has paid attention to the role of bacterial morphology in adhesion to immobilized liquid layers under dynamic conditions, advocating the more efficient adhesion of E. coli cells in comparison with that of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, under dynamic conditions, to the flagella of E. coli. Furthermore, the most predominant clinical bacteria involved in orthopedic implant infections belong to the Staphylococcus genus followed by Enterobacteriaceae genus. Infections by Enterobacteriaceae are encountered with implants being surgically incised near to prenieums.32 The well-known genetics and the wealth of other knowledge collected on E. coli support its use as an exemplary model for studying the formation of biofilms.8 Therefore, the present study aims to enhance the understanding of the antibiofilm effects of the SiO2-G nanohybrids by also exploring such effects on E. coli biofilms.

Despite the importance of SiO2-G delivery systems, the safety and risks associated with their use have not been widely documented. Combining in vitro and in vivo toxicological data on nanomaterials, concerning their physicochemical properties, can help in predicting safety when designing nanomaterials.33 However, studies on the subject have been conflicting and mostly restricted to SiO2 NPs. Some studies have shown that SiO2 NPs decrease the viability of different cell lines such as that of human brain microvessel endothelial cells,34 human umbilical vein endothelial cells,35 and human lung epithelial BEAS-2B cells (only at ≥500 µg/mL of positively charged SiO2 NPs with a diameter of ≥100 nm).36 It has also been shown that SiO2 NPs significantly decrease the differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells.37 By contrast, a detailed examination of the toxicity of SiO2 NPs in 19 different cell lines has demonstrated minimal toxicity in all the cell lines tested.38 We have recently defined the in vitro effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids (719±128 nm) on the osteogenesis of human osteoblast-like SaOS-2 cells, detecting a lower expression of the alkaline phosphatase but enhanced mineralization of the extracellular matrix at 250 µg/mL.39 To better control the safety of such delivery systems, it is of paramount importance to couple the in vitro toxicological effects of these engineered nanomaterials with in vivo studies in more complex animal models.40 Zebrafish embryos are an outstanding animal model for screening chemical toxicity and nanotoxicity in vivo due to several advantages: 1) the genome similarity between zebrafish and humans makes the screening relevant to human health; 2) pores (diameter of 0.5–0.7 µm) in zebrafish chorions allow for the permeation of xenobiotics; 3) the transparency of embryos permits microscopic imaging; 4) the survival of embryos in the absence of functional cardiovascular system facilitates accurate cardiotoxicity studies.41 Another crucial aspect making zebrafish embryos an excellent animal model is that they have, similar to human embryos, protruded yolk sacs that supply proteins, lipids, and micronutrients, facilitating the growth of embryos.42 In the context of bone research, the key regulators of bone formation are also similar in zebrafish and mammals, providing a possibility to correlate the findings in zebrafish to mammalian bone metabolism.43–45 Taking advantage of their transparency, chondrocytes and osteoblasts can be conveniently monitored over time.43 Duan et al46 have demonstrated that SiO2 NPs (diameter of 62 nm; 0.1 and 0.2 mg/mL) significantly decrease the hatching rates and increase the mortalities of zebrafish embryos. These previous results, however, differ from those of Sharif et al,47 who did not detect toxic effects for the injected mesoporous SiO2 NPs (diameter of 200 nm; 10 mg/mL) in zebrafish embryos, defining such SiO2 NPs as a suitable delivery system. Therefore, to clarify the nebulous and conflicting toxicity data of SiO2 NPs among in vitro and in vivo studies, we have also studied, in the present work, the in vivo toxic effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids in zebrafish embryos. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the toxic effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids in this experimental model. Drawing upon the present two avenues of research on SiO2-G nanohybrids for safe orthopedic applications, the present study first attempts to demonstrate the antibacterial effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids against planktonic MRSA and their antibiofilm effects against MRSA and E. coli biofilms and second, assesses their in vivo toxic effects in zebrafish embryos.

Materials and methods

Materials

The gentamicin sulfate, tetraethyl orthosilicate (≥99.0%), and ammonium hydroxide (28%–30%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). The MRSA strain (S. aureus subsp. aureus ATCC® 43300™; KWIK-STIK™) was purchased from Microbiologics® (St Cloud, MN, USA) and the E. coli strain (ATCC 11775™) was obtained from VTT Culture Collection. The Calgary biofilm device (CBD), commercially available as the MBEC™ (minimum biofilm eradication concentration) biofilm inoculator with a 96-well base and hydroxyapatite-coated pegs (19131) was purchased from Innovotech Inc. (Edmonton, AB, Canada).

Synthesis of SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine SiO2 NPs

The SiO2-G nanohybrids were prepared according to the procedure used by Corrêa et al.48 Five hundred milligrams of gentamicin sulfate was dissolved in 10 mL of tetraethyl orthosilicate and 20 mL of ammonium hydroxide was then added to the solution, which was subjected to stirring for 20 minutes at ambient temperature until precipitation. Following precipitation, the material was dried overnight at ambient temperature and then ground. The pristine SiO2 NPs were prepared using the same procedure without adding gentamicin sulfate.

Characterization of SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine SiO2 NPs

The prepared materials were then characterized by scanning electron microscope (SEM), zeta potential analyses, transmission electron microscope (TEM), and attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. The SEM analyses were performed to analyze the surface morphology of the materials prepared, using Zeiss Sigma VP SEM with an acceleration voltage of 1.5 kV and a secondary electron detector. Before SEM analyses, the samples were sputter coated with a platinum (Pt) target for 1.5 minutes (yielding a Pt layer of ~8.6 nm thickness), using an Emitech K100X sputter coater. The zeta potential of the materials suspended in deionized water was measured using the SZ-100 nanopartica Zetasizer (Horiba Scientific, Kyoto, Japan) in triplicate. The TEM studies were performed using a Hitachi TEM (H-7650B, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and a JEOL TEM (JEM-2800, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) microscopes with an acceleration voltage of 80 kV and 200 kV, respectively. The size of the pristine SiO2 NPs was analyzed on the obtained TEM images, whereas the size of the SiO2-G nanohybrids was analyzed on the obtained SEM and TEM images, trying to capture less aggregated particles. The size analysis was executed using Fiji ImageJ software. ATR-FTIR was recorded using a Nicolet 380 FT-IR (Thermo Electron Corporation, White Bear Lake, MN, USA) spectrometer, with a resolution of 2 cm−1 and a scan range of 4,000–500 cm−1. The spectra were the means of 64 scans.

Antibacterial and antibiofilm tests

The MRSA and E. coli strains were cultivated aerobically on Luria-Bertani agar overnight at 35°C. The disinfection of the powder form SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin was conducted by UV irradiation (GS Gene Linker® UV Chamber, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) for 90 seconds before the antibacterial and antibiofilm tests. Following disinfection, SiO2-G nanohybrids and gentamicin were suspended and dissolved in sterile deionized water (1 mg/mL), respectively. The suspended SiO2-G nanohybrids were then sonicated for 30 minutes (VWR® Ultrasonic Bath, USC 200 T, power 60 W, ultrasonic frequency 45 kHz), obtaining homogeneous solutions, before the tests. The CBD was used to determine the susceptibilities of the bio-films to the materials tested. A universal neutralizer (1.0 g l-histidine, 1.0 g l-cysteine, and 2.0 g reduced glutathione in 20 mL double distilled water) was prepared, sterilized using a 0.2 µm cellulose acetate membranes, and stored at −20°C. Five milliliters of the prepared universal neutralizer was then added to 200 mL Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) to be further added into the wells of the recovery plates used in the biofilm susceptibility tests.

Agar diffusion assay

The susceptibility tests were conducted on the planktonic MRSA cells following the guidelines described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).49 Briefly, aliquots of 100 µL of MRSA suspension (~1–2×108 colony-forming units [CFUs]/mL) were spread on Mueller–Hinton agar plates. Aliquots of 50 µL of SiO2-G nanohybrids (1 mg/mL) and pristine gentamicin (1 mg/mL and 25 µg/mL) were then dispensed into the 5 mm-diameter wells of the plates. Following overnight incubation of the plates at 35°C, the diameters of inhibition zones (IZs, mm) were measured. Three separate experiments were performed on different days. The results were interpreted following the tables of the CLSI document.50

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and MBC

The MIC of the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin against planktonic MRSA cells was determined using the broth microdilution method following the guidelines of the CLSI.51 Twofold serial dilutions (from 1 mg/mL to 1 µg/mL) of the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin were prepared in MHB in the wells of a microtiter plate. Within 15 minutes of the inoculum preparation (density adjusted to the same turbidity as McFarland standard 0.5), the inoculum was diluted and then inoculated into the wells (10 µL per well), achieving a final bacterial concentration of 5×105 CFU/mL and representing 10% of the volume per well. Uninoculated MHB was used as a negative control, and an MRSA suspension was used as a positive control for growth. The MICs were visually recorded after overnight incubation at 35°C in sealed plastic bags to avoid drying. To detect bacterial eradication by the materials tested, the MBC was detected following the guidelines of the CLSI,52 using the microdilution endpoints. Aliquots of 10 µL of the wells showing the MICs (clear) were spot plated on Mueller– Hinton agar plates. The number of the cultured colonies was used to determine the bactericidal endpoints based on the final inoculum (5×105 CFU/mL) and the rejection values of the tables of the CLSI.52 Two separate experiments were performed on different days.

Biofilm susceptibilities using CBD

Aliquots (150 µL) of MRSA and E. coli dilutions (final bacterial concentrations of ~105–106 CFU/mL) were added into the wells of the 96-well microtiter plates of the MBEC biofilm inoculator, excluding the sterility control wells (only MHB). The peg lids were then inserted into the plates, and the devices were incubated, under dynamic conditions, in a shaking incubator (110 rpm) for 24 hours at 35°C. Specified pegs were removed from the lids, using sterilized pliers, and put into the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate containing MHB (200 µL). The biofilms were detached by shaking for 30 minutes (160 rpm). The biofilm viabilities were then detected by serially diluting and spot plating (20 µL).

Another 96-well microtiter plate was used as the antibacterial challenge plate. The working solutions of the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin were used as 1×, 2×, and 4× of their MICs against planktonic cells of MRSA and E. coli. The concentrations of the SiO2-G nanohybrids tested were 500, 1,000, and 2,000 µg/mL and 250, 500, and 1,000 µg/mL against the biofilms of MRSA and E. coli, respectively. The concentrations of the pristine gentamicin tested were 125, 250, and 500 µg/mL and 7.8, 15.6, and 31.3 µg/mL against the biofilms of MRSA and E. coli, respectively. The contact time with the materials was set as 24 hours in a shaking incubator. A rinse plate was also prepared by adding 200 µL of sterile saline (0.9%) per well. The peg lids containing the biofilms were immersed in saline before and after the antibacterial challenge for 2 minutes, rinsing the dispersed cells from the biofilms.

After the challenge, the MBEC peg lid was transferred to the recovery plate containing 200 µL of the universal neutralizer per well. The pegs were neutralized in the recovery plate for 30 minutes to equilibrate the antibacterial materials tested and the biofilms were detached by shaking (160 rpm) for 30 minutes. Aliquots of 20 µL were serially diluted and spot plated to detect the viable counts per peg using Equation 1. Then, aliquots of 20 µL of fresh MHB medium were added to the wells of the recovery plates, which were then sealed and incubated for another 24 hours at 35°C with shaking (110 rpm). The MBEC was visually detected after the incubation as the minimal concentration of the materials tested eradicating the MRSA biofilms. Two separate experiments were performed on different days. Each separate experiment was performed in triplicate.

| (1) |

X, CFU counted on spot plate; B, volume plated; D, dilution factor.

SEM examination was also executed on the biofilms formed onto the CBD pegs following the standard protocol described by Harrison et al53 with modifications. Briefly, after the antibacterial challenge and rinsing, the desired pegs were broken from the lid by sterilized pliers. The broken pegs were rinsed for 15 minutes in 200 µL sterile saline (0.9%) in the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate, removing the dispersed planktonic cells from the pegs. The pegs were then placed in sterile Eppendorf Tubes (2 mL) and fixed by adding 300 µL of 5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and kept at 4°C for 24 hours. After this fixation, the pegs were washed first with cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, 300 µL, 15 minutes) and second with sterile distilled water (300 µL, 15 minutes). The pegs were postfixed with 1% cacodylate-buffered osmium tetroxide (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 1 hour. The pegs were then dehydrated using increased ethanol concentrations (50%, 70%, 96%, and 100%) and finally acetone (100%), and critical point dried at 1,200 bar pressure at 40°C using liquid CO2. The samples were then mounted on aluminum stubs and sputter coated with a Pt target for 4 minutes (yielding a Pt layer of ~22.8 nm thickness). All the samples were then analyzed using the Zeiss Sigma VP SEM with an acceleration voltage of 1.5 kV and a secondary electron detector.

Zebrafish strain and setup of exposure to SiO2-G nanohybrids

The Tübingen strain of zebrafish (Danio rerio) was used in this study. The ethical approval was obtained from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tsinghua University. The embryos were collected after natural spawning of adults maintained at the light:dark photoperiods of 14:10 hours and incubated in Holtfreter’s medium at 28°C±2°C. The embryonic developmental stages were defined as previously reported by Kimmel et al.54 The collected embryos were placed in Petri dishes and examined by a stereomicroscope, removing dead embryos. The sterilization of the powder form SiO2-G nanohybrids was conducted by 60Co irradiation at a dose of 10 kGy before the in vivo experiments. At 4 hours post fertilization (hpf), the embryos were divided into three groups (30 embryos per group), and each group was placed into a separate well of a 6-well culture plate. The first group was exposed to pure Holtfreter’s medium (3 mL, with no test materials) and used as a negative control. The second and third groups were exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids in Holtfreter’s medium at concentrations of 500 and 1,000 µg/mL, respectively. The Holtfreter’s medium (pure and containing the materials tested) was changed every 24 hours until the end of the experiment at 5 days post fertilization (dpf).

Mortality, hatching, and cardiac rates

Zebrafish embryos/larvae were evaluated for the toxic effects of the SiO2-G nanohybrids. The mortality rates were recorded every 24 hours, starting at 24 hpf, as the percentage of dead embryos/larvae of all embryos in the group. The hatching rates were recorded as the percentage of hatched embryos at 72 hpf of all the living embryos in the group. The cardiac rates were detected by counting the beating of ventricles per minute under a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ 1500, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) after being mounted in 3% methylcellulose on the top of a depressed glass slide, starting at 72 hpf. Two separate experiments were performed on different days.

Malformations of embryos/larvae

The malformations of zebrafish embryos/larvae exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids were evaluated and counted every 24 hours, starting at 24 hpf. The malformed embryos/larvae were mounted in 3% methylcellulose on the top of a depressed glass slide, anesthetized by 0.1% tricaine, and captured using a stereomicroscope with Nikon Digital Sight camera (Ds-Ri1, Nikon Corporation). The phenotypic endpoints used to evaluate the malformations were pericardial sacs, yolk, body growth, spine, and tail. For estimating the severity of malformations and toxicity at exposure to the materials tested, the embryos/larvae were scored from 0 to 4 based on the conceptual scaling criteria proposed by Heiden et al55 with a slight modification. The scaling criteria were as follows: 0, absence of malformations; 1, single malformation; 2, two malformations; 3, severe three or more malformations; and 4, lethality. The scoring spectrum (1, 2, and 3; representing various degrees of malformations) values were determined at each time point and then accumulated, forging an average semiquantitative toxicity profile for each exposure group of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (see Supplementary materials). Score 0 represents the normally developed embryos/larvae, and score 4 represents the percentage of mortality. The percentage of malformed embryos/larvae was recorded every 24 hours of the living embryos in the group. An advantage of using the percentage of malformations is to identify the common malformations induced by SiO2-G nanohybrids in comparison with the control group. To achieve this, the percentage of malformation was also determined by dividing the number of embryos/larvae developed a specific type of malformation in the group by the total number of malformed embryos/larvae in all the groups. Two separate experiments were performed on different days.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analyzed using Student’s t-tests (two-tailed, unequal variance) to determine the P-values using Microsoft Excel (Office Professional Plus 2016, Impressa Systems, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Characterization of SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine SiO2 NPs

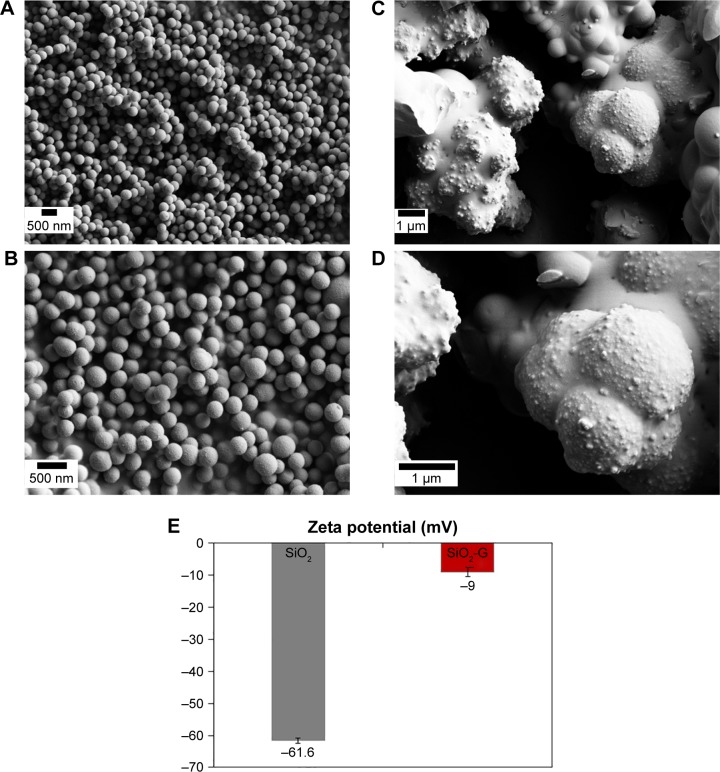

The results obtained from the SEM analyses of the prepared pristine SiO2 NPs and SiO2-G nanohybrids are compared in Figure 1. The pristine SiO2 NPs (Figure 1A and C) demonstrate smooth spherical morphology that differs from the granular rough aggregated network of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (Figure 1B and D). This surface roughness of the SiO2-G nanohybrids validates the loading of gentamicin, providing means for the initial fast gentamicin release demonstrated in our previous study.27 It also matches with previous data that link the rough surfaces with the enhanced antibiotic release,56,57 especially at the initial stages of bone surgery to prevent osteomyelitis.58 The difference between the zeta potentials (surface charges) of the pristine SiO2 NPs and SiO2-G nanohybrids is highlighted in Figure 1E and was detected as −61.6±0.9 mV and −9±1.5 mV, respectively. This decrease in the negative charge of the SiO2-G nanohybrids, compared with that of the pristine SiO2 NPs, is apparently attributed to the loaded gentamicin, suggesting an electrostatic interaction between the positively charged antibiotic and the negatively charged pristine SiO2 NPs. The present results are in accordance with those of Mebert et al59 who found that the most massive amount of positively charged gentamicin was incorporated into the most negatively charged SiO2 NPs by an adsorption process governed by electrostatic interactions.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the materials.

Notes: (A, C) Smooth spherical pristine SiO2 NPs and (B, D) granular rough aggregated network of SiO2-G nanohybrids at the magnifications of 10,000× (A, B) and 20,000× (C, D). (E) The zeta potential of the pristine SiO2 NPs and SiO2-G nanohybrids in deionized water. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Abbreviations: SEM, scanning electron microscope; SiO2 NPs, silica nanoparticles; SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin.

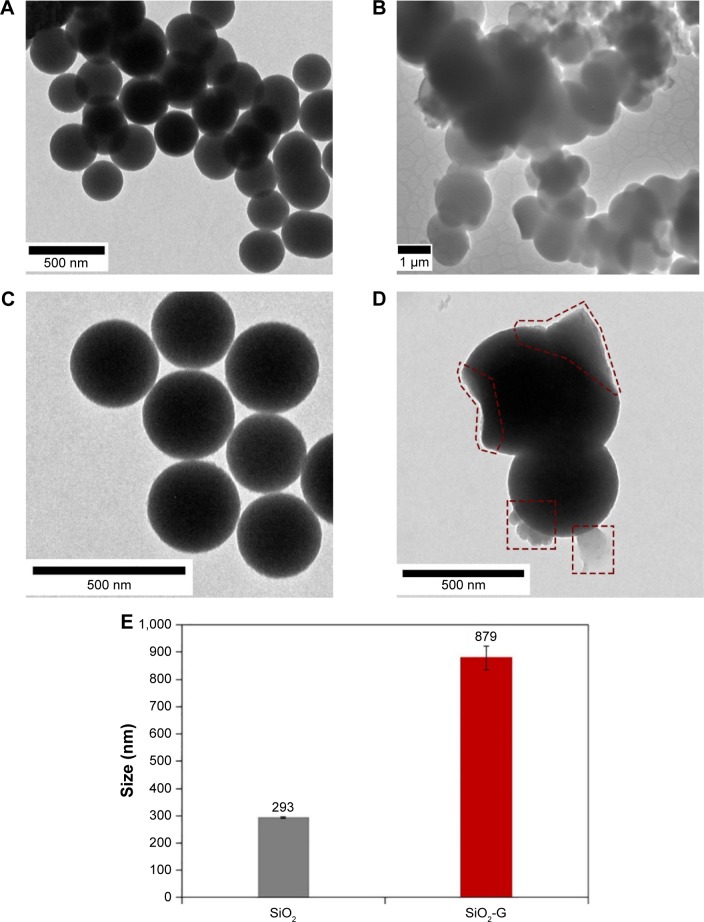

The TEM images (Figure 2) envisage the remarkably different structures and mean diameters of the pristine SiO2 NPs and SiO2-G nanohybrids. It can be seen that the pristine SiO2 NPs (Figure 2A and C) are somewhat monodisperse with a mean diameter (Figure 2E) of 293±21 nm and size distribution of 254–325 nm (Figure S1A). In contrast, the SiO2-G nanohybrids (Figure 2B and D) tend to unite and form aggregated networks with a striking increase in the mean diameter (Figure 2E) to 879±264 nm and a considerable variation in the size distribution of 453–1,248 nm (Figure S1B). The decrease in the zeta potential after the gentamicin loading also contributes to the reduction in the repulsive forces of the nanohybrids, facilitating such network aggregation. This increase in size is consistent with our earlier observations,27,39 suggesting the loading of gentamicin onto the surface and in the SiO2 matrix. To some extent, this outcome supports that of Alvarez et al60 who detected an increase in the size of SiO2 from 441±5 nm to 511±38 nm after gentamicin loading with a slight decrease in the negative surface charge from −47±5 mV to −43±7 mV, respectively. The observed correlation between the present dramatic increase in the size of the nanohybrids after gentamicin loading and the dramatic decrease in their negative charge might be explained in the following way: the more efficient decrease in the negative charge facilitates more efficient uniting of the nanohybrids and a more prominent increase in their size. Interestingly, additional thin layers are also observed on the surface of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (Figure 2D), representing the surface-loaded gentamicin. This loaded gentamicin has also been reported by the appearance of the bands of gentamicin (see Supplementary materials) in the ATR-FTIR spectrum of the nanohybrids (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

TEM images of the materials.

Notes: (A, C) Pristine SiO2 NPs and (B, D) SiO2-G nanohybrids. The surface-loaded gentamicin is marked red with dashed shapes in panel D. Magnifications of 8,000× (A), 60,000× (B), and 10,000× (C, D). (E) The size of the pristine SiO2 and SiO2-G nanohybrids analyzed on the obtained TEM, and SEM and TEM images, respectively. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Abbreviations: SEM, scanning electron microscope; SiO2 NPs, silica nanoparticles; SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin; TEM, transmission electron microscope.

Antibacterial effects of SiO2-Gnanohybrids against planktonic MRSAcells

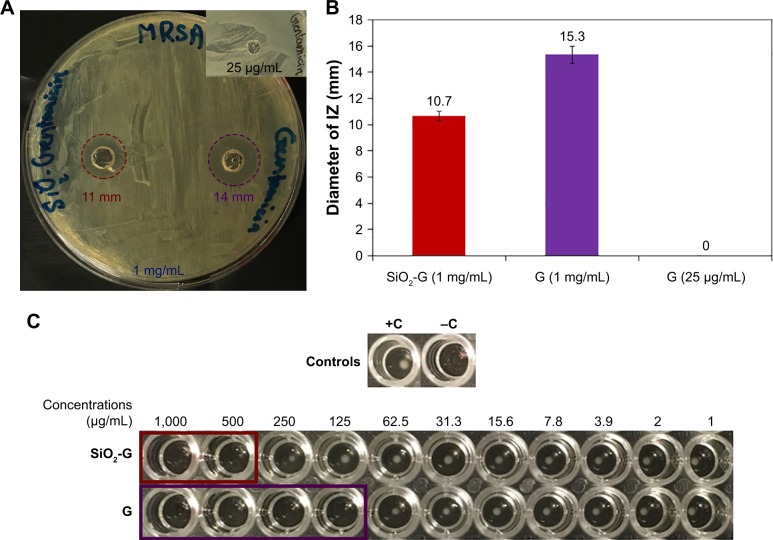

To compare the antibacterial effects of the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin, IZs were first measured in agar diffusion assays after 24 hours. It is somewhat surprising that no IZ was observed by pristine gentamicin (25 µg/mL). On the contrary, the SiO2-G nanohybrids (1 mg/mL), releasing the same concentration of gentamicin (25.05 µg/mL) after 24 hours as determined in our previous study,27 elicited IZs of 10.7±0.6 mm (Figure 3A and B). To find a reasonable inhibitory concentration of the SiO2-G nanohybrids against MRSA, the MIC and MBC were second identified against planktonic MRSA cells. According to the data in Figures 3C and S3, the MICs and MBCs were 500 and 125 µg/mL for the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin, respectively. However, the SiO2-G nanohybrids release only ~12.5 µg gentamicin/mL at their MIC,27 indicating that the SiO2-G nanohybrids are aptly more effective than pristine gentamicin (MIC, 125 µg/mL) to inhibit the tenacious MRSA cells. The most explicit finding to emerge from the present tests is that the SiO2-G nanohybrids can overcome the resistance of MRSA against pristine gentamicin, by even releasing less gentamicin. The present results support a previous study, performed with biofilms,57 which showed that the reduction of S. aureus biofilm growth did not necessarily correlate with the amount of gentamicin released from different bone cement. Some bone cement showed a more significant reduction of S. aureus biofilms, by even releasing less gentamicin compared with other bone cement in the same study.

Figure 3.

Antibacterial effects of the materials tested.

Notes: (A) Agar diffusion assay of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (1 mg/mL) and pristine gentamicin (1 mg/mL) against planktonic MRSA cells, highlighting the IZs with dashed red and violet circles, respectively. The inset shows the lack of IZ by pristine gentamicin (25 µg/mL). (B) The diameters of IZs. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means. (C) MICs of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 µg/mL) and pristine gentamicin (G, 125 µg/mL) against planktonic MRSA cells, highlighting the clear wells in SiO2-G nanohybrids and gentamicin assays with red and violet rectangles, respectively. +C, positive control, an MRSA suspension showing a button of bacterial growth. −C, negative control, uninoculated MHB.

Abbreviations: G, gentamicin; IZs, inhibition zones; MHB, Mueller–Hinton broth; MICs, minimum inhibitory concentrations; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin.

Antibiofilm effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin

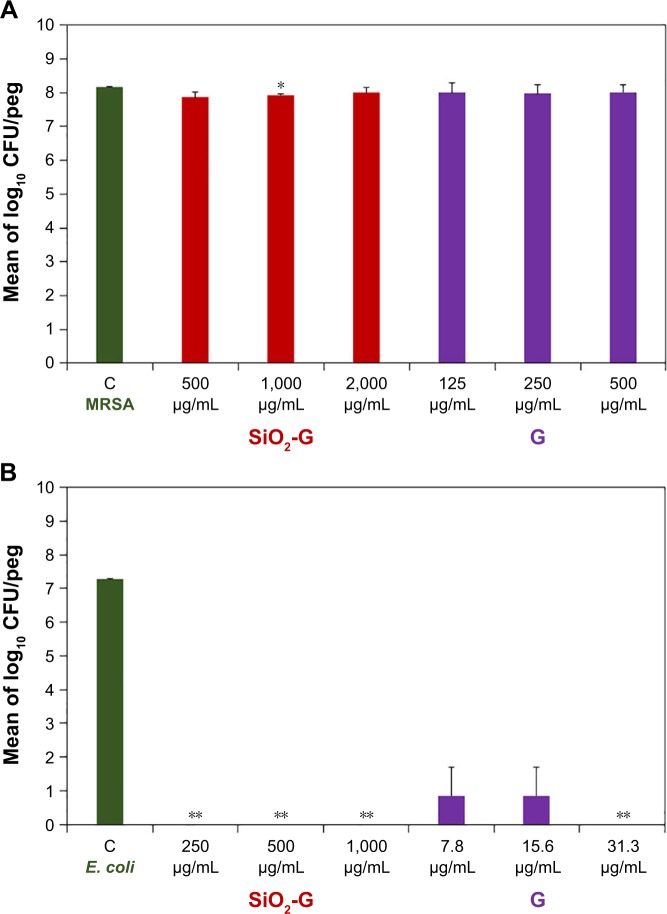

To determine the susceptibilities of the preformed MRSA and E. coli biofilms, under dynamic conditions, on the pegs of the CBD to the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin tested, the viable counts of bacterial cells in biofilms were first compared after neutralization and plating as shown in Figure 4 and Table S1. Log10 numbers of the viable counts of MRSA cells in the positive control biofilms are presented in Figure 4A. The viable counts of MRSA cells in the bio-films were not reduced after treatment with the different concentrations (1×, 2×, and 4× of the MICs recorded for the planktonic MRSA cells) of SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin (Figure 4A). These nonreduced viable counts highlight the problem of the stubborn resistance of MRSA cells in biofilms. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 4B, there were significant differences between log10 numbers of the viable counts of E. coli cells in the positive control bio-films and the biofilms treated with the SiO2-G nanohybrids (P=0.002 for the three concentrations tested) and pristine gentamicin (P=0.002 for the highest concentration tested). SiO2-G nanohybrids had entirely eradicated the E. coli bio-films with an MBEC recorded as 250 µg/mL. The correlation between the presently recorded MBEC of the SiO2-G nanohybrids against E. coli cells in biofilms and the same previously recorded MIC (250 µg/mL) against planktonic E. coli cells27 is of interest. Counting CFUs in the biofilms is one of the principal ways to delineate the efficient diffusion of antibiotics through the biofilms, and an excellent antibiotic diffusion is demonstrated by recording similar MICs for the cells in the biofilms and the planktonic form.9 This similar MBEC and MIC underpin the SiO2-G nanohybrids as a promising delivery system releasing effective gentamicin concentrations that diffuse through and entirely eradicate the E. coli biofilms. Pristine gentamicin also eradicated E. coli biofilms with an MBEC recorded as 7.8 µg/mL (Figure 4B), which places E. coli cells in biofilms within the intermediate range of susceptibility according to the MIC standards of the CLSI for planktonic cells.50

Figure 4.

Antibiofilm effects of the materials tested.

Notes: Mean of log10 numbers of the viable cells (CFU/peg) in MRSA (A) and E. coli (B) biofilms counted by spot plating of the dispersed cells from the pegs after neutralization. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means. The data shown are representative of two separate experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 indicate significant differences compared with the control using Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unequal variance).

Abbreviations: C, control; CFU, colony-forming units; E. coli, Escherichia coli; G, gentamicin; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SiO2-G, Silica–gentamicin.

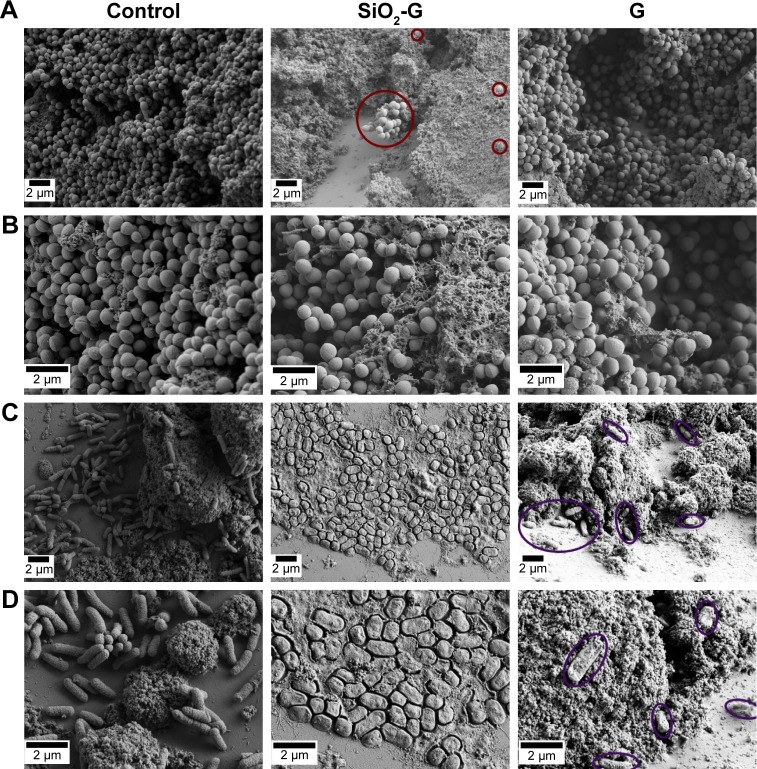

To further investigate the susceptibility of the preformed biofilms to the materials tested, the pegs of the CBD were visualized by SEM (Figures 5, S4 and S5). The architecture of the MRSA biofilms (Figure 5A and B) appeared to be unaffected by the treatment with the SiO2-G nanohybrids and pristine gentamicin. In contrast, there were interesting differences between the architecture of the untreated E. coli biofilms and the biofilms treated with the SiO2-G nanohy-brids and pristine gentamicin (Figure 5C and D). SiO2-G nanohybrids seemed to orchestrate a holistic ultrastructural deformation of the E. coli biofilms in the form of an utter deterioration of cell shapes and apt damage and wrinkling of their cell walls. E. coli biofilms treated with pristine gen-tamicin demonstrated a scattered distribution of few cells with a slightly deformed ultrastructure.

Figure 5.

SEM images of the susceptibility of preformed biofilms to the materials tested.

Notes: (A, B) MRSA and (C, D) E. coli biofilms formed on the pegs of the CBD in the absence (control) or presence of the SiO2-G nanohybrids or G, respectively, taken at the magnifications of 5,000× (A, C) and 10,000× (B, D). Red circles demonstrate the intact ultrastructure of the MRSA biofilms treated with the SiO2-G nanohybrids. Violet ellipses demonstrate scattered E. coli cells with a slightly deformed ultrastructure in biofilms treated with G.

Abbreviations: CBD, Calgary biofilm device; E. coli, Escherichia coli; G, pristine gentamicin; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SEM, scanning electron microscope; SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin.

Due to the tedious techniques needed for cultivating and quantifying biofilm growth and subsequently adopting antimicrobial screening programs, it is of paramount importance to develop rapid screening methods for evaluating the antimicrobial susceptibilities of bacteria following biofilm formation.14 Consequently, we have utilized the CBD as a reliable and rapid method to detect the biofilm susceptibilities to the SiO2-G nanohybrids. The CBD can aptly reproduce biofilm formation and mimic in vivo biofilms, and it facilitates the characterization of the formed biofilms by microscopic techniques.9 A robust relationship between ultrasound waves and the destroyed ultrastructure of biofilms, increasing the bactericidal effect of antibiotics, has been reported in the literature.61 This relationship was exemplified in the work of Rediske et al,62 which illustrated that high-intensity ultrasonic pulses eradicate E. coli biofilms on subcutaneously implanted disks in rabbits receiving systemic gentamicin treatment with no adverse effects on the skin integrity. Furthermore, there is little agreement on the sonication time required to detach the biofilms, ranging from as short as 60 seconds in the modified Robbins device57,63 to 5 minutes in both 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates64 and the CBD,65 or also increasing in the CBD to 10 minutes66 and 30 minutes.17 van de Belt et al63 have also found that the continuous flow of medium in the modified Robbins device facilitates the detachment of fragments of the formed biofilms (24 hours) on the gentamicin-loaded bone cement. Consequently, high rates of shaking (160 rpm) for a long time (30 minutes), instead of sonication, were adopted in the present study to detach the biofilms. This shaking played a crucial role in excluding errors originating from the damage of bacterial cells in biofilms after ultrasonication, thus facilitating a more accurate quantification of viable cells in the biofilms. It also offered a way to exclude the inconsistency reported in the literature for the sonication time required to detach the biofilms.

The combination of the present findings suggests the following: first, the SiO2-G nanohybrids can combat the resistance of planktonic MRSA cells against pristine gentamicin. This combating of resistance facilitates the use of such delivery systems to prevent the formation of biofilms composed of stubborn MRSA strains. Second, SiO2-G nanohybrids can entirely eradicate the preformed E. coli biofilms but not MRSA biofilms. The deterioration of the shape and the reduction of the size of E. coli cells in biofilms treated with the SiO2-G nanohybrids are more pronounced and complete, as observed by SEM than seen with pristine gentamicin. Therefore, the SiO2-G nanohybrids can combat the virulence of E. coli cells in biofilms, which is mainly attributed to their flagella, allowing for surface colonization.8 The SiO2-G nanohybrids thus possess superior antibiofilm effects compared with pristine gentamicin. A recent study67 has reported a change in the surface charge of liposomal gentamicin from −54.5 to 17.5 mV after association with lysozyme and speculated the role of this surface charge in the antibiofilm effects of the lysozyme-associated liposomal gentamicin. The change in surface charge might facilitate an electrostatic attraction of the positively charged lysozyme-associated liposomal gentamicin to the negative charge of alginate in the biofilm matrix. This change in the surface charge resembles, to some extent, our results showing the decrease of the negative charge from −61.6±0.9 mV to −9±1.5 mV for the pristine SiO2 NPs and SiO2-G nanohybrids, respectively. In contrast, prior studies68,69 have noted an intense inhibition of diffusion of the positively charged pristine gentamicin (aminoglyco-side) through biofilm layers after binding to the negatively charged alginate in the biofilm matrix. Consequently, one of the remarkable findings to emerge from the present study is that SiO2-G delivery systems preserve the full utilization of the gentamicin released to combat preformed E. coli cells in biofilms, instead of being entirely sequestered by the negative charge of the biofilm matrix. While seeking a reasonable explanation for the absence of antibiofilm effects of the nanohybrids against MRSA cells in biofilms, it is noteworthy that another study70 has shown enhanced antibiofilm effects of an NP-stabilized capsule with a core of cinnamaldehyde dissolved in peppermint oil. In that study, the enhanced effects against MRSA biofilms were attributed to the cationic nature of the capsule enabling more interactions with the biofilms and the acidic nature of the biofilms breaking the capsule and releasing more cinnamaldehyde. Consequently, the surface charge of the present SiO2-G delivery systems enabled the full utilization of gentamicin against E. coli cells in biofilms but was not cationic enough to allow the interaction of the nanohybrids with MRSA biofilms.

In vivo toxic effects of SiO2-G nanohybrids in zebrafish embryos/larvae

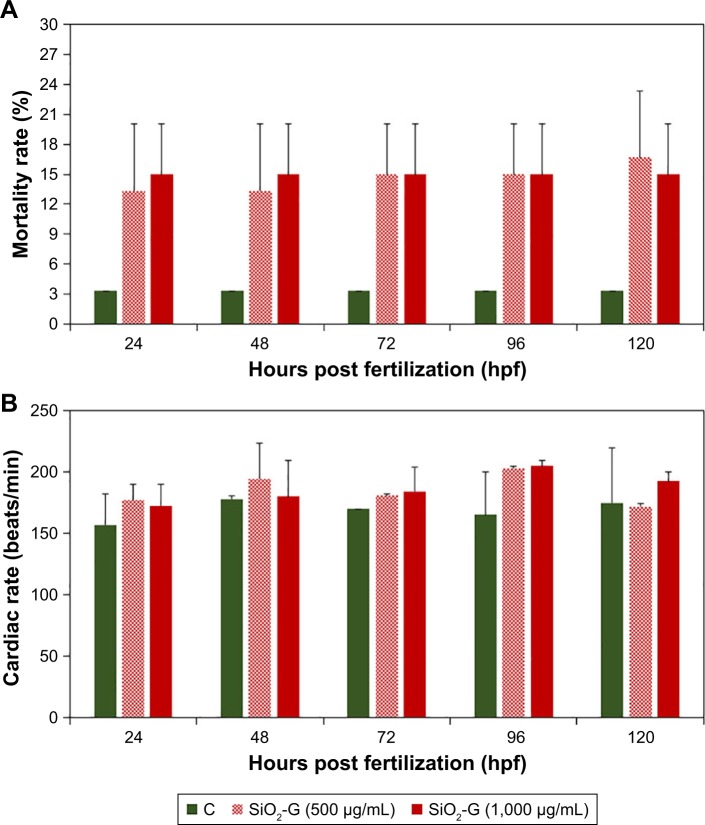

To enable the use of SiO2-G nanohybrids as delivery systems in orthopedic applications, the possible toxicity of SiO2-G nanohybrids was assessed in vivo in the second avenue of the present research through evaluating a series of endpoints in zebrafish embryos/larvae. The exposure concentrations (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) represented multiples of the MIC of the planktonic MRSA cells (1× and 2×) and MBEC of E. coli biofilms (2× and 4×), respectively. The results obtained from the continuous monitoring of the mortality rates are presented in Figure 6A. The embryos exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids demonstrated higher mortality rates than the control group. However, this increase in the mortality rates was not significant (P>0.05) and was mainly detected at the embryonic developmental stage of 24 hpf, as 13.4%±9.4% and 15%±7.1% at the exposure to 500 and 1,000 µg/mL of SiO2-G nanohybrids, respectively, in comparison with the 3.3% mortality in the control group. The mortality rate slightly increased over time (120 hpf) at the exposure to 500 µg/mL of the nanohybrids, reaching 16.7%±9.4%. Despite this, the mortality rates recorded at the exposure to 1,000 µg/mL of the nanohybrids and the control group remained consistent 24 hpf and over the time (120 hpf), underpinning the absence of a time-dependent increase in the mortality rates. Concerning the hatching rates, all the embryos exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) demonstrated normal 100% hatching rates after 72 hours, in the same way as the control group. A comparison of the continuous monitoring of the cardiac rates of the embryos/larvae exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) and the control group are presented in Figure 6B and Table S2. The embryos/larvae revealed a slight nonsignificant increase (P>0.05) in the cardiac rates (tachycardia) at the exposure to the SiO2-G nanohybrids at the two concentrations tested. This tachycardia indicates that the SiO2-G nanohybrids may lead to slight cardiac arrhythmias.

Figure 6.

In vivo toxic effects of the materials tested.

Notes: (A) Mortality and (B) cardiac rates of zebrafish embryos/larvae exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL). The mortality rates demonstrated a nonsignificant increase mainly 24 hpf, after exposure to the nanohybrids at the concentrations of 500 and 1,000 µg/mL. Embryos/larvae exposed to the nanohybrids demonstrated a slight tachycardia at the concentrations of 500 and 1,000 µg/mL. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means of two separate experiments, 30 embryos in each group. All the P-values are >0.05 compared with the control group using Student’s t-tests (two-tailed, unequal variance).

Abbreviations: C, control group; SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin.

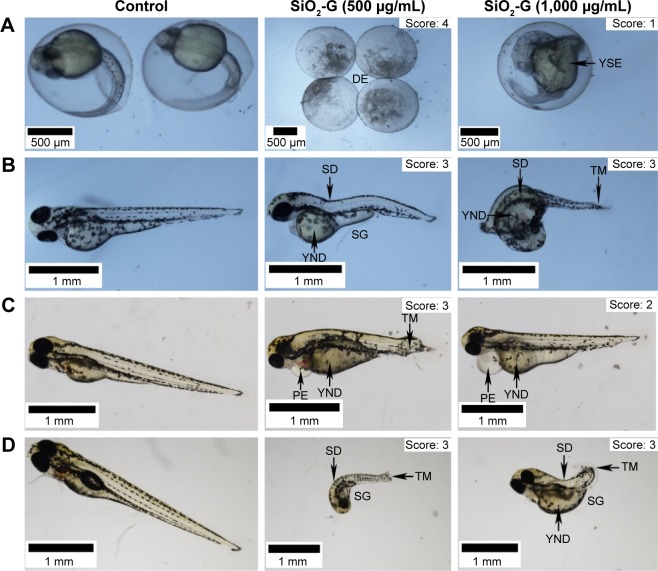

In Figure 7, images of the control group provide an overview of the normal developmental stages of zebrafish embryos/larvae. The exposure of embryos/larvae to the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) ignites the scenery with a throng of sublethal malformations (Figure 7 and Figure S6), including pericardial edema; yolk sac edema (YSE) or yolk not depleted (YND); stunted growth (SG); spinal deformity (SD); and tail malformation (TM) or broken tail (BT). To address a semiquantitative toxicity profile for each exposure group of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL), the scoring spectrum (1, 2, and 3; defining various degrees of malformations) values were determined at each time point and then accumulated. The normally developed embryos/larvae represent score 0. The dead embryos/larvae represent score 4 and were recognized in the mortality recordings. The scoring spectra and cumulative values are shown in Table S3 and Figure S7. A closer inspection of the average cumulative scores and the exposure concentrations demonstrate that the lower exposure concentration (500 µg/mL) showed average cumulative scores of 25, 25.9±14.6, and 30.9±18.1 for scores 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In contrast, the higher exposure concentration (1,000 µg/mL) showed average cumulative scores of 28±9.6, 27.4±15.9, and 12±8.4 for scores 1, 2, and 3, respectively. These data suggest the preeminence of scores 3 and 1 as average cumulative toxicity profiles for the lower (500 µg/mL) and higher (1,000 µg/mL) exposure concentrations, respectively.

Figure 7.

Malformations of zebrafish embryos/larvae.

Notes: Microscopic images (3X objective) of different developmental stages of zebrafish embryos/larvae 24 hpf (A), 48 hpf (B), 72 hpf (C), and 96 hpf (D). The control group presents the normal development of the embryos/larvae with no malformations (score: 0). The embryos treated with the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) show a range of malformations, such as YSE or YND, SD, SG, TM, and PE. The severity of malformations is scored (1–4). The highest score, 4, is marked for the DE.

Abbreviations: DE, degenerated embryos; PE, pericardial edema; SD, spinal deformity; SG, stunted growth; SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin; TM, tail malformation; YND, yolk not depleted; YSE, yolk sac edema.

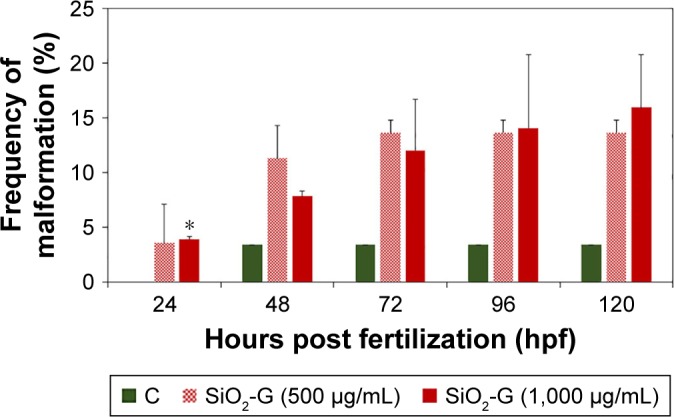

Frequencies of malformations induced by the exposure to both concentrations tested were generally similar (Figure 8). On the contrary, the frequency of malformations induced by the SiO2-G nanohybrids 24 hpf was noticeable when compared with the control group (4%±0.4% at the concentration of 1,000 µg/mL vs 0% for the control group). This difference reached a statistical significance (P=0.04) and reflected, to some extent, the recorded higher mortality rates induced by this concentration at the embryonic developmental stage of 24 hpf. The most common sublethal malformations (Figure S8) developed by zebrafish embryos/larvae exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids were YSE or YND (30.6%±27.5%) followed by TM or BT (29.2%±5.9%) for the lower exposure concentration (500 µg/mL). YSE or YND (34.1%±30.5%) followed by SD (23%±14.7%) were the most common malformations recorded for the higher exposure concentration (1,000 µg/mL) of the SiO2-G nanohybrids. Taken together, the present results suggest that YSE or YND, TM or BT, and SD are the common malformations developed by the embryos/larvae at the exposure to the SiO2-G nanohybrids. However, the overall incidences of these common malformations (Figure S8) were not significantly different from those in the control group for either exposure concentrations.

Figure 8.

Frequencies of malformations of zebrafish embryos/larvae.

Notes: SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) induced frequencies of malformations at different developmental stages. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means of two separate experiments, using 30 embryos in each group. *P<0.05 is significant compared with the control group using Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unequal variance).

Abbreviations: SiO2-G, silica–gentamicin; C, control group.

The present study has, for the first time, addressed the crucial questions of the in vivo toxicity of the SiO2-G nanohybrids using zebrafish embryos, to enable their safe and robust orthopedic applications. Prior studies have noted the importance of the size of NPs in the toxicity elicited in zebrafish embryos; for example, smaller Ag NPs have induced more in vivo toxicity.71–73 When considering the role of the size of NPs in the in vivo toxicity, the chorionic pores of the embryos should also merit attention. Lee et al74 have shown the passive diffusion of Ag NPs (30–72 nm) through the chorionic pore canals (0.5–0.7 µm) of the embryos and the clogging of the pores by the aggregation of Ag NPs. As far as SiO2 toxicity is concerned, Duan et al46 have reported a dose- and time-dependent increase in the mortality and hatching rates of zebrafish embryos treated by SiO2 NPs (62 nm). More specifically, the in vitro toxicity of SiO2-G nanohybrids (719±128 nm) has been identified in our earlier study,39 showing a significant time-dependent decrease in the viability of human osteoblast-like SaOS-2 cells. Only 25%±1% of cells are viable after 5 days at the nanohybrid concentration of 250 µg/mL. This cell viability indicates severe cytotoxicity of the SiO2-G nanohybrids at the concentration of 250 µg/mL. The present results, in contrast, show a nonsignificant increase in the mortality rates (120 hpf) at both exposure concentrations of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) tested and the foremost increase in the mortality rates recorded 24 hpf, with almost no time-dependent increase in the mortalities of the treated embryos/larvae. Furthermore, all the embryos exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids (500 and 1,000 µg/mL) hatched normally (48 hpf) and only showed a slight nonsignificant increase in the cardiac rates. These contradictory findings between our previous in vitro studies39 and the present in vivo investigations obtained even using the same synthesis strategy of the SiO2-G nanohybrids are apparently attributed to the size of the SiO2-G nanohybrids (879±264 nm). The chorionic pore diameter hinders the full diffusion of the large-sized nanohybrids into the embryonic tissues. The higher mortality rates recorded in the time frame around 24 hpf in the present study resemble the findings of Lee et al,75 who defined the embryonic late segmentation stage (21–23 hpf), showing the highest mortalities as the most sensitive stage of zebrafish embryos to the toxicities induced by Ag NPs (13.1±2.5 nm). The embryonic hatching stage (48–50 hpf) was defined as the most resistant stage to the toxicities of Ag NPs in the same study.

Regarding the scoring spectra and the frequencies of malformations, it is somewhat surprising that the average cumulative scoring toxicity profile was higher for the lower exposure concentration, although the frequency of malformations (Figure 8) at different developmental stages was not significantly different from the control group. In contrast, the higher exposure concentration had a lower average cumulative scoring toxicity profile and a significantly different incidence of malformations (Figure 8), from the control group, recorded at 24 hpf. This significant different incidence of malformations can also correlate with the slightly higher mortality rates recorded for the higher exposure concentration only 24 hpf and can specify a possible dose-dependent sublethal toxicity (malformations) for the nanohybrids at the exposure of the embryos to the higher exposure concentration, only 24 hpf. This dose-dependent sublethal toxicity seems to happen only at 24 hpf because of the sensitivity of the embryos at this stage. Furthermore, the small chorionic pore diameter hindered the full diffusion of the large-sized SiO2-G nanohybrids; consequently, only the sublethal toxicity reached a significant level at this stage, while the mortality rates only increased without reaching significant levels even at the higher exposure concentration. Similar to the mortality rates (showing almost no time-dependent increase), there was no increase in the cumulative scoring profile of all the time points at the higher exposure concentration. Thus far, the present results provide further support for the hypothesis that the late segmentation stage is the most sensitive stage to the toxicities elicited by SiO2-G nanohybrids. The crucial role of the size of the SiO2-G nano-hybrids is also emphasized at the embryonic developmental stage of 24 hpf through the nonsignificant increase in the mortality rates recorded in the exposed embryos at this stage and in the significant malformations recorded only at 24 hpf at the higher exposure concentration.

Proceeding now to the common malformations developed by the embryos/larvae at the exposure to the SiO2-G nanohybrids, YSE or YND, TM or BT, and SD were the common malformations recorded. The present results match those observed in an earlier study,46 recording YSE and TMs as common malformations induced by SiO2 NPs. The presently demonstrated deficiency in yolk utilization can explain the SG shown in this study as it infers that the embryos were not using all the yolk nutrients required for growth.42,71 Overall, while the present study shows neither significant mortalities nor significant common malformations induced by the exposure of the embryos to the SiO2-G nanohybrids, it does point towards the pivotal role of the large size of the nanohybrids. This large size possibly causes less diffusion of the nanohybrids into the embryonic tissue, governed by the chorionic pore diameter, and consequently, decreases the elicited in vivo toxicity of the embryos exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids. Relating the mild or nonsignificant effects caused by the SiO2-G nanohybrids in vivo in the present study to our previously recorded significant cytotoxicity of the SiO2-G nanohybrids towards human osteoblast-like SaOS-2 cells39 adds more complexity to the safety issues in using the SiO2-G nanohybrids as an antibiotic delivery system in orthopedic applications. These discrepancies between the in vitro and in vivo levels of toxicity of the same nanomaterials are consistent with data obtained in earlier studies. These earlier data, however, have shown more toxic effects in zebrafish embryos than in mammalian cells using Ag NPs (size of 95.68 nm dispersed in water)76 or metal-organic frameworks (diameter of 170 nm).77

In a nutshell, the present study has identified different approaches to combating the resistance of planktonic MRSA cells to gentamicin as well as for the complete eradication of preformed E. coli biofilms. These results highlight the possibility to use the SiO2-G nanohybrids as an antibiotic delivery system in orthopedic applications, preventing the formation of biofilms and eradicating the preformed biofilms of MRSA and E. coli, respectively. Even though the mortality rates of the zebrafish embryos exposed to the SiO2-G nanohybrids remained statistically nonsignificant, this addresses the two sides of the same coin: 1) the possible biocompatibility of such delivery systems in orthopedic applications, and 2) the complexities and uncertainties associated with the safety issues of such delivery systems. These uncertainties result from the difficulty to interpret the discrepancies between the results of in vivo and in vitro studies in the present and our previous work,39 respectively.

Conclusion

This work is the first empirical investigation on SiO2-G nanohybrids (879±264 nm) using both in vitro assays (antibacterial and antibiofilm effects) and in vivo toxicity assessments in zebrafish embryos. The main in vitro findings of this work are as follows: 1) The SiO2-G nanohybrids are more effective than pristine gentamicin against planktonic MRSA and E. coli biofilms. 2) The SiO2-G nanohybrids can destroy the tenacity of planktonic MRSA cells with a minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentration of 500 µg/mL. 3) The SiO2-G nanohybrids can entirely eradicate E. coli biofilms at a MBEC of 250 µg/mL. 4) The treatment of E. coli bio-films with SiO2-G nanohybrids causes an utter ultrastructural deformation of E. coli cells, showing deformed cell shapes and wrinkled cell walls, as demonstrated by SEM. The main in vivo findings of this work are as follows: 1) 24 hpf is the most sensitive embryonic developmental stage to the toxicity of SiO2-G nanohybrids. 2) Even though only a nonsignificant increase in mortalities is detected in the exposed embryos 24 hpf, malformations with significantly different frequency from the control group are also detected 24 hpf for the higher exposure concentration. 3) The large size of SiO2-G nanohybrids apparently plays a pivotal role in the nonsignificant occurrence of mortalities recorded in zebrafish embryos. 4) Nondepleted yolk and SG types of malformations are the most common ones developed by zebrafish embryos/larvae, indicating the nonusage of the required nutrients in the yolk after exposure to the SiO2-G nanohybrids. Therefore, this work provides robust evidence for the use of the SiO2-G nanohybrids as biocompatible antibiotic delivery systems combating recalcitrant planktonic MRSA cells and preventing and eradicating MRSA and E. coli biofilms. However, more studies are needed to elucidate the in vivo toxic effects of smaller sized SiO2-G nanohybrids to conclusively demonstrate the possibility of safely using such delivery systems. Continued efforts to reveal the underlying mechanisms of action of the SiO2-G nanohybrids are also needed to decipher the basis for the better antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of the nanohybrids than pristine gentamicin.

Acknowledgments

DAM gratefully thanks Alfred Kordelin Foundation for the personal working grant [grant number 170297] for this PhD thesis work and School of Chemical Engineering, Aalto University, for the funding support. The authors kindly thank the Electron Microscopy Unit, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, for further processing the fixed biofilms formed on the pegs of the CBD for SEM analyses. The authors also express their heartfelt gratitude to Prof Anming Meng and Dr Shunji Jia for kindly providing the zebrafish embryos and allowing DAM to use the facilities of the State Key Laboratory of Biomembrane and Membrane Biotechnology, Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Tsinghua University. They acknowledge the provision of facilities and technical support by Aalto University at OtaNano – Nanomicroscopy Center (Aalto-NMC).

Footnotes

Author contributions

DAM defined the research plan under the supervision of S-PH, KN, and QF. DAM prepared the nanomaterials under the supervision of S-PH (in Aalto University) and QF (in Tsinghua University). DAM characterized the nanomaterials by SEM, zeta potential analyses, and TEM under the supervision of MBL (in Aalto University) and QF (in Tsinghua University). DAM and UH designed the antibacterial and antibiofilm tests under the supervision of KN (in Aalto University) and AP (in University of Helsinki). DAM performed all the antibacterial and antibiofilm tests at the University of Helsinki. DAM analyzed the fixed biofilms formed on the pegs of the CBD by SEM under the supervision of MBL at Aalto University. PM took part in the SEM analyses. DAM and WH designed the in vivo toxicity experiments under the supervision of QF. DAM performed all the in vivo toxicity experiments in Tsinghua University. YM took part in the microscopic analyses of the zebrafish embryos. DAM interpreted all the characterization results, antibacterial and antibiofilm results, SEM analyses of biofilms, and the in vivo toxicity results under the supervision of Prof MBL. DAM wrote the manuscript under the supervision of MBL. All the authors revised the manuscript with merited contributions endowed by UH. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Li B, Webster TJ. Bacteria antibiotic resistance: new challenges and opportunities for implant-associated orthopedic infections. J Orthop Res. 2018;36(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/jor.23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy H, Rudkin JK, Black NS, Gallagher L, O’Neill E, O’Gara JP. Methicillin resistance and the biofilm phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simovic S, Ghouchi-Eskandar N, Sinn AM, Losic D, Prestidge CA. Silica materials in drug delivery applications. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2011;8(3):269–276. doi: 10.2174/157016311796799026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG., Jr Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mah TF, O’Toole GA. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01913-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart PS, Costerton JW. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet. 2001;358(9276):135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Houdt R, Michiels CW. Role of bacterial cell surface structures in Escherichia coli biofilm formation. Res Microbiol. 2005;156(5–6):626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4):999–1007. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.999-1007.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown MR, Allison DG, Gilbert P. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics: a growth-rate related effect? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22(6):777–780. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anwar H, Strap JL, Costerton JW. Establishment of aging biofilms: possible mechanism of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36(7):1347–1351. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams I, Venables WA, Lloyd D, Paul F, Critchley I. The effects of adherence to silicone surfaces on antibiotic susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 1997;143(Pt 7):2407–2413. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith AW. Biofilms and antibiotic therapy: is there a role for combating bacterial resistance by the use of novel drug delivery systems? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57(10):1539–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das JR, Bhakoo M, Jones MV, Gilbert P. Changes in the biocide susceptibility of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Escherichia coli cells associated with rapid attachment to plastic surfaces. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84(5):852–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anwar H, van Biesen T, Dasgupta M, Lam K, Costerton JW. Interaction of biofilm bacteria with antibiotics in a novel in vitro chemostat system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(10):1824–1826. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.10.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toté K, Horemans T, Berghe DV, Maes L, Cos P. Inhibitory effect of biocides on the viable masses and matrices of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(10):3135–3142. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02095-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allan ND, Omar A, Harding MW, Olson ME. A rapid, high-throughput method for culturing, characterizing and biocide efficacy testing of both planktonic cells and biofilms. In: Mendez-Vilas A, editor. Science against microbial pathogens: Communicating current research and technological advances. Badajoz, Spain: Formatex Research Center; 2011. pp. 864–871. (Edition: Microbiology Book Series). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi O, Yu CP, Esteban Fernández G, Hu Z, Hu Z, Ferna GE. Interactions of nanosilver with Escherichia coli cells in planktonic and biofilm cultures. Water Res. 2010;44(20):6095–6103. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Belt H, Neut D, van Horn JR, van der Mei HC, Schenk W, Busscher HJ. Antibiotic resistance – to treat or not to treat? Nat Med. 1999;5(4):358–359. doi: 10.1038/7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kankala RK, Liu C-G, Chen A-Z, et al. Overcoming multidrug resistance through the synergistic effects of hierarchical pH-sensitive, ROS-generating nanoreactors. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3(10):2431–2442. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuthati Y, Kankala RK, Busa P, et al. Phototherapeutic spectrum expansion through synergistic effect of mesoporous silica trio-nanohybrids against antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacterium. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2017;169:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Ghannam A, Ahmed K, Omran M. Nanoporous delivery system to treat osteomyelitis and regenerate bone: gentamicin release kinetics and bactericidal effect. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;73(2):277–284. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seleem MN, Munusamy P, Ranjan A, Alqublan H, Pickrell G, Sriranganathan N. Silica-antibiotic hybrid nanoparticles for targeting intracellular pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(10):4270–4274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00815-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi X, Wang Y, Ren L, Zhao N, Gong Y, Wang DA. Novel mesoporous silica-based antibiotic releasing scaffold for bone repair. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(5):1697–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue JM, Shi M. PLGA/mesoporous silica hybrid structure for controlled drug release. J Control Release. 2004;98(2):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue JM, Tan CH, Lukito D. Biodegradable polymer–silica xerogel composite microspheres for controlled release of gentamicin. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;78(2):417–422. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosselhy DA, Ge Y, Gasik M, Nordström K, Natri O, Hannula SP. Silica-gentamicin nanohybrids: synthesis and antimicrobial action. Materials (Basel) 2016;9(3):170. doi: 10.3390/ma9030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aughenbaugh W, Radin S, Ducheyne P. Silica sol-gel for the controlled release of antibiotics. II. The effect of synthesis parameters on the in vitro release kinetics of vanomycin. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57(3):321–326. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20011205)57:3<321::aid-jbm1174>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radin S, Ducheyne P, Kamplain T, Tan BH. Silica sol-gel for the controlled release of antibiotics. I. Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro release. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57(2):313–320. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200111)57:2<313::aid-jbm1173>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agnihotri S, Pathak R, Jha D, et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of aminoglycoside-conjugated silica nanoparticles against clinical and resistant bacteria. New J Chem. 2015;39(9):6746–6755. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovalenko Y, Sotiri I, Timonen JVI, et al. Bacterial interactions with immobilized liquid layers. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(15):1600948. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arciola CR, An YH, Campoccia D, Donati ME, Montanaro L. Etiology of implant orthopedic infections: a survey on 1027 clinical isolates. Int J Artif Organs. 2005;28(11):1091–1100. doi: 10.1177/039139880502801106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng H, Xia T, George S, Nel AE. A predictive toxicological paradigm for the safety assessment of nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2009;3(7):1620–1627. doi: 10.1021/nn9005973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Sui B, Sun J. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction induced by silica NPs in vitro and in vivo: involvement of oxidative stress and Rho-kinase/JNK signaling pathways. Biomaterials. 2017;121:64–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orlando A, Cazzaniga E, Tringali M, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles trigger mitophagy in endothelial cells and perturb neuronal network activity in a size- and time-dependent manner. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:3547–3559. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S127663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou CC, Chen W, Hung Y, Mou CY. Molecular elucidation of biological response to mesoporous silica nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(27):22235–22251. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b05359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, Liu X, Li Y, et al. The negative effect of silica nanoparticles on adipogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;81:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ha SW, Sikorski JA, Weitzmann MN, Beck GR., Jr Bio-active engineered 50 nm silica nanoparticles with bone anabolic activity: therapeutic index, effective concentration, and cytotoxicity profile in vitro. Toxicol In vitro. 2014;28(3):354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He W, Mosselhy DA, Zheng Y, et al. Effects of silica–gentamicin nanohybrids on osteogenic differentiation of human osteoblast-like SaOS-2 cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:877–893. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S147849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas CR, George S, Horst AM, et al. Nanomaterials in the environment: from materials to high-throughput screening to organisms. ACS Nano. 2011;5(1):13–20. doi: 10.1021/nn1034857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bugel SM, Tanguay RL, Planchart A. Zebrafish: a marvel of high-throughput biology for 21st century toxicology. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2014;1(4):341–352. doi: 10.1007/s40572-014-0029-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sant KE, Timme-Laragy AR. Zebrafish as a model for toxicological perturbation of yolk and nutrition in the early embryo. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2018;5(1):125–133. doi: 10.1007/s40572-018-0183-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spoorendonk KM, Hammond CL, Huitema LFA, Vanoevelen J, Schulte-Merker S. Zebrafish as a unique model system in bone research: the power of genetics and in vivo imaging. J Appl Ichthyology. 2010;26(2):219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renn J, Winkler C, Schartl M, Fischer R, Goerlich R. Zebrafish and medaka as models for bone research including implications regarding space-related issues. Protoplasma. 2006;229(2–4):209–214. doi: 10.1007/s00709-006-0215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhenhua L, Deepa A, Inleng C, Mingyuen LS. The zebrafish: a novel model organism for bone research. Pharmacol Clin Chinese Mater Medica. 2010;3:029. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duan J, Yu Y, Shi H, et al. Toxic effects of silica nanoparticles on zebrafish embryos and larvae. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharif F, Porta F, Meijer AH, Kros A, Richardson MK. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a compound delivery system in zebrafish embryos. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1875–1890. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corrêa GG, Morais EC, Brambilla R, et al. Effects of the sol-gel route on the structural characteristics and antibacterial activity of silica-encapsulated gentamicin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014;116:510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CLSI . M02-A12 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard. 12th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.CLSI . M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 27th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.CLSI . M07-A10: Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard. 10th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52.CLSI . M26-A: Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents; Approved Guideline. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harrison JJ, Ceri H, Yerly J, et al. The use of microscopy and three-dimensional visualization to evaluate the structure of microbial biofilms cultivated in the Calgary Biofilm Device. Biol Proced Online. 2006;8(1):194–215. doi: 10.1251/bpo127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203(3):253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heiden TC, Dengler E, Kao WJ, Heideman W, Peterson RE. Developmental toxicity of low generation PAMAM dendrimers in zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;225(1):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van de Belt H, Neut D, Uges DR, et al. Surface roughness, porosity and wettability of gentamicin-loaded bone cements and their antibiotic release. Biomaterials. 2000;21(19):1981–1987. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van de Belt H, Neut D, Schenk W, van Horn JR, van Der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation on different gentamicin-loaded polymethylmethacrylate bone cements. Biomaterials. 2001;22(12):1607–1611. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stallmann HP, Faber C, Bronckers AL, Nieuw Amerongen AV, Wuisman PI. In vitro gentamicin release from commercially available calcium-phosphate bone substitutes influence of carrier type on duration of the release profile. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mebert AM, Aimé C, Alvarez GS, et al. Silica core–shell particles for the dual delivery of gentamicin and rifamycin antibiotics. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4:3135–3144. doi: 10.1039/c6tb00281a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alvarez GS, Hélary C, Mebert AM, Wang X, Coradin T, Desimone MF. Antibiotic-loaded silica nanoparticle–collagen composite hydrogels with prolonged antimicrobial activity for wound infection prevention. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:4660–4670. doi: 10.1039/c4tb00327f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu J, Zhang N, Jr, Li L, et al. The synergistic bactericidal effect of vancomycin on UTMD treated biofilm involves damage to bacterial cells and enhancement of metabolic activities. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):192. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rediske AM, Roeder BL, Nelson JL, et al. Pulsed ultrasound enhances the killing of Escherichia coli biofilms by aminoglycoside antibiotics in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(3):771–772. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.771-772.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van de Belt H, Neut D, Schenk W, van Horn JR, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Gentamicin release from polymethylmethacrylate bone cements and Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(6):625–629. doi: 10.1080/000164700317362280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang A, Mu H, Zhang W, Cui G, Zhu J, Duan J. Chitosan coupling makes microbial biofilms susceptible to antibiotics. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):3364. doi: 10.1038/srep03364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. The Calgary Biofilm Device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(6):1771–1776. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1771-1776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abdelghany SM, Quinn DJ, Ingram RJ, et al. Gentamicin-loaded nanoparticles show improved antimicrobial effects towards Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:4053–4063. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hou Y, Wang Z, Zhang P, et al. Lysozyme associated liposomal gentamicin inhibits bacterial biofilm. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(4):784. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shigeta M, Tanaka G, Komatsuzawa H, Sugai M, Suginaka H, Usui T. Permeation of antimicrobial agents through Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: a simple method. Chemotherapy. 1997;43(5):340–345. doi: 10.1159/000239587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ishida H, Ishida Y, Kurosaka Y, Otani T, Sato K, Kobayashi H. In vitro and in vivo activities of levofloxacin against biofilm-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42(7):1641–1645. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duncan B, Li X, Landis RF, et al. Nanoparticle-stabilized capsules for the treatment of bacterial biofilms. ACS Nano. 2015;9(8):7775–7782. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]